Abstract

Background

Patients prefer oral to intravenous (IV) palliative chemotherapy, provided that oral therapy is not less effective. We compared the efficacy and safety of oral and IV fluoropyrimidines for treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC).

Objectives

To compare the effects of oral and IV fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy in patients treated with curative or palliative intent for CRC.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 5), along with OVID MEDLINE, OVID Embase, and Web of Science databases, in June 2016. We also searched five clinical trials registers, several conference proceedings, and reference lists from study reports and systematic reviews. We contacted pharmaceutical companies to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing oral and IV fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy in patients treated with curative or palliative intent for CRC.

Data collection and analysis

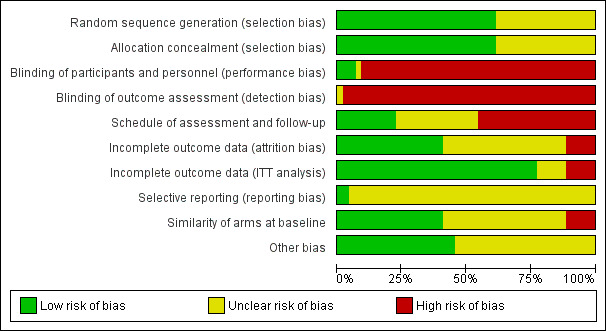

Three review authors extracted data and assessed risk of bias independently. We assessed the seven domains in the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool and three additional domains: schedules of outcome assessment and/or follow‐up; use of intention‐to‐treat analysis; and baseline comparability of treatment arms.

Main results

We included nine RCTs (total of 10,918 participants) that examined treatment with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy. We included 35 RCTs (total of 12,592 participants) that examined treatment with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with chemotherapy (31 first‐line studies, two second‐line studies, and two studies of first‐ or second‐line chemotherapy). All studies included male and female participants, and no studies included participants younger than 18 years of age.

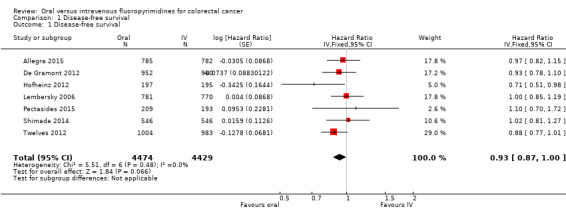

Patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy

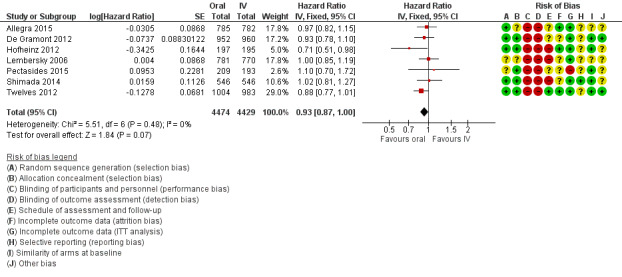

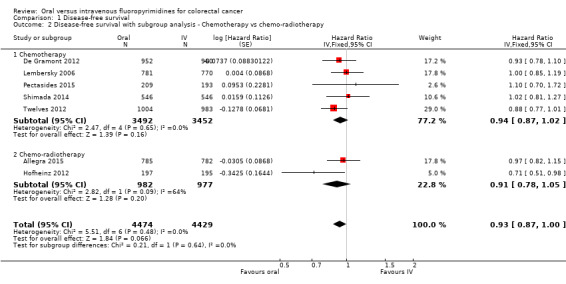

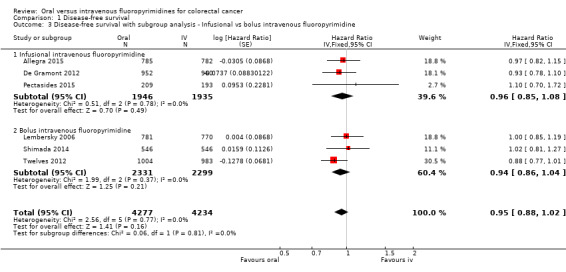

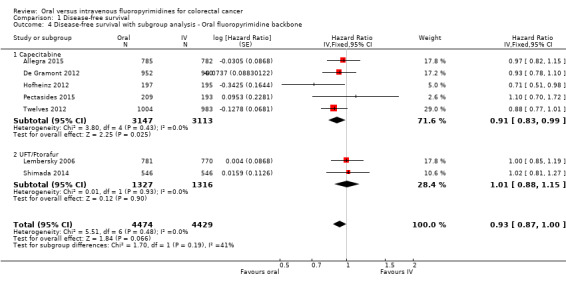

• Disease‐free survival (DFS): DFS did not differ between participants treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines (hazard ratio (HR) 0.93, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87 to 1.00; seven studies, 8903 participants; moderate‐quality evidence).

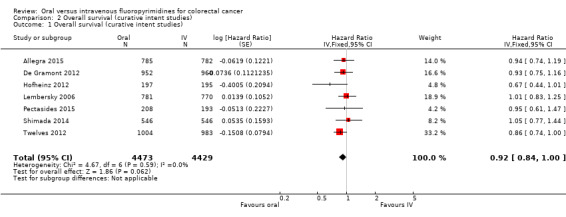

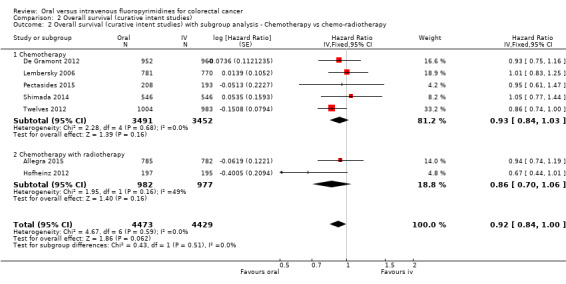

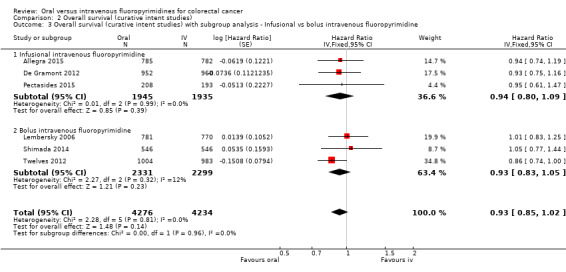

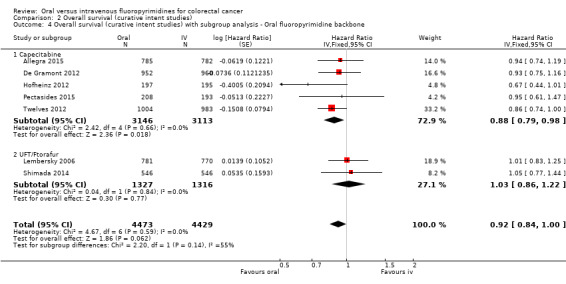

• Overall survival (OS): OS did not differ between participants treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.00; seven studies, 8902 participants analysed; high‐quality evidence).

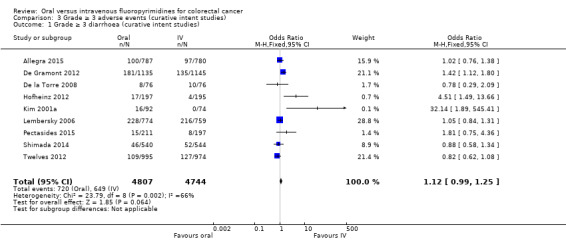

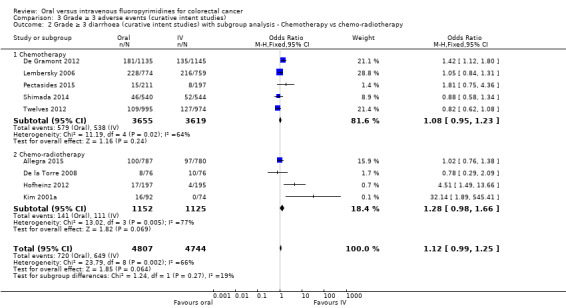

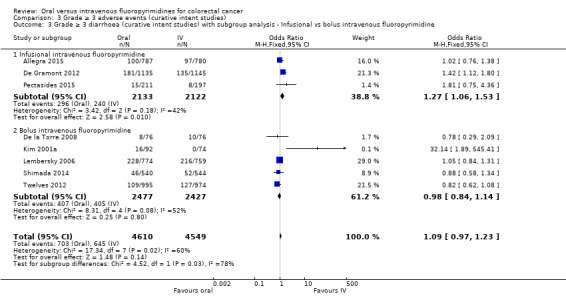

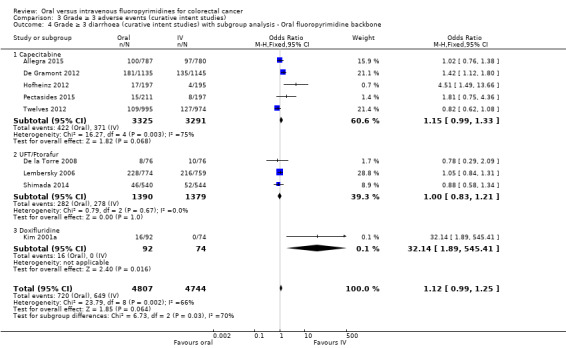

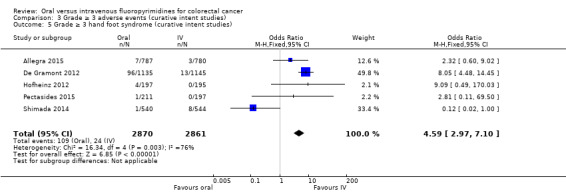

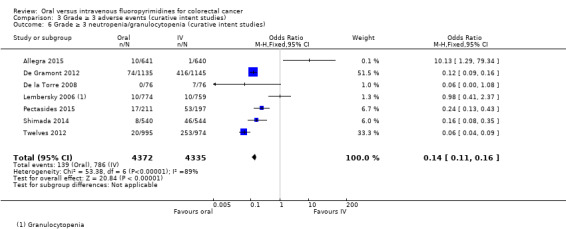

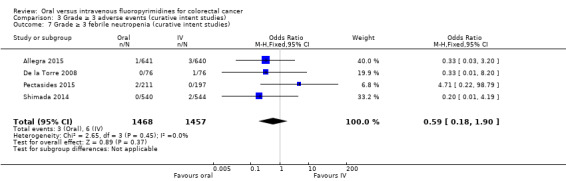

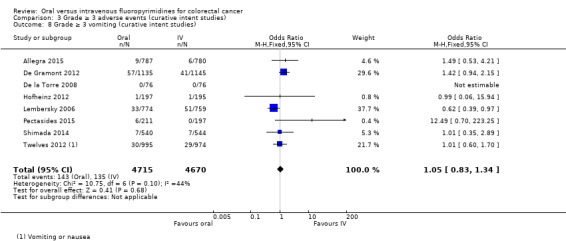

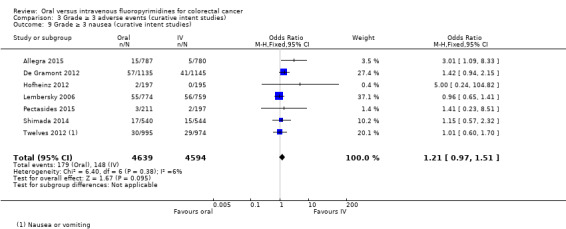

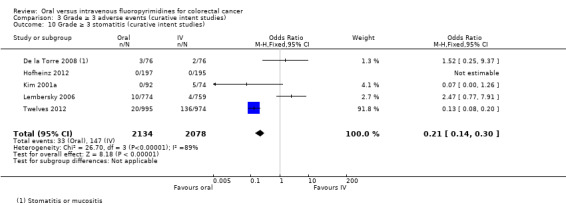

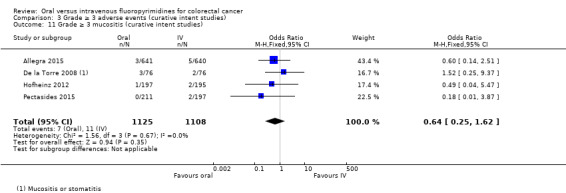

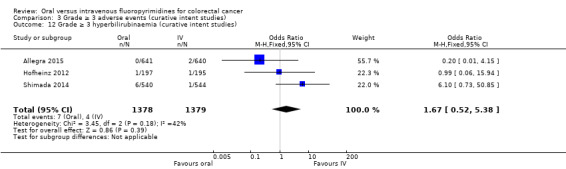

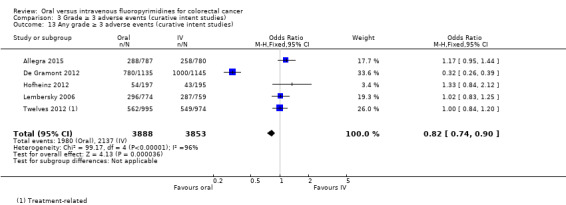

• Grade ≥ 3 adverse events (AEs): Participants treated with oral fluoropyrimidines experienced less grade ≥ 3 neutropenia/granulocytopenia (odds ratio (OR) 0.14, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.16; seven studies, 8087 participants; moderate‐quality evidence), stomatitis (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.30; five studies, 4212 participants; low‐quality evidence), and any grade ≥ 3 AEs (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.90; five studies, 7741 participants; low‐quality evidence). There was more grade ≥ 3 hand foot syndrome (OR 4.59, 95% CI 2.97 to 7.10; five studies, 5731 participants; low‐quality evidence) in patients treated with oral fluoropyrimidines. There were no differences between participants treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines in occurrence of grade ≥ 3 diarrhoea (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.25; nine studies, 9551 participants; very low‐quality evidence), febrile neutropenia (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.90; four studies, 2925 participants; low‐quality evidence), vomiting (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.34; eight studies, 9385 participants; low‐quality evidence), nausea (OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.51; seven studies, 9233 participants; low‐quality evidence), mucositis (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.62; four studies, 2233 participants; very low‐quality evidence), and hyperbilirubinaemia (OR 1.67, 95% CI 0.52 to 5.38; three studies, 2757 participants; very low‐quality evidence).

