Key Points

Question

Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions are supported by extensive randomized clinical trial data, but what is the evidence that these models can be implemented and can have beneficial effects in general clinical settings?

Findings

In this randomized clinical implementation trial of 5596 veterans, a collaborative chronic care model was shown to be effectively implemented with practical, scalable facilitation support for clinicians. Effects on self-reported health outcomes were limited, but mental health hospitalization rate improved.

Meaning

These findings suggest that collaborative chronic care models can be exported to general clinical practice settings using implementation facilitation and, at least for individuals with complex mental health conditions, can improve health outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Collaborative chronic care models (CCMs) have extensive randomized clinical trial evidence for effectiveness in serious mental illnesses, but little evidence exists regarding their feasibility or effect in typical practice conditions.

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of implementation facilitation in establishing the CCM in mental health teams and the impact on health outcomes of team-treated individuals.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This quasi-experimental, randomized stepped-wedge implementation trial was conducted from February 2016 through February 2018, in partnership with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Nine facilities were enrolled from all VA facilities in the United States to receive CCM implementation support. All veterans (n = 5596) treated by designated outpatient general mental health teams were included for hospitalization analyses, and a randomly selected sample (n = 1050) was identified for health status interviews. Individuals with dementia were excluded. Clinicians (n = 62) at the facilities were surveyed, and site process summaries were rated for concordance with the CCM process. The CCM implementation start time was randomly assigned across 3 waves. Data analysis of this evaluable population was performed from June to September 2018.

Interventions

Internal-external facilitation, combining a study-funded external facilitator and a facility-funded internal facilitator working with a designated team for 1 year.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Facilitation was hypothesized to be associated with improvements in both implementation and intervention outcomes (hybrid type II trial). Implementation outcomes included the clinician Team Development Measure (TDM) and proportion of CCM-concordant team care processes. The study was powered for the primary health outcome, mental component score (MCS). Hospitalization rate was derived from administrative data.

Results

The veteran population (n = 5596) included 881 women (15.7%), and the mean (SD) age was 52.2 (14.5) years. The interviewed sample (n = 1050) was similar but was oversampled for women (n = 210 [20.0%]). Facilitation was associated with improvements in TDM subscales for role clarity (53.4%-68.6%; δ = 15.3; 95% CI, 4.4-26.2; P = .01) and team primacy (50.0%-68.6%; δ = 18.6; 95% CI, 8.3-28.9; P = .001). The percentage of CCM-concordant processes achieved varied, ranging from 44% to 89%. No improvement was seen in veteran self-ratings, including the primary outcome. In post hoc analyses, MCS improved in veterans with 3 or more treated mental health diagnoses compared with others (β = 5.03; 95% CI, 2.24-7.82; P < .001). Mental health hospitalizations demonstrated a robust decrease during facilitation (β = –0.12; 95% CI, –0.16 to –0.07; P < .001); this finding withstood 4 internal validity tests.

Conclusions and Relevance

Implementation facilitation that engages clinicians under typical practice conditions can enhance evidence-based team processes; its effect on self-reported overall population health status was negligible, although health status improved for individuals with complex conditions and hospitalization rate declined.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02543840

This randomized clinical trial reports the process and outcomes of establishing the collaborative chronic care model in 9 mental health facilities within the US Department of Veterans Affairs system.

Introduction

Collaborative chronic care models (CCMs) improve outcome in chronic medical conditions treated in primary care settings,1,2,3 depression treated in primary care facilities,4,5 and serious mental health conditions treated in mental health clinics.6,7 Collaborative chronic care models include several or all of 6 elements: work role redesign to support anticipatory, continuous care; self-management support; clinician decision support; clinical information systems; linkage to community resources; and leadership support.3,8,9 These elements are flexibly implemented according to local needs, capabilities, and priorities.7 However, little is known regarding how CCMs for mental health conditions perform when implemented in clinical practice with little to no exogenous research support.10

Data on implementing CCMs for mental health conditions come almost exclusively from depression treatment in primary care. Such CCMs can be successfully implemented,11,12,13,14 although their effect on clinical outcomes is inconsistent.15,16 The extent of implementation support provided in implementation trials has varied widely, in some cases including customized web-based tools, governance structures, and financial incentives.11,13,17 The sole CCM implementation controlled trial in mental health clinics used the Replicating Effective Programs framework18 compared with technical assistance to implement the Life Goals CCM19 for bipolar disorder and found better CCM implementation outcomes20 but no effect on clinical outcomes.21

Given the dearth of data on implementing CCMs in mental health clinics, we partnered with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention (OMHSP) to conduct a randomized implementation trial to establish CCM-based teams in 9 mental health clinics.22 We used a quasi-experimental,23 randomized stepped-wedge24 design to conduct a hybrid type II25 trial (ie, a trial focusing coequally on implementation and health outcomes). Such VA work has increasing relevance as health care systems and accountable care organizations move toward integrated care models.26,27 We hypothesized that implementation support, limited to an external facilitator working with facility staff, would enhance the adoption of CCM elements and improve veteran health outcomes.

