Nonenveloped viruses rely on protein-protein interactions to shield their genomes from the environment. The capsid, or protective shell, must also disassemble during cell entry. In this work, we identified a determinant within mammalian orthoreovirus that regulates heat resistance, disassembly kinetics, and replicative fitness. Together, these findings show capsid function is balanced for optimal replication and for spread to a new host.

KEYWORDS: capsid, conformational change, infectivity, nonenveloped virus, reovirus, thermostability

ABSTRACT

The environment represents a significant barrier to infection. Physical stressors (heat) or chemical agents (ethanol) can render virions noninfectious. As such, discrete proteins are necessary to stabilize the dual-layered structure of mammalian orthoreovirus (reovirus). The outer capsid participates in cell entry: (i) σ3 is degraded to generate the infectious subviral particle, and (ii) μ1 facilitates membrane penetration and subsequent core delivery. μ1-σ3 interactions also prevent inactivation; however, this activity is not fully characterized. Using forward and reverse genetic approaches, we identified two mutations (μ1 M258I and σ3 S344P) within heat-resistant strains. σ3 S344P was sufficient to enhance capsid integrity and to reduce protease sensitivity. Moreover, these changes impaired replicative fitness in a reassortant background. This work reveals new details regarding the determinants of reovirus stability.

IMPORTANCE Nonenveloped viruses rely on protein-protein interactions to shield their genomes from the environment. The capsid, or protective shell, must also disassemble during cell entry. In this work, we identified a determinant within mammalian orthoreovirus that regulates heat resistance, disassembly kinetics, and replicative fitness. Together, these findings show capsid function is balanced for optimal replication and for spread to a new host.

INTRODUCTION

Nonenveloped viruses are versatile models to explore the properties of single- or multilayered structures. The balance between stability and flexibility is a key determinant of infection (1). This dynamic is well established for simple systems, such as poliovirus (2–9), but is only partially understood for more complex systems, such as mammalian orthoreovirus (reovirus). Reovirus is composed of two concentric protein shells (10). Each component serves a structural and/or functional role in the replication cycle. The inner capsid (core) encapsidates 10 segments of genomic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (11) and supports polymerase activity during infection (12–14). The core is highly stable, presumably to shield the viral genome from host sensors (15). The outer capsid comprises 200 μ1-σ3 heterohexamers and a maximum of 12 σ1 trimers (10, 16) and is required for cell entry (11). μ1 rearranges following exposure to inactivating agents (15, 17, 18), whereas σ3 represents the primary determinant for virion thermostability (19).

Reovirus initiates infection by attaching to proteinaceous receptors (20–22) or serotype-specific glycans (23–26). Virions are internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis (27–30) and traffic to late endosomes (31–35). Acid-dependent cathepsin proteases degrade σ3 (36–40) and cleave μ1 into μ1δ and Φ (see Fig. 2A) (41). The resulting intermediate is called the infectious subviral particle (ISVP) (42). Proteolytic disassembly (virion-to-ISVP conversion) is recapitulated in vitro by treating purified virions with exogenous protease (41–43). During subsequent rearrangements (ISVP-to-ISVP* conversion), neighboring μ1 trimers separate (16, 44) and μ1δ is cleaved into μ1N and δ (see Fig. 2A) (45, 46). The δ fragment then adopts a hydrophobic and protease-sensitive conformation (17). This step is accompanied by the release of μ1N and Φ pore-forming peptides, which disrupt the endosomal membrane (17, 45–51). ISVP-to-ISVP* conversion can be triggered in vitro using heat (17, 18).

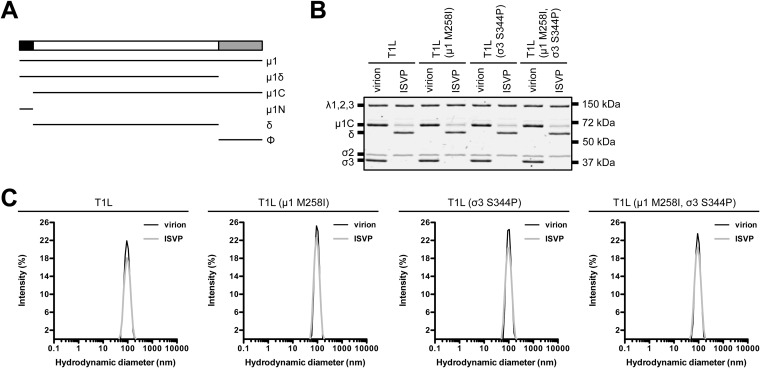

FIG 2.

Protein compositions and size distribution profiles of T1L variants. (A) Schematic of μ1 cleavage fragments. (B) Protein compositions. T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), and T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions and ISVPs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gel was Coomassie brilliant blue stained. The migration of capsid proteins is indicated on the left. μ1 resolves as μ1C, and μ1δ resolves as δ (45). μ1N and Φ are too small to resolve on the gel (n = 3 independent replicates; results from 1 representative experiment are shown). (C) Size distribution profiles. T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), or T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions or ISVPs were analyzed by dynamic light scattering. For each variant, the virion (black) and ISVP (gray) size distribution profiles are overlaid (n = 3 independent replicates; results from 1 representative experiment are shown).

Reovirus must remain stable prior to infection; environmental assault can render particles noninfectious (19, 52). Nonetheless, due to error-prone replication, rare subpopulations harbor resistance-granting mutations. Studies of such variants provide new insights into capsid structure and stability. In comparisons of prototype strains, differences in the efficiency of inactivation map to either the M2 gene segment (encodes μ1) or the S4 gene segment (encodes σ3) (17–19). μ1 mutations were selected by exposing virions to a chemical agent (ethanol) or by exposing ISVPs to a physical stressor (heat). These changes reveal important μ1-mediated intratrimer, intertrimer, and trimer-core contacts (53–56). σ3 Y354H was selected from persistently infected cells. This change alters capsid properties and allows for disassembly under limiting cathepsin activity (57, 58). μ1-σ3 interactions are thought to prevent irreversible and premature entry-related conformational changes; however, this idea has not been fully investigated. In this work, we selected for and characterized heat-resistant (HR) strains: (i) μ1 M258I and σ3 S344P were identified within HR strains, (ii) σ3 S344P was sufficient to enhance capsid integrity and to reduce protease sensitivity, and (iii) HR mutations impaired replicative fitness in a reassortant background.

(This article was submitted to an online preprint archive [59].)

RESULTS

Characterization of putative HR strains.

