Abstract

Background

Adolescent overweight and obesity has increased globally, and can be associated with short‐ and long‐term health consequences. Modifying known dietary and behavioural risk factors through behaviour changing interventions (BCI) may help to reduce childhood overweight and obesity. This is an update of a review published in 2009.

Objectives

To assess the effects of diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years.

Search methods

We performed a systematic literature search in: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, LILACS, and the trial registers ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP Search Portal. We checked references of identified studies and systematic reviews. There were no language restrictions. The date of the last search was July 2016 for all databases.

Selection criteria

We selected randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for treating overweight or obesity in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias, evaluated the overall quality of the evidence using the GRADE instrument and extracted data following the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We contacted trial authors for additional information.

Main results

We included 44 completed RCTs (4781 participants) and 50 ongoing studies. The number of participants in each trial varied (10 to 521) as did the length of follow‐up (6 to 24 months). Participants ages ranged from 12 to 17.5 years in all trials that reported mean age at baseline. Most of the trials used a multidisciplinary intervention with a combination of diet, physical activity and behavioural components. The content and duration of the intervention, its delivery and the comparators varied across trials. The studies contributing most information to outcomes of weight and body mass index (BMI) were from studies at a low risk of bias, but studies with a high risk of bias provided data on adverse events and quality of life.

