1. Introduction

Males and females have been consistently reported to differ on aspects of emotional memory (Buck et al., 1974; Fujita et al., 1991; Hall and Matsumoto, 2004; Kring and Gordon, 1998; Seidlitz and Diener, 1998), and spatial ability (Astur et al., 1998; Beatty, 1984; Dawson et al., 1975; Galea and Kimura, 1993; Grön et al., 2000; Isgor and Sengelaub, 1998; Jonasson, 2005; Linn and Petersen, 1985; Postma et al., 2004; Voyer et al., 1995). Buttressing these differences in behavior and memory are findings that the predominant neural regions for each of these cognitive domains, the amygdala for emotional memory (for review see, Roozendaal and Hermans, 2017) and hippocampus for spatial abilities (among other abilities; for review see, Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2014), also are reported to show morphological and/or functional differences depending on sex (for amygdala see, Cahill et al., 2001; Cahill et al., 2004; Canli et al., 2002; Killgore and Yurgelun-Todd, 2001; Kilpatrick et al., 2006; Stevens and Hamann, 2012; for hippocampus see, Isgor and Sengelaub, 1998; Jacobs et al., 1990; Pfaff, 1966; but see, Gur et al., 2002; Tan et al., 2016).

These sex differences in emotional memory and spatial ability have typically been considered as arising from independent and separate brain mechanisms (but see, Pletzer, 2014, 2015; Pletzer et al., 2017). However, in this paper we discuss the parallels between the nature of the sex differences in the two domains and a third domain (perceptual processing) and evaluate potential general mechanisms that might lead to systemic sex differences across these domains.

Recently, sex differences have also been reported in perceptual processing and hemispheric brain activation associated with perceptual processing (Kimchi et al., 2009; Kramer et al., 1996; Müller-Oehring et al., 2007; Pletzer and Harris, 2018; Pletzer et al., 2013; Pletzer et al., 2014; Roalf et al., 2006; Scheuringer and Pletzer, 2016). Here, perceptual processing refers to the order of processing of a scene, where the global scene, or the scene as a whole, is processed before local information, or the detail items that make up the scene (Navon, 1977, 1981). Interestingly, sex differences in global-to-local processing are also seen in both the emotional and spatial domains. In the domain of emotional memory, women show a bias towards “detail” and men show a bias towards “gist” (Cahill and van Stegeren, 2003; Nielsen et al., 2013, 2014; Nielsen et al., 2011). The domain of spatial abilities does not share the same parallels in nomenclature observed in emotional memory, however, there is evidence suggesting that global-to-local processing performance is related to some forms of spatial ability, such as performance on the Judgment of Line Orientation Test (Basso and Lowery, 2004). As a result, sex differences in visuo-spatial processing and the accompanying sex differences in the brain while processing global-to-local stimuli have been proposed to account for sex differences in other cognitive domains including spatial abilities and emotional memory (Pletzer, 2014; Pletzer et al., 2013).

There are likely widespread and complex mechanisms underlying these similar sex differences across cognitive domains and the brain. We propose that sex differences in the locus coeruleus (LC) structure and function (Bangasser et al., 2010; Bangasser et al., 2011; Curtis et al., 2006; De Blas et al., 1990; Guillamón et al., 1988; Pinos et al., 2001) contributes to sex differences in encoding and retrieval processes via the many connections the pontine nucleus shares with both the amygdala, hippocampus, and throughout the brain (Abercrombie et al., 1988; Aston-Jones, 2004; Buffalari and Grace, 2007; Canteras et al., 1995; Cedarbaum and Aghajanian, 1978; Jones and Moore, 1977; Loughlin et al., 1986a; Loughlin et al., 1986b; Morrison et al., 1978; Pasquier and Reinoso-Suarez, 1978; Segal and Landis, 1974; Segal et al., 1973; Wallace et al., 1992).

The LC is relevant for understanding how sex differences occur in preferences for details vs. gist because the LC helps identify and re-orient attention to salient stimuli in the environment (for reviews see, Roozendaal and Hermans, 2017; Sara, 2009; Sara and Bouret, 2012) and selectively increases processing of salient stimuli via interactions with local cortical salience signals (Mather et al., 2016). However, despite parallels in sex differences across cognitive domains and the ability of the LC to influence what information is identified as salient and how strongly it is weighted, little work has been geared towards understanding whether and how the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine (LC-NE) system might contribute to any parallel sex differences in memory processes. In this review, we first summarize sex differences in these three disparate domains of emotional memory, spatial ability, and perceptual processing. We then summarize sex differences in brain morphology, function, and/or activation related to each of these domains, followed by discussion of possible mechanisms contributing to parallels in sex differences across cognitive domains and the brain.