Methods

Overview

This combined program evaluation and research project was reviewed by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (IRB). Implementation-related measures were exempt from IRB review, whereas veteran-level outcome measurement procedures were approved as research. Interviewed participants provided verbal informed consent, and a waiver was granted for patients studied through the administrative database only. The study rationale and design are detailed elsewhere.22 This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline28 and the EQUATOR guidelines for reporting implementation research29 and cluster randomized clinical trials. The trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1.

In 2013, OMHSP began an initiative to enhance care coordination in general mental health clinics by establishing interdisciplinary teams in each VA medical center throughout the United States. Although OMHSP disseminated centrally developed guidance, it gave facilities broad latitude to develop team processes locally. In 2015, OMHSP adopted the CCM6,7 as the team model and partnered with study investigators to develop CCM implementation support. The VA health care system comprises more than 140 distinct facilities, including more than 1000 clinical sites caring for more than 5 million veterans annually. The initiative took place in general mental health clinics, which care for a mixed-diagnosis population, including those with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders, typically supported by specialty substance and posttraumatic stress disorder clinics.

Site Selection

On the basis of veteran-level power calculations, 9 facilities were recruited from all VA facilities via publicity from OMHSP through the regional VA network leaders to individual mental health facility leaders. Qualifying facilities identified a general mental health clinic team, which committed to 1-hour weekly process redesign meetings for 12 months, and a staff member with process improvement experience to serve as an internal facilitator for 12 months at 10% effort (facility funded).

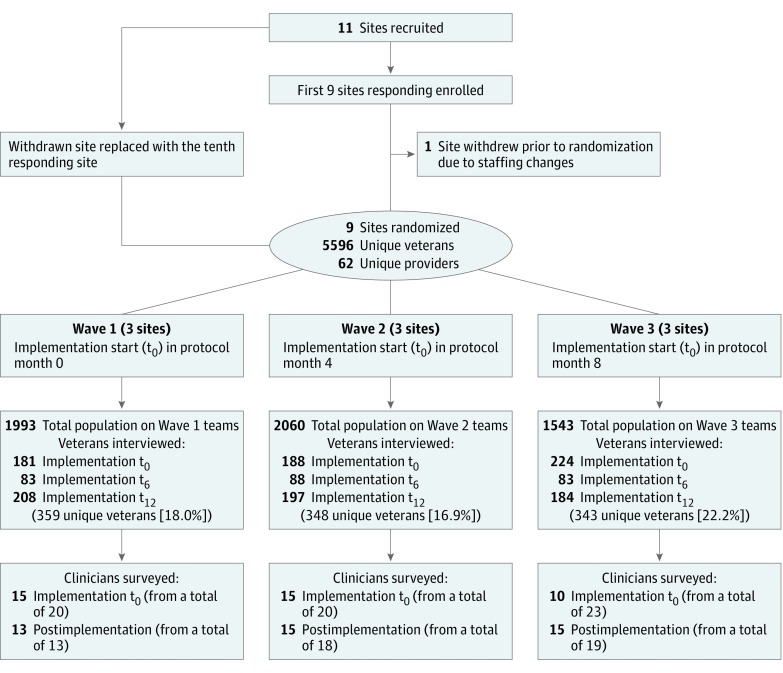

Twelve facilities qualified, and the first 9 to respond were enrolled. One site dropped out prior to randomization because of staffing changes and was replaced by the tenth facility (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram for Facilities, Veteran Participants, and Clinicians.

Providers are mental health clinicians on the teams that received implementation support. The parenthetical t0 represents baseline prior to implementation of support; t6, the 6-month midpoint of implementation support; t12, postimplementation support after 12 months.

Implementation Support

The implementation strategy was based on the model that health care is a complex adaptive system rather than a highly controlled machine.22,30,31 Specifically, implementation support was focused on creating conditions under which local solutions for local challenges could be developed in accordance with evidence-based guidance. This effort requires both team building, which has been shown to improve health care quality,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 and attention to specific health care processes. The CCM elements provided the clinical framework for process revision, considering the CCM as an integrated model, rather than a series of independent processes, based on the original insight by Wagner et al9 that improving single processes does not improve the outcome for chronic conditions. The blended internal-external facilitation model was chosen on the basis of evidence from previous VA work.41

Facilitation is a multifaceted strategy of interactive problem solving and support, which for this project included an external facilitator (study funded) who provided guidance and quality improvement expertise to teams while the internal facilitator (facility funded) helped on site to direct the implementation process.42,43,44 Facilitation was organized according to the 4 Replicating Effective Programs45 implementation stages: preconditions assessment, preimplementation preparation, implementation, and maintenance. Specific facilitation tasks included in-depth pre–site visit assessment and orientation of the site to the facilitation process and the CCM; 1½-day face-to-face site visit to launch the process redesign phase; 6 months of weekly videoconferences and/or conference calls with the team, weekly meetings with the internal facilitator, and ad hoc telephone and email communications; and 6 months of step-down facilitation contacts as needed.

