Abstract

Background

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is an important therapy for patients with end‐stage kidney disease and is used in more than 200,000 such patients globally. However, its value is often limited by the development of infections such as peritonitis and exit‐site and tunnel infections. Multiple strategies have been developed to reduce the risk of peritonitis including antibiotics, topical disinfectants to the exit site and antifungal agents. However, the effectiveness of these strategies has been variable and are based on a small number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The optimal preventive strategies to reduce the occurrence of peritonitis remain unclear.

This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2004.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of antimicrobial strategies used to prevent peritonitis in PD patients.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's Specialised Register to 4 October 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies specifically designed for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE; handsearching conference proceedings; and searching the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

RCTs or quasi‐RCTs in patients receiving chronic PD, which evaluated any antimicrobial agents used systemically or locally to prevent peritonitis or exit‐site/tunnel infection were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed risk of bias and extracted data. Summary estimates of effect were obtained using a random‐effects model, and results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

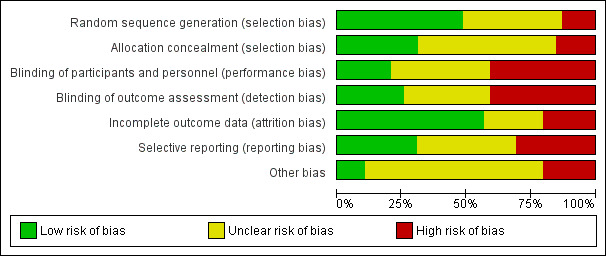

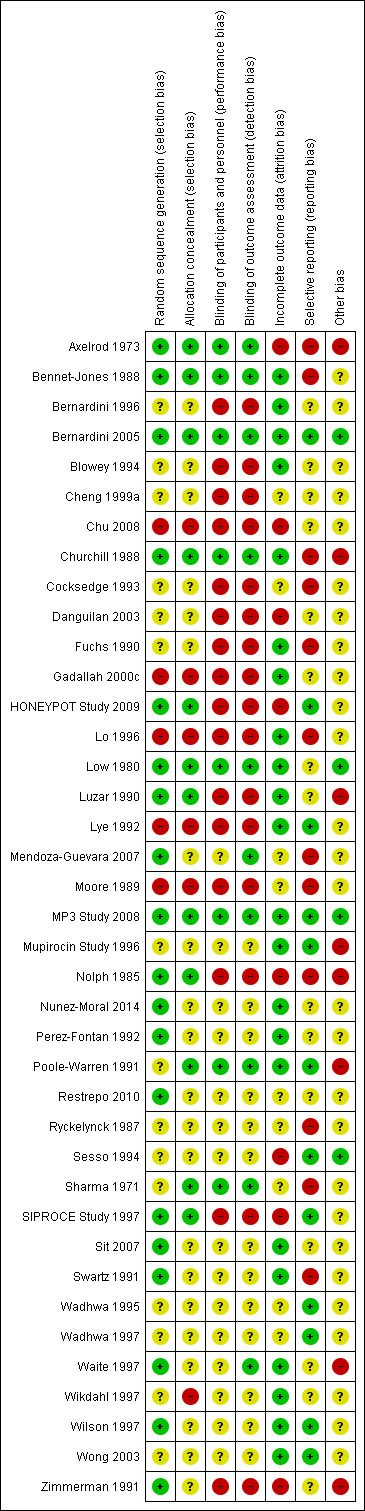

Thirty‐nine studies, randomising 4435 patients, were included. Twenty additional studies have been included in this update. The risk of bias domains were often unclear or high; risk of bias was judged to be low in 19 (49%) studies for random sequence generation, 12 (31%) studies for allocation concealment, 22 (56%) studies for incomplete outcome reporting, and in 12 (31%) studies for selective outcome reporting. Blinding of participants and personnel was considered to be at low risk of bias in 8 (21%) and 10 studies (26%) for blinding of outcome assessors. It should be noted that blinding of participants and personnel was not possible in many of the studies because of the nature of the intervention or control treatment.

The use of oral or topical antibiotic compared with placebo/no treatment, had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection (3 studies, 191 patients, low quality evidence: RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.04) and the risk of peritonitis (5 studies, 395 patients, low quality evidence: RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.19).

The use of nasal antibiotic compared with placebo/no treatment had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection (3 studies, 338 patients, low quality evidence: RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.62 to 2.87) and the risk of peritonitis (3 studies, 338 patients, low quality evidence: RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.31).

Pre/perioperative intravenous vancomycin compared with no treatment may reduce the risk of early peritonitis (1 study, 177 patients, low quality evidence: RR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.61) but has an uncertain effect on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection (1 study, 177 patients, low quality evidence: RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.32).

The use of topical disinfectant compared with standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant) had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection (8 studies, 973 patients, low quality evidence, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.33) and the risk of peritonitis (6 studies, 853 patients, low quality evidence: RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.06).

Antifungal prophylaxis with oral nystatin/fluconazole compared with placebo/no treatment may reduce the risk of fungal peritonitis occurring after a patient has had an antibiotic course (2 studies, 817 patients, low quality evidence: RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.63).

No intervention reduced the risk of catheter removal or replacement. Most of the available studies were small and of suboptimal quality. Only six studies enrolled 200 or more patients.

Authors' conclusions

In this update, we identified limited data from RCTs and quasi‐RCTs which evaluated strategies to prevent peritonitis and exit‐site/tunnel infections. This review demonstrates that pre/peri‐operative intravenous vancomycin may reduce the risk of early peritonitis and that antifungal prophylaxis with oral nystatin or fluconazole reduces the risk of fungal peritonitis following an antibiotic course. However, no other antimicrobial interventions have proven efficacy. In particular, the use of nasal antibiotic to eradicate Staphylococcus aureus, had an uncertain effect on the risk of peritonitis and raises questions about the usefulness of this approach. Given the large number of patients on PD and the importance of peritonitis, the lack of adequately powered and high quality RCTs to inform decision making about strategies to prevent peritonitis is striking.

Plain language summary

Antimicrobial agents for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients

What is the Issue?

People with kidney failure may be treated with peritoneal dialysis where a catheter is permanently inserted into the peritoneum (lining around abdominal contents) through the abdominal wall and sterile fluid is drained in and out a few times each day. The most common serious complication is infection of the peritoneum, which is called peritonitis. This may be caused by bacteria accidentally being transferred from the catheter.

What did we do?

We searched the literature up until 4 October 2016 and identified 39 studies randomising 4435 patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis that were evaluated in this review.

What did we find?

We found that antibiotics given when a peritoneal dialysis catheter is implanted may reduce the risk of early peritonitis but not of exit‐site/tunnel infection. Antifungal prophylaxis with oral nystatin or fluconazole reduces the risk of fungal peritonitis following an antibiotic course. The available studies are of low quality evidence and consequently, it is uncertain if there is any benefit from using nasal mupirocin or topical disinfectants or other interventions to reduce exit‐site/tunnel infection or peritonitis.

Summary of findings

Background

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is one of the renal replacement therapies available to people with end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD). There is considerable variation in its use from country to country, with the proportion of total dialysis patients on PD in developed countries ranging from 3.3% (Japan), to 7.0% (USA), 8.3% (Greece), 17.0 % (UK), 36.3% (New Zealand), and up to 79.4% (Hong Kong) (Jain 2012). Because PD and haemodialysis have similar outcomes and patients feel that PD, compared with HD, allows them to live life more fully (Morton 2011), PD should be used more frequently than it is but the perceived risk of peritonitis may prevent this from occurring (Heaf 2004; Piraino 1998).

