Abstract

The importance of social determinants of health (SDOH) —such as affordable housing, stable employment, consistent transportation, healthy food access, and quality schools—is well-established as a key component of chronic disease prevention and health promotion. Increasingly, practitioners within and beyond public health are collaborating to implement such strategies, part of which involves measuring their impacts over time. This study assesses the current state of SDOH measurement across sectors by systematically identifying how many and what kinds of tools exist and whether there is consensus around SDOH categories and indicators selected.

This study revealed that while numerous SDOH measurement resources exist, relatively few are tools for measuring the SDOH. Although the SDOH categories being measured could be readily summarized across tools, there was wide variation in the particular SDOH categories included in each tool. Finally, remarkably little consensus exists for the specific indicators used to measure SDOH categories. While complete consensus across tools may not be possible, learning how different sectors measure SDOH and more systematically aligning SDOH categories and indicators being measured will enable greater collaboration and deepen the impacts of place-based interventions to improve community health and well-being.

Keywords: Measurement, Social determinants of health, Community development, Community health, Healthy communities, Health equity

Highlights

-

•

Growing interest exists in measuring social determinants of health (SDOH).

-

•

We aimed to understand the current state of SDOH measurement across sectors.

-

•

General consensus exists on SDOH categories included in current measurement tools.

-

•

However, there is wide variation in specific indicators with most used only once.

-

•

Collaborating beyond sectoral bounds will be critical in increasing impact.

1. Introduction

There is widespread acknowledgement that community-level social determinants—affordable housing, stable employment, reliable transportation, and access to healthy food—are a crucial component of holistic strategies to promote health, well-being, and longevity while also reducing healthcare costs. (Evans & Stoddart, 1990; Institute of Medicine, 2002; McGinnis & Foege, 1993; McGinnis, Williams-Russo, & Knickman, 2002; Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004; Kern & Friedman, 2008; Williams, Costa, Odunlami, & Mohammed, 2008). Place and neighborhoods are increasingly seen as primary drivers of social determinants of health (SDOH) (Arcaya et al., 2016; Braveman, Egerter, & Williams, 2011; Braveman & Gottlieb, 2014; Taylor et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2008) and their outcomes are spatially distributed unevenly across the U.S. (Chetty et al., 2016). With this growing awareness, practitioners within and beyond public health are coordinating efforts to implement cross-cutting interventions to improve community health and well-being (Jutte, Miller, & Erickson, 2015).

From this collaborative movement comes a proliferation of SDOH measurement tools for assessment, surveillance, and evaluation of a wide range of interventions, from individual affordable housing projects to community-level healthy eating programs. For example, public health researchers have reviewed national SDOH measurement frameworks (Koo, O’Carroll, Harris, & DeSalvo, 2016), emerging online measurement tools (Pettit & Howell, 2016), and SDOH health indicators (Lantz & Pritchard, 2010; Parrish, 2016). Additionally, the Institute of Medicine convened national experts to develop a common set of health metrics culminating in its 2015 report, “Vital Signs: Core Metrics for Health and Healthcare Progress” (Institute of Medicine, 2015). Finally, the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics' (NCVHS) —an advisory group to the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services—followed suit with its measurement framework for community health and well-being to promote multi-sector collaboration (NCVHS Population Health Subcommittee 2017).

Despite this progress, efforts to measure SDOH remain siloed across sectors. Additionally, no systematic review of SDOH measurement tools both across, and importantly, beyond public health exists. Furthermore, researchers and practitioners across sectors have not determined what the most effective indicators of community health are and how they can be applied in practice (Remington & Booske, 2011, p. 397). However, researchers continue to contend that a shared understanding of SDOH measurement is crucial in comparing health outcomes across geographic areas, monitoring progress, and ultimately advocating for investment in interventions to most effectively improve community health and well-being (Lantz & Pritchard, 2010; Remington & Booske, 2011; Aguilar-Gaxiola et al., 2014).

