Abstract

Introduction

Nipple fissure and nipple pain are common complaints among breastfeeding mothers. Studies found that mupirocin was effective in preventing and treating infections of damaged nipple and nipple pain. Acidic fibroblast growth factor (aFGF) plays an important role in wound healing. However, current evidence on the efficacy and safety of mupirocin plus aFGF for nipple fissure and nipple pain in breastfeeding women is inconclusive due to the lack of well-designed randomised controlled trials on this topic. The purpose of this study is to test the hypothesis that mupirocin plus aFGF is more effective than mupirocin alone for nipple fissure and nipple pain in breastfeeding women.

Methods and analysis

This study is a randomised, double-blind, single-centre, parallel-group clinical trial. A total of 120 breastfeeding women with nipple fissure and nipple pain will be randomly assigned to either mupirocin plus aFGF group or mupirocin plus placebo group according to a computer-generated random allocation sequence. The treatment period lasts 14 days. The primary outcome is nipple pain intensity measured by the Visual Analogue Scale on day 14 during the treatment period. Secondary outcome measures include time to complete nipple pain relief, changes in the Nipple Trauma Score, time to complete healing of nipple trauma, quality of life measured by the Maternal Postpartum Quality of Life (MAPP-QOL) Questionnaire, the frequency of breast feeding, the rate of breastfeeding discontinuation, weight change in infants and adverse events.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has gained approval from the Ethics Review Committee of Tianjin Central Hospital of Gynaecology Obstetrics on 22 January 2018 (approval no. 2018KY001). We plan to publish our research findings in a peer-reviewed academic journal and disseminate these findings in international conferences. This study has been registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR1800017248.

Keywords: nipple fissure, nipple pain, breastfeeding, mupirocin, acidic fibroblast growth factor

Strengths and limitations of this study:

This is the first randomised controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of mupirocin plus acidic fibroblast growth factor for nipple fissure and nipple pain in breastfeeding women.

The investigators, patients, pharmacist and outcome assessor are all blinded.

The generalisability of the results is limited as it is a single-centre trial.

No cost-effectiveness analysis will be performed.

Introduction

Exclusive breast feeding is recommended for the first 6 months after birth and then breast feeding in infants should be continued into the second year and beyond.1–3 Some researches have suggested that there are multiple benefits of breast feeding to both mother and baby. Breast feeding is associated with lower risks of gastrointestinal diseases and respiratory diseases in infants.4 It also brings long-term health benefits to mothers including reduced risks of developing breast cancer and type 2 diabetes.4–6

Nipple fissure and nipple pain are common complaints among breastfeeding mothers.7 8 Patients may experience either nipple fissure or nipple pain, or both.

A longitudinal study found that 17% of breastfeeding women experienced nipple fissure and 38% reported nipple pain at 1 month postpartum.9 A prospective cohort study showed that 58% of women reported nipple damage and 72% experienced nipple pain 1 week after giving birth.10 A review found that the incidence of nipple fissure ranged from 29% to 76%.11 Another review showed that the incidence of nipple pain varied between 34% and 96%.12 Some of the possible causes of nipple fissure or nipple pain include poor infant positioning, prolonged lactation, high frequency of feeding, engorgement of breast, lack of nipple exposure to light and air, and so on.8 13 14 The damaged nipple may lead to breast feeding cessation.15

Medical management of nipple fissure and nipple pain includes pharmacotherapy (oral or external use) against bacterial or fungal infections and non-pharmacological interventions such as glycerine, lanolin, peppermint oil and nipple protectors.8 12 16–18 Also, a study found that educating mothers on proper positioning and latching effectively prevented the incidence and recurrence of nipple fissure and nipple pain.12 A systematic review showed that it was inconclusive whether interventions for nipple trauma in breastfeeding mothers were effective.11 A 2014 Cochrane systematic review showed that there was insufficient evidence to recommend any intervention for the treatment of nipple pain.8