Description of the condition

Peritonitis due to various organisms(e.g.Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, coagulase‐negative staphylococci) is a leading complication of PD resulting in technique failure (Woodrow 1997), hospitalisation (Choi 2004; Churchill 1997), peritoneal membrane failure, switching to haemodialysis (Jaar 2009; Piraino 1989) and increased mortality (Annigeri 2001; Digenis 1990; Fried 1996; Piraino 2000). There has been a dramatic reduction in the rates of peritonitis from the start of continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD), but rates above the minimum acceptable peritonitis rate recommended by the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) of one episode every 33 months (0.36 episodes/year at risk) are still common (Piraino 2011).

Risk factors for peritonitis include older age (Nessim 2009; Oxton 1994; Salusky 1997), depression (Troidle 2003), coexisting diseases such as diabetes (Chow 2005; Ghali 2011) and cardiovascular disease (McDonald 2004; Nolph 1987), obesity (McDonald 2004), connection methodology (Daly 2001), presence of a peritoneal catheter exit‐site infection (Lloyd 2013; van Diepen 2012), and the presence of nasal carriage of S. aureus (Golper 1996; Mupirocin Study 1996; Perez‐Fontan 1993; Schaefer 2003). Race is also an independent risk factor, with African‐American, native Canadian and indigenous Australian Aborigines on PD being shown to be at increased risk (Farias 1994; Fine 1994; Golper 1996; Holley 1993; Lim 2005).

Description of the intervention

Different antimicrobial interventions are used at PD catheter insertion and on an ongoing basis to prevent peritonitis. These include intravenous antibiotics, oral antibiotics, topical antibiotics (Thodis 2000), topical disinfectants, prophylactic treatment of S. aureus nasal carriage primarily with intranasal antibiotic ointment (Piraino 2002), different exit‐site dressing systems and antifungal prophylaxis. All of these strategies, particularly the use of antibiotic at catheter insertion and the cleansing and disinfection of the exit‐site, are widely accepted, but practice patterns are variable and it is not clear which practices have most benefit (Piraino 2011; Van Biesen 2014). Studies on preventing PD‐related infections are limited in number and quality (Piraino 2011). International guidelines differ in their recommendations on preventing PD‐related infections, with some countries not having relevant guidelines (Table 5).

1. Guidelines on antimicrobial interventions to prevent peritonitis in PD.

| Guideline | Country | Year | Recommendation |

| Kidney‐Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative | United States of America | NA | No guideline |

| The Renal Association | United Kingdom | April 2008 July 2010 |

Guideline 3.1 ‐ PD Access: Implantation Protocol

Guideline 5.1.4 ‐ PD Infectious Complications: Prevention Strategies

Guideline 5.1.5 ‐ PD Infectious Complications: Prevention Strategies

Guideline 5.1.6 ‐ PD Infectious Complications: Prevention Strategies

|

| Canadian Society of Nephrology | Canada | NA | No guideline |

| European Renal Best Practice | Europe | NA | No guideline |

| International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis | NA | July 2010 November 2011 |

Guideline 3.1: Implantation Protocol (1A)

Position Statement: Catheter Placement to Prevent Catheter Infections and the Related Peritonitis Episodes

Position Statement: Exit‐Site Care to Prevent Peritonitis

Position Statement: Prevention of Fungal Peritonitis

|

| Kidney Health Australia‐Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment | Australia/ New Zealand | February 2014 |

Guideline 6. Prophylactic Antibiotics for Insertion of PD Catheters

Guideline 8. Treatment of Peritoneal Dialysis‐Associated Fungal Peritonitis

Guideline 10. Prophylaxis for Exit‐site/Tunnel Infections Using Mupirocin

|

MRSA ‐ methicillin‐resistant S. aureus; NA ‐ not applicable; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis

None of these interventions are free of risks or without cost. Antibiotic prophylaxis carries the risk of gastrointestinal toxicity and may be a cause of antibiotic resistance (Annigeri 2001; Bernardini 1996); it may also be ineffective when patients already have resistance to some antibiotics. Care should be taken that any disinfectant used is at a concentration that is non‐cytotoxic (Piraino 2011).

How the intervention might work

For a patient to be able to successfully use PD as a dialysis therapy, PD‐related infections (exit‐site infections, tunnel infections and peritonitis) need to be avoided. The most important infection is peritonitis and a number of prophylactic strategies have been employed to limit its occurrence. Bacteria are known to be able to gain entry to the peritoneum in a variety of ways and hence, various strategies have been used to prevent this occurring (Campbell 2015).

Oral antibiotics

Oral antibiotics such as rifampin have been given as prophylaxis to PD patients to reduce catheter infections and peritonitis due to S. aureus (Bernardini 1996; Zimmerman 1991). This organism is a major cause of PD catheter infections which can result in S. aureus peritonitis and catheter removal. S. aureus nasal carriage is known to be a significant risk factor for S. aureus PD‐related infections (Bernardini 1996). Cyclic oral rifampin is superior to placebo in preventing S. aureus infections. Other oral antibiotics used include ofloxacin (Sesso 1994), cephalexin (Low 1980), and trimethoprim/sulphamethoxazole (Churchill 1988).

Topical antibiotics

Topical antibiotics such as mupirocin have been applied to the exit site once daily because this antibiotic has good activity against gram‐positive organisms such as staphylococci and streptococci, which are a common cause of exit‐site infection and peritonitis in PD patients (Keane 2000; Troidle 1998; Ward 1986). However, mupirocin is less active against most gram‐negative bacilli and anaerobes (Sutherland 1985). Sodium fusidate ointment (2%) has also been applied to the exit site at one‐month intervals and is known to have activity against staphylococci (Sesso 1994). Gentamicin cream is active against both gram‐positive and gram‐negative organisms and has been used long term on a once‐daily basis at the exit site as prophylaxis for exit‐site infection (Bernardini 2005; Chu 2008). Gentamicin is active against both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, two important causes of exit‐site infection (Bernardini 2005). Polysporin triple ointment (P3) consists of bacitracin/gramicidin/polymyxin and has bacteriostatic activity against a wide range of skin flora and other organisms including gram‐negative bacteria (MP3 Study 2008).

Nasal antibiotic prophylaxis

Various antibiotic treatments have been trialled in attempts to eliminate S. aureus nasal carriage in PD patients. The nasal carriage of S. aureus is a well‐recognised risk factor for the development of S. aureus infections in CAPD patients (Davies 1989; Luzar 1990; Piraino 1990). Neomycin sulphate ointment has been used prophylactically. Mupirocin has also been used to eliminate nasal S. aureus. While mupirocin is effective at reducing S. aureus nasal carriage rates, re‐colonisation frequently occurs. Sodium fusidate ointment (2%) has also been used and is effective at reducing S. aureus nasal carriage rates (Sesso 1994).

Pre/peri‐operative intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis

The administration of intravenous antibiotics at catheter insertion has been trialled in order to determine if this practice reduces the risk of post‐operative peritonitis or exit‐site infection after PD catheter insertion. Although the insertion of a PD catheter involves "clean surgery involving the placement of a prosthesis or implant", there is the potential for contamination of the peritoneum with micro‐organisms from the patient's own body during surgery. Hence, the giving of a single dose of antibiotic prophylaxis intravenously on starting anaesthesia is recommended (Collier 2008).

