Abstract

Background

The underlying neurobiological mechanism for abnormal functional connectivity in schizophrenia (SCZ) remains unknown. This project investigated whether glutamate and GABA, 2 metabolites that contribute to excitatory and inhibitory functions, may influence functional connectivity in SCZ.

Methods

Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy were acquired from 58 SCZ patients and 61 healthy controls (HC). Seed-based connectivity maps were extracted between the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) spectroscopic voxel and all other brain voxels. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) spectra were processed to quantify glutamate and GABA levels. Regression analysis was performed to describe relationships between functional connectivity and glutamate and GABA levels.

Results

Reduced ACC functional connectivity in SCZ was found in regions associated with several neural networks including the default mode network (DMN) compared to HC. In the HC, positive correlations were found between glutamate and both ACC—right inferior frontal gyrus functional connectivity and ACC—bilateral superior temporal gyrus functional connectivity. A negative correlation between GABA and ACC—left posterior cingulate functional connectivity was also observed in HC. These same relationships were not statistically significant in SCZ.

Conclusions

The present investigation is one of the first studies to examine links between functional connectivity and glutamate and GABA levels in SCZ. Results indicate that glutamate and GABA play an important role in the functional connectivity modulation in the healthy brain. The absence of glutamate and GABA correlations in areas where SCZ showed significantly reduced functional connectivity may suggest that this chemical-functional relationship is disrupted in SCZ.

Keywords: resting-state functional connectivity, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, schizophrenia

Introduction

Functional connectivity is a powerful method for evaluating temporal correlations of low-frequency functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) fluctuations across brain regions in the absence of a task or stimulus.1 Functional connectivity is based on the observation that distant brain regions often display strongly coherent patterns of neural activity, likely via reciprocal excitatory neurotransmission through long-distance white matter pathways.2,3 Functional connectivity alterations are commonly observed in schizophrenia (SCZ),4 but the underlying neurobiological mechanism remains unknown

Glutamatergic and GABAergic systems play an important role in regulating cortical circuits that are functionally connected.5 Excitatory glutamatergic projection neurons provide the basis for BOLD fMRI signal generation.6,7 GABAergic interneurons likely modulate the BOLD signal indirectly through inhibitory feedback signaling within microcircuits.8 Correlations between glutamate and GABA and fMRI BOLD signal changes due to a task or stimulus have been reported.9 Associations between glutamate and GABA levels and intrinsic resting-state functional connectivity have also been reported in healthy participants10,11; however, this has not been investigated in patients with SCZ.

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) has been shown to play an important role in pathophysiology of SCZ (for review, see ref.12). The ACC is involved in cognition, emotion, and self-reference,13 which are abnormal in SCZ. Reduced functional connectivity between the ACC and other brain regions has been linked to disturbed self-reference,14 gamma band coherence,15 and impaired cognitive function in SCZ.16 Impaired interaction within the default mode network (DMN), which encompasses the ACC as a node17,18 has also been reported in SCZ patients.19–22 Abnormal ACC glutamate and GABA levels have been reported across the illness course, in antipsychotic-treated, and drug-naive/off-medication samples, in proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies of SCZ.23–26 In concert with post-mortem and preclinical models of SCZ (reference here), this research supports altered anterior cingulate excitatory-inhibitory function.

Considering the involvement of glutamatergic and GABAergic systems in functional connectivity in the healthy brain (refs.10,11) and that these systems are altered in SCZ as measured non-invasively by MRS (for review, see ref.23), it is likely that these neurotransmitters systems are contributing to anterior cingulate functional connectivity alterations. In view of the existent evidence, we hypothesized that part of the ACC functional connectivity dysfunction in SCZ could be due to excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter dysfunction in SCZ as indexed by abnormal glutamate and/or GABA levels in the ACC. Therefore, this project combined resting state fMRI and MRS to assess the impact of ACC glutamate and GABA levels on ACC functional connectivity in SCZ compared to healthy controls (HC).

Methods

Participants

Fifty-eight SCZ patients were recruited from the outpatient clinics at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center and the neighboring mental health clinics. Sixty-one HC were recruited through media advertisements. Demographics of the sample are reported in table 1. Diagnoses were confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) for DSM-IV in all participants by Master’s level therapists followed up with consensus with psychiatrists, including co-authors L.E.H. and J.J.C. Major medical and neurological illnesses, history of head injury with cognitive sequelae, and mental retardation were exclusionary. Patients and HC with substance dependence within the past 6 months, or current substance abuse (except nicotine) were excluded. Controls had no current DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses and no family history of psychosis in the prior 2 generations. The majority of patients were taking antipsychotic medication. Nine patients were taking benzodiazepine medication as needed but were asked to refrain from taking the medication 24 hours prior to study visits. The medication status can be found in table 1. Participants gave written informed consent, and patients with SCZ were tested for capacity to consent prior to signing the consent form. The research protocol was approved by the University of Maryland Baltimore Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Demographic Data and Clinical Parameters for Schizophrenia (SCZ) and Healthy Control (HC) Groups

| SCZ (n = 58) | HC (n = 61) | Group comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P | |

