Abstract

Background

Efficacy and the risk of severe late effects have to be well‐balanced in treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). Late adverse effects include secondary malignancies which often have a poor prognosis. To synthesise evidence on the risk of secondary malignancies after current treatment approaches comprising chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, we performed a meta‐analysis based on individual patient data (IPD) from patients treated for newly diagnosed HL.

Objectives

We investigated several questions concerning possible changes in the risk of secondary malignancies when modifying chemotherapy or radiotherapy (omission of radiotherapy, reduction of the radiation field, reduction of the radiation dose, use of fewer chemotherapy cycles, intensification of chemotherapy). We also analysed whether these modifications affect progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

Search methods

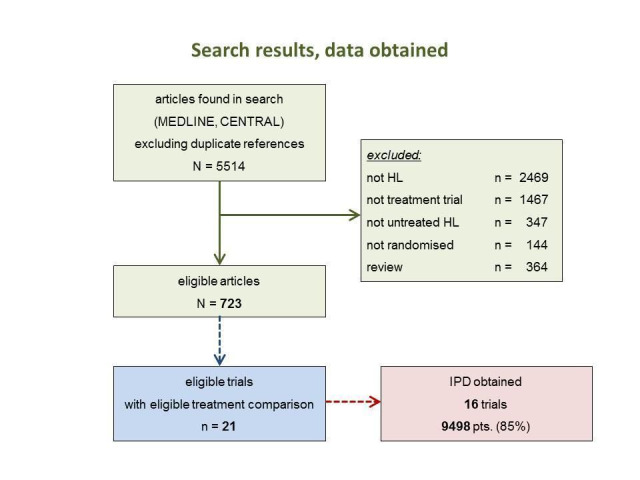

We searched MEDLINE and Cochrane CENTRAL trials databases comprehensively in June 2010 for all randomised trials in HL since 1984. Key international trials registries were also searched. The search was updated in March 2015 without collecting further IPD (one further eligible study found) and again in July 2017 (no further eligible studies).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for untreated HL patients which enrolled at least 50 patients per arm, completed recruitment by 2007 and performed a treatment comparison relevant to our objectives.

Data collection and analysis

Study groups submitted IPD, including age, sex, stage and the outcomes secondary malignant neoplasm (SMN), OS and PFS as time‐to‐event data. We meta‐analysed these data using Petos method (SMN) and Cox regression with inverse‐variance pooling (OS, PFS) for each of the five study questions, and performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses to assess the applicability and robustness of the results.

Main results

We identified 21 eligible trials and obtained IPD for 16. For four studies no data were supplied despite repeated efforts, while one study was only identified in 2015 and IPD were not sought. For each study question, between three and six trials with between 1101 and 2996 participants in total and median follow‐up between 6.7 and 10.8 years were analysed. All participants were adults and mainly under 60 years. Risk of bias was assessed as low for the majority of studies and outcomes.

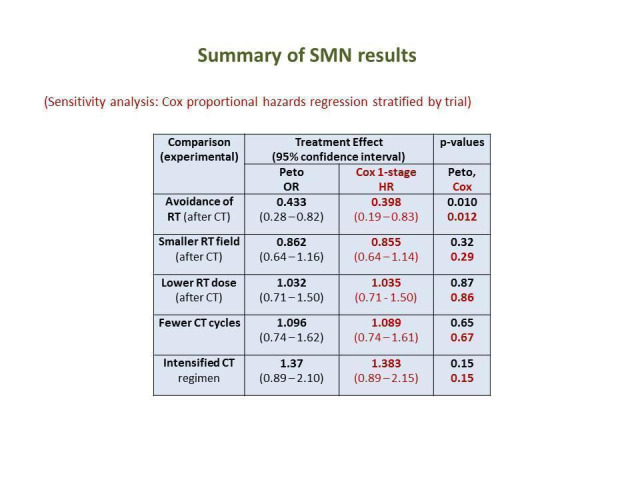

Chemotherapy alone versus same chemotherapy plus radiotherapy. Omitting additional radiotherapy probably reduces secondary malignancy incidence (Peto odds ratio (OR) 0.43, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.23 to 0.82, low quality of evidence), corresponding to an estimated reduction of eight‐year SMN risk from 8% to 4%. This decrease was particularly true for secondary acute leukemias. However, we had insufficient evidence to determine whether OS rates differ between patients treated with chemotherapy alone versus combined‐modality (hazard ratio (HR) 0.71, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.11, moderate quality of evidence). There was a slightly higher rate of PFS with combined modality, but our confidence in the results was limited by high levels of statistical heterogeneity between studies (HR 1.31, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.73, moderate quality of evidence).

Chemotherapy plus involved‐field radiation versus same chemotherapy plus extended‐field radiation (early stages). There is insufficient evidence to determine whether smaller radiation field reduces SMN risk (Peto OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.16, low quality of evidence), OS (HR 0.89, 95% C: 0.70 to 1.12, high quality of evidence) or PFS (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.21, high quality of evidence).

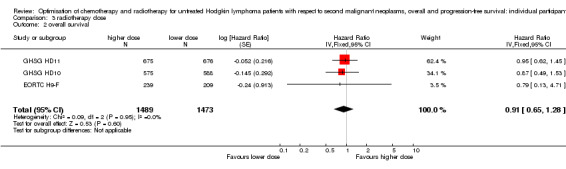

Chemotherapy plus lower‐dose radiation versus same chemotherapy plus higher‐dose radiation (early stages). There is insufficient evidence to determine the effect of lower‐radiation dose on SMN risk (Peto OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.50, low quality of evidence), OS (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.28, high quality of evidence) or PFS (HR 1.20, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.48, high quality of evidence).

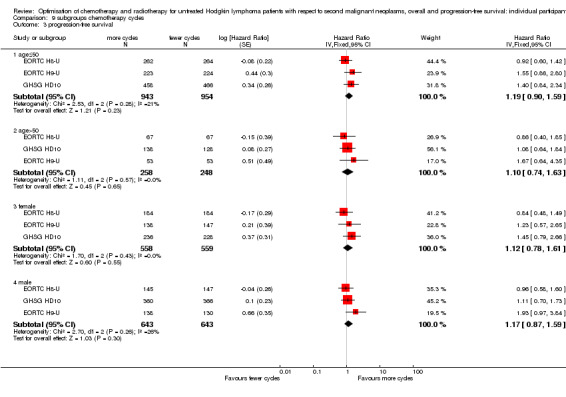

Fewer versus more courses of chemotherapy (each with or without radiotherapy; early stages). Fewer chemotherapy courses probably has little or no effect on SMN risk (Peto OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.62), OS (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.73 to1.34) or PFS (HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.45).Outcomes had a moderate (SMN) or high (OS, PFS) quality of evidence.

Dose‐intensified versus ABVD‐like chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy in each case). In the mainly advanced‐stage patients who were treated with intensified chemotherapy, the rate of secondary malignancies was low. There was insufficient evidence to determine the effect of chemotherapy intensification (Peto OR 1.37, CI 0.89 to 2.10, low quality of evidence). The rate of secondary acute leukemias (and for younger patients, all secondary malignancies) was probably higher than among those who had treatment with standard‐dose ABVD‐like protocols. In contrast, the intensified chemotherapy protocols probably improved PFS (eight‐year PFS 75% versus 69% for ABVD‐like treatment, HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.7 to 0.95, moderate quality of evidence). Evidence suggesting improved survival with intensified chemotherapy was not conclusive (HR: 0.85, CI 0.70 to 1.04), although escalated‐dose BEACOPP appeared to lengthen survival compared to ABVD‐like chemotherapy (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.79, moderate quality of evidence).

Generally, we could draw valid conclusions only in terms of secondary haematological malignancies, which usually occur less than 10 years after initial treatment, while follow‐up within the present analysis was too short to record all solid tumours.

Authors' conclusions

The risk of secondary acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome (AML/MDS) is increased but efficacy is improved among patients treated with intensified chemotherapy protocols. Treatment decisions must be tailored for individual patients. Consolidating radiotherapy is associated with an increased rate of secondary malignancies; therefore it appears important to define which patients can safely be treated without radiotherapy after chemotherapy, both for early and advanced stages. For early stages, treatment optimisation methods such as use of fewer chemotherapy cycles and reduced field or reduced‐dose radiotherapy did not appear to markedly affect efficacy or secondary malignancy risk. Due to the limited amount of long‐term follow‐up in this meta‐analysis, further long‐term investigations of late events are needed, particularly with respect to secondary solid tumours. Since many older studies have been included, possible improvement of radiotherapy techniques must be considered when interpreting these results.

