Abstract

Background

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are characterised by impairments in communication and reciprocal social interaction. These impairments can impact on relationships with family members, augment stress and frustration, and contribute to behaviours that can be described as challenging. Family members of individuals with ASD can experience high rates of carer stress and burden, and poor parental efficacy. While there is evidence to suggest that individuals with ASD and family members derive benefit from psychological interventions designed to reduce stress and mental health morbidity, and enhance coping, most studies to date have targeted the needs of either individuals with ASD, or family members. We wanted to examine whether family (systemic) therapy, aimed at enhancing communication, relationships or coping, is effective for individuals with ASD and their wider family network.

Objectives

To evaluate the clinical effectiveness and acceptability of family therapy as a treatment to enhance communication or coping for individuals with ASD and their family members. If possible, we will also seek to establish the economic costs associated with family therapy for this clinical population.

Search methods

On 16 January 2017 we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, 10 other databases and three trials registers. We also handsearched reference lists of existing systematic reviews and contacted study authors in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs investigating the effectiveness of family therapy for young people or adults with ASD or family members, or both, delivered via any modality and for an unspecified duration, compared with either standard care, a wait‐list control, or an active intervention such as an alternative type of psychological therapy.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened each title and abstract and all full‐text reports retrieved. To enhance rigour, 25% of these were independently screened by a third author.

Main results

The search yielded 4809 records. Of these, we retrieved 37 full‐text reports for further scrutiny, which we subsequently excluded as they did not meet the review inclusion criteria, and identified one study awaiting classification.

Authors' conclusions

Few studies have examined the effectiveness of family therapy for ASD, and none of these are RCTs. Further research studies employing methodologically robust trial designs are needed to establish whether family therapy interventions are clinically beneficial for enhancing communication, strengthening relationships, augmenting coping and reducing mental health morbidity for individuals with ASD and family members.

Plain language summary

Family therapy for autism spectrum disorders

Review question

What is the evidence that family therapy can help to improve communication, strengthen relationships, and enhance coping, mental health and well‐being for people who have autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) or their family members, or both?

Background

People with ASD often experience difficulty with knowing how to communicate with others, and with developing and maintaining friendships and relationships. They can also find it difficult to manage changes to their routine. People with ASD tend to rely on family members, including parents and siblings, well into adulthood. Family members of people with ASD sometimes experience stress, anxiety and depression.

Several research studies have investigated the benefits of talking therapies for individuals with ASD or for family members. While study findings suggest that these therapies can improve communication and coping, and mental health and well‐being, outcomes are usually reported for the person with ASD or family members, but not both.

Family therapy is designed to help people within the family make sense of difficult situations, and help them work together to develop new ways of thinking about and managing these difficulties. It is important to find out if family therapy can be helpful for people with ASD and their relatives given that the core symptoms of ASD, and additional difficulties people can experience, often impact on the family unit.

We searched for all the available evidence, published or unpublished, up until 16 January 2017, which examined family therapy for ASD.

Study characteristics

While there have been a few studies investigating the benefits of family therapy interventions for ASD, none have compared family therapy with either no treatment, a group of people waiting to start treatment, or another type of psychological therapy. There is one study awaiting classification.

Quality of the evidence

There is limited high‐quality evidence available about whether family therapy is helpful for people with ASD or their family members. More research studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of family‐focused interventions to enhance communication, reduce stress and improve coping.

Background

Description of the condition

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are a cluster of childhood‐onset, neurodevelopmental conditions characterised by qualitative impairments in communication, reciprocal social interaction, and restricted and repetitive interests and behaviours (WHO 1992). There is substantial heterogeneity in the ASD symptom profile and clinical presentation; hence, diagnosis is often not made until late adolescence or adulthood (NICE 2012). Once thought to be fairly rare, current prevalence estimates indicate that ASD is relatively common, affecting at least 1% of the population (Brugha 2011).

The degree of impairment resulting from core ASD characteristics varies widely. Educational attainments are often poorer for younger people with ASD in comparison to typically developing peers (Levy 2011). Similarly, the adult ASD population experiences significant difficulty with gaining and sustaining meaningful employment (Howlin 2013; Mavranezouli 2014). A lack of peer and intimate relationships are frequently the norm (White 2009a), leading to diminished social opportunities beyond those that stem from the family network, social isolation and loneliness. Daily living and self‐sufficiency skills can also be impeded, and individuals with ASD often depend on ongoing support from family members well into adulthood (Gray 2014; Magiati 2014).

ASDs are commonly associated with learning disability and high rates of psychiatric comorbidity (Hofvander 2009; Joshi 2013; Simonoff 2008), including anxiety disorders (Van Steensel 2011; White 2009b), depression (Ghaziuddin 2002), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder traits (Taylor 2013), and more general "emotional and behavioural problems" (Maskey 2013). Comorbidities further compound difficulties across multiple domains of functioning and exacerbate reliance on family members as well as carer stress and burden (Cadman 2012).

The experiences and needs of family members of individuals with ASD have garnered increasing attention in recent years. Findings from epidemiological and genetic studies indicate that ASD is a highly heritable condition (Hallmayer 2011; Lichtenstein 2010; Lundström 2010). Also, studies have found that parents of people with ASD can present with higher levels of stress, distress, fatigue, anxiety, and depression symptoms than those reported for parents of typically developing or other clinical populations (Cadman 2012; Firth 2013; Giallo 2013; Hoefman 2014). Additionally, research findings suggest that carers can experience concerns about their parental efficacy and coping (Karst 2012), and that marital satisfaction can be affected (Hartley 2011). There has been some, albeit limited, research about siblings of individuals with ASD. Tentative study findings suggest that some siblings may experience slightly elevated levels of "behavioural problems" compared to non‐clinical populations (Hastings 2014), or features of anxiety (Shivers 2013). Sibling adjustment and relationships may be affected by the severity of ASD and associated symptoms (Petalas 2012; Rivers 2003). Siblings may also be expected to take on more household duties (e.g. chores), or more responsibility (e.g. informal caregiving) compared to the individual with ASD, although this is not a consistent finding across studies (Meirsschaut 2011).

Description of the intervention

Family therapy can be defined as a formal, psychotherapeutic intervention, which seeks to understand and enhance relationships, communication, and functioning between members of a family (Dallos 2010). While there are several types of family therapy, they are predominantly underpinned by systemic theories and share central tenets (Hayes 1991). First, it is proposed that various problems, such as mental health functioning or the development and maintenance of interpersonal relationships, are contextually bound (that is, they are likely to be predisposed and perpetuated by the context and system(s) within which they occur, rather than solely being attributed to the individual themselves) (Dallos 2010). Second, it is suggested that societal and cultural norms, values and expectations influence and shape familial beliefs and behaviours both collectively (that is, the intergenerational family unit) and individually, and that problems are best understood and addressed in terms of these influences. Third, it is hypothesised that the family unit and the relationships between family members are dynamic (that is, that the reactions and responses of one person affect those of others in the system, in a bi‐directional fashion, linearly and longitudinally). Fourth, families are said to develop ways of coping with periods of change and transition (e.g. births, marriages and bereavements), and illness or adversity, in order to maintain stability as a unit (Goldenberg 2012). Often these patterns of coping are adaptive and shared between all family members; yet, on occasion, individuals (within the family) may adopt distinct coping styles leading to communication and relationship difficulties. Finally, it is considered that there are commonalities in the ways that family members use language and narratives to converse and make sense of their own and others’ experiences but also subtle differences, which, in turn, may lead to or exacerbate ambiguity, misinterpretation or disagreements.

Family therapists use a range of interventions (Dallos 2010), including psychoeducation; development of genograms to map out cultural, resilience or other familial patterns (Butler 2008); narrative techniques (e.g. to explore language, meanings and attributions) (Carr 1998); and the use of particular questioning styles (e.g. circular and reflexive questions to enhance the breadth and depth of discussion) (Hayes 1991). In clinical practice, individuals presenting for family therapy may be part of the same family or part of the wider friendship group. Individuals are encouraged to decide for themselves who can and will engage in treatment, and the configuration of those attending may vary from session to session. The duration of therapy can be several weeks to several months. Choices about the number of sessions to offer are largely dependent on the service model and constraints, familial presenting needs and the therapist’s theoretical stance.

