Abstract

Digital addiction (hereafter DA) denotes a problematic relationship with technology described by being compulsive, obsessive, impulsive and hasty. New research has identified cases where users’ digital behaviour shows symptoms meeting the clinical criteria of behavioural addiction. The online peer groups approach is one of the strategies to combat addictive behaviours. Unlike other behaviours, intervention and addictive usage can be on the same medium; the online space. This shared medium empowers influence techniques found in peer groups, such as self-monitoring, social surveillance, and personalised feedback, with a higher degree of interactivity, continuity and real-time communication. Social media platforms in general and online peer groups, in particular, have received little guidance as to how software design should take it into account. Careful theoretical understanding of the unique attributes and dynamics of such platforms and their intersection with gamification and persuasive techniques is needed as the ad-hoc design may cause unexpected harm. In this paper, we investigate how to facilitate the design process to ensure a systematic development of this technology. We conducted several qualitative studies including user studies and observational investigations. The primary contribution of this research is twofold: (i) a reference model for designing interactive online platforms to host peer groups and combat DA, (ii) a process model, COPE.er, inspired by the participatory design approach to building Customisable Online Persuasive Ecology by Engineering Rehabilitation strategies for different groups.

Keywords: digital addiction, online peer groups, persuasive social networks, behaviour change, persuasive systems design

1. Introduction

Social software has fundamentally reshaped the way people interact. On the one hand, it provides interactive tools to build and maintain social connections and facilitate mass interactions and collaboration among individuals. On the other hand, the emergence of virtual communities and social networks and their various forms has led to changes in modern societies’ communication which can be seen negative in specific contexts and modalities of usage [1]. The increasingly notable cases in which people feel addicted to their use have also led to an increasing interest to explore this behavioural phenomenon. The patterns of use of these technological advances seem to match the criterion of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [2]. The case of online gambling is the closest example where people may immerse overly in the online space, take reckless decisions and fail to self-control their online behaviour [3].

To date, most of the recent research in DA (digital addiction) has been conducted from the social science [4] and psychological perspectives [5]. In other studies, the correlation between motives for social media use and social media addiction [6], as well as the association with gender [7] was investigated. Past literature has also shown that many studies on DA are focused on the development of usage measurement scales, e.g., [8,9,10]. We argue that software design can be a part of the DA problem and, also, support its solution. We also advocate software engineering and interactive systems design communities would need to work closely with psychology and behaviour change and empower the design of future digital technology with addiction-awareness layer and provide facilities to users to combat addictive usage patterns [11,12].

The recognition of software role and the potential of using persuasive techniques has led to a growing interest in utilising software-assisted self-regulation systems to moderate digital usage. Typically, these systems motivate users to take some responsibility to adjust their behaviour. Persuasive messages and interactive warning labels can help to initiate and maintain that change [11]. Another software-assisted system was developed to intervene with college students to reduce online usage [13]. The system offered interventions in the form of online plans based on usage which was complemented with reminder cards. The study results revealed that the intervention system efficiently reduced students’ online usage per week. In another study on smartphone addiction, the researchers proposed an intervention system to manage the usage of smartphone [14]. The system consisted of four primary functions: monitoring, data archive, data analysis, and tailored intervention based on actual usage. However, the sustainability of the change and the design process for building such software remain open issues. In addition, the study treats internet usage as being uniform and reduce the problem to a matter of time spent online which is just one aspect of DA, e.g., addictive behaviour attributes like salience and conflicts are not studied.

A study surveyed 41 smartphone intervention apps meant to help people regulate smartphone usage [15]. These apps were classified into four themes: (1) smartphone addiction diagnosing, (2) overuse intervention, (3) children use monitoring, and (4) task distraction elimination. Different persuasive techniques were used, such as self-monitoring, usage tracking and apps locking features. The study, then, highlighted that the primary task support dimension [16] was the dominant intervention strategy and proposed an approach to limit smartphone usage through improving self-regulation based on the Social Cognitive Theory [17], i.e., social comparison and surveillance. The approach facilitates forming groups and consists of three components: self-monitoring, goal-setting and social learning and competition.

However, most existing approaches to combat DA need clinical evidence [18]. There is also a high possibility of having adverse side-effects, such as technology dependency and anxiety about self-diagnosis [18]. Another research study found that using peer groups to mediate interventions can be harmful as it may introduce negative behaviours such as normalising the problematic behaviour and reducing its culpability due to excessive peer support [19]. Also, utilising traditional software design processes and models to build persuasive systems for behavioural change is questionable, e.g., in the notion of user requirements and its peculiarities when users can have a degree of denial and conflict in their requirements and preferences [20]. Also, the reliance on de-facto social software constructs may not be sufficient enough for designing online environment to influence behaviours for users who want to achieve specific goals and make a positive change [20]. In addition, using such systems and their features, e.g., chat and praise, to mediate behavioural change may lead to adverse consequences as they were not built for this purpose but mainly to increase openness and connectedness which is a double-edged sword if used for problematic behaviour such as DA.

In this paper, we provide a systematic approach to the design of online peer groups platforms to combat DA and minimise the potential for adverse counterproductive interactions. We highlight new challenges typically found when developing software for combatting addictive behaviours, especially when dealing with users’ requirements which have nuances and unique characteristics in this domain, e.g., using software which may cause discomfort and be in conflict to a user’s current desire to achieve a desired behaviour and style of usage in the long term. We provide engineering principles for online platforms that host peer groups and enable interventions to combat problematic behaviours associated with the use of technology. Our solution is meant for users who are willing to adjust their usage style and still at the stage of moderate addiction.

Our research studied the case of the social network as a representative example of addictive cyberspace. By social network, we mean any software-based platform for social interaction outside a business environment. We also note that addiction is a complex behaviour and usually driven by underlying issues that need to be addressed for the success of an intervention. As such, this research argues that behavioural change strategies and approaches including online peer groups will complement clinical treatment and counselling and act as an early intervention, i.e., helping addicts to start the cycle of change. However, to achieve that, the design should ensure certain pre-conditions, e.g., willingness and readiness to change, openness to shortcomings and being free from denial of reality. These can be seen as extra social requirements to ensure the success of our proposed system and to be appropriately integrated into the treatment programmes provided by professionals in treatment centres.

2. Background

2.1. Risk Factors of Digital Addiction

There are several factors that can contribute to DA. Through the review of the literature, factors were clustered into two main dimensions, individual and contextual. Mental disorders, such as attention-deficit, hyperactivity and social anxiety can be linked to DA [21]. One study identified that checking behaviours including “brief, repetitive inspection of dynamic content quickly accessible on the device” can become habitual and hence lead to some degree of addiction [22]. Another study looked at the relationships among social benefits, online social network dependency, satisfaction, and youth’s habit formation [23]. Disinhibition [24], self-disclosure [25] and hyperpersonal aspect [26] are further examples of associated behaviours.

Personality traits can influence how people interact with digital technology. Impulsive personality, which has “tendency to respond impulsively without sufficient forethought” [27] has been shown to have a direct link to DA [28,29]. There is also a wide range of emotions linked to DA, such as the anticipation which is an emotional motor of checking habit in that users become worried about what is going on online [30]. The anticipation is also part of escapism or the desire to change the mood state. Social network features, e.g., news and notifications and ad-hoc responses, can be argued to be using anticipation to keep users engaged. This is often framed positively as enhancing users’ experience while the potential of facilitating DA experience is often neglected.

DA relates to users’ requirements as well. People use a software product as a means to reach specific requirements such as increasing popularity and connectedness; however, while doing so, they may eventually develop a problematic usage style [12]. These requirements can be classified into three main categories: motivational, value-related and goals. The differences between these requirements and their influence on human-computer interactions were discussed by Kujala and Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila [31]. In [32], Bumgarner investigated the tacit nature of such requirements giving further types such as exhibitionism, voyeurism, conformity and social recognition. We argue in this paper that these same features can also be used to aid people to regulate their usage in a social setting. In other words, the motivations, values and goals of our particular kind of social network are to reach a usage style which is consciously regulated.

DA can also strongly relate to contextual factors including the software systems design. Designing for behavioural change, whether to make the cyberspace more engaging and immersive or to increase conscious and regulated nature of the usage, with neglecting behavioural context can lead to unintentional results based on the long-term experience. The transformation of human behaviours could be related to: (i) dispositional attribution, i.e., “The Bad Apples”, (ii) situational factors, i.e., “The Bad Barrel”, and/or (iii) the system, i.e., “The Bad Barrel-Makers” [33]. The last dimension calls for considering the design of the system that made the situation take an undesirable and unpleasant twist. In online peer groups to combat addictive behaviours, members can experience recurring episodes of relapse and denial. This may cause behavioural contagion and reinforcement of behaviour instead of correcting it. Hence, such a mechanism can be a double-sided sword to be managed in both its design and operation phases.

In terms of the software design, Young and Abreu argued that “some applications might serve as triggers for the reinforcement of continuous use [34]. This means that patients should stop navigating particular web sites or even certain applications”. The problematic usage behaviours could be triggered by external cues such as updates notifications [35]. Also, the variable discoveries by “surprise and serendipity”, such as suggesting new friends on Facebook, act as a powerful rewarding mechanism [36]. Such discoveries (aka Variable Ratio Reinforcement Schedule) provide “variable degree of unpredictable rewards” [34]. When these rewarding discoveries are learned and personalised, users tend to spend more time online than they initially intend to [37]. It was, also, claimed that human beings’ bodies release dopamine every time distractive updates arrive, e.g., a new likes or comments [38,39]. These updates may act as stimuli that bodies want to attain and with time people can become used to getting them to change the mood. This is an important aspect when considering the growing interest in studying the use of social media as a platform to attract collective attention and gain public recognition [40]. This, also, includes the body of research looking at different information properties (e.g., “vivid details”, interest factors, information richness and intensity) to understand their role in attracting an audience on social media [40,41].

