Abstract

Background

There is increasing focus on providing high quality care for people at the end of life, irrespective of disease or cause, and in all settings. In the last ten years the use of care pathways to aid those treating patients at the end of life has become common worldwide. The use of the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) in the UK has been criticised. In England the LCP was the subject of an independent review, commissioned by a Health Minister. The resulting Neuberger Review acknowledged that the LCP was based on the sound ethical principles that provide the basis of good quality care for patients and families when implemented properly. It also found that the LCP often was not implemented properly, and had instead become a barrier to good care; it made over 40 recommendations, including education and training, research and development, access to specialist palliative care services, and the need to ensure care and compassion for all dying patients. In July 2013, the Department of Health released a statement that stated the use of the LCP should be "phased out over the next 6‐12 months and replaced with an individual approach to end of life care for each patient".

The impact of opioids was a particular concern because of their potential influence on consciousness, appetite and thirst in people near the end of life. There was concern that impaired patient consciousness may lead to an earlier death, and that effects of opioids on appetite and thirst may result in unnecessary suffering. This rapid review, commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research, used standard Cochrane methodology to examine adverse effects of morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, and codeine in cancer pain studies as a close approximation to possible effects in the dying patient.

Objectives

To determine the impact of opioid treatment on patient consciousness, appetite and thirst in randomised controlled trials of morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone or codeine for treating cancer pain.

Search methods

We assessed adverse event data reported in studies included in current Cochrane reviews of opioids for cancer pain: specifically morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, and codeine.

Selection criteria

We included randomised studies using multiple doses of four opioid drugs (morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, and codeine) in cancer pain. These were taken from four existing or ongoing Cochrane reviews. Participants were adults aged 18 and over. We included only full journal publication articles.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted adverse event data, and examined issues of study quality. The primary outcomes sought were numbers of participants experiencing adverse events of reduced consciousness, appetite, and thirst. Secondary outcomes were possible surrogate measures of the primary outcomes: delirium, dizziness, hallucinations, mood change and somnolence relating to patient consciousness, and nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea, dyspepsia, dysphagia, anorexia, asthenia, dehydration, or dry mouth relating to appetite or thirst.

Comparative measures of harm were known to be unlikely, and we therefore calculated the proportion of participants experiencing each of the adverse events of interest with each opioid, and for all four opioid drugs combined.

Main results

We included 77 studies with 5619 randomised participants. There was potential bias in most studies, with small size being the most common; individual treatment groups had fewer than 50 participants in 60 studies. Participants were relatively young, with mean age in the studies typically between 50 and 70 years. Multiple major problems with adverse event reporting were found, including failing to report adverse events in all participants who received medication, all adverse events experienced, how adverse events were collected, and not defining adverse event terminology or whether a reporting system was used.

Direct measures of patient consciousness, patient appetite, or thirst were not apparent. For opioids used to treat cancer pain adverse event incidence rates were 25% for constipation, 23% for somnolence, 21% for nausea, 17% for dry mouth, and 13% for vomiting, anorexia, and dizziness. Asthenia, diarrhoea, insomnia, mood change, hallucinations and dehydration occurred at incidence rates of 5% and below.

Authors' conclusions

We found no direct evidence that opioids affected patient consciousness, appetite or thirst when used to treat cancer pain. However, somnolence, dry mouth, and anorexia were common adverse events in people with cancer pain treated with morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, or codeine.

We are aware that there is an important literature concerning the problems that exist with adverse event measurement, reporting, and attribution. Together with the known complications concerning concomitant medication, data collection and reporting, and nomenclature, this means that these adverse events cannot always be attributed unequivocally to the use of opioids, and so they provide only a broad picture of adverse events with opioids in cancer pain. The research agenda includes developing definitions for adverse events that have a spectrum of severity or importance, and the development of appropriate measurement tools for recording such events to aid clinical practice and clinical research.

Plain language summary

Impact of morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone or codeine on patient consciousness, appetite and thirst when used to treat cancer pain

Description of the problem

Care pathways are packages of care designed to ensure that patients have appropriate and effective care in particular situations. Such pathways are commonly used, and often produce good results, but they can also be used as a tick box solution that acts as a barrier to good care. Care pathways have been used to ensure appropriate care for people who are dying in hospice settings.

The Liverpool Care Pathway was devised for use in hospices, and has been used in general hospital settings to care for dying patients. Its use has been criticised. A government review of the use of end‐of‐life care pathways in the NHS in the UK recommended they should not be used because they were being misused.

A concern, mainly raised by relatives, was that opioids were over‐prescribed, used to hasten death, to reduce consciousness, and diminish the patient's desire or ability to accept food or drink.

The purpose of this review

This Cochrane review was commissioned to look at harms (adverse events) associated with the use of opioids to treat cancer pain particularly relating to patient consciousness, appetite or thirst.

How the information was gathered

Ideally, when writing this review we would have looked at medical trials of opioid use in older people receiving end‐of‐life care, but there are no trials in this area. So, we looked at trials of people being treated with opioids for cancer pain, as the information these trials provide is likely to be the closest that is available to opioid use in end‐of‐life care ‐ although people treated for cancer pain are not usually at the end of their lives.

What we found

This review identified 77 studies with over 5,000 people who received various treatments. The population in these trials was mainly aged between 50 and 70 years. Trial quality was generally poor; particular problems included small study size, and not reporting adverse events in all patients, or all recorded adverse events. Known problems with adverse event measurement, recording, and reporting made assessment even more difficult.

For all four opioids together, 1 in 4 people experienced constipation and somnolence (sleepiness, drowsiness), 1 in 5 experienced nausea and dry mouth, and 1 in 8 experienced vomiting, loss of appetite, and dizziness. Weakness, diarrhoea, insomnia (difficulty in sleeping), mood change, hallucinations and dehydration occurred at rates of 1 in 20 people and below. These results may contribute to understanding the effects of opioids on consciousness, appetite, and thirst in end‐of‐life care in all patients deemed to be people who are dying.

Background

This review assesses the impact of four opioid drugs (morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, and codeine) on patient consciousness, appetite, and thirst in randomised controlled trials (RCT) in cancer‐related pain. It has been commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in the UK as a rapid review. The specific research question concerned the effects of opioids on level of consciousness, and inability of patients to eat and drink. It is recognised that participants with pain from cancer in these clinical trials are not the same as the (mostly older) people considered to be within a short time of dying, but it is the closest available randomised trial data set.

Description of the condition

Pain is often the first symptom causing someone to seek medical advice that eventually leads to a diagnosis of cancer; 30% to 50% of all people with cancer will experience moderate to severe pain (Portenoy 1999). For those with advanced cancer 75% to 90% will experience pain severe enough to have a major impact on daily living.