Damaged nipples are easily infected with bacteria, Candida or other microorganisms.17 19 20 A study found a close association between bacterial infections and nipple pain.19 A prospective study found that 54% of breastfeeding women were infected by Staphylococcus aureus.21 Mupirocin, a type of antibiotic, is used for skin infections caused by bacteria, such as S. aureus.19 22 A study suggests that mupirocin is effective against infection of damaged nipples.17 The mupirocin ointment is usually used sparingly, so the infant is unlikely to ingest a significant amount. Moreover, oral mupirocin is rapidly metabolised, thus lowering the risk of causing adverse effects in the nursing baby.17 A clinical trial showed that mupirocin was generally well tolerated in infants.23

The process of skin repair involved in the healing of nipple trauma is regulated by a variety of cell growth factors. A review indicated that fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) played an important role in wound healing.24 FGFs could promote wound healing through stimulating proliferation and differentiation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts and facilitating regeneration of granulation tissues.25 26 They have been widely used for skin repair following burns, ulcers, skin transplantation and other types of injuries.27

Both acidic FGF (aFGF) and basic FGF (bFGF) belong to the FGF family.28 As the acidification is commonly observed in the wounded skin area,29 aFGF is supposed to be more effective than bFGF for the healing of wounds. A randomised controlled trial showed that the time to complete healing (days) in the aFGF group was significantly shorter than in the bFGF group in patients with skin burns (mean difference=−2.10, 95% CI −2.61 to −1.59, p<0.001).30

To our knowledge, current clinical evidence on the efficacy and safety of mupirocin plus aFGF for nipple fissure and nipple pain in breastfeeding women is inconclusive due to a lack of rigorously designed randomised controlled trials on this topic.

The purpose of this study is to test the hypothesis that mupirocin plus aFGF is more effective than mupirocin plus placebo for nipple fissure and nipple pain in breastfeeding women.

Methods and analysis

This protocol was developed following the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials 2013 statement.31 The registration information is available at http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=29278.

Study design

This study is a randomised, double-blind, single-centre, parallel-group clinical trial.