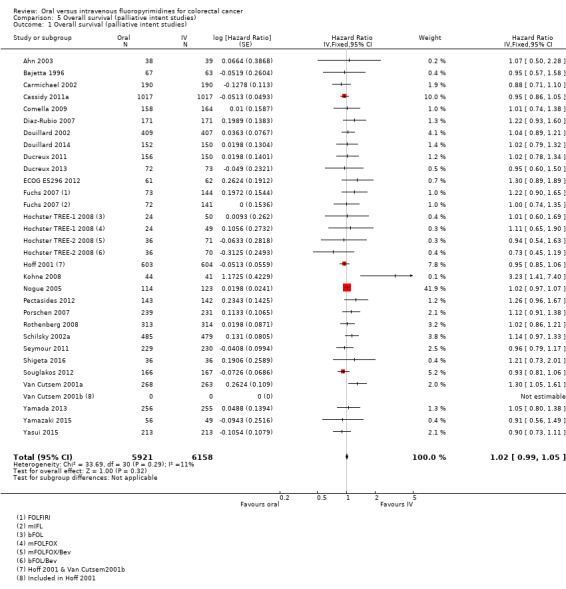

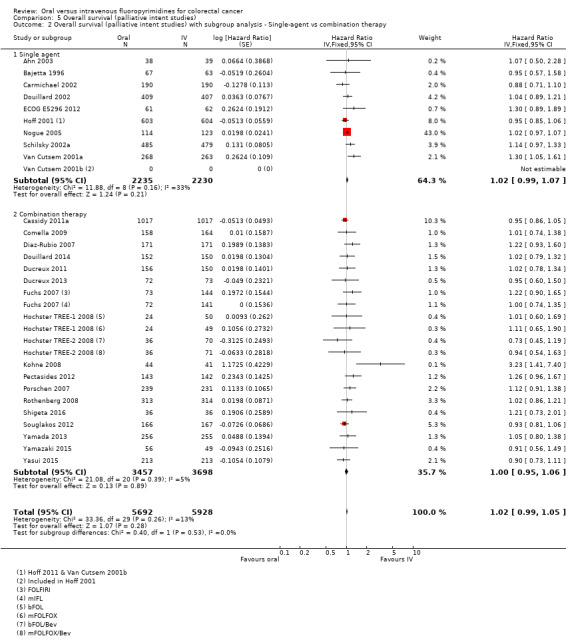

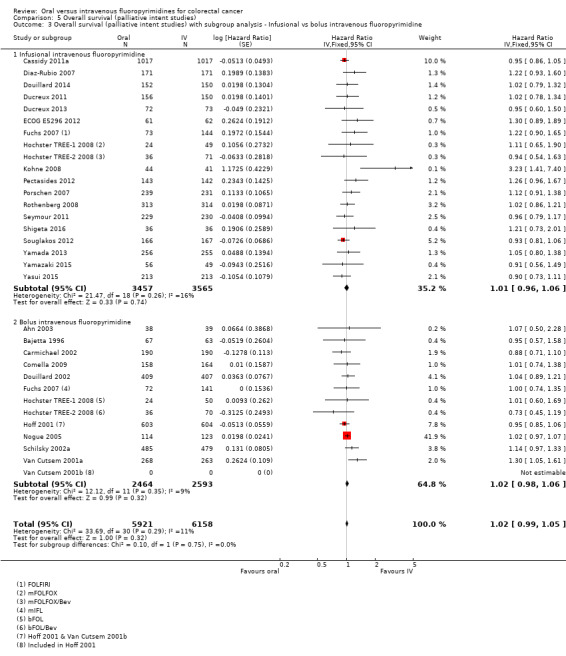

Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with chemotherapy

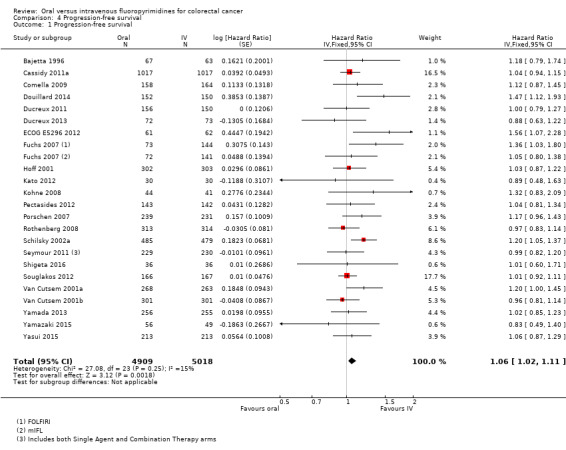

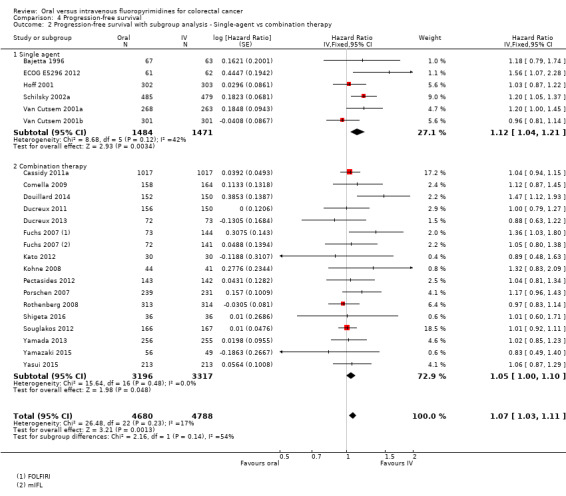

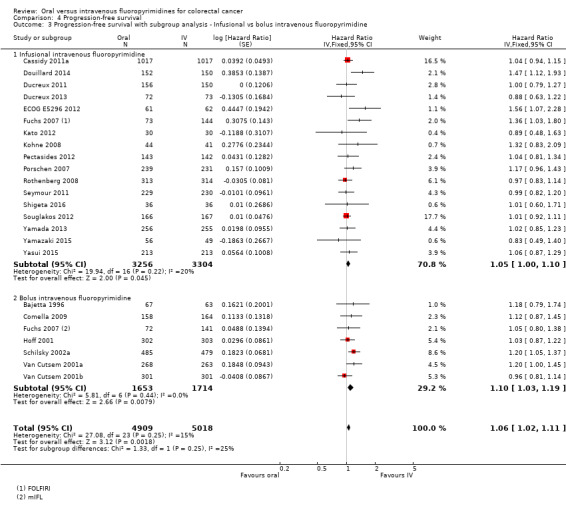

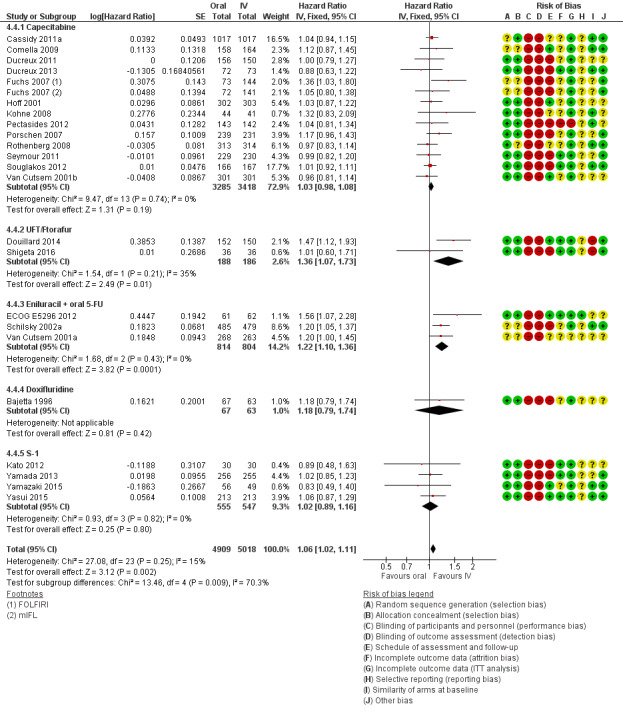

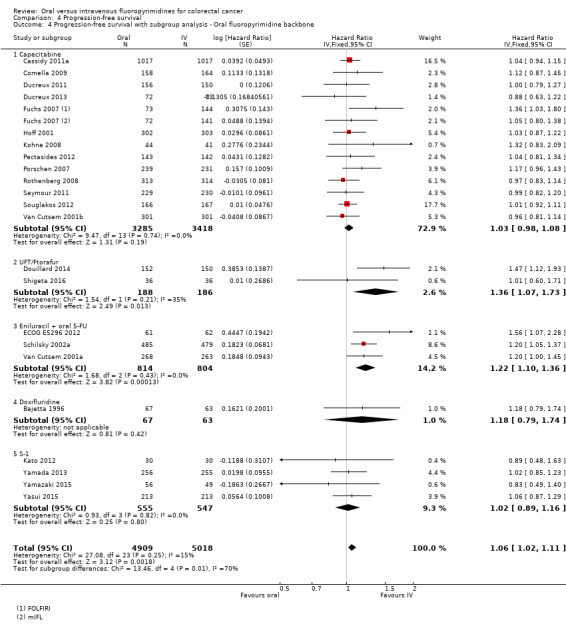

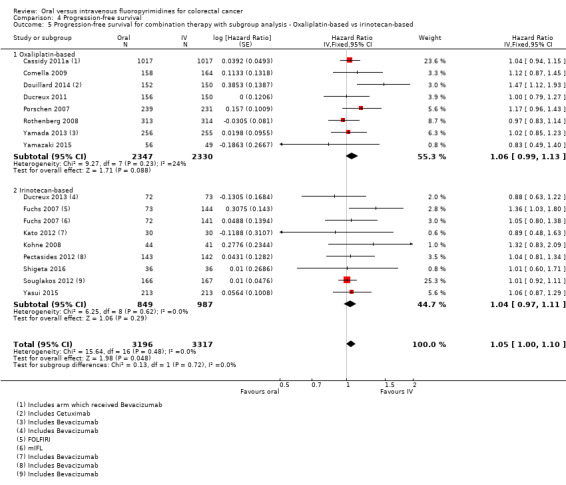

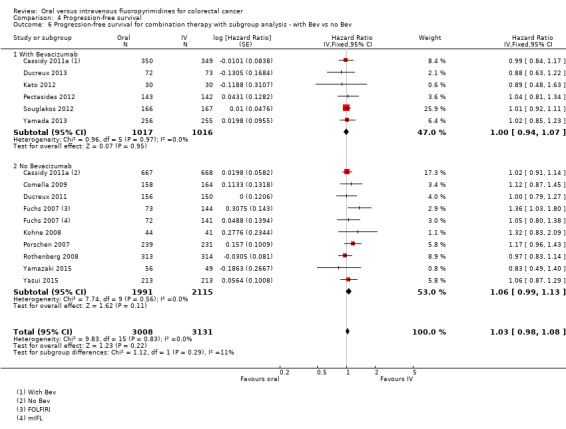

• Progression‐free survival (PFS): Overall, PFS was inferior in participants treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines (HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.11; 23 studies, 9927 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). Whilst PFS was worse in participants treated with oral compared with IV fluoropyrimidines when UFT/Ftorafur or eniluracil with oral 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) was used, PFS did not differ between individuals treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines when capecitabine, doxifluridine, or S‐1 was used.

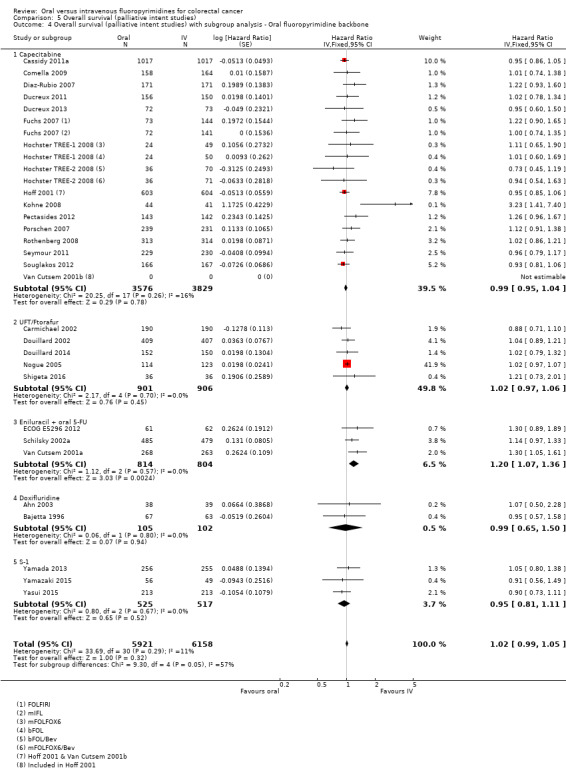

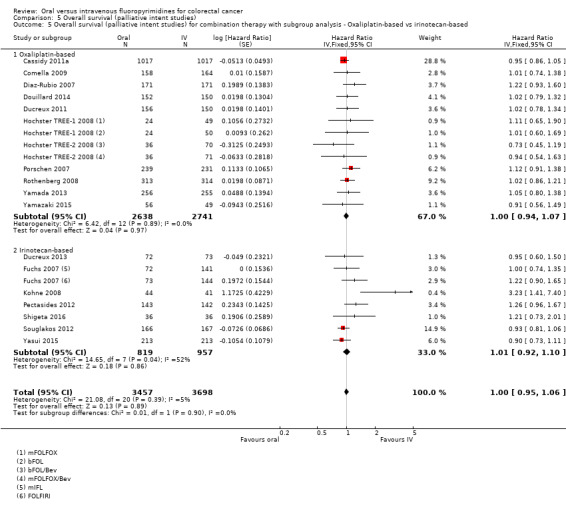

• OS: Overall, OS did not differ between participants treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.05; 29 studies, 12,079 participants; high‐quality evidence). OS was inferior in participants treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines when eniluracil with oral 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) was used.

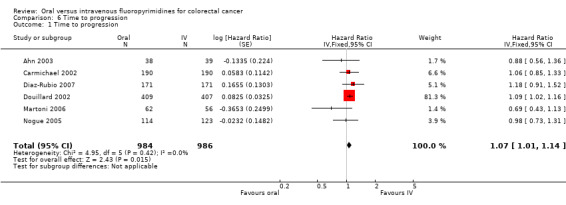

• Time to progression (TTP): TTP was inferior in participants treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines (HR 1.07, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.14; six studies, 1970 participants; moderate‐quality evidence).