According to the social-ecological model of health, health behaviors like diet and levels of physical activity, among others are not simply the result of individual decisions but rather their interactions with interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy-level factors (Golden & Earp, 2012; Short & Mollborn, 2015; CDC, 2019). For the purpose of this paper, we analyze measurement tools focused specifically on community-level, place-based SDOH. The Healthy People 2020 national framework provides a starting point for our definition of SDOH, which includes the following five categories and associated sub-categories (Office of Disease Prevention and Promotion 2018):

-

•

Economic stability (subcategories: employment, food insecurity, housing stability, poverty)

-

•

Education (subcategories: early childhood education, enrollment in higher education, high school graduation, language and literacy)

-

•

Health and healthcare (subcategories: access to healthcare, access to primary care, health literacy)

-

•

Neighborhood and built environment (subcategories: access to healthy foods, crime and violence, environmental conditions, housing quality), and

-

•

Social and community context (subcategories: civic participation, discrimination, incarceration, social cohesion).

This study expands upon existing research to provide a systematic summary of SDOH measurement tools and explores whether there is consensus around SDOH categories measured and indicators used. We do this by asking the following research questions:

-

1)

How many SDOH measurement tools exist?

-

2)

What sectors do SDOH measurement tools span?

-

3)

What categories of social determinants do SDOH measurement tools encompass?

-

4)

What specific indicators are included in SDOH measurement tools?

-

5)

How much consensus exists around SDOH categories and indicators?

2. Methods

We identified SDOH measurement tools for comparison through a comprehensive, iterative review of national frameworks, publicly available validated tools and indices, websites of major national organizations representing the sectors of interest, bibliographies of published papers, and practitioner-focused white papers/gray literature.

2.1. Search strategy

Primary data sources included PubMed, EBSCO Host, ProQuest, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sources for Data on Social Determinants of Health. Because many of the most recent measurement tools have not yet been published widely in academic literature, a systematic web search was conducted using internet search engines. Initially the search terms “social determinants of health” and “health equity” were used with one or more of the following keywords: “indicators”, “measurement”, “metrics”, “healthy communities,” “community development,” “planning,” and “public health.” The wider web search identified additional keywords such as: “community health needs assessments,” “health impact assessments,” “community needs index,” “economic index,” and “opportunity index”. Relevant professional websites, reports, and gray literature, and associated bibliographies were also reviewed. Additionally, a volunteer advisory panel of experts spanning community development, finance, philanthropy, public health, and healthcare was recruited to provide guidance on SDOH data and measurement resources at all stages of the data collection process.

2.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

To determine how many SDOH measurement tools exist (research question 1) we screened measurement resources (e.g., databases and non-profit measurement consulting organizations) for tools that make SDOH data useable such as mapping tools, indices, and/or ranking systems. We reviewed tools that met the following inclusion criteria: 1) explicitly includes “health” and social determinants of health indicators and metrics, 2) incorporates data that can be disaggregated for a geographic area smaller than the state or national level, e.g. by census tract, county, or Metropolitan Statistical Area, and 3) are based on publicly available, validated databases either developed or updated during the past decade. We excluded tools that: 1) incorporated only medically-focused health indicators (e.g. diagnoses, health behaviors, disease rates), 2) are no longer actively used or updated, and/or 3) required payment to access proprietary resources.

2.3. Exploring sectors and categorizing SDOH categories and indicators

To identify what sectors the SDOH measurement tools span (research question 2), we scanned and documented any specific mention of user or practitioner type and analyzed keywords to cluster them into larger general categories, taking special note of any mention of “social determinants of health” and/or “health”.

To determine the SDOH categories that measurement tools encompassed (research question 3), we listed each tool's categories and compared them to the following 12 categories adapted from the Healthy People 2020 Approach to Social Determinants of Health Framework (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2018):

-

1.

Demographics

-

2.

Economic Stability

-

3.

Employment

-

4.

Education

-

5.

Food Environment

-

6.

Health and Healthcare

-

7.

Housing

-

8.

Neighborhood and Built Environment

-

9.

Physical Activity and Lifestyle

-

10.

Safety

-

11.

Social and Community Context

-

12.

Transportation and Infrastructure

Although demographics were not part of the Healthy People 2020 framework, we felt it was a necessary addition given the growing body of research on the connections between community–level health and demographic characteristics (Gresenz, Rogowski, & Escarce, 2009; Tucker et al., 2018). Communities and neighborhoods vary dramatically by demographic variables, such as the proportion of races, mean and median age, average household income, rate of homeownership, and educational attainment rates. Because this project's purpose was to examine differences in how determinants of health are measured across tools, we wanted to also understand the extent to which demographics were either included or not included.

