Abstract

Background

There is inconclusive evidence from observational studies to suggest that people who eat a diet rich in antioxidant vitamins (carotenoids, vitamins C, and E) or minerals (selenium and zinc) may be less likely to develop age‐related macular degeneration (AMD).

Objectives

To determine whether or not taking antioxidant vitamin or mineral supplements, or both, prevent the development of AMD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) (2017, Issue 2), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 29 March 2017), Embase Ovid (1947 to 29 March 2017), AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) (1985 to 29 March 2017), OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) (www.opengrey.eu/); searched 29 March 2017, the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch); searched 29 March 2017, ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov); searched 29 March 2017 and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en); searched 29 March 2017. We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing an antioxidant vitamin or mineral supplement (alone or in combination) to control.

Data collection and analysis

Both review authors independently assessed risk of bias in the included studies and extracted data. One author entered data into RevMan 5; the other author checked the data entry. We pooled data using a fixed‐effect model. We graded the certainty of the evidence using GRADE.

Main results

We included a total of five RCTs in this review with data available for 76,756 people. The trials were conducted in Australia, Finland, and the USA, and investigated vitamin C, vitamin E, beta‐carotene, and multivitamin supplements. All trials were judged to be at low risk of bias.

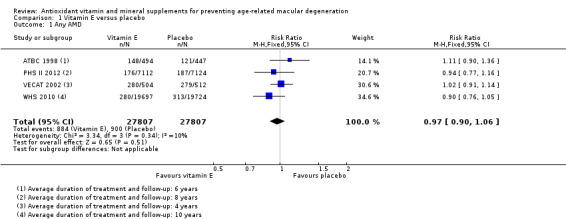

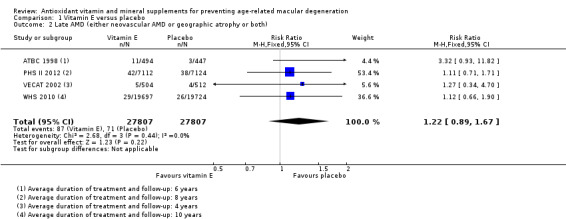

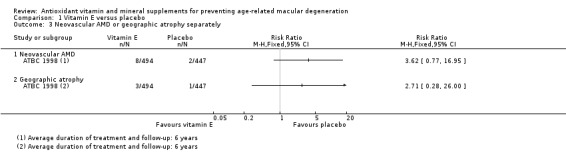

Four studies reported the comparison of vitamin E with placebo. Average treatment and follow‐up duration ranged from 4 to 10 years. Data were available for a total of 55,614 participants. There was evidence that vitamin E supplements do not prevent the development of any AMD (risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.90 to 1.06; high‐certainty evidence), and may slightly increase the risk of late AMD (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.67; moderate‐certainty evidence) compared with placebo. Only one study (941 participants) reported data separately for neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy. There were 10 cases of neovascular AMD (RR 3.62, 95% CI 0.77 to 16.95; very low‐certainty evidence), and four cases of geographic atrophy (RR 2.71, 95% CI 0.28 to 26.0; very low‐certainty evidence). Two trials reported similar numbers of adverse events in the vitamin E and placebo groups. Another trial reported excess of haemorrhagic strokes in the vitamin E group (39 versus 23 events, hazard ratio 1.74, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.91, low‐certainty evidence).

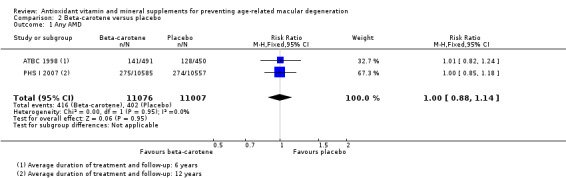

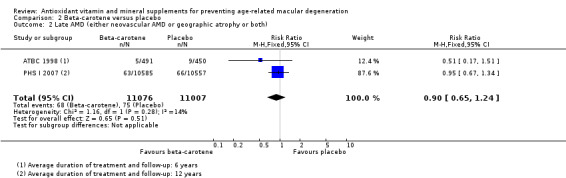

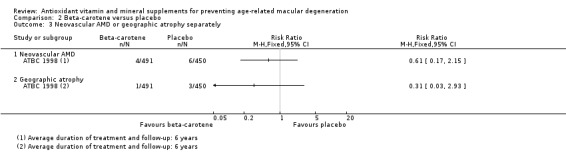

Two studies reported the comparison of beta‐carotene with placebo. These studies took place in Finland and the USA. Both trials enrolled men only. Average treatment and follow‐up duration was 6 years and 12 years. Data were available for a total of 22,083 participants. There was evidence that beta‐carotene supplements did not prevent any AMD (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.14; high‐certainty evidence) nor have an important effect on late AMD (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.24; moderate‐certainty evidence). Only one study (941 participants) reported data separately for neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy. There were 10 cases of neovascular AMD (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.15; very low‐certainty evidence) and 4 cases of geographic atrophy (RR 0.31 95% CI 0.03 to 2.93; very low‐certainty evidence). Beta‐carotene was associated with increased risk of lung cancer in people who smoked.

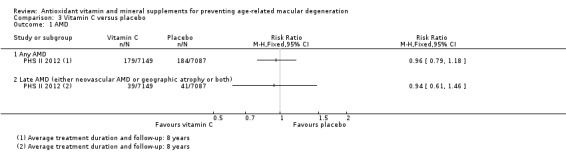

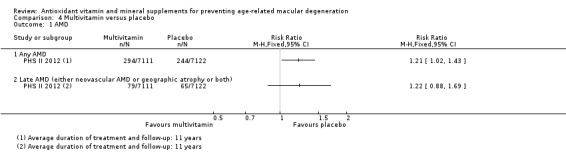

One study reported the comparison of vitamin C with placebo, and multivitamin (Centrum Silver) versus placebo. This was a study in men in the USA with average treatment duration and follow‐up of 8 years for vitamin C and 11 years for multivitamin. Data were available for a total of 14,236 participants. AMD was assessed by self‐report followed by medical record review. There was evidence that vitamin C supplementation did not prevent any AMD (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.18; high‐certainty evidence) or late AMD (RR 0.94, 0.61 to 1.46; moderate‐certainty evidence). There was a slight increased risk of any AMD (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.43; moderate‐certainty evidence) and late AMD (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.69; moderate‐certainty evidence) in the multivitamin group. Neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy were not reported separately. Adverse effects were not reported but there was possible increased risk of skin rashes in the multivitamin group.

Adverse effects were not consistently reported in these eye studies, but there is evidence from other large studies that beta‐carotene increases the risk of lung cancer in people who smoke or who have been exposed to asbestos.

None of the studies reported quality of life or resource use and costs.

Authors' conclusions

Taking vitamin E or beta‐carotene supplements will not prevent or delay the onset of AMD. The same probably applies to vitamin C and the multivitamin (Centrum Silver) investigated in the one trial reported to date. There is no evidence with respect to other antioxidant supplements, such as lutein and zeaxanthin. Although generally regarded as safe, vitamin supplements may have harmful effects, and clear evidence of benefit is needed before they can be recommended. People with AMD should see the related Cochrane Review on antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of AMD, written by the same review team.

Plain language summary

Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements to prevent the development of age‐related macular degeneration (AMD)

What is the aim of this review? The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out whether taking antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements prevents the development of AMD. Cochrane researchers collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and found five studies.

Key messages Taking vitamin E or beta‐carotene supplements will not prevent the onset of AMD in people who do not have signs of the condition. The same probably applies to vitamin C and multivitamin tablets. There is no evidence for other supplements, such as lutein and zeaxanthin.

