Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is genetically complex with multifactorial etiology. Here, we aim to identify the potential viral pathogens leading to aberrant inflammatory and oxidative stress response in AD along with potential drug candidates using systems biology approach. We retrieved protein interactions of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and tau protein (MAPT) from NCBI and genes for oxidative stress from NetAge, for inflammation from NetAge and InnateDB databases. Genes implicated in aging were retrieved from GenAge database and two GEO expression datasets. These genes were individually used to create protein-protein interaction network using STRING database (score≥0.7). The interactions of candidate genes with known viruses were mapped using virhostnet v2.0 database. Drug molecules targeting candidate genes were retrieved using the Drug-Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb). Data mining resulted in 2095 APP, 116 MAPT, 214 oxidative stress, 1269 inflammatory genes. After STRING PPIN analysis, 404 APP, 109 MAPT, 204 oxidative stress and 1014 inflammation related high confidence proteins were identified. The overlap among all datasets yielded eight common markers (AKT1, GSK3B, APP, APOE, EGFR, PIN1, CASP8 and SNCA). These genes showed association with hepatitis C virus (HCV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), human herpes virus 8 and Human papillomavirus (HPV). Further, screening of drugs targeting candidate genes, and possessing anti-inflammatory property, antiviral activity along with a suggested role in AD pathophysiology yielded 12 potential drug candidates. Our study demonstrated the role of viral etiology in AD pathogenesis by elucidating interaction of oxidative stress and inflammation causing candidate genes with common viruses along with the identification of potential AD drug candidates.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, neurodegenerative disease, virus infection, genes, drug, protein-protein interaction, systematic review

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common, complex and debilitating neurodegenerative disease affecting mainly elderly population. The disease is characterized by molecular and genetic changes in neurons leading to neuronal degeneration and ultimately brain dysfunction and death [1, 2]. There has been extensive research in the past decade covering diverse aspects of epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, genomics and proteomics related to AD [3]. However, the identification of causal factor, better diagnostic procedures and the disease modifying treatment modalities are still far from reality due to complex, multifactorial and heterogeneous nature of the disease [4]. Most of the AD cases (95%) are of the sporadic type and only age [5, 6] and the possession of the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (APOE ɛ4) [7-10] have been consistently associated with sporadic cases to date. The concordance rate for AD in identical twins has been estimated to be just 59% [11] suggesting that some other factors also contribute in the pathogenic cascade. As the etiology and pathogenesis of AD are still poorly understood, it seems plausible that multiple signalling molecules are involved in the pathogenic cascade with some triggering the disease onset while others are involved in disease progression.

In recent years, chronic infections have been commonly implicated in various complex diseases, including neurodegenerative, neuropsychiatric and other conditions [4, 12-14]. Interestingly, infectious agents may initiate disease pathogenesis by entering central nervous system (CNS) within infected macrophages by transcytosis across the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) or by intraneuronal migration from peripheral nerves [15]. An interesting hypothesis for the causation or progression of complex neurodegenerative disease involves chronic viral infections, which result in aberrant inflammatory response and excess oxidative stress resulting in neurologic signs and symptoms. A number of viral pathogens have been suggested to be associated with cognitive dysfunction seen in AD and vaccination against some of these viruses has been shown to be protective [16, 17]. The interaction between host and viral genes may occur in an integrated manner so as to allow pathogens to contribute to disease in individuals with genetic predisposition, or genes to promote disease in infected populations. This suggests that gene, viruses, and the immune system act together to cause AD, and focus on virus detection and elimination should be a priority in at risk population.

Here, we aim to understand human – viral interaction with a view that host pathogen genetics may provide better clue to the underlying pathogenesis of complex disorders and open new prospects for the better diagnostics and therapeutics. Elucidating the genetic architecture of host–pathogen interactions may help us understand the pathogenic mechanism along with identification of host susceptibility markers. Further, identification of already known drugs which can attenuate the viral mediated oxidative stress and inflammation may also help to halt or reverse the AD pathology.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Mining

As amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary (NFTs) made up of beta-amyloid peptides from amyloid precursor protein (APP) and hyperphosphorylated tau protein (MAPT) respectively, are the neuropathological hallmarks of AD, we retrieved protein interactors of APP and MAPT from NCBI database (date accessed: 12.1.2017). The source of interactant information in NCBI was mainly protein-protein interaction databases such as Biomolecular Interaction Network Database (BIND), Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) and Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BIOGRID) with all interactions supported by a published report. The genes for oxidative stress were retrieved from NetAge [18] (http://www.netage-project.org) and for inflammation associated genes from NetAge and InnateDB [19] (http://www.innatedb.com/) databases. Genes implicated in aging were retrieved from GenAge database and gene expression data from NCBI GEO (GSE46193 and GSE53890) after analyses with NCBI GEO2R tool (top 250 genes) [20] (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/). The extracted genes were filtered if found duplicate and then fed into the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) database [21] (http://www.genenames.org/) to find corresponding HGNC ids. Unmatched, previous symbol and synonyms were removed.

2.2. Protein-protein Interaction Network

To exclude out false positive candidates, the genes/ proteins from different datasets were individually used to create human protein-protein interaction network (PPIN) with high confidence interactors (score≥0.7) using the STRING v10.0 database [22]. The data for interacting nodes were merged and duplicates were removed. Also, the nodes in the PPIN different from the input dataset were discarded.

2.3. Human-viral Interaction Network

The high confidence interactors obtained from STRING database for different datasets were overlapped using jvenn tool [23] to find oxidative stress and inflammation genes related to both aging and AD. Then, to identify the human-viral interacting genes in AD, the interactions of candidate genes/proteins with known viruses were mapped using the virhostnet v2.0 database [24] (http://virhostnet.prabi.fr/).

2.4. Drug-gene/protein Interactions

To identify plausible drug targets for the eight identified candidate genes, we used the Drug-Gene Interaction database (DGIdb) (http://dgidb.genome.wustl.edu/). It is comprised of data related to human drugs, ‘druggable genes’ and drug-gene interactions from 13 different sources and currently contains more than 14,144 drug-gene interactions involving 6,307 drugs and 2,611 human genes [25, 26].

2.5. Validation

To validate the probable role of virus pathogenesis in AD, we extracted top 20 AD GWAS genes [27] and created a PPIN that also included candidate genes identified in our analysis to ascertain whether they show any interaction with the GWAS genes. Further, AD GWAS genes were also mapped using VirHostNet v2.0 database to identify known viral interactors.

3. Results

3.1. Data Mining

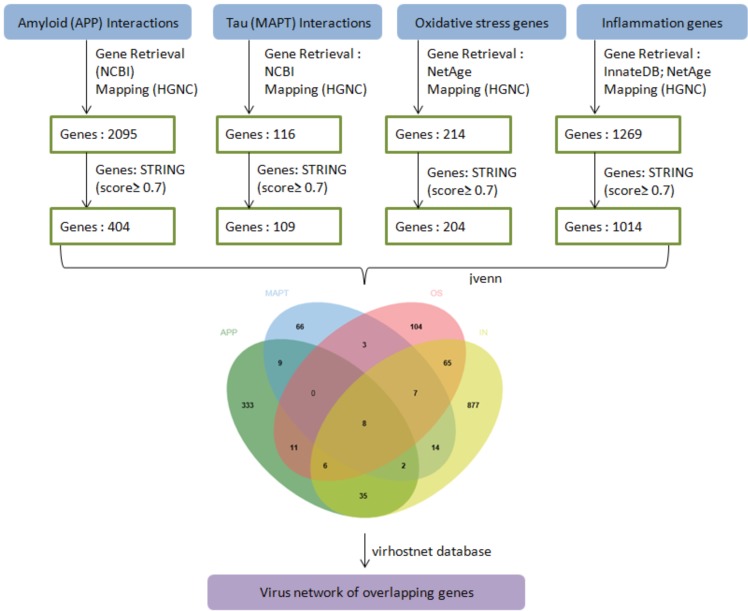

From NCBI database 2161 APP interacting genes were retrieved and after removing duplicates resulted in 2097 genes. Similarly, 153 MAPT interacting genes were retrieved and after removing duplicates resulted in 117 genes. 214 genes associated with oxidative stress were extracted from NetAge. 157 and 1205 genes associated with inflammation were extracted from NetAge and InnateDB databases respectively which after merging and duplicate removal remained 1269. 305 genes implicated in aging were retrieved from GenAge, 248 from GSE53890 and 244 from GSE46193 and removal of duplicates after merging resulted in 734 genes (Supplementary File 1 (1.3MB, zip) ). Finally, after HGNC mapping and sorting, data mining resulted in 2084 APP, 116 MAPT, 214 oxidative stress, 1195 inflammation and 729 genes associated with aging (Supplementary File 2 (1.3MB, zip) ). The overall workflow is depicted in Fig. (1).

