Abstract

Objective

The association between depression and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) remains debated. This study aimed to investigate the risk of BPPV in patients with depressive disorders.

Design

Longitudinal nationwide cohort study.

Setting

National health insurance research database in Taiwan.

Participants

We enrolled 10 297 patients diagnosed with depressive disorders between 2000 and 2009 and compared them to 41 188 selected control patients who had never been diagnosed with depressive disorders (at a 1:4 ratio matched by age, sex and index date) in relation to the risk of developing BPPV.

Methods

The follow-up period was defined as the time from the initial diagnosis of depressive disorders to the date of BPPV, censoring or 31 December 2009. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was used to investigate the risk of BPPV by sex, age and comorbidities, with HRs and 95% CIs.

Results

During the 9-year follow-up period, 44 (0.59 per 1000 person-years) patients with depressive disorders and 99 (0.33 per 1000 person-years) control patients were diagnosed with BPPV. The incidence rate ratio of BPPV among both cohorts calculating from events of BPPV per 1000 person-years of observation time was 1.79 (95% CI 1.23 to 2.58, p=0.002). Following adjustments for age, sex and comorbidities, patients with depressive disorders were 1.55 times more likely to develop BPPV (95% CI 1.08 to 2.23, p=0.019) as compared with control patients. In addition, hyperthyroidism (HR=3.75, 95% CI 1.67–8.42, p=0.001) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (HR=3.47, 95% CI 1.07 to 11.22, p=0.038) were potential risk factors for developing BPPV in patients with depressive disorders.

Conclusions

Patients with depressive disorders may have an increased risk of developing BPPV, especially those who have hyperthyroidism and SLE.

Keywords: depressive disorders, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, hyperthyroidism, systemic lupus erythematosus, risk factor, cohort study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The incidence of benign peripheral persistent vertigo (BPPV) among depressive disorders patient remains unclear. These longitudinal population-based data were conducted to assess the risk of BPPV in patients with depressive disorders.

The NHI research database (NHIRD) lacks detailed clinical data regarding severity and outcomes of BPPV.

Results from our study may underestimate the current condition since only patients seeking medical service would be identified in the Registry of NHIRD.

Introduction

Depressive disorders are common mood disorders occurring in all populations and the Global Burden of Disease 2017 had referred depressive disorders as a leading cause of health burden across the globe.1 Patients with depressive disorders have been reported with an increased risk of mortality and propose the classification of depressive disorders as life-threatening.2 3 Furthermore, people with depressive disorders have been reported with many somatic symptoms and result in increased need for clinical services, associated economic costs4 5 and considerable loss in quality of life.6

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) have been reported with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%, is the most common type of peripheral vertigo. Which is characterised by brief spinning sensations, usually induced by a sudden change in head position with respect to gravity, with attacks generally lasting <1 min. The fundamental pathophysiology of BPPV is dislodged calcium carbonate crystals in the utricle of the inner ear entering the semicircular canals.7 Old age8 and several comorbidities, such as hypertension,9 diabetes mellitus,9 hypercholesterolemia,10 pre-existing cardiovascular, thyroid and autoimmune10 disease, have been regarded as risk factors of BPPV. Patients who suffered from BPPV-related symptoms and following economic burden have also been reported.11

Psychiatric disorders or emotional stress are frequently observed in patients suffering from vertigo.12 13 The results of most studies have been reported the higher rate of coexistence of depression and vestibular disorders,14–16 which may lead to a vicious circle and a serious influence on the quality of life.17 Peripheral vertigo may play an essential role in the pathophysiology of development of subsequent depressive disorder. However, most of these studies report contradictory or conflicting results. Furthermore, when specified to explore the association between depression and BPPV, only a relatively small-scaled case–control study indicates that life stressors and related depressive disorder may be seen as a trigger of vestibular dysfunction, that is, a potential precursor of BPPV.18

Therefore, considering the debates on the association between the depression and BPPV and no large-scaled study have tried to investigate the issue, we designed a nationwide retrospective cohort study to explore the association between depressive disorder and the subsequent BPPV development. In addition, independent risk factors for developing BPPV among patients with depressive disorders were also investigated.