What was studied in the review? AMD is a condition of the central area (macula) of the back of the eye (retina). The macula degenerates with age. In some people, this deterioration happens more quickly, and is associated with a particular appearance at the back of the eye. In its earliest stage (early AMD), yellow spots (drusen) can be seen under the retina by an eye health professional on examining the eye. The affected person will probably be unaware that they have a problem. As AMD progresses, it can lead to the loss of the cells in the back of the eye, which are needed for vision. This is known as geographic atrophy. Sometimes, new (harmful) blood vessels grow in the macula. These new blood vessels may bleed and cause scarring. This is known as neovascular or wet AMD. Any damage to the macula can affect vision, particularly central vision. Neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy are known as late AMD.

It is possible that antioxidant vitamins may help to protect the macula against this deterioration and loss of vision. Vitamin C, E, beta‐carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, and zinc are examples of antioxidant vitamins commonly found in vitamin supplements.

The Cochrane researchers only looked at the effects of these supplements in healthy people in the general population who did not yet have AMD. There is another Cochrane Review on the effects of these supplements in people who already have AMD.

What are the main results of the review? The Cochrane researchers found five relevant studies. The studies were large and included a total of 76,756 people. They took place in Australia, Finland, and the USA. The studies compared vitamin C, vitamin E, beta‐carotene, and multivitamin supplements with placebo.

The review showed that, compared with taking a placebo:

∙ Taking vitamin E supplements made little or no difference to the chances of developing AMD (high‐certainty evidence). ∙ Taking vitamin E supplements made little difference, or slightly increased, the chances of developing late AMD (moderate‐certainty evidence). ∙ Taking beta‐carotene made little or no difference to the chances of developing any AMD (high‐certainty evidence) or late AMD (moderate‐certainty evidence). ∙ Taking vitamin C made little or no difference to the chances of developing any AMD (high‐certainty evidence) or late AMD (moderate‐certainty evidence). ∙ Taking multivitamin tablets may slightly increase the chances of developing any AMD or late AMD (moderate‐certainty evidence). ∙ Adverse effects were not consistently reported in these eye studies, but there is evidence from other large studies that beta‐carotene increases the risk of lung cancer in people who smoke, or who have been exposed to asbestos.

None of the studies reported quality of life or resource use and costs.

How up‐to‐date is this review? The Cochrane researchers searched for studies that had been published up to 29 March 2017.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Vitamin E versus placebo.

| Vitamin E versus placebo | ||||||

| Patient or population: general population Setting: community Intervention: vitamin E* Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo** | Risk with vitamin E | |||||

| Any AMD | 150 per 1000 | 146 per 1000 (135 to 159) | RR 0.97 (0.90 to 1.06) | 55,614 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up ranged from 4 years to 10 years |

| Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both) | 5 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (4 to 8) | RR 1.22 (0.89 to 1.67) | 55,614 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up ranged from 4 years to 10 years |

| Neovascular AMD | 3 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (2 to 51) | RR 3.62 (0.77 to 16.95) | 941 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 6 years |

| Geographic atrophy | 2 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (1 to 57) | RR 2.71 (0.28 to 26.00) | 941 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 6 years |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Adverse effects (AE) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3 | Two trials reported similar numbers of AEs in vitamin E and placebo group. Another trial reported excess of haemorrhagic strokes in vitamin E group (39 vs 23 events, hazard ratio 1.74, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.91). |

| Resource use and costs | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| * Dose of vitamin E used in studies were: 50 mg/day, 400 IU/alternate days, 600 IU/alternate days, and 500 IU/day **The risk in the placebo group is the median risk in the placebo groups in the included studies. The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals i.e. are below 0.8 or above 1.25.

2 Downgraded one level for indirectness (only one trial in male smokers) and downgraded two levels for imprecision as very few cases (10 neovascular AMD, 4 geographic atrophy)

3 Downgraded one level for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals and lower confidence near 1 and downgraded one level for inconsistency as effect only reported by one trial.

Summary of findings 2. Beta‐carotene versus placebo.

| Beta‐carotene versus placebo | ||||||

| Patient or population: general population Setting: community Intervention: beta‐carotene* Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo** | Risk with beta‐carotene | |||||

| Any AMD | 150 per 1000 | 150 per 1000 (132 to 171) | RR 1.00 (0.88 to 1.14) | 22,083 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 6 years in one study and 12 years in the other study |

| Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both) | 5 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (3 to 6) | RR 0.90 (0.65 to 1.24) | 22,083 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 6 years in one study and 12 years in the other study |

| Neovascular AMD | 3 per 1000 | 2 per 1000 (1 to 6) | RR 0.61 (0.17 to 2.15) | 941 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 6 years |

| Geographic atrophy | 2 per 1000 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 6) | RR 0.31 (0.03 to 2.93) | 941 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 6 years |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Adverse effects | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Beta‐carotene associated with increased risk of lung cancer in people who smoke. | |

| Resource use and costs | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| * Dose of beta‐carotene used was 20 mg/day in one study and 50 mg/alternate days in the other study. **The risk in the placebo group is the median risk in the control groups of the four included studies in Table 1. The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals i.e. are below 0.8 or above 1.25.

2 Downgraded one level for indirectness (only one trial in male smokers) and downgraded two levels for imprecision as very few cases (10 neovascular AMD, 4 geographic atrophy)

Summary of findings 3. Vitamin C versus placebo.

| Vitamin C versus placebo | ||||||

| Patient or population: general population Setting: community Intervention: vitamin C* Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo** | Risk with vitamin C | |||||

| Any AMD | 150 per 1000 | 144 per 1000 (119 to 177) | RR 0.96 (0.79 to 1.18) | 14,236 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 8 years |

| Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both) | 5 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (3 to 7) | RR 0.94 (0.61 to 1.46) | 14,236 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 8 years |

| Neovascular AMD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Geographic atrophy | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Adverse effects | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None reported | |

| Resource use and costs | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| * Dose of vitamin C used was 500 mg/day. **The risk in the placebo group is the median risk in the control groups of the four included studies in Table 1. The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals i.e. are below 0.8 or above 1.25.

Summary of findings 4. Multivitamin versus placebo.

| Multivitamin versus placebo for preventing AMD | ||||||

| Patient or population: general population Setting: community Intervention: multivitamin* Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo** | Risk with multivitamin | |||||

| Any AMD | 150 per 1000 | 182 per 1000 (153 to 215) | RR 1.21 (1.02 to 1.43) | 14,233 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 11 years |

| Late AMD | 5 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (4 to 8) | RR 1.22 (0.88 to 1.69) | 14,233 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Average duration of treatment and follow‐up was 11 years |

| Neovascular AMD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Geographic atrophy | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Adverse effects | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | "Those taking the active versus placebo multivitamin were more likely to have skin rashes (2111 and 1973 men in corresponding active and placebo multivitamin groups; HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.15; P = 0.016)". PHS II |

| Resource use and costs | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| * Multivitamin used was Centrum Silver (zinc 15 mg, vitamin E 45 IU, vitamin C 60 mg, beta‐carotene 5000 IU vitamin A, 20% as beta carotene, folic acid 2.5 mg, vitamin B6 50 mg, vitamin B12 1 mg) **The risk in the placebo group is the median risk in the control groups of the four included studies in Table 1. The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for imprecision

Background

Description of the condition

Age‐related macular degeneration (AMD) is a disease affecting the central area of the retina (macula). In the early stages of the disease, lipid material accumulates in deposits underneath the retinal pigment epithelium. These deposits are known as drusen, and can be seen as pale yellow spots on the retina. The pigment of the retinal pigment epithelium may become disturbed, with areas of hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation. In the later stages of the disease, the retinal pigment epithelium may atrophy completely. This loss can occur in small focal areas or be widespread (geographic). In some cases, new blood vessels grow under the retinal pigment epithelium, and occasionally, into the subretinal space (exudative or neovascular AMD). Haemorrhage can occur, which often results in increased scarring of the retina.

The early stages of the disease are, in general, asymptomatic. In the later stages, there may be considerable distortion within the central visual field, leading to a complete loss of central visual function.

Population‐based studies suggest that, in people 65 years and older, approximately 5% have advanced AMD (Owen 2012). It is the most common cause of blindness and visual impairment in industrialised countries. In the UK, for example, over 30,000 people are registered as blind or partially sighted annually, half of whom have lost their vision due to macular degeneration (Bunce 2006).

