Abstract

Background

Pain is a common feature of childhood and adolescence around the world, and for many young people, that pain is chronic. The World Health Organization guidelines for pharmacological treatments for children's persisting pain acknowledge that pain in children is a major public health concern of high significance in most parts of the world. While in the past, pain was largely dismissed and was frequently left untreated, views on children's pain have changed over time, and relief of pain is now seen as important.

We designed a suite of seven reviews on chronic non‐cancer pain and cancer pain (looking at antidepressants, antiepileptic drugs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, opioids, and paracetamol as priority areas) in order to review the evidence for children's pain utilising pharmacological interventions in children and adolescents.

As the leading cause of morbidity in children and adolescents in the world today, chronic disease (and its associated pain) is a major health concern. Chronic pain (lasting three months or longer) can arise in the paediatric population in a variety of pathophysiological classifications: nociceptive, neuropathic, idiopathic, visceral, nerve damage pain, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and chronic abdominal pain, and other unknown reasons.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is one of the most widely used analgesics in both adults and children. The recommended dosage in the UK, Europe, Australia, and the USA for children and adolescents is generally 10 to 15 mg/kg every four to six hours, with specific age ranges from 60 mg (6 to 12 months old) up to 500 to 1000 mg (over 12 years old). Paracetamol is the only recommended analgesic for children under 3 months of age. Paracetamol has been proven to be safe in appropriate and controlled dosages, however potential adverse effects of paracetamol if overdosed or overused in children include liver and kidney failure.

Objectives

To assess the analgesic efficacy and adverse events of paracetamol (acetaminophen) used to treat chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents aged between birth and 17 years, in any setting.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online, MEDLINE via Ovid, and Embase via Ovid from inception to 6 September 2016. We also searched the reference lists of retrieved studies and reviews, and searched online clinical trial registries.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, with or without blinding, of any dose and any route, treating chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents, comparing paracetamol with placebo or an active comparator.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed studies for eligibility. We planned to use dichotomous data to calculate risk ratio and numbers needed to treat, using standard methods where data were available. We planned to assess GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) and create a 'Summary of findings' table.

Main results

No studies were eligible for inclusion in this review.

There is no evidence to support or refute the use of paracetamol for children with chronic non‐cancer pain.

Authors' conclusions

There is no evidence from randomised controlled trials to support or refute the use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) to treat chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents. We are unable to comment about efficacy or harm from the use of paracetamol to treat chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents.

We know from adult randomised controlled trials that paracetamol can be effective, in certain doses, and in certain pain conditions (not always chronic).

Plain language summary

Paracetamol for chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents

Bottom line

There is no evidence from randomised controlled trials to support or refute the suggestion that paracetamol (acetaminophen) in any dose will provide pain relief for chronic non‐cancer pain in children or adolescents.

Background

Children can experience chronic or recurrent pain related to genetic conditions, nerve damage pain, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and chronic abdominal pain, as well as for other unknown reasons. Chronic pain is pain that lasts three months or longer and is commonly accompanied by changes in lifestyle, functional abilities, as well as by signs and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is one of the most widely used painkillers in both adults and children. The recommended dosage in the UK, Europe, Australia, and the USA for children and adolescents is generally 10 to 15 mg/kg every four to six hours, with specific age ranges from 60 mg (6 to 12 months old) up to 500 to 1000 mg (over 12 years old). Paracetamol is the only recommended painkiller for children under 3 months of age. Paracetamol has been proven to be safe in appropriate and controlled dosages, however potential side effects of paracetamol if overdosed or overused in children include liver and kidney failure.

Key results

In September 2016 we searched for clinical trials where paracetamol was used to treat chronic pain (potentially from either nerve pain, musculoskeletal problems, menstrual cramps, or abdominal discomfort).

We found no studies that met the requirements for this review. Several studies tested paracetamol on adults with chronic pain, but none included participants from birth to 17 years old.

Quality of the evidence

We planned to rate the quality of the evidence from studies using four levels: very low, low, moderate, or high. Very low quality evidence means that we are very uncertain about the results. High quality evidence means that we are very confident in the results.

We were unable to rate the quality of the body of evidence as there was no evidence to support or refute the use of paracetamol for chronic non‐cancer pain in children or adolescents.

Background

Pain is a common feature of childhood and adolescence around the world, and for many young people, that pain is chronic. The World Health Organization guidelines for pharmacological treatments for persisting pain in children acknowledge that pain in children is a major public health concern of high significance in most parts of the world (WHO 2012). While in the past, pain was largely dismissed and was frequently left untreated, views on children's pain have changed over time, and relief of pain is now seen as important. Since the 1970s, studies comparing child and adult pain management have revealed a variety of responses to pain, fuelling the need for a more in‐depth focus on paediatric pain (Caes 2016).

Infants (zero to 12 months), children (1 to 9 years), and adolescents (10 to 18 years) (WHO 2012), account for 27% (1.9 billion) of the world's population (United Nations 2015); the proportion of those aged 14 years and under ranges from 12% (in Hong Kong) to 50% (in Niger) (World Bank 2014). However, little is known about the pain management needs of this population. For example, in the Cochrane Library, approximately 12 reviews produced by the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group in the past 18 years have been specifically concerned with children and adolescents, compared to over 100 reviews specific to adults. Additional motivating factors for investigating children's pain include the vast amount of unmanaged pain in the paediatric population and the development of new technologies and treatments. We convened an international group of leaders in paediatric pain to design a suite of seven reviews in chronic pain and cancer pain (looking at antidepressants, antiepileptic drugs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, opioids, and paracetamol as priority areas) in order to review the evidence under a programme grant for children's pain utilising pharmacological interventions in children and adolescents (Appendix 1).

This review is based on a template for reviews of pharmacotherapies used to relieve pain in infants, children, and adolescents. The aim is for all reviews to use the same methods, based on new criteria for what constitutes reliable evidence (Appendix 2) (Moore 2010a; Moore 2012). This review focused on paracetamol (acetaminophen) to treat chronic non‐cancer pain.

Description of the condition

This review focused on chronic non‐cancer pain experienced by children and adolescents as a result of any type of chronic disease that occurs throughout the global paediatric population. Children's level of pain can be mild, moderate, or severe, and pain management is an essential element of patient management during all care stages of chronic disease.

As the leading cause of morbidity in children and adolescents in the world today, chronic disease (and its associated pain) is a major health concern. Chronic pain can arise in the paediatric population in a variety of pathophysiological classifications: nociceptive, neuropathic, idiopathic, or visceral. Chronic pain is pain that lasts three months or longer and is commonly accompanied by changes in lifestyle, functional abilities, as well as by signs and symptoms of depression and anxiety (Ripamonti 2008).

Whilst diagnostic and perioperative procedures performed to treat chronic diseases are a known common cause of pain in these patients, this review did not cover perioperative pain or adverse effects of treatments such as mucositis.

Description of the intervention

Paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) is one of the most widely used analgesics around the world in both the adult and paediatric populations. First marketed in the USA and UK in the 1950s, paracetamol is now recommended in all healthcare setting guidelines as the first‐line analgesic for both adults and children experiencing mild to moderate pain (NICE 2016). Paracetamol is currently available in most countries in healthcare settings and can be accessed without prescription (WHO 2012).