Topical disinfectants of the exit site

Topical disinfectants have been applied to the exit site for many years, in an attempt to reduce the bacterial load around the exit site. It has been shown that PD patients with a history of an exit‐site infection have twice the risk of experiencing a peritonitis episode (Canadian CAPD Clinical Trials Group 1989) so it is important to keep the exit‐site infection‐free. Povidone iodine ointment is a broad spectrum antiseptic ointment that has been used and has minimal adverse events associated with its use (Waite 1997). Povidone iodine solution (20g/L) has also been used and shown to successfully reduce the number of exit‐site infections (Luzar 1990). Other antiseptic agents such as hydrogen peroxide, sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine have been used (Piraino 2011). The daily use of antibacterial honey at the exit site was trialled in the HONEYPOT Study 2009 This agent was used because it does not induce antimicrobial resistance and has been shown to be active against a broad range of bacteria and fungi (Cho 2014).

Dressing systems for exit sites

A number of exit‐site dressing systems have been devised, all with the aim of reducing exit‐site/tunnel infection and any subsequent peritonitis. The agents used include topical disinfectants and different dressing types and require more or less frequent removal. More frequent removal is seen to risk damaging the skin around the exit site and less frequent removal is felt to possibly encourage the growth of anaerobes. The concentration of topical disinfectants used need to be at non‐cytotoxic levels.

Silver ring system on catheter

The addition of a silver ring device mounted onto the PD catheter was trialled by German researchers in the 1990s (SIPROCE Study 1997). The silver ring was used because of the antimicrobial properties of silver. The use of silver‐coated catheters in animals had shown a reduction in infectious events (Dasgupta 1994; Fung 1996) and offered a non‐pharmaceutical approach to reducing PD catheter‐related infections.

Antistaphylococcal vaccine

An antistaphylococcal vaccine was trialled in the 1990s for the purpose of immunising patients with an anti‐staphylococcal agent. The expectation was that the vaccine would promote a significant increase in the dialysate level of specific antibodies against S. aureus and that this would lead to reduced peritonitis and exit‐site/tunnel infection rates (Poole‐Warren 1991).

Antifungal agents

Antifungal prophylaxis to prevent fungal peritonitis when a PD patient receives an antibiotic course is based on the fact that most episodes of fungal peritonitis are preceded by courses of antibiotics (Piraino 2011). Patients receiving prolonged or repeated antibiotic courses are at increased risk of fungal peritonitis, mostly due to Candida spp. The co‐administration of an oral antifungal agent with an antibiotic course has been trialled to determine if this practice reduces the risk of fungal peritonitis (Lo 1996; Restrepo 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

The aim of this update was to include any new studies of antimicrobial interventions designed to prevent peritonitis in PD patients that have been published since the original review was published in 2004. We also aim to provide a critical appraisal of the current available evidence. As peritonitis is a significant problem for patients using PD, frequently leading to morbidity and technique failure and sometimes to mortality, we have updated the review.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of antimicrobial strategies used to prevent peritonitis in PD patients.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (studies in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) in which antimicrobial interventions designed to prevent peritonitis were compared in patients on PD.

Types of participants

We included adults and children with ESKD who were undergoing PD treatment.

Types of interventions

We included studies involving the use of any antimicrobial agent, whether the interventions were tested between themselves (head‐to‐head) or against placebo/no treatment. The inclusion criteria have been expanded in this update, with the intervention "oral antibiotics" becoming "oral or topical or intraperitoneal antibiotics" and with the interventions "dressing systems for exit sites" and "silver ring system on catheter" being added.

Specifically, the following antimicrobial interventions were analysed.

Oral or topical or intraperitoneal antibiotics

Nasal antibiotic prophylaxis (mupirocin, rifampicin, other)

Pre/peri‐operative intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis

Topical disinfectants of the exit‐site (povidone‐iodine, chlorhexidine, triclosan, soap and water, other)

Germicidal systems for connection devices

Dressing systems for exit sites

Silver ring system on catheter

Antistaphylococcal vaccine

Antifungal agents

Types of outcome measures

Peritonitis‐number of patients with peritonitis and peritonitis rate (peritonitis defined as dialysate count of > 100 cells/mm3 with > 50% being polymorphonuclear leukocytes; peritonitis rate defined as number of episodes of peritonitis over total patient months on PD)

Peritonitis relapse (reoccurrence of peritonitis due to the same organism within two to four weeks)

Death due to peritonitis

All‐cause mortality

Exit‐site and tunnel infection‐number of patients with exit‐site and tunnel infections and exit‐site and tunnel infection rate

Catheter removal/catheter replacement

Technique failure (transfer from PD to haemodialysis/transplant due to peritonitis)

Toxicity of antimicrobial treatments (nasal irritation, sneezing, generalised pruritus, headache, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, local irritation, rash)

Time to first peritonitis episode

Primary outcomes

Peritonitis

Exit‐site infection/tunnel infection

Catheter removal/catheter replacement

Secondary outcomes

Peritonitis relapse

Death due to peritonitis

All‐cause mortality

Technique failure

Toxicity of antimicrobial treatments

Time to first peritonitis episode

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register to 4 October 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials CENTRAL

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals & the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal & ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that were potentially relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable. However, studies and reviews that might include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts and where necessary, the full text of these studies, to determine which satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction and assessment of the risk of bias were performed independently by the same authors using standardised data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions, these data were used. Any discrepancy between published versions was highlighted. Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were assessed using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (peritonitis (number), peritonitis (rate), death due to peritonitis, all‐cause mortality, exit‐site/tunnel infection (number), exit‐site/tunnel infection (rate), catheter removal/replacement, technique failure, toxicity of antimicrobial treatments) results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). No continuous outcomes were identified.

Unit of analysis issues

Where data on the number of subjects with events (e.g. number of subjects with one or more episodes of peritonitis) were available, the RR was calculated as the ratio of the incidence of the event (one or more episodes) in the experimental treatment group over the incidence in the control group. Where data on the number of episodes were available the RR was calculated as the ratio of the rate of the outcome (e.g. the peritonitis rate) in the experimental treatment group (given by number of episodes of the outcome over total patient months on PD) over the rate in the control group.

Dealing with missing data

Where necessary, we contacted triallists to request missing patient data due to loss to follow‐up and exclusion from study analyses in an effort to conduct intention‐to‐treat analyses. With the update, four authors responded to our requests. Where missing dichotomous data were few, and unlikely to affect the overall results, we analysed available data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

The search strategy included searching major databases, conference proceedings and prospective trial registers without language restriction in an attempt to reduce publication bias related to failure of authors to publish negative results or inability to publish negative results in journals indexed in major databases. Insufficient studies were available to assess for publication bias using funnel plots. Where multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were included from the most recent publication, and preferably, the definitive publication. However, all publications were reviewed to identify outcomes not reported in the index publication in an attempt to reduce outcome reporting bias.

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model for dichotomous data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was planned to explore potential sources of variability in observed treatment effect where possible (paediatric versus adult population, diabetic versus non‐diabetic, time on PD before beginning of antimicrobial treatment). However, no subgroup analyses were performed due to lack of available data from the included studies.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was planned to investigate the effect of year of study and study performance. However, there were insufficient studies to do this.