How the intervention might work

Family therapy for ASD can be hypothesised to work in several ways (Goepfert 2015; Helps 2016; Ramisch 2013; Solomon 2012). Individuals with ASD and family members can be supported to understand and make sense of the diagnosis (e.g. through the use of psychoeducation). Discussion can be facilitated about preferences for using different terminology to describe the core symptoms (e.g. autism spectrum ‘disorder’ or autism spectrum ‘condition’) and the narratives and meanings that arise from this for individuals and the family unit collectively. The impact of core characteristics (e.g. engagement in routines or impairments in socioemotional reciprocity such as a lack of empathy) can be explored with a view to reducing feelings of frustration or annoyance. Interventions can encourage discussion about broad factors and familial patterns or responses that may contribute to difficulties with communication and relationships or challenging behaviour, and support the identification of strategies to promote cohesion within the system. Family therapy can also encourage open dialogue between carers (e.g. about potential guilt or feelings of stress or worry), and, in turn, strategies can be developed to enhance marital relationships, resilience and coping, and positive parental mental health. Family therapy also provides a supportive therapeutic space for siblings to explore their concerns or unanswered questions (e.g. about heredity factors or their current and potential prospective role as a carer).

Why it is important to do this review

ASDs are common, lifelong disorders characterised by overt and subtle qualitative impairments in communication, social interaction and relatedness, and preferences for engaging in restricted interests and repetitive behaviours (WHO 1992). Difficulties with tolerating uncertainty, ambiguity, and change within and beyond the immediate environment are additional hallmark characteristics (APA 2013). Core ASD symptoms can impact significantly on daily social and occupational functioning during childhood and adulthood. Individuals with ASD may find it difficult to initiate and sustain interactions with others despite the desire for relationships (and increased social opportunities). Also, symptoms of ASD typically impact others in the family (Hoefman 2014). Parents (carers) and siblings often must accommodate restricted interests and adherence to seemingly non‐functional routines. Inherent difficulties with communication and interaction can adversely affect relationships with, and between, family members. The need to provide intensive and ongoing support to individuals with ASD can incur stress, anxiety and depression in carers, as well as poor perceived parental efficacy and coping (Karst 2012).

There is no cure for ASD per se, and the heterogeneity of the disorder negates the use of monotherapy. Instead, the more parsimonious approach is to develop combinations of interventions that 1) reduce or ameliorate the effect and impact of core ASD symptoms, and 2) support individuals and others around them to enhance their repertoire of skills (Smith 2014; Woodman 2015). Further, interventions are needed across the lifespan to address the needs of children as well as adults with ASD. There is promising evidence for the use of psychological interventions for individuals with ASD, such as behavioural and cognitive‐behavioural (Lang 2010; Spain 2015a; Sukhodolsky 2013), social cognition (Fletcher‐Watson 2014), and skills‐based interventions (Reichow 2013; Spain 2015b), but a limitation to these approaches is that they do not explicitly address relationship and communication issues between family members, nor do they seek to enhance familial coping strategies or resilience factors. Similarly, a recent review has highlighted the potential effectiveness of parent training for ASD (Oono 2013), but this approach encourages parents to take on a more facilitative role, rather than specifically targeting their (potential) concurrent needs and the bi‐directional relationship between individuals. Conversely, family therapy is a more inclusive intervention and has been found to be effective for different clinical populations (Carr 2009). Whether the structure or content of family therapy for individuals with ASD requires adaptation (as is the case for other psychological therapies), for example to accommodate the impact of inherent impairments, is not wholly clear. Undertaking a systematic review of the empirical data is important in order to:

ascertain the potential effectiveness and acceptability of formal family therapy work for individuals with ASD;

establish whether there are integral features of these approaches that are associated with improved outcomes; and

consider how best interventions can be tailored to the specific lifelong needs of this clinical population and their family members.

Objectives

To evaluate the clinical effectiveness and acceptability of family therapy as a treatment to enhance communication or coping for individuals with ASD and their family members. If possible, we will also seek to establish the economic costs associated with family therapy for this clinical population.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (in which participants were allocated by alternate allocation, for example according to days of the week). We excluded cross‐over trials and studies employing non‐RCT designs (such as case studies or case series), due to the methodological limitations these can incur.

Types of participants

Families that have at least one person — child or adolescent (aged 17 years and under) or adult (aged 18 years and over) — diagnosed with an ASD.

We defined ASD according to clinical criteria of either the International Classification of Diseases (WHO 1992), or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (APA 2013), and ideally (but not necessarily) diagnosed using standardised methods of assessment (e.g. the Autism Diagnostic Interview ‐ Revised (Lord 1994), or the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Lord 2000)).

We defined family members as individuals from multi‐generations (parents, grandparents, siblings, children, or spouses), either biologically related to the individual with ASD, or related through marriage or cohabitation. We also included non‐professional carers (e.g. individuals providing foster or respite care) and significant others such as friends.

We included studies that described interventions delivered to participants residing in the same dwelling, or interventions offered to family members living separately.

We included studies in which participants had a comorbidity or were receiving other treatments concurrently to the family therapy, although the intention was to clarify this level of detail from reports or by contacting trial authors.

Types of interventions

Family therapy

We included family therapy interventions delivered by at least one suitably qualified clinician, derived from systemic theories, and specifically focusing on understanding, enhancing and improving aspects of relationships between individuals with ASD and at least one family member; or between two or more members of the family of an individual with ASD (e.g. parents, or parents and siblings). We included the following modalities of family therapy: systemic therapy; structural family therapy; strategic family therapy; Milan approaches; solution‐focused therapy; narrative therapy; and behavioural family therapy. The intervention had to have been offered either face‐to‐face or via web‐based real‐time sessions. We excluded studies that described pure bibliotherapy, psychoeducation or parent training techniques. There was no stipulation regarding the number or duration of sessions delivered.

Control condition

We included four main types of comparator interventions.

No treatment.

Provision of standard clinical care (i.e. treatment as usual).

A wait‐list control (e.g. a delayed‐start intervention).

An active comparator (e.g. an alternative psychological intervention such as applied behavioural analysis or cognitive behavioural therapy).

Types of outcome measures

We identified primary and secondary outcomes for individuals with ASD and family members. We included outcome measures that generated either dichotomous or continuous data. To be eligible for inclusion, outcome measures needed to be standardised and validated. While measures may not necessarily have been specifically validated for use with the ASDs population, many intervention studies that include participants with ASD utilise measures (e.g. self‐report questionnaires) that have been validated in non‐ASD samples (Lang 2010; Reichow 2013; Spain 2015a; Spain 2015b). The intention was to describe the psychometric properties of outcome measures, when possible, and highlight whether there are indicative, normative thresholds (that is, cut‐off scores) for ASD samples.

Outcome measures could have been completed by individuals with ASD, family members, or via objective (clinician‐administered) instruments. Outcome measures could have been completed at different time points, including postintervention or at follow‐up, or relating to short‐term changes (such as attributions about coping or satisfaction with the intervention), and longer‐term outcomes (such as direct and indirect costs).

Primary outcomes

Quality or quantity of social interaction and communication (e.g. Social Responsiveness Scale by Constantino 2003; Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule by Lord 2000).

Mental health morbidity, including stress, anxiety or depression (e.g. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale by Zigmond 1983).

Quality of life (e.g. EQ‐5D by Szenda 2007), including quality of relationships with family members (e.g. Family Questionnaire by Wiedemann 2002).

Adverse effects or events (e.g. increased mental health morbidities, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond 1983); or an increase in challenging behaviour).

Secondary outcomes

Confidence in, or attributions about, coping (e.g. Attributional Style Questionnaire by Seligman 1984).

Satisfaction with treatment (e.g. Client Satisfaction Questionnaire by Attkisson 1982).

Dropout from treatment.

Health economic outcomes, including direct costs (e.g. treatment costs) and indirect costs (e.g. use of clinical services or work absence due to stress).