Plain language summary

Optimisation of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma patients with respect to second cancers and survival

Review question

We aimed to compare various forms of treatment for newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma involving chemotherapy with or without additional radiotherapy. We particularly looked at the risk of second cancers caused by these treatments, although survival and elimination of Hodgkin lymphoma were also investigated.

Background

Since Hodgkin lymphoma often afflicts young people and highly effective treatments allow most patients to survive long after their diagnosis, curing the disease has to be weighed against the risk of causing long‐term adverse effects. Second cancers are a particularly severe form of late toxicity after chemotherapy and radiotherapy. We performed a meta‐analysis based on individual patient data from patients treated for newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma in order to compare second cancer risk, survival and Hodgkin‐free survival with various treatment options. These options included: (1) used of chemotherapy with or without additional radiotherapy; (2) use of a more extensive or more restricted radiation field; (3) use of a higher or lower radiation dose; (4) use of more or fewer courses of chemotherapy and (5) use of standard‐dose or dose‐intensified types of chemotherapy.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to July 2017, based on a total of 16 clinical trials which treated people between 1984 and 2007. Four eligible trials were excluded due to failure to obtain individual patient data, while one further eligible trial was identified only in 2015 and data were not sought. For each of the five study questions (see above), data from between three and six trials with between 1101 and 2996 participants were analysed. Each trial's data covered a follow‐up period of between six and 11 years. All included trials employed modern, widely accepted forms of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Patients were non‐elderly adults of both sexes with early or advances stage disease, according to study question. All trials were funded by public bodies or charities without any direct industry funding.

Key results

In the comparison of chemotherapy alone versus same chemotherapy plus radiotherapy (all stages), the use of chemotherapy without additional radiotherapy was associated with a lower second cancer risk but possibly at the cost of more growth or regrowth of the disease.

In the comparison of chemotherapy plus involved‐field radiation versus same chemotherapy plus extended‐field radiation (early stages), neither second cancer risk, survival or Hodgkin‐free survival was markedly different.

In the comparison of chemotherapy plus lower‐dose radiation versus same chemotherapy plus higher‐dose radiation (early stages), neither second cancer risk, survival or Hodgkin‐free survival was markedly different.

In the comparison of fewer versus more courses of chemotherapy (early stages), neither second cancer risk, survival or Hodgkin‐free survival was markedly different.

In the comparison of dose‐intensified versus ABVD‐like chemotherapy (advanced stages), dose‐intensified chemotherapy improved Hodgkin‐free survival, compared with ABVD‐like regimens, at the cost of a greater risk of secondary leukaemia. Evidence suggesting improved survival with intensified chemotherapy was not conclusive, although escalated‐dose BEACOPP appeared to lengthen survival.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence concerning survival and Hodgkin‐free survival was of at least moderate quality, while evidence concerning second cancer risk was partly of low quality due to the small numbers of second cancers observed in the trials and too short follow‐up. Thus, conclusions on second cancer risk remain tentative until more longer‐term data are available. Since many older studies have been included, possible improvement of radiotherapy techniques must be considered when interpreting these results.

The risk of secondary leukaemia is increased among patients treated with intensified chemotherapy protocols; on the other hand these regimens improve Hodgkin‐free survival. Treatment decisions have to be tailored for the individual patients. Consolidating radiotherapy is associated with an increased rate of secondary malignancies; therefore it appears important to define a patient population that can safely be treated without radiotherapy after chemotherapy, both for early and advanced stages. For early stages, treatment optimisation methods such as use of fewer chemotherapy cycles and reduced field or reduced dose radiotherapy did not appear to markedly affect Hodgkin‐free survival or secondary malignancy risk.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Chemotherapy alone versus same chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

| Chemotherapy alone versus same chemotherapy plus radiotherapy | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with untreated Hodgkin lymphoma (early and advanced stages) Settings: Typical clinical trial populations (mainly adult, non‐elderly) Intervention: Chemotherapy alone Comparison: Chemotherapy plus radiation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Chemotherapy plus radiation | Chemotherapy alone | |||||

| Secondary malignant neoplasms Follow‐up: median 7.8 years | Low1 | OR 0.43 (0.23 to 0.82) | 1011 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,5 | ||

| 4 per 100 | 2 per 100 (1 to 3) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 8 per 100 | 4 per 100 (2 to 7) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 12 per 100 | 6 per 100 (3 to 10) | |||||

| Death Follow‐up: median 7.8 years | Low1 | HR 0.71 (0.46 to 1.11) | 1011 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | reported as 'Overall Survival' | |

| 5 per 100 | 4 per 100 (2 to 6) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 10 per 100 | 7 per 100 (5 to 11) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 20 per 100 | 15 per 100 (10 to 22) | |||||

| Progression/relapse Follow‐up: median 7.8 years | Low1 | HR 1.31 (0.99 to 1.73) | 1011 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | reported as 'PFS' | |

| 15 per 100 | 19 per 100 (15 to 25) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 20 per 100 | 25 per 100 (20 to 32) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 25 per 100 | 31 per 100 (25 to 39) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 'Moderate' control risks are based on overall estimated rate at median observation time. 'Low' and 'high' control risks were chosen to represent the range of risks seen in the individual studies. 2 Few SMN events: downgrade imprecision by 1 point 3 Rather few deaths: downgrade imprecision by 1 point 4 Early‐ and advanced‐stage effects qualitatively different: downgrade inconsistency by 1 point

5 Follow‐up too short, in particular for assessment of solid tumour risk: downgrade by 1 point

Summary of findings 2. Chemotherapy plus involved‐field radiation versus same chemotherapy plus extended‐field radiation.

| Chemotherapy plus involved‐field radiation versus same chemotherapy plus extended‐field radiation | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with untreated Hodgkin lymphoma (early stages) Settings: Typical clinical trial populations (mainly adult, non‐elderly) Intervention: Involved field radiation (after chemotherapy) Comparison: Extended‐field radiation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Extended‐field radiation | Involved field radiation (after chemotherapy) | |||||

| Secondary malignant neoplasms Follow‐up: median 10.8 years | Low1 | OR 0.86 (0.64 to 1.16) | 2397 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 5 per 100 | 4 per 100 (3 to 6) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 10 per 100 | 9 per 100 (7 to 11) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 15 per 100 | 13 per 100 (10 to 17) | |||||

| Death Follow‐up: median 10.8 years | Low1 | HR 0.89 (0.70 to 1.12) | 2397 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | reported as 'Overall Survival' | |

| 10 per 100 | 9 per 100 (7 to 11) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 15 per 100 | 13 per 100 (11 to 17) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 20 per 100 | 18 per 100 (14 to 22) | |||||

| Progression/relapse Follow‐up: median 10.8 years | Low1 | HR 0.99 (0.81 to 1.21) | 2397 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | reported as 'PFS' | |

| 15 per 100 | 15 per 100 (12 to 18) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 20 per 100 | 20 per 100 (17 to 24) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 25 per 100 | 25 per 100 (21 to 29) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 'Moderate' control risks are based on overall estimated rate at median observation time. 'Low' and 'high' control risks were chosen to represent the range of risks seen in the individual studies. 2 Heterogeneous (I² = 67%): downgrade inconsistency by 1 point 3Follow‐up too short, in particular for assessment of solid tumour risk: downgrade by 1 point

Summary of findings 3. Chemotherapy plus lower‐dose radiation versus same chemotherapy plus higher‐dose radiation.

| Chemotherapy plus lower‐dose radiation versus same chemotherapy plus higher‐dose radiation | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with untreated Hodgkin lymphoma (early stages) Settings: Typical clinical trial populations (mainly adult, non‐elderly) Intervention: A lower radiotherapy dose | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | A lower radiotherapy dose | |||||

| Secondary malignant neoplasms Follow‐up: median 7.4 years | Low1 | OR 1.03 (0.71 to 1.5) | 2962 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 2 per 100 | 2 per 100 (1 to 3) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 4 per 100 | 4 per 100 (3 to 6) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 8 per 100 | 8 per 100 (6 to 12) | |||||

| Death Follow‐up: median 7.4 years | Low1 | HR 0.91 (0.65 to 1.28) | 2962 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | reported as 'Overall Survival' | |

| 3 per 100 | 3 per 100 (2 to 4) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 6 per 100 | 5 per 100 (4 to 8) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 12 per 100 | 11 per 100 (8 to 15) | |||||

| Progression/relapse Follow‐up: median 7.4 years | Low1 | HR 1.2 (0.97 to 1.48) | 2962 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | reported as 'PFS' | |

| 8 per 100 | 10 per 100 (8 to 12) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 12 per 100 | 14 per 100 (12 to 17) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 16 per 100 | 19 per 100 (16 to 23) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 'Moderate' control risks are based on overall estimated rate at median observation time. 'Low' and 'high' control risks were chosen to represent the range of risks seen in the individual studies. 2 Downgrade inconsistency one point due to heterogeneity (I2= 72%) 3Follow‐up too short, in particular for assessment of solid tumour risk: downgrade by 1 point