The recommended dosage for paediatric patients under 18 years old is generally 10 to 15 mg/kg (BNF 2016; FDA 2017; TGA 2017). For adolescents (12 years and older) recommended doses are 500 to 1000 mg oral tablet or liquid formula (via rectum if necessary), at a frequency of every four to six hours, with a maximum of 4 g over 24 hours. For children under 12 years, oral and rectal doses are recommended as follows at the same frequency: 500 mg (10 to 12 years), 375 mg (8 to 10 years), 250 mg (6 to 8 years), 240 mg (4 to 6 years), 180 mg (2 to 4 years), 120 mg (6 to 24 months), and 60 mg (3 to 6 months). Paracetamol is the only recommended analgesic for children under 3 months of age (WHO 2012).

Paracetamol has been proven to be safe in appropriate and controlled dosages (Forrest 1982). However, adverse effects of paracetamol in the paediatric population can include hepatic or renal failure with overuse or overdose (Zyoud 2015). Other less common side effects include: malaise; toxic epidermal necrolysis skin reactions (including Stevens‐Johnson syndrome), acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis; blood disorders including neutropenia, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia; and upon infusion, hypotension, flushing, and tachycardia (BNF 2016; Forrest 1982 ).

How the intervention might work

Although paracetamol has been widely used in medical practice, its mechanism of action remains uncertain (Graham 2013). The main proposed mechanism is the inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes through metabolism by the peroxidase function of these isoenzymes. This process results in inhibition of phenoxyl radical formation from a critical tyrosine residue important for the cyclooxygenase activity of COX‐1 and COX‐2 and prostaglandin synthesis (Graham 2013; Jozwiak‐Bebenista 2014). Paracetamol is a preferential inhibitor of COX‐2 due to its gastrointestinal tolerance and poor inhibition of platelet activity (Graham 2013; Hinz 2008; Hinz 2012).

Paracetamol is widely considered to be a safe drug when administered in appropriate doses (Jozwiak‐Bebenista 2014); however, there is clear evidence that higher doses or prolonged use of paracetamol can lead to liver failure (where the paracetamol compounds are metabolised), cardiovascular events, and even death (Chan 2006; Daly 2008; Forman 2005; Graham 2013; Roberts 2016; Sheen 2002). Overall, paracetamol is considered to be a safe and effective analgesic option that is tolerable in the majority of paediatric patients. Using the recommended doses, severe side effects can be avoided and adequate relief of chronic pain can be achieved for the infant, child, or adolescent.

Why it is important to do this review

The paediatric population is at risk of inadequate management of pain (AMA 2013). Some conditions that would be aggressively treated in adult patients are being managed with insufficient analgesia in younger populations (AMA 2013). Although there have been repeated calls for best evidence to treat children's pain, such as Eccleston 2003, there are no easily available summaries of the most effective paediatric pain relief.

This review formed part of a Programme Grant addressing the unmet needs of people with chronic pain, commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in the UK. This topic was identified in June 2015 during consultation with experts in paediatric pain. Please see Appendix 1 for full details of the meeting. The standards used to assess evidence in chronic pain trials have changed substantially in recent years, with particular attention being paid to trial duration, withdrawals, and statistical imputation following withdrawal, all of which can substantially alter estimates of efficacy. The most important change was to encourage a move from using average pain scores, or average change in pain scores, to the number of children who have a large decrease in pain (by at least 50%). Pain intensity reduction of 50% or more has been shown to correlate with improvements in comorbid symptoms, function, and quality of life (Moore 2011a). These standards are set out in the reference guide for pain studies (AUREF 2012).

Objectives

To assess the analgesic efficacy and adverse events of paracetamol (acetaminophen) used to treat chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents aged between birth and 17 years, in any setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We planned to include randomised controlled trials, with or without blinding, and participant‐ or observer‐reported outcomes.

Full journal publication was required, with the exception of online clinical trial results, summaries of otherwise unpublished clinical trials, and abstracts with sufficient data for analysis. We planned to include studies published in any language. We excluded abstracts (usually meeting reports) or unpublished data, non‐randomised studies, studies of experimental pain, case reports, and clinical observations.

Types of participants

We planned to include studies of infants, children, and adolescents, aged from birth to 17 years old, with chronic or recurrent pain (lasting for three months or longer), arising from genetic conditions, neuropathy, or other conditions. These included but were not limited to chronic musculoskeletal pain and chronic abdominal pain.

We excluded studies of perioperative pain, acute pain, cancer pain, headache, migraine, and pain associated with primary disease or its treatment.

We planned to include studies of participants with more than one type of chronic pain, in which case we would analyse results according to the primary condition.

Types of interventions

We planned to include studies reporting interventions prescribing paracetamol for the relief of chronic pain by any route, in any dose, with comparison to a placebo or any active comparator. We did not consider interventions prescribing paracetamol in combination with another drug (such as opioids), as this comparison is covered in the two opioid reviews as part of this suite (Cooper 2017a; Wiffen 2017a).

Types of outcome measures

In order to be eligible for inclusion in this review, studies had to report pain assessment, as well as meeting the other selection criteria.

We planned to include trials measuring pain intensity and pain relief assessed using validated tools such as numerical rating scale (NRS), visual analogue scale (VAS), Faces Pain Scale ‐ Revised (FPS‐R), Colour Analogue Scale (CAS), or any other validated rating scale.

We were particularly interested in Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (PedIMMPACT) definitions for moderate and substantial benefit in chronic pain studies (PedIMMPACT 2008). These are defined as: at least 30% pain relief over baseline (moderate); at least 50% pain relief over baseline (substantial); much or very much improved on Patient Global Impression of Change scale (PGIC) (moderate); very much improved on PGIC (substantial).

These outcomes differ from those used in most earlier reviews, concentrating as they do on dichotomous outcomes where pain responses do not follow a normal (Gaussian) distribution. People with chronic pain desire high levels of pain relief, ideally more than 50% pain intensity reduction, and ideally having no worse than mild pain (Moore 2013a; O'Brien 2010).

We planned to record any reported adverse events. We planned to report the timing of outcome assessments.

Primary outcomes

Participant‐reported pain relief of 30% or greater

Participant‐reported pain relief of 50% or greater

PGIC much or very much improved

In the absence of self reported pain, we planned to consider the use of 'other‐reported' pain, typically by an observer such as a parent, carer, or healthcare professional (Stinson 2006; von Baeyer 2007).

Secondary outcomes

We identified the following with reference to the PedIMMPACT recommendations, which suggest core outcome domains and measures for consideration in paediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials (PedIMMPACT 2008).

Carer Global Impression of Change

Requirement for rescue analgesia

Sleep duration and quality

Acceptability of treatment

Physical functioning as defined by validated scales

Quality of life as defined by validated scales

Any adverse events

Withdrawals due to adverse events

Any serious adverse event. Serious adverse events typically include any untoward medical occurrence or effect that at any dose results in death, is life‐threatening, requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, is a congenital anomaly or birth defect, is an 'important medical event' that may jeopardise the patient, or may require an intervention to prevent one of the above characteristics or consequences.

