Abstract

Background

Neonatal endotracheal intubation is a common and potentially life‐saving intervention. It is a mandatory skill for neonatal trainees, but one that is difficult to master and maintain. Intubation opportunities for trainees are decreasing and success rates are subsequently falling. Use of a stylet may aid intubation and improve success. However, the potential for associated harm must be considered.

Objectives

To compare the benefits and harms of neonatal orotracheal intubation with a stylet versus neonatal orotracheal intubation without a stylet.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE; Embase; the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and previous reviews. We also searched cross‐references, contacted expert informants, handsearched journals, and looked at conference proceedings. We searched clinical trials registries for current and recently completed trials. We conducted our most recent search in April 2017.

Selection criteria

All randomised, quasi–randomised, and cluster‐randomised controlled trials comparing use versus non‐use of a stylet in neonatal orotracheal intubation.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed results of searches against predetermined criteria for inclusion, assessed risk of bias, and extracted data. We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Collaboration, as documented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic Reviews of Interventions, and of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group.

Main results

We included a single‐centre non‐blinded randomised controlled trial that reported a total of 302 intubation attempts in 232 infants. The median gestational age of enrolled infants was 29 weeks. Paediatric residents and fellows performed the intubations. We judged the study to be at low risk of bias overall. Investigators compared success rates of first‐attempt intubation with and without use of a stylet and reported success rates as similar between stylet and no‐stylet groups (57% and 53%) (P = 0.47). Success rates did not differ between groups in subgroup analyses by provider level of training and infant weight. Results showed no differences in secondary review outcomes, including duration of intubation, number of attempts, participant instability during the procedure, and local airway trauma. Only 25% of all intubations took less than 30 seconds to perform. Study authors did not report neonatal morbidity nor mortality. We considered the quality of evidence as low on GRADE analysis, given that we identified only one unblinded study.

Authors' conclusions

Current available evidence suggests that use of a stylet during neonatal orotracheal intubation does not significantly improve the success rate among paediatric trainees. However, only one brand of stylet and one brand of endotracheal tube have been tested, and researchers performed all intubations on infants in a hospital setting. Therefore, our results cannot be generalised beyond these limitations.

Plain language summary

Rates of successful intubation performed with a stylet in infants compared with rates of successful intubation performed without a stylet

Review question: Does use of a stylet increase success rates of newborn intubation without increasing risk of harm?

Background: Intubation consists of placement of a breathing tube (endotracheal tube) into the baby’s windpipe or trachea to maintain an open airway. This common procedure may be needed both at birth and in the neonatal intensive care unit if the baby is not able to breathe well for himself. Trainee doctors must learn this difficult skill and sometimes must make more than one attempt to get the tube in the right place. The breathing tube is a narrow, plastic, flexible tube. A stylet, which is a malleable metal wire coated with plastic, can be inserted into the breathing tube to make it more rigid; this might make it easier to get the tube in the right place on the first attempt. However, use of a stylet may increase the risk of harm to the patient during the procedure.

Study characteristics: In literature searches updated in April 2017, we found one randomised controlled trial (302 intubations) that met the inclusion criteria of this review.

Results: Rates of successful intubation at first attempt with or without use of a stylet as an aid were similar, at 57% and 53%, respectively. Success rates with and without use of a stylet did not differ between infants of different weights, or between trainee paediatric doctors with different levels of experience. The length of time it took to intubate and the number of attempts made before successful intubation were comparable between groups. The incidence of a drop in a patient’s oxygen level and in heart rate was equivalent between groups, as was the reported incidence of trauma to the airway associated with the procedure.

Quality of the evidence: The quality of evidence was low. We downgraded the level because we included only one unblinded study.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Stylet compared with no stylet for neonatal intubation | ||||||

|

Patient or population: neonates requiring endotracheal intubation Settings: neonatal intensive care unit or delivery room or theatre Intervention: a stylet inserted into the endotracheal tube Comparison: no stylet inserted into the endotracheal tube | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of intubations (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Stylet | |||||

|

First intubation attempt success rate (outcome achieved at time of intubation attempt and not followed up) |

529 per 1000 | 570 per 1000 (466 to 698) | RR 1.08 (0.88 to 1.32) | 302 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a,b low | Unblinded trial with no blinded outcome assessment Single study |

| Gestational age of the infant | no data | no data | no data | no data | absence of evidence | |

|

Professional category of the intubator ‐ fellow: first intubation attempt success rate (outcome achieved at time of intubation attempt and not followed up) |

707 per 1000 | 667 per 1000 (488 to 548) | RR 0.94 (0.69 to 1.29) | 74 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝a,b low | Unblinded trial with no blinded outcome assessment Single study |

|

Professional category of the intubator ‐ resident: first intubation attempt success rate (outcome achieved at time of intubation attempt and not followed up) |

464 per 1000 | 543 per 1000 (418 to 705) | RR 1.17 (0.90 to 1.52) | 228 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a,b low | Unblinded trial with no blinded outcome assessment Single study |

| Level of experience of the intubator | no data | no data | no data | no data | absence of evidence | |

|

Premedication given ‐ no premedication given: first intubation attempt success rate (outcome achieved at time of intubation attempt and not followed up) |

540 per 1000 | 528 per 1000 (389 to 713) | RR 0.98 (0.72 to 1.32) | 146 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a,b low | Unblinded trial with no blinded outcome assessment Single study |

|

Premedication given ‐ no premedication given: first intubation attempt success rate (outcome achieved at time of intubation attempt and not followed up) |

519 per 1000 | 610 per 1000 (462 to 804) | RR 1.18 (0.89 to 1.55) | 156 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a,b low | Unblinded trial with no blinded outcome assessment Single study |

|

Timing of intubation ‐ just after birth in the delivery room: first intubation attempt success rate (outcome achieved at time of intubation attempt and not followed up) |

540 per 1000 | 528 per 1000 (389 to 713) | RR 0.98 (0.72 to 1.32) | 146 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a,b low | Unblinded trial with no blinded outcome assessment Single study |

|

Timing of intubation ‐ following admission to NICU: first intubation attempt success rate (outcome achieved at time of intubation attempt and not followed up) |

519 per 1000 | 610 per 1000 (462 to 804) | RR 1.18 (0.89 to 1.55) | 156 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a,b low | Unblinded trial with no blinded outcome assessment Single study |

| Type of stylet | no data | no data | no data | no data | absence of evidence | |

|

Weight < 1000 g (outcome achieved at time of intubation attempt and not followed up) |

597 per 1000 | 533 per 1000 (400 to 704) | RR 0.89 (0.67 to 1.18) | 152 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a,b low | Unblinded trial with no blinded outcome assessment Single study |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on assumed risk in the comparison group and relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aHigh risk of detection bias (due to lack of blinding of caregivers and outcome assessors)

bSerious imprecision (due to small number of events and small sample sizes; 95% CIs include null effects)

Background

Description of the condition

Neonatal endotracheal intubation refers to placement of an endotracheal tube (ETT; breathing tube) within an infant's airway. This intervention is commonly needed and may be life‐saving for infants after birth and during neonatal intensive care. Indications for intubation during neonatal resuscitation include ineffective or prolonged positive‐pressure ventilation delivered via face mask; need to secure the airway when cardiac compressions are performed; intratracheal administration of medications; and special resuscitation circumstances such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia or endotracheal suctioning for meconium (ILCOR 2005; Perlman 2010). Endotracheal intubation is necessary when neonatal intensive care is provided for infants in respiratory failure, despite non‐invasive respiratory support, as well as for administration of surfactant, for treatment of resistant apnoea of prematurity, and for preparation of infants undergoing surgery. Intubation can be performed by the nasotracheal (through the nose) or orotracheal (through the mouth) route. This review will focus solely on orotracheal intubation; whenever intubation is mentioned, we will be referring to orotracheal intubation. We will not consider nasal intubation here, as it is not possible to use a stylet safely during nasal intubation.