Search methods for identification of studies

We used a search strategy that combined two concepts: the condition (ASD) AND intervention (family therapy). We did not limit the search by language, date, or publication status.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases and trial registers between 22 October and 4 November 2015 and again in January 2017:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 11) in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 18 January 2017);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to December Week 1 2016);

MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print (16 January 2017);

MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (16 January 2017);

Embase Ovid (1974 to 2017 Week 03);

CINAHL Plus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 17 January 2017);

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2017, Issue 1) part of the Cochrane Library (searched 18 January 2017);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; 2015, Issue 2) part of the Cochrane Library (searched 18 January 2017);

ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center; 1966 to 17 January 2017);

PsycINFO Ovid (1967 to January Week 2 2017);

Sociological Abstracts ProQuest (1952 to 18 January 2017);

Dissertation Abstracts International ProQuest (1743 to 16 January 2017);

AutismData (autism.org.uk/autismdata; searched 18 January 2017);

UK Clinical Trials Gateway (UKCTG; ukctg.nihr.ac.uk; searched 18 January 2017); replaces UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio.

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 18 January 2017);

World Health Organisation International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch/default.asp; searched 18 January 2017).

The exact strategy for each database is reported in Appendix 1. See Appendix 2 for a detailed summary of the searches to date.

Searching other resources

We also undertook additional searches as follows: 1) we handsearched the reference lists of 10 review papers (Banda 2015; Cridland 2014; Dababnah 2016; Da Paz 2017; Gingerich 2013; Goepfert 2015; Karst 2012; Kaslow 2012; Ramisch 2013; Wainer 2016); and 2) we contacted a number of clinicians, including researchers who have undertaken studies in the field, to ask if they knew of any studies not already identified by the searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Selection of studies involved several steps. We initially imported all citations retrieved from the searches into EndNote (EndNote X7). After removing duplicates, DS and JS independently screened the list of titles and abstracts for relevance. Next, DS and JS inspected full reports of studies that appeared relevant or for which more information was needed. They then independently assessed each text for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria outlined above (Criteria for considering studies for this review). To enhance reliability and rigour, EP independently reviewed a random 25% of the total sample of all titles and abstracts obtained, and a random 25% of all full‐text reports retrieved. There were no disputes about the screening and inspection of reports. We recorded our decisions in a study flow diagram (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

No studies met the inclusion criteria for this review (Criteria for considering studies for this review).

Please see the protocol (Spain 2015c) and Table 1 for more information on methods archived for use in future updates of this review.

1. Unused methods sections.

| Unused methods | Description of methods |

| Data extraction and management | The data extraction form will include subheadings relating to the following areas.

We will attempt to separate the outcomes and results between sites for any multi‐centre studies. In the event that data described appear ambiguous for any of the reports, we will contact the authors for clarification. If we are unable to liaise with report authors, we will document this within the review, and the review team will discuss the discrepancies. For any non‐English language studies, we will endeavour to arrange for report translation. |

| Assessment of risk of bias in included studies | DS and JS will independently assess the risk of bias of all included studies across seven domains: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and trial staff; blinding of outcome assessments; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and any other potential sources of bias. For each included study, we will assign each of these domains one of three ratings: high risk of bias, low risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias. We have detailed criteria for rating various domains of bias below, with examples drawn from Chapter 8.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and research personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective reporting

Other sources of bias

We will obtain a third opinion from EP, MF or FH should there be disagreement about the 'Risk of bias' assessment or a lack of consensus about any of the individual domains per study or in terms of the overall appraisal of the trial. We will also attempt to contact report authors to provide clarification about aspects of the trial, as needed. |

| 'Summary of findings' tables | We will import data from Review Manager (Review Manager 2014), into GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro GDT), and use this software to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables will provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of the body of evidence from the studies included in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on outcomes rated as relevant to patient care and decision making.

We will employ the GRADE approach to assess the quality of evidence (Schünemann 2011), using the following ratings: high quality (RCTs or quasi‐RCTs with a very low risk of bias), moderate quality (RCTs or quasi‐RCTs with some evidence of risk of bias such as inadequate allocation concealment), low and very low quality (RCTs or quasi‐RCTs that have significant threats to internal study validity such as failure to adequately randomise participants, lack of blinding of outcome assessors, or selective outcome reporting) (Schünemann 2011, Table 12.2.a). We will include the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

|

| Measures of treatment effect |

Dichotomous data For dichotomous outcomes, such as the presence or absence of challenging behaviour(s), we will use the Mantel‐Haenszel method for computing the pooled risk ratio (RR) (Mantel 1959). We will use the RR in meta‐analyses, rather than the odds ratio (OR), because the OR can be susceptible to misinterpretation, which can lead to overestimation of the benefits and harms of the intervention (Deeks 2011, Section 9.4.4.4). We will report the RR with 95% CIs. Continuous data When different measures are used, we will calculate the standardised mean difference and 95% CI. We will calculate the mean difference and 95% CI when all outcomes are measured using the same scale in the same way. |

| Unit of analysis issues |

Cluster trials In cluster trials, the independence of individuals cannot be assumed (Higgins 2011b). As we are examining the effectiveness of an intervention for both individuals and family members, we may identify cluster‐randomised trials. If clustering has been incorporated into the analyses of primary studies, we plan to present these data as if from a non‐cluster‐randomised study, but adjust for the clustering effect. We will contact study authors for more information if needed. If we identify cluster trials that have been analysed using incorrect statistical methods (i.e. not taking the clustering into account), we will contact study authors to request individual participant data so that we may calculate an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC). If we are unable to obtain this information, we will adjust sample sizes using an estimate of the ICC from the trial or from a trial of a similar population, with advice from a statistician, and use this to re‐analyse the data. In the event that we are unable to adjust for incorrect statistical methods used by the cluster trials, and therefore cannot estimate the ICC with any a degree of confidence, we will exclude the trial (Higgins 2011b). We will investigate the robustness of our results by conducting sensitivity analyses, for example, to explore the impact of different types of cluster‐randomisation units (such as families, health practitioners) (Higgins 2011b). We will also compare the results with and without cluster trials that have not been analysed correctly by the trialists (where the ICC is estimated from other trials for the adjustment of cluster effect) (see Sensitivity analysis). Cross‐over trials Due to the issue of carry‐over, that is, whereby the effectiveness of a second intervention may be mediated by the first intervention, we will exclude cross‐over trials. Multiple comparisons Where a trial involves more than two treatment (or comparator) arms, we will first assess which intervention (or comparator) groups are relevant to our review. We will use data from the arms of the trial that are relevant to the review objectives, but present all intervention groups in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables, providing a detailed description of why we have selected particular groups and excluded others. In the event that studies have more than two intervention groups and a control group that are relevant to the review, we will split the control group data proportionately to the other two groups. Repeated measures When a trial reports outcome data obtained at more than one time point, we will conduct analyses separately for each time point (e.g. postintervention and at follow‐up, if follow‐up is specified by the trialist). |

| Dealing with missing data | We will consider the possible impact of missing data on the results of the review. Data may be missing either because (1) they have been insufficiently or inadequately reported, or (2) due to dropout or attrition. In the event of insufficient or inadequate reporting, we will first try to obtain any missing data from the trial authors, including unreported data (e.g. group means and SDs), details of dropouts, and interventions provided. We will describe the missing data in the 'Risk of bias' table. In either case outlined above, and when we cannot obtain data, we will conduct analyses using ITT principles. For dichotomous outcomes (those not deemed to be missing at random), we will impute the outcomes for the missing participants using both the most optimistic (i.e. assuming participants with missing data improve) and the most pessimistic (i.e. assuming participants with missing data deteriorate) scenarios. When data are missing for continuous outcomes (e.g. data pertaining to means or SD), we will attempt to calculate them based on the standard errors, CIs, and t values, according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c). If this information is missing, and we are unable to obtain it from trial authors, we will report it as missing data in the review. We will also conduct a sensitivity analysis to compare the results from the ITT analysis with the imputation and ‘available case’ analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). If these analyses yield similar results in terms of the effects of treatment, we will present the results of the available case analyses. |