Search methods for identification of studies

We developed the search strategy based on previous strategies used by the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group and carried out the searches.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via Cochrane Register of Studies Online), searched 6 September 2016;

MEDLINE (via Ovid) (1946 to September week 2 2016);

Embase (via Ovid) (1974 to 2016 week 38).

We used medical subject headings (MeSH) or equivalent and text word terms. We restricted our search to randomised controlled trials and clinical trials. There were no language or date restrictions. The focus of the key words in our search terms was on chronic pain and paracetamol. We tailored searches to individual databases. The search strategy for MEDLINE is in Appendix 3, Embase in Appendix 4, and CENTRAL in Appendix 5.

Searching other resources

We searched ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) for ongoing trials up to June 2017. In addition, we checked reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles for additional studies, and performed citation searches on key articles. We planned to contact experts in the field for unpublished and ongoing trials, however this was not necessary. We planned to contact study authors where necessary for additional information.

Data collection and analysis

We planned to perform separate analyses according to particular chronic pain conditions. We planned to combine different chronic pain conditions in analyses for exploratory purposes only.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently determined study eligibility by reading the abstract of each study identified by the search. Review authors independently eliminated studies that clearly did not satisfy inclusion criteria, and obtained full copies of the remaining studies. Two review authors independently read these studies to select those that met the inclusion criteria, a third review author adjudicating in the event of disagreement. We did not anonymise the studies in any way before assessment. We included a PRISMA flow chart to illustrate the results of the search and the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion in the review (Moher 2009), as recommended in section 11.2.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We planned to include studies in the review irrespective of whether measured outcome data were reported in a ‘usable’ way.

Data extraction and management

We planned to obtain full copies of the studies with two review authors independently carrying out data extraction. Where available, we would have extracted information about the pain condition, number of participants treated, drug and dosing regimen, study design (placebo or active control), study duration and follow‐up, analgesic outcome measures and results, withdrawals, and adverse events (participants experiencing any adverse event or serious adverse event). We planned to collate multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We planned to collect characteristics of the included studies in sufficient detail to populate a Characteristics of included studies table.

We planned to use a template data extraction form and checked for agreement before entry into Cochrane's statistical software Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014).

If a study had more than two intervention arms, we planned to only include the intervention groups and control groups that met the eligibility criteria. If multi‐arm studies were included, we planned to analyse multiple intervention groups in an appropriate way that avoided arbitrary omission of relevant groups and double‐counting of participants.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We planned for two review authors to independently assess risk of bias for each study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We planned to complete a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014).

We planned to assess the following for each study. We would have resolved any disagreements by discussion between review authors or when necessary by consulting a third review author.

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We planned to assess the method used to generate the allocation sequence as: low risk of bias (i.e. any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator); or unclear risk of bias (when the method used to generate the sequence was not clearly stated). We excluded studies that used a non‐random process and were therefore at high risk of bias (e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). The method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment determines whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment, or changed after assignment. We planned to assess the methods as: low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes); or unclear risk of bias (when the method was not clearly stated). We excluded studies that did not conceal allocation and were therefore at a high risk of bias (e.g. open list).

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). We planned to assess any methods used to blind the participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We planned to assess the methods as: low risk of bias (study states that the participants and personnel involved were blinded to treatment groups); unclear risk of bias (study does not state whether or not participants and personnel were blinded to treatment groups); or high risk of bias (participants or personnel were not blinded) (as stated in Types of studies, we included trials with or without blinding, and participant‐ or observer‐reported outcomes).

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). We planned to assess any methods used to blind the outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We planned to assess the methods as: low risk of bias (e.g. study states that it was single‐blinded and describes the method used to achieve blinding of the outcome assessor); unclear risk of bias (study states that outcome assessors were blinded but does not provide an adequate description of how this was achieved); or high risk of bias (outcome assessors were not blinded) (as stated in Types of studies, we included trials with or without blinding, and participant‐ or observer‐reported outcomes).

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature, and handling of incomplete outcome data). We planned to assess the methods used to deal with incomplete data as: low risk of bias (i.e. less than 10% of participants did not complete the study or 'baseline observation carried forward' (BOCF) analysis was used, or both); unclear risk of bias (used 'last observation carried forward' (LOCF) analysis); or high risk of bias (used 'completer' analysis).

Selective reporting (checking for possible reporting bias). We planned to assess the methods used to report the outcomes of the study as: low risk of bias (if all planned outcomes in the protocol or methods were reported in the results); unclear risk of bias (if there was not a clear distinction between planned outcomes and reported outcomes); high risk of bias (if some planned outcomes from the protocol or methods were clearly not reported in the results).

Size of study (checking for possible biases confounded by small size). We planned to assess studies as being at low risk of bias (200 participants or more per treatment arm); unclear risk of bias (50 to 199 participants per treatment arm); or high risk of bias (fewer than 50 participants per treatment arm).

Other bias. We planned to assess studies for any additional sources of bias as low, unclear, or high risk of bias, and provide rationale.

Measures of treatment effect

Where dichotomous data were available, we planned to calculate a risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and meta‐analyse the data as appropriate. We planned to calculate number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) where appropriate (McQuay 1998); for unwanted effects the NNTB becomes the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) and is calculated in the same manner. Where continuous data were reported, we planned to use appropriate methods to combine these data in the meta‐analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to accept randomisation to the individual participant only. We planned to split the control treatment arm between active treatment arms in a single study if the active treatment arms were not combined for analysis. We only accepted studies with minimum 10 participants per treatment arm.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to use intention‐to‐treat analysis where the intention‐to‐treat population consisted of participants who were randomised, took at least one dose of the assigned study medication, and provided at least one postbaseline assessment. We would have assigned missing participants zero improvement wherever possible.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to identify and measure heterogeneity as recommended in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We planned to deal with clinical heterogeneity by combining studies that examined similar conditions. We planned to undertake and present a meta‐analysis only if we judged participants, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes to be sufficiently similar to ensure a clinically meaningful answer. We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity visually and by using the I² statistic (L'Abbé 1987). When I² was greater than 50%, we planned to consider the possible reasons.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess the risk of reporting bias, as recommended in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

The aim of this review was to use dichotomous outcomes of known utility and of value to patients (Hoffman 2010; Moore 2010b; Moore 2010c; Moore 2010d; Moore 2013a). The review did not depend on what the authors of the original studies chose to report or not, though clearly difficulties arose in studies failing to report any dichotomous results. We planned to extract and report continuous data in a narrative way, which probably reflect efficacy and utility poorly, and is useful for illustrative purposes only.

We planned to assess publication bias using a method designed to detect the amount of unpublished data with a null effect required to make any result clinically irrelevant (usually taken to mean a number needed to treat (NNT) of 10 or higher) (Moore 2008).

Data synthesis

We planned to use a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis. We planned to use a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis if there was significant clinical heterogeneity and combining studies was considered to be appropriate. We planned to conduct our analysis using the primary outcomes of pain and adverse events, and to calculate the NNTHs for adverse events. We planned to use the Cochrane software program Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014).

