Abstract

Episodic memory retrieval relies on the recovery of neural representations of waking experience. This process is thought to involve a communication dynamic between the medial temporal lobe memory system and the neocortex. How this occurs is largely unknown, however, especially as it pertains to awake human memory retrieval. Using intracranial electroencephalographic recordings, we found that ripple oscillations were dynamically coupled between the human medial temporal lobe (MTL) and temporal association cortex. Coupled ripples were more pronounced during successful verbal memory retrieval and recover the cortical neural representations of remembered items. Together, these data provide direct evidence that coupled ripples between the MTL and association cortex may underlie successful memory retrieval in the human brain.

The medial temporal lobe (MTL) plays a critical role in episodic memory formation (1–5), yet successful memory retrieval also involves recovering neural representations that were present in the cortex when memories were first experienced (6–11). This has led to the hypothesis that the MTL may promote episodic memory retrieval through a dialogue with the cortex that recovers these neural representations, although howthis occurs is unknown. One possibility is that such a dialogue may be coordinated through fast oscillations termed ripples that have been implicated in learning and memory across species (12). Ripples in the rodent hippocampus and MTL structures are important for memory consolidation while awake (13, 14) and asleep (15,16) and are associated with memory replay (17–19). MTL ripples may indeed coordinate neural activity in cortical regions (20), and hippocampal ripples are coupled to ripples that have also been identified in the cortex in a learning-dependent manner (21). Human hippocampal ripples during sleep have been linked to memory consolidation (22, 23), but it remains unknown whether such ripples are relevant for awake human memory retrieval. Moreover, it is unknown if cortical and hippocampal ripples in humans are temporally coordinated and if such coordination may play a role in promoting successful memory retrieval.

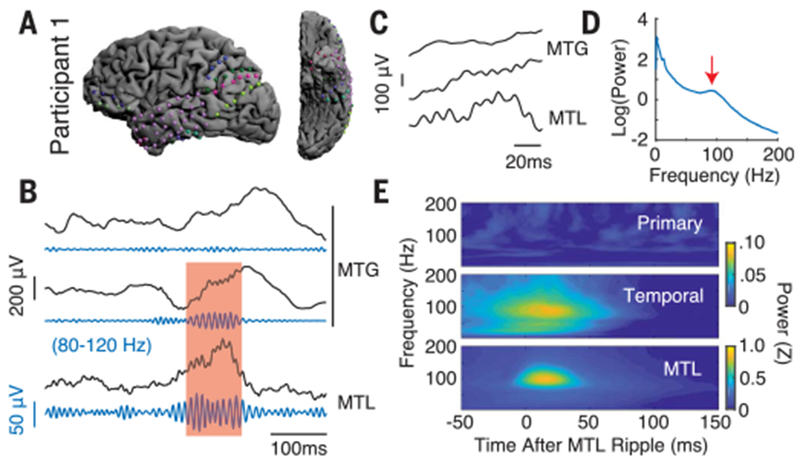

To examine this possibility, we analyzed intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG) signals from subdural electrodes placed along the MTL, as well as in other areas of cortex (Fig. 1A), in 14 participants (9 female; 36.2 ± 3.0 years) with drug-resistant epilepsy as they performed a paired associates verbal episodic memory task. We found several examples of ripple oscillations occurring simultaneously between the MTL and sites in the lateral temporal cortex (Fig. 1, B and C). Given the easily visualized ripples in the iEEG signals and the narrow-band power spectral density peaks present within single electrodes in the MTL (Fig. 1D), we extracted ripples in the 80- to 120-Hz band (mean baseline MTL ripple rate of 0.21 ± 0.02 Hz across participants; see supplementary materials), which is consistent with previous reports of human ripple activity in these frequencies (22, 23).

Fig. 1. MTL-coupled ripple oscillations are present in human temporal association cortex.

(A) Intracranial electrode locations for a single participant. (B) Unfiltered iEEG traces from single electrodes in the MTG and MTL with ripple band (80 to 120 Hz) filtered signals shown beneath each trace. Red shaded region is a representative ripple occurring concurrently across the MTL and one of the MTG electrodes. (C) Magnified view of ripples in shaded region. (D) Power spectral density for a representative MTL electrode from the participant shown in (A). Red arrow points to the ripple band local maxima at 92 Hz. (E) MTL ripple triggered spectrograms for each brain region during baseline. Warmer colors indicate a higher spectral power in that brain region after MTL ripples.

