Abstract

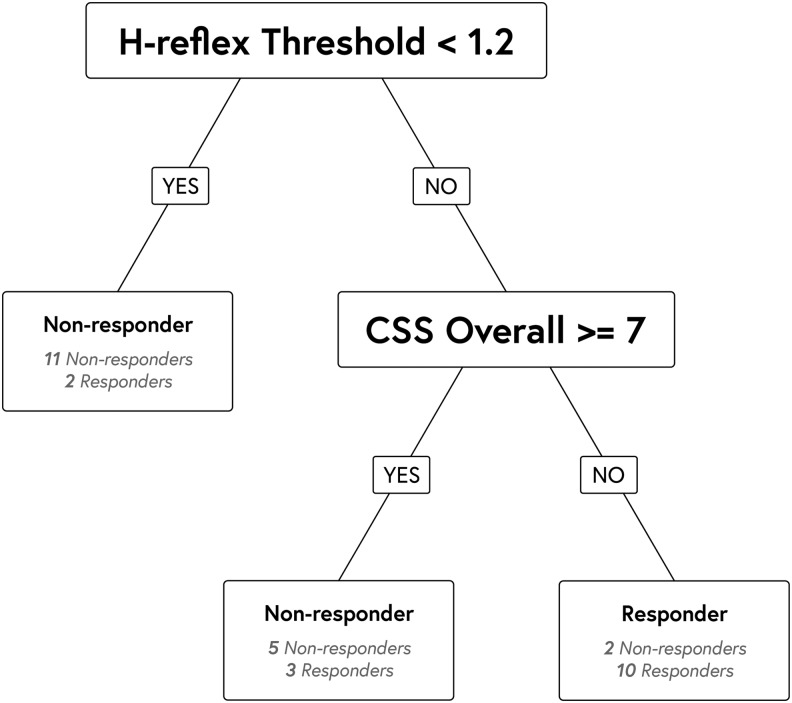

4-Aminopyridine (4AP), a potassium channel antagonist, can improve hindlimb motor function in dogs with chronic thoracolumbar spinal cord injury (SCI); however, individual response is variable. We hypothesized that injury characteristics would differ between dogs that do and do not respond to 4AP. Our objective was to compare clinical, electrodiagnostic, gait, and imaging variables between dogs that do and do not respond to 4AP, to identify predictors of response. Thirty-four dogs with permanent deficits after acute thoracolumbar SCI were enrolled. Spasticity, motor and sensory evoked potentials (MEPs, SEPs), H-reflex, F-waves, gait scores, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) were evaluated at baseline and after 4AP administration. Baseline variables were assessed as predictors of response; response was defined as ≥1 point change in open field gait score. Variables were compared pre- and post-4AP to evaluate 4AP effects. Fifteen of 33 (45%) dogs were responders, 18/33 (55%) were non-responders and 1 was eliminated because of an adverse event. Pre-H-reflex threshold <1.2 mA predicted non-response; pre-H-reflex threshold >1.2 mA and Canine Spasticity Scale overall score <7 were predictive of response. All responders had translesional connections on DTI. MEPs were more common post-4AP than pre-4AP (10 vs. 6 dogs) and 4AP decreased H-reflex threshold and increased spasticity in responders. 4-AP impacts central conduction and motor neuron pool excitability in dogs with chronic SCI. Severity of spasticity and H-reflex threshold might allow prediction of response. Further exploration of electrodiagnostic and imaging characteristics might elucidate additional factors contributing to response or non-response.

Keywords: canine, chronic SCI, motor neuron pool excitability, potassium channel antagonist, spasticity

Introduction

Severe spinal cord injury (SCI) in people and dogs commonly results in permanent functional impairment. Although injuries classified functionally as complete (no pain perception or motor below the level of injury) presume disconnection from all supraspinal influence, physical transection of the spinal cord is uncommon.1–3 Preserved rims of tissue, typically subpial in location, have been demonstrated traversing the site of severe injury on histopathology in people and animals.1–6 Evidence of spinal cord continuity on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) among people with complete injuries has also been noted.7 Using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), we have presented evidence of structural continuity and, along with others, we have demonstrated motor conduction across severe injury and in some chronically paralyzed dogs.8–10 Although motor evoked potentials (MEPs) were recordable in a subset of these SCI dogs, amplitude was small and latencies notably delayed compared with normal values. These data suggest that a percentage of axons can survive severe injury, but might be rendered dysfunctional because of demyelination preventing conduction of the action potential.