Endotracheal intubation is a mandatory competency for neonatal trainees. However, it is a difficult skill to learn and maintain, and initial attempts are often unsuccessful. Successful intubation relies on the ability of the intubator to perform laryngoscopy (using a laryngoscope inserted into the patient's mouth to obtain a view of the infant’s airway) and to recognise the anatomy displayed. Opportunities for neonatal trainees to acquire and maintain proficiency in endotracheal intubation are decreasing (Leone 2005), likely owing to increased use of non‐invasive respiratory support in neonatal intensive care, reduced working hours for trainees, increased numbers of trainees, and changes in clinical recommendations, such as to discontinue routine intubation of babies delivered through meconium‐stained liquor.

Studies evaluating success rates for neonatal endotracheal intubation report that more than one attempt is frequently required for successful intubation. An Australian study (O'Donnell 2006) reported that 62% of total first intubation attempts were successful, but the success rate was only 24% among the most inexperienced trainees. In a study conducted in the United States (Falck 2003), paediatric residents successfully intubated neonates on the first or second attempt at rates of 50%, 55%, and 62% for first‐, second‐, and third‐year residents, respectively. None of these residents met the study authors’ definition of procedural competence for intubation (successful at first or second attempt 80% or more of the time) over a two‐year period. Another American study examining intubation success rates over a 10‐year period (Leone 2005) reported median success rates of 33% for first‐year residents, 40% for second‐ or third‐year residents, and 68% for neonatal fellows. Success rates were significantly different between groups (P < 0.001), but success rates for paediatric residents were not significantly different for delivery room (DR) non‐meconium intubations than for neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) intubations (36% vs 36.5%). The most recent US study examining endotracheal intubation success rates (Haubner 2013) reported an overall success rate of 44%. Investigators again found significant differences between experienced and inexperienced providers – residents 20%, fellows 72%, and attending physicians 70%. Researchers observed that participant characteristics of birth weight and gestation did not impact success rates. Studies of intubation performed at US tertiary academic centres by neonatologists, fellows, residents, and respiratory therapists, in which detection of exhaled carbon dioxide was used to confirm correct tube placement, suggest that oesophageal intubation is not infrequent (Roberts 1995; Aziz 1999; Repetto 2001; Lane 2004). Inability to successfully perform ETT placement, or delayed recognition of unsuccessful placement, can cause death or severe hypoxic injury. Multiple intubations or traumatic intubations increase the risk of serious glottic, subglottic, and tracheal injury (Meneghini 2000; Wei 2011).

The current Neonatal Resuscitation Program 7th Edition (AAP 2016) recommends that intubation attempts should be limited to 30 seconds. This has been expanded from the 20‐second recommendation provided in the 5th Edition (Kattwinkel 2006) following a study of delivery room intubations performed mainly by residents and fellows (Lane 2004), which found that a more realistic time needed for intubation was 30 seconds without apparent adverse effects.

Studies have demonstrated that premedicating infants with various types of induction agents increases the speed of successful intubation and reduces the likelihood of associated adverse sequelae (Marshall 1984; McAuliffe 1995; Cook‐Sathler 1998). Premedication has been shown to improve intubating conditions significantly and to reduce the number of attempts required for successful intubation and risk of intubation‐related airway trauma.(Dempsey 2006; Roberts 2006; Carbajal 2007; Ghanta 2007; Silva 2007; Lemyre 2009).

Strategies for improving training are being developed to compensate for the reduced clinical experience of practitioners. Airway trainers, animal models, and cadaveric specimens are useful for demonstrating the anatomy (Haubner 2013). Simulation is a tool that is used increasingly in medical education. However, studies that examined the role of simulation in teaching intubation (Nishiasaki 2010; Finan 2012) did not report improved clinical performance. Videolaryngoscopy (use of a laryngoscope to transmit images from the tip of the blade to a nearby monitor) allows the teacher to share the view of the trainee intubator and may be useful for improving intubation success.

Description of the intervention

As small‐diameter ETTs are flexible, intubation may be performed with or without a stylet inserted into the lumen (hollow centre of the ETT) and secured. A neonatal stylet is a 6 French (2‐mm diameter) malleable aluminium wire covered with lubricated plastic, which extends beyond the tip (Rusch Flexi‐Slip™ Stylet, Teleflex Medical, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA; Satin‐Slip Stylet, Mallinckrodt Medical, Athlone, Ireland). Available stylets are suitable for use with tubes of 2.5‐mm internal diameter and greater. The stylet is positioned so that its tip does not extend beyond the tip of the tube. The proximal (top) end of the ETT is attached to a plastic adapter that connects to the ventilator. The stylet is threaded through the adapter into the ETT and is positioned so that the tip of the stylet does not extend beyond the tip of the tube. The proximal end of the stylet is then bent over the rim of the adapter to prevent further slipping of the stylet. Endotracheal tubes for neonates are made of pliable plastic and have a small internal diameter of 2.0 mm to 4.0 mm. They become increasingly flexible with decreasing internal diameter, especially if exposed to the heat of an overhead radiant warmer. A stylet may increase the rigidity and curvature of the tube, perhaps making it easier to navigate between vocal cords. Current guidelines (Richmond 2011; AAP 2016) do not recommend routine use of a stylet for orotracheal intubation but rather classify it as an optional instrument. Some operators may prefer the rigidity and curvature afforded by this technique and may achieve higher success rates. However, this rigidity could provide a disadvantage and may cause airway damage. Published case reports have described shearing off of the stylet sheath, causing acute airway obstruction (Cook 1985; Zmyslowski 1989; Bhargava 1998; Rabb 1998; Boyd 1999; Chiou 2007). Stylet costs are similar to those of an endotracheal tube.

How the intervention might work

A stylet increases the rigidity of the ETT and may facilitate placement within the airway.

Why it is important to do this review

Neonatal intubation is a commonly needed life‐saving intervention. Success rates, especially among inexperienced trainees, are suboptimal. If use of a stylet could improve intubation success, then it should be recommended for routine use. However, if use of a stylet does not improve success, or if its use may cause harm, it should not be recommended.

Objectives

To compare the benefits and harms of neonatal orotracheal intubation with a stylet versus neonatal orotracheal intubation without a stylet.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs, and cluster RCTs.

Types of participants

We defined our population as infants of 44 weeks' postmenstrual age or less who required endotracheal intubation. Infants who were intubated on more than one occasion were included again for subsequent intubation episodes, and we included only the first intubation attempt per episode. We excluded studies that enrolled infants with craniofacial or airway anomalies and those that enrolled infants born through meconium‐stained liquor who were intubated for tracheal suctioning, owing to difficulty confirming ETT placement within the trachea.