Summary of findings 4. Fewer versus more courses of chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy in each case).

| Fewer versus more courses of chemotherapy | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with untreated Hodgkin lymphoma (early stages) Settings: Typical clinical trial populations (mainly adult, non‐elderly) Intervention: Fewer chemotherapy cycles | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Fewer chemotherapy cycles | |||||

| Secondary malignant neoplasms Follow‐up: median 7.8 years | Low1 | OR 1.10 (0.74 to 1.62) | 2403 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| 2 per 100 | 2 per 100 (1 to 3) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 4 per 100 | 4 per 100 (3 to 6) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 8 per 100 | 9 per 100 (6 to 12) | |||||

| Death Follow‐up: median 7.8 years | Low1 | HR 0.99 (0.73 to 1.34) | 2403 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | reported as 'Overall Survival' | |

| 3 per 100 | 3 per 100 (2 to 4) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 6 per 100 | 6 per 100 (4 to 8) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 12 per 100 | 12 per 100 (9 to 16) | |||||

| Progression/relapse Follow‐up: median 7.8 years | Low1 | HR 1.15 (0.91 to 1.45) | 2403 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | reported as 'PFS' | |

| 8 per 100 | 9 per 100 (7 to 11) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 12 per 100 | 14 per 100 (11 to 17) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 16 per 100 | 18 per 100 (15 to 22) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 'Moderate' control risks are based on overall estimated rate at median observation time. 'Low' and 'high' control risks were chosen to represent the range of risks seen in the individual studies. 2Follow‐up too short, in particular for assessment of solid tumour risk: downgrade by 1 point

Summary of findings 5. Dose‐intensified chemotherapy versus ABVD‐like chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy in each case).

| Dose‐intensified chemotherapy versus ABVD‐like chemotherapy | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with untreated Hodgkin lymphoma (advanced stages) Settings: Typical clinical trial populations (mainly adult, non‐elderly) Intervention: Intensified chemotherapy Comparison: ABVD‐like chemotherapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| ABVD‐like chemotherapy | Intensified chemotherapy | |||||

| Secondary malignant neoplasms Follow‐up: median 6.7 years | Low1 | OR 1.37 (0.89 to 2.10) | 2996 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | ||

| 2 per 100 | 3 per 100 (2 to 4) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 4 per 100 | 5 per 100 (4 to 8) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 8 per 100 | 11 per 100 (7 to 15) | |||||

| Death Follow‐up: median 6.7 years | Low1 | HR 0.85 (0.70 to 1.04) | 2996 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | reported as 'Overall Survival' | |

| 10 per 100 | 9 per 100 (7 to 10) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 15 per 100 | 13 per 100 (11 to 16) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 20 per 100 | 17 per 100 (14 to 21) | |||||

| Progression/relapse Follow‐up: median 6.7 years | Low1 | HR 0.82 (0.70 to 0.95) | 2996 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | reported as 'PFS' | |

| 20 per 100 | 17 per 100 (14 to 19) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 30 per 100 | 25 per 100 (22 to 29) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 40 per 100 | 34 per 100 (30 to 38) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 'Moderate' control risks are based on overall estimated rate at median observation time. 'Low' and 'high' control risks were chosen to represent the range of risks seen in the individual studies. 2 Rather few SMN events: downgrade imprecision by 1 point 3 Downgrade inconsistency one point due to heterogeneity (I2 = 63% and 85%)

4 Follow‐up too short, in particular for assessment of solid tumour risk: downgrade by 1 point

Background

Description of the condition

Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) is a malignancy of the lymph nodes and lymphatic system with possible involvement of other organs (Mauch 1999; De Vita 2000). The disease is rare, with an annual incidence of approximately 3 per 100,000 in most countries, although in certain low‐income countries the incidence in children is higher and Epstein Barr virus (EBV) association and mixed cellularity subtype are more frequent (Mueller 1999). Most sufferers are young people, the incidence being greatest in the third decade of life (Mueller 1999). The malignant cells stem from lymphocytes, but the causes of the malignancy are poorly understood (De Vita 2000). Untreated, HL is fatal within a few years in most cases, but today the large majority of patients are cured.

Description of the intervention

Treatment strategies are determined by the disease stage and other prognostic factors. Early‐stage patients without adverse factors usually receive a combination of mild chemotherapy (two to three cycles) and limited radiotherapy (GHSG HD10; EORTC H8‐U) . Early‐stage patients with adverse prognostic factors are usually treated with moderate chemotherapy (four to six cycles) combined with radiotherapy (von Treskow 2012; EORTC H8‐U). Advanced‐stage patients receive intensive chemotherapy, typically six to eight cycles, with or without additional radiation (Engert 2012; MF‐GITIL‐IIL; Canellos 2009). The optimal treatment strategy is still controversial. Relevant criteria include (a) efficacy in controlling HL; (b) options and prognosis for second‐line therapy for those for whom first‐line treatment fails; and (c) acute toxicity, late effects and quality of life. As cure rates of HL patients have dramatically improved over recent decades, so that today the great majority of even advanced‐stage patients reach a lasting complete remission, treatment toxicity and subsequent quality of life have increased in importance. Strategies to reduce late toxicity and improve long‐term quality of life include avoidance of irradiation, reduction of irradiation fields or dose, reduction of number of chemotherapy cycles and avoidance of certain drugs such as alkylating agents or bleomycin. Recently, positron emission tomography (PET) has been employed during treatment to more reliably assess tumour status and thus identify patients requiring less or further treatment, thus reducing the treatment burden for a subgroup of patients.

The carcinogenic effects of ionising radiation were demonstrated in the 1930s, and since then its potential for causing almost any kind of cancer has been demonstrated (Boice 1988). Risks appear to be higher for young people. At low doses the risk increases linearly with dose. At therapeutic doses a further increase in risk with dose was seen in certain sites but not in others. In contrast, the carcinogenicity of chemotherapy was only discovered in the 1960s with the development of effective combination regimens. Further, radiologic imaging (especially computed tomography and PET) for staging and restaging purposes may also contribute slightly to the risk of secondary malignant neoplasm (Beyan 2007). Due to the high rate of cure of HL patients and their predominantly young age at diagnosis, they have ample 'opportunity' to develop treatment‐related secondary malignancies.

How the intervention might work

Secondary malignant neoplasms are perhaps the most serious late effect of treatment (Henry‐Amar 1996). Secondary malignant neoplasms can be divided into three classes. These are acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome (AML/MDS), non‐Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) and solid tumours. Secondary AML/MDS occur typically three to eight years after chemotherapy treatment, reaching a cumulative risk of one to three per cent in most studies. Secondary NHL occurs at a constant rate of about 0.2% per year independent of treatment type. Secondary solid tumours usually occur later, typically five to 20 years after treatment, with no evidence of a decline in incidence even after 20 years. Cumulative incidences of up to 34% have been estimated, representing a relative risk of up to five compared with the general population. Solid tumours appear to occur after both radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The impact of secondary malignant neoplasms on the long‐term survival of HL patients is considerable as long‐term survival rates especially for patients who develop therapy‐related leukaemia are poor. (Henry‐Amar 1992).

Why it is important to do this review

The effect of treatment modality on secondary malignant neoplasm rates has been investigated in several analyses of large data sets, including many analyses that were pooled over several patient cohorts. Case‐control studies have also been performed, particularly for investigations of specific types of secondary malignant neoplasm (SMN). Characteristics and key results of all identified studies which analysed at least 50 secondary malignant neoplasms or at least 20 secondary malignant neoplasms of a particular type (that is, AML, NHL or a certain solid tumour site) are summarised in Table 6 (all SMN), Table 7 (secondary solid tumours and NHL) and Table 8 (AML/MDS). Other authors, such as Aleman 2003, investigated long‐term cause‐specific mortality after HL, including the relationship between secondary malignant neoplasms and treatment modality. The relationship between treatment and secondary malignant neoplasm risk has been reviewed by Henry‐Amar 1993, Tucker 1993 and Ng 2004. Whilst it is widely accepted that AML is largely chemotherapy‐induced and NHL is largely independent of treatment modality, it is unclear which, if any, treatment modality can help to avoid solid tumours. The conclusions of the various investigators who compared solid tumour risks after various treatment modalities are far from unanimous. The situation is complicated by the large number of anatomic sites at which a solid tumour can occur as well as by the much higher risk of solid tumour in the general population compared with the very low risk of AML/MDS and NHL. Further, this risk varies widely according to age, sex and other personal and environmental factors. The quality and quantity of relevant data on solid tumour incidence is limited because of their very late occurrence.