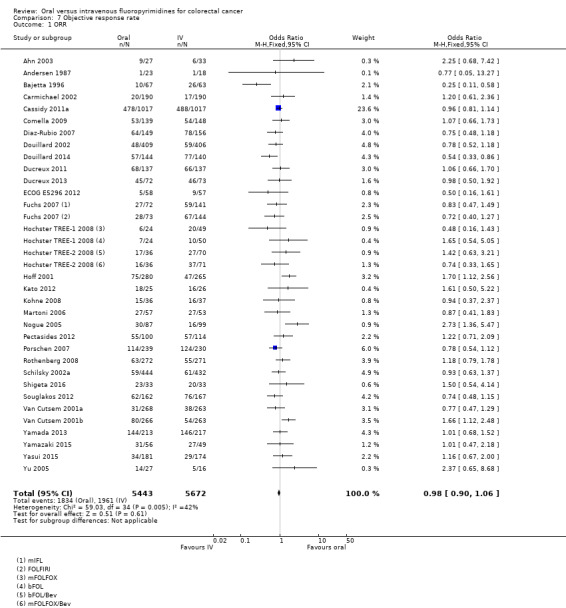

• Objective response rate (ORR): ORR did not differ between participants treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.06; 32 studies, 11,115 participants; moderate‐quality evidence).

