Abstract

Background

Adequate haemodialysis (HD) in people with end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) is reliant upon establishment of vascular access, which may consist of arteriovenous fistula, arteriovenous graft, or central venous catheters (CVC). Although discouraged due to high rates of infectious and thrombotic complications as well as technical issues that limit their life span, CVC have the significant advantage of being immediately usable and are the only means of vascular access in a significant number of patients. Previous studies have established the role of thrombolytic agents (TLA) in the prevention of catheter malfunction. Systematic review of different thrombolytic agents has also identified their utility in restoration of catheter patency following catheter malfunction. To date the use and efficacy of fibrin sheath stripping and catheter exchange have not been evaluated against thrombolytic agents.

Objectives

This review aimed to evaluate the benefits and harms of TLA, preparations, doses and administration as well as fibrin‐sheath stripping, over‐the‐wire catheter exchange or any other intervention proposed for management of tunnelled CVC malfunction in patients with ESKD on HD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register up to 17 August 2017 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Specialised Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We included all studies conducted in people with ESKD who rely on tunnelled CVC for either initiation or maintenance of HD access and who require restoration of catheter patency following late‐onset catheter malfunction and evaluated the role of TLA, fibrin sheath stripping or over‐the‐wire catheter exchange to restore catheter function. The primary outcome was be restoration of line patency defined as ≥ 300 mL/min or adequate to complete a HD session or as defined by the study authors. Secondary outcomes included dialysis adequacy and adverse outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed retrieved studies to determine which studies satisfy the inclusion criteria and carried out data extraction. Included studies were assessed for risk of bias. Summary estimates of effect were obtained using a random‐effects model, and results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes, and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous outcomes. Confidence in the evidence was assessed using GRADE.

Main results

Our search strategy identified 8 studies (580 participants) as eligible for inclusion in this review. Interventions included: thrombolytic therapy versus placebo (1 study); low versus high dose thrombolytic therapy (1); alteplase versus urokinase (1); short versus long thrombolytic dwell (1); thrombolytic therapy versus percutaneous fibrin sheath stripping (1); fibrin sheath stripping versus over‐the‐wire catheter exchange (1); and over‐the‐wire catheter exchange versus exchange with and without angioplasty sheath disruption (1). No two studies compared the same interventions. Most studies had a high risk of bias due to poor study design, broad inclusion criteria, low patient numbers and industry involvement.

Based on low certainty evidence, thrombolytic therapy may restore catheter function when compared to placebo (149 participants: RR 4.05, 95% CI 1.42 to 11.56) but there is no data available to suggest an optimal dose or administration method. The certainty of this evidence is reduced due to the fact that it is based on only a single study with wide confidence limits, high risk of bias and imprecision in the estimates of adverse events (149 participants: RR 2.03, 95% CI 0.38 to 10.73).

Based on the available evidence, physical disruption of a fibrin sheath using interventional radiology techniques appears to be equally efficacious as the use of a pharmaceutical thrombolytic agent for the immediate management of dysfunctional catheters (57 participants: RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.07).

Catheter patency is poor following use of thrombolytic agents with studies reporting median catheter survival rates of 14 to 42 days and was reported to improve significantly by fibrin sheath stripping or catheter exchange (37 participants: MD ‐27.70 days, 95% CI ‐51.00 to ‐4.40). Catheter exchange was reported to be superior to sheath disruption with respect to catheter survival (30 participants: MD 213.00 days, 95% CI 205.70 to 220.30).

There is insufficient evidence to suggest any specific intervention is superior in terms of ensuring either dialysis adequacy or reduced risk of adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

Thrombolysis, fibrin sheath disruption and over‐the‐wire catheter exchange are effective and appropriate therapies for immediately restoring catheter patency in dysfunctional cuffed and tunnelled HD catheters. On current data there is no evidence to support physical intervention over the use of pharmaceutical agents in the acute setting. Pharmacological interventions appear to have a bridging role and long‐term catheter survival may be improved by fibrin sheath disruption and is probably superior following catheter exchange. There is no evidence favouring any of these approaches with respect to dialysis adequacy or risk of adverse events.

The current review is limited by the small number of available studies with limited numbers of patients enrolled. Most of the studies included in this review were judged to have a high risk of bias and were potentially influenced by pharmaceutical industry involvement.

Further research is required to adequately address the question of the most efficacious and clinically appropriate technique for HD catheter dysfunction.

Plain language summary

Interventions for treating central venous catheter malfunction

What is the issue?

Patients who rely on haemodialysis due to kidney failure require vascular access and although not optimal, a tunnelled haemodialysis catheter is frequently used. Unfortunately, along with infection issues these lines are prone to dysfunction due to clotting and fibrin sheath formation. Medications such as alteplase have a recognised role in preventing line dysfunction but the best approach to treating established line dysfunction has not been found.

What did we do?

We searched Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's Specialised Register up to 17 August 2017 and performed a systematic review of studies performed in patients with dysfunctional haemodialysis catheters and compared the success of thrombolytic agents, fibrin sheath stripping and line replacement.

What did we find?

We found eight studies involving 580 participants that tested the three different treatments. Studies also compared drug dosages and methods of administration. The quality of evidence is limited by small study size and high risk of bias. Thrombolytic therapy was probably better than placebo at restoring catheter function but there was no optimal dose or administration method. Physical disruption of a fibrin sheath may be equally effective as pharmaceutical thrombolytic agent for immediate management of catheter dysfunction. Catheter patency at two weeks is probably better following fibrin sheath stripping or catheter exchange compared to thrombolytic agent. Catheter exchange may be better than sheath disruption for long‐term catheter survival and the use of both techniques together is probably best. There is currently insufficient evidence favouring any technique in terms of either dialysis adequacy or reduced risk of adverse events.

Conclusions

Further research is required to adequately address the question of the most effective technique for haemodialysis catheter dysfunction.