2. Sex differences in gist and detail memory are observed across domains

2.1. Defining gist versus detail memory

Gist and detail memory are defined as follows; gist refers to the information central to the event, or, “any fact or element pertaining to the ‘basic story’ that could not be ‘changed or excluded without changing the basic story line’” (Heuer and Reisberg, 1990, pg. 499), while detail refers to peripheral information that has no bearing on the context of the story line (Heuer and Reisberg, 1990). Heuer and Reisberg (1990) showed participants a slideshow, with each slide having a short accompanying narrative. The images and accompanying narrative either had an emotional component or not. In the non-emotional version, a mother and son visit the son’s father at a garage where he is a mechanic and is fixing a broken-down car shown in an earlier slide. In the emotional version, the mother and son visit the son’s father at a hospital where he is a surgeon and is operating on a victim of a car accident shown in an earlier slide. Memory for gist and detail information was enhanced for the emotional story over the neutral story. As we will review below, this emotion-related enhancement for gist and detail information differs between men and women and may relate to sex differences in other aspects of episodic memory, with parallels in sex differences even extending to perceptual processing.

2.2. Gist and Detail: sex differences in emotional memory

Research suggests that men and women process and communicate emotional information differently. For instance, women are reported to more accurately communicate emotional information nonverbally (Buck et al., 1974), show more facial expressivity despite reporting the same amount of emotion as men (Kring and Gordon, 1998), are more accurate at identifying emotional expressivity in others (Hall and Matsumoto, 2004), experience greater affect intensity (Fujita et al., 1991), and recall more positive and negative life events than men (Fujita et al., 1991). Yet the underpinnings of such behavioral differences have only been examined recently, with studies showing that these sex differences do not stop at expressivity but extend to what type of information is encoded and retrieved under emotional circumstances. The differences in encoding and retrieval seem to reside mainly in what features of emotional stimuli are remembered, typically studied in the context of emotional scenes or situations. In particular, as will be reviewed below, women appear to show preferential encoding and retrieval of item details for emotional stimuli encountered in the lab and emotional autobiographical memories. In contrast, men appear to preferentially encode and retrieve more gist-like information from the same experiences.

2.2.1. Sex differences in gist and detail memory for autobiographical memories

While Heuer and Reisberg (1990) examined memory for gist and detail in the laboratory without concern for sex of participants, as outlined below, others have reported sex differences in recall patterns associated with gist and detail in autobiographical memories.

Findings that women recalled more positive and negative life events than men (Fujita et al., 1991), raises the question of at what stage of information processing such differences occur. For instance, a difference in recall performance can stem from differences in encoding, organization, retrieval, and/or response generation. A series of three studies eliminated a number of potential explanations, including sex differences in response generation, mood congruence between memory valance and current mood, tendency to ruminate, and even sex differences in semantic memory (Seidlitz and Diener, 1998). A lack of sex differences in semantic memory juxtaposed against sex differences in autobiographical memory in the same people suggests that women and men may be encoding life events differently. To test this possibility, participants were instructed to log event descriptions at the end of each day over a 6-week journaling period. When asked to recall as many journaled events as possible, men and women recalled a similar number of events, however, women recalled more positive events, while men reported more repeat events than women, suggesting they may not differentiate events to the same degree as women (Seidlitz and Diener, 1998). A word count for each event logged over the 6-week journaling period revealed a significant sex effect on the amount of detail recorded for events, with women recording more detail per event than men(Seidlitz and Diener, 1998), suggesting that women may encode more peripheral detail information in their daily life (e.g., I went to dinner at The District with Dave) whereas men may encode more gist-type information (e.g., I went to dinner with a friend).

2.2.2. Sex differences in gist and detail emotional memory in the laboratory setting

The tendency for women to record more detail for autobiographical events than do men (Seidlitz and Diener, 1998) has also been observed in the laboratory setting for emotional information. In particular, Cahill and colleagues have used the three-phase story1 to better understand what features of emotional information men and women are more likely to recall.