Summarising and interpreting results

We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of evidence for each of the key outcomes (Guyatt 2008). We used the GRADE profiler to create 'Summary of Findings' tables (Schünemann 2011a).

For assessments of the overall quality of evidence for each outcome that included pooled data from RCTs, we downgraded the evidence from 'high quality' by one level for serious study limitations and by two levels for very serious study limitations. The evidence was appraised using the five GRADE considerations: risk of bias, imprecision of effect estimates, inconsistency, indirectness and potential publication bias. None were upgraded to moderate or high quality as most pooled estimates did not reveal a large magnitude of effect, there was potential for impact by confounders, and most did not show a strong dose‐response gradient (Schünemann 2011b). The exception was the pooled estimate obtained for the comparison of the use of an antifungal agent versus placebo/no treatment for preventing fungal peritonitis, but the evidence was not upgraded from 'low' because only two studies contributed data for the outcome of fungal peritonitis and one of the studies had a high risk of bias. We used these assessments and the evidence for absolute benefit or harm of the interventions and the sum of available data on all important outcomes from each study included for each comparison, to arrive at conclusions about the effectiveness of antimicrobial agents at preventing catheter‐related infection or the need for catheter removal/replacement in PD patients.

'Summary of Findings' tables consisted of the following clinically important outcomes identified in the selected studies:

Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes)

Exit‐site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes)

Catheter removal or replacement (number of patients)

Fungal peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

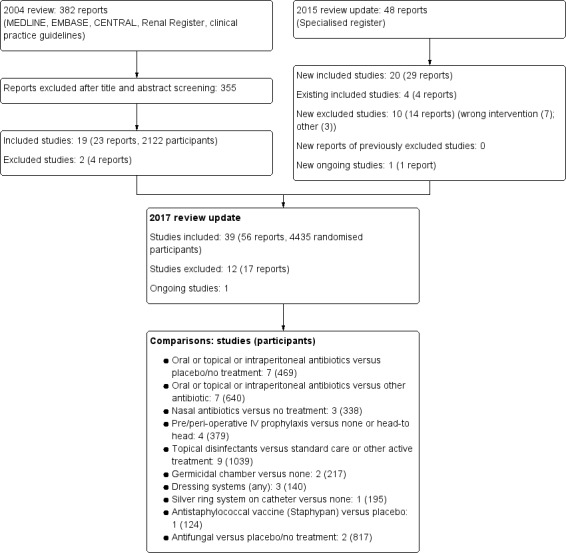

For this update we searched the Specialised Register to 4 October 2016 and identified 48 new reports. After full‐text assessment 31 new studies were identified. Twenty new studies (33 reports) were included, 10 were excluded (14 reports), and one ongoing study was identified. We also identified four new reports of four existing included studies. Search results are shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 39 studies in the review, 19 of which had been included in the original review. Of the 20 new studies, 10 had been published since the search was done for the previous review and 10 (Axelrod 1973; Cheng 1999a; Cocksedge 1993; Fuchs 1990; Moore 1989; Ryckelynck 1987; Sharma 1971; SIPROCE Study 1997; Wadhwa 1995; Wadhwa 1997) had not been identified in the previous search. There was one four‐arm study (Swartz 1991), three three‐arm studies (Fuchs 1990; Gadallah 2000c; Sesso 1994), and the remaining studies were two‐arm studies. No cross‐over studies were identified.

Of the 39 studies included (4435 randomised participants), all were parallel group studies. All participants were chronic PD patients treated in‐centre or in satellite facilities. Two studies (Axelrod 1973; Sharma 1971) reported the number of dialyses but not the number of participants in each group and hence, the data from these studies could not be added to the meta‐analyses. Most studies included only adult patients; two studies (Blowey 1994; Mendoza‐Guevara 2007) included only children and young adults on PD. Twenty‐six studies (Bernardini 2005; Bernardini 1996; Chu 2008; Cocksedge 1993; Fuchs 1990; Gadallah 2000c; HONEYPOT Study 2009; Lo 1996; Luzar 1990; Lye 1992; MP3 Study 2008; Mupirocin Study 1996; Nolph 1985; Nunez‐Moral 2014; Perez‐Fontan 1992; Poole‐Warren 1991; Restrepo 2010; Sesso 1994; SIPROCE Study 1997; Swartz 1991; Wadhwa 1995; Wadhwa 1997; Waite 1997; Wikdahl 1997; Wong 2003; Zimmerman 1991) identified the proportion of patients who had diabetes mellitus.

Most studies reported only some of the primary outcomes of interest to this review. The primary outcomes reported in the studies were as follows: peritonitis ‐ number of patients (22 studies), peritonitis rate (14 studies), exit‐site/tunnel infection ‐ number of patients (22 studies), exit‐site/tunnel infection ‐ rate (12 studies) and catheter removal/replacement (15 studies). Other outcomes reported included death due to peritonitis (2 studies), all‐cause mortality (13 studies), technique failure (3 studies) and toxicity of antimicrobial treatments (5 studies). No studies had data on peritonitis relapse and only two had time to first peritonitis episode (HONEYPOT Study 2009; MP3 Study 2008).

Three study authors responded to queries about study methods and/or requests for additional unpublished information (Chu 2008; Danguilan 2003; HONEYPOT Study 2009).

Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment

In seven studies (469 participants), patients were randomised to oral, or topical (exit site, nasal) or intraperitoneal prophylactic antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment (Blowey 1994; Churchill 1988; Low 1980; Sesso 1994; Swartz 1991; Wong 2003; Zimmerman 1991). The duration of follow‐up ranged from one to 12 months.

Oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic

Seven studies (640 participants) randomised patients to oral, or topical (exit site, nasal) or intraperitoneal antibiotics versus other antibiotics (Bernardini 1996; Bernardini 2005; Chu 2008; Danguilan 2003; MP3 Study 2008; Perez‐Fontan 1992; Sesso 1994) with follow‐up ranging from 7.8 to 18 months.

Nasal antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo/no treatment

Three studies (338 participants) compared the use of nasal prophylactic antibiotics with placebo (Mupirocin Study 1996; Sesso 1994; Sit 2007). The duration of follow‐up ranged from 7.8 to 18 months.

Pre/peri‐operative antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo/no treatment or other antibiotic

One study (178 participants) assessed the use of vancomycin with cefazolin as perioperative intravenous prophylaxis head‐to‐head (Gadallah 2000c), and four studies (379 patients) compared the use of perioperative intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis against no antibiotic treatment (Bennet‐Jones 1988; Gadallah 2000c; Lye 1992; Wikdahl 1997). Follow‐up periods ranged from 10 to 28 days.

Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant)

Nine studies (1039 participants) evaluated the effect of topical disinfectants versus standard care or other intervention at the exit site on a range of outcomes (Cheng 1999a; HONEYPOT Study 2009; Luzar 1990; Mendoza‐Guevara 2007; Nunez‐Moral 2014; Wadhwa 1995; Wadhwa 1997; Waite 1997; Wilson 1997). The duration of follow‐up ranged from 6 to 24 months.