Materials and methods

Data sources

Nearly 99% of Taiwan’s population utilises healthcare services as a consequence of the National Health Insurance (NHI) Program Bold Legislative Act enacted in 1995.19 The programme offers comprehensive medical care coverage regarding outpatient, inpatient, emergency visits and Chinese medicine to all residents of Taiwan. The NHI research database (NHIRD) contains comprehensive information with regard to clinical practice, including prescription details and diagnostic codes in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) format. The NHIRD is managed by the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) and privacy is maintained according to directives from the Bureau of the NHI.20 The data source for our study was obtained from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 (LHID2000), a dataset of the NHIRD. The LHID2000, which contains all original claims data for 1 000 000 subjects, is a representative database randomly selected from the 2000 Registry of Beneficiaries under the NHI programme. Which also maintains the registration data of everyone who was a beneficiary of the NHI programme during the period of 1996–2000. Moreover, the NHRI affirms that there are no statistical differences in the distributions of age, sex or healthcare costs between the data in the LHID2000 and that of the NHIRD.20

Availability of data and materials section

The NHIRD is addressed in publicity by the NHRI and the use of NHIRD is only for research purposes. All applicants must obey the Computer-Processed Personal Data Protection Law and relevant regulations of the Bureau of NHI and NHRI. Moreover, applicants and their supervisor were asking for signing agreements on application submission. All applications are required to transmit data for review and approval and send an e-mail to the NHRI at nhird@nhri.org.tw or call at +886–037–246166 ext. 33 603 for immediate service. Office Hour: Monday–Friday 08:00–17:30 (UTC+8).

The NHIRD from the Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC), Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) (http://www.mohw.gov.tw/cht/DOS/) is now available for the researchers in Taiwan. The data are basically from the NHIRD. Researchers in Taiwan who interested in the data can apply to the MOHW. In the last sentence of the paragraph on the website, which said, ‘Kindly visit MOHW and NHIA on-site services for NHIRD’. The database was delivered to a higher-level government administration, called the ‘Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC)’ for more prompt health-related data linkage, broader application and better security management. Interested researchers could still apply to the HWDC, Department of Statistics, MOHW for NHI Data at present. HWDC, MOHW website (Chinese only currently http://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/np-2497-113.html). 21

Study design and subjects

We utilised data from the LHID2000 and conducted a retrospective cohort study using a dataset collected between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2004. We enrolled patients ≥20 years and received at least twice diagnosis of depressive disorders by psychiatrists with ICD-9-CM depressive disorders diagnosis codes of 296.2X-296.3X, 300.4 and 311.X. We defined the date of enrolling an adult patient with depressive disorders as case cohort between 2000 and 2004 as enrolment date. We excluded both in depressive disorders and control groups who were previously diagnosed with BPPV by ICD-9-CM code and A-code at the same time (ICD-9-CM code 386.11 and A-code: A249) to exclude patients who were diagnosed with BPPV before enrollment date.

The A-code, a much briefer version of the ICD-9-CM codes, is another disease classification system launched for fulfilling medical claims, was mainly used for ambulatory care before 2000 in Taiwan. The A-code had switched to the ICD-9-CM codes by NHI programme since 2000 to perpetuate consistency between different claims records and to truly reflect the distribution of various diseases. Consequently, we used these two medical code systems at the same time to reduce the discrepancies during the conversion time of A-code and ICD-9-CM codes. Which included acute myringitis, chronic myringitis, perforation of tympanic membrane, traumatic perforation of tympanic membrane, cholesteatoma of the middle ear, Meniere’s disease, peripheral vertigo, vestibulopathy, vertigo of central origin, labyrinthitis, presbycusis, sudden hearing loss, tinnitus and otalgia.

The cohort including patients with and without depressive disorders was observed until the development of BPPV, death, withdrawal from the NHI system or 31 December 2009. The primary clinical outcome in our study was only BPPV diagnosed by neurologists or otorhinolaryngologists. For each patient with depressive disorders included in the final cohort, four age- and sex-matched control patients without depressive disorders were randomly selected on the same enrolment date from the LHID2000. Finally, we identified 10 297 patients with depressive disorders. To assemble a comparison cohort, we randomly selected 41 188 enrollees without a history of depressive disorders.

Statistical analyses

The incidence of newly diagnosed BPPV in patients with depressive disorders and controls during the observational period was calculated and stratified by sex and age (≥65 years or <65 years). Comparisons between continuous variables were conducted with the independent t-test. Chi-squared analysis was used to examine the association of two categorical characteristics between the depressive disorders and control cohort. A Cox proportional hazard model was used to evaluate confounding variables and whether depressive disorders increase the risk of developing BPPV. The confounding variables were age, sex and common comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, cerebrovascular disease and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Another Cox proportional-hazards regression model was performed again to identify variables that predicted BPPV in the patients with depressive disorders. The variables that demonstrated a moderately significant statistical relationship with BPPV in the univariate analysis (p<0.1) were entered through forward selection in a multivariate analysis.

