Abstract

Background:

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is a leading cause of dementia, and elucidating its genetic underpinnings is critical. FTLD research centers typically recruit patient cohorts that are limited by the center’s specialty and the ways in which its geographic location affects the ethnic makeup of research participants. Novel sources of data are needed to get population estimates of the contribution of variants in known FTLD-associated genes.

Methods:

We compared FLTD-associated genetic variants in microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT), progranulin (GRN), and chromosome nine open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72) from an academic research cohort and a commercial clinical genetics laboratory. Pathogenicity was assessed using guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and a rule-based DNA variant assessment system. We conducted chart reviews on patients with novel or rare disease-associated variants.

Results:

A total of 387 cases with FTLD-associated variants from the commercial (n=2,082) and 78 cases from the academic cohort (n=2,089) were included for analysis. In the academic cohort, the most frequent pathogenic variants were C9ORF72 expansions (63%, n=49), followed by GRN (26%, n=20) and MAPT (11%, n=9). Each gene’s contribution to disease was similarly ranked in the commercial laboratory but differed in magnitude: C9ORF72 (89%, n=345), GRN (6%, n=24), and MAPT (5%, n=19). Of the 37 unique GRN/MAPT variants identified, only six were found in both cohorts. Clinicopathological data from patients in the academic cohort strengthened classification of two novel GRN variant as pathogenic (p.Pro166Leufs*2, p.Gln406*) and one GRN variant of unknown significance as a possible rare risk variant (p.Cys139Arg).

Conclusion:

Differences in gene frequencies and identification of unique pathogenic alleles in each cohort demonstrate the importance of data sharing between academia and community laboratories. Using shared data sources with well-characterized clinical phenotypes for individual variants can enhance interpretation of variant pathogenicity and inform clinical management of at-risk patients and families.

Keywords: frontotemporal dementia, genetics, cognitive disorders, dementia, aging, attributable risk, variant classification

Introduction

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) describes a pathologically heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative disorders and is a leading cause of dementia in individuals younger than 65 years.1 Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), the associated syndrome, is characterized by progressive declines in behavior or language.2 Research over the past 2 decades has led to the discovery of multiple genes underlying autosomal dominant FTD.3 Among familial FTLD cases, ~15% are caused by dominantly inherited pathogenic variants in the genes encoding tau protein (MAPT)4 and the growth factor precursor gene granulin (GRN)5 or a pathogenic GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9ORF72.6 Within MAPT and GRN, there are a multitude of disease-associated alleles and variants of unknown or undetermined significance. The identification and characterization of variants in these genes, particularly for patients with family histories, could improve premortem diagnostic specificity. Early identification of disease-associated variants also provides insight into underlying protein pathology, as MAPT variants result in tauopathy, whereas GRN and C9ORF72 are associated with TDP-43 proteinopathy and have potential for concomitant motor neuron disease (i.e., in C9ORF72).

There is also growing sentiment in favor of genetic screening for family members of familial and sporadic cases of FTLD. Given this, it is increasingly important to continue to not only characterize the spectrum of disease-causing variants in genes associated with FTLD but also compare the risk attributable to the different known genes between commercial and academic centers. This will help ensure that patients are provided with the most current information during genetic testing. While epidemiological studies have been performed assessing frequency of different FTLD variants across multiple research centers,7–9 there is a scarcity of literature regarding potential differences in attributable risk for FTLD genes between academic vs commercial testing sites. Data from commercial testing centers lack the recruitment bias associated with specialty academic centers and may reflect broader sociodemographic populations, represent different testing indications, and have important implications when developing gene target-specific therapeutics. Academic centers contribute to the characterization of gene variant pathogenicity through collecting data such as imaging studies, family history, brain pathology, and patient symptomology critical to establishing confidence in the true risk posed by candidate variants. Merging data from academic and commercial centers is an important step in order to understand the true distribution of disease-associated variants.

In order to understand how commercial and academic centers compare, we describe two cohorts: patients seen at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Memory and Aging Center and patients who ordered genetic testing commercially in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified, clinical diagnostic laboratory.