Types of interventions

Orotracheal intubation performed with a stylet versus without a stylet.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Rate of successful first attempt at orotracheal intubation

An attempt was defined as introduction of the ETT into the infant's mouth after laryngoscopy. Successful placement within the tracheobronchial tree was confirmed immediately post intubation attempt, objectively, through a predetermined method, for example, by observation of colour change on an exhaled colorimetric carbon dioxide detector, misting within the ETT, or auscultation of the chest.

Secondary outcomes

-

Duration of the intubation in seconds

This measures time from insertion until removal of the laryngoscope

Number of intubation attempts

-

Patient instability during the procedure, as measured by:

heart rate (HR) < 100 during the procedure; and

desaturation to < 70% (with 100% showing full oxygen saturation).

Local trauma to the airway or surrounding soft tissue diagnosed by the presence of blood‐stained endotracheal aspirates or oral sections over the 24 hours after the attempt (number per thousand infant population)

Evidence of airway damage, for example, post‐extubation stridor, subglottic stenosis, or vocal cord paralysis (number per thousand infant population)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Two review authors independently searched electronic databases, including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 3) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (1966 to April 2017); Embase (1980 to April 2017); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; 1982 to April 2017). We also searched previous reviews including cross‐references, contacted expert informants, and handsearched journals. We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL for relevant articles, using the following search terms: (intubation AND stylet) OR (intubation (explode) [MeSH heading] AND stylet) plus database specific limiters for neonates and randomised controlled trials (see Appendix 1). We applied no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

The search strategy included communication with expert informants and searches of bibliographies of systematic reviews and trials for references to other trials. We examined previous reviews, including cross‐references, abstracts, and conferences, and symposium proceedings of the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand and of the Pediatric Academic Societies (American Pediatric Society, Society for Pediatric Research, and European Society for Pediatric Research) from 1990 to 2015. If we were to identify any unpublished trial, we planned to contact study author to request information. We considered unpublished studies and studies reported only as abstracts as eligible for inclusion in the review if study authors reported final trial data and did not perform an interim analysis. We planned to contact the authors of identified RCTs to ask for additional study data when needed. We searched clinical trial registries to April 2017 for current and recently completed trials (clinicaltrials.gov; controlled‐trials.com; who.int/ictrp), as well as the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Register (ANZCTR).

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Collaboration, as documented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a), and of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group (CNRG).

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed all studies identified via the search strategy for possible inclusion in the review. We planned to resolve disagreements through discussion or, if required, through consultation with a Cochrane review arbiter.

Specifically, we performed the following tasks.

Merged search results by using reference management software and removed duplicate records of the same report.

Examined titles and abstracts to remove irrelevant reports.

Retrieved full texts of potentially relevant reports.

Linked multiple reports of the same study.

Examined full‐text reports for study compliance with eligibility criteria.

Corresponded with investigators, when appropriate, to clarify study eligibility.

Noted reasons for inclusion and exclusion of articles at all stages (we resolved disagreements through consensus, or sought assistance with arbitration from the editorial base of the CNRG, if needed).

Made final decisions on study inclusion and proceeded to data collection.

Resolved all discrepancies through a consensus process.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from full‐text articles using a specially designed spreadsheet to manage the information. We resolved discrepancies through discussion, or, if required, we planned to consult a review arbiter. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked them for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was missing or unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to clarify and provide additional details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the standardised review methods of the CNRG (http://neonatal.cochrane.org/en/index.html) to assess the methodological quality of included studies. Review authors independently assessed study quality and risk of bias using the criteria documented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). See Appendix 2 for the 'Risk of bias' tool.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed the results of included studies using the statistical package Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used the standard method of the CNRG and applied a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis (Deeks 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis is an intubation attempt. We included the first attempt for each intubation episode. We excluded further attempts by the same intubator or by other intubators. A participant who had more than one intubation episode could be included more than once; however, we would treat each intubation as a separate study event and would randomise it separately. We planned to combine cluster‐RCTs and individually randomised RCTs in a single meta‐analysis using the generic inverse variance method. We planned to adjust cluster‐RCTs for their intracluster correlation coefficient.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to use RevMan 5.3 (RevMan 2014) to assess the heterogeneity of treatment effects between trials. We planned to use the two formal statistics described below.

Chi2 test for homogeneity. We planned to calculate whether statistical heterogeneity was present by performing the Chi2 test for homogeneity (P < 0.1). As this test has low power when the number of studies included in the meta‐analysis is small, we set probability at the 10% level of significance (Deeks 2011).

I2 statistic to ensure that pooling of data was valid (Higgins 2003). We planned to quantify the impact of statistical heterogeneity by using I2 statistics available in RevMan 2014, which describe the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than to sampling error. We planned to grade the degree of heterogeneity as follows: < 25% no heterogeneity, 25% to 49% low heterogeneity, 50% to 74% moderate heterogeneity, and ≥ 75% high heterogeneity.

When we found evidence of apparent or statistical heterogeneity, we planned to assess the source of the heterogeneity by performing sensitivity and subgroup analyses to look for evidence of bias or methodological differences between trials.

Data synthesis

We performed statistical analyses according to the recommendations of CNRG (http://neonatal.cochrane.org/en/index.html). We analysed all infants randomised on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis. We planned to analyse treatment effects in individual trials and planned to use a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis in the first instance to combine data. When we noted substantial heterogeneity, we planned to examine the potential cause of heterogeneity by performing subgroup and sensitivity analyses. If we judged meta‐analysis to be inappropriate, we planned to analyse and interpret individual trials separately. For estimates of typical risk ratio (RR) and risk difference (RD), we planned to use the Mantel‐Haenszel (MH) method (Mantel 1959; Greenland 1985). For measured quantities, we planned to use the inverse variance method. When assessing treatment effects, we used RR and RD, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for dichotomous outcomes. When the RD was statistically significant, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) (1/RD). For outcomes measured on a continuous scale, we used mean difference (MD) with 95% CI.

Quality of evidence

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the quality of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes: first intubation attempt success rate; first attempt success rate for intubations without premedication; first attempt success rate for intubations with premedication; first attempt success rate for experienced intubators; first attempt success rate for inexperienced intubators; and first attempt success rate for intubations in infants weighing less than 1 kilogram.

We considered evidence from RCTs as high quality but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations according to the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of evidence, precision of estimates, and presence of publication bias.

The GRADE approach provides an assessment of the quality of a body of evidence according to one of four grades.

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to the estimate of effect.

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect but may be substantially different.

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of the evidence for each of the outcomes above. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create a ‘Summary of findings’ table to report evidence quality.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We carried out the following subgroup analyses.

Gestational age: < 28 weeks, 28 to 37 weeks, ≥ 37 weeks.

Professional category of person performing intubation: neonatologists, neonatal fellows, resident doctors, respiratory therapists, nurses, and neonatal nurse practitioners.

Level of experience of intubators: < 1 year, 1 to 4 years, ≥ 5 years.

Premedications: intubations for which premedication is given; intubations performed without premedications.

Timing of intubation: during resuscitation following birth; during neonatal intensive care stay.

