Abstract

Background

Excessive alcohol use contributes significantly to physical and psychological illness, injury and death, and a wide array of social harm in all age groups. A proven strategy for reducing excessive alcohol consumption levels is to offer a brief conversation‐based intervention in primary care settings, but more recent technological innovations have enabled people to interact directly via computer, mobile device or smartphone with digital interventions designed to address problem alcohol consumption.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of digital interventions for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption, alcohol‐related problems, or both, in people living in the community, specifically: (i) Are digital interventions more effective and cost‐effective than no intervention (or minimal input) controls? (ii) Are digital interventions at least equally effective as face‐to‐face brief alcohol interventions? (iii) What are the effective component behaviour change techniques (BCTs) of such interventions and their mechanisms of action? (iv) What theories or models have been used in the development and/or evaluation of the intervention? Secondary objectives were (i) to assess whether outcomes differ between trials where the digital intervention targets participants attending health, social care, education or other community‐based settings and those where it is offered remotely via the internet or mobile phone platforms; (ii) to specify interventions according to their mode of delivery (e.g. functionality features) and assess the impact of mode of delivery on outcomes.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, HTA and Web of Knowledge databases; ClinicalTrials.com and WHO ICTRP trials registers and relevant websites to April 2017. We also checked the reference lists of included trials and relevant systematic reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the effectiveness of digital interventions compared with no intervention or with face‐to‐face interventions for reducing hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption in people living in the community and reported a measure of alcohol consumption.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

We included 57 studies which randomised a total of 34,390 participants. The main sources of bias were from attrition and participant blinding (36% and 21% of studies respectively, high risk of bias). Forty one studies (42 comparisons, 19,241 participants) provided data for the primary meta‐analysis, which demonstrated that participants using a digital intervention drank approximately 23 g alcohol weekly (95% CI 15 to 30) (about 3 UK units) less than participants who received no or minimal interventions at end of follow up (moderate‐quality evidence).

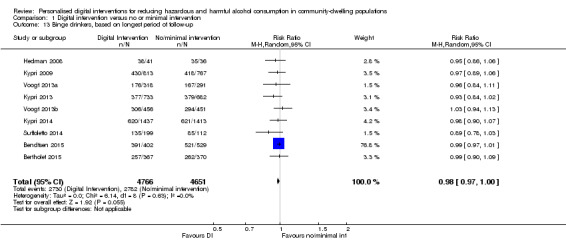

Fifteen studies (16 comparisons, 10,862 participants) demonstrated that participants who engaged with digital interventions had less than one drinking day per month fewer than no intervention controls (moderate‐quality evidence), 15 studies (3587 participants) showed about one binge drinking session less per month in the intervention group compared to no intervention controls (moderate‐quality evidence), and in 15 studies (9791 participants) intervention participants drank one unit per occasion less than no intervention control participants (moderate‐quality evidence).

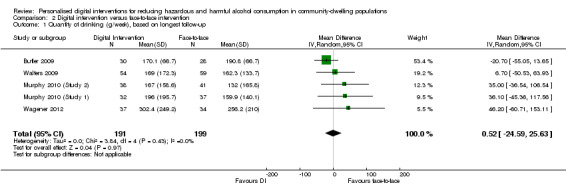

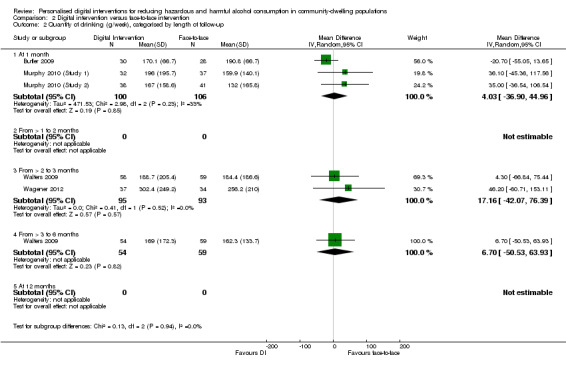

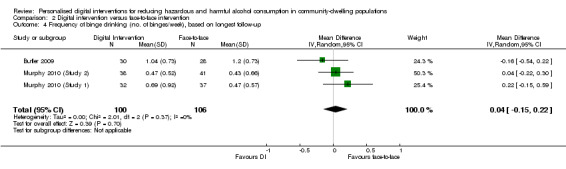

Only five small studies (390 participants) compared digital and face‐to‐face interventions. There was no difference in alcohol consumption at end of follow up (MD 0.52 g/week, 95% CI ‐24.59 to 25.63; low‐quality evidence). Thus, digital alcohol interventions produced broadly similar outcomes in these studies. No studies reported whether any adverse effects resulted from the interventions.

A median of nine BCTs were used in experimental arms (range = 1 to 22). 'B' is an estimate of effect (MD in quantity of drinking, expressed in g/week) per unit increase in the BCT, and is a way to report whether individual BCTs are linked to the effect of the intervention. The BCTs of goal setting (B ‐43.94, 95% CI ‐78.59 to ‐9.30), problem solving (B ‐48.03, 95% CI ‐77.79 to ‐18.27), information about antecedents (B ‐74.20, 95% CI ‐117.72 to ‐30.68), behaviour substitution (B ‐123.71, 95% CI ‐184.63 to ‐62.80) and credible source (B ‐39.89, 95% CI ‐72.66 to ‐7.11) were significantly associated with reduced alcohol consumption in unadjusted models. In a multivariable model that included BCTs with B > 23 in the unadjusted model, the BCTs of behaviour substitution (B ‐95.12, 95% CI ‐162.90 to ‐27.34), problem solving (B ‐45.92, 95% CI ‐90.97 to ‐0.87), and credible source (B ‐32.09, 95% CI ‐60.64 to ‐3.55) were associated with reduced alcohol consumption.

The most frequently mentioned theories or models in the included studies were Motivational Interviewing Theory (7/20), Transtheoretical Model (6/20) and Social Norms Theory (6/20). Over half of the interventions (n = 21, 51%) made no mention of theory. Only two studies used theory to select participants or tailor the intervention. There was no evidence of an association between reporting theory use and intervention effectiveness.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate‐quality evidence that digital interventions may lower alcohol consumption, with an average reduction of up to three (UK) standard drinks per week compared to control participants. Substantial heterogeneity and risk of performance and publication bias may mean the reduction was lower. Low‐quality evidence from fewer studies suggested there may be little or no difference in impact on alcohol consumption between digital and face‐to‐face interventions.

The BCTs of behaviour substitution, problem solving and credible source were associated with the effectiveness of digital interventions to reduce alcohol consumption and warrant further investigation in an experimental context.

Reporting of theory use was very limited and often unclear when present. Over half of the interventions made no reference to any theories. Limited reporting of theory use was unrelated to heterogeneity in intervention effectiveness.

Keywords: Humans; Cell Phone; Computers, Handheld; Minicomputers; Alcohol Drinking; Alcohol Drinking/epidemiology; Alcohol Drinking/therapy; Alcohol‐Related Disorders; Alcohol‐Related Disorders/epidemiology; Alcohol‐Related Disorders/therapy; Behavior Therapy; Behavior Therapy/methods; Binge Drinking; Binge Drinking/epidemiology; Binge Drinking/therapy; Cost‐Benefit Analysis; Motivational Interviewing; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Therapy, Computer‐Assisted; Therapy, Computer‐Assisted/methods

Plain language summary

Does personalised advice via computer or mobile devices reduce heavy drinking?

Review question

We aimed to find out if personalised advice to reduce heavy drinking provided using a computer or mobile device is better than nothing or printed information. We also compared advice provided using a computer or mobile device to advice given in a face‐to‐face conversation. The main outcome was how much alcohol people drank.

Background

Heavy drinking causes over 60 diseases, as well as many accidents, injuries and early deaths each year. Brief advice or counselling, delivered by doctors or nurses, can help people reduce their drinking by around 4 to 5 units a week. In the UK, this is around two pints (1.13 L) of beer or half a bottle of wine (375 mL) each week. However, people may be embarrassed by talking about alcohol.

Search date

Current to March 2017.

Study characteristics The studies included people in workplaces, colleges or health clinics and internet users. Everyone typed information about their drinking into a computer or mobile device ‐ which then gave half the people advice about how much they drank and the effect this has on health. This group also received suggestions about how to cut down on drinking. The other group could sometimes read general health information. Between one month and one year later, everyone was asked to confirm how much they were drinking. Drinking levels in both groups were compared to each other at these time points.

Study funding sources

Many (56%) studies were funded by government or research foundation funds. Some (11%) were funded by personal awards such as PhD fellowships. The rest did not report sources of funding.

Key results We included 57 studies comparing the drinking of people getting advice about alcohol from computers or mobile devices with those who did not after one to 12 months. Of these, 41 studies (42 comparisons, 19,241 participants) focused on the actual amounts that people reported drinking each week. Most people reported drinking less if they received advice about alcohol from a computer or mobile device compared to people who did not get this advice.

Evidence shows that the amount of alcohol people cut down may be about 1.5 pints (800 mL) of beer or a third of a bottle of wine (250 mL) each week. Other measures supported the effectiveness of digital alcohol interventions, although the size of the effect tended to be smaller than for overall alcohol consumption. Positive differences in measures of drinking were seen at 1, 6 and 12 months after the advice.

There was not enough information to help us decide if advice was better from computers, telephones or the internet to reduce risky drinking. We do not know which pieces of advice were the most important to help people reduce problem drinking. However, advice from trusted people such as doctors seemed helpful, as did recommendations that people think about specific ways they could overcome problems that might prevent them from drinking less and suggestions about things to do instead of drinking. We included five studies which compared the drinking of people who got advice from computers or mobile devices with advice from face‐to‐face conversations with doctors or nurses; there may be little or no difference between these to reduce heavy drinking.