We then examined the temporal association cortex as a whole, including the anterior temporal lobe (ATL) and middle temporal gyrus (MTG) (24,25). As a control, we also examined primary motor and somatosensory cortex. To test the presence of coupled ripples in these two cortical areas, we examined spectral power in each cortical region triggered to the occurrence of MTL ripples at baseline. Across all participants, the temporal association cortex displayed a significant increase in average ripple band power during the first 50 ms after ripples in the MTL compared to the 50 ms immediately preceding an MTL ripple [t(13) = 2.41, p < 0.05, paired t test; Fig. 1E]. We did not observe any significant changes in ripple band power in the primary cortex locked to the occurrence of MTL ripples [t(8) = −0.85, p > 0.05].

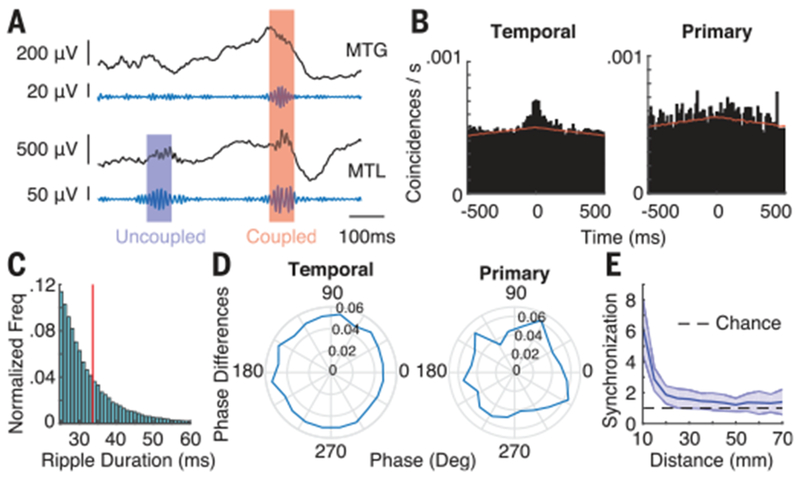

We subsequently observed several examples of dynamic coupling of MTL and neocortical ripples (Fig. 2A). The presence of MTL ripples that are at times coupled with a cortical electrode while at other times are uncoupled with that same electrode would be uncharacteristic if volume conduction alone were responsible for the observed coupled ripples between areas. To confirm that these ripples were temporally correlated, we performed a cross-correlation using the start indices of all ripples in each brain region compared to the start indices of the MTL ripples (Fig. 2B; see supplementary materials). The temporal association cortex demonstrated a clear peak in the cross-correlogram during baseline, whereas the primary cortex had a more uniform distribution. We generated a shift predictor (26, 27) that characterizes the coincidences expected by chance, and we quantified synchronization equal to the ratio of the crosscorrelation area to this baseline area in a ±50-ms window (see supplementary materials and fig. S5). Temporal cortex was significantly more synchronized than chance [synchronization = 1.26 ± 0.08 across participants, t(13) = 3.19, p < 0.01], whereas primary cortex was not [1.07 ± 0.04 ; t(8) = 1.77, p > 0.05].

Fig. 2. Cortical ripples are variably coupled to MTL ripples.

(A) Representative unfiltered iEEG and ripple band filtered traces from electrodes in the MTG and MTL. (B) Cross-correlograms for the temporal association cortex (left) and primary cortex (right) during baseline. Red line is the shift predictor generated by cross-correlating trials with all other nonmatching trials. (C) Distribution of ripple durations in the temporal association cortex across all participants. Red line is the average duration of 33.5 ms. (D) Phase differences for coupled ripple events in each brain region (inset values show normalized frequency for each phase). (E) Synchronization between electrodes in the temporal cortex decreases as a function of distance. Error bars indicate SEM across participants.

On the basis of these results, we identified coupled ripple oscillations as those instances when a neocortical and MTL ripple occurred with time indices within 50 ms of one another (see supplementary materials). Across all participants, the average ripple rate for an electrode in the temporal cortex was 0.24 ± 0.01 Hz and the average duration of each ripple was 34 ± 1 ms, whereas in the primary cortex we observed an average ripple rate of 0.27 ± 0.01 Hz, with an average duration of 35 ± 3 ms (Fig. 2C). We examined coupled ripples between every cortical electrode and every MTL electrode and found that 16.4 ± 5.3% of temporal cortex electrodes exhibited coupling with the MTL that was significantly greater than would be expected by chance, compared to only 3.3 ± 2.8% of primary cortex electrodes. Each brain region showed a near-uniform distribution of phase differences between coupled ripple oscillations (Fig. 2D), rather than the nonuniform distribution of zero–lag phase differences that would be expected by volume conduction (fig. S6). In addition, we found that the coupled ripples were highly localized events in the cortical electrodes. We computed a cross-correlogram of ripple events between every pair of cortical electrodes to generate a measure of synchronization within the cortical regions and found that ripple synchronization rapidly drops off within 2 cm (Fig. 2E; see supplementary materials).