To determine what specific indicators were included within individual measurement tools (research question 4), we listed all indicators for each tool and compared across tools to create a master list. This master list served as a checklist for tallying indicators for each measurement tool. In some cases similar indicators were defined differently or varied in their level of specificity (e.g., “race/ethnicity” vs “population by race/ethnicity” vs “detailed race/ethnicity”). If indicators were not an exact text match, we included all variations as distinct indicators. We also consolidated any indicators that were categorically the same but differed in wording (e.g., unemployed” and “unemployment” and “no health insurance” and “uninsured”).

Finally, to determine how much consensus exists across SDOH categories and indicators (research question 5), we used our tally of SDOH categories and indicators to explore patterns across tools and sectors.

3. Results

3.1. Number of SDOH measurement tools (RQ1)

To answer research question 1 (“how many SDOH measurement tools exist ?”) the search described above yielded 65 resources as possible SDOH measurement tools. Of those, 7 were identified through literature review, 33 through an extensive web search, and 25 through consultation with the volunteer panel of experts.

After screening the initial measurement resources list, 47 did not meet inclusion criteria and were eliminated. Most of these excluded resources were databases rather than measurement tools or were developed by proprietary sources. For example, the SocioNeeds Indices were developed and customized for a number of individual healthcare systems by private firm Conduent Healthy Communities Institute (See Appendix A for a full list of excluded resources). Through this process, 18 (28%) of the 65 screened measurement resources met our inclusion criteria as SDOH measurement tools and were analyzed accordingly. Nearly two-thirds (61%) of the tools were developed in the last five years.

3.2. Sectors spanning measurement tools (RQ2)

To answer research question 2 (“what sectors do SDOH measurement tools span?”), we scanned websites hosting the 18 tools that met our research criteria for any information about their intended users and sectors. We found that SDOH measurement tools were developed by and for a broad range of organizations including government, philanthropic organizations, non-profit banks, public health non-profits, academic research institutes, and others. We determined that SDOH measurement tools span three broad categories [See Table 1]:

-

•

Health: Tools created for the purposes of surveillance and needs assessment primarily by public health departments and research entities. Two of these tools were created with non-profit hospitals in mind given their requirement to conduct community health needs assessments every three years to maintain tax-exempt status (Association of State and Territorial Health Organizations, 2019).

-

•

Built environment: Tools created largely for the purposes of neighborhood-level needs assessment and evaluation spanning urban planning, community development, economic development, and public policy.

-

•

Cross-sectoral: Tools intentionally spanning the above categories typically combining both health and built environment data for the purposes of needs assessment, surveillance, and/or evaluation.

Table 1.

List of SDOH measurement tools by sector (n = 18).

Overall, nearly half of the tools (44%, n = 8) were cross-sectoral. A case in point is the Child Opportunity Index, which fosters collaboration between health policymakers and community development organizations (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2014). One third of the tools (33%, n = 6) focused on built environment sectors (e.g., community development, housing, economic development, transportation, government, planning). These built environment-related tools typically included place-based indicators (e.g., housing stability) rather than medically-focused indicators (e.g., obesity). Finally, less than a quarter of tools (22%, n = 4) primarily focused on health. These tools were intended for community health needs assessments or included primarily medically-focused indicators such as health behaviors and clinical outcomes.

