Abstract

Background

Severe bleeding and coagulopathy are serious clinical conditions that are associated with high mortality. Thromboelastography (TEG) and thromboelastometry (ROTEM) are increasingly used to guide transfusion strategy but their roles remain disputed. This review was first published in 2011 and updated in January 2016.

Objectives

We assessed the benefits and harms of thromboelastography (TEG)‐guided or thromboelastometry (ROTEM)‐guided transfusion in adults and children with bleeding. We looked at various outcomes, such as overall mortality and bleeding events, conducted subgroup and sensitivity analyses, examined the role of bias, and applied trial sequential analyses (TSAs) to examine the amount of evidence gathered so far.

Search methods

In this updated review we identified randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from the following electronic databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 1); MEDLINE; Embase; Science Citation Index Expanded; International Web of Science; CINAHL; LILACS; and the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (up to 5 January 2016). We contacted trial authors, authors of previous reviews, and manufacturers in the field. The original search was run in October 2010.

Selection criteria

We included all RCTs, irrespective of blinding or language, that compared transfusion guided by TEG or ROTEM to transfusion guided by clinical judgement, guided by standard laboratory tests, or a combination. We also included interventional algorithms including both TEG or ROTEM in combination with standard laboratory tests or other devices. The primary analysis included trials on TEG or ROTEM versus any comparator.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently abstracted data; we resolved any disagreements by discussion. We presented pooled estimates of the intervention effects on dichotomous outcomes as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Due to skewed data, meta‐analysis was not provided for continuous outcome data. Our primary outcome measure was all‐cause mortality. We performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses to assess the effect based on the presence of coagulopathy of a TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided algorithm, and in adults and children on various clinical and physiological outcomes. We assessed the risk of bias through assessment of trial methodological components and the risk of random error through TSA.

Main results

We included eight new studies (617 participants) in this updated review. In total we included 17 studies (1493 participants). A total of 15 trials provided data for the meta‐analyses. We judged only two trials as low risk of bias. The majority of studies included participants undergoing cardiac surgery.