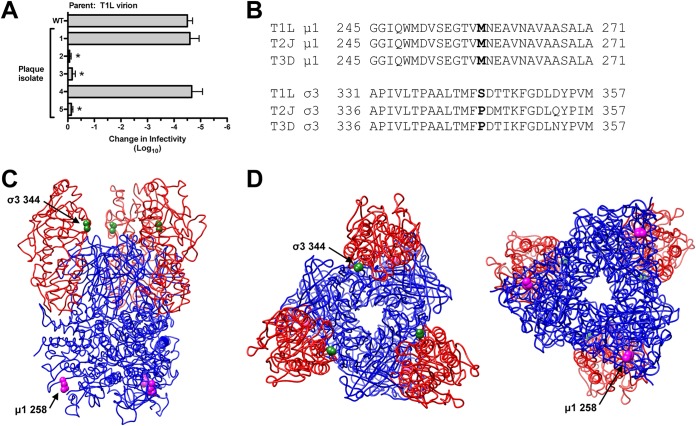

Reovirus is susceptible to environmental factors (19, 52). The loss of infectivity is correlated with outer capsid rearrangements (15, 17, 18). To isolate HR strains, type 1 Lang (T1L) virions were incubated at 55°C. The virus titer decreased by ∼5.5 log10 units compared to that of the input (data not shown). Survivors were plaque purified and used to generate infected cell lysates. Three plaque isolates (out of 5) exhibited a bona fide HR phenotype (Fig. 1A). Sequencing of the μ1- and σ3-encoding gene segments (M2 and S4, respectively) revealed two mutations within each HR strain: μ1 M258I and σ3 S344P (Fig. 1B). These residues, which are not expected to interact, occupy distinct positions within the T1L μ1-σ3 heterohexamer (Fig. 1C and D) (16).

FIG 1.

Selection, isolation, and sequencing of heat-resistant strains. (A) Thermal inactivation. T1L virions were incubated for 5 min at 55°C. Surviving strains were plaque purified and amplified on L cells. To verify heat resistance, the infected cell lysates were incubated for 5 min at 55°C. The change in infectivity relative to that of samples incubated at 4°C was determined by plaque assay. The data are presented as means ± SD. *, P ≤ 0.05 and difference in change in infectivity of ≥2 log10 units (n = 3 independent replicates). (B) Multiple-sequence alignments. Residues corresponding to μ1 258 and σ3 344 are in boldface. T1L, T2J, and T3D represent the prototype strains for their respective mammalian orthoreovirus serotypes (11). (C) Side view of the T1L μ1-σ3 heterohexamer (16) (PDB accession number 1JMU). (D) Top and bottom views (left and right, respectively) of the T1L μ1-σ3 heterohexamer (16) (PDB accession number 1JMU). In panels C and D, μ1 monomers are colored blue, σ3 monomers are colored red, μ1 258 is represented by magenta spheres, and σ3 344 is represented by green spheres.

σ3 S344P was sufficient to enhance capsid integrity.

Changes within other capsid components (σ1 and core proteins) could influence the HR phenotype. To address this concern, we reintroduced μ1 M258I and σ3 S344P into otherwise T1L backgrounds (Table 1). Variants with one or both mutations displayed no observable defects in protein composition or protein stoichiometry. Due to autocatalytic activity, μ1 resolves as μ1C and μ1δ resolves as δ (Fig. 2A and B) (45). We also analyzed virions and ISVPs by dynamic light scattering (DLS). In each case, we detected a single peak; subsequent analyses were not affected by aggregation (Fig. 2C).

TABLE 1.

Recombinant reoviruses used in this study

| Virus | Deriving strain fora: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| μ1 | σ3 | Remaining proteinsb | |

| T1L | T1L | T1L | T1L |

| T1L (μ1 M258I) | T1L (μ1 M258I) | T1L | T1L |

| T1L (σ3 S344P) | T1L | T1L (σ3 S344P) | T1L |

| T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) | T1L (μ1 M258I) | T1L (σ3 S344P) | T1L |

| T1L/T3D M2 | T3D | T1L | T1L |

| T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) | T3D (μ1 M258I) | T1L (σ3 S344P) | T1L |

Mutations are indicated in parentheses.

λ1, λ2, λ3, μNS, μNSC, μ2, σNS, σ2, σ1, and σ1s.