| Assessment of heterogeneity | Within each comparison, we will first assess clinical heterogeneity (e.g. variability in active and comparator interventions, participant characteristics, or outcome measures used) and methodological heterogeneity (e.g. variability in study design, including differences in the nature of the randomisation unit and the size of cluster randomised; and risk of bias, which we will assess according to the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011)). If there is clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we will extract and document all of these characteristics onto the data extraction form and synthesise the results narratively. We will then assess statistical heterogeneity using the I² and Chi² statistics, and by visually inspecting the forest plots. If we identify a substantial level of heterogeneity in trials (e.g. the I² is more than 30% to 60%, the P value is less than 0.10 in the Chi² test for heterogeneity, or there is a different direction of the effects), we will conduct prespecified subgroup analyses (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). |

| Assessment of reporting biases | We will assess reporting biases, including (multiple) publication, selective reporting, outcome and language biases (Sterne 2011, Table 10.1.a). First, we will try to locate protocols of included trials. If the protocol is available, we will compare outcomes documented in the protocol and the published report. If the protocol is not available, we will compare outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with the reported results. In addition, we will create funnel plots to investigate the possibility of publication bias and other small‐study effects when there is a sufficient number of trials (10 or more). While funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases, there is some concern that tests for funnel plot asymmetry have limited power to detect small‐study effects, particularly when there are fewer than 10 studies, or when all studies are of a similar sample size (Sterne 2011). In the event that funnel plots are possible, we will produce them and seek statistical advice in their interpretation. |

| Data synthesis | We will conduct random‐effects meta‐analyses to produce the average effect size of the intervention across trials. A random‐effects model is considered more appropriate than a fixed‐effect model because the population and setting of trials are likely to be different, and therefore the effects are also likely to be different (Deeks 2011). |

| Subgroup analysis and assessment of heterogeneity | Depending on the sample size and heterogeneity of study populations, we propose to undertake subgroup analyses as follows:

To limit the risk of multiple comparisons, we will conduct subgroup analyses on primary outcomes only. |

| Sensitivity analysis | We will undertake sensitivity analyses to evaluate the impact of excluding trials (or trial data) that are judged to have a high risk of bias (e.g. in terms of the domains of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, or outcome reporting). We will also undertake sensitivity analyses to assess the potential impact of missing outcome data. |

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; IQ: intelligence quotient; RCTs: randomised controlled trials; SD: standard deviation.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

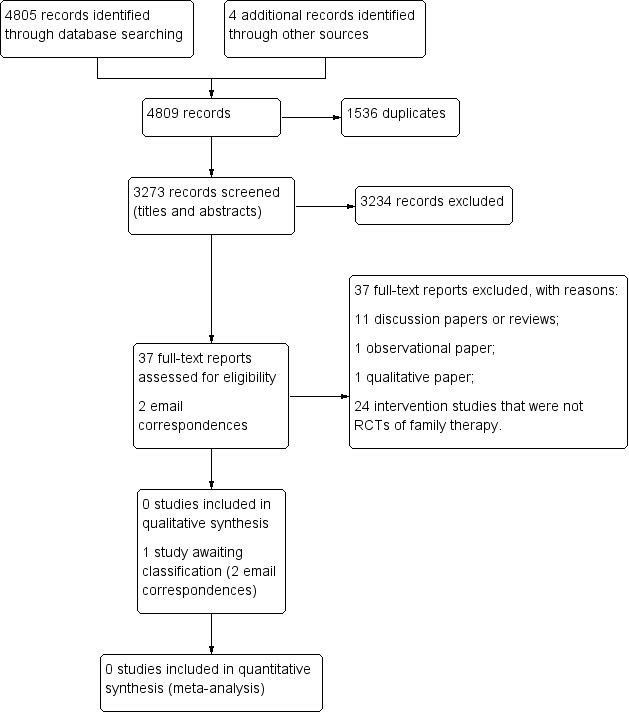

Please see Figure 1 for a flow diagram of the selection process.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Our searches yielded 4805 database records (Electronic searches), and four additional records from other sources (Searching other resources). We removed 1536 duplicates and reviewed 3273 records for eligibility (Criteria for considering studies for this review). Two review authors (DS, JS) independently screened all titles and abstracts. A third author (EP) screened 800 titles and abstracts (25%) independently to enhance rigour. We excluded 3234 records, as none of these pertained to RCTs of family therapy for people with ASD.

We retrieved a total of 37 full‐text reports for further evaluation. Thirty‐four reports were written in English, one was written in Chinese (Chen 2006), one in Japanese (Abe 2014), and one in German (Goll‐Kopka 2009). None of these described RCTs of family therapy and all were excluded (see Excluded studies). One excluded study, Wagner 2014, made reference to another, potentially relevant study. We contacted the author on two occasions but no further information was available at this time, therefore we classified this as awaiting classification (Spain 2017 [pers comm]).

Included studies

None of the reports retrieved met the inclusion criteria for this review (Criteria for considering studies for this review).

Excluded studies

We excluded 37 reports. We excluded 11 discussion papers or reviews (Affleck 1982; Alonim 2004; Brockman 2016; Coleman 2015; Heller 2015; Helps 2016; Johnson 2012; Lordi 1964; Pickard 2017; Smock Jordan 2016; Wagner 2014), one observational report (Altiere 2009), one qualitative study (Coogle 2016), and 24 intervention studies that were not RCTs of family therapy (Abe 2014; Aerts 2011; Allen 1980; Alquraini 2015; Bennett 1983; Bennett 1986; Casenhiser 2011; Chen 2006; Chou 1992; Clancy 1972; Davis 1991; George 1988; Drahota 2008; Estreicher 1982; Goll‐Kopka 2009; Keen 2010; NCT01919970; Pillay 2010; Roux 2013; Shank 1991; Siller 2013; Solomon 2008; Wang 2008; Whittingham 2009).

See Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Risk of bias in included studies

Given that no studies met the review inclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review), we were unable to assess risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

It was not possible to establish intervention effectiveness, given the absence of data.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We sought to establish the clinical and cost effectiveness of family therapy for individuals with ASD. Despite an extensive search, no RCTs met the a priori review inclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review), implying a gap in the literature. One study is awaiting classification as no further information is available at this time.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We were unable to assess completeness and applicability of evidence as no studies were included in this review.

Quality of the evidence

We were unable to assess the quality of the evidence as no studies were included in this review.

Potential biases in the review process

We consider that our search was rigorous and comprehensive. We conducted searches in 13 databases, including seeking unpublished studies such as those described in dissertations and the grey literature. We also handsearched the reference lists of a number of systematic and literature reviews. Finally, we contacted a couple of study authors to ascertain whether they were aware of trial data that may be eligible for inclusion in this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No other systematic reviews focusing on RCTs of family therapy or systemic therapy for ASD were retrieved by our search. We identified (but excluded) a few non‐randomised intervention studies that incorporated elements of systemic therapy for family members of individuals with ASD (e.g. George 1988; Goll‐Kopka 2009; Wagner 2014). Evidence from these studies suggests that knowledge and understanding of the core disorder (i.e. ASD), and coping styles may be improved postintervention, albeit that use of less rigorous study designs means that results should be interpreted with a degree of caution.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In spite of uncertainty about effects, it may be that family therapy is deemed clinically appropriate, either in conjunction with other prescribed treatments or as a stand‐alone intervention. Decisions to use family therapy should be made in consultation with suitably qualified multidisciplinary professionals. Also, the use of family or systemic therapies should be informed by best practice guidance for clinical work with this population (NICE 2012).

Implications for research.