Description of the intervention

The four opioids chosen are those most commonly used to treat cancer‐related pain, and for which Cochrane reviews have either been published and updated or are near publication. As with all treatments, benefit and harm needs to be considered in making choices about the care of patients. Recently concern has been expressed about the adverse events associated with opioids, especially in terms of the impact on patient consciousness, appetite and thirst in people near the end of life. There is fear that impaired patient consciousness may lead to an earlier death, and that effects of opioids on appetite and thirst may result in unnecessary suffering (DH 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

There is increasing focus on providing high quality care for people at the end of life, irrespective of disease or cause, and in all settings. In the last ten years the use of care pathways to aid those treating patients at the end of life has become common worldwide (Bailey 2005; Bookbinder 2005; Ellershaw 2003), despite a lack of evidence from randomised trials (Chan 2013). A randomised comparison of the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) and usual care in cancer in hospital wards showed no difference in quality of care or survival times between them, though most outcomes were numerically superior in the LCP arm (Costantini 2014).

The pathways are intended to improve the care and dignity of those facing the last days of life, but questions around their use have been raised. In the UK, for example, criticisms emerged that the LCP was in fact leading to poor care, as reported in the media and confirmed in part by a review panel. A number of commentaries provide different perspectives on the background and future of care of the dying (Knights 2013; George 2014; Regnard 2014).

In response, the Minister of State for Care Services in England set up a panel with a wide‐ranging set of complementary interests and expertise in end‐of‐life care to review the use and experience of the LCP. This group, chaired by Baroness Julia Neuberger, published its report in July 2013 (DH 2013), recommending that the LCP be phased out and replaced by individualised end‐of‐life care plans. One key issue reported to the review body was that junior doctors felt that training was on how to fill in documents, rather than the principles of terminal care: how to care for the patient was becoming secondary to form filling.

Comments in the report (DH 2013) included:

‘The Review heard that, if a patient became more agitated or in greater pain as they died, they often became peaceful because the right drugs were given to them at the right time and in the right dose. But there were complaints that opiate pain killers and tranquillisers were being used inappropriately as soon as the LCP was initiated.’

‘At the end of life, a person may become overhydrated, and there is no moral or legal obligation to continue to administer and clinically assisted hydration or nutrition if they are having no beneficial effect. But there can be no clinical justification for denying a drink to a dying patient who wants one, unless doing so would cause them distress. In hospitals in particular, there appear to have been many instances demonstrating an inadequate understanding of the LCP’s direction on oral hydration. Refusing food and drink is a decision for the patient, not clinical staff, to make.’

Opioids are known both to have sedative properties and to have an impact on the gastrointestinal system. This review was commissioned by the NIHR to help answer one question raised by the review of the LCP, namely whether opioids given for relief of cancer pain have an adverse effect on patient consciousness, appetite, and thirst. The review will seek to quantify how often these symptoms or effects are reported in RCTs of four commonly‐used opioid drugs when used to treat cancer pain. This information may be directly relevant to patients in the last days or hours of life, or may highlight deficiencies in the available evidence and serve to direct further studies, or both.

Although the motivation for this review is firmly UK‐based, the LCPs are used worldwide, and the findings of the review are likely to be of value, or at least interest, outside the UK. In addition, while the Neuberger review raised over 40 different points relating to clinical practice and clinical research, the purpose of this review of opioid adverse events in treating cancer pain related only to one of those points.

Review limitations

It is important to acknowledge ab initio a major limitation of the review, namely whether an evaluation of RCTs is able to answer the question. RCTs typically exclude patients at the end of life in the last few weeks or days of life, and the review is predicated on the assumption that an evaluation of adverse events during a clinical trial in a selected, sometimes healthier patient sample, can provide relevant information about the nature of these side effects in dying patients. Any assumption that cancer studies may be extrapolated to all populations receiving end‐of‐life care is fundamentally speculative because the studies reviewed will not provide data from populations that possess the same type of physiological and functional disturbances, comorbidities, and concurrent treatments as the populations of dying people that are the reference group for the review.

The point of the review is to examine whether there is any available evidence on adverse events recorded in cancer pain studies that provides information relevant to end‐of‐life care, and for future research. The specific research question concerned the effects of opioids on level of consciousness, and inability of patients to eat and drink.

Objectives

To determine the impact of opioid treatment on patient consciousness, appetite and thirst in randomised controlled trials of morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone or codeine for treating cancer pain.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We assessed adverse event data reported in studies included in Cochrane reviews of opioids for cancer pain: morphine (Wiffen 2013), fentanyl (Hadley 2012), oxycodone (Schmidt‐Hansen 2010 together with the authors of an ongoing update, supplemented by additional searches), and a completed but unpublished review of codeine (Schremmer 2013 ‐ full review in press).

For inclusion in the individual reviews, studies were: RCTs using single or multiple doses, with parallel or cross‐over design, and of any duration. Studies that did not state that they were randomised were excluded, as were quasi‐randomised studies, studies with fewer than 10 participants (Moore 1998), and studies that did not deal with cancer‐related pain, or did not assess pain as an outcome measure. Studies reported only as short abstracts (usually from meetings) were not included because they contain insufficient information to assess methodological quality and risk of bias. For this review, single dose studies were excluded as they are less likely to give useful data on adverse events.

Types of participants

Our original intention was to include any relevant data from adults and children with cancer pain requiring treatment with opioids. However, as none of the Cochrane reviews identified any relevant studies in children (the oxycodone review looked only for studies in adults), this review was limited to adults.

Types of interventions

Morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, or codeine preparations compared with either placebo, an alternative formulation of morphine or an active control. Any route of administration was permitted, though morphine, codeine and oxycodone were likely to be used by the oral route of administration, while fentanyl was used in the form of transdermal patches.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes are numbers of participants experiencing adverse events of level of consciousness or inability to eat or drink.

Secondary surrogate outcomes included numbers of participants reporting:

delirium, dizziness, hallucinations, mood change, asthenia, and somnolence that may relate to patient consciousness;

nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea, dyspepsia, dysphagia, anorexia, dehydration, or dry mouth that may relate to appetite or thirst.

Where studies report these adverse effects, we looked to see if concomitant medication could also have contributed.

Search methods for identification of studies

Studies already identified and included in the four Cochrane reviews were considered. The codeine review (Schremmer 2013) was available as a protocol and the authors kindly provided access to their completed but unpublished review.The oxycodone review (Schmidt‐Hansen 2010) was in the process of updating, and again authors provided information about any additional studies. This was supplemented by a brief search of PubMed for any other additional studies of oxycodone as this review was not yet completed, and two additional studies were identified.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (PW, SD) independently screened and assessed papers retrieved from the four reviews. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with all authors.