Background

Description of the condition

The delivery of adequate haemodialysis (HD) in people with end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) is reliant upon vascular access, which may consist of arteriovenous fistula (AVF), arteriovenous graft (AVG) or central venous catheter (CVC). HD is preferably delivered via permanent access such as AVF or AVG due to long term durability; CVC are discouraged due to high rates of infectious and thrombotic complications as well as technical issues that limit their life span and significantly impact patient morbidity and mortality (D'Cunha 2004; Polkinghorne 2004; Rayner 2004).

The National Kidney Foundation's Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF‐DOQI) recommends less than 10% of prevalent dialysis patients should be reliant upon CVC (Vascular Access Guidelines 2006). However, 58% to 73% of patients initiate dialysis with a catheter and 10% to 40% continue to use a catheter 90 days after dialysis initiation(Ethier 2008). CVC use is predicted by female gender, older age, greater body mass index, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and smoking, as well as sub‐optimal practice patterns including delayed nephrology referral and reduced access to surgical resources (Ethier 2008; Mendelssohn 2006; Polkinghorne 2003). Furthermore, catheter use is rising among prevalent patients in many countries (Ethier 2008) and paradoxically increased in the USA in spite of the introduction of the Fistula First Initiative commenced by the National Coordinating Centre, largely due to an elevated rate of primary failure (Lok 2007). A recent report analysing the impact of the Fistula First Initiative found a greater dependence on CVC at 90 days after HD initiation (60%) compared with a decade ago (46%), as CVC are utilised as a bridge until AVF maturation (Lok 2007; Wasse 2007).

CVC use is associated with a three‐fold excess total mortality after adjustment for confounding factors (Polkinghorne 2004) and carries an elevated risk of serious infection and cardiovascular complication (Ishani 2005). While rates and mortality associated with catheter‐related bloodstream infections have declined in recent years, a substantial number of cases continue to occur. These occur particularly in outpatient HD settings, contributing to prolonged hospitalisation and significant health care associated costs (CDC Report 2011; Daniels 2013; Klevens 2007). Other significant consequences of using CVC include poor quality of life (Lopes 2007) and lower flow rates compared with AVF and AVG (Lee 2005) that result in reduced dialysis adequacy (Atherikul 1998; Kinney 2006; Kukavica 2009). CVC are likewise associated with increased rates of hospitalisation to address infection and other access complications (Daniels 2013; Di Iorio 2004; Fadrowski 2006). CVC longevity is limited by high rates of thrombosis and malfunction. On average, one year catheter survival is less than 50% (Little 2001; Thomson 2010) with 17% to 33% of catheters removed due to dysfunction (Alomari 2007; Kinney 2006; Little 2001) and nearly one in three catheters requiring intervention for malfunction (Xue 2013). The maintenance of catheter patency continues to be a major concern in the daily care of the HD patient.

Despite evidence of inferiority of CVC as long‐term vascular access, they have the significant advantage of being immediately usable. In cases of acute kidney injury (AKI) requiring dialysis or initial presentations of previously undiagnosed ESKD, wherein stabilisation and formation of AVG and AVF require months, CVC are necessary for interim access. In atypical circumstances where AVF and AVG are unable to be created or peritoneal dialysis is unfeasible, CVC are used as a last option for vascular access. Therefore, as with other vascular access, proper maintenance to prevent failure or the need for reinsertion is necessary.

Catheter malfunction is defined by KDOQI guidelines as "failure to attain and maintain an extracorporeal blood flow sufficient to perform HD without significantly lengthening the HD treatment" (KDOQI Guidelines 2006). Based on expert opinion, the Workgroup considered adequate extracorporeal blood flow to be equal to or greater than 300 mL/min in an adult patient(KDOQI Guidelines 2006). Other definitions incorporate venous pressures greater than 250 mm Hg and pre‐pump arterial pressures below 250 mm Hg, which may be incorporated into machine alarm settings, progressive declines in conductance as measured by blood flow and pre‐pump pressures, dialysis adequacy based on urea kinetics and other parameters (D'Cunha 2004; Mokrzycki 2010). Early mechanical dysfunction may include insertion of the catheter into the incorrect vessel or kinking of the catheter. Mechanical malfunction typically presents early (less than seven days) and can be avoided by proper placement under fluoroscopy and post‐procedure radiography to evaluate CVC position before use (Mokrzycki 2010). Late‐onset malfunction (more than seven days after catheter insertion) reflects thrombosis, fibrin sheath formation and infection. Thrombosis is the precipitating event in 30% to 40% of catheter malfunction (Vascular Access Guidelines 2006) and is responsible for up to two‐thirds of catheter failure (Swartz 1994; Trerotola 1997). Thrombosis often coexists with a fibrin sheath. Fibrin sheaths impede flow contributing to catheter malfunction but also promote thrombosis and the formation of biofilm, thereby contributing to catheter‐related infection (Faintuch 2008). The incidence of fibrin sheath ranges from 1.3% in the first seven days following catheter insertion to 75% at mean follow‐up of 98 days (Alomari 2007). Mural thrombi, including large atrial thrombi following bacteraemia are also recognised in CVC malfunction (Mokrzycki 2010). This review focused on late onset malfunction due to thrombosis and fibrin sheath formation as opposed to primary failure of the catheter.

Description of the intervention

Interventions for catheter malfunction include use of thrombolytic agents (TLA) instilled directly into the catheter lumen as well as fibrin‐sheath stripping, snare manoeuvres and catheter exchange techniques. The TLA evaluated to date include urokinase, streptokinase and the recombinant tissue type‐plasminogen activators (tPA) alteplase, reteplase, and tenecteplase.

Other approaches to catheter malfunction include mechanical disruption of the fibrin sleeve from the CVC wall or replacement of a malfunctioning catheter by over‐the‐wire catheter exchange and balloon angioplasty to disrupt the fibrin sheath.