There are several implications for research. Building on the literature to date, there is a need for further intervention studies that employ methodologically rigorous trial designs (i.e. RCTs). This may include studies that examine the clinical utility and effectiveness of psychoeducation for family members, couples therapy to strengthen relationships and coping when one parent has ASD, and family or systemic therapy for parents, siblings, grandparents and children of people with ASD, and dyads (e.g. members of two generations and young people or adults with ASD and members of the immediate and extended family). Whether particular systemic approaches glean more favourable outcomes is yet to be established, but this warrants further investigation. Similarly, consideration of treatment mediators and moderators would prove beneficial. As a secondary objective, intervention studies should undertake process evaluations to establish satisfaction and acceptability of these interventions for family members.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems editorial staff, in particular Geraldine Macdonald, Joanne Wilson and Margaret Anderson; the reviewers; and Johanna McMahon for support with review administration.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library

#1[mh "child development disorders, pervasive"] #2[mh ^"Developmental Disabilities"] #3pervasive development* disorder* #4(pervasive near/3 child*) #5(PDD or PDDs or PDD‐NOS or ASD or ASDs) #6autis* #7asperger* #8kanner* #9childhood near/1 schizophreni* #10{or #1‐#9} #11[mh "family therapy"] #12[mh "group therapy"] #13[mh "psychotherapy, group"] #14[mh "couples therapy"] #15[mh "marital therapy"] #16(systemic* near/3 psychotherap*) #17(systemic* near/3 psycho‐therap*) #18(systemic* near/3 famil*) #19(famil* near/3 (intervention* or therap* or treat* or program*)) 4 #20(famil* near/3 (psychotherap* or psychoeducation* or psycho next education* or psycho next therap*)) 3 #21((marriage or marital or couple*) near/3 therap*) #22(famil* near/1 (involv* or integrat* or participat* or focus*)) #23(psychodynamic or psycho next dynamic) #24(group* near/3 psychotherap*) #25(group* near/3 psycho next therap*) #26(systemic next therap*) #27(solution next focus*) #28(narrative near/3 therap*) #29{or #11‐#28} #30#10 and #29 in Trials

MEDLINE Ovid

1 exp child development disorders, pervasive/ 2 Developmental Disabilities/ 3 pervasive development$ disorder$.tw. 4 (pervasive adj3 child$).tw. 5 (PDD or PDDs or PDD‐NOS or ASD or ASDs).tw. 6 autis$.tw. 7 asperger$.tw. 8 kanner$.tw. 9 childhood schizophreni$.tw. 10 or/1‐9 11 family therapy/ 12 group therapy/ 13 psychotherapy, group/ 14 couples therapy/ 15 marital therapy/ 16 (systemic$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 17 (systemic$ adj3 psycho‐therap$).tw. 18 (systemic$ adj3 famil$).tw. 19 (famil$ adj3 (intervention$ or therap$ or treat$ or program$)).tw. 20 (famil$ adj3 (psychotherap$ or psychoeducation$ or psycho‐education$ or psycho‐therap$)).tw. 21 ((marriage or marital or couple$) adj3 therap$).tw. 22 (famil$ adj1 (involv$ or integrat$ or participat$ or focus$)).tw. 23 (psychodynamic or psycho‐dynamic).tw. 24 (group$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 25 (group$ adj3 psycho‐therap$).tw. 26 systemic therap$.tw. 27 solution focus$.tw. 28 (narrative adj1 therap$).tw. 29 or/11‐28 30 10 and 29

MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print

1 pervasive development$ disorder$.tw. 2 (pervasive adj3 child$).tw. 3 (PDD or PDDs or PDD‐NOS or ASD or ASDs).tw. 4 autis$.tw. 5 asperger$.tw. 6 kanner$.tw. 7 childhood schizophrenia.tw. 8 or/1‐7 9 (systemic$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 10 (systemic$ adj3 psycho‐therap$).tw. 11 (systemic$ adj3 famil$).tw. 12 (famil$ adj3 (intervention$ or therap$ or treat$ or program$)).tw. 13 (famil$ adj3 (psychotherap$ or psychoeducation$ or psycho‐education$ or psycho‐therap$)).tw. 14 (famil$ adj1 (involv$ or integrat$ or participat$ or focus$)).tw. 15 ((marriage or marital or couple$) adj3 therap$).tw. 16 (psychodynamic or psycho‐dynamic).tw. 17 (group$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 18 (group$ adj3 psycho therap$).tw. 19 systemic therap$.tw. 20 solution focus$.tw. 21 (narrative adj1 therap$).tw. 22 or/9‐21 23 8 and 22

MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations

1 pervasive development$ disorder$.tw. 2 (pervasive adj3 child$).tw. 3 (PDD or PDDs or PDD‐NOS or ASD or ASDs).tw. 4 autis$.tw. 5 asperger$.tw. 6 kanner$.tw. 7 childhood schizophrenia.tw. 8 or/1‐7 9 (systemic$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 10 (systemic$ adj3 psycho‐therap$).tw. 11 (systemic$ adj3 famil$).tw. 12 (famil$ adj3 (intervention$ or therap$ or treat$ or program$)).tw. 13 (famil$ adj3 (psychotherap$ or psychoeducation$ or psycho‐education$ or psycho‐therap$)).tw. 14 (famil$ adj1 (involv$ or integrat$ or participat$ or focus$)).tw. 15 ((marriage or marital or couple$) adj3 therap$).tw. 16 (psychodynamic or psycho‐dynamic).tw. 17 (group$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 18 (group$ adj3 psycho therap$).tw. 19 systemic therap$.tw. 20 solution focus$.tw. 21 (narrative adj1 therap$).tw. 22 or/9‐21 23 8 and 22

Embase OVID

1 exp autism/ 2 pervasive development$ disorder$.tw. 3 (PDD or PDDs or ASD or ASDs).tw. 4 autis$.tw. 5 asperger$.tw. 6 kanner$.tw. 7 childhood schizophreni$.tw. 8 Rett$.tw. 9 (pervasive adj3 child$).tw. 10 or/1‐9 11 family therapy/ 12 group therapy/ 13 marital therapy/ 14 (systemic$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 15 (systemic$ adj3 psycho‐therap$).tw. 16 (systemic$ adj3 famil$).tw. 17 (famil$ adj3 (intervention$ or therap$ or treat$ or program$)).tw. 18 (famil$ adj3 (psychotherap$ or psychoeducation$ or psycho‐education$ or psycho‐therap$)).tw. 19 ((marriage or marital or couple$) adj3 therap$).tw. 20 (famil$ adj1 (involv$ or integrat$ or participat$ or focus$)).tw. 21 (psychodynamic or psycho‐dynamic).tw. 22 (group$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 23 (group$ adj3 psycho‐therap$).tw. 24 systemic therap$.tw. 25 solution focus$.tw. 26 (narrative adj1 therap$).tw. 27 or/11‐26 28 10 and 27

CINAHLPlus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature)

S27 S9 AND S26 S26 S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 S25 (narrative N1 therap*) S24 solution focus* S23 systemic therap* S22 (group* N3 (psychotherap* or psycho‐therap*) ) S21 (psychodynamic or psycho‐dynamic) S20 (famil* N1 (involv* or integrat* or participat* or focus*)) S19 ((marriage or marital or couple*) N3 therap*) S18 (famil* N3 (psychotherap* or psychoeducation* or psycho‐education*or psycho‐therap*)) S17 (famil* N3 (intervention* or therap* or treat* or program*)) S16 (systemic* N3 famil*) S15 (systemic* N3 psycho‐therap*) S14 (systemic* N3 psychotherap*) S13 (MH "Couples Counseling") S12 (MH "Psychotherapy, Group") S11 (MH "Family Therapy") S10 (MH "Family Systems Theory") OR (MH "Family Services") S9 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 S8 (MH "Developmental Disabilities") S7 childhood schizophren* S6 Kanner* S5 Rett* S4 Asperger* S3 (autis* or ASD or ASDs) S2 (pervasive development* disorder* or PDD or PDDs) S1 (MH "Child Development Disorders, Pervasive+")

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) part of the Cochrane Library

#1[mh "child development disorders, pervasive"] #2[mh ^"Developmental Disabilities"] #3"pervasive development* disorder*":ti,ab #4(pervasive near/3 child*):ti,ab #5autis* :ti,ab #6asperger*:ti,ab #7kanner*:ti,ab #8{or #1‐#7} #9[mh "family therapy"] #10[mh "group therapy"] #11[mh "psychotherapy, group"] #12[mh "couples therapy"] #13[mh "marital therapy"] #14(systemic* near/3 psychotherap*):ti,ab #15(systemic* near/3 psycho‐therap*):ti,ab #16(systemic* near/3 famil*):ti,ab #17(famil* near/3 (intervention* or therap* or treat* or program*)):ti,ab #18(famil* near/3 (psychotherap* or psychoeducation* or psycho next education* or psycho next therap*)):ti,ab #19((marriage or marital or couple*) near/3 therap*):ti,ab #20(famil* near/1 (involv* or integrat* or participat* or focus*)):ti,ab #21(psychodynamic or psycho next dynamic):ti,ab #22(group* near/3 psychotherap*):ti,ab #23(group* near/3 psycho next therap*):ti,ab #24("systemic therap*"):ti,ab #25("solution focus*"):ti,ab #26(narrative near/1 therap*):ti,ab #27{or #9‐#26} #28#8 and #27