Data extraction and management

Existing characteristics of included studies tables were imported and any further information on relevant outcomes was added.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We imported the risk of bias assessments for individual studies from the four included reviews and checked that they were correct and conformed to the most recent standards (AUREF 2012). We used the following standard parameters:

A 'Risk of bias' table was completed for each included study, using methods adapted from those described by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. Two authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) with any disagreements resolved by discussion. The following were assessed for each study:

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence as: low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator); unclear risk of bias: the trial may or may not be free of bias. Studies with high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number) were excluded.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). The method used to conceal allocation to interventions before assignment assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. The methods were assessed as: low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes); unclear risk of bias (methods not clearly stated). Studies with high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth) were excluded.

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). The methods used to blind study participants and outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received were assessed. Studies were considered at low risk of bias if they stated that they were blinded and described the method used to achieve blinding (e.g. identical tablets, matched in appearance and smell); at unknown risk if they state that they were blinded, but do not provide an adequate description of how it was achieved, and at high risk if they were single blind or open‐label studies.

Incomplete adverse event outcome data ‐ patient level. Studies were considered at low risk of bias if all participants who took the study medication were included. Where more than 10% of participants were not included in AE reports then these studies were considered to be high risk. Any thing else was considered to be unclear.

Selective reporting bias for adverse events. Studies were considered at low risk of bias if all adverse events were reported. Where there was clear evidence of partial reporting (e.g. most common or more than a given rate) then these studies were considered to be high risk. Anything else was considered to be unclear.

Size (checking for possible biases confounded by small size). Small studies have been shown to overestimate treatment effects, probably due to methodological weaknesses (Moore 2010, Nüesch 2010). Studies were considered at low risk of bias if they had 200 or more participants, at unclear risk if they had between 50 and 200 participants, and at high risk if they had fewer than 50 participants.

We also assessed studies using the Oxford Quality Score (Jadad 1996).

Measures of treatment effect

Where possible we planned to use dichotomous data (patients experiencing an adverse event) to calculate risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a fixed‐effect model unless significant statistical heterogeneity was found. Where that was possible, and where there was statistical significance, we would calculate numbers needed to harm (NNH) as the reciprocal of the absolute risk increase (McQuay 1997).

Dealing with missing data

The completeness of reporting of adverse event data in clinical trials is known to be a significant problem (Derry 2008; Edwards 1999; Ioannidis 2001; Loke 2001). Issues include how adverse events are recorded (diaries versus spontaneous reporting, for example), and whether all adverse events are reported in publications, where often only those with 3%, 5%, or even 10% incidence are recorded. For none of these issues is there a suitable mechanism for dealing with it, nor is it known which if any of the methods used for recording adverse events provides the 'best', or 'truest' result. For these reasons data as reported in the studies was taken as reported, with no method used to deal with the potential for missing data.

One other possible problem is nomenclature. For example, consciousness has a spectrum from fully alert on the one side to unconscious on the other. Words used to describe states of consciousness include sleepiness, drowsiness, or somnolence (Tassi 2001). We combined slightly different reporting nomenclature from different trials, so somnolence, for instance, included both drowsiness and sleepiness.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Assessment of statistical heterogeneity would use the I2 statistic if appropriate, however we did not carry out any meta‐analysis.

Data synthesis

We planned to undertake head to head comparisons of these drugs. If data were available, we planned to use Review Manager 5.2 (RevMan 2012) for statistical meta‐analysis. Where results were statistically significant, we would have calculated the numbers needed to treat for harm (NNTH) for adverse events (Cook 1995).

Due to the absence of direct head to head comparisons we have chosen to calculate the proportion of participants experiencing each of the adverse events of interest with each opioid to allow a simple comparison of rates, and for all opioid drugs combined.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The evidence base was expected to be small, so subgroup analyses were conducted only for the individual drugs. Any subgroup analysis required at least two studies with at least 200 participants.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not plan any sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The only studies considered were those included in Cochrane reviews of morphine (Wiffen 2013), fentanyl (Hadley 2012) oxycodone (Schmidt‐Hansen 2010 together with the authors of an ongoing update, supplemented by additional searches), and a completed but unpublished review of codeine (Schremmer 2013 ‐ full review in press).

Included studies

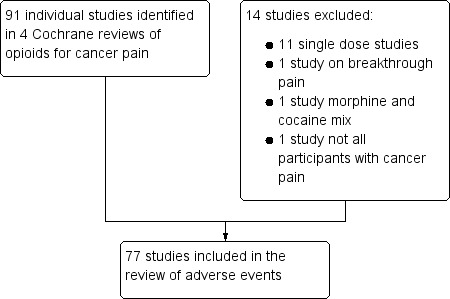

We included 77 studies (Figure 1).

1.

Flow diagram of studies in the review

Morphine in various oral formulations was the sole opioid in 43 studies with 2160 participants (Arkinstall 1989; Babul 1998; Boureau 1992; Broomhead 1997; Cundiff 1989; Currow 2007; Dale 2009; De Conno 1995; Dellemijn 1994; Deschamps 1992; Ferrell 1989; Finn 1993; Flöter 1997; Gillette 1997; Gourlay 1997; Guo‐Zhu 1997; Hagen 2005; Hanks 1987; Hanks 1995; Harris 2003; Homsi 2010; Hoskin 1989; Kerr 2000; Klepstad 2003; Knudsen 1985; Kossman 1983; Melzack 1979; Mignault 1995; Mizuguchi 1990; O'Brien 1997; Panich 1993; Portenoy 1989; Ridgway 2010; Rodriguez 1994; Smith 1991; Thirlwell 1989; Todd 2002; Vainio 1988; Ventafridda 1989; Vielvoye‐Kerkmeer 2002; Walsh 1985; Walsh 1992; Wilkinson 1992).

Morphine in various oral formulations was compared with another opioid in 18 studies with 1382 participants. The other opioids were transdermal fentanyl (Ahmedzai 1997; Mercadante 2008; Oztürk 2008; van Seventer 2003; Wong 1997), oral oxycodone (Bruera 1998; Heiskanen 1997; Kalso 1990; Lauretti 2003; Mercadante 2010; Mucci LoRusso 1998), methadone (Bruera 2004; Ventafridda 1986), hydromorphone (Hanna 2008; Moriarty 1999), tramadol (Leppart 2001; Wilder‐Smith1994), and dextropropoxyphene (Mercadante 1998).

Fentanyl in various transdermal formulations was the sole opioid in four studies with 801 participants (Kongsgaard 1998; Kress 2008; Mystakidou 2005; Pistevou‐Gompaki 2004).

Oxycodone in various oral forms was the sole opioid in six studies with 574 participants (Ahmedzai 2012; Gabrail 2004; Kaplan 1998; Parris 1998; Salzman 1999; Stambaugh 2001).

Oxycodone in various oral formulations was compared with another opioid in two studies with 371 participants. The other opioids were hydromorphone (Hagen 1997) and tapentadol (Imanaka 2013).

Codeine in various oral forms was the sole opioid in two studies with 110 participants (Carlson 1990; Dhaliwal 1995).

Codeine was compared with another opioid in two studies with 221 participants. The other opioids were tramadol (Rico 2000) and tramadol or hydrocodone (Rodriguez 2007).