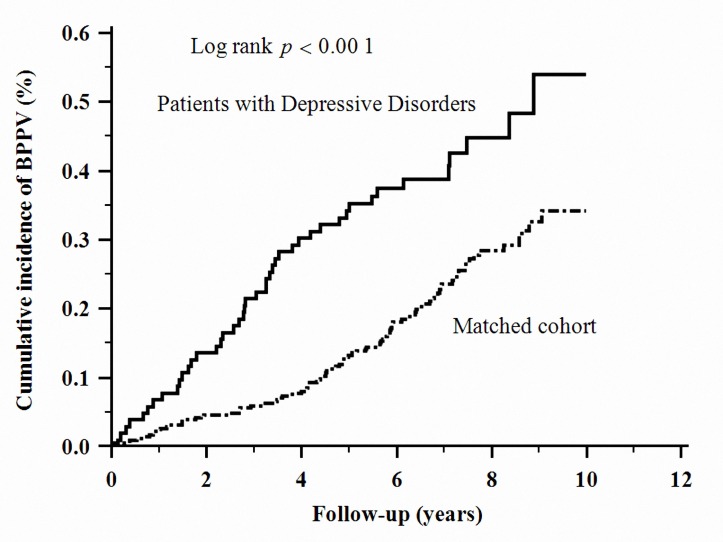

The cumulative incidences of BPPV were compared between depressive disorder and control cohorts using Kaplan-Meier curves. Stratified log rank test was applied to determine the differences in the risk for BPPV in the cohort.

Patient and public involvement

The data source used for this study was the claims data of Taiwan’s NHIRD. We did not involve patients/service users in the research question, the outcome measures, or the design or implementation of the study. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants.

Results

Participant selection

We analysed 10 297 patients with depressive disorders and 41 188 control patients. The majority of patients in the cohort were female (61%). The median age was 39 years (IQR=30–51 years), and the median follow-up period was 7.19 years (IQR=5.96–8.48 years) for patients with depressive disorders and 7.22 years (IQR=6.00–8.51 years) for control patients (p=0.002). Table 1 includes comparisons of demographic, clinical variables and socioeconomic data between the control and depressive cohorts. In the depressive disorders group, the most common comorbidities were hypertension (2124 patients, 20.6%), diabetes mellitus (1236 patients, 12.0%) and dyslipidemia (1541 patients, 14.5%). As compared with the controls, depressive disorders patients had significantly more physical comorbidities. Besides, depressive disorders patients had a significantly higher prevalence in low-income populations (50.4% vs 44.4%, p<0.001) and in urban areas (64.1% vs 60.9%, p<0.001) as compared with non-depressive disorders patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without depressive disorders

| Demographic data | Patients with depressive disorders n=10 297 | Patients without depressive disorders n=41 188 | P value | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years)* | 39 (30–51) | 39 (30–51) | |||

| ≥65 | 1036 | 10.1 | 4143 | 10.1 | 0.999 |

| <65 | 9261 | 89.9 | 37 045 | 89.9 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 4012 | 39.0 | 16 048 | 39.0 | 1.000 |

| Female | 6285 | 61.0 | 25 140 | 61.0 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 2124 | 20.6 | 5444 | 13.2 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1236 | 12.0 | 3112 | 7.5 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1541 | 14.5 | 3829 | 9.3 | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 87 | 0.8 | 235 | 0.6 | 0.002 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 511 | 5.0 | 727 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 116 | 1.1 | 193 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 573 | 5.6 | 1106 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 216 | 2.1 | 437 | 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Degree of urbanisation | |||||

| Urban | 6599 | 64.1 | 25 196 | 60.9 | <0.001 |

| Suburban | 2680 | 26.0 | 12 172 | 29.4 | |

| Rural | 817 | 7.9 | 3205 | 7.8 | |

| Income group | |||||

| Low income | 5189 | 50.4 | 18 340 | 44.4 | <0.001 |

| Medium income | 3819 | 37.1 | 16 426 | 39.7 | |

| High income | 1289 | 12.5 | 6422 | 15.5 | |

| Follow-up years* | 7.19 (5.96–8.48) | 7.22 (6.00–8.51) | 0.002 | ||

*Median (IQR).

Person-time incidence rate of BPPV

During the follow-up period, 44 patients (0.59 per 1000 person-years) were diagnosed with BPPV in the depressive disorders group, and 99 patients (0.33 per 1000 person-years) were diagnosed with BPPV in the control group. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) of BPPV between depressive disorders and control patients was 1.79 (95% CI 1.23 to 2.58, p=0.002). The IRR of BPPV remained higher in the depressive disorders than in the control patients among both sexes. When stratified with age, only patient younger than 65 years old have higher IRR of BPPV. The results are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Person-time incidence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) in patients with and without depressive disorders

| Patients with depressive disorders | Patients without depressive disorders | Rate ratio (95% CI) | P value | |||

| No of BPPV | Per 1000 person-years | No of BPPV | Per 1000 person-years | |||

| Total | 44 | 0.59 | 99 | 0.33 | 1.79 (1.23 to 2.58) | 0.002 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≥65 | 7 | 0.98 | 15 | 0.51 | 1.90 (0.66 to 4.95) | 0.153 |

| <65 | 37 | 0.55 | 84 | 0.31 | 1.77 (1.17 to 2.64) | 0.003 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 16 | 0.56 | 31 | 0.27 | 2.08 (1.16 to 3.76) | 0.023 |

| Female | 28 | 0.62 | 68 | 0.37 | 1.66 (1.07 to 2.56) | 0.030 |

The cumulative incidence of BPPV in the patients with depressive disorders was significantly higher than that in the control cohort (log-rank test, p<0.001, figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in depressive disorders and comparison cohort. The cumulative incidence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in patients with depressive disorders was significantly higher than that in the comparison cohort.