After exposure to the emotional version of the three-phase story, men recalled more gist information (e.g., the mother and son were leaving the house), while women recalled more peripheral detail information (e.g., the mother and son were standing in front of a house with a blue door; Nielsen et al., 2013). These mnemonic effects appeared to be modulated by sex hormones, as women only differed from men during the high-female-sex-hormone luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Women tested during the low-female-sex-hormone follicular phase of the menstrual cycle showed no preference for one type of information over the other, exhibiting similar recall rates for gist and detail information. Consistent with this finding, women’s hormonal contraceptive status also relates to differences in gist versus detail recall (Nielsen et al., 2014; Nielsen et al., 2011). Both studies found that women using hormonal contraception performed similarly to men, showing better recall of gist information in the emotional condition. In contrast, women not using hormonal contraception, and who therefore had higher endogenous female sex hormones, showed better memory for detail information in the emotional condition. Interestingly, in each of Nielsen et al.’s aforementioned studies, pupil and eye tracking data indicated that all groups showed similar attention and arousal while viewing the slideshow, suggesting that sex differences in gist versus detail memory profile are not driven by differences in attention but rather by differences in how the same information is encoded, consolidated and/or later retrieved.

2.3. Orientation and Landmarks: Gist and detail in spatial abilities

There has been much research on sex differences in spatial abilities, with men outperforming women on some but not all tasks (Jonasson, 2005; Linn and Petersen, 1985; Voyer et al., 1995). Gonadal and stress hormones influence these behavioral differences, and show interactions as well in studies of sex differences in spatial memory (Bowman et al., 2003; Bowman et al., 2001; Conrad et al., 2004; Luine et al., 1994; Shors et al., 1998; Williams et al., 1990; Wood et al., 2001). In the following sections, we first review evidence of sex differences in spatial memory under non-stressful conditions. We then discuss how these differences in spatial memory may be explained by differences in gist and detail memory biases in males and in females.

2.3.1. Sex differences in spatial ability

A great deal of work on sex differences in spatial memory has been conducted in animals. A reliable finding across many of these studies is that males outperform females on a battery of spatial tasks, such as the radial arm maze, symmetrical maze, and the Morris water maze (Beatty, 1984; Dawson et al., 1975; Isgor and Sengelaub, 1998). In humans, even though it has been demonstrated that males perform better on various measures of spatial ability and spatial memory, the particular components of spatial memory giving rise to these sex differences are still unclear (Postma et al., 1999). However, as will be reviewed below, the pattern of males outperforming females does not hold true for every measure of spatial ability (Eals and Silverman, 1994; Galea and Kimura, 1993; James and Kimura, 1997; McBurney et al., 1997; Silverman and Eals, 1992).

Clear sex differences in humans have been identified in tasks measuring route learning, mental rotation, and spatial perception, with males outperforming females (Astur et al., 1998; Galea and Kimura, 1993; Grön et al., 2000; Linn and Petersen, 1985; Postma et al., 2004). Men also are reported to outperform women on spatial working memory tasks. For instance, in the Corsi Block-Tapping task, a task requiring the participant to repeat back a sequence of taps on a set of spatially separated blocks, men show significantly larger spatial working memory spans than women evidenced by men completing increasingly longer spatial sequences than women (Capitani et al., 1991; Orsini et al., 1986; Orsini et al., 1987).

However, this pattern of better performance by men is less consistent in tasks of object location memory, as women often remember the locations of objects better (Eals and Silverman, 1994; James and Kimura, 1997; Silverman and Eals, 1992)and tend to recall more landmarks visible on maps (Galea and Kimura, 1993). Women also outperform men on a memory game that relies on remembering the location of a previously seen item in a grid (McBurney et al., 1997).