Three of us (M.S.B., C.M., B.K.) each served as external facilitators for 3 sites, spending a mean (SD) 136.2 (27.6) hours per site in facilitation tasks for up to 12 months. Implementation activities were guided by a structured workbook that leads teams through self-assessment and process redesign according to the 6 CCM elements.

Stepped-Wedge Design

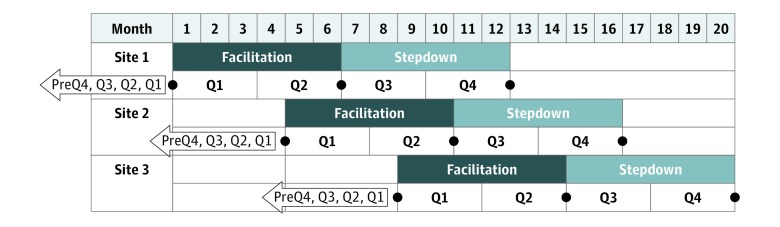

Given OMHSP’s desire for all participating facilities to receive implementation support, we used a stepped-wedge design.24,46,47,48 Specifically, facilities were randomized into 3 different start times of 3 sites each, with implementation support beginning at approximately 4-month intervals for each wave (start dates: February 2016 through February 2017; last site completed February 2018; Figure 2). To minimize imbalance in site characteristics across waves, we used a previously described algorithm22 to determine the least imbalanced randomization allocation schemas and then randomly selected 1 allocation scheme from among these. The control condition consisted of waiting for implementation support, during which time the facilities had continued access to OMHSP materials, received the CCM workbook, and participated in monthly technical support conference calls.

Figure 2. Protocol Structure: Implementation and Evaluation.

The implementation and evaluation protocol is illustrated for 3 facilities across 3 waves. Implementation consisted of 6 months of intensive facilitation followed by 6 months of step-down support (shaded rows). Facilities were assigned staggered start times for implementation, beginning at approximately 4-month intervals. The evaluative activities are illustrated beneath the implementation activities for each site (unshaded rows). Specifically, population-level hospitalization data were gathered on a quarterly basis from 12 months prior to the start of implementation (PreQ4-PreQ1) and for the 12 months of implementation (Q1-Q4). The veteran interview sample was assessed at the beginning of implementation, after 6 months, and after 12 months of implementation (black dots). Clinician assessment with the Team Development Measure took place at the beginning of facilitation and during step-down support. Thus, all evaluation activities were anchored to the start time of implementation support, considered protocol time zero (t0) for each site. Q indicates quarter of the year.

Participant Population and Sample

The veteran population of interest consisted of individuals who were actively treated by a participating team, defined as at least 2 visits to a team clinic over the year prior to facilitation, including 1 visit in the previous 3 months. Only veterans with a diagnosis of dementia were excluded. This population served as the basis for hospitalization data analyses. From this population, 500 veterans from each facility were randomly selected. From these veterans, 85 were recruited for telephone interviews assessing health status and satisfaction at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months of implementation support. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the veterans included are summarized in Table 1, including race/ethnicity since they have been associated with mental health outcomes; race/ethnicity was characterized through administrative or interview data, both based on self-report. The clinician population included all members of the participating teams.

Table 1. Baseline Veteran Participant Characteristics.

| Variable | No. (%) | Population vs Sample Differences, χ2 or F Test | P Value | Effect Sizea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population in Treatment With CCM Team (n = 5596) | Interviewed Sample (n = 1050) | ||||

| Demographic data | |||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 52.2 (14.5) | 53.5 (14.0) | 9.13 | .003 | 0.0016 |

| Female sex | 881 (15.7) | 210 (20.0) | 15.9 | .001 | 0.0522b |

| Race/ethnicity | 3.6 | .16 | 0.0256 | ||

| White | 4192 (79.5) | 825 (81.7) | |||

| Black | 933 (17.7) | 159 (15.7) | |||

| Other | 149 (2.8) | 26 (2.6) | |||

| Hispanic | 676 (12.4) | 97 (9.5) | 9.1 | .003 | 0.0400 |

| Minority | 1725 (31.3) | 275 (26.5) | 12.6 | .001 | 0.0468 |

| Married | 2602 (46.8) | 487 (46.7) | 0.03 | .86 | 0.0023 |

| Employed (full- or part-time; self-employed) | 2702 (50.2) | 532 (52.5) | 2.0 | .16 | 0.0190 |