No studies reported whether any harm came from the interventions.

Personalised advice using computers or mobile devices may help people reduce heavy drinking better than doing nothing or providing only general health information. Personalised advice through computers or mobile devices may make little or no difference to reduce drinking compared to face‐to‐face conversation.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence was moderate‐to‐low quality.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Digital intervention compared to no or minimal intervention for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in community‐dwelling populations.

| Digital intervention compared to no or minimal intervention for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in community‐dwelling populations | ||||||

| Patient or population: People living in the community Setting: Online, primary care, social care, educational, workplace Intervention: Digital intervention Comparison: No or minimal intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no or minimal intervention | Risk with digital intervention | |||||

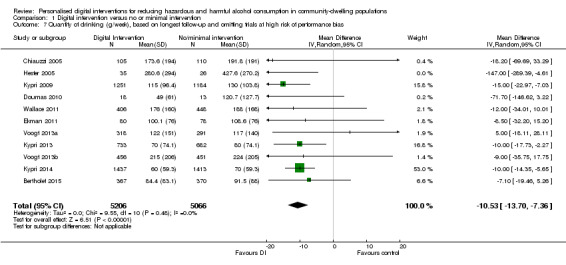

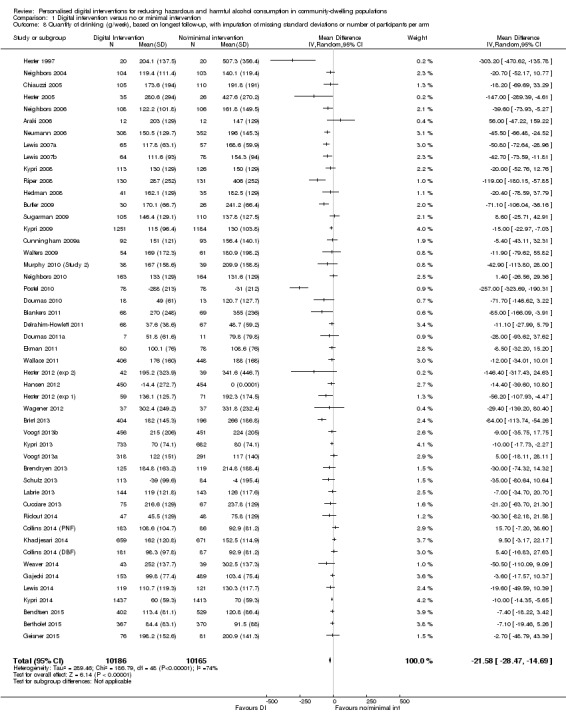

| Quantity of drinking (g/week), based on longest follow‐up (quantity) follow up: range 1 month to 12 months | The mean quantity of drinking (g/week), based on longest follow‐up was 176 g/week | MD 23 g/week lower (30 lower to 15 lower) | ‐ | 19,241 (41 RCTs, 42 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Heterogeneity was substantial (78%) but not unexplained; interventions differed in content and delivery. The direction of effect favoured the intervention in 88% of the studies. |

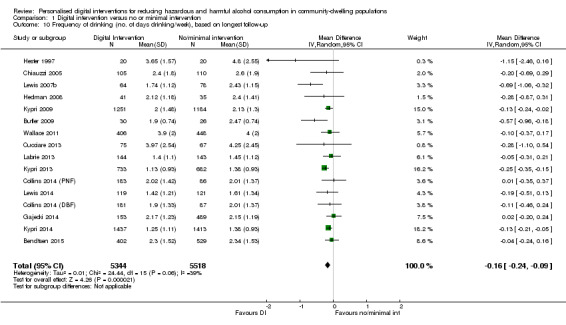

| Frequency of drinking (number of days drinking/week), based on longest follow‐up (frequency) follow up: range 1 month to 12 months | The mean frequency of drinking (number of days drinking/week), based on longest follow‐up was 2.5 drinking days/week | MD 0.16 drinking days/week lower (0.24 lower to 0.09 lower) | ‐ | 10,862 (15 RCTs, 16 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

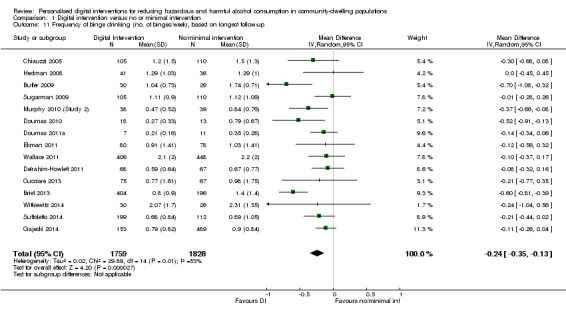

| Frequency of binge drinking (number of binges/week), based on longest follow‐up follow up: range 1 month to 12 months | The mean frequency of binge drinking (number of binges/week), based on longest follow‐up was 1.2 binges/week | MD 0.24 binges/week lower (0.35 lower to 0.13 lower) | ‐ | 3587 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Heterogeneity was moderate (53%) but not unexplained; interventions differed in content and delivery. The direction of effect favoured the intervention in 93% of the studies. |

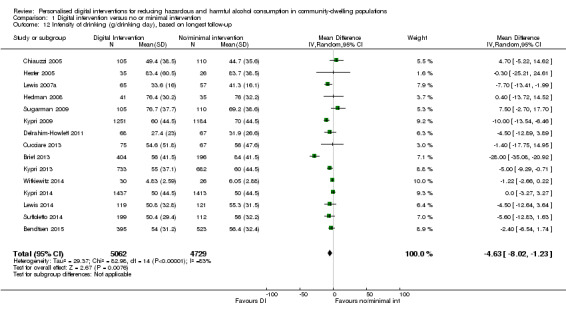

| Intensity of drinking (g/drinking day), based on longest follow‐up (intensity) follow up: range 1 month to 12 months | The mean intensity of drinking (g/drinking day), based on longest follow‐up was 56 g/drinking day | MD 5 g/drinking day lower (8 lower to 1 lower) | ‐ | 9791 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Heterogeneity was substantial (78%) but not unexplained; interventions differed in content and delivery. The direction of effect favoured the intervention in 73% of the studies. |

| Adverse events | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies assessed this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded due to high risk of attrition or performance bias or both in many studies. A sensitivity analysis based on the primary meta‐analysis, which omitted studies at high risk of performance bias and contained 11 studies, suggested that the intervention led to a reduction of at least 11 g alcohol (7 to 14 g) or 1.5 UK units (Analysis 1.7).

Summary of findings 2. Digital intervention compared to face‐to‐face intervention for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in community‐dwelling populations.

| Digital intervention compared to face‐to‐face intervention for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in community‐dwelling populations | ||||||

| Patient or population: People living in the community Setting: Online, primary care, social care, educational, workplace Intervention: Digital intervention Comparison: Face‐to‐face intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with face‐to‐face intervention | Risk with digital intervention | |||||

| Quantity of drinking (g/week), based on longest follow‐up (quantity) follow up: range 1 month to 12 months | The mean quantity of drinking (g/week), based on longest follow‐up was 180 g/week | MD 0.52 g/week higher (24.59 lower to 25.63 higher) | ‐ | 390 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

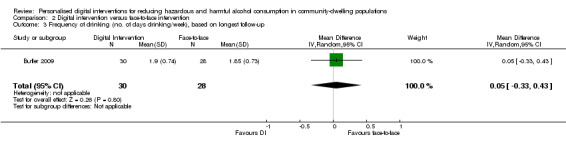

| Frequency of drinking (number of days drinking/week), based on longest follow‐up (frequency) follow up: range 1 months to 12 months | The mean frequency of drinking (no. of days drinking/week), based on longest follow‐up was 1.85 drinking days/week | MD 0.05 drinking days/week higher (0.33 lower to 0.43 higher) | ‐ | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Frequency of binge drinking (number of binges/week), based on longest follow‐up | The mean frequency of binge drinking (no. of binges/week), based on longest follow‐up was 0.7 binges/week | MD 0.04 binges/week higher (0.15 lower to 0.22 higher) | ‐ | 206 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Intensity of drinking (g/drinking day) | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies assessed this outcome. |

| Adverse events | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies assessed this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to serious risk of bias (high risk of attrition or performance bias or both).

2 Downgraded one level due to serious imprecision (fewer than 400 participants).

Background

Description of the condition

Excessive drinking contributes significantly to physical and psychological illness, injury and death, and a wide array of social harm in all age groups (WHO 2014). Of all deaths worldwide, nearly 6% are attributable to alcohol consumption, and alcohol contributes to over 60 diseases as well as many accidents and injuries. Approximately 5% of the global burden of disease and injury is attributable to alcohol, as measured in disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs).

Alcohol contributes to 20% of deaths due to road traffic accidents, 30% of deaths caused by oesophageal and liver cancers, epilepsy and homicide, and 50% of all deaths caused by liver cirrhosis (WHO 2009). Although drinking limited amounts of alcohol has been reported to decrease the incidence of a small number of diseases and can have a positive social effect, the net effect of alcohol consumption is detrimental to health. The economic cost – including both health and social harms, such as property damage and domestic violence relating to alcohol consumption – tends to amount to more than 1% of gross domestic product in high‐ and middle‐income countries (Rehm 2009).

Excessive drinking can include hazardous, harmful and high‐intensity consumption. People drinking hazardously display a repeated pattern of drinking above recommended limits and are at risk of (but not yet experiencing) physical or psychological harm, whilst those drinking harmfully are drinking above recommended limits and currently experiencing harms (WHO 1992). Hazardous or harmful patterns of alcohol consumption can involve either regular exceeding of consumption guidelines, or high volume consumption which can be regular or infrequent and which is known by a number of terms such as single episode high‐intensity drinking, heavy episodic drinking or often as 'binge' drinking (Herring 2008). There are more people who exhibit hazardous, harmful or high‐intensity drinking than those with alcohol dependence (e.g. McManus 2009 in the UK). At a population level, the greatest impact on alcohol‐related problems can be made by addressing interventions for people who exhibit hazardous, harmful or high‐intensity drinking (McGovern 2013).