As observed with emotional memory, gonadal hormones appear to play an important role in the observed sex differences in spatial memory (e.g., Williams et al., 1990). In animals, male rodents receiving anti-androgens during an embryonic critical period and then orchiectomized (testes removed) after birth showed decrements in water maze performance compared with intact, untreated males in adulthood. Conversely, masculinization of females via androgen administration during the same critical period led to improved spatial learning, such that they were similar to intact males and better than intact females (Isgor and Sengelaub, 1998). Similar to the effects of anti-androgen administration on spatial performance in male rodents, men undergoing a sex-change operation and receiving high doses of cross-sex hormones combined with androgen deprivation performed worse on a mental rotation task (Van Goozen et al., 1995). In contrast, female-to-male transsexuals improved on the mental rotation task after cross-sex-hormone treatment. Overall, it appears that androgens are associated with better performance on spatial tasks measuring the ability to “orient oneself in relation to objects or places, in view or conceptualized across distances…” (Eals and Silverman, 1994, pg.96), such as locating target shapes within a larger pattern, and mental rotation/manipulation (Christiansen and Knussmann, 1987; Janowsky et al., 1994). In contrast to the beneficial effects of androgens on spatial cognition, high estradiol levels during the menstrual cycle have been associated with worse performance on these types of tasks in females (Hampson, 1990).

Thus, when looking at the spatial tasks in which males outperform females and vice versa, one can see that the spatial abilities being measured differ, with males performing better on tasks that require orienting oneself in space or mentally manipulating objects in space and women performing better on tasks requiring one to recall the location of objects in space.

2.3.2. Gist and detail in spatial ability

There appear to be some parallels between the sex differences seen in which features of emotional scenes are recalled and which features of spatial information are recalled. In recalling emotional scenes, males favor gist and females details relatively more. Similar sex differences are seen in the spatial domain. Men tend to focus on the gist of where they or objects are in space, allowing them to more flexibly manipulate themselves or objects within that space. Women, on the other hand, tend to recall the details of the space they occupy, allowing them to better remember objects in an array.

Similar differences are also seen in how men and women navigate in space and provide directions. Studies show that men do not necessarily outperform women on these tasks, but that men and women use different strategies, with men relying more on Euclidean, or allocentric navigation, and women relying more on landmarks, or egocentric navigation (Cherney et al., 2008; Lawton, 1994; Saucier et al., 2002). Nevertheless, eye-tracking revealed men and women attend to the same features on a map, suggesting that the sex differences arise from differences in encoding and/or consolidation rather than from differences in attention (MacFadden et al., 2003).

Thus, in both laboratory tasks assessing spatial ability (e.g., mental rotation or object location) and navigation, it seems as though women are encoding and retrieving detail information (e.g., location of objects), allowing them to better identify changes in their local environment, while men are encoding and recalling gist information (e.g., orientation of objects), which allows them to find alternate routes over large areas.

Creating detail- and gist-type distinctions for spatial memories is not new. The multiple trace theory (Moscovitch et al., 2005) posits that some spatial memories are akin to episodic memories, with detailed representations not only of the route but also of the details of the scenes that allow re-experiencing the environment as one mentally walks through it. This level of detail may be useful for re-experiencing the environment but not for navigation. In contrast, other spatial memories are akin to semantic memories, with schematic representations that include only features which are salient cues, which may be more useful for navigation but not for re-experiencing the environment. This would suggest that spatial memories in women tend to be encoded in a more egocentric, episodic fashion, while spatial memories in men tend to be encoded in a more allocentric, semantic fashion.

As with non-spatial episodic vs. semantic memories, evidence suggests that the kind of detailed spatial memory which shares features with episodic memory is hippocampal-dependent, while the kind of spatial memory sharing features with semantic memory is less hippocampal-dependent (Moscovitch et al., 2005). This pattern suggests that the detail associated with female spatial memory performance would be hippocampal-dependent, while the gist associated with male spatial memory performance would not be hippocampal-dependent. However, as we will review in section 3, below, this is not the case. Brain activation in humans during recall of episodic autobiographical memories indicates that men tend to recruit hippocampal circuits, whereas women tend to recruit more prefrontal cortical regions (Piefke et al., 2005; St. Jacques et al., 2011). This pattern of brain activation aligns with other findings showing male animals and humans tend to show greater hippocampal reliance during spatial learning and memory tasks than females, while females tend to rely more on frontal regions (Grön et al., 2000; Roof et al., 1993).