| Age (range/ y) | 20–63/ 36.91 (12.88) | 21–61/ 37.66 (13.34) | .74 |

| Gender (M/F) | 44/14 | 35/26 | .07 |

| Smokers/nonsmokers | 25/33 | 21/40 | .33 |

| Schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis distribution | |||

| Schizophrenia | 44 | N/A | |

| Schizoaffective | 11 | ||

| Schizophreniform | 2 | ||

| Unknown | 1 | ||

| Illness course | |||

| SSD onset age | 20.78 (6.63) | N/A | |

| SSD duration of illness (y) | 15.43 (13.95) | ||

| Medications | |||

| Chlorpromazine equivalent units (CPZ) | 520.27 (465.21) | N/A | |

| First generation antipsychotics | 7 | ||

| Chlorpromazine | 1 | ||

| Fluphenazine | 4 | ||

| Haloperidol | 1 | ||

| Thiothixene | 1 | ||

| Second generation antipsychotics | 43 | ||

| Aripiprazole | 8 | ||

| Clozapine | 8 | ||

| Olanzapine | 5 | ||

| Paliperidone | 2 | ||

| Quentiapine | 2 | ||

| Risperidone | 10 | ||

| Ziprasidone | 1 | ||

| Apriprazole and Olanzapine | 1 | ||

| Risperidone and Abilify | 1 | ||

| Risperidone and Clozapine | 2 | ||

| Risperidone and Olanzapine | 1 | ||

| Risperidone and Paliperidone | 1 | ||

| Risperidone and Quetiapine | 1 | ||

| Combination | 6 | ||

| Fluphenazine and Quentiapine | 1 | ||

| Haloperidol and Clozapine | 1 | ||

| Haloperidol and Paliperidone | 1 | ||

| Haloperidol and Quentiapine | 1 | ||

| Haloperidol and Risperidone | 1 | ||

| Clozapine, Olanzapine and Paliperidone | 1 | ||

| No antipsychotic medications | 2 | ||

| Other psychotropic medications | |||

| Antidepressants | 22 | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 9 | ||

| Anticonvulsants | 9 | ||

| Symptom ratings | |||

| BPRS total | 35.33 (14.41) | ||

| Positive subscale | 9.93 (5.43) | ||

| Negative subscale | 5.31 (3.06) | ||

Data Acquisition

All imaging was performed at the University of Maryland Center for Brain Imaging Research using a Siemens 3T TRIO MRI system equipped with a 32-channel phase array head coil. High-resolution structural images were acquired using fast spoiled gradient-recalled sequence (TR: 11.08 ms, TE: 4.3 ms, flip angle: 45°, field of view [FOV]: 256 mm, 256 × 256 matrix, 172 slices, 1 mm3 spatial resolution). Resting-state functional T2*-weighted images were obtained using a single-shot gradient-recalled, echo-planar pulse sequence (TR: 2 s; TE: 30 ms; flip angle: 90°; FOV: 220 mm; 64 × 64 matrix; 3.4 mm2 in-plane resolution; 3.4 mm slice thickness; 42 axial slices; 15 min scan duration). Participants were asked to stay awake, keep their eyes closed, and asked not to think about anything in particular.