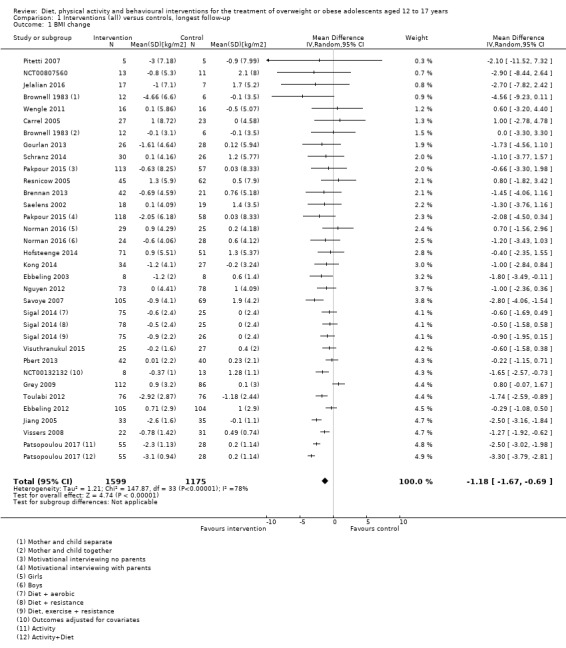

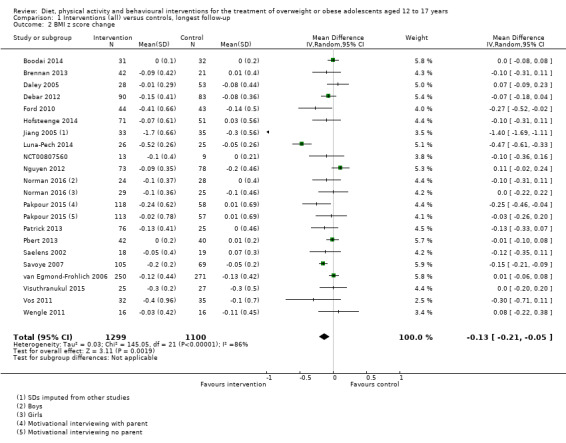

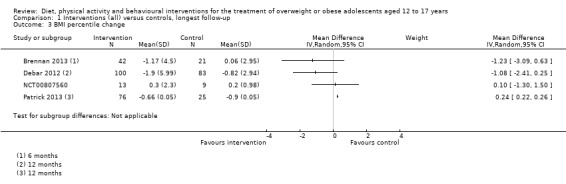

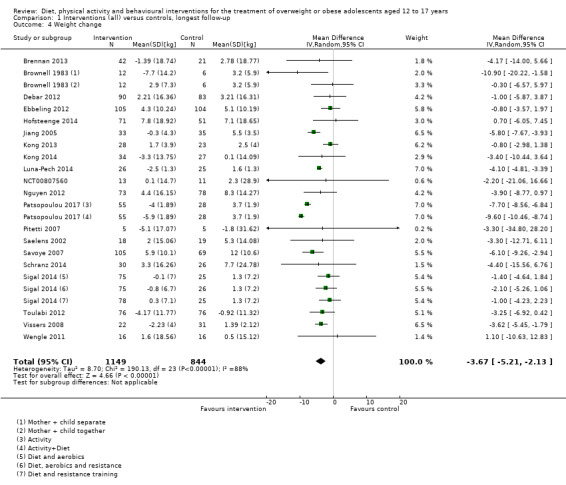

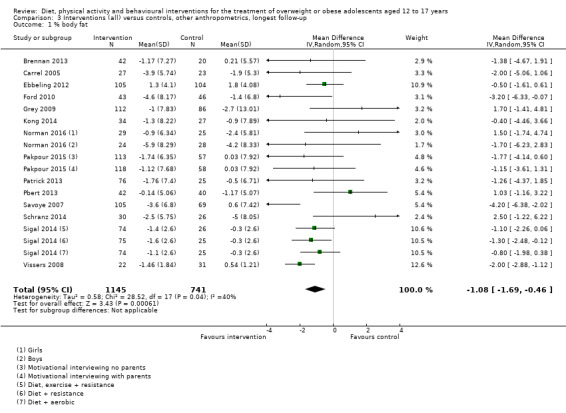

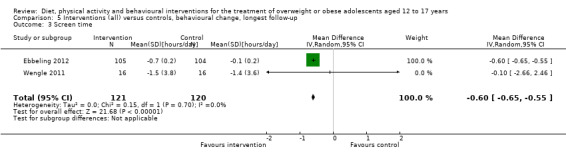

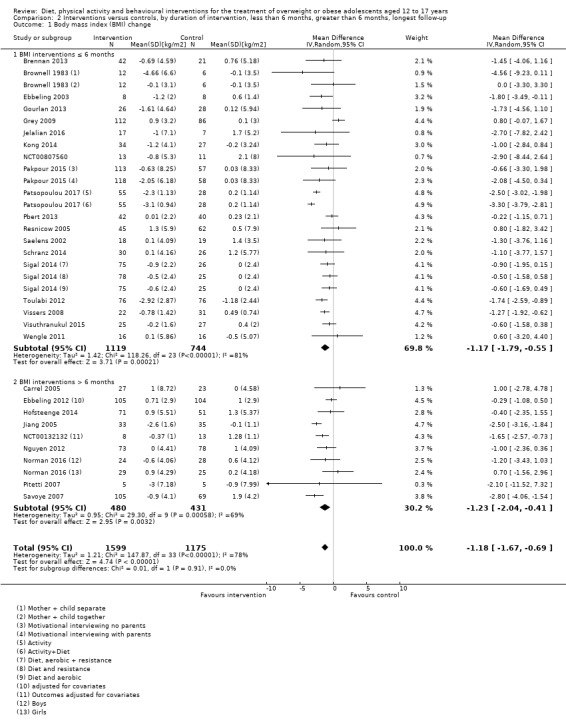

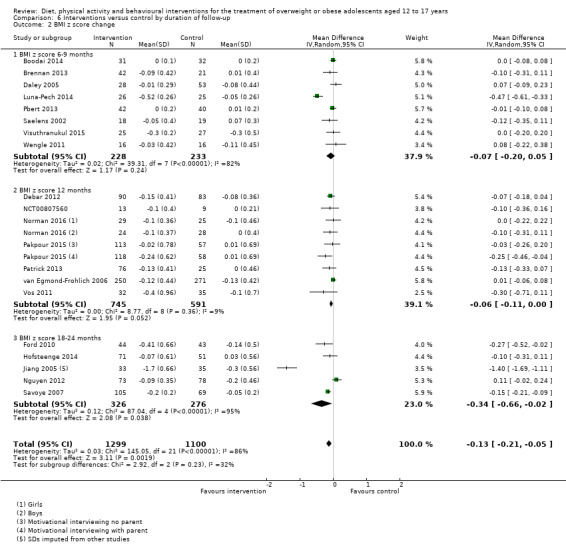

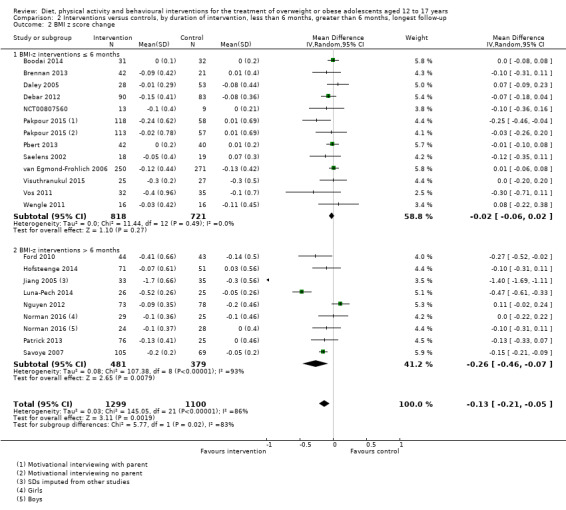

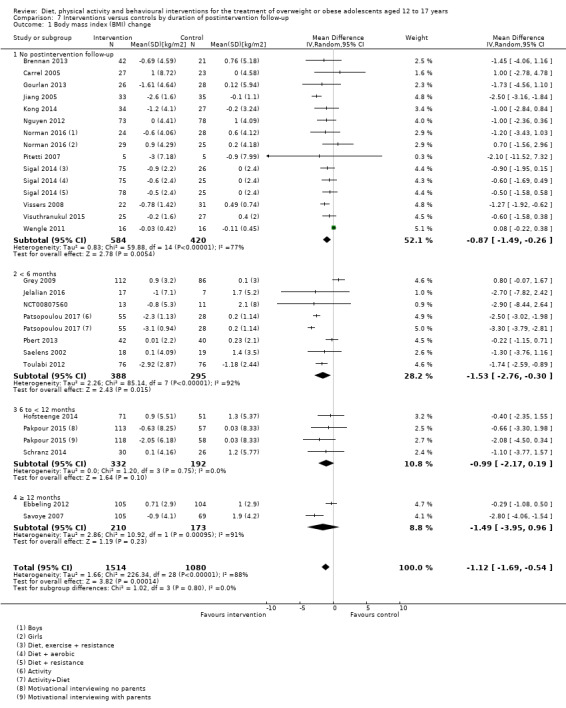

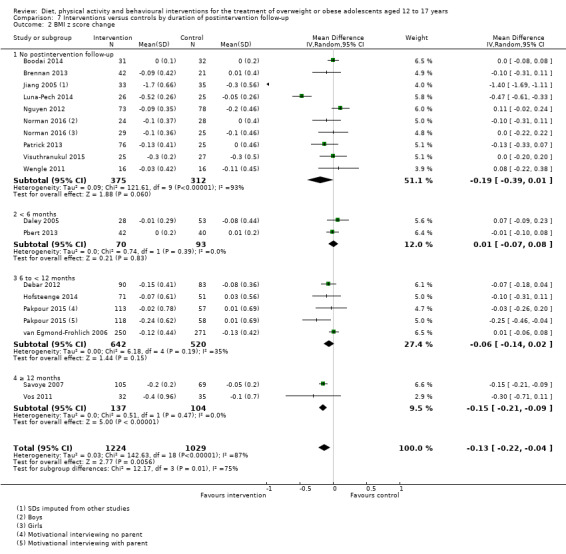

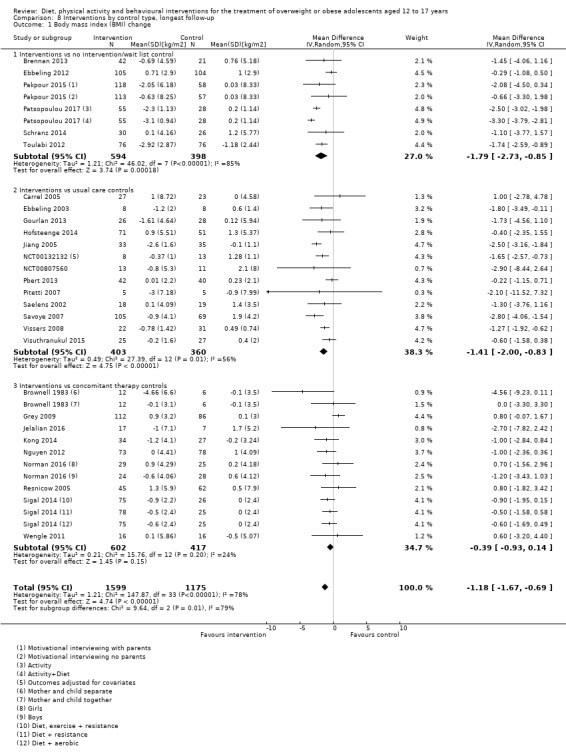

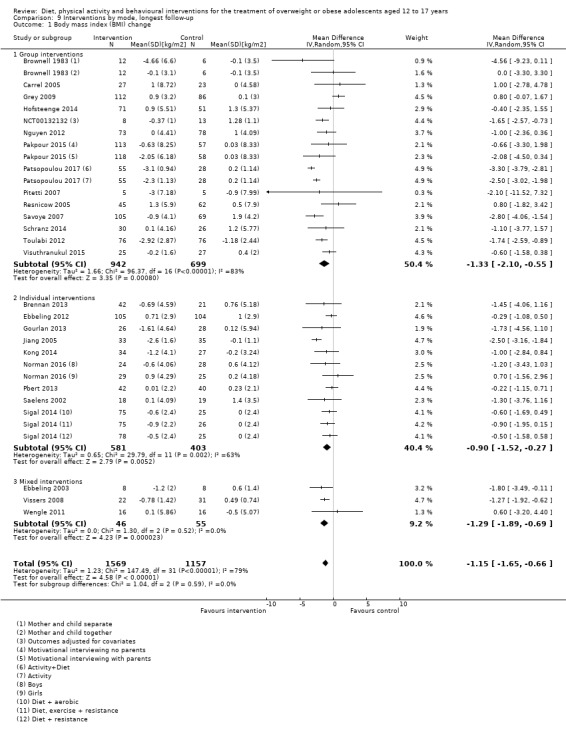

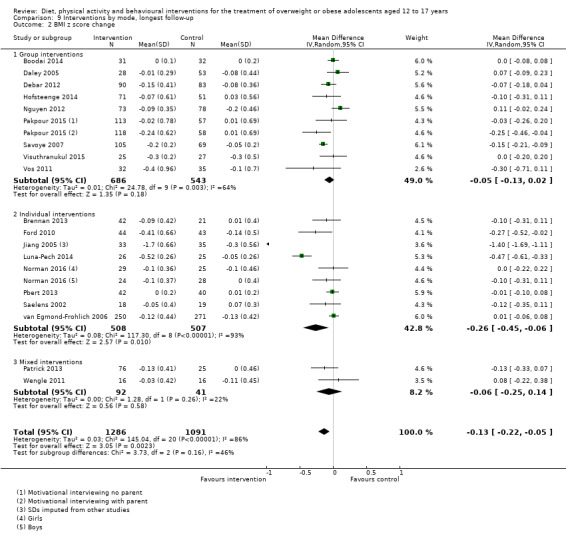

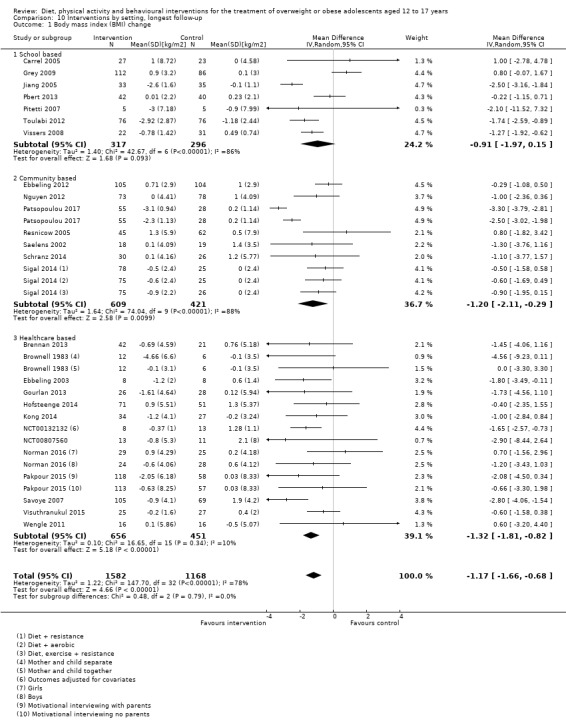

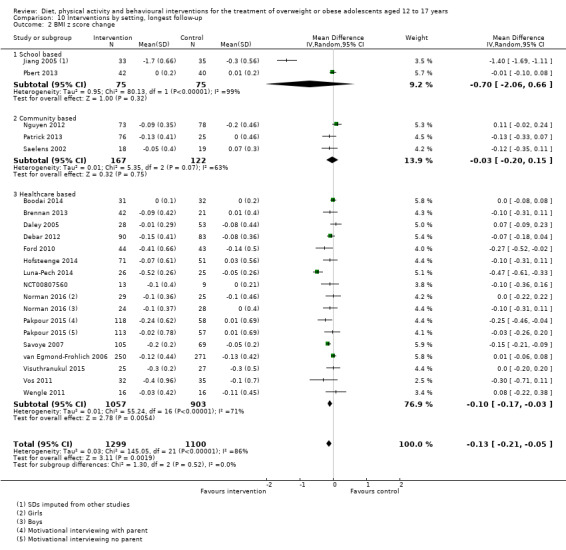

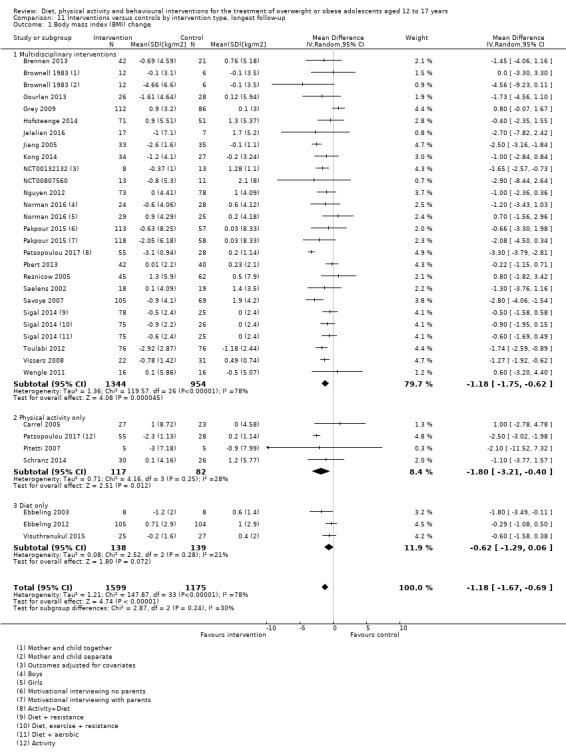

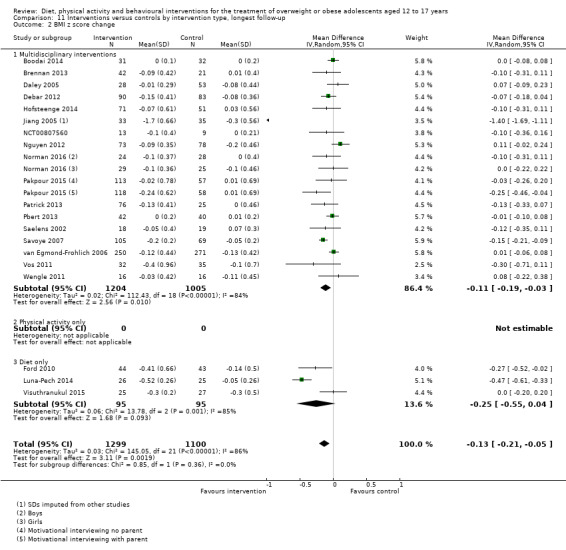

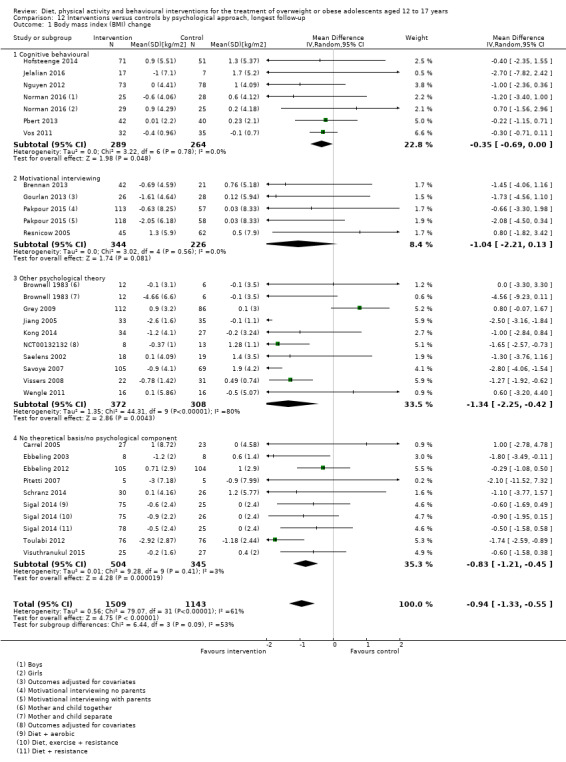

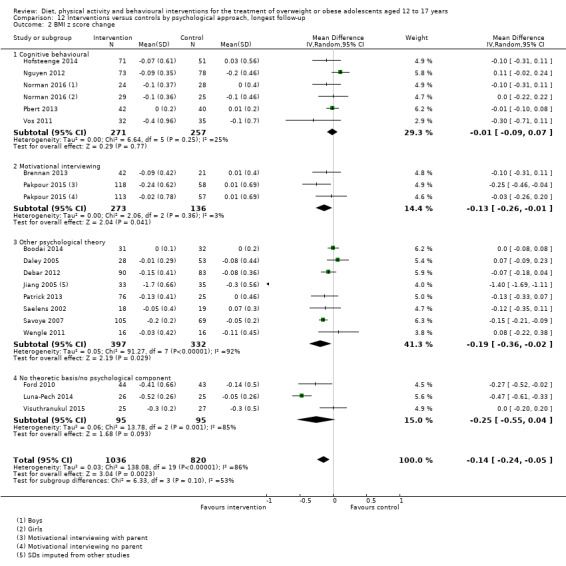

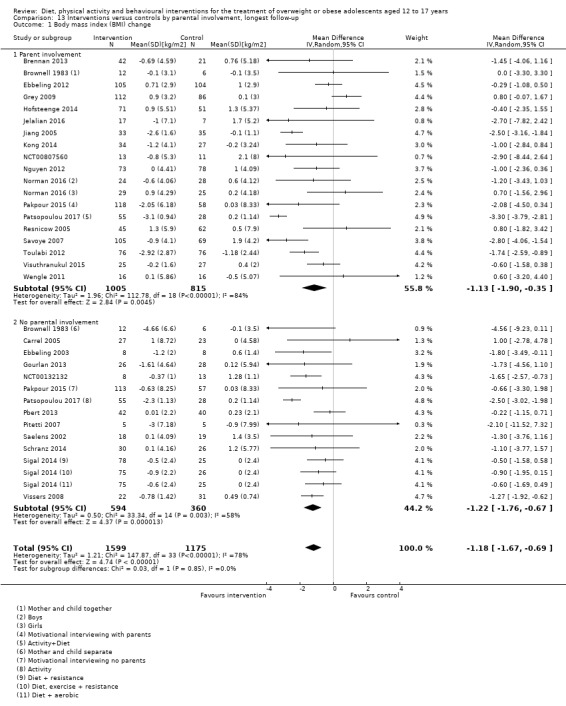

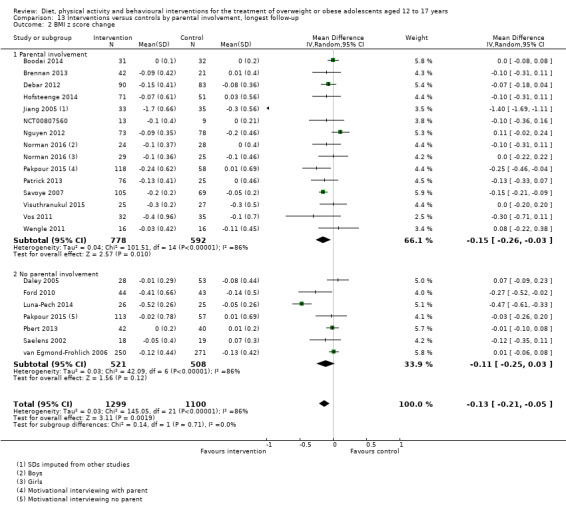

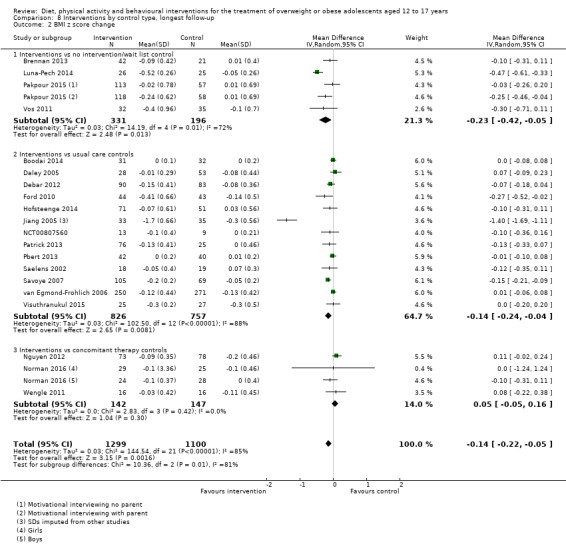

The mean difference (MD) of the change in BMI at the longest follow‐up period in favour of BCI was ‐1.18 kg/m2 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.67 to ‐0.69); 2774 participants; 28 trials; low quality evidence. BCI lowered the change in BMI z score by ‐0.13 units (95% CI ‐0.21 to ‐0.05); 2399 participants; 20 trials; low quality evidence. BCI lowered body weight by ‐3.67 kg (95% CI ‐5.21 to ‐2.13); 1993 participants; 20 trials; moderate quality evidence. The effect on weight measures persisted in trials with 18 to 24 months' follow‐up for both BMI (MD ‐1.49 kg/m2 (95% CI ‐2.56 to ‐0.41); 760 participants; 6 trials and BMI z score MD ‐0.34 (95% CI ‐0.66 to ‐0.02); 602 participants; 5 trials).

There were subgroup differences showing larger effects for both BMI and BMI z score in studies comparing interventions with no intervention/wait list control or usual care, compared with those testing concomitant interventions delivered to both the intervention and control group. There were no subgroup differences between interventions with and without parental involvement or by intervention type or setting (health care, community, school) or mode of delivery (individual versus group).

The rate of adverse events in intervention and control groups was unclear with only five trials reporting harms, and of these, details were provided in only one (low quality evidence). None of the included studies reported on all‐cause mortality, morbidity or socioeconomic effects.

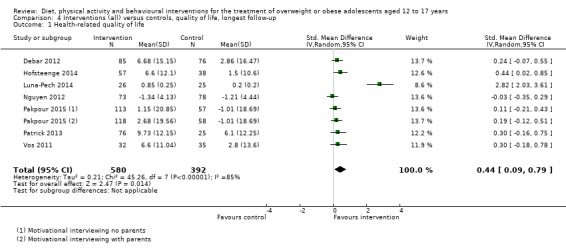

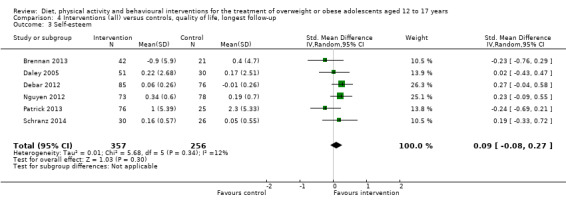

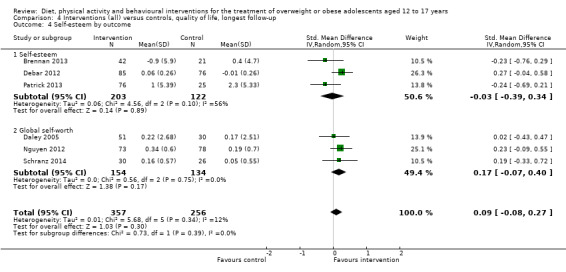

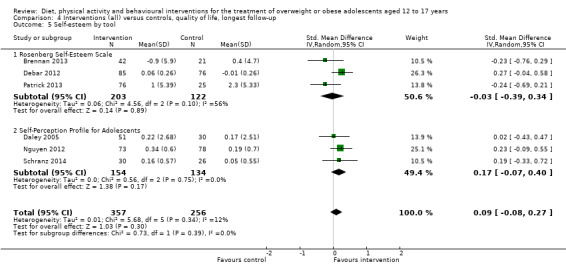

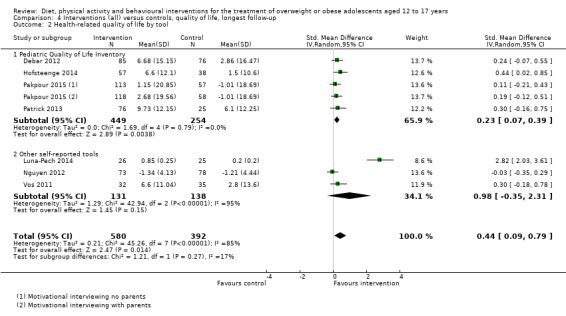

BCIs at the longest follow‐up moderately improved adolescent's health‐related quality of life (standardised mean difference 0.44 ((95% CI 0.09 to 0.79); P = 0.01; 972 participants; 7 trials; 8 comparisons; low quality of evidence) but not self‐esteem.

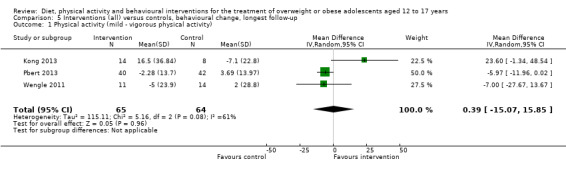

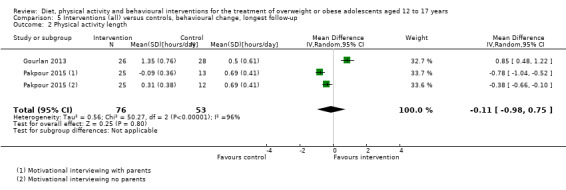

Trials were inconsistent in how they measured dietary intake, dietary behaviours, physical activity and behaviour.

Authors' conclusions

We found low quality evidence that multidisciplinary interventions involving a combination of diet, physical activity and behavioural components reduce measures of BMI and moderate quality evidence that they reduce weight in overweight or obese adolescents, mainly when compared with no treatment or waiting list controls. Inconsistent results, risk of bias or indirectness of outcome measures used mean that the evidence should be interpreted with caution. We have identified a large number of ongoing trials (50) which we will include in future updates of this review.

Plain language summary

Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years

Review question

How effective are diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions in reducing the weight of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years?

Background

Across the world, more adolescents are becoming overweight and obese. These adolescents are more likely to suffer from health problems in later life. More information is needed about what works best in treating this problem.

Study characteristics

We found 44 randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) comparing diet, physical activity and behavioural (where habits are changed or improved) treatments (interventions) to a variety of control groups delivered to 4781 overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Our systematic review reports on the effects of multidisciplinary interventions, dietary interventions and physical activity interventions compared with a control group (no intervention, 'usual care,' enhanced usual care or some other therapy if it was also delivered to the intervention group). The adolescents in the included studies were monitored (called follow‐up) for between six months and two years.

Key results