User interface prosperities such as usability, accessibility, customisation and multitasking might also play important roles in facilitating DA. However, more studies need to be conducted to clarify the extent and significance of their influence. A study by Eyal [42] proposed the hook model which consists of four phases: trigger, action, variable reward and investment. This model was proposed to explain how companies develop habitual products. The study demonstrated that users are triggered internally or externally to perform an action, e.g., post a Facebook status. The action is performed due to an anticipated reward(s). The action phase is designed based on two usability engineering principles: ease of use and motivation. The online space designs which embrace these two principles increase the chance of users starting to take actions. These actions are then linked carefully to variable rewarding that should not be made predictable. As users invest time, money, or efforts, they are likely to be “hooked” to the software in its action-reward loop.

2.2. Modalities for Behavioural Change

There are different modalities for treating addictive behaviours. Modality refers to the setting of delivering treatment or a prevention approach. This includes self-help which aims at assisting individuals in obtaining behavioural interventions without attending treatment programmes [43]. It is mainly focused on enhancing individuals’ belief about their capacity, i.e., self-efficacy, to achieve their own goals [44]. Therapeutic counselling, on the other hand, is a private, often confidential and counsellor-delivered modality where individuals attend counselling sessions to express their issues, feelings and limitations. Typically, a counsellor elicits subjective aspects and descriptions of the patients’ experience while taking the role of an active and deep listener to explore their points of view and to highlight the points that need to be clarified further [34]. Support therapy focuses on providing social and emotional support. The support can be of two main categories: natural support (e.g., family and friends) and formal support (e.g., professional and communal) [45]. Peer groups can be classified as formal support if counsellors are involved, while communal if it is run as a peer-to-peer social network. It can also be operated in a blended modality where the governance and implementation of peer support is a shared responsibility between counsellors and peers.

Support therapy can also be offered online. Online therapy is defined as “the provision of mental health services through the Internet” [46]. There are concerns about the full reliance on this modality and whether it shall be used in combination with face-to-face sessions, e.g., at least at the start of the therapy. One of the concerns is the impact of the patients being geographically separated from their counsellors (aka therapeutic alliance). In healthcare practices, professionals stress the need for the therapeutic relationship to increase engagement, generate hope, and ensure positive transference. This is to build objective-relationship [47] and working alliance that is conceptualised in three components: task, goal and bond [48]. In recent studies, the results suggested that online modality can also have its advantages, such as making people more comfortable and less intimidated [49]. The benefits can also be in terms of the effectiveness as the online space provide novel features of which are real-time, interactive and even immersive (e.g., virtual reality, gamified systems, role-playing, therapy networking, and online support groups). Also, it empowers self-regulation by enabling self-monitoring, behaviour tracking, and visualisation [50]. In relation to DA, the use of online support can be controversial as the online space becomes both the medium for the problem and the solution. Hence, research on the systematic design, managed interaction, and usage of online peer groups is still needed.

Online Peer Groups

Peer groups can be defined as a “process by which persons voluntarily come together to help each other address common problems or shared concerns” [51]. Several theoretical frameworks can help to understand the processes underpinning peer groups. This includes:

Self-Psychology and its role in explaining, for example, concepts related to interpersonal conflict in social contexts (e.g., “role captivity”), the role of helping others to strengthen the identity, and how values are weighted based on the context (e.g., using the strength as an attribute to judge someone’s physical characteristics and the honesty attribute to judge the performance of a political party leader) [52].

Cognitive Consistency Theory which suggests that behavioural change can motivate attitudinal change. This theory is linked to other theories such as Self-Perception theory, Balance theory, and Cognitive dissonance. It also highlights the role of helping others to resolve behavioural ambivalence [53].

Helper therapy principle which suggests that those offering help are also benefiting from the commitment to behavioural maintenance, i.e., “self-persuasion through persuading others” [54]. This is also a recognised concept in Social Psychology [55]. For example, it is common to see recovered problem gamblers having their social network accounts to help others and at the same time demonstrate their new lifestyle and duration for which they are recovered which can be seen as a relapse prevention technique.

Social Learning Theory which suggests that, in social contexts, some processes of the observational learning (e.g., “copying”, “internalisation”, and “role-taking”) can help to accelerate behavioural change [56].

Group Psychotherapy which proposes some key factors of the help processes and dynamics when it is delivered in small groups. These factors include, for example, universality (i.e., realising that a problem is a common concern helps to alleviate isolation), altruism (i.e., the role of helping others can improve self-esteem and support the healing process), and installation of hope (i.e., increase help expectations can improve the treatment outcomes, e.g., mixing people at different stages of the rehabilitation can inspire those suffering from a higher severity and those starting the treatment) [57].

A study by Hepworth et al. [58] classified groups into two types: (i) treatment groups and (ii) task groups. Each type has distinct characteristics. In the treatment groups, the communication style follows an open style where self-disclosure discussions are expected to be high. The members’ roles evolve and are shaped through interaction over time. The progress evaluation in this type is based on meeting the treatments goals. Tasks groups, on the other hand, follow a structured communication style with low self-disclosure. Procedures are more formal, and roles are normally assigned. Achievements evaluations are based on accomplishing tasks.

Online peer groups are a type of social software that utilises certain behaviour change and persuasion mechanisms, such as social pressure through surveillance [59], to challenge negative behaviours or to reinforce positive ones [1,51]. The design of online peer groups for DA can embed features and interaction styles spanning across both treatment and task groups. The need for formality, i.e., task groups, is mainly due to the risks of reinforcing a negative behaviour or trivialising it. The need for high self-disclosure and a degree of autonomy, i.e., treatment groups, is to give a sense of ownership and commitment especially that users can be geographically distributed with little or no face-to-face contact with each other and the counsellor.

An empirical study proposed a model that views online peer groups as a tunnelling-based persuasive technique [20]. Based on the tunnelling principles articulated by Fogg [59], Alrobai et al. [20] recommended that online peer groups should have: (i) a high control over the interaction environment where the persuasion expected to occur, (ii) a carefully designed user experience where the level of uncertainties is decreased as groups progress in the treatment, (iii) a controlled or guided experience where users are walked through a pre-defined multi-stages process, and (iv) the pre-requisite that people voluntarily enter the tunnel, i.e., people in online peer groups admit having the problem and freely seeking help.

2.3. Theories of Behavioural Change

This section presents the main theories and models that help the understanding of the core dynamics of help provided through different modalities of behavioural awareness and change. These theories aim to explain the factors that interplay in the process of behavioural change. It can be argued that each theory and model focus on specific aspects, but they can still complement each other to provide a more holistic picture of human behaviours.

Theory of Planned Behaviour [60] which is a social cognition model that emphasises the role of the intention to predict actions [61]. It is suitable to identify what to change, i.e., factors, but not to offer suggestions for change [62]. The theory constructs can be mapped to some processes of the Transtheoretical Model [63]. These processes are consciousness raising, environmental re-evaluation, dramatic relief, self-liberation. For example, self-liberation is about the belief in the ability to change, i.e., perceived behavioural control according to the theory of planned behaviour. Also, the theory can be utilised to identify which intervention strategies to use. For example, the normative influence as a persuasive principle [16] may yield better outcomes if the issue stems from erratic perception, e.g., “no one can reduce digital usage, it is both pervasive and mandatory”.

Social Cognitive Theory [64] which is also a social cognition model that emphasises the key role of individuals’ intentions to predict actions. It shares the key principle (i.e., intention) of the Theory of Planned Behaviour but places a greater emphasis on the self-efficacy [61].

The Control Theory [65] is “a general approach to understanding the self-regulating systems”. It requires goal(s) as a “reference value” to compare against the current rate of the behaviour. This theory is rarely used as a baseline for intervention systems for addictive behaviours due to the difficulty in setting standards [61] which stems from distorted goals (e.g., smoking improves mood) and conflicting ones (e.g., living healthy and enjoying the moment) [66]. Yet, this concept of behavioural monitoring has been widely used in self-regulating systems [61]. The use of software-assisted monitoring and feedback provides new potential for this theory for monitoring and combatting DA.

Transtheoretical Model [67] which suggests that the behavioural change goes through five milestones: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. It was pointed out that individuals might be trapped in one of the early stages unless the system applies planned interventions to progress them [67].

Health Belief Model (HBM) [68] which has the main assumption that individuals “must feel personally vulnerable to a health threat”, as protective measures would be perceived necessary and, hence, potentially performed [69]. It was argued that while there is a lack of HBM-based interventions [61], the model can provide a useful understanding of DA. It was found that some constructs of the HBM (e.g., perceived benefits and barriers) are risk factors for the DA [70].

Goal Setting Theory [71] which suggests that goal setting can have a positive impact on the performance. The two pillars of this theory are (i) specificity (i.e., “reference point”) in which targeting a specific goal(s) is more effective than ‘do-your-best’, and (ii) difficulty which revolves around the perceived capability to achieve the goals.

3. Aim, Foundations and Research Methodology

In this section, we describe our previous work, common grounds and assumptions and then elaborate on the research method which we followed to generate the results.

3.1. Research Aim, Background and Assumptions

This research aims to provide engineering principles for online platforms that host peer groups and intervention to combat problematic behaviours associated with the use of technology. This deals with users who are willing to adjust their usage style and still at the stage of moderate addiction.