Risks of newly diagnosed BPPV among the patients with and without depressive disorders

After adjusting for age, sex, common comorbidities and SLE, there was a higher risk of developing BPPV in patients with depressive disorders than in the control patients (HR=1.55, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.23, p=0.019). Results are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Analyses of risk factors for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in patients with and without depressive disorders

| Predictive variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Depressive disorders | 1.79 (1.26 to 2.56) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.08 to 2.23) | 0.019 |

| Age, years (≥65 = 1, <65 = 0) | 1.69 (1.07 t o 2.66) | 0.002 | ||

| Sex (female=1, male=0) | 1.29 (0.91 to 1.82) | 0.158 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 1.91 (1.30 to 2.81) | <0.001 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.36 (0.80 to 2.32) | 0.261 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 2.15 (1.42 to 3.27) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.15 to 2.75) | 0.010 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5.06 (1.87 to 13.67) | <0.001 | 3.29 (1.18 to 9.17) | 0.023 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 2.90 (1.48 to 5.70) | 0.002 | 2.46 (1.24 to 4.87) | 0.010 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.26 (0.18 to 9.02) | 0.817 | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3.23 (1.83 to 5.71) | <0.001 | 2.24 (1.21 to 4.15) | 0.010 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2.44 (0.90 to 6.60) | 0.079 | ||

| Degree of urbanisation | ||||

| Urban | Reference | |||

| Suburban | 1.10 (0.77 to 1.57) | 0.606 | ||

| Rural | 4.38 (0.18 to 1.08) | 0.072 | ||

| Income group | ||||

| Low income | Reference | |||

| Medium income | 0.98 (0.69 to 1.38) | 0.886 | ||

| High income | 0.65 (0.37 to 1.14) | 0.133 | ||

Risk factors for BPPV in patients with depressive disorders

As shown in table 4, we predicted the development of BPPV in the depressive disorder cohorts by applying univariate analysis. Univariate analysis demonstrated that dyslipidemia (HR=1.97, 95% CI 0.99 to 3.89, p=0.053), hyperthyroidism (HR=3.74, 95% CI 1.67 to 8.38, p<0.001), cerebrovascular disease (HR=2.31, 95% CI 0.91 to 5.85, p=0.079) and SLE (HR=3.58, 95% CI 1.11 to 11.56, p=0.033) were possible prognostic factors. Multivariate analysis indicated that hyperthyroidism (HR=3.75, 95% CI 1.67 to 8.42, p=0.001) and SLE (HR=3.47, 95% CI 1.07 to 11.22, p=0.038) were an independent risk factor for patients with depressive disorders.

Table 4.

Analyses of risk factors for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in patients with depressive disorders

| Predictive variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, years (≥65 = 1, <65 = 0) | 1.75 (0.78 to 3.93) | 0.174 | ||

| Sex (female=1, male=0) | 1.10 (0.60 to 2.04) | 0.752 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.88 (0.41 to 1.90) | 0.747 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.98 (0.39 to 2.49) | 0.969 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 1.97 (0.99 to 3.89) | 0.053 | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 2.93 (0.40 to 21.26) | 0.288 | ||

| Hyperthyroidism | 3.74 (1.67 to 8.38) | <0.001 | 3.75 (1.67 to 8.42) | 0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2.17 (0.30 to 15.75) | 0.444 | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.31 (0.91 to 5.85) | 0.079 | ||

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 3.58 (1.11 to 11.56) | 0.033 | 3.47 (1.07 to 11.22) | 0.038 |

| Degree of urbanisation | ||||

| Urban | Reference | |||

| Suburban | 1.53 (0.82 to 2.86) | 0.180 | ||

| Rural | 0.31 (0.04 to 2.28) | 0.249 | ||

| Income group | ||||

| Low income | Reference | |||

| Medium income | 1.33 (0.71 to 2.52) | 0.377 | ||

| High income | 1.24 (0.50 to 3.11) | 0.644 | ||

Discussion

The two major findings in our study are as the following. First, patients with depressive disorders presented a 1.55-fold greater risk of subsequently developing BPPV than did the general population by utilising a nationwide population-based cohort study. Second, only hyperthyroidism (HR=3.75, 95% CI 1.67–8.42, p=0.001) and SLE (HR=3.47, 95% CI 1.07–11.22, p=0.038) were independent risk factors to develop BPPV among patients with depressive disorders.