4-Aminopyridine (4AP), a potassium channel antagonist, has been evaluated as a treatment for SCI specifically aimed at restoring function to anatomically intact but physiologically dysfunctional axons across the injury site. 4AP primarily exerts its effect by blocking exposed fast-gated potassium channels in demyelinated axons, although it also has other mechanisms of action including increasing synaptic transmission at the pre-synaptic level.11–14 Prior studies in people with SCI have shown that 4AP can improve electrodiagnostic measures of central conduction including higher amplitude, lower stimulation threshold, and shorter latency MEPs.15–17 However, functional benefits at clinically safe doses of 4AP or its derivatives have generally been modest and appear more prominent in people with incomplete injuries.15,16,18–21 Targeting patients with complete injuries in whom there is MRI evidence of cord continuity with higher doses resulted in some functional improvements, but the benefits must be balanced with the greater likelihood of side effects as the dose increases.7 Blight and coworkers reported similar effects in chronically weak or paralyzed dogs after naturally occurring SCI, in which approximately two thirds showed varying degrees of functional improvement after a single dose.5 However, all but one dog with no pain perception at the time of evaluation showed no overt change in neurological function after administration of 4AP.5 In a placebo-controlled crossover clinical trial of 19 chronically non-ambulatory pain perception negative dogs, administration of 4AP and its T-Butyl carbamate derivative resulted in an improvement in stepping function compared with placebo; however, the benefit was very variable among individuals, ranging from no response to restoration of independent ambulation.22

Despite promise as a potential therapy for human SCI, disappointing clinical trial results, the narrow therapeutic window, and variable response among individuals have limited the widespread use of 4AP.19,22 However, given the variability in pathology among individuals, it is possible that a subgroup of patients can be identified who would benefit from this treatment strategy. The purpose of this study was to identify predictors of response to 4AP in chronically paralyzed dogs. We hypothesized that there would be significant differences in one or more of clinical, electrodiagnostic, gait, and imaging variables between dogs that do and those that do not respond to 4AP. Our objective was to compare spasticity severity, translesional motor and sensory conduction, measures of motor neuron pool excitability, gait scores, and lesion characteristics on conventional MRI and DTI between dogs that do and those that do not respond to 4AP among a population with chronic motor and sensory impairment after acute, functionally complete SCI.

Methods

Case selection

Dogs were recruited prospectively from the patient pool of the Canine Spinal Cord Injury Program at the North Carolina State University (NCSU) College of Veterinary Medicine and via trial advertisement online (https://cvm.ncsu.edu/research/labs/clinical-sciences/canine-spinal-cord-injury/, www.dodgerslist.com). To be included, dogs must have sustained an acute, clinically complete (hindlimb paralysis with loss of pain perception) thoracolumbar SCI and demonstrated an incomplete recovery at least 3 months following injury characterized by chronic motor deficits and severely reduced to absent hindlimb and tail pain perception (with or without urinary and fecal incontinence). Dogs with concurrent health issues precluding general anesthesia or sedation and dogs with seizure disorders were excluded. For this study, dogs underwent baseline (pre-4AP) and post-4AP evaluation of spasticity, gait, and long tract and local circuitry function using electrodiagnostics and structural lesion severity using MRI (Table 1). Brief explanations of the procedures performed are provided subsequently in this article. Baseline. spasticity, electrodiagnostic, and imaging results for a subset of this population have been reported previously and should be referenced for a more detailed description of procedures.9,10,23,24 Informed consent was obtained for all animals and examinations were conducted in accordance with the NCSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #15-004-01).

Table 1.

| Study day | Tests/activities performed |

|---|---|

| Day 1 – Baseline | Neurological examination |

| Gait analysis (open field, treadmill stepping, and coordination scores) | |

| Spasticity testing | |

| Electrodiagnostic testing (MEPs, SEPs, NCS, F-wave, H-reflex) | |

| MRI with DTI | |

| Establish test dose for 4AP (8–12 h between 4AP doses) | |

| Day 2 – Post-4AP | Administer test dose of 4AP |

| As for Day 1, except no MRI |

MEP, motor evoked potential; SEP, sensory evoked potential; NCS, nerve conduction study; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; 4AP: 4-aminopyridine.

4AP protocol

Dogs were admitted to the hospital at the North Carolina State Veterinary Hospital for baseline (pre-4AP) procedures, drug titration, and then repeat testing of the same procedures post-administration of 4AP. The targeted dose for this study was determined based on prior evaluation of 4AP in chronically non-ambulatory dogs.22 Compounded 4AP oral capsules were specifically prepared for this study and included 1 mg, 2.5 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg sizes. Using each dog's current body weight, the appropriate combination of capsules was used to achieve a dose of ∼0.5–0.75 mg/kg given orally. If that dose was well tolerated with no apparent side effects, each dog received a second dose of ∼0.75–1 mg/kg orally at least 8 h after the initial dose and if tolerated, this dose was used for subsequent testing (test dose). If a dog displayed drug-related anxiety at the higher dose, the lower dose was used as the test dose. If more severe side effects were noted (tremors, generalized seizures) the drug was discontinued, and the dog was withdrawn from the study. On the 2nd day, each dog was administered the test dose of 4AP and 1 h later all baseline procedures were repeated using the same protocols except MRI. MRI was only performed at baseline. Dogs were monitored during the study period for adverse drug reactions or other adverse events. Seizure activity was treated with 0.25 mg/kg midazolam IV, repeated if necessary, and 4AP was discontinued and the dog was withdrawn from the study. Excessive anxiety was treated by discontinuation of 4AP and administration of 0.25 mg/kg midazolam or other sedative (such as butorphanol) at the discretion of study investigators. 4AP was reintroduced at a lower dose the following day. Any other adverse events were recorded and treated accordingly at the discretion of investigators.