1. Previous investigations of secondary malignant neoplasms: all types.

| Publication | Characteristics | Number of incident cases | Treatment groups | Analysis methods | Conclusions (all types) | Conclusions solid tumours | Conclusions (AML) | Conclusions (NHL) |

| Bhatia 1996 | 15 centres (USA, Manchester, Amsterdam); 1955‐1986; MFU = 11.4 yrs.; N = 1 380 (children < 16 yrs.) | 88 SMN (+9 excluded non‐melanoma skin cancers); 24 AML (+2 other leukaemias), 47 ST, 9 NHL | RT, CT, RT+CT (total treatment) | Cox regression separately for ST, AML, NHL | All ST: no differences; breast cancer only: RT dose (RR 5.9 for dose > 20 Gy) | No differences reported | Higher risk with more alkylating agents | |

| Biti 1994 | 1 centre (Florence); 1960‐1988; N = 1 121 | 73 SMN (+5 excluded basocellular skin cancers); 60 ST, 11 AML (MDS excluded), 2 NHL |

(A) RT, CT, RT+CT, CRT; total treatment. (B) RT, CT, CRT (primary treatment only), censored at relapse |

Cox regression | Higher risk after primary CT compared with IF/M alone; higher risk with CT+(S)TNI compared with IF/M alone | Same trend as for all SM | Higher risk with primary CT (±RT); higher risk with more cycles of CT | |

| Boivin 1995 | Embedded case‐control study; 14 Canadian and US centres; 1940‐1987; MFU = 7 yrs.; N = 10 472 (9 280 followed for at least one year) | 560 SMN; 403 ST, 122 AML, 35 NHL | RT, CT as time‐dependent variables, primary and salvage RT, CT | Cox regression with splenectomy, RT, CT as time‐dependent covariates | Significantly more with CT than without CT (ST and NHL analysed together) | Significantly more with CT than without CT (more with MOPP than with ABVD) | ||

| Dietrich 1994 | 1 centre (France); 1960‐1983; N = 892 (continuously disease‐free HD only) | N = 56 (first FU ‐year excluded); 37 ST (excluding bcc), 11 ANLL/MDS, 8 NHL | RT versus CRT; Mantle‐RT versus EF‐RT; SM before progression/relapse only | Cox regression; All RR compared with IF (= MF/inverted Y‐RT) | Significant excess only with MOPP+EF (RR 10.86, P < 0.001) and MOPP+IF (RR 4.99, P = 0.015). | Same tendency as for SM, but significant only for MOPP+EF | Increased risk only for MOPP+EF (RR 16.55, P = .004) | No difference in treatment |

| Dores 2002 | 16 US and European cancer registries; 1935‐1995; N = 32 591 | 2 153 SMN; 1 726 ST, 169 ANLL, 162 NHL | RT versus CT versus CRT (primary treatment) | No direct comparison between treatment groups: all results as RR according to primary treatment compared with normal population. | Significantly higher RR with CRT (95% CI 2.6‐3.6) compared with either RT alone (2.1‐2.4) or CT alone (1.5‐1.9). Digestic tract and female breast: Significantly higher risks with RT than without RT. | |||

| Foss‐Abrahamsen 1993 | 1 centre (Oslo); 1968‐1985; MFU = 8 yrs.; N = 1 152 | 68 SMN (+6 excluded non‐melanoma skin cancers); 9 AML, 8 NHL, 51 ST | RT, CT, CT+RT (total treatment) | Cox regression | Greater risk of SM for pts. who received both CT and RT | |||

| Koshy 2012 | SEER registry database; 1988.2006; N = 12 247 | ca. 650 SMN (5.3%) | RT versus no RT (primary treatment) | Kaplan‐Meier; no explicit comparison | no increase due to RT | |||

| Mauch 1996 | 1 centre (JCRT Boston, USA); 1969‐1988; N = 794 | 72 SMN; 53 ST, 8 AML, 10 NHL | RT(no relapse), RT‐relapse‐CT, CRT; total treatment | RRs compared with normal population, no direct treatment comparisons | RT alone RR 4.1, RT+CT RR 9.75, P < 0.05 | Same effect as with all SMN | Same effect as with all SMN | |

| Ng 2002 | 4 centres (all affil. to Harvard); 1969‐1997; MFU = 12 yrs.; N = 1319 (mainly early stages); (996 pts. with fu > 10 years were included in analysis of treatment effect) | 181 SMN (N = 162 for pts. with fu > 10 yrs.); 131 ST, 23 AML, 24 NHL | RT, CRT (total treatment); also separate analyses of non‐relapsed cases and relapsed cases | RRs calculated relative to normal population (age/sex‐specific); CI from Poisson distribution | RR higher with CRT than RT alone (6.1 versus 4.0, P = 0.015); (non‐relapsed cases only: 5.9 versus 3.7, P = 0.016). Analysed by radiation field size, this effect was only significant for TNI (±CT). RR higher with CT+TNI than for CT+Mantle/EF | |||

| Rodriguez 1993 | 1 centre (M.D. Anderson, Houston, USA); 1966‐1987; N = 1 013 | 66 SMN (first FU‐year excluded); 38 ST, 14 AML/MDS, 14 NHL | IF versus EF (+MOPP); CT versus CRT; RT versus CRT. Total therapy | Cox regression | RT versus CRT: no difference (P = 0.37). CT versus CRT: less SM with CRT (P = 0.001). But less courses of CT with CRT than with CT only! | |||

| Scholz 2011 | Multi‐centre (mainly Germany); 1978‐1998); N = 5 357 |

67 AML, 97 NHL | Primary: RT, conventional CT for intermediate stage, conventional CT for advanced stage, escalated BEACOPP | Parametric model; separate effects of primary and salvage treatment | Higher risk with escalated BEACOPP than conventional CT | No differences | ||

| Swerdlow 1992 | > 60 BNLI centres, UK; 1970‐1987; N = 2 846 |

113 SMN; 80 ST, 16 AML, 17 NHL | Alkyl. CT, Alkyl. CT +RT, IF‐RT (+/‐ nonalk. CT), EF‐RT (+/‐ nonalk. CT) (total treatment) | Poisson regression | No difference overall (nor for lung ca. alone) | More with CT or CRT (similar) than with RT | No differences | |

| Swerdlow 2000 | BNLI, Royal Marsden, St. Bartholomews; 1963‐1993; N = 5 519 | 322 SMN; 228 ST, 44 AML, 50 NHL | CT, RT, CRT (total treatment) | Poisson regression. RR compared with normal population, no direct treatment comparisons | Higher RR for CRT (SIR 3.9, 95% CI 3.2 ‐ 4.6) than for CT (SIR 2.6, 95% CI 2.1 ‐ 3.2) or RT (SIR 2.3, 95% CI 1.9 ‐ 2.8). | Higher risk for CRT (SIR 38.1, 95% CI 24.6‐55.9) or CT (SIR 31.6, 95% CI 19.7‐47.6) than for RT (SIR 1.2, 95% CI 0.1‐5.2) | No significant differences | |

| Swerdlow 2011 | UK, 1963‐2001 |

459 SMN; 302 ST, 75 AML, 82 NHL | CT, CRT | Higher risk for CRT than for CT alone | ||||

| Tucker 1988 | Stanford UMC; 1968 ‐ ?(year needed); N = 1 507 | 83 SMN (first FU‐year excluded); 46 ST, 28 AML, 9 NHL | RT, RT+adj. CT, RT+salvage CT, RT+intravenous‐gold, CT (total treatment) | Kaplan‐Meier, Gehan test | No differences (except: more with radiotherapy + intravenous‐gold) | Higher risk with CT than RT | No differences | |

| van Leeuwen 1994a | 2 centres (the Netherlands); 1966‐1986; MFU = 9 yrs.; N = 1 939 |