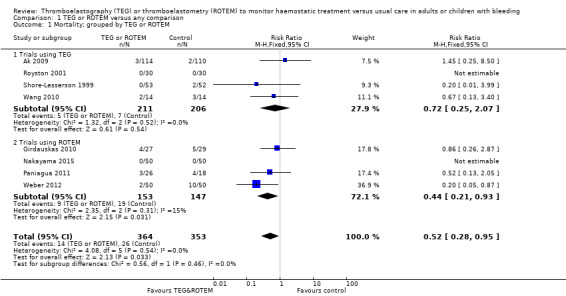

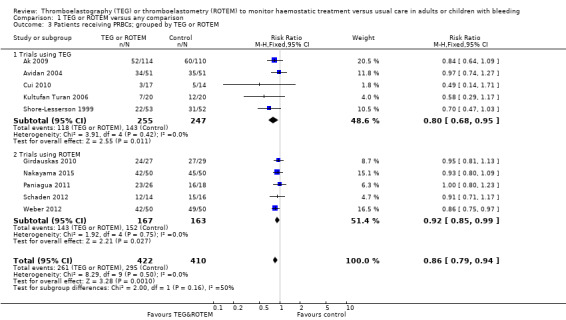

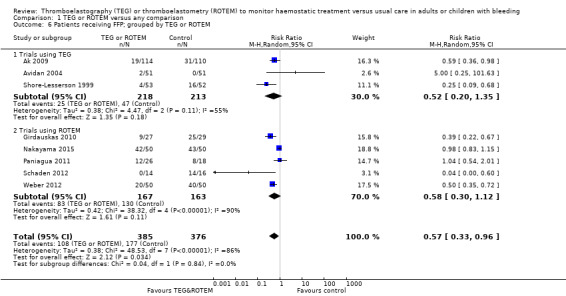

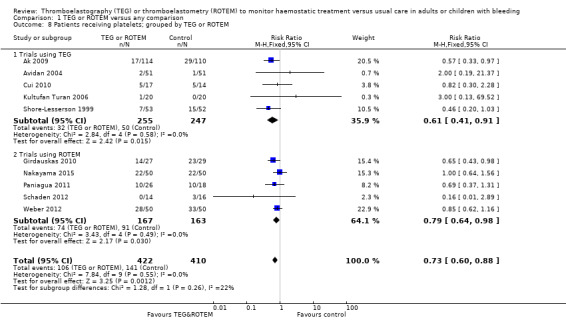

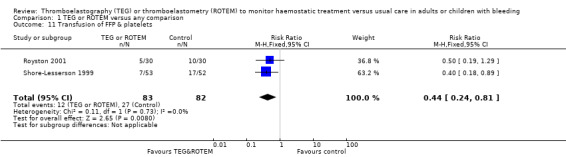

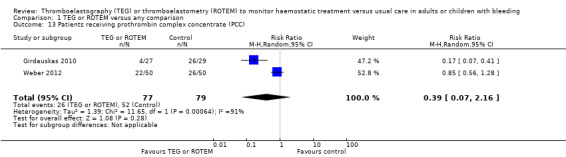

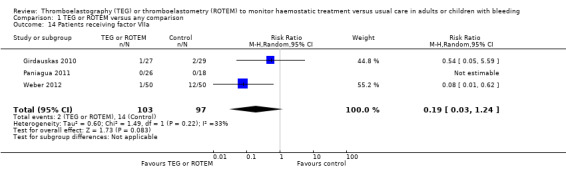

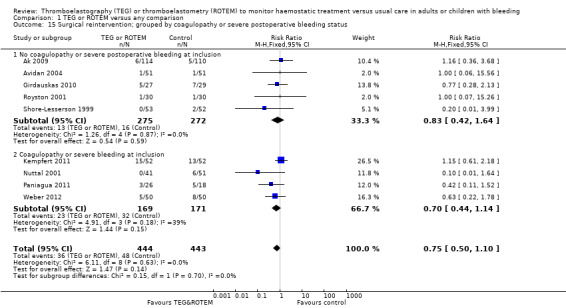

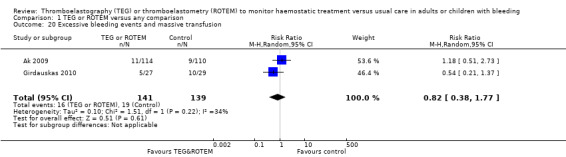

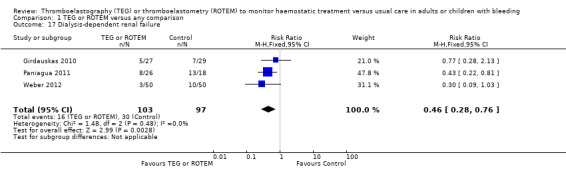

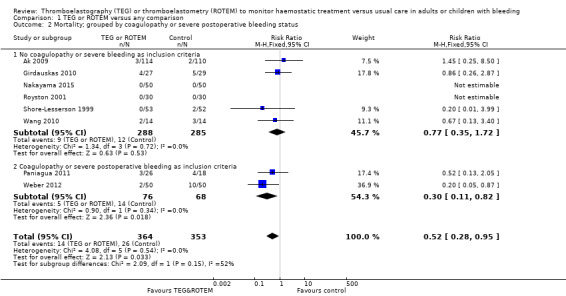

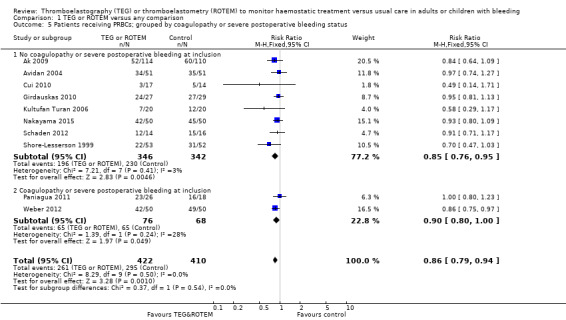

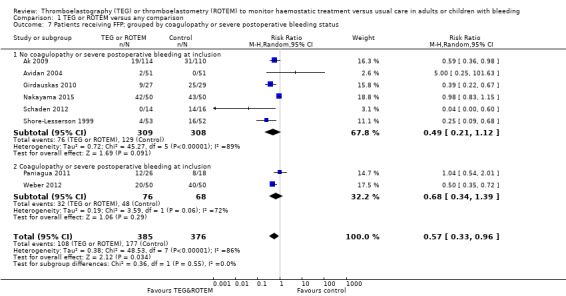

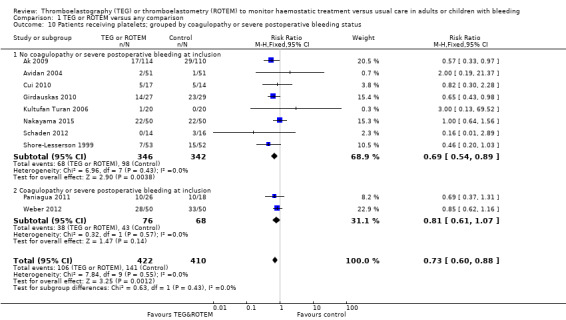

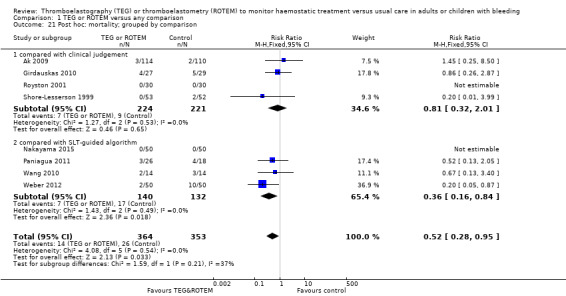

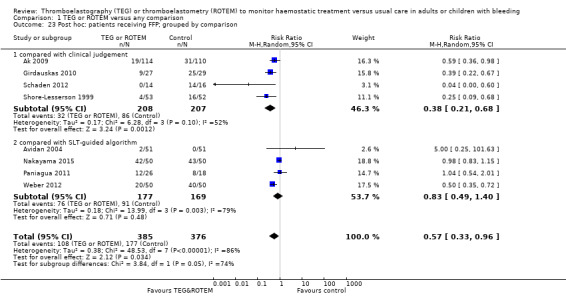

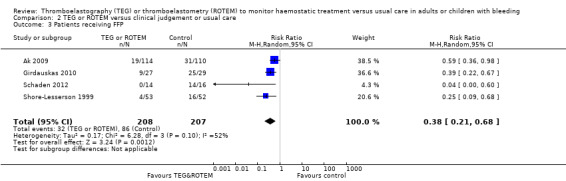

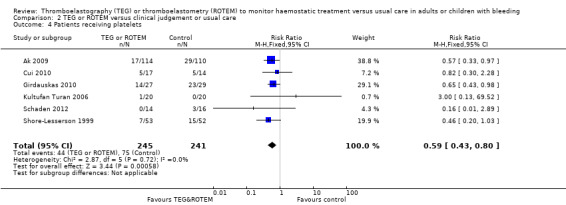

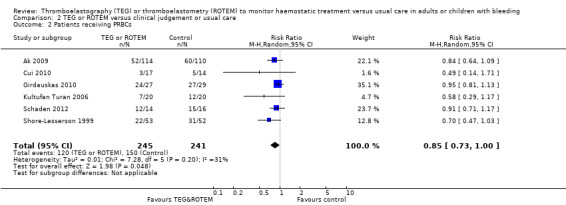

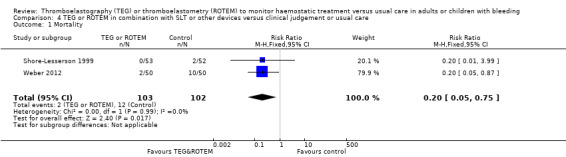

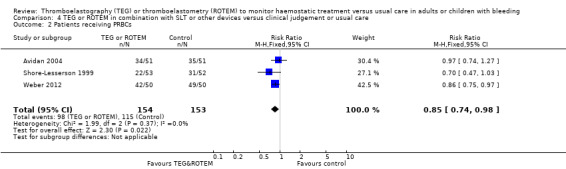

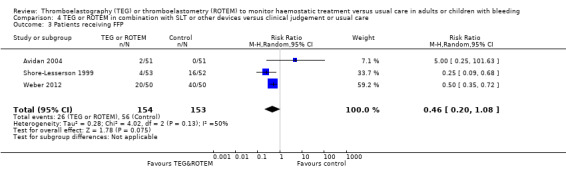

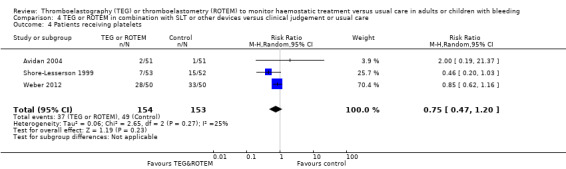

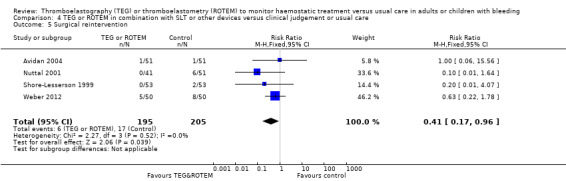

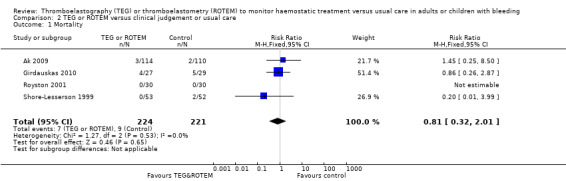

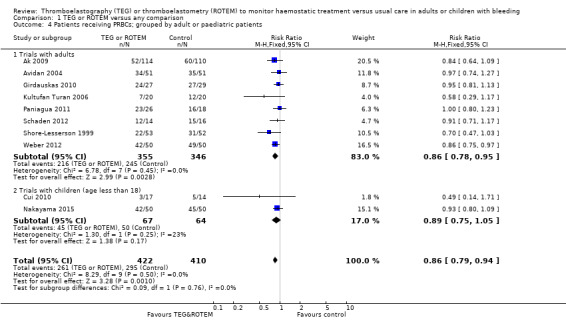

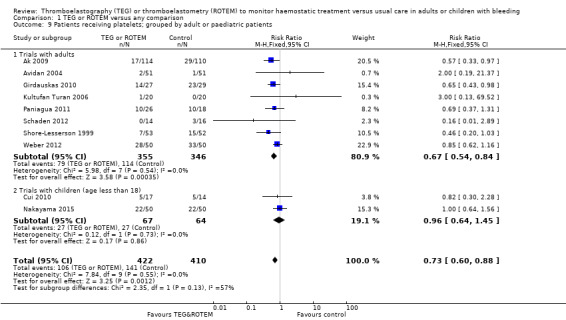

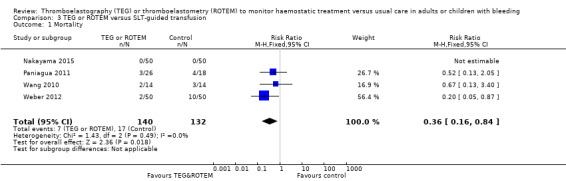

We found six ongoing trials but were unable to retrieve any data from them. Compared with transfusion guided by any method, TEG or ROTEM seemed to reduce overall mortality (7.4% versus 3.9%; risk ratio (RR) 0.52, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.95; I2 = 0%, 8 studies, 717 participants, low quality of evidence) but only eight trials provided data on mortality, and two were zero event trials. Our analyses demonstrated a statistically significant effect of TEG or ROTEM compared to any comparison on the proportion of participants transfused with pooled red blood cells (PRBCs) (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.94; I2 = 0%, 10 studies, 832 participants, low quality of evidence), fresh frozen plasma (FFP) (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.96; I2 = 86%, 8 studies, 761 participants, low quality of evidence), platelets (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.88; I2 = 0%, 10 studies, 832 participants, low quality of evidence), and overall haemostatic transfusion with FFP or platelets (low quality of evidence). Meta‐analyses also showed fewer participants with dialysis‐dependent renal failure.

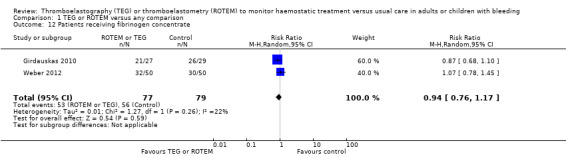

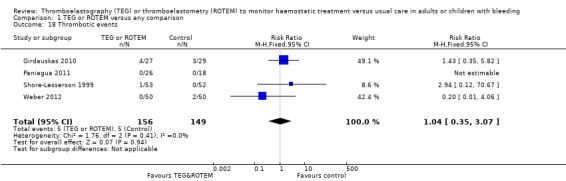

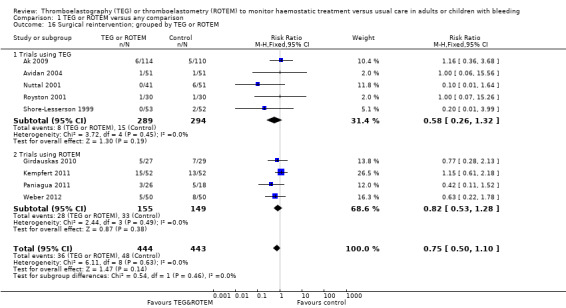

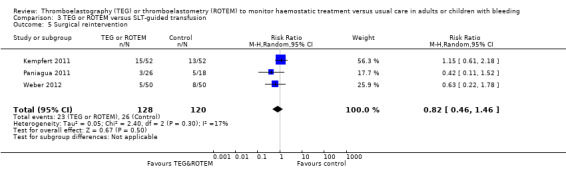

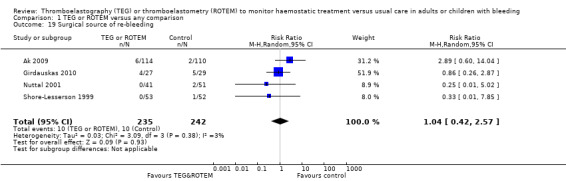

We found no difference in the proportion needing surgical reinterventions (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.10; I2 = 0%, 9 studies, 887 participants, low quality of evidence) and excessive bleeding events or massive transfusion (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.77; I2 = 34%, 2 studies, 280 participants, low quality of evidence). The planned subgroup analyses failed to show any significant differences.

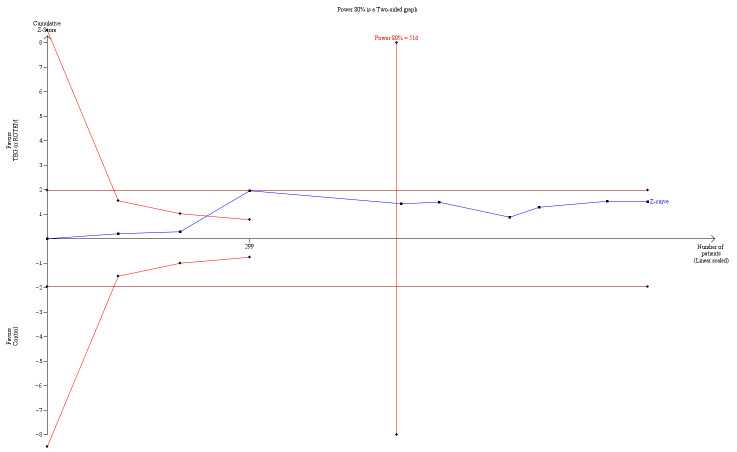

We graded the quality of evidence as low based on the high risk of bias in the studies, large heterogeneity, low number of events, imprecision, and indirectness. TSA indicates that only 54% of required information size has been reached so far in regards to mortality, while there may be evidence of benefit for transfusion outcomes. Overall, evaluated outcomes were consistent with a benefit in favour of a TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided transfusion in bleeding patients.

Authors' conclusions

There is growing evidence that application of TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided transfusion strategies may reduce the need for blood products, and improve morbidity in patients with bleeding. However, these results are primarily based on trials of elective cardiac surgery involving cardiopulmonary bypass, and the level of evidence remains low. Further evaluation of TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided transfusion in acute settings and other patient categories in low risk of bias studies is needed.

Plain language summary

Blood clotting analysers (TEG or ROTEM) versus any comparison to guide the use of blood products in adults or children with bleeding

Background

The ability to make a sufficient blood clot is crucial in participants with bleeding. Clotting can be measured by various tests. TEG and ROTEM tests have the advantage of showing the total clotting capacity. These tests are performed at the bedside, and generally provide a rapid and useful result, guiding clinicians towards a more goal‐directed transfusion management.

Objective

In the present systematic review we set out to assess the benefits and harms of a TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided use of blood products in comparison with standard tests, or doctors clinical judgement, in the treatment of bleeding patients. Evidence is current to January 2016.

Study characteristics

We identified 17 randomized controlled trials comparing TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided use of blood transfusion to guidance from the clinical judgement of doctors or standard laboratory tests, or both. The included trials were conducted mainly in adults in need of cardiac surgery, and involved 1493 participants.

Key results

In terms of efficacy, the use of TEG or ROTEM tests seem to reduce the need for all types of blood transfusions. However, we could not find fewer participants in need of further operations due to continuous bleeding, or at risk of massive bleeding with transfusion. Despite signs of benefit in regards to survival, our findings are hampered by the overall low quality of included studies. Assessment of harms indicated a reduced risk of kidney failure, while no other significant adverse ‐events were found. However, the reported adverse event rates were very low. All included trials except two were marred by high risk of bias.

Quality of evidence

Due to few events and many poorly designed trials, we consider our overall findings to be of low quality evidence in favour of TEG and ROTEM use in the management of bleeding patients.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Bleeding remains a serious condition related to surgery, invasive procedures, child birth, as well as trauma. Ongoing severe bleeding is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, and may prompt the need for additional surgery. Impaired haemostasis can be a contributing factor to postoperative bleeding (Hardy 2005), and may be caused by factors present preoperatively, such as, antithrombotic treatment or inherited deficiencies (Hartmann 2006). Antithrombotic treatment during surgery such as heparinization during cardiopulmonary bypass (Besser 2010; Paparella 2004), or challenges of liver surgery especially with the anhepatic phase may also cause impaired haemostasis in the postoperative period (Sabate 2012).

Dilutional coagulopathy from treatment with intravenous fluids and pooled red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions is frequent in cases of unbalanced multi‐transfusion, together with physiological consumption of haemostatic factors due to the ongoing bleeding (Johansson 2012). If bleeding becomes life‐threatening with development of hypovolaemic shock with acidosis, and if factors such as hypothermia and hypocalcaemia are not controlled (De Robertis 2015), the risk increases for developing severe consumptious coagulopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and hyperfibrinolysis. This may complicate the situation even further, ultimately leading to increased mortality (Hardy 2005).

Coagulopathy, as a result of a massive transfusion and uncontrolled bleeding leads to defects in clot firmness due to fibrinogen, coagulation factor, and platelet deficiency; decreased clot stability due to hyperfibrinolysis and factor XIII deficiency (Brohi 2008; Levrat 2008; Rugeri 2007); and prolonged clot generation due to various coagulation factor deficiencies (Kozek‐Langenecker 2007). Coagulopathy as an isolated entity is just one cause of bleeding. However, despite the ability of various test systems to identify coagulopathy, the tests are unable to predict bleeding in a reliable fashion (Chee 2003; Segal 2005). Surgical bleeding or arterial injury is often the dominant reason for blood loss, resulting in a high transfusion requirement. Thus, identifying the cause of bleeding does not automatically resolve the problem.