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) part of the Cochrane Library

#1[mh "child development disorders, pervasive"] #2[mh ^"Developmental Disabilities"] #3"pervasive development* disorder*" #4(pervasive near/3 child*) #5autism or autistic #6asperger* #7kanner*: #8{or #1‐#7} #9[mh "family therapy"] #10[mh "group therapy"] #11[mh "psychotherapy, group"] #12[mh "couples therapy"] #13[mh "marital therapy"] #14(systemic* near/3 psychotherap*) #15(systemic* near/3 psycho‐therap*) #16(systemic* near/3 famil*): #17(famil* near/3 (intervention* or therap* or treat* or program*)) #18(famil* near/3 (psychotherap* or psychoeducation* or psycho next education* or psycho next therap*)) #19((marriage or marital or couple*) near/3 therap*) #20(famil* near/1 (involv* or integrat* or participat* or focus*)) #21(psychodynamic or psycho next dynamic) #22(group* near/3 psychotherap*) #23(group* near/3 psycho next therap*) #24("systemic therap*") #25("solution focus*"): #26(narrative near/1 therap*) #27{or #9‐#26} #28#8 and #27

ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center)

S27 S9 AND S26 S26 S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 S25 (narrative N1 therap*) S24 "solution focus*" S23 "systemic therap*" S22 (group* N3 (psychotherap* or psycho‐therap*)) S21 (psychodynamic or psycho‐dynamic) S20 TI(famil* N1 (involv* or integrat* or participat* or focus*)) OR AB(famil* N1 (involv* or integrat* or participat* or focus*) S19 TI ((marriage or marital or couple*) N3 therap*) OR AB((marriage or marital or couple*) N3 therap*) Search modes ‐ Boolean/Phrase S18 TI(famil* N3 (psychotherap* or psychoeducation* or psycho‐education* or psycho‐therap*))OR AB(famil* N3 (psychotherap* or psychoeducation* or psycho‐education* or psycho‐therap*)) S17 TI(famil* N3 (intervention* or therap* or treat* or program*)) OR AB(famil* N3 (intervention* or therap* or treat* or program*)) S16 (systemic* N3 famil*) S15 (systemic* N3 psycho‐therap*) S14 (systemic* N3 psycho‐therap*) S13 (systemic* N3 psychotherap*) S12 DE "Marriage Counseling" S11 DE "Group Counseling" OR DE "Group Therapy" S10 DE "Family Counseling" OR DE "Family Involvement" OR DE "Family Programs" S9 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 S8 childhood schizophren* S7 Kanner* S6 Rett* S5 Asperger* S4 (autis* or ASD or ASDs) S3 (pervasive development* disorder* or PDD or PDDs) S2 DE "Pervasive Developmental Disorders" OR DE "Asperger Syndrome" OR DE "Autism" S1 DE "Developmental Disabilities"

PsycINFO (Ovid)

1 exp pervasive developmental disorders/ 2 Developmental disabilities/ 3 pervasive development$ disorder$.tw. 4 (pervasive adj3 child$).tw. 5 autis$.tw. 6 asperger$.tw. 7 (autis$ or ASD or ASDs).tw. 8 Rett$.tw. 9 Kanner$.tw. 10 (PDD or PDDs or PDD‐NOS).tw. 11 childhood schizophreni$.tw. 12 or/1‐11 13 exp family therapy/ 14 family intervention/ 15 group psychotherapy/ 16 conjoint therapy/ 17 couples therapy/ 18 marriage counseling/ 19 (systemic$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 20 (systemic$ adj3 psycho‐therap$).tw. 21 (systemic$ adj3 famil$).tw. 22 (famil$ adj3 (intervention$ or therap$ or treat$ or program$)).tw. 23 (famil$ adj3 (psychotherap$ or psychoeducation$ or psycho‐education$ or psycho‐therap$)).tw. 24 ((marriage or marital or couple$) adj3 therap$).tw. 25 (famil$ adj1 (involv$ or integrat$ or participat$ or focus$)).tw. 26 (psychodynamic or psycho‐dynamic).tw. 27 (group$ adj3 psychotherap$).tw. 28 (group$ adj3 psycho‐therap$).tw. 29 systemic therap$.tw. 30 solution focus$.tw. 31 (narrative adj1 therap$).tw. 32 or/13‐31 33 12 and 32

Sociological Abstracts ProQuest

SU.EXACT("Autism") OR autis* or asperger* or kanner* or Rett* or pervasive N3 disorder* or pervasive N3 child* OR PDD or PDDs or PDD‐NOS or ASD or ASDs) AND ((famil* N/3 (intervention* or therap* or treat* or program*)) or (famil* N/3 (psychotherap* or psychoeducation* or "psycho education*" or "psycho therap*")) or (systemic* N/3 psychotherap*) or (systemic* N/3 "psycho‐ therap*") or (famil* N/1 (involv* or integrat* or participat* or focus*)) OR (group* N/3 psychotherap*) or systemic therap* or (group* N/3 psychotherap*) or (group* N/3 ("psycho‐therap*" or psychoeducation* or "psycho education*" or "psycho therap*")))

Dissertation Abstracts International ProQuest

(ab(child developmental disorders) OR ab((pervasive developmental disorders OR developmental disabilit$)) OR ab((pervasive development$ disorder$ OR pervasive adj3 child$)) OR ab((PDD OR PDDs OR PDD‐NOS OR ASD OR ASDs OR autis$)) OR ab((asperger$ OR kanner$)) OR ab(childhood schizophrenia)) AND (ab(family therapy) OR ab((group therapy OR group psychotherapy)) OR ab((couples therapy OR marital therapy)) OR ab((systemic$ adj3 psychotherap$ OR systemic$ adj3 psycho‐therap$)) OR ab((systemic$ adj3 famil$ OR famil$ adj3 (intervention$ OR therap$ OR treat$ OR program$))) OR ab((famil$ adj3 (psychotherap$ OR psychoeducation$ OR psycho‐education$ OR psycho‐therap$) OR (marriage OR marital OR couple$) adj3 therap$)) OR ab((famil$ adj1 (involv$ OR integrat$ OR participat$ OR focus$) OR psychodynamic OR psycho‐dynamic)) OR ab((group$ adj3 psychotherap$ OR group$ adj3 psycho therap$)) OR ab((systemic therap$ OR solution focus$)) OR ab(narrative adj1 therap))

AutismData

(autism.org.uk/autismdata)

Searched "family therapy" as keyword

Records were compared manually with EN library; 6 unique records added to Endnote

UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) Study Portfolio

(public.ukcrn.org.uk/search)

Searches:

Speciality : Mental health Subtopic: Autism spectrum disoders Research summary: family

Speciality : Mental health Subtopic: Autism spectrum disoders Research summary: systemic

Speciality : Mental health Subtopic: Autism spectrum disoders Research summary: psychotherapy

Speciality : Mental health Subtopic: Autism spectrum disoders Research summary: multisystemic

UK Clinical Trials Gateway (UKCTG)

(ukctg.nihr.ac.uk)

family therapy autis*

systemic autis*

multisystemic autis*

ClinicalTrials.gov

(clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home)

autism | (family OR systemic OR group) AND (therapy) OR autism | (family OR systemic OR group) AND (psychotherapy)

World Health Organisation International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP)

(apps.who.int/trialsearch/AdvSearch.aspx)

Basic search: Autism AND group OR autism AND family or autism AND parent OR autism AND systemic