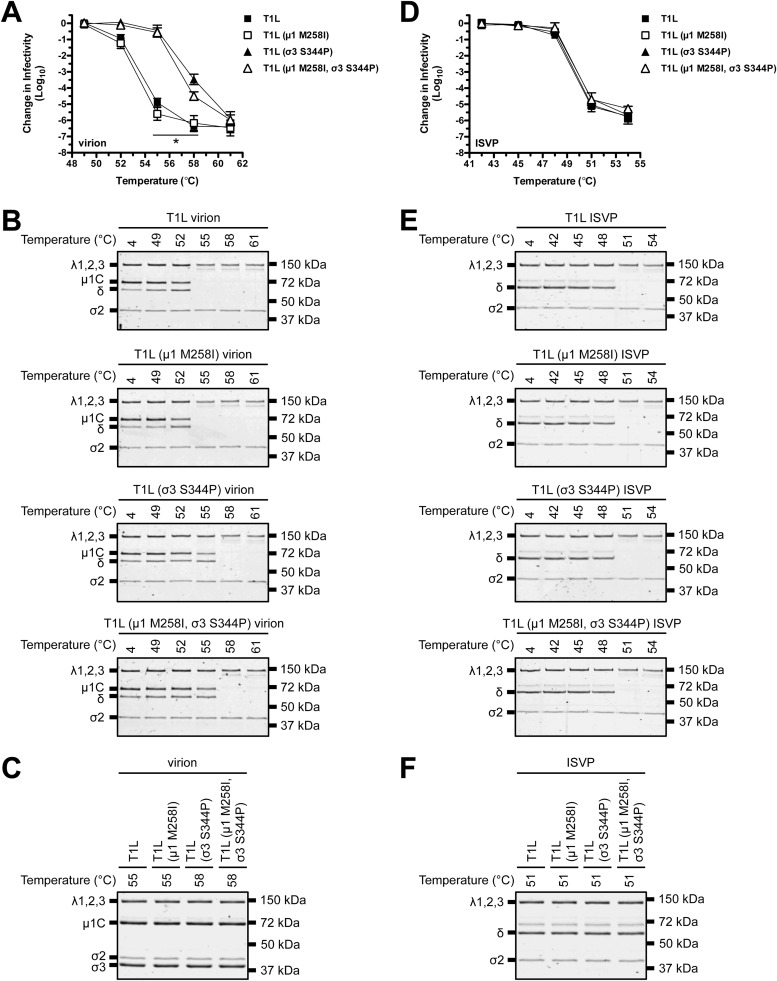

The S4 gene segment (encodes σ3) contains the genetic determinants for virion thermostability (19). σ3 preserves infectivity by stabilizing μ1 (15). Any change that affects μ1-σ3 structure could modulate this activity. To test this idea, we performed thermal inactivation experiments. Following incubation at 55°C, T1L and T1L (μ1 M258I) virions were reduced in titer by ∼5.5 log10 units relative to the control, which was incubated at 4°C. In contrast, T1L (σ3 S344P) and T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions were reduced in titer by ∼0.5 log10 units after incubation at 55°C and by ∼4.0 log10 units after incubation at 58°C (Fig. 3A). Virion-associated μ1 adopts an ISVP*-like (protease-sensitive) conformation concurrent with inactivation. This transition is assayed in vitro by determining the susceptibility of μ1 to trypsin digestion (15, 17, 18). Consistent with the above-described results, 55°C was the minimal temperature at which μ1 in T1L and T1L (μ1 M258I) virions became trypsin sensitive, whereas 58°C was the minimal temperature at which μ1 in T1L (σ3 S344P) and T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions became trypsin sensitive (Fig. 3B). Of note, σ3 was absent from gels and μ1 migrated as uncleaved μ1C and cleaved δ. Trypsin, which was used to probe for protease sensitivity, degrades σ3 and cleaves at the μ1 δ-Φ junction (41). Heating alone was not sufficient to alter μ1 or σ3 levels (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Thermostability of T1L variants. (A and D) Thermal inactivation. T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), or T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions (A) or ISVPs (D) were incubated in virus storage buffer for 5 min at the indicated temperatures. The change in infectivity relative to that of samples incubated at 4°C was determined by plaque assay. The data are presented as means ± SD. *, P ≤ 0.05 and difference in change in infectivity of ≥2 log10 units (n = 3 independent replicates). (B and E) Heat-induced conformational changes. T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), or T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions (B) or ISVPs (E) were incubated in virus storage buffer for 5 min at the indicated temperatures. Each reaction mixture was then treated with trypsin for 30 min on ice. Following digestion, equal particle numbers from each reaction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gels were Coomassie brilliant blue stained (n = 3 independent replicates; results from 1 representative experiment are shown). (C and F). Composition of heated virus. T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), or T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions (C) or ISVPs (F) were incubated in virus storage buffer for 5 min at the indicated temperatures. Equal particle numbers from each reaction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gels were Coomassie brilliant blue stained (n = 3 independent replicates; results from 1 representative experiment are shown).

The M2 gene segment (encodes μ1) contains the genetic determinants for ISVP thermostability. The transition to ISVP* induces the loss of infectivity (17, 18). Following incubation at 51°C, T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), and T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) ISVPs were reduced in titer by ∼5.0 log10 units (Fig. 3D). Thus, HR mutations conferred stability only within the context of a virion (σ3 degradation restored wild-type-like heat sensitivity). Protease treatment also serves as a biochemical probe for ISVP* formation (17, 18). For each variant, δ (a product of μ1 cleavage) (Fig. 2A) became trypsin sensitive at 51°C (Fig. 3E). Heating alone was not sufficient to induce the loss of δ (Fig. 3F).

σ3 S344P was sufficient to reduce protease sensitivity.

Proteolytic disassembly (virion-to-ISVP conversion) is required for reovirus to establish an infection (39). T1L σ3 is more protease sensitive than T3D σ3; cleavage initially occurs in a hypersensitive region between 238 and 250 or between 208 and 214, respectively. Using recombinant protein, this difference maps to polymorphisms at σ3 344, 347, and 353 (60). σ3 354 also regulates capsid properties (58). This region is shared with our HR mutation, suggesting a role in disassembly kinetics. To test this idea, virions were digested in vitro with endoproteinase LysC (EKC). EKC probes for subtle differences in structure (60, 61). T1L and T1L (μ1 M258I) σ3 were degraded within 40 min. In contrast, T1L (σ3 S344P) and T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) σ3 persisted (in part) for 100 min (Fig. 4A). We next tested the sensitivity to intracellular proteases. Cathepsins B and L require endosomal acidification for activity. As such, lysosomotropic weak bases (ammonium chloride [AC]) block infection (39, 62). Murine L929 (L) cells were adsorbed with virions, and viral yield was quantified at 24 h postinfection. Where indicated, the growth medium was supplemented with AC. The timing of AC escape is related to the rate of disassembly (39). Consistent with the above-described results, T1L and T1L (μ1 M258I) bypassed the block to infection with faster kinetics (viral yield of ∼1.5 log10 units when AC was added at 60 min) than T1L (σ3 S344P) and T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) (viral yield of ∼1.5 log10 units when AC was added at 90 min) (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that HR mutations reduce protease sensitivity. Of note, we did not observe a phenotype for μ1 M258I, which lies adjacent to the core (Fig. 1C and D) (16). Changes in σ2, λ1, and λ2 (core proteins) could alter capsid properties individually or in combination. Nonetheless, this work focused on μ1 and σ3 (outer capsid proteins).

FIG 4.

Degradation of σ3 by exogenous or intracellular protease. (A) Exogenous protease. T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), or T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions were incubated in virus storage buffer supplemented with endoproteinase LysC for the indicated amounts of time at 37°C. 0+ time points were quenched immediately after mixing. Following digestion, equal particle numbers were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gels were Coomassie brilliant blue stained (n = 3 independent replicates; results from 1 representative experiment are shown). (B) Intracellular proteases. L cell monolayers were infected with T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), or T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions. At the indicated times postinfection, the growth medium was supplemented with ammonium chloride. At 24 h postinfection, the cells were lysed and viral yield was quantified by plaque assay. The data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). Unt, untreated.

HR mutations altered capsid properties in a reassortant background.