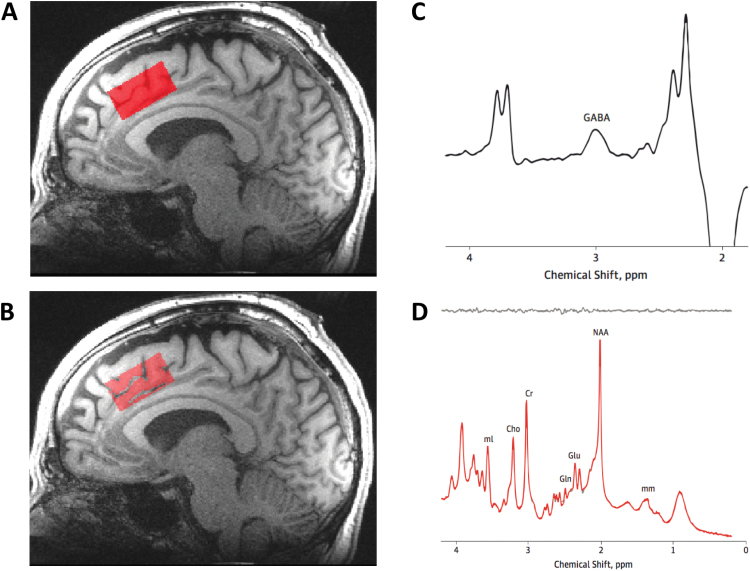

The spectroscopic voxel was 4.0 × 3.0 × 2.0 cm3 prescribed on the midsagittal slice and positioned parallel to the genu of the corpus callosum and scalp with the midline of the voxel corresponding to the middle of the genu of the corpus callosum. The voxel covered the ACC and a portion of the medial frontal cortex. Automated shimming followed by manual shimming was conducted to achieve approximately 12 Hz water linewidth. For detection of glutamate, spectra were acquired with a phase rotation STEAM (PR-STEAM)27,28: repetition time, mixing time, and echo time (TR/TM/TE) = 2000/10/6.5 ms, volume-of-interest ~ 24 cm3, number of excitations (NEX) = 128, 2.5 kHz spectral width, 2048 complex points, and phases: φ1 = 135°, φ2 = 22.5°, φ13 = 112.5°, φADC = 0°, which has been shown to be reproducible in healthy volunteers29 and participants with SCZ.30 A water reference (NEX = 16) was also acquired for phase and eddy current correction as well as quantification. For detection of GABA, spectra were acquired from the same voxel using a macromolecule-suppressed MEGA-PRESS sequence: TR = 2000, TE = 68 ms, 20.36 ms length and 44 Hz bandwidth full width at half maximum (FWHM) editing pulses applied at 1.9 (ON) and 1.5 (OFF) ppm, and 256 averages (128 ON and 128 OFF); water unsuppressed 16 averages.31,32 Water suppression was achieved using Siemens modified WET water suppression technique. See figure 1 for illustration of voxel placement and representative spectra.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of MRS anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) voxel placement and representative spectra.

MRS Data Analysis

For quantifying glutamate, a basis set of 19 metabolites was simulated using the GAVA software package33: alanine (Ala), aspartate (Asp), creatine (Cr), γ-aminobuytric acid (GABA), glucose (Glc), glutamate (Glu), glutamine (Gln), glutathione (GSH), glycine (Gly), glycerophosphocholine (GPC), lactate (Lac), myo-Inositol (mI), N-acetylaspartate (NAA), N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG), phosphocholine (PCh), phosphocreatine (PCr), phosphoroylethanolamine (PE), scyllo-Inositol (sI), and taurine (Tau). The basis set was imported into LCModel (6.3-0D) and used for quantification.34 The spectroscopic voxel was segmented into gray, white, and CSF tissues using SPM8 and in-house MATLAB code, and metabolite concentrations were corrected for the proportion of gray, white, and CSF tissue proportions.32,35 Metabolite levels are reported in institutional units, and metabolites with standard deviation Cramer Rao Lower Bounds (CRLBs) ≤ 20%, were included in statistical analyses.

GABA quantification was conducted with GANNET 2.0 toolkit, a Matlab program specifically developed for analysis of GABA MEGA-PRESS spectra.36 Individual spectra were frequency and phase corrected, and then “ON” and “OFF” subtracted resulting in the edited spectrum. The edited GABA peak was modeled as a single-Gaussian and values of GABA relative to water (modeled as a mixed Gaussian-Lorentzian) in institutional units were produced. The normalized fitting residual was calculated by dividing the standard deviation of the fitting residual by the amplitude of the fitted peak. Spectra were included if the normalized fitting residual of GABA was below 15%.

Functional Connectivity Analysis

Resting-state BOLD data were preprocessed using Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI)37 software. The correction for head motion was performed by registering each functional volume to the middle time point of the run. The preprocessed data were spatially smoothed to a full-width at half-maximum of 4 mm. Nuisance variables such as the linear trend, 6 motion parameters (3 rotational and 3 translational directions), their 6 temporal derivatives (rate of change in rotational and translational motion), and time courses from the white matter and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) from lateral ventricles were modeled using multiple linear regression analysis, which were then removed as regressors of no interest. Time points with excessive motion were estimated as the derivative of the motion parameters and the square root of sum of squares per TR.38 If this Euclidean Norm of the motion derivative exceeded the limit of 0.2, the TR was censored from the statistical analysis (on average 18 and 15 TRs in SCZ and HC groups, respectively). Head motion, as determined by the root mean square of the translational and rotational motion in 3 cardinal directions, was compared between groups. No significant group differences were detected for translational motion (0.55 ± 0.08 mm [mean ± SEM] SCZ and 0.59 ± 0.07 mm HC; P = .73) or rotational motion (0.014 ± 0.003 rad SCZ and 0.010 ± 0.002 rad HC; P = .29). Images were spatially normalized using nonlinear 3D warping approach to the Talairach space39 for group analysis. Seed-based functional connectivity maps were constructed by extracting the BOLD time series from the MRS voxel and calculating the temporal correlation between this reference waveform and the time courses of all other brain voxels. White matter and CSF were masked out from the MRS voxel. Global signal regression was not performed. Connectivity maps were normalized using Fisher’s r-to-z conversion.

Statistical Analysis

First, group differences in functional connectivity were assessed using a 2-sample 2-tailed t-test on the groups’ participant-level functional connectivity maps (AlphaSim corrected P < .05). Second, correlation analyses were conducted between functional connectivity and glutamate and GABA levels within the brain regions that were significant between-group differences in functional connectivity analyses. The significance of the correlation coefficient (Z-test) was also tested to determine whether the linear relationship in the sample data was strong enough to use to model the relationship in the population.40 A mixed-model ANOVA was used for the interaction analysis.

The bivariate association of whole-brain functional connectivity and glutamate and GABA levels were evaluated by linear regression analysis using ANFI’s 3dRegAna function within each group. The mean Z-score of the clusters demonstrating significant correlations with glutamate and GABA were extracted, and then the linear correlation analyses of the mean Z-score of these clusters and glutamate and GABA were performed. The continuous variables (glutamate and GABA) were grand mean-centered across the group to control for variations due to the preexisting group mean difference.41 Monte Carlo simulations (using AlphaSim in AFNI34) were performed for each analysis to correct for multiple comparisons at a voxel-wise significance of P < .005 with a minimum cluster size of 79 voxels.