| Rural residence | 1205 (21.6) | 227 (21.6) | 0.03 | .87 | 0.0022 |

| Period of service, Gulf War or later (1990-present) | 2858 (51.1) | 497 (47.3) | 6.7 | .01 | 0.0339 |

| VA disability ≥50% | 4338 (77.5) | 844 (80.4) | 5.6 | .02 | 0.0309 |

| Clinical data | |||||

| Depression or anxiety disorder | 3278 (58.6) | 592 (56.4) | 1.1 | .30 | 0.0136 |

| Serious mental illness (bipolar spectrum or schizophrenia) | 1924 (34.4) | 340 (32.4) | 1.2 | .27 | 0.0146 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 2793 (49.9) | 474 (45.1) | 8.5 | .01 | 0.0382 |

| Substance use disorder | 1096 (19.6) | 169 (16.1) | 8.1 | .01 | 0.0373 |

| No. of active mental health diagnoses, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.4) | 4.8 | .03 | 0.0008 |

| No. of active medical diagnoses, mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.3) | 8.9 | .03 | 0.0015 |

| Mental health hospitalization in previous year | 248 (4.4) | 36 (3.4) | 2.5 | .11 | 0.0207 |

| Medical-surgical hospitalization in previous year | 405 (7.2) | 73 (7.0) | 0.1 | .73 | 0.0046 |

Abbreviations: CCM, collaborative chronic care model; VA, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Effect sizes for continuous variables are reported as η2, and categorical variables as Cramer V.

Purposive oversampling for representation of women.

Implementation Outcome Measures

The implementation outcomes focused on team function plus concordance of team processes with the 6 CCM elements.22,30,31 Team function was assessed by clinician survey at baseline and during the second 6 months of implementation using the Team Development Measure,49 which consists of 4 subscales for rating items on a strongly agree to strongly disagree continuum: communication, cohesion, role clarity, and team primacy (prioritizing team over individual goals). Subscale scores were calculated as the mean percentage of subscale items endorsed as agree or strongly agree across clinicians.

Concordance of team processes with the CCM process was derived from the CCM workbook, which deconstructs the 6 CCM elements into 27 specific processes. Workbook process summaries were collected from each team at the end of the implementation support period (preimplementation process documentation was not required). We reviewed each process for each team and came to consensus ratings for each process of 0 (not consistent with the CCM or not completed), 0.5 (partially consistent), or 1.0 (fully consistent). Ratings for the 27 processes were compiled, and a percentage of CCM concordance across the 27 possible processes was calculated for each team.

Intervention Outcome Measures

Self-rated veteran health status and satisfaction data were gathered by telephone interview of consented participants at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months of implementation support. The interviews included the mental component score (MCS) and physical component score of the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey,50 a measure adapted from the Short Form-1251 for health status (US general population mean [SD] score, 50 [10], with a higher score indicating better), and the short-form Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire52 for recovery-oriented quality of life (score range: 0-100, with a higher score indicating better). Care satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction Index53 (score range: 12-72, with a higher score indicating better), and perception of collaborativeness of care was measured using the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care54 (score range: 1-33, with a higher score indicating better). The primary intervention outcome variable, for which the study was powered, was the MCS.

Using the entire team-treated population, we gathered mental health hospitalization data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, as was done previously.55 Data were gathered on a quarterly basis from 1 year prior to implementation support (protocol t-12 to t0 [time zero]) through 1 year of implementation support (protocol t0 to t12), with a binary-coded variable for each veteran for each quarter (hospitalized or not).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the overall population and interview sample were compared using unpaired, 2-tailed t test or χ2. For veteran self-report measures, the initial plan sought to randomly sample 85 veterans per team (90% power; α = .05; effect size, 0.20 for the MCS) for interview t0, t6, and t12, with as many veterans providing repeated measures as possible. When previously interviewed veterans were unavailable, additional randomly selected team-treated veterans who met the study criteria were interviewed in their stead, yielding a repeated cross-sectional design.23 Given the interviewer workflow, we reduced the t6 interview target sample size to 25; this reduction did not affect power for primary t0-to-t12 analyses.

For veteran interview data, a mixed-effects model was used, assuming that the scores were continuous with an underlying multivariate normal model. Linear contrasts of changes t0 to t12 composed primary analyses. To conduct subgroup analyses, we used interaction terms in the full model rather than stratification.56 The model used site as a random effect and the demographic and included clinical covariates listed in Table 1. The data on outcomes and major covariates were reviewed to detect excessive missing values, outliers, and severe skewness. Implementation start-time wave was collinear with time and hence excluded from the models.

Analyses were done with the SAS statistical package, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Unadjusted and adjusted models yielded similar results, and both results are presented for key findings. All significance testing was 2-sided, with a statistical significance level that was Bonferroni corrected to P ≤ .01. Data analysis of this evaluable population was performed from June to September 2018.