Description of the intervention

The decision to transfuse PRBCs is usually guided by measures such as haemoglobin or haematocrit, or in severe cases, clinical signs of circulative instability. Transfusion of haemostatic blood products such as fresh frozen plasma (FFP), cryoprecipitate, platelet units, and various factor concentrates can be guided by clinical judgement, standard laboratory tests, thromboelastography (TEG) or thromboelastometry (ROTEM), or a combination of these, in a more or less fixed transfusion algorithm. Generally, standard laboratory tests include activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, platelet count, and plasma fibrinogen. However, none of these tests were developed to predict bleeding or to guide coagulation management in the surgical setting. They are of limited use in diagnosis and assessment of bleeding risk and in relation to algorithms used to guide the administration of blood products for surgical or critically ill patients (Benes 2015).

The limitations of these tests include a lack of real‐time monitoring; inability to identify singular or multiple coagulation factor deficiencies; no measurement of the effects of hypothermia on haemostasis; and no rapid assessment of fibrinolysis, platelet dysfunction, or haemostatic response to injury or surgery (Benes 2015; Hardy 2004). Additionally, all these tests are performed in plasma at 37 °C without the presence of platelets or other blood cells, and they seem unable to predict the role of the measured components in the context of haemostasis as a whole. Thus, none of these tests can estimate the risk of bleeding (Chee 2003), but they are being used to guide therapy in the presence of clinical bleeding.

TEG is a viscoelastic, haemostatic assay analyser invented by Hartert that imitates sluggish venous flow (Hartert 1948). It provides an evaluation of the kinetics of all stages of clot initiation, formation, stability, strength, and dissolution in whole blood (Benes 2015; Luddington 2005). In conventional TEG, a 0.36 mL blood sample is placed into a cup which is then rotated gently. When a sensor shaft is inserted into the sample a clot forms between the cup and the sensor. The speed and patterns of changes in strength and elasticity in the clot are measured in various ways by a computer and are depicted as a graph. In the reagent‐modified rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) analyser the sensor shaft rotates, rather than the cup rotating (Benes 2015; Lang 2005 ).

TEG and ROTEM have several advantages compared to routine coagulation tests. They are easy to use by non‐laboratory personnel as a point‐of‐care assay in the perioperative and emergency setting; produce rapid graphical and numerical results of the haemostatic status; are able to detect the anticoagulant effect of acidosis, hypo‐ or hyperthermia as they can be performed at between 22 °C and 42 °C; and are able to detect and quantify the underlying cause of coagulopathy, such as thrombocytopenia, factor deficiency, heparin effect, hypofibrinogenaemia, and hyperfibrinolysis (Luddington 2005). Treatment for such disorders may involve the transfusion of blood products (FFP, cryoprecipitate, and platelets) or specific drugs, and the effect can be evaluated in vitro (Benes 2015).

How the intervention might work

Clinical signs of coagulopathy, such as oozing, is a late sign, and therefore accurate management of massive transfusion is often challenged, since there is no simple, reliable, and rapid routine diagnostic coagulation test available (Chee 2003; Hardy 2004). Monitoring dynamic changes of haemostasis by repeatedly performing TEG or ROTEM is thought to enable clinicians to distinguish between a surgical cause of bleeding or coagulopathy, to diagnose the specific type of coagulopathic impairment, and to guide and evaluate the choice of haemostatic treatment. This may enable optimized and reduced use of blood products, while reducing bleeding, the need to reoperate, complications associated with hypovolaemic shock, and ultimately influence mortality positively.

Why it is important to do this review

A clinical method enabling a distinction between surgical bleeding and bleeding caused by coagulopathy, and at the same time providing guidance to drug administration, minimizing usage of blood products, and enabling real‐time monitoring of the patient's coagulation may be of great benefit. TEG or ROTEM may provide more complete diagnostic information more rapidly and perhaps at similar cost to the standard laboratory tests. A change in the clinical management of severe bleeding, as a consequence of this technology, might subsequently reduce transfusion‐related risks, and provide improved patient health outcomes, as well as optimizing the use of healthcare resources.

Randomized trials are needed to evaluate the potential effects of introducing a diagnostic test (Gluud 2005). The benefit and efficacy of TEG or ROTEM in patients with severe bleeding and coagulopathy is still debated. The test accuracy of TEG and ROTEM and the degree of their correlation to standard laboratory tests needs further evaluation, since introduction of yet another diagnostic test in the clinical evaluation of coagulation at the point‐of‐care may only add to the complexity of the problem, as well as lead to an increase in costs. The aim of this review was to assess the evidence as to whether TEG or ROTEM are beneficial or harmful for patients with bleeding.

Objectives

We assessed the benefits and harms of thromboelastography (TEG)‐guided or thromboelastometry (ROTEM)‐guided transfusion in adults and children with bleeding. We looked at various outcomes, such as overall mortality and bleeding events, conducted subgroup and sensitivity analyses, examined the role of bias, and applied trial sequential analyses (TSAs) to examine the amount of evidence gathered so far.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included parallel group randomized controlled trials (RCTs) irrespective of quasi‐randomizations, publication status, blinding status, or language of the report. We contacted the investigators and the authors in order to retrieve the relevant data. We only included unpublished trials if trial data and methodological descriptions were either provided in written form or could be retrieved from the authors. We excluded observational studies. We did not include any studies with non‐standard designs, such as cross‐over trials or cluster‐randomized trials.

Types of participants

We included trials with adults and children who were bleeding. We did not exclude any subgroup of the patient population.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing a TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided transfusion algorithm. We also included interventional algorithms including both TEG or ROTEM in combination with standard laboratory tests or other devices.

The primary analysis included trials on thromboelastography (TEG) or thromboelastometry (ROTEM) versus any comparator.

We undertook separate subgroup analyses of trials in which a TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided transfusion algorithm were compared with clinical judgement, usual treatment, or an algorithm based on standard laboratory tests.

Comparison 1: TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided algorithm versus any comparison.

Comparison 2: TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided algorithm versus clinical judgement or usual treatment.

Comparison 3: TEG‐ or ROTEM‐guided algorithm versus a predefined algorithm based on standard laboratory test‐guided transfusion.

Comparison 4: TEG or ROTEM in combination with standard laboratory tests or other devices in a guided algorithm versus clinical judgement or usual care.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall mortality. We used the longest follow‐up data from each trial, regardless of the period of follow‐up.

Secondary outcomes

Bleeding events, blood loss, proportion of participants in need of transfusion, and amount of blood products transfused.

Complications probably related to the underlying condition, e.g. infections, thrombosis, allergic reactions, congestive cardiac failure, myocardial infarction, renal failure, and cerebrovascular accident.

Incidence of surgical interventions and reoperation due to bleeding.

Complications probably related to transfusion, e.g. infections and sepsis, haemolytic reactions, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and major immunological and allergic reactions.

Quality of life assessment, as defined by authors in included studies.

Duration of mechanical ventilation or improvement of respiratory failure (ventilator‐free days), or both.

Length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Number of days in hospital.

Cost‐benefit analyses.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In this updated review we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 1); Ovid MEDLINE (WebSPIRS) (1950 to 5 January 2016); Ovid Embase (WebSPIRS) (1980 to January 2016); Ovid BIOSIS (WebSPIRS) (1993 to 5 January 2016); International Web of Science (1964 to 5 January 2016); Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) (via BIREME) (1982 to 5 January 2016); the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database; advanced Google; and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCO host) (1980 to 5 January 2016).

In the original review we searched until October 2010 (Afshari 2011).

We performed a systematic and sensitive search strategy to identify relevant RCTs with no language or date restrictions. For specific information regarding our search strategies please see Appendix 1. We reran the search on 5 January 2016.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference list of reviews, randomized and non‐randomized studies, and editorials for additional studies. We contacted the main authors of studies and experts in this field to ask for any missed, unreported, or ongoing studies. We contacted the manufacturers of TEG and ROTEM tests and pharmaceutical companies for any unpublished trials (5 January 2016).

We searched for ongoing clinical trials and unpublished studies on the following Internet sites (search date 6 January 2016).

ISRCTN registry.

Clinical trials registry.

Center Watch.

UMIN clinical trials registry.

Data collection and analysis

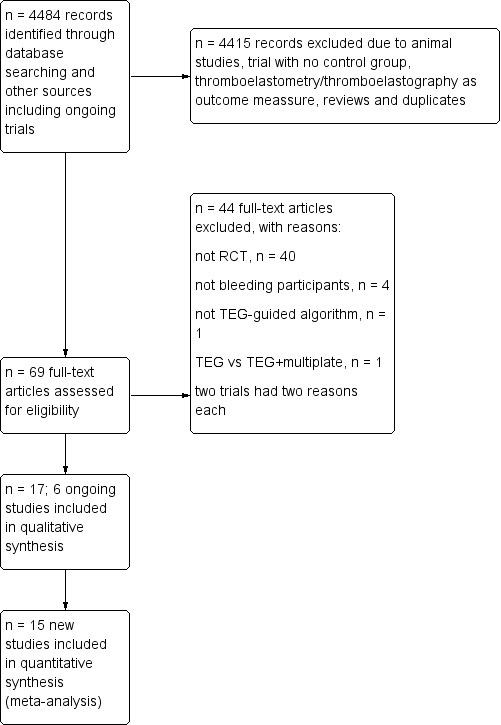

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AW and AA) independently evaluated all relevant trials and provided a detailed description of the included and excluded studies under the sections Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies. We also provided detailed descriptions of our search results (Figure 6), and resolved disagreements by discussion. We screened the titles and abstracts in order to identify eligible studies.

6.

Updated flow diagram for selection of randomized controlled trials up to 5 January 2016.

Data extraction and management

AW and AA independently extracted and collected the data on a standardized paper form. We were not blinded to the author, source institution, or the publication source of trials. We resolved disagreements by discussion and approached all corresponding authors of the included trials for additional information on the review's outcome measures and risk of bias components. For more specific information, please see the section Contributions of authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We addressed each question of validity systematically, as described by the following in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

1) Random sequence generation

Assessment of randomizations: the sufficiency of the method in producing two comparable groups prior to the intervention.

Grading: 'low risk' ‐ a truly random process, e.g. random computer number generator, coin tossing, or throwing dice; 'high risk' ‐ any non‐random process, e.g. date of birth, date of admission by hospital or clinic record number, or by availability of the intervention; or 'unclear risk' ‐ insufficient information.

2) Allocation concealment

Allocation method prevented the investigators or participants from foreseeing the assignment.

Grading: 'low risk' ‐ central allocation or sealed opaque envelopes; 'high risk' ‐ using open allocation schedule or other unconcealed procedure; or 'unclear risk' ‐ insufficient information.

3) Blinding

Assessment of appropriate blinding of the investigation team and participants: person responsible for participants' care, participants, and outcome assessor.

Grading: 'low risk' ‐ we consider blinding as adequate if participants and personnel were kept unaware of intervention allocations after inclusion of participants into the study, and the method of blinding involved a placebo indistinguishable from the intervention, since mortality is a robust outcome; 'high risk' not double‐blinded, categorized as an open‐label study, or without use of a placebo indistinguishable from the intervention; 'unclear risk' ‐ blinding not described.

4) Incomplete outcome data

Completeness of the outcome data including attritions and exclusions.

Grading: 'low risk' ‐ if the numbers and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals in the intervention groups were described or if it was specified that there were no dropouts or withdrawals; 'high risk' ‐ if no description of dropouts and withdrawals was provided; 'unclear risk' ‐ if the report gave the impression that there were no dropouts or withdrawals, but this was not specifically stated.

5) Selective reporting

The possibility of selective outcome reporting.

Grading: 'low risk' ‐ if the reported outcomes are those prespecified in an available study protocol or, if this is not available, the published report includes all expected outcomes; 'high risk' ‐ if not all prespecified outcomes have been reported, have been reported using non‐prespecified subscales, reported incompletely, or the report fails to include a key outcome that would have been expected for such a study); 'unclear risk' ‐ insufficient information.