How the intervention might work

The TLA act by cleaving the inactive pro‐enzyme plasminogen to the active enzyme plasmin which then degrades fibrin into soluble fibrin degradation products (Rijken 2009). tPA and urokinase‐type plasminogen activator are two distinct plasminogen activators within the blood. Their actions are physiologically inhibited by plasminogen activator inhibitor and by thrombin‐activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor. The advantage of tPA over urokinase and streptokinase is that tPA is fibrin‐specific and tPA bound to fibrin has greater affinity for and enzymatic activity on plasminogen (Rijken 2009). Alteplase is more fibrin specific than reteplase but its action is limited by a short half‐life of three to four minutes. Tenecteplase is theoretically even more potent that alteplase due to greater fibrin specificity as well as an increased resistance to plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (Mokrzycki 2010). In contrast, urokinase binds to and activates cell‐bound plasminogen. Due to difficulties with its manufacture it is frequently not available. Streptokinase is antigenic with repeated use and in those patients with high infection rates with streptococci, making it particularly problematic for use in Indigenous and low socioeconomic populations. It is associated with allergic reactions including hypotension (1% to 20%), pyrexia ± rigours (1% to 4%), and rarely, anaphylaxis (0.1%) (Mokrzycki 2010). When used intraluminally to restore CVC patency neither urokinase nor tPA alter systemic fibrinogen levels, fibrin degradation product, international normalised ratio, partial thromboplastin time, or platelet count (Atkinson 1990). While efficacious, these agents still have the potential to induce systemic fibrin breakdown and haemorrhage. However, most studies examining safety profiles of thrombolysis either by dwell or infusion observe low haemorrhage rates requiring therapy (Hemmelgarn 2011). Studies to date of heparin locks also document a low estimate of incidence of lock‐related bleeding events and usually only minimal bleeding requiring nominal therapy (Renaud 2015). The risk can be ameliorated through accurate documentation of catheter length at the time of placement in order to ensure an appropriate lock volume (Karaaslan 2001). TLA such as urokinase with a shorter half‐life offer a theoretical benefit with respect to passage of drug into circulation and subsequent risk of bleeding.

Fibrin sleeve stripping requires an invasive procedure. Traditional approaches require a femoral vein puncture with the fibrin sleeve disrupted using balloon angioplasty and embolectomy, pigtail stripping or snaring. A newer internal snare manoeuvre is a minimally invasive procedure that can be used to replace partially thrombosed CVC while simultaneously stripping the fibrin sleeve (Faintuch 2008; Mokrzycki 2010) by femoral vein puncture. Once fibrin is freed it typically flows towards the pulmonary arteries. While technical success rates are high, there are infrequent reports of clinical pulmonary emboli as well as case reports of septic pulmonary emboli secondary to the stripping procedure (Faintuch 2008).

Over‐the‐wire catheter exchange allows replacement of a malfunctioning catheter with a new patent catheter using the same track. Potential complications of this approach include recurrence of malfunction due to intact fibrin sheath, bleeding or haematoma along the tunnel track and infection (Faintuch 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

Catheter malfunction is associated with adverse patient outcomes including reduced dialysis adequacy, requirement of repeated invasive interventions with consequent reduced quality of life, increased risk of catheter‐related bacteraemia and higher rates of hospitalisation and mortality.

tPA has an established role in the prevention of catheter malfunction and has been demonstrated to be superior to heparin both for prevention of catheter malfunction as well as prevention of line‐related infection and bacteraemia (Hemmelgarn 2011). Systematic review and meta‐analysis in 2013 identified Hemmelgarn 2011 as the only randomised controlled trial (RCT) of tPA for the prevention of catheter malfunction (Wang 2013). A number of studies have evaluated the efficacy of various thrombolytic therapies (Donati 2012; Macrae 2005; Tumlin 2010) with promising results. The cost effectiveness of prophylactic use of recombinant tPA in addition to heparin compared with the use of heparin locking solution alone has also been appraised and concluded that overall costs of these two strategies were similar (Manns 2014). Cost of TLA is significant but there has been limited effort to date comparing the efficacy and cost efficiency of other TLA.

Three systematic reviews of TLA for use in the restoration of catheter patency following catheter malfunction exist to our knowledge (Clase 2001; Hilleman 2011; Lok 2006). These reviews support the use of alteplase and reteplase. Two of these reviews were performed more than 10 years ago (Clase 2001; Lok 2006) while the more recent systematic review excluded streptokinase and urokinase from evaluation and did not include studies involving children or published in languages other than English. These reviews did not compare other interventions such as fibrin sheath stripping and catheter exchange. The use and efficacy of these techniques have not been evaluated in systematic review.

We proposed a comprehensive and up‐to‐date review of interventions for management of catheter malfunction to answer the question "what is the most effective way to re‐establish vascular access in HD patients with late onset catheter malfunction?". Should the published data allow, we wish to explore the optimal way to administer thrombolytics such as short dwells versus push protocols, infusions or prolonged dwells between dialysis sessions.

Objectives

This review aimed to evaluate the benefits and harms of TLA, preparations, doses and administration as well as fibrin‐sheath stripping, over‐the‐wire catheter exchange or any other intervention proposed for management of tunnelled CVC malfunction in patients with ESKD on HD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Our review assessed all RCTs and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) that evaluated interventions for management of catheter malfunction. The first phase of cross‐over RCTs were also to be included. We anticipated small numbers of study participants and few published RCTs. The analysis was designed to address this.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

We focused on studies conducted in people with ESKD who rely on tunnelled CVC for either initiation or maintenance of HD access and who required restoration of patency in late‐onset (more than seven days) malfunctioning catheter. Catheter malfunction was defined as persistent inability to achieve a blood flow of greater than or equal to 300 mL/min despite positional changes of the patient and additional flushing, or both, or as defined by the study authors. Studies enrolling patients who had been treated previously with TLA or who are treated concurrently with anticoagulants or other prophylactic agents were included in the review.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies that enrolled patients who were receiving HD in intensive care units or for AKI. Studies involving patients with primary line malfunction (line unable to be used from insertion) were excluded.

Types of interventions

The review compared the therapeutic effect of any intervention for catheter malfunction, preparation, doses and administration for the restoration of catheter patency in patients with ESKD. The following comparisons of placebo or comparators were identified.