2.4. Global and local processing is the gist and detail of perceptual processing

Sex differences in gist and detail processing also extend to perceptual processing. Perceptual processing, here, refers to the temporal order in which a scene and its individual features are recognized by an individual. In studies examining these processes, the overall scene is the global level of processing, whereas the individual features making up the scene are the local level of processing (Navon, 1977, 1981). This is often tested using the Navon task (Navon, 1977, see Figure 1 for example of hierarchical stimuli), which requires participants “…to respond to an auditorily presented name of a letter while looking at a visual stimulus that consisted of a large character (the global level) made out of small characters (the local level)” (Navon, 1977, pg. 353). Two findings suggest that the global level is typically processed first (Navon, 1977). First, when participants were given no instruction on whether to attend to the global or local level (divided attention), interference in responding to the auditory stimuli occurred only when there was a mismatch between the global level character and the auditory stimulus, not between the local level character and the auditory stimulus (Navon, 1977). Second, when participants were asked to focus on only the global or local features (selected attention paradigm), in the absence of auditory stimuli, participants were unable to identify the local features when asked to focus on the global level, but could identify the global features when asked to focus on the local level (Navon, 1977). Interestingly, these global and local features of a scene can be likened to the gist and detail of an emotional story or spatial paradigm, where the gist represents the global, overall theme/location and detail represents the local, individual non-essential features within the theme/location. If the sex differences in memory for gist and detail information extend to this perceptual domain, men should have a greater global advantage and women a greater local advantage.

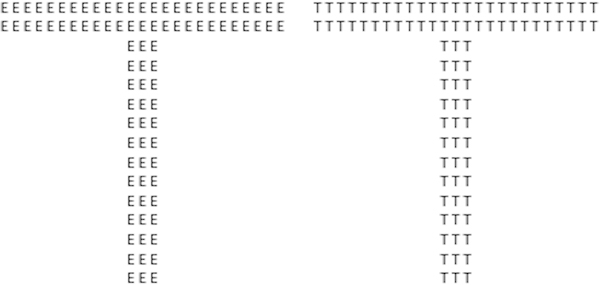

Figure 1.

Example of hierarchical stimuli used for testing global and local perceptual processing. On the left, the large letter ‘T’ is at the global level and the small letter ‘E’s creating the shape of the large ‘T’ are at the local level. On the right, the letter ‘T’ is used at both the global and local level. The global level is processed prior to the local level (Navon, 1977).

2.4.1. Sex differences in global and local processing

Although the literature examining global vs. local processing biases does not always show sex differences, there are some findings indicating a male bias towards global processing versus a female bias towards local processing. In one study reporting sex differences using an adaptation of the Navon task (Kimchi and Palmer, 1982), effects are seen as early as preadolescence, with boys aged 4–12 showing more global selections than girls of the same age (Kramer et al., 1996). In this adaptation, hierarchical stimuli consist of large shapes (global) constructed from smaller shapes (local) and rather than recording reaction time to identify target stimuli at the global or local level, participants choose which two out of three stimuli are similar; choices about match can be made at the local level or global level (Kimchi and Palmer, 1982). This effect in the Kimchi-Palmer task has not been replicated in adults, with men and women making a similar number of global choices (Basso and Lowery, 2004; Scheuringer and Pletzer, 2016). However, when reaction time to selection is examined, sex differences have been reported, with women showing faster reaction times than men for local choices and men showing faster reaction times than women for global choices (Scheuringer and Pletzer, 2016).

In contrast to the Kimchi-Palmer task, sex differences are more consistently observed in the Navon task using both letters and shapes. In one study, participants were asked to respond anytime a particular letter appeared. The letter could appear at either the global or local level. Women responded faster when the target appeared at the local level compared to the global level, whereas men did not differ in their response times between global and local location of the target (Roalf et al., 2006). In another study, while men and women showed a general global advantage in a divided attention paradigm (given no instruction on which level to attend to), such that reaction times were faster for global than local targets, women showed decreased global advantage compared with men during trials when asked to focus on either the global or local level (selected attention paradigm) only during the high-hormone luteal phase, not during lower hormone states (Pletzer et al., 2014). Following this pattern, testosterone was positively correlated with global advantage during the selected attention paradigm in men and women during the low-hormone follicular phase but negatively correlated with the global advantage during the high-hormone luteal phase (Pletzer et al., 2014).