Participants in the studies were usually equally men and women, with a mean age between 50 and 70 years, and an age range typically between 30 and 87 years. In some of the larger trials with a slightly higher mean age, over half the participants were aged over 65 years (Imanaka 2013).

While all studies were of patients with cancer‐related pain, not all specified the type of cancer. Where reported most studies were of mixed cancer types.

Excluded studies

We excluded 14 studies after reading the full reports. Reasons for exclusion of individual studies are in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The most common reason for exclusion was that studies only investigated a single dose of opioid.

Risk of bias in included studies

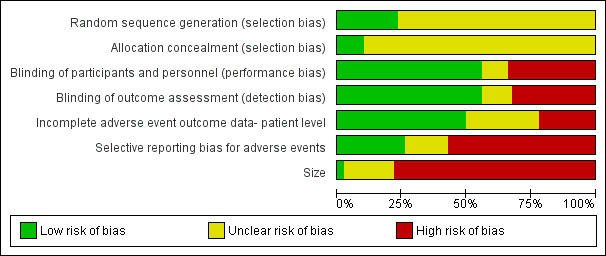

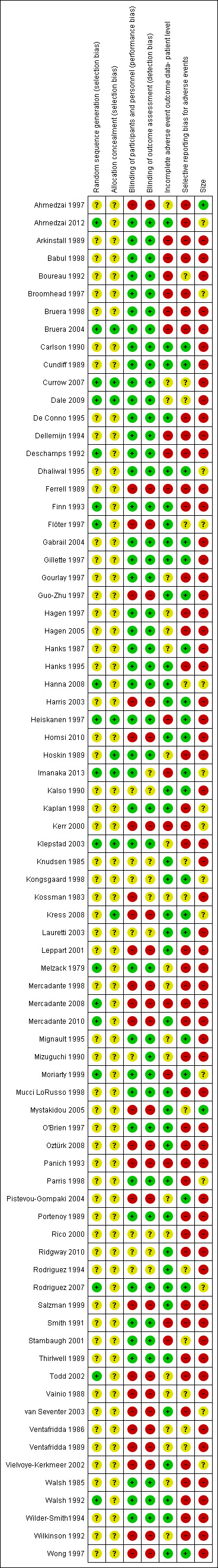

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the 'Risk of bias' assessments by category for each included study. The Oxford Quality Scores were 1/5 for seven studies, 2/5 for 18 studies, 3/5 for 13 studies, 4/5 for 26 studies, and 5/5 for 13 studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All studies were randomised. Random sequence generation and allocation concealment were unclear in most studies (Figure 2).

Blinding

A number of the studies were open, and for these risk of bias was high (Figure 2).

Incomplete outcome data

Over half of the studies failed to include all participants randomised and given at least one dose of opioid when reporting adverse events (Figure 2). These were judged to be at high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

A number of studies reported only the most common adverse events, or those occurring at more than a given incidence (5%, for example); these were judged to be at high risk of bias (Figure 2).

Other potential sources of bias

Small size was a major potential source of bias. Studies were typically small: 20 of the 77 studies randomised 100 or more participants, and these involved 60% of the total participant numbers; 45 of the 77 studies involved fewer than 50 participants, with only 25% of total participants. Individual treatment groups included fewer than 50 participants in 60 studies, between 50 and 199 participants in 15 studies, and 200 or more in only two studies (Figure 3).

Effects of interventions

It was not possible to perform any pooled comparative analysis because of the varied nature of the comparisons made in the different studies, We therefore provide a narrative report on the primary outcomes, and a pooled analysis of adverse event incidence rates for secondary outcomes, by individual opioid, and by all four opioids combined.

Primary outcomes

There were few direct mentions of events approximating to our primary outcome of patient consciousness, patient appetite, or thirst. Only one study (Imanaka 2013) reported classification methods used for adverse events.

For morphine, one study reported stupor in 9/98 participants, without defining what was meant by stupor, or what the cause might be. We judged that this was possibly a translation problem (the study originated in Thailand; Panich 1993), and we included this under somnolence in our analysis of secondary outcomes.

For oxycodone, Kalso reported sedation in most participants, but also reported somnolence in 4/19 (Kalso 1990); it is difficult to interpret both of these events. On the other hand Gabrail (Gabrail 2004) mentioned sedation in 13/41 participants on oxycodone, but did not mention somnolence as a separate adverse event; we interpreted this as a different definition of somnolence or drowsiness.

Appetite was reported specifically in only one study (Imanaka 2013), who reported that 24/172 participants had decreased appetite without commenting further. Studies reporting the outcome of anorexia did not provide further details (Lauretti 2003).

Secondary outcomes

Results of surrogate adverse events for individual opioids and for all four opioids combined is in Summary of results A. For a number of adverse events a large number of participants reported on their presence or absence, over 2,000 for nausea, vomiting, constipation, and somnolence, and over 1,000 for dizziness. Other adverse events were reported less frequently; the reasons are unknown, but include low incidence adverse events often not being reported by studies.

There was a general consistency in event rates between different opioids, with constipation, somnolence, and nausea all reported by over 20% of participants.

Summary of results A: pooled adverse event incidence rates for individual opioids and all four combined

| Morphine ‐ oral | Fentanyl ‐ TD | Oxycodone ‐ oral | Codeine ‐ oral | All opioids | ||||||

| Adverse event | Events/total | Percent | Events/total | Percent | Events/total | Percent | Events/total | Percent | Events/total | Percent |

| Nausea | 267/1205 | 22 | 93/664 | 14 | 201/885 | 23 | 61/171 | 36 | 622/2925 | 21 |

| Vomiting | 115/869 | 13 | 43/587 | 7 | 119/866 | 14 | 40/171 | 23 | 317/2493 | 13 |

| Constipation | 355/1189 | 30 | 105/632 | 17 | 196/885 | 22 | 52/171 | 30 | 708/2877 | 25 |

| Diarrhoea | 18/416 | 4 | No data | 29/383 | 8 | 0/99 | 0 | 47/898 | 5 | |

| Dyspepsia | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | |||||

| Decreased appetite/Anorexia | 38/354 | 11 | 9/20 | 45 | 38/221 | 17 | 2/99 | 2 | 87/694 | 13 |

| Dry mouth | 104/222 | 47 | 3/117 | 3 | 37/469 | 8 | 18/134 | 13 | 162/942 | 17 |

| Dysphagia | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | |||||

| Dehydration | No data | 2/117 | 2 | No data | No data | 2/117 | 2 | |||

| Somnolence | 290/1205 | 24 | 26/204 | 13 | 172/715 | 24 | 29/134 | 22 | 517/2258 | 23 |

| Delirium | 1/54 | 2 | No data | 6/172 | 3 | No data | 7/226 | 3 | ||

| Dizziness | 89/592 | 15 | 4/117 | 3 | 61/488 | 13 | 21/134 | 16 | 175/1331 | 13 |

| Insomnia | 1/20 | 5 | 5/137 | 4 | 21/435 | 5 | 0/99 | 0 | 27/691 | 4 |

| Asthenia | No data | 2/117 | 2 | 14/208 | 7 | 5/94 | 5 | 21/419 | 5 | |

| Hallucinations | 6/305 | 2 | 2/117 | 2 | 0/60 | 0 | 4/59 | 7 | 12/541 | 2 |

| Mood change | 20/451 | 4 | No data | No data | No data | 20/451 | 4 | |||

The most appropriate surrogate measure of consciousness was probably somnolence, into which we pooled several definitions including drowsiness, sleepiness, and stupor. It was reported by 517/2258 participants (23%); severity was not usually mentioned. Delirium was reported in 7/226 participants.