Description of the intervention

Photoreceptors in the retina are subject to oxidative stress throughout life, due to combined exposures to light and oxygen. It has been proposed that antioxidants may prevent cellular damage in the retina by reacting with free radicals produced in the process of light absorption (Christen 1996).

There are a number of non‐experimental studies that have examined the possible association between antioxidant micronutrients and AMD, although few studies have examined supplementation specifically (Chong 2007; Evans 2001). Data on vitamin intake in observational studies should be considered cautiously, as people who have a diet rich in antioxidant vitamins and minerals, or who choose to take supplements regularly, are different in many ways from those who do not; these differences may not be adequately controlled by statistical analysis. The results of these observational studies have been inconclusive.

How the intervention might work

The underlying theory is that antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements will protect the retina against oxidative stress, and that this protection will delay the onset of AMD.

Why it is important to do this review

Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements are increasingly being marketed for use in age‐related eye disease, including AMD. The aim of this review was to examine the evidence on whether taking vitamin or mineral supplements prevents the development of AMD. See also the related Cochrane Review on antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of AMD, which considered whether supplementation for people with AMD slowed down the progression of the disease (Evans 2017).

Objectives

To determine whether or not taking antioxidant vitamin or mineral supplements, or both, prevent the development of AMD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared antioxidant vitamin or mineral supplements, (alone or in combination) with control (placebo or no treatment).

Types of participants

Participants in the trials were people in the general population, with or without diseases other than AMD. We excluded trials in which the participants were exclusively people with AMD. These trials were considered in a separate Cochrane Review that examined the effect of supplementation on progression of the disease (Evans 2017).

Types of interventions

We defined antioxidants as any vitamin or mineral that was known to have antioxidant properties in vivo or which was known to be an important component of an antioxidant enzyme present in the retina. We considered the following: vitamin C, vitamin E, carotenoids (including the macula pigment carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin), selenium and zinc.

Types of outcome measures

We modified our protocol for the current update (2017) to include outcomes specified by the UK NICE macular degeneration guideline panel (NICE 2016) ‐ see Differences between protocol and review.

We considered the following outcomes:

Development of:

any AMD (early or late AMD, or both)

late AMD (neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy, or both)

neovascular AMD

geographic atrophy

Quality of life

Resource use and costs

Follow‐up:

We considered the maximum follow‐up identified in the studies.

Adverse effects

We considered any adverse effects reported by the included studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language or publication year restrictions. The date of the search was 29 March 2017.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 2) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 29 March 2017) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 29 March 2017) (Appendix 2);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 29 March 2017) (Appendix 3);

AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) (1985 to 29 March 2017) (Appendix 4);

OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) (www.opengrey.eu/; searched 29 March 2017) (Appendix 5);

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch; searched 29 March 2017) (Appendix 6);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 29 March 2017) (Appendix 7);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 29 March 2017) (Appendix 8).

For the 2012 and 2017 updates, we specifically looked for adverse effects, using a simple search aimed to identify systematic reviews of adverse effects of vitamin supplements, see Appendix 9 for search strategy.

Searching other resources

We searched the Science Citation Index and the reference lists of reports of trials that were selected for inclusion. We contacted the investigators of included and excluded trials to ask if they knew of any other relevant published or unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Our initial searches identified all trials of antioxidant supplements, and therefore, generated many citations. Each review author independently assessed half of the titles and abstracts resulting from the searches, and selected studies according to the definitions in the Criteria for considering studies for this review. To check that we were consistent, we both assessed a subset of 100 records and compared results. We obtained full copies of all reports referring to controlled trials that definitely or potentially met the inclusion criteria. We assessed the full copies and selected studies according to the inclusion criteria. We wrote to authors of trials for which there were no published outcome data on AMD, to ask whether they had collected any data on eye disease outcomes.

As none of the trial authors responded positively, i.e. gave us unpublished data on AMD, for further updates of this review we only considered trials with published data on AMD.

In updates to this review, both authors independently went through the titles and abstracts resulting from the searches, and resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data using methods' forms developed by Cochrane Eyes and Vision (eyes.cochrane.org/resources‐review‐authors). We independently extracted data, and resolved disagreements by discussion. One author cut and pasted the data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 5 2014), and the other author checked that this had been done correctly.

For the 2017 update, we screened and extracted data using web‐based review management software (Covidence 2015).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both authors independently assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias, as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion. The review authors were not masked to any trial details.

Measures of treatment effect

Our measure of treatment effect was the risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and the mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes. Currently the review only includes analysis of dichotomous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

By definition, the interventions were applied to the person, but as most people have two eyes, trials can analyse data from one or both eyes. In all the trials included in this review the unit of analysis was the person and severity was classified for the worse eye.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot, the Chi² test for heterogeneity and the I² statistic.

Data synthesis

Where appropriate, we pooled data using a fixed‐effect model, after testing for heterogeneity between trial results using a standard Chi² test.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not plan any subgroup analyses. Only five trials are included at present, which means that it is not possible to formally investigate heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We had planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of study quality on effect size. Currently there are only high‐quality trials included in the review, and therefore, this is not relevant at present.

'Summary of findings' tables

We prepared separate 'Summary of findings' tables for the different types of vitamin supplement, i.e. vitamin C, vitamin E, beta‐carotene, and multivitamin.

We assessed the certainty of the evidence (GRADE) for each outcome using customised software (GRADEpro 2014). JE did the initial assessment, which was checked by JL. We considered risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias when judging the certainty of the evidence (Schünemann 2011).

The 'Summary of findings' tables include an estimate of the risk of each outcome in the general population. We derived these from the median risk in the placebo group in four of the studies included in the review (ATBC 1998; PHS II 2012; VECAT 2002; WHS 2010). As there was overlap in participants between PHS I 2007 and PHS II 2012, we just used data from PHS II 2012 for this estimate.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The initial searches resulted in 3178 titles and abstracts. Of these, 208 were potentially eligible trials reports. From these reports, we identified seven primary prevention trials of antioxidant vitamin or mineral supplements (ATBC 1994; CARET 1996; De Klerk 1998; LINXIAN 1993; Nambour 1995; PHS I 2007; WHS 2010). Investigators from three trials have confirmed that they did not collect data on AMD (CARET 1996; De Klerk 1998; Nambour 1995). We excluded these trials from the review. We did not receive a response from one trial author; we excluded this trial (LINXIAN 1993). Three trials had published data on AMD outcomes; we included them in this review (ATBC 1994; PHS I 2007; WHS 2010). Search of the National Eye Institute Clinical Research register identified one further ongoing trial that was collecting information on AMD ‐ the Women's Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study (WACS). There are two trials that have recruited participants with and without AMD (AREDS 2001; VECAT 2002). We included VECAT 2002 in this review because 82% of participants did not have signs of AMD. We excluded AREDS 2001 because it did not include AMD outcomes for people without AMD at baseline; it is included in the Cochrane Review examining the effect of supplementation on progression of the disease (Evans 2017).

In our original search strategy, we identified all trials of antioxidant interventions and asked trialists if they had collected data on AMD. We wrote to the authors of 60 trials of antioxidant interventions in people with diseases other than AMD. We received 15 responses, and none had collected any relevant data. We included all 60 trials in the excluded studies section of this review. As this proved to be an inefficient way of identifying relevant trials, we included terms for AMD in subsequent searches. We found 367 reports of trials in May 2002, 343 in May 2005, and 64 reports in January 2006, but we did not identify any further trials that were relevant for this review. The results of the PHS I study were published in 2007.

