Abstract

The authors review policy initiatives and professional organization position statements that hospital and nursing administrators should be familiar with to respond effectively to public and policymaker concerns about substance use in healthcare settings. Detecting and addressing substance use disorders proactively and systematically are essential for 2 reasons: to protect patient safety and to enable healthcare professionals to recognize problems early and intervene swiftly. The authors identify key points and gaps in existing policy statements.

Hospital and nursing administrators must address the issue of substance abuse disorders (SUDs) among staff and students practicing in clinical settings. For the purposes of this article, we define SUDs as the abuse of, misuse of, or dependency on alcohol or drugs. Current estimates are that the percentage of nurses with dependency ranges from 2% to 10%, and estimates of misuse and abuse may exceed 14% to 20%.1–11 Considering the wide variation in the incidence of SUDs reported among nurses in the literature, we caution against using any one number. Moreover, the exact numbers of nurses with an SUD is difficult to estimate.12 To appreciate the severity of this issue, one needs to look no further than the state level. The Alabama State Board of Nursing identifies an average of 300 nurses per year for alcohol/substance abuse issues.13 The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) has 59 member boards, most of them in states with a greater population than Alabama.14 Generally half of nurses who attempt recovery succeed, with many state monitoring programs reporting success rates from 48%15 to 90%.16 A conservative estimate is that 750 nurses per month, or 9,000 per year, are reentering the workforce while in recovery from an SUD, equaling nearly the entire combined nursing workforce of Alaska and Wyoming.17,18 Because the monitoring and rehabilitation of recovering nurses have been in place beginning in the early 1980s,19 over the last 3 decades more than 250,000 may have returned to work.

The impact on the workforce and therefore patient care if nurses in recovery were removed from practice can be illustrated in a calculation of direct hours of patient care. For example, 9,000 nurses employed at 2,000 hours a year (50 weeks) would provide 18 million hours of direct patient care in single year. The current and predicted shortage of nurses is well documented. The US Department of Labor’s “Occupational Employment Projections for 2010”20 indicates that the nation will need to train 1.1 million new nurses by 2012 and that the number of nurses needed will grow by 27% that same year.21 Monitoring programs that help nurses reenter the workforce while recovering from an SUD will play a vital role in ensuring sufficient numbers of healthcare providers in the United States.

This article provides healthcare administrators with information about the treatment of nurses with SUDs by providing an overview of position statements and policy recommendations from key nursing organizations in the United States and abroad. This information should facilitate discussion of this daunting issue with the public, as well as all those who have a stake in protecting patient safety and retaining skilled nursing professionals.

Background

Recently, media stories have described instances of nurses impaired by drugs or alcohol who may steal drugs from the workplace. For example, Lindsay Peterson22 of the Tampa Tribune reported that neither the local police nor the Florida State Board of Nursing was notified about an incident involving a nurse who diverted (stole) medication. The implication was that the nurse was not subject to sanction for this behavior. However, in Florida, nurses with an SUD are usually referred to a confidential alternative-to-discipline (ATD) drug program and may or may not serve prison time, depending on the disciplinary approach taken by the employer.22 Peterson22 notes that addiction professionals believe treatment results in better outcomes, which is confirmed by research. The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) recommends that rather than imprison nonviolent substance abusers, drug courts be available to divert such individuals into treatment.23 By increasing direct supervision of offenders, coordinating public resources, and expediting case processing, drug courts can help break the cycle of criminal behavior, alcohol and drug use, and incarceration.23 The ONDCP has demonstrated that drug courts reduce crime by lowering rearrest and conviction rates, improve substance abuse treatment outcomes, and reunite families, thus producing measurable cost benefits.23 Alternative-to-discipline programs and drug court programs both offer rehabilitative justice in lieu of incarceration.24