Fig. (1).

The overall workflow representing steps of data retrieval, processing, overlap and PPI network. APP-APP interacting genes, MAPT-Tau interacting genes, OS-oxidative stress genes, IN-inflammatory genes. (The color version of the figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3.2. Protein-protein Interaction Network

PPIN analysis using the STRING database for different input candidate gene datasets resulted in five different networks. The nodes (and edges) for APP, MAPT, oxidative stress, inflammation and network were 744 (1094), 119 (562), 214 (1880), 1152 (13338) and 730 (5638) respectively. Applying scoring threshold (≥0.7) and filtering resulted in 404 APP, 109 MAPT, 204 oxidative stress, 1014 inflammation and 572 aging related high confidence genes/proteins. The overlap among these datasets yielded eight candidate genes (Supplementary File 3 (1.3MB, zip) ).

3.3. Human-viral AD Interaction Network

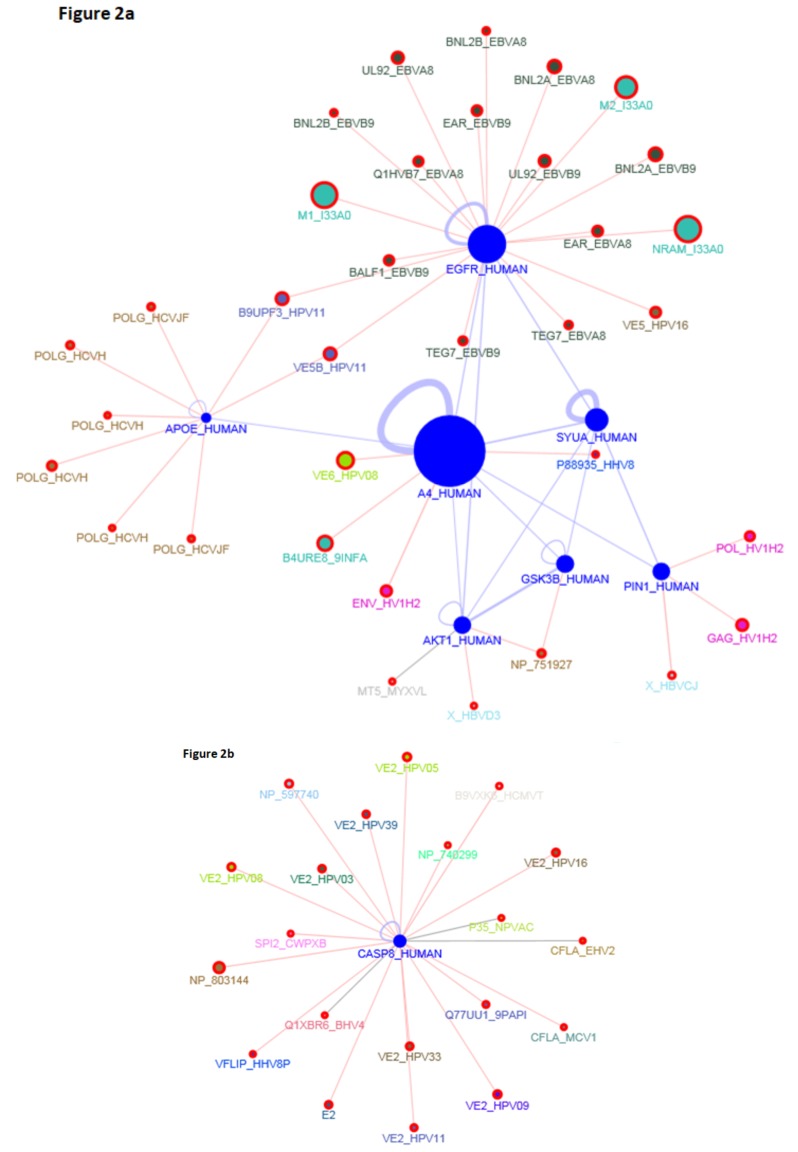

The overlap among all datasets yielded six common markers (AKT1, GSK3B, APP, APOE, EGFR, PIN1) whereas after excluding aging dataset the overlap resulted in two additional candidates (CASP8, SNCA) (Fig. 1). The virus interaction with overlapping six AD candidate genes showed involvement of mainly hepatitis C virus (HCV) with APOE, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) with EGFR, Human papillomavirus (HPV) with EGFR, APOE, APP, CASP8 and Human herpes virus (HHV) with APP and CASP8 proteins respectively. Different viral strains were specifically found to be present in the PPI network (Fig. 2a and 2b).

Fig. (2).

(a and b). PPI network among identified AD candidate genes and interacting viral strains. (The color version of the figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3.4. Drug-gene/protein Interactions

Based on the DGIdb results, 14 drugs interacted with gene AKT1 that encodes for AKT serine/threonine kinase 1, 20 drugs with GSK3B (Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta), 4 drugs with APP (Amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein), 2 drugs with APOE (Apolipoprotein E), 30 drugs with EGFR (Epidermal growth factor receptor), 1 drug with PIN1 (Peptidylprolyl cis/trans isomerase, NIMA-interacting 1), 3 drugs with CASP8 (caspase 8) (Supplementary File 4 (1.3MB, zip) ). Out of the 74 drugs, only 12 (2-AKT1, 3-GSK3B, 2-APOE, 5-EGFR) were found to possess anti-inflammatory property, antiviral activity along with a suggested role in AD therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Potential drug candidates with anti-inflammatory, antiviral activities along with role in Alzheimer’s disease therapy.

|

Candidate Genes/

Proteins |

Target Drug | Drug Class | FDA Approved | Mode of Action | Evidence of Anti-inflammatory Properties | Evidence of Antiviral Activity | Potential for AD Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKT1 (AKT serine/threonine kinase 1) | |||||||

| 1 | Risperidone | Antipsychotic | Yes | Has “loose” binding affinity for dopamine D2 receptors and 5-HT antagonist activity | √ [106] |

√ [107] |

√ [83] |

| 2 | Nelfinavir | Anti-retroviral | Yes | Human immunodeficiency virus-1 protease inhibitor | √ [108] |

√ [109, 110] |

√ [92, 108] |

| GSK3B (Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta) | |||||||

| 1 | Alsterpaullone | Experimental | No | CDK and GSK-3beta inhibitor | √ [111] |

√ [112] |

√ [84] |

| 2 | Indirubin-3'-monoxime | Experimental | No | GSK-3beta inhibitor | √ [113, 114] |

√ [115, 116] |

√ [86-88, 115] |

| 3 | Lithium | Bipolar disorder | Yes | Inhibition of GSK3, inositol phosphatases, or modulation of glutamate receptors | √ [117, 118] |

√ [119-121] |

√ [90, 91, 121, 122] |

| APOE (Apolipoprotein E) | |||||||

| 1 | Ritonavir | Antiviral | Yes | HIV protease inhibitor | √ [123] |

√ (FDA approved antiretroviral) |

√ [92] |

| 2 | Simvastatin | Lipid-lowering agent | Yes | Competitive inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase | √ [124, 125] |

√ [126-134] |

√ [93-95] |

| EGFR (Epidermal growth factor receptor) | |||||||

| 1 | Gefitinib | Anti-cancer | Yes | Inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinase | √ [135] |

√ [136-138] |

√ [139-141] |

| 2 | Erlotinib | Anti-cancer | Yes | Inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinase | √ [135] |

√ [137, 142-146] |

√ [141, 147] |

| 3 | Paclitaxel | Anti-cancer | Yes | Antimitotic drug/microtubule (MT)-stabilizing/EGFR inhibitor | √ [148] |

√ [149, 150] |

√ [96-98] |

| 4 | Sirolimus (Rapamycin) | Immunosuppressant and possesses both antifungal and antineoplastic properties. | Yes | Inhibits T lymphocyte activation and proliferation | √ [151, 152] |

√ [153] |

√ [99-102, 154] |

| 5 | Geldanamycin | Antitumor antibiotic (Anti-cancer) | Yes | Hsp90 inhibitor | √ [155-157] |

√ [158-165] |

√ [103-105] |

Interestingly, the same viruses were found to interact with AD GWAS genes providing support to our hypothesis.

3.5. Validation

Except APOE, no- other gene from eight identified candidate genes was found to be present in the AD GWAS dataset, but we observed strong interactions of these candidate genes with GWAS AD genes through PPIN.

4. Discussion

AD is the most common neurodegenerative disease which is reaching epidemic proportions due to the impact of population aging. Inflammation and oxidative stress play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD and the possible triggers for these may be mitochondrial dysfunction, increased metal levels, CNS infections, and β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides. Recently, association of infectious agents in complex human diseases not primarily suspected of infectious etiology has been increasingly reported. Further, viral infections have been shown to initiate peripheral local inflammatory response leading to neuronal and glial dysfunctions in the brain [28]. Recent advances in infectomics (high-throughput profiling of an infection), functional genomics and VirHostNet knowledge base has made it possible to identify host factors implicated in life cycle of viruses and virus-host protein-protein interactions [29].