We repeated the searches in August 2007, at which time we identified a total of 129 reports of studies. The Trial Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) scanned the search results and removed 84 references that were not relevant to the scope of the review. We screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining 45 references and obtained full‐text copies of four reports to assess for potential inclusion in the review. We identified one new report from the PHS I 2007 study to include in the review and excluded the three remaining studies. For reasons of exclusion, see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

An update search was done in January 2012 which yielded 477 titles and abstracts. The TSC scanned the search results and removed 206 references which were not relevant to the scope of the review. We screened the title and abstracts of the remaining 271 references. We rejected 267 abstracts as not eligible for inclusion in the review. We obtained full‐text copies of four reports for further examination. One new report from the WHS 2010 study has been included in the review and three other studies were excluded. For reasons of exclusion, see Characteristics of excluded studies.

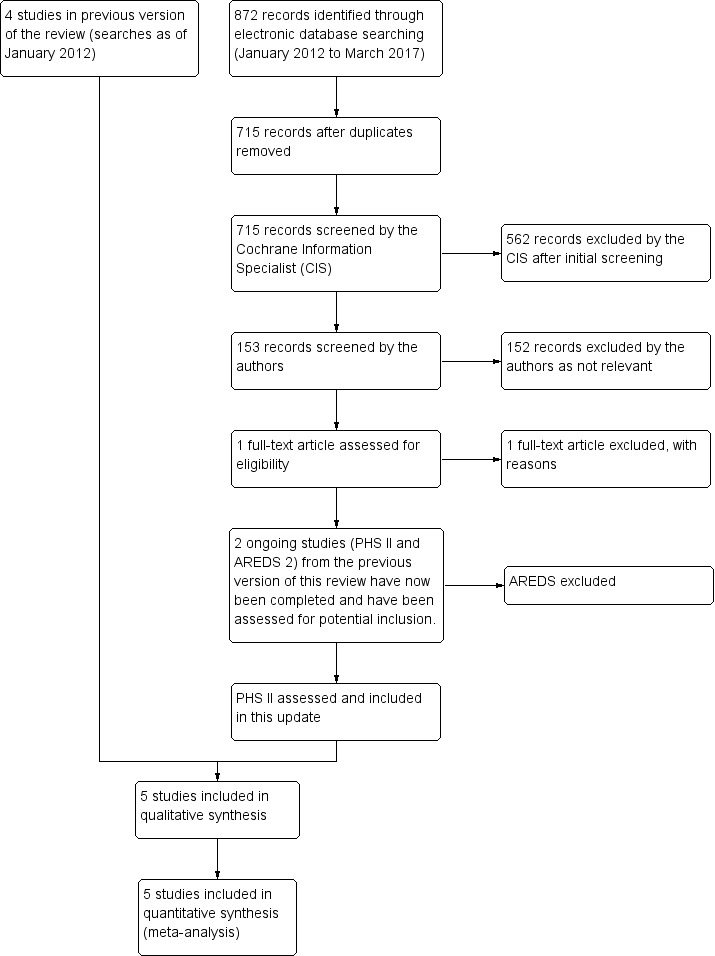

Update searches run in March 2017 yielded a further 872 records (Figure 1). After 157 duplicates were removed, the Cochrane Information Specialist (CIS; formerly the Trial Search Co‐ordinator) screened the remaining 715 records and removed 562 references that were not relevant to the scope of the review. We screened the remaining 153 references and obtained one full‐text report for further assessment, however, this study did not meet the inclusion criteria. We checked the status of the ongoing studies published in the previous version of this review. PHS II 2012 was now completed and we included it in this update. AREDS2 2008 was also completed, however, this study did not meet the inclusion criteria; see Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

See the 'Characteristics of included studies' table for more detailed information.

Types of participants

The studies took place in Australia, USA, and Finland. Three studies recruited men only (ATBC 1998; PHS I 2007; PHS II 2012), one study recruited women only (WHS 2010), and one study recruited both men and women (VECAT 2002). There was overlap of the participants in PHS I 2007 and PHS II 2012, as some participants in PHS II 2012 were recruited from PHS I 2007.

People taking part in the trials were identified from the general population. Participants in PHS I 2007 and PHS II 2012 were male physicians, and in WHS 2010 were female health professionals. In ATBC 1998, a random sample of 1035 men aged 65 years or older from the main study were invited to participate, with a response of 91% (941 men). In VECAT 2002, 18% of participants had AMD at baseline.

Types of intervention

In ATBC 1998, the groups received either alpha‐tocopherol 50 mg per day alone, beta‐carotene 20 mg per day alone, alpha‐tocopherol and beta‐carotene, or placebo. All formulations were coloured with quinoline yellow. Treatment duration was five to eight years (median 6.1 years). In VECAT 2002, participants were randomised to vitamin E (500 IU a day) or placebo. Supplementation continued for four years. In PHS I 2007, the groups received aspirin 325 mg every other day, beta‐carotene 50 mg every other day, aspirin and beta‐carotene, or placebo. Treatment duration averaged 12 years. In PHS II 2012, participants received vitamin C (500 mg daily), vitamin E (400 IU on alternate days), or daily multivitamin (Centrum Silver), or corresponding placebos. A beta‐carotene arm was discontinued in 2003, and results not reported. In WHS 2010, participants received vitamin E (600 IU on alternate days) or placebo, and were followed up for 10 years.

Types of outcome measures

In ATBC 1998, three photographs of each eye were taken with a Canon fundus camera at 40‐ and 60‐degree angles on Kodak Ektachrome 100 ASA slide film. These photographs were graded by one observer, masked to the participant's treatment group. The following grades of maculopathy were used: 0 = none; I = dry maculopathy with hard drusen, pigmentary changes, or both; II = soft macular drusen; III = disciform degeneration; IV = geographic atrophy.

In PHS I 2007, PHS II 2012, and WHS 2010, AMD was ascertained by self report: "Have you ever had macular degeneration diagnosed in your right or left eye?". If the participant answered yes to this question, permission was gained to contact their ophthalmologist or optometrist, and further details were obtained from the medical records.

In VECAT 2002, photographs were taken with a Nidek 3‐DX fundus camera on Kodachrome 64 ASA colour film. The photographs were graded at baseline independently by two trained graders. Early AMD (the primary outcome) was defined as soft drusen (distinct or indistinct) or pigmentary changes (hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation) on photographic grading. On clinical grading, this was large, soft drusen or non‐geographical retinal pigment epithelium atrophy. VECAT 2002 used Bailey‐Lovie visual acuity charts #4 and #5 (National Vision Research Institute, Australia).

Table 5 shows how the AMD outcome measures in the included studies were mapped onto the pre‐specified review outcomes.

1. Mapping the definition of AMD used in included studies to the review outcomes.

| Definition of AMD used in this review | Study | ||

| ATBC 1998 | PHS I 2007PHS II 2012; WHS 2010 | VECAT 2002 | |

| No AMD | 0 = no ARM | Did not self‐report or no signs listed below in medical records | ‐ |

| Any AMD | I = dry maculopathy, with hard drusen, pigmentary changes, or both II = soft macular drusen III = disciform degeneration IV = geographic atrophy. |

Drusen, RPE hypo or hyperpigmentation, geographic atrophy, RPE detachment, subretinal neovascular membrane, or disciform scar | Early AMD 1: Soft intermediate or soft distinct or soft indistinct or pigment changes (hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation) Early AMD 2: Soft intermediate or soft distinct or soft indistinct and pigment changes (hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation) Early AMD 3: Soft distinct or soft indistinct or pigment changes (hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation) Early AMD 4: Soft distinct or soft indistinct and pigment changes (hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation) Late AMD: Serous or haemorrhagic detachment of the RPE or sensory retina, characteristic haemorrhages, or subretinal fibrous scars, central areolar zone of retinal pigment epithelial atrophy with visible choroidal vessels, at least 175 µm in diameter |

| Late AMD | III = disciform degeneration IV = geographic atrophy. |

Geographic atrophy, RPE detachment, subretinal neovascular membrane, or disciform scar | Serous or haemorrhagic detachment of the RPE or sensory retina, characteristic haemorrhages, or subretinal fibrous scars, central areolar zone of retinal pigment epithelial atrophy with visible choroidal vessels, at least 175 µm in diameter |

| Neovascular AMD | III = disciform degeneration | RPE detachment, subretinal neovascular membrane, or disciform scar | Serous or haemorrhagic detachment of the RPE or sensory retina, characteristic haemorrhages, or subretinal fibrous scars |

| Geographic atrophy | IV = geographic atrophy. | Geographic atrophy | Central areolar zone of retinal pigment epithelial atrophy with visible choroidal vessels, at least 175 µm in diameter, in the absence of signs of neovascular AMD in the same eye |

RPE: retinal pigment epithelial Method of detection: Grading of fundus photographs (ATBC 1998; VECAT 2002), and medical record review after self‐report of AMD diagnosis (PHS I 2007; PHS II 2012; WHS 2010)

Excluded studies

See the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table for further information.