Results

Glutamate and GABA

MRS quality measures. As reported by LCModel, the spectral quality was good with mean line widths (LW) of 0.033 (0.009) for controls and 0.39 (0.01) or patients and mean signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 35.1 (6.9) for controls and 35.0 (12.2) for patients. Spectral fits for glutamate were also good with mean %SD CRLBs of 4.6 (1.0) for controls and 5.0 (1.5) for patients. The quality measures did not significantly differ between groups (Ps = .12 for %SD and 0.91 for SNR), except for the LW (P < .05).

Glutamate levels, covarying for age, were significantly higher in controls compared to patients (P = .03). However, GABA levels were not significantly different between groups when covarying for age (P = .5).

Functional Connectivity Group Differences and Correlations With Glutamate and GABA

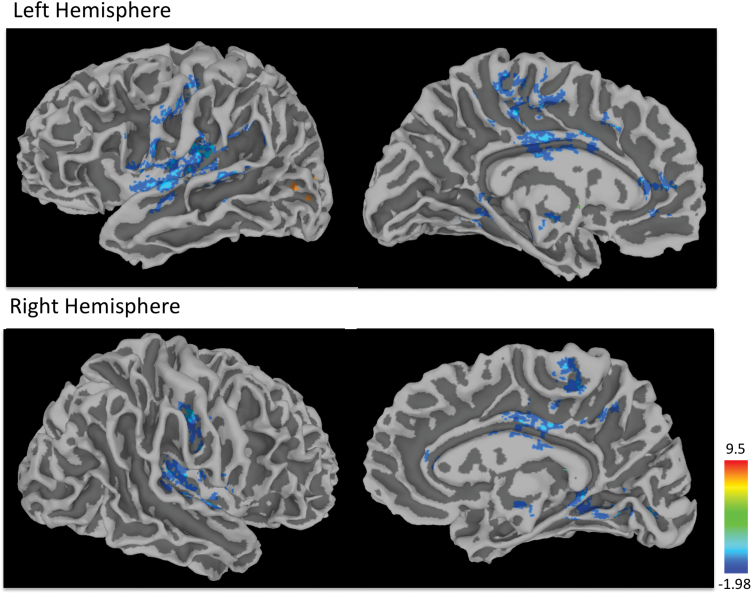

Reduced mPFC/ACC functional connectivity in the SCZ group compared to the HC group was found with the thalamus, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus in the left hemisphere, middle frontal gyrus in the right hemisphere and bilateral anterior cingulate, parahippocampal gyrus, insula, putamen, superior temporal gyrus, medial frontal gyrus, cingulate gyrus, lingual gyrus, and pre- and postcentral gyri (P = .05, corrected). Increased functional connectivity in the SCZ group was also observed in the left middle occipital gyrus (figure 2, table 2).

Fig. 2.

Clusters of significant group differences in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) functional connectivity. Negative values (blue clusters) represent reduced functional connectivity in the SCZ than in the HC group; negative values (yellow clusters) indicate inverse effects (SCZ > HC; all clusters P < .05, corrected). Color scale reflects T-scores. For color, please see the figure online.

Table 2.

Clusters of Significant Group Differences (P < .05; corrected) (Abbreviations: L, left; R, right)

| Peak location | Hemisphere | Talairach coordinates | Volume (voxels) | T-score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x y z | |||||