In this research, we draw upon and extend our previous work [20]. In this prior work, we first proposed a model that highlights different transitions in group work and how the focus of the activities and tasks performed changes based on the progress through these transitions. This is to guide designers on how the platforms should operate. Secondly, we characterised the tasks performed in online peer groups in three dimensions, immediate motivators, mode of delivery, and method of delivery. Thirdly, the collected observational data helped to reveal different types of roles that can exist within small groups for behavioural change. These roles represent social status and behavioural patterns, and they are meant to inform the design process and management of the online platforms for peer groups. Finally, we revised the Honeycomb Framework [72] to expressly fit the functional requirements of online peer groups for addictive behaviours. Then, we highlighted points to consider when building online peer groups to combat addictive behaviour. In this paper, we present the rest of the results in which other substantial aspects of online peer groups are investigated. We will also propose an engineering method to guide the design of online platforms for peer support groups to combat DA.

DA has not been recognised formally as a psychological disorder yet, and we use the term mainly metaphorically. Although some research has demonstrated how DA exhibits similar symptoms to behaviour addiction [73], we emphasise that it would be hard to measure DA and judge its existence in a person due to: (i) the complexity of the issue, and (ii) the difficulty to diagnose the relation between the problematic online usage, the online space design, and online content on one hand, and the usage and more profound personal and contextual factors on the other hand. Our research is not meant to confirm or reject the existence of DA but rather to provide ways for managing what people perceive to be a problematic or addictive online usage.

According to Ng and Leong [74], there are three main stages of addiction: early, intermediate and advanced. Each stage represents a different level of self-control and distinct attitudes and behaviours. Regardless of the extent to which the object of addiction dominates decision-making processes, individuals can be guided through the levels of change according to the Transtheoretical Model [63] which articulates six levels to progress to healthier behaviour. While the online peer groups’ intervention aims at supporting individuals at all severity levels, those in the transition to addiction stage (i.e., intermediate stage) will be the main targeted audience. The reason is that tailoring the system to support those in the severe addiction stage seems to be very challenging and risky especially that our solution is meant to be run in a blended modality involving counsellors direction and, also, individuals’ autonomous self-regulation and interaction with peers.

The behavioural addictions and substance addiction have inherent similarities in terms of the symptoms and consequences. From the perspective of cognitive behavioural therapy, both types of addictions share similar diagnoses and intervention strategies [75]. This suggests that many principles, recourses, and practices in substance addiction can be adopted and applied to behavioural addiction, such as DA. Some studies, such as [76], found that Internet Addiction can be used as an important predictor for early stages of substance abuse and vice versa. This is because both addictions follow similar behavioural patterns and individuals share personality attributes [77]. Nevertheless, the variables of change, i.e., influences that could inspire individuals to change, can be different from a type of addiction to another [69].

Persuasive technology raises ethical issues, such as privacy, autonomy, social pressure, and the leaning towards designers’ intent [78]. As such, Davis in [78] argued the need for users’ involvement throughout the design process as a key aspect to uncover any ethical concerns. Then, the author recommended Value Sensitive Design (VSD) and Participatory Design (PD) as two methodological frameworks that have great potential to account for such ethical issues. In this research, we give more priorities to users’ subjective interpretations of the social phenomena they are part of and to their understandings of their own actions. This motivated our proposed method to adopt a participatory approach to systematically manage the life-cycle of the design. This is by taking an iterative and interactive approach to refine the design, reduce the number of the biased design decisions, promote communication in the development team, and, more importantly, increase adoption of the decisions and judgements made, as well as maintain interest to sustain change.

3.2. Research Methodology

This research is based on two observational studies to develop the first version of the reference architecture, design artefact and COPE.er method followed by a Case Study to apply them in practice and refine and consolidate them further.

3.2.1. Observational Studies

We conducted two observational studies to understand peer groups including the session environment, interaction styles occurring between groups’ members and how interactions are governed. In the first study, we performed a 4-months observational study in face-to-face peer groups for treating substance and behavioural addiction. The study was performed in a rehab centre in the UK combined with interviews with an addiction counsellor to clarify the observations. The study was supported by a document analysis method using the forms and diaries utilised by patients in their daily practice. The rehabilitation centre offers inpatient residential care for patients suffering from substance addiction (including drugs and alcohol) and behavioural addiction (including gambling and sex). The rehab centre provides face-to-face group support and counselling. The management of the centre wants to extend its outreach to offer online help. Their goal is to increase treatment options by offering online help to those suffering from a problematic use of digital media as well. This is, also, to extend their help and offer online support to those in remote areas.

In the second study, we performed a 2-months observational study on an online platform for peer groups designed for treating problematic gambling and facilitated by a counsellor from a gambling recovery in the UK. The study has enabled comparing the practices in both the physical space and the cyberspace. More information about the observational study, those who were observed, and a partial analysis of the data collected can be found in [20] which discussed various design aspects of peer support groups. These aspects include group development and interaction, tasks to be performed, roles that can exist in the groups, interaction environment, and the building blocks of such platforms. These findings helped to form the basis of the proposed method in this paper. The full description of the studies can be found in [79].

Through these two observational studies and utilising our work in [80,81], which investigated the design and risk factors of persuasive intervention technology to combat DA, and our work in [1] which investigated online peer groups as a persuasive tool to support long-term behavioural change to combat DA, we developed the following outputs to be presented in the rest of the paper:

-

(1)

A reference architecture which identifies the main components of online peer groups platforms to regulate DA (Section 5.1).

-

(2)

A set of design artefacts to assist the design development of such platforms. The artefacts, also, includes a list of nine heuristic principles to aid stakeholders to inspect the design and to ensure optimal functionality to combat addictive behaviours (Section 5.2).

-

(3)

A method consists of nine activities to bring focus, clear structure and the logic about the relationships between design decisions and intended functionality of online peer groups platforms. It also promotes participatory decisions making by involving end-users in the design activities (Section 5.3).

3.2.2. Case Study

We conducted a case study to refine the outputs described in the previous section. The case study will aim at evaluating the proposed method in terms of the:

Understandability by assessing the extent the method is easy to grasp, and whether the provided tools are useful and straightforward to understand.

Comprehensiveness by assessing the extent to which the method covers different activities needed in the design process.

Appropriateness by assessing the applicability of the method to the process of designing for the online space for peer groups and its ability to support the design team to incorporate various good practices.

Usefulness by evaluating how the method facilitates and enhances the communication and exchange of information during the design process and how it regulates the involvement of the end-users who potentially experience problematic usage of digital media as well as the participation and role of the counsellors.

The case study approach was, also, meant to: (i) apply a holistic analysis—in the sense of multidisciplinary view—of the proposed method by recruiting participants from different disciplines, and to (ii) collect reactions and reflections on the use of the method and its supporting artefacts.

This is by applying them in practice to find out how they can be improved and whether more materials are needed to increase their quality. Also, as the research hypothesises that the proposed method will yield better results when it is utilised in a collaborative environment, e.g., focus group, we investigated how a participatory approach will contribute to the outcomes of the design process itself. This will also help to understand the dilemma of involving end-users in the design process and the concerns may arise due to the potential biased choices. The final version of these outputs, i.e., after being confirmed and refined through the case study, is presented in Section 5. In other words, Section 5 presents the final version of the artefacts after validating and refining them through the case study performed in the current paper. The material used in the case study can be found in [79].

Case Study Participants

The refinement of the outputs required a specific set of participants who can play different roles in the case study. The proposed engineering method is expected to be used by development teams consisting of three types of stakeholders: (i) designers who are experts in the technical side including social software design, software development and HCI, (ii) counsellors who possess the needed psychological background knowledge, and (iii) representative set of people with DA who would like to use the technology when developed.

We have used a convenience sampling via announcing the study through the mailing list of students and staff within the research group (involving both Computing and Psychology departments) and also through communicating with two addiction recovery charities in the UK. For participants who were to play the role of peer groups members, an adapted version of the alcohol use disorders screening test, which is known as the Cut Down, Annoyed, Guilty and Eye Opener (CAGE) questionnaire [82], was created to fit the properties and remit of DA and utilised as a DA screening tool. The adaptation included modifying the phrasing of the statements. For example, statement three of the original instrument which was read as follows: “Have you ever had guilty feelings about drinking?” has been rephrased to “I sometimes feel bad or guilty about my use of digital devices”. We also added two statements to enable detecting other patterns of behaviours that indicate problematic usage. These two statements read as follows: (i) “I have tried to control my use of digital devices without success”, and (ii) “I would become restless or troubled if I stop using digital devices. For end-users to be selected, the research required having two affirmative responses out of six as an inclusion criterion. The designers and counsellors were invited based on their expertise via convenience sampling. Table 1 and Table 2 provide information about the recruited participants.

Table 1.

The background of the participants.

| Participants | Role | Age | Gender | Field of Study | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Designer | 30–40 | Male | Computing | 13 |

| P2 | Designer | 30–40 | Male | Computing | 8 |

| P3 | Designer | 30–40 | Male | Computing | 5 |

| P4 | Designer | 30–40 | Female | Computing | 5 |

| P5 | Counsellor | 40–50 | Male | Psychology | 17 |

| P6 | End-user | 20–30 | Male | Computing | N/A 1 |

| P7 | End-user | 20–30 | Male | Computing | N/A 1 |

| P8 | End-user | 20–30 | Female | Computing | N/A 1 |

1 Not applicable as the years of experience does not apply to participants who roleplay the end-users’ role.

Table 2.