3.3. Social determinants categories included in SDOH measurement tools (RQ3)

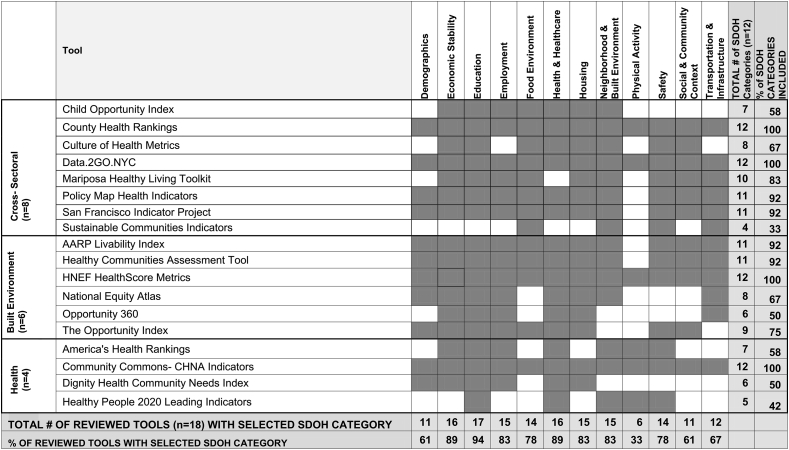

To answer research question 3 (“what categories of social determinants do SDOH measurement tools encompass?”), we compared each SDOH measurement tool's categories against the 12 adapted Healthy People 2020 SDOH categories noted earlier. Table 2 summarizes the presence of the 12 SDOH categories within each of the 18 tools (horizontal rows) and across the 18 tools (vertical columns). SDOH categories included within each tool are highlighted in dark gray. The total number and percentages of tools including each individual SDOH category (bottom row) and the total number and percentages of the 12 SDOH categories within each tool (far right column) are highlighted in light gray.

Table 2.

Adapted Healthy People 2020 SDOH categories within each SDOH measurement tool examined.

SDOH categories included within each tool are highlighted in dark gray. Subtotals of the number of SDOH categories across and within tools are highlighted in light gray.

Our analysis revealed that less than a quarter of the 18 tools (n = 4, 22%) incorporated all 12 of the adapted Healthy People 2020 SDOH categories. These tools were Community Commons' Community Health Needs Assessment Indicators (public health), County Health Rankings & Data2Go.NYC (cross-sectoral), and HNEF HealthScore Metrics (built environment). Several tools did not include half or more of the 12 SDOH categories (see Table 2). The least likely SDOH categories to be present in tools included: social and community context (n = 7, 39%), transportation/infrastructure (n = 6, 33%), food environment (n = 5, n = 28%), and safety (n = 4, 22%).

Health tools encompassed the fewest number of 12 SDOH categories (a mean of 7.5 categories) compared to cross-sectoral and built environment tools, with a mean of 9.4 and 9.5 categories, respectively. Over 60% of the cross-sectoral tools included 10 or more SDOH categories, compared to 50% of built environment tools and 25% of the health tools.

3.4. Indicators included in SDOH measurement tools (RQ4)

To answer research question 4 (“what specific indicators are included in SDOH measurement tools?”), we tallied specific SDOH indicators within each tool and determined that there was a total of 676 distinct indicators.

Of these indicators, 75% (n = 509) were used in only a single SDOH measurement tool. Within SDOH categories, the “Health & Healthcare” category had the most unique indicators used only once. Examples include: “long commute driving alone,” “feel safe alone at night”, “adult persistent sadness,” “school proximity to traffic”, and “seat belt use.” PolicyMap's Health Indicators tool and Data2Go.NYC had the most unique indicators not found in any other tools (n = 193 and 175, respectively). See Appendix B for a sample of unique indicators within each SDOH measurement tool.

3.5. Consensus around social determinants categories and indicators across measurement tools (RQ5)

To answer research question 5, (“how much consensus exists around SDOH categories and indicators?”), we analyzed how many and which SDOH categories and indicators were frequently used across all SDOH measurement tools. Overall, there was general consensus regarding the SDOH categories but little consistency of indicators.

The most frequently used SDOH category, Education, was included in all but one SDOH measurement tool (see Table 2, vertical columns). Economic Stability and Health & Healthcare were included in nearly 90% (n = 16) of the tools. The SDOH categories of Employment, Housing, and Neighborhood & Built Environment also reached a high level of consensus across tools, included in 83% of those examined.

The least consensus existed for the SDOH category of Physical Activity, present in only six (33%) of the SDOH tools examined. The SDOH categories of Social & Community Context and Transportation & Infrastructure were found in only 61% and 66% of the tools, respectively.

In contrast, there was essentially no consensus on the indicators used to measure the broader SDOH categories. Rather, as noted in the previous section, the majority of indicators (75%) appeared only once. Across tools, the widest variety of indicators (41% of the total) was found in the SDOH categories of Health/Healthcare and Neighborhood/Built Environment with 182 and 94 different indicators, respectively, for just those two social determinants alone. The least used SDOH category, Physical Activity, also had the fewest number of associated indicators with only four, or 0.6% of the total.

Even the most frequently used single indicator, unemployment, was present in just over 60% (n = 11) of SDOH measurement tools. The indicators of obesity, poverty, and income inequality were the next most common single indicators, each of which were included in only half (n = 9) of all the tools reviewed.