146 SMN; 93 ST, 31 AML, 23 NHL | CT, RT, CRT (total treatment) | (A) Person‐years analysis. (B) Cox regression | B: for lung cancer only: trend to more for RT (P = 0.08) or CRT (P = 0.07) than for CT. Otherwise no differences | A: AML not increased for RT; large increase for CT (CT similar to CRT). B: AML more for CT (P = 0.009) or CRT (P = 0.04) than for RT | B: trend to more for CRT than for either CT or RT (P = 0.06) |

AML = acute myeloid leukaemia; ANLL = acute nonlymphocytic leukemia; CT = chemotherapy; CRT = chemotherapy plus radiotherapy combined; NHL = non‐Hodgkin lymphoma; FU = follow‐up; HD = Hodgkins disease; MFU = median follow‐up

2. Previous investigations of secondary malignant neoplasms: solid tumours and NHL.

| Publication | Characteristics | Number of solid tumours / NHL | Treatment groups | Analysis methods | Conclusions (solid tumours) | Conclusions (NHL) |

| Behringer 2004 | Multi‐centre (mainly Germany); 1983‐98; N = 5 367 | 127 | CT, RT, CT+EF, CT+IF/local | RR compared with general population. No direct treatment comparisons. | ||

| Birdwell 1997 | Stanford UMC (USA); 1961‐1994; MFU = 10.9 yrs.; N = 2 441 | 25 gastrointestinal cancers | RT, CRT (total treatment) | RR compared with general population. No direct treatment comparisons. | Risk of gastrointestinal cancer not significantly greater with CRT (RR 3.9, 95% CI 2.2 to 5.6) than with RT (RR 2.0, CI 1.0 to 3.4) | |

| De Bruin 2009 | 5 centres (the Netherlands); 1965‐1995; N = 1 122 | 120 breast cancers | RT field and CT regimen in women under 41 years with supradiaphragmatic irradiation (N = 782) | Cox regression | Significantly greater risk of breast cancer with mantle RT than mediastinal RT | |

| Enrici 1998 | Rome, Italy; 1972‐1996; MFU = 84 months; N = 391 | 20 NHL |

(A) RT, CT, CRT (initial treatment) censored at relapse. (B) RT, CT, CRT (total treatment) |

Kaplan‐Meier and Cox regression | No difference between treatment modalities | |

| Foss‐Abrahamsen 2002 | 1 centre (Oslo); 1968‐1985; MFU = 14 yrs.; N = 1 024 | 26 lung, 23 breast, 31 NHL | RT, CT, CRT (total treatment) | RR compared with general population. No direct treatment comparison | Tendency to greater lung and breast cancer risk with RT or CRT versus CT | No difference between treatment modalities |

| Hancock 1993 | Stanford UMC (USA); 1961‐1990; MFU = 10 yrs.; N = 885 |

25 breast cancers | RT, CRT (total treatment) | RR compared with general population. No direct treatment comparisons | RT versus CRT: Tendency of more breast cancers with CRT, but not significant. RT: RR 3.5 (95% CI 1.9‐5.8), CRT: RR 5.7 (95% CI 3.1‐9.5) | |

| Hodgson 2007 | 13 cancer registries; 1970‐2001, 5‐year survivors; N = 18 862 | 1 490 ST | RT, CT, CRT (primary treatment, RT supra‐ or infradiaphragmatic according to SMN site) | RR by Poisson regression | significantly greater risk of breast cancer and other supradiaphragmatic cancer with RT or CRT versus CT | |

| Kaldor 1992 | Case‐control study; 12 cancer registries (Europe, Canada), 6 large hospitals (Europe); from 1960 onwards; N = 25 665 | 98 lung cancers | RT, CT, CRT | Standard case‐control study methods. RR compared with RT | Higher risk with CT, risk increase with number of CT cycles and RT dose to the lung. | |

| Meattini 2010 | One centre (Florence, Italy); 1060‐2003; N = 1 538 | 39 breast cancers | RT, CT, CRT (primary treatment); RT field; CT regimen | Cox regression | No significant differences (breast) | |

| Swerdlow 2001 | Nested case‐control study; multi‐centre (Britain); 1963‐1995; N = 5 519 | 88 lung cancers | RT, CT, CRT (total treatment) | Conditional logistic regression | No significant differences in lung cancer risk between RT, CT, CRT. (exception: adenocarcinomas ‐ greater risk with CT than without.) Risk greater with MOPP than without MOPP | |

| Swerdlow 2012 | UK, 1956 ‐ 2003 | 373 breast cancers | RT, CRT | Breast cancer standardised incidence ratio (SIR) is highest among patients receiving RT at a young age | ||

| Travis 2002 | Embedded case‐control study; 7 cancer registries; 1965‐1994; N = 19 046 |

222 lung cancers | RT, alkylating CT, RT with alk. CT, RT + salvage alk. CT, neither (total treatment) | Conditional logistic regression | Lung cancer risk increases with RT dose to the lung and with use of alkylating agents | |

| Travis 2003 | Embedded case‐control study; 6 cancer registries; 1965‐1994; N = 3 817 women |

105 breast cancers | RT, alkylating CT, RT with alk. CT, RT + salvage alk. CT, neither (total treatment) | Conditional logistic regression | Breast cancer risk increases with RT dose to breast and decreases with use of alkylating CT and with radiation of ovaries | |

| van Leeuwen 1995 | Embedded case‐control study; 2 centres (the Netherlands); 1966‐1986; N = 1 939 |

30 lung cancers | RT, CT, CRT. RT dose to lung (total treatment) | Conditional logistic regression | Risk of lung cancer tended to increase with increasing RT dose (P = 0.01); RR(> 9 Gy versus 0) = 9.6. No significant differences between RT, CT, CRT | |

| van Leeuwen 2003 | Embedded case‐control study; 4 centres (the Netherlands); 1965‐88; N = 2 637 |

48 breast cancers | RT, CRT. RT dose to breast, ovary. CT cycles, dose of alkylating agents | Conditional logistic regression | Breast cancer risk increases with RT dose and decreases with modality CRT; no CT dose effect |

CT = chemotherapy; CRT = chemotherapy plus radiotherapy combined; NHL = non‐Hodgkin lymphoma; FU = follow‐up; HD = Hodgkins disease; MFU = median follow‐up

3. Previous investigations of secondary malignant neoplasms: AML or MDS.

| Publication | Characteristics | Number of AML/MDS | Treatment groups | Analysis methods | Conclusions (AML/MDS) |

| Brusamolino 1998 | 2 centres (Italy); 1975‐1992; MFU = 10 yrs.; N = 1 659 | 36 AML/MDS | RT, CT, CT+RT. Total treatment | A.Log‐rank tests (univariate) to compare treatment groups B.Embedded case‐control study with conditional logistic regression analysis. | A. Higher risk after CT than RT (P = 0.04); higher risk with CT than with CRT (P = 0.05); higher risk with MOPP+RT than with MOPP/ABVD or with ABVD+RT (P = 0.002); higher risk with EF + MOPP than with IF+MOPP (P = 0.01) B. higher risk after CT than RT (OR 4.1; P = 0.05); higher risk after CRT than RT (OR 6.4; P = 0.02); higher risk after MOPP+RT than ABVD+RT (OR 5.9; P = 0.001) or MOPP/ABVD |

| Eichenauer 2014 | GHSG HD7‐HD15, PROFE, BEACOPP‐14 (1993‐2009); MFU: 72 months, N = 11 952 | 106 AML/MDS | RT, CT, CRT | Significantly higher risk after 4 or more cycles of escalated BEACOPP | |

| Josting 2003 | Multi‐centre (GHSG (Germany) HD1‐HD9); 1981‐1998; MFU = 55 months; N = 5 411 | 46 AML/MDS | CT, RT, CRT, HDCT with SCT. Primary treatment, not censored at relapse | Kaplan‐Meier. No direct treatment comparison | No significant differences between treatment protocols |

| Kaldor 1990 | Case‐control study; 12 cancer registries (Europe, Canada), 6 large hospitals (Europe); 1960‐?(year needed); N = 29 552 | 149 AML/MDS (at least one year after HD diagnosis) | RT, CT, CRT. Total treatment | Standard case‐control study methods. RR compared with RT | Higher risk with CT than with RT (RR 9.0; CI 4.1‐20); higher risk with CRT than with RT (RR 7.7; CI 3.9‐15). No difference in CT versus CRT; but there was a dose‐related increase in the risk in pts. who received RT alone |

| Koontz 2013 | Stanford (1974‐2003); N = 754 | 24 AML/MDS | RT, CT, CRT | Increased risk with higher doses of alkylating agents | |

| Pedersen‐Bjergaard 1987 | 1 centre (Copenhagen); 1970‐1981; N = 391 | 20 ANLL/preleukaemia | Low, intermediate, or high dose of alkylating agents. Total treatment | Cox regression | Risk increases with increasing (total) log dose of alkylating agents (P = 0.0024, regr. coefft. = 0.69) |

| van Leeuwen 1994b | Embedded case‐control study; 2 centres (Netherlands); 1966‐1986; N = 1 939 | 44 Leukemias (incl. 32 ANLL, 12 MDS) | RT, CT, RT+CT. Total treatment | Conditional logistic regression | More risk with CT than with RT alone; <= 6 cycles: P = 0.08, RR = 8.5; > 6 cycles: P < 0.001, RR = 44 |