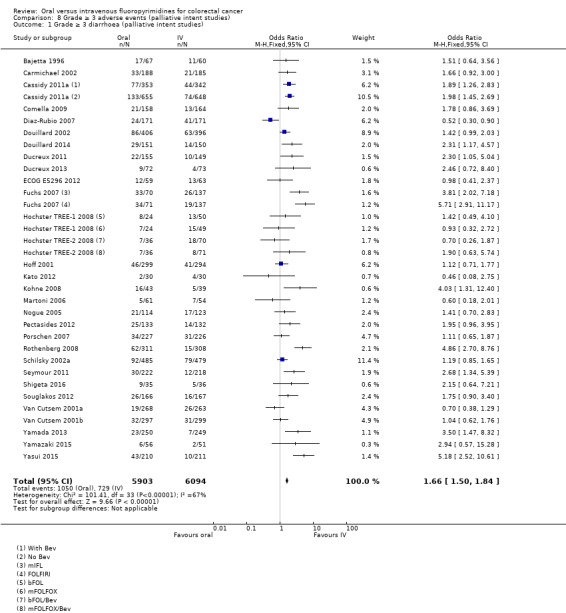

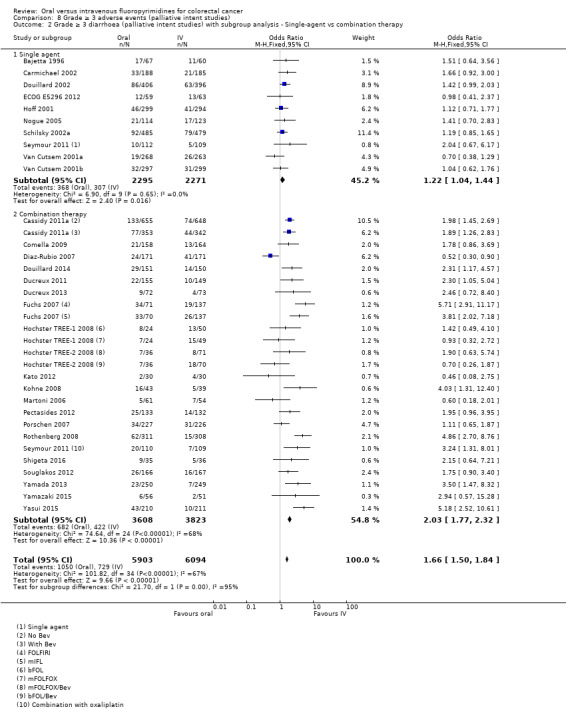

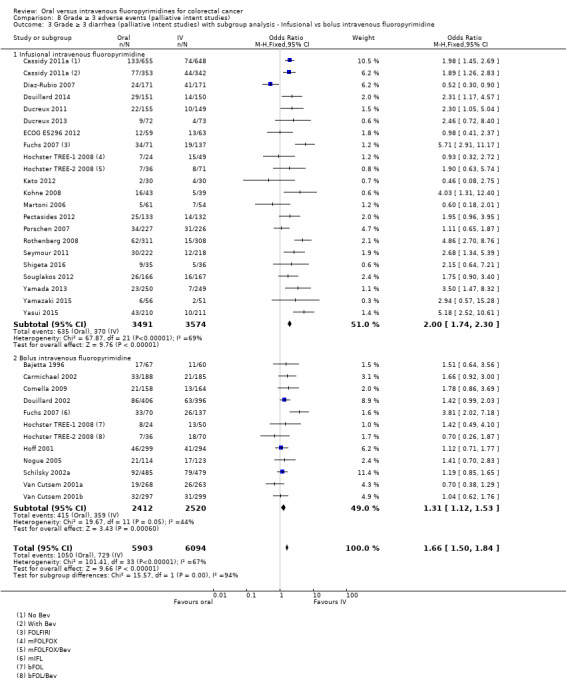

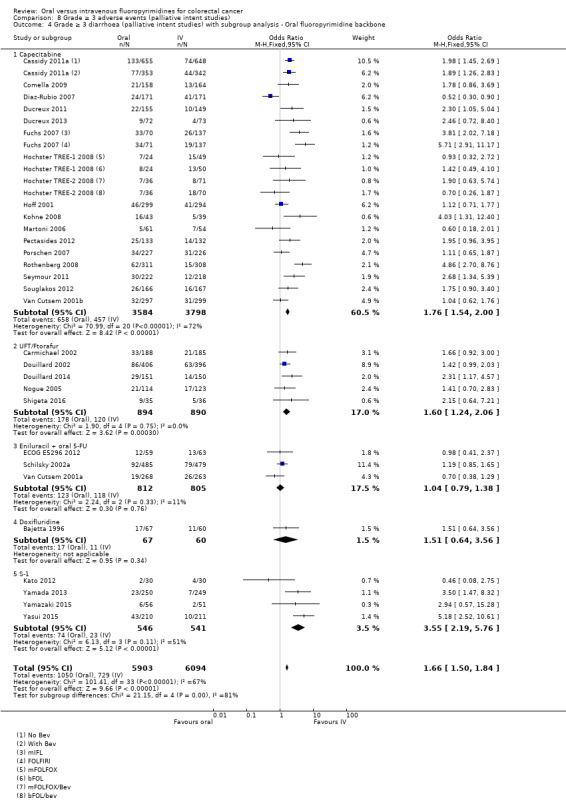

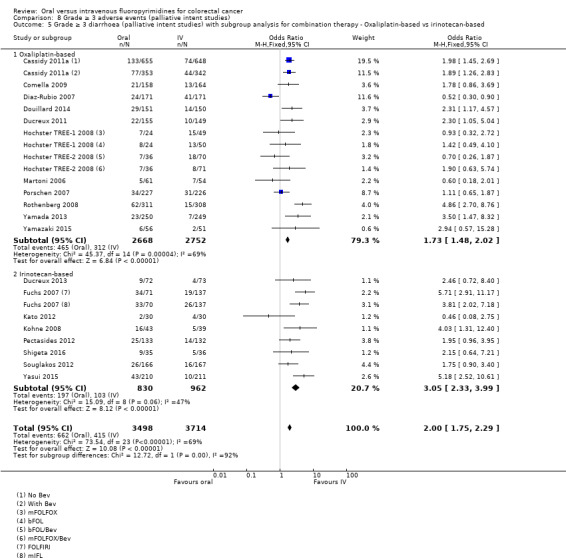

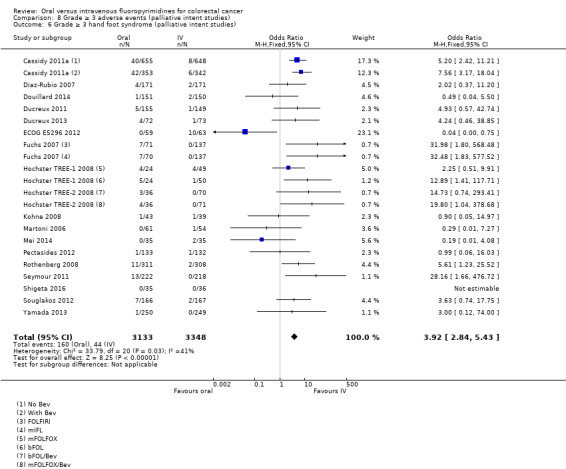

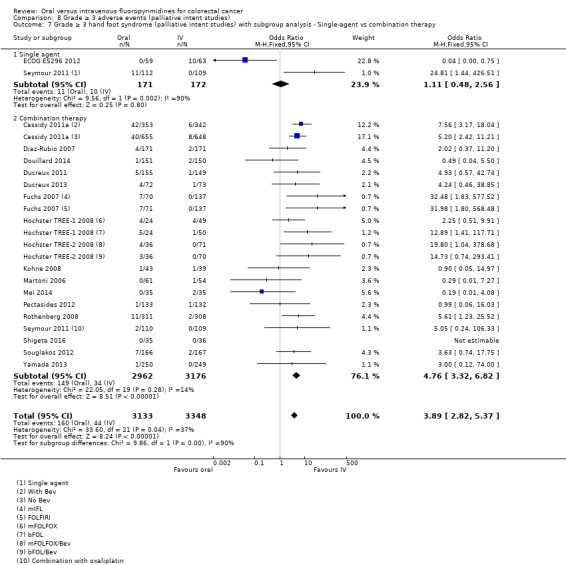

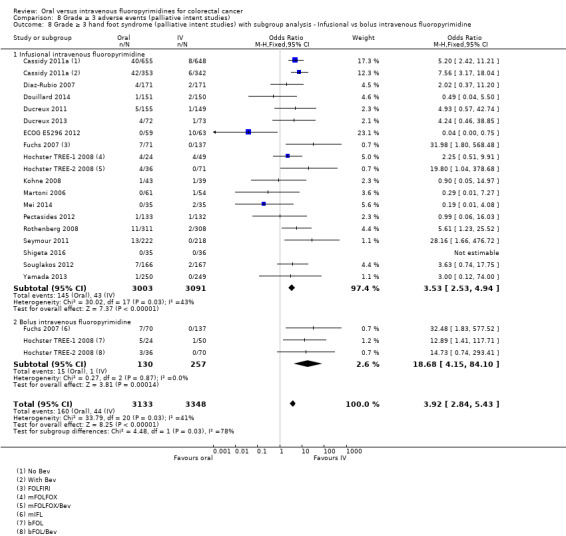

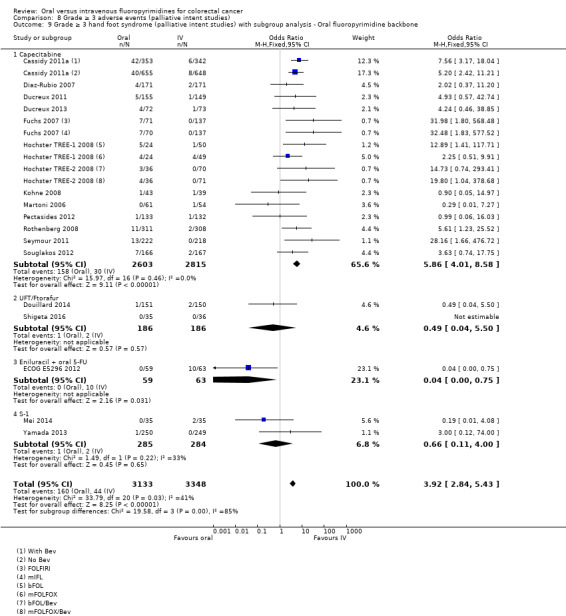

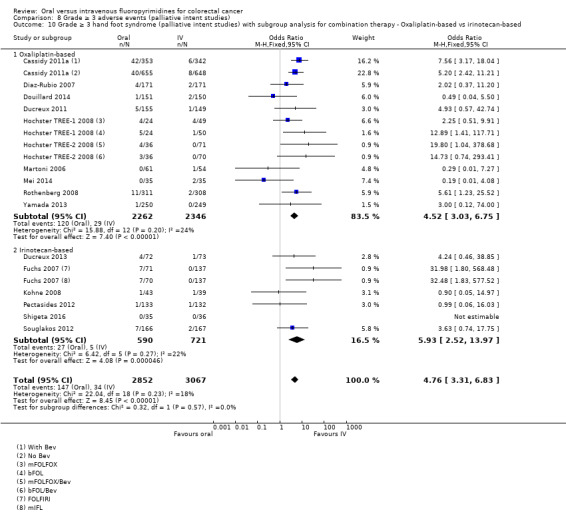

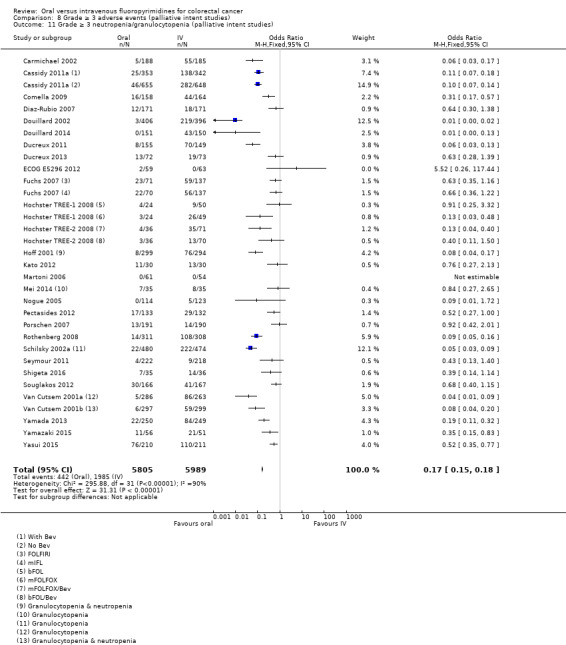

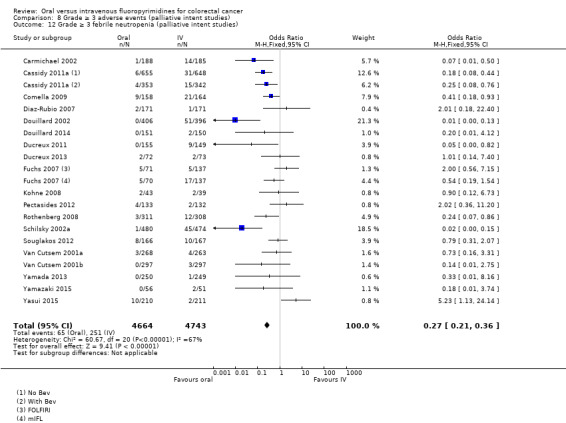

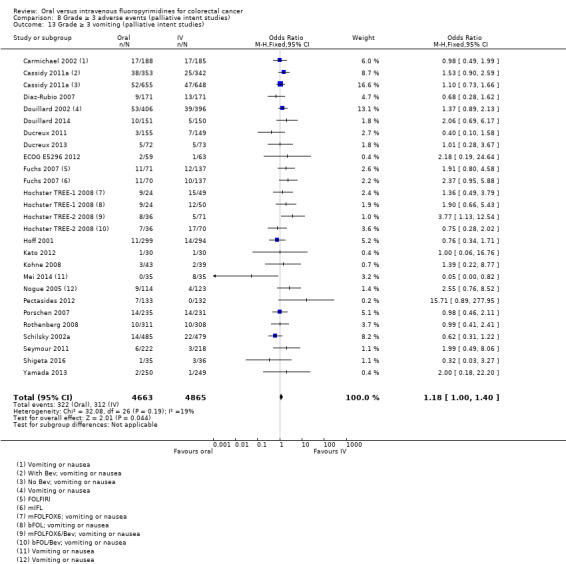

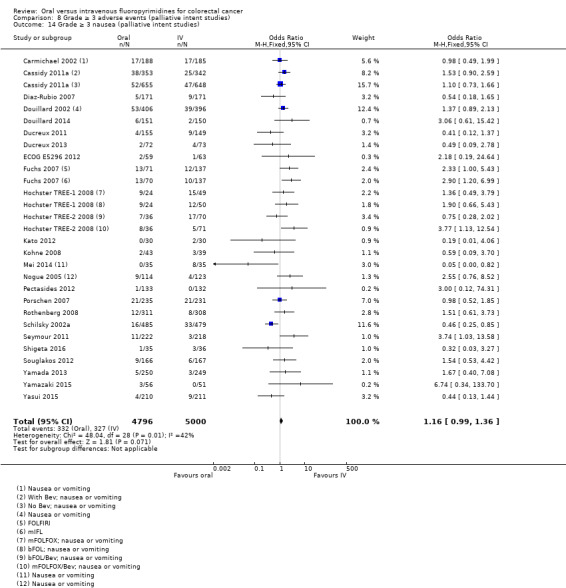

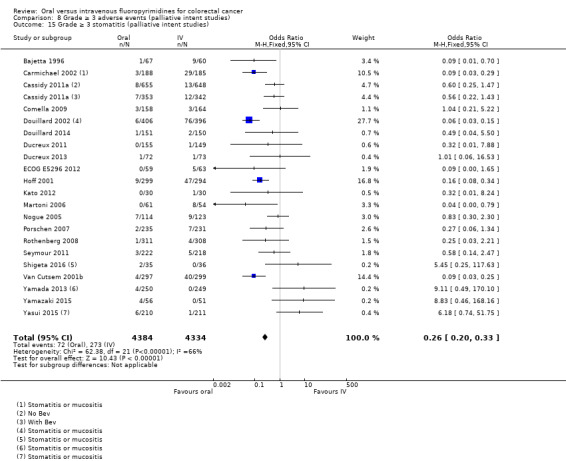

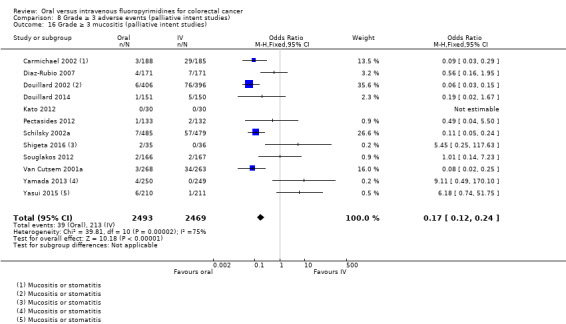

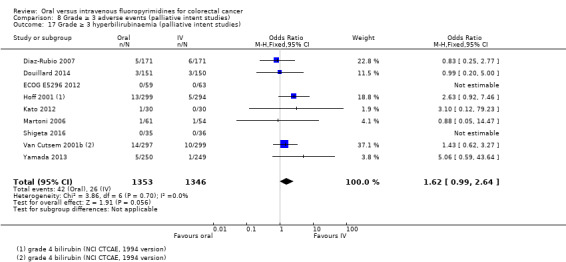

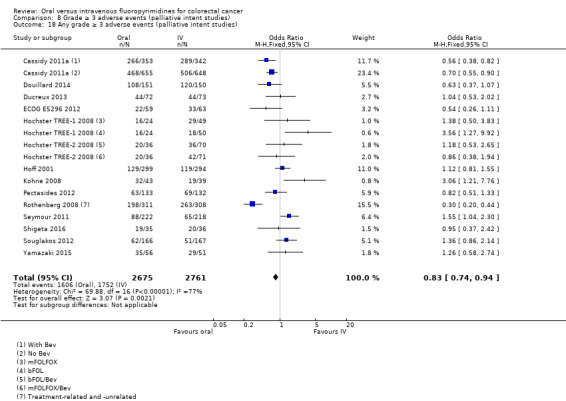

• Grade ≥ 3 AEs: Participants treated with oral fluoropyrimidines experienced less grade ≥ 3 neutropenia/granulocytopenia (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.18; 29 studies, 11,794 participants; low‐quality evidence), febrile neutropenia (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.36; 19 studies, 9407 participants; moderate‐quality evidence), stomatitis (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.33; 21 studies, 8718 participants; low‐quality evidence), mucositis (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.24; 12 studies, 4962 participants; low‐quality evidence), and any grade ≥ 3 AEs (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.94; 14 studies, 5436 participants; low‐quality evidence). There was more grade ≥ 3 diarrhoea (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.50 to 1.84; 30 studies, 11,997 participants; low‐quality evidence) and hand foot syndrome (OR 3.92, 95% CI 2.84 to 5.43; 18 studies, 6481 participants; moderate‐quality evidence) in the oral fluoropyrimidine arm. There were no differences between oral and IV fluoropyrimidine arms in terms of grade ≥ 3 vomiting (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.40; 23 studies, 9528 participants; low‐quality evidence), nausea (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.36; 25 studies, 9796 participants; low‐quality evidence), and hyperbilirubinaemia (OR 1.62, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.64; nine studies, 2699 participants; low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Results of this review should provide confidence that treatment for CRC with most of the oral fluoropyrimidines commonly used in current clinical practice is similarly efficacious to treatment with IV fluoropyrimidines. Treatment with eniluracil with oral 5‐FU was associated with inferior PFS and OS among participants treated with palliative intent for CRC, and eniluracil is no longer being developed. Oral and IV fluoropyrimidines have different patterns of side effects; future research may focus on determining the basis for these differences.

Plain language summary

Oral versus intravenous chemotherapy for colorectal cancer

Background

Intravenous (IV) fluoropyrimidines are an essential part of chemotherapy treatment for colorectal cancer (CRC). Patients prefer tablets as long as they work as well and are as safe as IV treatment, because they are easier to take and are more convenient.

Review question

We compared the effects of oral and IV fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy in patients with CRC who were treated with the aim of cure, or who were treated with palliative chemotherapy because the cancer could not be removed by surgery or was metastatic (it had spread from the place where it originated to other places in the body).

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to June 2016. We identified 44 randomised controlled trials involving 23,150 patients which compared oral and IV fluoropyrimidines. All studies included both male and female patients, and no studies included individuals younger than 18 years of age.

Key results

Among patients with CRC who were treated with the aim of cure, disease‐free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) did not differ between those who received oral versus IV treatment. In terms of severe side effects, patients who received oral treatment and those who received IV treatment had a similar risk of diarrhoea. Patients who received oral treatment were more likely to develop hand and foot rash but were less likely to have lowered white cell counts (neutropenia) than patients who received IV treatment.

In patients with CRC whose cancer was treated with palliative chemotherapy, overall, those who received oral treatment had worse progression‐free survival (PFS) than those who received IV treatment. Use of two formulations of oral therapy (UFT or Ftorafur, and eniluracil with oral 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU)) led to worse PFS in patients who received oral compared with IV treatment. Use of three other formulations of oral therapy (capecitabine, S‐1, and doxifluridine) led to similar PFS in patients who received oral compared with IV treatment. OS did not differ between patients treated with oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines. In terms of severe side effects, patients who received oral treatment were more likely to develop diarrhoea and hand and foot rash but were less likely to have lowered white cell counts than those who received IV treatment.

Quality of the evidence

Review authors assessed the quality of evidence for the main outcomes in this review (DFS and PFS) as moderate; the key reason for downgrading quality involved issues with study design. The quality of evidence for OS in patients who were treated with the aim of cure and in patients who were treated with palliative chemotherapy was high. The quality of evidence for side effects ranged from very low to moderate, and was downgraded because of issues with study design, dissimilar results across studies, or not enough data.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oral compared with intravenous fluoropyrimidines for colorectal cancer ‐ Patients treated with curative intent.

| Oral compared with intravenous fluoropyrimidines for colorectal cancer ‐ Patients treated with curative intent | |||||

|

Patient or population: Patients treated with curative intent for colorectal cancer with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy Setting: Hospital Intervention: Oral fluoropyrimidines Comparison: Intravenous fluoropyrimidines | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk* | Corresponding risk** | ||||

| Intravenous fluoropyrimidines | Oral fluoropyrimidines | ||||

| Disease‐free survival | 313 per 1000a | 291 per 1000 (272 to 313) |

HR 0.93 (0.87 to 1.00) | 8903 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEb |

| Overall survival | 222 per 1000c | 204 per 1000 (186 to 222) |

HR 0.92 (0.84 to 1.00) |

8902 (7 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Grade ≥ 3 diarrhoea | 137 per 1000d | 153 per 1000 (135 to 171) |

OR 1.12 (0.99 to 1.25) | 9551 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWb,e,f |

| Grade ≥ 3 hand foot syndrome | 8 per 1000d | 37 per 1000 (24 to 57) |

OR 4.59g (2.97 to 7.10) | 5731 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,e |

| Grade ≥ 3 neutropenia/granulocytopenia | 181 per 1000d | 25 per 1000 (20 to 29) |

OR 0.14 (0.11 to 0.16) |

8087 (7 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEe |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in footnotes. **The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Pooled estimates from fixed‐effects meta‐analysis are reported in the table CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratio; RCTs: randomised controlled trials; OR: Odds ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | |||||

aThe assumed risk for disease‐free survival was based on the 3‐year disease‐free survival rate in the control group from studies in the meta‐analysis (68.7%)

bDowngraded by one level owing to a high risk of bias in included studies.

cThe assumed risk for overall survival was based on the 5‐year overall survival rate in the control group from studies in the meta‐analysis (77.8%)

dThe assumed risk for each grade ≥ 3 AE was the mean risk in the control group from studies in the meta‐analysis

eDowngraded by one level owing to inconsistency of results that was supported by non‐overlapping CIs, high I2 values, and statistically significant heterogeneity of effect estimates

fDowngraded by one level owing to imprecision

gRandom‐effects estimate, OR 2.36 (95% CI 0.52 to 10.74). Pooled effect estimate was sensitive to the meta‐analysis model used

Summary of findings 2. Oral compared with intravenous fluoropyrimidines for colorectal cancer ‐ Patients treated with palliative intent.

| Oral compared with intravenous fluoropyrimidines for colorectal cancer ‐ Patients treated with palliative intent | |||||

|

Patient or population: Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer with chemotherapy Setting: Hospital Intervention: Oral fluoropyrimidines Comparison: Intravenous fluoropyrimidines | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk* | Corresponding risk** | ||||

| Intravenous fluoropyrimidines | Oral fluoropyrimidines | ||||

| Progression‐free survival | 398 per 1000a | 422 per 1000 (406 to 442) |

HR 1.06 (1.02 to 1.11) | 9927 (23 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEb |

| Overall survival | 336 per 1000c | 343 per 1000 (333 to 353) |

HR 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) |

12,079 (29 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Grade ≥ 3 diarrhoea | 120 per 1000d | 199 per 1000 (180 to 221) |

OR 1.66 (1.50 to 1.84) | 11,997 (30 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,e |

| Grade ≥ 3 hand foot syndrome | 13 per 1000d | 51 per 1000 (37 to 71) |

OR 3.92 (2.84 to 5.43) | 6481 (18 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEb |

| Grade ≥ 3 neutropenia/granulocytopenia | 331 per 1000d | 56 per 1000 (50 to 60) |

OR 0.17 (0.15 to 0.18) |

11,794 (29 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,e |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in footnotes. **The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Pooled estimates from fixed‐effects meta‐analysis are reported in the table CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratio; RCTs: randomised controlled trials; OR: Odds ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | |||||

aThe assumed risk for progression‐free survival was based on the 6‐month progression‐free survival rate in the control group from studies in the meta‐analysis (60.2%)

bDowngraded by one level owing to a high risk of bias in included studies

cThe assumed risk for overall survival was based on the 12‐month overall survival rate in the control group from studies in the meta‐analysis (66.4%)

dThe assumed risk for each grade ≥ 3 AE was the mean risk in the control group from the studies in the meta‐analysis

eDowngraded by one level owing to inconsistency of results that was supported by non‐overlapping CIs, high I2 values, and statistically significant heterogeneity of effect estimates

Background

Description of the condition

Worldwide, colorectal carcinoma (CRC) has the third highest incidence rate and the fourth highest mortality rate of all cancers (Ferlay 2013). In 2012, an estimated 1,360,602 new cases and an estimated 693,933 deaths from CRC occurred worldwide (Ferlay 2013). Approximately 20% of patients diagnosed with CRC have distant metastases at diagnosis, and a further 25% to 35% will develop metastases at a later time (Siegel 2017; Van Cutsem 2006; Van der Geest LGM). This contributes to the high mortality rates observed for CRC (Ferlay 2013).