The most appropriate surrogate measure of patient appetite was probably anorexia. Together with the report of decreased appetite it was reported by 87/898 participants (13%); neither severity nor consequences were mentioned.

There was no obvious appropriate surrogate measure of thirst, but dry mouth occurred in 162/942 participants (17%), with no indication of severity.

Many participants received concomitant medication. Where clearly identified, these are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table. In many cases they included medications that could produce the adverse events of interest. It would have been helpful if these medications were clearly specified in every study.

Discussion

The title of this rapid review was registered on 7 March 2014, the protocol submitted on 11 March and published on 31 March. The full review was submitted on 2 May 2014, revisions after peer review completed by 15 May, and the expected date of publication is early June 2014. The process will have been completed in about 13 weeks. While the review has been rapid it has not compromised on methodological quality. Rapidity was achieved by a combination of using studies identified by previous and ongoing Cochrane reviews, an experienced review team, thoughtful peer reviewers, and by a prepared and proactive editorial base.

Summary of main results

Direct measures of patient consciousness, patient appetite, or thirst were not apparent. The results showed that several adverse events that are likely to impact on the quality of life were common with opioids used to treat cancer pain, with incidence rates of 25% for constipation, 23% for somnolence, 21% for nausea, 17% for dry mouth, and 13% for vomiting, anorexia, and dizziness. Asthenia, diarrhoea, insomnia, mood change, hallucinations and dehydration occurred at incidence rates of 5% and below. For a variety of reasons discussed below, none of these can be attributed unequivocally to the use of opioid.

None of the included studies was undertaken in a ‘dying patient’ population.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The assessment of adverse events is fraught with problems. Firstly, even young, fit people taking no medicines and with no known medical problems report high rates of adverse events over periods as short as three days, with fatigue reported by 40% (Meyer 1996; Reidenberg 1968). High levels of adverse event reports can be found in patients given placebo in clinical trials of statins and in adults not in a clinical trial over a short time period (Rief 2006). These can include what might be regarded as very important events, like chest pain, as well as events like diarrhoea or nausea. In addition, adverse event incidence depends on the assessment method, whether reporting is spontaneous or elicited in any way, with elicited events give much higher overall adverse event rates than those reported spontaneously (Edwards 1999; Olsen 1999; Rief 2009). There is some evidence that expectations from investigators and participants can influence adverse event profiles (Rief 2009). Moreover, for some adverse events patients accommodate quickly when doses of opioids are stabilised, and event rates may be higher when dose titration is occurring. This may be the case in some of these relatively short duration studies, but few of them were carried out in opioid‐naive patients as many were switching participants from one opioid formulation to another.

Added to this is the well‐known problem that trial reports often failed to provide details on how adverse drug reactions were defined or recorded (Loke 2001; Nuovo 2007). In this review, for instance, some adverse events were only reported if they were considered to be drug related, or new, or unexpected. And where people are being treated for cancer, the use of concomitant medications or comorbid conditions or both may confound results.

This background limits the confidence we can have in adverse event reports, except in the broadest sense.

In this review there were major problems with completeness of the evidence. One reason was the tendency for studies to report only the most commonly occurring adverse events, above 5%, for instance. Another tendency was to report adverse events on subsections of the whole population randomised and receiving at least one dose of opioid, participants completing all phases of a cross‐over study, for instance. Together these mean that, particularly for less common adverse events, we have reports on only a proportion of the total population exposed.

Severity of adverse events was not usually reported. Severity is intertwined with definitions and meaning of outcomes, and particularly the interpretation of any adverse event incidence rate. For example, consciousness has a spectrum between fully alert and unconscious, with drowsiness, sleepiness, somnolence, and stupor being points of severity along the spectrum, some of which may have particular clinical and human relevance in different circumstances. There is little literature to help, as most studies of consciousness are concerned with the difference between consciousness and unconsciousness, and with no good definitions of different states of consciousness (Tassi 2001). Much the same might be said about decreased appetite or anorexia.

The applicability of the evidence on adverse events to the population of patients with cancer pain studied is high. These tended, however, to be relatively young, with mean ages in individual studies mostly between 50 and 70 years. The situation is probably quite different in the older, more frail population likely to be representative of people being treated at the end of life, who are often being given drugs other than opioids, and in whom the incidence of adverse drug reactions is known to be high (Avorn 2008). Using lessons learned from cancer for end‐of‐life care is acknowledged to be difficult (Murray 2008). We think it unlikely that the type of cancer will influence the response to analgesia in these studies of moderate to severe pain at baseline.

Quality of the evidence

Most of the studies were small, and others had problems of incomplete and selective reporting of adverse event outcome data, as well as an absence of clear definitions of what some adverse events actually meant.

Potential biases in the review process

We were unaware of any potential biases in the review process other than taking only studies included in four cancer pain Cochrane reviews. This is unlikely to be a major concern, as there are relatively few RCTs for other opioids, but the four included reviews excluded studies not using pain as an outcome measure. It is not impossible that meaningful studies of opioids in cancer reported only adverse event data, and we are unaware of any large body of evidence that may have been overlooked. To the best of our knowledge there is no literature on adverse events of opioids more relevant for end‐of‐life care.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

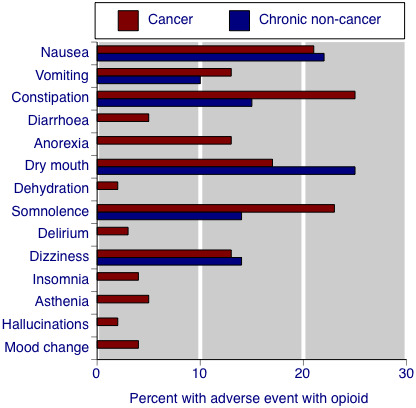

Only one other systematic review has reported on adverse events of opioids, in that case in chronic non‐cancer pain (Moore 2005). Figure 4 compares adverse event incidence rates found in cancer and chronic non‐cancer pain. They are very similar, though it should be noted that only common adverse events were assessed in chronic non‐cancer pain; non appearance of an adverse event in the figure does not mean that it was not present.