Table 3 lists the most commonly used indicators within each sector. Within health and built environment tools, there was modest consensus with a handful of indicators used in half the tools of that type, but very few individual indicators used in more than 50% of the tools. Among the eight cross-sectoral SDOH measurement tools examined, only three indicators – poverty, income inequality, and air quality – were used in half the tools, with no indicator present in more than half.

Table 3.

Summary of Most Frequently Used Indicators In 50% or more Tools Within Sectors.

| Sector | Indicators Included In >50% of tools | Indicators Included in 50% of tools |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Sectoral (n = 8) | None | poverty, income inequality, air quality (used in 4 tools) |

| Built Environment (n = 6) | income inequality, poverty, overweight/obese (used in ≥4 tools) | associate's degree or higher, traffic injuries, violent crime, diabetes, unemployment, median household income, commute time, household transportation costs (used in 3 tools) |

| Health (n = 4) | child poverty, unemployment, overweight/obese, infant mortality, smoker, dental visit, annual routine, no health insurance (used in ≥3 tools) | physical inactivity, median household income, suicide, preventable hospitalizations, heart disease, diabetes, binge drinking, vegetable intake, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, adolescent smoker, hypertension monitoring, diabetes monitoring, immunizations- children, knowledge of HIV status, dentists, usual primary care provider, violent crime, injury deaths, high school graduation (used in 2 tools) |

4. Discussion

This study systematically identified and explored the growing number of SDOH measurement resources across sectors to better understand the current state of SDOH measurement. While numerous SDOH measurement resources exist, relatively few constitute tools for measuring the SDOH. Additionally, sectors beyond health are now widely engaged in both measuring and addressing SDOH, namely built environment-related sectors such as urban planning and community development. Although the SDOH categories being measured could be readily summarized across tools, there was wide variation in the particular SDOH categories included in each tool. Finally, remarkably little consensus exists for specific indicators used to measure SDOH categories.

The large number of SDOH measurement resources confirms extensive interest in this topic, however it is notable that only a third of those resources met our criteria as SDOH measurement tools. This suggests a need to consolidate the most useful tools so that they are easily accessible across sectors. For example, MeasureUp is a curated online portal of tools hosted by Build Healthy Places Network to measure the health value of place-based, community development initiatives which marks progress on this front (Build Healthy Places Network, 2019).

Given the focus on measuring health, it is perhaps surprising that a substantial number of the identified tools arose from organizations beyond health. For example, Enterprise Community Partners, a national, non-profit community development financial institution (CDFI), developed a comprehensive online SDOH measurement tool, Opportunity360, which in the past would likely have come from a public health organization. Of note, nearly half of the tools examined were explicitly cross-sectoral and fully half of the tools were created in the past five years, including nearly all categorized as having a built environment focus.

These findings suggest that built environment sectors such as urban planning and community development are now actively thinking about health, its measurement, and the value of improved health and reduced costs as part of their business and strategic planning. It also suggests that traditional health researchers and practitioners should be aware of SDOH measurement tools beyond health. One example is the portfolio of Success Measures' Health Tools. Developed by NeighborWorks America and released in December 2017, the portfolio encompasses 65 tools spanning surveys, interview guides, observation protocols, and templates to collect primary data assessing the health impacts of a variety of place-based initiatives such as grocery store development, affordable housing, and social service programs.

Using an adapted Healthy People 2020 framework, we found that the social determinants within measurement tools could be readily categorized into a relatively succinct 12 groups. However, fewer than one in four of the SDOH measurement tools incorporated all 12 SDOH categories, with Physical Activity and Social & Community Context most likely to be excluded. Notably, one third of the tools were missing over half of the SDOH categories. Additionally, cross-sectoral tools and more recently created tools were found to include the most SDOH categories, suggesting growing recognition of the complexity of SDOH and a need to be comprehensive and cross-sectoral when evaluating them.

Despite a moderate agreement around SDOH categories, there was very little consensus on the indicators used to assess specific SDOH. Rather, nearly 700 distinct indicators were identified with a substantial majority used in only a single tool. While the SDOH category of Education was used by 17 of the 18 SDOH measurement tools, no one indicator or set of indicators dominated. Even the most frequently used indicators – unemployment, income inequality, poverty, and overweight/obese – were used in just over half of SDOH measurement tools. These findings highlight a critically important need to determine which indicators are most effective at measuring the SDOH they are intended to capture.