Description of the intervention

Fluoropyrimidines have been an essential part of treatment for CRC for over 40 years.

For patients with colon cancer treated with curative intent, recommendations regarding use of adjuvant chemotherapy following resection of the primary tumour vary, depending on the stage of disease. TNM stage II disease is defined as T3 or T4 but node negative, whilst TNM stage III disease is defined as any T stage and node positive (Edge 2009). Use of adjuvant 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU)‐based chemotherapy has been demonstrated to improve survival (Francini 1994; IMPACT Investigators 1995; Laurie 1989; Moertel 1990; O'Connell 1997); subsequently, six months' duration of adjuvant 5‐FU/leucovorin (LV) was established as the standard of care for patients with stage III colon cancer (Dencausse 2002; Haller 2005; O'Connell 1998). More recent research has shown that oxaliplatin added to six months of adjuvant 5‐FU/LV chemotherapy leads to further improvement in both five‐year disease‐free survival (DFS) and six‐year overall survival (OS) compared with 5‐FU/LV alone for stage III colon cancer (André 2009).

Survival outcomes for stage II colon cancer are better than for stage III disease, and the survival benefit derived from use of adjuvant chemotherapy is accordingly less in this setting (André 2009; Brenner 2014; Figueredo 2008; Gill 2004; Gray 2007; IMPACT Investigators 1995; Sargent 2009). American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines state that direct evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) does not support the routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II disease (Benson 2004). Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that for stage II colon cancer, physician and patient discussion should include potential benefits versus risks of adjuvant chemotherapy. This discussion should encompass consideration of high‐risk features (both clinicopathological and molecular), as well as indirect evidence, potential treatment‐related morbidity and patient co‐morbidities, anticipated life expectancy, and patient preferences (NCCN 2016).

The current standard of care for stage II and III rectal carcinoma is curative intent treatment based on a combined‐modality approach. This consists of neoadjuvant chemo‐radiotherapy with 5‐FU, total mesorectal excision (TME), and adjuvant chemotherapy with 5‐FU and oxaliplatin (Weiser 2015).

In patients with inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC, use of palliative intent IV 5‐FU‐based therapy has led to improved survival outcomes (Nordic 1992; Scheithauer 1993). Subsequent advances including optimisation of IV 5‐FU regimens and combination with irinotecan and oxaliplatin chemotherapy have led to further improvements in median OS (Lucas 2011). Over the past decade, anti‐angiogenic therapies have been successfully combined with fluoropyrimidine‐based chemotherapy. A pivotal phase III trial examined bevacizumab (BEV), a humanised monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), by randomising participants to irinotecan, fluorouracil, leucovorin (IFL)/placebo (control), and IFL/BEV or 5‐FU/LV/BEV (Hurwitz 2004). Overall, results showed significant improvement in the endpoints of OS, progression‐free survival (PFS), and median duration of response in the IFL/BEV arm. Survival benefits were also reported in a second‐line study which compared oxaliplatin, fluorouracil and leucovorin (FOLFOX4)‐BEV with FOLFOX4 alone (Giantonio 2007) and in the first‐line MAX trial (Tebbutt 2010), which reported that BEV added to the oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine improved PFS. Subsequently, the benefit of continuing BEV beyond progression in combination with a second‐line fluoropyrimidine‐based chemotherapy was demonstrated in the phase III TML study (Bennouna 2013). Furthermore, the anti‐angiogenic drugs ziv‐aflibercept and ramucirumab, in combination with infusional 5‐FU, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI), were demonstrated to prolong PFS and OS in the second‐line setting (Tabernero 2015; Van Cutsem 2012).

Cetuximab, an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody, added to FOLFIRI in the first‐line setting, was shown to improve efficacy in patients with KRAS wild‐type metastatic CRC (Van Cutsem 2011). Similarly, panitumumab, a fully humanised antibody to EGFR, was shown to be effective for this subset of patients in the first‐ and second‐line setting when combined with fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy (Douillard 2010; Peeters 2010).

How the intervention might work

Intravenous and oral 5‐FU have been used in the treatment of cancer for several decades. Owing to its unpredictable gastrointestinal absorption and marked variation in pharmacokinetics, use of oral 5‐FU alone was abandoned early. Since that time, research has focused on the biomodulation of 5‐FU to improve its therapeutic effectiveness and cytotoxicity. Leucovorin (LV), an intracellular source of reduced folates, acts by stabilising the complex formed by 5‐FU with thymidylate synthase (TS) and 5‐fluoro‐deoxyuridine monophosphate (5‐FdUMP), leading to prolonged TS inhibition and enhanced efficacy. Eniluracil is a potent inactivator of the principal 5‐FU degradation enzyme dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD), and co‐administration with oral 5‐FU significantly increased oral bioavailability whilst decreasing 5‐FU pharmacokinetic variability (reviewed in Schilsky 2002b). Development of this combination was discontinued in 2000.

Several other oral fluoropyrimidines have been designed and currently are undergoing clinical trials or are used routinely in the clinic. Doxifluridine (5’‐dFUR) consists of a 5‐FU molecule attached to a pseudo‐pentose, thus it cannot be directly metabolised in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA) synthesis. With exposure to pyrimidine phosphorylases found at higher concentrations in tumours, 5'‐dFUR is preferentially converted to active 5‐FU in malignant tissue (reviewed in Calabresi 1991). Ftorafur (FTO; Tegafur) is a second‐generation fluoropyrimidine prodrug which provides more prolonged and stable release of 5‐FU. UFT, which comprises FTO and uracil in molar proportions of 1:4, is a third‐generation drug designed to improve the therapeutic index of FTO. Uracil, a natural substrate of DPD, is converted preferentially in lieu of FTO owing to its higher molar concentration in this formulation, resulting in a prolonged 5‐FU elimination half‐life. It has been combined with LV under the trade name Orzel. Capecitabine, another third‐generation drug, is the most commonly used oral fluoropyrimidine worldwide. Designed to limit gastrointestinal toxicity, capecitabine resists enzymatic degradation by thymidine phosphorylase (TP) in the intestine and undergoes a three‐stage conversion with eventual transformation to active 5‐FU in the tumour tissue, where TP levels are highest. S‐1 is a combination of FTO and two biomodulators ‐ 5‐chloro‐2,4‐dihydroxypyridine (CDHP) and potassium oxalate (OXO). CDHP is a potent, reversible inhibitor of DPD which is used to achieve prolonged higher concentrations of 5‐FU in the circulation. OXO acts to limit the gastrointestinal toxicity associated with phosphorylation of 5‐FU in the gastrointestinal tract. OXO accumulates in gastrointestinal tissues, where it inhibits phosphorylation of 5‐FU into 5‐fluorouridine‐5′‐monophosphate (5‐FUMP) by orotate phosphoribosyl transferase (OPRT) (reviewed in Hoff 2000 and Malet‐Martino 2002).

More recently, TAS‐102, an oral combination of trifluridine (FTD, a thymidine‐based nucleoside analogue) and tipiracil (a TP inhibitor which improves bioavailability of FTD), was demonstrated to confer an overall survival benefit in the metastatic chemo‐refractory setting (Mayer 2015). At the dosing schedule used in the clinical development of TAS‐102, its clinically relevant mechanism of action consists of incorporation into DNA and subsequent DNA dysfunction, rather than TS inhibition (reviewed in Lenz 2015). We considered its mechanism of action to be distinct from that of the other fluoropyrimidines described here and did not search for studies examining TAS‐102 for inclusion in this review.

Why it is important to do this review

Patients prefer oral over IV administration of palliative chemotherapy for multiple cancers, including CRC, provided that oral therapy is not less effective. Reasons include the convenience of home‐based treatment with a tablet formulation (Borner 2002; Liu 1997; Twelves 2006).

Oral fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy has been compared with IV fluoropyrimidine in patients with CRC who have been treated with curative or palliative intent. However, researchers have reported variable results with respect to efficacy and adverse events (Chau 2009).

Differences in the efficacy and adverse event profiles of IV fluoropyrimidines depend on whether infusional or bolus regimens are used (Meta‐analysis Group in Cancer 1998a; Meta‐analysis Group in Cancer 1998b). Different oral fluoropyrimidines may also have different efficacy and adverse event profiles (Hamaguchi 2015; Hong 2012; Kwakman 2017). For patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC, efficacy and adverse event outcomes for oral compared with IV fluoropyrimidines may vary, depending on whether fluoropyrimidines are combined with irinotecan versus oxaliplatin chemotherapy (Chau 2009). Combination cancer therapy can improve efficacy but can also increase toxicity (Braun 2011). Therefore, it is important to assess whether efficacy and adverse event outcomes differ between oral and IV fluoropyrimidines, depending on whether patients with CRC receive chemotherapy alone versus chemo‐radiotherapy (in curative intent studies) or single‐agent versus combination chemotherapy (in palliative intent studies).

We were unable to identify a previous meta‐analysis and systematic review that examined a wide range of oral fluoropyrimidines, nor were we able to find a systematic review that performed subgroup analyses examining chemotherapy versus chemo‐radiotherapy (in curative intent studies) and single‐agent versus combination therapy (in palliative intent studies), infusional versus bolus IV fluoropyrimidine, the oral fluoropyrimidine backbone used, and oxaliplatin‐based versus irinotecan‐based combination therapy.

Objectives

To compare the effects of oral and IV fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy in patients treated with curative or palliative intent for CRC.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs with treatment arms comparing oral fluoropyrimidine versus IV fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy.

Studies with a cross‐over design from oral to IV fluoropyrimidine, or vice versa, were eligible for inclusion only if the cross‐over design permitted all relevant treatment arms to crossover.

We included studies regardless of publication status and blinding of participants, personnel, and/or outcome assessment. We applied no language restrictions and did not use outcomes as criteria for considering studies for inclusion in this review.

Types of participants

We included patients who were treated with curative intent for CRC and received neoadjuvant (preoperative) and/or adjuvant (postoperative) chemotherapy. For adjuvant chemotherapy, we included patients with stage II or III colon cancer.

We included patients who were treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC and received chemotherapy.

We included only patients for whom a diagnosis of CRC had been confirmed by histopathology or cytology. We did not restrict patients by gender, age, or ethnic group.

If a study included relevant patients as a subgroup and if outcomes related to this subgroup were reported separately, we included the patients who were eligible for this review (e.g. Fuchs 2007).

Types of interventions

Oral fluoropyrimidine treatment included any fluoropyrimidine administered orally (e.g. capecitabine, S‐1, ftorafur, UFT, doxifluridine, 5‐ethynyluracil). IV fluoropyrimidine treatment included agents administered by bolus and by infusion.

For oral and IV fluoropyrimidine treatments, we did not restrict dose, frequency, intensity, and duration of treatment.

We included oral and IV fluoropyrimidine treatments that were administered as a single agent, or in combination with any other cytotoxic agent/s (e.g. irinotecan, oxaliplatin) and targeted therapies (e.g. bevacizumab, cetuximab). In the case of combination therapy, we included only studies in which the same cytotoxic agents and targeted therapies were administered in both the oral and the IV fluoropyrimidine arms.

We also included oral and IV fluoropyrimidine treatments that were administered with radiotherapy (chemo‐radiotherapy). In the case of chemo‐radiotherapy, we included only studies in which radiotherapy was administered in both the oral and the IV fluoropyrimidine arms.

Cross‐over studies were eligible for inclusion only if participants in both the oral and the IV fluoropyrimidine arms received at least three cycles of chemotherapy before crossover.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy

Disease‐free survival (DFS), defined as time from randomisation until death from any cause or disease recurrence, whichever occurred first

Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with chemotherapy

Progression‐free survival (PFS), defined in this review as time from randomisation until death from any cause or disease progression, whichever occurred first

Secondary outcomes

Patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy

Overall survival (OS)

Grade ≥ 3 adverse events (AEs) (diarrhoea, hand foot syndrome (HFS), neutropenia/granulocytopenia, febrile neutropenia, vomiting, nausea, stomatitis, mucositis, hyperbilirubinaemia, any grade ≥ 3 AEs) assessed on the basis of National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) or similar criteria

Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with chemotherapy

OS

Time to progression (TTP), defined in this review as time from randomisation until disease progression

Objective response rate (ORR), with objective response defined as best response assessed as a complete response (CR) or a partial response (PR) on the basis of Response Evaluation Critieria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) or similar criteria

Incidence of grade ≥ 3 AEs listed above

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases with no limitation on publication year or language.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on 14 June 2016 (2016, Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE (OVID) from 1950 to 14 June 2016 (Appendix 2).

Embase (OVID) from 1974 to 14 June 2016 (Appendix 3).

Web of Science (Web of Knowledge) from 1900 to 16 June 2016 (Appendix 4).

The first three searches were performed by the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group Information Specialist.

We searched the following trials registries.

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) on 8 June 2016, with no limitations on the date trial information was received or updated.

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/) on 29 August 2016, with no date restrictions on date of registration.

Current Controlled Trials, using the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Register (International) (www.controlled‐trials.com) on 9 June 2016, with no date limitations.

The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR) (www.anzctr.org.au) on 16 June 2016, with no limitations on trial registration or start dates.

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) clinical trials database (www.eortc.org/clinical‐trials/) on 16 June 2016, with no date limitations.

Searching other resources

We searched for additional trials not identified in the above electronic searches by searching relevant proceedings for oncology meetings and conferences. We searched the following proceedings.

American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO), search of the electronic database of meeting abstracts (http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/abstracts) from 2004 to 15 June 2016.

European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), handsearched from 2000 to 14 June 2016.

European Cancer Conference, handsearched from 1993 to 14 June 2016.

We searched the reference lists of identified studies and other systematic reviews, and wrote to the following pharmaceutical companies involved in the manufacture of oral fluoropyrimidines: Orzel, Adherex, Roche, Merck Serono, Sanofi Aventis, and Taiho.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (FC and YY or DL) selected trials for inclusion independently, and resolved queries or disagreements with assistance from a fourth review author (NT). We used a standard checklist of inclusion and exclusion criteria to select studies. We listed excluded trials and reasons for their exclusion. We wrote to investigators for clarification when we could not determine eligibility from published report/s for the study.

Data extraction and management

We collected data from the reports for included studies by using Data Extraction Forms that we had piloted successfully. Two or three review authors (FC and YY or DL) performed this independently, and a fourth review author (NT) resolved disagreements.