AML = acute myeloid leukaemia; ANLL = acute nonlymphocytic leukemia; CT = chemotherapy; CRT = chemotherapy plus radiotherapy combined; NHL = non‐Hodgkin lymphoma; FU = follow‐up; HD = Hodgkins disease; MFU = median follow‐up

The above‐mentioned studies make non‐randomised comparisons of secondary malignant neoplasm rates between treatments since even if randomised trial data were included, the data from several trials and from non‐randomised cases were pooled. Therefore, the benefits of randomisation do not necessarily apply to the treatment comparisons made in these studies. The patients receiving different treatment modalities may be non‐comparable with respect to several known or unknown factors, which may be related to secondary malignant neoplasm risk. In short, these comparisons may be 'confounded'.

One literature‐based and two individual‐patient‐data meta‐analyses comparing the effectiveness of different treatment modalities in HL have already been published by others (Shore 1990; Loeffler 1998; Specht 1998). The results demonstrate that the use of combined modality therapy improves disease‐free survival, compared with chemotherapy alone (advanced stages) or radiotherapy alone (early stages), but the 10‐year overall survival (OS) rates were not significantly improved. Additional radiation was in fact associated with a slightly lower OS compared with the use of further chemotherapy in advanced disease. Similarly, more extensive radiotherapy improved disease‐free survival but not OS when compared with limited irradiation. Loeffler 1998 analysed leukaemia‐related deaths but the survival estimates were limited to 10 years after HL diagnosis, too early for the effect of solid tumours to be felt. Specht 1998 analysed secondary malignant neoplasm‐related deaths for patients without recurrence of HL.

The only meta‐analysis of the first occurrence of secondary malignant neoplasms after HL was performed by our group from 2000 to 2004 (Franklin 2005; Franklin 2006a) as a Cochrane systematic review using individual patient data (IPD) from randomised trials comparing chemotherapy alone, radiotherapy alone and combined chemo‐radiotherapy, and comparing extended‐field with involved‐field radiotherapy. This review largely confirmed the results of previous meta‐analyses concerning overall and progression‐free survival (PFS). Concerning secondary malignant neoplasms, the use of a combined modality, particularly in early‐stage disease, was shown to reduce secondary malignant neoplasm risk compared with radiotherapy alone. This is possibly due to the greatly improved HL tumour control and consequent reduced need for intensive salvage treatment. In contrast, eliminating additional radiotherapy, particularly in advanced‐stage patients, slightly reduced the risk of secondary malignant neoplasms. No significant reduction in secondary malignant neoplasm risk from the use of involved field (instead of extended field) could be demonstrated, although the risk of secondary breast cancer was significantly reduced. The reliability and current relevance of the results were limited due to the considerable number of trials for which no data were obtained, the inclusion of older trials with outdated treatments and the uncertain quality of secondary malignant neoplasm data.

In order to clarify the relationship between treatment modality and secondary malignant neoplasm risk, long‐term follow‐up data from large numbers of patients are required since only a small percentage will incur a secondary malignant neoplasm within a given time interval. Further, specific sites of solid tumours may have to be analysed separately, resulting in even smaller incidences. Due to the many confounding factors (age, sex, smoking habits, etc.) conclusions should be based on randomised comparisons between treatment modalities, in contrast to pooled data analyses. All these factors argue for a systematic overview of the risk of secondary malignant neoplasms. The present review aims to tailor our previous review to questions of current relevance, modern treatments and high‐quality trials.

A review of this type compares treatment 'policies', that is the choice of first‐line treatment modality, rather than the influence of radiation and drugs on a biologic level. Not only these two influences, but also accompanying diagnostic procedures, supporting medication, second‐line treatment if necessary and treatment for other late effects, may contribute to the overall secondary malignant neoplasm risk associated with a treatment policy. Conclusions concerning the biologic influence of radiation and drugs per se must remain tentative.

Due to the influence of personal factors on secondary malignant neoplasm risk, the many types of secondary malignant neoplasms and the time‐to‐event nature of the data, a meta‐analysis based on IPD makes the best possible use of the information available. We collected data on all three classes of secondary malignant neoplasms as well as on efficacy (overall and PFS). We compared the effect of treatment modality on the risk of secondary malignant neoplasms as a whole as well as AML, NHL and solid tumours, and overall and disease‐free survival. The comparison of effectiveness both updates and extends the previous IPD meta‐analyses mentioned above. Furthermore, information on effectiveness is needed to put the results concerning secondary malignant neoplasm risk into context, since all outcomes must be considered together in choosing the optimal treatment modality.

Objectives

We aimed to answer several questions concerning possible changes in the risk to develop secondary malignancies when modifying chemotherapy or radiotherapy (omission of radiotherapy, reduction of the radiation field, reduction of the radiation dose, use of fewer chemotherapy cycles, intensification of chemotherapy). In addition, we analysed whether these modifications affect the Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) clinical outcome, i.e. progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered only randomised controlled trials that enrolled at least 50 patients per arm and completed recruitment by 2007 (as observation times would otherwise be too short to permit secondary malignant neoplasms to be observed). Smaller studies contribute little evidence, especially concerning secondary malignant neoplasms, and are prone to early termination bias or publication bias.

Types of participants

We included trials with adult or paediatric patients treated for newly diagnosed HL.

Types of interventions

We considered trials making the following randomised treatment comparisons to be eligible.

-

Avoidance of radiotherapy:

chemotherapy alone versus same chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

-

Smaller radiation field:

chemotherapy plus involved‐field radiation versus same chemotherapy plus extended‐field radiation.

-

Lower‐dose radiation:

chemotherapy plus lower‐dose radiation versus same chemotherapy plus higher‐dose radiation.

-

Fewer chemotherapy courses:

fewer versus more courses of chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy in each case).

-

Intensified chemotherapy:

dose‐intensified chemotherapy versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD)‐like chemotherapy (see below) (with or without radiotherapy in each case).

'Same' chemotherapy means the same regimen including drug doses and number of cycles (see, however, remark below concerning confounding).

We restricted 'Radiotherapy' to modern high‐energy irradiation to the involved field or less, except for the comparison between involved‐field and extended‐field irradiation. 'Extended field' includes also the more extensive subtotal and total nodal irradiation categories (STNI and TNI). We restricted 'Chemotherapy' to regimens similar to ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) (that is, at least three of these four drugs and at most two additional drugs; or four drugs of which at most two of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine are substituted by closely related compounds; or an alternating or hybrid regimen including such an ABVD‐like component), except for the dose‐intensified regimens. Examples of such similar regimens are ABVPP (with procarbazine and prednisone), EBVD (with epirubicin), MOPP/ABV (with mustargen, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone) or COPP/ABVD (with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone).

We specified the precise definitions of reduced and standard radiation dose, reduced and standard number of chemotherapy cycles, dose‐intensified and standard chemotherapy by considering the designs of potentially eligible trials (without knowledge of outcomes).

Ideally, the treatment arms should differ only with respect to the aspect being compared. For instance, in comparing chemotherapy alone with combined chemotherapy plus radiotherapy the chemotherapy should be identical in each arm. However, restricting the review to such 'unconfounded' trials might mean that not enough data could be obtained for reliable results. Data from 'confounded' trials, allowing minor differences in the modality common to both arms, were also included if this inclusion increased either the number of patients or the number of trials by at least 50%. 'Minor difference' is taken to mean up to two chemotherapy cycles more or less, one additional or different drug, or a different radiation dose. For instance, certain trials compare eight cycles of chemotherapy alone with six cycles of the same regimen plus radiation. The conclusions then apply to the 'mixture' of treatment comparisons analysed, for example, the elimination of additional radiotherapy accompanied in some cases by an increased volume of chemotherapy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary endpoint is the time to occurrence of a secondary malignant neoplasm (secondary malignant neoplasm‐free survival). This is an adverse event.