While complete consensus on indicators across sectors and tools is unlikely – and perhaps not even desirable – a near complete lack of agreement makes it difficult to compare findings. Fortunately, the sheer number of indicators across these tools makes it likely that high quality measures are already in use. As our list of sample unique indicators suggests (Appendix B), future researchers developing measurement tools could find value in looking more widely across sectors to identify novel indicators for use.

A key limitation of this study is that no common catalog exists to guide the search for cross-sectoral measurement tools focused on social determinants. Much of this work has taken place within the last few years, so there has been relatively little peer-reviewed research completed or published. As a result, our survey of tools necessitated reliance on internet searches and input from an expert panel. As a result, risk of missing eligible tools remains.

There were also limitations related to the types of tools identified. First, there were far more cross-sectoral and built environment-related tools identified and analyzed (14 of 18 tools, 78%). This likely influenced findings about the overall patterns of SDOH categories and indicators used across tools (e.g., education as the most common determinant category and unemployment as the most frequently used indicator). Second, a few SDOH measurement tools analyzed incorporated indicators used in other tools, resulting in some double counting of indicators. For example, the Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicators are incorporated into County Health Rankings. Despite these limitations, this review provides a starting point for improving understandings of the similarities and differences in prioritizing social determinants of health metrics across sectors.

In conclusion, this study confirms that a wide range of SDOH measurement tools exist across sectors to assess community needs, track progress, evaluate impact and/or plan new projects. Our findings also suggest that while a single shared measurement system to meet cross-sectoral needs may not be possible or even practical, there is still much to be gained from understanding the most and least frequently used SDOH categories and indicators across sectors. This can serve as a starting point for conversations about consensus building either as part of efforts to align or share measurement strategies, or to broaden understandings of how social determinants of health are defined and implemented across different sectors and how they might address different needs. For example, the more commonly shared indicators of unemployment, poverty, or income inequality could be an easy way for practitioners to find common ground. Moving forward, more work needs to be done to share and learn from measurement strategies to advance cross-sector efforts to build healthier communities. We hope that this comprehensive summary of SDOH measurement tools, many of which may be unfamiliar to siloed researchers or practitioners, will provide one step in this direction to continue to speed cross-sectoral collaboration.

Ethics approval statement

This research did not require ethics approval because it did not involve data collected from human subjects.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100395.

Contributor Information

Renee Roy Elias, Email: krroy@berkeley.edu.

Douglas P. Jutte, Email: djutte@buildhealthyplaces.org.

Alison Moore, Email: alison@dyettandbhatia.com.

Appendix A. Excluded Measurement Resources

| Measurement Resources | Year Created | Creators/Funders | Reason for Elimination |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 Million Healthier Lives- Measure What Matters | 2015 | Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | NR |

| 500 Cities Project | 2016 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | NR |

| All-In: Data for Community Health | 2017 | AcademyHealth, Data Across Sectors for Health, The BUILD Health Challenge | NR |

| Be Healthy RVA | 2016 | Bon Secours Richmond Health System, Commonwealth Catholic Charities, Envera, VCU Health, Virginia Department of Health, and the Greater Richmond YMCA | P |

| California Department of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley | 2010 | California Dept of Public Health, UC Berkeley | NS |

| CDC Health Impact Assessment Framework | 2016 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | NS |

| Cumberland/Salem Health and Wellness Alliance | 2010 | Cumberland Salem Health and Wellness Alliance | P |

| Data Across Sectors for Health (DASH) | 2014 | RWJF, Illinois Public Health Institute, Michigan Public Health Institute | NR |

| Dataset Directory of SDOH at the Local Level (CDC) | 2004 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | NA |

| DC Health Matters | 2012 | DC Healthy Communities Collaborative | P |

| Delaware Health Tracker | 2012 | Delaware Healthcare Association | P |

| Equitable Development Toolkit | 2014 | PolicyLink | NR |

| Gallup Well-Being Index | 2012 | Gallup, Sharecare | NR |

| Health Impact Project | 2009 | Pew Charitable Trusts, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | NT |