Appendix 2. Record of searches

| Database | Search date | Date range/issue | Number of records |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library | 23 October 2015 | Issue 9 of 12, September 2015 | 75 |

| 18 January 2017 | Issue 11 of 12, November 2016 | 15 | |

| MEDLINE Ovid | 22 October 2015 | 1946 to October Week 3 2015 | 559 |

| 17 January 2017 | 1946 to December Week 1 2016 | 74 | |

| MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print | 17 January 2017 | 16 January 2017 | 15 |

| MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations | 17 January 2017 | 16 January 2017 | 39 |

| Embase OVID | 22 October 2015 | 1974 to 2015 Week 42 | 695 |

| 17 January 2017 | 1974 to 2017 Week 3 | 94 | |

| CINAHL Plus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) | 23 October 2015 | 1937 to current | 402 |

| 17 January 2017 | 1937 to current | 22 | |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) part of the Cochrane Library | 23 October 2015 | Issue 10 of 12, October 2015 | 15 |

| 18 January 2017 | Issue 1 of 12, January 2015 | 6 | |

| Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) part of the Cochrane Library | 23 October 2015 | Issue 2 of 4, April 2015 | 4 |

| ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center) | 23 October 2015 | 1966 to current | 564 |

| 17 January 2017 | 1966 to current | 32 | |

| PsycINFO OVID | 22 October 2015 | 1967 to October Week 3 2015 | 1417 |

| 17 January 2017 | 1967 to January Week 2 2017 | 118 | |

| Sociological Abstracts ProQuest | 23 October 2015 | 1952 to current | 52 |

| 18 January 2017 | 1952 to current | 4 | |

| Dissertation Abstracts International ProQuest | 4 November 2015 | 1743 to current | 176 |

| 16 January 2017 | 1743 to current | 215 | |

| AutismData (autism.org.uk/autismdata) | 23 October 2015 | All years | 6 |

| 18 January 2017 | All years | 4 | |

| UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio (UKCRN; public.ukcrn.org.uk/search); replaced by UK Clinical Trials Gateway | 23 October 2015 | All years | 1 |

| UK Clinical Trials Gateway (UKCTG; ukctg.nihr.ac.uk); replaces UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio | 18 January 2017 | All years | 1 |

| ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home) | 23 October 2015 | All years | 82 |

| 18 January 2017 | All years | 24 | |

| World Health Organisation International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch/AdvSearch.aspx) | 23 October 2015 | All years | 91 |

| 18 January 2017 | All years | 3 | |

| Total records | 4805 | ||

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abe 2014 | This is a non‐RCT study examining the effectiveness of a support group for family members of people with developmental disabilities. This support group is not family therapy. |

| Aerts 2011 | This is a non‐RCT study comprising a psychiatric family treatment for family members of individuals with autism. The intervention was competency based and is not family therapy. |

| Affleck 1982 | This is a review paper synthesising information about parent training approaches for individuals with developmental disabilities. |

| Allen 1980 | This is a two‐arm study comprising a transdisciplinary, early intervention programme for young children with, or known to be at risk of, developmental disabilities compared to a treatment‐as‐usual group. Neither intervention is family therapy. |

| Alonim 2004 | This is a discussion paper about an early‐intervention approach for young people with ASD. |

| Alquraini 2015 | This is a non‐RCT study comprising a relationship‐focused intervention to alleviate stress in mothers of people with ASD. The intervention is not family therapy per se. |

| Altiere 2009 | This is a cross‐sectional study investigating family dynamics and coping in parents of individuals with ASD. |

| Bennett 1983 | This is a two‐arm study comprising a family‐oriented treatment for parents of children with disabilities (primarily cerebral palsy) compared to a wait‐list control. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Bennett 1986 | This is a two‐arm study comprising a family‐oriented treatment for parents of children with disabilities (primarily cerebral palsy) compared to a wait‐list control. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Brockman 2016 | This is a discussion paper, which provides an overview of the use of family therapy techniques for people with ASD and family members. No RCT primary data is outlined. |

| Casenhiser 2011 | This is a two‐arm RCT comprising a social‐communication‐based intervention for young children with autism compared to a community treatment group (treatment as usual). Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Chen 2006 | This is a two‐arm study comprising individualised hospital care for individuals with autism compared to a family intervention. Participants were not randomised to either arm. |

| Chou 1992 | This is a two‐arm study comprising a task‐focused intervention, which incorporated systemic techniques, for individuals with developmental disabilities compared with a control group receiving treatment as usual. Participants were not randomised to either intervention. |

| Clancy 1972 | This is a description of a clinical programme of systemic and family‐focused techniques for individuals with autism. This is not a research trial and patients were not randomised to the programme. |

| Coleman 2015 | This is a discussion paper about psychoeducation for family members of individuals with ASD. |

| Coogle 2016 | This is a qualitative study focusing on the experiences of family members following engagement in an early intervention. |

| Davis 1991 | This is a two‐arm RCT comprising a home‐based, family‐focused counselling scheme for Bangladeshi families who had children with a range of developmental disabilities compared to treatment as usual. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Drahota 2008 | This is a two‐arm RCT comprising a 'building confidence' CBT intervention for young people with ASD compared with a wait‐list control. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Estreicher 1982 | This is a single‐arm study comprising family therapy techniques for families with individuals with developmental disabilities. Participants were not randomised to the intervention. |

| George 1988 | This is a single‐arm study comprising a therapeutic group based on systemic principles for grandparents and extended family members of individuals with developmental delays. The intervention is not family therapy albeit that it incorporates systemic techniques. |

| Goll‐Kopka 2009 | This is a description of 'The Frankfurt Multi‐family Therapy Model' for families who have children with developmental or global disabilities or disorders. This is a pilot study and patients were not randomised to the programme. |

| Heller 2015 | This is a discussion paper and literature review about interventions for adults as they age. No primary data are provided, nor is the review specifically about family therapy in ASD. |

| Helps 2016 | This is a discussion paper and narrative review about family therapy interventions for family members of individuals with ASD. |

| Johnson 2012 | This is a review of therapeutic work with couples who have a child with ASD. |

| Keen 2010 | This is a two‐arm quasi‐RCT comprising a parent‐focused intervention offered via home‐based sessions and a workshop for parents of children with ASD compared to a self‐directed video intervention. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Lordi 1964 | This is a discussion paper providing an overview of infantile autism, including family‐focused working. |

| NCT01919970 | This registration form pertains to a two‐arm RCT comprising an exposure‐based CBT treatment, incorporating parent input for young people with ASD, compared to treatment as usual. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Pickard 2017 | This is a review and discussion paper about family‐focused ways of working with individuals with ASD. |

| Pillay 2010 | This is a single‐arm study comprising a parent‐focused intervention for parents who have children with ASD. The intervention is not family therapy. |

| Roux 2013 | This is a two‐arm RCT comprising a group Stepping Stones Triple P intervention for parents of children with a range of intellectual disabilities compared to a wait‐list control. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Shank 1991 | This is a single‐arm study comprising a problem‐solving technique for parents of a child with a disability. The intervention is not family therapy albeit that it incorporates systemic techniques. |

| Siller 2013 | This is a two‐arm RCT comprising a focused playtime intervention for parents of children with ASD compared with psychoeducation. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Smock Jordan 2016 | This is a discussion paper about solution‐focused therapy techniques for family members of individuals with ASD. Case vignettes (non‐RCT data) are provided. |

| Solomon 2008 | This is a two‐arm RCT comprising a parent‐child interaction therapy for parents of children with ASD compared with a wait‐list control. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Wagner 2014 | This is a discussion paper, which also makes reference to a single‐arm intervention about a multi‐systemic therapy for families of individuals with ASD. Participants were not randomised to the intervention. |

| Wang 2008 | This is a two‐arm RCT comprising a parent training intervention for parents of children with autism compared with a wait‐list control. Neither arm is family therapy. |

| Whittingham 2009 | This is a two‐arm RCT comprising the Stepping Stones Triple P positive parenting programme for parents of children with ASD compared with a wait‐list control. Neither arm is family therapy. |

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Spain 2017 [pers comm].

| Methods | From a study by Wagner 2014, we noted the following sentence: "Building on the results from our pilot work, we obtained grant funding to conduct a small randomized clinical trial for youths with ASD and severe behavioral problems (expected N = 30)" (p 326). We contacted the senior author in 2016 and 2017 in order to clarify the status of the trial. |

| Participants | Not known |

| Interventions | Not known |

| Outcomes | Not known |

| Notes | We corresponded with the senior author in 2016 and 2017 but insufficient detail about the study was available. |

ASD: autism spectrum disorder.

Differences between protocol and review

We did not produce a 'Summary of findings' table(s), as planned, as no studies were included in this review.