Materials and methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

This research was accomplished as part of a larger dementia care pathway collaboration between the University of California Memory and Aging Center and Quest Diagnostics, and funding for the specific aims set forth in this paper was provided by Quest. Written informed consent was obtained from UCSF patients or surrogates prior to entry into the study, and the UCSF’s institutional review board (IRB) approved all aspects of this research. The goal of the dementia care pathway is to provide an innovative and interdisciplinary approach to the screening, diagnosis, and clinical management of patients with dementia and their families. UCSF researchers (JSY and NZRS) designed the study. No funders (including Quest Diagnostics) played a role in the design or implementation of the study. Patient data were de-identified such that no direct or indirect patient identifiers or protected health information was included, as defined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The two patients described in the clinical vignettes provided written informed consent to participate in clinical research and have the de-identified case details published.

Participants

UCSF cohort

Participants included in this study were 2,089 patients seen at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center between 1999 and May 2015 who received genetic testing as part of their participation in longitudinal research on neurodegenerative disease and healthy cognitive aging. Individuals with disease-associated variants in FTLD genes were identified and data extracted from a secure database that stores de-identified participant information. Only data from probands were reported (Figure S1). Family history and clinical diagnoses of UCSF patients were extracted from research records. Postmortem pathological data were reported when available.

Clinical laboratory cohort

Genetic data were obtained from 2,082 de-identified patient samples tested at a commercial clinical laboratory between 2011 and May 2015. Owing to differences in gene discovery, C9ORF72 was tested only from 2012 through May 2015. Only data from probands were included, except for C9ORF72 expansions, where the mode of test ordering does not allow differentiation of family members and probands (Figure S2). Only basic demographics (age at test ordering, sex) but not clinical or pathological data were available for this cohort.

Genetic screening

UCSF cohort

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using standard protocols (Gentra Puregene Blood Kit; Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). MAPT and GRN Sanger sequencing was performed on amplified coding and flanking noncoding regions. The presence of expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeats in C9ORF72 was detected using published two-step protocol; refer the “Supplementary materials” section).6 Samples were typically screened for variants in all pathogenic FTLD genes upon entry into research at UCSF. However, due to the nature of gene discovery, samples were retrospectively screened in batches for variants as new FTLD genes were identified (e.g., all samples from 1999 to 2011 were screened when C9ORF72 was identified in late 2011).

Clinical laboratory cohort

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood utilizing automated extraction protocols (AutoGenFlex STAR Fresh Blood Extraction Kit and AutoGenFlex Blood DNA Finishing Kit; AutoGen Inc., USA, Holliston, MA). PCR amplification followed by Sanger sequencing was performed on coding and noncoding flanking regions of MAPT and GRN. Expanded hexanucleotide repeats in C9ORF72 were detected using a standard protocol comparable to that described above.

Variant assessment

UCSF cohort

Variant classification was performed in a standardized manner by searching the literature and online databases for published occurrences and crosschecking genomic location, variant type, nucleotide changes, and predictions for biological effects on protein products (gene transcript IDs can be found in Table S1). Variants were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic and included in the study based on prior identification as a disease-causing variant, heterozygous genotype, very low/unobserved frequency in general population-based databases, prediction to be deleterious from online databases, and consistent clinical data.

Clinical laboratory cohort

Variant assessment was performed using a standardized, rule-driven, variant scoring algorithm,10 in concordance with the guidelines of American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG).11 The scoring algorithm takes into account multiple lines of evidence including variant type, variant location within the gene, predictive in silico algorithms, variant frequency data in patient and general population cohorts, family segregation, and functional studies.

Statistical analysis

Differences in continuous variables (i.e., age of testing) between the two cohorts were tested using ANOVA in R, with significance established at two-tailed P<0.05.