| Health Matters in Douglas County, Nebraska | 2015 | Live Well Omaha | P |

| Healthy Paso Del Norte | 2012 | Lenoir Memorial | P |

| Keys to Health | 2018 | Population Health Collaborative of Western NY | P |

| Lenoir Memorial Hospital SocioNeeds Index | 2017 | Lenoir Memorial | P |

| Lima-Allen County Regional Planning Commission SocioNeeds Index | 2017 | Lima-Allen County Regional Planning Commission | P |

| Low Income Investment Fund Social Impact Calculator | 2014 | Low Income Investment Fund | NS |

| Metrics for Healthy Communities | 2015 | Wilder Research, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Build Healthy Places Network, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | NS |

| Municipal Health Data for American Cities Initiative | 2018 | Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, New York University | NR |

| National Environmental Database (companion resource to 500 Cities) | 2017 | Urban Design 4 Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | NR |

| National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership | 1996 | Urban Institute, local partners | NR |

| National Prevention Strategy | 2011 | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | NS |

| North Country Health Compass | 2013 | North Country Health Compass Partners | P |

| Orange County's Healthier Together | 2014 | Orange County Healthier Together | P |

| Parkview Health SocioNeeds Index | 2017 | Parkview Health | P |

| PGC HealthZone | 2017 | Prince George's County Health Department | P |

| Piedmont Health Counts | 2017 | Guilford and Alamance County Community Assessment Team | P |

| Plymouth and Norfolk Counties Health Compass | 2016 | Blue Hills Community Alliance | P |

| Scott Memorial SocioNeeds Index | 2017 | Scott Memorial | P |

| Sinai Community Health SocioNeeds Index | 2017 | LifeBridge Health | P |

| SSM Health SocioNeeds Index | 2017 | SM Health | P |

| St. Charles Health System SocioNeeds Index | 2017 | St. Charles Health | P |

| State of Place | 2017 | State of Place | NS |

| Stewards for Affordable Housing For the Future Common Outcome Measures | 2013 | Stewards for Affordable Housing for the Future | NS |

| Success Measures Health Tools | 2004 | NeighborWorks America | NR |

| Sustainable Measures | 2014 | Maureen Hart (consultant) | NA |

| The Way To Wellville | 2014 | Health Initiative Coordinating Council (HICCup); Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | NR |

| THRIVE- Community Tool for Health & Resilience in Vulnerable Environments | 2012 | US Office of Minority Health, California Endowment, National Network of Public Health Institutes (NNPHI) and Prevention Institute | F |

| Urban Land Institute Building Healthy Places Toolkit | 2015 | Urban Land Institute | NS |

| Vita Stamford Impact Grid | 2014 | Charter Oaks Communities, Stamford Hospital | NS |

| Vital Signs: Core Metrics and Healthcare Progress | 2015 | Institute of Medicine | NS |

| What Works Cities | 2015 | Bloomburg Philanthropies | NR |

P = data/tool is proprietary.

NR = is a framework, program or database and/or does not provide recommended or specific indicators.

NA = not active.

NS = does not focus on social determinants of health indicators identified in HP2020.

Appendix B. Selected “Unique Indicators” Used Once Across All SDOH Measurement Tools

| Sector | Associated Tool | Sample Unique Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Sectoral (n = 8) | Child Opportunity Index | quality early childhood education centers |

| County Health Rankings | long-commute driving alone | |

| Culture of Health Metrics | social spending relative to health expenditures | |

| Data2Go.NYC | child stability (children in same house 1 year ago) | |

| Mariposa Healthy Living Toolkit | feel safe alone at night | |

| PolicyMap Health Indicators | CDFI investments | |

| San Francisco Indicator Project | community garden access | |

| Sustainable Communities Health Indicators | bike parking per capita | |

| Built Environment (n = 6) | AARP Livability Index | social involvement index |

| Healthy Communities Assessment Tool | school proximity to traffic | |

| HNEF HealthScore | environmental justice location | |

| National Equity Atlas | income gains with racial equity | |

| Opportunity 360 | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | |

| The Opportunity Index | doctors per 100,000 people | |

| Health (n = 4) | America's Health Rankings | seat belt use |

| Community Commons- CHNA Indicators | soda expenditures | |

| Dignity Health Community Needs Index | below poverty line, single female-headed household w/children <18 | |

| Healthy People 2020 Leading Indicators | adolescents with depressive episodes |