Study setting

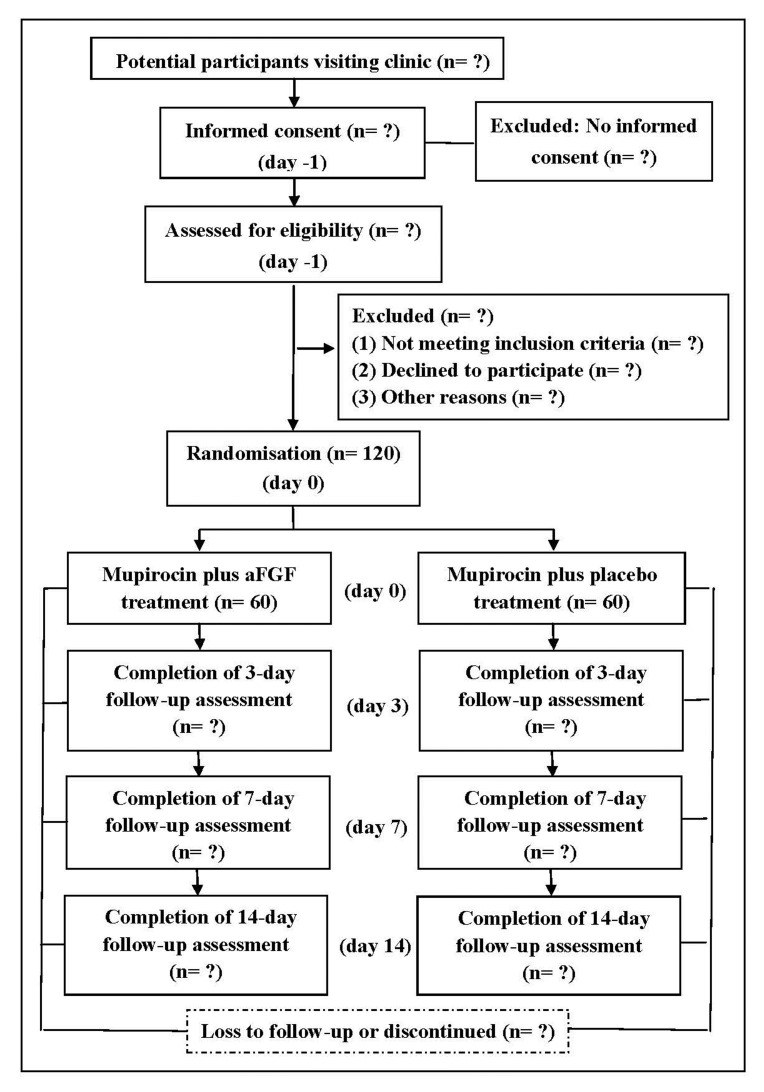

Study participants will be recruited from the inpatient and outpatient departments of the breast clinic at Tianjin Central Hospital of Gynaecology Obstetrics. There are more than 10 000 infants born per year in this hospital. More than 10 000 women attend this clinic. Patient recruitment will start in August 2018 and we plan to finish the study by December 2019. A schematic diagram is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of participants' enrolment, interventions, assessments and visits. aFGF, acidic fibroblast growth factor.

Several strategies will be used to promote participant recruitment, including posting recruitment advertisement on the hospital’s official website and exhibiting posters at conspicuous places in the hospital. Telephone consultation service will be provided for patients who are interested in this study. Screening of potential participants will be carried out by a trial nurse previously trained in the informing and consenting process.

Participant recruitment

Inclusion criteria

Lactating women aged 18 years and older.

Giving birth to their first baby.

Presenting macroscopically detectable nipple fissure and complaining of perceived nipple pain in the first 6 months postpartum.

Full-term pregnancy defined as the gestation lasting 39–41 weeks.

Women presenting with S. aureus colonisation.

No current use of nipple protectors (such as nipple shields and breast shells) for the mother.32

Voluntarily giving informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Women with diagnosed chronic diseases, for example, diabetes, mental disorders, autoimmune diseases and severe anaemia.

Women suffering from diseases or conditions affecting breast feeding, including infectious mastitis, ductal infections, flat or inverted nipples, nipple or subareolar abscess, and fungal infection on breast.

Allergy to aFGF or mupirocin (during screening, an investigator will perform a skin allergy test by applying the investigational drugs on the forearm of the patient and ask her to observe and report any response within the following 24 hours; allergy to the investigational drugs will be detected in the presence of allergic reactions).

Infants suffering from tongue or tooth disorders, such as history of ankyloglossia.

Interventions

Experimental interventions

Participants randomly assigned to the experimental group will be administered mupirocin plus aFGF treatment three times daily for 14 days. The combined treatment includes two steps. First, the breastfeeding mother sprays aFGF on the affected nipple at a dose of 100 IU/cm2 to ensure complete coverage of the nipple. Second, mupirocin ointment will be lightly and evenly applied to the same area following the absorption of the spray liquid. Participants should wash hands and clean nipples gently before the use of drugs and breast feeding.

Comparator interventions

Patients in the control group will be provided with mupirocin and aFGF placebo, and will be required to follow the same treatment regimen as in the experimental group.

Mupirocin ointment is manufactured by Sino-American Tianjin Smith Kline & French Laboratories. Each gram of mupirocin oinment contains 20 mg of its major active ingredient mupirocin in a polyethylene glycol base.

The aFGF is in the form of a spray manufactured by Shanghai Wanxing Bio-Pharmaceuticals. The agent contains 2 mLof freeze-dried powder (25 000 U per tube) soluted in 10 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution. The placebo includes only 10 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution. The aFGF agent and its placebo are indistinguishable from each other in appearance, package and dosage form.28

Women in both groups will be given face-to-face instructions on breastfeeding techniques and hygiene as well as educational pamphlets to take home. To test the mothers’ uptake of the prestudy education and to ensure consistency, they will be asked to nurse her baby in the presence of a female investigator experienced in providing breastfeeding support, thus allowing her newly learnt skills to be evaluated.12

The use of sedative drugs and other pharmacotherapy for nipple fissure and pain is prohibited throughout the study period. If the participant’s pain is unresolved after the period of data collection, we will prescribe a painkiller based on the patient’s preference.