4.

Comparison of adverse event rates in randomised studies of opioids in cancer pain and chronic non‐cancer pain

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found no evidence that opioids were associated with patient consciousness, appetite or thirst when used to treat cancer pain. However, somnolence, dry mouth, and anorexia were common adverse events in people with cancer pain treated with morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, or codeine. Rates were similar to those in chronic non‐cancer pain. Both these populations entered into randomised trials were likely to be considerably younger and much less frail than people treated with opioids at the end of life. It is likely that opioids used for end‐of‐life care will to some degree affect patient consciousness, appetite, and thirst, but it is not possible to quantify the effect or to identify circumstances where problems may be greater or lesser.

Implications for research.

In order to address the issues raised by the Neuberger Review, research into the effect of opioids on levels of consciousness, and effects on appetite and thirst in dying patients should be commissioned. This is no easy task, however, and there are many, possibly major, issues that would need to be overcome in defining what that research may comprise.

There are two immediate implications for research, and we limit comments to these two.

Definitions

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect is the issue of how adverse events are recorded, and the issues of seriousness, severity, and definition. There are a number of systems for recording diagnoses and adverse events, including the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), and MedDRA (the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Terminology), a controlled vocabulary widely used as a medical coding scheme for adverse events. These are often used, but because of their broad, generic, nature, often fail to pick up important nuances in specific circumstances.

Adverse events often display a spectrum of seriousness. For example, the induction agent propofol exhibits cardiac events that include bradycardia (1 in 9), asystole (1 in 660), and bradycardia‐related death (1 in 100,000) (Tramèr 1997), and a spectrum of gastrointestinal harm exists with NSAIDs, encompassing dyspepsia, endoscopically detected ulcers and erosions, hospital admission for bleeding ulcer, and death from bleeding ulcer (Tramèr 2000).

One of the issues with spectrums of harm is that the most serious events are rare and difficult to capture, and often more common, surrogate, measures are used in their place. All of which is fine as long as the spectrum can be well established, and there are well‐established definitions that can be followed. Even then, establishing the value of a surrogate measure can be difficult despite very considerable evidence (Moore 2009; Moore 2013).

It is likely that there are spectrums of outcome for consciousness (from fully alert, to drowsy, sleepy, somnolent, sedated, and then unconscious). But this all depends on how words are used. For example, in discussing results from one RCT done more than 20 years ago with an author, it was clear that the trial report of sedation actually meant fatigue, or tiredness. For eating and drinking it is likely that similar principles apply.

Therefore one clear implication for research is for:

a set of clear definitions of the various sections of each spectrum that is of clinical interest;

the development of measurement tools or aids;

testing the tools;

investigating whether a spectrum of response can be determined.

Data recording and reporting

Some studies produced good quality adverse event data in tables, but most studies did not do this. There are groups working on adverse event reporting standards, and the CONSORT group has provided useful guidance on adverse event reporting (Ioannidis 2004). A Cochrane Adverse Effects Methods Group also exists.

The problem, though, is that while such groups do excellent work on the generic problems of adverse event recording and reporting, this may still fail to be useful to a specific set of harms in specific circumstances. A key need, therefore, is to develop a set of recommendations on adverse events (and perhaps beneficial events) that are specific to end‐of‐life care, in order that they may be tested and used in clinical practice and clinical trials.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 May 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 11 October 2017 | Review declared as stable | No new studies likely to change the conclusions are expected. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2014 Review first published: Issue 5, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 July 2017 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

| 13 January 2015 | Amended | Minor corrections. |

| 2 October 2014 | Amended | Minor typo corrected. |

| 16 June 2014 | Amended | Minor change to wording to remove possible ambiguity in 'Implications for practice'. |

Notes

A restricted search in July 2017 did not identify any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions. Therefore, this review has now been stabilised following discussion with the authors and editors. If appropriate, we will update the review if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr Bee Wee for useful discussions that led to the initiation of this review, Mia Schmidt‐Hansen and Carmen Schremmer for allowing us access to their ongoing Cochrane reviews, and for several thoughtful peer reviewers of protocol and final review who provided useful additional guidance and insight.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ahmedzai 1997.

| Methods | Design: multicentre, randomised, open label, two‐period cross‐over study. Initial opioid dose calculated using manufacturers recommendations, with dose titration at start of each period to achieve pain control. Assessed at baseline and 8, 16, 23, 31 days, and by daily patient diary Duration: 2 x 15 days, no washout between periods + titration Setting: Palliative care centres, UK |

|

| Participants | Adult cancer patients requiring strong opioid analgesia and receiving stable dose of morphine for at least 48 hours Life expectancy > 1 month N = 202 M 112, F 90 Mean age 62 years (range 18 to 89) |

|

| Interventions |

MIR was used freely to titrate pain at the start of study and at cross‐over Where possible other medication remained unchanged, but other analgesics allowed: e.g. NSAIDs, permitted radiotherapy, nerve blocks |

|

| Outcomes | Sleep, rescue medication, drowsiness: VAS, daily diary Pain and mood: Memorial Pain Assessment Card, twice daily QoL (self‐rated): EORTC (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer) QLQ‐C30 Performance status (clinician rated): WHO scale Treatment preference Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 0, W = 1. Total = 2/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open study |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Unclear risk | Presented as numbers of AEs but not clear whether this is events or participants. Denominator unclear. |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Only commonest events reported |

| Size | Low risk | > 200 participants per treatment arm |

Ahmedzai 2012.

| Methods | Design: randomised double blind, active controlled, double dummy, parallel group study. Pre‐study opioid and laxative stopped prior to randomisation Duration: 4 weeks Setting: Probably community‐ not clearly stated |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain‐ moderate or severe requiring round the clock opioid therapy equivalent to Oxycodone 20‐80mg/day. Participants who had chemotherapy in previous 2 weeks excluded or radiotherapy that could influence bowel function or pain N = 184 M 94, F 90 Mean age 63 years (range 36 ‐ 84) |

|

| Interventions | 1. Oxycodone prolonged release 2. Oxycodone prolonged release with naloxone |

|

| Outcomes | Pain control using BPI‐SF Bowel function Use of rescue medication Use of laxatives QoL Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'pseudo random number generator in a computer programme' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 'treatments were masked in a double dummy fashion' |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 'treatments were masked in a double dummy fashion' |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Low risk | > 90% of participants included |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Incomplete breakdown of AEs |

| Size | Unclear risk | 185 participants |

Arkinstall 1989.