The expert participants’ familiarity with relevant topics 1.

| Participants | Designing for Behavioural Change | Behavioural Addiction | Human-Computer Interaction | Social Informatics | User Involvement | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| P1 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P2 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P3 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P4 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P5 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||||||

1 The questionnaire was based on 5-points Likert scale which can be interpreted as follows: (1) Very Poor (2) Poor (3) Fair (4) Good (5) Very Good.

The participants were given a peer group of six fictional characters of a rehab centre with DA problem, and then they were asked to create a prototype that caters for the treatment needs of those patients (i.e., group members). These six fictional members were created to act as personas that encapsulate different types of behaviours of users who might use the online peer group system. Personas are typically defined as a representation of fictional characters that are developed depending on actual users’ data to represent different types of users in the design process [83]. The given fictional six group members (i.e., personas) were developed based on the actual data obtained from the qualitative studies conducted in our prior works [1,20,81], and they mainly cover the social roles described in [20].

Case Study Procedure

An experienced research facilitator presented an introduction to the topic of the research, i.e., online peer groups as a motivational approach to regulating digital usage. This was followed by introducing the purpose and focus of the study. The evaluation was divided into two phases. Both phases had the same goal, but each had different tools to facilitate comparative analysis.

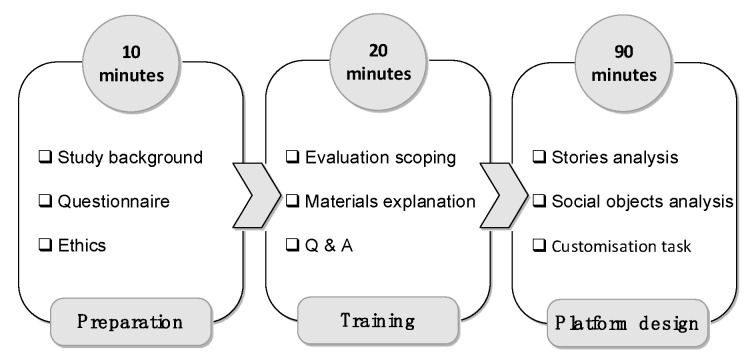

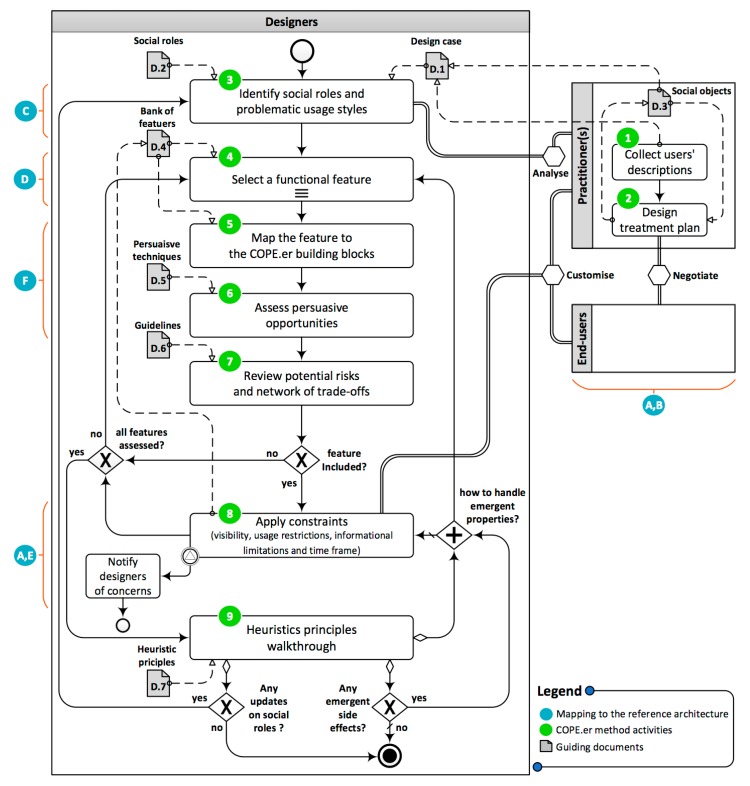

The first phase involved designing a prototype online platform for peer groups for the given case study. The goal of this phase was to investigate how the participants collaborate to design a valid and adequate platform for the given peer group without the help of a designated method. Participants during this phase were not provided with the proposed method. Then, those who played the role of designers were asked to perform the design process including the interaction with end-users and a counsellor. At this stage, the interactions were not restricted and controlled, i.e., the designers decide for themselves when and how to interact with other participates and also decide what to ask. The protocol of this phase is illustrated in Figure 1.

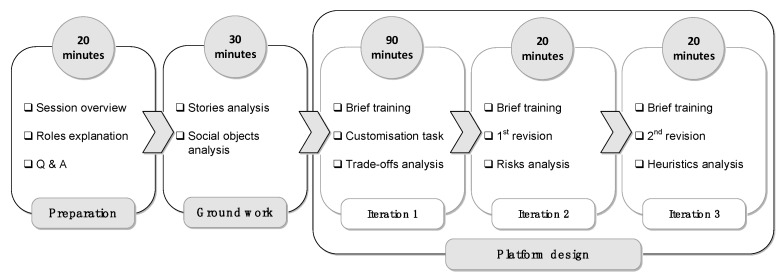

The second phase had the same goal of the first phase but was conducted with the aid of our proposed method which will be introduced in Section 5. This phase was focused on consolidating the understanding of how online platforms for peer groups can be designed from different perspectives, (i.e., counsellors, end-users and designers). Also, it helped in identifying further insights to improve the method artefacts. The protocol of this phase is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Case study first phase protocol.

Figure 2.

Case study second phase protocol.

In both phases, the research facilitator provided the following set of guidelines to collect insights on how decisions are made with and without our proposed method:

The designers were required to read the description of each fictional member, i.e., persona, and try to identify social roles, usage styles, general behaviours and any other aspects may have an influence on the design in terms of what features should or should not be offered to the group and how to combine and configure them.

The COPE.er method is expected to be mainly used by designers in a design process which also involves end-users and counsellor(s), i.e., a designer-led process.

All participants were informed in advance to the sessions about the other participants and their roles and expected contribution.

In the first phase, i.e., without the help of the proposed method, the designers were expected to lead the process and try to involve and utilise other participants the way the designers see appropriate. In the second phase, i.e., with the help of the proposed method, guidance on how to involve and utilise them was offered.

In both phases, the participants were provided with the same interfaces mock-ups to facilitate the discussions. The interfaces depicted an initial prototype for an online peer groups platform.

Participants who were assigned to play the role of end-users were given the six members stories three days in advance. They were asked to read the description of each client and select one to roleplay it in both phases. They were also asked to read the descriptions of the selected members and try to simulate the effects that the addiction had on their daily life. They were also asked to be prepared for any question the designers or the counsellor may ask.

In [79], we provide detailed procedures on how the proposed method, (i.e., COPE.er) was evaluated.

3.2.3. Data Analysis Approach

In this research, we adopted the qualitative content analysis approach to collect insights from the observational data. Content analysis is a qualitative-based research method concerned with producing new knowledge through a systematic analysis process of information coming from different sources, e.g., interviews, printed publications, broadcast programmes and websites [84]. It is defined by Hsieh [85] as “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns”.

Among the three approaches to content analysis, i.e., conventional, directed and summative [85], the conventional approach was adopted. In the conventional approach, the data are analysed to derive coding categories in order to describe the phenomenon. It can be used when there is a lack of theories that explain the captured events. Based on the relationships between the articulated categories, a researcher might combine and re-organise them. With this approach, it is also essential to address relevant theories or other research findings in the discussion part of the study.

To enhance the credibility, the third author of this paper has overseen the observational studies and the analysis and provided feedback on the conduct and results throughout the research. This author has been in recovery from addiction for 30 years, worked on the creation of an organisation to provide rehabilitation from addiction, built up that organisation over the past 28 years to where it now. This organisation provides treatment for up to 54 clients at a time and is recognised by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) as going above and beyond in the provision of treatment. In [79], we present the analysis of the case study used to evaluate and consolidate our proposed method.

4. COPE.er: Stages and Design Principles

Part of the results in relation to the two observational studies was published in [20]. This included the social roles and the tasks performed in online peer groups, the tunnelling process and the different transitions in group work, finally a revision to the Honeycomb Framework [72]. In this paper, we will present the rest of the key findings which constitute the rest of the artefacts of our proposed method. This section starts with introducing two main set of results obtained through the observation study. The first is the primary processes identified which have been grouped into the formation phase and the acting phase processes. The second is a set of derived design principles to aid the design process of online platforms for peer support groups to combat DA.

4.1. Formation Phase Processes

This phase focuses on the preparatory measures to form peer groups and manage them effectively, as well as to ensure groups optimal performance.

4.1.1. Assessment Processes

In the assessment stage and before permitting patients into the peer group therapy and beside the close scrutiny in relation to assessing the problematic behaviour, patients are evaluated thoroughly against certain motivational conditions including: (1) the desire to change, (2) readiness for that, (3) the stage of recovery and (4) the level of dependence. In substance addiction, part of these assessments is performed by a qualified medical doctor. Generally, patients should be joining peer groups on a voluntary basis to maximise the chance of their recovery and also to avoid disrupting others and creating negative group experience.

The assessment also covers the aspects that may influence the treatment programme, e.g., cross-addictions. For instance, a person with smartphone and social network obsessive usage could replace, or even have at the same time other kinds of addictive experiences, such as problem gambling or compulsive online shopping.