6) Other bias

The assessment of any possible sources of bias not addressed in domains 1 to 5.

Grading: 'low risk' ‐ if the report appears to be free of such biases; 'high risk' ‐ if at least one important bias is present related to study design, early stopping due to some data‐dependent process, extreme baseline imbalance, academic bias, claimed fraudulence or other problems; or 'unclear risk' ‐ insufficient information, or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data (binary outcomes).

These included: overall mortality; bleeding events; proportion of participants in need of transfusion; complications probably related to the underlying condition, e.g. infections, thrombosis, allergic reactions, congestive cardiac failure, myocardial infarction, renal failure, cerebrovascular accident; incidence of surgical interventions and reoperation due to bleeding; complications probably related to transfusion, e.g. infections and sepsis, haemolytic reactions and disseminated intravascular coagulation, and major immunological and allergic reactions.

Continuous data

We planned to use the mean difference (MD) if data were continuous and measured in a similar way between trials. We used the standardized mean difference (SMD) to combine trials measuring the same outcome with different scales. Some of the trials provided their data as median values. The median value is very similar to the mean when the distribution of the data is symmetrical and so occasionally can be used directly in meta‐analyses (Higgins 2011). However, means and medians can be very different from each other if the data are skewed, and medians are often reported because the data are skewed.

Some of the included trials in this paper provided interquartile ranges, which describe where the central 50% of participants' outcomes lie. When sample sizes are large and the distribution of the outcome is similar to the normal distribution, the width of the interquartile range will be approximately 1.35 standard deviations (SDs) (Higgins 2011). When the distribution of outcomes is skewed, it is not possible to estimate a SD from an interquartile range. Application of interquartile ranges may thus be an indicator that the outcome distribution is skewed. When assessment of data from continuous outcomes showed an overall skewed tendency, we abstained from pooling data and performing meta‐analysis, and instead present the results as tables.

The continuous data included: blood loss; amount of blood transfused; quality of life assessment, as defined by authors in included studies; duration of mechanical ventilation or improvement of respiratory failure (ventilator‐free days), or both; mean length of stay in the ICU; number of days in hospital; and cost‐benefit analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

We excluded cross‐over trials from our meta‐analyses because of the potential risk of carry‐over of treatment effect in the context of bleeding.

Studies with multiple intervention groups

In studies designed with multiple intervention groups, we combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison (Higgins 2011). In trials with two or more TEG or ROTEM groups, we combined data where possible, for the primary and secondary outcomes.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted all the first authors and contact persons of the trials with missing data in order to retrieve the relevant data.

For all included studies we noted levels of attrition and any exclusions. In case of missing data, we chose 'complete‐case analysis' for our primary outcomes, which excludes from the analysis all participants with the outcome missing. Selective outcome reporting occurs when non‐significant results are selectively withheld from publication (Chan 2004), and is defined as the selection, on the basis of the results, of a subset of the original variables recorded for inclusion in publication of trials (Hutton 2000). The most important types of selective outcome reporting are: selective omission of outcomes from reports; selective choice of data for an outcome; selective reporting of different analyses using the same data; selective reporting of subsets of the data; and selective under‐reporting of data (Higgins 2011). Statistical methods to detect within‐study selective reporting are still in their infancy. We tried to explore for selective outcome reporting by comparing publications with their protocols if the latter were available.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored heterogeneity using the I² statistic and Chi² test. An I² statistic above 50% represents substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). In case of I² statistic > 0 (mortality outcome), we tried to determine the cause of heterogeneity by performing relevant subgroup analyses. We used the Chi² test to provide an indication of heterogeneity between studies, with P ≤ 0.1 considered significant.

Assessment of reporting biases

Publication bias occurs when the publication of research results depends on their nature and direction (Dickersin 1990). We examined this by providing a funnel plot in order to detect either publication bias or a difference between smaller and larger studies (small study effect), which is expressed by asymmetry (Higgins 2011).

Funding bias is related to the possible publication delay or discouragement of undesired results in trials sponsored by the industry (Higgins 2011). To explore the role of funding, we provide information on which studies were sponsored by industry.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014) in order to perform meta‐analyses on pre‐stated outcomes from the included trials. If we performed the meta‐analyses and I² statistic = 0, we only reported the results from the fixed‐effect model; in the case of I² statistic > 0 we reported only the results from the random‐effects model, unless one or two trials contributed more than 60% of the total evidence provided, in which case the random‐effects model may be biased.

We believed there was little value in using a fixed‐effect model in cases of substantial heterogeneity, which we expected would be due to the various factors leading to massive bleeding. We pooled studies only in case of low clinical heterogeneity. When using meta‐analysis for combining results from several studies with binary outcomes (i.e. event or no event), adverse side effects may be rare but serious, and hence important (Sutton 2002). Most meta‐analytic software does not include trials with 'zero events' in both arms (intervention versus control) when calculating a RR. Exempting these trials from the calculation of a RR and 95% CI may lead to overestimation of a treatment effect. Cochrane recommends application of the Peto odds ratio (OR), which is the best method of estimating odds ratios when there are many trials with no events in one or both arms (Higgins 2011). However, the Peto method is generally less useful when the trials are small or when treatment effects are large. We planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis by applying the Peto OR if this appeared to be a valid option. However, the trials included did not fulfil criteria for Peto OR (Effects of interventions).

Trial sequential analysis (TSA)

TSA is a methodology that combines an information size calculation for meta‐analysis with a threshold of statistical significance. It is a tool for quantifying the statistical reliability of data in a cumulative meta‐analysis, adjusting significance levels for sparse data and repetitive testing on accumulating data. We conducted TSA at least on the primary outcomes (Brok 2009; Pogue 1997; Pogue 1998; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008), and on the secondary outcomes if the accrued information size was an acceptable fraction of the estimated required information size to allow meaningful analyses (greater than 20%). If the actual accrued information size was too low, we provided the required information size given the actual diversity (Wetterslev 2009), and a possible diversity of 25%.

Meta‐analysis may result in type I errors due to random errors arising from sparse data or repeated significance testing when updating the meta‐analysis with new trials (Brok 2009; Wetterslev 2008). Bias (systematic error) from trials with low methodological quality, outcome measure bias, publication bias, early stopping for benefit and small trial bias may also result in spurious P values (Brok 2009; Higgins 2011; Wetterslev 2008).

In a single trial, interim analysis increases the risk of type I errors. To avoid these, group sequential monitoring boundaries are applied to decide whether a trial could be terminated early because of a sufficiently small P value, i.e. the cumulative Z‐curve crosses the monitoring boundaries (Lan 1983). Sequential monitoring boundaries can also be applied to meta‐analysis, and are called trial sequential monitoring boundaries. In TSA, the addition of each trial in a cumulative meta‐analysis is regarded as an interim meta‐analysis and helps to clarify whether additional trials are needed.

The idea in TSA is that if the cumulative Z‐curve crosses the boundary, a sufficient level of evidence is reached and no further trials may be needed (firm evidence). If the Z‐curve does not cross the boundary, then there is insufficient evidence to reach a conclusion. To construct the trial sequential monitoring boundaries, the required information size is needed and is calculated as the least number of participants needed in a well‐powered single trial (Brok 2009; Pogue 1997; Pogue 1998; TSA 2010; Wetterslev 2008). We aimed to apply TSA as it prevents an increase in the risk of type I error with sparse data or multiple updating in a cumulative meta‐analysis. Hence, TSA provides us with important information in order to estimate the level of evidence of the experimental intervention. Additionally, TSA provides us with important information regarding the need for additional trials and their sample size. We used Trial Sequential Analysis software, version 0.8 (TSA 2010).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned the following subgroup analyses to assess the benefits and harms of TEG and ROTEM based on:

the cause of the underlying condition (e.g. trauma, critically ill patients, surgery);

age group of children (aged less than 18 years) or adults;

the enrolment of the participants to TEG or ROTEM;

coagulopathy or severe postoperative bleeding as inclusion criteria.

If analyses of various subgroups were significant, we planned to perform a test of interaction by applying meta‐regression (Altman 2003; Higgins 2011 ‐ chapters 9.6.3.1 and 9.6.4). We considered P < 0.05 as indicating significant interaction between the TEG or ROTEM effect on mortality and the subgroup category (Higgins 2011 ‐ chapters 9.6.1 and 9.7).

Sensitivity analysis

We compared estimates of the pooled intervention effect in trials with low risk of bias to estimates from trials with high risk of bias (i.e. trials having at least one inadequate risk of bias component).

We calculated the RR with 95% CI and decided to apply complete case analysis, if possible, for our sensitivity and subgroup analyses based on our primary outcome measure (mortality).

Summary of findings

We used the principles of the GRADE system to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with specific outcomes (Guyatt 2008). We constructed 'Summary of findings' tables for each comparison using the GRADE software (add ref). The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The assessment of the quality of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of the effect estimates, and risk of publication bias. We included the following outcomes in 'Summary of findings' tables: overall mortality ‐ longest follow‐up (primary outcome); proportion of participants in need of transfusion; (need of PRBCs, FFP, and platelets); excessive bleeding events and massive transfusion; and incidence of reoperation due to bleeding.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

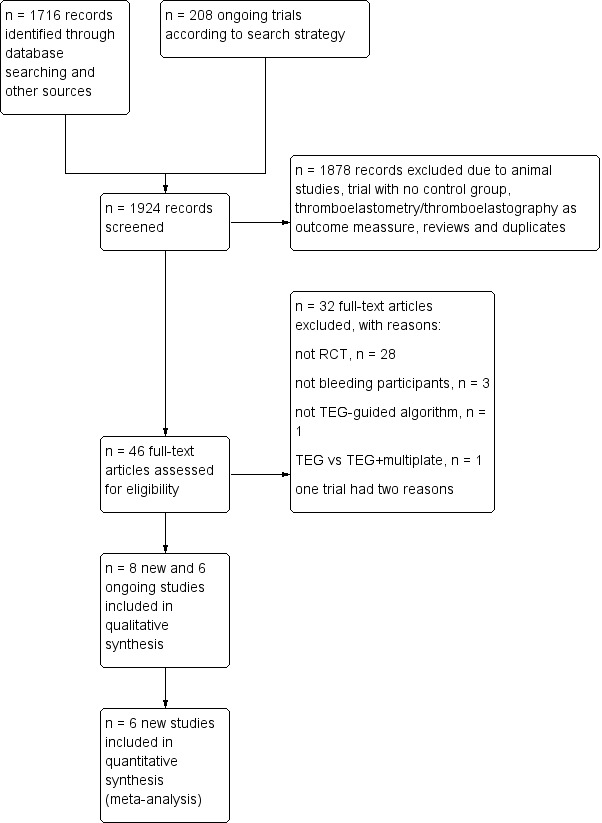

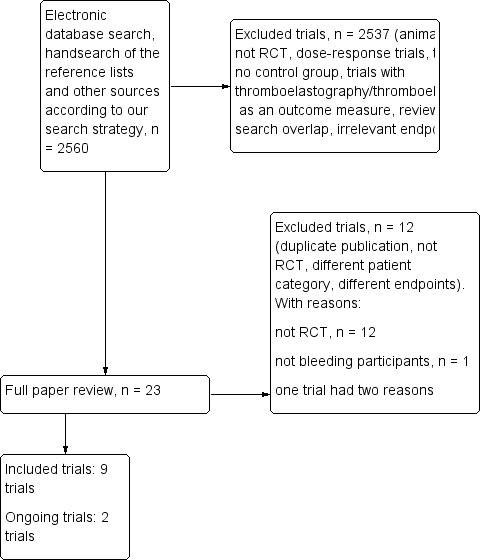

Through electronic searches and from the references of potentially relevant articles, we identified 4484 (1878 in update) publications. We excluded 4415 publications as they were either duplicates or were clearly irrelevant. We retrieved a total of 69 (46 in update) relevant publications for further assessment (Figure 6; Figure 7; Figure 8). From these, we included eight new trials to a total of 17 trials that randomized all together 1493 participants (Cui 2010; Kempfert 2011; Nakayama 2015; NCT00772239; Paniagua 2011; Schaden 2012; Rauter 2007; Weber 2012; see Included studies and Figure 6). Two trials provided no data in the meta‐analyses (NCT00772239; Rauter 2007). All together, we statistically evaluated the results of 15 trials and 1185 participants in the present systematic review. We found six ongoing trials but were unable to retrieve any data from the investigators at their current stage (NCT02352181; NCT02593877; NCT02461251; NCT01536496; NCT02416817; NCT01402739; see Characteristics of ongoing studies). The two review authors (AW, AFSH) completely agreed on the selection of included studies. We obtained additional information from six study authors as listed in the table Characteristics of included studies.