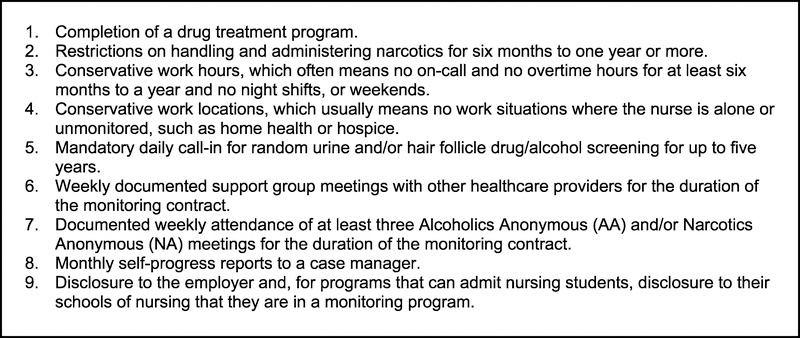

In addition, many laypersons do not understand that the nursing profession is subject to rigorous internal regulation. Policy makers from key nursing organizations in the United States and abroad challenge media portrayals of drug and/or alcohol monitoring programs as convenient places for healthcare providers with SUDs to hide and avoid disciplinary action.22 Most programs enforce rigorous standards that participants must meet in order to reenter practice (Figure 1).25 In those situations where a nurse cannot or will not maintain sobriety, many programs help him/her transition out of the profession. Furthermore, formal disciplinary action by a state nursing board may be warranted, up to and including revocation of licensure.

Figure 1.

Standards for reentry into practice from alternative to discipline programs. Source: Roche.25

Recovery

Because nurse administrators are likely to be working with nurses in various stages of recovery at present and in the future, a brief discussion of recovery, reentry, and recidivism is warranted. Best and colleagues26 conducted a comprehensive review of recovery literature and reported that stable recovery does not happen quickly. The authors found that (a) using personal and social supports is the best predictor of developing effective recovery, (b) barriers to effective recovery include increased problem burdens, poor mental and physical health, and continued alcohol or drug use, and (c) structured drug and alcohol treatment programs (with the highest percentage of recovery reported after 90 days of treatment) followed by continued community support are most effective in achieving and maintaining long-term recovery.27

Best and colleagues defined recovery in 3 domains: (1) remission of substance use disorder, (2) enhancement of global health (physical, emotional, spiritual, occupational, and relational), and (3) community inclusion.27 They identified 3 stages of recovery from an SUD as guidelines for nurse managers: early sobriety (first year), sustained sobriety (1–5 years), and stable sobriety (>5 years).27 Some nursing specialties, such as anesthesia, recommend that nurse anesthetist achieve 1 year of recovery before reentry into clinical practice.28

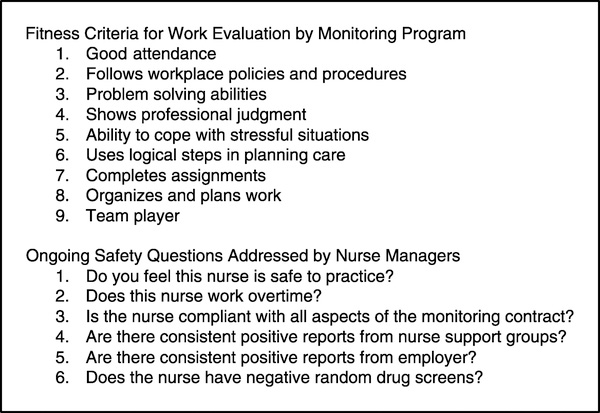

Readiness for reentry should be determined through the collaboration of the monitoring program, a certified drug and alcohol counselor, and the nursing school27 or employer.29 Ideally, the issue of recidivism requires nurse administrators and monitoring programs to communicate effectively in order to develop and enact exemplary policies, which ensure patient safety through swift confrontation and referral if necessary (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Determination of fitness for duty. Linda Smith, Florida Intervention Project for Nurses, personal communication, March 1, 2011.

Position Statements

Professional groups in the United States have long advocated for monitoring programs and the return to work of nurses in recovery. In 1987, the NCSBN developed the first model guidelines for such initiatives.28 Also called “alternative-to-discipline” programs, these strategies were designed to protect the public, which is accomplished by closely assisting nurses in the recovery process and ensuring they are safe to practice.15 In 2007, the NCSBN encouraged the early detection and treatment of nurses with the disease of chemical dependency.29 Many of the ATD programs are noncompulsory and confidential. The underlying philosophy is that nurses will voluntarily seek assistance to combat their SUD, and colleagues will more readily report any concerns if they know such reports will not be made public.