Description of the intervention

An evidence‐based strategy for reducing excessive alcohol consumption levels is to offer a brief intervention in primary care settings provided by general practitioners, nurses or other generalist health professionals; this strategy is backed up by findings from 24 systematic reviews and meta‐analyses, encompassing 56 unique trials (O'Donnell 2013). A Cochrane Review incorporating a meta‐analysis of 22 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) found that face‐to‐face brief interventions in primary care settings were consistently effective at reducing excessive drinking, producing an average reduction of 38 g (4 to 5 UK standard drink units) per week (Kaner 2007). These interventions typically comprise a conversation of anywhere between 5 and 45 minutes, include an initial screening process to identify people who are experiencing alcohol‐related risk or harm, provide personalised feedback on alcohol use and harms, identify high‐risk situations for drinking and coping strategies, suggest strategies to increase motivation for positive behaviour change, and develop a personal plan to reduce drinking. This intervention is effective when delivered by a range of health practitioners (Sullivan 2011) and a cost‐effective alcohol risk reduction strategy (Purshouse 2013). Despite clear benefits of face‐to‐face brief alcohol interventions, some heavy drinkers are reluctant to seek help or unable to attend health services, and there are various barriers to delivery from the perspective of health professionals, which results in comparatively low rates of intervention (Brown 2016). Recent technological innovations have enabled people to interact directly via computers, mobile devices or smartphones with digital interventions designed to address problem alcohol consumption using some of the same intervention content (Khadjesari 2011).

How the intervention might work

Digital interventions for alcohol consumption include some of the same features as face‐to‐face interventions to motivate the person to reduce alcohol consumption over time; for example personalised feedback, engaging the person in creating coping strategies and goal‐based plans.

Face‐to‐face brief interventions have generally been found to be effective (Kaner 2007), but various differences should be considered when translating these interventions to a digital medium:

Setting: most of the cited evidence on face‐to‐face studies of brief interventions (Kaner 2007) took place in general practice or emergency care‐based primary care, although there is a growing literature on other health settings, such as general hospital wards (McQueen 2011). However, screening for hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption may not occur or be implemented consistently or reliably in busy healthcare settings and may miss people with problems. Barriers to implementation of alcohol interventions (McAvoy 2001) include excessive drinkers not attending primary care settings, and practitioners being too busy to engage in this work (Wilson 2011). Digital interventions have been proposed as a means of accessing hard to reach groups outside health settings, and also to provide a cheaper alternative to interventions delivered by health professionals within health settings (Kaner 2011).

Modality: digital interventions differ considerably in their modality or delivery mechanism, which may present advantages and disadvantages. Some people may find disclosing excessive alcohol consumption easier if they feel anonymous, but others may feel that their data confidentiality may be at risk if entered and stored electronically. It is possible that face‐to‐face intervention outcomes may be due, at least in part, to therapist effects; greater outcome effects have been reported for delivery by physicians compared to other practitioners (Sullivan 2011). It is also plausible that a smartphone app which can be used anywhere and at any time at the user’s discretion may produce a different effect to a specific computer sited in a primary care practice, despite the actual content being very similar.

Timing: published evidence suggests that alcohol intervention effects may decay over time for face‐to‐face brief interventions (Moyer 2002), which may also apply to digital interventions. Nevertheless, the scope for repeated intervention may potentiate initial effects. Whereas a face‐to‐face intervention is often delivered as a one‐off event (although there can be several sessions), digital interventions may be used as a one‐off or more frequently and regularly over an extended time period.

Population: differences in effectiveness may arise for different population groups due to variations in enthusiasm for (e.g. technophilia versus technophobia) or access to technology; for example by age, gender, ethnicity, or socio‐economic status.

Most brief interventions are typically structured according to a FRAMES approach which includes: giving Feedback on the person's intake, impressing the Responsibility for change onto them, offering Advice, listing a Menu of options, having an Empathic approach, and building Self‐efficacy (Miller 1994). However, intervention components are more complex in that they are usually made up of several behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and may incorporate several stages. A BCT is “an observable, replicable, and irreducible component of an intervention designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behaviour" (Michie 2013; Michie 2015).

To identify the ‘active ingredients’ within interventions, it is important to document the component BCTs using a reliable method. For example, an analysis of brief interventions, based on the trials in the Cochrane Review by Kaner 2007 and using a reliable taxonomy of BCTs, identified self‐monitoring as an effective component of these health promoting approaches (Michie 2012).

Economic modelling based on published studies to date has suggested that a programme of face‐to‐face brief interventions rolled out in primary care would be cost‐effective compared to no programme; providing additional health benefits at reduced health service cost (Angus 2014; Purshouse 2013). Little has yet been published on the cost‐effectiveness of digital alcohol interventions, although one study (Blankers 2012) suggested that internet‐based therapy (including a therapist) is more cost‐effective than internet self‐help. A question remains on the relative cost‐effectiveness of digital versus face‐to‐face interventions.

Why it is important to do this review

An overview of reviews (Kaner 2012) identified a large and relatively well‐designed research literature with around 35 published trials in this field around the beginning of the current decade (e.g. Carey 2009a; Khadjesari 2011; Rooke 2010; White 2010). Since this point, the number of trials has increased significantly, and a number of systematic reviews of this evidence base have reported findings often in specific population subgroups. This body of work included the use of technology to deliver alcohol interventions in educational contexts, health and social care settings, and other community‐based settings as well as via the internet or mobile phone applications. In this review we advanced upon previous reviews by taking a public health (secondary) prevention perspective and focusing on people living in the community who were not seeking formal treatment for alcohol‐related problems but nonetheless were drinking at a level which could cause them risk or harm. Participants had to have undergone a screening process to assess drinking behaviour, and risky or harmful drinkers had to engage with any digitally delivered intervention designed to help reduce alcohol consumption. We did not restrict our focus by type of digital intervention so as to capture all interventions targeting this population, and include interventions which take place on multiple platforms (e.g. text prompts to use smartphone apps). We also compared the effect of digital alcohol interventions to face‐to‐face brief alcohol interventions often delivered by health professionals. Health professionals are an established part of public health policy (e.g. UK Government 2012), but practitioners report limited time to screen and deliver alcohol intervention to patients. In addition, some people may be reluctant to disclose heavy alcohol consumption to doctors, nurses or other practitioners. Finally, the digital intervention field is a fast‐moving and rapidly evolving field, so it is crucial to keep the evidence base up to date.

Objectives

The main objective of this review was to assess the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of digital interventions for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption,alcohol‐related problems, or both in people living and recruited from the community. Specifically, we addressed the following questions:

Are digital interventions more effective and cost‐effective than no intervention (or minimal input) controls?

Are digital interventions at least equally as effective as face‐to‐face brief alcohol interventions?

What are the effective component behaviour change techniques (BCTs) of such interventions and their mechanisms of action?

What theories or models have been used in the development and/or evaluation of the intervention?

Secondary objectives were as follows:

To assess whether outcomes differ between trials where the digital intervention targets participants attending health, social care, education or other community‐based settings and those where it is offered remotely via the internet or mobile phone platforms.

To specify interventions according to their mode of delivery (e.g. functionality features) and assess the impact of mode of delivery on outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with individual, cluster, or stepped wedge designs. We did not restrict inclusion by language or publication status.

Types of participants

Participants were people living in the community whose alcohol consumption had been screened as hazardous or harmful (WHO 1992) and who were directed toward any digital intervention including web‐based, mobile phone text messaging, smartphone apps, social networking, or stand alone computer‐based technologies (including CD‐ROMs). Recruitment was via a range of settings, including primary healthcare (including emergency departments and community midwifery services), social care, educational, workplaces or the internet. No restriction was applied to where participants interacted with the intervention, since it could be delivered through mobile devices. We did not restrict to a particular age group because we aimed to assess the effectiveness of digital alcohol interventions for all current drinkers who were likely to experience risk or harm due to alcohol consumption. Although some countries restrict the age at which people can legally purchase alcohol, this does not necessarily mean it is illegal to drink alcohol (except in very young children). As an example, in the UK it is not legally permissible for people under the age of 18 years to purchase alcohol. However, it is legal for these people to drink alcohol provided by family members in their homes; the current UK lower legal age at which alcohol can be consumed under supervision is five years of age (UK Government 2017).

Studies were excluded if:

interventions were directed mainly toward people who were seeking specialist health or social care treatment for their alcohol consumption, or who were in treatment for, or recovery from, alcohol dependence (e.g. 12‐step programmes);

interventions were directed mainly at primary prevention, i.e. preventing or delaying the onset of alcohol consumption;

interventions were delivered in a secondary or tertiary care setting;

interventions were delivered to people who were not living freely in the community (e.g. prisoners);

interventions were targeted at someone other than the drinker (e.g. at a significant other or someone serving alcohol);

participants were under obligation to complete the intervention, or had extra motivation to reduce their drinking, e.g. mandated college students (where low consumption satisfies the mandate) or interventions associated with drink driving. The effect of the mandate to complete the intervention or to reduce consumption would give participants extra motivation compared to those using the intervention freely, which might confound the results; or

participants were screened according to their alcohol consumption but it did not have to be hazardous, e.g. participants reported consuming alcohol in the last month.