| SCZ < HC | Parahippocampal gyrus | L | 24 44 −5 | 375 | 4.3 |

| R | −30 32 −16 | 151 | 3.7 | ||

| Anterior cingulate | L | 1 −34 22 | 271 | 4.3 | |

| R | −2 −40 1 | 653 | 4.0 | ||

| Middle frontal gyrus | R | −42 −38 19 | 102 | 3.6 | |

| Insula | L | 37 22 11 | 4895 | 4.7 | |

| R | −38 12 9 | 279 | 3.9 | ||

| Putamen | L | 25 2 1 | 143 | 2.8 | |

| R | −32 9 3 | 245 | 3.1 | ||

| Thalamus | L | 7 29 16 | 205 | 4.1 | |

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 24 −5 −35 | 87 | 3.4 | |

| R | −51 8 8 | 1762 | 4.8 | ||

| Medial frontal gyrus | R | −3 −55 14 | 218 | 4.2 | |

| L | 1 −25 14 | 148 | 4.6 | ||

| Cingulate gurys | L | 10 29 46 | 2646 | 4.6 | |

| R | −3 −22 37 | 164 | 4.5 | ||

| Precentral gyrus | L | 42 13 47 | 473 | 4.2 | |

| R | −47 15 43 | 101 | 2.3 | ||

| Postcentral gyrus | L | 24 29 64 | 128 | 3.8 | |

| R | −48 19 40 | 598 | 4.3 | ||

| Posterior cingulate cortex | L | 1 74 11 | 118 | 3.5 | |

| Precuneus | L | 24 77 38 | 163 | 3.9 | |

| lingual gyrus | L | 21 50 2 | 122 | 3.5 | |

| R | −15 79 2 | 1165 | 4.2 | ||

| SCZ > HC | Middle occipital gyrus | L | 39 82 8 | 242 | 4.3 |

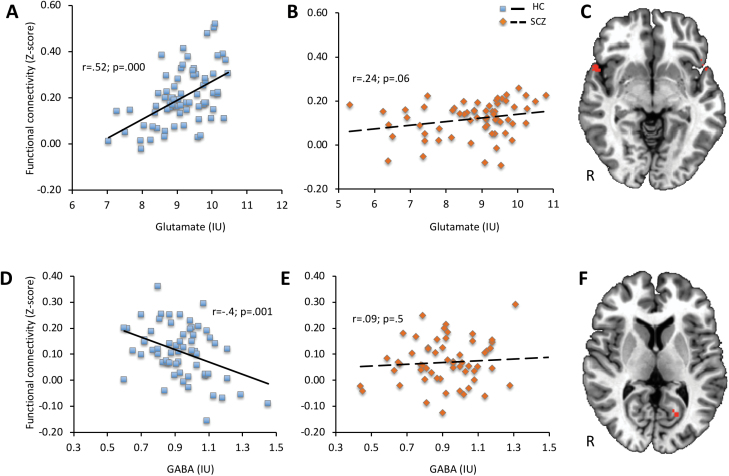

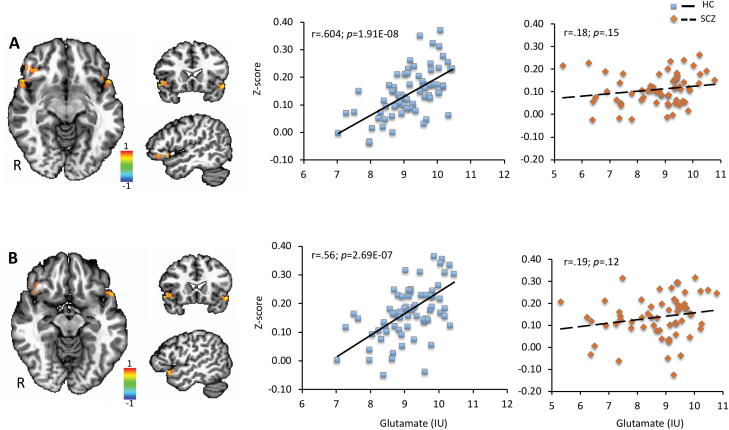

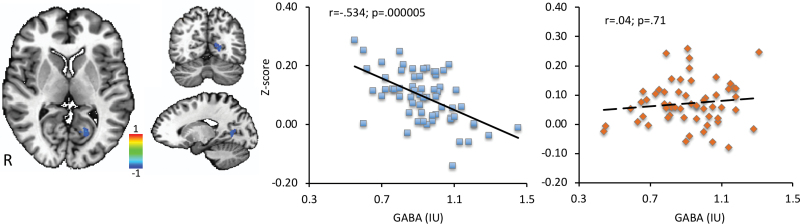

Correlation analyses were performed between functional connectivity Z-score and glutamate and GABA in brain regions with significant functional connectivity differences. A significant positive correlation between functional connectivity and glutamate was observed in bilateral superior temporal gyrus (r = .52; P < .0001) and a negative correlation between functional connectivity and GABA in the left posterior cingulate (r = −.4; P = 0.001) in HC, but no significant correlations were present in the SCZ group (figure 3). The Z-test showed a significant correlation coefficient difference between the SCZ and HC groups for the left posterior cingulate (Z = −2.72; P = .006).

Fig. 3.

Pearson correlation between resting-state anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) functional connectivity (Z-score) and glutamate in HC (A) and SCZ (B) groups in regions showing reduced functional connectivity in SCZ (C) and correlation between Z-score and GABA in HC (D) and SCZ (E) groups in regions showing reduced functional connectivity in SCZ (F).

Interaction Analyses

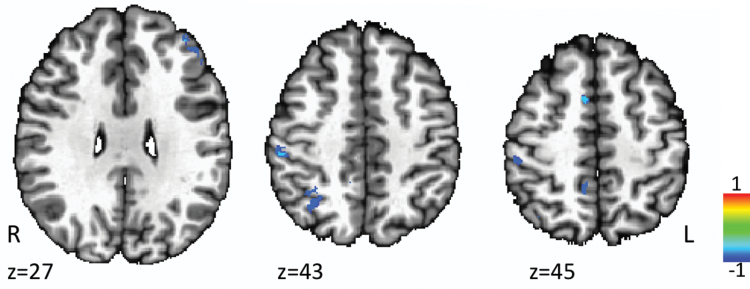

A mixed-model ANOVA with between-subject factor diagnosis (SCZ, HC) and within-subject factor metabolites (glutamate, GABA) was conducted on the functional connectivity obtained for the MRS voxel. The interaction between metabolites and diagnosis addressed the critical factor of glutamate and GABA relative effects on functional connectivity abnormalities. Interaction analyses revealed significant diagnosis × GABA interactions in the right medial frontal gyrus (F[19,118] = 3.3, P = .001), right inferior parietal lobule (F[19,118] = 3.3, P = .001), and right precuneus (F[19,118] = 3, P = .001) with HC displaying a negative correlation between functional connectivity and GABA (figure 4). There were no diagnosis × glutamate interactions. A diagnosis × glutamate × GABA interaction was found in the left anterior cingulate (figure 5). Post hoc analysis showed that the diagnosis × glutamate × GABA interaction was primarily driven by the significant negative correlation between functional connectivity and GABA in the left anterior cingulate in the HC group (r = −.26, P = .04; supplementary figure 1).