Quality of the evidence

To analyse data, two review authors would have independently rated the quality of each outcome. We would have used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the body of evidence related to each of the key outcomes, and planned to report our judgement in a 'Summary of findings' table per Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook (Appendix 6) (Higgins 2011).

In addition, there may be circumstances where the overall rating for a particular outcome would need to be adjusted per GRADE guidelines (Guyatt 2013a). For example, if there were so few data that the results were highly susceptible to the random play of chance, or if studies used LOCF imputation in circumstances where there were substantial differences in adverse event withdrawals, one would have no confidence in the result, and would need to downgrade the quality of the evidence by three levels, to very low quality. In circumstances where no data were reported for an outcome, we planned to report the level of evidence as 'no evidence to support or refute' (Guyatt 2013b).

'Summary of findings' table

We planned to include a 'Summary of findings' table as set out in the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group’s author guide (AUREF 2012), and recommended in section 4.6.6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We planned to justify and document all assessments of the quality of the body of evidence.

In an attempt to reliably interpret the findings of this systematic review, we planned to assess the summarised data using the GRADE guidelines (Appendix 6) to rate the quality of the body of evidence of each of the key outcomes listed in Types of outcome measures per Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook, as appropriate (Guyatt 2011; Higgins 2011). Utilising the explicit criteria against study design, risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and magnitude of effect, we planned to summarise the evidence in an informative, transparent, and succinct 'Summary of findings' table or 'Evidence profile' table (Guyatt 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analyses where a minimum number of data were available (at least 200 participants per treatment arm). We planned to analyse according to age group; type of drug; geographical location or country; type of control group; baseline measures; frequency, dose, and duration of drugs; and nature of drug.

We planned to investigate whether the results of subgroups were significantly different by inspecting the overlap of confidence intervals and by performing the test for subgroup differences available in Review Manager 5.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not plan to carry out any sensitivity analysis because the evidence base is known to be too small to allow reliable analysis; we did not plan to pool results from chronic pain of different origins in the primary analyses. We planned to examine details of dose escalation schedules in the unlikely circumstance that this could provide some basis for a sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

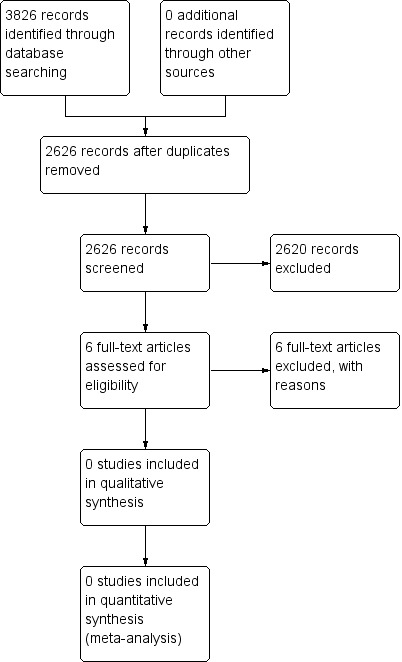

A PRISMA flow diagram of the search results is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Searches of the three main databases revealed 3826 records of titles and abstracts, of which 1200 duplicates were removed. Our searches of ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO ICTRP yielded no additional eligible studies.

We screened the remaining 2626 titles and abstracts for eligibility, finding 2620 to be ineligible.

We read the full texts of the remaining six studies, of which all six were found to be ineligible and excluded. We identified no ongoing studies. No studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria or were eligible to be entered into a quantitative analysis.

Included studies

No studies met our inclusion criteria for this review.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies.

We excluded six studies in this review. Five investigated adult populations, and one study was not randomised. (McGuinness 1969).

Risk of bias in included studies

No studies were eligible for inclusion in this review, therefore we did not perform a 'Risk of bias' assessment.

Effects of interventions

No studies were eligible for inclusion in this review, therefore we could not assess the efficacy of paracetamol to treat chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents. We were also unable to examine any adverse effects. Due to the lack of evidence in this field, we were unable to judge the quality of evidence and therefore there is no evidence to support or refute the use of paracetamol for children with chronic non‐cancer pain.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We were unable to find any randomised controlled trials for inclusion in this review, therefore we were unable to comment about efficacy or harm from the use of paracetamol to treat chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents. Similarly, we could not comment on our remaining secondary outcomes: Carer Global Impression of Change; requirement for rescue analgesia; sleep duration and quality; acceptability of treatment; physical functioning; and quality of life. Due to the lack of evidence in this field, we are unable to judge the quality of evidence and therefore there is no evidence to support or refute the use of paracetamol for children with chronic non‐cancer pain.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In adults, the efficacy of paracetamol in chronic pain conditions is being challenged. Paracetamol alone is no better than placebo for low back pain (Saragiotto 2016), spinal pain, or osteoarthritis (Machado 2015), and there is very little evidence of efficacy in neuropathic pain, despite its widespread use (Wiffen 2016). The efficacy of paracetamol in acute pain is established in acute postoperative pain, Moore 2015, and migraine (Derry 2013). Paracetamol is generally less effective than non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (Marjoribanks 2015; Moore 2015). Widespread use of paracetamol combined with new evidence about harm has challenged the common assumption of safety (Moore 2016; Roberts 2016).

In children, there is little evidence concerning the pain‐relieving effects of paracetamol in neonates (Ohlsson 2016), for acute otitis media (Sjoukes 2016), or for relief of fever (Wong 2013).

The suite of reviews

This review is part of a suite of reviews on pharmacological interventions for chronic pain and cancer‐related pain in children and adolescents (Appendix 1). Taking a broader view on this suite of reviews, some pharmacotherapies (investigated in our other reviews) are likely to provide more data than others. The results of this review were thus as expected considering that randomised controlled trials in children are known to be limited. The results have the potential to inform policymaking decisions for funding future clinical trials into paracetamol treatment of child and adolescent pain, therefore any results (large or small) are important in order to capture a snapshot of the current evidence for paracetamol.

Quality of the evidence

No studies were eligible for inclusion in this review. We were unable to find any published randomised controlled trials to support or refute the use of paracetamol to treat chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents. We were unable to examine any adverse effects.

This review shows that there is an absence of evidence from trials that paracetamol is effective in chronic non‐cancer pain in children. While it may be the case that this absence of evidence reflects the inadequacy of paracetamol for this purpose and that its use as a monotherapy analgesic is more likely to cause harm than benefit, the opposite may also pertain, as the data are lacking. It is difficult to conduct long‐term randomised controlled trials in children with chronic non‐cancer conditions, and few observational/clinical data have been published.

Potential biases in the review process

We carried out extensive searches of major databases using broad search criteria, and also searched two large clinical trial registries. We consider it to be unlikely that we have missed relevant studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We were not able to identify any published systematic reviews on this topic.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

General

We identified no randomised controlled trials to support or refute the use of paracetamol to treat chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents.

This is disappointing as children and adolescents have specific needs for analgesia. Extrapolating from adult data may be possible but could compromise effectiveness and safety.