Types of interventions

Interventions were digital, defined as being delivered primarily through a programmable computer or mobile device (laptop, phone or tablet), and were responsive to user input to generate personalised content which aimed to change the participants’ alcohol‐related behaviours. Interventions were not restricted to those accessible online.

Interventions targeting multiple behaviours (e.g. other substance abuse) or conditions (e.g. depression) were included if all participants were screened into the trial as risky drinkers and alcohol consumption data were reported separately.

For primary objectives 1 and 3 the control condition was no intervention (screening or screening and assessment only), printed or onscreen health or alcohol‐related information, or in a health setting the care the patient would have received anyway for their presenting complaint. For primary objective 2, the control condition was a face‐to‐face brief intervention to reduce alcohol consumption or harm.

Studies were excluded if:

the intervention was limited to replicating a real‐time talk‐based intervention (e.g. a conversation by mobile phone). Trials of real‐time interventions which were not talk‐based (e.g. instant messaging), or talk‐based interventions which were not in real time (e.g. on video/DVD/YouTube where replay was available) were included;

digital technology was used to screen participants into the study but the advice or behaviour change element was solely face‐to‐face;

two digital interventions were compared to each other with no control arm; or

the intervention did not generate feedback or other output based on the personal characteristics of the user (e.g. generic educational interventions).

Types of outcome measures

Studies were included if they measured alcohol consumption in grams of alcohol per week (and converted from other measures where possible). We included quantity (g/day), frequency (drinking days/week) and intensity (drinks/drinking day) of consumption in 'Summary of findings' tables. We assessed outcomes on the basis of the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) incorporated in the interventions, their theoretical underpinning, and mechanisms of action as reported elsewhere (Webb 2010).

Primary outcomes

Many types of outcome measures are available in the alcohol literature. Our primary outcome was quantity of alcohol consumed, which we converted into grams of alcohol per week using either definitions in the trial report where available, or from governmental definitions (listed in Kalinowski 2016). We considered trials reporting outcomes at one month or longer post‐intervention, but separated trials according to follow‐up time, as well as by longest follow‐up time.

Secondary outcomes

Other measures of consumption (e.g. number of binge episodes, frequency of drinking occasions, number of participants exceeding limits as defined by study authors).

Indices of alcohol‐related harm or social problems to the drinkers or affected others.

Cost‐effectiveness.

Any reported adverse effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following sources of information were used to capture studies for the review. The search was not limited by publication status, language or date (some digital interventions, such as CD‐ROMs, were available in the 1980s).

Electronic searches

We used thesaurus headings (such as MeSH headings in MEDLINE), title and abstract terms, and the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for randomised trials: sensitivity‐maximising version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). The search strategy was designed in MEDLINE on OVID (Appendix 1) and translated as appropriate to other databases searched.

MEDLINE (OVID) 1946 to March week 1 2017, searched 15 March 2017 (Appendix 1).

PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), searched 29 January 2016.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Wiley) issue 3 2017, searched 18 March 2017 (Appendix 2).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Wiley) issue 2 2017, searched 18 March 2017.

Database of Abstract of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (Wiley) issue 2 2015, searched 18 March 2017.

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) (Wiley) issue 1 2017, searched 18 March 2017.

PsycINFO (OVID) 1967 to March week 1 2017, searched 15 March 2017 (Appendix 3).

CINAHL (EBSCO) 1981 to March 2017, searched 18 March 2017 (Appendix 4).

ERIC (EBSCO) 1966 to March 2017, searched 23 March 2017 (Appendix 5).

SCI Science Citation Index (Web of Knowledge) 1970 to March 2017, searched 23 March 2017 (Appendix 6).

CPCI‐S Conference Proceeding (Web of Knowledge) 1990 to March 2017, searched 23 March 2017 (Appendix 6).

International Alcohol Information Database (ICAP) www.drinksresearch.org, searched 16 January 2015 (unavailable when running update March 2017).

Index to Theses www.theses.com searched 15 April 2014.

British Library EThOS ethos.bl.uk searched 25 March 2017.

Clinicaltrials.gov searched 25 March 2017.

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) www.who.int/ictrp/en searched 25 March 2017.

Google Scholar searched 25 March 2017.

We searched the following websites for evaluations of digital interventions:

Beacon 2.0 beacon.anu.edu.au

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) NREPP (National Registry of Evidence‐based Programs and Practices) nrepp.samhsa.gov/Index.aspx

Drug and Alcohol Findings findings.org.uk.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all included studies and relevant reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened all titles and abstracts identified from the search, using EndNote version X7 (Endnote 2014) to ensure consistency in screening approach. The full text of any studies identified as being potentially eligible for inclusion were assessed by two review authors independently. Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third review author.

Data extraction and management

Separate data extraction forms were developed and piloted in MS Excel for outcome extraction, BCT coding and theory coding. These were used by two independent review authors to extract data from all included studies (8 review authors extracted outcomes data and 2 review authors extracted theory and BCT data). Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third review author.

Outcome data

Outcome data were extracted as follows: details of the intervention (e.g. setting, duration, mode of delivery and costs), participants (size and characteristics of sample), trial design (to enable critical appraisal), and baseline and follow‐up consumption data (all reported follow‐up points).

Behaviour change techniques (BCT) data

All studies were coded for BCTs using a taxonomy of 93 distinct BCTs (BCTTv1) developed by consensus methods with input from a large group of international behaviour change experts (Michie 2015; Michie 2013). Intervention descriptions were read line‐by‐line, text that may indicate the presence of a BCT was highlighted, and highlighted text was compared to the definition for the BCT given in the taxonomy (Michie 2013). A BCT was coded as included only when it was explicitly present.

The reliability of the method was developed and assessed in iterative rounds of coding. Two review authors independently coded a sample of five studies. Coding differences were resolved through discussion and the coding manual was reviewed and updated in the light of these discussions. If agreement could not be reached, the views of a behaviour change expert were sought. Inter‐rater reliability (IRR) was assessed with both the Kappa and prevalence‐adjusted bias‐adjusted Kappa (PABAK) statistics. Cohen’s Kappa accounts for coders agreeing on the presence of codes (Landis 1977). PABAK is an adjusted Kappa statistic that accounts for coders agreeing on the presence and the absence of codes (Byrt 1993). Whilst it is important to measure levels of agreement about the absence of BCTs, using PABAK alone could result in the reporting of exaggerated levels of agreement when coding against a taxonomy of 93 BCTs, most of which were unlikely to be used in any one intervention (Direito 2014; Dombrowski 2012). Therefore, IRR was assessed with both statistics. The first round of joint coding lead to an IRR of Kappa = 0.73, PABAK = 0.95, which reflects a substantial level of agreement (Landis 1977). As this exceeded the pre‐determined threshold of Kappa = 0.70, remaining studies were coded by one review author, with the second coding 22% (8/36) of the same studies to ensure against rater drift. The IRR for all included studies that were also joint coded was Kappa = 0.73, PABAK = 0.96, n = 13 (for all joint‐coded studies prior to exclusion: Kappa = 0.70, PABAK = 0.95, n = 38/90).

Theory data

The extent to which a theory or model of behaviour was used in the development or evaluation of the intervention was investigated with the 19‐item Theory Coding Scheme (Michie 2010). Two review authors independently coded a sample of five studies and differences were resolved through discussion. The coding guidelines were amended in accordance with these discussions. If agreement was not reached, the views of a behaviour change expert were sought. IRR was assessed with the PABAK statistic as described previously (Byrt 1993). Further rounds of testing were performed until the IRR reached a substantial level of agreement (≥ 0.70; Landis 1977). After this level of agreement was achieved, the remaining studies were coded by one review author. The PABAK statistic across the five rounds of IRR checking was 0.84 which reflects a substantial level of agreement. The Theory Coding Scheme has 19 items; two of these items (quality of measures and randomisation of participants to condition) were not evaluated in this Cochrane Review because they relate to methodological issues rather than informing whether or how theory was used in an intervention. Of the 17 items coded, three had sub‐items (12a, 12b, 14a, 14b, 14c, 14d, 17a, 17b). If a theory or model of behaviour was mentioned (item 1), then the relevant name was documented. Each of the 22 items and sub‐items were dummy coded as present (1) or absent (0). If a protocol or other paper was referenced as describing the intervention, then that paper was also coded for use of theory, although only for items 1 to 11 which relate to the development of the intervention rather than the evaluation.

The Theory Coding Scheme specifies theory use in six categories (Michie 2010); reference to underpinning theory (items 1 to 3); whether any relevant theoretical constructs are targeted by the intervention (items 2, 5, and 7 to 11); whether theory was used to select recipients or tailor interventions (items 4 and 6); measurement of constructs (items 12a and 12b); whether mediation effects were tested (items 12a and 12b, 13, 14a to 14d, 15, 16); whether the results of the study were used to refine theory (items 17a and 17b). Composite scores were calculated for these six areas of theory use. A total use of theory score (sum of all items) was also calculated. These composite scores were used as a crude estimate of the extent of theory use in specific areas, or in total, as a basis of assessing the relationship between that and the effect size of the intervention.

There were two pairs of items (items 7 and 8; items 10 and 11) in the Theory Coding Scheme that refer to “all” and “at least one”, respectively. For the composite scores of theory use, if the all items (7 and 10) were coded as 1 then the at least one item was also coded as 1 (as in Webb 2010). This was to ensure that the composite scores of theory use were representative of the studies and that studies credited with linking all theoretical constructs (for example) are also credited as linking some. Otherwise, linking one theoretical construct would give the same contribution toward the use of theory score as would linking all the constructs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias was assessed independently by two review authors using the criteria recommended in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane Reviews is a two‐part tool, addressing seven specific domains: sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and providers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), and other sources of bias. The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry, in terms of low, high or unclear risk. To make these judgments we used the criteria indicated by the Handbook adapted to the addiction field (see Appendix 7 for details).