The average age of adolescents ranged from 12 to 17.5 years. Most studies reported the body mass index (BMI). BMI is a measure of body fat and is calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of the body height measured in metres (kg/m2). We summarised the results of 28 studies in 2774 adolescents reporting BMI, which on average was 1.18 kg/m2 lower in the intervention groups compared with the control groups. We summarised the results of 20 studies in 1993 adolescents reporting weight, which on average was 3.67 kg lower in the intervention groups compared with the control groups. BMI reduction was maintained at 18 to 24 months of follow‐up (monitoring participants until the end of the study), which on average was 1.49 kg/m2 lower in the intervention groups compared with the control groups. The interventions moderately improved health‐related quality of life (a measure of a person's satisfaction with their life and health) but we did not find firm evidence of an advantage or disadvantage of these interventions for improving self‐esteem, physical activity and food intake. No study reported on death from any cause, morbidity (illnesses) or socioeconomic effects (such as days away from school). Three studies reported no side effects, one reported no serious side effects, one did not provide details of side effects and the rest of the studies did not report whether side effects occurred or not.

We identified 50 ongoing studies which we will include in future updates of our review.

Currentness of evidence

This evidence is up to date as of July 2016.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of the evidence was rated as low for most of the outcomes (results) measured, mainly because of limited confidence in how studies were performed, inconsistent results between the studies and the way that some outcomes used do not capture obesity outcomes directly. Also, there were just a few studies for some outcomes, with small numbers of included adolescents.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obesity in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years.

| Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obesity in adolescents aged 12‐17 years | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adolescents (aged 12‐17 years) being overweight or obese Settings: school; community; healthcare Intervention: behaviour changing interventions (behavioural, diet, physical activity (or a combination) components) Comparison: usual care; concomitant therapy; no intervention/wait list | ||||||

| Outcomes | Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Usual care, concomitant therapy, no intervention/wait list | Behaviour changing intervention | |||||

|

a) Change in BMI

Follow‐up: 6‐24 months b) Change in BMI z scored Follow‐up: 6‐24 months c) Change in weight Follow‐up: 6‐24 months |

a) The mean BMI change ranged across control groups from ‐1.18 kg/m2 to 2.1 kg/m2 b) The mean BMI z score change ranged across control groups from ‐0.31 units to 0.13 units c) The mean change in weight ranged across control groups from ‐1.8 kg to 8.3 kg |

a) The mean BMI change in the intervention groups was 1.18 kg/m2 lower (1.67 lower to 0.69 lower) b) The mean BMI z score change in the intervention groups was 0.13 units lower (0.21 lower to 0.05 lower) c) The mean change in weight in the intervention groups was ‐3.67 kg lower (‐5.21 lower to ‐2.13 lower) |

‐ | a) 2774 (28) b) 2399 (20) c) 1993 (20) |

a) ⊕⊕⊝⊝

Lowa b) ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb c) ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec |

a) Lower BMI indicates weight loss b) Lower score indicates weight loss c) Lower weight indicates weight loss |

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe | Only 5 trials reported adverse events and of these details were provided in only 1 showing no substantial differences between intervention and comparator groups |

| Health‐related quality of life Validated self‐reported measures Follow‐up: 6‐24 months | The standardised mean difference for health‐related quality of life ranged across control groups from ‐1.34 to 9.73 | The standardised mean difference for health‐related quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.44 standard deviations higher (0.09 to 0.79 higher) | ‐ | 972 (7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowf | A standard deviation of 0.44 represents a moderate difference between groups.g |

| All‐cause mortality | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Not reported |

| Morbidity | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Not reported |

| Socioeconomic effects | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Not reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) BMI: body mass index: CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to inconsistency (I2 = 78%), one level due to indirectness (surrogate outcome used); see Appendix 9.

bDowngraded one level due to inconsistency (I2 = 86%), one level due to indirectness (surrogate outcome used); see Appendix 9.

cDowngraded one level due to inconsistency (I2 = 96%); see Appendix 9. d"A BMI z score or standard deviation score indicates how many units (of the standard deviation) a child's BMI is above or below the average BMI value for their age group and sex. For instance, a z score of 1.5 indicates that a child is 1.5 standard deviations above the average value, and a z score of ‐1.5 indicates a child is 1.5 standard deviations below the average value" (NOO NHS 2011). eDowngraded one level due to reporting and other bias and limited information (small number of studies and the majority of trials had less than 80% of participants enrolled included in the analysis); see Appendix 9. fDowngraded one level due to reporting and detection bias (no blinding of participants and personnel) and inconsistency (I2 = 85%); see Appendix 9). gA broadly accurate guide of how to interpret the standard mean difference (SMD) is: less than 0.40 = small, 0.40 to 0.70 = moderate, greater than 0.70 = large (Higgins 2011a).