Other interventions

Other interventions included one study (167 participants) which compared the use of an ultraviolet germicidal chamber to disinfect the spike and the solution bag outlet port versus no treatment (Nolph 1985) while another study (50 participants) directed one group to soak their connectors in antiseptic before performing a bag exchange while the control group did not use antiseptic (Ryckelynck 1987). Three studies (140 participants) compared different dressing systems (Cocksedge 1993; Fuchs 1990; Moore 1989) and one study (195 participants) compared the addition of a silver ring device on the catheter versus no ring (SIPROCE Study 1997). One study (124 participants) compared the antistaphylococcal vaccine Staphypan Berna against placebo (Poole‐Warren 1991).

Antifungal prophylaxis versus placebo/no treatment interventions

Two studies (817 participants) compared the administration of an antifungal agent with an antibiotic course against no treatment (Lo 1996; Restrepo 2010). Follow‐up periods ranged from 1 to 18 months.

See Table 6 for comparisons included in Strippoli 2004a and this 2017 update.

2. Comparisons in original review and updated review.

| Comparisons in 2004 review | Comparisons in 2017 review |

| Oral antibiotics versus none | Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment |

| Nasal antibiotics versus none | Oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic |

| Peri‐operative IV prophylaxis versus none | Nasal antibiotics versus no treatment |

| Peri‐operative IV prophylaxis head‐to‐head | Pre/peri‐operative IV prophylaxis versus none or head‐to‐head |

| Topical disinfectants versus none | Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant) |

| Germicidal chamber versus none | Germicidal chamber versus none |

| Antistaphylococcal vaccine (Staphypan) versus placebo | Dressing systems (any) |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis head‐to‐head agents | Silver ring system on catheter versus none |

| ‐‐ | Antistaphylococcal vaccine (Staphypan) versus placebo |

| ‐‐ | Antifungal versus placebo/no treatment |

Excluded studies

Twelve studies (17 reports) were excluded after full text review. The characteristics of the excluded studies are shown in "Characteristics of excluded studies". Reasons for excluding studies included focus of study was about treatment of PD‐related infection not prevention, report was of a pharmacokinetics study, agent used in intervention was not an antimicrobial, and PD‐related infection data was not readily available in the published report.

Risk of bias in included studies

The assessment of risk of bias is shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Figure 2 shows relative proportional rankings of studies for each risk of bias indicator. Figure 3 shows the risk of bias items for individual studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomisation of sequence generation was judged to be at low risk of bias in 19 studies (Axelrod 1973; Bennet‐Jones 1988; Bernardini 2005; Churchill 1988; HONEYPOT Study 2009; Low 1980; Luzar 1990; Mendoza‐Guevara 2007; MP3 Study 2008; Nolph 1985; Nunez‐Moral 2014; Perez‐Fontan 1992; Restrepo 2010; SIPROCE Study 1997; Sit 2007; Swartz 1991; Waite 1997; Wilson 1997; Zimmerman 1991). Randomisation method was unclear in 15 studies and was judged to be at high risk of bias in five studies (Chu 2008; Gadallah 2000c; Lo 1996; Lye 1992; Moore 1989).

Twelve studies reported allocation concealment adequately (Axelrod 1973; Bennet‐Jones 1988; Bernardini 2005; Churchill 1988; HONEYPOT Study 2009; Low 1980; Luzar 1990; MP3 Study 2008; Nolph 1985; Poole‐Warren 1991; Sharma 1971; SIPROCE Study 1997). Allocation concealment was unclear in 21 studies and six studies were judged to be at high risk of bias (Chu 2008; Gadallah 2000c; Lo 1996; Lye 1992; Moore 1989; Wikdahl 1997).

Blinding

Performance bias (blinding of participants and investigators) was judged to be at low risk of bias in eight studies (Axelrod 1973; Bennet‐Jones 1988; Bernardini 2005; Churchill 1988; Low 1980; MP3 Study 2008; Poole‐Warren 1991; Sharma 1971), was unclear in 15 studies, and was judged to be a high risk of bias in 16 studies (Bernardini 1996; Blowey 1994; Cheng 1999a; Chu 2008; Cocksedge 1993; Danguilan 2003; Fuchs 1990; Gadallah 2000c; HONEYPOT Study 2009; Lo 1996; Luzar 1990; Lye 1992; Moore 1989; Nolph 1985; SIPROCE Study 1997; Zimmerman 1991).

Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors) was judged to be at low risk of bias in 10 studies (Axelrod 1973; Bennet‐Jones 1988; Bernardini 2005; Churchill 1988; Low 1980; Mendoza‐Guevara 2007; MP3 Study 2008; Poole‐Warren 1991; Sharma 1971; Waite 1997), was unclear in 13 studies, and was judged to be at high risk of bias in 16 studies (Bernardini 1996; Blowey 1994; Cheng 1999a; Chu 2008; Cocksedge 1993; Danguilan 2003; Fuchs 1990; Gadallah 2000c; HONEYPOT Study 2009; Lo 1996; Luzar 1990; Lye 1992; Moore 1989; Nolph 1985; SIPROCE Study 1997; Zimmerman 1991).

Incomplete outcome data

Outcomes data reporting was considered to be complete with a low risk of bias in 22 studies (Bennet‐Jones 1988; Bernardini 1996; Bernardini 2005; Blowey 1994; Churchill 1988; Fuchs 1990; Gadallah 2000c; Lo 1996; Low 1980; Luzar 1990; Lye 1992; MP3 Study 2008; Mupirocin Study 1996; Nunez‐Moral 2014; Perez‐Fontan 1992; Poole‐Warren 1991; Sit 2007; Swartz 1991; Waite 1997; Wikdahl 1997; Wilson 1997; Wong 2003). Eight studies (Axelrod 1973; Chu 2008; Danguilan 2003; HONEYPOT Study 2009; Nolph 1985; Sesso 1994; SIPROCE Study 1997; Zimmerman 1991) reported that from 9.2% to 77.7% of patients were excluded from analyses, so were considered to be at high risk of bias. The risk of bias was unclear in nine studies because there was insufficient information provided to determine if data from all patients who entered the study were included in the analysis.

Selective reporting

We identified 12 studies (Bernardini 2005; HONEYPOT Study 2009; Lye 1992; MP3 Study 2008; Mupirocin Study 1996; Poole‐Warren 1991; Sesso 1994; SIPROCE Study 1997; Wadhwa 1995; Wadhwa 1997; Wilson 1997; Wong 2003) and reported all outcomes based on the protocols described in the study methods and could be meta‐analysed. Twelve studies were judged to be at high risk of bias of reporting bias (Axelrod 1973; Bennet‐Jones 1988; Churchill 1988; Cocksedge 1993; Fuchs 1990; Lo 1996; Mendoza‐Guevara 2007; Moore 1989; Nolph 1985; Ryckelynck 1987; Sharma 1971; Swartz 1991) because only one our primary outcomes cold be meta‐analysed; two studies reported outcomes incompletely so they could not be included in any of our meta‐analyses (Axelrod 1973; Sharma 1971). Reporting bias was unclear for 15 studies because only two (of our three) primary outcomes were reported or could be meta‐analysed.