Fig. 4.

Diagnosis × GABA interaction analysis.

Fig. 5.

Diagnosis × glutamate × GABA interaction analysis (A) and scatter plot for HC (B) and SCZ (C) groups.

Regression Analysis of Glutamate and GABA Levels on Functional Connectivity

Regression analysis revealed significant positive correlations between glutamate and functional connectivity in the right inferior frontal gyrus (r = .604; P < .0001) and left superior temporal gyrus (r = .56; P < .0001) in HC (figure 6). A significant negative correlation between GABA and functional connectivity in the left posterior cingulate (r = −.534; P < .0001) in HC was also found (figure 7). However, no significant correlations between functional connectivity and GABA or glutamate for these regions were detected in the SCZ group (P > .05). The Z-test revealed significant differences between groups for the right inferior frontal gyrus (Z = 2.89; P = .003), bilateral superior temporal gyrus (Z = 2.47; P = .013), and the left posterior cingulate (Z = −3.48; P = .0005).

Fig. 6.

Regression analysis between resting-state anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) functional connectivity (Z-score) and glutamate showing positive correlations in (A) the right inferior frontal gyrus and (B) left superior temporal gyrus in healthy controls.

Fig. 7.

Regression analysis between resting-state anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) functional connectivity and GABA showing negative correlation in the left posterior cingulate in healthy controls.

Potential Confounds

Analyses using age, smoking, CPZ units, and gender as covariates did not change the level of significance.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the role of glutamate and GABA levels on resting-state functional connectivity in patients with SCZ. Our results support previous studies in HC showing associations between glutamate and GABA levels in the modulation of resting-state functional connectivity. However, in patients with SCZ, we observed that such associations were either not present or showed opposite effects.

Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, and a direct relationship between the glutamate/glutamine neurotransmitter cycle and synaptic glucose oxidation has been shown.42 This indicates that the majority of cortical energy production supports functional glutamatergic neuronal activity. Functional connectivity is a mathematical construct to measure statistical dependencies among remote neurophysiological events.43 Thus, a positive correlation between functional connectivity and glutamate observed in HC suggests that glutamate plays an important role in modulating hemodynamic responses. The lack of correlation between functional connectivity and glutamate in the SCZ group may reflect abnormal glutamatergic modulation of resting-state brain activity in SCZ. This abnormal modulation may stem from alterations in the glutamatergic system in SCZ, as supported by post-mortem and MRS research.23,44

We found a significant negative correlation between ACC functional connectivity and GABA levels in HC. This is consistent with previous neuroimaging studies45,46 and with research showing that large-scale resting-state networks are related to local oscillatory activity in the beta and gamma bands,47 which are generated by local GABAA synaptic activity.48 Given that abnormalities in GABAergic interneurons,49,50 GABA levels51 and GAD6752,53 have been observed in SCZ, it is not surprising that there are disturbances in the GABA relationship with functional connectivity in SCZ.

The present study has shown reduced functional connectivity in SCZ in several core DMN regions such as right posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, bilateral anterior cingulate, parahippocampal gyrus, and medial frontal gyrus and their abnormal association with glutamate and GABA levels. Altered DMN functional connectivity commonly observed in SCZ19–21 may contribute to social, emotional and introspective processes impairments in SCZ.54–56 The results of this study suggest that the relationship between GABA and glutamate and functional connectivity in DMN key regions is reduced in SCZ. For example, the superior temporal gyrus and posterior cingulate showed reduced connectivity in SCZ, which did not correlate with glutamate and GABA respectively. These regions are involved in social cognition,57–59 spatial attention, auditory and language processing.60 Hence, the absence of glutamate and GABA correlations with functional connectivity in these DMN areas where SCZ group showed significantly reduced functional connectivity may reflect abnormal excitatory or inhibitory modulation of functional connectivity in SCZ.

The interaction between glutamate/GABA levels and diagnosis provides greater insight into the role of glutamate/GABA levels on the atypical functional connectivity in SCZ. The glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons control the balance of excitation and inhibition in the cortex and are thought to participate in regulating the functional integrity and segregation of minicolumns through lateral inhibition of activity in neighboring minicolumns.61,62 A balance in excitation and inhibition is essential for the integration of synaptic inputs and the output from neurons, which affects neuronal circuit function and plasticity.5 Our results could reflect desynchronized neural activity in SCZ potentially due to less GABAergic activity resulting in disinhibition of glutamatergic neurons in the ACC.50,63