The strength of this study is using a nationwide population-based data to evaluate BPPV risk in patients with depressive disorders. Advantages of using our NHIRD in medical research have been previously described,22 which include enormous sample size, lack of selection and participation bias and long-term comprehensive follow-up. Whereas the results of most studies demonstrated the correlation between BPPV and following depressive disorders,23 24 to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study implying that patients with depressive disorders have higher risk of developing BPPV.

Though depressive disorder have been reported to produce somatic symptoms including symptoms like BPPV,25 one research indicated that patients with unrecognised BPPV were more likely to have depressive disorder.26 Another study pointed out that depressive disorders may be an early presentation of neural circuitry alterations involving connections between the vestibular system and anatomical area such as hippocampus, amygdala and infralimbic cortex.27 One Asian literature showed that depression symptoms may adversely affect BPPV recurrence.28 Though there was no strong evidence consistent with our findings, evidence mentioned above may indirectly prove our hypothesis.

The pathophysiologyof depressive disorders and subsequent BPPV is unknown. There are several proposed mechanisms to explain this association. First, dysregulation of oxidative and inflammatory processes in depressive disorders may result in subsequent BPPV development. Numerous studies have demonstrated patients with depressive disorders have excessive oxidative stress and elevation in inflammatory responses.29–32 Evidence supports a role for oxidative stress in otolith dysfunction leading to an increased risk of developing canalolithiasis, an essential step in the pathogenesis of BPPV.33–36 Additional studies conclude depressive disorders associated with oxidative stress result in vestibular hair cells and neuronal damage in the inner ear,37 which contributes to vestibular dysfunction and subsequent BPPV development.38 39Second, depressive disorders may induce abnormalities of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis, which may hinder the inner ear blood flow and influence inner ear fluid balance. These abnormalities lead to dysfunction of the otoconial homeostasis,18 40 an established risk factor for development of BPPV.41 Therefore, alterations to the neuroendocrine system may be the link between depressive disorders and the development of BPPV. Third, BPPV development in depressive disorders may be induced by serotonin dysfunction. The vestibular nucleus complex is composed of a large number of serotonin receptors, and lack of serotonin may result in a substantial impact on the electrophysiological activity of neurons, and dysfunction of the vestibular nucleus complex.42 Previous studies have hypothesised a role for vestibular nucleus damage in the pathogenesis of BPPV development.39 43Fourth, the dysregulation of the immune system, frequently observed in depressive disorders,44 45 has proved to be an essential part of BPPV pathogenesis. Stone and Francis46 suggest BPPV could develop by immune system’s direct attack or indirect attack, resulting in debris within the inner ears. This explanation could be confirmed by studies demonstrated the association of several autoimmune diseases, such as systemic sclerosis,47 SLE, ulcerative colitis, Sjogren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis46 in the development of BPPV. Consistent with the studies mentioned above, we found that SLE is a risk factor for BPPV among depressive cohort (table 4) but not for all the participants (table 3) in this study. Based on the previous studies, several results of the studies could provide the evidence revealing that the comorbidities with depressive disorder and SLE would result in the exacerbation of the SLE disease activities, no matter the possible explanations were psychological or behavioural issues such as lack of insight and poor anti-inflammatory drug compliance.48–50 The evidence indicated that the severity of inflammatory processes on the differences between the patients with depressive disorder alone and the depressive patients comorbid with SLE.

We conclude patients with depressive disorders are more likely to develop BPPV if they are afflicted with hyperthyroidism. Mechanical movements of thyroid autoantibodies in the inner ear fluid or the development of autoimmune microangiitis in the labyrinth can result in BPPV in the presence of hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism.51 Other studies support a role for thyroid hormone fluctuations52 and circulating anti-thyroid autoantibodies53 related to vestibular dysfunction in subsequent BPPV development. Therefore, dysregulation of the immune system may play a vital role between hyperthyroidism and BPPV as documented by our study. In addition, we inferred that hyperthyroidism altered calcium metabolism and otoconia dissolve impairment may play a role in developing BPPV among depressive disorders patients. Up to 20% of thyrotoxic patients have mild hypercalcemia because of thyroid hormone-mediated bone resorption.54 Otoconia, mainly synthesised from calcium,55 which breaks free and moves into the semicircular canals was the fundamental pathophysiology of BPPV.8 Therefore, hyperthyroidism with increased calcium might lead to increased concentration of free calcium in the endolymph and reduce its capacity to dissolve the dislodged otoconia,56 this mechanism involved in the pathophysiology of BPPV.