7.

Updated flow diagram for selection of randomized controlled trials from 31 October 2010 to 5 January 5 2016.

8.

Flow diagram for selection of randomized controlled trials up to 31 October 31 according to last published version of this review (Afshari 2011).

Three of the included studies were published only as abstracts (Kempfert 2011; Paniagua 2011; Rauter 2007); and one study was terminated due to futile inclusion (NCT00772239), but with no published results. There were no duplicate reports. Mortality was reported in eight studies (Ak 2009; Girdauskas 2010; Nakayama 2015; Paniagua 2011; Royston 2001; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Wang 2010; Weber 2012). For a more detailed description of the studies, see the table Characteristics of included studies, Table 10, and Table 11.

1. Details of included studies.

| Study | Year of publication | n | Population | Inclusion criteria |

Intervention algorithm (details in Table 11) |

Duration of intervention | Control group transfusion management | Follow‐up | Adequate blinding* |

| Ak 2009 | 2009 | 224 | Cardiac surgery | Elective first‐time CABG, with cardiopulmonary bypass | Fully TEG‐based transfusion algorithm | Intraoperative and until 24 hours post‐CPB | Clinical judgement and SLTs | Unclear; transfusion requirements recorded until discharge from hospital; mortality until 30 days | Yes |

| Avidan 2004 | 2004 | 102 | Cardiac surgery | Elective first‐time CABG, with cardiopulmonary bypass | Partly TEG‐based algorithm, included also the Hepcon and PFA‐100 platelet function analyser | Intraoperative and until 2 hours postsurgery | SLT‐guided transfusion management | 24 hours | No |

| Cui 2010 | 2010 | 31 | Cardiac surgery | Cyanotic paediatric patients undergoing arterial switch operation or double roots transplantation | Fully TEG‐based and fibrinogen concentrate part of algorithm | Unclear | Clinical judgement | Unclear, but at least until ICU discharge | Unclear |

| Girdauskas 2010 | 2010 | 56 | Cardiac surgery | High risk aortic surgery including urgent and emergency surgery (25 with acute type A dissection) with hypothermic circulatory arrest | Fully ROTEM‐based transfusion algorithm | Intra‐ and postoperative algorithm | Clinical judgement and SLTs | Hospital discharge | No |

| Kempfert 2011 | 2011 | 104 | Cardiac surgery | Adult patients with significant postoperative bleeding (> 200 mL/hour) following standard elective isolated or combined cardiac surgical procedures | Fully ROTEM‐based | Unclear | SLT‐guided transfusion management | Unclear | Unclear |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | 2006 | 40 | Cardiac surgery | Either CABG or valve surgery | Fully ROTEG‐based transfusion algorithm | Intra‐ and postoperative algorithm | Clinical judgement and SLTs | 24 hours | Unclear |

| Nakayama 2015 | 2015 | 100 | Cardiac surgery | Elective cardiac surgery with CBP in children weighing less than 20 kg | Fully ROTEM‐based | Intraoperative algorithm | SLT‐guided transfusion management | Until discharge from PICU | Partly ‐ not blinded to staff attending the patient intraoperatively |

| NCT00772239 | 2010 | 100 | Cardiac Surgery | Cardiac surgery or heart transplantation with bleeding regardless of aetiology | ROTEM‐based | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Nuttal 2001 | 2001 | 92 | Cardiac surgery | Abnormal microvascular bleeding after CPB, all types of elective open cardiac surgery requiring CPB | Partly TEG‐based algorithm included also point‐of‐care SLTs | Intraoperative algorithm | Clinical judgement and SLTs | Unclear; transfusion requirements recorded until discharge from hospital | No |

| Paniagua 2011 | 2011 | 44 | Cardiac surgery | Cardiac surgery with extracorporeal circulation and major postoperative bleeding (≥ 300 mL in the first postoperative hour) | Fully ROTEM‐based | Intraoperative and postoperative | SLT‐guided transfusion management | Until stopped bleeding or discharge from hospital | No |

| Rauter 2007 | 2007 | 208 | Cardiac Surgery | Elective on‐pump cardiac surgery | ROTEM‐based | Unclear | Clinical judgement and SLTs | The patients were observed intraoperatively and up to 48 hours postoperatively during their stay in the ICU | No |

| Royston 2001 | 2001 | 60 | Cardiac surgery | High risk of requiring haemostatic products (heart transplantation, revascularization bypass, Ross procedure, multiple valve and revascularization surgery) | Fully TEG‐based transfusion algorithm | Intraoperative algorithm | Clinical judgement and SLTs | Unclear; transfusion requirements and mortality were reported for 2 days postoperatively | Unclear |

| Schaden 2012 | 2012 | 30 | Excision of burn wounds | Surgical excision of burn wounds performed on the third day after burn trauma | Fully ROTEM‐based | Intraoperative and 24 hours postoperatively | Clinical judgement | Until discharge from ICU | No |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | 1999 | 105 | Cardiac surgery | High risk cardiac procedures (single or multiple valve replacement, combined artery bypass plus valvular procedure, cardiac reoperations, thoracic aortic replacement) |

Fully TEG‐based transfusion algorithm instituted when microvascular bleeding occurred | Intraoperative algorithm | Clinical judgement and SLTs | Until hospital discharge, but transfusion requirements reported for 2 days | Yes |

| Wang 2010 | 2010 | 28 | Liver transplantation | Patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation | Fully TEG‐based transfusion algorithm | Intraoperative algorithm | SLT‐guided transfusion management | 3 years | No |

| Weber 2012 | 2012 | 100 | Cardiac surgery | Adult patients with significant postoperative bleeding (250 mL/hour or 50 mL/10 min) or diffuse coagulopathic bleeding following standard elective cardiac surgical procedures | Partly ROTEM‐based transfusion algorithm included also Platelet Mapping | Intraoperative and postoperative algorithm | SLT‐guided transfusion management | Until discharge from PICU | No |

| Westbrook 2009 | 2009 | 69 | Cardiac surgery | All types of procedures except lung transplantations | Partly TEG‐based transfusion algorithm included also Platelet Mapping | Intra‐ and postoperative algorithm | Clinical judgement and SLTs | Until hospital discharge, but transfusion requirements reported for 2 days | Unclear |

*Assessed as blinding to group allocation of physician in charge of the blood transfusion management. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; ICU: intensive care unit; PICU: paediatric intensive care unit; ROTEG: rotational thromboelastography; ROTEM: rotational thromboelastometry; SLT: standard laboratory test; TEG: thromboelastography

2. Details of interventional algorithms.

| Author/year | Duration of intervention | Devices used | RBC trigger | FFP trigger | PLT trigger | Protamine trigger |

Cryo or fib.conc. trigger |

Antifibrinolytics trigger |

| Ak 2009 | Intraoperative and until 24 hours post‐CPB | TEG | Hct < 25% (18% accepted during CPB) |

TEG‐R > 14 min | TEG‐MA < 48 mm | h‐TEG‐R < 0.5 x TEG‐R | ‐ | LY30 > 7.5% |

| Avidan 2004* | Intraoperative and until 2 hours post‐CPB | TEG and PFA‐100 and Hepcon device | hb < 8g/dL | TEG‐R > 10 min (no heparin effect) and bleeding | Prolonged PFA‐100 channel closure time and persisting bleeding | Hepcon measurement | ‐ | LY30 > 7.5% and bleeding > 100 mL/hour |

| Cui 2010 | Unclear | TEG, kaolin activated and functional fibrinogen | No trigger stated, the Hct was higher than 54% before operation | Not described | Not described | Protamine at standard dose (4 mg/kg) | Fibrinogen concentrate to all in TEG group 500 mg to 1000 mg | Not described |

| Girdauskas 2010** | Intra‐ and postoperative | ROTEM (HEPTEM, APTEM, FIBTEM, INTEM) | Hct < 25% (hb < 8.5 g/dL) (20% (hb 6.8 g/dL) accepted during CPB) or severe haemodynamic instability |

HEPTEM‐CT > 260 sec | HEPTEM‐MCF = 35‐45 mm and FIBTEM‐MCF > 8 mm or HEPTEM‐MCF < 35 mm |

INTEM‐CT/HEPTEM‐CT > 1.5 | FIBTEM‐MCF < 8 mm | APTEM‐MCF /HEPTEM‐MCF > 1.5 (if needed beyond standard protocol) |

| Kempfert 2011 | Unclear | ROTEM (4 chamber) | Not stated | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | Intra‐ and postoperative | ROTEG | Details not available | Details not available | Details not available | Details not available | ‐ | Details not available |

| Nakayama 2015 | Intraoperative | ROTEM (HEPTEM, APTEM, FIBTEM, INTEM, EXTEM) | Maintain the haematocrit at 25% to 30% during CPB | EXTEM‐A10 < 30 mm and FIBTEM‐A10 ≤ 5mm | EXTEM‐A10 ≤ 30 mm and FIBTEM‐A10 > 5mm | HEPTEM‐CT/INTEM‐CT < 0.8 | Not available | Not described |

| NCT00772239 | Unclear | ROTEM | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Nuttal 2001 | Intraoperative | TEG, Coaguchek Plus and Coulter‐MDII | Details not available | PT > 16.6 sec or aPTT > 57 sec | TEG‐MA < 48 mm or platelet count < 102,000/µL | ACT‐guided | p‐fibrinogen < 144 mg/dL | At the discretion of the anaesthesiologist |

| Paniagua 2011 | Intra‐ and postoperative | ROTEM (HEPTEM, FIBTEM, INTEM, EXTEM, APTEM) | Hb < 8 g/dL | First line: EXTEM‐CT > 80 S or HEPTEM‐CT > 280 S and INTEM‐CT > 240 S Second line: EXTEM‐MCF < 50 mm and FIBTEM‐MCF < 12 mm | EXTEM‐MCF < 50 mm and FIBTEM‐MCF > 12 mm* | INTEM‐CT > 240 sec and HEPTEM‐CT normal | One patient in the ROTEM group received fibrinogen concentrate. The drug was only available during the last three months of inclusions | EXTEM‐CT >80 S, CFT > 159, EXTEM‐MCF < 50 mm and/or Lysis at 1 hour > 15% |

| Rauter 2007 | Unclear | ROTEM | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Royston 2001 | Intraoperative | TEG and h‐TEG |

Details not available | h‐TEG‐R > 14 min | h‐TEG‐MA < 48 mm | Details not available | ‐ | LY30 > 7.5% |

| Schaden 2012 | Intra‐ and postoperative | ROTEM (APTEM, FIBTEM, EXTEM) | Hb < 8 g/dL | EXTEM‐CT > 100 S | EXTEM‐A10 < 45 mm and FIBTEM‐A10 > 12 mm |

Not relevant | EXTEM‐A10 < 45 mm and FIBTEM‐A10 < 12 mm | Spindle‐shaped trace Or APTEM‐A10 >> EXTEM‐A10 or EXTEM‐LY30 > 10 % |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | Intraoperative | TEG and h‐TEG |