Type of stylet used: a plastic‐coated malleable wire inserted into the ETT; any other type of stylet.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

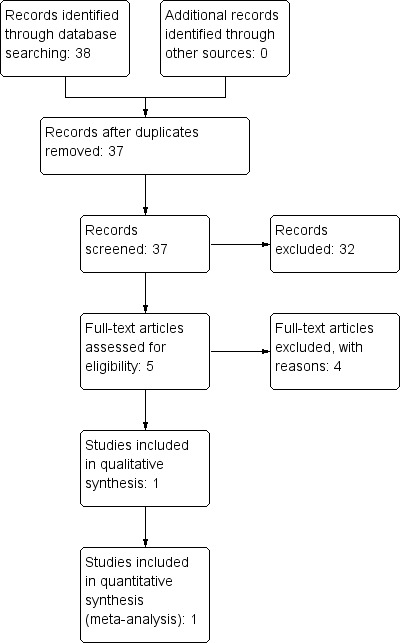

For this review, we found and assessed 38 titles and abstracts in electronic format after we had removed duplicates. Of the 38 titles and abstracts screened, we assessed five as relevant, and one study met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1, Study flow diagram).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Kamlin 2013 is a single‐centred RCT conducted at an Australian tertiary neonatal unit between July 2006 and January 2009. The study included 304 first intubation attempts in 232 infants.

Intervention: Investigators randomised intubations to use of a stylet inserted into the ETT lumen or no stylet inserted. ETTs used were sterile, single‐use, uniform internal diameter (ID), plastic ETTs (Mallinckrodt Medical, Athlone, Ireland) of appropriate ID based on infants' actual or estimated birth weight; the stylet used was a Satin Slip intubation stylet (Malinckrodt Medical, Athlone, Ireland). Researchers confirmed correct ETT placement by using a colourimetric exhaled carbon dioxide detector (Pedicap, Nellcor Puritan Bennett, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Infants admitted to the NICU had a chest radiograph to confirm ETT position. Study authors recorded the level of experience of the operator, as well as the operator's preference (i.e. stylet, no stylet, no preference).

Investigators randomised the first attempted intubation by a single operator. If unsuccessful, the operator was free to choose his or her preferred method for subsequent attempts. Doctors performed all intubations. In general, residents had no previous intubation experience, whereas fellows had at least 12 months' experience in neonatal intensive care. Researchers defined an attempted intubation as laryngoscopy followed by introduction of the ETT past the lips. They defined the duration of an attempt, timed by a digital stop watch, as the interval from introduction of the laryngoscope blade into the mouth to its removal. Intubation attempts were limited by the infant's heart rate (> 100 beats per minute deemed acceptable) rather than by a time limit. Study authors obtained baseline readings for heart rate and pulse oxygen saturations by using a pulse oximeter and recorded the lowest heart rate and oxygen saturations during the attempt.

Investigators did not use premedication for emergency intubations following delivery. They used premedication with morphine or fentanyl, atropine, and suxamethonium for elective intubations within the NICU. During the course of the study, researchers updated hospital guidelines and replaced morphine with fentanyl.

Participants: Infants requiring orotracheal intubation were eligible for study inclusion. Excluded infants had facial or airway anomalies or were briefly intubated for suctioning of meconium from the trachea, as tube placement was difficult to confirm. The first attempted intubation of each intubation episode was eligible for randomisation. Therefore, if an infant was intubated again later during the inpatient course, researchers could randomise further intubations.

Outcomes: The primary outcome was intubation success on first attempt indicated by detection of exhaled carbon dioxide. Secondary outcomes included duration of the intubation attempt, changes in heart rate and oxygen saturation from baseline, and the presence of blood‐stained secretions after the procedure. Prespecified subgroup analyses examined the effects of gestation, birth weight, premedication, and level of experience of the operator on intubation success.

Excluded studies

We excluded four potentially relevant studies from this original review because study design did not meet the criteria for included studies. We excluded two studies that did not randomise infants to the assigned treatment – one that was a case series (Shukry 2005), and another that was a prospective observational trial (Fisher 1997). We excluded two other RCTs, as the comparisons did not match our criteria: MacNab 1998 compared three different types of stylets but did not include a 'no‐stylet' arm; Yamashita 2015 compared two different methods of confirming that the ETT was in the trachea ‐ not the main‐stem bronchus.

Risk of bias in included studies

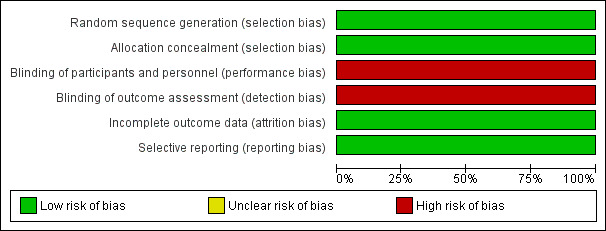

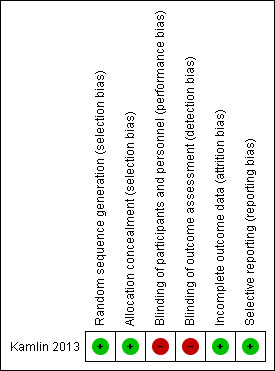

We deemed the included study to be at low risk of bias overall. See the risk of bias graph (Figure 2) and summary (Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Investigators performed randomisation in blocks of variable size, stratified by site of intubation (delivery room or NICU) (low risk of bias for generation of random sequence).

Researchers concealed allocation by using sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes containing computer‐generated treatment groups (low risk of bias). The neonatal fellow on duty would bring an unopened sealed envelope to the delivery room to randomise the next eligible infant. Infants in the NICU were identified by a study label placed on the incubator.

Blinding

This unblinded trial did not perform blinded outcome assessment (high risk of bias).

Incomplete outcome data

Researchers presented a complete flow chart for all intubations performed during the study period. They accounted for all exclusions and missed eligibles and for two post‐randomisation exclusions (low risk of bias).

Selective reporting

The study protocol is available, and study authors reported all prespecified primary and secondary outcomes (low risk of bias).

Other potential sources of bias

We identified no other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

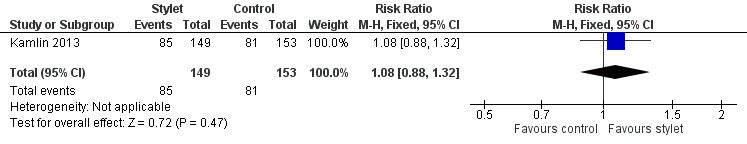

Rate of successful first attempt at orotracheal intubation (Analysis 1.1)

Intubation was successful on the first attempt in 57% of the stylet group and in 53% of the no‐stylet group (P = 0.47; RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.32) (Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 First intubation attempt success rate with use of stylet versus non‐use of stylet, outcome: 1.1 First intubation attempt success rate.