Potential limitations of the study include the antipsychotic and other psychotropic medication effects on the neuroimaging measures. Antipsychotic medications have been shown to modulate functional connectivity that involves the anterior cingulate region in studies that examine before and following a few weeks to a few months of antipsychotic treatment.64–67 Antipsychotic medications may also influence MRS measures of anterior cingulate GABA or glutamate, as suggested by some studies.68,69 Although the impact of CPZ units did not impact our results, this still remains a limitation. We tried to reduce the potential confound of benzodiazepines by excluding patients who take them regularly and having patients refrain from taking them within 24 hours of study visits. Second, the patient group was a mixture of recently and chronically ill with a range of symptom severity. Therefore, we cannot provide insight into how these measures are impacted by illness phase or specific domains of symptom pathology but encourage future studies to address these important issues. Third, MRS quantifies total glutamate and GABA tissue levels and cannot differentiate cytosolic, vesicular, synaptic, or extra-cellular glutamate and GABA levels. Therefore, total tissue levels of metabolites may not solely reflect neurotransmission. Fourth, the spectroscopic voxel encompassed both anterior cingulate and some medial frontal cortex; therefore, anatomical specificity of the results may be somewhat limited. Fifth, power analysis was not performed prior to the data analysis, and therefore some of the null findings may be because the study was underpowered. Finally, functional connectivity analysis lacks any information about the causality as it gives information only about whether the BOLD signal is more or less synchronized with that in the seed region.