'Risk of bias' assessments were used to carry out sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Measures of treatment effect

Consumption outcomes

For continuous variable outcomes (e.g. quantity of alcohol consumed) we examined mean differences (MD) with the uncertainty in each result being expressed with a 95% confidence interval (CI), and for dichotomous outcomes (e.g. participants classified as binge drinker, or drinking over set limits) we examined proportions using relative risks (RR) with 95% CI. Where outcomes had been assessed at more than one time, data for each time point were extracted. The primary analyses focused on the longest follow‐up time.

Unit of analysis issues

It had been planned that for trials with more than one – and very similar – control arms, the results for these arms would be combined in the meta‐analysis. However, this was not required since, as described in the Results section, there was only one relevant control arm for each trial included in the meta‐analysis. The same approach was planned for very similar intervention arms. However, it was not used, since for trials with more than one relevant intervention arm, the results for each arm were analysed separately because the interventions were substantively different from each other so it was not appropriate to combine them (Collins 2014 (DBF); Collins 2014 (PNF)).

Cluster randomised trials were eligible for inclusion in the meta‐analysis. If the analysis in a trial reported a standard error for the intervention effect that accounted for the cluster design, then, so data could be presented and analysed in the same manner as for non‐cluster trials, we assigned imputed standard deviations to the intervention and control groups such that the standard error of the intervention effect calculated by the weighted mean difference method in Review Manager 2014 was the same as the reported standard error. If the analysis in a trial report did not account for the cluster design, we had planned to add an external estimate of the intra‐cluster coefficient (ICC) to estimate a design effect, thus inflating the variance of the effect estimate. However, this situation did not occur in the trials included in the meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to obtain missing data and seek clarification where appropriate. Where this was impossible, we estimated primary outcome measures using secondary outcome measures; for example, we estimated quantity of alcohol consumed using frequency and intensity of consumption, although it was not possible to estimate the associated standard deviation. Trials with missing standard deviations or for which the number of participants in each arm was not reported were excluded from the main analysis for the associated continuous measure, but were included in a sensitivity analysis, using imputed values for the standard deviations or the number of participants in each arm.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The magnitude of heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic, and the statistical significance of the heterogeneity was assessed using P values derived from Chi² tests (Deeks 2001). The cut‐off points were I² value of more than 50% and a P value for the Chi² test of less than 0.1. Heterogeneity was explored both narratively and using subgroup and sensitivity analyses. The trials were heterogeneous, due not only to the variation in delivery methods (e.g. web, app, CD‐ROM) but also to aspects of content (e.g. focus on feedback versus behaviour change, duration of exposure).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed whether studies appeared to have incomplete reporting bias by noting in the risk of bias assessments whether the reported outcomes matched methods sections or any published protocols. We made every effort to minimise publication bias by searching a wide range of databases and sources of grey literature and not restricting by language or publication status, but we used funnel plots to assess the potential for bias related to the size of the trials when there were at least 10 studies included in the meta‐analysis. Funnel plots and associated approximate (pseudo) 95% confidence limits were calculated using the meta‐funnel option in Stata version 14 (Stata 2015).

Data synthesis

We pooled data for each outcome using a random‐effects model in a meta‐analysis that compared intervention and control arms using Review Manager 2014. For continuous measurements, the weighted mean difference was calculated to estimate pooled effect sizes and 95% CIs. If means or standard deviations at follow‐up were not available, change scores were used instead on the proviso that their standard deviations were available. If the median and inter‐quartile range were reported in place of the mean and standard deviation, then the mean and standard deviation were estimated from the inter‐quartile range. If only the mean difference and its 95% CI were reported (e.g. as in Hansen 2012), then data were entered into Review Manager 2014 so that the reported values for the mean difference and CI were included in the meta‐analysis. For dichotomous outcomes, relative risks and 95% CIs were calculated and pooled in a meta‐analysis using Mantel‐Haenzel weighting.

Where possible, we had planned to consider key population groups such as men versus women, older versus younger participants, and different socio‐economic groups. However, the opportunity for analyses of these types was limited by the availability of relevant data.

We planned to estimate long‐term cost‐effectiveness of strategies for the use of internet, mobile phone text messaging, smart phone app interventions or computer‐based technologies by adapting the current Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model (SAPM) analysis of screening and brief interventions, but we found insufficient data. Instead, we included a summary review of the available studies with economic findings.

Behaviour change technique (BCT) analysis

The revised metareg command in Stata version 14 (Stata 2015) was used to conduct a series of random‐effects unadjusted meta‐regression models to assess the associations between individual BCTs and effect size. The regression coefficients (B) represented an estimate of effect (mean difference (MD) in quantity of drinking, expressed in grams per week) per unit increase in the covariate (dummy‐coded as 1 = used the BCT or 0 = did not use the BCT). Only BCTs uniquely present in experimental arms, i.e. not present in both experimental and control arms, were included in analyses. A negative coefficient for a BCT indicated that studies using that BCT produced a larger pooled effect than studies that did not. The approach used in a previous meta‐regression study of the BCTs contained within physical activity and healthy eating interventions was adopted (Michie 2009); to be included in analysis, each BCT needed to be used in at least four separate studies.

To assess the independent association after mutual adjustment, we created a multivariable meta‐regression model including all BCTs that had a meaningful association with effect in the unadjusted models. A meaningful association was defined a priori as B < ‐23, which in absolute terms was the lower confidence interval of the effect size reported in a meta‐analysis of the effect of brief advice on alcohol consumption (Kaner 2007). The lower confidence interval of the previous Cochrane Review by Kaner 2007 was chosen to enable comparisons between the effectiveness of face‐to‐face and digital interventions. The size and significance of the associations in the multivariable model were regarded as providing the primary indication of association between BCTs and effect.

To assess the association between the total number of BCTs included in experimental arms and effect size we created a random‐effects unadjusted meta‐regression model. Lastly, we assessed the overall fit of a model, in terms of adjusted R², containing only a theoretically derived cluster of Control Theory congruent BCTs. These BCTs were grouped into four categories: Goals (goal setting (behaviour), goal setting (outcome), review behaviour goal(s), review outcome goal(s), discrepancy between current behaviour and goal)); self‐monitoring (self‐monitoring of behaviour, self‐monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour, monitoring of emotional consequences); feedback (feedback on behaviour, feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour, biofeedback) and action plans (action planning). Trials were dummy‐coded as 1 = used BCTs from three or four of these groupings; or 0 = used BCTs from two or less of these groupings.

Theory analysis

Frequency counts and descriptive statistics were used to describe the theoretical basis for digital interventions of alcohol reduction. The range and frequency of theories used were tabulated.

A series of random‐effects unadjusted meta‐regression analyses were conducted to examine the association between the Theory Coding Scheme covariates (individual theory items, required to be included by at least 10% of studies; categories of theory use; and total theory use), with intervention effectiveness and the percentage of the between‐study heterogeneity (adjusted R²) explained by each predictor.

The meta‐regression analyses were conducted in Stata version 14 (Stata 2015) using the metareg command. Effect sizes were based on a random‐effects model because the intervention effects were likely to have residual heterogeneity not modelled by the covariates. The effectiveness of the intervention was measured using the primary outcome measure of difference in quantity of alcohol consumption (g of ethanol) per week between the digital intervention and control arms at the longest follow‐up time point. The weighted mean difference was calculated to estimate pooled effect sizes and 95% CIs.

In these analyses, the regression coefficient (B) represented an estimate of effect (mean difference in quantity of alcohol consumption, g/week) per unit increase in the covariate. A negative coefficient for a covariate indicated that studies reporting that theory item, or with higher scores on the categories of theory use and total theory use, were associated with a larger reduction in consumption than studies that did not. The P value indicated whether the B weight was statistically significantly different from zero, based on a two‐sided test. The adjusted R² value indicates the proportion of between‐study variance explained by each predictor.

To investigate the independent associations, an adjusted meta‐regression analysis was conducted, including all of the variables that had a meaningful association with effect in the unadjusted models. As before, a meaningful association was defined as B < ‐23 as for the BCT models.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were carried out based on:

Timing of outcomes: to investigate possible decay over time, based on a pragmatic grouping of trials according to the follow‐up time points reported.

Component BCTs (Michie 2013) as a comparison for face‐to‐face brief interventions.

Theoretical basis of the interventions.

Key population subgroups: by age (adolescents and young adults) and gender.

We also planned to carry out a subgroup analysis based on socio‐economic status but insufficient information was reported in the included trials.

We planned to undertake a subgroup analysis according to mode of delivery of interventions (e.g. web sites versus smartphone app), but most were delivered via web sites and there were insufficient trials of interventions delivered via other mechanisms.

Funnel plots split by subgroups and meta‐regressions on longest period of follow‐up and on year of publication were constructed using Stata version 14 (Stata 2015).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses by investigating the effect of omitting studies with either a high risk of attrition bias or a high risk of performance bias (due to lack of participant blinding). We also investigated the sensitivity of the analysis based on the primary outcome measure to including studies with unknown standard deviations (by inputting the median SD from studies that did report this) or unknown numbers of participants per arm (by assuming approximately equal numbers in each arm, based on the total number of participants at the time in question).

'Summary of findings' tables

We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence.

The GRADE Working Group developed a system for grading the quality of evidence (GRADE 2004; Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2011), which takes into account issues not only related to internal validity but also to external validity, such as directness of results. The 'Summary of findings' tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence:

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different .