Hct < 25% (21% accepted during CPB) and bleeding (> 100 mL in 3 min or absence of visible clots) |

h‐TEG‐R > 20 min and bleeding (> 100 mL in 3 min or absence of visible clots) | TEG‐MA < 45 mm and platelet count < 100,000/µL and bleeding (> 100 mL in 3 min or absence of visible clots) | TEG‐R > 2 x h‐TEG‐R | p‐fibrinogen < 100 mg/dL and bleeding (> 100 mL in 3 min or absence of visible clots) | LY30 > 7.5% (if needed beyond standard protocol) |

| Wang 2010 | Unclear/most likely only intraoperative | TEG | hb < 8 g/dL | TEG‐R > 10 min | TEG‐MA < 55 mm | ‐ | TEG‐alpha‐angle < 45 degrees | LY30, no limit stated |

| Weber 2012 | Intra‐ and postoperative | ROTEM (HEPTEM, FIBTEM, INTEM, EXTEM) | Hb < 6 g/dL during CPB and < 8 g/dL after CPB | EXTEM‐CT > 80 S or HEPTEM‐CT > 240 S | EXTEM‐A10 < 40 mm and FIBTEM‐A10 > 10 mm or MULTIPLATE (TRAP < 50 AU and/or ASPI < 30 AU and/or ADP < 30 AU*) | ACT > 130 and INTEM‐CT > 240 sec and HEPTEM‐CT/INTEM‐CT < 0.8 | EXTEM‐A10 < 40 mm and FIBTEM –A10 < 10 mm | Antifibrinolytic therapy consisted of the application of 2 g tranexamic acid after the induction of anaesthesia, and another 2 g was added into the priming volume of the heart–lung machine and again during CPB |

| Westbrook 2009 | Intra‐ and postoperative | TEG, h‐TEG and Platelet Mapping |

hb < 7 g/dL | h‐TEG‐R > 11 min and persisting bleeding (> 60 mL in first 30 min after protamine or > 60 mL/hour in ICU) | h‐TEG‐MA ≤ 41 mm and persisting bleeding (> 60 mL in first 30 min after protamine or > 60 mL/hour in ICU) | TEG‐R –h‐TEG‐R ≥ 3 min | h‐TEG‐MA > 45 and ‐TEG‐alpha‐angle < 45 degrees | LY30 > 15% |

*In addition: prothrombin complex concentrate if APTEM‐CT > 120 sec; **in addition: desmopressin if persisting bleeding and prolonged PFA‐100 channel closure time; ***in addition: desmopressin singular therapy approach for first time confirmed platelet dysfunction. ‐A10: ROTEM value measured early at 10 min; ACT: activated clotting time; ADP: multiplate test; APTEM: aprotinin test of ROTEM; aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; ASPI: multiplate test; AU: arbitrary aggregation units; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; ‐CT: clot formation time; EXTEM: extrinsic system screen test; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; FIBTEM: fibrinogen test of ROTEM; h‐: heparin cup; hb: haemoglobin; Hct: haematocrit; HEPTEM: heparin test of ROTEM; ICU: intensive care unit; INTEM: intrinsic system screen test; LY30: Lysis time at 30 min; ‐MCF: maximum clot firmness; p‐: plasma; PLT: platelet transfusion data; PT: prothrombin time; RBC: red blood cell; ROTEG: rotational TEG; ROTEM: rotational thromboelastometry; TEG: thromboelastography; TEG‐R: thromboelastography reaction time; TEG‐MA: thromboelastography maximum amplitude; TRAP: thrombin receptor activating peptide multiplate test;

Included studies

We included 17 trials, of which two included only paediatric participants. The sample size varied from 28 participants to 224. One trial was conducted in a liver transplant setting (Wang 2010), another in wound excisions of burns patients (Schaden 2012), while the remaining trials (96% (1435) of included patients) were conducted in a cardiac surgery setting (see Table 10; Characteristics of included studies). The majority of trials applied the intervention algorithm intra‐ and postoperatively even if some only included the first two hours postoperatively. Fibrinogen substitution with fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate was described as part of eight interventional trial algorithms (Table 11). Follow‐up ranged from 24 hours to three years, but information on six trials was unclear or did not provide data on the length of follow‐up (see Table 10; Characteristics of included studies; Ak 2009; Cui 2010; Kempfert 2011; NCT00772239; Nuttal 2001; Royston 2001).

Four of the trials were stopped early either due to either futile inclusion (Kempfert 2011; NCT00772239; Paniagua 2011), or a positive interim analysis (Weber 2012). In ten trials, the transfusion strategy in the control group was at the clinicians' discretion in combination with standard laboratory tests (Ak 2009; Cui 2010; Girdauskas 2010; Kultufan Turan 2006; Nuttal 2001; Royston 2001; Schaden 2012; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Rauter 2007; Westbrook 2009). Seven trials compared TEG or ROTEM versus a transfusion algorithm solely based on standard laboratory tests and without clinicians' discretion (Avidan 2004; Kempfert 2011; Nakayama 2015; NCT00772239; Paniagua 2011; Wang 2010; Weber 2012). Five trials used TEG or ROTEM in combination with other devices in the intervention group: Avidan 2004 also used PFA‐100 and Hepcon, Nuttal 2001 used Coagucheck Plus and Coulter‐MPIII, Westbrook 2009 used Platelet Mapping, Weber 2012 used Multiplate, and Shore‐Lesserson 1999 used platelet count and plasma fibrinogen concentration (Table 5).

10. Comparisons and interventional devices.

| Intervention device/comparison | TEG or ROTEM alone | TEG or ROTEM in combination with SLTs | TEG or ROTEM in combination with platelet function analysis |

| Clinical judgement or usual treatment |

Ak 2009; Cui 2010; Girdauskas 2010; Kultufan Turan 2006; Rauter 2007; Royston 2001; Schaden 2012 |

Nuttal 2001; Shore‐Lesserson 1999 |

Westbrook 2009 |

| SLT‐guided algorithm | Kempfert 2011; Nakayama 2015; Paniagua 2011; Wang 2010 | Avidan 2004; Weber 2012 |

ROTEM: rotational thromboelastometry; SLT: standard laboratory tests; TEG: thromboelastography In the NCT00772239 we did not have information on the comparison.

Half of the studies used ROTEM and half used TEG, with the majority of new trials using ROTEM (see Characteristics of included studies; Table 10; Table 11; Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Excluded studies

In this update we excluded 94% (282/300) of publications assessed as full‐text (Figure 7), with the 44 most relevant new publications described in Characteristics of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion.

Ongoing studies

We included a total of six ongoing studies in this review (NCT02352181; NCT02593877; NCT02461251; NCT01536496; NCT02416817; NCT01402739). In the first published version of this review we found two ongoing trials (Afshari 2011): one which is included as Weber 2012 while NCT00772239, despite being included, had no published data and was terminated due to futile inclusion. The six ongoing trials include three trauma trials using TEG (NCT01536496; NCT02416817) and TEG or ROTEM (NCT02593877), one obstetric (NCT02461251), and one cardiac surgery using ROTEM (NCT01402739), and finally one in a liver transplantation setting using ROTEM (NCT02352181).

Awaiting classification

No studies are awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

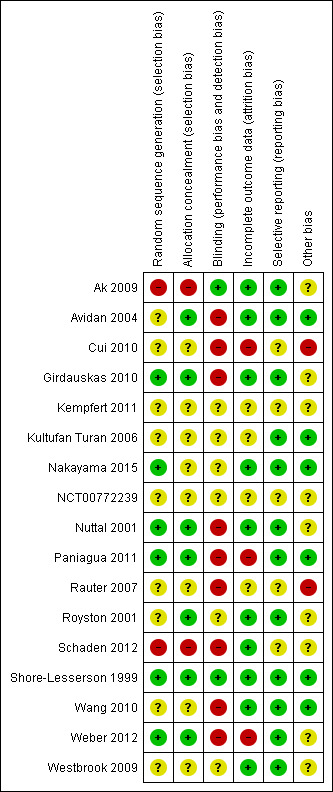

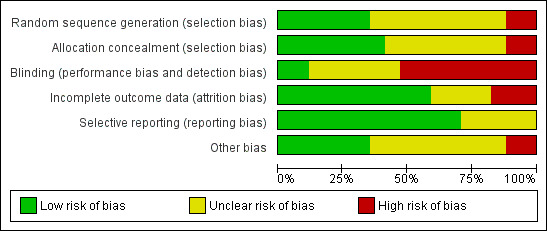

We evaluated the overall quality of trials based on the major sources of bias (domains) as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies. We classified only two trials at overall low risk of bias (Nakayama 2015; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Figure 9). For a more detailed description of individual trial qualities see the table Characteristics of included studies. The various bias domains are presented in the 'Risk of bias' summary figure and a 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 9; Figure 10).

9.

Updated risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

10.

Updated risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation was adequately reported in six trials (35%) (Girdauskas 2010; Nakayama 2015; Nuttal 2001; Paniagua 2011; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Weber 2012), while allocation concealment was adequately reported in seven trials (41%) (Avidan 2004; Girdauskas 2010; Nuttal 2001; Paniagua 2011; Royston 2001; Shore‐Lesserson 1999;Weber 2012).

Blinding

Adequate blinding in trials using transfusion strategy remains a challenge and many of the authors claimed to have adequate blinding. Indeed the trials did provide data, but on different levels of blinding. In our opinion, blinding of clinicians and participants in the operating theatre was the most important (performance bias). However,the masking of assessors of bleeding measurement and transfusion requirements (detection bias) is also very important. Lack of blinding or insufficient blinding in the operating theatre does raise doubts about the degree of critical information being passed on postoperatively to those responsible for the care and treatment of the patient.

Only two trials provided sufficient data to be categorized as blinded (12%) (Ak 2009; Shore‐Lesserson 1999). The remaining trials were either open‐label or did not provide sufficient data on how adequate blinding was achieved (Characteristics of included studies; Figure 9; Figure 10).

Incomplete outcome data

Ten (60%) of the trials performed their analysis according to the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) method or provided sufficient data to perform ITT analyses (Ak 2009; Avidan 2004; Girdauskas 2010; Nakayama 2015; Nuttal 2001; Royston 2001; Schaden 2012; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Wang 2010; Westbrook 2009); the remaining studies were unclear about application of ITT. Additionally, some of the trials did not provide explicit information on the length of the longest follow‐up (Table 10). Many of our analyses were subject to limitations due to demonstration of therapeutic effect in graphic form and without numerical data in the publications.

Selective reporting

Twelve trials appeared to be free of selective reporting; judged in comparison to trial registration (Ak 2009; Avidan 2004; Girdauskas 2010; Kultufan Turan 2006; Nakayama 2015; Nuttal 2001; Paniagua 2011; Royston 2001; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Wang 2010; Weber 2012; Westbrook 2009), protocol provided by authors (Paniagua 2011), or based on available information in the publication. Additionally, only eight trials provided data on our primary outcome, mortality (Ak 2009; Girdauskas 2010; Nakayama 2015; Paniagua 2011; Royston 2001; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Wang 2010; Weber 2012), with two of them being zero event trials (Nakayama 2015; Royston 2001).

Other potential sources of bias

Eight trials disclosed the funding source and were defined as not for profit (Avidan 2004; Kultufan Turan 2006; Nakayama 2015; Paniagua 2011; Schaden 2012; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Wang 2010Weber 2012), while the funding source for the rest was defined as unknown. Three of the independently funded trials have authors with relations to TEM innovations (Nakayama 2015; Schaden 2012; Weber 2012). Sample size calculation was reported in ten trials (Ak 2009; Avidan 2004; Girdauskas 2010; Nakayama 2015; Nuttal 2001; Paniagua 2011; Royston 2001; Schaden 2012; Shore‐Lesserson 1999; Weber 2012), but none were powered to show a statistically significant benefit in mortality. One trial was stopped early due to benefits (Weber 2012), and two due to slow enrolment or lack of funding (NCT00772239; Paniagua 2011).