Secondary outcomes

Time to death of any cause (overall survival (OS)).

Time to HL progression, relapse or death of any cause (progression‐free survival (PFS)).

We analysed the primary endpoint separately for each of the three classes of secondary malignancy (solid tumours, NHL and AML), censoring occurrence of the other two classes respectively. We analysed solid tumours separately for the most frequent sites (expected to include lung, female breast and colon cancers). We repeated analyses with censoring at Hodgkin progression or relapse in order to exclude the effects of second‐line therapy.

Search methods for identification of studies

According to Chapter seven of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011)

Electronic searches

Electronic literature databases (initially searched in June 2010 and again in March 2015 and July 2017):

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, latest issue);

MEDLINE;

Trials registers: ClinicalTrials.gov; WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP); www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct.

We retrieved only reports published in 1984 or later (first identified randomised trial with ABVD).

CENTRAL includes all annual meetings of the American Society of Hematology up to 2013, the American Society of Clinical Oncology up to 2014, the European Hematology Association up to 2012 and the European Society of Medical Oncology up to 2010 and the International Symposium on Hodgkin Lymphoma up to 2010 (all inclusive).

We performed searches using algorithms developed by the Information Specialist of the Cochrane Haematological Malignancies Group (CHMG), based on the then current algorithms used by Cochrane (see Appendix 1; Appendix 2).

The same search was repeated in March 2015 without collecting further IPD (one further eligible study was identified) and again in July 2017 (no further eligible studies).

Searching other resources

The following searches were performed.

Proceedings of the International Symposium on Hodgkin Lymphoma 2013 and European Hematology Association 2014 (not yet included in CENTRAL).

Reference lists of all relevant retrieved publications.

Contact with co‐operative trial groups working on HL, identified through personal contacts and identified publications.

Previous meta‐analyses in HL.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

As suggested in Chapter seven of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, two review authors (DAE, JF) listed the retrieved publications (Higgins 2011). The full text of all potentially relevant publications that were short‐listed by at least one review author were retrieved and assessed independently by both authors. We compared the two resulting lists of relevant studies and reached a consensus. We displayed a flow diagram as proposed in the PRISMA statement (Moher 2009) to describe the results of the search and selection process.

Data extraction and management

According to Chapter seven of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we requested pseudonymised IPD from each trial identified as meeting the inclusion criteria, including data on year of birth, sex, date of (first) Hodgkin diagnosis, stage of disease, presence or absence of systemic (B) symptoms, treatment arm by randomisation, date of randomisation, remission status at end of first‐line treatment (with date), occurrence and date of relapse, occurrence, date and type of secondary malignant neoplasms, whether secondary malignant neoplasms occurred in the radiation field (if applicable), occurrence and date of death and date of last follow‐up information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

As suggested in Chapter eight of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we checked IPD for completeness and consistency. As a preparatory step, we analysed each trial separately, comparing the treatment arms with respect to recruitment times, patient characteristics, complete remission rate, length of follow‐up, PFS, OS and occurrence of secondary malignant neoplasms. This step investigates the comparability of the treatment arms and the consistency of the data with previous publications of the trial.

We assessed each trial according to the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. Since this was an IPD analysis and all our targeted outcomes could be obtained from all included trials, selective reporting bias did nor occur. Further, the following special aspects were assessed.

Reliability of secondary malignant neoplasm follow‐up methods: we assessed the method of follow‐up as described by the trialists for likely completeness and accuracy.

Completeness of follow‐up: we calculated the median follow‐up time, using the Kaplan‐Meier method, to indicate average length of follow‐up. We quantified the distribution of last information dates. Both high variability (large interquartile range), in relation to the median follow‐up time, and significant differences between treatment arms indicate less reliable follow‐up. We also compared completeness of follow‐up between patients with and without secondary malignant neoplasms.

We compared the secondary malignant neoplasm rate with that expected in an age‐ and sex‐matched cohort from the general population, using data from various US, European and Australasian cancer registries as appropriate to the trial.

These special aspects were expected to be the most problematic since secondary malignant neoplasm events were not a major endpoint for most trials.

Risk of bias was considered when interpreting review results by qualitative and quantitative description as well as by a sensitivity analysis excluding incomplete follow‐up periods.

Measures of treatment effect

According to Chapter nine of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we calculated a measure (Peto's odds ratio (OR)) of the difference in cumulative secondary malignant neoplasm incidence between the treatment arms of each trial separately, together with an estimate of the variance of this quantity (EBCTCG 1988; EBCTCG 1992). For PFS and OS, we calculated the hazard ratio (HR) using Cox proportional hazards regression (the proportional hazards assumption was checked graphically and no relevant deviations were found).

Both the first‐line treatment and possible salvage therapy for progression or relapse of HL may contribute to secondary malignant neoplasm risk. The type and frequency of salvage therapy, and thus its effect on secondary malignant neoplasm risk, depend on both the nature and efficacy of the first‐line treatment. Therefore, we conducted separate analyses with and without the effect of salvage therapy. For the latter, follow‐up times are censored at HL progression or relapse and subsequent secondary malignant neoplasms do not count as events.

We intended to analyse solid tumours separately for the most common sites (lung and breast), but omitted this due to the small numbers of events.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

We included some studies with a factorial design, for instance in GHSG HD10, participants were randomised between two and four cycles of chemotherapy and simultaneously between involved field radiotherapy at 20Gy and 30Gy doses. This study was thus included in meta‐analyses of two treatment comparisons: fewer chemotherapy cycles and reduced‐dose radiation, in each case pooling participants over pairs of treatment groups. In other studies, data of a treatment group not fitting the inclusion criteria (e.g. the standard‐dose BEACOPP arm of GHSG HD9) was simply omitted from the analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We queried all missing values in IPD data sets with the trialists. If missing values of key variables (randomisation arm, outcome) persisted, we excluded the case concerned from the analysis. We report the numbers of such exclusions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We described the heterogeneity of treatment effects between trials using the I2 statistic. For descriptive purposes, we adopted the classification of amount of heterogeneity suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011 section 9.5.2). For the purpose of assessing quality of evidence in the 'Summary of findings' tables, 50% was used as an approximate limit for downgrading due to high heterogeneity. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for I2 using the test‐based method described by Higgins and Thompson (Higgins 2002).

Assessment of reporting biases

If at least 10 studies were included in a particular comparison, we planned to use a funnel plot and a linear regression test for asymmetry (test of slope for regression of treatment effect size on the total number of participants in the trial) to assess whether the included trials were a biased sample of all eligible trials in terms of estimated treatment effect. This was not performed since no study question included more than seven trials.

Data synthesis

We combined the following randomised comparisons across the appropriate trials.

Chemotherapy alone versus same chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

Chemotherapy plus involved‐field radiation versus same chemotherapy plus extended‐field radiation.

Chemotherapy plus lower‐dose radiation versus same chemotherapy plus higher‐dose radiation.

Fewer versus more courses of chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy in each case).

Dose‐intensified chemotherapy versus ABVD‐like chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy in each case).

In general, all comparisons were performed separately for early‐stage HL (stages I to II) and advanced‐stage HL (stages III to IV).

We combined measures of treatment effect across trials that are relevant to the comparison being made in order to assess overall differences in secondary malignant neoplasm rate (or other outcome) between modalities. We thus used a two‐step approach (i.e. first, analysis of each trial separately and second, meta‐analysis combination of estimates) based on the fixed‐effect model. Relative risks refer to randomised comparisons between treatment modalities. We calculated risks relative to the general population only for the purpose of assessing data quality. We performed analyses within trials in SAS and entered the relevant results into Review Manager (RevMan 2012).

Due to the multiplicity of endpoints and to the several subgroup analyses proposed, the danger of significant differences arising by chance alone is increased. For this reason, we employed 99% CIs for individual trials but show 95% CIs for aggregated estimates (for example, as in EBCTCG 1992).

Grading of evidence

For 'Summary of findings' tables, we assessed the quality of evidence for each study question and outcome according to the methods of the GRADE Working Group (Guyatt 2008). The following factors were considered to lower the grade of evidence by one point: high heterogeneity, low number of events, poor consistency between groups of studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analyses to investigate whether certain types of patients or treatment types show different treatment effects. We employed the following patient‐related subgroups:

age (under 50 years; 50 years and older); and

sex.

Treatment‐related subgroups were considered for SQ5 (dose‐intensified versus ABVD‐like chemotherapy) only, grouping according to the intensified regimen (BEACOPP, Stanford V, EBVCAD, ChlVPP).