Subgroup analyses

Gestational age: < 28 weeks, 28 to 37 weeks, ≥ 37 weeks; analysis was not possible owing to lack of data

Professional category of person performing intubation

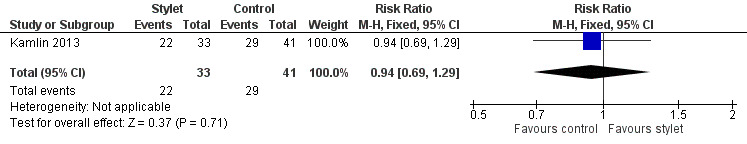

Success by fellows was 67% with a stylet and 71% without a stylet (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.29) (Analysis 2.1;Figure 5)

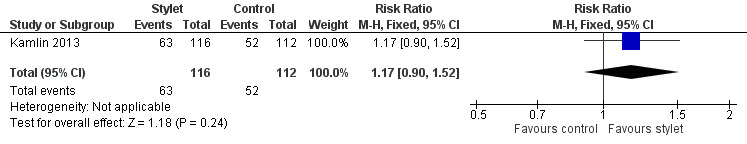

Success by residents was 54% with a stylet and 46% without a stylet (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.52) (Analysis 2.2;Figure 6)

Doctors carried out all intubations in Kamlin 2013

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intubation success: professional category, Outcome 1 Fellow: first intubation attempt success rate.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Intubation success: Professional category, outcome: 2.1 Fellow: first intubation attempt success rate.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intubation success: professional category, Outcome 2 Resident: first intubation attempt success rate.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Intubation success: Professional category, outcome: 2.2 Resident: first intubation attempt success rate.

Level of experience of intubators ‐ analysis was not possible owing to lack of data

Effect of premedication

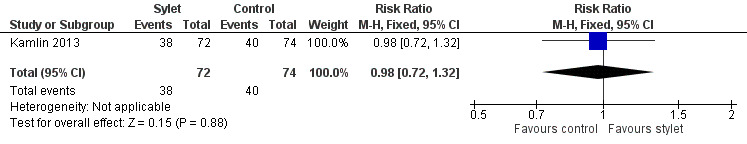

Success rate without premedication was 53% with a stylet and 54% without a stylet (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.32) (Analysis 3.1Figure 7)

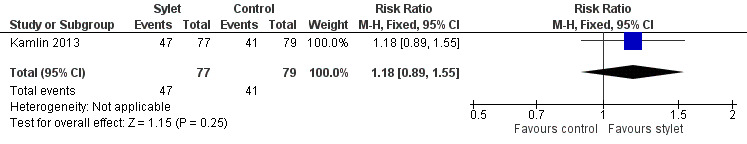

Success rate with premedication was 61% with a stylet and 52% without a stylet (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.55) (Analysis 3.2Figure 8)

-

Timing of intubation.

Success rate during resuscitation following birth was 53% with a stylet and 54% without a stylet (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.32) (Analysis 4.1)

Success rate during neonatal intensive care stay was 61% with a stylet and 52% without a stylet (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.55) (Analysis 4.2)

-

Type of stylet

Success rate with Satin Slip intubation stylet was 57% in the stylet group and 53% in the no‐stylet group (P = 0.47; RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.32) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4)

-

Weight of infant at the time of intubation

Success in infants weighing less than 1 kilogram at the time of intubation was 53% with a stylet and 60% without a stylet (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.18) (Analysis 5.1)

Success in infants weighing 1 kilogram or more at the time of intubation was 61% with a stylet and 46% without a stylet (RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.79) (Analysis 5.2)

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Intubation success: use of premedication, Outcome 1 Intubations without premedication given to the infant.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Intubation success: use of premedication, outcome: 3.1 Intubations without premedication given to the infant.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Intubation success: use of premedication, Outcome 2 Intubations following premedication given to the infant.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Intubation success: use of premedication, outcome: 3.2 Intubations following premedication given to the infant.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Intubation success: timing of intubation, Outcome 1 Intubations just after birth in the delivery room: first intubation attempt success rate.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Intubation success: timing of intubation, Outcome 2 intubations following admission to NICU: first intubation attempt success rate.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 First intubation attempt success rate with use of stylet vs non‐use of stylet, Outcome 1 First intubation attempt success rate.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Intubation success: weight at intubation, Outcome 1 Weight < 1000 grams.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Intubation success: weight at intubation, Outcome 2 Weight ≥ 1000 grams.

Secondary outcomes

Duration of the intubation in seconds

The median duration of intubation attempts was similar in the two groups: 43 (interquartile ratio (IQR) 30 to 60) and 38 (IQR 27 to 57) seconds for stylet and no‐stylet groups (P = 0.23), respectively. Only 25% of all intubations took less than 30 seconds.

Number of intubation attempts

The median number of intubation attempts reported per infant before an ETT was successfully passed was one (range 1 to 5). Difficult airways appear to have been equally represented, with eight randomisations in each of the stylet and no‐stylet groups requiring four or more attempts before successful intubation.

Participant instability during the procedure

Investigators measured participant instability during the procedure by assessing:

heart rate (HR) < 100 during the procedure; and

desaturation to < 70% (with 100% indicating full oxygen saturation).

In Kamlin 2013, trial pulse oximetry data were available for 277 intubation attempts in 215 infants (121 in DR, 156 in NICU). Investigators reported no significant differences between groups in lowest recorded oxygen saturation and heart rate during randomised attempts in the DR and the NICU, respectively. The mean lowest heart rate recorded for the stylet group was 128 beats per minute (standard deviation (SD) 36) compared with 121 (SD 37) for the non‐stylet group. Only one infant in the trial received chest compressions. This infant had an antenatal diagnosis of tricuspid atresia and was randomised to the no‐stylet group. No published data were available with regards to lowest oxygen saturation for the stylet group versus the non‐stylet group during intubation attempts.

Local trauma to the airway or surrounding soft tissue

Researchers diagnosed local trauma to the airway or surrounding soft tissue by the presence of blood‐stained endotracheal aspirates or oral sections during the 24 hours following the attempt (number per thousand infant population). Rates of blood‐stained aspirates within the first 24 hours were 10% and 13% (P = 0.49) in stylet and no‐stylet groups, respectively.

Evidence of airway damage

As some infants were randomised more than once (8% of infants) and were allocated to both groups, Kamlin 2013 did not report neonatal morbidity and mortality data. Of note, no participants were reported to have had tracheal or oesophageal perforation following intubation attempts.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Of 38 titles screened, we included one study with a total of 304 first intubation attempts in 232 infants (Kamlin 2013). This study, an unblinded randomised controlled trial (RCT) carried out in an Australian tertiary perinatal centre, compared use of a stylet as an aid during intubation of the newborn infant versus intubation without use of a stylet. The included trial assessed the primary outcome and most of the secondary outcomes of this review, while excluding assessment of airway damage. The salient result from this included trial suggests that using a stylet did not significantly improve the success rate of paediatric trainees in performing neonatal orotracheal intubation when compared with intubation performed without using a stylet. Results reported were consistent across subgroups according to site of intubation and birth weight of the infant. Investigators reported no serious side effects resulting from intubation with the use of a stylet.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The effectiveness of stylet use during intubation has been evaluated in only one study, which evaluated the use of one particular make of stylet (Stain Slip intubation stylet, Malinckrodt Medical, Athlone, Ireland), one brand of endotracheal tube, in one country, by doctors with a minimum of six months' neonatal experience, among a population of newborn infants. Thus, results cannot be generalised beyond this population and use of this particular make of stylet in a hospital setting.