In 2001, the American Nurses Association (ANA) Code of Ethics for Nurses was revised to specifically address impaired practice: “Nurses must be vigilant to protect the patient, the public, and the profession from potential harm when a colleague’s practice, in any setting, appears to be impaired.”30

The code requires that nurses extend compassion and caring to colleagues in recovery. When a nurse suspects another’s practice may be impaired, he/she should take action designed both to protect patients and help the impaired nurse receive assistance in recovery. The code suggests a direct conversation in the form of a planned intervention may be one method for intervening in such situations. The code calls for a return to practice by impaired and recovering nurse colleagues who have received treatment and are ready to resume professional duties.30 Monitoring programs for nurses with SUDs are in accordance with the philosophy of the code. In 2002, the ANA House of Delegates developed a position statement that supported the development of ATD programs and encouraged each state to adopt nonpunitive strategies to address chemical dependency among its membership.30 Currently, 43 states31 have initiated programs that focus on patient protection and retention of recovering nurses.

SUD Among Nursing Students

In 2002, the National Student Nurses Association passed a resolution to encourage schools of nursing to refer students with possible SUDs for assessment and treatment. The resolution called for states to expand the use of existing peer assistance programs to include students in training. This is an important step in identification and treatment, because we know that substance abuse and dependency may begin prior to graduation. Because of the general risk of SUDs among teens and young adults,20 clinical sites and schools of nursing will likely continue to be faced with students with positive drug tests or clinical behaviors that indicate substance abuse.

The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN)32 developed a position statement that recommends that schools of nursing implement nonpunitive policies, including identification of the problem, initiation of an intervention, evaluation by a substance abuse professional, diagnosis of the condition, the beginning of treatment, and reentry into work or school. The AACN guidelines include 4 basic assumptions: (1) substance abuse compromises patient safety, (2) substance abusers may need assistance in identifying their problem, (3) addiction is a disease that can be treated, and (4) students should have an opportunity to receive treatment and continue with their training. Many schools of nursing have taken additional steps to provide assistance to students while protecting the public.27

Policies and Guidelines

Hospital and nursing administrators are charged with the task of formulating such practices and procedures in their healthcare institutions to maintain patient safety while supporting an individual nurse’s recovery. To this end, the guidelines specified by professional groups such as the NCSBN and the ANA can serve as the foundation for a sound and rigorous protocol that addresses the transition of nurses with SUDs as they emerge in the workplace. Protocols should state the ethical obligation of administrators and other nurses to help intervene with a colleague with an SUD. Employers must increase awareness of SUDs through education and support positive and timely action by acknowledging the risks of addiction to the profession—while recognizing that early identification and referral will improve the management of risk.

Policies should address regulatory obligations of the nursing administrator and nurse employee—concerning either the proper administration of controlled substances and/or reporting a nurse to the appropriate state entity, such as the licensing board and/or the alternative program. Implementation of comprehensive policies and procedures helps ensure that the health and welfare of all involved—the affected nurse, the nurse’s patients, and the nurse’s coworkers—are addressed. Such protocols may serve to enhance workforce morale and positive perception of hospital administration. Proactive polices may help reduce the stigma attached to a disease that has too often been misunderstood, hidden and not discussed, and infrequently acted upon by those most responsible for doing so.

International Professional Organizations’

Position Statements

Programs offering monitoring and peer assistance for nurses with an SUD are now recognized internationally as the optimal evidence-based method for protecting the public and acting in the best interests of the profession. In its 1995 position paper,33 the International Nurses Society on the Addictions (IntNSA) recognized that nurses are not immune to addictive disease; rather, the rates of SUDs among nurses are similar to those in the general population—and in some specialties, such as critical care and anesthesia, even greater. The IntNSA expressed concerns regarding the loss to the profession due to addiction, related to “professional denial of the problem; judgmental attitudes regarding impaired healthcare providers; and lack of knowledge of impairment, prevention, early intervention programs, and available referral, treatment, and support.”33

The IntNSA has promoted the adoption of a consistent mechanism for identifying, intervening, treating, and supporting nurses with addictive diseases by healthcare employers and institutions, emphasizing 3 specific areas for improvement: (1) increasing education so that all colleagues—including students, faculty, and nurses employed in various institutions—are educated about substance abuse conditions, legal and ethical responsibilities, prevention, intervention skills and reentry considerations; (2) instituting workplace policies so that a proactive, systematic, and cost-effective approach to substance abuse based on research and evidence is adopted; and (3) incorporating peer assistance and monitoring programs for nurses on a broad international scale so that they are initiated in all countries and states.32 The IntNSA, like other professional nursing organizations, believes that nurses who have SUDs can successfully transition to safe practice with the appropriate treatment, monitoring, and support.