Standard neurological and gait evaluation

All dogs underwent a neurological examination including standard evaluation of gait, proprioception, spinal reflexes, and pain perception. Dogs were also walked on a non-slip surface and on a treadmill for ∼3 min with the speed adjusted to a comfortable pace for each individual. Sling support was provided for the pelvic limbs as needed. All gait examinations were videotaped including footage with and without sling support. Gait was categorized as ambulatory (able to take at least 10 consecutive weight-bearing steps unassisted) or not, and quantified using an ordinal, open field scale (OFS) that ranges from 0 to 12.25,26 Treadmill footage was scored using previously described measures of pelvic limb stepping (stepping score) and coordination (regularity index).27,28 Treadmill scores (stepping score and regularity index) were generated without sling support for the statistical analysis unless otherwise specified.

Spasticity evaluation

Spasticity testing was performed for all dogs using the Canine Spasticity Scale adapted from human clinical scales.23 The Canine Spasticity Scale is composed of the assessment of patellar clonus duration and flexor spasm duration and degree on each pelvic limb with a standard scoring system developed for each component.23 Ordinal scores (0–3) were assigned for each pelvic limb for each scale component (patellar clonus duration, flexor spasm duration, flexor spasm degree) which were then summed to give a Canine Spasticity Scale overall score representing all components and both pelvic limbs (0–18).

Electrodiagnostic evaluation

Long tract function was evaluated by recording MEPs and cortical somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs), and local reflex circuitry was assessed by H-reflex, F-waves, and M-waves as previously reported.9 The presence (yes/no) and minimum latency of MEPs were recorded with the conduction velocity calculated from the latency. The presence (yes/no) and minimum latency of SSEPs and cord dorsum potentials were recorded. The minimum latency of the F-waves, F-wave persistence (percentage of F-waves present in 10 stimulations), and the F-ratio [(latency F − latency M −1)/ 2 × latency M] were recorded. The H-reflex threshold (stimulus intensity at which H-reflex first appeared), the minimum H-reflex latency, and the maximum H-reflex amplitude and maximum M-wave amplitude (defined as the largest negative to the largest positive peak for each waveform) were each recorded during H-reflex testing and used to calculate the H:M ratio (maximum H amplitude/maximum M amplitude).

Imaging acquisition and analysis

A subset of dogs were anesthetized and underwent thoracolumbar MRI at baseline. MRIs were performed using a 1.5T scanner (Symphony; Siemens Medical Solutions USA Inc., Malvern, PA) with acquisition of standard transverse and sagittal sequences (T1W pre- and post-contrast, T2W, short-TI inversion recovery [STIR], half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo [HASTE], ± proton density and gradient recalled echo [GRE]/T2*) followed by DTI obtained for the same region. Full imaging protocol and processing details have been reported.10,24 T2-weighted images were used to identify the lesion and to measure the length of the region within the lesion with 100% abnormal spinal cord signal intensity normalized to the length of the L2 vertebral body.24 Post-processed DTI images were imported into Mango (http://ric.uthscsa.edu/mango/) in order to manually outline regions of interest (ROI) within the spinal cord above, below, and within the lesion epicenter. Fractional anisotrophy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) were calculated for each ROI constructed (cranial, lesion epicenter, caudal). Tensor maps displaying the orientation of tensors across all voxels were used to perform tractography using TrackVis (http://trackvis.org). Tractography was assessed visually for continuity (yes/no) of the represented white matter tracts across the lesion.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R (Version 3.3.0, http://cran.r-project.org/) and Jmp 13 Pro (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Responders to 4AP were defined as having an improvement in open field score ≥1 point between pre- and post-4AP administration, whereas non-responders were defined as showing no positive change. Summary statistics comparing responders and non-responders were reported for all baseline variables. The following variables at baseline were then assessed as predictors of response to 4AP: age, duration of injury, open field score, Canine Spasticity Scale overall score, H-reflex threshold, H:M ratio, presence of pelvic limb MEPs, length of the region with 100% abnormal signal intensity on T2W images relative to L2, FA for each ROI cranial to and within the lesion epicenter, and the presence of translesional fibers. A classification tree for the responder status was constructed using baseline patient characteristics and models were fit using R.29 Descriptive statistics were subsequently presented to demonstrate the effects of 4AP. With dogs separated into responder and non-responder groups, the following variables were investigated for changes pre- versus post-4AP in each group: Canine Spasticity Scale overall score, stepping score, regularity index, H-reflex threshold, H:M ratio, F ratio, and motor nerve conduction velocity. Additionally, the number of dogs with detectable MEPs or SSEPs at baseline and post-4AP administration was reported.