Other potential sources of bias

Eight studies (Axelrod 1973; Churchill 1988; Luzar 1990; Mupirocin Study 1996; Nolph 1985; Poole‐Warren 1991; SIPROCE Study 1997; Waite 1997; Zimmerman 1991) reported receiving monetary support from pharmaceutical companies; one study received combined funding from industry and government (HONEYPOT Study 2009) and was judged to at unclear risk of bias. Four studies were judged to be at low risk bias (Bernardini 2005; Low 1980; MP3 Study 2008; Sesso 1994) and the remaining 26 studies were judged unclear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oral or topical or intraperitoneal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients.

| Oral or topical or intraperitoneal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with CKD on peritoneal dialysis Settings: tertiary settings Intervention: oral or topical or intraperitoneal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Oral or topical or intraperitoneal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment | |||||

| Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes) | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.57 to 1.19) | 395 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 360 per 1000 | 295 per 1000 (205 to 428) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 385 per 1000 | 316 per 1000 (219 to 458) | |||||

| Exit‐site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes) | Study population | RR 0.45 (0.19 to 1.04) | 191 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | ||

| 176 per 1000 | 79 per 1000 (34 to 184) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 231 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (44 to 240) | |||||

| Catheter removal or replacement (number of patients) | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.46 to 1.46) | 395 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 115 per 1000 | 94 per 1000 (53 to 168) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 156 per 1000 | 128 per 1000 (72 to 228) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Unclear or high risk of bias in 3 of 5 studies 2 Wide confidence intervals due to small patient numbers

Abbreviations: CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; GRADE ‐ Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Summary of findings 2. Nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients.

| Nasal antibiotics versus no treatment for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with CKD on peritoneal dialysis Settings: tertiary settings Intervention: nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment | |||||

| Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes) | Study population | RR 0.94 (0.67 to 1.31) | 338 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low¹,² | ||

| 294 per 1000 | 276 per 1000 (197 to 385) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 331 per 1000 | 311 per 1000 (222 to 434) | |||||

| Exit‐site/ tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes) | Study population | RR 1.34 (0.62 to 2.87) | 338 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low¹,² | ||

| 165 per 1000 | 221 per 1000 (102 to 473) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 188 per 1000 | 252 per 1000 (117 to 540) | |||||

| Catheter removal or replacement (number of patients) | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.48 to 1.78) | 289 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low¹,² | ||

| 103 per 1000 | 95 per 1000 (49 to 183) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 265 per 1000 | 244 per 1000 (127 to 472) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹ Unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment in largest study (Mupirocin Study 1996) ² Wide confidence intervals due to small patient numbers

Abbreviations: CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; GRADE ‐ Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Summary of findings 3. Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant) for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients.

| Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant) for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with CKD on peritoneal dialysis Settings: tertiary settings Intervention: topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant) | |||||

| Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes) | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.65 to 1.06) | 853 (6) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 235 per 1000 | 195 per 1000 (153 to 250) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 152 per 1000 | 126 per 1000 (99 to 161) | |||||

| Exit‐site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes) | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.74 to 1.27) | 913 (7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 238 per 1000 | 230 per 1000 (176 to 302) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 222 per 1000 | 215 per 1000 (164 to 282) | |||||

| Catheter removal or replacement (number of patients) | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.57 to 1.38) | 792 (6) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 97 per 1000 | 86 per 1000 (55 to 134) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 93 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (53 to 128) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Unclear allocation in several studies 2 Imprecision due to small number of patients and events in several studies

Abbreviations: CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; GRADE ‐ Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Summary of findings 4. Antifungal versus placebo/no treatment for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients.

| Antifungal versus placebo/no treatment for preventing fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with CKD on peritoneal dialysis Settings: tertiary settings Intervention: antifungal versus placebo/no treatment during antibiotic course | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Antifungal versus placebo/no treatment | |||||

| Fungal peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes) | Study population | RR 0.28 (0.12 to 0.63) | 817 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 64 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (8 to 40) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 64 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (8 to 40) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 High risk of bias in one study (Lo 1996) 2 Imprecision due to small number of events and studies

Abbreviations: CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; GRADE ‐ Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

See: Table 1: Oral or topical or intraperitoneal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment for preventing peritonitis in PD patients; Table 2: Nasal antibiotics versus no treatment for preventing peritonitis in PD patients; Table 3: Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant) for preventing peritonitis in PD patients; Table 4: Antifungal versus placebo/no treatment for preventing fungal peritonitis in PD patients.

In most studies, the primary outcomes were peritonitis (number of patients), peritonitis rate, exit‐site/tunnel infection (number of patients), exit‐site/tunnel infection rate, and catheter removal or replacement (number). Many studies only included one or two of these outcomes. Other outcomes included all‐cause mortality, time to first catheter‐related infection, hospitalisation, death due to catheter‐related infection, technique failure, local pruritus/rash, and toxicity.

Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment

The oral antibiotic used was ofloxacin, cephalexin, rifampin or cotrimoxazole, and the topical antibiotic used was mupirocin ointment (exit site, nasal).

The use of oral or topical antibiotic prophylaxis had uncertain effects on the risk of peritonitis (Analysis 1.1 (5 studies, 395 participants): RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.19). There was low to moderate heterogeneity across these studies (I2 = 33%). The risk of peritonitis outcome was assessed as low quality because of unclear or high risk of bias in 3 of 5 studies and because of wide confidence intervals in all 5 studies due to small patient numbers.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 1 Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes).

The two interventions also had uncertain effects on the peritonitis rate (Analysis 1.2.1 (3 studies, 1440 patient‐months): RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.14), the risk of exit‐site and tunnel infection (Analysis 1.3.1 (3 studies, 191 participants): RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.04), exit‐site/tunnel infection rate (Analysis 1.4.1 (2 studies, 939 patient‐months): RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.05), risk of catheter removal or replacement (Analysis 1.5.1 (5 studies, 395 participants): RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.46), and all‐cause mortality (Analysis 1.6.1 (4 studies, 201 participants): RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.89), with no significant heterogeneity across studies for any of these analyses (I2 = 0%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 2 Peritonitis rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 3 Exit‐site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 4 Exit‐site/tunnel infection rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 5 Catheter removal or replacement (number of patients).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 6 Mortality (all‐cause).

The risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection outcome was assessed as low quality because of unclear or high risk of bias in all 3 studies and because of wide confidence intervals in all 3 studies due to small patient numbers. The risk of catheter removal/replacement outcome was also assessed as low quality because of unclear or high risk of bias in 3 of 5 studies and because of wide confidence intervals in all 5 studies due to small patient numbers.

Oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic

The use of antibiotic ointment prophylaxis (either sodium fusidate (exit site plus nasal) or mupirocin (exit site)) was compared with another antibiotic (oral ofloxacin, oral rifampin or gentamicin cream (exit site)) in four studies.

The interventions had uncertain effects on the risk of peritonitis (Analysis 2.1 (4 studies, 314 participants): RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.84). There was low heterogeneity across these studies (I2 = 9%). Similarly, topical antibiotic prophylaxis (either mupirocin ointment (exit site), sodium fusidate ointment (exit site plus nasal) or mupirocin cream (exit site)) compared with other antibiotic (either sodium fusidate ointment (exit site), oral ofloxacin or gentamicin cream (exit site)) had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site and tunnel infection (Analysis 2.3 (4 studies, 336 participants): RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.71 to 2.31). There was medium heterogeneity across these studies (I2 = 56%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic, Outcome 1 Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic, Outcome 3 Exit‐site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes).