Despite the lack of evidence of long‐term effectiveness and safety, clinicians prescribe paracetamol to children and adolescents when medically necessary, based on extrapolation from adult guidelines, or when perceived benefits in conjunction with other multimodalities improve a child’s care. Appropriate medical management is necessary in disease‐specific conditions such as for incurable progressive degenerative conditions of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, osteogenesis imperfecta, congenital degenerative spine, and neurodegenerative conditions such as spasticity/dystonia in mitochondrial Leigh’s disease, leukoencephalopathy, and severe cerebral palsy.

For children with chronic non‐cancer pain

The amount and quality of evidence around the use of paracetamol for treating chronic non‐cancer pain is low. This means that at present, treatment is based on clinical experience and advice from respected authorities. We could make no judgement about adverse events or withdrawals.

For clinicians

The amount and quality of evidence around the use of paracetamol for treating chronic non‐cancer pain is low. This means that at present, treatment is based on clinical experience and advice from respected authorities. We could make no judgement about adverse events or withdrawals.

For policymakers

The amount and quality of evidence around the use of paracetamol for treating chronic non‐cancer pain is low. This means that at present, treatment is based on clinical experience and advice from respected authorities. We could make no judgement about adverse events or withdrawals.

For funders

The amount and quality of evidence around the use of paracetamol for treating chronic non‐cancer pain is low. This means that at present, treatment is based on clinical experience and advice from respected authorities. We could make no judgement about adverse events or withdrawals.

Implications for research.

General

The heterogeneous nature of pain in children needs to be recognised and presents challenges in designing research studies.

Overall, there appears to be a gap between what is done in practice and what is investigated in prospective clinical trials for treating children's and adolescents' pain with paracetamol.

The lack of evidence highlighted in this review implies that there is a need to fund and support suitable research for the treatment of chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents.

Design

Several methodological issues stand out.

The first is the use of outcomes of value to children with chronic non‐cancer pain. Existing trials are designed more for purposes of registration and marketing than informing and improving clinical practice, that is the outcomes are often average pain scores or statistical differences, and rarely how many individuals achieve satisfactory pain relief. In the case where pain is initially mild or moderate, consideration needs to be given to what constitutes a satisfactory outcome. The situation is somewhat different to that of strong opioids that are used for moderate to severe cancer pain.

The second issue is the time taken to achieve good pain relief. We have no information about what constitutes a reasonable time to achieve a satisfactory result. This may best be approached initially with a Delphi methodology.

The third issue is design. Studies with a cross‐over design often have significant attrition, therefore parallel‐group designs may be preferable. Alternative concentration‐response or dose‐response relationships in individual children could be explored using population analysis techniques (Anderson 2015). These have been used to explore acute pain in both adults and children as well as chronic pain in adults (Shinoda 2007).

The fourth issue is size. The studies need to be suitably powered to ensure adequate data after the effect of attrition due to various causes. Much larger studies of several hundred participants or more are needed.

There are some other design issues that might be addressed. Most important might well be a clear decision concerning the gold‐standard treatment comparator.

An alternative approach may be to design large registry studies. This could provide an opportunity to foster collaboration among paediatric clinicians and researchers, in order to create an evidence base.

Measurement (endpoints)

Trials need to consider the additional endpoint of 'no worse than mild pain' as well as the standard approaches to pain assessment.

Other

The obvious study design of choice is the prospective randomised trial, but other pragmatic designs may be worth considering. Studies could incorporate initial randomisation but a pragmatic design in order to provide immediately relevant information on effectiveness and costs. Such designs in pain conditions have been published (Moore 2010e).

Feedback

Feedback received, 11 March 2019

Summary

Name: Therese Dalsbø Email Address: mail.therese@gmail.com

Comment: Dear Authors, Your review was a very interesting read about an important question. However, I was surprised to read Your statement that the quality of the evidence was very low. As far as I can see you did not include any evidence. In a summary of findings table you could state that we cannot say anything about the certainty of the evidence because we did not find any evidence. As I understand it you base your judgement in GRADE about the effect estimates and here you don't have any estimates. A good summary about grade and summary of finding tables is available here: https://cc.cochrane.org/sites/cc.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/how_to_grade.pdf

Can you please explain more details how you came to grade the none existing evidence to very low?

Reply

Dear Therese Dalsbø,

Thank you very much for your feedback and time taken to offer your thoughts on our review. You have correctly identified our mistake in following our own GRADE methods. Our methods state under Data Collection & Analysis/Data Synthesis/Quality of the Evidence:

"In addition, there may be circumstances where the overall rating for a particular outcome would need to be adjusted per GRADE guidelines (Guyatt 2013a). For example, if there were so few data that the results were highly susceptible to the random play of chance, or if studies used LOCF imputation in circumstances where there were substantial differences in adverse event withdrawals, one would have no confidence in the result, and would need to downgrade the quality of the evidence by three levels, to very low quality. In circumstances where no data were reported for an outcome, we planned to report the level of evidence as 'no evidence to support or refute' (Guyatt 2013b)."

We incorrectly rated the quality of the (lack of) evidence as 'very low', when we should have followed the method in the final sentence and reported it as 'no evidence to support or refute'. We have now made these amendments throughout the review. We chose not to create a Summary of Findings table as there was nothing to report on. There are no requirements to add this to the Differences Between Protocol and Review section as we are following our methods a priori.

We thank you again for your feedback and appreciate your time.

Kind regards,

Tess Cooper and the author team (April 2019)

Contributors

Feedback Editor Hayley Barnes, Senior Editor Phillip Wiffen (acting on behalf of Co‐ordinating Editor Christopher Eccleston who is a review author), and Managing Editor Anna Erskine.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 September 2019 | Amended | We amended the GRADE methods for assessing no evidence, for consistency with the other reviews in this series. Clarification added to Declarations of interest. |

| 22 May 2019 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2017 Review first published: Issue 8, 2017

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 March 2019 | Feedback has been incorporated | See Feedback. |

| 6 July 2018 | Amended | Searches updated with terms relating to 'infants'. We did not identify any new studies. |

| 8 March 2018 | Amended | Affiliation updated. |

| 14 August 2017 | Amended | References for some reviews from the suite amended to reflect correct publication Issue. |

Notes

A restricted search in March 2019 did not identify any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions. Therefore, this review has now been stabilised following discussion with the authors and editors. The review will be re‐assessed for updating in five years. If appropriate, we will update the review before this date if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitates major revisions.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Phil Wiffen to the template protocol for this suite.

We thank Andrew Moore, Tonya Palermo, Andrew Gray, Gustaf Ljungman, and Marie‐Claude Gregorie for peer reviewing.

Cochrane Review Group funding acknowledgement: the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group (PaPaS). Disclaimer: the views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, National Health Service (NHS), or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Meeting for NIHR Programme Grant agenda on pain in children

Date

Monday 1st June 2015

Location

International Association of the Study of Pain (IASP) Conference, Seattle, USA

Delegates

Allen Finlay, Anna Erskine, Boris Zernikow, Chantal Wood, Christopher Eccleston, Elliot Krane, George Chalkaiadis, Gustaf Ljungman, Jacqui Clinch, Jeffrey Gold, Julia Wager, Marie‐Claude Gregoire, Miranda van Tilburg, Navil Sethna, Neil Schechter, Phil Wiffen, Richard Howard, Susie Lord.