The rehab centre used to apply assessment activities iteratively for the purposes of educating patients. This was through the use of self-governed instruments such as the Assessment of Warning signs for Relapse (AWARE) scale [86] which was designed to predict the occurrence of relapse [87]. This family of assessments aims at educating individuals through guiding them to explore past experiences, i.e., warning signs and internal reactions to them, and develop self-management strategies for them. For example, when a group member selects a warning sign like “Confusion and overreaction: difficulty in managing feeling and emotions”, then with the aid of the given materials, the member can find out their more refined and subtle signs and emotions such as: (1) “I feel that nobody would care if I tried to explain what made me unhappy”, (2) “I feel scared to socialise” (3) “I isolate myself” (4) “I start bringing irrelevant problem to hide the main issue which was in that case, why nobody cares?”. As such, this assessment exercise teaches members to identify the profound and preliminary signs before the main one takes place. The goal is to help patients to avoid relapse before it takes place. This indicates that self-help and confession are essential design principles for online platforms, where patients themselves should contemplate and state the signs. This active role of patients shall have a positive impact on their ownership of their recovery process and goals.

In relation to assessing recovery, i.e., on how to distinguish whether a patient is clean or fully recovered, counsellors consider that “experts never know but just judge that through behavioural patterns”. Here, Here, it seems more important to have a growing amount of evidence that indicates users’ commitment to apply relapse prevention plans and strategies as well as learn effective coping skills. This would help when addictive behaviours take place outside the system environment which makes monitorability more complicated, if not impossible. In DA, this may be the evidence stage where the recovered people may take pictures of social activities and share them with the rest of the group and set up timeframes and usage targets, e.g., in terms of time, location, type and frequency, and adhere to them in a sustainable style.

We conclude that the assessment can be performed as a mixture of self-diagnosis, confession and help-seeking from the patient side and offering tools to facilitate that. The items listed in the AWARE scale proposed by Miller and Harris [86] can help the relapse prediction on online medium, e.g., having trouble in sleeping, self-pitying conversations, overreaction (e.g., through the use of Emoticons) and impulsivity, being always focused and engaged in one activity, and having no clear plans or targets.

4.1.2. Matching Processes

In the treatment centre, patients with different addiction themes, e.g., gambling and substance addiction, were offered close principles and treatments. That was under the assumption that addictive behaviours share common variables in terms of initiation, maintenance and symptoms. However, there were parts of the programme which offered to target specific symptoms and behaviours. For example, anger and depression would need further therapeutic treatments, such as emotional support, anger management, changing thinking styles or even teaching some social skills. Such extra treatments can be offered in one-to-one counselling settings following the Motivational Interviewing approach. This suggests that different behavioural themes may require different treatment approaches.

Procedures for permitting patients into a group seems to ensure having a similar need(s) among all members as an essential element for better group performance [88]. However, homogeneous groups can still provide further persuasion effects. Homogeneity refers to the demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, and the ethnic group) which can help to increase receptivity to change and perhaps minimise denial. An important aspect of matching is the eventual move of users amongst different groups as they progress in the treatment, including the alternation of the participation in more than one group based on users’ needs.

In the case of relapsing, a patient must be assigned to another group. In the rehab centre, the policy stresses the need for this procedure to ensure that other patients understand that relapsing is intolerable to avoid negative reinforcement for them. Overall, patients shall recognise the importance of continuing working in their original groups as this typically provides them with more comfort and emotional support. As such, moving a relapsed member to another group can be perceived as an undesirable consequence.

To sum up, matching users to a group in the online medium may consider shared characteristics such as addiction theme, similar life experience, shared needs, demographic data, and treatment stage. This is to maximise the engagement and shared interest in the group and also avoid heterogeneity effects, such as misunderstanding and conflicts since the resolution strategies are limited in online platforms. Hence, members can easily leave if they feel discomfort or pressure.

4.1.3. Preparation Processes

The rehabilitation centre divides treatments into primary and secondary classes. Primary treatment is for patients who are most vulnerable and where extra safety measures need to be applied. In secondary treatment, patients are offered psychological counselling and complementary coping skills. This may include addressing different obstacles, e.g., lack of important social skills needed in group settings. In the case of DA, this may be manifested through obstacles that may lower performance, such as lacking the experience of using certain features in online communication in the right style and failing to use a mutually accepted language when communicating with peers. The case of DA could also relate to the avoidance through living an online persona different from the actual self just to feel being accepted in some communities. The primary and secondary treatments could also be offered based on the severity of the problematic behaviours. For example, stricter measures (e.g., consent monitoring for members’ social network accounts as a part of the primary treatment protocol) are applied at the initial stages of the treatment.

Preparation is mainly concerned with preparing patients to join a group or to increase the performance after assigning them to groups. As explained in the matching stage (Section 4.1.2), this may include additional treatments such as anger management and impulse control. This is mainly for paving the way for the underlying issues to be known and then addressed and rectified when possible. Detoxification, for example, can be seen as a part of the preparation as by the end of it, addicts can pinpoint more fundamental reasons for their addictive experience.

It is important to provide descriptions of these processes from peer groups perspective. In the preparation stage, a fundamental part is to provide and apply briefing procedures in which patients are formally informed about the rehab routines, rules and guidelines for the treatment. Also, at this stage, prescribed detox plans are designed. It was observed that patients in detox can still join group sessions. Generally, detoxification is not part of the group therapy, but it can be integrated to it based on the policy of counselling service providing the treatment as well as based on the level of dependency and withdrawal symptoms of a patient. This is in line with the fact that group therapy is a reinforcement and supportive tool rather than being itself a primary treatment. In other words, the patient who is in the detoxification phase can join the group therapy if that is not going to introduce the risks of sabotaging the group work and even the treatment environment.

Generally, mixing senior peers with new members who might be in the detoxification stage can provide good behavioural change opportunities for both. New members can benefit from being with their senior peers who passed the detoxification stage (i.e., hope installation). It can also introduce them to the norms and good practices in the forthcoming stages of their treatment. However, in terms of designing online platforms for peer groups, this may suggest allowing controlled interactions for such users, e.g., giving them read-only permission in the group. Senior peers can also benefit from such setting as helping others can reduce and resolve behavioural ambivalence [53].

4.2. Acting Phase Processes

This phase focuses on the aspects related to the governance and moderation practices in peer groups. These aspects play a key role to effectively operate group work.

4.2.1. Ongoing Assessment

The treatment provided in the observed groups followed a nonlinear approach and was a subject to ongoing evaluation to address the next treatment requirements and corrective measures. Ongoing assessments seem to look at both distal and proximal goals.

Distal goals are more focused on long-term progress mainly toward a balanced lifestyle as a main indicative measure. As addiction is about losing that balance, the degree of recovery can be assessed based on regaining it. In recovery performance assessment, it seems more appropriate to consider this aspect as a distal goal (i.e., advanced stage of recovery).

Proximal goals are also part of the recurrent assessment. Patients in the rehab centre decide their own specific, measurable, agreed upon, realistic and time-based (SMART) goals on a weekly basis. The selected goals can be simple ones, such as going to the gym or reading a book. An essential aspect of goals selection is that goals should encourage the performance of the healthy and balanced lifestyle tasks which addicts used to neglect or avoid. There are two main purposes of setting proximal goals. The first is to “teach members that they need to have the right goals, learn how to decide them and to be achievable in a week”. The second is “to enhance their self-esteem (through the accumulation of success)”. The activity of goals selection is done collectively where each group member can have only one goal. Typically, a therapist guides this process to ensure selecting the right goals. However, in the case of peer-led groups, i.e., where no therapist is involved, the group should help a member in selecting a goal “because the group may know better than what an individual addict knows as the addict will be stuck in his/her own behaviours”. There is a risk here of some members being stigmatised after repetitive failure or indeed accepting being little efficient if the process of the group is not observed.

4.2.2. Membership Duration Decisions

The patients of the centre are recommended to stay in the treatment for three to six months. This indicates that behaviours of people with severe cases may need an extended period to be influenced, i.e., moving from awareness stage to adopt new healthy behaviours and maintaining them. This should inform assessment processes and feedback messages to avoid any deceptive labels related to the progress of the treatment.

The counsellor highlighted an important consideration in which behavioural change applications are not expected to maintain positive change in severe addiction cases. This is unless patients are encouraged and supported to participate in the wider community beyond their peer groups, for example, through employment opportunities to sustain positive outcomes. Therefore, such a part should be addressed in aftercare treatment where formal group sessions are less essential compared to semi-formal sessions to help patients finding and defining a focus as a purpose in their life to maintain recovery. This may suggest extending the membership to the aftercare stage, where joining group sessions is less essential, but monitoring may still be needed. This also suggests that online platforms for peer groups shall be seen a temporary platform and a part of a more holistic socio-technical process involving other stakeholders, e.g., schools for children with compulsive gaming experiences to integrate them again in class activities and after-school clubs.

4.2.3. Moderation

In peer groups, some forms of interactions should be highly controlled. Private communications are generally discouraged during primary treatment. The treatment centre strives to prevent patients from staying alone without having one of the staff around during the formal sessions and even after that. In addition, deep intimacy and relation are also discouraged to avoid distraction from the main goal and creating a parallel experience. Patients in the residential rehab are “expected to meet in the café and other public areas and not allowed to go to each other rooms”. In conclusion, the relation between members should be moderated to prevent both isolation and deep intimacy and keep the focus on the treatment and behaviour change. On the other hand, during secondary treatment, members are encouraged to attend self-help groups and make friendship relations to help support them after treatment.