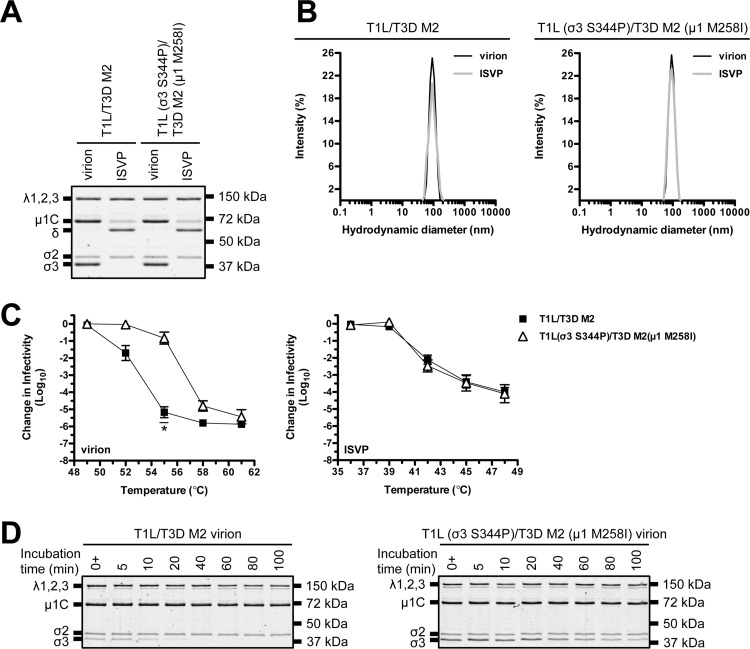

T1L × type 3 Dearing (T3D) reassortants are used extensively to study many aspects of the viral replication cycle (11). For example, T1L/T3D M2 contains mismatched subunits (μ1 is derived from T3D, whereas σ3 and core proteins are derived from T1L). Virions with imperfect interactions retain wild-type-like stability and structure (15); however, HR mutations could function in a background-dependent manner. To address this question, we generated T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) (Table 1). This virus displayed no observable defects in protein composition, protein stoichiometry, or particle size distribution (Fig. 5A and B). We next tested the impact on capsid properties. Following incubation at 55°C, T1L/T3D M2 virions were reduced in titer by ∼5.5 log10 units, whereas T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions were reduced in titer by ∼1.0 log10 unit. In contrast, ISVPs were equally thermostable (Fig. 5C). HR mutations also conferred differential sensitivity to EKC. T1L/T3D M2 σ3 was degraded within 40 min, whereas T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) σ3 persisted (in part) for 100 min (Fig. 5D).

FIG 5.

Thermostability of a T1L/T3D M2 variant. (A) Protein compositions. T1L/T3D M2 and T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions and ISVPs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gel was Coomassie brilliant blue stained. The migration of capsid proteins is indicated on the left. μ1 resolves as μ1C, and μ1δ resolves as δ (45). μ1N and Φ are too small to resolve on the gel (n = 3 independent replicates; results from 1 representative experiment are shown). (B) Size distribution profiles. T1L/T3D M2 or T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions or ISVPs were analyzed by dynamic light scattering. For each variant, the virion (black) and ISVP (gray) size distribution profiles are overlaid (n = 3 independent replicates; results from 1 representative experiment are shown). (C) Thermal inactivation. T1L/T3D M2 or T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions or ISVPs were incubated in virus storage buffer for 5 min at the indicated temperatures. The change in infectivity relative to that of samples incubated at 4°C was determined by plaque assay. The data are presented as means ± SD. *, P ≤ 0.05 and difference in change in infectivity of ≥2 log10 units (n = 3 independent replicates). (D) Degradation of σ3 by exogenous protease. T1L/T3D M2 or T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions were incubated in virus storage buffer supplemented with endoproteinase LysC for the indicated amounts of time at 37°C. 0+ time points were quenched immediately after mixing. Following digestion, equal particle numbers were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gels were Coomassie brilliant blue stained (n = 3 independent replicates; results from 1 representative experiment are shown).

HR mutations impaired replicative fitness in a reassortant background.

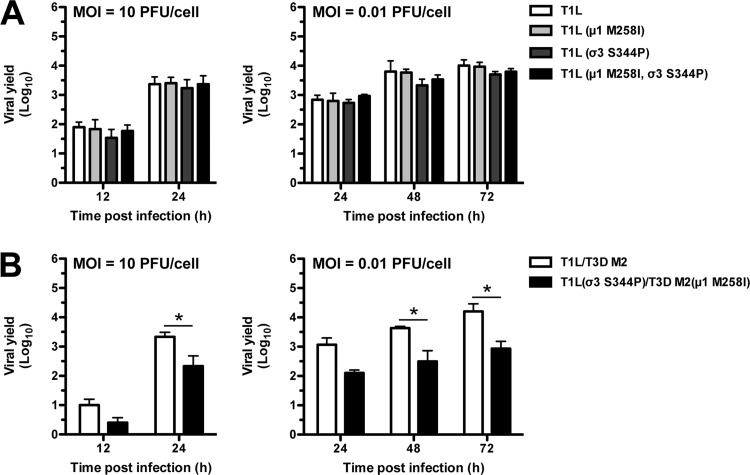

Reovirus disassembles efficiently during cell entry yet remains stable in the environment. This balance is necessary for a productive infection and for spread to a new host (1, 11). HR mutations are favored at high temperatures (Fig. 3 and 5). We next examined their impact under physiological conditions. L cells were infected at high (10 PFU/cell) or low (0.01 PFU/cell) multiplicity of infection (MOI), and viral yield was quantified at the indicated times postinfection. Each T1L variant grew to similar levels (Fig. 6A). Thus, biochemical differences (described above) do not confer a selective advantage (or impediment) during a bona fide infection. In contrast, T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) produced fewer infectious units than T1L/T3D M2 by 24 h postinfection (high MOI) and by 48 and 72 h postinfection (low MOI) (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, we attempted to isolate unique HR strains in the reassortant background; however, each plaque isolate failed secondary screening (data not shown). The reduced viral yield and the absence (or low abundance) of resistant strains imply a replication defect.

FIG 6.

Growth profiles of T1L and T1L/T3D M2 variants. (A and B) L cell monolayers were infected with virions at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell or 0.01 PFU/cell. At the indicated times postinfection, the cells were lysed and viral yield was quantified by plaque assay. The data are presented as means ± SD. *, P ≤ 0.05 and difference in viral yield of ≥1 log10 unit (n = 3 independent replicates).

DISCUSSION

Resistance-granting mutations are tools to understand structure-function relationships, the basis (or mechanism) of inactivation, and replicative fitness. Toward this end, we selected for rare subpopulations at high temperature (Fig. 1 and 2). HR strains contained two mutations within μ1-σ3. μ1 M258I was not associated with a phenotype, whereas σ3 S344P was sufficient to enhance capsid integrity (Fig. 3) and to reduce protease sensitivity (Fig. 4). These results likely reflect a change in structure. Interestingly, σ3 344 does not interact directly with μ1 (Fig. 1C and D).