Results

Study Flow and Participant Characteristics

The veteran population (n = 5596) included 881 women (15.7%), and the mean (SD) age was 52.2 (14.5) years. The interviewed sample (n = 1050) was similar but was oversampled for women (n = 210 [20.0%]). Sixty-two clinicians (35 women [56.5%]; mean [SD] age, 49.6 [9.9] years) participated.

Facility, veteran, and clinician participation are summarized in Figure 1. Comparison of veterans who consented to an interview and the population from which they were drawn are summarized in Table 1. Because of the large sample size, small but statistically significant differences were seen in several variables; however, effect sizes for the magnitude of these differences were negligible. Self-report data were missing for 9.8% of items across all measures. Intraclass correlation 1 values for the 5 clinical interview measures ranged from 0.0007 to 0.0296.

Implementation Outcomes

Team Development Measure subscales (Table 2) showed high ratings for cohesion and communication at baseline, which did not change with implementation support. However, role clarity (53.4%-68.6%; δ = 15.3; 95% CI, 4.4-26.2; P = .01) and team primacy (50.0%-68.6%; δ = 18.6; 95% CI, 8.3-28.9; P = .001) improved statistically significantly. Teams varied on the proportion of the CCM-concordant processes achieved by the end of implementation support, ranging from 44% to 89% (eTable in Supplement 2). Postimplementation CCM process concordance and Team Development Measure scores, although measuring distinct implementation outcomes, were highly correlated (r = 0.90; P = .001).

Table 2. Summary of Implementation and Clinical Intervention Outcomes.

| Measure | Preimplementation, % | Postimplementation, % | Change, % (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation outcomes: Team Development Measurea | ||||

| Cohesion | 84.0 | 84.5 | 0.5 (−7.4 to 8.4) | .75 |

| Communication | 83.3 | 84.4 | 1.1 (−5.6 to 7.7) | .90 |

| Role clarity | 53.4 | 68.6 | 15.3 (4.4 to 26.2) | .01 |

| Team primacy | 50.0 | 68.6 | 18.6 (8.3 to 28.9) | .001 |

| Clinical intervention outcomesb | ||||

| VR-12 | ||||

| MCS | 30.7 | 30.9 | 0.2 (−1.3 to 1.5) | .97 |

| PCS | 42.5 | 43.7 | 1.2 (0.04 to 2.3) | .04c |

| QLESQ | 49.8 | 50.3 | 0.5 (−1.3 to 2.3) | .58 |

| Satisfaction index | 53.0 | 52.4 | −0.6 (−2.0 to 0.9) | .44 |

| Patient assessment of chronic illness care | 22.0 | 22.0 | 0.0 (−0.6 to 0.8) | .84 |

Abbreviations: MCS, mental component score; PCS, physical component score; QLESQ, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; VR-12, Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey.

Subscale scores are the mean percentage of subscale items endorsed as agree or strongly agree across clinicians.

See Methods section in text for details.

Not significant after Bonferroni correction.

Intervention Outcomes

Clinical Interview Measures

The MCS, the primary intervention outcome, did not change statistically significantly with implementation support in adjusted or unadjusted models, nor did other interview measures (Table 2). In post hoc analyses, those with complex clinical presentations, defined as receiving treatment for 3 or more mental health diagnoses in the previous year, demonstrated statistically significant improvements in MCS during the facilitation year (21.2-24.3; δ = 3.1; 95% CI, 1.0-5.3; P = .004), whereas those with 2 or fewer diagnoses declined nonsignificantly during that time (33.9-32.0; δ = –1.9; 95% CI, –3.7 to –0.1; P = .04). A linear contrast comparing the difference in MCS from t0 to t12 between those with a complex clinical presentation and those without was statistically significant (β = 5.03 [95% CI, 2.24-7.82; P < .001]; unadjusted β = 4.60 [95% CI, 1.90-7.29; P < .001]).

Mental Health Hospitalization Rate

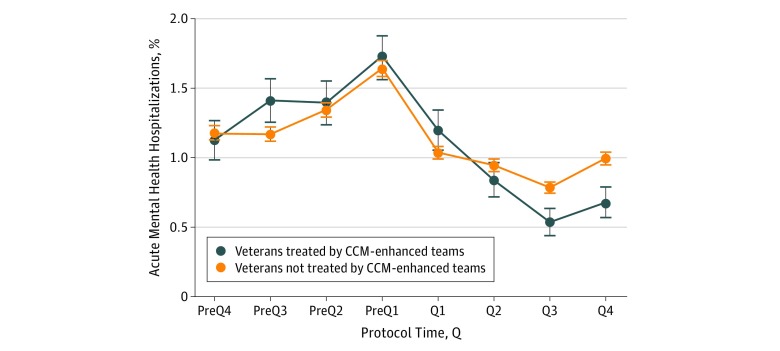

Implementation support was associated with statistically significant and sustained reduction in mental health hospitalization rate (β = –0.12 [95% CI, –0.16 to –0.07; P < .001]; unadjusted β = –0.11 [95% CI, –0.14 to –0.07; P < .001]; Figure 3). In post hoc analyses, we saw no difference in the way veterans were treated between higher- and lower-implementing teams (eTable in Supplement 2) in either hospitalization rate or MCS.