Moderation shall also be concerned about the possibility of relapse. The counsellor explained that one of the warning signs of relapse is “avoidance and defensiveness” in which an addict feels worried about others instead of self. That was also found in the materials used during the exercises performed in the sessions of the residential rehab centre. Regardless of whether avoidance is intentional or not, it is still seen as a risk factor and should be avoided and addressed by moderators.

Also, socialisation with people who are not part of the treatment may not be advised in the initial stage of the treatment, again, for the same purpose of helping members to focus on the recovery goals and treatment journey. The counsellor pointed out that this rule is mainly in primary treatment to ensure the safety of the patients as they are under the centre responsibility. The counsellor also highlighted that such policy is often applied by centres whose treatment programmes are based on the 12th steps programme of Alcoholic Anonymous (AA). The AA is a programme that provides a set of addiction recovery principles which includes admitting being powerless over addiction, examining past errors, and personal inventory of defects and successes [89]. This shows that residential treatment centres require a high level of moderation which may be difficult to replicate on the online medium. This is another reason for limiting the applicability of our proposed method to cases where people suffer moderate problematic online usage and in a status where they already admit the issue and seek voluntarily for help.

The observations also suggest that enabling peers to judge and confront each other during groups interaction can create a healthy environment. Yet, this needs the moderators’ skills to use these situations to energise group work rather than being primarily about the subject of the argument. As a cost of this openness, the moderator shall enforce a rule that no one crosses the boundaries and hurts peers’ feelings. In face to face interactions, the role of the moderator is very important to govern the interaction and elevate any negative ones that may occur. The interviewed counsellor pointed out that addicts may pay limited attention to the boundaries and norms typically observed by their society. Therefore, part of the treatment is helping them to recognise such boundaries mainly from the perspective of respecting others.

4.3. Design Principles for Online Peer Groups

In this section, we reflect on the above discussion and our previous work on the topic [1,20,81] and derive good practices for the design of online platforms to host peer support groups.

4.3.1. The Receptive Audience Pre-Requisite

In health behaviour change, it is a fundamental prerequisite that individuals are admitting their problematic behaviour and willing to receive help. Yet, there is criticism towards emphasising self-labelling of being addicted as a requirement for treatment, i.e., the absence of this condition should not be seen as an obstacle to optimal treatment [90]. However, it seems that in rehab programmes, counsellors utilise certain principles as an assessment of motivation. In the rehab centre, the addiction counsellor stated that “the only way to help addicts is to convince them somehow to seek help. Unless they seek help, no one can help them at all”. This suggests that admitting the responsibility for the behaviour, both the problematic and the desired, is a crucial motivational principle. There is also what is called dispositional attribution in which a patient relates the responsibility to individual factors rather than external factors. Attributing the behaviour to external factors is perceived as a defensive mechanism in health behaviour change practices [91].

Miller in [90] lists four key motivational principles in the Motivational Interviewing approach: (1) “individual responsibility” to seek help, (2) placing the responsibility on “internal attribution”, (3) recognising discrepancy between addictive behaviour and personal values, goals and beliefs, i.e., “cognitive dissonance”, and (4) “increase self-esteem” via enhancing attributes that increase confidence in own abilities. These key principles are the main areas that counsellors work on to influence a behaviour in this approach. Two important motivational indicators can be elicited from the observational study and Miller’s four principles:

Individual responsibility to seek help.

The individual perception that the change is not beyond personal control.

However, expecting individuals to easily accept the secondary nature of the external factors and the primary nature of personal attributes is often not realistic. The assessment of this level of admittance is essential. In addition, education through the treatment programme should play an important role to help users minimising the belief on the role of external factors which may increase the probability of having long-lasting change [90].

In the case of online platforms for peer groups, it seems that a stage which deals with diagnosing the two motivational indicators shall be introduced and iteratively repeated. This is to avoid negative behavioural change which may require moving backwards into the stabilisation stage where a user needs to be re-assessed to avoid emergent withdrawal symptoms.

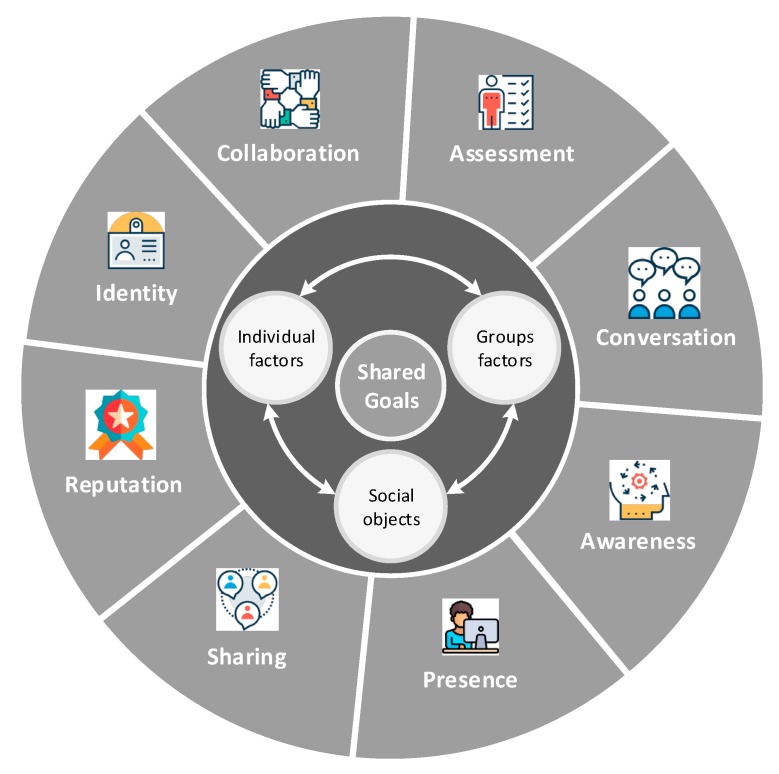

4.3.2. Online Peer Groups as an Adaptive Ecology

We argue that designers of persuasive social software need to be aware of the building blocks which were introduced in the results of our initial analysis of the observation study published in [20]. In order to tailor the design features to optimise group performance, these building blocks should be configured based on four parameters which are the heart of the proposed framework shown in Figure 3. These parameters are: (i) shared goals which are excepted to boost group performance, (ii) group factors, e.g., moderation, governance aspects and group structuring [1], (iii) individual factors, e.g., personal traits, attitudes, preferences and social roles [20], and, (iv) social objects [92], e.g., topics, ideas and events.

Figure 3.

The COPE.er method building blocks.

As an illustration, social roles [20], which define patterns of behaviours that exist in the social structure of small groups, can have different influence not only on that structure and how the group is governed but also on the ecology formation (i.e., what interactive features should be offered). For example, “hope installation” as a task purpose may require some social roles, such as ‘senior’ peers to be introduced to the group in order to increase the persuasiveness of the systems. Those peers are expected to have started gaining control over their use. The system may, also, need to apply some constraints on other roles, such as limiting the sharing features for those playing the ‘relapsed’ role especially when they also play ‘dominant’ or ‘crisis’ roles. It should be noted, that some roles are not primary, but emerge from other existing ones, e.g., the ‘withdrawing’ role may be a result of having dominant users in a group. They may also emerge due to the formulation of the tasks. For example, in a very competitive task, where there might be a user taking the ‘in-detox’ role, the other members of the group may start blaming that peer for poor performance. Consequentially, the ‘scapegoating’ role emerges. Generally, these roles can help or hinder group performance. Some roles may convey positive meaning to group work, e.g., ‘helper’ and ‘sociable’, while others convey the opposite, e.g., ‘dominant’ and ‘scapegoating’. However, all these roles might be, eventually, needed for counsellors to create more effective group functioning.

These dimensions place different emphases on the interaction styles within the rehabilitation activities. In addition, they also influence what functionalities could support various tasks and purposes [20]. This suggests that the ecology of the online peer groups should be adaptive to emphasise different functional settings during the lifetime of the group. This could be achieved by applying different configurations of the honeycomb framework based on the specifications of the tasks, i.e., task purposes, qualities, and functionalities [20]. For example, some tasks and activities run on a rolling basis over a period of three months. After that, the platform should adapt to the expected changes in the individual behaviours and group performance.

In online peer groups, certain building blocks need to be emphasised based on the four parameters in the heart of the model in Figure 3. For a particular activity, the development team of the online version of peer groups, which may include, for example, therapists, software engineers, developers and stakeholders, should emphasise certain blocks but not others to boost the persuasiveness effect. For instance, it was observed in the study conducted in [20] that over a period of 6 weeks, the activities performed in the second group in the face-to-face rehab centre required a minimum opportunity and length of conversations. In online peer group platforms, if a system was highly emphasised by the conversation block in Figure 3 through the implemented features, the members’ performance would be negatively influenced, and facilitators would not be able to obtain optimum outcomes. In this particular scenario, the design of online platforms for peer groups should have the ability to reconfigure the ecology and adapt to different activities requirements which change as the treatment progress. As such, applying a static ecology approach, such as in traditional social networking services, e.g., Facebook and LinkedIn, may hinder the outcomes of the whole system and create rather a negative experience, e.g., a fake sense of achievement, lack of interest and digression.

5. COPE.er: A Novel Method to Design Online Peer Groups Platforms

This section starts with an introduction to the COPE.er method then continues with describing its reference architecture and supported artefacts, followed by the method workflow.