Participants are instructed to discontinue the treatment if they experience allergic reactions or an exacerbation of the condition during the study period and to report to the investigator immediately. When necessary, antiallergy treatment will be provided. Infants developing diarrhoea, skin rashes, milk rejection and mouth ulcers during the study will be referred to a paediatrician.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is nipple pain intensity measured by the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) on day 14 during the treatment period.33 34 VAS consists of a ruler marking a range of scores from 0 to 10 in increments of 1, where 0 represents ‘no pain’ and 10 represents ‘the most intense pain’.35 The difference of mean scores between groups will be evaluated.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures include:

Time to complete nipple pain relief

Time to complete nipple pain relief is the time taken from baseline to the day when the VAS Score is reduced to 0. If the woman still has nipple pain on day 14, time to complete nipple pain relief will be marked as a missing value. We will calculate the incidence of complete nipple pain relief

Changes in the Nipple Trauma Score (NTS)

NTS will be used to measure the extent and depth of nipple trauma, which ranges between 0 and 532 35 (table 1). A study showed that testing of NTS revealed a high interobserver reliability of 0.88.35 The nipple trauma will be evaluated by a dermatoscope.

Table 1.

Explaination of the ratings for the Nipple Trauma Score

| Score | Definition |

| 0 | No microscopically visible skin changes |

| 1 | Erythema or oedema or a combination of both |

| 2 | Superficial damage, with or without scab formation, to less than 25% of the nipple surface |

| 3 | Superficial damage, with or without scab formation, to more than 25% of the nipple surface |

| 4 | Partial-thickness wound, with or without scab formation, affecting less than 25% of the nipple surface |

| 5 | Partial-thickness wound, with or without scab formation, affecting more than 25% of the nipple surface |

Time to complete healing of nipple trauma

Time to complete healing of nipple trauma is the time taken from baseline to the day when the NTS decreased to 0. If the woman still has nipple trauma on day 14, time to complete healing of nipple trauma will be marked as a missing value. We will calculate the incidence of complete healing of nipple trauma.

Quality of life

Quality of life will be measured by the Maternal Postpartum Quality of Life (MAPP-QOL) Questionnaire.36 The patient-reported questionaire contains 41 items, providing a total score ranging from 0 to 30. Higher scores indicate better quality of life.36 The difference of mean scores between groups will be evaluated.

Outcomes associated with the infant feeding

The frequency of breast feeding, the rate of breast feeding discontinuation and weight change in infants will be measured during the treatment period.

Safety outcomes

Any adverse event and reaction observed in both the mother and infant will be recorded. These could be perceived feelings of burning, pricking or tickling on the skin of the nipples, or allergic rash reported by the breastfeeding mother, diarrhoea, rash, milk rejection and dental ulcer observed in the infant. A data monitoring committee (DMC) will be established to monitor and evaluate safety data throughout the study.

Measurement items and time points of data collection

The participants’ information and outcome measurements will be collected at five time points, which are on the day of screening, at baseline and on day 3, day 7 and day 14, during the treatment period. A study flow chart specifying the time schedule for enrolment, intervention, data collection and participant visits is presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Time schedule of participant enrolment, interventions, assessments and visits

| Activity/assessment | Study period | |||||

| −1 | 0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| Prestudy screening/consent (day −1) |

Prestudy baseline/randomisation (day 0) |

Study visit 1 (day 3) |

Study visit 2 (day 7) |

Study visit 3 (day 14) |

||

| Enrolment | Eligibility screen | X | ||||

| Informed consent | X | |||||

| Randomisation | X | |||||

| Characteristic | X | |||||

| Intervention | Mupirocin plus aFGF | ☆————————————☆ | ||||

| Mupirocin plus placebo | ★————————————★ | |||||

| Assessment | VAS for measuring nipple pain | X | X | X | X | |

| NTS | X | X | X | X | ||

| MAPP-QOL | X | X | X | X | ||

| Time to complete nipple pain relief | X | X | X | |||

| Time to complete healing of nipple trauma | X | X | X | |||

| Outcomes associated with the infant feeding | X | X | X | |||

| Adverse events | X | X | X | |||

☆Experimental group; ★ Control group.

aFGF, acidic fibroblast growth factor; MAPP-QOL, Maternal Postpartum Quality Of Life; NTS, Nipple Trauma Score; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale

Patients visiting the outpatient clinic or from the maternity ward will be first screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Potentially eligible participants will be informed of the aim and content of the research, schedule of visits, risks and benefits involved, and the rights and obligations of the participants prior to being asked to give written consent. The recruiting investigators will be trained in informing and consenting patients before enrolling participants to ensure the patients clearly understand the above information.