TLA

Fibrin sheath stripping

Over‐the‐wire catheter replacement.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Restoration of catheter flow

Interventions were to be evaluated for their efficacy in restoring line patency defined as ≥ 300 mL/min or adequate to complete a HD session or as defined by the study authors.

Secondary outcomes

Dialysis adequacy defined by urea reduction ratio (URR), dialysis clearance (Kt/V) or as defined by the study authors

Duration of hospitalisation

Catheter survival expressed as mean or median catheter patency or time to event measurement (length of time to re‐occlusion)

-

Adverse outcomes

Incidence of major bleeding, defined as reduction in haemoglobin (Hb) of 20 g/L, bleeding requiring blood transfusion, bleeding requiring hospital admission, or as defined by the study authors

Incidence of minor bleeding defined as a reduction in Hb of less than 20 g/L, bleeding not requiring hospital admission or transfusion, or as defined by the study authors

Infectious outcomes; infection related to vascular access, defined as catheter‐related exit site infection bacteraemia in the absence of another clear source of infection, or as defined by the study authors

Mortality outcomes: all‐cause mortality

Other adverse events including allergic reactions, urticaria and anaphylaxis

Other adverse events as defined by the study authors.

Economic cost to health service providers.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register up to 17 August 2017 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Specialised Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described obtained titles and abstracts of studies that were potentially relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were then screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable. Two authors independently assessed the retrieved abstracts and, if necessary the full text, of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancy between published versions was highlighted. Discrepancy in data extraction was resolved by a third adjudicating author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes such as restoration of catheter flow, restoration of catheter patency and mortality outcomes results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement are used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. dialysis adequacy or duration of hospitalisation), the mean difference (MD) were used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales have been used. However, if results are reported as time to a first event, we used time‐to‐event data to measure treatment effect.

For binary outcomes, such as restoration of catheter patency and all‐cause mortality, we compared proportion and 95% CI, and calculated numbers‐needed‐to‐treat and numbers‐needed‐to‐harm to establish a standardised, clinically relevant measure of data.

Unit of analysis issues

We analysed outcomes at the individual patient level. If the unit of randomisation was not the same as the level of analysis, that is, the patient, adjustments were made to address the potential impact of clustering on the outcome.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing corresponding author) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol population was carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. Heterogeneity was then analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I2 values is as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Where possible, funnel plots were used to assess for the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Data was pooled using a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were planned to explore possible sources of heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome were to include first versus multiple salvage attempts, by heterogeneity of study quality. Clinical heterogeneity among participants could be related to age and renal pathology (gender, ethnicity, diabetics versus non‐diabetics, smoking, vascular disease, BMI, age category, dialysis vintage and duration of catheter use prior to development of catheter malfunction). Heterogeneity in treatments could be related to prior agent(s) used and the agent, dose, method of administration and duration of therapy. Statistical heterogeneity in study design and risk of bias were evaluated. Adverse effects were tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques, as they are likely to be different for the various agents used. Where possible, the risk difference with 95% CI was calculated for each adverse effect, either compared to no treatment or to another agent.

Due to the low number of studies identified with small study sizes we were unable to perform subgroup analysis to explore possible sources of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias, as specified

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

Sensitivity analysis was not performed because no two studies compared the same intervention.

'Summary of findings' tables

We had planned to present the main results of the review in a 'Summary of findings' table. This table was to present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' table was also to include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). We planned to present the following outcomes.

Restoration of catheter flow

Dialysis adequacy

Duration of hospitalisation

Catheter survival

Adverse outcomes

We were unable to construct a "Summary of findings" table due to the wide variety of interventions used.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our search strategy identified 34 potentially relevant records. Twenty‐six studies (34 records) were identified for full‐text review. Eight studies (12 records; 580 participants) met our inclusion criteria (Donati 2012; Gray 2000; MacRae 2005; Merport 2000; Oliver 2007; Pollo 2016; TROPICS 3 Study 2010; Vercaigne 2012) and 16 studies (19 records) were excluded (Abraham 1997; CATHEDIA Study 2008; Coli 2006; Dahlberg 1986; Geron 2008; Gittins 2007; Haire 2004; ISRCTN00873351; Kaneko 2004; Khosroshahi 2015; Klouche 2007; Li 2014d; Mokrzycki 2001; Mokrzycki 2006; NCT00194181; Pervez 2002). Two studies (3 records) are awaiting assessment (Hammes 2001; Xue 2010). Hammes 2001 has only been published as two separate abstracts and the full text is required to clarify the number of patients randomised. The full‐text publication of Xue 2010 is not available and the results reported in the abstract are per device rather than per participant (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

TROPICS 3 Study 2010 compared thrombolytic therapy applied for a one‐hour dwell to restore catheter function was compared to placebo.

Donati 2012 compared low dose thrombolysis to high dose thrombolysis, each with a one‐hour intraluminal dwell time.

Pollo 2016 compared alteplase to urokinase; both thrombolytic agents had a 40 minute intraluminal dwell time.

MacRae 2005 compared the efficacy of a short (one hour dwell) versus a long thrombolytic dwell (36 to 48 hours) for restoring catheter function.

Vercaigne 2012 compared methods of thrombolytic administration and evaluated a "push" of TLA over 30 minutes against a "dwell" of 30 minutes.

Gray 2000 compared thrombolytic therapy with an intraluminal dwell time of 4 hours and 10 minutes with percutaneous fibrin sheath stripping.

Merport 2000 compared fibrin sheath stripping to over‐the‐wire catheter exchange.

Oliver 2007 compared over‐the‐wire catheter exchange with and without angioplasty sheath disruption.