| Methods | Design: randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over study. Prestudy stabilisation period to achieve adequate control of pain, no change in dose for ≥ 3 days, and mean daily rescue medication ≤ 50% of titrated daily dose Duration: 2 x 10 days, no washout, + dose stabilisation phase Setting: Hospital/acute /surgery/community |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain N = 29 Mean age 63 years Mean weight 61.1 kg |

|

| Interventions |

Rescue medication: MIR |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS PPI: McGill‐Melzack Pain Questionnaire (6‐point categorical scale) Use of rescue medication Treatment preference Plasma morphine concentrations in last 3 days of both phases Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "by means of random allocation". Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "matching placebos were used to maintain blinding" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "matching placebos were used to maintain blinding" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | AEs reported on fewer than 90% participants |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Only frequent AEs reported‐mean data only |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Babul 1998.

| Methods | Design: Randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over study. Dose stabilisation using morphine; non‐morphine participants transferred to morphine Duration: 2 x 7 days + dose stabilisation phase Setting: not specified |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain N = 27 (22 completed and evaluated) M 13, F 9 Mean age 55 years |

|

| Interventions |

Dose ratio oral:rectal = 1:1 Non‐opioid analgesics continued Rescue medication: MIR |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS x 4 daily PPI (6‐point categorised scale: no pain 0, mild pain 1, discomforting pain 2, distressing pain 3, horrible pain 4, excruciating pain 5) Nausea, sedation: 100 mm VAS ‐ spontaneous + investigator‐reported |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomised". Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Double blind conditions maintained by use of matching placebos" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Double blind conditions maintained by use of matching placebos" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | AEs reported on fewer than 90% participants |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | 'AEs consistent with use of opioid analgesics in patients with advanced cancer' |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Boureau 1992.

| Methods | Design: Multicentre, randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over study Duration: 2 x 7 days, with no washout Setting: not stated |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain. Participants on stable dose morphine for previous 48 h with adequate pain relief. Participants all taking < 400 mg morphine/24 h N = 52 (44 analysed) M 34, F 18 Age 62 years (SD 11) |

|

| Interventions | Previous daily dose of morphine given in 2 doses (12‐hourly)

Morphine dose: 108 mg/day (SD 57; range 40 to 260) |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS x 3 daily Verbal rating scale (5‐point) Rescue medication Participant preferences QoL indices (activity mood sleep) by participant and investigator |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "four patient block randomisation method". Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double dummy design with placebo |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double dummy design with placebo |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | AEs reported on fewer than 90% participants |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | Unclear risk | Unsure if full list of AEs reported |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Broomhead 1997.

| Methods | Design: multicentre, randomised, double blind (double dummy), parallel group study. Participants titrated with MIR during 3 to 14 day run‐in period to achieve adequate control of pain, no change in dose for 3 consecutive days, and ≤ 2 doses of rescue medication/day Duration of treatment: 7 days ± 1 day + titration phase Setting: outpatients |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain of moderate to severe intensity N = Phase 1: 19, Phase 2 169 received treatment and were randomised (152 completers) Mean age 61 years |

|

| Interventions | Phase 1:

Phase 2 (main study): As phase1 but no placebo Other non‐opioid medication was allowed Rescue medication: MIR for all groups |

|

| Outcomes | Elapsed time to re‐medication and total amount of rescue medication Pain intensity (VAS) daily Verbal PI (four point) Verbal PR (four point) Sleep quality Global assessment over 7 days Adverse events (5‐point) |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly assigned". Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double dummy design with placebo |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double dummy design with placebo |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | AEs reported on fewer than 90% participants |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Not all AEs reported |

| Size | Unclear risk | 50 to 199 participants per treatment arm |

Bruera 1998.

| Methods | Design: Randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over study. Stable analgesic requirements for ≥ 3 days with rescue medication ≤ 20% daily dose Duration: 2 x 7 days, with no washout Setting: Palliative care programme |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain N = 32 (23 completed and assessed) M 9, F 23 |

|

| Interventions |

Dose adjustment allowed if greater than 3 rescue doses in previous 24 hours Rescue medication: IR Oxycodone or MIR; no other opioids or analgesics allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS x 4 daily and 5‐point categorical scale Participant preferences Nausea and sedation scale Adverse event checklist Rescue analgesia |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomised". Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "blinding was maintained by double dummy technique using matching placebos" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "blinding was maintained by double dummy technique using matching placebos" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | AEs reported on fewer than 90% participants |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Reported as no difference between groups |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Bruera 2004.

| Methods | Design: Randomised, double blind, parallel group study. Dose titrated over first 8 days Duration: 4 weeks Setting: Palliative care groups |

|

| Participants | Advanced cancer and pain requiring the initiation of strong opioids N = 103 M 37, F 66 Median age 60 years (range 26 to 87) |

|

| Interventions |

Dose adjustments allowed Non‐opioid analgesics discontinued Rescue medication: 5 mg methadone or MIR every 4 h as needed |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS Sedation, confusion, nausea, constipation: VAS Edmonton staging system for cancer pain: daily assessments for 8 d then weekly assessment Global impression of change |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "the random allocation sequence was generated centrally by computer generated numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "allocation code was kept in a sealed envelope" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "capsules containing the drug were identical" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "capsules containing the drug were identical" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | AEs reported on fewer than 90% participants |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Only AEs leading to withdrawal and mean data for some AEs was reported |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants in each treatment arm |

Carlson 1990.

| Methods | Design: randomised, double blind, parallel group, first‐dose 6‐hour observation period in which patients were randomised to ketorolac, paracetamol plus codeine, or placebo. Thereafter participants receiving placebo were reassigned to one of the two active treatments and observed for 7 days with drugs taken x 4 daily Setting: not stated |

|

| Participants | Moderate to severe cancer pain; histologically confirmed diagnosis of cancer (most common types: genitourinary, lung, breast, gastrointestinal) N = 75 M 43, F 32 Mean age 62 years |

|

| Interventions | First‐dose 6‐hour observation period:

|

|

| Outcomes | PI: four‐point scale (0‐3)

PR:five‐point scale (0‐4) Time to remedication Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not clearly stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "identical‐appearing capsules" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "identical‐appearing capsules" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Low risk | >90% participants included |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | Low risk | All AEs reported |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Cundiff 1989.

| Methods | Design: randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over. Morphine titrated upwards until not more than 20% total daily morphine given as rescue over a 2‐day period Duration: 4 ‐ 7 days (time to reach steady state). Cross‐over to start at ⅓ pre‐study equivalent then titrate up Setting: in‐ and outpatients |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain N = 23 (14 evaluable) M 9, F 5 Mean age 45 years (range 31 to 72) |

|

| Interventions |

Rescue medication: 15 mg MIR tablets |

|

| Outcomes | Dose and frequency of rescue medication Nurse assessed PI Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "random assignment". Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "double dummy technique.... placebo physically indistinguishable from the alternative therapy" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "double dummy technique.... placebo physically indistinguishable from the alternative therapy" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Low risk | All participants reported |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | Low risk | All AEs reported |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Currow 2007.