Case Study: Canada

In 2009, the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA)34 developed a position statement entitled “Problematic Substance Use by Nurses,”4 which viewed substance abuse by nurses in Canada as a critical issue because of the potential negative impact on persons receiving care, on the public trust, and on the nursing profession. The CNA determined that, when a nurse exhibits inappropriate behavior, intervention is required for the protection of patients rather than punishment of the nurse. If nurses demonstrating substance abuse do not receive help, they are in danger of harming patients, themselves, and colleagues.34 This can lead to damaging effects on the public’s trust in the employer, with the individual, and among the profession.34 Many Canadian provinces such as Manitoba34 have monitoring programs already in place and use the CNA guidelines to protect the public through vigilant monitoring and reentry of nurses from recovery.

Case Study: Australia

The Nursing and Midwifery Health Program (NMHP) located in Victoria, Australia,35 is an independent support service for nurses, midwives, and students of nursing and midwifery experiencing health problems related to substance use or mental illness. The NMHP provides screening, assessment, referrals, and individual and group support sessions for nurses seeking help to manage these concerns.35 The program is guided by the belief that early intervention is the best way to address problems. Nurses are encouraged to voluntarily contact the NMHP in addition to managers and human resources personnel who may have identified nurses experiencing these types of issues.35 Similar to other monitoring programs elsewhere in the world, the NMHP values participants’ confidentiality and—unless compelled by law or with consent—the names of participants are not divulged to anyone, a policy that is in compliance with the privacy act of Australia.35

Identified Gaps in Policy Statements

Our review of policy statements offers nurse administrators a useful foundation for addressing the concerns of the public, the media, and their home institutions in formulating and implementing SUD policies. In 2001, the ANA published a handbook for nurse managers regarding the identification and treatment of the chemically dependent employee.2 The NCSBN is developing new guidelines for substance abuse monitoring programs, scheduled to be released in 2011. (Preliminary data are available at the NCSBN home page: https://www.ncsbn.org/Alternative_Program_Survey_Results.pdf.) On the basis of our review of policy statements and current directions in the treatment of the SUD nursing professionals on a national and international basis, a set of key points and gaps has been identified (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key Points and Gaps in Professional Nursing Organization Substance Abuse Policies (National and International)

| Key Points | Gaps |

|---|---|

| (1) Alcoholism and drug addiction are considered treatable diseases. | (1) How many drug or alcohol relapses are allowed before disciplinary action is taken? |

| (2) Primary purpose of all drug/alcohol monitoring programs is to protect the public. | (2) How can nurse executives help prevent poor patient outcomes attributed to employees with SUDs? |

| (3) Public protection is achieved by providing an avenue for nurses to self-report or report a colleague in need of assistance without fear of punitive outcomes. | (3) How do nurse executives educate and implement intervention training with staff? |

| (4) Forty-three US states and territories in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia have monitoring programs in place for nurses. | (4) How are drug screening tests used in the facility and what is the process? |

| (5) Student nurses should be given the opportunity to have monitoring and reenter educational programs. | (5) How is random drug and alcohol testing viewed within the organization? |

| (6) Hospitals and nursing schools that support monitoring and reentry are in line with the objectives of the US Government document Healthy People 2020. | (6) How are nurse executives made aware of individual nurses in recovery programs or under monitoring contracts? |

| (7) Hospital administrators are bound to follow ANA’s Code of Ethics for nurses, which support helping colleagues to recover from SUDs and return to work. | (7) Are substance use problems and access to assistance discussed openly in orientation with new staff? |

| (8) Nurses who are unwilling or unable to be rehabilitated should be terminated and referred to the state board of nursing for license revocation. |