HR mutations impaired replicative fitness in a background-dependent manner (Fig. 6). For reovirus, genotype-specific effects are not uncommon. σ3 Y354H in T3D reduces heat resistance and increases protease sensitivity. These properties are not shared with type 3 Abney, which naturally incorporates σ3 H354 (58). Reassortment can also generate unique phenotypes. Mismatches between σ1-λ2 affect ISVP-to-ISVP* conversion (63), whereas mismatches between μ1-σ3 and/or μ1-core affect cell attachment (64). Replication is regulated in a similar manner; λ3 affects tropism in certain backgrounds (65). Nonetheless, our work supports the idea that imperfect (or suboptimal) interactions confer a fitness cost.

σ3 facilitates cell entry (36–40), particle assembly (66–71), and environmental stability (19). Moreover, differences in the efficiency of translational shutdown map to the S4 gene segment (encodes σ3) (72). This effect may be direct or indirect by countering protein kinase R through σ3-dsRNA interactions (73, 74). σ3 function relies on its subcellular localization and its capacity to remain unbound from μ1; the affinity between μ1-σ3 varies based on strain (75). Thus, HR mutations could impact these activities. Mechanistic studies are needed to dissect the relationship between the host and hyperstable reovirus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Murine L929 (L) cells were grown at 37°C in Joklik’s minimal essential medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 25 ng/ml amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). All viruses used in this study were derived from reovirus type 1 Lang (T1L) and reovirus type 3 Dearing (T3D) and were generated by plasmid-based reverse genetics (76, 77). Mutations within the T1L S4, T1L M2, and T3D M2 genes were generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies). S344P in T1L σ3 was made using the following primer pair: forward, 5′-CTGCTCTCACAATGTTCCCGGACACCACCAAGTTCGG-3′, and reverse, 5′-CCGAACTTGGTGGTGTCCGGGAACATTGTGAGAGCAG-3′. M258I in T1L μ1 was made using the following primer pair: forward, 5′-TCAGAAGGAACTGTGATTAATGAGGCCGTGAATGC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCATTCACGGCCTCATTAATCACAGTTCCTTCTGA-3′. M258I in T3D μ1 was made using the following primer pair: forward, 5′-ACGTATCAGAAGGCACCGTGATTAACGAGGCTGTC-3′, and reverse, 5′-CAGCCTCGTTAATCACGGTGCCTTCTGATACGT-3′.

Virion purification.

Recombinant reoviruses T1L, T1L/T3D M2, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P), and T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) were propagated and purified as previously described (76, 77). All variants of T1L/T3D M2 contained a T3D M2 gene in an otherwise T1L background. L cells infected with second-passage reovirus stocks were lysed by sonication. Virions were extracted from lysates using Vertrel-XF specialty fluid (Dupont) (78). The extracted particles were layered onto 1.2- to 1.4-g/cm3 CsCl step gradients. The gradients were then centrifuged at 187,000 × g for 4 h at 4°C. Bands corresponding to purified virions (∼1.36 g/cm3) (79) were isolated and dialyzed into virus storage buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl). Following dialysis, the particle concentration was determined by measuring the optical density of the purified virion stocks at 260 nm (OD260; 1 unit at OD260 is 2.1 × 1012 particles/ml) (80). The purification of virions was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue (Sigma-Aldrich) staining.

Selection and isolation of HR strains.

T1L virions (2 × 1012 particles/ml) were incubated for 5 min at 55°C in an S1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). The total volume of the reaction mixture was 30 μl in virus storage buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl). Following incubation, 10 μl was analyzed by plaque assay. Putative HR strains were plaque purified at 5 days postinfection. Next, L cell monolayers in 60-mm dishes (Greiner Bio-One) were adsorbed with the isolated plaques for 1 h at 4°C. Following the viral attachment incubation, the monolayers were washed three times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and overlaid with 2 ml of Joklik’s minimal essential medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 25 ng/ml amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were incubated at 37°C until cytopathic effect was observed and then lysed by two freeze-thaw cycles (first passage). To verify heat resistance, the infected cell lysates were incubated for 5 min at 55°C in an S1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). The total volume of each reaction mixture was 30 μl. For each isolate, an aliquot was also incubated for 5 min at 4°C. Following incubation, 10 μl of each reaction mixture was diluted into 40 μl of ice-cold virus storage buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl), and infectivity was determined by plaque assay. The change in infectivity was calculated using the following formula: log10(PFU/ml)55°C − log10(PFU/ml)4°C.

Sequencing of HR strains.

L cell monolayers in 60-mm dishes (Greiner Bio-One) were adsorbed with first-passage, verified HR strains for 1 h at 4°C. Following the viral attachment incubation, the monolayers were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and overlaid with 2 ml of Joklik’s minimal essential medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 25 ng/ml amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). At 24 h postinfection, the cells were lysed with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center). Viral RNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction and then subjected to reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using T1L S4 or T1L M2 gene segment-specific primers. PCR products were resolved on Tris-acetate-EDTA agarose gels, purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen), and sequenced. The identified mutations were reintroduced into otherwise T1L and T1L/T3D M2 backgrounds.

Sequence analysis.

Multiple-sequence alignments were created using the Clustal Omega program (81).

Structure analysis.

Molecular graphics were created using the UCSF Chimera program (82).

Generation of ISVPs.

T1L, T1L/T3D M2, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P), or T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions (2 × 1012 particles/ml) were digested with 200 μg/ml TLCK (Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone)-treated chymotrypsin (Worthington Biochemical) in a total volume of 100 μl for 20 min at 32°C (42, 43). The reaction mixtures were then incubated on ice for 20 min and quenched by the addition of 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Sigma-Aldrich). The generation of ISVPs was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue (Sigma-Aldrich) staining.

Dynamic light scattering.

T1L, T1L/T3D M2, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P), or T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions or ISVPs (2 × 1012 particles/ml) were analyzed using a Zetasizer Nano S dynamic light scattering system (Malvern Instruments). All measurements were made at room temperature in a quartz Suprasil cuvette with a 3.00-mm path length (Hellma Analytics). For each sample, the size distribution profile was determined by averaging readings across 15 iterations.

Thermal inactivation and trypsin sensitivity assays.