The present study elucidated the molecular link among genes/proteins interacting with amyloid, tau, inflammation and oxidative stress with the potential involvement of viral pathogenesis and potential drug candidates. We used aging dataset and AD GWAS top 20 genes for validation purpose and overlap of genes/proteins interacting with amyloid beta precursor protein, microtubule associated protein tau, inflammation, oxidative stress and aging yielded six common markers (AKT1, GSK3B, APP, APOE, EGFR, PIN1) whereas excluding aging the overlap resulted in two additional candidates (CASP8, SNCA) (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Except APOE, none other gene was found in GWAS dataset, but we observed a strong interactions of these eight candidate genes with GWAS AD genes through PPIN and mapping with same group of viruses as observed with eight candidate genes (Supplementary Figs. F3 (1.3MB, zip) and F4 (1.3MB, zip) ). There exists substantial literature on the role of these eight genes with AD risk, pathology and all of these candidate genes were found to interact with the different viruses.

AKT1 gene encodes for AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 and is involved in Insulin signaling pathway. Intracellular Aβ inhibits Insulin receptor signaling in neurons by preventing AKT1 activation [30]. The rs2498786 promoter polymorphism in AKT1 was found to be associated with AD risk in a Chinese Han Population with and without Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) along with association of GG genotype with significantly higher AKT1 protein level [31]. AKT1 is shown to be involved in the tau phosphorylation at specific region (AT100 epitope) [32]. Rickle et al. 2006 reported that immunoprecipitated Akt induces phosphorylation of GSK-3 alpha/beta fusion protein resulting in significant increase in soluble fraction AKT activities in temporal cortex (direct correlation with neurofibrillary change staging of Braak). Further, in reactive astroglia and in pyramidal neurons undergoing degeneration associated with AD pathophysiology strong Ser Akt immunoreactivity was observed [33]. Cognitive impairment caused by Aβ42 in rats and mice is mediated by a pathway involving AKT1, GSK3β and CASP3 [34]. Interestingly, familial AD mutations of APPβ and presenilin (PSEN) can induce AKT1/GSK3β-mediated signalling leading to AD pathogenesis [35].

Three single-nucleotide polymorphisms in GSK3B - rs334558, rs1154597 and rs3107669 were found to be significantly associated with elevated T-tau levels, reduced Aβ42 levels and lower MMSE scores respectively [36]. A recent meta-analysis showed ethnicity specific correlation of GSK3B rs334558 T/C and rs6438552 C/T polymorphisms with AD risk [37]. An intronic polymorphism (IVS2-68G>A) was also found to be associated with higher risk for AD as well as fronto-temporal dementia [38]. Hernandez and colleagues have shown that overexpression of GSK3β enzyme in mice forebrain neurons can lead to tau hyper- phosphorylation, neuronal death, reactive astrocytosis, along with spatial learning deficit. Interestingly, they observed that lithium administration in earlier stage can prevent the progression of the tauopathy [39]. Inhibition of GSK3β activity has been investigated by several different groups worldwide as a potential therapeutic intervention for AD [40].

With the failure of anti-amyloid therapeutic strategies to translate into clinically useful therapies, it is suggested that APP and Aβ42 are not the only common players in the AD disease cascade. However, Amyloid hypothesis is still considered as a significant mechanism leading to AD pathophysiology. Apart from significant association of APP and PSEN mutations in familial AD, APOE4 has been the most consistent risk factor for late-onset AD to date [41]. A recent study reported differential transcriptional regulation of APP by different APOE isoforms [42]. Further, Aβ-induced neuroinflammation is mediated by APOE4 whereas inhibited by APOE2 via vitamin D receptor (VDR) signalling [43]. Cognitive and cerebrovascular dysfunction has been shown to be induced by the combined presence of Aβ42, APOE4 and peripheral inflammation [44].

CSF ApoE predicts progression of AD through its association with CSF Tau in non-demented APOE ε4 carriers [45]. In a meta-analysis study by our group, lower CSF ApoE levels were found to be associated with AD risk [46] In addition, APOE and EGFR were found to be candidate genes through genomic convergence and network analysis approach. Further, in a case-control study involving 267 patients with AD (PwAD) and 108 controls, we have identified a panel of biomarker comprising six parameters (Age, Education status, APOE ε4, EGFR levels, Iron levels, serum copper to zinc ratio) and created an AD risk score (ADRS) that can be used to differentiate AD cases from controls. In female mice, APOE4-induced cognitive and cerebrovascular deficits is prevented by the Epidermal growth factor (EGF) [47].

Pin1 belongs to the family of molecular chaperones [Peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerases (PPIases)] and are involved in the regulation of protein folding at proline residues [48]. Both GSK 3β and Pin1 are involved in linking amyloid β and Tau toxicities [48, 49]. In the brains of PwAD, Pin1 was found to be absent or downregulated which resulted in increased amyloidogenic APP processing and neurofibrillary degeneration [50, 51]. The similar findings were observed in Pin1 knockout mice with increase in the amyloidogenic APP processing along with change in the intracellular localization and regulation of APP conformation with lowering of Pin1 levels [50]. Further, significantly higher Pin1 mRNA level was found in the hippocampus of APOE4 mice than in APOE3 controls [52]. The level of neuroprotective Pin1 expression was reported to be significantly decreased in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells exposed to Aβ (25-35) [53]. Lower Pin1 decrease isomerisations of pThr231-Pro232 motif of Tau, inhibiting its dephosphorylation by PP2A phosphatase resulting in microtubules depolymerisation [54]. A PIN1 polymorphism rs2287839 with ‘CG’ genotype that prevents its repression by activating enhancer binding protein 4 (AP4) transcription factor is found to be protective for AD causing delayed onset in Chinese population as compared to ‘GG’ genotype [55].

Increased caspase-8 activation along with caspase-3 and caspase-9 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of PwAD has been reported [56]. Aβ 17-42 induced neuronal apoptosis is observed via a Fas-like/caspase-8 activation pathway in two human neuroblastoma cell lines, SH-SY5Y and IMR-32 [57]. CASP-8p18 immunolabeling of hippocamal neurons was demonstrated in all AD cases as compared to little staining in controls [58].

In Japanese subjects with AD, increased mRNA expression and low methylation of SNCA is reported [59]. Wang et al. showed that the ‘GG’ genotype of rs10516846 polymorphism in SNCA gene and increased α-synuclein levels in the CSF of ‘GG’ carriers is associated with increased early-onset AD risk in Chinese population [60]. The elevated α-synuclein levels induces cytotoxicity by decreasing B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-xL) protein and increasing BCL2-associated X (bax) protein expression, followed by release of cytochrome c, activation of caspase and also by inflammatory responses via the NFκB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathways [61].

The virus interaction with eight candidate genes showed involvement of mainly hepatitis C virus (HCV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), Human papillomavirus (HPV) and Human herpes virus (HHV-8). Association of HCV infection with AD has been reported consistently in recent years [62]. A 11 year population-based study in Taiwan conducted by Chiu and colleagues reported HCV infection as a significant risk factor for AD with multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of 1.36 (P<0.0001) for dementia in the HCV cohort. Further, HCV infection was found to be an independent AD risk factor with no interaction with other medical illnesses [63]. It has been suggested that HCV infects the brain monocytes/ macrophages through infected PBMC which cross the blood brain barrier and replicates in the brain endothelial cells and cause neuro-inflammation leading to white matter neuronal loss, perfusion and changes in association tracts. Higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, choline/creatine ratio, myo-inositol/creatine ratio, N-acetyl aspartate (NNA) and NNA-glutamate were found in the brain (basal ganglia) of HCV infected patients [64-68]. Cognitive dysfunction and neuropsychological symptoms were found to be present in the patients infected with HCV and also correlated with severity of the infection [69, 70]. Interestingly, Sutcliffe and colleagues have demonstrated liver as the site of origin of AD instead of brain [71].

McIntosh PB et al. 2008 conducted the structural analysis of the HPV type 16 E1^E4 protein revealing the existence of an amyloid form. Further, the author showed that the assembly into amyloid-like fibrils is facilitated by the N-terminal deletions and the fibrils bind to thioflavin T, which is commonly used to detect amyloid beta fibrils. The C-terminal region was found to be highly amyloidogenic, and its deletion prevented the accumulation and eliminated the amyloid staining [72]. In an interesting report, HPV-16 and HPV-18 coexisting infections were found in patients with autism and screening of these viruses is recommended in patients with AD [73].