Discussion

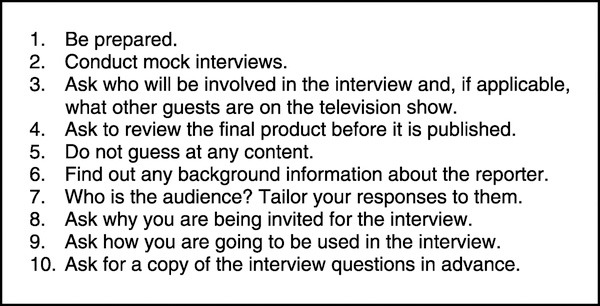

Nurses are responsible for more than half of the total hours (mean, 56%) worked in hospitals.36 Nursing administrators, in all likelihood, will be confronted with substance abuse issues given that between 2% and 20% of nurses may have an SUD during their careers.1–11 Many professional nursing organizations support reentry into the workplace by nurses recovering from substance abuse.2,32,34,37 Hospital and nursing administrators are key individuals who are responsible for employing safe qualified staff. Administrators are likely to be approached by the media and need evidence-based responses and current knowledge to respond appropriately.38 Ten preparatory suggestions for media interviews are presented for the nurse administrator or executive confronted with questions regarding SUD (Figure 3).38

Figure 3.

Preparation tips discussing SUDs with the media. Source: Sevel.38

Nurse executives should contact their state board of nursing and/or state ATD program to discuss the identified gaps in local and regional policies and how these gaps can be addressed in individual organizations. Nurse executives can contact the NCSBN (www.nscbn.org), NOAP (www.alternativeprograms.org), or ANA (www.nursingworld.org) for assistance in further addressing substance misuse and abuse among nursing professionals. The Texas Peer Assistance Program for Nurses has developed an educational program for nurse leaders, displayed in Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A57.39

Conclusion

The need for an international, comprehensive approach to the problem of substance abuse among nursing professionals is well documented, with an estimated 9,000 or more nurses in the United States alone reentering the workforce in recovery each year. Best practices for approaching this issue in healthcare institutions are available in the literature. It has been demonstrated that nurses and other healthcare professionals with SUDs can effectively be treated and return to safe practice, with no threat to public health or individual patients. Nursing organizations need rigorous and supportive mechanisms in place in order to support nurses recovering from SUDs. A crucial first step for leaders is to be well versed on key points related to addiction as well as gaps in current policies developed by professional organizations. These policies and guidelines support optimal outcomes for the employer, nursing leaders, nurses, and our profession in dealing with SUDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Ann Minnick, PhD, RN, FAAN, Vanderbilt University, and Gail Spake, MA, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, for their assistance in article refinement.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jonajournal.com).

Contributor Information

Dr Todd Monroe, School of Nursing, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

Mr Michael Vandoren, Texas Peer Assistance Program for Nurses, Austin.

Ms Linda Smith, Florida Intervention Project for Nurses, Jacksonville Beach.

Ms Joanne Cole, New Jersey Recovery and Monitoring Program, Trenton.

Dr Heidi Kenaga, Department of English, Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan.

References

- 1.Bell DM, McDonough JP, Ellison JS, Fitzhugh EC. Controlled drug misuse by certified registered nurse anesthetists. AANA J. 1999;67(2):133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Chemical Dependency Handbook Available at https://www.ncsbn.org/chem_dep_handbook_intro_ch1.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2011.

- 3.American Nurses Association. Addictions and Psychological Dysfunctions in Nursing. Kansas City: Author; 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore R, Mead L, Pearson T. Youthful precursors of alcohol abuse in physicians. Am J Med. 1990;88:332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krakowski A. Stress and the practice of medicine: physicians compared to lawyers. Psychosom Med. 1984;42:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes P, Brandenburg N, Dewitt B, et al. Prevalence of substance use among U.S. physicians. JAMA. 1992;267:2333–2339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trinkoff A, Storr C. Relationship of specialty and access to substance use among registered nurses: an exploratory analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36:215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldisseri M Impaired healthcare professional. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):S106–S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helzer J, Canino G, Yeh E, et al. Alcoholism—North America and Asia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel B, Fitzgerald F. A survey on the prevalence of alcoholism among the faculty and house staff of an academic teaching hospital. West J Alcohol. 1988;148:593–595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stocks G Abuse of propofol by anesthesia providers: the case for re-classification as a controlled substance. J Addict Nurs. 2011;22(1–2):57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson H, Compton M. Reentry of the addicted certified registered nurse anesthetist: a review of the literature. J Addict Nurs. 2009;20(4):177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alabama Board of Nursing. Annual Report. Available at http://www.abn.state.al.us/UltimateEditorInclude/UserFiles/docs/board/2009%20Annual%20Report.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2011.