T1L, T1L/T3D M2, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P), or T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions or ISVPs (2 × 1012 particles/ml) were incubated for 5 min at the indicated temperatures in an S1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). The total volume of each reaction mixture was 30 μl in virus storage buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl). For each reaction condition, an aliquot was also incubated for 5 min at 4°C. Following incubation, 10 μl of each reaction mixture was diluted into 40 μl of ice-cold virus storage buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl), and infectivity was determined by plaque assay. The change in infectivity at a given temperature (T) was calculated using the following formula: log10(PFU/ml)T − log10(PFU/ml)4°C. The titers of the 4°C control samples were between 5 × 109 and 5 × 1010 PFU/ml. The remaining 20 μl of each reaction mixture were either mock treated or treated with 0.08 mg/ml trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min on ice. Following digestion, equal particle numbers from each reaction were solubilized in reducing SDS sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gels were Coomassie brilliant blue (Sigma-Aldrich) stained and imaged on an Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR).

Degradation of σ3 by exogenous protease.

T1L, T1L/T3D M2, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P), or T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions (2 × 1012 particles/ml) were incubated in the presence of 10 μg/ml endoproteinase LysC (New England Biolabs) at 37°C in an S1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). The starting volume of each reaction mixture was 100 μl in virus storage buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl). At the indicated time points, 10 μl of each reaction mixture was solubilized in reducing SDS sample buffer and boiled for 10 min at 95°C. Equal particle numbers from each time point were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gels were Coomassie brilliant blue (Sigma-Aldrich) stained and imaged on an Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR).

AC escape assay.

L cell monolayers in 6-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) were adsorbed with T1L, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), or T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P) virions (10 PFU/cell) for 1 h at 4°C. Following the viral attachment incubation, the monolayers were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and overlaid with 2 ml of Joklik’s minimal essential medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 25 ng/ml amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were either lysed immediately by two freeze-thaw cycles (input) or incubated at 37°C (start of infection). At the indicated times postinfection, the growth medium was supplemented with 20 mM AC (Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals). At 24 h postinfection, the cells were lysed by two freeze-thaw cycles and the virus titer was determined by plaque assay. The viral yield for each infection condition (timing of AC addition) (t) was calculated using the following formula: log10(PFU/ml)t − log10(PFU/ml)input. The titers of the input samples were between 1 × 105 and 4 × 105 PFU/ml.

Single- and multistep growth assays.

L cell monolayers in 6-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) were adsorbed with T1L, T1L/T3D M2, T1L (μ1 M258I), T1L (σ3 S344P), T1L (μ1 M258I, σ3 S344P), or T1L (σ3 S344P)/T3D M2 (μ1 M258I) virions (10 PFU/cell or 0.01 PFU/cell) for 1 h at 4°C. Following the viral attachment incubation, the monolayers were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and overlaid with 2 ml of Joklik’s minimal essential medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 25 ng/ml amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were either lysed immediately by two freeze-thaw cycles (input) or incubated at 37°C (start of infection). At the indicated times postinfection, the cells were lysed by two freeze-thaw cycles and the virus titer was determined by plaque assay. The viral yield at a given time postinfection (t) was calculated using the following formula: log10(PFU/ml)t − log10(PFU/ml)input. Following infection with 10 PFU/cell, the titers of the input samples were between 1 × 105 and 4 × 105 PFU/ml. Following infection at 0.01 PFU/cell, the titers of the input samples were between 1 × 102 and 3 × 102 PFU/ml.

Plaque assay.

Control or heat-treated virus samples or infected cell lysates were diluted in PBS supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2 (PBSMg). L cell monolayers in 6-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) were infected with 250 μl of diluted virus for 1 h at room temperature. Following the viral attachment incubation, the monolayers were overlaid with 4 ml of serum-free medium 199 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 1% Bacto agar (BD Biosciences), 10 μg/ml TLCK-treated chymotrypsin (Worthington Biochemical), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 25 ng/ml amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). The infected cells were incubated at 37°C, and plaques were counted at 5 days postinfection.

Statistical analysis.