Results

Thirty-four dogs were enrolled. There were 14 Dachshunds, 10 mixed breed dogs, 3 Pit Bull Terriers, 2 Australian Cattle dogs, and 1 each of Shih Tzu, Boston Terrier, Miniature Poodle, English Bulldog, and Miniature Schnauzer. Median body weight was 7.65 kg (range 3.1–33). The mean age was 5.97 years (SD 2.55), and median duration of injury was 17 months (range 3–84). Intervertebral disc herniation was the most common diagnosis (26 dogs) followed by vertebral column fracture (4 dogs), fibrocartilaginous embolism (2 dogs), and traumatic intervertebral disc extrusion (2 dogs). In all dogs, neurolocalization was between the third thoracic and third lumbar spinal cord segments based on neurological examination findings. Thirty-two dogs had no pelvic limb or tail pain perception, whereas one dog had a severely blunted response in the medial and lateral toes of the left hind limb, and one dog had a subtle response in the medial toe of the left hind limb. The median open field score for all dogs at enrollment was 2 (range 0–9), the median stepping score was 0 (0–89), and the median regularity index was 0 (0–46.56). Seven of 34 (21%) dogs were independently ambulatory and 27/34 (79%) were non-ambulatory, including 4 dogs who took some weight-bearing steps (open field score = 4). Treatments at the time of acute injury were variable and depended on the underlying cause. Among dogs with a diagnosis of intervertebral disc herniation or fracture/luxation, surgery (decompression ± stabilization) was performed in 16 dogs and medical management with or without formal rehabilitation therapy was performed in 14 dogs.

Mean drug dosage used for post-4AP testing (test dose) was 0.78 mg/kg (SD 0.05). All dogs received at least three doses of 4AP (one at ∼0.5 mg/kg and two at ∼0.75mg/kg) during the study, each separated by at least 8 h. Adverse events potentially related to 4-AP were noted in six dogs, consisting of seizure activity (one dog), anxiety (five dogs). The mean test dose among the six dogs with possible drug-related adverse effects was 0.79 mg/kg. One dog had a generalized seizure after receiving the second of the test doses of 4AP (0.77 mg/kg). This resolved with 0.25 mg/kg IV midazolam and drug discontinuation, and the patient had no further seizure activity or drug-related effects. This dog was withdrawn from the study. Five dogs demonstrated anxiety potentially attributable to the study drug. In three dogs, this was mild, and did not require treatment or adjustments to the dosing regimen. One dog exhibited a mild episode of anxiety 1–2 h after receiving the higher dose (0.8 mg/kg). No treatment was initiated, but the test dose was lowered to 0.7 mg/kg and was well tolerated for repeat testing. The dog remained on that dose after completion of the study with no anxiety or other side effects reported at home. One additional dog demonstrated increasing anxiety after receiving the test doses of the study drug (0.77 mg/kg). This patient was able to complete post-4AP testing, but was treated with 0.25 mg/kg IV midazolam and 0.2mg/kg IV butorphanol upon study completion because of progressive anxiety. Although 4AP was considered a factor, this dog also demonstrated moderate behavioral anxiety at baseline, likely attributable to separation from her owner and hospitalization. Excessive anxiety resolved with treatment and drug withdrawal, and no further issues were reported by her owner. The medication was otherwise well tolerated in remaining dogs.

All 34 dogs participated in spasticity and electrodiagnostic evaluation. One dog was removed from pre- and post-4AP electrodiagnostic analysis of local circuitry (H-reflex, F-waves) because of prior distal limb self-mutilation precluding reliable data capture. Twenty-two dogs underwent MRI (at baseline). One dog was removed from the study because of an adverse event and was eliminated from the responder/non-responder analysis. Fifteen of 33 (45%) dogs were responders and 18/33 (55%) were non-responders. Of the 15 dogs classified as responders, there was a mean change in open field score of 1.33 (SD 0.6). No dogs demonstrated changes in their pelvic limb or tail pain perception after drug administration.