Purpose

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (UK) Programme Grant ‐ Addressing the unmet need of chronic pain: providing the evidence for treatments of pain.

Proposal

Nine reviews in pharmacological interventions for chronic pain in children and adolescents: Children (5 new, 1 update, 1 overview, and 2 rapid) self‐management of chronic pain is prioritised by the planned NICE guideline. Pain management (young people and adults) with a focus on initial assessment and management of persistent pain in young people and adults.

We propose titles in paracetamol, ibuprofen, diclofenac, other NSAIDs, and codeine, an overview review on pain in the community, 2 rapid reviews on the pharmacotherapy of chronic pain, and cancer pain, and an update of psychological treatments for chronic pain.

Key outcomes

The final titles: (1) opioids for cancer‐related pain (Wiffen 2017a), (2) opioids for chronic non‐cancer pain (Cooper 2017a), (3) antiepileptic drugs for chronic non‐cancer pain (Wiffen 2017b), (4) antidepressants for chronic non‐cancer pain (Cooper 2017b), (5) non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for chronic non‐cancer pain (Eccleston 2017), (6) non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for cancer‐related pain (Cooper 2017c), (7) paracetamol for chronic non‐cancer pain (Cooper 2017d ‐ this review).

PICO

Patients: children, aged 3 to 12, chronic pain defined as pain persisting for 3 months (NB: now changed to: birth to 17 years to include infants, children and adolescents).

Interventions: by drug class including antiepileptic drugs, antidepressants, opioids, NSAIDs, paracetamol.

Comparisons: maintain a separation of cancer and non‐cancer, exclude headache, in comparison with placebo and or active control.

Outcomes: we will adopt the IMMPACT criteria.

Appendix 2. Methodological considerations for chronic pain

There have been several recent changes in how the efficacy of conventional and unconventional treatments is assessed in chronic painful conditions. The outcomes are now better defined, particularly with new criteria for what constitutes moderate or substantial benefit (Dworkin 2008); older trials may only report participants with 'any improvement'. Newer trials tend to be larger, avoiding problems from the random play of chance. Newer trials also tend to be of longer duration, up to 12 weeks, and longer trials provide a more rigorous and valid assessment of efficacy in chronic conditions. New standards have evolved for assessing efficacy in neuropathic pain, and we are now applying stricter criteria for the inclusion of trials and assessment of outcomes, and are more aware of problems that may affect our overall assessment. In this new review we summarise some of the recent insights that must be considered.

Pain results tend to have a U‐shaped distribution rather than a bell‐shaped distribution. This is true in acute pain (Moore 2011a; Moore 2011b), back pain (Moore 2010d), and arthritis (Moore 2010c), as well as in fibromyalgia (Straube 2010); in all cases average results usually describe the experience of almost no one in the trial. Data expressed as averages are potentially misleading, unless they can be proven to be suitable.

As a consequence, we have to depend on dichotomous results (the individual either has or does not have the outcome) usually from pain changes or patient global assessments. The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) group has helped with their definitions of minimal, moderate, and substantial improvement (Dworkin 2008). In arthritis, trials of less than 12 weeks' duration, and especially those shorter than eight weeks, overestimate the effect of treatment (Moore 2010c); the effect is particularly strong for less effective analgesics, and this may also be relevant in neuropathic‐type pain.

The proportion of patients with at least moderate benefit can be small, even with an effective medicine, falling from 60% with an effective medicine in arthritis to 30% in fibromyalgia (Moore 2009; Moore 2010c; Moore 2013b; Moore 2014b; Straube 2008; Sultan 2008). A Cochrane review of pregabalin in neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia demonstrated different response rates for different types of chronic pain (higher in diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia and lower in central pain and fibromyalgia) (Moore 2009). This indicates that different neuropathic pain conditions should be treated separately from one another, and that pooling should not be done unless there are good grounds for doing so.

Individual patient analyses indicate that patients who get good pain relief (moderate or better) have major benefits in many other outcomes, affecting quality of life in a significant way (Moore 2010b; Moore 2014a).

Imputation methods such as last observation carried forward (LOCF), used when participants withdraw from clinical trials, can overstate drug efficacy, especially when adverse event withdrawals with drug are greater than those with placebo (Moore 2012).

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy (via Ovid)

1. exp Child/ 2. exp Adolescent/ 3. exp Infant/ 4. (child* or boy* or girl* or adolescen* or teen* or toddler* or preschooler* or pre‐schooler* or baby or babies or infant*).tw. 5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6. Acetaminophen/ 7. (acetaminophen or paracetamol or Calpol or Panadol or Tylenol).mp. 8. 6 or 7 9. exp Pain/ 10. pain*.tw. 11. 9 or 10 12. 5 and 8 and 11 13. randomized controlled trial.pt. 14. controlled clinical trial.pt. 15. randomized.ab. 16. placebo.ab. 17. drug therapy.fs. 18. randomly.ab. 19. trial.ab. 20. groups.ab. 21. 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 22. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 23. 21 not 22 24. 12 and 23

Appendix 4. Embase search strategy (via Ovid)

1. exp Child/ 2. exp Adolescent/ 3. exp Infant/ 4. (child* or boy* or girl* or adolescen* or teen* or toddler* or preschooler* or pre‐schooler* or baby or babies or infant*).tw. 5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6. Paracetamol/ 7. (acetaminophen or paracetamol or Calpol or Panadol or Tylenol).mp. 8. 6 or 7 9. exp Pain/ 10. pain*.tw. 11. 9 or 10 12. 5 and 8 and 11 13. random$.tw. 14. factorial$.tw. 15. crossover$.tw. 16. cross over$.tw. 17. cross‐over$.tw. 18. placebo$.tw. 19. (doubl$ adj blind$).tw. 20. (singl$ adj blind$).tw. 21. assign$.tw. 22. allocat$.tw. 23. volunteer$.tw. 24. Crossover Procedure/ 25. double‐blind procedure.tw. 26. Randomized Controlled Trial/ 27. Single Blind Procedure/ 28. or/13‐27 29. (animal/ or nonhuman/) not human/ 30. 28 not 29 31. 12 and 30

Appendix 5. CENTRAL search strategy (via CRSO)

#1MESH DESCRIPTOR child EXPLODE ALL TREES #2MESH DESCRIPTOR adolescent EXPLODE ALL TREES #3MESH DESCRIPTOR infant EXPLODE ALL TREES #4((child* or boy* or girl* or adolescen* or teen* or toddler* or preschooler* or pre‐schooler* or baby or babies or infant*)):TI,AB,KY #5#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 #6MESH DESCRIPTOR Acetaminophen #7((acetaminophen or paracetamol or Calpol or Panadol or Tylenol)):TI,AB,KY #8#6 OR #7 #9MESH DESCRIPTOR pain EXPLODE ALL TREES #10pain*:TI,AB,KY #11#9 OR #10 #12#5 AND #8 AND #11

Appendix 6. GRADE guidelines

Some advantages of utilising the GRADE process are (Guyatt 2008):

transparent process of moving from evidence to recommendations;

clear separation between quality of evidence and strength of recommendations;

explicit, comprehensive criteria for downgrading and upgrading quality of evidence ratings; and

clear, pragmatic interpretation of strong versus weak recommendations for clinicians, patients, and policymakers.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence:

high: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect;

moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different;

low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect; and

very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

We will decrease the grade if there is:

serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) limitation to study quality;

important inconsistency (‐1);

some (‐1) or major (‐2) uncertainty about directness;

imprecise or sparse data (‐1); or

high probability of reporting bias (‐1).