Appendix C. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D., McArdle N., Hardy E.F., Crisan U.I., Romano B., Norris D.…Reece J. The child opportunity index: Improving collaboration between community development and public health. Health Affairs. 2014;33(11):1948–1957. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Gaxiola S., Ahmed S., Franco Z., Kissack A., Gabriel D., Hurd T.…Wallerstein N. Towards a unified taxonomy of health indicators: academic health centers and communities working together to improve population health. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014;89(4):564–572. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcaya M.C., Tucker-Seeley R.D., Kim R., Schnake-Mahl A., So M., Subramanian S.V. Research on neighborhood effects on health in the United States: A systematic review of study characteristics. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;168:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of State and Territorial Health Organizations . 2019. Clinical to community connections: Community health needs assessments.http://astho.org/programs/access/community-health-needs-assessments/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P., Egerter S., Williams D.R. The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health. 2011;32(1):381–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P., Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: It's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports. 2014;129(1_suppl2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Build Healthy Places Network . 2019. MeasureUp.https://buildhealthyplaces.org/measureup/ [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2019. Violence prevention: The social ecological model.https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/social-ecologicalmodel.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R., Stepner M., Abraham S., Lin S., Scuderi B., Turner N. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2016;315(16):1750–1766. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R.G., Stoddart G.L. Producing health, consuming health care. Social Science & Medicine. 1990;31(12):1347–1363. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden S.D., Earp J.L. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Education & Behavior. 2012;39(3):364–372. doi: 10.1177/1090198111418634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresenz C.R., Rogowski J., Escarce J.J. Community demographics and access to health care among U.S. Hispanics. Health Services Research. 2009;44(5):1542–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press (US); Washington, DC: 2002. The future of the public's health in the 21st century.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221239/ Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press (U.S.); Washington, DC: 2015. Vital Signs: Core metrics for health and healthcare progress.https://www.nap.edu/catalog/19402/vital-signs-core-metrics-for-health-and-health-care-progress Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutte D.P., Miller J.L., Erickson D.J. Neighborhood adversity, child health, and the role for community development. Pediatrics. 2015;135(Supplement 2):S48–S57. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3549F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern M.L., Friedman H.S. Early educational milestones as predictors of lifelong academic achievement, midlife adjustment, and longevity. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;30(4):419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo D., O'Carroll P.W., Harris A., DeSalvo K.B. An environmental scan of recent initiatives incorporating social determinants in public health. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2016;13:E86. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz P.M., Pritchard A. Socioeconomic indicators that matter for population health. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2010;7(4) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2901572/ Retrieved from. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis J.M., Foege W.H. Actual causes of death in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270(18):2207–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis J.M., Williams-Russo P., Knickman J.R. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Affairs. 2002;21(2):78–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad A.H., Marks J.S., Stroup D.F., Gerberding J.L. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics Population Health Subcommittee . 2017. NCVHS measurement framework for community health and well-being v4.https://ncvhs.hhs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/NCVHS-Measurement-Framework-V4-Jan-12-2017-for-posting-FINAL.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . 2018. Healthy People 2020: Social determinants of health.https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health [Google Scholar]

- Parrish R.G. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. Environmental Scan of existing Domains and Indicators to inform Development of a new measurement Framework for Assessing the Health and Vitality of communities (conducted for the national committee on vital and health Statistics) [Google Scholar]

- Pettit K., Howell B. Urban Institute; 2016. Assessing the landscape of online health and community indicator platforms.https://www.urban.org/research/publication/assessing-landscape-online-health-and-community-indicator-platforms [Google Scholar]

- Remington P.L., Booske B.C. Measuring the health of communities—how and why? Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2011;17(5):397–400. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318222b897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short S.E., Mollborn S. Social determinants and health behaviors: Conceptual frames and empirical advances. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;5 doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.05.002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4511598/ 78-64. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L.A., Tan A.X., Coyle C.E., Ndumele C., Rogan E., Canavan M. Leveraging the social determinants of health: What works? PLoS One. 2016;11(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker C.M., Smith T.M., Hoga M.L., Banzhaf M., Molina N., Rodriquez B. Current demographics and roles of community health workers: Implications for recruitment and training. Journal of Community Health. 2018;43(3):552–559. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Costa M.V., Odunlami A.O., Mohammed S.A. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice: JPHMP. 2008;14(Suppl):S8–S17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.