Nasal antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo or no treatment

The use of nasal antibiotic prophylaxis had uncertain effects on the risk of peritonitis (Analysis 3.1 (3 studies, 338 participants): RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.31), the peritonitis rate (Analysis 3.2 (2 studies, 2797 patient‐months): RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.16 to 2.77), the risk of exit‐site and tunnel infection (Analysis 3.3 (3 studies, 338 participants): RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.62 to 2.87), the exit‐site and tunnel infection rate (Analysis 3.4 (2 studies, 2796 patient‐months): RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.92), and the number of patients with catheter removal or replacement (Analysis 3.5 (2 studies, 289 participants): RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.78). There was no significant heterogeneity across the studies for any of these analyses. Although in 1 study, there was a significant reduction in the exit‐site/tunnel infection rate when CAPD patients identified as S. aureus carriers (nasal) were treated with mupirocin ointment (nasal application, twice/day for 5 days, every 1 month), there were no significant differences with any of the other primary outcomes of interest (Mupirocin Study 1996).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 1 Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 2 Peritonitis rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 3 Exit site and tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 4 Exit site and tunnel infection rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 5 Catheter removal or replacement (number of patients).

The risk of peritonitis and the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection outcomes were assessed as low quality because of unclear or high risk of bias in all 3 studies and because of wide confidence intervals in all 3 studies due to small patient numbers. The risk of catheter removal/replacement was assessed as low quality because of unclear to high risk of bias in the 2 studies and because of wide confidence intervals in the 2 studies due to small patient numbers.

Pre‐ or peri‐operative antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo or no treatment or other antibiotic

Pre‐ or peri‐operative intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis compared with no treatment may reduce the risk of early peritonitis (less than one month from catheter insertion) in one study (Gadallah 2000c) but there was no difference between the interventions in three other studies using different antibiotics (Analysis 4.1 (4 studies, 379 participants). The single 3‐arm study (Gadallah 2000c) compared vancomycin with placebo, cefazolin with placebo and vancomycin with cefazolin and found the risk of peritonitis was reduced by vancomycin compared with placebo (Analysis 4.1.1 (1 study, 177 participants): RR 0.08. 95% CI 0.01 to 0.61) and by vancomycin compared with cefazolin (Analysis 4.1.6 (1 study, 178 participants): RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.84); there was no difference between cefazolin compared with placebo. None of the antibiotic interventions made a difference to the risk of exit‐site and tunnel infection (Analysis 4.2 (4 studies, 379 participants). When outcomes at more than one month after catheter insertion were considered, there was no difference between the interventions for the risk of peritonitis or exit‐site/tunnel infection.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Pre/peri‐operative prophylaxis versus placebo/no treatment or other antibiotic, Outcome 1 Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Pre/peri‐operative prophylaxis versus placebo/no treatment or other antibiotic, Outcome 2 Exit site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes).

Because each study used a different antibiotic intervention, it is not possible to comment on heterogeneity across the studies.

Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant)

Eight studies reported on the use of disinfectant at the exit site versus standard care or other active treatment. As the test for subgroup differences was not significant for any of our outcomes the total summary estimates are reported here.

Overall topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment had uncertain effects on the risk of peritonitis (Analysis 5.1 (6 studies, 853 participants): RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.06). exit‐site/tunnel infection (Analysis 5.2 (8 studies, 973 participants): RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.33), catheter removal or replacement (Analysis 5.4 (7 studies, 852 participants): RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.38), and all‐cause mortality (Analysis 5.5 (4 studies, 697 participants): RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.44), with no significant heterogeneity across studies for any of these analyses.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant), Outcome 1 Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant), Outcome 2 Exit site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant), Outcome 4 Catheter removal or replacement (number of patients).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant), Outcome 5 Mortality (all‐cause).

The risk of peritonitis outcome was assessed as low quality because of unclear allocation concealment and blinding in four of six studies and imprecision due to the small number of patients and events in five of six studies. The risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection outcome was assessed as low quality because of unclear allocation concealment and blinding in six of eight studies and imprecision due to the small number of patients and events in seven of eight studies. The risk of catheter removal/replacement outcome was assessed as low quality because of unclear allocation concealment and blinding in five of seven studies and imprecision due to the small number of patients and events in six of seven studies.

Other interventions

Seven studies reported on other interventions designed to reduce PD‐related infections. There was no difference in the peritonitis rate with other interventions.

Germicidal chamber for connection devices or soaking of the connector in antiseptic prior to bag exchange versus none (Analysis 6.1 (2 studies, 1855 patient‐months): RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.51)

Staphypan Berna antistaphylococcal vaccine (Analysis 9.1 (1 study, 1099 patient‐months): RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.59). Staphypan Berna compared with placebo was also shown to make no difference to the exit‐site and tunnel infection rate (Analysis 9.2 (1 study, 1107 patient‐months): RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.48).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Germicidal chamber versus none, Outcome 1 Peritonitis rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antistaphylococcal vaccine (Staphypan) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Peritonitis rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antistaphylococcal vaccine (Staphypan) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Exit site/tunnel infection rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

Three studies (140 participants) reported on the use of different dressing systems. There was no difference between the comparisons for the number of patients with one or more episodes of exit‐site/tunnel infection (Analysis 7.1) or the exit‐site/tunnel infection rate (Analysis 7.2 (1 study, 679 patient‐months).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Dressing systems (any), Outcome 1 Exit site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Dressing systems (any), Outcome 2 Exit site/tunnel infection rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

There was no difference between use of a silver ring on the PD catheter versus none for the risk of peritonitis (Analysis 8.1 (1 study, 195 participants): RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.66), risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection (Analysis 8.2 (1 study, 195 participants): RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.90) or risk of catheter removal/replacement (Analysis 8.3 (1 study, 195 participants): RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.35 to 4.56).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Silver ring system on catheter versus none, Outcome 1 Peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Silver ring system on catheter versus none, Outcome 2 Exit site/tunnel infection (number of patients with one or more episodes).

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Silver ring system on catheter versus none, Outcome 3 Catheter removal or replacement (number of patients).

Antifungal prophylaxis versus placebo or no treatment

The use of antifungal agents (oral fluconazole or oral nystatin) compared with no antifungal agent being given when a patient receives a course of antibiotics for bacterial peritonitis were reported in 2 studies. The antifungal intervention may reduce the risk of fungal peritonitis (Analysis 10.1 (2 studies, 817 participants): RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.63). There was low heterogeneity across the two studies for this analysis. The risk of fungal peritonitis outcome was assessed as low quality because of unclear risk of bias in 1 study and high risk of bias in 1 study and imprecision due to the small number of events and patient numbers. One study of oral nystatin in PD patients who were receiving treatment for bacterial peritonitis showed a significant reduction in the rate of fungal peritonitis due to Candida spp. with nystatin prophylaxis (Analysis 10.2 (1 study, 6864 patient‐months): RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.95).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Antifungal versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 1 Fungal peritonitis (number of patients with one or more episodes).

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Antifungal versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 2 Fungal peritonitis rate (episodes/total patient‐months on PD).

Adverse effects

For the comparisons which included oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, two studies (86 participants) provided some information on adverse effects of therapy. They were reported in relation to the use of oral rifampin and sodium fusidate ointment (nasal and exit site). More patients reported adverse effects with oral rifampin therapy but the results did not achieve significance. Heterogeneity could not be determined (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 8 Adverse effects.