We collected the following information about the included studies: study design and setting, study eligibility criteria, participant characteristics, intervention(s) given, outcomes assessed, funding sources, and declarations of interest of the primary researchers. We used this information to populate the Characteristics of included studies tables.

When an included study had multiple reports, we used the report with the most recent data for a specific outcome to extract data for that outcome. When applicable and if necessary, we used other study reports to extract additional information required, including study characteristics and information for risk of bias assessments.

We examined retraction statements and errata associated with included studies and, when applicable, updated recorded data accordingly.

If required, we contacted study authors of the included studies for clarification or for additional information, which we then used in analyses of treatment effects and/or risk of bias assessments.

We checked the magnitude and direction of effects reported by studies against the data presented in our review.

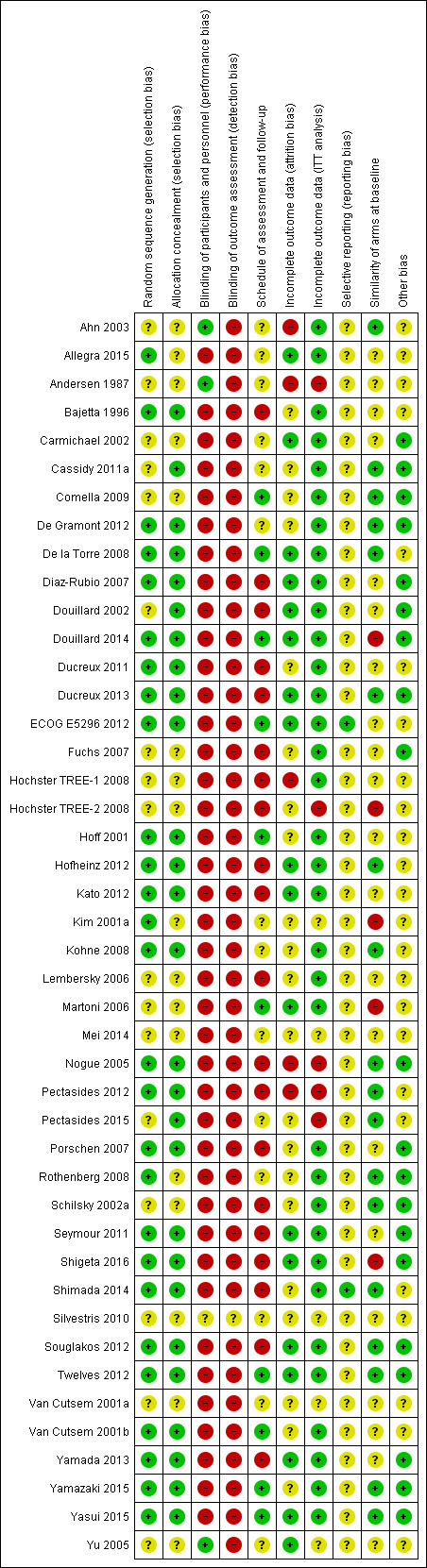

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (FC and YY or DL) independently assessed risk of bias of included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011a); NT resolved queries or disagreements. We assessed the following risk of bias domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias including the following.

Use of subsequent therapies in treatment arms.

For patients treated with curative intent for CRC who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, we assessed subsequent treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy.

For patients treated with curative intent for CRC who received adjuvant chemotherapy, we assessed subsequent treatment with chemotherapy following recurrence or new occurrence of CRC.

For patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC who received chemotherapy, we assessed subsequent‐line palliative drug therapy following progressive disease.

In factorial trials, assessment of important interactions between effects of different interventions (Higgins 2011b).

We assessed an additional three domains that we judged to be important for risk of bias assessment of included studies.

-

Comparable schedule of assessment and/or follow‐up for outcomes in different treatment arms.

We assessed risk as 'High' if we noted differences in the frequency of outcome assessments between treatment arms, 'Low' if frequency of assessment was the same in the treatment arms, and 'Unclear' if insufficient information was provided to allow assessment.

-

Incomplete outcome data (intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis).

We defined ITT analysis as analysis of randomised participants for efficacy and safety outcomes according to allocated treatment, irrespective of whether participants were eligible, received the allocated treatment, received another treatment, or received no treatment.

We assessed risk as 'High' if the efficacy analysis was clearly not an ITT analysis as defined, and/or if ≥ 5% of participants were excluded from the analysis. We assessed risk as 'Unclear' if insufficient information was provided to allow assessment, and we assessed all other studies as 'Low' risk.

-

Comparability of treatment arms at baseline.

This included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)/Karnofsky/World Health Organization (WHO)/Zubrod performance status (PS); median or mean age; TNM stage and/or stage II vs III for patients treated with curative intent and number of involved organs for patients treated with palliative intent; and difference in the proportion of participants with KRAS‐mutant CRC among those treated with palliative intent using EGFR inhibitors.

We assessed risk as 'High' if differences between treatment arms at baseline were ≥ 15% for PS; ≥ 5 years for age; ≥ 15% for stage or number of involved organs; or ≥ 10% for KRAS mutant status. We assessed risk as 'Unclear' if insufficient information was provided to allow assessment, and we assessed all other studies as 'Low' risk.

We contacted study authors of included studies when we needed clarification or additional information.

Evaluation of risk of bias for outcomes

We assessed risk of bias for all studies that contributed to each of the review outcomes, as follows.

We judged a study contributing to an outcome to be at high risk of bias if we assessed it as having 'High' risk of bias for one or more domains relevant to the outcome.

We judged a study contributing to an outcome to be at low risk of bias if we assessed it as having 'Low' risk of bias for all domains relevant to the outcome.

We judged a study contributing to an outcome to be at unclear risk of bias if we assessed it as having 'Unclear' risk of bias for one or more domains relevant to the outcome, but we did not assess any domain as 'High' risk.

We used risk of bias assessments for each contributing study to summarise risk of bias for each outcome.

Measures of treatment effect

Time‐to‐event data

We expressed effect estimates as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the following time‐to‐event outcomes.

-

Patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy.

DFS, OS.

-

Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with chemotherapy.

PFS, TTP, and OS.

Dichotomous data

We expressed summary statistics as odd ratios (ORs) for the following dichotomous outcomes.

-

Patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy.

Grade ≥ 3 AEs.

-

Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with chemotherapy.

ORR, grade ≥ 3 AEs.

Statistical methods for data analysis

Specific outcomes

Time‐to‐event outcomes

When possible, we extracted hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or standard error of the natural logarithm of HR (se(lnHR)) directly from reports of studies or from correspondence with study authors and contacts; if not reported, we estimated these indirectly from the study reports.

A statistician estimated HRs and se(lnHR) indirectly from Kaplan‐Meier survival curves using the method described by Tierney et al. (Tierney 2007). For one study (Douillard 2002), a statistician indirectly estimated the HR and the se(lnHR) for TTP using a ratio of the median TTP to approximate the HR, and the stratified log‐rank P value to approximate the se(lnHR). For studies for which CIs for effect estimates were not reported as 90%, 95%, or 99% CIs for input into Review Manager 5, a statistician used the indirect variance estimation method to determine the se(lnHR) of the reported HR (Tierney 2007).

For patients treated with curative intent for CRC who received neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy, we measured DFS and OS after a minimum of three years' follow‐up.

Dichotomous outcomes

ORR

For ORR, we calculated the OR using the number of participants who achieved an objective response as the number of 'events', and the total number of participants who were assessable or evaluable for response as the 'total'. When the latter information was not specified, we used the number of participants in the ORR population, which was reported for the study as the 'total'. When only the percentage of participants who achieved an objective response in the treatment arms was reported, we used this percentage and the number of participants in the ORR population to calculate the number of 'events'. If this percentage was reported as "less than x%", we used the absolute value of x. For studies that did not specify a separate ORR population, we used the number of participants in the overall analysis population as the 'total'.

For studies that reported ORRs assessed by both Investigator Assessment and an Independent Review Committee (IRC), we used the ORR from the Investigator Assessment, as most studies did not undergo IRC assessment.

Grade ≥ 3 AE outcomes

For grade ≥ 3 AE outcomes, we calculated the OR using the number of participants who experienced grade ≥ 3 AEs as the number of 'events', and the number of participants included in the safety analysis population as the 'total'. When only the percentage of participants who experienced grade ≥ 3 AEs in the treatment arms were reported, we used this percentage and the number of participants in the safety analysis population to calculate the number of 'events'. If this percentage was reported as "less than x %", we used the absolute value of "x". When a separate safety analysis population denominator was not specified, we used the number of participants in the overall analysis population as the 'total'.

We only quantitatively synthesised HFS data that had been assessed as grade ≥ 3 using NCI CTCAE (versions 2.0 to 4.0), as assessments of grade ≥ 3 HFS using other criteria were not considered sufficiently similar.

We quantitatively synthesised hyperbilirubinaemia data that had been assessed as grade ≥ 3 using NCI CTCAE (versions 2.0 to 4.0 and 1981) and WHO (1981 version). Additionally, we considered hyperbilirubinaemia assessed as grade 4 using NCI CTCAE (1994 version), National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC‐CTG) Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) (1991 version), Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) (1992 version), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) CTC to also be sufficiently similar to hyperbilirubinaemia assessed as grade ≥ 3 using NCI CTCAE (versions 2.0 to 4.0 and 1981) and WHO (1981 version), and we included these data in our quantitative synthesis.

Data presented for different populations

When study authors presented efficacy data for both 'per protocol' and ITT populations (as defined in the study report), we used results for the ITT population.

When study authors presented data for both the safety analysis population and those with available safety data, we used data from the safety analysis population.

Non‐inferiority analysis

In our original protocol, we did not hypothesise that one route of fluoropyrimidine administration (oral or IV) was superior to the other. As such, we did not state a priori levels of benefit.

However, in response to a peer reviewer suggestion, we defined non‐inferiority (NI) margins for the primary outcomes DFS and PFS whereby 50%, 70%, 80%, and 90% of the activity of the active control was retained had the original design been one of non‐inferiority, using IV fluoropyrimidines as the historical active control (FDA 2010). We determined these NI margins independent of studies comparing oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines. In response to an editor suggestion, we assessed whether non‐inferiority had been demonstrated if one made the post hoc judgement that retaining at least 80% of the activity of the active control was reasonable to demonstrate this.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies with multiple treatment arms

In the case of studies with multiple treatment arms:

if one or more treatment arms in a study did not contain an oral fluoropyrimidine or IV fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy, we omitted these arms from the analysis;

when two IV fluoropyrimidine treatment arms contained similar regimens with respect to the outcome or subgroup analysis being examined (and it was considered clinically appropriate to pool the arms), we combined these treatment arms to create a single pair‐wise comparison with the oral fluoropyrimidine treatment arm; and

when two IV fluoropyrimidine treatment arms contained regimens that were different with respect to the outcome or subgroup analysis of interest (and it was not considered clinically appropriate to pool the arms), we used these treatment arms in separate comparisons. In such cases, we used half of the sample size of the experimental oral fluoropyrimidine arm for each comparison.

Cross‐over studies

For cross‐over studies, we measured the outcomes DFS, TTP, PFS, ORR, and grade ≥ 3 AEs (not OS) before crossover.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the study authors to request missing summary data. If study authors provided us with this data, we included these data in the analyses. If this information was not provided to us by study authors, when possible, we extracted and analysed data as described in 'Statistical methods for data analysis'. With respect to missing individual data, we did not use an imputation method for sensitivity analyses of primary (time‐to‐event) outcomes. We identified studies that did not perform an intention‐to‐treat analysis, assessed associated risk of bias (reported in 'Risk of bias' tables), and incorporated this information into our assessments of quality of evidence for all outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity with focus on included participants, interventions, and measurements of outcomes (Discussion). We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test, with the level of statistical significance set at 5%. We quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, with interpretation of I2 guided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011) ‐ 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

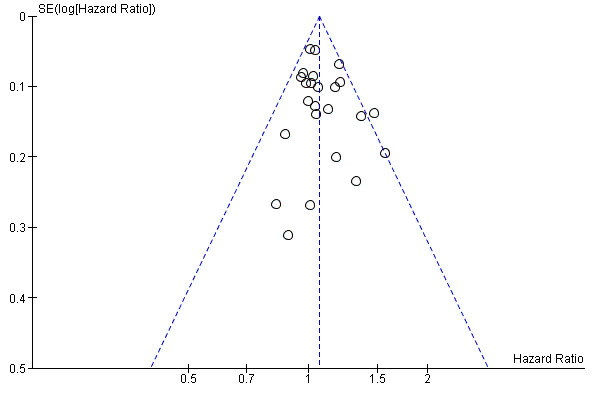

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias using symmetry of the funnel plot for the co‐primary endpoint PFS, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011). As we included only seven studies in the pooled estimate for DFS, we did not examine a funnel plot for this outcome.

Data synthesis

We performed quantitative synthesis of aggregate data using HR and OR effect estimates, and using fixed‐effect model (FEM) meta‐analysis in Review Manager software (RevMan [Computer Program]). We used the generic inverse‐variance method for meta‐analysis of time‐to‐event outcomes, and the Mantel‐Haenszel method for meta‐analysis of dichotomous outcomes (Higgins 2011c).

Multiple included studies reported the outcomes grade ≥ 3 vomiting and nausea and grade ≥ 3 mucositis and stomatitis in combination. We therefore performed quantitative synthesis of these outcomes as follows.

Grade ≥ 3 vomiting included data from studies that reported either grade ≥ 3 vomiting alone, or grade ≥ 3 vomiting or nausea.

Grade ≥ 3 nausea included data from studies that reported either grade ≥ 3 nausea alone, or grade ≥ 3 vomiting or nausea.

Grade ≥ 3 stomatitis included data from studies that reported grade ≥ 3 stomatitis alone, or grade ≥ 3 stomatitis or mucositis.

Grade ≥ 3 mucositis included data from studies that reported either grade ≥ 3 mucositis alone, or grade ≥ 3 stomatitis or mucositis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used prespecified tests for heterogeneity to compare treatment effects between subgroups (Higgins 2011c), defined by the following intervention characteristics.

Chemotherapy versus chemo‐radiotherapy received (among participants treated with curative intent for CRC)or single‐agent versus combination therapy received (among participants treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC).