Pooling trials with different follow‐up on mortality might bias the result caused by potential differences in the underlying mechanism. However, all included trials but one used hospital admission as the longest follow‐up (Wang 2010).

The funnel plot of standard error versus risk ratio for overall longest follow‐up mortality showed a symmetrical distribution that indicated no publication bias. Analyses of the impact of TEG and ROTEM on bleeding were hindered due to application of different indicators of bleeding and transfusion, different time points for measurement, and demonstration of therapeutic effect in graphic form without numerical data.

Other clinical outcome variables in line with our defined primary and secondary outcomes were inconsistently reported. In general, trials provided data with very skewed distribution of continuous outcomes such as bleeding, amount of blood products transfused, length of stay in ICU or hospital and time to extubation. Following statistical consultation with a Cochrane statistical editor and after re‐evaluation of the available data, we abstained from performing meta‐analyses, since the data were considered substantially skewed. As a consequence, the results of the included trials are summarized in tables demonstrating the distribution of each continuous outcome (Table 12; Table 13; Table 14; Table 15; Table 16; Table 17; Table 18).

3. Continous outcome data: bleeding volume (mL), longest follow‐up.

| Study | Data available | Intervention results | Control results |

P value for difference between groups |

| Ak 2009 | Mean (SD) | 481 (351) | 591 (339) | 0.087 |

| Avidan 2004 | Median (IQR) | 755 (606; 975) | 850 (688; 1095) | > 0.05 |

| Cui 2010* | Median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.6; 0.9) | 0.6 (0.4; 0.8) | 0.092 |

| Girdauskas 2010 | Median (IQR) | 890 (600; 1250) | 950 (650; 1400) | 0.50 |

| Kempfert 2011 | Mean (SD) | 1599 (834) | 1867 (827) | 0.066 |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | Mean (SD) | 838 (494) | 711 (489) | 0.581 |

| Nakayama 2015** | Median (IQR) | 13 (9; 12) | 22 (13; 35) | 0.002 |

| NCT00772239 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nuttal 2001 | Median (range) | 590 (240; 2335) | 850 (290; 10190) | 0.019 |

| Paniagua 2011 | Mean (SD) | 2408 (1771) | 2736 (1617) | ‐ |

| Rauter 2007 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Royston 2001 | Median (IQR) | 470 (295; 820) | 390 (240; 820) | ‐ |

| Schaden 2012 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | Mean (SD) | 720 (500) | 901 (847) | 0.27 |

| Wang 2010 | Mean (SD) | 4776 (4265) | 6348 (3704) | > 0.05 |

| Weber 2012 | Median (IQR) | 600 (263; 875) | 900 (600; 1288) | 0.021 |

| Westbrook 2009 | Median (IQR) | 875 (755; 1130) | 960 (820; 1200) | 0.437 |

*Data given in mL/kg/hour; **data given in mL/kg; ‐ indicates that data were not reported; significant result is highlighted with bold text. IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation

4. Continous outcome data: total PRBC transfusion.

| Study | Reported unit | Data available | Intervention results | Control results |

P value for difference between groups |

| Ak 2009 | Units | Median (IQR) | 1 (0; 1) | 1 (1; 2) | 0.599 |

| Avidan 2004 | mL | Median (IQR) | 500 (0; 678) | 495 (0; 612) | 0.03 |

| Cui 2010 | Units | Median (IQR) | 1 (1; 1) | 1 (0.7; 1.9) | > 0.05 |

| Girdauskas 2010 | Units | Median (IQR) | 6 (2; 13) | 9 (4; 14) | 0.20 |

| Kempfert 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | Units | Median (IQR) | 0 (0; 3) | 1 (0; 2) | 0.100 |

| Nakayama 2015 | mL/kg | Mean (IQR) | 22 (11; 34) | 30 (20; 39) | 0.02 |

| NCT00772239 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nuttal 2001 | Units | Median (range) | 2 (0; 9) | 3 (0; 70) | 0.039 |

| Paniagua 2011 | mL | Mean (SD) | 1774 (1394) | 1604 (1366) | ‐ |

| Rauter 2007 | Units | Mean | 0.8 | 1.3 | * |

| Royston 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Schaden 2012 | Units | Mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.1) | 4.8 (3.0) | 0.12 |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | mL | Mean (SD) | 354 (487) | 475 (593) | 0.12 |

| Wang 2010 | Units | Mean (SD) | 14.2 (7.1) | 16.7 (12.8) | > 0.05 |

| Weber 2012 | Units | Median (IQR) | 3 (2; 6) | 5 (4; 9) | < 0.001 |

| Westbrook 2009 | Units | Total | 14 | 33 | ** |

*P value is reported as < 0.05, but seems to be calculated based on units given to each group instead of mean/median, thereby wrongly assuming that each of the units given are independent; **P value is reported as 0.12, but is calculated based on units given to each group instead of mean/median, thereby wrongly assuming that each of the units given are independent; ‐ indicates that data were not reported; significant result is highlighted with bold text. IQR: interquartile range; PRBC: pooled red blood cell; SD: standard deviation

5. Continous outcome data: total FFP transfusion.

| Study | Reported unit | Data available | Intervention results | Control results |

P value for difference between groups |

| Ak 2009 | Units | Median (IQR) | 1 (1; 1) | 1(1; 2) | 0.001 |

| Avidan 2004 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cui 2010 | mL | Mean (SD) | 719 (216) | 883 (335) | < 0.05 |

| Girdauskas 2010 | Units | Median (IQR) | 3 (0; 12) | 8 (4; 18) | 0.01 |

| Kempfert 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | Units | Mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.95) | 2.7 (1.5) | 0.403 |

| Nakayama 2015 | mL/kg | Median (IQR) | 26 (16; 31) | 25 (12;41) | 0.87 |

| NCT00772239 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nuttal 2001 | Units | Median (range) | 2 (0‐10) | 4 (0‐75) | 0.005 |

| Paniagua 2011 | mL | Mean (SD) | 799 (1188) | 707 (997) | ‐ |

| Rauter 2007 | Units | Total | 0 | 4 | ‐ |

| Royston 2001 | Units | Total | 5 | 16 | * |

| Schaden 2012 | Units | Median (IQR) | 0 (0; 0) | 5.0 (1.5‐7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | mL | Mean (SD) | 36 (142) | 217 (436) | < 0.04 |

| Wang 2010 | Units | Mean (SD) | 12.8 (7.0) | 21.5 (12.7) | < 0.05 |

| Weber 2012 | Units | Median (IQR) | 0 (0; 3) | 5 (3; 8) | < 0.001 |

| Westbrook 2009 | Units | Total | 22 | 18 | ‐ |

*P value is reported as < 0.05, but seems to be calculated based on units given to each group instead of mean/median, thereby wrongly assuming that each of the units given are independent; ‐ indicates that data were not reported; significant result is highlighted with bold text. FFP: fresh frozen plasma; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation

6. Continous outcome data: total platelet transfusion.

| Study | Reported unit | Data available | Intervention results | Control results |

P value for difference between groups |

| Ak 2009 | Units | Median (IQR) | 1 (1; 1) | 1 (1; 2) | 0.001 |

| Avidan 2004 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cui 2010 | Units | Median (IQR) | 1 (1; 1) | 1 (0.7‐1.9) | > 0.05 |

| Girdauskas 2010 | Units | Median (IQR) | 2 (2; 3) | 2 (2;3) | 0.70 |

| Kempfert 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | Median (IQR) | 0 (0; 4) | 0 (0;0) | 0.411 | |

| Nakayama 2015 | mL/kg | Median (IQR) | 0 (0; 25) | 0 (0;17) | 0.28 |

| NCT00772239 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nuttal 2001 | Units | Median (range) | 6 (0‐18) | 6 (0‐144) | 0.0001 |

| Paniagua 2011 | mL | Mean (SD) | 212 (307) | 331 (406) | ‐ |

| Rauter 2007 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Royston 2001 | Units | Total | 1 | 9 | * |

| Schaden 2012 | Units | Median (range) | 0 (0‐0) | 0 (0‐2) | 0.12 |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | mL | Mean (SD) | 34 (94) | 83 (160) | 0.16 |

| Wang 2010 | Units | Mean (SD) | 27.5 (13.9) | 30.1 (18.5) | > 0.05 |

| Weber 2012 | Units | Median (IQR) | 2 (0; 2) | 2 (0; 5) | 0.010 |

| Westbrook 2009 | Units | Total | 5 | 15 | ‐ |

*P value is reported as < 0.05, but seems to be calculated based on units given to each group instead of mean/median, thereby wrongly assuming that each of the units given are independent; ‐ indicates that data were not reported; significant result is highlighted with bold text. IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation

7. Continous outcome data: length of stay in hospital (days).

| Study | Data available | Intervention results | Control results |

P value for difference between groups |

| Ak 2009 | Mean (SD) | 6.2 (1.1) | 6.3 (1.4) | 0.552 |

| Avidan 2004 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cui 2010 | Median (IQR) | 21 (15.5; 30.0) | 32 (24.3; 40.3) | 0.006 |

| Girdauskas 2010 | Mean (SD) | 16.6 (16.4) | 17.0 (14.8) | 0.80 |

| Kempfert 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nakayama 2015 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| NCT00772239 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nuttal 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Paniagua 2011 | Mean (SD) | 13.6 (7.1) | 25.8 (19.2) | ‐ |

| Rauter 2007 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Royston 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Schaden 2012 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Wang 2010 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Weber 2012 | Median (IQR) | 12 (9;22) | 12 (9; 23) | 0.718 |

| Westbrook 2009 | Median (IQR) | 9 (7‐13) | 8 (7‐12) | > 0.05 |

‐ Indicates that data were not reported; significant result is highlighted with bold text. IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation

8. Continous outcome data: length of stay in intensive care unit (hours).

| Study | Data available | Intervention results | Control results |

P value for difference between groups |

| Ak 2009 | Mean (SD) | 23.3 (5.7) | 25.3 (11.2) | 0.099 |

| Avidan 2004 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cui 2010 | Median (IQR) | 137 (106; 161) | 173 (138; 477) | 0.009 |

| Girdauskas 2010 | Mean (SD) | 175.2 (218.4) | 194.4 (201.6) | 0.6 |

| Kempfert 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nakayama 2015 | Median (IQR) | 60 (35; 81) | 71 (60; 108) | 0.014 |

| NCT00772239 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nuttal 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Paniagua 2011 | Mean (SD) | 132 (120) | 236 (168) | ‐ |

| Rauter 2007 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Royston 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Schaden 2012 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Wang 2010 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Weber 2012 | Median (IQR) | 21 (18‐31) | 24 (20‐87) | 0.019 |

| Westbrook 2009 | Median (IQR) | 29.4 (14.3; 56.4) | 32.5 (22.0; 74.5) | 0.369 |

‐ Indicates that data was not reported; Significant result is highlighted with bold text. IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation

9. Continous outcome data: time to extubation (hours).

| Study | Data available | Intervention results | Control results |

P value for difference between groups |

| Ak 2009 | Mean (SD) | 8.2 (2.1) | 7.9 (4.7) | 0.540 |

| Avidan 2004 | Median (IQR) | 4.4 (3.0; 6.2) | 4.3 (3.0; 5.9) | > 0.05 |

| Cui 2010 | Median (IQR) | 40.0 (25.5; 75.0) | 106.5 (54.8; 196.5) | 0.009 |

| Girdauskas 2010 | Mean (SD) | 144 (139) | 137 (172) | 0.8 |

| Kempfert 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kultufan Turan 2006 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nakayama 2015 | Median (IQR) | 3 (2; 17) | 4 (2; 23) | 0.06 |

| NCT00772239 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nuttal 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Paniagua 2011 | Mean (SD) | 15.6 (12.3) | 32.0 (59.0) | ‐ |

| Rauter 2007 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Royston 2001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Schaden 2012 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Shore‐Lesserson 1999 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Wang 2010 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Weber 2012 | Median (IQR) | 21 (18; 31) | 24 (20; 87) | 0.019 |

| Westbrook 2009 | Median (IQR) | 8 (5.3; 19.8) | 10.3 (5.8; 19.5) | ‐ |

‐ Indicates that data were not reported; significant result is highlighted with bold text. IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Thromboelastography (TEG) or thromboelastometry (ROTEM) versus any comparison.