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

GRADEpro GDT 2015 was used to import data from Review Manager 2014 for the main outcomes of quantity of drinking (g/week), frequency of drinking in terms of days/week and binges/week, and intensity of drinking (drinks/drinking day) for each of the comparisons (digital intervention versus control or minimal intervention, digital intervention versus face‐to‐face intervention). The tables were then imported back into the review (Table 1; Table 2).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

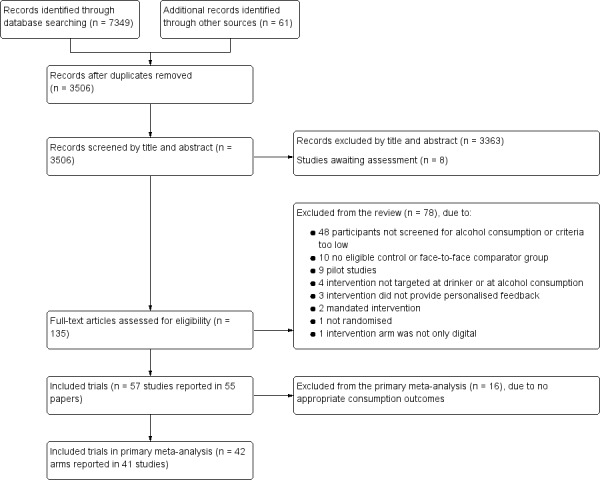

The search retrieved 3506 records after deduplication (Figure 1), which were screened by title and abstract in EndNote by two independent review authors. We excluded 3363 abstracts at this stage and retrieved the full text of 135 papers for further detailed evaluation, from which we selected 55 papers (reporting 57 studies) for inclusion in the review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Full details of the included studies are listed in the Characteristics of included studies section. We included 57 studies (reported in 55 papers) which randomised a total of 34,390 participants.

Of these, 33 studies were conducted in North America, 16 in mainland Europe, two in the UK, one in Japan, and five in Australasia.

One study recruited only women or girls (Delrahim‐Howlett 2011), three studies recruited only men or boys (Araki 2006; Bertholet 2015; Boon 2011), whilst another four studies recruited both but reported gender‐specific results (Chiauzzi 2005; Hansen 2012; Khadjesari 2014; Lewis 2007a). One study reported results by ethnicity (African American versus Caucasian students, Murphy 2010 (Study 1)).

Thirty‐seven studies considered teenagers, younger adults or students or both; the remaining 20 studies were specific to adults.

Thirty‐seven studies were based on interventions delivered completely online, and in 20 studies, the intervention was location specific.

Follow‐up times ranged from 1 to 24 months (median = 3 months). Fifty‐five trials compared a digital intervention to a no intervention or minimal intervention group, of which 41 reported appropriate information to be included in the primary meta‐analysis (one trial contained two substantially different intervention arms which were treated separately, so that there are 42 comparisons in the primary meta‐analysis). Seven trials included a comparison of a digital intervention versus a face‐to‐face intervention (Araki 2006; Blankers 2011; Butler 2009; Murphy 2010 (Study 1); Murphy 2010 (Study 2); Wagener 2012; Walters 2009), of which five (Butler 2009; Murphy 2010 (Study 1); Murphy 2010 (Study 2); Wagener 2012; Walters 2009) reported appropriate information to be included in the meta‐analysis. Six trials had a digital, face‐to‐face, and a no intervention control arm (Araki 2006; Blankers 2011; Butler 2009; Murphy 2010 (Study 2); Wagener 2012; Walters 2009).

A wide range of consumption outcomes was reported in the included trials, the most common were:

quantity of consumption in terms of mean or median units, drinks or grams per day, week, fortnight or month;

frequency of consumption in terms of percentage of drinking days over time or mean number of heavy drinking days;

intensity of consumption in terms of mean or median or peak drinks per drinking day or on the last or heaviest occasion;

screening tool results such as mean or median AUDIT or AUDIT‐C or FAST score, or percentage of participants over a certain score;

binge drinking percentage; and

blood alcohol concentration (BAC). BAC was reported as an estimate based on participants' self‐reported consumption rather than a direct measure so we did not use in the meta‐analysis because it was not adding to other self‐reported consumption measures.

We contacted one author because an outcome was reported differently in the tables than the text.

Study funding sources

Many (56%) studies were funded by government or research foundation funds. Some (11%) were funded by personal awards such as PhD fellowships. The rest of the studies did not report sources of funding.

Excluded studies

After checking the full text of studies we excluded 78 paper of 135 obtained (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). The most common reason for exclusion (n = 48) was that participants were not screened as hazardous or harmful drinkers ‐ including studies where participants only had to have consumed "any alcohol" or "one or two drinks" in the previous six months, and studies which aimed at primary prevention. Four studies were excluded because the target of the intervention was not the drinker themselves, or it was targeting other substances alongside alcohol and alcohol consumption could not be separated. The intervention was ineligible in six studies, including two where it was mandated (e.g. for university students who had to demonstrate reduced consumption to continue their courses). Other interventions were generic rather than personalised, or were not solely digital, or the feedback was not related to alcohol consumption. We excluded 10 studies because the comparator was either another digital intervention or the control group was not comparable to other studies. One study was excluded because it was not randomised, and nine because they were either pilot studies for which we had the full trial or aimed to test feasibility. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

Eight studies await classification (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). Four studies tested digital interventions in college students (Balestrieri 2016; Bock 2016; Leeman 2016; Gajecki 2017). Balestrieri 2016 replicated the Australian College Drinkers Check‐up intervention (Hester 2012 (exp 1); Hester 2012 (exp 2)) in the USA, and reported a reduction in consumption and alcohol‐related consequences in intervention participants compared to control. Leeman 2016 reported that a multi‐component web‐based intervention called THRIVE also reduced consumption, and Gajecki 2017 found no difference between an intervention group receiving access to a skills training smartphone app and control. Bock 2016 reported that an SMS‐based intervention (TMAP) reduced heavy drinking and alcohol‐related consequences. Another USA study (Muench 2017) tested different types of SMS messages in a population recruited online, and reported that an automated daily message can reduce drinking more than weekly self‐tracking, and that a tailored adaptive text produced the greatest effect sizes. Two studies reported no difference in consumption between a computer‐assisted brief intervention and control: one delivered to patients in a French emergency department (Duroy 2016), and the other to American post‐partum women (Ondersma 2016). Finally, Acosta 2017 reported a reduction in consumption in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) receiving a cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) web‐based intervention.

Ongoing studies

Three of the ongoing studies are evaluating the use of smartphone apps for reducing hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption. Two are taking place in the UK: the SIPS Jr trial (ISRCTN45300218) is recruiting adolescents (aged 14‐18 yrs) in emergency departments, and a second trial (ISRCTN40104069) is testing the Drink Less app in a UK population of hazardous and/or harmful alcohol users. Three apps (Promillekoll, PartyPlanner and TeleCoach) are being evaluated in a further trial recruiting Swedish university students (NCT02064998). Finally, ISRCTN10323951 is a trial of a web‐based self‐help intervention for hazardous drinkers with mild to moderate depression.

Risk of bias in included studies

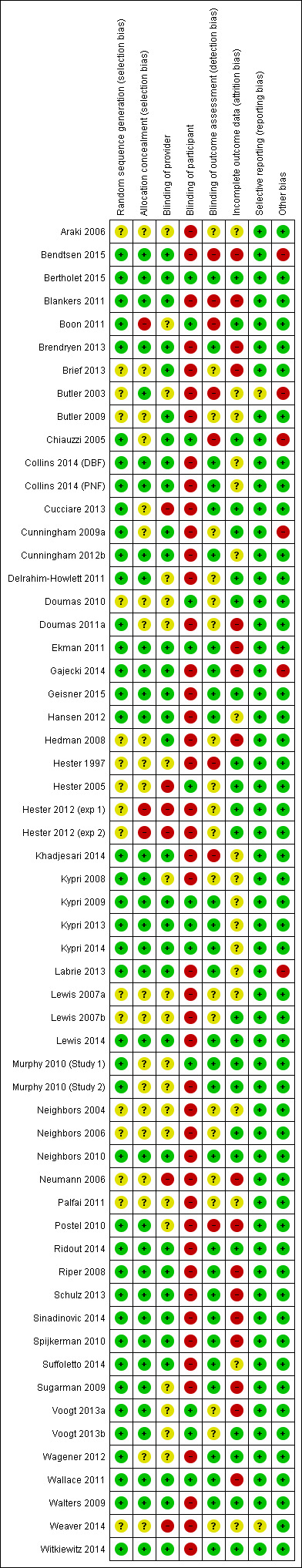

All reported outcomes in this review relate to self‐reported consumption of alcohol by participants, and so we have summarised the risk of bias at the study rather than the outcome level (Figure 2). Risk of bias assessments for each study are presented in Characteristics of included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Random sequence generation

None of the included studies were assigned high risk of bias due to the method of randomisation. Fifteen studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias due to randomisation because it was not clear whether the process was automated and the sequence generation process was not clearly reported. Forty‐one studies (72%) were considered to be at low risk of bias either because sequence generation took place as part of a completely automated assessment and intervention process, or because authors described using a computer‐generated sequence generation process.

Allocation concealment

It was clear from the description of the process in 29 studies that allocation was completely automated. These studies were judged to be at low risk of bias, along with an additional five studies that described allocation being conducted by someone independent of the trial, giving a total of 34 studies (60%) at low risk of bias due to allocation concealment. Two studies (4%) were judged to be at high risk of bias due to allocation concealment: Boon 2011 reported that the condition to which participants were assigned was revealed to research assistants once recruitment was complete; and in Hester 1997, a researcher was reported to log both intervention and control participants' data into the computer.

Blinding

Performance bias

Trials were judged by default to be at high risk of performance bias due to participant blinding because participants always knew that they were receiving alcohol‐related advice. However, if trials reported that there was an attempt to blind participants (e.g. by 'camouflaging' alcohol advice among other health‐related information) then the trial was assigned as low risk of bias in this respect ‐ 13 trials (23%) received this rating.