| Methods | Design: Randomised, double blind, two‐period cross‐over study Duration: 2 x 7 days + 1 day cross‐over on day 8 Setting: community and hospital |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain N = 42 M 28, F 14 Mean age 64 years (36 ‐ 82) |

|

| Interventions |

Co‐analgesics allowed at stable doses |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS, every 4 h while awake PR: categorical scale, daily Adverse events Sleep, nausea and vomiting, constipation, confusion, somnolence: categorical scale |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomisation was allocated from a central computer generated random number sequence" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "the process was blinded at all times to participants and treating clinicians" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "identical placebo" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "identical placebo" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Unclear risk | Data not reported |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | Unclear risk | Only mean data with no denominator |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Dale 2009.

| Methods | Design: Randomised, double blind, two‐period cross‐over study. After titration of dose, participants randomised to receive either a single dose of MIR at bedtime followed by another dose 4 h later, or a double dose of MIR with a placebo dose 4 h later Duration: 2 x 1 night on each treatment Setting: hospital inpatients |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain N = 22 (19 completed) M 11, F 8 Mean age 57 years (45 ‐ 74) |

|

| Interventions |

|

|

| Outcomes | PI: 11‐point NRS Participant preference BPI, Edmonton symptom assessment scale |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "concealed procedure performed by hospital pharmacist using restricted randomisation table" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "concealed procedure performed by hospital pharmacist using restricted randomisation table" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "placebo tablets identical in appearance and taste" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "placebo tablets identical in appearance and taste" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Unclear risk | Adverse events reported with patient numbers but not clear if everything was reported |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | Unclear risk | Only mean data with no denominator |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

De Conno 1995.

| Methods | Design: randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over study. Assessments at 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, 90, 120, 180 and 240 mins daily Duration: 2 x 2 days Setting: outpatients |

|

| Participants | Advanced or metastatic cancer with PI > 30/100 mm at baseline, opioid‐naive

N = 34 M 23, F 11 Mean age 59 (SD 8.8; range 38 to 70) |

|

| Interventions |

Single dose administered on each of two days then crossover to other treatment. Use of NSAIDs allowed for first day |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS Nausea and sedation: VAS Number of vomiting episodes Time to pain relief |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 0. Total = 3/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly allocated ... according to a predetermined allocation sequence". Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "double blind double dummy technique" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "double blind double dummy technique" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Low risk | >90% participants included |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Only nausea, vomiting & sedation reported |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Dellemijn 1994.

| Methods | Design: randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over study Duration 2 x 1 week, 6 h washout period Setting: not stated |

|

| Participants | Malignant nerve pain due to cancer (severe) N = 20 (16 evaluable) M 10, F 10 Age 42 ‐ 81 years |

|

| Interventions |

Rescue medication: paracetamol and domperidone |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 101‐point numerical rating scale after 7 days PR: 6‐point categorical after 7 days Participant preference Rescue medication Adverse events: 4‐point scale |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | 'randomised'. Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 'double blind, dummy technique' |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 'double blind, dummy technique' |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | AEs reported on fewer than 90% participants |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | mean data only |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Deschamps 1992.

| Methods | Design: randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over study with titration phase Duration 2 x 7 days, no washout Setting: outpatients |

|

| Participants | Metastatic cancer with pain requiring opioids N = 20 Mean age 57 years (range 40 to 72) |

|

| Interventions |

No dose adjustment allowed after titration MIR (solution) for breakthrough; no other opioids/analgesics allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 100 mm VAS Adverse events: verbal (6‐point) severity scale Participant preference |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomised by Pharmaceutical company...using randomisation table" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "titration and trial phases conducted under double blind conditions with double dummy technique" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "titration and trial phases conducted under double blind conditions with double dummy technique" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | AEs reported on fewer than 90% participants |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Common AEs only reported as mean scores |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Dhaliwal 1995.

| Methods | Design: Randomised, double blind, two‐period cross‐over study Duration: 2 x 7 days |

|

| Participants | Chronic cancer pain N = 35 participants (30 completers: 13 women, 17 men) Mean age 64 years |

|

| Interventions |

Rescue medication: paracetamol 300 mg plus codeine 30 mg once or twice every 4 hours |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 100 mm VAS and five‐point NRS (0‐4) Doses of rescue medication per day Pain disability index Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not clearly stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "matching placebos" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "matching placebos" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Low risk | > 90% of participants included |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | Low risk | All AEs included |

| Size | Unclear risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Ferrell 1989.

| Methods | Design: Randomised, open label, parallel group study. Participants remained on current short acting analgesics (oxycodone, hydromorphone, codeine or short‐acting morphine) or switched to MS Contin. Historical control of patients receiving MS Contin ≥ 2 weeks, who remained on the treatment Duration: 6 weeks Setting: Oncology units in 2 US hospitals |

|

| Participants | Chronic cancer pain, receiving short‐acting oxycodone, hydromorphone, codeine, morphine N = 83 M 36, F 47 Mean age 60 years (range 21 ‐ 87) |

|

| Interventions |

Doses not stated |

|

| Outcomes | Pain Experience Measure Tool PPI: McGill City of Hope QoL |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 0, W = 0. Total = 1/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly assigned". Method used to generate sequence not clearly stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open study |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | High risk | QoL study, AEs not reported |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | QoL study, AEs not reported |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

Finn 1993.

| Methods | Design: Randomised, double blind (double dummy), two‐period cross‐over study Duration of study: 6 days (day 1: usual MIR; days 2 and 3 either Mm/r or MIR (with matched placebo); days 4 and 5 cross‐over) Setting: outpatients |

|

| Participants | Cancer pain requiring > 60 mg MIR/daily N = 37 (34 completed) Mean age 59 years |

|

| Interventions |

Dose adjustment allowed Non‐opioid medications continued Rescue medication: paracetamol, MIR or sub‐cut/IM morphine |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS x 3 daily, and 4‐point categorical (Karnofsky) Adverse events Use of rescue medication Participant preference |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomisation by using randomisation schedule provided to the responsible pharmacist" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "blinded drug supplies packaged daily by the responsible pharmacist" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "blinded drug supplies packaged daily by the responsible pharmacist" |

| Incomplete adverse event outcome data‐ patient level | Low risk | > 90% of participants included |

| Selective reporting bias for adverse events | High risk | Only selected AEs reported |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment group |

Flöter 1997.

| Methods | Design: randomised, open label, parallel group study. Initial 7 ‐ 14 day titration with Kapanol or Mm/r Duration: 14 days + titration phase Setting: in‐ and outpatient |

|

| Participants | Mixed pain: 27/91 Kapenol and 26/74 MST had cancer pain N = 165 M 98, F 67 Mean age 55 years Weight 69 kg |

|

| Interventions |

Paracetamol, NSAIDs, antidepressants allowed; advised not to alter. Other opioids not permitted Rescue medication: MIR 10 mg |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS (physician assessment of pain control)

Quality of sleep

Rescue medication

Well being etc (patient diary) Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 0, W = 1. Total = 3/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomisation performed using a random number generator" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open |