No two studies compared the same interventions so meta‐analysis could not be undertaken. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Excluded studies

Seven studies investigated prevention rather than treatment of catheter dysfunction (Abraham 1997; Coli 2006; Geron 2008; Gittins 2007; Kaneko 2004; Li 2014d; Mokrzycki 2001). Seven studies involved the wrong patient population (CATHEDIA Study 2008; Dahlberg 1986; Haire 2004; Khosroshahi 2015; Klouche 2007; Mokrzycki 2006; Pervez 2002). One study was abandoned after publication of its protocol and remains incomplete due to poor recruitment (ISRCTN00873351) and one study was terminated (NCT00194181). See Characteristics of excluded studies

Risk of bias in included studies

In general most studies tended to have a high risk of bias due to poor (or poorly reported) study design, broad inclusion criteria, low patient numbers and industry involvement. See Figure 2; Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Randomisation methods included computer‐generated randomisation schedule (Gray 2000; Merport 2000), dynamic algorithm (TROPICS 3 Study 2010), or block randomisation in groups of four by a biostatistician (MacRae 2005; Vercaigne 2012). Donati 2012 was judged to be at high risk of bias, and risk of bias was unclear in Pollo 2016 (stated it was randomised however the method of randomisation was not reported).

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was judged to be low risk of bias in three studies (Oliver 2007; Pollo 2016; Vercaigne 2012) where the investigators employed the use of opaque envelopes to conceal treatment allocation or instructed interventional radiologists not to reveal the procedure performed. Three studies were judged to be at high risk of bias (Donati 2012; Gray 2000; MacRae 2005) and in two studies the risk of bias was unclear (Merport 2000; TROPICS 3 Study 2010).

Blinding

One study stated the participants, investigators and outcome assessors were blinded through a "Double‐blind" methodology and were low risk for performance and detection bias (Oliver 2007). Five studies were open‐label and hence had a high risk of bias (Donati 2012; Gray 2000; MacRae 2005; Pollo 2016; Vercaigne 2012). Blinding of participants or investigators could not be determined in two studies (Merport 2000; TROPICS 3 Study 2010).

Incomplete outcome data

In most studies follow‐up and management of incomplete data was generally poor with many patients being lost to follow‐up, withdrawing from the studies, early termination of the study or crossing over interventions (Donati 2012; Gray 2000; MacRae 2005Merport 2000; Pollo 2016; Vercaigne 2012) or inadequately described (unclear risk) (Oliver 2007). One study was judged to have a low risk of attrition bias (TROPICS 3 Study 2010).

Selective reporting

Four studies had poorly defined outcomes and incomplete reporting of outcomes (Donati 2012; MacRae 2005; Merport 2000; Oliver 2007). Three studies were judged to be at low risk of bias (TROPICS 3 Study 2010; Pollo 2016; Vercaigne 2012) and one study was judged unclear (Gray 2000).

Other potential sources of bias

Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship contributed to a high risk of bias in four studies (Gray 2000; Oliver 2007; TROPICS 3 Study 2010; Vercaigne 2012). In three studies there was under‐recruitment, patient cross‐over from one treatment arm to the other and a difficult experimental protocol leading to early termination of the study and high risk of bias (MacRae 2005; Merport 2000Vercaigne 2012). Risk of bias was judged to be low in two studies (Donati 2012; Pollo 2016).

Effects of interventions

Thrombotic therapy versus placebo

Thrombolytic therapy for restoration of catheter function was compared to placebo in one study (TROPICS 3 Study 2010).

One hundred and fifty one patients with dysfunctional cuffed, tunnelled HD catheters were randomised to 2 mg tenecteplase or placebo. The primary outcome was treatment success defined as blood flow rate ≥ 300 mL/min and an increase of ≥ 25 mL/min above baseline. The study underwent a protocol amendment introducing the utilisation of open‐label tenecteplase at the end of treatment one so the secondary outcomes were not considered appropriate for this review. A significant proportion of included patients had primary line dysfunction. The use of thrombolytic therapy was reported to be superior at restoring line function when compared to placebo (Analysis 1.1 (149 participants): RR 4.05, 95% CI 1.42 to 11.56). Catheter survival as defined by this study was not appropriate for analysis. There was no demonstrated difference in rate of adverse events (Analysis 1.2 (149 participants): RR 2.03, 95% CI 0.38 to 10.73).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Thrombolytic therapy versus placebo, Outcome 1 Treatment success.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Thrombolytic therapy versus placebo, Outcome 2 Adverse events.

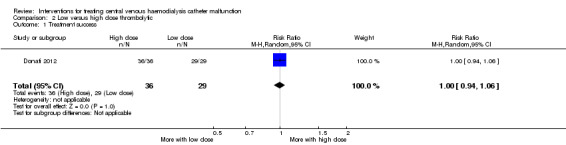

Low versus high dose thrombolytic

Low versus high dose thrombolytic agents were compared in one study (Donati 2012).

Patients with tunnelled cuffed catheter line dysfunction and on warfarin with a target INR of 1.8‐2.5 were randomised to receive low dose or high dose urokinase catheter lock. Patients underwent chest X‐ray to exclude line dysfunction caused by line misplacement. This study reported no detected difference in efficacy of low dose or high dose thrombolytic therapy (Analysis 2.1 (65 participants): RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.06). The study authors however concluded that higher dose urokinase was superior based on post‐treatment blood flow rates. For the purposes of our review this was not considered a valid outcome. Similarly, this study reported superior catheter survival with high dose urokinase but catheter survival was not censored for catheter removal due to dialysis modality change, transplantation or use of an AV fistula or graft so was not appropriate for analysis in this review. There were no adverse events reported in either treatment group.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Low versus high dose thrombolytic, Outcome 1 Treatment success.

Alteplase versus urokinase

Alteplase was compared to urokinase for restoration of catheter function in one study (Pollo 2016).

One hundred patients receiving chronic HD through tunnelled CVC with complete occlusion of the catheter were randomised to receive 1 mg/mL alteplase or 5000 IU/mL urokinase intraluminal dwell for 40 minutes. There were no reported differences in treatment success (Analysis 3.1 (100 participants): RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.33), catheter survival (Analysis 3.2 (100 participants): RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.45), or adverse outcomes (Analysis 3.3 (100 participants): RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.76).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alteplase versus urokinase, Outcome 1 Treatment success.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alteplase versus urokinase, Outcome 2 Catheter survival.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alteplase versus urokinase, Outcome 3 Adverse events.