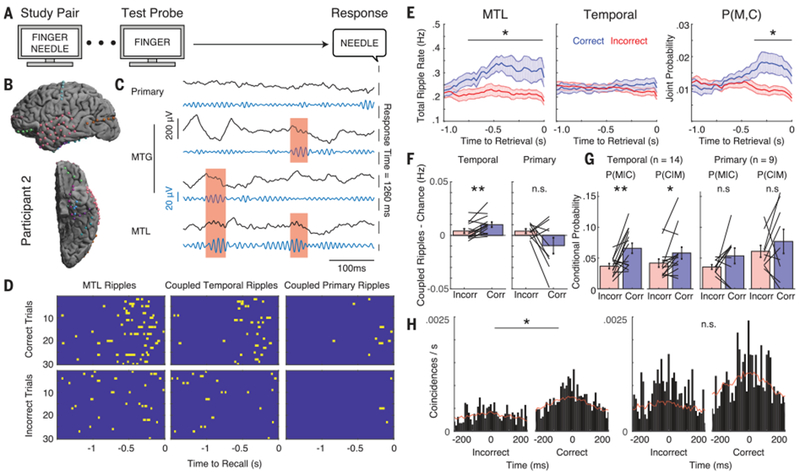

We hypothesized that coupled ripples may be relevant for successful memory retrieval. We therefore examined coupled ripples as participants performed the paired associates verbal memory task (Fig. 3A; see supplementary materials) (10,11). In a representative participant (Fig. 3B), we found an increase in the number of MTL ripples, and in the number of coupled ripples, that preceded vocalization during successful retrieval (Fig. 3, C and D). This was consistent across all participants. On average, successful retrieval involved a significant increase both in the number of MTL ripples, and in the number of coupled ripples between the MTL and temporal association cortex immediately before vocalization compared to incorrect trials (p < 0.05, permutation test, corrected for multiple comparisons over time; Fig. 3E; fig. S7, ripple rates, which are equal to the empiric estimates of the probability of ripple events; see supplementary materials). An increase in the number of coupled ripples could arise by chance, however, simply because the overall rate of ripples increased in the MTL (Fig. 3E). We therefore corrected the rate of coupled ripples by the rate expected by chance and found that coupling between the MTL and temporal cortex was significantly greater during correct compared to incorrect trials [Fig. 3F, t(13) = 3.33, p < 0.01; see supplementary materials]. We confirmed this by examining the conditional probability that a coupled ripple would be observed in the cortex given that a ripple was observed in the MTL, p(C|M) (Fig. 3G; see supplementary materials). This reflects the extent to which coupling is observed more than expected by chance, given the increase in MTL ripples. We also computed the conditional probability that a coupled ripple would be observed in the MTL given that a ripple was observed in the cortex, p(M|C), which reflects the extent to which any increases in MTL ripples are aligned to the cortical ripples. Across all participants, we found a significant increase in both conditional probabilities when examining coupling between the MTL and the temporal association cortex during the 500-ms time period immediately before vocalization during correct retrieval trials compared to incorrect trials [t(13) = 3.42, p < 0.01 for p(M|C) and t(13) = 2.41, p < 0.05 for p(C|M), paired t test; Fig. 3G]. These data suggest that successful retrieval specifically involves an increase in the extent to which ripples are coupled between the MTL and the temporal association cortex.

Fig. 3. Coupling of ripple oscillations increases during memory retrieval.