Results

A retrospective analysis was performed on 2,089 individuals at an academic center and 2,082 individuals at a commercial laboratory who were examined for GRN and MAPT sequence variants and hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9ORF72. The potential pathogenicity of each identified variant was assessed (refer the “Methods” section), and each variant was ultimately categorized into one of five ACMG variant classifications (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign). Only variants classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic – collectively described as disease-associated variants in this study – were included in the final analyses (Figures S1 and S2). There was a total of 78 individuals at the academic center and 387 individuals at the commercial laboratory with disease-associated variants. On average, patients who carried these variants were around the age of 60 years at testing and consisted of relatively balanced proportions of males and females (Table 1). There were no significant differences in average age at testing between centers (P=0.17, two-tailed ANOVA).

Table 1.

Demographic characterization of patients with pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in FTLD-associated genes at UCSF and commercial clinical laboratory

| Patient demographics |

GRN |

MAPT |

C9orf72 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCSF | Clinical laboratory | UCSF | Clinical laboratory | UCSF | Clinical laboratory | |

| Agea (years) | 62.95±7.0 | 60.9±6.9 | 55.1±10.8 | 59.1±10.7 | 60.9±7.2 | 59.3±10.0 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 8 (40) | 9 (37.5) | 4 (44.4) | 9 (47.4) | 33 (67.3) | 170 (50.2) |

| Female | 12 (60) | 15 (62.5) | 5 (55.6) | 10 (52.6) | 16 (32.7) | 169 (49.8) |

| Total no. | 20 | 24 | 9 | 19 | 49 | 344b |

Notes: Age for the UCSF cohort was defined as age at the first visit. Age for Quest cohort is age when testing was performed.

Sex was unavailable for five patients in the commercial clinical laboratory cohort. in the GRN mutations in the UCSF cohort, 85% (n=17) of patients had autosomal dominant family history of dementia (at least one first-degree relative), 10% (n=2) had family history unknown, and 5% (n=1) were negative for a family history of dementia. in patients with pathogenic mutations in MAPT in the UCSF cohort, 88% (n=8) had an autosomal dominant family history of dementia (at least one first-degree relative) and 12% (n=1) had a negative family history. in patients with pathogenic C9orf72 expansions in the UCSF cohort, 51% (n=25) had an autosomal dominant family history of dementia (at least one first-degree relative), 33% (n=16) had a negative family history, and 14% (n=7) had an unknown family history. Family history data were not available for the commercial laboratory cohort.

Abbreviations: FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; UCSF, University of California, San Francisco.

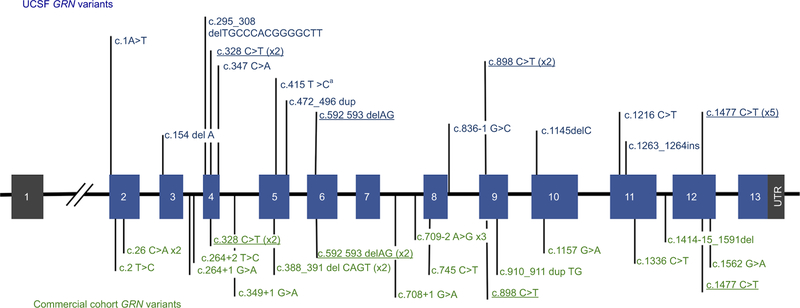

Hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9ORF72 were the most frequent cause of FTLD in both the UCSF and the commercial cohorts, while GRN and MAPT accounted for far fewer. In the UCSF cohort, hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9ORF72 were the most frequently encountered (63%, n=49), followed by disease-associated variants in GRN (26%, n=20) and MAPT (11%, n=9). C9ORF72 pathogenic expansions were also the most frequent FTLD-associated variants (89%, n=344) in the commercial laboratory, although they were more frequent than in the UCSF cohort. In contrast to the academic cohort, where variants were identified with a higher frequency in GRN vs MAPT, variants in GRN (6%, n=24) and MAPT (5%, n=19) were observed at nearly the same frequency in the commercial laboratory. There were no significant differences in ages of patients at testing based on the gene group when combining both cohorts (ANOVA, P=0.24) and no difference in testing age across cohorts. Disease-associated variants identified in GRN are plotted by exon in Figure 1. As expected for a gene in which loss of function is a mechanism for disease, there do not appear to be hotspots of disease-associated variants but rather an even distribution across the entire gene.