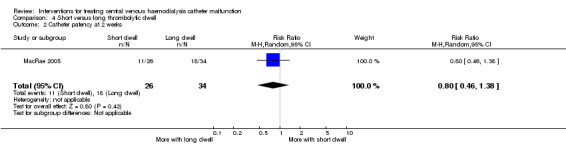

Short versus long thrombolytic dwell

The efficacy of a short versus a long thrombolytic dwell with alteplase for restoring catheter function was compared in one study (MacRae 2005).

Sixty patients with either cuffed or non‐cuffed catheters were randomised to receive either 1 or > 48 hour alteplase dwell. The study was terminated prematurely due to the impracticality of a short dwell. There was no detected difference reported in immediate treatment success (Analysis 4.1 (60 participants): RR 0.97 95% CI 0.74 to 1.27) or catheter patency at two weeks post intervention (Analysis 4.2 (60 participants): RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.38). There was no reported difference in median catheter survival (see Table 1) P = 0.621. The authors did not report adverse events.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Short versus long thrombolytic dwell, Outcome 1 Treatment success.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Short versus long thrombolytic dwell, Outcome 2 Catheter patency at 2 weeks.

1. Studies reporting nonparametric data: catheter survival.

| Gray 2000 | Intervention: urokinase | Comparison: fibrin sheath stripping | ||||

| Median | 95% CI | No. of participants | Median | 95% CI | No. of participants | |

| 42 days | 22 to 364 days | 29 | 32 days | 18 to 48 days | 28 | |

| MacRae 2005 | Intervention: short alteplase dwell | Comparison: long alteplase dwell | ||||

| Median | Range | No. of participants | Median | Range | No. of participants | |

| 14 days | 4 to 83 days | 26 | 18 days | 4 to 77 range | 34 | |

| Oliver 2007 | Intervention: sheath disruption | Comparison: no disruption | ||||

| Median | SD (or other variance) | No. of participants | Median | SD (or other variance) | No. of participants | |

| 411 days | Not reported | 18 | 198 days | Not reported | 12 | |

Thrombolytic administration

Methods of thrombolytic administration were compared in one study (Vercaigne 2012).

In this under‐recruited study, patients with dysfunctional HD catheters in situ at least 14 days were randomised to alteplase instilled to the catheter lumen for 10 minutes followed by saline flush (push protocol) or 30 minute alteplase dwell. There was no difference detected in terms of treatment success (Analysis 5.1 (82 participants): RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.64) nor dialysis adequacy as defined by Kt/V (Analysis 5.2 (57 participants): MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.18).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Thrombolytic push versus thrombolytic dwell, Outcome 1 Treatment success.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Thrombolytic push versus thrombolytic dwell, Outcome 2 Change in Kt/V.

Thrombolytic therapy versus percutaneous fibrin sheath stripping

Thrombolytic therapy was compared to percutaneous fibrin sheath stripping in one study (Gray 2000).

Fifty‐seven patients with poorly functioning dialysis catheters were randomised to urokinase infusion or fibrin sheath stripping in an open‐label study. There was no reported difference reported in either treatment success (Analysis 6.1 (57 participants): RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.07) or adverse events (Analysis 6.2 (57 participants): RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.16 to 6.86). Catheter survival expressed as median duration of adequate catheter function demonstrated a trend favouring thrombolytic therapy (42 days (95% CI 22 to 364) versus 32 days (95% CI 18 to 48 days), no P value was reported (see Table 1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Fibrin sheath stripping versus thrombolytic therapy, Outcome 1 Treatment success.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Fibrin sheath stripping versus thrombolytic therapy, Outcome 2 Adverse events.

Fibrin sheath stripping versus over‐the‐wire catheter exchange

Fibrin sheath stripping was compared to over‐the‐wire catheter exchange in one study (Merport 2000).

Thirty‐seven episodes of catheter dysfunction occurring in 30 patients were randomised in an open‐label study. There were multiple episodes of treatment cross‐over. The primary outcome was treatment success defined as a blood flow rate ≥ 200 mL/min (note this is a lower accepted blood flow rate compared to other studies' definitions of success). There was no reported difference detected in the two treatments with respect to either immediate treatment success (Analysis 7.1 (37 participants): RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.10) or adverse events (Analysis 7.2 (37 participants): RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.06 to 4.26). Catheter survival was reported to be superior following catheter exchange (Analysis 7.3 (37 participants): MD ‐27.70 days, 95% CI ‐51.00 to ‐4.40).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Fibrin sheath stripping versus over‐the‐wire catheter exchange, Outcome 1 Treatment success.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Fibrin sheath stripping versus over‐the‐wire catheter exchange, Outcome 2 Adverse events.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Fibrin sheath stripping versus over‐the‐wire catheter exchange, Outcome 3 Catheter survival.

Sheath disruption versus exchange alone

One study compared over‐the‐wire catheter exchange with and without angioplasty sheath disruption (Oliver 2007).