Sex differences in adults in global and local processing have also been reported in a study using numerical stimuli rather than the traditional letter stimuli (Pletzer et al., 2013). In this study, participants were required to compare two two-digit numbers and determine which number was larger. While men and women showed slower reaction times to numbers within the same decade (e.g., 62 vs 66) versus those in different decades (e.g., 62 vs 48), men showed less of a difference in reactions times between the two conditions than women during the low-hormone follicular phase of the menstrual cycles (Pletzer et al., 2013). This pattern suggests that men are likely processing multi-digit numbers as unitary, whereas women may be processing multi-digit numbers as individual items placed together. This interpretation was supported when looking at trials where number pairs were mismatched in whether both digits within a number were larger or smaller than both digits in the other number (e.g., 62 vs. 51 or 62 vs. 57). In these trials, women also showed slower reaction times (Pletzer et al., 2013), suggesting that women allocated attention resources to the second digit of the numbers even though larger or smaller judgements could be made on the first digit alone.

However, as was seen for the Kimchi-Palmer adaptation to the Navon task, sex differences in global vs. local attention have not been consistently reported. One study only found differences when examining response facilitation effects between congruent and incongruent trials (Müller-Oehring et al., 2007). Congruent trials were those where both the global and local level contained the same target letter (e.g., small “T”s forming one large “T”), while incongruent trials were those where one level consisted of one target letter and the other level consisted of the second target letter (e.g., small “E”s forming one large “T”, or vice versa). In this instance, while men showed response facilitation (i.e., faster reaction times on congruent trials) regardless if attention was focused on the global or local level, women only showed response facilitation when attention was focused on the global level and the local level was also a target, but did not show facilitation when attention was focused on the local level and the global level was also a target (Müller-Oehring et al., 2007).

The variability in sex differences have been elsewhere attributed to stimuli selection, with letter stimuli purported to pick up sex differences whereas shape or line stimuli are less likely to pick up such differences (Pletzer and Harris, 2017). Sex differences are also less likely to be observed in divided attention paradigms compared with selective attention paradigms (Pletzer and Harris, 2017). Despite these inconsistencies, there do appear to be some sex differences in global and local processing, with men trending toward more gist or global processing of hierarchical stimuli and women trending toward more detail or local processing of hierarchical stimuli (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sex differences in global and local processing. Pictorial depiction of the trend for men toward more gist or global processing of hierarchical stimuli and women toward more detail or local processing of hierarchical stimuli.

2.5. Overview

We have reviewed three disparate domains, which all appear to share a similar theme in terms of sex differences. In emotional autobiographical and episodic memory, we see that men appear to encode and retrieve more gist-type information, such as limited detail information for daily events or the central theme to a story, while women appear to encode and retrieve more detail-type information, such as more detailed information for daily events or more peripheral information from a story with no bearing on the central theme. We see this phenomenon extend to spatial abilities where men appear to encode more long-distance gist-type information when processing spatial information, which allows them to perform better on tasks requiring they orient themselves or objects in space, while women appear to encode more short-distance detail-type information when processing spatial information, allowing them to perform better on tasks requiring they remember where in space objects are located. Lastly, although less robustly, we see this theme carry through to perceptual processing, where men show instances of greater global advantage, or better identification of central, gist-type information, while women show instances of better identification of local, detail-type information within hierarchical stimuli.

We propose it is not just coincidence that at least three cognitive domains share similar sex differences in allocation of encoding and/or retrieval processes. In the next section, we will review the neural underpinnings and sex differences in these processes which may contribute to the sex differences in behavior.

3. Are sex differences in the brain regions associated with these tasks responsible for sex differences in emotional memory, spatial memory, and perceptual processing?

The sex differences in behavior and memory we have covered so far are associated with sex differences in the brain. We first will cover sex differences in the primary regions associated with emotional memory, spatial behaviors, and perceptual processing, the amygdala, hippocampus, and hemispheric laterality, respectively2. However, as we will note, while sex differences in these regions do reflect sex differences in their associated cognitive domains, they do not address the overall pattern of a bias toward gist information in males and toward detail information in females. As such, a more unifying mechanism which can lead to this kind of widespread differentiation should also be considered.

3.1. Sex differences in the amygdala and emotional stimuli

The amygdala is integral to processing emotional stimuli and memory formation for events with emotional import (Anderson et al., 2003; Cahill et al., 1995; Fox et al., 2001; Phelps, 2004; Roozendaal and Hermans, 2017). Given the sex differences in reactivity and memory for emotional information, it is not surprising that men and women also display differences in amygdalar responses to emotional information as measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET). For instance, using PET, men showed greater right amygdala glucose metabolism while viewing negative video clips compared to neutral video clips, but women showed greater left amygdala glucose metabolism while viewing the negative video clips (Cahill et al., 2001).