Figure 1.

GRN variants in cohorts from UCSF and a Commercial Clinical Laboratory.

Notes: UCSF variants appear in blue text above the gene, while commercial clinical laboratory variants appear in green below the gene. Variants that appeared in both cohorts are indicated in underlined, bold typeface. GRN is located on chromosome 17q21 and consists of 13 exons encoding a highly glycosylated 593-amino acid precursor protein with a predicted molecular mass of 63.5 kDa.12 aAll variants were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic, except for c.415T>C, which is a missense variant classified as a risk allele.

Abbreviation: UCSF, University of California, San Francisco.

In total, 37 unique, disease-associated variants were identified in GRN and MAPT across both cohorts (Tables S2 and S3. The majority of unique variants were identified in only one individual, highlighting the rarity of many disease-associated GRN and MAPT variants, but some were identified in multiple unrelated patients. Comparing the spectrum of variants identified in each cohort, only six disease-associated variants in GRN and MAPT were found in both cohorts (Table S4 and Figure 1), while the other 83% were found in only one cohort or the other. In GRN, the shared variants were c.328C>T (p.Arg110*), c.592_593delAG (p.Arg198Glyfs*19), c.898C>T (p.Gln300*), c.1477C>T (p.Arg493*), and in MAPT, these were c.915+16C>T and c.902C>T (p.Pro301Leu). The wealth of published literature about these variants supports the fact that they are common disease-associated alleles shared by many unrelated individuals. Of all the variants in both genes, c.902C>T (p.Pro301Leu) in MAPT was the most common, observed in 14 probands (three from UCSF and eleven from the commercial laboratory). Half of the UCSF GRN-positive individuals carried a shared variant, while only one-quarter (24%) of the commercial clinical laboratory GRN-positive cohort carried a shared variant (Table S2). This suggests that the commercial cohort may be more ethnically and/or geographically diverse than the academic cohort and highlights the important role of commercial laboratories in identifying extremely rare disease-associated alleles.

Disease-associated variants were assessed for their allele frequency in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) dataset, a large, multiethnic, population that is not enriched for dementia patients, making it a suitable control population for this analysis (Tables S3 and S4).13 The majority of disease-associated variants from both cohorts occurred a total of zero, one, or two times in the ExAC database. Consistent with this pattern were two novel GRN variants, identified in the UCSF cohort, that were not found in the ExAC general population: p.Pro166Leufs*2 (Patient 1) and p.Gln406* (Patient 2). Because both variants are predicted to cause early protein termination, and they were identified in clinically characterized patients in the UCSF cohort (detailed in the “Case Vignettes of patients with GRN variants” section) and were not found in the ExAC general population, they can be classified as pathogenic based on the commercial clinical laboratory variant scoring system and ACMG guidelines. The absence of these two variants from the commercial cohort, including 1,036 total patients screened for GRN variants, as well as the ExAC general population suggests that these variants are extremely rare.

We also observed one occurrence of p.Cys139Arg (c.415T>C) in GRN in a patient from UCSF. This patient developed subtle behavioral changes during his early 60s and developed word-finding difficulties during his mid-60s. Family history revealed a maternal aunt with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Clinical diagnosis was semantic variant primary progressive aphasia, with right temporal behavioral features. Profound focal atrophy in bilateral anterior and mesial temporal lobes was noted, more prominent on the left, as well as left insula and inferior frontal gyrus atrophy (Figure 2A). At autopsy, he was found to have FTLD-TDP type C pathology. The p.Cys139Arg missense variant is predicted to be damaging at the amino acid level, which is supported by functional data suggesting the variant interferes with cleavage of progranulin into granulin14 and may reduce neurite outgrowth.15 However, p.Cys139Arg was observed 22 times in the ExAC database, which does not fit the pattern observed for the disease-associated variants identified in these cohorts, and suggests that this variant may not cause FTLD with Mendelian inheritance. Family studies support this, describing variable segregation of the variant with disease.16 Nevertheless, enrichment of the variant in characterized patients compared to ethnically matched controls suggests that the variant may be a rare risk factor or reduced penetrance disease-causing variant.17

Figure 2.