Figure 3. Mental Health Hospitalization Rates.

The x-axis displays protocol time, with implementation support occurring from Q1 through Q4. The blue line represents hospitalization rate for veterans treated by collaborative chronic care model (CCM)–enhanced teams, and the orange line represents veterans from the same clinics who were not treated by the CCM-enhanced teams (see text for details). Error bars represent SEs. Q indicates quarter of the year.

Given that this quasi-experimental trial did not include a separate control group, we addressed 4 threats to the internal validity of this finding. First, seasonal effects were deemed unlikely as waves began implementation support (protocol t0 in Figure 1) across the year.

Second, we considered that veterans who were hospitalized in the prefacilitation year might be less likely to stay enrolled in VA care during facilitation, thus decreasing population hospitalization risk at follow-up. More than 95% of veterans who receive mental health services do not receive mental health services outside of the VA system.57 We nonetheless reran the analyses, excluding those veterans who did not receive VA outpatient mental health care during implementation support. Only 435 veterans (7.8% [435 of 5596]) were excluded, and the findings remained statistically significant (β = –0.11; 95% CI, –0.15 to –0.06; P < .001).

Third, we investigated the unmeasured facility effects, independent of implementation support, by running identical analyses on veterans who met the study criteria but were treated in any mental health clinic, exclusive of the designated team’s clinics (n = 46 755). A linear spline model with a knot at t0 was used, and an interaction term was added to indicate whether the team-treated population change from before to after baseline (t0) differed from the analogous change for the non–team-treated population. As did the team-treated veterans, the non–team-treated veterans also demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in hospitalization rate during the facilitation period (β = –0.05; 95% CI, –0.07 to –0.04; P < .001; Figure 3). When the model included the interaction effect of team-treated and non–team-treated status in the spline model, the difference between team-treated and non–team-treated decrease in hospitalization rates was statistically significant (β = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.06 to –0.29; P < .001), with a larger decrease in hospitalization rate among team-treated veterans. During the facilitation year, the team-treated rate declined from 1.04% per quarter to 0.53% per quarter with a mean rate of 0.81% per quarter compared with a mean rate of 0.94% per quarter for the non–team-treated rate, a difference of 13.8% per quarter.

Fourth, we wondered whether the decrease in hospitalization rate concurrent with the start of facilitation at t0 (PreQ1 to Q1 in Figure 3) could be associated with simply having had an outpatient visit in PreQ1 (which was part of the team-treated population definition). Therefore, we investigated whether a decrease in hospitalization rate in a given quarter was more generally associated with a visit in the previous quarter. Specifically, we determined whether veterans with a visit in PreQ2 (n = 2089) demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in hospitalization rate from PreQ2 to PreQ1. They did not (1.15% to 1.05%; δ = 0.96%; 95% CI, –0.44 to 0.63; P = .72).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this trial is one of the first studies to evaluate CCM implementation for individuals treated in mental health clinics and the first CCM trial to assess implementation effect in a multidiagnosis mental health population. The stepped-wedge design preserved scientific rigor while serving the policy needs of the health care system. The trial used minimal study-funded support (<3 hours per week per site of external facilitation effort), enhancing external validity and potential for scale-up and spread. Although the effect on overall population health status was negligible, facilitation improved team function and reduced population-level hospitalizations. These results align in general with those in previous CCM implementation trials showing improvements in implementation outcomes11,12,13,14,19 with mixed effects on clinical outcomes.15,16,20

Although MCS, the primary outcome, did not improve in the overall sample, those with more complex clinical symptoms did improve by a magnitude of 0.31 SD, comparable to meta-analyses on CCM clinical trial samples.6 The finding of a preferential effect in more complex individuals is consistent with evidence from an earlier VA multisite effectiveness trial58 and a recent meta-analysis of implementing patient-centered medical homes, which are based on CCM principles,59 which both demonstrated more benefit among higher-morbidity individuals.60 Also consistent with these findings are those from the previously noted earlier effectiveness trial that demonstrated reduced weeks in full-episode but not mean symptom levels.61,62 The primary population-based approach taken in the current study included less severely ill veterans, which may have mitigated the measured effect of care reorganization. The population-level effect on hospitalization rates may be the result of the substantial focus of implementation facilitation on changing workflow to support coordinated, continuous care. Overall, the results indicate that clinical benefits may be limited to those with complex clinical presentations or at risk for hospitalization.