- 14.US Bureau of the Census. US Population by State, 1790–2009. Available at www.census.gov. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 15.Clark C, Farnsworth J. Program for recovering nurses: an evaluation. Medsurg Nurs. 2006;15(4):223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monroe T, Pearson F, Kenaga H. Procedures for handling cases of substance abuse among nurses: a comparison of disciplinary and alternative programs. J Addict Nurs. 2008;19(3):156–161. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyoming State Board of Nursing. 2005 Annual Report. Available at https://nursing-online.state.wy.us/Resources/FY05%20-%20Annual%20Report%20Statistics.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2011.

- 18.Alaska Board of Nursing. Nursing workforce survey. Available at http://www.commerce.state.ak.us/occ/pnur19.htm. Accessed February 4, 2011.

- 19.Heise B The historical context of addiction in the nursing profession: 1850–1982. J Addict Nurs. 2003;14(3):117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. TIP 32: treatment of adolescents with substance abuse disorders. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=hssamhsatip&part=A56031. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 21.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment Projections to 2012. Available at www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2004/02/art5full.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 22.Peterson L In Sunday’s tribune: how nurse-addicts avoid arrest. Available at http://www2.tbo.com/content/2010/jul/30/sundays-tribune-how-nurses-avoid-arrest/life-health/. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 23.Office of National. Drug court. Available at http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/enforce/drugcourt.html. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 24.Darbro N Overview of issues related to coercion and monitoring in alternative diversion programs for nurses: a comparison to drug courts: Part 2. J Addict Nurs. 2009;2(1):24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roche B Substance Abuse Policies for Anesthesia. Winston-Salem, NC: All Anesthesia; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Best D, Rome A, Hanning K, et al. Research for recovery: a review of the drugs evidence base. Scottish Government Social Research. 2010. Scottish Government Social Research Web site. www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2010/08/18112230/0. Accessed May 10, 2011.

- 27.Monroe T Educational innovations. Addressing substance abuse among nursing students: development of a prototype alternative-to-dismissal policy. J Nurs Educ. 2009;48(5): 272–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Regulatory management of the chemically dependent nurse. Available at https://www.ncsbn.org/chem_dep_handbook_intro_ch1.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 29.National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Alternative programs. Available at https://www.ncsbn.org/chem_dep_handbook_ch9.pdf. April 16, 2011.

- 30.American Nurses Association. The center for ethics and human rights. The code of ethics for nurses. Available at http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/EthicsStandards/CodeofEthicsforNurses.aspx. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 31.Monroe T, Kenaga H. Don’t ask don’t tell: substance abuse and addiction among nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(3–4):504–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Position statement: policy and guidelines for the prevention of management of substance abuse in the nursing education community. Available at http://www.aacn.nche.edu/publications/positions/subabuse.htm. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 33.International Nurses Society on Addictions. Peer assistance [position statement]. Paper presented at: International Nurses Society on Addictions Winter Conference, 1995; Kansas City, KS. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canadian Nurses Association. Problematic substance abuse by nurses. Available at http://www.cna-aiic.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/Problem_Substance_Abuse_FS_e.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 35.Nursing and Midwifery Health Program. NMHP. Victoria, Australia: Available at http://www.nmhp.org.au/NMHP/Welcome.html. Accessed May 7, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolton LB, Aydin CE, Donaldson N, Brown DS, Nelson MS, Harms D. Nurse staffing and patient perceptions of nursing care. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(11):607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Nurses Association. The professional response to the problem of addiction and psychiatric disorders in nursing. Available at http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ThePracticeofProfessionalNursing/workplace/ImpairedNurse/Response.aspx. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- 38.Sevel F Are you prepared to meet the media? J Nurs Adm. 1986;16(3):21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Texas Peer Assistance Program for Nurses Sobering Data. Austin, TX: TPAPN; 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.