Background

The prevalence of overweight and obese children and adolescents has increased throughout the world, presenting a global public health crisis (Ng 2014; WHO 2015a). Although once considered to be a condition affecting only high‐income countries, rates of paediatric overweight and obesity have started to rise dramatically in some low‐ to middle‐income countries (Wang 2012). Using the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) standard definition, the age‐standardised prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents has increased in both high‐income and low‐ to middle‐income countries since the mid‐1980s (Cole 2000). In 2013, the prevalence of overweight and obese children and adolescents in high‐income countries was estimated at 23.8% (95% confidence interval (CI) 22.9 to 24.7) for boys and 22.6% (95% CI 21.7 to 23.6) for girls. In low‐ to middle‐income countries, the prevalence was estimated as 12.9% (95% CI 12.3 to 13.5) for boys and 13.4% (95% CI 13.0 to 13.9) for girls (Ng 2014). Very young children are also affected. In 2010, de Onis 2010 used the World Health Organization (WHO) growth standards (WHO 2015b) to estimate that over 42 million children under five years of age were overweight or obese, with approximately 35 million of these children living in low‐ to middle‐income countries.

Inequalities in overweight and obesity prevalence have also been documented. Generally, socioeconomically disadvantaged children in high‐income countries (Knai 2012; Shrewsbury 2008), and children of higher socioeconomic status in low‐ to middle‐income countries (Lobstein 2004; Wang 2012) are at greater risk of becoming overweight. However, this relationship may vary by population demographics (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity), and environment (e.g. country, urbanisation) (Wang 2012). The prevalence of obesity varies by ethnicity, with large data sets showing substantial ethnic variation in English (HSCIC 2015), US (Freedman 2006; Skinner 2014), and New Zealand (Rajput 2014) child populations.

While there is some evidence that the rate of increase in paediatric obesity may be slowing in some high‐income countries, current levels remain too high, and continue to rise in many low‐ to middle‐income countries (Olds 2011; Rokholm 2010). However, an additional concern in some high‐income countries such as the USA (Kelly 2013; Skinner 2014), and England (CMO 2015; Ells 2015), is the rise in severe paediatric obesity. While the IOTF published an international definition for severe paediatric (morbid) obesity in 2012 (Cole 2012), often severe obesity prevalence is reported using country‐specific cut‐off points making international comparisons difficult. However, data from the USA (Skinner 2014), and England (Ells 2015), have shown that the prevalence of severe paediatric obesity varies by socioeconomic status and ethnicity, and may result in a greater risk of adverse cardiometabolic events and severe obesity in adulthood (Kelly 2013).

Description of the condition

Childhood overweight and obesity results from an accumulation of excess body fat, and can increase the risk of both short‐ and longer‐term health consequences. Numerous obesity‐related co morbidities can develop during childhood, which include muscular skeletal complaints (Paulis 2014); cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, insulin resistance and hyperlipidaemia (Reilly 2003), even in very young children (Bocca 2013); and conditions such as such as sleep apnoea (Narang 2012), asthma (Egan 2013), liver disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Daniels 2009; Lobstein 2004). The condition can also affect psychosocial well‐being, with obese young people susceptible to reduced self‐esteem and health‐related quality of life (Griffiths 2010), and stigmatisation (Puhl 2007; Tang‐Peronard 2008). Evidence also shows that childhood obesity can track into adulthood (Parsons 1999; Singh 2008; Whitaker 1997), and is therefore associated with an increased risk of ill health later in life (Reilly 2003).

Description of the intervention

Given the serious implications associated with childhood and adolescent obesity, effective treatment is imperative. While the fundamental principles of weight management in children and adolescents are the same as in adults (i.e. reduced energy intake and increased energy expenditure), the primary aim of treatment (i.e. weight reduction or deceleration of weight gain) and the most suitable intervention approach vary, and are dependent on the child's age and degree of excess weight, among other considerations. Behaviour changing interventions combining dietary, physical activity and behavioural components are effective and are considered the current best practice in the treatment of childhood obesity in adolescents under 18 years of age (WHO 2015c).

Adverse effects of the intervention

It is not anticipated that diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions will lead to adverse outcomes. However, as with all obesity treatment interventions in children and young people, potential adverse effects should be considered, including effects on linear growth, eating disorders and psychological well‐being.

How the intervention might work

The cause of childhood obesity is multifactorial, including dietary, activity, behavioural and environmental factors (Orsi 2011). Modifying these factors by behaviour changing interventions is considered the line of treatment of childhood overweight and obesity (Spear 2007). Behaviour changing interventions aim to improve dietary intake, increase activity levels, reduce sedentary behaviour, provide techniques to sustain healthy lifestyle and may have parental or family involvement (Kothandan 2014). Interventions may target one behavioural component (diet only or physical activity only) while other interventions integrate several components (diet, physical activity and behavioural modification) that seem to show promising results in decreasing overweight and obesity in adolescents (Jelalian 1999). Behavioural modification is often based on theoretical elements such as cognitive behavioural theory to help adolescents sustain changes and minimise relapse (Doak 2006). Theory‐based interventions address different elements such as healthy food choices, environmental control, positive thinking and goal‐setting that appear to be linked to positive weight outcomes (Dewar 2013; MacDonell 2010; White 2004). Earlier systematic reviews showed that behaviour changing interventions improved weight reduction in children aged 19 and younger (Ho 2012; Wilfley 2007), while one systematic review by Kelly and colleagues showed that interventions addressing nutrition, physical activity and behavioural skills with parental involvement appears to be an effective way to reduce adolescent obesity (Kelly 2008). One systematic review by Ruotsalainen and colleagues showed that supervised physical activity interventions have a favourable effect on adolescent BMI. Ruotsalainen acknowledged the importance of complex interventions that involve behavioural modification and management in the implementation of physical activity in adolescents (Ruotsalainen 2015), while the effect of dietary interventions remains unclear. One systematic review by Collins and colleagues found inconsistent evidence on the role of dietetic interventions in the treatment of childhood obesity (Collins 2006). However, the length, delivery setting and long‐term effect of behaviour changing interventions in the treatment of adolescent obesity remains unclear (Ho 2012; McGovern 2008; Wilfley 2007). The importance of behaviour changing interventions in treating childhood obesity has led to questioning their effectiveness in adolescents and whether different types of behavioural modification are more effective than others.

Why it is important to do this review

The first version of this systematic review was published in 2003 and included analysis of childhood obesity treatment trials published up to July 2001 (Summerbell 2003). The second version was published in 2009 providing an update to the 2003 review (Oude Luttikhuis 2009). To reflect the rapid growth in this field, the third update to this review has been split across six reviews focusing on the following treatment approaches: surgery; drugs; parent‐only interventions; diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for young children aged 0 to 6 years; school children aged 5 to 11 years and adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. The current review examines the effectiveness of interventions for adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Previous systematic reviews identified gaps in research assessing interventions specifically for this age group (Doak 2006). Other systematic reviews did not focus on adolescents specifically (Ho 2012; Peirson 2015; Wilfley 2007) or focused on specific interventions (Ruotsalainen 2015). This review has extended the evidence base by including trials of any form of behaviour changing intervention aimed to treat obesity in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. It also includes the effect of behaviour changing interventions on other adiposity indicators (e.g. waist circumference, body fat), behavioural change, quality of life, self‐esteem and views of the intervention. The results of this current review and other systematic reviews in this series will provide information on which to underpin clinical guidelines and health policy on the treatment of childhood obesity.

Objectives

To assess the effects of diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled clinical trials (RCT). For cross‐over trials, we only analysed the first phase before cross‐over (if this was six months or more) to avoid the potential of carry over effects. Included studies observed participants for a minimum of six months (this time frame refers to the intervention itself or to a combination of the intervention with a follow‐up phase).

Types of participants

We included studies of overweight or obese adolescents with a mean study age of 12 to 17 years at the commencement of the intervention. We excluded studies of critically ill people, pregnant or breastfeeding women, or adolescents with a syndromic cause for their obesity (e.g. Prader‐Willi syndrome).

Diagnostic criteria

Any method of overweight or obesity classification was acceptable.

Types of interventions

We planned to investigate the following comparisons of intervention versus control/comparator.

Intervention

Any form of behaviour changing intervention with a primary aim to treat overweight or obesity. Behaviour changing interventions included any form of dietary, physical activity, behavioural therapy, or a combination of these delivered as a single or multicomponent intervention, in any setting, using any delivery method and included studies which examined weight loss or maintenance or both.

Comparator

No treatment/wait list control, usual care or an alternative concomitant therapy providing it is delivered in the intervention arm. Concomitant interventions had to be the same in the intervention and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Changes in measured BMI or body weight.

Adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life.

Self‐esteem.

All‐cause mortality.

Morbidity.

Anthropometric measures other than BMI.

Behaviour change.

Participants' views of the intervention.

Socioeconomic effects.

Parenting skill and relationships.

Method and timing of outcome measurement

Changes in BMI (kg/m2) and body weight (kg): measured at baseline and at least at six months.

Adverse events: defined as an adverse outcome that occurred during or after the intervention but was not necessarily caused by it, and measured at baseline and at least at six months.

Health‐related quality of life: evaluated by a validated instrument such as Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory and measured at baseline and at least at six months.

Self‐esteem: evaluated by a validated instrument such as Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale and measured at baseline and at least at six months.

All‐cause mortality: defined as any death that occurred during or after the intervention and measured at six months or later. Morbidity: defined as illness or harm associated with the intervention and measured at baseline and six months or later.

Anthropometric measures other than change in BMI: defined by validated tools such as waist circumference, skin‐fold thickness, waist‐to‐hip ratio, dual x‐ray absorptiometry (DXA) or bioelectrical impedance analysis and measured at baseline and at least at six months.

Behaviour change: defined as validated measures of diet and physical activity and measured at baseline and at least at six months. Participants' views of the intervention: defined as documented accounts from participant feedback and measured at baseline and at least at six months.

Parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting: evaluated by a validated instrument and measured at baseline and at least at six months.

Socioeconomic effects defined as a validated measure of socioeconomic status such as parental income or educational status and measured at baseline and at least at six months.

'Summary of findings' table

We presented a 'Summary of findings' table reporting the following outcomes listed according to priority.

Changes in BMI and body weight.

Adverse events.

Health‐related quality of life.

All‐cause mortality.

Morbidity.

Socioeconomic effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources from inception of each database to 14 July 2016 and placed no restrictions on the language of publication.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2016, Issue 6).

Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) (from 1946).

Embase Ovid (1974 to 2016 week 28).

PsycINFO (1806 to July week 1 2016).

CINAHL.

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database) (last update 8 July 2016).

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/trialsearch/).

We continuously applied a MEDLINE (via OvidSP) e‐mail alert service established by the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group (CMED) to identify newly published studies using the same search strategy as described for MEDLINE (for details on search strategies and search platforms, see Appendix 1). Should we have identified new studies for inclusion, we planned to evaluate these, incorporated findings in our review and resubmitted another review draft (Beller 2013).

If we detected additional relevant key words during any of the electronic or other searches, we modified the electronic search strategies to incorporate these terms and documented the changes.

Searching other resources

We tried to identify other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of retrieved included trials, (systematic) reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports. We also contacted study authors of included trials to identify any further studies that we may have missed.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (two of LA‐K, RJ, EL, JC, KR, CO, LA, EM, LE, HF, JO) independently scanned the abstract, title, or both, of every record retrieved, to determine which studies should be assessed further. We investigated all potentially relevant articles as full text. We resolved any discrepancies through consensus or recourse to a third review author (of KR, EL, LA‐K). Where resolution of a disagreement was not possible, we added the article to those 'awaiting assessment' and contacted study authors for clarification. We present an adapted PRISMA flow chart showing the process of study selection (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

For studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, two review authors (of LA‐K, EL, JC, RJ, CO, LA, EM, KR, HF, RV, MM, JO) independently abstracted key participant and intervention characteristics and reported data on efficacy outcomes and adverse events using standard data extraction templates as supplied by Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group, with any disagreements to be resolved by discussion, or, if required, by consultation with a third review author (KR or EL) (for details, see Table 2; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9; Appendix 10).