Infusional versus bolus IV fluoropyrimidine received.

Type of oral fluoropyrimidine backbone given (e.g. capecitabine vs UFT/Ftorafur vs Eniluracil + oral 5‐FU vs doxifluridine vs S‐1).

Oxaliplatin‐based versus irinotecan‐based therapy received (among participants treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC who received combination chemotherapy).

Bevacizumab (BEV) received versus not received (among participants treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC who received combination chemotherapy) ‐ this was a post hoc analysis for the PFS outcome only.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed the following sensitivity analyses for primary outcomes to evaluate the robustness of meta‐analysis results.

Excluded studies assessed as having 'High' risk of bias (DFS and PFS).

Excluded Seymour 2011, wherein the study population differed from the study populations of most studies (frail and elderly) (PFS).

Excluded studies of second‐line palliative chemotherapy and studies that included a combination of first‐ and second‐line palliative chemotherapy (PFS).

In response to an editor suggestion, for the comparison of oral versus IV fluoropyrimidines in patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy, we performed a sensitivity analysis for grade ≥ 3 HFS, which incorporated heterogeneity by using a random‐effects model (REM) for meta‐analysis in Review Manager software (DerSimonian 1986; RevMan [Computer Program]).

'Summary of findings' table

We assessed the quality of evidence for all outcomes using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Guyatt 2008a; Guyatt 2008b). We used GRADEpro (GRADEpro [Computer program]) to create 'Summary of findings' tables for the following outcomes, which we assessed as most important.

-

Patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy.

DFS.

OS.

Grade ≥ 3 diarrhoea.

Grade ≥ 3 HFS.

Grade ≥ 3 neutropenia/granulocytopenia.

-

Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with chemotherapy.

PFS.

OS.

Grade ≥ 3 diarrhoea.

Grade ≥ 3 HFS.

Grade ≥ 3 neutropenia/granulocytopenia.

We classified the quality of evidence into one of four grades.

High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

We downgraded the quality by one (serious concern) or two (very serious concern) levels for the following reasons: risk of bias, inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity, inconsistency of results), indirectness of evidence (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes), imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals), and risk of publication bias.

Protocol

The protocol for this review was published on 17 March 2010 (Chionh 2010).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

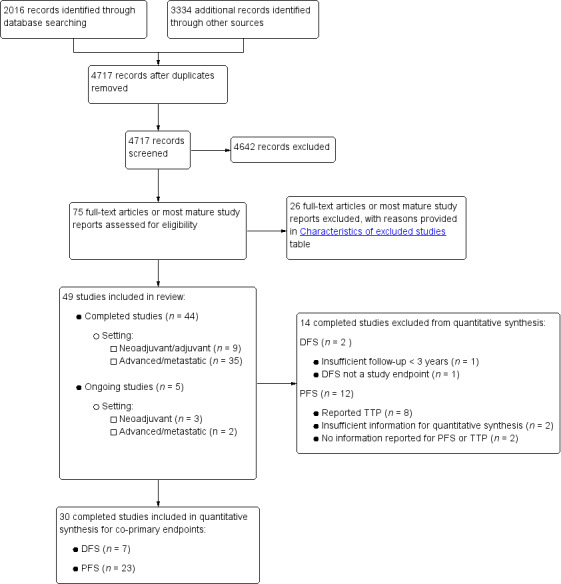

We have presented in Figure 1 the workflow for studies identified and included in the review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Using the search strategy described, we identified 2016 records from bibliographic databases and 3334 additional records through searches of 'other sources', which included trials registers and conference proceedings. We contacted pharmaceutical companies, and Taiho, Orzel, Adherex, and Roche provided us with lists of potentially eligible studies. After removing duplicates, we screened a total of 4717 records for inclusion.

Of these, we assessed the full‐text reports or the most mature study reports for 75 potentially eligible studies, and we identified 49 studies that met review inclusion criteria. Forty‐four of the included studies were completed studies (Characteristics of included studies), and five were ongoing, with ongoing accrual or follow‐up (Characteristics of ongoing studies). We had two studies translated from Chinese to English (Yu 2005; Mei 2014), and one from Korean to English (Kim 2001a) before we extracted data.

Included studies

Design

We included 44 studies in the review.

The nine studies of curative intent treatment with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy for CRC included 10,918 randomised participants (Table 3). These included eight phase 3 studies and one study that did not specify the phase of the study. One study of neoadjuvant treatment had a 2 × 2 factorial design (Allegra 2015).

1. Included studies ‐ Patients treated with curative intent for colorectal cancer.

| Treatment setting | Study ID | Phase | Treatment type | Treatment arm/s (oral), n randomised | Treatment arm/s (IV), n randomised | IV arm: bolus vs Infusional |

| Neoadjuvant | Rectal | |||||

| Allegra 2015 | III | Fluoropyrimidine combined with RT | Capecitabine (Grp 2), n = 146 Capecitabine (Grp 5), n = 326 Capecitabine + oxaliplatin (Grp 6), n = 330 |

5‐FU (Grp 1), n = 147 5‐FU (Grp 3), n = 330 5‐FU + oxaliplatin (Grp 4), n = 329 |

Infusional | |

| De la Torre 2008 | III | Fluoropyrimidine combined with RT | UFT (Tegafur/Uracil) + LV with RT, n = 78 | 5‐FU + LV with RT, n = 77 | Bolus | |

| Neoadjuvant/ Adjuvant |

Rectal | |||||

| Hofheinz 2012 | III | Fluoropyrimidine combined with RT | Capecitabine with RT, n = 197 ∙ Adjuvant cohort: n = 116 ∙ Neoadjuvant cohort: n = 81 |

5‐FU with RT, n = 195 ∙ Adjuvant cohort: n = 115 ∙ Neoadjuvant cohort: n = 80 |

Bolus and infusional | |

| Adjuvant | Rectal | |||||

| Kim 2001a | ND | Fluoropyrimidine combined with RT (after completion of 2C of fluoropyrimidine alone) | 5‐dFUR + LV, n = 92 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 74 | Bolus | |

| Colon | ||||||

| De Gramont 2012 | III | Combination chemotherapy ‐ Oxaliplatin + Bevacizumab (BEV) | BEV‐XELOX, n = 952 | BEV‐FOLFOX4, n = 960 | Infusional | |

| Lembersky 2006 | III | Fluoropyrimidine alone | UFT + LV, n = 805 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 803 | Bolus | |

| Shimada 2014 | III | Fluoropyrimidine alone | UFT + LV, n = 551 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 550 | Bolus | |

| Twelves 2012 | III | Fluoropyrimidine alone | Capecitabine, n = 1004 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 983 | Bolus | |

| Colorectal | ||||||

| Pectasides 2015 | III | Combination chemotherapy ‐ fluoropyrimidine + oxaliplatin | CAPOX (capecitabine + oxaliplatin), n = 197 | mFOLFOX6, n = 211 | Infusional | |

IV: intravenous

RT: radiotherapy

5‐FU: 5‐fluorouracil

UFT: tegafur/uracil

LV: leucovorin

ND: no data available

5‐dFUR: doxifluridine

BEV: bevacizumab

The 35 studies of palliative intent treatment with chemotherapy for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC included 12,592 randomised participants (Table 4; Table 5). These included 10 phase 2 and 17 phase 3 studies, along with six studies that did not specify the phase of the study. Study authors described one study as phase 4 in previous abstracts but specified no phase in the journal report (Nogue 2005), and another study as phase 2/3 (Yasui 2015). Three of these studies used a 2 × 2 factorial design (Cassidy 2011a; Kohne 2008; Seymour 2011). Fuchs 2007 used a 3 × 2 factorial design to compare FOLFIRI, irinotecan plus bolus FU/LV (mIFL), and irinotecan plus oral capecitabine (CapeIRI) in period 1 of the trial, which was the only study period of interest for this review.

2. Included studies ‐ Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer (single‐agent fluoropyrimidines).

| Oral fluoropyrimidine backbone | Study ID | Phase | Treatment line | Treatment arm/s (Oral), n randomised | Treatment arm/s (IV), n randomised | IV arm: Bolus vs Infusional |

| Capecitabine | Hoff 2001 | III | First | Capecitabine, n = 302 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 303 | Bolus |

| Van Cutsem 2001b | III | First | Capecitabine, n = 301 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 301 | Bolus | |

| Doxifluridine (5‐dFUR) | Ahn 2003 | II | First | 5‐dFUR + LV, n = 38 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 39 | Bolus |

| Bajetta 1996 | II | First | 5‐dFUR + LV, n = 67 | 5‐dFUR + LV, n = 63 | Bolus | |

| Eniluracil + oral 5‐FU | ECOG E5296 2012 | III | First | Eniluracil/Oral 5‐FU, n = 61 | 5‐FU, n = 64 | Infusional |

| Schilsky 2002a | III | First | Eniluracil/Oral 5‐FU, n = 488 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 493 | Bolus | |

| Van Cutsem 2001a | III | First | Eniluracil/Oral 5‐FU, n = 268 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 263 | Bolus | |

| Ftorafur/tegafur (FT) | Andersen 1987 | ND | First | Ftorafur, n = 30 | 5‐FU, n = 30 | Bolus |

| Nogue 2005 | Unclear; described as Phase IV in abstracts | First | FT + LV, n = 114 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 123 | Bolus | |

| Ftorafur + uracil (UFT) | Carmichael 2002 | III | First | UFT + LV, n = 190 | 5FU + LV, n = 190 | Bolus |

| Douillard 2002 | III | First | UFT + LV, n = 409 | 5‐FU + LV, n = 407 | Bolus |

IV: intravenous

5‐FU: 5‐fluorouracil

LV: leucovorin

5‐dFUR: doxifluridine

ND: no data available

FT: tegafur

UFT: tegafur + uracil

3. Included studies ‐ Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer (combination chemotherapy).

| Chemotherapy | Study ID | Phase | Study design ‐ other details | Treatment line | Treatment arm/s (Oral), n randomised | Treatment arm/s (IV), n randomised | IV arm: Bolus vs Infusional |

| Oxaliplatin | Combination with capecitabine | ||||||

| Cassidy 2011a | III | 2 × 2 factorial ‐ following protocol amendment | First | XELOX alone, n = 317 | FOLFOX‐4 alone, n = 317 | Infusional | |

| XELOX + Placebo, n = 350 | FOLFOX‐4 + Placebo, n = 351 | Infusional | |||||

| XELOX + BEV, n = 350 | FOLFOX‐4 + BEV, n = 350 | Infusional | |||||

| Comella 2009 | III | First | OXXEL (Capecitabine + oxaliplatin), n = 158 | OXAFAFU (5‐FU/LV + Oxaliplatin), n = 164 | Bolus | ||

| Diaz‐Rubio 2007 | III | First | XELOX, n = 174 | FUOX (5‐FU + Oxaliplatin), n = 174 | Infusional | ||

| Ducreux 2011 | III | First | XELOX, n = 156 | FOLFOX‐6, n = 150 | Infusional | ||

| Hochster TREE‐1 2008 | ND | First | CapeOx, n = 50 | mFOLFOX6, n = 50 | Infusional | ||

| bFOL, n = 50 | Bolus | ||||||

| Hochster TREE‐2 2008 | ND | First | CapeOx + BEV, n = 74 | mFOLFOX6 + BEV, n = 75 | Infusional | ||

| bFOL + BEV, n = 74 | Bolus | ||||||

| Martoni 2006 | II | First | XELOX, n = 62 | pviFOX, n = 56 | Infusional | ||

| Porschen 2007 | III | First | CAPOX, n = 242 | FUFOX, n = 234 | Infusional | ||

| Rothenberg 2008 | III | Second | XELOX, n = 313 | FOLFOX‐4, n = 314 | Infusional | ||

| Seymour 2011 | ND | 2 × 2 factorial, cross‐over (only from no oxaliplatin to oxaliplatin) | First | Capecitabine or OxCap, n = 229 ∙ Capecitabine, n = 115 ∙ OxCap, n = 114 |

5‐FU or OxFU, n = 230 ∙ 5‐FU, n = 115 ∙ OxFU, n = 115 |

Infusional | |

| Combination with Ftorafur/uracil (UFT) | |||||||

| Douillard 2014 | II | First | UFOX + Cetuximab, n = 152 | FOLFOX4 + Cetuximab, n = 150 | Infusional | ||

| Combination with S‐1 | |||||||

| Mei 2014 | ND | First | SOX, n = 35 | FOLFOX4, n = 35 | Infusional | ||

| Yamada 2013 | III | First | SOX‐BEV, n = 256 | mFOLFOX6‐BEV, n = 256 | Infusional | ||

| Yamazaki 2015 | II | First | SOL (S‐1 + oxaliplatin + oral LV), n = 56 | mFOLFOX6, n = 51 | Infusional | ||

| Irinotecan | Combination with capecitabine | ||||||

| Ducreux 2013 | II | First | XELIRI + BEV, n = 72 | FOLFIRI + BEV, n = 73 | Infusional | ||

| Fuchs 2007 | III | 3 × 2 factorial (Period 1) | First | CapeIRI + Celecoxib/Placebo, n = 145 | FOLFIRI + Celecoxib/Placebo, n = 144 | Infusional | |

| mIFL + Celecoxib/Placebo, n = 141 | Bolus | ||||||

| Kohne 2008 | III | 2 × 2 factorial | First | CAPIRI + Celecoxib/Placebo, n = 44 | FOLFIRI + Celecoxib/Placebo, n = 41 | Infusional | |

| Pectasides 2012 | III | First | XELIRI + BEV, n = 143 | FOLFIRI + BEV, n = 142 | Infusional | ||

| Silvestris 2010 | II | First | XELIRI, n = ND | FOLFIRI, n = ND | Infusional | ||

| Souglakos 2012 | II | First | CAPIRI + BEV, n = 168 | FOLFIRI + BEV, n = 168 | Infusional | ||

| Yu 2005 | ND | First and second | Capecitabine + Irinotecan, n = 27 | 5‐FU + Irinotecan, n = 16 | Infusional | ||

| Combination with Ftorafur/uracil (UFT) | |||||||

| Shigeta 2016 | II | First | TEGAFIRI (UFT, leucovorin, irinotecan) ± BEV, n = 35 | FOLFIRI ± BEV, n = 36 | Infusional | ||

| Combination with S‐1 | |||||||

| Kato 2012 | II | First and second | Sequential IRIS‐BEV, n = 30 | mFOLFIRI‐BEV, n = 30 | Infusional | ||

| Yasui 2015 | II/III | Second | IRIS (Irinotecan + S‐1), n = 213 | FOLFIRI, n = 213 | Infusional | ||

IV: intravenous

BEV: bevacizumab

ND: no data available

UFT: tegafur/uracil

Sample size

Most studies reported a planned sample size with power considerations based on comparisons of efficacy or safety.