(A) Paired associates verbal memory task. (B) Intracranial electrode locations for a single participant. (C) Unfiltered iEEG and ripple band filtered traces during a successful retrieval trial from single electrodes in the primary cortex, MTG, and MTL. Red shaded regions indicate coupled ripples. (D) Raster plots for the MTL ripples (left) and ripples coupled with temporal cortex (middle) and primary cortex (right) for correct and incorrect trials. (E) Total ripple rates for the MTL (left) and primary cortex (middle) and their joint probability of being aligned in time (right). A significant increase in the total ripple rate was detected in the MTL and joint probability. *p < 0.05. (F) Temporal cortex demonstrated significantly increased coupled ripple rate after subtracting coupling expected by chance. **p < 0.01; n.s., not significant. (G) Conditional probabilities of observing coincident ripples between the MTL and temporal and primary cortices in the 500 ms preceding memory retrieval. P(M|C) indicates the probability of observing a ripple in the MTL given a ripple in cortex, and P(C|M) indicates the probability of observing a ripple in the cortex given a ripple in the MTL. (H) Cross-correlograms for correct and incorrect trials in temporal (left) and primary cortex (right) over the 500 ms preceding retrieval. Red lines indicate the baseline shift predictor. Significance was determined by comparing the synchronization (ratio of cross-correlation area to baseline area in a ±50-ms window) between conditions for all participants.

We confirmed that coupling between the MTL and temporal association cortex significantly increased during successful retrieval by also examining synchronization during memory retrieval. Across participants, we observed a significant increase in synchronization during all retrieval epochs compared to baseline [synchronization 1.37 ± 0.11, t(13) = 2.83, p < 0.05, paired t test; fig. S8]. In addition, we found a significantly higher level of synchronization in the 500-ms time period preceding vocalization during correct compared to incorrect trials in the temporal association cortex [t(13) = 2.26, p < 0.05, paired t test; Fig. 3H and fig. S9]. We confirmed that the observed differences in coupling were not simply due to differences in vocalization between trial types, were specific to the ripple band (80 to 120 Hz), were not present during memory encoding, were present even when only examining ripples of longer duration, and were observed even when excluding cortical ictal electrodes from our analysis (figs. S10 to S14). Notably, we also confirmed that these differences were specific to the temporal association cortex. We did not observe a significant increase in the corrected rates of coupling, in the conditional probabilities, or in synchronization during successful memory retrieval when we examined coupled ripples between the MTL and primary cortex [corrected coupling t(13) = −1.83, p > 0.05; p(M|C): t(8) = 1.44, p > 0.05; p(C|M): t(8) = 0.84, p = > 0.05; synchronization: t(8) = −1.08, p > 0.05; Fig. 3, F to H, and fig. S15], suggesting that the increase in MTL ripples alone is not sufficient to cause increased coupling with the primary cortex. Coupled ripples were also not significantly modulated in the prefrontal cortex during correct trials (fig. S16).

Because coupling of ripple oscillations increased directly before correct memory retrieval, we hypothesized that coupled ripples may reinstate neural representations of memory from the respective encoding periods. We constructed a feature vector reflecting the distributed pattern of spectral power across all electrodes locked to the occurrence of each coupled ripple oscillation during retrieval. We compared this feature vector to the patterns that were present during the encoding period in each trial (10, 11) (see supplementary materials). After coupled ripples in the temporal association cortex, but not the primary cortex, we found robust reinstatement of the distributed patterns of neural activity that were present during encoding during correct, but not incorrect, trials (Fig. 4A, left and middle, and figs. S17 to S21). We identified the encoding and retrieval time periods where ripple-locked reinstatement during correct trials was significantly greater than for incorrect trials and defined this as the temporal region of interest (tROI) (p < 0.01, permutation test; black outline, Fig. 4A, right). The mean reinstatement over this tROI in each participant demonstrated a consistent increase during correct compared to incorrect trials across participants [t(13) = 3.82, p < 0.01; Fig. 4B]. We confirmed that the reinstatement of neural patterns of activity was specifically related to coupled ripples in the temporal association cortex by randomly reassigning the time indices of coupled ripples during correct retrieval and finding significantly less reinstatement when the tROI was locked to those random time indices [Fig. 4C; see supplementary materials; correct true versus random time indices, t(13) = 2.42, p < 0.05; fig. S19b].

Fig. 4. Coupled ripple oscillations reinstate item-specific memory representations in the temporal association cortex.

(A) Average reinstatement across all participants triggered to the occurrence of coupled ripple oscillations (t = 0) for correct (left) and incorrect trials (middle). The temporal region of interest (tROI; black outline) constitutes all epochs that exhibited significant differences between the two trial types (right). (B) Mean reinstatement computed over the tROI for each individual participant (black lines) during correct and incorrect trials. **p < 0.01. (C) Reinstatement after randomly assigning time indices of coupled ripples during correct retrieval trials to 1000 ms before or after the true values. (D) Mean reinstatement across all participants when shuffling adjacent correct retrieval periods (left), all correct retrieval periods (middle), or all retrieval periods from all trial types (right). (E) Mean reinstatement across all participants, averaged over the tROI for each participant, during each shuffled permutation shown in (D). Error bars represent SEM across participants. **p < 0.01.