1. Overview of study populations.

|

Trial ID (trial design) |

Intervention and comparator | Sample sizea | Screened/eligible (n) | Randomised (n) | ITT (n) | Analysed (n) | Finishing study (n) | Randomised finishing study (%) | Follow‐up timeb |

|

Patsopoulou 2017 (parallel RCT) |

I1: activity | ‐ | 2618/‐ | 60 | 55 | 55 | 50 | 83 | 6 months (after 12‐week intervention) |

| I2: activity + diet | 60 | 55 | 55 | 50 | 83 | ||||

| C1: no intervention | 61 | 56 | 56 | 50 | 82 | ||||

| total: | 181 | 166 | 166 | 150 | 82.8 | ||||

|

Jelalian 2016 (parallel RCT) |

I1: CBT‐healthy lifestyle | ‐ | 127 | 24 | ‐ | 17 | 11 | 46.0 | 48 weeks (after 24‐week intervention) |

| C1: CBT | ‐ | 9 | ‐ | 7 | 8 | 88.0 | |||

| total: | 33 | 24 | 19 | ‐ | |||||

|

Norman 2016 (parallel RCT) |

I1: stepped down | 53 | 460/106 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 35 | 66.0 | 12 months (immediately after intervention) |

| C1: enhanced usual care | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 38 | 71.6 | |||

| total: | 106 | 106 | 106 | 73 | 68.8 | ||||

|

Wong 2015 (parallel RCT) |

I1: standard weight loss diet + increase water intake | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 6 months (immediately after intervention) |

| C1: standard weight loss diet | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| total: | 38 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

|

Hofsteenge 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: group education | 54 | 219/189 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 36 | 50.7 | 18 months (after 36‐week intervention) |

| C1: dietitian only | 54 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 32 | 62.7 | |||

| total: | 122 | 122 | 122 | 68 | 55.7 | ||||

|

Schranz 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: resistance training | 17 | 61/56 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 21 | 70.0 | 12 months (6‐month postintervention) |

| C1: no intervention | 17 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 22 | 84.6 | |||

| total: | 56 | 56 | 56 | 43 | 76.8 | ||||

|

Visuthranukul 2015 (parallel RCT) |

I1: low GI diet | 26 | ‐ | 35 | ‐ | 25 | 25 | 71 | 6 months (immediately after intervention) |

| C1: conventional diet | 26 | 35 | ‐ | 27 | 27 | 77 | |||

| total: | 70 | ‐ | 52 | 52 | 74.3 | ||||

|

Pakpour 2015 (parallel RCT) |

I1: motivational interviewing | ‐ | 409/369 | 119 | ‐ | ‐ | 113 | 95.0 | 12 months (42 weeks after 6‐week intervention) |

| I2: motivational interviewing + parental involvement | 119 | ‐ | ‐ | 118 | 99.2 | ||||

| C1: passive control | 119 | ‐ | ‐ | 115 | 96.6 | ||||

| total: | 357 | 346 | 96.9 | ||||||

|

Bean 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: motivational interviewing values | 80 | 123/‐ | 58 | ‐ | ‐ | 52 | 89.7 | 6 months (3 months following end of intervention) |

| C1: education control | 80 | 41 | ‐ | ‐ | 35 | 85.4 | |||

| total: | 99 | 87 | 87.9 | ||||||

|

Carraway 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: mentor‐led exercise | 11 | ‐ | 11 | ‐ | ‐ | 10 | 91 | 7 months (12‐week intervention) |

| C1: wait list control | 13 | ‐ | 13 | ‐ | ‐ | 11 | 85 | ||

| total: | 24 | ‐ | ‐ | 22 | 91.6 | ||||

|

Sigal 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: diet + aerobic training | 62 | 840/358 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 57 | 76 | 6 months (after 22‐week intervention + 4‐week run‐in) |

| I2: diet + resistance training | 62 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 57 | 73 | |||

| I3: diet + aerobic + resistance training | 62 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 58 | 77 | |||

| C1: diet only | 62 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 57 | 75 | |||

| total: | 304 | 304 | 304 | 229 | 75.3 | ||||

|

Love‐Osborne 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: motivational interviewing | 80 | ‐ | 82 | 77 | 77 | 94 | 6‐8 months (immediately after intervention) | |

| C1: control | 80 | 83 | 72 | 72 | 87 | ||||

| total: | 165 | 149 | 149 | 90.3 | |||||

|

Kong 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: low GI diet | ‐ | ‐ | 52 | ‐ | 34 | 34 | 65.4 | 6 months (immediately following intervention) |

| C1: usual Chinese diet | 52 | ‐ | 27 | 27 | 51.9 | ||||

| total: | 104 | ‐ | 61 | 61 | 58.7 | ||||

|

Luna‐Pech 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: normocaloric diet + physical activity | ‐ | ‐ | 29 | ‐ | 26 | 26c | 89.7 | 28 weeks (immediately following intervention) |

| C1: no intervention | 29 | ‐ | 25 | 25d | 86.2 | ||||

| total: | 58 | ‐ | 51 | 51 | 87.9 | ||||

|

Boodai 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I1: multicomponent group sessions | 45 | 224/82 | 41 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 75.6 | 6 months (immediately following intervention) |

| C1: no intervention | 45 | 41 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 78.0 | |||

| total: | 82 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 76.8 | ||||

|

Gourlan 2013 (parallel RCT) |

I1: motivational interviewing + standard weight loss | 30 | ‐/64 | 28 | ‐ | 26 | 26 | 92.9 | 6 months (after 3‐month intervention for standard weight loss group, 6‐month intervention for motivational interviewing group) |

| C1: standard weight loss | 30 | 34 | ‐ | 28 | 28 | 82.4 | |||

| total: | 62 | ‐ | 62 | 54 | 87.1 | ||||

|

Patrick 2013 (parallel RCT) |

I1: website intervention | 26 | 387/101 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 17 | 65.4 | 12 months (immediately after intervention) |

| I2: website + group | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 14 | 53.8 | |||

| I3: website + SMS | 26 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 17 | 70.8 | |||

| C1: usual care | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 16 | 64.0 | |||

| total: | 101 | ‐ | 101 | 64 | 63.4 | ||||

|

Kong 2013 (cluster RCT) |

I1: ACTION | 21 | 101/60 | 31 | ‐ | 28 | 28 | 90.3 | 6 months (intervention for 1 academic year) |

| C1: standard care | 21 | 29 | ‐ | 23 | 23 | 79.3 | |||

| total: | 60 | ‐ | 51 | 51 | 85.0 | ||||

|

Pbert 2013 (cluster RCT) |

I1: "Lookin' Good Feelin' Good" | ‐ | 6/6 schools 176/82 participants |

42 | ‐ | 42 | 42 | 100 | 6 months (16‐week intervention) |

| C1: control | 40 | ‐ | 40 | 40 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 82 | ‐ | 82 | 82 | 100 | ||||

|

Brennan 2013 (cross‐over RCT) |

I1: motivational interviewing | ‐ | 120/‐ | 42 | ‐ | 17 | 17 | 40.5 | 12 months (26‐week intervention) |

| C1: wait list control | 21 | ‐ | 14 | 14 | 66.7 | ||||

| total: | 63 | ‐ | 31 | 31 | 49.2 | ||||

|

Walpole 2013 (parallel RCT) |

I1: motivational interviewing | 16 | 73/52 | 20 | ‐ | 20 | 20 | 100 | 6 months (immediately after intervention) |

| C1: social skills training | 16 | 20 | ‐ | 18 | 18 | 90 | |||

| total: | 40 | ‐ | 38 | 38 | 95 | ||||

|

Toulabi 2012 (parallel RCT) |

I1: behavioural modification | ‐ | 192/152 | 76 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 6 months (6‐week intervention) |

| C1: control | 76 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

| total: | 152 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

|

Debar 2012 (parallel RCT) |

I1: multicomponent intervention | 100 | 2647/2350 | 105 | ‐ | 90 | 90 | 85.7 | 12 months (5‐month intervention) |

| C1: usual care | 100 | 103 | ‐ | 83 | 83 | 80.6 | |||

| total: | 208 | ‐ | 173 | 173 | 83.2 | ||||

|

Ebbeling 2012 (parallel RCT) |

I1: multicomponent intervention | ‐ | 762/374 | 110 | ‐ | 105 | 105 | 95.5 | 24 months (52‐week intervention) |

| C1: control | 114 | ‐ | 104 | 104 | 91.2 | ||||

| total: | 224 | ‐ | 209 | 209 | 93.3 | ||||

|

Vos 2011 (parallel RCT) |

I1: family‐based CBT + nutrition | 35 | 108/81 | 41 | ‐ | 32 | 32 | 78.0 | 24 months (3‐month intervention) |

| C1: wait list control | 35 | 40 | ‐ | 35 | 35 | 87.5 | |||

| total: | 81 | ‐ | 66 | 81.5 | |||||

|

Christie 2011 (parallel RCT) |

I1: HELP weight management | 100 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 12 months (6‐month intervention) |

| C1: enhanced standard care | 100 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| total: | 174 | ‐ | ‐ | 145 | 83.3 | ||||

|

Wengle 2011 (parallel RCT) |

I1: mentored behaviour changing intervention | ‐ | ‐/38 | 20 | ‐ | 16 | 16 | 80.0 | 6 months (immediately after intervention) |

| C1: unmentored behaviour changing intervention | 18 | ‐ | 16 | 16 | 88.9 | ||||

| total: | 38 | ‐ | 32 | 32 | 84.2 | ||||

|

Ford 2010 (parallel RCT) |

I1: Mandometer | 40 | 115/‐ | 54 | 44 | 44 | 81.5 | 18 months (12‐month intervention) | |

| C1: standard care | 40 | 52 | 43 | 43 | 82.7 | ||||

| total: | 106 | 87 | 87 | 82.1 | |||||

|

Nguyen 2012 (parallel RCT) |

I1: Loozit + additional therapeutic contact | ‐ | 474/249 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 58 | 79.4 | 24 months (intervention continued for 24 months) |

| C1: Loozit | 78 | 78 | 78 | 56 | 71.8 | ||||

| total: | 151 | 151 | 151 | 114 | 78.5 | ||||

|

Grey 2009 (cluster RCT) |

I1: coping skills | ‐ | 426/324 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 87 | 77.7 | 36 weeks (16‐week intervention) |

| C1: general education | 86 | 86 | 86 | 64 | 74.4 | ||||

| total: | 198 | 198 | 198 | 151 | 76.3 | ||||

|

Vissers 2008 (parallel RCT) |

I1: school‐based intervention | ‐ | 506/‐ | 37 | ‐ | 22 | 22 | 59.5 | 6 months (immediately following intervention) |

| C1: control | 39 | ‐ | 31 | 31 | 79.5 | ||||

| total: | 76 | ‐ | 53 | 53 | 69.7 | ||||

|

NCT00132132 (parallel RCT) |

I1: behavioural education | ‐ | ‐ | 15 | ‐ | 8 | 8 | 53.3 | 12‐15 months (12‐month intervention) |

| C1: standard care | 15 | ‐ | 13 | 13 | 86.7 | ||||

| total: | 30 | ‐ | 21 | 21 | 70.0 | ||||

|

Pitetti 2007 (parallel RCT) |

I1: treadmill | ‐ | 42/‐ | 5 | ‐ | 5 | 5 | 100 | 36 weeks (immediately following intervention) |

| C1: control | 5 | ‐ | 5 | 5 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 10 | ‐ | 10 | 10 | 100 | ||||

|

Savoye 2007 (parallel RCT) |

I1: Bright Bodies weight management | 174 (58 per group (originally 3 groups) | 284/271 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 45 | 42.9 | 24 months (52‐week intervention) |

| C1: control | 69 | 69 | 69 | 31 | 44.9 | ||||

| total: | 174 | 174 | 174 | 76 | 43.7 | ||||

|

van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006 (parallel RCT) |

I1: multicomponent intervention | ‐ | 821 | 250 | 250 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 12 months (12‐month intervention)d |

| C1: standard care | 271 | 271 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

| total: | 521 | 521 | ‐ | 423 | 81.2 | ||||

|

Daley 2005 (parallel RCT) |

I1: exercise counselling | 30 | 141/132 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 24 | 85.7 | 28 weeks (8‐week intervention) |

| C1: exercise placebo | 30 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 95.7 | |||

| C2: control | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 25 | 83.3 | |||

| total: | 81 | 81 | 81 | 71 | 87.7 | ||||

|

Resnicow 2005 (cluster RCT) |

I1: GoGirls high‐intensity behavioural intervention | 75‐120 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 53 | 45 | ‐ | 12 months (6‐month intervention) |

| C1: moderate‐intensity behavioural intervention | 75‐120 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 70 | 62 | ‐ | ||

| total: | ‐ | ‐ | 123 | 107 | ‐ | ||||

|

Jiang 2005 (parallel RCT) |

I1: family‐based intervention | ‐ | 106/75 | 36 | ‐ | 33 | 33 | 91.7 | 24 months (immediately following intervention) |