Baseline continuous variables for responders (n = 15) and nonresponders (n = 18) are provided in Table 2. Additionally, two of 15 (13%) responders had detectable pelvic limb MEPs at baseline compared with 4/18 (22%) non-responders. No dogs had detectable SSEPs at baseline. All responders (15/15, 100%) had translesional fibers, whereas all four dogs with absent connections on tractography were in the non-responder group, resulting in 14/18 (78%) non-responders with intact translesional fibers. The classification tree model found that a baseline H-reflex threshold <1.2 mA was predictive of being a non-responder, and that H-reflex threshold >1.2 mA combined with a baseline Canine Spasticity Scale overall score <7 were together predictive of being a responder (Fig. 1). No other baseline variables (or combinations of variables) evaluated were found to be predictive of response to 4AP. Considering only the responders, the Canine Spasticity Scale overall score increased, the stepping score increased, and the H-reflex threshold decreased after administration of 4AP (Table 3). Similar changes were not detected in any variables after 4AP among the non-responder group (Table 3). Detectable MEPs were more common post-4AP than pre-4AP, present in 10 dogs (3 responders, 7 non-responders) versus 6 (2 responders, 4 non-responders) at baseline. Of the two responding dogs that had MEPs both before and after 4AP, conduction velocity increased in one after 4AP (from 16.7 m/sec before to 22 m/sec after), and decreased in the other (from 13.4 m/sec before to 9.5 m/sec after). No dogs had detectable SSEPs post-4AP.

Table 2.

Comparison of Clinical, Spasticity, Electrodiagnostic, Gait, and Imaging Variables between Responders and Non-Responders to 4AP

| Baseline variable | Mean (SD) or median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Responders | Non-responders | |

| Age (years) | 5.5 (2.6) | 6.26 (2.49) |

| DOI (months) | 17 (3–69) | 18 (3–84) |

| Body weight (kg) | 7.1 (3.7–33) | 8 (3.1–29) |

| Limb length (cm) | 25.2 (18.5–48) | 26 (20.5–53) |

| CSS Overall Score | 6.88 (2.6) | 8.26 (2.4) |

| PL MEP CV | 15.05 (2.33) | 13.41 (3.89) |

| F ratio | 1.79 (0.57) | 1.97 (0.89) |

| H:M ratio | 0.28 (0.2) | 0.29 (0.17) |

| H-reflex threshold | 2.1 (0.3–9.4) | 1.1 (0.1–7.8) |

| OFS | 2 (0–6) | 2 (0–9) |

| Stepping score | 0 (0–75) | 0 (0–89) |

| Regularity index | 0 (0–34.29) | 0 (0–46.56) |

| Length 100% MSCC: L2 | 0.88 (0.84) vs. 0.65 (0–2.49) | 1.31 (1.5) vs. 0.86 (0–5.24) |

| FA cranial | 0.44 (0.039) | 0.44 (0.055) |

| FA lesion | 0.23 (0.056) | 0.22 (0.047) |

| FA caudal | 0.39 (0.073) | 0.37 (0.06) |

| MD cranial | 0.0015 (0.0002) | 0.0015 (0.0003) |

| MD lesion | 0.0021 (0.0003) | 0.0020 (0.0004) |

| MD caudal | 0.0014 (0.0003) | 0.0013 (0.0004) |

DOI: duration of injury; CSS: Canine Spasticity Scale; PL, pelvic limb; MEP, motor evoked potential; CV, conduction velocity; length 100% MSCC:L2, length of the region within the lesion with 100% abnormal T2-weighted signal intensity relative to L2 vertebral body length; FA, fractional anisotropy; MD, mean diffusivity.

FIG. 1.

Classification tree. This diagrammatic representation of the statistical analysis demonstrates the numbers of responders and non-responders that clustered above or below certain values for the H-reflex threshold and the overall spasticity score. CSS Overall: Canine Spasticity Scale Overall Score.

Table 3.

Comparison of Spasticity, Electrodiagnostic, and Gait Analysis Variables between Baseline and Post-4AP Administration among Responders (n = 15) and Non-Responders (n = 18)

| Responders (n = 15) | Non-responders (n = 18) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) or median (range) | Mean (SD) or median (range) | ||

| Pre-4AP | Post-4AP | Pre-4AP | Post-4AP | |

| CSS Overall Score | 6.2 (2.54) | 7.6 (2.77) | 8.20 (2.43) | 8.64 (2.73) |

| Stepping score | 0 (0–49) | 0 (0–64) | 0 (0–89) | 0 (0–90) |

| Regularity index | 0 (0–18.79) | 0 (0–23.08) | 0 (0–46.56) | 0 (0–58.95) |

| H:M ratio | 0.22 (0.16) | 0.18 (0.12) | 0.28 (0.16) | 0.28 (0.22) |

| H-reflex threshold | 2.2 (0.3–8.8) | 1.4 (0.7–8) | 1.0 (0.1–7.8) | 1.2 (0.5–7.6) |

| F ratio | 1.75 (0.6) | 2.2 (1.15) | 1.98 (0.91) | 1.80 (0.47) |

| MNCV | 78.67 (11.37) | 79.47 (14.03) | 76.83 (10.55) | 78.94 (11.10) |

4AP, 4-aminopyridine; CSS, Canine Spasticity Scale; MNCV, motor nerve conduction velocity.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that a combination of electrodiagnostic and clinical variables focusing on evaluation of motor neuron pool excitability can identify responders to 4AP among a population of dogs that exhibit chronic impairment after sustaining a prior acute, complete SCI. Specifically, measurement of H-reflex threshold and spasticity severity showed that 4AP enhanced motor neuron pool excitability in dogs in which this was depressed. Additionally, some degree of long tract integrity appeared integral to potential response, because no dogs with absent translesional fibers on tractography were responders, and pelvic limb MEPs were more readily detected post-4AP than pre-4AP. On the basis of these results, electrodiagnostic and advanced imaging evaluation of local circuitry and long tract integrity in a larger cohort may enhance understanding of the mechanisms underlying the variable response, and help to identify dogs in whom 4AP may be a useful therapy.