Quality of the evidence

We assessed the quality of evidence using GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methods (Guyatt 2008). We judged the included study to be at low risk of bias overall. We stratified randomisation in blocks of variable size by site of intubation (delivery room or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)). In terms of allocation concealment, researchers used sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes containing computer‐generated treatment groups to determine allocation status. Study authors provided no evidence of incomplete outcome data. Researchers accounted for infants and eligible intubations that were excluded and provided reasons for these exclusions. Exclusions after randomisation were minimal. The study protocol was available, and all prespecified outcomes were reported as intended.

One limitation of this study is that the trial was unblinded. Hospital staff and family members were unblinded to the intervention, and no evidence suggests that a blinded outcome assessment was conducted. It is unclear if the trial would have been improved by blinding of outcome assessment because of the objective nature of measured outcomes. The study is also limited in that investigators tested one brand of stylet and one brand of endotracheal tube. Endotracheal tubes likely have different degrees of rigidity. A more rigid tube may hold its shape better, and practitioners may note less benefit with use of a stylet, whereas a more floppy flexible tube may not hold its shape, and use of a stylet may be beneficial. Results show no differences in the incidence of blood‐stained endotracheal aspirates between groups. However, if the initial attempt was unsuccessful, a stylet was used for subsequent attempts, at the clinician's discretion. This result should be interpreted cautiously. Another limitation is that some infants were randomised more than once, and some were included in both study arms. This makes assessment of longer‐term outcomes impossible. In addition, inclusion of the same participant more than once leads to reduced power of the trial because of lack of independence of each intubation studied. This is somewhat ameliorated by the fact that premature infants are an atypical population that changes rapidly as the result of rapid growth (thereby posing different challenges for the operator) and changes to the upper airway resulting from each intubation and perhaps from steroid therapy. Therefore, a later intubation may be considered an independent event. Data were also derived from a single study with a moderately small number of participants.

We downgraded the quality of evidence to low for these reasons.

Potential biases in the review process

We conducted a thorough search of the literature and did not apply language restrictions to minimise selection bias. We conducted the review robustly, according to good systematic review standards. It is unlikely that we have overlooked relevant high‐quality large studies examining use versus non‐use of a stylet during intubation of the newborn infant. Therefore, we believe that the probability of bias in the review process is low.

A potential source of bias in the review as a whole is that three of the contributing authors of this Cochrane review and protocol are authors of the included study.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No other neonatal studies have examined whether a stylet can increase intubation success rates.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found no evidence to support the use of a stylet.

Implications for research.

Neonatal intubation success rates are falling, especially those of junior trainees (Leone 2005). It is unlikely that future trials examining the use of stylets will present findings that will reverse this trend. Therefore, further research could focus on other variables that may influence intubation success to a greater degree, for example, educational interventions such as simulation or videolaryngoscopy. As opportunities for trainees to learn and practice neonatal intubation continue to decline, it is vital that training techniques are developed and intubation attempt success rates are continually audited to assess the effects of such training.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 7, 2015 Review first published: Issue 6, 2017

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 November 2007 | New citation required and major changes | We made substantive amendments |

Appendices

Appendix 1. Standard search methods

MEDLINE: ((infant, newborn[MeSH] OR newborn OR neonate OR neonatal OR premature OR low birth weight OR VLBW OR LBW or infan* or neonat*) AND (randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized [tiab] OR placebo [tiab] OR drug therapy [sh] OR randomly [tiab] OR trial [tiab] OR groups [tiab]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT humans [mh]))

Appendix 2. Risk of bias tool

We used the 'Risk of bias' table, which addresses the following questions.

Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? For each included study, we categorised the method used to generate the allocation sequence as low risk (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator); unclear risk; or high risk (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). Was allocation adequately concealed? For each included study, we categorised the method used to conceal the allocation sequence as low risk (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes); unclear risk; or high risk (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth).

Blinding (checking for possible performance bias). Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study, at study entry, or at the time of outcome assessment? For each included study, we categorised the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes. We categorised the methods as low risk, high risk, or unclear risk for participants; low risk, high risk, or unclear risk for outcome assessors; low risk, high risk, or unclear risk for personnel.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations). Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? For each included study, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We also noted reasons for attrition and exclusions if possible. We categorised the methods as low risk (< 20% missing data); unclear risk; or high risk (≥ 20% missing data).

Selective reporting bias. Were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? We planned to contact study authors, asking them to provide missing outcome data, when we suspected reporting bias. For each included study, we planned to describe how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias. We planned to assess the methods as low risk (when it is clear that all of the study's prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported); unclear risk; or high risk (when not all of the study's prespecified outcomes have been reported).

Other sources of bias. Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias? For each included study, we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias (e.g. whether a potential source of bias was related to the specific study design, whether the trial was stopped early owing to some data‐dependent process). We also assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias as low risk; unclear risk; or high risk.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. First intubation attempt success rate with use of stylet vs non‐use of stylet.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 First intubation attempt success rate | 1 | 302 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.88, 1.32] |

Comparison 2. Intubation success: professional category.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fellow: first intubation attempt success rate | 1 | 74 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.69, 1.29] |

| 2 Resident: first intubation attempt success rate | 1 | 228 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.90, 1.52] |

Comparison 3. Intubation success: use of premedication.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Intubations without premedication given to the infant | 1 | 146 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.72, 1.32] |

| 2 Intubations following premedication given to the infant | 1 | 156 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.89, 1.55] |

Comparison 4. Intubation success: timing of intubation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Intubations just after birth in the delivery room: first intubation attempt success rate | 1 | 146 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.72, 1.32] |

| 2 intubations following admission to NICU: first intubation attempt success rate | 1 | 156 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.89, 1.55] |

Comparison 5. Intubation success: weight at intubation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Weight < 1000 grams | 1 | 152 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.67, 1.18] |

| 2 Weight ≥ 1000 grams | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.97, 1.79] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Kamlin 2013.

| Methods |

Objective: to determine whether paediatric trainees were more successful at neonatal orotracheal intubation when a stylet was used Study design: unblinded randomised controlled trial Object of randomisation: first intubation attempt; for infants who had more than 1 episode of intubation during admission, each episode of intubation was randomised and was treated as an independent event Recruitment: For emergency first intubations in the delivery room or within 24 hours of birth, a waiver of consent was used to enrol infants, and retrospective consent was obtained from parents as soon as possible after the intubation attempt. Infants who were intubated in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) after the first day were eligible if written parental consent had been obtained. Permission from parents was also sought to randomise future intubations Allocation: randomly assigned Total number of intubations: 713 Number of infants randomised: 232 Number of intubations randomised: 304 Method of analysis: Data are presented as means (standard deviations) for normally distributed continuous variables and medians (interquartile ranges) when the distribution is skewed. Clinical characteristics and outcome variables were analysed by using Student's t test for parametric comparisons, the Mann‐Whitney U test for non‐parametric comparisons of continuous variables, and X2 for categorical variables. P values were 2‐sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant Follow‐up: No participants had tracheal or oesophageal perforation. Rates of blood‐stained aspirates within the first 24 hours were included as a secondary outcome. No information on follow‐up was provided beyond this |