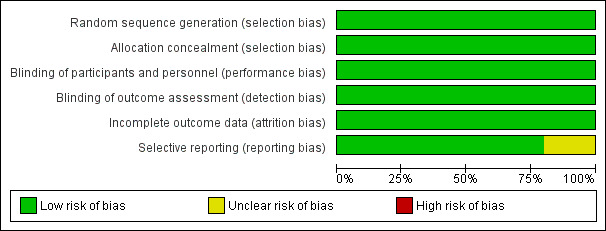

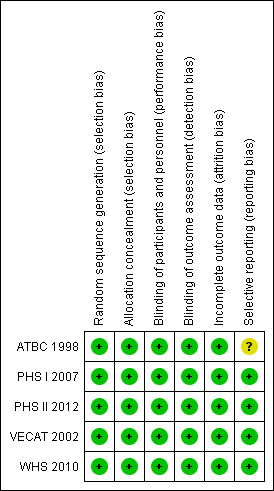

Risk of bias in included studies

We considered all five trials to be at low risk of bias (Figure 2; Figure 3). See 'Risk of bias' tables for each included study for details of the assessment.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

See Table 5 for details of how the AMD outcomes reported in the trials map to the review outcomes reported here. None of the studies reported quality of life or resource use and costs. For details of the GRADE assessments, see the 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4).

Vitamin E versus placebo

Four studies reported this comparison (ATBC 1998; PHS II 2012; VECAT 2002; WHS 2010). These studies took place in Australia (VECAT 2002), Finland (ATBC 1998), and USA (PHS II 2012; WHS 2010). Men (ATBC 1998; PHS II 2012), women (WHS 2010), or both (VECAT 2002) were enrolled. Average treatment and follow‐up duration ranged from 4 years (VECAT 2002) to 10 years (WHS 2010). Data were available for a total of 55,614 participants.

The risk ratio for any AMD was 0.97 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.06; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1) and for late AMD was 1.22 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.67; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vitamin E versus placebo, Outcome 1 Any AMD.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vitamin E versus placebo, Outcome 2 Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both).

Only one study (941 participants) reported data separately for neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy (ATBC 1998). There were 10 cases of neovascular AMD(RR 3.62, 9%% CI 0.77 to 16.95; very low‐certainty evidence) and four cases of geographic atrophy (RR 2.71, 95% CI 0.28 to 26.0; very low‐certainty evidence).

Beta‐carotene versus placebo

Two studies reported this comparison (ATBC 1998; PHS I 2007). These studies took place in Finland (ATBC 1998), and USA (PHS I 2007). Both trials enrolled men only. Average treatment and follow‐up duration was six years (ATBC 1998), and 12 years (PHS I 2007). Data were available for a total of 22,083 participants.

The risk ratio for any AMD was 1.00 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.14; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1), and 0.90 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.24; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.2) for late AMD.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Beta‐carotene versus placebo, Outcome 1 Any AMD.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Beta‐carotene versus placebo, Outcome 2 Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both).

Only one study (941 participants) reported data separately for neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy (ATBC 1998). There were 10 cases of neovascular AMD (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.15; very low‐certainty evidence) and four cases of geographic atrophy (RR 0.31 95% CI 0.03 to 2.93; very low‐certainty evidence).

Vitamin C versus placebo

One study reported this comparison (PHS II 2012). PHS II 2012 was a study on men in the USA, with average treatment duration and follow‐up of eight years. Data were available for a total of 14,236 participants.

The risk ratio (RR) for any AMD was 0.96 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.18; high‐certainty evidence) and for late AMD was 0.94 (0.61 to 1.46; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 3.1). The authors also reported similar hazard ratios (HR), which were adjusted for the other treatment assignments (vitamin E, beta‐carotene, and multivitamin treatment assignments). These HRs were 0.96 (0.78 to 1.18) for any AMD, and 0.94 (0.60 to 1.4) for late AMD.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin C versus placebo, Outcome 1 AMD.

Neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy were not reported separately.

Multivitamin versus placebo

One study reported this comparison (PHS II 2012). This study took place in the USA; they enrolled men only and followed them up for an average of 11 years. Data were available for a total of 14,233 participants.

The risk ratio for any AMD was 1.21 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.43; moderate‐certainty evidence), and 1.22 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.69; moderate certainty evidence; Analysis 4.1) for late AMD. The authors also reported HRs, which were adjusted for the cohort (PHS I and PHS II) and other treatment assignments (vitamin C, vitamin E, and beta‐carotene). These HRs were 1.22 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.44) for any AMD and 1.22 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.70) for late AMD.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Multivitamin versus placebo, Outcome 1 AMD.

Neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy were not reported separately.

Adverse effects

Included studies

In general, the publications that reported eye outcomes did not report adverse effects. We also looked at the reports of the main study results for those trials where eye outcomes were collected as part of a larger trial.

In VECAT 2002, it was noted that no serious adverse effects were seen. Similar numbers of people in the vitamin E and placebo groups withdrew due to adverse effects (four versus seven), reported any adverse effect (91 versus 83), or ocular adverse effect (105 versus 90).

The main ATBC 1998 trial found an increased risk of lung cancer associated with beta‐carotene supplementation (ATBC 1994), a finding that was repeated in the large CARET trial (Omenn 1996). Beta‐carotene supplementation is contra‐indicated in people who smoke or have been exposed to asbestos.

In the main WHS 2010 trial, "We examined whether vitamin E increased adverse effects due to bleeding (gastrointestinal bleeding, hematuria, easy bruising, epistaxis) because of the potential for vitamin E to inhibit platelet function, gastrointestinal symptoms (gastric upset, nausea, diarrhea, constipation), or fatigue. There were no differences between reported adverse effects for any of these variables among women in the two groups, apart from a small, but significant, increase in the risk of epistaxis (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.11; P = 0.02)" (Lee 2005).

In PHS II 2012, "An excess number of hemorrhagic strokes was observed among those assigned to vitamin E compared with placebo (39 versus 23 events; HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.91)" (Gaziano 2009), and"We observed no significant differences in adverse effects, including hematuria, easy bruising, and epistaxis, for active vitamin E or C compared with placebo"(Sesso 2008). For multivitamins "...no significant effects on gastrointestinal tract symptoms (peptic ulcer, constipation, diarrhea, gastritis, and nausea), fatigue, drowsiness, skin discoloration, and migraine (all P > 0.05). Those taking the active versus placebo multivitamin were more likely to have skin rashes (2111 and 1973 men in corresponding active and placebo multivitamin groups; HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.15; P = 0.016). In addition, there were inconsistent findings for daily multivitamin use on minor bleeding, with a reduction in hematuria (998 and 1105 men in corresponding active and placebo multivitamin groups; HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.97; P = 0.006), an increase in epistaxis (1216 and 1106 men in corresponding active and placebo multivitamin groups; HR 1.11, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.20; P = 0.016), and no effect on easy bruising/other bleeding (1927 and 1902 men in corresponding active and placebo multivitamin groups; HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.08; P = 0.59)" (Gaziano 2012).