The COPE.er is a participatory method that aims to build Customisable Online Persuasive Ecology by Engineering Rehabilitation strategies for peer groups. The method provides a clear structure and logic to the relationship between design decisions and intended functionalities. It also promotes participatory decision making by involving end-users in the design activities. However, guidelines and heuristics are also provided to frame and regulate that participation and detect and handle its potential side-effects.

Customisable ecology in this context is an enabler to the online social medium that supports the adaptation of its scope, functionality, and persuasive strategies that helps to adequately cope with different group aspects, e.g., groups’ needs and progress in the rehab programme as well as governance management of groups. Media Ecology was formally introduced by Postman [93] as a way of looking into: “how media of communication affect human perception, understanding, feeling, and value; and how our interaction with media facilitates or impedes our chances of survival. The word ecology implies the study of environments: their structure, content, and impact on people”.

The goal of the COPE.er method is to address the challenges in designing such social networking platforms meant for combatting addictive behaviour in general and DA in particular. The COPE.er method is grounded in an extensive empirical research conducted by the authors which was itself informed by established theories in behaviour awareness and behaviour change and addictive behaviour [1,11,20,81]. The findings need to be further validated to be useful in creating effective online peer groups platforms as COPE.er is not meant to give a full specification and sharp rules on how to design the platforms and how to run the groups. Instead, it is meant to highlight phases and constituents to consider and to further customise and engineer through a participatory process. However, when evidence was obtained, we were also in the position to provide certain heuristics and best practices without a claim of completeness in that aspect.

COPE.er considers online peer groups as a specialised and domain-specific form of online social networking services. Thus, the classic Honeycomb framework proposed by in [72] would need a revision to take a decision on its fitness to this specific purpose and whether we need to refine it further or even add new blocks if needed. The COPE.er model proposes a revised version of the Honeycomb framework which matches the characteristics of peer group especially in relation to interaction, e.g., economise and optimise interactions in specific tasks and targets, and membership, e.g., screening and adherence, as well as the assessment of goals progress and its reflection on the personal and group awareness.

For example, ‘goal progress’ as a software feature is associated with the ‘assessment’, ‘awareness’ and collaboration which are new and essential building blocks that we propose through COPE.er to build online peer groups. A designer highlighted that ‘goal progress’ feature, for example, have a direct influence on the social awareness. For instance, having a peer who achieved excellent progress in a certain task(s)-oriented goals, can enhance social awareness and provide collaboration opportunities, e.g., those with low progress in these tasks can seek their peers’ help and support. Hence, it can indirectly influence the collaboration block. Then, they found it positive and more persuasive to make the ‘goals progress’ visible to all group members.

As a result, we concluded that online peers support groups should be built upon the eighth building blocks as opposed to the six blocks of the Honeycomb framework. These blocks of COPE.er are depicted in Figure 3. The new model is devised to the support the implementation of online support group platforms.

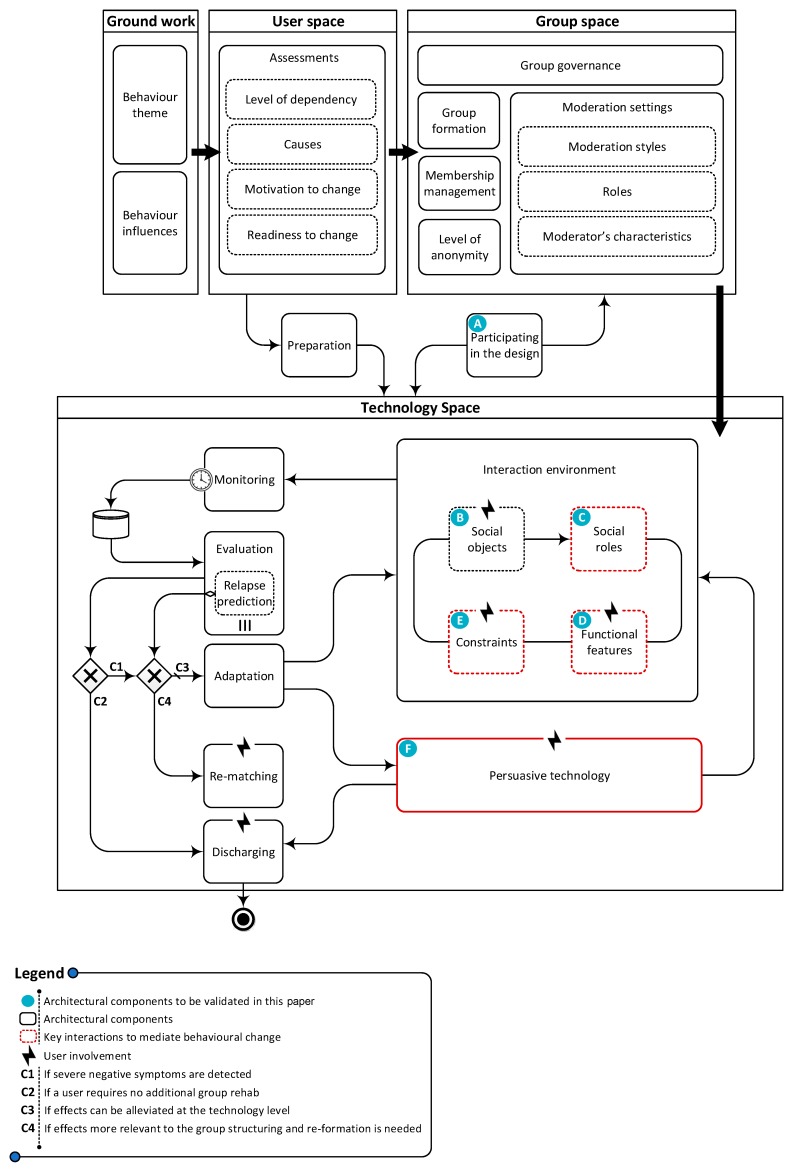

5.1. A Reference Architecture for Online Peer Groups

This section presents our reference architecture (Figure 4) which outlines the main components needed when designing online peer group platforms to regulate DA. This reference architecture has not been published yet, except the current journal. However, the components are published in our previous work which includes: (i) exploring different design aspects related to the “technology space”, mainly for persuasive techniques for E-health systems [81]; (ii) investigating online peer groups in terms of their design as a persuasive technique [1]; and (iii) exploring theoretical aspects of social software design to enable building online platforms for peer support groups as a persuasive behaviour change technique [20]. Namely, these aspects are the social roles played in the peer group and the core principles of considering peer groups as a tunnelling socio-technical persuasive paradigm.

Figure 4.

The COPE.er method reference architecture.