Using a classification tree model to explore potential predictors of response, the H-reflex, an electrodiagnostic measure of motor neuron pool excitability, and Canine Spasticity Scale overall score were identified. We have previously reported H-reflex findings and developed a novel scale for quantifying spasticity in dogs with chronic SCI, allowing enhanced evaluation of local reflex circuitry and spinal cord function below the level of injury.9,23 We found that dogs with a lower H-reflex threshold and higher spasticity scores had higher motor scores, suggesting that excitability of the motor neuron pool was important in motor recovery.9,23 Although H-reflex has previously been reported to remain unchanged after administration of 4AP in people with SCI, our results suggest that this might be worthy of further investigation in this population.16,17,20 The finding that a lower H-reflex threshold intensity, indicative of increased motor neuron pool excitability, was predictive of non-response might suggest that there is limited functional benefit of 4AP in dogs with chronic SCI when this neuronal population is already in a state of greater excitability.30,31 Similarly, the combination of a higher H-reflex threshold and lower spasticity score (i.e., less spastic patients with decreased motor neuron pool excitability) was predictive of response, which again suggests that 4AP exerts at least part of its functional benefit by enhancing excitability. Comparing pre and post-4AP changes provided further support, because 4AP administration lowered H-reflex threshold and increased spasticity (i.e., enhancing excitability) in responders but had no effect on non-responders. However, because of low study power, these changes were not examined statistically, precluding making significant conclusions based on the current data. We have previously shown that motor neuron pool excitability is more likely to be depressed among dogs with more severe motor deficits.9 As such, subsequent exploration into the relationship between enhancing excitability and response might focus on a larger number of exclusively non-ambulatory dogs.

Enhanced central conduction has been previously reported as the main mechanism of action of 4AP.11 In people with chronic SCI, 4AP administration improved MEP latency, conduction velocity and amplitude.15–17 Additionally, spinal cord continuity on T1W images in people with functionally complete lesions has been associated with a favorable response to 4AP.7 Consistent with this, we found that none of the four dogs with complete disruption of fibers on tractography were responders. Although lack of connections across the injury site appeared to preclude the drug from exerting a beneficial effect on function, we were unable to demonstrate a relationship between continuity on tractography and response, perhaps because of the low study power and limitations of the sensitivity of tractography to determine the percentage of residual fibers. We also found that the number of dogs with recordable pelvic limb MEPs increased from 6 at baseline to 10 after 4AP administration. However, only 3/10 dogs who had MEPs at baseline or after 4AP were classified as responders. This suggests that the mere presence of translesional fibers (documented via transcranial magnetic stimulation [TMS] or tractography) does not guarantee a favorable response. It is possible that 4AP might enhance central conduction in dogs without producing a notable change in pelvic limb motor function, but there were no consistent changes in MEP variables among the six dogs with MEPs both pre- and post-4AP. Although the sensitivity for measuring MEPs is low in dogs with severe injury, our results indicate that 4AP in dogs might exert more of a synaptic effect with a lesser impact on central conduction than in people with SCI.32 Improved ability to detect and quantify connections traversing the site of severe injury, and evaluation of a larger number of dogs with and without translesional (functional or structural) connections might help to clarify the relationship among changes in central conduction, the percentage of translesional fibers present, and clinical response to 4AP in this population.

Although we investigated a variety of clinical, electrophysiological and imaging variables, it remains possible that there are other, as yet unidentified, predictors of response to 4AP in dogs with SCI. The average 4AP test dose was 0.79 mg/kg. It is possible that further dose escalation might have resulted in classification of additional dogs as responders, potentially uncovering predictors of response. However, doses >1 mg/kg have been associated with increased drug-related side effects and do not necessarily produce a predictable, progressive increase in function.5,22 The prior blinded trial in dogs administered 4AP for 2 weeks, whereas we only investigated the effects of a single dose, limiting direct comparisons between these studies regarding the relationship between dose and response.22 Although the drug was generally well tolerated, 6/34 (20%) dogs exhibited side effects (anxiety in five and seizures in one) that could be attributed to the study medication. The mean 4AP dose among these dogs (0.79 mg/kg) was comparable to the average dose for the entire population (0.79 mg/kg). Five of the six were still able to complete post-4AP evaluation, with three classified as responders and two classified as non-responders. This highlights that some dogs will be more sensitive to adverse effects at appropriate doses, and that dose alone does not predict response in this population.