Contributions of authors

Debbie Spain: review of proposal; design and preparation of the protocol; contributed to screening of abstracts and studies, initiating requests for further information from researchers who had undertaken potentially relevant studies, and preparation of the review. Jacqueline Sin: design and preparation of the protocol; contributed to screening of abstracts and studies, and preparation of the review. Eleni Paliokosta: design and preparation of the protocol; contributed to screening of abstracts and studies, and preparation of the review. Marie Furuta: design and preparation of the protocol; provided statistical advice and preparation of the review. Jonathan E Prunty: preparation of the protocol; and preparation of the review. Trudie Chalder: preparation of the protocol; and preparation of the review. Declan G Murphy: preparation of the protocol; and preparation of the review. Francesca G Happé: preparation of the protocol; and preparation of the review.

Debbie Spain holds overall responsibility for the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

King's College London, UK.

DS, JS, TC, DGM, FGH receive a salary from King's College London.

-

Kyoto University, Japan.

MF receives a salary from Kyoto University.

-

Tavistock and Portman National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, UK.

EP receives a salary from Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust.

-

South London and Maudsley (SLaM) NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

DS, TC, and DGM undertake clinical work at SLaM.

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

Financial support for DS and JS. The review presents independent research funded by the NIHR. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

-

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience at King's College London, UK.

Partial financial support for TC and DGM.

-

Dr Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation, Other.

Partial financial support for DGM.

-

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, based at Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London, UK.

JS was supported with funded research sessions.

Declarations of interest

Debbie Spain and her institute have received funds from a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship (CDRF‐2012‐03‐059, 2013 to 2018). Jacqueline Sin's institute received funds from a NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship (2012 to 2014), for a NIHR Post‐Doctoral Fellowship (2016 onward), and a clinical lectureship (NIHR BRC (Biomedical Research Centre)) based at Guy’s and St Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London (2015 to 2017). Eleni Paliokosta – none known. Marie Furuta – none known. Jonathan E Prunty – none known. Trudie Chalder is the named supervisor on the NIHR PhD Fellowship for Debbie Spain. She has received payment for workshops held for clinicians on chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and receives royalties for self‐help books on CFS. She has received payment for travel, accommodation and meeting expenses to attend conferences related to cognitive‐behavioural psychotherapy. Declan G Murphy – none known. Francesca G Happé (FGH) holds positions related to her autism research for which she is not paid but which involve travel to meetings for which she is reimbursed. She also received royalties on books and chapters, and occasional honoraria for writing or presenting, but these support her autism research in general and do not conflict with, or influence, her impartial involvement in the current review. FGH supervises Debbie Spain's PhD, and her institution receives a grant from the NIHR to do so. FGH is the president and board member of the International Society for Autism Research and cofounder of the Forum for Neuroscience and Special Education. FGH's institution has received fees for her membership of the Methusalem grant review panel. Her institution has received grants from the UK Medical Research Council for a population‐based twin study of autism spectrum disorders: genetic and environmental sources of cognitive and clinical heterogeneity; from the Baily Thomas Fund for work on the transition to young adulthood in autism spectrum disorder: mental health and well‐being in a population‐based sample of twins; the Wellcome Trust for work on glutamate and gamma‐Aminobutyric acid (GABA) in adults with autism: an in vivo study using magnetic resonance spectroscopy; and has grants pending from the Economic and Social Research Council for a topic not relevant to this review. FGH's institution has received honorarium from the British Academy for a lecture she carried out in 2014 and honorarium from the Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology for an invited annual review article. FGH receives royalties for the publications 'Autism and Talent' and 'Autism and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders Affecting Cognition'. She has received travel, accommodation and meeting expenses from the British Psychological Society, Simons Foundation, and the University of Leuven.

New

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Abe 2014 {published data only}

- Abe M, Kanna M. Evaluation of a support program for siblings and parents of children with disabilities. Japanese Journal of Special Education 2014;52(5):349‐58. [DOI: ] [Google Scholar]

Aerts 2011 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Aerts C. Psychiatric family treatment autism (PFA): hope and reality for families with ASD. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2011;20(Suppl 1):S25. [DOI: 10.1007/s00787-011-0181-5] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spain D. Family therapy for ASD: Cochrane review [personal communication]. Email to: L Kannerhuis 4 May 2016.

Affleck 1982 {published data only}

- Affleck G, McGrade BJ, McQueeney M, Allen D. Promise of relationship‐focused early intervention in developmental disabilities. Journal of Special Education 1982;16(4):413‐30. [DOI: 10.1177/002246698201600405] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Allen 1980 {published data only}

- Allen DA, others. Relationship‐focused intervention with high‐risk infants: first year findings. 88th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association; 1980 September 1‐5; Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 1980. [ERIC Number: ED207319]

Alonim 2004 {published data only}

- Alonim H. The Mifne Method — Israel. Early intervention in the treatment of autism/PDD: a therapeutic programme for the nuclear family and their child. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2004;16(1):39–43. [DOI: 10.2989/17280580409486562; PUBMED: 25860897] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alquraini 2015 {published data only}

- Alquraini T, Mahoney G. An exploratory investigation of the role of parenting stress in relationship focused intervention. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2015;28(6):536–47. [DOI: 10.1111/jar.12148] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Altiere 2009 {published data only}

- Altiere MJ, Kluge S. Family functioning and coping behaviours in parents of children with autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2009;18:83‐92. [DOI: 10.1007/s10826-008-9209-y] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Bennett 1983 {published data only}

- Bennett T, Algozzine B. Effects of family‐oriented intervention with young handicapped children on indicators of parental stress. files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED276171.pdf (accessed 3 May 2017).

Bennett 1986 {published data only}

- Bennett T, Algozzine B. Effects of family‐oriented intervention on home environment variables with young handicapped children. files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED280209.pdf (accessed 3 May 2017).

Brockman 2016 {published data only}

- Brockman M, Hussain K, Sanchez B, Turns B. Managing child behavior problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: utilizing structural and solution focused therapy with primary caregivers. American Journal of Family Therapy 2016;44(1):1‐10. [DOI: 10.1080/01926187.2015.1099414] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Casenhiser 2011 {published data only}

- Casenhiser DM, Shanker SG, Stieben J. Learning through interaction in children with autism: preliminary data from a social‐communication‐based intervention. Autism 2011;17(2):220‐41. [DOI: 10.1177/1362361311422052] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chen 2006 {published data only}

- Chen JM, Zhang JS. Short‐term hospitalization individualization therapy versus family therapy in treatment of childhood autism. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation 2006;10(28):108‐9. [Google Scholar]

Chou 1992 {published data only}

- Chou YC. Developing and testing an intervention program for assisting Chinese families in Taiwan who have a member with developmental disabilities. University of Minnesota, Dissertation Abstracts International 1992; Vol. 53, issue 9‐A.

Clancy 1972 {published data only}

- Clancy HG, McBride G. Therapy of childhood autism in the family. Current Psychiatric Therapies 1972;12:1‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coleman 2015 {published data only}

- Coleman CC. Use psychoeducational family therapy to help families cope with autism. Current Psychiatry 2015;14(4):e1. [Google Scholar]

Coogle 2016 {published data only}

- Coogle CG, Hanline MF. An exploratory study of family‐centred help‐giving practices in early intervention: families of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Child & Family Social Work 2016;21(2):249‐60. [DOI: 10.1111/cfs.12148] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Davis 1991 {published data only}

- Davis H, Rushton R. Counselling and supporting parents of children with developmental delay: a research evaluation. Journal of Mental Deficiency Research 1991;35(2):89‐112. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1991.tb01039.x] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Drahota 2008 {published data only}

- Drahota AM. Intervening with independent daily living skills for high‐functioning children with autism and concurrent anxiety disorders. University of California, Dissertation Abstracts International 2008; Vol. 69, issue 7‐A.

Estreicher 1982 {published data only}

- Estreicher DG. The development of family therapy techniques for families with developmentally disabled children. The Ohio State University, University Microfilms International 1982.

George 1988 {published data only}

- George JD. Therapeutic intervention for grandparents and extended family of children with developmental delays. Mental Retardation 1988;26(6):369‐75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goll‐Kopka 2009 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}