Thirty HD patients using a tunnelled cuffed catheter with catheter dysfunction and angiographically‐demonstrated fibrin sheaths were randomised to undergo sheath disruption following by catheter exchange or catheter exchange alone. Catheter survival was reported to be significantly improved by utilisation of the sheath disruption technique compared to catheter exchange alone (Analysis 8.1 (30 participants): MD 213.00 days, 95% CI 205.70 to 220.30) but there was no clinically or statistically significant difference reported in dialysis adequacy as defined by URR (Analysis 8.2 (30 participants): MD 6.00, 95% CI ‐1.30 to 13.30) (See Table 1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sheath disruption versus exchange alone, Outcome 1 Catheter survival.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sheath disruption versus exchange alone, Outcome 2 Clearance in URR.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review indicates that thrombolytic therapy may be superior for restoring catheter function when compared to placebo but there is no data available to suggest an optimal dose or administration method. Physical disruption of a fibrin sheath using interventional radiology techniques appears to be equally efficacious to use of a pharmaceutical thrombolytic agent for immediate management of dysfunctional catheters. Catheter patency at two weeks is poor following use of thrombolytic agents and is improved significantly by fibrin sheath stripping or catheter exchange. Catheter exchange is probably superior to sheath disruption with respect to catheter survival and the use of both techniques together (both catheter exchange and fibrin sheath disruption) may further improve catheter survival over catheter exchange alone. There is insufficient evidence to suggest any specific intervention is superior in terms of ensuring either dialysis adequacy or reduced risk of adverse events.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The data on the treatment of catheter dysfunction remains incomplete. This review summarises a small body of research that represents some poor quality data and fails to compare data from multiple studies. The included studies contain multiple problems in methodology, small sample size and single centre settings, leading to concerns regarding external validity. There remain many further questions regarding to optimal dosing of thrombolytic agents, as well as preferred administration method and optimal technique to maintain catheter patency. To date there are no data regarding the economic impact of repeated pharmacological interventions with limited duration of efficacy compared to catheter exchange which appears to offer superior catheter survival, albeit at a procedural cost.

Quality of the evidence

The strength of this review rests on the breadth of the literature search which included non‐English language studies. This is the first systematic review to cover different treatment modalities to address the problem of HD catheter dysfunction. Other reviews have focused on the role of thrombolytic agents (Hilleman 2011; Lok 2006). The current review is limited by the small number of available studies answering particular questions and some design features of the included studies. Several studies included catheters that were not cuffed or tunnelled. The problem of primary catheter failure due to poor insertion technique may have had a very significant impact on the outcomes of studies and may explain the level of heterogeneity in some of the results. Most of the studies included in this review were judged to have a high risk of bias and were potentially influenced by pharmaceutical industry involvement.

Potential biases in the review process

We have attempted to avoid bias in our review process, including all studies that are available in the area. They have been examined with standard processes.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Two previous reviews have covered some of the subjects addressed in this current review. Both of these studies focused on the role of thrombolytic agents only and did not address physical methods for restoring catheter function such as fibrin sheath disruption or over‐the‐wire catheter exchange. To our knowledge there has been no previous systematic review of evidence supporting these techniques.

In the earlier of these thrombolytic agent reviews, Lok 2006 included multiple retrospective or non‐randomised prospective studies. As in our review, they reported good immediate success in restoring catheter function with the use of thrombolytic agents delivered in either a push or dwell protocol. They failed to identify any published studies that compared these two administration methods and suggested that either method is a reasonable option for patients presenting for dialysis requiring thrombolytic treatment. They likewise were unable to identify an optimal thrombolytic agent, dose or superiority when considering log dwells versus infusion protocols.

In the more recent of these reviews Hilleman 2011 also reported good immediate treatment success with use of thrombolytic agents and concluded that reteplase and alteplase were superior in efficacy to tenecteplase. Their review was heavily reliant upon observational, non‐randomised studies. They likewise report few or no serious adverse bleeding events attributed to thrombolytic therapy and concluded that reteplase is most cost effective in the hospital setting for dysfunctional HD catheters based on data from observational, retrospective uncontrolled and open‐label studies (Hilleman 2011). Such limitations also precluded a formal meta‐analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Thrombolysis, fibrin sheath disruption and over‐the‐wire catheter exchange are effective and appropriate therapies for immediately restoring catheter patency in dysfunctional cuffed and tunnelled HD catheters. Clinical approach using any or all of these interventions should be defined by local clinical practice and limitations imposed by medication availability and finances. On current data there is no evidence to support physical intervention over the use of pharmaceutical agents in the acute setting. Pharmacological interventions appear to have a bridging role and long term catheter survival appears to be improved by fibrin sheath disruption and is superior following catheter exchange. There is no data favouring any of these approaches with respect to dialysis adequacy or risk of adverse events. Of note, there is no evidence to suggest thrombolysis carries a significantly increased risk of bleeding events.

Implications for research.

Further research is required to adequately address the question of the most efficacious and clinically appropriate technique for HD catheter dysfunction. Despite the frequency with which catheter dysfunction occurs, studies of interventional techniques are difficult to carry out due to the relative emergent need for restoring catheter function as well as pragmatic considerations including nursing time demands and access to interventional radiology. Consequently, there is a need for simple experimental protocols and straight‐forward consent procedures as well as broad collaboration across hospital departments to attain patient numbers for adequately powered studies. Appropriately powered multicentre RCTs should be undertaken in order to derive meaningful evidence based data to inform clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the referees and editor for the comments and feedback during the preparation of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimisation (minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. sub‐scales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Thrombolytic therapy versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment success | 1 | 149 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.05 [1.42, 11.56] |

| 2 Adverse events | 1 | 149 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.03 [0.38, 10.73] |

Comparison 2. Low versus high dose thrombolytic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment success | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.94, 1.06] |

Comparison 3. Alteplase versus urokinase.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment success | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [1.01, 1.33] |

| 2 Catheter survival | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.01, 1.45] |

| 3 Adverse events | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.56, 1.76] |

Comparison 4. Short versus long thrombolytic dwell.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment success | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.74, 1.27] |

| 2 Catheter patency at 2 weeks | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.46, 1.38] |

Comparison 5. Thrombolytic push versus thrombolytic dwell.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment success | 1 | 82 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.97, 1.64] |

| 2 Change in Kt/V | 1 | 57 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.18, 0.18] |

Comparison 6. Fibrin sheath stripping versus thrombolytic therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment success | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.80, 1.07] |

| 2 Adverse events | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.16, 6.86] |

Comparison 7. Fibrin sheath stripping versus over‐the‐wire catheter exchange.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment success | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.78, 1.10] |

| 2 Adverse events | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.06, 4.26] |

| 3 Catheter survival | 1 | 37 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐27.70 [‐49.00, ‐4.40] |