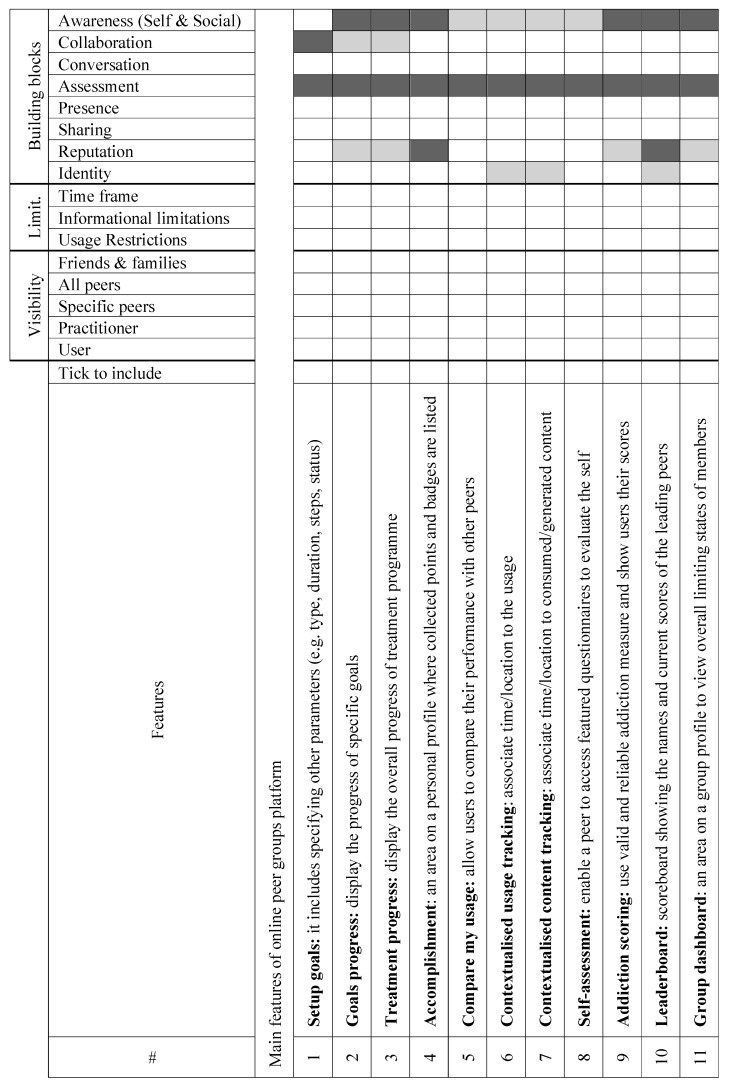

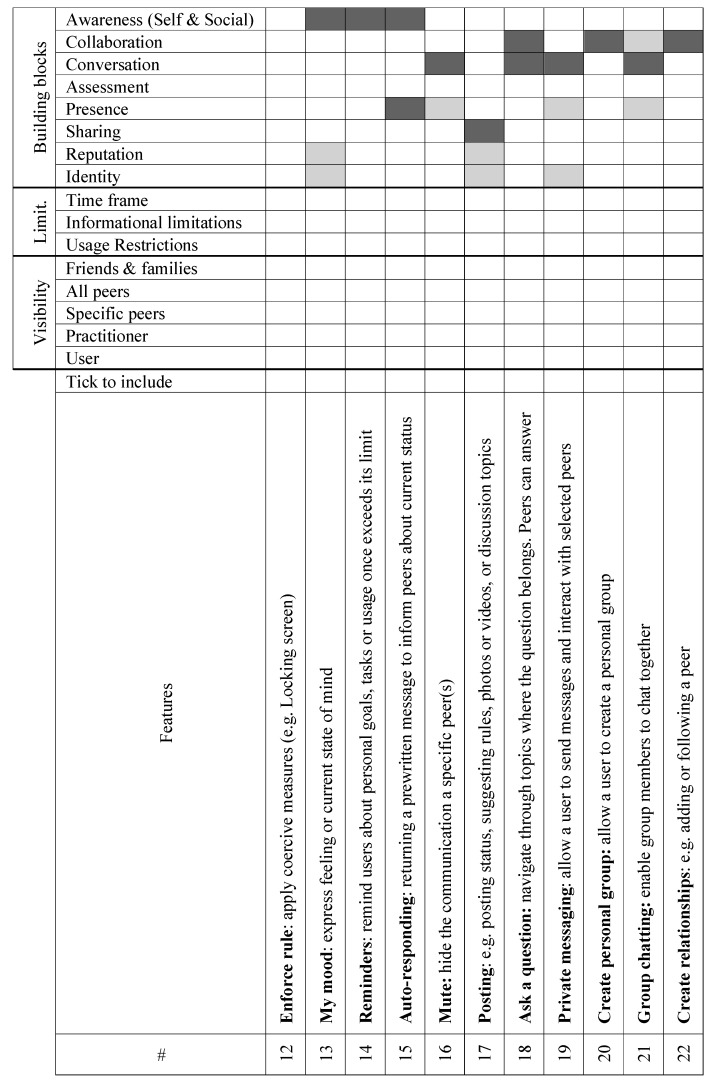

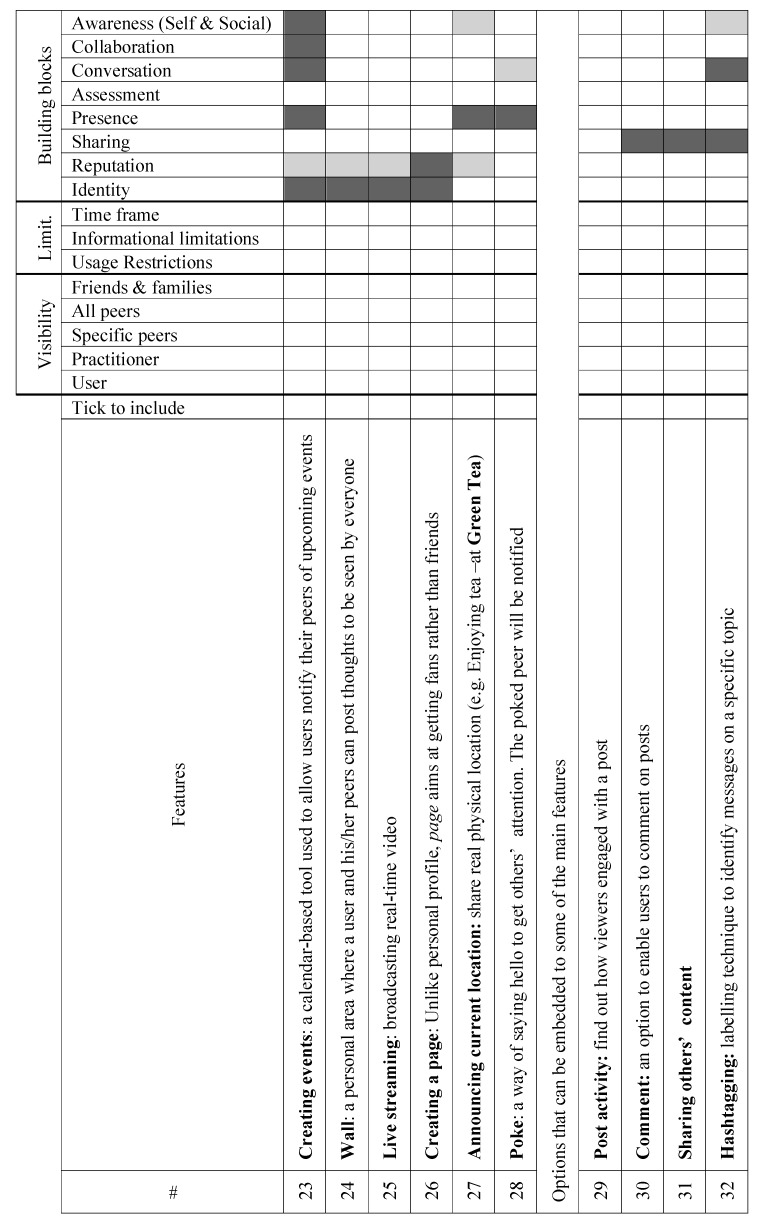

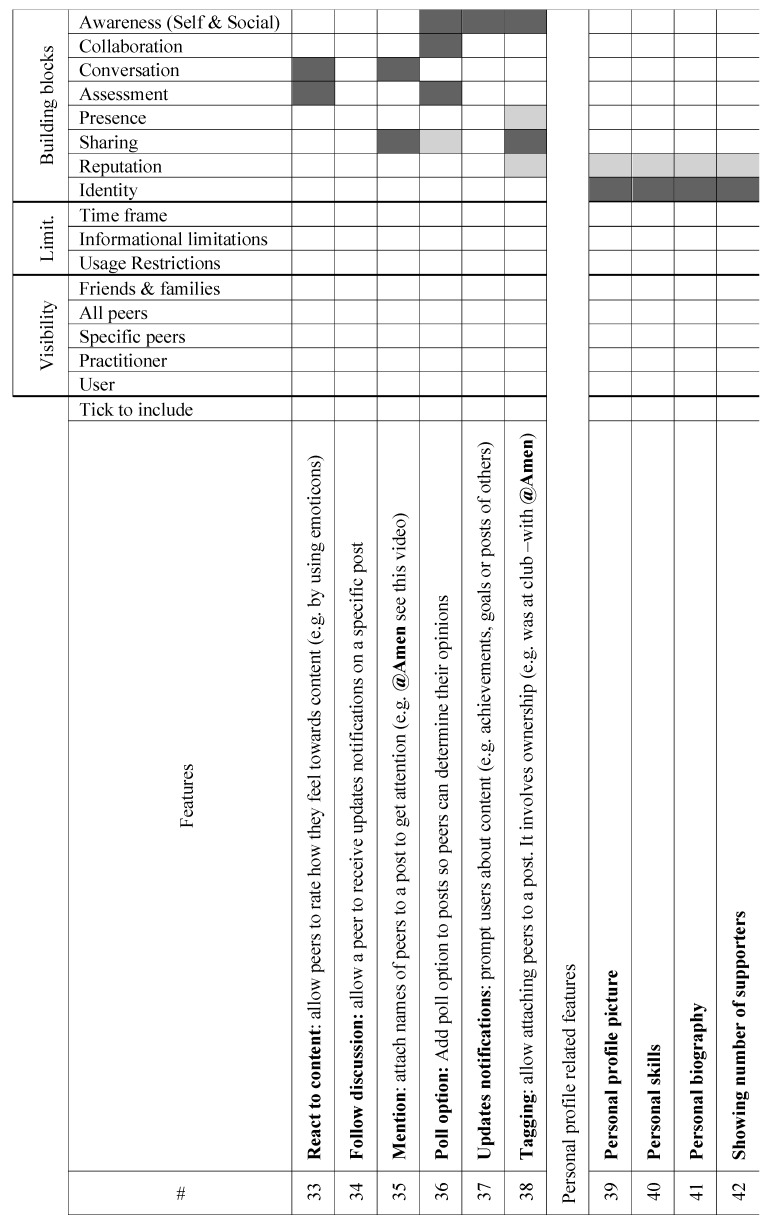

5.2. COPE.er Method Artefacts

The section presents three artefacts developed based on the conducted studies of this research to facilitate the design development and support the customisation of online social platforms of peer support groups. These artefacts are (i) social objects, (ii) functional features, and (iii) design guidelines to build and customise such online platforms to combat addictive behaviours.

5.2.1. Social Objects

Activities and tasks centred on social interactions need to be introduced to the online groups. The method presents these activities as social objects which help to maintain the focus on social interactions. Social objects are expected to be selected by group facilitators and negotiated with representative group members. Social objects encapsulate three aspects:

Purposes: the immediate motivator(s) of the assigned task or activity, e.g., ice breaking, goals setting, hope installation, and emotional support.

Qualities: the interaction orientation that mediates planned purpose(s), i.e., the mode of delivery which can include socialisation, confrontation, competition and collaboration.

Functionalities: the functional activities that support achieving the planned purpose(s), i.e., the method of delivery which can include problem-solving, diaries, stories sharing, and peer pressure such as self-monitoring or surveillance.

The counsellor(s) and end-users can negotiate the treatment plan and decide what tasks and activities are suitable to be introduced to the group within the development team. Usage monitoring and surveillance are examples of core social objects for online peer group platforms that can help to manage the DA behaviours.

5.2.2. Functional Features