The present investigation is one of the first studies to examine links between functional dysconnectivity and glutamate and GABA levels in SCZ. Our findings suggest that glutamate and GABA play an important role in the functional connectivity modulation in the healthy brain. Furthermore, impaired functional connectivity commonly observed in patients with SCZ may be partially explained by a neurochemistry-functional connectivity decoupling effect.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01MH094520, R01MH112180, R01DA027680, R01MH085646, U01MH108148, P50MH103222, and T32MH067533) and a State of Maryland contract (M00B6400091). We thank Dr Richard Edden and colleagues who kindly provided GANNET funded through NIH R01 EB016089 and P41 EB015909. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the volunteers, especially the patients, for participating in the study. D.K.S. and L.M.R. had full access to all of the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:700–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bressler SL, Kelso JA. Cortical coordination dynamics and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hadjipapas A, Hillebrand A, Holliday IE, Singh KD, Barnes GR. Assessing interactions of linear and nonlinear neuronal sources using MEG beamformers: a proof of concept. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:1300–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sheffield JM, Barch DM. Cognition and resting-state functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;61:108–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Polleux F, Lauder JM. Toward a developmental neurobiology of autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:303–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buzsáki G, Kaila K, Raichle M. Inhibition and brain work. Neuron. 2007;56:771–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fergus A, Lee KS. Regulation of cerebral microvessels by glutamatergic mechanisms. Brain Res. 1997;754:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muthukumaraswamy SD, Edden RA, Jones DK, Swettenham JB, Singh KD. Resting GABA concentration predicts peak gamma frequency and fMRI amplitude in response to visual stimulation in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8356–8361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature. 2001;412:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kraguljac NV, Frölich MA, Tran S et al. Ketamine modulates hippocampal neurochemistry and functional connectivity: a combined magnetic resonance spectroscopy and resting-state fMRI study in healthy volunteers. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duncan NW, Wiebking C, Tiret B et al. Glutamate concentration in the medial prefrontal cortex predicts resting-state cortical-subcortical functional connectivity in humans. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Squarcina L, Stanley JA, Bellani M, Altamura CA, Brambilla P. A review of altered biochemistry in the anterior cingulate cortex of first-episode psychosis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26:122–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van der Meer L, Costafreda S, Aleman A, David AS. Self-reflection and the brain: a theoretical review and meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies with implications for schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:935–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kühn S, Gallinat J. Resting-state brain activity in schizophrenia and major depression: a quantitative meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim JS, Shin KS, Jung WH, Kim SN, Kwon JS, Chung CK. Power spectral aspects of the default mode network in schizophrenia: an MEG study. BMC Neurosci. 2014;15:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou L, Pu W, Wang J et al. Inefficient DMN suppression in schizophrenia patients with impaired cognitive function but not patients with preserved cognitive function. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1083–1090; discussion 1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang H, Zeng LL, Chen Y, Yin H, Tan Q, Hu D. Evidence of a dissociation pattern in default mode subnetwork functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schilbach L, Hoffstaedter F, Müller V et al. Transdiagnostic commonalities and differences in resting state functional connectivity of the default mode network in schizophrenia and major depression. Neuroimage Clin. 2016;10:326–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manoliu A, Riedl V, Zherdin A et al. Aberrant dependence of default mode/central executive network interactions on anterior insular salience network activity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:428–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Du Y, Pearlson GD, Yu Q et al. Interaction among subsystems within default mode network diminished in schizophrenia patients: a dynamic connectivity approach. Schizophr Res. 2016;170:55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wijtenburg SA, Yang S, Fischer BA, Rowland LM. In vivo assessment of neurotransmitters and modulators with magnetic resonance spectroscopy: application to schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;51:276–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Merritt K, Egerton A, Kempton MJ, Taylor MJ, McGuire PK. Nature of glutamate alterations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:665–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Egerton A, Modinos G, Ferrera D, McGuire P. Neuroimaging studies of GABA in schizophrenia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marsman A, van den Heuvel MP, Klomp DW, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE. Glutamate in schizophrenia: a focused review and meta-analysis of ¹H-MRS studies. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:120–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Knight-Scott J, Shanbhag DD, Dunham SA. A phase rotation scheme for achieving very short echo times with localized stimulated echo spectroscopy. Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;23:871–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wijtenburg SA, Knight-Scott J. Very short echo time improves the precision of glutamate detection at 3T in 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wijtenburg SA, Gaston FE, Spieker EA et al. Reproducibility of phase rotation STEAM at 3T: focus on glutathione. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bustillo JR, Rediske N, Jones T, Rowland LM, Abbott C, Wijtenburg SA. Reproducibility of phase rotation stimulated echo acquisition mode at 3T in schizophrenia: emphasis on glutamine. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:498–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aufhaus E, Weber-Fahr W, Sack M et al. Absence of changes in GABA concentrations with age and gender in the human anterior cingulate cortex: a MEGA-PRESS study with symmetric editing pulse frequencies for macromolecule suppression. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rowland LM, Krause BW, Wijtenburg SA et al. Medial frontal GABA is lower in older schizophrenia: a MEGA-PRESS with macromolecule suppression study. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Soher BJ, Young K, Bernstein A, Aygula Z, Maudsley AA. GAVA: spectral simulation for in vivo MRS applications. J Magn Reson. 2007;185:291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30:672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gasparovic C, Song T, Devier D et al. Use of tissue water as a concentration reference for proton spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Edden RA, Puts NA, Harris AD, Barker PB, Evans CJ. Gannet: a batch-processing tool for the quantitative analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid–edited MR spectroscopy spectra. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40:1445–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Power JD, Mitra A, Laumann TO, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Methods to detect, characterize, and remove motion artifact in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2014;84:320–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Talairach I, Tournoux P.. Co-Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Steiger JH. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;87:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen G, Adleman NE, Saad ZS, Leibenluft E, Cox RW. Applications of multivariate modeling to neuroimaging group analysis: a comprehensive alternative to univariate general linear model. Neuroimage. 2014;99:571–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sibson NR, Dhankhar A, Mason GF, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Shulman RG. Stoichiometric coupling of brain glucose metabolism and glutamatergic neuronal activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Friston KJ. Functional and effective connectivity: a review. Brain Connect. 2011;1:13–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hu W, MacDonald ML, Elswick DE, Sweet RA. The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia: evidence from human brain tissue studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1338:38–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kapogiannis D, Reiter DA, Willette AA, Mattson MP. Posteromedial cortex glutamate and GABA predict intrinsic functional connectivity of the default mode network. Neuroimage. 2013;64:112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stagg CJ, Bachtiar V, Amadi U et al. Local GABA concentration is related to network-level resting functional connectivity. Elife. 2014;3:e01465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cabral J, Hugues E, Sporns O, Deco G. Role of local network oscillations in resting-state functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2011;57:130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hall SD, Stanford IM, Yamawaki N et al. The role of GABAergic modulation in motor function related neuronal network activity. Neuroimage. 2011;56:1506–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Benes FM, Berretta S. GABAergic interneurons: implications for understanding schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:312–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rowland L, Bustillo JR, Lauriello J. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (H-MRS) studies of schizophrenia. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2001;6:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Akbarian S, Huntsman MM, Kim JJ et al. GABAA receptor subunit gene expression in human prefrontal cortex: comparison of schizophrenics and controls. Cereb Cortex. 1995;5:550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM et al. Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a postmortem brain study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gusnard DA, Raichle ME, Raichle ME. Searching for a baseline: functional imaging and the resting human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Harrison BJ, Pujol J, López-Solà M et al. Consistency and functional specialization in the default mode brain network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9781–9786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim AS. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:489–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Takahashi H, Koeda M, Oda K et al. An fMRI study of differential neural response to affective pictures in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1247–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Adolphs R. Is the human amygdala specialized for processing social information?Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;985:326–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bigler ED, Mortensen S, Neeley ES et al. Superior temporal gyrus, language function, and autism. Dev Neuropsychol. 2007;31:217–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mesulam MM, Nobre AC, Kim YH, Parrish TB, Gitelman DR. Heterogeneity of cingulate contributions to spatial attention. Neuroimage. 2001;13:1065–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lund JS, Angelucci A, Bressloff PC. Anatomical substrates for functional columns in macaque monkey primary visual cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Peters A, Sethares C. The organization of double bouquet cells in monkey striate cortex. J Neurocytol. 1997;26:779–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Coyle JT, Basu A, Benneyworth M, Balu D, Konopaske G. Glutamatergic synaptic dysregulation in schizophrenia: therapeutic implications. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012;213:267–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sarpal DK, Robinson DG, Lencz T et al. Antipsychotic treatment and functional connectivity of the striatum in first-episode schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kraguljac NV, White DM, Hadley N et al. Aberrant hippocampal connectivity in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia and effects of antipsychotic medication: a longitudinal resting state functional MRI study. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:1046–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sambataro F, Blasi G, Fazio L et al. Treatment with olanzapine is associated with modulation of the default mode network in patients with Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:904–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wang Y, Tang W, Fan X et al. Resting-state functional connectivity changes within the default mode network and the salience network after antipsychotic treatment in early-phase schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. de la Fuente-Sandoval C, Reyes-Madrigal F, Mao X et al. Prefrontal and striatal gamma-aminobutyric acid levels and the effect of antipsychotic treatment in first-episode psychosis patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83:475–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kegeles LS, Mao X, Stanford AD et al. Elevated prefrontal cortex γ-aminobutyric acid and glutamate-glutamine levels in schizophrenia measured in vivo with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.