Neuroimaging from select GRN variant cases.

Notes: Structural brain MRI at patients’ first presentation to UCSF. GRN variant and CDR total score (with larger scores demonstrating worse clinical disease severity) at the time of scan are provided below each of three patients’ representative structural brain images in coronal (A and B) or axial (C) orientation. images are in radiological orientation with the right side of the brain presented as the left side of the image. All patients showed asymmetric atrophy, predominantly in the frontal and temporal lobes, which is typical of GRN mutation carriers.18

Abbreviations: CDR, clinical dementia rating; R, right; L, left.

Case vignettes of patients with GRN variants

Both patients were white, non-Hispanic individuals

Patient 1: novel pathogenic GRN variant, p.Pro166Leufs*2

Patient 1 was a woman who showed subtle behavioral changes, including loss of empathy emerging during her late 40s. She developed empty speech and had difficulty communicating in her early 60s. She then developed apathy and started hoarding. Around her mid-60s, she developed a strong interest in art and began to chant religious phrases repetitively. She grew more disinhibited and paced from room to room in a stereotyped sequence. There was no known family history of neurodegenerative disease. Clinical diagnosis was behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD) with right temporal behavioral features. Structural MRI revealed prominent atrophy in the right anterior and mesial temporal cortex, insula (right greater than left), and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Figure 2B). Sequencing revealed p.Pro166Leufs*2 in GRN, a previously unreported mutation. Although she ultimately developed bvFTD, one of the major clinical diagnoses of GRN carriers, her protracted disease duration of >18 years was atypical.

Patient 2: novel pathogenic GRN variant, p.Gln406*

Patient 2, a woman in her early 50s, had a one-year history of loss of interest in her work and developed shopping compulsions 6 months prior to presentation. She then began to miss appointments and grew confused about their timing and had trouble with calculations. She developed very subtle signs of disinhibition and utilization behavior. One of her parents had a clinical diagnosis of AD and an autopsy diagnosis of FTLD (subtype unknown), with symptoms starting in the early 60s. Additionally, an aunt had suspected AD with onset during her mid-50s. Structural MRI of the patient showed symmetric atrophy in bilateral insular, medial frontal, dorsolateral prefrontal, and bilateral parietal cortices (Figure 2C).

Discussion

We conducted a detailed survey of disease-associated variants in GRN, MAPT, and pathogenic expansions in C9ORF72; the three genes most commonly associated with FTLD, among individuals tested at a specialty academic clinic and a commercial clinical laboratory, and the frequencies of genetic variants were ranked similarly between cohorts: C9ORF72 expansions were the most common pathogenic variants, and MAPT variants were the least common in both groups. This is in agreement with previous multicenter surveys of FTLD disease-associated variants.19 Additionally, we identified two novel pathogenic variants in GRN in patients from UCSF. Clinical and neuroimaging information for both of these variants supports their association with FTLD. Identification of two previously unidentified variants in a survey of >4,000 total individuals highlights the possibility that pathogenic variants can be rare and potentially even family specific. This is the first study to our knowledge that uses academic center and national commercial laboratory genetic data synergistically to derive estimates of genetic contributors to FTLD.

Although the frequencies of variants in the three genes were similarly ranked across both centers, we noted differences in the relative proportions of variants in each gene based on whether they were identified through the academic center or the commercial laboratory. The differences in the frequency distribution and type of MAPT, GRN, and C9ORF72 disease-associated variants between the two cohorts suggest differences in underlying populations. C9ORF72 has been widely reported as the most common genetic contributor to familial FTLD as well as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), so the fact that pathogenic expansion of this gene was the most common variant in both cohorts is not surprising. However, the proportion of C9ORF72 carriers in the commercial laboratory cohort was much larger than that of the academic center (89% vs 63%), despite the fact that C9ORF72 testing was not implemented by the commercial laboratory in the first study year. This could be due to the limitations imposed by surveying genetic variants by test code, which resulted in potential inclusion of both probands and family members representing the clinical spectrum of FTD and ALS. This difference suggests ascertainment bias that might affect the distribution of underlying gene-associated pathology but does not change the overall conclusion: C9ORF72 is the most frequent cause of disease in both cohorts.