Other systematic reviews

Reviews identified by the search in Appendix 9, for example, Huang 2006, did not identify any consistent adverse effects of mineral and vitamin supplements, but only included nine RCTs in their review. A subsequent Cochrane Review including 78 trials with 296,707 participants concluded "We found no evidence to support antioxidant supplements for primary or secondary prevention. Beta‐carotene and vitamin E seem to increase mortality, and so may higher doses of vitamin A" (Bjelakovic 2012).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review provides evidence that people who take vitamin E or beta‐carotene supplements do not reduce their risk of developing age‐related macular degeneration (AMD; Table 1; Table 2). There is more limited evidence on vitamin C (Table 3), and one multivitamin (Centrum Silver, Table 4), but at present, nothing to suggest that these supplements prevent AMD.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review includes five large, high‐quality studies that randomised over 75,000 members of the population to antioxidant supplementation or placebo. Duration of supplementation in these studies ranged from 4 to 12 years.

In ATBC 1994, there was no association with the treatment group and development of early stages of the disease. If anything, there was a tendency for more cases to be present in the treatment rather than the placebo group. This was not statistically significant. One drawback of adding a maculopathy study to a trial of primary prevention is that we have no information on maculopathy status before supplementation. Therefore, we have to assume that (1) maculopathy was equally distributed across study groups at the start of the study, and (2) most observed events occurred during the study period. It is likely that this was true for a reasonable proportion of the events, as the maculopathy study began eight years after recruitment for the main trial, and randomisation should have ensured equal distribution of maculopathy between the two groups.

Supplementation in this study began at age 50 to 69 years and lasted for five to eight years. Currently, we do not know at what age antioxidant protection may be important. It may be that this was too late or too short a period of supplementation to show an effect. This study was conducted in Finnish male smokers, and we have to be cautious in extrapolating the findings to other geographical areas, to people in other age groups, to women, and to non‐smokers. However, the incidence of AMD, particularly neovascular disease, is likely to be higher in smokers, which means that they provide a good population to demonstrate any potential protective effects of antioxidant supplementation (Klein 1993).

Similarly, the results of VECAT 2002 do not provide evidence of a benefit of supplementation in people with no, mild, or borderline AMD, although again, these studies have been underpowered to examine late‐stage disease.

In the PHS I 2007, over 20,000 physicians received supplementation with beta‐carotene over 12 years. There was little evidence of any benefit of beta‐carotene supplementation. They used medical record review to ascertain AMD, and therefore may have been less accurate. However, there was no reason to suppose that the ascertainment would have been different in the treatment and control groups. The same method of ascertainment was used in PHS II 2012 and WHS 2010.

This review does not provide evidence on the effects of other antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements on the development of AMD; in particular, it does not provide evidence on the effects of commonly marketed vitamin combinations.

There are additional ongoing studies, including the Women's antioxidant cardiovascular study (WACS), and SELECT study that are collecting data on AMD outcomes.

Although generally regarded as safe, antioxidant supplements may have harmful effects. Our review does not provide a systematic review of all possible adverse effects of supplements, but does highlight the fact that beta‐carotene increases the risk of lung cancer and overall, there was some evidence of a small, increased risk of mortality in people who took beta‐carotene or vitamin E.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the certainty of the evidence was considered to be high for any AMD, moderate for late AMD (due to lower number of events), and very low for neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy, which were only reported disaggregated in one study.

Although the number of people randomised in these studies was large, there is still a degree of uncertainty in the pooled estimates. In the pooled analyses, the risk ratios were largely around the null value, or just above the null value.

Potential biases in the review process

We did not include the Age‐related Eye Disease Study in this review. However, there were 2180 people recruited with no, mild, or borderline AMD (AREDS 2001a). The study reported no benefit of the study treatment for these people, however, the number of events was small.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A review of observational prospective studies in 2007 found little evidence of a protective effect of dietary antioxidants (Chong 2007). The only dietary antioxidant for which a reduction was seen was vitamin E, in contrast to the evidence from the trials included in this review. It is possible that natural vitamin E from dietary sources rather than artificial supplements has different effects, or alternatively, high levels of dietary vitamin E might be a marker for other nutrients.

There are many reviews focusing on the role of antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements in people with AMD, but we have only identified one that considered specifically their role in healthy people (Zampatti 2014). The conclusions were similar to the current review that there is little evidence for any benefit in healthy people.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Taking vitamin E or beta‐carotene supplements will not prevent or delay the onset of AMD. The same probably applies to vitamin C and the multivitamin (Centrum Silver) investigated in the one trial reported to date. There is no evidence with respect to other antioxidant supplements, such as lutein and zeaxanthin.

Implications for research.

There are a number of unanswered questions in the prevention of AMD. The hypothesis that antioxidant micronutrients may protect against the disease is a reasonable one. We do not know at what stage the protective effect may be important, nor the potential interactions with genetic effects and other risk factors for the disease, such as smoking. The research to date suggests that vitamin supplements (at least those studied) do not prevent AMD. They do not provide conclusive evidence on safety. The small number of incident events in healthy people mean that any future trials need to be very large. Four large primary and secondary prevention trials in the field of cancer and cardiovascular disease have added an examination of eye disease. This would seem to be a cost‐effective way forward in research in this area.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 July 2017 | Amended | Minor amendment to the updated version of 2017: Cochrane Review Evans 2017 reference amended as updated version of this review published. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1997 Review first published: Issue 4, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 March 2017 | New search has been performed | Issue 7, 2017: Electronic searches were updated. |

| 29 March 2017 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Issue 7, 2017: One new trial (PHS II 2012), which has now been completed, was included in the review update. |

| 19 April 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | 2012, Issue 6: The author byline has changed. Katherine Henshaw has been replaced by a new author, John Lawrenson. |

| 19 April 2012 | New search has been performed | 2012, Issue 6: New searches yielded one new trial. New 'Risk of bias' grading and a 'Summary of findings' table have been included. |

| 28 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 8 November 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. 2008, Issue 1: The results for PHS I were included. AREDS was previously included in this review but as no numerical data were available from the study on prevention of AMD, it was excluded from the review. The results of AREDS are presented in the review 'Antioxidants for slowing down the progression of AMD'. |

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken in collaboration with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of NICE.

We are grateful to:

the Systematic Review Training Unit at the Institute of Child Health, London for advice on the protocol for this review;

all the trialists who responded to requests for information;

peer reviewers Andrew Ness and Usha Chakravarthy for comments on an earlier version of this review.

Carol Mccletchie OBE who reviewed and commented on the plain language summary from the consumer perspective.

We thank Katherine Henshaw who was an author on the original review. The Cochrane Eyes and Vision editorial team prepared and executed the electronic searches for this review. We are grateful to Anupa Shah and Iris Gordon for their assistance with the review process.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Macular Degeneration #2 MeSH descriptor Retinal Degeneration #3 MeSH descriptor Retinal Neovascularization #4 MeSH descriptor Choroidal Neovascularization #5 MeSH descriptor Macula Lutea #6 macula* near lutea* #7 (macula* or retina* or choroid*) near/4 degenerat* #8 (macula* or retina* or choroid*) near/4 neovascul* #9 maculopath* #10 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9) #11 MeSH descriptor Vitamins #12 vitamin* #13 MeSH descriptor Vitamin A #14 retinol* #15 MeSH descriptor beta Carotene #16 caroten* #17 MeSH descriptor Ascorbic Acid #18 ascorbic next acid #19 MeSH descriptor Vitamin E #20 MeSH descriptor alpha‐Tocopherol #21 alpha tocopherol* #22 MeSH descriptor Vitamin B 12 #23 cobalamin* #24 MeSH descriptor Antioxidants #25 antioxidant* or anti oxidant* #26 MeSH descriptor Carotenoids #27 carotenoid* #28 MeSH descriptor Zinc #29 zinc* #30 MeSH descriptor Riboflavin #31 riboflavin* #32 MeSH descriptor Selenium #33 selenium* #34 MeSH descriptor Lutein #35 lutein* #36 MeSH descriptor Xanthophylls #37 xanthophyll* #38 zeaxanthin* #39 (#11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24) #40 (#25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38) #41 (#39 OR #40) #42 (#10 AND #41)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE Ovid search strategy