Among the studies of curative intent treatment with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy for CRC, Kim 2001a did not report sample size calculations. Sample size calculations for De Gramont 2012 were based on the DFS hazard rates for BEV‐FOLFOX4 versus FOLFOX4 or BEV‐capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) versus FOLFOX4 in patients with stage III disease. However, we compared treatment effects of BEV‐XELOX versus BEV‐FOLFOX4 in this review.

Among the studies of palliative intent treatment with chemotherapy for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC, six studies did not report sample size calculations (Ahn 2003; Andersen 1987; Mei 2014; Silvestris 2010; Van Cutsem 2001b (in abstract form only); Yu 2005), and in three studies, reported sample size calculations did not include power considerations based on comparisons of outcomes between treatment arms (Hochster TREE‐1 2008; Hochster TREE‐2 2008; Martoni 2006). Three other studies used a non‐comparative design (Bajetta 1996; Douillard 2014; Ducreux 2013).

Participants

No studies reported that they included patients younger than 18 years of age (information on youngest age was not provided for Kim 2001a, Lembersky 2006, Van Cutsem 2001a, and Yu 2005). Six out of nine studies of curative intent treatment with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy for CRC placed an upper limit on the age of eligible patients (Lembersky 2006 (upper limit 60 years); Kim 2001a (upper limit 70 years); Pectasides 2015, Shimada 2014, Twelves 2012 (upper limit 75 years); Bajetta 1996 (upper limit 80 years)). Nine out of 35 studies of palliative intent treatment with chemotherapy for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC placed an upper limit on age of eligible patients (Ahn 2003; Ducreux 2013; Kato 2012; Mei 2014; Shigeta 2016; Yasui 2015; Yu 2005 (upper limit 75 years); Bajetta 1996, Yamada 2013 (upper limit 80 years)).

All studies included both male and female participants.

Treatment type and line of treatment

Among studies of curative intent treatment for CRC, two studies examined neoadjuvant treatment alone for rectal carcinoma (De la Torre 2008; Allegra 2015), and one study explored use of both neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment for rectal carcinoma (Hofheinz 2012). Six studies examined adjuvant treatment alone, including four studies for colon carcinoma (De Gramont 2012; Lembersky 2006; Shimada 2014; Twelves 2012), one study for rectal carcinoma (Kim 2001a), and one study for carcinoma of the colon or rectum (Pectasides 2015) (Table 3). Among studies that included patients with rectal carcinoma, two studies required the distal border of the tumour to be < 12 cm from the anal verge (Allegra 2015; Kim 2001a), one study required the distal border of the tumour to be < 16 cm from the anal verge (Hofheinz 2012), and two studies did not describe anatomical criteria (De la Torre 2008; Pectasides 2015).

Among studies of palliative intent treatment with chemotherapy for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC, 31 were performed exclusively in the first‐line setting. One study had exclusion criteria that specified “no past history of chemotherapy or chemotherapy ceased for over six months” and included patients in the report who had been given first‐ and second‐line treatment (Yu 2005). Kato 2012 included patients given first‐ or second‐line treatment; if treatment was second‐line, first‐line therapy with FOLFOX was mandated. Two studies were conducted in the second‐line setting ‐ one in combination with oxaliplatin (Rothenberg 2008) and one in combination with irinotecan (Yasui 2015) (Table 4; Table 5).

Location

Among studies of curative intent treatment with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy for CRC, capecitabine trials were performed in Greece (Pectasides 2015), in Europe (Hofheinz 2012), and in the USA, Europe, Asia, Australia, and other countries (Twelves 2012; De Gramont 2012). The Allegra 2015 study was predominantly performed in North America. UFT studies were conducted at sites in Asia (Shimada 2014), Europe (De la Torre 2008), and North America (Lembersky 2006). The single doxifluridine study was performed in Asia only (Kim 2001a).

Among studies of palliative intent treatment with palliative chemotherapy for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC, all four S‐1 trials were performed in Asia only (Kato 2012; Yamada 2013; Yamazaki 2015; Yasui 2015). One Asia‐only study used capecitabine (Yu 2005); nine studies were conducted in Europe or included both European and non‐USA sites. Additionally, three European Intergroup studies were carried out ‐ Gruppo Oncologico Aree Metropolitane ‐ GOAM (Martoni 2006); Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meriodionale ‐ GOIM (Silvestris 2010); and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer ‐ EORTC (Kohne 2008). Two capecitabine studies were conducted in the USA (Hochster TREE‐1 2008; Hochster TREE‐2 2008), and four studies had sites in the USA and in other countries. UFT trials were conducted in Europe and in non‐USA countries (Carmichael 2002; Douillard 2014), and in the USA and in other countries (Douillard 2002). Non‐USA sites in the European UFT trials included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Israel (Carmichael 2002); and Asia, South America, Australia, and Israel (Douillard 2014); the Douillard 2002 study also included non‐USA sites in Europe, Canada, and Puerto Rico. One UFT study was based in Japan (Shigeta 2016). Tegafur was used in two European studies (Andersen 1987; Nogue 2005). Eniluracil was used in one USA study (ECOG E5296 2012); one study was performed in the USA and Canada (Schilsky 2002a), and one was an international study (Van Cutsem 2001a). Doxifluridine was used in Europe (Bajetta 1996), and in South Korea (Ahn 2003)(Characteristics of included studies).

Performance status

Although most studies included patients with ECOG PS 2 or less (or the equivalent Karnofsky PS (KPS)), the study population for Seymour 2011 comprised elderly and frail patients who were considered by the treating oncologist to be unsuitable for upfront full‐dose chemotherapy. One study (Andersen 1987) included patients with ECOG PS 3, although the proportion of patients with ECOG PS 3 was not clear (Characteristics of included studies).

Interventions

Among studies of curative intent treatment with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy for CRC, three studies used fluoropyrimidines alone (not in combination with other chemotherapy or radiotherapy). These studies included the oral fluoropyrimidines UFT (Lembersky 2006; Shimada 2014) and capecitabine (Twelves 2012). Three other studies combined single‐agent fluoropyrimidines with radiotherapy, and included the oral fluoropyrimidines UFT (De la Torre 2008), capecitabine (Hofheinz 2012), and doxifluridine (Kim 2001a). One study of neoadjuvant treatment investigated radiotherapy in combination with oral and intravenous fluoropyrimidines and oxaliplatin (Allegra 2015). Two studies of adjuvant treatment compared combination chemotherapy regimens (De Gramont 2012; Pectasides 2015) (Table 3).

Among studies of palliative intent treatment with chemotherapy for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC, 11 single‐agent studies compared IV fluoropyrimidines with the oral fluoropyrimidines capecitabine, doxifluridine, eniluracil/oral 5‐FU, and Ftorafur (Tegafur) or UFT. All but one study used IV 5‐FU; Bajetta 1996 compared oral and IV doxifluridine. All of the studies that examined IV 5‐FU as a single‐agent used bolus regimens, except ECOG E5296 2012, which used infusional IV 5‐FU (Table 4). All of the 24 studies that included combination chemotherapy used oxaliplatin or irinotecan (Table 5). Of the 14 studies that used oxaliplatin‐based combination chemotherapy, three trials included bolus 5‐FU arms (Comella 2009; Hochster TREE‐1 2008; Hochster TREE‐2 2008). Four studies that used oxaliplatin‐based combination chemotherapy examined combinations with the EGFR‐antibody cetuximab (Douillard 2014) or with BEV (Cassidy 2011a; Hochster TREE‐2 2008; Yamada 2013). Of the ten studies with irinotecan‐based combination chemotherapy, five trials included BEV‐containing arms (Ducreux 2013; Kato 2012; Pectasides 2012; Shigeta 2016; Souglakos 2012). Two further studies with a factorial design randomised participants to CAPIRI versus FOLFIRI plus celecoxib/placebo (Kohne 2008), or CapeIRI versus FOLFIRI versus mIFL plus celecoxib/placebo (Fuchs 2007).

Monitoring of compliance and adherence to oral treatment

Among studies of curative intent treatment with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy for CRC, only one study (Lembersky 2006) reported monitoring of compliance and adherence to oral treatment.

Among studies of palliative intent treatment with chemotherapy for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC, 10 studies (Ahn 2003; Bajetta 1996; Douillard 2002; Douillard 2014; Ducreux 2011; Martoni 2006; Rothenberg 2008; Schilsky 2002a; Seymour 2011; Shigeta 2016) described oral chemotherapy pill monitoring or use of a patient diary.

Outcomes

Patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy

Of the nine studies, all but one study assessed DFS. Kim 2001a examined rates of local and systemic recurrence but did not report DFS. Although De la Torre 2008 examined DFS, we did not include this study in the DFS meta‐analysis owing to insufficient median follow‐up time (22 months) (Table 3).

All of the studies apart from Kim 2001a reported the OS outcome. We excluded De la Torre 2008 from the meta‐analysis of OS owing to insufficient follow‐up time (Appendix 5).

All of the studies reported outcome data for at least one specific grade ≥ 3 AE of interest for this review, and all provided data that were suitable for meta‐analysis. Included studies reported information for specific grade ≥ 3 AEs: diarrhoea (n = 9), HFS (n = 7), neutropenia/granulocytopenia (n = 7), febrile neutropenia (n = 4), vomiting (n = 8), nausea (n = 7), stomatitis (n = 5), mucositis (n = 4), and hyperbilirubinaemia (n = 4). Two studies of adjuvant treatment (Hofheinz 2012; Kim 2001a) described 'lowered leucocytes' or 'leukopenia' only and were excluded from the meta‐analysis (Appendix 6). One study (Twelves 2012) reported combined data for grade ≥ 3 vomiting and nausea, and one study (De la Torre 2008) reported combined data for grade ≥ 3 stomatitis and mucositis. Table 6 shows the relationships between reported AEs and treatment for the included studies. Included studies used the following AE assessment criteria: ECOG CTC (n = 1), NCI CTCAE version 4.0 (n = 1), NCI CTCAE version 3.0 (n = 1), NCI CTCAE version 2.0 (n = 3), NCIC‐CTG CTC 1991 version (n = 1), NCI CTC 1958 (n = 1), and WHO, version not specified (n = 1).

4. Grade ≥ 3 adverse events ‐ Reported relationships to treatment in different studies.

| Setting | Related | Related and unrelated | Not specified |

| Patients treated with curative intent for CRC with neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy |

Twelves 2012 | De Gramont 2012 |

Allegra 2015 De la Torre 2008 Hofheinz 2012 Kim 2001a Lembersky 2006 Pectasides 2015 Shimada 2014 |

| Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with chemotherapy |

Ahn 2003 ECOG E5296 2012 Fuchs 2007 Hoff 2001 Nogue 2005 Schilsky 2002a Seymour 2011 Souglakos 2012 Van Cutsem 2001a Van Cutsem 2001b Yamazaki 2015 |

Cassidy 2011a Douillard 2014 Hochster TREE‐1 2008 Hochster TREE‐2 2008 Kato 2012 Rothenberg 2008 Shigeta 2016 Yamada 2013 Yasui 2015 |

Bajetta 1996 Carmichael 2002 Comella 2009 De la Torre 2008 Diaz‐Rubio 2007 Douillard 2002 Ducreux 2011 Ducreux 2013 Kohne 2008 Martoni 2006 Pectasides 2012 Porschen 2007 Silvestris 2010 Yu 2005 |

CRC: colorectal cancer

Overall, five studies presented data for 'any grade ≥ 3 AEs' (Allegra 2015; De Gramont 2012; Hofheinz 2012; Lembersky 2006; Twelves 2012).

Patients treated with palliative intent for inoperable advanced or metastatic CRC with palliative chemotherapy

Of the 35 studies, all but one study contributed to pooled effect estimates for an efficacy outcome and/or at least one grade ≥ 3 AE outcome (Silvestris 2010).

A total of 25 studies assessed PFS, and eight studies assessed the TTP outcome. Andersen 1987 did not assess either outcome. Hochster TREE‐1 2008, Hochster TREE‐2 2008, Hoff 2001, and Van Cutsem 2001b described TTP as the outcome examined but provided a definition compatible with the definition for PFS provided in this review. Bajetta 1996 stated that time to treatment failure was the examined outcome but provided a definition compatible with the definition for PFS provided in this review. Ahn 2003 described PFS as the examined outcome but provided a definition compatible with the classification for TTP provided in this review. We excluded Hochster TREE‐1 2008 and Hochster TREE‐2 2008 (for the PFS endpoint) and Silvestris 2010 and Yu 2005 (for the TTP endpoint) from our meta‐analyses because we could not estimate the HRs either directly or indirectly from the information provided (Appendix 7). Douillard 2002 presented only median TTP times with a stratified log‐rank P value.

Thirty‐one studies reported the OS outcome. Kato 2012, Martoni 2006, Mei 2014, and Silvestris 2010 did not report the OS outcome, and we excluded Andersen 1987 and Yu 2005 from our quantitative synthesis because we could not estimate the HR either directly or indirectly from the report (Appendix 7).

All 35 studies assessed ORR using the following criteria: WHO 1979 (n = 3), WHO 1981 (n = 4), modified WHO (n = 2), RECIST, version 1.0 (n = 21), RECIST, version not specified (n = 1), ECOG (n = 1), and SWOG (n = 1). Two studies did not specify this information (Van Cutsem 2001a; Yu 2005). We excluded Mei 2014 and Seymour 2011 from meta‐analysis because investigators reported ORR only after two cycles of chemotherapy and at 12 to 14 weeks after the start of treatment, respectively. We excluded Silvestris 2010 because investigators assessed an unclear number of participants for ORR in both arms (Appendix 7). Of the 32 studies included in the meta‐analysis, 22 studies provided information on the number of participants assessable or evaluable for response. One study did not specify a separate ORR analysis population denominator (Van Cutsem 2001a).