Among all Human herpes viruses, interaction was found only with HHV 4 i.e. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), limited interaction of HHV8 with only APP and CASP-8 and CMV with only caspase-8. In a recent study by Shim et al., elevated plasma anti-EBV IgG antibodies were found in the follow-up of individuals from cognitively normal state to amnestic MCI (aMCI) state as compared to normal controls [74]. In addition, significant association of elevated plasma anti-EBV IgG levels with CDR scales and total CERAD scores was also observed in the Converter group. Interestingly, in another study, increased EBV IgG levels were reported in the patients with AD having IRF7 GG genotype [75]. These findings provide compelling evidence in support of the role of chronic EBV infection with cognitive decline in AD. HHV-8 virus has been associated with AIDS-dementia complex, primary CNS lymphoma and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) but till date no association has been shown with AD [76]. Similarly, existing literature does not substantiate association of CMV with AD.

Although some studies have highlighted the role of HSV1 and Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in the pathogenesis of AD, however, we did not find interaction of any candidate genes with HSV1 and VZV [77, 78]. The indirect interaction between AD risk genes and HSV genome via host transcription factors has been reported by Carter et al. [79]. Further, mechanism of HSV infection through soluble adapter-mediated virus bridging to the EGF receptor has also been reported in a recent study [80]. Additionally, molecular mechanism of HSV-1 in AD has been described by Harris et al. showing indirect involvement of mainly AD GWAS associated genes [81]. Further, a study by Hemling et al. has shown unlikely association between VZV and AD which reported VZV DNA in 26.5% of AD and in 27.5% of Controls [82].

Twelve drugs (Risperidone and Nelfinavir targeting AKT1; Alsterpaullone, Indirubin-3'-monoxime and Lithium targeting GSK3B; Ritonavir and Simvastatin targeting APOE; Gefitinib, Erlotinib, Paclitaxel, Sirolimus and Geldanamycin targeting EGFR) were identified as potential drug candidates with anti-inflammatory, antiviral activities and role in Alzheimer’s disease therapy (Table 1), of which, patent has already been granted or applied for the three drugs namely Nelfinavir (WO2006108666A1), Gefitinib (US9271987B2, US20130302337A1) and Erlotinib (US9271987B2) for AD therapy.

AKT1 (AKT serine/threonine kinase 1): Risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic, has resulted in improved concentration and cognition in patients with schizophrenia. In a recent study, risperidone significantly reversed the Aβ42 induced dysfunction in memory, learning, exploratory behavior and locomotor activity. Also, risperidone decreased the levels of Aβ42, BACE1 and hyperphosphorylated tau in the hippocampus and cortex of mice model of AD as detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay. In cultured cortical neurons, risperidone also reversed the Aβ42-induced loss of cell viability and mitochondrial membrane potential. The p-Akt expression was found to be increased, whereas GSK3β and Caspase-3 expression were found to be decreased [83].

GSK3B (Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta): Alsterpaullone, the most active paullone, inhibits in vivo tau phosphorylation at sites which are specifically phosphorylated by GSK-3β [84]. Indirubin-3'-monoxime has been shown to reduce Aβ25-35-induced apoptosis by inhibiting hyperphosphorylation of tau via a GSK3β-mediated mechanism in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells [85, 86]. It confers neuro-protection against cognitive impairment induced by high fat diet in mice probably by increasing Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) based synaptic plasticity [87]. Further, Indirubin-3'-monoxime also attenuates Aβ-associated neuropathology and rescues spatial memory deficits in an AD mouse model [88].

Lithium and memantine (NMDA receptor antagonist) alone and in combination can improve spatial memory decline and inflammation induced by Aβ42 oligomers in rats [89]. A meta-analysis comprising 3 clinical trials comprising 232 subjects showed that lithium significantly reduced cognitive impairment as compared to placebo [90]. Lithium exhibit neuro-protective effects via inhibition of GSK-3 and inositol-145 triphosphate [91].

APOE (Apolipoprotein E): Although ritonavir strongly decreases the activity of BACE1, lopinavir/ritonavir shows no effect on Aβ deposition in the mouse (APP SCID) brain, probably due to poor in vivo CNS penetration [92]. Re-analysis of data from failed AD clinical trials suggested that the use of simvastatin may delay the cognitive dysfunction predominantly in patients with ApoE4 homozygotes. Long-term use of statins has been associated with better cognitive performance. In a 10-year follow-up study, APOE4/APOE4-genotyped AD patients on statin therapy exhibited better cognitive function [93]. Simvastatin confer neuroprotection against cognitive impairment in AD possibly by upregulation of Klotho, an anti-aging protein that attenuates oxidative stress by the induction of enzyme manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) [94]. Simvastatin and atorvastatin have been shown to facilitate extracellular degradation of Aβ by increasing secretion of neprilysin from astrocytes via activation of MAPK/Erk1/2 signalling pathways [95].

EGFR (Epidermal growth factor receptor): Paclitaxel is found to rescue synaptic pathologies induced by tau through adequate presynaptic vesicle store maintenance [96, 97]. Paclitaxel (Taxol) provides neuro-protection against Aβ toxicity in primary neurons [98]. Rapamycin, mTOR Inhibitor, is found to decrease the loss of synapse, reactive gliosis and neurodegeneration of perforant pathway in AD-tauopathy mouse model [99]. Also, it provides protection by increasing presynaptic activity in rat hippocampal primary neurons against Aβ-induced synaptotoxicity [100]. Further, chronic rapamycin use is shown to preserve brain vascular density, restore integrity and function through NO synthase activation in AD mouse brains [101]. Another mTOR inhibitor drug, temsirolimus, has also been shown to facilitate autophagic Aβ clearance in the brain of APP/PS1 mice and HEK293-APP695 cells and exerts neuroprotective effects by attenuating neurodegeneration in APP/PS1 mice hippocampus [102]. The induction of heat shock proteins (Hsps) confer neuro-protection in different complex neurological diseases including AD, stroke, and Huntington's disease and can be used as a possible therapeutic intervention [103]. The Hsp90 inhibitor, geldanamycin derived from Streptomyces has been found to inhibit tau aggregation [104]. It shows protection against Aβ42 induced hippocampal apoptosis and memory impairment partly by upregulation of Hsp70 and P70S6K [105].

The present study has some inherent limitations. We might have missed some associations due to the availability of scarce literature related to human PPI and validated viral-human protein interactions because of insufficient viral screening studies in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. In the present study, the search was performed with all AD candidates against all viruses together to identify a common network instead of one AD gene/protein against virus database which would have resulted in multiple networks. The probable reason for our findings could be the lack of evidence for direct interaction among certain human genes and viral genes/proteins. Additionally, the mode of infective pathological process in AD through oxidative stress and inflammation mediated by viruses is mostly unclear. We believe future in-depth studies should explore direct physical interaction of viral and human proteins along with elucidating the pathological pathways of viral infections involved in AD pathogenesis.

Conclusion

Among several environmental etiological causes, viral infections could also be a potential risk factor for AD susceptibility. It is becoming increasingly apparent that the effect of exposure to infectious agents varies greatly depending upon the genetic makeup of the host. Virtually all of the genetic markers found to be associated with AD to date are ‘risk factors’ rather than ‘causative genes’ since many individuals who have the genetic marker do not have evidence of disease. The correct infectious diagnosis and validation of predisposing or disease modulating genes in blood of these patients would be crucial in elucidating therapeutic approaches in the prodromal phase of disease and may decrease the incidence of neurodegenerative disorders or increase the therapeutic window for neuro-protection. For complex multifactorial diseases, multi-target drugs or combination therapies might be more effective.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Director, Dr. Sanjay Kumar, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research - Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (CSIR-IGIB) for their motivation and unconditional support. Financial support from ICMR (GAP0136) is duly acknowledged. PT acknowledges CSIR, Govt. of India for providing fellowship (CSIR-RA). We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions for improving the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available on the publisher’s web site along with the published article.