|

| Participants |

Country: Australia Clinical setting: delivery room and neonatal intensive care unit Inclusion criteria: Eligible participants were newborn infants in the delivery room or NICU requiring endotracheal intubation Exclusion criteria: Infants who were intubated for suctioning of meconium from the trachea were not eligible owing to the difficulty of confirming correct endotracheal tube (ET) placement Age (weeks): mean gestational age of participants: stylet = 28.5 (standard deviation (SD) 5.0); no stylet = 28.7 (SD 5.2) Birth weight (grams): stylet = 925 (interquartile ratio (IQR) 689 to 1473); no stylet = 862 (IQR 714 to 1586) Gender: male infants: stylet = 86 (SD 58); no stylet = 92 (SD 60) Ethnicity: not stated Site of intubation: delivery room (DR): stylet n = 72; no stylet n = 74; NICU: stylet n = 77; NICU n = 79 Seniority of operator: fellow: stylet 33 (SD 11); no stylet 41 (SD 14); resident: stylet 116 (SD 38); no stylet 112 (SD 37) |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention arm: A stylet was used as an aid during orotracheal intubation of the newborn infant Control arm: orotracheal intubation of the newborn infant without the use of a stylet |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome Intubation success rates on first attempt with use of stylet vs non‐use as indicated by detection of exhaled carbon dioxide Secondary outcomes • Duration of intubation attempt • Changes in heart rate and oxygen saturation from baseline • Presence of blood‐stained secretions after the procedure |

|

| Notes | Trial registration: Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Register (ACTR identifier: 12607000186459) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Intervention was assigned by random sequence. Randomisation occurred in blocks of variable size stratified by site of intubation (delivery room (DR) or neonatal intensive care (NICU)) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Upcoming allocations were concealed from those involved in enrolment of the trial. Sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes contained computer‐generated treatment groups, which the neonatal fellow on duty carried to the DR unopened to randomise the next eligible infant in the DR. Infants in the NICU were identifiable by a study label on the incubator |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Study was unblinded with regards to intervention allocation. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to mask hospital staff or parents/guardians of the infant to the allocation status |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Assessors of outcomes were unblinded to intervention allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Reasons for excluded infants (n = 481): intubated for meconium/before fellow arrived (n = 102); forgot/team thought ineligible (n = 264); other reasons, e.g. emergencies, twins, nasal intubation, consultant intubation (n = 115). Eligible intubations that were excluded were accounted for and explained (n = 21). These were consented for prospective NICU intubations, but the team was unaware or had insufficient time owing to emergency intubation required |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Study protocol is available, and all prespecified primary and secondary outcomes have been reported in the prespecified way |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Fisher 1997 | Prospective observational study |

| MacNab 1998 | Comparison of lighted vs regular stylet ‐ not of stylet vs no stylet |

| Shukry 2005 | Non‐experimental study: case report |

| Yamashita 2015 | Randomised controlled trial comparing transillumination method vs main‐stem method |

Differences between protocol and review

We added the methods and plan for 'Summary of findings' tables and GRADE recommendations, which were not included in the original protocol. We added infant weight to the subgroup analysis.

Contributions of authors

Joyce O'Shea: amended the protocol and co‐wrote the review. Jennifer O'Gorman: co‐wrote the review. Aakriti Gupta: wrote the first draft of the protocol. Sanjay Sinhal: supervised the first draft of the protocol. Jann Foster: contributed to the content of the review. Liam O'Connell: contributed to the content of the review. Camille Omar Farouk Kamlin: contributed to the content of the review. Peter Davis: supervised development of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Royal Women's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

University of Melbourne, Australia.

External sources

National Health and Medical Reseach Council, Australia.

-

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, USA.

Editorial support of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group has been funded by Federal funds from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, USA, under Contract No. HHSN275201600005C

Declarations of interest

Joyce O'Shea: nothing to declare. Jennifer O'Gorman: nothing to declare. Aakriti Gupta: nothing to declare. Sanjay Sinhal: nothing to declare. Jann Foster: nothing to declare. Liam O'Connell: co‐investigator on a trial that was eligible for inclusion in this review. Camille Omar Farouk Kamlin: co‐investigator on a trial that was eligible for inclusion in this review. Peter Davis: co‐investigator on a trial that was eligible for inclusion in this review.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Kamlin 2013 {published data only}

- Kamlin CO, O’Connell LA, Morley CJ, Dawson JA, Donath SM, O’Donnell CPF, et al. A randomized trial of stylets for intubating newborn infants. Pediatrics 2013;131(1):e198‐205. [DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-0802; PUBMED: 23230069] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Fisher 1997 {published data only}

- Fisher QA, Tunkel DE. Lightwand intubation of infants and children. Journal of Clinical Anaesthesia 1997;9(4):275‐9. [PUBMED: 9195348] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MacNab 1998 {published data only}

- MacNab AJ, MacPhail I, MacNab MK, Noble R, O'Flaherty D. A comparison of intubation success for paediatric transport team paramedics using lighted vs regular tracheal tube stylets. Paediatric Anaesthesia 1998;8(3):215‐20. [PUBMED: 9608966] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shukry 2005 {published data only}

- Shukry M, Hanson RD, Koveleskie JR, Ramadhyani U. Management of the difficult pediatric airway with Shikani Optical Stylet. Paediatric Anaesthesia 2005;15(4):342‐5. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01435.x; PUBMED: 15787929] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yamashita 2015 {published data only}

- Yamashita S, Takahashi S, Osaka Y, Fujikura K, Tabata K, Tanaka M. Efficacy of the transillumination method for appropriate tracheal tube placement in small children: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia 2015;27(1):12‐6. [doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2014.09.003; PUBMED: 25457173] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

AAP 2016

- American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association. Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation (NRP). 7th Edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Aziz 1999

- Aziz HF, Martin JB, Moore JJ. The pediatric disposable end‐tidal carbon dioxide detector role in endotracheal intubation in newborns. Journal of Perinatology 1999;19(2):110‐3. [PUBMED: 10642970] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bhargava 1998

- Bhargava M, Pothula SN, Joshi S. The obstruction of an endotracheal tube by the plastic coating sheared from a stylet: a revisit. Anesthesiology 1998;88(2):548‐9. [PUBMED: 9477085] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boyd 1999

- Boyd RL, Bradfield HA, Burton EM, Carter BS. Fluoroscopy‐guided retrieval of a sheared endotracheal stylet sheath from the tracheobronchial tree in a premature infant. Pediatric Radiology 1999;29(8):575‐7. [DOI: 10.1007/s002470050650; PUBMED: 10415179] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carbajal 2007

- Carbajal R, Eble B, Anand KJ. Premedication for tracheal intubation in neonates: confusion or controversy?. Seminars in Perinatology 2007;31(5):309‐17. [DOI: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.07.006; PUBMED: 17905186] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chiou 2007

- Chiou HL, Diaz R, Orlino E, Poulain FR. Acute airway obstruction by a sheared endotracheal intubation stylet sheath in a premature infant. Journal of Perinatology 2007;27(11):727‐9. [DOI: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211829; PUBMED: 17960145] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cook 1985

- Cook WP, Schultetus RR. Obstruction of an endotracheal tube by the plastic coating sheared from a stylet. Anesthesiology 1985;62(6):803‐4. [PUBMED: 4003804] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cook‐Sathler 1998