Firstly, the presence of an interaction between the relevant treatment factor (according to study question) and the subgrouping factor was tested in order to decide wether the treatment effect differed between subgroups. Treatment effects within subgroups were taken seriously only where the interaction was significant (P ≤ 0.05).

In addition, signs of a time trend according to median year of recruitment were investigated graphically.

Sensitivity analysis

As a sensitivity analysis for the outcome secondary malignant neoplasms, we analysed the data for all trials making a particular comparison of modalities together, by Cox proportional hazards regression (Cox 1972), including relevant covariates (age, sex, stage). In order to preserve the advantages of randomised comparisons in the presence of inter‐trial heterogeneity of baseline risk, we stratified analyses by trial (a one‐step approach).

We performed further sensitivity analyses to check that the results were not crucially dependent on selection criteria or analysis methods. Firstly, we repeated analyses with the exclusion of the latest, less complete follow‐up periods in each trial (that is when less than 75% of patients were still followed up). Secondly, we reran analyses excluding confounded trials. Thirdly, we repeated secondary malignant neoplasms and solid tumour analyses excluding non‐melanoma skin cancers (as in many previous investigations of secondary malignant neoplasms).

Fourthly, the Peto and the Cox methods do not allow for competing risks (deaths from other causes compete with second malignancies). The Cox regression method is valid for comparing 'cause‐specific' hazards in the presence of competing risks (Iacobelli 2013). In order to display cumulative incidence curves for the compared treatment options, we employed the cumulative incidence method (Pepe 1993; Tai 2001), which allows for competing risks, for the pooled data set (not meta‐analytically as proposed in Franklin 2006b). This analysis was not stratified by study.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We screened the MEDLINE and Cochrane Central databases for clinical trials eligible for this meta‐analysis on secondary malignancies after Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) treatment. In June 2010, a total of 3515 references published after 1984 were identified and independently reviewed with respect to their eligibility by two of the review authors (DAE and JF). The majority did not meet the predefined criteria and were excluded.

Five hundred and seventy‐eight references fulfilled the predefined general eligibility criteria and were re‐assessed concerning the exact treatment comparison. Twenty randomised clinical trials (RCTs) for the first‐line treatment of HL including at least 50 patients per study arm and comparing treatment modalities as listed above (see Types of interventions) were identified. We contacted the relevant authors and study groups and requested individual patient data IPD). Finally, data were received for 16 trials; no data were received from four trials.

The same search strategy was repeated in March 2015 to check for eligible studies published since the original search. A total of 953 non‐duplicate references were identified and again, independently evaluated by DAE and JF. There were 61 articles evaluated as fulfilling the general requirements (RCTs comparing first‐line therapies of HL patients). The majority described previously identified trials; 14 trials were new, of which two turned out to be not randomised. Of the remaining 12 trials, 11 were excluded due to < 50 patients per arm, recruitment beyond 2007 or inappropriate comparison of therapies. One study, the American Intergroup Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG_E2496) comparing ABVD with Stanford V in locally extensive and advanced‐stage HL, was identified as eligible. Reasons for failing general eligibility criteria: 1926 references did not concern HL patients, 1311 did not report a clinical therapy trial, 212 reported on second‐line therapy, 125 reported non‐randomised trials and 255 were review articles.

The three international trials registries listed in Electronic searches were searched online after completion of the data analysis to check for missed studies: no further eligible trials were found.

The same search was repeated in July 2017: 1046 distinct articles were retrieved. Five hundred and forty‐three references did not concern HL, 156 did not report a clinical therapy trial, 135 described second‐line therapy, 109 were review articles and 19 reported not randomised trials. Eighty‐four articles were identified as describing potentially eligible studies. Of those studies not already included, none were eligible according to the full inclusion criteria.

Figure 1 displays the results of the original 2010 search and the repeated 2015 and 2017 searches together, with reasons for failing general eligibility criteria.

1.

Search results and inclusion of studies (IPD = individual patient data). Numbers are cumulative over the original (2010) and repeat (2015 and 2017) searches.

Included studies

The studies included in the present meta‐analysis had randomly compared one or more of the following treatment strategies with at least 50 patients per study arm (summary of amount of data in Figure 2).

2.

Numbers of trials and patients analysed for each study question

SQ1: Chemotherapy alone versus same chemotherapy plus radiotherapy

SQ2: Chemotherapy plus involved‐field radiation versus same chemotherapy plus extended‐field radiation

SQ3: Chemotherapy plus lower‐dose radiation versus same chemotherapy plus higher‐dose radiation

SQ4: Fewer versus more courses of chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy in each case)

SQ5: Dose‐intensified versus ABVD‐like chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy in each case)

SQ1

In the following studies, patients were randomly assigned to no adjuvant radiotherapy or adjuvant radiotherapy

1) In the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 20884 trial for patients with advanced HL (according to the EORTC definition), recruitment between 1989 and 2000, patients received either involved‐field (IF)‐RT (24 Gy to 40 Gy) or no radiotherapy after chemotherapy with six or eight cycles of MOPP/ABV (EORTC #20884). The amount of chemotherapy depended on the initial response to treatment as judged by interim staging.

2) In the EORTC‐GELA (Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes Adulte) H9‐F trial for patients with early favourable HL (according to the EORTC‐GELA definition), recruitment between 1998 and 2004, patients received either IF‐RT (20 Gy or 36 Gy) or no radiotherapy after six cycles of EBVP chemotherapy (EORTC H9‐F).

3) In the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) HD3 trial for patients with advanced HL (according to the GHSG definition), recruitment between 1984 and 1988, patients received either 20 Gy IF‐RT or no radiotherapy after three double cycles of COPP/ABVD chemotherapy. Patients who did not receive radiotherapy had one additional double cycle of COPP/ABVD chemotherapy (GHSG HD3).

A total of 1011 patients were considered for the comparison between no additional radiotherapy and additional radiotherapy after chemotherapy (340 versus 671). Three hundred and thirty‐three patients came from the EORTC 200884 trial, 578 patients came from the H9‐F trial and 100 patients came from the HD3 trial.

SQ2

In the following studies, patients were randomly assigned to less or more extended‐radiotherapy fields

1) Within the EORTC‐GELA H8‐U trial for patients with early unfavourable HL (according to the EORTC‐GELA definition), recruitment between 1993 and 1999, patients received either IF‐RT or subtotal nodal irradiation category (STNI) after chemotherapy consisting of four or six cycles of MOPP/ABV (EORTC H8‐U).

2) Within the GHSG HD8 trial for patients with early unfavourable HL (according to the GHSG definition), recruitment between 1993 and 1998, patients received either IF‐RT or extended‐field (EF)‐RT after chemotherapy consisting of two double cycles of COPP/ABVD (GHSG HD8; Sasse 2012).

3) Within the Italian HD94 trial for patients with early unfavourable HL (as defined by study group conducting the trial), recruitment between 1994 and 1997, patients received either IF‐RT or EF‐RT after chemotherapy consisting of four cycles of ABVD (Roma_HD94).

4) Within the Milan Study for patients with early unfavourable HL (as defined by the study group conducting the trial), recruitment between 1990 and 1996, patients received either IF‐RT or STNI after chemotherapy consisting of four cycles of ABVD (Milano_STNI_IF).

A total of 2397 patients were considered for the comparison between less or more extended‐radiation fields (1371 versus 1026). 984, 1064, 209 and 140 came from the trials 1), 2), 3) and 4).

SQ3

In the following studies, patients were randomly assigned to a lower or higher radiation dose

1) In the EORTC‐GELA H9‐F trial for patients with early favourable HL (according to the EORTC‐GELA definition), recruitment between 1998 and 2004, patients received either 20 Gy IF‐RT or 36 Gy IF‐RT after six cycles of EBVP chemotherapy (EORTC H9‐F).

2) In the GHSG HD10 trial for patients with early favourable HL (according to the GHSG definition), recruitment between 1998 and 2003, patients received either 20 Gy IF‐RT or 30 Gy IF‐RT after two or four cycles of ABVD chemotherapy (2x2 design) (GHSG HD10).

3) In the GHSG HD11 trial for patients with early unfavourable HL (according to the GHSG definition), recruitment between 1998 and 2003, patients received either 20 Gy IF‐RT or 30 Gy IF‐RT after four cycles of ABVD or non‐escalated bleomycin, etoposide, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone (baseline BEACOPP) chemotherapy (2 x 2 design) (GHSG HD11).