Author’s contribution

PT performed literature mining and data interpretation, conceptualized and wrote the manuscript. RG, SK, RA, LS and SK have contributed by helping in improving the manuscript. RK has conceived, interpreted, wrote and supervised the study. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

References

- 1.Bertram L., Tanzi R.E. The genetic epidemiology of neurodegenerative disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115(6):1449–1457. doi: 10.1172/JCI24761. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/JCI24761]. [PMID: 15931380]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffin W.S. Inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;83(2):470S–474S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.470S. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.2.470S]. [PMID: 16470015]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talwar P., Sinha J., Grover S., Rawat C., Kushwaha S., Agarwal R., Taneja V., Kukreti R. dissecting complex and multifactorial nature of alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: A clinical, genomic, and systems biology perspective. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9390-0. [PMID: 26351077]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolson G.L., Nicolson J.H.G.L., Haier J. Role of chronic bacterial a role of chronic bacterial and viral infections in neurodegenerative, nd viral infections in neurodegenerative, neurobehavioral, psychiatric, autoimmune and fatiguing illnesses: Part 1 neurobehavioral, psychiatric, autoimmune and fatiguing illnesses: Part. Br. J. Med. Pract. 2009;2(4) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukumoto H., Tennis M., Locascio J.J., Hyman B.T., Growdon J.H., Irizarry M.C. Age but not diagnosis is the main predictor of plasma amyloid beta-protein levels. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60(7):958–964. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.7.958. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneur.60.7.958]. [PMID: 12873852]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groh N., Bühler A., Huang C., Li K.W., van Nierop P., Smit A.B., Fändrich M., Baumann F., David D.C. Age-dependent protein aggregation initiates amyloid-β aggregation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:138. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00138. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00138]. [PMID: 28567012]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bretsky P., Guralnik J.M., Launer L., Albert M., Seeman T.E. The role of APOE-epsilon4 in longitudinal cognitive decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Neurology. 2003;60(7):1077–1081. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055875.26908.24. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000055875.26908.24]. [PMID: 12682309]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamis D., Meagher D., Williams J., Mulligan O., McCarthy G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between the apolipoprotein E genotype and delirium. Psychiatr. Genet. 2016;26(2):53–59. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000122. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/YPG.0000000000000122]. [PMID: 26901792]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertram L., McQueen M.B., Mullin K., Blacker D., Tanzi R.E. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat. Genet. 2007;39(1):17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng1934]. [PMID: 17192785]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter C.J. Convergence of genes implicated in Alzheimer’s disease on the cerebral cholesterol shuttle: APP, cholesterol, lipoproteins, and atherosclerosis. Neurochem. Int. 2007;50(1):12–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.07.007. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2006.07.007]. [PMID: 16973241]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatz M., Fratiglioni L., Johansson B., Berg S., Mortimer J.A., Reynolds C.A., Fiske A., Pedersen N.L. Complete ascertainment of dementia in the Swedish Twin Registry: the HARMONY study. Neurobiol. Aging. 2005;26(4):439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.04.004. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.04.004]. [PMID: 15653172]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolson G.L., Haier J. Role of chronic bacterial and viral infections in neurodegenerative, neurobehavioural, psychiatric, autoimmune and fatiguing illnesses: Part 2. Br. J. Med. Pract. 2010;3(1):301–310. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foxman E.F., Iwasaki A. Genome-virome interactions: examining the role of common viral infections in complex disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9(4):254–264. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2541. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2541]. [PMID: 21407242]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorber B. Are all diseases infectious? Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;125(10):844–851. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00010. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00010]. [PMID: 8928993]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattson M.P. Infectious agents and age-related neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Res. Rev. 2004;3(1):105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2003.08.005. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2003.08.005]. [PMID: 15163105]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin W.R., Wozniak M.A., Cooper R.J., Wilcock G.K., Itzhaki R.F. Herpesviruses in brain and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pathol. 2002;197(3):395–402. doi: 10.1002/path.1127. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/path.1127]. [PMID: 12115887]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verreault R., Laurin D., Lindsay J., De Serres G. Past exposure to vaccines and subsequent risk of Alzheimer's disease. 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Tacutu R., Budovsky A., Fraifeld V.E. The NetAge database: a compendium of networks for longevity, age-related diseases and associated processes. Biogerontology. 2010;11(4):513–522. doi: 10.1007/s10522-010-9265-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10522-010-9265-8]. [PMID: 20186480]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breuer K., Foroushani A.K., Laird M.R., Chen C., Sribnaia A., Lo R., Winsor G.L., Hancock R.E., Brinkman F.S., Lynn D.J. InnateDB: systems biology of innate immunity and beyond--recent updates and continuing curation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D1228–D1233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1147. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1147]. [PMID: 23180781]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrett T., Troup D.B., Wilhite S.E., Ledoux P., Rudnev D., Evangelista C., Kim I.F., Soboleva A., Tomashevsky M., Marshall K.A., Phillippy K.H., Sherman P.M., Muertter R.N., Edgar R. NCBI GEO: archive for high-throughput functional genomic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D885–D890. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn764. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkn764]. [PMID: 18940857]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray K.A., Yates B., Seal R.L., Wright M.W., Bruford E.A. Genenames.org: the HGNC resources in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D1079–D1085. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1071. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1071]. [PMID: 25361968]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szklarczyk D., Morris J.H., Cook H., Kuhn M., Wyder S., Simonovic M., Santos A., Doncheva N.T., Roth A., Bork P., Jensen L.J., von Mering C. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D362–D368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw937]. [PMID: 27924014]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bardou P., Mariette J., Escudié F., Djemiel C., Klopp C. jvenn: an interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(1):293. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-293. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-293]. [PMID: 25176396]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guirimand T., Delmotte S., Navratil V. VirHostNet 2.0: surfing on the web of virus/host molecular interactions data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D583–D587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1121. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1121]. [PMID: 25392406]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner A.H., Coffman A.C., Ainscough B.J., Spies N.C., Skidmore Z.L., Campbell K.M., Krysiak K., Pan D., McMichael J.F., Eldred J.M., Walker J.R., Wilson R.K., Mardis E.R., Griffith M., Griffith O.L. DGIdb 2.0: mining clinically relevant drug-gene interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D1036–D1044. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1165. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1165]. [PMID: 26531824]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith M., Griffith O.L., Coffman A.C., Weible J.V., McMichael J.F., Spies N.C., Koval J., Das I., Callaway M.B., Eldred J.M., Miller C.A., Subramanian J., Govindan R., Kumar R.D., Bose R., Ding L., Walker J.R., Larson D.E., Dooling D.J., Smith S.M., Ley T.J., Mardis E.R., Wilson R.K. DGIdb: mining the druggable genome. Nat. Methods. 2013;10(12):1209–1210. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2689. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2689]. [PMID: 24122041]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Cauwenberghe C., Van Broeckhoven C., Sleegers K. The genetic landscape of Alzheimer disease: clinical implications and perspectives. Genet. Med. 2016;18(5):421–430. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.117. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.117]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deleidi M., Isacson O. Viral and inflammatory triggers of neurodegenerative diseases. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4(121):121ps3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003492. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003492]. [PMID: 22344685]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navratil V., de Chassey B., Combe C.R., Lotteau V. When the human viral infectome and diseasome networks collide: towards a systems biology platform for the aetiology of human diseases. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-13. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1752-0509-5-13]. [PMID: 21255393]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao F.F., Xu H. Insulin signaling in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Signal. 2009;2(74):pe36. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.274pe36. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.274pe36]. [PMID: 19509405]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu S.Y., Zhao H.D., Wang J.L., Huang T., Tian H.W., Yao L.F., Tao H., Chen Z.W., Wang C.Y., Sheng S.T., Li H., Zhao B., Li K.S. Association between polymorphisms of the AKT1 gene promoter and risk of the Alzheimer’s disease in a chinese han population with type 2 diabetes. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2015;21(8):619–625. doi: 10.1111/cns.12430. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cns.12430]. [PMID: 26178916]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ksiezak-Reding H., Pyo H.K., Feinstein B., Pasinetti G.M. Akt/PKB kinase phosphorylates separately Thr212 and Ser214 of tau protein in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1639(3):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.09.001. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.09.001]. [PMID: 14636947]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rickle A., Bogdanovic N., Volkman I., Winblad B., Ravid R., Cowburn R.F. Akt activity in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Neuroreport. 2004;15(6):955–959. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200404290-00005. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001756-200404290-00005]. [PMID: 15076714]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jo J., Whitcomb D.J., Olsen K.M., Kerrigan T.L., Lo S.C., Bru-Mercier G., Dickinson B., Scullion S., Sheng M., Collingridge G., Cho K. Aβ(1-42) inhibition of LTP is mediated by a signaling pathway involving caspase-3, Akt1 and GSK-3β. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14(5):545–547. doi: 10.1038/nn.2785. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nn.2785]. [PMID: 21441921]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryder J., Su Y., Ni B. Akt/GSK3beta serine/threonine kinases: evidence for a signalling pathway mediated by familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations. Cell. Signal. 2004;16(2):187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.07.004. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.07.004]. [PMID: 14636889]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kettunen P., Larsson S., Holmgren S., Olsson S., Minthon L., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., Nilsson S., Sjölander A. Genetic variants of GSK3B are associated with biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive function. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44(4):1313–1322. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142025. [PMID: 25420549]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Q., Cao Y.P., Gao J. Common polymorphisms in the GSK3β gene may contribute to the pathogenesis of alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2015;28(2):83–93. doi: 10.1177/0891988714554712. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0891988714554712]. [PMID: 25351705]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaffer B.A., Bertram L., Miller B.L., Mullin K., Weintraub S., Johnson N., Bigio E.H., Mesulam M., Wiedau-Pazos M., Jackson G.R., Cummings J.L., Cantor R.M., Levey A.I., Tanzi R.E., Geschwind D.H. Association of GSK3B with Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65(10):1368–1374. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.10.1368. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneur.65.10.1368]. [PMID: 18852354]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez F., Lucas J.J., Avila J. GSK3 and tau: two convergence points in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(Suppl. 1):S141–S144. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129025. [PMID: 22710914]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma T. GSK3 in Alzheimer’s disease: mind the isoforms. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;39(4):707–710. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131661. [PMID: 24254703]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J., Zhang Q., Chen F., Meng X., Liu W., Chen D., Yan J., Kim S., Wang L., Feng W., Saykin A.J., Liang H., Shen L. Genome-wide association and interaction studies of CSF Ttau/ Abeta42 ratio in ADNI cohort. . Neurobiol Aging, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Lee L.C., Goh M.Q.L., Koo E.H. Transcriptional regulation of APP by apoE: To boldly go where no isoform has gone before: ApoE, APP transcription and AD: Hypothesised mechanisms and existing knowledge gaps. BioEssays. 2017;39(9) doi: 10.1002/bies.201700062. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bies.201700062]. [PMID: 28731260]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorey E., Bamji-Mirza M., Najem D., Li Y., Liu H., Callaghan D., Walker D., Lue L.F., Stanimirovic D., Zhang W., Apolipoprotein E. Apolipoprotein E isoforms differentially regulate alzheimer’s disease and amyloid-β-induced inflammatory response in vivo and in vitro. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(4):1265–1279. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160133. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160133]. [PMID: 28372324]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marottoli F.M., Katsumata Y., Koster K.P., Thomas R., Fardo D.W., Tai L.M. Peripheral inflammation, apolipoprotein E4, and amyloid-β interact to induce cognitive and cerebrovascular dysfunction. ASN Neuro. 2017;9(4):1759091417719201. doi: 10.1177/1759091417719201. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1759091417719201]. [PMID: 28707482]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Harten A.C., Jongbloed W., Teunissen C.E., Scheltens P., Veerhuis R., van der Flier W.M. CSF ApoE predicts clinical progression in nondemented APOEε4 carriers. Neurobiol. Aging. 2017;57:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.04.002. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.04.002]. [PMID: 28571653]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talwar P., Sinha J., Grover S., Agarwal R., Kushwaha S., Srivastava M.V., Kukreti R. Meta-analysis of apolipoprotein E levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016;360:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.12.004. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2015.12.004]. [PMID: 26723997]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas R., Morris A.W.J., Tai L.M. Epidermal growth factor prevents APOE4-induced cognitive and cerebrovascular deficits in female mice. Heliyon. 2017;3(6):e00319. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00319. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00319]. [PMID: 28626809]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blair L.J., Baker J.D., Sabbagh J.J., Dickey C.A. The emerging role of peptidyl-prolyl isomerase chaperones in tau oligomerization, amyloid processing, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2015;133(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13033. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13033]. [PMID: 25628064]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lloret A., Fuchsberger T., Giraldo E., Viña J. Molecular mechanisms linking amyloid β toxicity and Tau hyperphosphorylation in Alzheimer׳s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;83:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.02.028. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.02.028]. [PMID: 25746773]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pastorino L., Ma S.L., Balastik M., Huang P., Pandya D., Nicholson L., Lu K.P. Alzheimer’s disease-related loss of Pin1 function influences the intracellular localization and the processing of AβPP. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30(2):277–297. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111259. [PMID: 22430533]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Driver J.A., Zhou X.Z., Lu K.P. Regulation of protein conformation by Pin1 offers novel disease mechanisms and therapeutic approaches in Alzheimer’s disease. Discov. Med. 2014;17(92):93–99. [PMID: 24534472]. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lattanzio F., Carboni L., Carretta D., Rimondini R., Candeletti S., Romualdi P. Human apolipoprotein E4 modulates the expression of Pin1, Sirtuin 1, and Presenilin 1 in brain regions of targeted replacement apoE mice. Neuroscience. 2014;256:360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.017. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.017]. [PMID: 24161275]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lattanzio F., Carboni L., Carretta D., Candeletti S., Romualdi P. Treatment with the neurotoxic Abeta (25-35) peptide modulates the expression of neuroprotective factors Pin1, Sirtuin 1, and brain derived neurotrophic factor in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2016;68(5):271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lonati E., Masserini M., Bulbarelli A. Pin1: a new outlook in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2011;8(6):615–622. doi: 10.2174/156720511796717140. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/156720511796717140]. [PMID: 21605045]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma S.L., Tang N.L., Tam C.W., Lui V.W., Lam L.C., Chiu H.F., Driver J.A., Pastorino L., Lu K.P.A.A. PIN1 polymorphism that prevents its suppression by AP4 associates with delayed onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012;33(4):804–813. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.018. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.018]. [PMID: 20580132]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tacconi S., Perri R., Balestrieri E., Grelli S., Bernardini S., Annichiarico R., Mastino A., Caltagirone C., Macchi B. Increased caspase activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2004;190(1):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.07.009. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.07.009]. [PMID: 15473998]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wei W., Norton D.D., Wang X., Kusiak J.W. Abeta 17-42 in Alzheimer’s disease activates JNK and caspase-8 leading to neuronal apoptosis. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 9):2036–2043. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf205. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awf205]. [PMID: 12183349]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rohn T.T., Head E., Nesse W.H., Cotman C.W., Cribbs D.H. Activation of caspase-8 in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 2001;8(6):1006–1016. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0449. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/nbdi.2001.0449]. [PMID: 11741396]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshino Y., Mori T., Yoshida T., Yamazaki K., Ozaki Y., Sao T., Funahashi Y., Iga J.I., Ueno S.I. Elevated mRNA expression and low methylation of SNCA in japanese alzheimer’s disease subjects. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(4):1349–1357. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160430. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160430]. [PMID: 27567856]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Q., Tian Q., Song X., Liu Y., Li W. SNCA gene polymorphism may contribute to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2016;30(6):1092–1099. doi: 10.1002/jcla.21986. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcla.21986]. [PMID: 27184464]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seo J.H., Rah J.C., Choi S.H., Shin J.K., Min K., Kim H.S., Park C.H., Kim S., Kim E.M., Lee S.H., Lee S., Suh S.W., Suh Y.H. Alpha-synuclein regulates neuronal survival via Bcl-2 family expression and PI3/Akt kinase pathway. FASEB J. 2002;16(13):1826–1828. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0041fje. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1096/fj.02-0041fje]. [PMID: 12223445]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sochocka M., Zwolińska K., Leszek J. The infectious etiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(7):996–1009. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666170313122937. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1570159X15666170313122937]. [PMID: 28294067]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chiu W.C., Tsan Y.T., Tsai S.L., Chang C.J., Wang J.D., Chen P.C. Hepatitis C viral infection and the risk of dementia. Eur. J. Neurol. 2014;21(8):1068–e59. doi: 10.1111/ene.12317. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ene.12317]. [PMID: 24313931]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Solinas A., Piras M.R., Deplano A. Cognitive dysfunction and hepatitis C virus infection. World J. Hepatol. 2015;7(7):922–925. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i7.922. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i7.922]. [PMID: 25954475]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilkinson J., Radkowski M., Eschbacher J.M., Laskus T. Activation of brain macrophages/microglia cells in hepatitis C infection. Gut. 2010;59(10):1394–1400. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.199356. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.2009.199356]. [PMID: 20675697]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu Z., Zhao F., He J.J. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) interaction with astrocytes: nonproductive infection and induction of IL-18. J. Neurovirol. 2014;20(3):278–293. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0245-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13365-014-0245-7]. [PMID: 24671718]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Forton D.M., Allsop J.M., Main J., Foster G.R., Thomas H.C., Taylor-Robinson S.D. Evidence for a cerebral effect of the hepatitis C virus. Lancet. 2001;358(9275):38–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05270-3. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05270-3]. [PMID: 11454379]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Forton D.M., Hamilton G., Allsop J.M., Grover V.P., Wesnes K., O’Sullivan C., Thomas H.C., Taylor-Robinson S.D. Cerebral immune activation in chronic hepatitis C infection: a magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J. Hepatol. 2008;49(3):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.03.022. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2008.03.022]. [PMID: 18538439]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karim S., Mirza Z., Kamal M.A., Abuzenadah A.M., Azhar E.I., Al-Qahtani M.H., Sohrab S.S. An association of virus infection with type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2014;13(3):429–439. doi: 10.2174/18715273113126660164. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/18715273113126660164]. [PMID: 24059298]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hilsabeck R.C., Hassanein T.I., Carlson M.D., Ziegler E.A., Perry W. Cognitive functioning and psychiatric symptomatology in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2003;9(6):847–854. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703960048. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1355617703960048]. [PMID: 14632243]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sutcliffe J.G., Hedlund P.B., Thomas E.A., Bloom F.E., Hilbush B.S. Peripheral reduction of β-amyloid is sufficient to reduce brain β-amyloid: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2011;89(6):808–814. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22603. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jnr.22603]. [PMID: 21374699]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McIntosh P.B., Martin S.R., Jackson D.J., Khan J., Isaacson E.R., Calder L., Raj K., Griffin H.M., Wang Q., Laskey P., Eccleston J.F., Doorbar J. Structural analysis reveals an amyloid form of the human papillomavirus type 16 E1--E4 protein and provides a molecular basis for its accumulation. J. Virol. 2008;82(16):8196–8203. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00509-08. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00509-08]. [PMID: 18562538]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Omura Y., Lu D., Jones M.K., Nihrane A., Duvvi H., Shimotsuura Y., Ohki M. Early detection of autism (ASD) by a non-invasive quick measurement of markedly reduced acetylcholine & DHEA and increased β-amyloid (1-42), asbestos (Chrysotile), titanium dioxide, Al, Hg & often coexisting virus infections (CMV, HPV 16 and 18), bacterial infections etc. in the brain and corresponding safe individualized effective treatment. Acupunct. Electrother. Res. 2015;40(3):157–187. doi: 10.3727/036012915x14473562232941. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3727/036012915X14473562232941]. [PMID: 26829843]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shim S.M., Cheon H.S., Jo C., Koh Y.H., Song J., Jeon J.P. Elevated epstein-barr virus antibody level is associated with cognitive decline in the korean elderly. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(1):293–301. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160563. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160563]. [PMID: 27589534]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Licastro F., Raschi E., Carbone I., Porcellini E. Variants in antiviral genes are risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46(3):655–663. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142718. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-142718]. [PMID: 25835418]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Volpi A. Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus type 8 infections of the central nervous system. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl. 2):120A–127A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Itzhaki R.F. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer’s disease: possible mechanisms and signposts. FASEB J. 2017;31(8):3216–3226. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700360. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1096/fj.201700360]. [PMID: 28765170]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Steel A.J., Eslick G.D. Herpes viruses increase the risk of alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47(2):351–364. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140822. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-140822]. [PMID: 26401558]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carter C.J. Alzheimer’s disease: a pathogenetic autoimmune disorder caused by herpes simplex in a gene-dependent manner. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010;2010:140539. doi: 10.4061/2010/140539. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2010/140539]. [PMID: 21234306]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakano K., Kobayashi M., Nakamura K., Nakanishi T., Asano R., Kumagai I., Tahara H., Kuwano M., Cohen J.B., Glorioso J.C. Mechanism of HSV infection through soluble adapter-mediated virus bridging to the EGF receptor. Virology. 2011;413(1):12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.02.014. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2011.02.014]. [PMID: 21382632]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harris S.A., Harris E.A. Molecular Mechanisms for Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:48. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00048. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00048]. [PMID: 29559905]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hemling N., Röyttä M., Rinne J., Pöllänen P., Broberg E., Tapio V., Vahlberg T., Hukkanen V. Herpesviruses in brains in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54(2):267–271. doi: 10.1002/ana.10662. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ana.10662]. [PMID: 12891684]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu L., Feng X., Li T., Sun B., Khan M.Z., He L. Risperidone ameliorated Abeta1-42-induced cognitive and hippocampal synaptic impairments in mice. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Leost M., Schultz C., Link A., Wu Y.Z., Biernat J., Mandelkow E.M., Bibb J.A., Snyder G.L., Greengard P., Zaharevitz D.W., Gussio R., Senderowicz A.M., Sausville E.A., Kunick C., Meijer L. Paullones are potent inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and cyclin-dependent kinase 5/p25. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267(19):5983–5994. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01673.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01673.x]. [PMID: 10998059]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang S.G., Wang X.S., Zhang Y.D., Di Q., Shi J.P., Qian M., Xu L.G., Lin X.J., Lu J. Indirubin-3′-monoxime suppresses amyloid-beta-induced apoptosis by inhibiting tau hyperphosphorylation. Neural Regen. Res. 2016;11(6):988–993. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.184500. [PMID: 27482230]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang S., Zhang Y., Xu L., Lin X., Lu J., Di Q., Shi J., Xu J. Indirubin-3′-monoxime inhibits beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;450(2):142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.030. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.030]. [PMID: 19027827]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sharma S., Taliyan R. Neuroprotective role of Indirubin-3′-monoxime, a GSKβ inhibitor in high fat diet induced cognitive impairment in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;452(4):1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.034. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.034]. [PMID: 25234596]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ding Y., Qiao A., Fan G.H. Indirubin-3′-monoxime rescues spatial memory deficits and attenuates beta-amyloid-associated neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;39(2):156–168. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.022. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.022]. [PMID: 20381617]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Budni J., Feijó D.P., Batista-Silva H., Garcez M.L., Mina F., Belletini-Santos T., Krasilchik L.R., Luz A.P., Schiavo G.L., Quevedo J. Lithium and memantine improve spatial memory impairment and neuroinflammation induced by β-amyloid 1-42 oligomers in rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2017;141:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2017.03.017. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2017.03.017]. [PMID: 28359852]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Matsunaga S., Kishi T., Annas P., Basun H., Hampel H., Iwata N. Lithium as a treatment for alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(2):403–410. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150437. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150437]. [PMID: 26402004]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morris G., Berk M. The putative use of lithium in alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016;13(8):853–861. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160219113112. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1567205013666160219113112]. [PMID: 26892287]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lan X., Kiyota T., Hanamsagar R., Huang Y., Andrews S., Peng H., Zheng J.C., Swindells S., Carlson G.A., Ikezu T. The effect of HIV protease inhibitors on amyloid-beta peptide degradation and synthesis in human cells and Alzheimer’s disease animal model. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7(2):412–423. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9304-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Geifman N., Brinton R.D., Kennedy R.E., Schneider L.S., Butte A.J. Evidence for benefit of statins to modify cognitive decline and risk in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2017;9(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0237-y. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13195-017-0237-y]. [PMID: 28212683]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Adeli S., Zahmatkesh M., Tavoosidana G., Karimian M., Hassanzadeh G. Simvastatin enhances the hippocampal klotho in a rat model of streptozotocin-induced cognitive decline. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;72:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.09.009. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.09.009]. [PMID: 27687042]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yamamoto N., Fujii Y., Kasahara R., Tanida M., Ohora K., Ono Y., Suzuki K., Sobue K. Simvastatin and atorvastatin facilitates amyloid β-protein degradation in extracellular spaces by increasing neprilysin secretion from astrocytes through activation of MAPK/Erk1/2 pathways. Glia. 2016;64(6):952–962. doi: 10.1002/glia.22974. [PMID: 26875818]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Erez H., Shemesh O.A., Spira M.E. Rescue of tau-induced synaptic transmission pathology by paclitaxel. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014;8:34. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00034. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2014.00034]. [PMID: 24574970]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shemesh O.A., Spira M.E. Rescue of neurons from undergoing hallmark tau-induced Alzheimer’s disease cell pathologies by the antimitotic drug paclitaxel. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;43(1):163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.03.008. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2011.03.008]. [PMID: 21406229]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Michaelis M.L., Ranciat N., Chen Y., Bechtel M., Ragan R., Hepperle M., Liu Y., Georg G. Protection against beta-amyloid toxicity in primary neurons by paclitaxel (Taxol). J. Neurochem. 1998;70(4):1623–1627. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041623.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041623.x]. [PMID: 9523579]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Siman R., Cocca R., Dong Y. The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin mitigates perforant pathway neurodegeneration and synapse loss in a mouse model of early-stage alzheimer-type tauopathy. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142340. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142340]. [PMID: 26540269]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ramírez A.E., Pacheco C.R., Aguayo L.G., Opazo C.M. Rapamycin protects against Aβ-induced synaptotoxicity by increasing presynaptic activity in hippocampal neurons. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842(9):1495–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.04.019. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.04.019]. [PMID: 24794719]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lin A.L., Zheng W., Halloran J.J., Burbank R.R., Hussong S.A., Hart M.J., Javors M., Shih Y.Y., Muir E., Solano Fonseca R., Strong R., Richardson A.G., Lechleiter J.D., Fox P.T., Galvan V. Chronic rapamycin restores brain vascular integrity and function through NO synthase activation and improves memory in symptomatic mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(9):1412–1421. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.82. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2013.82]. [PMID: 23801246]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jiang T., Yu J.T., Zhu X.C., Tan M.S., Wang H.F., Cao L., Zhang Q.Q., Shi J.Q., Gao L., Qin H., Zhang Y.D., Tan L. Temsirolimus promotes autophagic clearance of amyloid-β and provides protective effects in cellular and animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2014;81:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.02.008. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2014.02.008]. [PMID: 24602800]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Klettner A. The induction of heat shock proteins as a potential strategy to treat neurodegenerative disorders. Drug News Perspect. 2004;17(5):299–306. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2004.17.5.829033. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1358/dnp.2004.17.5.829033]. [PMID: 15334179]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Calcul L., Zhang B., Jinwal U.K., Dickey C.A., Baker B.J. Natural products as a rich source of tau-targeting drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. Future Med. Chem. 2012;4(13):1751–1761. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.124. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4155/fmc.12.124]. [PMID: 22924511]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zare N., Motamedi F., Digaleh H., Khodagholi F., Maghsoudi N. Collaboration of geldanamycin-activated P70S6K and Hsp70 against beta-amyloid-induced hippocampal apoptosis: an approach to long-term memory and learning. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2015;20(2):309–319. doi: 10.1007/s12192-014-0550-3. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12192-014-0550-3]. [PMID: 25576151]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Obuchowicz E., Bielecka-Wajdman A.M., Paul-Samojedny M., Nowacka M. Different influence of antipsychotics on the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines depends on glia activation: An in vitro study. Cytokine. 2017;94:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.04.004. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2017.04.004]. [PMID: 28411046]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Focosi D., Fazzi R., Montanaro D., Emdin M., Petrini M. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a haploidentical stem cell transplant recipient: a clinical, neuroradiological and virological response after treatment with risperidone. Antiviral Res. 2007;74(2):156–158. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.10.011. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.10.011]. [PMID: 17140673]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Baker H., Bannister R., Rothaul A. 2004.