| C1: control | 39 | ‐ | 35 | 35 | 89.7 | ||||

| total: | 75 | ‐ | 68 | 68 | 90.7 | ||||

|

Carrel 2005 (parallel RCT) |

I1: behaviour changing‐focused gym classes | ‐ | ‐/55 | 27 | ‐ | 27 | 27 | 100 | 9 months (immediately following intervention) |

| C1: standard gym classes | 26 | ‐ | 23 | 23 | 88.5 | ||||

| total: | 53 | ‐ | 50 | 50 | 94.3 | ||||

|

Ebbeling 2003 (parallel RCT) |

I1: low GL diet | ‐ | 30/21 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 87.5 | 12 months (26‐week intervention) |

| C1: conventional diet | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 87.5 | ||||

| total: | 16 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 87.5 | ||||

|

Saelens 2002 (parallel RCT) |

I1: Healthy Habits | 21 | ‐/59 | 23 | 23 | ‐ | 18 | 78.3 | 28 weeks (12‐week intervention) |

| C1: standard care | 21 | 21 | 21 | ‐ | 19 | 90.5 | |||

| total: | 44 | 44 | ‐ | 37 | 84.1 | ||||

|

Brownell 1983 (parallel RCT) |

I1: mother + child separate | ‐ | ‐ | 14 | ‐ | 12 | 12 | 85.7 | 12 months (16‐week intervention) |

| I2: mother + child together | 15 | ‐ | 12 | 12 | 80 | ||||

| C1: child only | 13 | ‐ | 12 | 12 | 92.3 | ||||

| total: | 42 | ‐ | 36 | 36 | 85.7 | ||||

|

Chandra 1968 (parallel RCT) |

I1: low‐calorie formula Limical | ‐ | 43 | ‐ | ‐ | 18 | 18 | ‐ | 7 months (3‐month intervention) |

| C1: low‐calorie diet | ‐ | ‐ | 17 | 17 | ‐ | ||||

| total: | 43 | ‐ | 35 | 35 | 81.4 | ||||

|

NCT00807560 (parallel RCT) |

I1: family‐based therapy for paediatric overweight | ‐ | ‐ | 39 | ‐ | 13 | 13 | 34.2 | 44 weeks (24‐week intervention) |

| C1: nutrition education control | ‐ | ‐ | 38 | ‐ | 9 | 11 | 38.2 | ||

| total: | 77 | 22 | 24 | 31.1 | |||||

| Grand totale | All interventions | ‐ | 2555 | ‐ | 1801 | ‐ | |||

| All comparators | 1850 | 1255 | |||||||

| All interventions and comparators | 4781 | 3735 | |||||||

‐ denotes not reported

aAccording to power calculation in study publication or report. bDuration of follow‐up/(duration of intervention). c For number of participants finishing the study the publication stated that 26 participants in the normocaloric diet + physical activity group and 25 participants in the no intervention groups finished the study but also reported that there were four dropouts/withdrawals in the normocaloric diet + physical activity group and eight dropouts/withdrawals in the no intervention group. dAt 6 months, only 115 (46%) children in the multicomponent intervention group and 135 (54%) children in the standard care group participated in a follow‐up examination. eNumbers did not add up accurately because of missing data per intervention/comparator groups in some trials.

C: comparator; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; FBT‐PO: family‐based therapy for paediatric overweight; GI: glycaemic index; GL: glycaemic load; I; intervention; ITT: intention to treat; n: number of participants; N/A: not applicable; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SMS: short message service.

We provided information including trial identifier about potentially relevant ongoing studies in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table and in Appendix 5 (Matrix of study endpoints (publications and trial documents)). We tried to find the protocol of each included study and reported primary, secondary and other outcomes in comparison with data in publications in Appendix 5.

We e‐mailed all authors of included studies to enquire whether they were willing to answer questions regarding their trials. Appendix 10 shows the results of this survey. Thereafter, we sought relevant missing information on the trial from the primary author(s) of the article, if required.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents or multiple reports of a primary study, we tried to maximise yield of information by collating all available data and use the most complete data set aggregated across all known publications. In case of doubt, we gave priority to the publication reporting the longest follow‐up associated with our primary or secondary outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane 'risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011a; Higgins 2011b), and evaluated the following criteria.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Imbalances in baseline characteristics.

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other potential sources of bias.

We judged the above 'Risk of bias' criteria as 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk' and evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We present a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias summary'. We assessed the impact of individual bias domains on study results at endpoint and study levels. In case of high risk of selection bias, all endpoints investigated in the associated study were marked as 'high risk'.

We evaluated whether imbalances in baseline characteristics existed and how these were addressed (Egbewale 2014).

For performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel) and detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors) we evaluated the risk of bias separately for each outcome type (objective and subjective) (Hróbjartsson 2013). We noted whether endpoints were self‐reported, investigator‐assessed or adjudicated outcome measures.

We considered the implications of missing outcome data from individual participants per outcome such as high dropout rates (e.g. above 15%) or disparate attrition rates (e.g. difference of 10% or more between study arms).

We assessed outcome reporting bias by integrating the results of 'Examination of outcome reporting bias' (Kirkham 2010) (Appendix 6), in the 'Matrix of study endpoints (publications and trial documents)' (Appendix 5), and 'Outcomes (outcomes reported in abstract of publication)' section of the Characteristics of included studies table. This analysis formed the basis for the judgement of selective reporting (reporting bias).

We defined the following endpoints as potentially self‐reported outcomes.

Adverse events.

Health‐related quality of life.

Participant's views of the intervention.

Changes in body weight.

Self‐esteem.

Behaviour change.

We defined the following outcomes as potentially investigator‐assessed outcomes.

Changes in BMI and body weight.

Adverse events.

All‐cause mortality.

Morbidity.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed dichotomous data as odds ratios (ORs) or risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We expressed continuous data as mean differences (MD) if they used the same instruments or standardised mean differences (SMD) if they used different instruments with 95% CI. We expressed time‐to‐event data as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs.

We included studies reporting multiple comparison groups in this review. Where this was the case, we considered whether the aim of the trial was to test for differences between these groups, and whether the study authors found a significant difference. Where there were no demonstrated differences, we merged groups as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 7.7.8, Higgins 2011a). In studies that found a difference between groups, we used the data for the control group for each intervention group comparison and reduced the weight assigned to the control group by dividing the number of participants in the control group by the number of intervention groups.

Unit of analysis issues

We used data from the first period of cross‐over trials if available. We collected data from the latest available time point in the follow‐up reported in the studies to avoid double‐counting trials in the same analysis. For cluster RCTs, we used the denominator reported in the trial and considered how the analysis methods used took account of the effect of clustering. Due to the small number of cluster RCTs found, we decided not to adjust the data so we performed sensitivity analyses to ascertain if the results were sensitive to the inclusion of studies with a cluster design.

Dealing with missing data

We obtained relevant missing data from study authors, if feasible, and evaluated important numerical data such as screened, eligible, randomised participants as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated and per‐protocol populations. We investigated attrition rates (e.g. dropouts, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals), and critically appraised issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward (LOCF)).

Where standard deviations (SD) for outcomes were not reported, and we did not receive information from study authors, we imputed these values by assuming the SD of the missing outcome to be the same as the largest SD from those studies where this information was reported. We investigated the impact of imputation on meta‐analyses by means of sensitivity analyses. Where papers did not report results as change from baseline, we calculated this and for the SD differences followed the methods presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention for imputing these (Section 16.1.3.2, Higgins 2011a), and assumed a correlation of 0.5 between baseline and follow‐up measures as suggested by Follmann 1992.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we did not report study results as meta‐analytically pooled effect estimates. We identified heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots and by using a standard Chi2 test with a significance level of α = 0.1, in view of the low power of this test. We examined heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003), where an I2 statistic of 75% or more indicates a considerable level of inconsistency (Higgins 2011a).

When we found heterogeneity, we attempted to determine potential reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

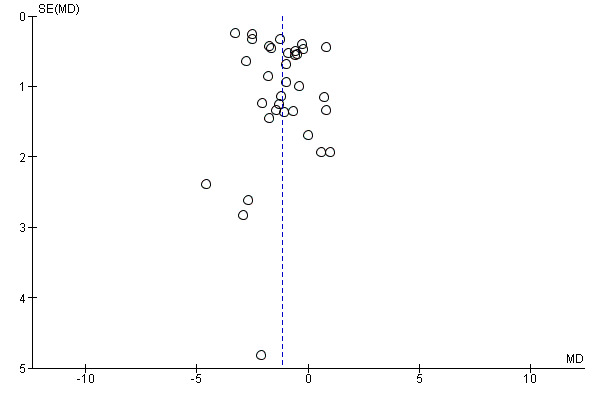

Assessment of reporting biases

If we included 10 studies or more for a given outcome, we used funnel plots to assess small‐study effects. Due to several explanations for funnel plot asymmetry, we interpreted results carefully (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Unless there is good evidence for homogeneous effects across studies we primarily summarised low risk of bias data using a random‐effects model (Wood 2008). We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration of the whole distribution of effects, ideally by presenting a prediction interval (Higgins 2009). A prediction interval specifies a predicted range for the true treatment effect in an individual study (Riley 2011). In addition, we performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Quality of evidence

We presented the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE approach which takes into account issues related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias)and also to external validity, such as directness of results. Two review authors (LA‐K and KR/EL) rated the quality for each outcome. We presented a summary of the evidence in a Table 1, which provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect, in relative terms and absolute differences for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies, numbers of participants and studies addressing each important outcome and the rating of the overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the 'Summary of findings' table based on the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We presented results on the outcomes as described in Types of outcome measures. If meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table.

In addition, we established an appendix 'Checklist to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments' (Meader 2014) to help with standardisation of 'Summary of findings' tables (Appendix 9).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity, and planned to carry out subgroup analyses with investigation of interactions for our primary outcomes.

Duration of follow‐up.

Duration of the intervention.

Duration of postintervention follow‐up.

Type of comparator group.

Mode of delivery of the intervention.

Setting.

Type of intervention.

Theoretical basis to the intervention.

Parental involvement.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Restricting the analysis to published studies, and by publication language.

Restricting the analysis taking into account risk of bias, as specified in the section Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section.

Restricting the analysis to studies of adolescents without specific health conditions.

Restricting the analysis to studies with no uncertainties (such as study duration, imputed data).

We also tested the robustness of the results by repeating the analysis using different measures of effect size (RRs, ORs, etc.) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of trials, see the Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

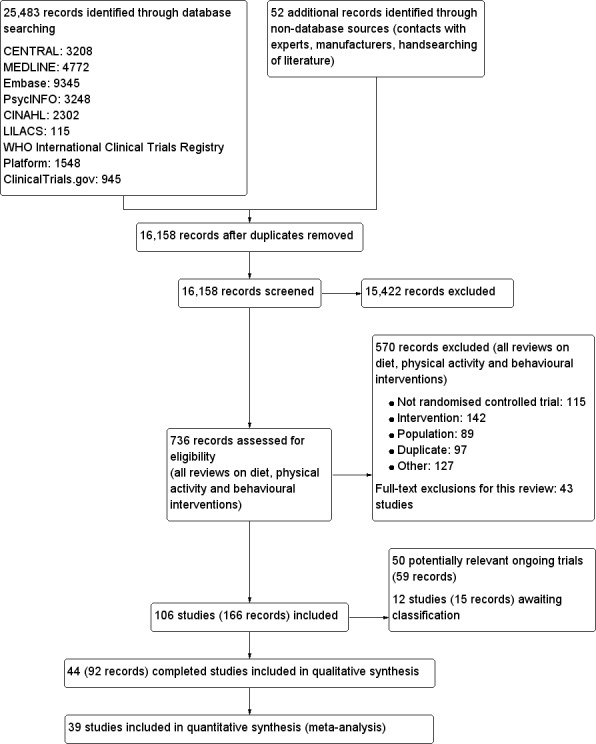

This search is up to date as of July 2016 in addition to ongoing e‐mail alerts from MEDLINE. The searches generated 16,106 hits after duplicates were removed. Fifty‐two additional records were identified through non‐database sources. Screening of titles and abstracts identified 736 records to go forward for formal inclusion and exclusion. Forty‐four completed RCTs fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. For a detailed description of the included trials, see the Characteristics of included studies table. The search identified 50 ongoing trials, which are reported in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table. The flow of trials through the review is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

A detailed description of the characteristics of included studies is presented elsewhere (see Characteristics of included studies and Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 11). The following is a succinct overview.