On the day following the screening visit (day 0), participants will be randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the control group. Date collection will include the following information.

For the breastfeeding mothers: age, marital status, family income per year, education, VAS Score, NTS and MAPP-QOL Score.

For infants: current age (months).

The VAS Score, NTS and MAPP-QOL Score will be measured repeatedly on day 3, day 7 and day 14 blindly by an assessor trained and tested before performing the trial in order to promote consistency of the outcome measurement. The explanations for participant withdrawal and dropout will be sought and recorded by an assessor. Treatment compliance and safety will be monitored daily through the face-to-face interview when patients visit the clinic or telephone communication in the absence of face-to-face meetings. Any adverse event will be recorded and followed up by a senior physician (RF) until the participant returns to normal.

Sample size

We hypothesised that the reduction in average pain intensity measured by VAS is 1 point in the experimental group and 2 points in the control group, both with a standard mean difference of 1.5 points based on previous research.35 A sample size of 50 in each group was estimated with a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 90% by the PASS V.2011 software. In view of a dropout rate of 20%, a total of 120 participants, 60 in each group, are finally required to generate possible statistical difference beteen groups.

Randomisation

Block randomisation will be used with a block size of 4. A statistician independent of the investigators will generate a random allocation sequence by a computer software. When a patient is eligible, the investigator will assign a unique identifier to the patient based on the random allocation sequence. Then the patient will be assigned to either the experimental group or the control group.

Allocation concealment

The investigational drugs are packaged in sealed, opaque boxes of the same size and appearance. Each box is labelled with a unique identifier corresponding to a random number in the allocation sequence before the study commences. The pharmacist dispenses drugs to the patient according to the identifier and provide instructions on the dosage and dosage regimen of the investigational drugs.

Blinding

In this study, the investigators, the patients, the pharmacist and the outcome assessor are all blinded. In the case of a serious adverse event, the investigator will acquire the patient’s allocation information from the statistician.

Data management

A paper case report form (CRF) is composed before the study commences. Each variable is carefully coded for the auditing and statistical analysis.

The patient’s general information will be recorded in the CRF by the responsible investigator, whereas the patient-reported information will be documented in the CRF by the patient, and there are some parts of the CRF to be completed by the outcome assessor.

We will adopt a double entry and double check approach to data management. All the steps involved in data management will be independently conducted by two data administrators using the Epidata software. If any inconsistency is identified in the data entry or logic consistence check, the investigators will be contacted for further information and clarification.

The participants’ identification information (name, telephone, home address, etc) will not be entered into the data management software to protect privacy. The participant’s identification code is the unique identifier for a patient in the data set. After data checking is done, the final version of the data set will be kept in a locked compact disc. The statistician may have access to the complete data set on formal written application to the data administrator.

Harm

Any occurrence of an adverse event needs to be documented in detail, including information on the starting point of symptom appearance, patient symptoms, severity, duration of the condition, any management administered and the final outcome, and so on. In the case of a serious adverse event, the investigatior is responsible for informing the DMC and contacting the statistician for the allocation information of the participant immediatedly after he/she has learnt of the event. A senior physician (RF) will take the necesary remedial medical measures in case of harm to the study participants. We will pay for out-of-pocket expenses if the woman or infant has an adverse reaction that requires treatment.

Auditing

A clinical monitor will visit the study site every 2 weeks to check the progress of the study. Important points to be checked include the conduct of the study has been as per protocol by the investigator, how many patients have been screened and how many have been enrolled, and if all eligible participants have signed the informed consent form. Also, CRFs will be checked for correctness and consistency with the source documents. The monitor will evaluate if the investigators have filled in the CRF and other essential documents in a timely manner, and if errors have been corrected and the corrections signed and dated. Moreover, the monitor needs to make sure any dropout and adverse event is elaborately recorded.

Data monitoring

The DMC, independent of the research investigators, will be established to monitor and evaluate safety data throughout the study, particularly serious adverse events. The DMC is composed of clinicians with expertise in obstetrics and gynaecology, clinical experts experienced in conducting clinical trials and a biostatistician independent of this trial. While the trial is ongoing, DMC members have access to original data but are blinded to participant allocation. If the investigator reports an adverse event, the members of the DMC will hold a meeting to evaluate it. One principal role of the DMC is to provide a written recommendation of the necessity to discontinue a trial following discussion and assessment of safety data, to the investigator, in a timely manner.