For the studies which included oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic, three studies (419 participants) reported on adverse effects of therapy. The antibiotics used were applied daily/routinely to the exit site and included Polysporin triple ointment, gentamicin cream and cyclic oral rifampin against mupirocin ointment or cream. There were fewer patients who reported adverse effects with mupirocin but the result was not significantly different; nausea (Analysis 2.8.1 (1 study, 82 participants): RR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.59); pruritus (Analysis 2.8.2 (2 studies, 337 participants): RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.49).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic, Outcome 8 Adverse effects.

Three studies (289 participants) compared nasal antibiotics against placebo/no treatment and two of them reported information on adverse effects of therapy. The antibiotics used included mupirocin ointment (nasal) and sodium fusidate ointment (nasal and exit site) versus placebo ointment (nasal) or placebo tablets. More patients reported adverse effects with the antibiotic treatments (headache, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, nasal irritation/rhinitis) but the results did not achieve significance. Heterogeneity could not be determined (Analysis 3.7).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 7 Adverse effects.

For the studies which included topical disinfectant versus standard care or other active treatment at the exit site, four studies reported on adverse effects of therapy. The interventions that these reports related to were sodium hypochlorite solution, antibacterial honey and povidone iodine dry powder spray against povidone iodine solution, mupirocin ointment (nasal) or alcohol wipes. More patients reported adverse effects with use of the former agents and a statistically significant increase in pruritus occurred with topical disinfectants versus standard care (Analysis 5.7 (4 studies, 609 participants): RR 2.80, 95% CI 1.21 to 6.48; I2 = 44%). There was low heterogeneity of results.

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment (antibiotic or other disinfectant), Outcome 7 Pruritus (local).

Antibiotic resistance was not adequately reported in the included studies (Table 7).

3. Other outcomes analysed.

| Outcome analysed | Number of studies | Number of patients | RR (95% CI) |

| Oral antibiotic prophylaxis | |||

| Pruritus | 1 | 64 | 3.00 (0.13 to 71.00) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 64 | 0.09 (0.01 to 1.58) |

| Nausea | 1 | 64 | 9.00 (0.50 to 160.59) |

| Allergy | 1 | 64 | 5.00 (0.25 to 100.20) |

| Nasal antibiotic prophylaxis | |||

| Nasal irritation | 1 | 15 | 2.10 (0.10 to 44.40) |

| Rhinitis | 1 | 267 | 0.74 (0.27 to 2.09) |

| Headache | 1 | 267 | 0.99 (0.14 to 6.94) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 267 | 1.65 (0.40 to 6.78) |

| Nausea | 1 | 267 | 0.99 (0.14 to 6.94) |

| Vomiting | 1 | 267 | 2.98 (0.61 to 14.94) |

| Pruritus | 1 | 267 | 1.49 (0.25 to 8.77) |

| Topical disinfectants | |||

| Technique failure | 1 | 149 | 0.19 (0.01 to 3.83) |

| Pruritus | 1 | 149 | 10.29 (0.58 to 182.92) |

Outcomes sought but not reported

Very few studies reported on peritonitis relapse, development of antibiotic resistance (topical use), hospitalisation due to PD‐related infections or peritonitis, time to first peritonitis episode, technique failure (transfer from PD to haemodialysis/transplant due to peritonitis), or death due to peritonitis.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We identified 39 studies that compared antimicrobial agents with placebo/no treatment or other antimicrobial agent or standard care in CKD patients on PD. A range of antimicrobial agents were found and studies using antibiotic prophylaxis showed wide variability regarding the dose and duration of the interventions trialled. The duration of studies ranged from 1 month to 8 years. The quality of the evidence for all of the findings listed below was low.

Key findings are as follows.

The use of oral or topical antibiotic had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection and the risk of peritonitis.

The topical administration of antibiotic ointment to the anterior nares of PD patients (sodium fusidate or mupirocin ointment) had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection and the risk of peritonitis.

Pre/peri‐operative intravenous vancomycin may reduce the risk of early peritonitis in the first few weeks (< 1 month) following Tenckhoff catheter insertion but has an uncertain effect on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection. The comparisons using other antibiotics (i.e. IV gentamicin; IV cefazolin plus gentamicin; IV cefuroxime plus cefuroxime intraperitoneal) did not reduce the risk of peritonitis or exit‐site/tunnel infection.

The use of topical disinfectant had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection and the risk of peritonitis.

Oral antifungal prophylaxis (fluconazole or nystatin) with each antibiotic course given to a PD patient may reduce the risk of fungal peritonitis.

No intervention reduced the risk of catheter removal or replacement.

Oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic, nasal antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment, pre/peri‐operative prophylaxis versus placebo/no treatment or other antibiotic, topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment, germicidal chamber versus none, or silver ring system on catheter versus none had an effect on all‐cause mortality. Neither oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic nor topical disinfectants versus standard care or other active treatment had an effect on the risk of technique failure.

Heterogeneity among the studies was low except for the interventions oral or topical antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment and oral or topical antibiotics versus other antibiotic. Heterogeneity in the former comparison for the risk of peritonitis was 33% and was likely related to the variety of antibiotics used, the frequency of administration (daily, monthly, every three months), the route of administration (oral, topical) and the population studied (adults in Brazil, Canada, USA, Hong Kong). Heterogeneity in the latter comparison for the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection was 56% and was probably related to the range of antibiotics used, the frequency of administration (twice daily, daily, every 2 days, weekly), the route of administration (oral, topical) and the population studied (adults in the Philippines, Brazil, Hong Kong, USA).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Twelve studies reported all three primary outcomes of interest and could be meta‐analysed (peritonitis, exit‐site/tunnel infection, catheter removal/replacement), 15 studies reported two primary outcomes of interest, and 12 studies reported on one primary outcome of interest; two studies reported all primary outcomes in a way that could not be meta‐analysed (Axelrod 1973; Sharma 1971). Our meta‐analyses identified that use of oral or topical antibiotics had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection and the risk of peritonitis and did not appear to affect the exit‐site/tunnel infection rate, peritonitis rate, or the risk of catheter removal/replacement. It is unclear if the use of nasal mupirocin in identified nasal carriers of S. aureus reduces the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection or peritonitis. The use of pre/peri‐operative IV antibiotics at PD catheter insertion may reduce the occurrence of early peritonitis (within 1 month of insertion) with vancomycin being the most effective antibiotic to use. The RR of 0.08 for the outcome of early peritonitis could be classified as clinically important, should it be confirmed with future studies. The use of topical disinfectant had uncertain effects on the risk of exit‐site/tunnel infection and the risk of peritonitis. The co‐administration of antifungal agents with an antibiotic course appears to reduce the risk of fungal peritonitis developing in a PD patient. The risk ratio of 0.28 for the outcome of fungal peritonitis could prove to be clinically important, should it be confirmed with future studies.

No RCT was found which had the comparison of routine courses of intranasal mupirocin versus daily exit‐site mupirocin. Likewise, no RCT was found which compared S. aureus nasal carriage eradication at the time of PD catheter insertion versus no eradication of S. aureus nasal carriage. In addition, some outcomes were either not addressed (development of antibiotic resistance with topical use) or not often addressed (peritonitis relapse, hospitalisation rates due to PD‐related infections or peritonitis, technique failure due to peritonitis). It should also be mentioned that for most comparisons there are only a few studies and small numbers of patients.

Quality of the evidence