1. exp clinical trial/ [publication type] 2. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 3. placebo.ab,ti. 4. dt.fs. 5. randomly.ab,ti. 6. trial.ab,ti. 7. groups.ab,ti. 8. or/1‐7 9. exp animals/ 10. exp humans/ 11. 9 not (9 and 10) 12. 8 not 11 13. exp macular degeneration/ 14. exp retinal degeneration/ 15. exp retinal neovascularization/ 16. exp choroidal neovascularization/ 17. exp macula lutea/ 18. maculopath$.tw. 19. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 degener$).tw. 20. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 neovasc$).tw. 21. (macula$ adj2 lutea).tw. 22. or/13‐21 23. exp vitamins/ 24. exp vitamin A/ 25. vitamin A.tw. 26. retinol$.tw. 27. exp beta carotene/ 28. caroten$.tw. 29. exp ascorbic acid/ 30. ascorbic acid$.tw. 31. vitamin C.tw. 32. exp Vitamin E/ 33. exp alpha tocopherol/ 34. alpha?tocopherol$.tw. 35. alpha tocopherol$.tw. 36. vitamin E.tw. 37. exp Vitamin B12/ 38. vitamin B12.tw. 39. cobalamin$.tw. 40. exp antioxidants/ 41. ((antioxidant$ or anti) adj1 oxidant$).tw. 42. exp carotenoids/ 43. carotenoid$.tw. 44. exp zinc/ 45. zinc$.tw. 46. exp riboflavin/ 47. riboflavin$.tw. 48. exp selenium/ 49. selenium$.tw. 50. exp lutein/ 51. lutein$.tw. 52. exp xanthophylls/ 53. xanthophyll.tw. 54. zeaxanthin$.tw. 55. or/23‐54 56. 22 and 55 57. 12 and 56

The search filter for trials at the beginning of the MEDLINE strategy is from the published paper by Glanville 2006.

Appendix 3. Embase Ovid search strategy

1. exp randomized controlled trial/ 2. exp randomization/ 3. exp double blind procedure/ 4. exp single blind procedure/ 5. random$.tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. (animal or animal experiment).sh. 8. human.sh. 9. 7 and 8 10. 7 not 9 11. 6 not 10 12. exp clinical trial/ 13. (clin$ adj3 trial$).tw. 14. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 15. exp placebo/ 16. placebo$.tw. 17. random$.tw. 18. exp experimental design/ 19. exp crossover procedure/ 20. exp control group/ 21. exp latin square design/ 22. or/12‐21 23. 22 not 10 24. 23 not 11 25. exp comparative study/ 26. exp evaluation/ 27. exp prospective study/ 28. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).tw. 29. or/25‐28 30. 29 not 10 31. 30 not (11 or 23) 32. 11 or 24 or 31 33. exp retina macula degeneration/ 34. exp retina degeneration/ 35. exp retina neovascularization/ 36. exp subretinal neovascularization/ 37. maculopath$.tw. 38. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 degener$).tw. 39. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 neovasc$).tw. 40. exp retina macula lutea/ 41. (macula$ adj2 lutea$).tw. 42. or/33‐41 43. exp vitamins/ 44. exp Retinol/ 45. vitamin A.tw. 46. retinol$.tw. 47. exp beta carotene/ 48. caroten$.tw. 49. exp ascorbic acid/ 50. ascorbic acid$.tw. 51. vitamin C.tw. 52. exp alpha tocopherol/ 53. alpha?tocopherol$.tw. 54. alpha tocopherol$.tw. 55. vitamin E.tw. 56. vitamin B12.tw. 57. exp cyanocobalamin/ 58. cobalamin$.tw. 59. exp antioxidants/ 60. ((antioxidant$ or anti) adj1 oxidant$).tw. 61. exp carotenoid/ 62. exp zinc/ 63. zinc$.tw. 64. exp riboflavin/ 65. riboflavin$.tw. 66. exp selenium/ 67. selenium$.tw. 68. exp zeaxanthin/ 69. zeaxanthin$.tw. 70. lutein$.tw. 71. xanthophyll.tw. 72. or/43‐71 73. 42 and 72 74. 32 and 73

Appendix 4. AMED Ovid search strategy

1. exp eye disease/ 2. exp vision disorders/ 3. exp retinal disease/ 4. maculopath$.tw. 5. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 degenerat$).tw. 6. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 neovasc$).tw. 7. or/1‐6 8. exp vitamins/ 9. vitamin A.tw. 10. retinol$.tw. 11. exp carotenoids/ 12. caroten$.tw. 13. exp ascorbic acid/ 14. ascorbic acid$.tw. 15. vitamin C.tw. 16. vitamin E.tw. 17. alpha tocopherol$.tw. 18. vitamin B12.tw. 19. cobalamin$.tw. 20. exp antioxidants/ 21. ((antioxidant$ or anti) adj1 oxidant$).tw. 22. zinc/ 23. zinc$.tw. 24. riboflavin$.tw. 25. selenium/ 26. selenium$.tw. 27. lutein$.tw. 28. xanthophylls.tw. 29. zeaxanthin$.tw. 30. or/8‐29 31. 7 and 30

Appendix 5. OpenGrey search strategy

(macular degeneration OR AMD) AND (antioxidant OR vitamin OR carotene OR selenium OR tocopherol)

Appendix 6. ISRCTN search strategy

(macular degeneration OR AMD) AND (antioxidant OR vitamin OR carotene OR selenium OR tocopherol)

Appendix 7. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

(Macular Degeneration OR AMD) AND (Antioxidant OR Vitamin OR Carotene OR Selenium OR Tocopherol)

Appendix 8. ICTRP search strategy

Macular Degeneration OR AMD = Condition AND Antioxidant OR Vitamin OR Carotene OR Selenium OR Tocopherol = Intervention

Appendix 9. MEDLINE Ovid adverse effects search strategy

1. exp retinal degeneration/ 2. retinal neovascularization/ 3. choroidal neovascularization/ 4. exp macula lutea/ 5. (macula$ adj2 lutea).tw. 6. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj4 degener$).tw. 7. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj4 neovasc$).tw. 8. (AMD or ARMD or CNV).tw. 9. maculopath$.tw. 10. or/1‐9 11. exp vitamins/ 12. vitamin A.tw. 13. retinol$.tw. 14. (caroten$ or betacaroten$).tw. 15. ascorbic acid$.tw. 16. vitamin C.tw. 17. alpha?tocopherol$.tw. 18. alpha tocopherol$.tw. 19. vitamin E.tw. 20. ((antioxidant$ or anti) adj1 oxidant$).tw. 21. zinc/ 22. zinc$.tw. 23. or/11‐22 24. 10 and 23 25. ae.fs. 26. 24 and 25 27. limit 26 to (meta analysis or randomized controlled trial or "review")

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Vitamin E versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Any AMD | 4 | 55614 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.90, 1.06] |

| 2 Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both) | 4 | 55614 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.89, 1.67] |

| 3 Neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy separately | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Neovascular AMD | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Geographic atrophy | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vitamin E versus placebo, Outcome 3 Neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy separately.

Comparison 2. Beta‐carotene versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Any AMD | 2 | 22083 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.88, 1.14] |

| 2 Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both) | 2 | 22083 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.65, 1.24] |

| 3 Neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy separately | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Neovascular AMD | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Geographic atrophy | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Beta‐carotene versus placebo, Outcome 3 Neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy separately.