Statistical analysis

We will perform an intention-to-treat analysis uisng the SPSS V.22.0 software. A value of p<0.05 is considered statistically significant. For quantitative data, if the normal distribution has been followed, the mean value and SD will be used to describe treatment effects. Otherwise, the median value and IQR will be used to express treatment effects. For binary variables, the percentage or incidence rate is used to describe effect size. Baseline variations between groups will be evaluated by t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. If the baseline variables are similar between groups, the t-test will be used to investigate between-group differences and the paired t-test for within-group differences for quantitative data following normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test for between-group differences and the Wilcoxon test for within-group differences for quantitative data following non-normal distribution. For binary variables, the χ2 test will be used for examining between-group differences. When there are various baseline variables between the groups, proper statistical adjustment approaches (eg, covariance analysis, Cox regression analysis) will be adopted.

Amendments

In case of any amendment to the present protocol, revisions will be submitted to the ethics review committee and the DMC. The revisions, reasons for making such revisions, the date and the new version number will be specified in the final report.

Trial participants, healthcare professionals and the public may get to know the results of our research by reading the published paper. The full protocol, participant-level data set and statistical code will be available by contacting the authors after the final report is published.

Participant confidentiality and data protection

Patient data will be kept strictly confidential. After the database is locked, any patient identification information (such as name, home address) will be eliminated before performing statistical analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved.