Utilizing the combined power of the academic dataset and the commercial laboratory dataset, patterns were identified among the disease-associated variants that ultimately improved our ability to interpret variants of less certain significance. For example, disease-associated variants from both cohorts were assessed for their allele frequency in ExAC. On average, disease-associated variants only occurred zero, one, or two times in the ExAC database, consistent with the estimated worldwide prevalence of FTD (Tables S3 and S4).1,19 Based on this pattern, we were able to confirm the pathogenicity of two novel GRN variants identified in the UCSF cohort. Their absence from the ExAC database, combined with their mutation type (likely gene disrupting), and their occurrence in patients with clinically diagnosed FTD (including one patient with prolonged disease duration), determined their classification as pathogenic variants. On the other hand, a missense GRN variant that was detected in a UCSF patient with clinically diagnosed FTD was found a total of 22 times in the ExAC database. This is outside the typical frequency for disease-associated variants in the ExAC database and supports previous literature proposing p.Cys139Arg as a rare risk allele rather than pathogenic variant. Together, these clinical pictures highlight the wide range of disease duration, syndromic presentation, and variable penetrance that can occur with disease-associated GRN variants.

It is possible that because UCSF research patient genetic data are occasionally confirmed with CLIA laboratory follow-up, a small number of patients were represented in both cohorts. However, eliminating family test codes likely reduced the majority of potential overlap, and given the magnitude of samples screened by the commercial laboratory and the minimal overlap observed between cohorts, it is unlikely that this “double testing” introduced a substantial bias to the study. Additionally, the only variants identified in both cohorts are well-published, common pathogenic variants, increasing the likelihood of multiple distinct observations (rather than repeated testing of the same individual in both cohorts). Furthermore, subtle differences in sequencing methodology may have introduced noise into our comparison of the two cohorts.

This study benefits from several strengths. First, detailed clinical data from the academic cohort allowed us to assess variants of unknown pathogenicity for their role in disease risk. Second, combining the data from two contrasting cohorts allowed us to find patterns (e.g., variant frequency in the population, variant type, and location) among a large set of disease-associated variants. Knowing the characteristic features of disease-associated variants in these genes improves our ability to assess variants of unknown significance, driving down the number of these ambiguous results reported out to patients and making genetic testing more conclusive for a larger percentage of patients. This study highlights the need for updated reporting of known variants and variant classifications in existing open access databases to complement the efforts of clinical entities in reclassification of variants as new evidence becomes available.

The results of this analysis have several implications for patient management. The occurrence of disease-associated variants in all three major FTD genes supports the use of a panel approach for initial genetic screening of patients. That said, the large percentage of C9ORF72 repeat expansions in both cohorts could also support a testing strategy in which the C9ORF72 gene is screened first, particularly if the patient’s family history is significant for ALS and FTD. If genetic variants are identified, it is imperative to consider their frequency in a multiethnic control population while interpreting their clinical significance. Large, multiethnic population databases have demonstrated the potential for drastic differences in variant frequency across ethnic groups, with some variants being unique to a single subpopulation. Thus, it is best to compare the frequency of a variant in patients with ethnically matched control populations in order to achieve the most accurate classification of clinical significance.