Limitations of this study included the small number of dogs, and using a conservative definition for a responder (1+ increase in open field score). This may have decreased our ability to detect potential differences between groups. Only four dogs demonstrated a more pronounced change in open field score (including an increase of 2 points in two dogs and 3 points in one dog), precluding the ability to analyze the data using open field score change ≥2 points as the definition of being a responder. It is possible that evaluating a combination of the ordinal open field scores as well as continuous treadmill-based stepping and regularity index scores to define response versus non-response would be more useful. We also purposely chose a group of dogs with severe SCI but a range of impairment, in order to explore potential predictors of response. As such, this study was not designed as a clinical trial for efficacy, but rather as a mechanistic study with the goal of identifying factors underlying the variable response to 4AP in this population. Future studies in a larger number of dogs with incomplete recovery focusing on electrodiagnostic and imaging evaluation at baseline are warranted to confirm and extend these results. Additionally, because this was a mechanistic study, we only evaluated dogs at one time point after a single oral dose (three total if titration is included) and, therefore, it is possible that benefits might have become apparent if dogs were re-evaluated on multiple occasions or after receiving a larger number of doses. Prior pharmacokinetic evaluation and studies in dogs and cats, however, have shown detectable effects within minutes after IV injection and within an hour after single oral dose with peak plasma levels in dogs occurring at 2–3 h after administration.5,33,34