Discussion

Currently, there is no standard and optimal treatment for nipple fissure and pain in breastfeeding mothers. Mupirocin is useful against superficial skin infections while aFGF can facilitate repair of skin injury. Because bacterial infections are commonly observed in traumatic nipples, we made the hypothesis that combination therapy is more effective than mupirocin alone in the management of this condition. Findings of this study may provide evidence for the new and probably better treatment option for nursing mothers suffering from nipple fissure and pain.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: XL and JZ made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. XL and JZ wrote the manuscript drafts. RF made significant revisions to the manuscript. All authors read, amended and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is funded by the Tianjin Education Commission’s ‘‘Innovative Team Training Program” (No. TD13-5047). This funding source has no role in the design of this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study has gained approval from the Ethics Review Committee of Tianjin Central Hospital of Gynecology Obstetrics (approval no. 2018KY001).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Medical researchers can obtain individual deidentified participant data collected during the trial, study protocol, statistical analysis plan and analytical code immediately following publication for any purpose by contacting the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization & UNICEF. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42590. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al. . Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016;387:475–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, et al. . Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices?. Lancet 2016;387:491–504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lumbiganon P, Martis R, Laopaiboon M, et al. . Antenatal breastfeeding education for increasing breastfeeding duration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;12:CD006425 10.1002/14651858.CD006425.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Acheson L. Family violence and breast-feeding. Arch Fam Med 1995;4:650–2. 10.1001/archfami.4.7.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, et al. . Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2005;294:2601–10. 10.1001/jama.294.20.2601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sayyah Melli M, Rashidi MR, Delazar A, et al. . Effect of peppermint water on prevention of nipple cracks in lactating primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. Int Breastfeed J 2007;2:7 10.1186/1746-4358-2-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dennis CL, Jackson K, Watson J. Interventions for treating painful nipples among breastfeeding women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;12:CD007366 10.1002/14651858.CD007366.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCann MF, Baydar N, Williams RL. Breastfeeding attitudes and reported problems in a national sample of WIC participants. J Hum Lact 2007;23:314–24. 10.1177/0890334407307882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buck ML, Amir LH, Cullinane M, et al. . Nipple pain, damage, and vasospasm in the first 8 weeks postpartum. Breastfeed Med 2014;9:56–62. 10.1089/bfm.2013.0106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vieira F, Bachion MM, Mota DD, et al. . A systematic review of the interventions for nipple trauma in breastfeeding mothers. J Nurs Scholarsh 2013;45:116–25. 10.1111/jnu.12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morland-Schultz K, Hill PD. Prevention of and therapies for nipple pain: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2005;34:428–37. 10.1177/0884217505276056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kent JC, Ashton E, Hardwick CM, et al. . Nipple Pain in Breastfeeding Mothers: Incidence, Causes and Treatments. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:12247–63. 10.3390/ijerph121012247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Page T, Lockwood C, Guest K. Management of nipple pain and/or trauma associated with breast-feeding. JBI Reports 2003;1:127–47. 10.1046/j.1479-697x.2003.00004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taveras EM, Capra AM, Braveman PA, et al. . Clinician support and psychosocial risk factors associated with breastfeeding discontinuation. Pediatrics 2003;112(1 Pt 1):108–15. 10.1542/peds.112.1.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shanazi M, Farshbaf Khalili A, Kamalifard M, et al. . Comparison of the effects of lanolin, peppermint, and dexpanthenol creams on treatment of traumatic nipples in breastfeeding mothers. J Caring Sci 2015;4:297–307. 10.15171/jcs.2015.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Albright LM. Sore nipples in breastfeeding mothers: causes and treatments. Int J Pharm Compd 2003;7:426–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jackson KT, Dennis CL. Lanolin for the treatment of nipple pain in breastfeeding women: a randomized controlled trial. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13:e12357 10.1111/mcn.12357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Livingstone V, Stringer LJ. The treatment of Staphyloccocus aureus infected sore nipples: a randomized comparative study. J Hum Lact 1999;15:241–6. 10.1177/089033449901500315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Amir LH, Donath SM, Garland SM, et al. . Does Candida and/or Staphylococcus play a role in nipple and breast pain in lactation? A cohort study in Melbourne, Australia. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002351 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Livingstone VH, Willis CE, Berkowitz J. Staphylococcus aureus and sore nipples. Can Fam Physician 1996;42:654–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu X, Deng S, Huang J, et al. . Dissemination of macrolides, fusidic acid and mupirocin resistance among Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Oncotarget 2017;8:58086–97. 10.18632/oncotarget.19491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kotloff KL, Shirley DT, Creech CB, et al. . Mupirocin for staphylococcus aureus decolonization of infants in neonatal intensive care units. Pediatrics 2019;143:e20181565 10.1542/peds.2018-1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun BK, Siprashvili Z, Khavari PA. Advances in skin grafting and treatment of cutaneous wounds. Science 2014;346:941–5. 10.1126/science.1253836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bennett NT, Schultz GS. Growth factors and wound healing: biochemical properties of growth factors and their receptors. Am J Surg 1993;165:728–37. 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80797-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bennett NT, Schultz GS. Growth factors and wound healing: Part II. Role in normal and chronic wound healing. Am J Surg 1993;166:74–81. 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80589-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mohan SK, Rani SG, Yu C. The heterohexameric complex structure, a component in the non-classical pathway for fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) secretion. J Biol Chem 2010;285:15464–75. 10.1074/jbc.M109.066357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ma B, Cheng DS, Xia ZF, et al. . Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial using topical recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor for deep partial-thickness burns and skin graft donor site. Wound Repair Regen 2007;15:795–9. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pineda-Lucena A, Núñez De Castro I, Lozano RM, et al. . Effect of low pH and heparin on the structure of acidic fibroblast growth factor. Eur J Biochem 1994;222:425–31. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhong Y, Chen Q, Li W, et al. . IV multicenter randomized positive drug controlled clinical trial of aFGF and bFGF in treatment with shallow II burns. China Medical Engineering 2014;22:11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vieira F, Mota D, Castral TC, et al. . Effects of anhydrous lanolin versus breast milk combined with a breast shell for the treatment of nipple trauma and pain during breastfeeding: A randomized clinical trial. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017;62:572–9. 10.1111/jmwh.12644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gift AG. Visual analogue scales: measurement of subjective phenomena. Nurs Res 1989;38:286–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buchko BL, Pugh LC, Bishop BA, et al. . Comfort measures in breastfeeding, primiparous women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1994;23:46–52. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1994.tb01849.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abou-Dakn M, Fluhr JW, Gensch M, et al. . Positive effect of HPA lanolin versus expressed breastmilk on painful and damaged nipples during lactation. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2011;24:27–35. 10.1159/000318228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hill PD, Aldag JC, Hekel B, et al. . Maternal postpartum quality of life questionnaire. J Nurs Meas 2006;14:205–20. 10.1891/jnm-v14i3a005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.