- 109.Wallet M.A., Reist C.M., Williams J.C., Appelberg S., Guiulfo G.L., Gardner B., Sleasman J.W., Goodenow M.M. The HIV-1 protease inhibitor nelfinavir activates PP2 and inhibits MAPK signaling in macrophages: a pathway to reduce inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012;92(4):795–805. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0911447. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0911447]. [PMID: 22786868]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gantt S., Gachelet E., Carlsson J., Barcy S., Casper C., Lagunoff M. Nelfinavir impairs glycosylation of herpes simplex virus 1 envelope proteins and blocks virus maturation. Adv. Virol. 2015;2015:687162. doi: 10.1155/2015/687162. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/687162]. [PMID: 25709648]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chou D.H., Bodycombe N.E., Carrinski H.A., Lewis T.A., Clemons P.A., Schreiber S.L., Wagner B.K. Small-molecule suppressors of cytokine-induced beta-cell apoptosis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5(8):729–734. doi: 10.1021/cb100129d. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cb100129d]. [PMID: 20550176]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Guendel I., Agbottah E.T., Kehn-Hall K., Kashanchi F. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 by cdk inhibitors. AIDS Res. Ther. 2010;7(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1742-6405-7-7]. [PMID: 20334651]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kim J.K., Park G.M. Indirubin-3-monoxime exhibits anti-inflammatory properties by down-regulating NF-kappaB and JNK signaling pathways in lipopolysaccharide-treated RAW264.7 cells. Inflamm. Res. 2012;61(4):319–325. doi: 10.1007/s00011-011-0413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Benson J.M., Shepherd D.M. Dietary ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor induce anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects on murine dendritic cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;124(2):327–338. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr249. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfr249]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Heredia A., Davis C., Bamba D., Le N., Gwarzo M.Y., Sadowska M., Gallo R.C., Redfield R.R. Indirubin-3′-monoxime, a derivative of a Chinese antileukemia medicine, inhibits P-TEFb function and HIV-1 replication. AIDS. 2005;19(18):2087–2095. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194805.74293.11. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000194805.74293.11]. [PMID: 16284457]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lotteau V., De Chassey B., Andre P., Meyniel-Schicklin L., Aublin-Gex A. Methods and pharmaceutical compositions for inhibiting influenza viruses replication. 2015.