Source of data

All data presented in the review were obtained from the published literature. We contacted all study authors for additional information and results are presented in Appendix 10.

Comparisons

To meet the inclusion criteria for the review comparators could be no treatment, usual care or a concomitant therapy providing it was also included in the intervention group. In nine trials the comparator was either no intervention or a wait list control (Brennan 2013; Carraway 2014; Ebbeling 2012; Luna‐Pech 2014; Pakpour 2015; Patsopoulou 2017; Schranz 2014; Toulabi 2012; Vos 2011). Twenty‐three studies used usual care comparators (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Carrel 2005; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2003; Ford 2010; Gourlan 2013; Hofsteenge 2014; Jiang 2005; Kong 2013; Love‐Osborne 2014; NCT00132132; NCT00807560; Patrick 2013; Pbert 2013; Pitetti 2007; Saelens 2002; Savoye 2007; Vissers 2008; Visuthranukul 2015; van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006). Twelve trials used a concomitant therapy (Brownell 1983; Chandra 1968; Grey 2009; Jelalian 2016; Kong 2014; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Resnicow 2005; Sigal 2014; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011; Wong 2015).

Overview of trial populations

The 44 trials included 4781 participants. Approximately 2555 were randomised to an intervention and 1850 to a comparator. The proportion of participants finishing the study, where reported, ranged from 34% to 100% in the intervention groups and from 38% to 100% in the comparator groups. Individual sample size ranged from 10 to 521.

Study design

Thirty‐nine trials were parallel comparisons with individual randomisation. Four trials were cluster RCTs (Grey 2009; Kong 2013; Pbert 2013; Resnicow 2005), and one was a cross‐over trial (Brennan 2013). All 44 trials had a superiority design. Five trials had three arms (Brownell 1983; Daley 2005; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Patsopoulou 2017), and two trials had four arms (Patrick 2013; Sigal 2014). The majority (24) were single centre trials, although the number of centres was unclear or not reported in 10 trials. Two trials had six centres (Grey 2009; Kong 2013), and one study each had two (Brennan 2013), eight (Pbert 2013), 10 (Resnicow 2005), 12 (Toulabi 2012), 15 (Patsopoulou 2017) or 18 (Patrick 2013) centres. Trials were performed from 1968 to 2015. The duration of the intervention ranged from six weeks to two years, and the duration of follow‐up ranged from six months to two years. Eight trials had some form of run‐in period prior to the start of the study (Brownell 1983; Chandra 1968; Luna‐Pech 2014; Norman 2016; Pitetti 2007; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; Wengle 2011). None of the trials was terminated early.

Settings

The interventions were carried out in a variety of settings. These included in schools in nine trials (Carrel 2005; Grey 2009; Jiang 2005; Kong 2013; Love‐Osborne 2014; Pbert 2013; Pitetti 2007; Toulabi 2012; Vissers 2008), in the community or home in eight trials (Ebbeling 2012; Nguyen 2012; Patrick 2013; Patsopoulou 2017; Resnicow 2005; Saelens 2002; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014), and various healthcare settings, including outpatients, primary care, research clinics and other hospital sites in 26 trials (based on author locations where the study did not explicitly report this) (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Brownell 1983; Carraway 2014; Chandra 1968; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2003; Ford 2010; Gourlan 2013; Hofsteenge 2014; Jelalian 2016; Kong 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00132132; NCT00807560; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Savoye 2007; Visuthranukul 2015; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011; Wong 2015).

Participants

The diagnostic criteria for overweight and obesity differed between the trials. Twelve trials included participants with BMI on or above the 85th percentile for age and height (Bean 2014; Carraway 2014; Ebbeling 2012; Grey 2009; Jelalian 2016; Kong 2013; Love‐Osborne 2014; NCT00132132; NCT00807560; Pbert 2013; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011), nine trials used a cut‐off of on or above the 95th percentile (Boodai 2014; Carrel 2005; Ebbeling 2003; Ford 2010; Kong 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Savoye 2007), three trials used a cut‐off of on or above the 90th percentile (Debar 2012; Gourlan 2013; Resnicow 2005), and two trials used a cut‐off of on or above the 98th percentile (Christie 2011; Daley 2005). The remaining trials used a range of different criteria to define overweight or obesity for inclusion in the trials (Characteristics of included studies table; Appendix 3).

Thirty‐four trials reported the mean BMI at baseline (Brennan 2013; Brownell 1983; Carrel 2005; Christie 2011; Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2003; Ebbeling 2012; Ford 2010; Gourlan 2013; Grey 2009; Hofsteenge 2014; Jelalian 2016; Jiang 2005; Kong 2014; Love‐Osborne 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00807560; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Patsopoulou 2017; Pbert 2013; Pitetti 2007; Resnicow 2005; Saelens 2002; Savoye 2007; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; Toulabi 2012; Vissers 2008; Visuthranukul 2015; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011) and ranged from 26 kg/m2 to 37 kg/m2 in all but one study (Brownell 1983), which was an outlier with BMIs in the three study groups ranging from 42 kg/m2 to 45.5 kg/m2. Sixteen trials reported BMI z scores (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Carraway 2014; Daley 2005; Love‐Osborne 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00807560; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; Pbert 2013; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011), and these ranged across all trials between 1.8 and 3.2 with the exception of one study (Vos 2011), which had a mean BMI Standard Deviation Score (SDS) of 4.2. One study reported BMI percentile only at baseline (at 94.5%) (Kong 2013), and two trials did not report BMI measures at baseline (Chandra 1968; Gourlan 2013). Twenty trials reported on change in weight.

Thirty‐seven trials reported the gender of the study participants (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Brownell 1983; Carrel 2005; Chandra 1968; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2003; Ebbeling 2012; Ford 2010; Gourlan 2013; Grey 2009; Hofsteenge 2014; Jelalian 2016; Jiang 2005; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; Love‐Osborne 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00132132; NCT00807560; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; Pbert 2013; Pitetti 2007; Resnicow 2005; Savoye 2007; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; Vissers 2008; Visuthranukul 2015; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013, and the proportion of participants who were female ranged from 33% to 77% in all cases except the trials by Debar 2012 and Resnicow 2005 where all participants were female, and Schranz 2014 where all participants were male. Four trials did not report the gender of participants at baseline (Saelens 2002; Toulabi 2012; Wengle 2011; Wong 2015). Participants ages ranged from 12 to 17.5 years in all trials that reported mean age at baseline, 11 trials did not report mean age at baseline (Brennan 2013; Brownell 1983; Chandra 1968; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Gourlan 2013; NCT00132132; Resnicow 2005; Saelens 2002; Toulabi 2012; Wong 2015).

Nineteen trials reported ethnicity (Bean 2014; Brownell 1983; Carraway 2014; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2012; Ford 2010; Grey 2009; Hofsteenge 2014; Jelalian 2016; Kong 2013; Love‐Osborne 2014; Norman 2016; Patrick 2013; Pbert 2013; Resnicow 2005; Savoye 2007; Sigal 2014; Vos 2011). Most trials reported a mixture of ethnic backgrounds for their participants as can be seen in Appendix 3, two trials reported exclusively on African‐Americans (Resnicow 2005) and participants described as 'white' (Brownell 1983).

Three trials focused on participants with specific conditions, Jelalian 2016 included people with depression, Luna‐Pech 2014 included people with asthma and Pitetti 2007 included people with autism living in a residential school.

Interventions

Thirty‐four trials included interventions that were multidisciplinary (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Brownell 1983; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Gourlan 2013; Grey 2009; Hofsteenge 2014; Jelalian 2016; Jiang 2005; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; Love‐Osborne 2014; NCT00132132; NCT00807560; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; Patsopoulou 2017; Pbert 2013; Resnicow 2005; Saelens 2002; Savoye 2007; Sigal 2014; Toulabi 2012; van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006; Vissers 2008; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011; Wong 2015), where the focus was on at least two components of diet, physical activity and behavioural approaches to weight management. Five trials were focused solely on dietary interventions (Ebbeling 2003; Ebbeling 2012; Ford 2010; Luna‐Pech 2014; Visuthranukul 2015), and five focused solely on physical activity interventions (Carraway 2014; Carrel 2005; Chandra 1968; Pitetti 2007; Schranz 2014). Twenty‐nine trials had a theoretical basis to their interventions, these included six which had a cognitive behavioural or social cognitive theoretical basis (Hofsteenge 2014; Jelalian 2016; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pbert 2013; Vos 2011), eight which used motivational interviewing approaches (Bean 2014; Brennan 2013; Christie 2011; Gourlan 2013; Love‐Osborne 2014; Pakpour 2015; Resnicow 2005; Walpole 2013), and 15 that used a variety of other psychological approaches (Boodai 2014; Brownell 1983; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Grey 2009; Jiang 2005; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; NCT00132132; Patrick 2013; Saelens 2002; Savoye 2007; Toulabi 2012; Vissers 2008; Wengle 2011). Thirteen trials did not use a behavioural approach or did not report the theoretical basis to any behavioural component of their intervention (Carrel 2005; Chandra 1968; Ebbeling 2003; Ebbeling 2012; Ford 2010; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00807560; Patsopoulou 2017; Pitetti 2007; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; Visuthranukul 2015; Wong 2015). Twenty‐six trials involved parents in the intervention (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Brownell 1983; Carraway 2014; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2012; Grey 2009; Hofsteenge 2014; Jelalian 2016; Jiang 2005; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; NCT00807560; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; Resnicow 2005; Savoye 2007; Toulabi 2012; Visuthranukul 2015; Vos 2011; Wengle 2011). In 15 trials, there was no parental involvement (Carrel 2005; Chandra 1968; Ebbeling 2003; Ford 2010; Gourlan 2013; Love‐Osborne 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00132132; Pbert 2013; Pitetti 2007; Saelens 2002; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; Vissers 2008; Walpole 2013), and in three trials there were two intervention groups, one which included the parent and one which did not (Brownell 1983; Pakpour 2015; Patsopoulou 2017).

Nineteen trials delivered the intervention in a group format (Boodai 2014; Brownell 1983; Carrel 2005; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Grey 2009; Hofsteenge 2014; NCT00132132; Nguyen 2012; Pakpour 2015; Patsopoulou 2017; Pitetti 2007; Resnicow 2005; Savoye 2007; Schranz 2014; Toulabi 2012; Visuthranukul 2015; Vos 2011), for specific details see Characteristics of included studies table. In 14 studies, the intervention was individually based (Bean 2014; Brennan 2013; Ebbeling 2012; Ford 2010; Gourlan 2013; Jiang 2005; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; Norman 2016; Pbert 2013; Saelens 2002; Sigal 2014; Walpole 2013), and in 10 studies, there was a mixture of some group and some individual sessions, or the trial did not report the mode of delivery (Carraway 2014; Chandra 1968; Ebbeling 2003; Jelalian 2016; Love‐Osborne 2014; NCT00807560; Patrick 2013; Vissers 2008; Wengle 2011; Wong 2015).

The duration of the intervention was six months or less in 30 trials (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Brownell 1983; Carraway 2014; Chandra 1968; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2003; Gourlan 2013; Grey 2009; Jelalian 2016; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; NCT00807560; Pakpour 2015; Patsopoulou 2017; Pbert 2013; Resnicow 2005; Saelens 2002; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; Toulabi 2012; Vissers 2008; Visuthranukul 2015; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011; Wong 2015), and greater than six months in 14 trials (Carrel 2005; Ebbeling 2012; Ford 2010; Hofsteenge 2014; Jiang 2005; Love‐Osborne 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00132132; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Patrick 2013; Pitetti 2007; Savoye 2007; van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006).