We did not see differences in MCS or hospitalization rate between higher- and lower-implementing facilities, possibly because a critical threshold in CCM implementation had been met by all facilities; because chosen measures did not play a role in health outcome effects; or because specific individual CCM elements were responsible for improved outcome, which was not reflected in the overall CCM concordance measure. Exploring such mechanisms is the focus of ongoing mixed-methods analyses.

Taken together, the results suggest that implementation efforts at the clinician level enhance evidence-based care organization, which may result in improvements in outcome for more complex individuals and those at risk for hospitalization but no change in health status for the overall clinic population. However, more intense clinician-level support or simply more time may be needed to see population-level health status effects.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is the lack of an independent control group owing to health care system policy priorities and trial practicalities.22 However, the study design incorporated strengths recommended for quasi-experimental designs, including partial randomization, balancing of sites, embedding data collection at critical protocol points, and use of baseline measures.23 In addition, the hospitalization rate analyses employed multiple baseline and follow-up time points, and the finding that hospitalization rate decreased with facilitation withstood 4 tests of internal validity. Furthermore, for pragmatic reasons, the protocol did not include interview assessments at all facilities at all stepped-wedge time points; however, sufficient data were gathered to conduct the primary analysis.

The trial engaged only volunteer facilities within the VA. However, facilities enrolled did not differ substantially from the national VA facility pool in any characteristics identified a priori to balance the start-time waves.22 Furthermore, external validity limitations of VA-based studies are diminishing as health care organizations move toward integrated care models.3,26,27,45 Other limitations include small but statistically significant differences between the interviewed sample and the clinic population, follow-up limited to 1 year, and measures that may not reflect the effects of care reorganization.

Conclusions

Working solely at the clinician level with minimal study-funded support, we found that implementing the CCM can reduce hospitalization rates and, for complex individuals, improve health status. The next challenge is to target, scale up, and spread implementation for teams that treat populations who are most likely to benefit from CCM care.