Comparison 8. Sheath disruption versus exchange alone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Catheter survival | 1 | 30 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 213.0 [205.70, 220.30] |

| 2 Clearance in URR | 1 | 30 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 6.0 [‐1.30, 13.30] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Donati 2012.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group:

Other interventions (both groups)

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Unclear when and how many patients were randomised and when they were consented 81 patients enrolled, 72 completed the study. Only 65 thrombotic events |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | "Open label" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | "Open label" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | "Open label" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | "Among 81 stable HD patients enrolled, only 72 completed the study due to nine deaths with functioning TCC". Unclear which treatment group these 9 belonged to Only 65 of these had a dysfunctional catheter |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Different outcomes reported on than stated in methods Outcomes not clearly described Incomplete data with respect to timing Reporting of outcomes that were not pre‐specified |

| Other bias | Low risk | Study appears free of other biases |

Gray 2000.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "A computer‐generated randomisation schedule was used to assign patients to the UK infusion or stripping group after transcatheter venography showed satisfactory catheter position and no mechanical problems such as kinking". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No attempt to conceal |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No attempt to conceal; no sham procedures Appear unmatched: femoral approach and interventional radiology versus minimally invasive infusion. Sedative drugs used for interventional radiology versus 4 h infusion with no other drugs |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No sham procedures described; no attempt made at blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Did not specify duration of follow‐up or how incomplete data was managed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Did not specify how to deal with incomplete data |

| Other bias | High risk | Funded by pharmaceutical company Under‐recruited and early termination of study |

MacRae 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Both groups

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “The patients were block randomised (by blocks of four in a consecutive fashion) to receive either a 1‐ or a 48‐ to 72‐hour tPA dwell”. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Non‐blinded study |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Non‐blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Non‐blinded study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Early termination |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Non‐blinded study; 1‐hour dwell felt to be impractical and labour intensive |

| Other bias | High risk | Clear preference from a service delivery perspective for the convenience of the longer dwell. “At six months after enrolment, review of the study protocol with nursing staff was undertaken. At that time there were multiple issues raised from a practical trial execution perspective that led to early termination of the study. Specifically, the 1‐hour dwell was impractical, time‐consuming and labour intensive (30‐45min to confirm CD and order tPA, 45 min to thaw and the 60‐min dwell) After that tPA dwell, patients often only had 60 to 90 minutes of remaining dialysis. Given the impracticality of the 1‐hr dwell design the study enrolment was stopped after only 60 patients…” |

Merport 2000.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Patients were randomised by a custom computer program designed to maintain balance throughout patient accrual (permuted block design with eight‐item blocks)” Patients were randomised based on the intention to treat malfunctioning catheters; randomisation process occurred before the patient was examined by the physician, or underwent chest fluoroscopy |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | “Two patients were lost to follow‐up (one PFSS and one EX) and one (PFSS) had discrepancies between hospital records and haemodialysis records that could not be reconciled. Follow‐up data from this last patient were discarded.” Large number lost to follow‐up “13 patients in the PFSS group were followed for at least 1 month, 9 of whom lost patency in that time... 14 patients in the EX group were followed‐up for at least 1 month, but only one patient lost patency in that time |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No reporting of complications post 30 days Reported cost of interventions but not pre‐specified outcome |

| Other bias | High risk | High rates of cross‐over |

Oliver 2007.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Patients with sheaths were randomly assigned to either catheter exchange over a guidewire or exchange over a guidewire with angioplasty sheath disruption... The randomisation schedule was stratified by side of catheter (left sided catheters are at higher risk for dysfunction) using a block‐of‐four design |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Radiologists were instructed to maintain blinding during the procedure by not informing patients of the presence of sheath or disruption |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | After the procedure, the radiologist completed a case report form describing the procedure and sealed it in an envelope to maintain blinding of the research coordinator who performed follow‐up in the HD unit |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Radiologists were instructed to maintain blinding during the procedure by not informing patients of the presence of sheath or disruption After the procedure, the radiologist completed a case report form describing the procedure and sealed it in an envelope to maintain blinding of the research coordinator who performed follow‐up in the HD unit |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement’ |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Reported on mean blood flow and urea reduction ratio but these were not prespecified outcomes |

| Other bias | High risk | Pharmaceutical sponsorship |

Pollo 2016.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Study was described as randomised, method of randomisation was not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomisation was performed using sealed envelopes according to the CONSORT rules" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | "Modified intention to treat population, which included all randomised patients who received at least one dose of [drug]" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Study appears free of other biases |

TROPICS 3 Study 2010.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Eligible patients were randomised within three strata to minimise potential confounding effects of baseline BFR on treatment efficacy. Within each stratum, patients were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive tenecteplase or placebo using a hierarchical, dynamic algorithm implemented through an interactive voice response system. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Minimal loss to follow‐up and equal numbers in each arm |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Pre‐specified outcomes (of interest to this review) were reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Drug company sponsored |

Vercaigne 2012.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Block randomization in groups of 4 was performed by a biostatistician” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Opaque envelopes were prepared centrally as per the randomization scheme and delivered to each study centre. Consented patients were randomly allocated to one of the two treatment groups/; the alteplase dwell or the alteplase push protocol. As patients presented with catheter dysfunction, envelops were removed in order from the storage container to reveal the patient’s randomization group”. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No mention of sham treatment; assume not blinded to treatment received |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Assessed by non‐blinded nursing staff |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Incomplete secondary end points |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Pre‐specified outcomes (of interest to this review) were reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Drug company sponsorship |

AVF ‐ arteriovenous fistula; BFR ‐ blood flow rate; CVC ‐ central venous catheter; ESA ‐ erythropoietin stimulating agent; HD ‐ haemodialysis; ICU ‐ intensive care unit; INR ‐ international normalized ratio; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis; RCT ‐ randomised controlled trial; TC ‐ tunnelled‐cuffed; tPA ‐ tissue plasminogen activator

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|