We will increase the grade if there is:

strong evidence of association ‐ significant relative risk of > 2 (< 0.5) based on consistent evidence from two or more observational studies, with no plausible confounders (+1);

very strong evidence of association ‐ significant relative risk of > 5 (< 0.2) based on direct evidence with no major threats to validity (+2);

evidence of a dose response gradient (+1); or

all plausible confounders would have reduced the effect (+1).

"In addition, there may be circumstances where the overall rating for a particular outcome would need to be adjusted per GRADE guidelines (Guyatt 2013a). For example, if there were so few data that the results were highly susceptible to the random play of chance, or if studies used LOCF imputation in circumstances where there were substantial differences in adverse event withdrawals, one would have no confidence in the result, and would need to downgrade the quality of the evidence by three levels, to very low quality. In circumstances where no data were reported for an outcome, we planned to report the level of evidence as 'no evidence to support or refute' (Guyatt 2013b)."

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ali 2007 | Participants: women aged 18 years and over Intervention: paracetamol combined with caffeine, not paracetamol alone |

| Berry 1975 | Adult population, participants aged 16 to 39 years (mean 26 years) |

| Cubero 2010 | Participants aged 18 years and over |

| McGuinness 1969 | Not randomised |

| Mueller‐Lissner 2005 | Participants aged 18 years and over |

| Valle‐Jones 1992 | Participants: age range 14 to 76 years, however, mean age was 43 years. Unlikely to gain subunit data for 14 to 17 years |

Differences between protocol and review

We made minor changes to the wording in the Background section.

We did not consider studies with fewer than 10 participants per treatment arm for inclusion in this review, as is standard practice for this group.

Contributions of authors

TC and CE registered the title.

TC, Phil Wiffen, and CE wrote the template protocol for the suite of children's reviews, of which this review is a part.

All authors contributed to writing the protocol and all authors agreed on the final version.

TC and EF were responsible for data extraction and analysis.

All authors were responsible for the writing of the Discussion for the full review.

All authors will be responsible for the completion of updates.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

NIHR Programme Grant, Award Reference Number: 13/89/29 (Addressing the unmet need of chronic pain: providing the evidence for treatments of pain)

Declarations of interest

CE: none known. Since CE is an author as well as the PaPaS Co‐ordinating Editor at the time of writing, we acknowledge the input of Neil O'Connell who acted as Sign Off Editor for this review. CE had no input into the editorial decisions or processes for this review.

TC: none known.

BA: none known; BA is a specialist anaesthetist and intensive care physician and manages the perioperative care of children requiring surgery and those critically ill requiring intensive care.

EF: none known.

NW: none known; NW is a specialist paediatric pain clinician and treats patients with chronic pain.

DGW: none known; DGW is a consultant in paediatric anaesthesia and pain medicine and treats children with acute and chronic pain.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Ali 2007 {published data only}

- Ali Z, Burnett I, Eccles R, North M, Jawad M, Jawad S, et al. Efficacy of a paracetamol and caffeine combination in the treatment of the key symptoms of primary dysmenorrhoea. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2007;23(4):841‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berry 1975 {published data only}

- Berry FN, Miller JM, Levin HM, Bare WW, Hopkinson JH 3rd, Feldman AJ. Relief of severe pain with acetaminophen in a new dose formulation versus propoxyphene hydrochloride 65 mg. and placebo: a comparative double‐blind study. Current Therapeutic Research, Clinical and Experimental 1975;17(4):361‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cubero 2010 {published data only}

- Cubero DIG, Giglio A. Early switching from morphine to methadone is not improved by acetaminophen in the analgesia of concologic patients: a prospective, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:235‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McGuinness 1969 {published data only}

- McGuinness BW, Lloyd‐Jones M, Fowler PD. A double‐blind comparative trial of 'parazolidin' and paracetamol. British Journal of Clinical Practice 1969;23(11):452‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mueller‐Lissner 2005 {published data only}

- Mueller‐Lissner S, Tytgat GN, Paulo LG, Guiqgleys EMM, Bubeck J, Peil H, et al. Placebo‐ and paracetamol‐controlled study on the efficacy and tolerability of hyoscine butylbromide in the treatment of patients with recurrent crampy abdominal pain. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapies 2005;23:1741‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Valle‐Jones 1992 {published data only}

- Valle‐Jones JC, Walsh H, O'Hara J, O'Hara H, Davery NB, Hopkin‐Richards H. Controlled trial of a back support ('Lumbotrain') in patients with non‐specific low back pain. Current Medical Research and Opinion 1992;12(9):604‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

AMA 2013

- American Medical Association. Pediatric pain management. https://www.ama‐assn.org/ 2013 (accessed 25 January 2016).

Anderson 2015

- Anderson BJ, Hannam JA. Considerations when using PKPD modelling to determine effectiveness of simple analgesics in children. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism and Toxicology 2015;11(9):1393‐408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

AUREF 2012

- Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group. PaPaS author and referee guidance. papas.cochrane.org/papas‐documents 2012 (accessed 16 July 2016).

BNF 2016

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. London (UK): BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Caes 2016

- Caes L, Boemer KE, Chambers CT, Campbell‐Yeo M, Stinson J, Birnie KA, et al. A comprehensive categorical and bibliometric analysis of published research articles on pediatric pain from 1975 to 2010. Pain 2016;157(2):302‐13. [DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000403] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chan 2006

- Chan AT, Manson JE, Albert CM, Chae CU, Rexrode KM, Curhan GC, et al. Nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and the risk of cardiovascular events. Circulation 2006;113:1578‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 2017a

- Cooper TE, Fisher E, Gray A, Krane E, Sethna NF, Tilburg M, et al. Opioids for chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012538.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 2017b

- Cooper TE, Heathcote L, Clinch J, Gold J, Howard R, Lord S, et al. Antidepressants for chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012535.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 2017c

- Cooper TE, Heathcote L, Anderson B, Gregoire MC, Ljungman G, Eccleston C. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for cancer‐related pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012563.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Daly 2008

- Daly FFS, Fountain JS, Murray L, Graudins A, Buckley NA. Guidelines for the management of paracetamol poisoning in Australia and New Zealand ‐ explanation and elaboration. A consensus statement from clinical toxicologists consulting to the Australasian poisons information centres. Medical Journal of Australia 2008;188:296‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derry 2013

- Derry S, Moore RA. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008040.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dworkin 2008

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Journal of Pain 2008;9(2):105‐21. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eccleston 2003

- Eccleston C, Malleson PM. Management of chronic pain in children and adolescents (Editorial). BMJ 2003;326:1408‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eccleston 2017

- Eccleston C, Cooper TE, Fisher E, Anderson B, Wilkinson N. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for chronic non‐cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012537.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FDA 2017

- US Food, Drug Administration. Acetaminophen information. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm165107.htm (accessed 31 March 2017).