Though there is no direct evidence support the pathophysiology of BPPV occurred in patients coexistence with depressive disorder and hyperthyroidism. Patients suffered from symptoms like palpitation, insomnia, anxiety and irritability, which symptoms usually belonging to hyperthyroidism and was difficult to discriminate from the psychiatric disorder, have been proposed easily seeking medical treatment.57 Therefore, we proposed that hyperthyroidism-related panic-like symptoms may increase the chance of diagnosis of BPPV through greater medical contact.

There are several limitations in this study. The first limitation relates to the lack of detailed information regarding tobacco use, alcohol consumption, head position in bed and family history of BPPV in patient data collected from the NHIRD, factors which may influence risk of BPPV development.58–60 Thus, we were unable to control for these potentially confounding factors. Second, the NHIRD is an administrative database, which lacks detailed clinical data regarding severity and outcomes of BPPV patients, which interferes with analysis of BPPV prognoses in the cohort. Third, in the claims-based study design, only patients seeking medical service would be identified in the Registry of NHIRD and these identification issues may either overestimate or underestimate the results. Fourth, our study did not provide any information about medications administered for BPPV.

Since profound health burden and extensive healthcare utilisation may be influential with BPPV development.61 62 Our findings and findings in other literature raised our attention to unrecognised BPPV and inappropriate treatment among patients with depressive disorders may lead to disabling and related poor quality of life.

Conclusions

In the population-based retrospective study, we found that patients with depressive disorders have statistically higher risk of developing BPPV. Furthermore, hyperthyroidism and SLE were identified an independent risk factor to develop BPPV for patients with depressive disorders. Future studies are required to clarify the underlying biological mechanisms of these associations. Clinicians are encouraged to provide appropriate medical care for those who diagnosed with BPPV and pre-existing depressive disorder. Monitoring and management depressive symptoms for the high-risk patients are also warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Research Center of Medical informatics at Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital for the technical assistance. The study is based on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the BNHI, Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan and managed by NHRI, Taiwan. We express our particular gratitude to the government organisation BNHI and the non-profit foundation NHRI.

Footnotes

Contributors: C-LH and L-YH wrote the manuscript. C-CS and TL helped with study design and data collection. C-CS, S-JT and Y-MH contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grant NSC 101-2314-B-075-040 from the National Science Council, Taiwan, and grant V103C-048 from the Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

Disclaimer: The funding sources had no role in the study design or conduct, or in the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kaohsiung VeteransGeneral Hospital (No VGHKS14-CT7-07).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC), Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) (http://www.mohw.gov.tw/cht/DOS/) for the researchers in Taiwan. Data are available at http://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/np-2497-113.html (Chinese only currently) with the permission of HWDC, Department of Statistics, MOHW.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Organization WH. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cuijpers P, Smit F. Excess mortality in depression: a meta-analysis of community studies. J Affect Disord 2002;72:227–36. 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00413-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kozela M, Bobak M, Besala A, et al. The association of depressive symptoms with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in Central and Eastern Europe: prospective results of the HAPIEE study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:1839–47. 10.1177/2047487316649493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berto P, D’Ilario D, Ruffo P, et al. Depression: cost-of-illness studies in the international literature, a review. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2000;3:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greenberg PE, Birnbaum HG. The economic burden of depression in the US: societal and patient perspectives. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2005;6:369–76. 10.1517/14656566.6.3.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jia H, Zack MM, Thompson WW, et al. Impact of depression on quality-adjusted life expectancy (QALE) directly as well as indirectly through suicide. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:939–49. 10.1007/s00127-015-1019-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fife TD, von Brevern M. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the acute care setting. Neurol Clin 2015;33:601–17. 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim JS, Zee DS. Clinical practice. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1138–47. 10.1056/NEJMcp1309481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Stefano A, Dispenza F, Suarez H, et al. A multicenter observational study on the role of comorbidities in the recurrent episodes of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Auris Nasus Larynx 2014;41:31–6. 10.1016/j.anl.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Messina A, Casani AP, Manfrin M, et al. Italian survey on benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2017;37:328–35. 10.14639/0392-100X-1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benecke H, Agus S, Kuessner D, et al. The Burden and Impact of Vertigo: findings from the REVERT Patient Registry. Front Neurol 2013;4:136 10.3389/fneur.2013.00136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ketola S, Havia M, Appelberg B, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in vertiginous patients. Nord J Psychiatry 2015;69:287–91. 10.3109/08039488.2014.972976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Söderman AC, Möller J, Bagger-Sjöbäck D, et al. Stress as a trigger of attacks in Menière’s disease. A case-crossover study. Laryngoscope 2004;114:1843–8. 10.1097/00005537-200410000-00031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Monzani D, Casolari L, Guidetti G, et al. Psychological distress and disability in patients with vertigo. J Psychosom Res 2001;50:319–23. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00208-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen ZJ, Chang CH, Hu LY, et al. Increased risk of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in patients with anxiety disorders: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:238 10.1186/s12888-016-0950-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yuan Q, Yu L, Shi D, et al. Anxiety and depression among patients with different types of vestibular peripheral vertigo. Medicine 2015;94:e453 10.1097/MD.0000000000000453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Best C, Eckhardt-Henn A, Tschan R, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in different vestibular vertigo syndromes. Results of a prospective longitudinal study over one year. J Neurol 2009;256:58–65. 10.1007/s00415-009-0038-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Monzani D, Genovese E, Rovatti V, et al. Life events and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a case-controlled study. Acta Otolaryngol 2006;126:987–92. 10.1080/00016480500546383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheng TM. Taiwan’s new national health insurance program: genesis and experience so far. Health Aff 2003;22:61–76. 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. NHRI CfBRo. Database. NHIR National Health Research Institutes. 2018. http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/2018 (accsessed 2018).