| TEG or ROTEM versus any comparison for adults or children with bleeding | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults or children with bleeding Setting: majority of participants were undergoing cardiac surgery involving cardiopulmonary bypass in a high‐income hospital setting Intervention: TEG or ROTEM‐guided haemostatic transfusion Comparison: any comparison | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with any comparison | Risk with TEG or ROTEM | |||||

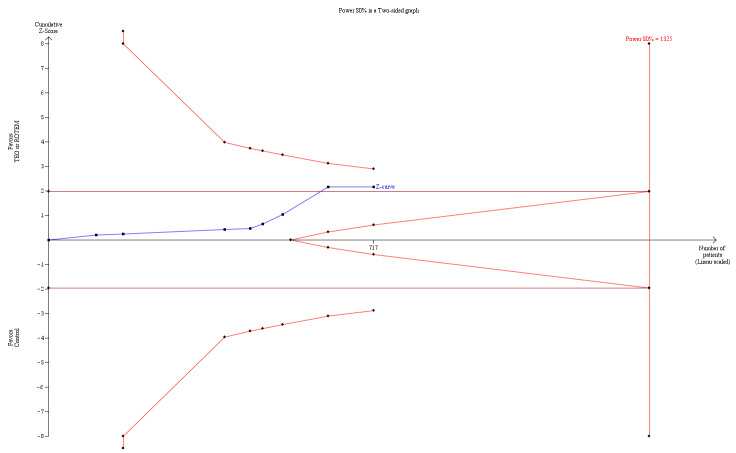

| Mortality longest follow‐up | Study population | RR 0.52 (0.28 to 0.95) | 717 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | TSA shows that only 54% of the required information size (717 of 1325) has been reached (Effects of interventions, Figure 1). 1 |

|

| 74 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (21 to 70) | |||||

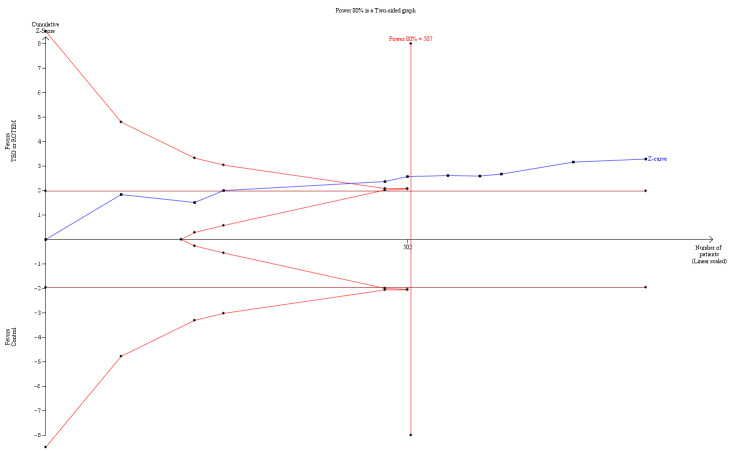

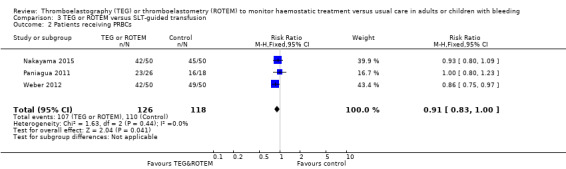

| Proportion of patients receiving PRBCs | Study population | RR 0.86 (0.79 to 0.94) | 832 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | TSA indicates firm evidence (Effects of interventions; Figure 2).2 | |

| 720 per 1000 | 619 per 1000 (568 to 676) | |||||

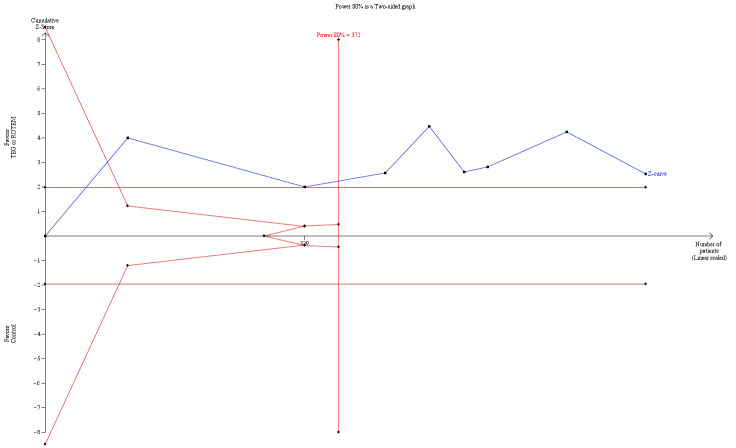

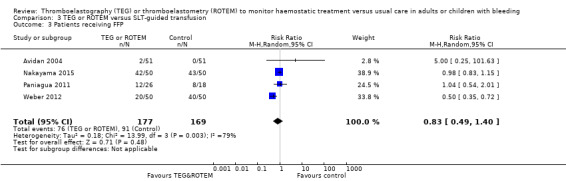

| Proportion of patients receiving FFP | Study population | RR 0.57 (0.33 to 0.96) | 761 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | TSA indicates firm evidence (Effects of interventions; Figure 3)3 | |

| 471 per 1000 | 268 per 1000 (155 to 452) | |||||

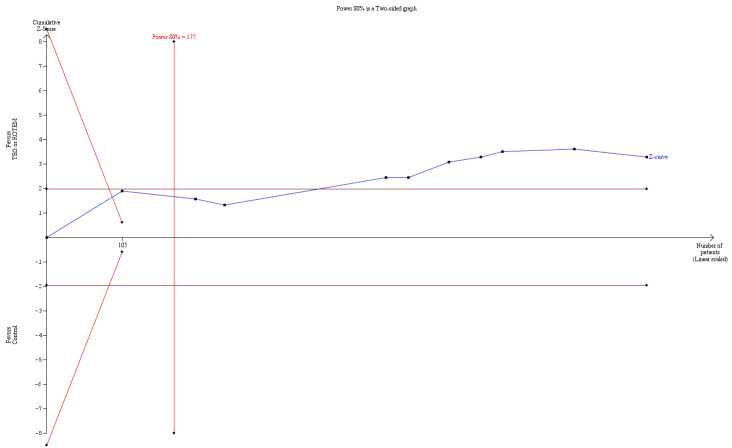

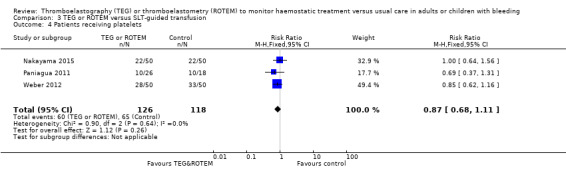

| Proportion of patients receiving platelets | Study population | RR 0.73 (0.60 to 0.88) | 832 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | TSA indicates firm evidence, but the low risk of bias adjusted required information size has not been reached (Effects of interventions; Figure 4). 4 |

|

| 344 per 1000 | 251 per 1000 (206 to 303) | |||||

| Rate of surgical reintervention | Study population | RR 0.75 (0.50 to 1.10) | 887 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | TSA showed a beneficial effect in favour of TEG/ROTEM‐guided transfusion management (Effects of interventions; Figure 5).5 | |

| 108 per 1000 | 81 per 1000 (54 to 119) | |||||

| Excessive bleeding events and massive transfusion | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.38 to 1.77) | 280 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Unable to carry out TSA because of the limited amount of data. | |

| 137 per 1000 | 112 per 1000 (52 to 242) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; PRBC: pooled red blood cell; ROTEM: thromboelastometry; RR: risk ratio; TEG: thromboelastography; TSA: trial sequential analysis | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Quality of the evidence (GRADE) adjusted due to high risk of bias and imprecision.Two trials were zero event trials (Nakayama 2015; Royston 2001). Only two studies had low risk of bias (Nakayama 2015; Shore‐Lesserson 1999), and none of the included trials in this analysis were powered to detect any difference for mortality. Changing from fixed‐effect model to random‐effects model changes the risk estimate to RR 0.57 (95% CI 0.30 to 1.07). The majority of patients are included in cardiac surgery setting, thus reducing generalizability and external validity of the finding.

2Quality of the evidence (GRADE) was adjusted due to high risk of bias and indirectness. Only two trials had low risk of bias (Nakayama 2015; Shore‐Lesserson 1999). The direction of the effect estimate is consistent across the included trials and for the transfusion outcomes.

3Quality of the evidence (GRADE) was adjusted due to high risk of bias and imprecision. Only two trials had low risk of bias (Nakayama 2015; Shore‐Lesserson 1999). The direction of the effect estimate is consistent across the included trials and for the transfusion outcomes.

4Quality of the evidence (GRADE) was adjusted due to high risk of bias and indirectness. Only two trials had low risk of bias (Nakayama 2015; Shore‐Lesserson 1999). The direction of the effect estimate is consistent across the included trials and for the transfusion outcomes.

5Quality of the evidence (GRADE) was adjusted due to high risk of bias and imprecision. Only one trial had low risk of bias (Shore‐Lesserson 1999). Event rate of surgical reintervention was low overall. Inclusion of trials with coagulopathy or excessive bleeding as inclusion criteria might change this effect estimate.

6Quality of the evidence (GRADE) was adjusted due to high risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision. Only two trials, both with high risk of bias, were included in this analysis (Ak 2009; Girdauskas 2010). Few events were reported, but the direction of the effect was consistent.

Summary of findings 2. Thromboelastography (TEG) or thromboelastometry (ROTEM) compared to clinical judgement or usual care in adults or children with bleeding.

| TEG or ROTEM compared to clinical judgement or usual care in adults or children with bleeding | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults or children with bleeding Setting: majority of participants were undergoing cardiac surgery involving cardiopulmonary bypass in a high‐income hospital setting Intervention: TEG or ROTEM Comparison: clinical judgement or usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with clinical judgement or usual care | Risk with TEG or ROTEM | |||||

| Mortality | Study population | RR 0.81 (0.32 to 2.01) | 445 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) adjusted due to high risk of bias and imprecision. | |

| 41 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (13 to 82) | |||||

| Proportion of patients receiving PRBCs | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.73 to 1.00) | 486 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) adjusted due to high risk of bias and imprecision. | |

| 622 per 1000 | 529 per 1000 (454 to 622) | |||||

| Proportion of patients receiving FFP | Study population | RR 0.38 (0.21 to 0.68) | 415 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) adjusted due to high risk of bias and imprecision. | |

| 415 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 (87 to 283) | |||||

| Proportion of patients receiving platelets | Study population | RR 0.59 (0.43 to 0.80) | 486 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) adjusted due to high risk of bias and imprecision. | |

| 311 per 1000 | 184 per 1000 (134 to 249) | |||||

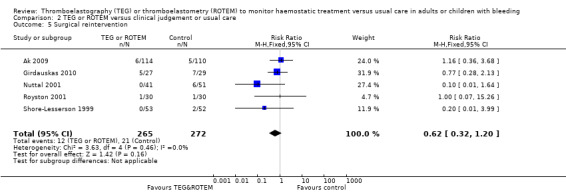

| Rate of surgical reintervention | Study population | RR 0.62 (0.32 to 1.20) | 537 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) adjusted due to high risk of bias and imprecision. | |

| 77 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (25 to 93) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; PRBC: pooled red blood cell; ROTEM: thromboelastometry; RR: risk ratio; TEG: thromboelastography. | ||||||