- Cook‐Sather SD, Tulloch HV, Cnaan A, Nicolson SC, Cubina ML, Gallagher PR, et al. A comparison of awake versus paralysed tracheal intubation for infants with pyloric stenosis. Anesthesia and Analgesia 1998;86(5):945–51. [PUBMED: 9585274] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2011

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analysis. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Dempsey 2006

- Dempsey EM, Al Hazzani F, Faucher D, Barrington KJ. Facilitation of neonatal endotracheal intubation with mivacurium and fentanyl in the neonatal intensive care unit. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2006;91(4):F279‐82. [DOI: 10.1136/adc.2005.087213; PUBMED: 16464937] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Falck 2003

- Falck AJ, Escobedo MB, Baillargeon JG, Villard LG, Gunkel JH. Proficiency of pediatric residents performing neonatal endotracheal intubation. Pediatrics 2003;112(6 Pt 1):1242‐7. [PUBMED: 14654592] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Finan 2012

- Finan E, Bismilla Z, Campbell C, Leblanc V, Jefferies A, Whyte HE. Improved procedural performance following a simulation training session may not be transferable to the clinical environment. Journal of Perinatology 2012;32(7):539‐44. [DOI: 10.1038/jp.2011.141; PUBMED: 21960126] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ghanta 2007

- Ghanta S, Abdel‐Latif ME, Lui K, Ravindranathan H, Awad J, Oei J. Propofol compared with the morphine, atropine, and suxamethonium regimen as induction agents for neonatal endotracheal intubation: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2007;119(6):E1248‐55. [DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-2708; PUBMED: 17485450] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

GRADEpro GDT [Computer program]

- GRADE Working Group, McMaster University. GRADEpro GDT. Version (accessed 9 April 2016). Hamilton, ON: GRADE Working Group, McMaster University, 2014.

Greenland 1985

- Greenland S, Robins JM. Estimation of a common effect parameter from sparse follow‐up data. Biometrics 1985;41(1):55‐68. [PUBMED: 4005387] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2008

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck‐Ytter Y, Alonso‐Coello P, et al. GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336(7650):924–6. [PUBMED: 18436948] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Haubner 2013

- Haubner LY, Barry JS, Johnston LC, Soghier L, Tatum PM, Kessler D, et al. Neonatal intubation performance: room for improvement in tertiary neonatal intensive care units. Resuscitation 2013;84(10):1359–64. [DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.03.014; PUBMED: 23562374] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557; PUBMED: 12958120] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011a

- Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ (editors). Chapter 7: Selecting studies and collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. handbook.cochrane.org.

Higgins 2011b

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

ILCOR 2005

- International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. 2005 International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Part 7: neonatal resuscitation.. Resuscitation 2005;67(2‐3):293‐303. [DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.09.014; PUBMED: 16324993] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kattwinkel 2006

- Kattwinkel J, Short J, Shavell L, Siede B. Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation. 5th Edition. Elk Grove, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Lane 2004

- Lane B, Finer N, Rich W. Duration of intubation attempts during neonatal resuscitation. Journal of Pediatrics 2004;145(1):67‐70. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.03.003; PUBMED: 15238909] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lemyre 2009

- Lemyre B, Cheng R, Gaboury I. Atropine, fentanyl and succinylcholine for non‐urgent intubations in newborns. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2009;94(6):F439‐42. [DOI: 10.1136/adc.2008.146068; PUBMED: 19307222] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leone 2005

- Leone TA, Rich W, Finer NN. Neonatal intubation: success of pediatric trainees. Journal of Pediatrics 2005;146(5):638‐41. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.029; PUBMED: 15870667] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mantel 1959

- Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1959;22(4):719‐48. [PUBMED: 13655060] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marshall 1984

- Marshall TA, Deeder R, Pai S, Berkowitz GP, Austin TL. Physiologic changes associated with endotracheal intubation in preterm infants. Critical Care Medicine 1984;12(6):501–3. [PUBMED: 6723333] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McAuliffe 1995

- McAuliffe G, Bissonnette B, Boutin C. Should the routine use of atropine before succinylcholine in children be reconsidered?. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia 1995;42(8):724‐9. [DOI: 10.1007/BF03012672; PUBMED: 7586113] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meneghini 2000

- Meneghini L, Zadra N, Metrangolo S, Narne S, Giusti F. Post‐intubation subglottal stenosis in children: risk factors and prevention in pediatric intensive care. Minerva Anestesiologica 2000;66(6):467‐71. [PUBMED: 10961059] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nishiasaki 2010

- Nishiasaki A, Donoghue AJ, Colburn S, Watson C, Meyer A, Brown CA 3rd, et al. Effect of just‐in‐time simulation training on tracheal intubation procedure safety in the pediatric intensive care. Anesthesiology 2010;113(1):214‐23. [DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e19bf2; PUBMED: 20526179] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Donnell 2006

- O'Donnell CP, Kamlin CO, Davis PG, Morley CJ. Endotracheal intubation attempts during neonatal resuscitation: success rates, duration, and adverse effects. Pediatrics 2006;117(1):e16‐21. [DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-0901; PUBMED: 16396845] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Perlman 2010

- Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, Atkins DL, Chameides L, Guinsburg R, et al. Part 11: Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation 2010;122(16 Suppl 2):S516‐38. [DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971127; PUBMED: 20956259] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rabb 1998

- Rabb MF, Larson SM, Greger JR. An unusual cause of partial ETT obstruction. Anesthesiology 1998;88(2):548. [PUBMED: 9477084] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Repetto 2001

- Repetto JE, Donohue PA‐C PK, Baker SF, Kelly L, Nogee LM. Use of capnography in the delivery room for assessment of endotracheal tube placement. Journal of Perinatology 2001;21(5):284‐7. [DOI: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210534; PUBMED: 11536020] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Richmond 2011

- Richmond S, Wyllie J. Newborn Life Support. 3rd Edition. London, UK: Resuscitation Council, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Roberts 1995

- Roberts WA, Maniscalco WM, Cohen AR, Litman RS, Chhibber A. The use of capnography for recognition of esophageal intubation in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatric Pulmonology 1995;19(5):262‐8. [PUBMED: 7567200] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roberts 2006

- Roberts KD, Leone TA, Edwards WH, Rich WD, Finer NN. Premedication for nonemergent neonatal intubations: a randomized, controlled trial comparing atropine and fentanyl to atropine, fentanyl, and mivacurium. Pediatrics 2006;118(4):1583‐91. [DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-0590; PUBMED: 17015550] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schünemann 2013

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. GRADE Working Group. GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html [Updated October 2013].

Silva 2007

- Pereira e Silva Y, Gomez RS, Marcatto Jde O, Maximo TA, Barbosa RF, Simões e Silva AC. Morphine versus remifentanil for intubating preterm neonates. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2007;92(4):F293‐4. [DOI: 10.1136/adc.2006.105262; PUBMED: 17074784] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wei 2011

- Wei JL, Bond J. Management and prevention of endotracheal intubation injury in neonates. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery 2011;19(6):474‐7. [DOI: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32834c7b5c; PUBMED: 21986802] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zmyslowski 1989

- Zmyslowski WP, Kam D, Simpson GT. An unusual cause of endotracheal tube obstruction. Anesthesiology 1989;70(5):883. [PUBMED: 2719333] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]