Comparison 3. Vitamin C versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 AMD | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Any AMD | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 4. Multivitamin versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 AMD | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Any AMD | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Late AMD (either neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy or both) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

ATBC 1998.

| Methods | Method of allocation: random. Sponsor provided coded capsules. Masking: participant: yes; provider: yes; outcome: yes Exclusions after randomisation: no Losses to follow‐up: 31%. Random sample for maculopathy study: 9%. 2 x 2 factorial design. Maculopathy add‐on random sample in 2 regions. |

|

| Participants | Country: Finland Number of participants randomised: 29,133. Random sample of 1035 selected for maculopathy study. Age: 50 to 69 years in 1984. Maculopathy study 1992‐3 in people aged 65 plus. Sex: male Inclusion criteria: 5 or more cigarettes daily Exclusion criteria: history of cancer or serious disease limiting ability to participate; those taking supplements vitamin E, A, or beta‐carotene in excess of predefined doses; those treated with anticoagulants |

|

| Interventions | Intervention:

Comparator:

Duration: 5 to 8 years (median 6.1) |

|

| Outcomes | AMD: 4 grades:

Grade I: dry maculopathy with hard drusen, pigmentary changes, or both

Grade II: soft macular drusen

Grade III: disciform degeneration

Grade IV: geographic atrophy Quote "A person was considered to have ARM if he had a class I or higher change in either eye, and severity was classified according to the worst eye." |

|

| Notes | Compliance with treatment excellent; 4/5 active participants took more than 95% of scheduled capsules. Drop‐out rate and compliance similar between all 4 groups. Funding source: Quote "This study was supported by the Juho Vainio Foundation, Helsinki, Finland. The ATBC study was supported by Public Health Service Contract N01‐CN‐45165 from the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Cancer Institute of the United States." Declarations of interest: NR Date study conducted: Quote "The ophthalmological examination took place during their final follow‐up trial visit between December 1992 and March 1993" Trial id: NCT00342992 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "The participants were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups: AT alone, AT and BC, BC alone, or placebo in a complete 2 x 2 factorial design" and "Randomization was performed in blocks of eight within each of the study areas." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "A coded reserve supply of capsule packs..." Not clearly stated that allocation concealed, but the study was described as being "double‐blind" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Judgement comment: placebo‐controlled study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) AMD | Low risk | Quote "The retinal specialist [...] examined six photographs (three per eye) of each participant without knowledge of the subject's treatment group" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote "A total of 941 persons participated (91%) and non‐participation rates were similar across the intervention groups." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Visual acuity measured but not reported, but as the main results for AMD showed no difference between groups, it is not clear whether this was an example of selective reporting or whether, in fact, the investigators considered that visual acuity in this age group might be attributed to a variety of causes, and therefore, was not a relevant outcome. |

PHS I 2007.

| Methods | Method of allocation: coded tablets Masking: participant: yes; provider: yes; outcome: yes 99% follow‐up 2 x 2 factorial design. |

|

| Participants | Country: USA Number randomised: originally 22,071 men were randomised: 21,142 participants were followed up for at least 7 years and provided information on diagnoses of AMD made during the first 7 years of the trial Age: 40 to 84 years in 1982 Sex: male Inclusion criteria: physician aged 40 to 84 years in 1982 with no history of cancer, myocardial infarction, stroke, or transient cerebral ischaemia Exclusion criteria: personal history of cardiovascular disease or cancer; contraindications or current use of study medication; |

|

| Interventions | Intervention:

Comparator:

There was also an aspirin arm (2 x 2 factorial arm), which was terminated early (January 1988) Mean duration 12 years range (range 11.6 to 14.2 years) |

|

| Outcomes | Self report of AMD followed by medical record review and questionnaire to relevant ophthalmologist Primary endpoint: visually significant AMD, defined as a self‐report confirmed by medical record evidence of an initial diagnosis after randomisation, but before 31 December 1995, with a reduction in best‐corrected visual acuity to 20/30 or worse attributable to AMD Secondary endpoints: AMD with or without vision loss, composed of all incident cases; Advanced AMD, encompassed of cases of visually significant AMD with pathological signs of disciform scar, RPE detachment, geographic atrophy, or subretinal neovascular membrane Quote "Individuals, rather than eyes, were the unit of analysis because eyes were not examined independently, and participants were classified according to the status of the worse eye as defined by disease severity. When the worse eye was excluded because of visual acuity loss attributed to other ocular abnormalities the fellow eye was considered for classification." |

|

| Notes | Funding source: Quote "Supported by research grants HL 26490, HL 34595, CA 34944, CA 40360, and EY 06633 from the National Institutes of Health" Declarations of interest: NR Date study conducted: August 1985 (from clinicaltrials.gov) to December 1995 Trial id: NCT00000500 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "The PHS I was a randomised, double‐masked, placebo controlled trial..." "A total of 22,071 physicians were then randomised according to a two‐by‐two factorial design, with use of a computer‐generated list of random numbers..." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "The PHS I was a randomised, double‐masked, placebo controlled trial..." Judgement Comment: Although this aspect of the trial was not well described, the placebo control was described (placebo and supplement identical appearance and packaging) and the study was described as double‐blind |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote "The PHS I was a randomised, double‐masked, placebo controlled trial..." Judgement Comment: Although this aspect of the trial was not well described, the placebo control was described (placebo and supplement identical appearance and packaging) and the study was described as double‐blind |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) AMD | Low risk | Quote "The PHS I was a randomised, double‐masked, placebo controlled trial..." Judgement Comment: Although this aspect of the trial was not well described, the placebo control was described and the study was described as double‐blind. Diagnosis of AMD by self‐report based on health questionnaire (confirmed by ophthalmologist or optometrist). Patients and researchers unaware of intervention. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote "At the end of 11 years of follow‐up (the last year completed for all participants), 99.2% were still providing information on morbidity, and the follow‐up for mortality was 99.9% complete. Eighty percent of participants in the beta‐carotene group and in the placebo group were still taking the study pills, with a mean compliance among pill takers of more than 97%. Therefore, even after 11 years, 78% of the study pills assigned in the beta‐carotene group were reported as still being taken. In the placebo group, 6% of participants reported taking supplemental beta carotene or vitamin A." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Judgement comment: reported AMD outcomes as expected |

PHS II 2012.

| Methods | Method of allocation: coded tablets Masking: participant: yes; provider: yes; outcome: yes 95% follow‐up 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 factorial design. |

|

| Participants | Country: USA Number randomised: 14,236 with no diagnosis of AMD at baseline according to vitamin C/E paper; 14,233 with no diagnosis of AMD at baseline according to multivitamin paper. Average age: 64 years Sex: male Inclusion criteria: US male physicians; 50 years and older; participants in PHS I and new physician participants; willing to forego use of supplements for new trial; for new participants, do not report personal history of cancer (except non‐melanoma skin cancer). CVD, current liver disease, current renal disease, peptic ulcer or gout. Compliance with pill‐taking regimen in run‐in period. Exclusion criteria:History of cirrhosis; active liver disease in past six months; participants reporting cataract or AMD at baseline. |

|

| Interventions | Intervention:

Comparator:

Alternate day beta‐carotene (50 mg) component terminated in March 2003. Lutein (added to Centrum Silver during course of study (250 µg) and doses of other nutrients changed Follow‐up: the multivitamin component had a longer duration. "An average of 8 years of treatment and follow‐up" for vitamin E and vitamin C Median duration of treatment for multivitamin analyses 11.2 years, IQR 10.7 to 13.3 |

|

| Outcomes | Age‐related macular degeneration: reported diagnosis followed up by contact with treating ophthalmologist/optometrist Quote "We considered individuals, rather than eyes, as the unit of analysis and we classified individuals according to the status of the worse eye as defined by disease severity. When the worse eye was excluded because of visual acuity loss attributed to other ocular abnormalities, the fellow eye was considered for classification." |

|

| Notes | Funding source: Grants from National Eye Institute, National Institute on Ageing and the National Institutes of Health. BASF and DSM provided study agents and packaging. Declarations of interest: "The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any of the materials discussed in this article." Date study conducted: July 1997 to June 2011 (from clinicaltrials.gov) Trial id: NCT00270647 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote "Randomisation to the other agents, using a computer generated list of random numbers, will be stratified according to age" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Judgement comment: central randomisation |