Detection bias

We judged 29 trials (51%) to be at low risk of detection bias. Eight trials (14%) (Bendtsen 2015; Blankers 2011; Boon 2011; Butler 2003; Chiauzzi 2005; Hester 1997; Khadjesari 2014; Postel 2010) were judged to be at high risk of bias because outcome assessment was not automated and researchers carrying out the assessments could have been aware of participant allocation. Outcome assessment for both intervention and control groups tended to occur by the same mechanism within individual trials, so we did not consider there was any difference in the risk of detection bias between intervention and control participants in the same trial.

Incomplete outcome data

The main source of bias in the included studies was due to attrition; follow‐up was challenging because there was often little face‐to‐face contact between trialists and participants. Trials were judged to be at high risk of attrition bias if loss to follow‐up was > 30% or if it was different between arms with no explanation to account for this; 17 trials (30%) were considered to be at high risk of attrition bias and 23 (40%) were judged to be at low risk.

Selective reporting

Selective reporting was not a major source of bias in the included studies. Most trials reported data for the same outcomes as they had specified in the protocol (where available) or methods section of the paper. Two trials (Butler 2003; Weaver 2014) were judged to be at unclear risk of bias because outcome values were not reported consistently.

Effects of interventions

1. Digital intervention versus no intervention or minimal intervention

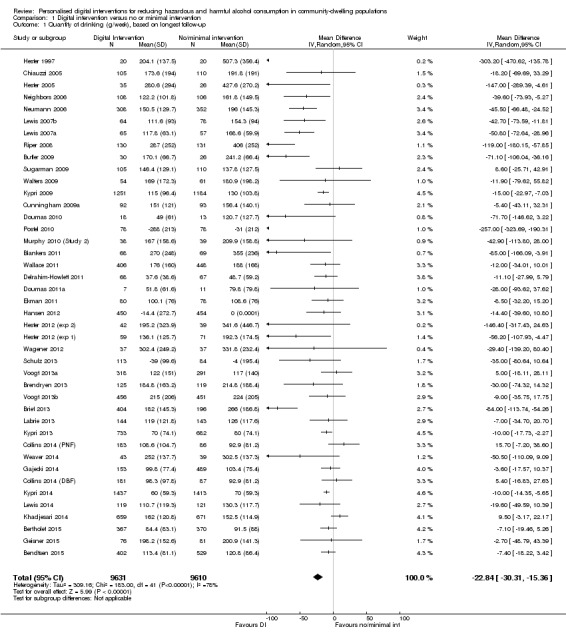

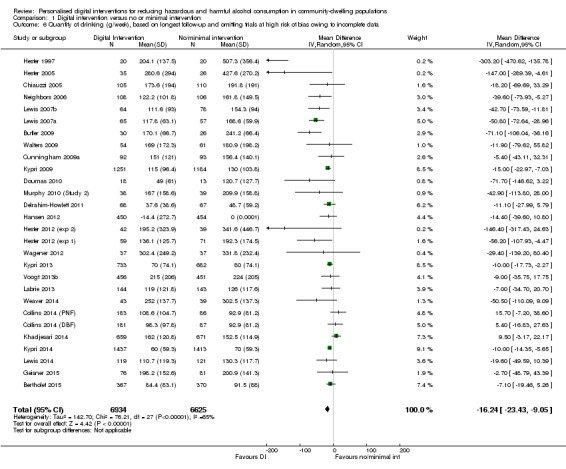

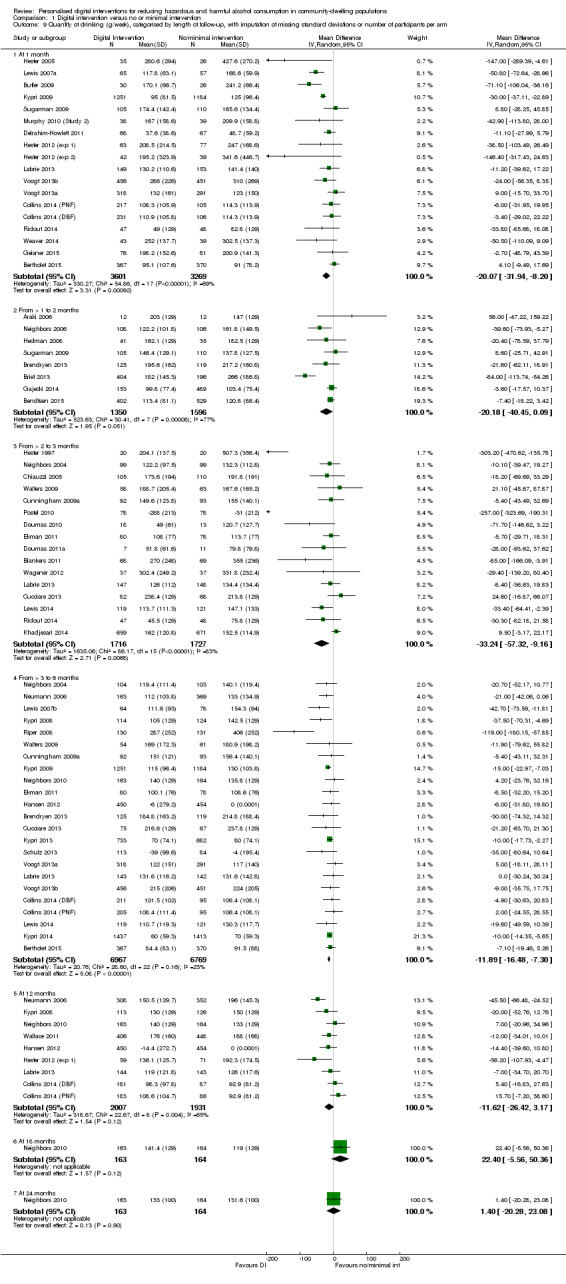

1.1 Quantity of alcohol consumed per week: primary meta‐analysis, based on longest period of follow‐up

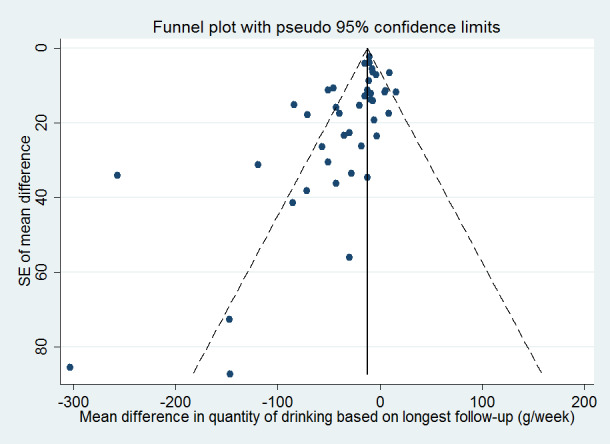

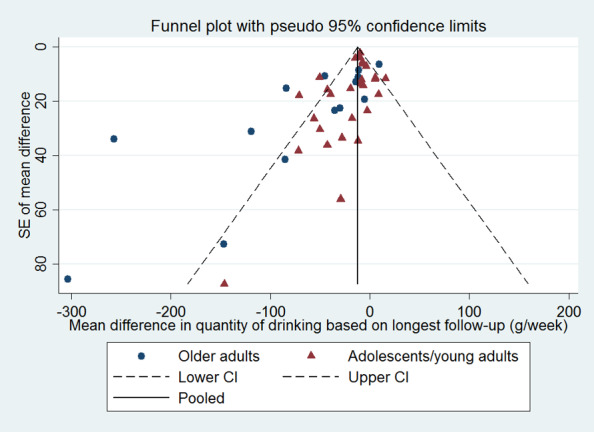

This analysis comprised data from 41 trials (42 comparisons; 1 trial comprised 2 digital intervention arms that were analysed separately). The remaining 16 trials could not be included in the primary meta‐analysis because they did not report consumption data. There was a total of 19,241 participants in these 41 trials (9631 randomised to a digital intervention, 9610 randomised to a control group). The longest period of follow‐up in these 41 trials varied from 1 to 12 months. Overall, participants who received a digital intervention drank 22.8 g (95% CI 15.4 to 30.3) of alcohol per week less than control group participants at the longest reported follow‐up point (see Analysis 1.1, Table 1). There was considerable heterogeneity in the estimate of the effect size among trials (I² = 78%), although the quantity of drinking was greater in the digital intervention arm than in the control arm in only four studies. The associated funnel plot (Figure 3) indicates some evidence of asymmetry, suggesting the possibility of under‐reporting of results with little or no evidence of an intervention effect. Meta‐regression showed that the effect size varied according to year of publication of the trial; specifically, for every year going forwards in time the mean difference in consumption between digital intervention and no or minimal intervention arms decreased by 6.3 g/week (95% CI 2.0 to 10.6). In other words, there was a smaller difference in consumption between intervention and comparison groups in more recent trials.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital intervention versus no or minimal intervention, Outcome 1 Quantity of drinking (g/week), based on longest follow‐up.

3.

Funnel plot of comparison 1: Digital intervention vs. control, outcome 1.1: Quantity of drinking (g/week), based on longest follow‐up

The trials that could not be included in the primary meta‐analysis tended to be smaller, but did not tend to be at higher risk of bias compared to those included.

1.2 Quantity of alcohol consumed per week: subgroup analyses

Intervention modality

Trials included insufficient different types of modalities (web sites, apps, etc.) to carry out a subgroup analysis.