Unless noted otherwise, the reported values represent the means from three independent biological replicates. Error bars indicate standard deviations (SD). P values were calculated using Student's t test (two-tailed, unequal variance assumed). For thermal inactivation experiments (Fig. 1A, 3A, and 5C), two criteria were used to assign significance: P value of ≤0.05 and difference in change in infectivity of ≥2 log10 units. For single- and multistep growth experiments (Fig. 6), two criteria were used to assign significance: a P value of ≤0.05 and difference in viral yield of ≥1 log10 unit.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of our laboratory and the Indiana University virology community for helpful suggestions. Dynamic light scattering was performed in the Indiana University Physical Biochemistry Instrumentation Facility.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers 2R01AI110637 (to P.D.) and F32AI126643 (to A.J.S.) and by Indiana University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flint SJ, Racaniello VR, Rall GF, Skalka AM, Enquist LW. 2015. Principles of virology, 4th ed ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeyemi OO, Nicol C, Stonehouse NJ, Rowlands DJ. 2017. Increasing type 1 poliovirus capsid stability by thermal selection. J Virol 91:e01586-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01586-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Palma AM, Vliegen I, De Clercq E, Neyts J. 2008. Selective inhibitors of picornavirus replication. Med Res Rev 28:823–884. doi: 10.1002/med.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Q, Yafal AG, Lee YM, Hogle J, Chow M. 1994. Poliovirus neutralization by antibodies to internal epitopes of VP4 and VP1 results from reversible exposure of these sequences at physiological temperature. J Virol 68:3965–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin J, Lee LY, Roivainen M, Filman DJ, Hogle JM, Belnap DM. 2012. Structure of the Fab-labeled “breathing” state of native poliovirus. J Virol 86:5959–5962. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05990-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McSharry JJ, Caliguiri LA, Eggers HJ. 1979. Inhibition of uncoating of poliovirus by arildone, a new antiviral drug. Virology 97:307–315. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ofori-Anyinam O, Vrijsen R, Kronenberger P, Boeyé A. 1995. Heat stabilized, infectious poliovirus. Vaccine 13:983–986. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(95)00036-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roivainen M, Piirainen L, Rysa T, Narvanen A, Hovi T. 1993. An immunodominant N-terminal region of VP1 protein of poliovirion that is buried in crystal structure can be exposed in solution. Virology 195:762–765. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiomi H, Urasawa T, Urasawa S, Kobayashi N, Abe S, Taniguchi K. 2004. Isolation and characterisation of poliovirus mutants resistant to heating at 50 degrees Celsius for 30 min. J Med Virol 74:484–491. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Ji Y, Zhang L, Harrison SC, Marinescu DC, Nibert ML, Baker TS. 2005. Features of reovirus outer capsid protein mu1 revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction of the virion at 7.0 Angstrom resolution. Structure 13:1545–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dermody T, Parker J, Sherry B. 2013. Orthoreoviruses In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tao Y, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. 2002. RNA synthesis in a cage–structural studies of reovirus polymerase lambda3. Cell 111:733–745. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mertens P. 2004. The dsRNA viruses. Virus Res 101:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar CS, Dey D, Ghosh S, Banerjee M. 2018. Breach: host membrane penetration and entry by nonenveloped viruses. Trends Microbiol 26:525–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder AJ, Wang JC, Danthi P. 2018. Components of the reovirus capsid differentially contribute to stability. J Virol 93:e01894-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01894-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liemann S, Chandran K, Baker TS, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. 2002. Structure of the reovirus membrane-penetration protein, Mu1, in a complex with is protector protein, Sigma3. Cell 108:283–295. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandran K, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML. 2002. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein micro 1 mediates membrane disruption. J Virol 76:9920–9933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9920-9933.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Middleton JK, Severson TF, Chandran K, Gillian AL, Yin J, Nibert ML. 2002. Thermostability of reovirus disassembly intermediates (ISVPs) correlates with genetic, biochemical, and thermodynamic properties of major surface protein mu1. J Virol 76:1051–1061. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1051-1061.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drayna D, Fields BN. 1982. Genetic studies on the mechanism of chemical and physical inactivation of reovirus. J Gen Virol 63:149–159. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-63-1-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barton ES, Forrest JC, Connolly JL, Chappell JD, Liu Y, Schnell FJ, Nusrat A, Parkos CA, Dermody TS. 2001. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell 104:441–451. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell JA, Schelling P, Wetzel JD, Johnson EM, Forrest JC, Wilson GA, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA, Stehle T, Dermody TS. 2005. Junctional adhesion molecule a serves as a receptor for prototype and field-isolate strains of mammalian reovirus. J Virol 79:7967–7978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.7967-7978.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konopka-Anstadt JL, Mainou BA, Sutherland DM, Sekine Y, Strittmatter SM, Dermody TS. 2014. The Nogo receptor NgR1 mediates infection by mammalian reovirus. Cell Host Microbe 15:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gentsch JR, Pacitti AF. 1985. Effect of neuraminidase treatment of cells and effect of soluble glycoproteins on type 3 reovirus attachment to murine L cells. J Virol 56:356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paul RW, Choi AH, Lee PW. 1989. The alpha-anomeric form of sialic acid is the minimal receptor determinant recognized by reovirus. Virology 172:382–385. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reiss K, Stencel JE, Liu Y, Blaum BS, Reiter DM, Feizi T, Dermody TS, Stehle T. 2012. The GM2 glycan serves as a functional coreceptor for serotype 1 reovirus. PLoS Pathog 8:e1003078. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiter DM, Frierson JM, Halvorson EE, Kobayashi T, Dermody TS, Stehle T. 2011. Crystal structure of reovirus attachment protein sigma1 in complex with sialylated oligosaccharides. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002166. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borsa J, Morash BD, Sargent MD, Copps TP, Lievaart PA, Szekely JG. 1979. Two modes of entry of reovirus particles into L cells. J Gen Virol 45:161–170. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-45-1-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrlich M, Boll W, Van Oijen A, Hariharan R, Chandran K, Nibert ML, Kirchhausen T. 2004. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits. Cell 118:591–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulant S, Stanifer M, Kural C, Cureton DK, Massol R, Nibert ML, Kirchhausen T. 2013. Similar uptake but different trafficking and escape routes of reovirus virions and infectious subvirion particles imaged in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol Biol Cell 24:1196–1207. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-12-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz WL, Haj AK, Schiff LA. 2012. Reovirus uses multiple endocytic pathways for cell entry. J Virol 86:12665–12675. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01861-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maginnis MS, Forrest JC, Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Dickeson SK, Santoro SA, Zutter MM, Nemerow GR, Bergelson JM, Dermody TS. 2006. Beta1 integrin mediates internalization of mammalian reovirus. J Virol 80:2760–2770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2760-2770.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maginnis MS, Mainou BA, Derdowski A, Johnson EM, Zent R, Dermody TS. 2008. NPXY motifs in the beta1 integrin cytoplasmic tail are required for functional reovirus entry. J Virol 82:3181–3191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01612-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mainou BA, Dermody TS. 2011. Src kinase mediates productive endocytic sorting of reovirus during cell entry. J Virol 85:3203–3213. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02056-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mainou BA, Dermody TS. 2012. Transport to late endosomes is required for efficient reovirus infection. J Virol 86:8346–8358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00100-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mainou BA, Zamora PF, Ashbrook AW, Dorset DC, Kim KS, Dermody TS. 2013. Reovirus cell entry requires functional microtubules. mBio 4:e00405-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00405-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baer GS, Dermody TS. 1997. Mutations in reovirus outer-capsid protein sigma3 selected during persistent infections of L cells confer resistance to protease inhibitor E64. J Virol 71:4921–4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borsa J, Sargent MD, Lievaart PA, Copps TP. 1981. Reovirus: evidence for a second step in the intracellular uncoating and transcriptase activation process. Virology 111:191–200. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebert DH, Deussing J, Peters C, Dermody TS. 2002. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J Biol Chem 277:24609–24617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sturzenbecker LJ, Nibert M, Furlong D, Fields BN. 1987. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J Virol 61:2351–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverstein SC, Astell C, Levin DH, Schonberg M, Acs G. 1972. The mechanisms of reovirus uncoating and gene activation in vivo. Virology 47:797–806. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nibert ML, Fields BN. 1992. A carboxy-terminal fragment of protein mu 1/mu 1C is present in infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reoviruses and is proposed to have a role in penetration. J Virol 66:6408–6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borsa J, Copps TP, Sargent MD, Long DG, Chapman JD. 1973. New intermediate subviral particles in the in vitro uncoating of reovirus virions by chymotrypsin. J Virol 11:552–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joklik WK. 1972. Studies on the effect of chymotrypsin on reovirions. Virology 49:700–715. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang L, Chandran K, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. 2006. Reovirus mu1 structural rearrangements that mediate membrane penetration. J Virol 80:12367–12376. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01343-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nibert ML, Odegard AL, Agosto MA, Chandran K, Schiff LA. 2005. Putative autocleavage of reovirus mu1 protein in concert with outer-capsid disassembly and activation for membrane permeabilization. J Mol Biol 345:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Odegard AL, Chandran K, Zhang X, Parker JS, Baker TS, Nibert ML. 2004. Putative autocleavage of outer capsid protein micro1, allowing release of myristoylated peptide micro1N during particle uncoating, is critical for cell entry by reovirus. J Virol 78:8732–8745. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8732-8745.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agosto MA, Ivanovic T, Nibert ML. 2006. Mammalian reovirus, a nonfusogenic nonenveloped virus, forms size-selective pores in a model membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:16496–16501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605835103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ivanovic T, Agosto MA, Zhang L, Chandran K, Harrison SC, Nibert ML. 2008. Peptides released from reovirus outer capsid form membrane pores that recruit virus particles. EMBO J 27:1289–1298. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nibert ML, Schiff LA, Fields BN. 1991. Mammalian reoviruses contain a myristoylated structural protein. J Virol 65:1960–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snyder AJ, Danthi P. 2018. Cleavage of the C-terminal fragment of reovirus mu1 is required for optimal infectivity. J Virol 92:e01848-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01848-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Agosto MA, Ivanovic T, King DS, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. 2009. Requirements for the formation of membrane pores by the reovirus myristoylated micro1N peptide. J Virol 83:7004–7014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00377-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drayna D, Fields BN. 1982. Biochemical studies on the mechanism of chemical and physical inactivation of reovirus. J Gen Virol 63:161–170. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-63-1-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agosto MA, Middleton JK, Freimont EC, Yin J, Nibert ML. 2007. Thermolabilizing pseudoreversions in reovirus outer-capsid protein micro 1 rescue the entry defect conferred by a thermostabilizing mutation. J Virol 81:7400–7409. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02720-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hooper JW, Fields BN. 1996. Role of the mu 1 protein in reovirus stability and capacity to cause chromium release from host cells. J Virol 70:459–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Middleton JK, Agosto MA, Severson TF, Yin J, Nibert ML. 2007. Thermostabilizing mutations in reovirus outer-capsid protein mu1 selected by heat inactivation of infectious subvirion particles. Virology 361:412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wessner DR, Fields BN. 1993. Isolation and genetic characterization of ethanol-resistant reovirus mutants. J Virol 67:2442–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wetzel JD, Wilson GJ, Baer GS, Dunnigan LR, Wright JP, Tang DS, Dermody TS. 1997. Reovirus variants selected during persistent infections of L cells contain mutations in the viral S1 and S4 genes and are altered in viral disassembly. J Virol 71:1362–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doyle JD, Danthi P, Kendall EA, Ooms LS, Wetzel JD, Dermody TS. 2012. Molecular determinants of proteolytic disassembly of the reovirus outer capsid. J Biol Chem 287:8029–8038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Snyder AJ, Danthi P. 2019. Selection and characterization of a reovirus mutant with improved thermostability. bioRxiv 10.1101/511352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Jane-Valbuena J, Breun LA, Schiff LA, Nibert ML. 2002. Sites and determinants of early cleavages in the proteolytic processing pathway of reovirus surface protein sigma3. J Virol 76:5184–5197. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.5184-5197.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jane-Valbuena J, Nibert ML, Spencer SM, Walker SB, Baker TS, Chen Y, Centonze VE, Schiff LA. 1999. Reovirus virion-like particles obtained by recoating infectious subvirion particles with baculovirus-expressed sigma3 protein: an approach for analyzing sigma3 functions during virus entry. J Virol 73:2963–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rawlings ND, Salvesen G. 2013. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes, 3rd ed Elsevier/AP, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thete D, Danthi P. 2018. Protein mismatches caused by reassortment influence functions of the reovirus capsid. J Virol 92:e00858-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00858-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thete D, Snyder AJ, Mainou BA, Danthi P. 2016. Reovirus mu1 protein affects infectivity by altering virus-receptor interactions. J Virol 90:10951–10962. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01843-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ooms LS, Kobayashi T, Dermody TS, Chappell JD. 2010. A post-entry step in the mammalian orthoreovirus replication cycle is a determinant of cell tropism. J Biol Chem 285:41604–41613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Antczak JB, Joklik WK. 1992. Reovirus genome segment assortment into progeny genomes studied by the use of monoclonal antibodies directed against reovirus proteins. Virology 187:760–776. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Danis C, Garzon S, Lemay G. 1992. Further characterization of the ts453 mutant of mammalian orthoreovirus serotype 3 and nucleotide sequence of the mutated S4 gene. Virology 190:494–498. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91241-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mabrouk T, Lemay G. 1994. The sequence similarity of reovirus sigma 3 protein to picornaviral proteases is unrelated to its role in mu 1 viral protein cleavage. Virology 202:615–620. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morgan EM, Zweerink HJ. 1974. Reovirus morphogenesis. Corelike particles in cells infected at 39 degrees with wild-type reovirus and temperature-sensitive mutants of groups B and G. Virology 59:556–565. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roner MR, Lin PN, Nepluev I, Kong LJ, Joklik WK. 1995. Identification of signals required for the insertion of heterologous genome segments into the reovirus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:12362–12366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shing M, Coombs KM. 1996. Assembly of the reovirus outer capsid requires mu 1/sigma 3 interactions which are prevented by misfolded sigma 3 protein in temperature-sensitive mutant tsG453. Virus Res 46:19–29. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(96)01372-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharpe AH, Fields BN. 1982. Reovirus inhibition of cellular RNA and protein synthesis: role of the S4 gene. Virology 122:381–391. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Denzler KL, Jacobs BL. 1994. Site-directed mutagenic analysis of reovirus sigma 3 protein binding to dsRNA. Virology 204:190–199. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yue Z, Shatkin AJ. 1997. Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) is regulated by reovirus structural proteins. Virology 234:364–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmechel S, Chute M, Skinner P, Anderson R, Schiff L. 1997. Preferential translation of reovirus mRNA by a sigma3-dependent mechanism. Virology 232:62–73. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Berard A, Coombs KM. 2009. Mammalian reoviruses: propagation, quantification, and storage. Curr Protoc Microbiol Chapter 15:Unit15C.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kobayashi T, Ooms LS, Ikizler M, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. 2010. An improved reverse genetics system for mammalian orthoreoviruses. Virology 398:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mendez II, Hermann LL, Hazelton PR, Coombs KM. 2000. A comparative analysis of freon substitutes in the purification of reovirus and calicivirus. J Virol Methods 90:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(00)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith RE, Zweerink HJ, Joklik WK. 1969. Polypeptide components of virions, top component and cores of reovirus type 3. Virology 39:791–810. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coombs KM. 1998. Stoichiometry of reovirus structural proteins in virus, ISVP, and core particles. Virology 243:218–228. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]