- 21. Health and Clinical Research Data Center TMU. Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC) -Health and Welfare Database Taiwan. 2018. http://hcrdc.tmu.edu.tw/en/News/Health-and-Welfare-Data-Science-Center-HWDC-Health-and-Welfare-Database-88879687 (accessed 22 Dec 2018).

- 22. Hsing AW, Ioannidis JP. Nationwide Population Science: Lessons From the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1527–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hagr A. Comorbid psychiatric conditions of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Int J Health Sci 2009;3:23–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eckhardt-Henn A, Best C, Bense S, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in different organic vertigo syndromes. J Neurol 2008;255:420–8. 10.1007/s00415-008-0697-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferrari S, Monzani D, Baraldi S, et al. Vertigo "in the pink": the impact of female gender on psychiatric-psychosomatic comorbidity in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo patients. Psychosomatics 2014;55:280–8. 10.1016/j.psym.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, van Leeuwen RB, Bruintjes TD, et al. Prevalence of unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in older patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015;272:1521–4. 10.1007/s00405-014-3409-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gurvich C, Maller JJ, Lithgow B, et al. Vestibular insights into cognition and psychiatry. Brain Res 2013;1537:244–59. 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.08.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wei W, Sayyid ZN, Ma X, et al. Presence of anxiety and depression symptoms affects the first time treatment efficacy and recurrence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Front Neurol 2018;9:178 10.3389/fneur.2018.00178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sarandol A, Sarandol E, Eker SS, et al. Major depressive disorder is accompanied with oxidative stress: short-term antidepressant treatment does not alter oxidative-antioxidative systems. Hum Psychopharmacol 2007;22:67–73. 10.1002/hup.829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cudney LE, Sassi RB, Behr GA, et al. Alterations in circadian rhythms are associated with increased lipid peroxidation in females with bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014;17:715–22. 10.1017/S1461145713001740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Szuster-Ciesielska A, Słotwińska M, Stachura A, et al. Accelerated apoptosis of blood leukocytes and oxidative stress in blood of patients with major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2008;32:686–94. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Widner B, Fuchs D, Leblhuber F, et al. Does disturbed homocysteine and folate metabolism in depression result from enhanced oxidative stress? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;70:419 10.1136/jnnp.70.3.419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsai KL, Cheng YY, Leu HB, et al. Investigating the role of Sirt1-modulated oxidative stress in relation to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36:2607–16. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kaya H, Gokdemir MT, Sogut O, et al. Evaluation of oxidative status and trace elements in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. HealthMed 2013;7:72–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goto F, Hayashi K, Kunihiro T, et al. The possible contribution of angiitis to the onset of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Int Tinnitus J 2010;16:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fujita N, Yamanaka T, Okamoto H, et al. [Horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo–its affected side and horizontal semicircular canal function]. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 2005;108:202–6. 10.3950/jibiinkoka.108.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iwasaki S, Yamasoba T. Dizziness and imbalance in the elderly: age-related decline in the vestibular system. Aging Dis 2015;6:38–47. 10.14336/AD.2014.0128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu Z, Zhao P, Yang X, et al. [The hearing and vestibular evoked myogenic potentials test in patients with primary benign paroxysmal positional vertigo]. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2015;29:20–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Frohman EM, Kramer PD, Dewey RB, et al. Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo in multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, pathophysiology and therapeutic techniques. Mult Scler 2003;9:250–5. 10.1191/1352458503ms901oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Horner KC, Cazals Y. Stress in hearing and balance in Meniere’s disease. Noise Health 2003;5:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fuchs E, Flügge G. Chronic social stress: effects on limbic brain structures. Physiol Behav 2003;79:417–27. 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00161-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith PF, Darlington CL. A possible explanation for dizziness following SSRI discontinuation. Acta Otolaryngol 2010;130:981–3. 10.3109/00016481003602082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fetter M. Vestibulo-ocular reflex. Dev Ophthalmol 2007;40:35–51. 10.1159/000100348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chiriţă AL, Gheorman V, Bondari D, et al. Current understanding of the neurobiology of major depressive disorder. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2015;56:651–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hodes GE, Kana V, Menard C, et al. Neuroimmune mechanisms of depression. Nat Neurosci 2015;18:1386–93. 