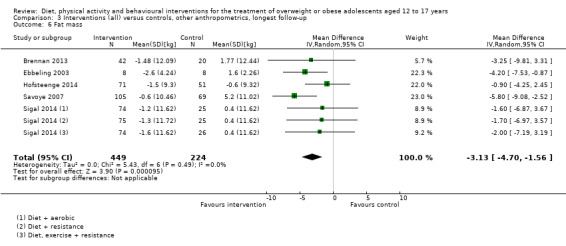

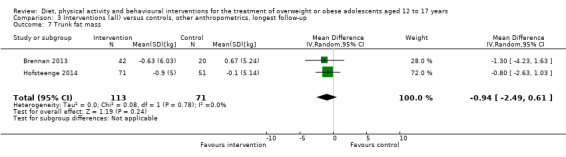

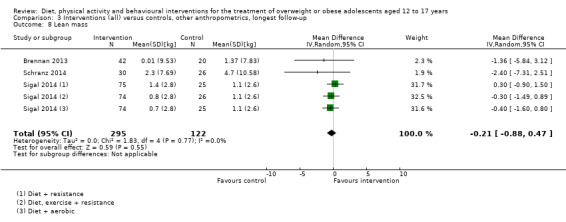

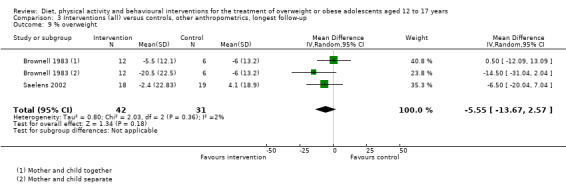

Outcomes

Twenty‐three trials explicitly stated a primary endpoint in the publication (Appendix 5); in 20 of these, this was a measure of body composition such as weight or BMI. In the trial by Schranz 2014, the primary outcomes were exercise self‐efficacy, physical self‐worth and self‐esteem. In the trial by Walpole 2013, the primary outcome was self‐efficacy and in Daley 2005 the primary outcome was physical self‐perceptions. All except one of the included trials (Chandra 1968) reported a BMI variable as an outcome; this was BMI in 29 trials, BMI z score in 20 trials, BMI percentile in five trials (15 trials reported more than one BMI variable, Brennan 2013; Debar 2012; Hofsteenge 2014; Jiang 2005; NCT00807560; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; Pbert 2013; Saelens 2002; Savoye 2007; Visuthranukul 2015; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011). Twenty trials reported weight and five trials reported rates of adverse events as described in the Effects of interventions section. Twenty‐nine trials reported other anthropometric measures (Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Brownell 1983; Carraway 2014; Carrel 2005; Chandra 1968; Ebbeling 2003; Ebbeling 2012; Ford 2010; Grey 2009; Hofsteenge 2014; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; NCT00132132; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; Patsopoulou 2017; Pbert 2013; Saelens 2002; Savoye 2007; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; Toulabi 2012; Vissers 2008; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013; Wengle 2011); this was percent body fat in 14 trials, trunk fat percentage in two trials, waist circumference in 16 trials, waist‐to‐height ratio in three trials, waist‐to‐hip ratio in two trials, fat mass in five trials, trunk fat mass in two trials, lean mass in three trials and percentage of overweight in two trials. Nine trials reported health‐related quality of life (Debar 2012; Ford 2010; Hofsteenge 2014; Nguyen 2012; Luna‐Pech 2014; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006; Vos 2011). Nine trials reported self‐esteem (Brennan 2013; Carraway 2014; Daley 2005; Debar 2012; Hofsteenge 2014; Nguyen 2012; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; Schranz 2014). Eleven trials reported behavioural change in terms of dietary intake (Brennan 2013; Ebbeling 2003; Ebbeling 2012; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; Pakpour 2015; Patrick 2013; Pbert 2013; Saelens 2002; Visuthranukul 2015; Wengle 2011), while four trials reported dietary behaviour (Brennan 2013; Ford 2010; Grey 2009; Pakpour 2015). Twelve trials reported behavioural change in terms of physical activity (Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2012; Gourlan 2013; Grey 2009; Jelalian 2016; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; Pakpour 2015; Pbert 2013; Saelens 2002; Sigal 2014; Wengle 2011), while three trials reported physical activity behaviour (Grey 2009; Kong 2013; Pakpour 2015). One trials reported parenting and relationships (Brennan 2013). Eight trials reported views of the intervention (Brennan 2013; Christie 2011; Debar 2012; Jelalian 2016; Nguyen 2012; Pbert 2013; Saelens 2002; Wengle 2011).

Ten trials reported outcomes at more than one time point (Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2012; Hofsteenge 2014; Jiang 2005; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Patrick 2013; Resnicow 2005; Savoye 2007; Schranz 2014).

Excluded studies

We excluded 570 of 736 articles after evaluation of the publication. The main reasons for exclusion were the intervention (aim not focused on treating overweight/obesity and duration of intervention and follow‐up less than six months) and study design (not an RCT). Many trials had other reasons for exclusion such as lack of relevant outcomes or the control was not no intervention/usual care or concomitant intervention as long as this was also provided in the intervention arm (for further details see Characteristics of excluded studies table, which lists the 44 studies that closely missed the inclusion criteria for this review).

Studies awaiting classification

Twelve studies are awaiting classification as we await clarification from the study authors. These may be included when this review is updated if they meet the inclusion criteria.

Ongoing studies

Fifty studies are ongoing or have completed but results are not available. These may be included when this review is updated if they meet the inclusion criteria.

Risk of bias in included studies

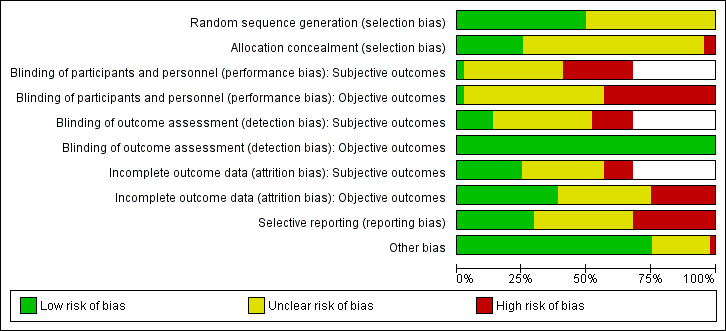

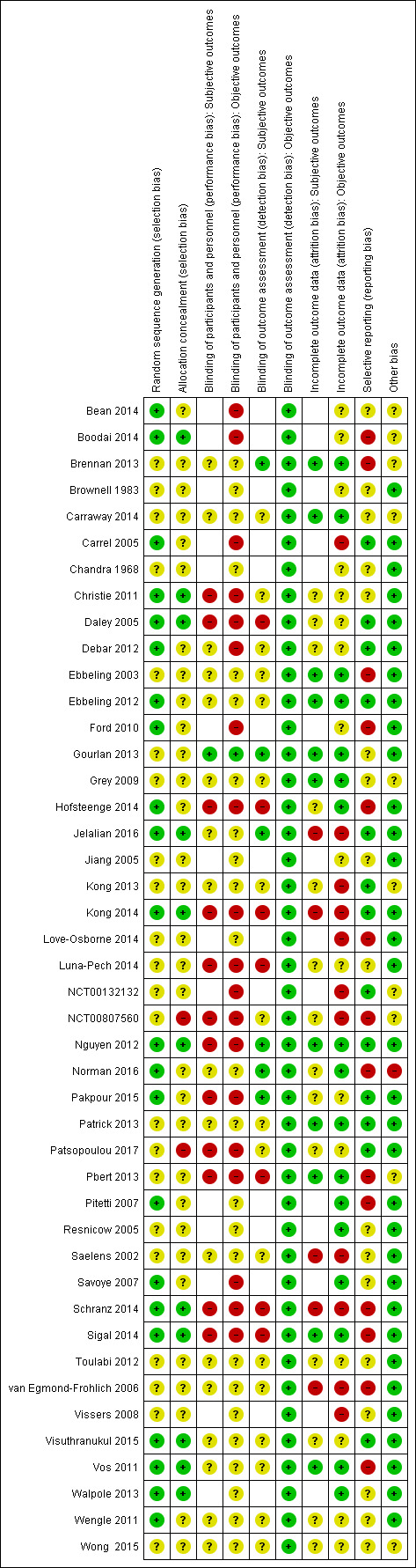

For details on risk of bias of included studies, see the Characteristics of included studies table. For an overview of review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for individual studies and across all studies, see Figure 2 and Figure 3. Many trials did not report adequate information to assess the risk of bias and we assessed 30 trials at high risk of bias on at least one domain. We assessed 10 trials at high risk of bias on three or more domains (Daley 2005; Hofsteenge 2014; Kong 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00807560; Patsopoulou 2017; Pbert 2013; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies (blank cells indicate that the particular outcome was not investigated in some studies).

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study (blank cells indicate that the study did not report that particular outcome).

Allocation

The majority of trials provided sufficient information on random sequence generation and were judged at low risk of bias. However, most trials provided inadequate information on concealment of allocation. Twenty‐two studies reported adequate random sequence generation, but only 11 of these also described adequate concealment of allocation (Boodai 2014; Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Jelalian 2016; Kong 2014; Nguyen 2012; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; Visuthranukul 2015; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013), and therefore have a low risk of selection bias. One trial described allocation concealment and was at high risk of bias (Patsopoulou 2017). One trial was also high risk of bias for allocation concealment (NCT00807560). The risk of selection bias was uncertain in the remaining 31 included studies.

Blinding

Only one study had a low risk of performance bias (subjective and objective outcomes) as participants and personnel were blinded to treatment allocation (Gourlan 2013). Nineteen studies had a high risk of performance bias for subjective and objective outcomes (Christie 2011; Daley 2005; Hofsteenge 2014; Kong 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; NCT00807560; Nguyen 2012; Pakpour 2015; Patsopoulou 2017; Pbert 2013; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014) or objective outcomes only (subjective outcomes not reported) (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Carrel 2005; Debar 2012; Ford 2010; NCT00132132; Savoye 2007). The risk of performance bias was unclear in the remaining 24 studies.

The risk of detection bias was low for objective outcomes (regardless of whether outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation) in 44 studies. For subjective outcomes, six studies blinded outcome assessors (Brennan 2013; Gourlan 2013; Jelalian 2016; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Pakpour 2015), and this was unclear in 17 studies (Carraway 2014; Christie 2011; Debar 2012; Ebbeling 2003; Ebbeling 2012; Grey 2009; Kong 2013; NCT00807560; Patrick 2013; Patsopoulou 2017; Saelens 2002; Toulabi 2012; van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006; Visuthranukul 2015; Vos 2011; Wengle 2011; Wong 2015). The risk of detection bias was judged to be high in the remaining seven studies reporting subjective ouLena1234tcomes (Daley 2005; Hofsteenge 2014; Kong 2014; Luna‐Pech 2014; Pbert 2013; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014).

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias was low in 17 studies (Brennan 2013; Carraway 2014; Ebbeling 2003; Ebbeling 2012; Gourlan 2013; Grey 2009; Hofsteenge 2014; Nguyen 2012; Norman 2016; Patrick 2013; Pbert 2013; Pitetti 2007; Resnicow 2005; Savoye 2007; Sigal 2014; Vos 2011; Walpole 2013). Eleven studies had a high risk of attrition bias on objective and subjective (where reported) outcome measures due to an imbalance in attrition between study groups (Carrel 2005; Jelalian 2016; Kong 2013; Kong 2014; Love‐Osborne 2014; NCT00132132; NCT00807560; Saelens 2002; Schranz 2014; van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006; Vissers 2008). The remaining 16 studies were at unclear risk of bias due to insufficient reporting of attrition, such as not providing reasons for missing data.

Selective reporting

Fourteen studies were at high risk of reporting bias (Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Ebbeling 2003; Ford 2010; Hofsteenge 2014; Love‐Osborne 2014; NCT00807560; Norman 2016; Pbert 2013; Pitetti 2007; Schranz 2014; Sigal 2014; van Egmond‐Frohlich 2006; Vos 2011). In 17 studies, this was unclear, as the study protocol or trial record were unavailable, or the trial had yet to be fully published. The remaining 13 studies reported all outcomes as stated.

Other potential sources of bias

There was high risk of bias in one study as the run‐in programme was conducted to minimise participant attrition, but may have resulted in a more motivated sample of participants and parents compared with non‐run‐in trial cohorts (Norman 2016). There was an unclear risk of other sources of bias in 10 studies (Bean 2014; Boodai 2014; Brennan 2013; Carraway 2014; Grey 2009; Kong 2013; NCT00132132; NCT00807560; Pbert 2013; Wong 2015). In one of these studies, the participating churches (which were the unit of randomisation) requested that the comparison condition received a meaningful intervention, which may have had an impact on results (Resnicow 2005). The remaining 32 studies were at low risk of other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

None of the included studies reported all‐cause mortality, morbidity and socioeconomic effects.

All diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions versus controls

Primary outcomes