Trial Protocol

eTable. By-Facility Summary of Implementation Outcomes

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):-. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909-1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(1):75-85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badamgarav E, Weingarten SR, Henning JM, et al. . Effectiveness of disease management programs in depression: a systematic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2080-2090. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314-2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller CJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron BE, Kilbourne AM, Woltmann E, Bauer MS. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions: cumulative meta-analysis and metaregression to guide future research and implementation. Med Care. 2013;51(10):922-930. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a3e4c4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, Georges H, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):790-804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(12):1097-1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511-544. doi: 10.2307/3350391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solberg LI, Crain AL, Jaeckels N, et al. . The DIAMOND initiative: implementing collaborative care for depression in 75 primary care clinics. Implement Sci. 2013;8:135. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossom RC, Solberg LI, Parker ED, et al. . A statewide effort to implement collaborative care for depression: reach and impact for all patients with depression. Med Care. 2016;54(11):992-997. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sederer LI, Derman M, Carruthers J, Wall M. The New York State Collaborative Care Initiative: 2012-2014. Psychiatr Q. 2016;87(1):1-23. doi: 10.1007/s11126-015-9375-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bao Y, McGuire TG, Chan YF, et al. . Value-based payment in implementing evidence-based care: the Mental Health Integration Program in Washington state. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(1):48-53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer AM, Azzone V, Goldman HH, et al. . Implementation of collaborative depression management at community-based primary care clinics: an evaluation. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(9):1047-1053. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.9.pss6209_1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossom RC, Solberg LI, Magnan S, et al. . Impact of a national collaborative care initiative for patients with depression and diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;44:77-85. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sowa NA, Jeng P, Bauer AM, et al. . Psychiatric case review and treatment intensification in collaborative care management for depression in primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(5):549-554. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumann MS, Sogolow ED. Replicating Effective Programs: HIV/AIDS prevention technology transfer. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(5)(suppl):35-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer MS, Kilbourne AM Life Goals Collaborative Care. http://www.lifegoalscc.com. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 20.Waxmonsky J, Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, et al. . Enhanced fidelity to treatment for bipolar disorder: results from a randomized controlled implementation trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(1):81-90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, Nord KM, et al. . Long-term clinical outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of two implementation strategies to promote collaborative care attendance in community practices. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):642-653. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0598-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer MS, Miller C, Kim B, et al. . Partnering with health system operations leadership to develop a controlled implementation trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11:22. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0385-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handley MA, Lyles CR, McCulloch C, Cattamanchi A. Selecting and improving quasi-experimental designs in effectiveness and implementation research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:5-25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davey C, Hargreaves J, Thompson JA, et al. . Analysis and reporting of stepped wedge randomised controlled trials: synthesis and critical appraisal of published studies, 2010 to 2014. Trials. 2015;16:358. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0838-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217-226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shortell SM, Wu FM, Lewis VA, Colla CH, Fisher ES. A taxonomy of accountable care organizations for policy and practice. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(6):1883-1899. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luft HS. Becoming accountable—opportunities and obstacles for ACOs. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(15):1389-1391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1009380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG; CONSORT Group . Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. ; StaRI Group . Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plesk P. Redesigning health care with insights from the science of complex adaptive systems In: Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001:309-322. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan ME, Lanham HJ, Crabtree BF, et al. . The role of conversation in health care interventions: enabling sensemaking and learning. Implement Sci. 2009;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shortell SM, Rousseau DM, Gillies RR, Devers KJ, Simons TL. Organizational assessment in intensive care units (ICUs): construct development, reliability, and validity of the ICU nurse-physician questionnaire. Med Care. 1991;29(8):709-726. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199108000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dean PJ, LaVallee R, McLaughlin CP Teams at the core of continuous learning. In: McLaughlin CP, ed. Continuous Quality Improvement in Health Care: Theory Implementation and Applications. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1999:147-169. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):569-572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Risser DT, Rice MM, Salisbury ML, Simon R, Jay GD, Berns SD; The MedTeams Research Consortium . The potential for improved teamwork to reduce medical errors in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34(3):373-383. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitt MH. Collaboration improves the quality of care: methodological challenges and evidence from US health care research. J Interprof Care. 2001;15(1):47-66. doi: 10.1080/13561820020022873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bower P, Campbell S, Bojke C, Sibbald B. Team structure, team climate and the quality of care in primary care: an observational study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(4):273-279. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.4.273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA. 2004;291(10):1246-1251. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemieux-Charles L, McGuire WL. What do we know about health care team effectiveness? a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(3):263-300. doi: 10.1177/1077558706287003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davenport DL, Henderson WG, Mosca CL, Khuri SF, Mentzer RM Jr. Risk-adjusted morbidity in teaching hospitals correlates with reported levels of communication and collaboration on surgical teams but not with scale measures of teamwork climate, safety climate, or working conditions. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(6):778-784. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, Parker LE, Curran GM, Fortney JC. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(suppl 4):904-912. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3027-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. . Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10:109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harvey G, Loftus-Hills A, Rycroft-Malone J, et al. . Getting evidence into practice: the role and function of facilitation. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37(6):577-588. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02126.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stetler CB, Legro MW, Rycroft-Malone J, et al. . Role of “external facilitation” in implementation of research findings: a qualitative evaluation of facilitation experiences in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the Replicating Effective Programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beard E, Lewis JJ, Copas A, et al. . Stepped wedge randomised controlled trials: systematic review of studies published between 2010 and 2014. Trials. 2015;16:353. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0839-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hargreaves JR, Prost A, Fielding KL, Copas AJ. How important is randomisation in a stepped wedge trial? Trials. 2015;16:359. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0872-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prost A, Binik A, Abubakar I, et al. . Logistic, ethical, and political dimensions of stepped wedge trials: critical review and case studies. Trials. 2015;16:351. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0837-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stock R, Mahoney E, Carney PA. Measuring team development in clinical care settings. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):691-700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selim AJ, Rogers W, Fleishman JA, et al. . Updated U.S. population standard for the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):43-52. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9418-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220-233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stevanovic D. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-short form for quality of life assessments in clinical practice: a psychometric study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(8):744-750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01735.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nabati L, Shea N, McBride L, Gavin C, Bauer MS. Adaptation of a simple patient satisfaction instrument to mental health: psychometric properties. Psychiatry Res. 1998;77(1):51-56. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(97)00122-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gugiu PC, Coryn C, Clark R, Kuehn A. Development and evaluation of the short version of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care instrument. Chronic Illn. 2009;5(4):268-276. doi: 10.1177/1742395309348072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bauer MS, Miller CJ, Li M, Bajor LA, Lee A. A population-based study of the comparative effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics vs older antimanic agents in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(6):481-489. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine–reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2189-2194. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr077003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu CF, Chapko M, Bryson CL, et al. . Use of outpatient care in Veterans Health Administration and Medicare among veterans receiving primary care in community-based and hospital outpatient clinics. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(5, pt 1):1268-1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01123.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kilbourne AM, Biswas K, Pirraglia PA, Sajatovic M, Williford WO, Bauer MS. Is the collaborative chronic care model effective for patients with bipolar disorder and co-occurring conditions? J Affect Disord. 2009;112(1-3):256-261. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sidorov JE. The patient-centered medical home for chronic illness: is it ready for prime time? Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(5):1231-1234. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sinaiko AD, Landrum MB, Meyers DJ, et al. . Synthesis of research on patient-centered medical homes brings systematic differences into relief. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(3):500-508. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. ; Cooperative Studies Program 430 Study Team . Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part I: intervention and implementation in a randomized effectiveness trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):927-936. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. ; Cooperative Studies Program 430 Study Team . Collaborative care for bipolar disorder, part II: impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):937-945. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable. By-Facility Summary of Implementation Outcomes

Data Sharing Statement