10.1038/nn.4113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stone JH, Francis HW. Immune-mediated inner ear disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2000;12:32–40. 10.1097/00002281-200001000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thombs BD, Jewett LR, Kwakkenbos L, et al. Major depression diagnoses among patients with systemic sclerosis: baseline and one-month followup. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:411–6. 10.1002/acr.22447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alsowaida N, Alrasheed M, Mayet A, et al. Medication adherence, depression and disease activity among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2018;27:327–32. 10.1177/0961203317725585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Heiman E, Lim SS, Bao G, et al. Depressive symptoms are associated with low treatment adherence in African American Individuals With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol 2018;24:368–74. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Figueiredo-Braga M, Cornaby C, Cortez A, et al. Depression and anxiety in systemic lupus erythematosus: the crosstalk between immunological, clinical, and psychosocial factors. Medicine 2018;97:e11376 10.1097/MD.0000000000011376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Papi G, Guidetti G, Corsello SM, et al. The association between benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and autoimmune chronic thyroiditis is not related to thyroid status. Thyroid 2010;20:237–8. 10.1089/thy.2009.0319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lautermann J, ten Cate WJ. Postnatal expression of the alpha-thyroid hormone receptor in the rat cochlea. Hear Res 1997;107:23–8. 10.1016/S0378-5955(97)00014-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chiarella G, Tognini S, Nacci A, et al. Vestibular disorders in euthyroid patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: role of thyroid autoimmunity. Clin Endocrinol 2014;81:600–5. 10.1111/cen.12471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Iqbal AA, Burgess EH, Gallina DL, et al. Hypercalcemia in hyperthyroidism: patterns of serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels during management of thyrotoxicosis. Endocr Pract 2003;9:517–21. 10.4158/EP.9.6.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lundberg YW, Xu Y, Thiessen KD, et al. Mechanisms of otoconia and otolith development. Dev Dyn 2015;244:239–53. 10.1002/dvdy.24195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vibert D, Kompis M, Häusler R. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in older women may be related to osteoporosis and osteopenia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2003;112:885–9. 10.1177/000348940311201010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Demet MM, Ozmen B, Deveci A, et al. Depression and anxiety in hyperthyroidism. Arch Med Res 2002;33:552–6. 10.1016/S0188-4409(02)00410-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sunami K, Tochino R, Tokuhara Y, et al. Effects of cigarettes and alcohol consumption in benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol 2006;126:834–8. 10.1080/00016480500527474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lopez-Escámez JA, Gámiz MJ, Fiñana MG, et al. Position in bed is associated with left or right location in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior semicircular canal. Am J Otolaryngol 2002;23:263–6. 10.1053/ajot.2002.124199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gizzi M, Ayyagari S, Khattar V. The familial incidence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol 1998;118:774–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Grill E, Penger M, Kentala E. Health care utilization, prognosis and outcomes of vestibular disease in primary care settings: systematic review. J Neurol 2016;263(Suppl 1):36–44. 10.1007/s00415-015-7913-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mueller M, Strobl R, Jahn K, et al. Burden of disability attributable to vertigo and dizziness in the aged: results from the KORA-Age study. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:802–7. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The NHIRD is addressed in publicity by the NHRI and the use of NHIRD is only for research purposes. All applicants must obey the Computer-Processed Personal Data Protection Law and relevant regulations of the Bureau of NHI and NHRI. Moreover, applicants and their supervisor were asking for signing agreements on application submission. All applications are required to transmit data for review and approval and send an e-mail to the NHRI at nhird@nhri.org.tw or call at +886–037–246166 ext. 33 603 for immediate service. Office Hour: Monday–Friday 08:00–17:30 (UTC+8).

The NHIRD from the Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC), Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) (http://www.mohw.gov.tw/cht/DOS/) is now available for the researchers in Taiwan. The data are basically from the NHIRD. Researchers in Taiwan who interested in the data can apply to the MOHW. In the last sentence of the paragraph on the website, which said, ‘Kindly visit MOHW and NHIA on-site services for NHIRD’. The database was delivered to a higher-level government administration, called the ‘Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC)’ for more prompt health-related data linkage, broader application and better security management. Interested researchers could still apply to the HWDC, Department of Statistics, MOHW for NHI Data at present. HWDC, MOHW website (Chinese only currently http://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/np-2497-113.html). 21