Overall, our findings suggest that 4AP increases motor neuron pool excitability in a population of dogs with chronic SCI that are identified by low spasticity and high H-reflex thresholds. However, spinal cord continuity also appeared integral to response, and, therefore, it is possible that multiple factors contribute to response or non-response that will only become apparent through additional studies in a larger number of dogs. Our results suggest that investigation of specific injury features and baseline characteristics might allow reliable identification of responders as well as improve understanding of the relationship between lesion severity and functional status in dogs with severe, chronic SCI. This will not only facilitate tailored therapy regimens, but will also enable targeted clinical trial recruitment among this heterogeneous population, with application to human SCI.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by T32 OD011130 - Comparative Medicine and Translational Research Training Program and the North Carolina Research and Innovation Seed Fund. We thank Kimberly Williams for her assistance, which allowed for successful completion of this project.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Hayes K.C., and Kakulas B.A. (1997). Neuropathology of human spinal cord injury sustained in sports-related activities. J. Neurotrauma 14, 235–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kakulas B.A., and Kaelan C. (2015). The neuropathological foundations for the restorative neurology of spinal cord injury. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 129, S1–S7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griffiths I.R. (1978). Spinal cord injuries: a pathological study of naturally occurring lesions in the dog and cat. J. Comp. Pathol. 88, 303–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basso D.M., Beattie M.S., and Bresnahan J.C. (1996). Graded histological and locomotor outcomes after spinal cord contusion using the NYU weight-drop device versus transection. Exp. Neurol. 139, 244–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blight A.R., Toombs J.P., Bauer M.S., and Widmer W.R. (1991). The effects of 4-aminopyridine on neurological deficits in chronic cases of traumatic spinal cord injury in dogs: a phase I clinical trial. J. Neurotrauma 8, 103–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith P.M., and Jeffery N.D. (2010). Histological and ultrastructural analysis of white matter damage after naturally-occurring spinal cord injury. Brain Pathol. 16, 99–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grijalva I., Garcia-Perez A., Diaz J., Aguilar S., Mino D., Santiago-Rodriguez E., Guizar-Sahagun G., Castaneda-Hernandez G., Maldonado-Julian H., and Madrazo I. (2010). High doses of 4-aminopyridine improve functionality in chronic complete spinal cord injury patients with MRI evidence of cord continuity. Arch. Med. Res. 41,567–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Granger N., Blamires H., Franklin R., and Jeffery N.D. (2012). Autologous olfactory mucosal cell transplants in clinical spinal cord injury: a randomized double-blinded trial in a canine translational model. Brain 135, 3227–3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewis M.J., Howard J.F., and Olby N.J. (2017). The relationship between trans-lesional conduction, motor neuron pool excitability, and motor function in dogs with incomplete recovery from severe spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 34, 2994–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewis M.J., Yap P.T., McCullough S., and Olby N.J. (2018). The relationship between lesion severity characterized by diffusion tensor imaging and motor function in chronic canine spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 35, 500–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blight A.R. (1989). Effect of 4-aminopyridine on axonal conduction-block in chronic spinal cord injury. Brain Res. Bull. 22, 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burley S., and Jacobs R.S. (1981). Effects of 4-aminopyridine on nerve terminal action potentials. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 219, 268–273 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sherratt R.M., Bostock H., and Sears T.A. (1980). Effects of 4-aminopyridine on normal and demyelinated mammalian nerve fibers. Nature 283, 570–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith K.J., Felts P.A., and John G.R. (2000). Effects of 4-aminopyridine on demyelinated axons, synapses and muscle tension. Brain 123,171–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hayes K.C., Potter P.J., Wolfe D.L., Hsieh J., Delaney G.A., and Blight A.R. (1994). 4-aminopyridine-sensitive neurologic deficits in patients with spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 11, 433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qiao J., Hayes K.C., Hsieh J., Potter P.J., and Delaney G.A. (1997). Effects of 4-aminopyridine on motor evoked potentials in patients with spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 14, 135–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wolfe D.L., Hayes K.C., Hsieh J., and Potter P.J. (2001). Effects of 4-aminopyridine on motor evoked potentials in patients with spinal cord injury: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J. Neurotrauma 18, 757–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cardenas D.D., Ditunno J.F., Graziani V., McLain A.B., Lammertse D.P., Potter P.J., Alexander M.S., Cohen R., and Blight A.R. (2014). Two phase 3, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of fampridine-SR for treatment of spasticity in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 52, 70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansebout R.R., Blight A.R., Fawcett S., and Reddy K. (1993). 4-aminopyridine in chronic spinal cord injury: a controlled, double-blind, crossover study in eight patients. J. Neurotrauma 10, 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayes K.C., Blight A.R., Potter P.J., Allatt R.D., Hseih J., Wolfe D.L., Lam S., and Hamilton J.T. (1993). Preclinical trial of 4-aminopyridine in patients with chronic spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 31, 216–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Potter P.J., Hayes K.C., Segal J.L., Hsieh J.T.C., Brunnemann S.R., Delaney G.A., Tierney D.S., and Mason D. (1998). Randomized double-blind crossover trial of fampridine-SR (sustained release 4-aminopyridine) in patients with incomplete spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 15, 837–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lim J.H., Muguet-Chanoit A.C., Smith D.T., Laber E., and Olby N.J. (2014). Potassium channel antagonists 4-aminopyridine and the T-butyl carbamate derivative of 4-aminopyridine improve hind limb function in chronically non-ambulatory dogs; a blinded, placebo-controlled trial. PLOS One 9, e116139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lewis M.J., and Olby N.J. (2017). Development of a clinical spasticity scale for evaluation of dogs with chronic thoracolumbar spinal cord injury. Am. J. Vet. Res. 78, 854–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lewis M.J., Cohen E.B., and Olby N.J. (2018). Magnetic resonance imaging features of dogs with incomplete recovery after acute, severe spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 56,133–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olby N.J., De Risio L., Munana K.R., Wosar M.A., Skeen T.M., Sharp N.J.H., and Keene B.W. (2001). Development of a functional scoring system in dogs with acute spinal cord injuries. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62, 1624–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Olby N.J., Muguet-Chanoit A.C., Lim J.H., Davidian M., Mariani C.L., Freeman A.C., Platt S.R., Humphrey J., Kent M., Giovanella C., Longshore R., Early PJ., and Munana K.R. (2016). A placebo-controlled, prospective, randomized clinical trial of polyethylene glycol and methylprednisolone sodium succinate in dogs with intervertebral disk herniation. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 30, 206–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koopmans G.C., Deumens R., Honig W.M., Hamers F.P., Steinbusch H.W., and Joosten E.A. (2005). The assessment of locomotor function in spinal cord injured rats: the importance of objective analysis of coordination. J. Neurotrauma 22,214–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Olby N.J., Lim J.H., Babb K., Bach K., Domaracki C., Williams K., Griffith E., Harris T., and Muguet-Chanoit A. (2014). Gait scoring in dogs with thoracolumbar spinal cord injuries when walking on a treadmill. BMC Vet. Res. 10, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Breiman L., Friedman J.H., and Olshen R.A. (1984). Classification and Regression Trees. Wadsworth, Belmont,CA [Google Scholar]

- 30. Languth H.W., Teasdall R.D., and Magladery J.W. (1952). Electrophysiological studies of reflex activity in patients with lesions of the nervous system. III. Motoneuron excitability following afferent nerve volleys in patients with rostrally adjacent spinal cord damage. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp. 9, 1257–1266 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Magladery J.W. (1958). Stretch reflexes in patients with spinal cord lesions. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp. 103, 236–241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sylvestre A.M., Cockshutt J.R., Parent J.M., Brooke J.D., Holmberg D.L., and Partlow G.D. (1993). Magnetic motor evoked potentials for assessing spinal cord integrity in dogs with intervertebral disc disease. Vet. Surg. 22, 5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jankowska E., Lundberg A., Rudomin P., and Sykova E. (1982). Effects of 4-aminopyridine on synaptic transmission in the cat spinal cord. Brain Res. 240, 117–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olby N.J., Smith D.T., Humphrey J., Spinapolice K., Parke N., Mehta P.M., Dise D., and Papich M. (2009). Pharmacokinetics of 4-aminopyridine derivatives in dogs. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Therap. 32, 485–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]