Conclusion

In summary, we have shown that surveys of disease-associated variants, particularly for rare variants, differ by type of testing center but largely agree with regards to overall ranking of gene contributions to disease. In this study, we found that specific, rare alleles are often unique to a given cohort, whether through chance or ascertainment bias. This finding emphasizes the need to perform thorough genetic characterization of clinical cohorts and highlights the importance of developing therapeutic interventions that will be amenable to a broad spectrum of underlying pathogenic causes that all affect a specific gene or protein target. It also highlights the importance of academic-industry research collaborations and data sharing that enhances current knowledge of the scope and frequency of pathogenic variants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Primary analysis was supported by the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation 2012-A-015-FEL and 2016-A-005-SUP (JSY), AFTD Susan Marcus Memorial Fund Clinical Research Grant (JSY), NIA K01 AG049152 (JSY), and Quest Diagnostics, Inc. Additional support, including for assembly and screening of cohorts, was provided by NIA P01 AG1972403 (BLM), NIA P50 AG023501 (BLM), the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation (GC), the Hillblom Aging Network, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. The authors would like to thank Michael Geschwind, Howie Rosen, and Adam Boxer for their contributions to this work. The authors would also like to thank the ExAC and the groups that provided exome variant data for comparison. A full list of contributing groups can be found at http://exac.broadinstitute.org/about.

Disclosure

Alison R Bright is an employee of Quest Diagnostics. Suzee E Lee receives support from National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (NIH/NIA) and the Tau Consortium. Izabela D Karbassi is an employee of Quest Diagnostics. Marc A Meservey is an employee of Quest Diagnostics. Khalida Liaquat is an employee of Quest Diagnostics. Matthew C Gallen is an employee of Quest Diagnostics. Carol C Hoffman is an Quest Diagnostics. Meagan R Krasner is an employee of Quest Diagnostics. Whitney Dodge is an employee of Quest Diagnostics. Katherine P Rankin receives research/grant support from the NIH/NIA and the Tau Consortium. Giovanni Coppola receives research/grant support from the NIH (RC1 AG035610, P30 NS062691), John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Bruce L Miller receives grant support from the NIH/NIA and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as grants for the Memory and Aging Center. He also serves as Medical Director for the John Douglas French Foundation, Scientific Director for the Tau Consortium, Director/Medical Advisory Board of the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation, and Scientific Advisory Board Member for the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Center and its subunit the Biomedical Research Unit in Dementia (UK). Joseph J Higgins is a former employee of Quest Diagnostics.

Footnotes

The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2002;58(11):1615–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bang J, Spina S, Miller BL, Dementia F. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet 2015;386(10004):1672–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Zee J, van Broeckhoven C, In D. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration—building on breakthroughs. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10(2): 70–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, et al. Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 1998;393(6686):702–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature 2006;442(7105):916–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dejesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 2011;72(2):245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen-Plotkin AS, Martinez-Lage M, Sleiman PM, et al. Genetic and clinical features of progranulin-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Arch Neurol 2011;68(4):488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghetti B, Oblak AL, Boeve BF, Johnson KA, Dickerson BC, Goedert M. Invited review: Frontotemporal dementia caused by microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) mutations: a chameleon for neuropathology and neuroimaging. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2015;41(1):24–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gass J, Cannon A, Mackenzie IR, et al. Mutations in progranulin are a major cause of ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 2006;15(20):2988–3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karbassi I, Maston GA, Love A, et al. A Standardized DNA Variant Scoring System for Pathogenicity Assessments in Mendelian Disorders. Hum Mutat 2016;37(1):127–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17(5):405–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman A, Belcourt D, Bennett H, Lazure C, Solomon S. Granulins, a novel class of peptide from leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1990;173(3):1161–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536(7616):285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, van Damme P, Cruchaga C, et al. Pathogenic cysteine mutations affect progranulin function and production of mature granulins. J Neurochem 2010;112(5):1305–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gass J, Lee WC, Cook C, et al. Progranulin regulates neuronal outgrowth independent of sortilin. Mol Neurodegener 2012;7(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonell A, Gil S, Sánchez-Valle R, et al. Serum Progranulin Levels in Patients with Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Alzheimer’s Disease: Detection of GRN Mutations in a Spanish Cohort. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2012;31(3):581–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Engelborghs S, et al. Genetic variability in progranulin contributes to risk for clinically diagnosed Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2008;71(9):656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Boeve BF, et al. Neuroimaging signatures of frontotemporal dementia genetics: C9ORF72, tau, progranulin and sporadics. Brain 2012;135(Pt 3):794–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onyike CU, Diehl-Schmid J. The epidemiology of frontotemporal dementia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2013;25(2):130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.