Forman 2005

- Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Non‐narcotic analgesic dose and risk of incident hypertension in US women. Hypertension 2005;46:500‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Forrest 1982

- Forrest JA, Clements JA, Prescott LF. Clinical pharmacokinetics of paracetamol. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 1982;7(2):93‐107. [PUBMED: 7039926] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graham 2013

- Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, Mohamudally A, Scott KF. The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings. Inflammopharmacology 2013;21:201‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2008

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck‐Ytter Y, Alonso‐Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924‐6. [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2011

- Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction ‐ GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2011;64:383‐94. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2013a

- Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Sultan S, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Alonso‐Coelle P, et al. Making an overall rating of the confidence in effect estimates for a single outcome and for all outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2013;66(2):151‐7. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.006] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2013b

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Santesso N, Helfand M, Vist G, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 12. Preparing summary of findings tables ‐ binary outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2013;66(2):158‐72. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.012] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

Hinz 2008

- Hinz B, Cheremina O, Brune K. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is a selective cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor in man. FASEB Journal 2008;22:383‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hinz 2012

- Hinz B, Brune K. Paracetamol and cyclooxygenase inhibition: is there a cause for concern?. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2012;71:20‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hoffman 2010

- Hoffman DL, Sadosky A, Dukes EM, Alvir J. How do changes in pain severity levels correspond to changes in health status and function in patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy?. Pain 2010;149(2):194‐201. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.017] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jozwiak‐Bebenista 2014

- Jozwiak‐Bebenista M, Nowak JZ. Paracetamol: mechanism of action, applications and safety concern. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica 2014;71:11‐23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

L'Abbé 1987

- L'Abbé KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K. Meta‐analysis in clinical research. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987;107:224‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Machado 2015

- Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Lin CW, Day RO, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ 2015;350:h1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marjoribanks 2015

- Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke RO, Farquhar C, Proctor M. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001751.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McQuay 1998

- McQuay H, Moore R. An Evidence‐based Resource for Pain Relief. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Moher 2009

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2008

- Moore RA, Barden J, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Managing potential publication bias. In: McQuay HJ, Kalso E, Moore RA editor(s). Systematic Reviews in Pain Research: Methodology Refined. Seattle (WA): IASP Press, 2008:15‐24. [ISBN: 978‐0‐931092‐69‐5] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2009

- Moore RA, Straube S, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Pregabalin for acute and chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007076.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2010a

- Moore RA, Eccleston C, Derry S, Wiffen P, Bell RF, Straube S, et al. "Evidence" in chronic pain ‐ establishing best practice in the reporting of systematic reviews. Pain 2010;150(3):386‐9. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.011] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2010b

- Moore RA, Straube S, Paine J, Phillips CJ, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Fibromyalgia: moderate and substantial pain intensity reduction predicts improvement in other outcomes and substantial quality of life gain. Pain 2010;149(2):360‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2010c

- Moore RA, Moore OA, Derry S, Peloso PM, Gammaitoni AR, Wang H. Responder analysis for pain relief and numbers needed to treat in a meta‐analysis of etoricoxib osteoarthritis trials: bridging a gap between clinical trials and clinical practice. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2010;69(2):374‐9. [DOI: 10.1136/ard.2009.107805] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2010d

- Moore RA, Smugar SS, Wang H, Peloso PM, Gammaitoni A. Numbers‐needed‐to‐treat analyses ‐ do timing, dropouts, and outcome matter? Pooled analysis of two randomized, placebo‐controlled chronic low back pain trials. Pain 2010;151(3):592‐7. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.2013] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2010e

- Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ, Straube S, Aldington D, Wiffen P, et al. ACTINPAIN writing group of the IASP Special Interest Group (SIG) on Systematic Reviews in Pain Relief. Clinical effectiveness: an approach to clinical trial design more relevant to clinical practice, acknowledging the importance of individual differences. Pain 2010;149:173‐6. [PUBMED: 19748185] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2011a

- Moore RA, Straube S, Paine J, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Minimum efficacy criteria for comparisons between treatments using individual patient meta‐analysis of acute pain trials: examples of etoricoxib, paracetamol, ibuprofen, and ibuprofen/paracetamol combinations after third molar extraction. Pain 2011;152(5):982‐9. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.030] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2011b

- Moore RA, Mhuircheartaigh RJ, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Mean analgesic consumption is inappropriate for testing analgesic efficacy in post‐operative pain: analysis and alternative suggestion. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 2011;28(6):427‐32. [DOI: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328343c569] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2012

- Moore RA, Straube S, Eccleston C, Derry S, Aldington D, Wiffen P, et al. Estimate at your peril: imputation methods for patient withdrawal can bias efficacy outcomes in chronic pain trials using responder analyses. Pain 2012;153(2):265‐8. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.004] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2013a

- Moore RA, Straube S, Aldington D. Pain measures and cut‐offs ‐ 'no worse than mild pain' as a simple, universal outcome. Anaesthesia 2013;68(4):400‐12. [DOI: 10.1111/anae.12148] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2013b

- Moore A, Derry S, Eccleston C, Kalso E. Expect analgesic failure; pursue analgesic success. BMJ 2013;346:f2690. [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.f2690] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2014a

- Moore RA, Derry S, Taylor RS, Straube S, Phillips CJ. The costs and consequences of adequately managed chronic non‐cancer pain and chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Practice 2014;14(1):79‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2014b

- Moore RA, Cai N, Skljarevski V, Tölle TR. Duloxetine use in chronic painful conditions ‐ individual patient data responder analysis. European Journal of Pain 2014;18(1):67‐75. [DOI: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00341.x] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2015

- Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Wiffen PJ. Single dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults ‐ an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008659.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2016

- Moore RA, Moore N. Paracetamol and pain: the kiloton problem. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2016;23:187‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NICE 2016

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Analgesia ‐ mild‐to‐moderate pain. cks.nice.org.uk/analgesia‐mild‐to‐moderate‐pain#!scenario:1 2016 (accessed prior to 10 June 2017).

O'Brien 2010

- O'Brien EM, Staud RM, Hassinger AD, McCulloch RC, Craggs JG, Atchinson JW, et al. Patient‐centered perspective on treatment outcomes in chronic pain. Pain Medicine 2010;11(1):6‐15. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00685.x] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ohlsson 2016

- Ohlsson A, Shah PS. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for prevention or treatment of pain in newborns. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011219.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

PedIMMPACT 2008

- McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, Dworking RH, Brown MT, Davidson K, et al. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT. Journal of Pain 2008;9(9):771‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Ripamonti 2008

- Ripamonti C, Bandieri E. Pain therapy. Journal of Oncology and Hematology 2008;70:145‐59. [DOI: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.12.005] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roberts 2016

- Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, Latchem S, Constanti M, Miller P. Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2016;75(3):552‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saragiotto 2016

- Saragiotto BT, Machado GC, Ferreira ML, Pinheiro MB, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG. Paracetamol for low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012230] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sheen 2002