Timing of outcomes (using follow‐up times reported in the trials)

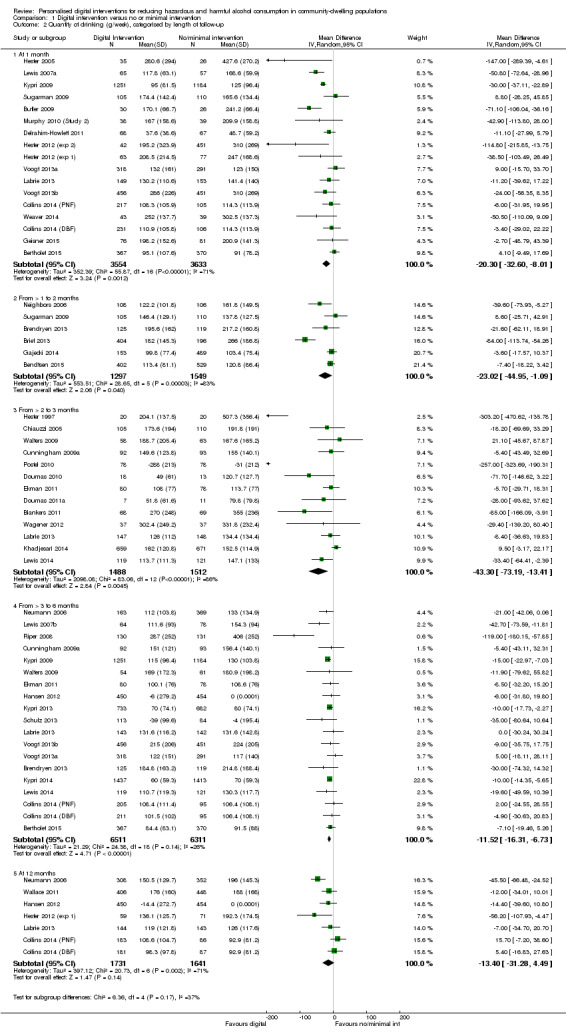

The follow‐up periods in the 41 trials in the primary meta‐analysis ranged from 1 to 12 months. Twenty‐six trials reported alcohol consumption at one time point only; and 15 trials reported these data at two or more time points. For the purpose of Analysis 1.2, follow‐up times were grouped as one month (17 comparisons, 7187 participants); more than 1 month and up to 2 months (6 studies, 2846 participants); more than two months and up to three months (13 studies, 3000 participants); more than three months and up to six months (19 comparisons, 12,822 participants); and 12 months (7 comparisons, 3372 participants). At each of these follow‐up time points, the estimated difference in consumption between digital intervention and no or minimal intervention arms was less than zero, ranging from ‐43.3 g/week (range = ‐73.2 to ‐13.4) at two to three months, to ‐11.5 g/week (range = ‐16.3 to ‐6.7) at three to six months (Analysis 1.2). At all follow‐up times other than 12 months, the difference in alcohol consumption between trial arms was significantly less than zero (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 6.36, df = 4, P = 0.17); they were not significantly different from each other.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital intervention versus no or minimal intervention, Outcome 2 Quantity of drinking (g/week), categorised by length of follow‐up.

A meta‐regression analysis of effect size on length of follow‐up could not be conducted based on data in Analysis 1.2 because some of the trials contributed to more than one follow‐up period. However, when trials were classified on the basis of their longest follow‐up using data in Analysis 1.1, the change per month of follow‐up in the difference in alcohol consumption between digital intervention and control arms was only 2.8 g/week (95% CI ‐1.0 to 6.6).

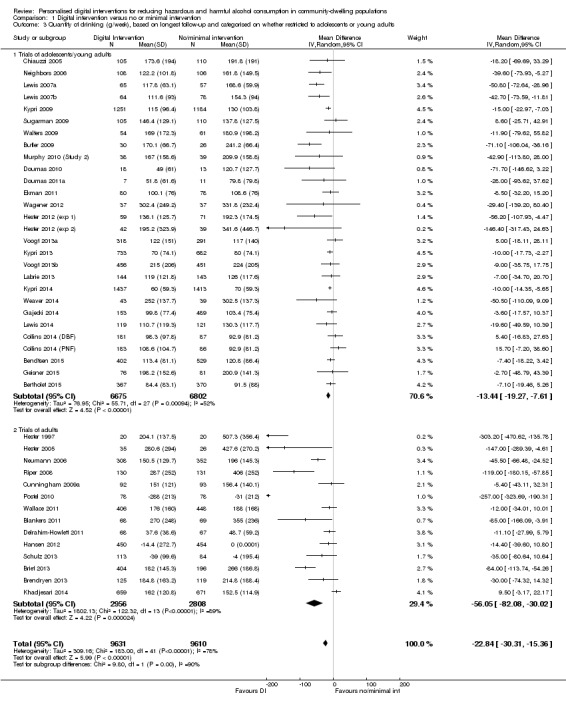

Age: trials restricted to younger people versus trials in adults

Of the 41 trials in the main meta‐analysis, 27 trials (providing 28 comparisons; one had two digital intervention arms) with 13,477 participants who were solely adolescents, young adults or college students. The age limits varied but the maximum specified age in this subgroup of trials was 29 years. Analysis 1.3 shows the results from the meta‐analysis based on the longest period of follow‐up, separately for trials restricted to younger people and those trials in adults (i.e. aged > 18 years). For adolescents or young adults, the difference between the digital intervention and no or minimal intervention arms in the quantity of alcohol consumed was smaller in magnitude than in the main analysis (‐13.4 g/week, 95% CI ‐19.3 to ‐7.6). Furthermore, this value differed significantly from the corresponding value based on 14 trials in 5764 adults (aged > 18 years) (‐56.1 g/week, 95% CI ‐82.1 to ‐30.0). The degree of heterogeneity in the effect size differed markedly between these two sets of trials: 52% for trials in adolescents and young adults and 89% for the trials in adults (aged > 18 years) (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 9.8, df = 1, P = 0.002). The associated funnel plot (Figure 4) indicated that much of the heterogeneity was associated with trials of adults (aged > 18 years).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital intervention versus no or minimal intervention, Outcome 3 Quantity of drinking (g/week), based on longest follow‐up and categorised on whether restricted to adolescents or young adults.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison 1: Digital intervention vs. control, outcome 1.6: Quantity of drinking (g/week), based on longest follow‐up and categorised on whether restricted to adolescents or young adults

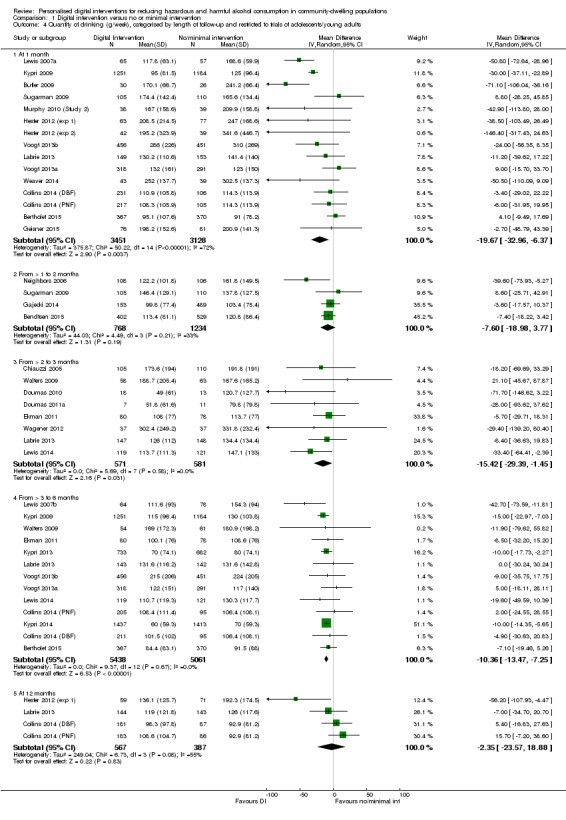

Age: trials restricted to younger people versus trials in adults, categorised by length of follow‐up

For follow‐up times of one month and three to six months, most participants in the main analysis were adolescents, young adults or college students. Estimates of the difference in alcohol consumption at these follow‐up times were similar in Analysis 1.2 and Analysis 1.4. For most follow‐up times, the difference in alcohol consumption between the digital intervention and no or minimal intervention arms was significantly less than zero, except at one to two months when this difference was ‐7.6 g/week (95% CI ‐19.0 to 3.8) and at 12 months when this difference was ‐2.4 g/week (95% CI ‐23.6 to 18.9).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital intervention versus no or minimal intervention, Outcome 4 Quantity of drinking (g/week), categorised by length of follow‐up and restricted to trials of adolescents/young adults.

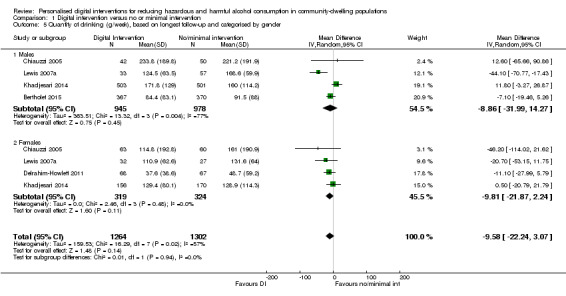

Trials restricted by gender

Only five included trials (Bertholet 2015; Chiauzzi 2005; Delrahim‐Howlett 2011; Khadjesari 2014; Lewis 2007a; 2566 participants) provided appropriate information on alcohol consumption by gender for meta‐analysis. There was no evidence from these trials that the difference in alcohol consumption between trial arms was modified by gender. Male intervention group participants drank 8.9 g/week less (95% CI ‐32.0 to 14.3) and females drank 9.8 g/week less (95% CI ‐21.9 to 2.2) (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 0.01, df = 1, P = 0.94; Analysis 1.5). However, the data available were limited, particularly for females. A further 11 trials mentioned secondary analyses by gender but did not present corresponding data; most stated they found no evidence of a differential impact of the intervention by gender.

1.5. Analysis.