Finally, we confirmed that reinstatement locked to the occurrence of coupled ripples was specific to the individual item being retrieved from memory using a shuffling procedure. In each permutation, we shuffled trial labels for all trials, for all correct trials, and finally by just swapping the trial labels from adjacent correct trials (Fig. 4D). In all cases, the true unshuffled mean level of reinstatement in the tROI was significantly greater than the average reinstatement in each shuffled condition (p < 0.01, paired t test for each category; Fig. 4E), demonstrating that the pattern of neural reinstatement locked to coupled ripples is specific for each retrieved memory.

Our data demonstrate that increased ripples within the human MTL that are coupled with the neocortex mediate successful memory retrieval. Our results therefore build upon previous studies implicating ripples in memory in three important ways. First, we demonstrate that awake memory retrieval in humans involves a significant increase in ripple oscillations in the 80- to 120-Hz frequency range in the MTL. Second, we specifically show that the increased ripples in the MTL are coupled with ripples in the temporal association cortex. Third, we directly link coupled ripples to the reinstatement of cortical neural activity that was present during encoding. Taken together, our data provide direct evidence for and insights into the neural mechanisms of memory retrieval and suggest that coupled ripples may constitute a neural mechanism for actively retrieving memory representations in the human brain.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. H. Wittig Jr., V. Sreekumar, J. Chapeton, M. Gillett, A. Kumar, and L. Bachschmid-Romano for helpful and insightful comments on the manuscript. We thank J. H. Wittig Jr. for assistance with data collection and data curation. We are indebted to all patients who selflessly volunteered their time to participate in this study. We dedicate this work to the late Anslem Vaz.

Funding: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). This work was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) grant T32 GM007171 to A.P.V.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and are also available for public download at https://neuroscience.nih.gov/ninds/zaghloul/downloads.html.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/363/6430/975/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S22

Table S1

References (28–37)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Scoville WB, Milner B, J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 20, 11–21 (1957). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milner B, Psychiatr. Clin. North Am 28, 599–611, 609 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manns JR, Howard MW, Eichenbaum H, Neuron 56, 530–540 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller JF et al. , Science 342, 1111–1114 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eichenbaum H, Neuron 95, 1007–1018 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buzsáki G, Neuroscience 31, 551–570 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson JD, Rugg MD, Cereb. Cortex 17, 2507–2515 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staresina BP, Henson RNA, Kriegeskorte N, Alink A, Neurosci J. 32, 18150–18156 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deuker L et al. , J. Neurosci 33, 19373–19383 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yaffe RB et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 111, 18727–18732 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang AI, Wittig JH Jr., Inati SK, Zaghloul KA, Curr. Biol 27, 1700–1705.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonard TK, Hoffman KL, Curr. Biol 27, 257–262 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadhav SP, Kemere C, German PW, Frank LM, Science 336, 1454–1458 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roux L, Hu B, Eichler R, Stark E, Buzsáki G, Nat. Neurosci 20, 845–853 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sirota A, Csicsvari J, Buhl D, Buzsáki G, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 100, 2065–2069 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girardeau G, Benchenane K, Wiener SI, Buzsáki G, Zugaro MB, Nat. Neurosci 12, 1222–1223 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster DJ, Wilson MA, Nature 440, 680–683 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diba K, Buzsáki G, Nat. Neurosci 10, 1241–1242 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carr MF, Jadhav SP, Frank LM, Nat. Neurosci 14, 147–153 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jadhav SP, Rothschild G, Roumis DK, Frank LM, Neuron 90, 113–127 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khodagholy D, Gelinas JN, Buzsáki G, Science 358, 369–372 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Axmacher N, Elger CE, Fell J, Brain 131, 1806–1817 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staresina BP et al. , Nat. Neurosci 18, 1679–1686 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahn I, Andrews-Hanna JR, Vincent JL, Snyder AZ, Buckner RL, J. Neurophysiol 100, 129–139 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF, Cereb. Cortex 19, 72–78 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinmetz PN et al. , Nature 404, 187–190 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris G, Arkadir D, Nevet A, Vaadia E, Bergman H, Neuron 43, 133–143 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.