- 117.Leu S.J., Yang Y.Y., Liu H.C., Cheng C.Y., Wu Y.C., Huang M.C., Lee Y.L., Chen C.C., Shen W.W., Liu K.J. Valproic acid and lithium meditate anti-inflammatory effects by differentially modulating dendritic cell differentiation and function. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017;232(5):1176–1186. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25604. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25604]. [PMID: 27639185]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nassar A., Azab A.N. Effects of lithium on inflammation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014;5(6):451–458. doi: 10.1021/cn500038f. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cn500038f]. [PMID: 24803181]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhao F.R., Xie Y.L., Liu Z.Z., Shao J.J., Li S.F., Zhang Y.G., Chang H.Y. Lithium chloride inhibits early stages of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) replication in vitro. J. Med. Virol. 2017;89(11):2041–2046. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24821. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24821]. [PMID: 28390158]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen Y., Kong D., Cai G., Jiang Z., Jiao Y., Shi Y., Li H., Wang C. Novel antiviral effect of lithium chloride on mammalian orthoreoviruses in vitro. Microb. Pathog. 2016;93:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.01.023. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2016.01.023]. [PMID: 26835657]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Amsterdam J.D., Maislin G., Hooper M.B. Suppression of herpes simplex virus infections with oral lithium carbonate--a possible antiviral activity. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16(6):1070–1075. [PMID: 8947995]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Forlenza O.V., Aprahamian I., de Paula V.J., Hajek T. Lithium, a therapy for AD: Current evidence from clinical trials of neurodegenerative disorders. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016;13(8):879–886. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160219112854. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1567205013666160219112854]. [PMID: 26892289]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wan W., DePetrillo P.B. Ritonavir protects hippocampal neurons against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Neurotoxicology. 2002;23(3):301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(02)00057-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0161-813X(02)00057-8]. [PMID: 12387358]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Antonopoulos A.S., Margaritis M., Lee R., Channon K., Antoniades C. Statins as anti-inflammatory agents in atherogenesis: molecular mechanisms and lessons from the recent clinical trials. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012;18(11):1519–1530. doi: 10.2174/138161212799504803. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/138161212799504803]. [PMID: 22364136]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Feng Y., Lei B., Zhang F., Niu L., Zhang H., Zhang M. Anti-inflammatory effects of simvastatin during the resolution phase of experimentally formed venous thrombi. J. Clin. Res. 2017;65(6):999–1007. doi: 10.1136/jim-2017-000442. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jim-2017-000442]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Patel K., Lim S.G., Cheng C.W., Lawitz E., Tillmann H.L., Chopra N., Altmeyer R., Randle J.C., McHutchison J.G. Open-label phase 1b pilot study to assess the antiviral efficacy of simvastatin combined with sertraline in chronic hepatitis C patients. Antivir. Ther. (Lond.) 2011;16(8):1341–1346. doi: 10.3851/IMP1898. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3851/IMP1898]. [PMID: 22155916]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mihaila R.G., Nedelcu L., Fratila O., Retzler L., Domnariu C., Cipaian R.C., Rezi E.C., Beca C., Deac M. Effects of simvastatin in patients with viral chronic hepatitis C. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58(109):1296–1300. doi: 10.5754/hge08074. [http://dx.doi.org/10.5754/hge08074]. [PMID: 21937398]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Li W., Cao F., Li J., Wang Z., Ren Y., Liang Z., Liu P. Simvastatin exerts anti-hepatitis B virus activity by inhibiting expression of minichromosome maintenance protein 7 in HepG2.2.15 cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016;14(6):5334–5342. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5868. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2016.5868]. [PMID: 27779671]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Feinstein M.J., Achenbach C.J., Stone N.J., Lloyd-Jones D.M. A Systematic review of the usefulness of statin therapy in HIV-infected patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015;115(12):1760–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.025. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.025]. [PMID: 25907504]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hui K.P., Kuok D.I., Kang S.S., Li H.S., Ng M.M., Bui C.H., Peiris J.S., Chan R.W., Chan M.C. Modulation of sterol biosynthesis regulates viral replication and cytokine production in influenza A virus infected human alveolar epithelial cells. Antiviral Res. 2015;119:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.04.005. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.04.005]. [PMID: 25882623]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ponroy N., Taveira A., Mueller N.J., Millard A.L. Statins demonstrate a broad anti-cytomegalovirus activity in vitro in ganciclovir-susceptible and resistant strains. J. Med. Virol. 2015;87(1):141–153. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23998. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.23998]. [PMID: 24976258]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kanter C.T., Luin Mv., Solas C., Burger D.M., Vrolijk J.M. Rhabdomyolysis in a hepatitis C virus infected patient treated with telaprevir and simvastatin. Ann. Hepatol. 2014;13(4):452–455. [PMID: 24927617]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mehrbod P., Hair-Bejo M., Tengku Ibrahim T.A., Omar A.R., El Zowalaty M., Ajdari Z., Ideris A. Simvastatin modulates cellular components in influenza A virus-infected cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014;34(1):61–73. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1761. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2014.1761]. [PMID: 24788303]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]