These patterns of amygdala activity were also observed using an fMRI paradigm. In one study, participants were scanned while viewing negative and neutral images (Cahill et al., 2004). Two weeks later, participants returned and completed a recognition test of the photos they had seen during the prior session intermixed with new emotional and neutral images. Amygdala activation during the first session, when images were first viewed, was then examined for those images correctly recognized versus those not correctly recognized. Men showed significantly greater right amygdala activation and women showed significantly greater left amygdala activation in response to correctly recognized negative images (Cahill et al., 2004). Additionally, men tended to show greater activation of right hemisphere brain regions, including the anterior hippocampus, globus pallidus, frontal cortex, and bilateral parietal, whereas women showed more left hemisphere brain activation, including posterior cingulate, middle temporal gyrus, and inferior parietal cortex. Others replicated this sex difference in amygdala laterality in brain responses during viewing of negative images correctly recognized three weeks later, although only women showed an overall trend to exhibit more activation in left hemisphere brain regions, with the significant laterality effect in men limited to only the amygdala (Canli et al., 2002).

Others have failed to find this same task-based effect of sex on laterality, but still report sex differences in amygdala and brain activation during the viewing of emotional stimuli (Killgore and Yurgelun-Todd, 2001). A meta-analysis also reported a lack of consistency in the laterality differences, but still found sex differences in brain activation patterns to emotional stimuli (Stevens and Hamann, 2012). This meta-analysis revealed that the only significant amygdala activation men had over women was in the left amygdala when viewing positive emotional stimuli, but not negative stimuli. Other brain regions differed between men and women, with more sex differences driven by women in studies using negative stimuli, such as the left hippocampus, suggesting women may be more likely to encode negative images. Other regions also suggest that women may internalize and ruminate over negative stimuli more than men, with women showing greater activation in regions such as anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex, which show increased activity corresponding to self-reports of anger (Denson et al., 2009)and rumination (Denson et al., 2009; Ray et al., 2005). Meanwhile, men exhibited greater activation in the right anterior insula and bilateral inferior frontal gyrus in response to both negative and positive stimuli. Men also showed greater activation of the entorhinal cortex in response to positive stimuli (Stevens and Hamann, 2012), suggesting that while women show activation suggesting increased encoding of negative stimuli, men show activation suggesting increased encoding of positive stimuli. This positivity bias in memory may help explain why men show greater risk-taking behaviors than women (among other reasons; see e.g., Mather and Lighthall, 2012).

3.2. Sex differences in the hippocampus and spatial memory

There is little dispute that the hippocampus supports spatial memory in animals (Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2004; Morris et al., 1982; O’Keefe and Nadel, 1978, 1979; Scoville and Milner, 1957) and in humans (Abrahams et al., 1999; Burgess et al., 2002; Maguire et al., 1998; Maguire et al., 1999; Maguire et al., 1996; Spiers et al., 2001; Vargha-Khadem et al., 1997). In particular, much work in animals implicates hippocampal processes in behaviors dependent on spatial location, such as food storage and homing, based on evidence that species that practice these behaviors have much larger hippocampal size compared to species that do not share these behaviors (Sherry et al., 1992).

Similar to the effects of stress and sex hormone-stress interactions on spatial task performance, these factors can also modulate hippocampal morphology (Arbel et al., 1994; Conrad et al., 1996; Magariños et al., 1996; McEwen et al., 1968; Olton et al., 1978; Sousa et al., 2000; Vyas et al., 2002) and function during these tasks (Bowman et al., 2003; Bowman et al., 2001; Conrad et al., 1996; Conrad et al., 1999; Galea et al., 1997; McEwen, 2000; Park et al., 2001). Here, we will focus on the hippocampal involvement in spatial memory and abilities under normal, non-stressful conditions.

The hippocampus has a high density of sex hormone receptors (Brailoiu et al., 2007; Simerly et al., 1990), allowing gonadal steroids to modulate hippocampal structure and function (Foy et al., 1984; Gould et al., 1990; Roof and Havens, 1992; Woolley et al., 1990). Thus, unsurprisingly, a number of animal studies have noted various sex differences in the hippocampal formation, including larger volume in males than females (Jacobs et al., 1990; Pfaff, 1966). The pattern of larger hippocampal volume in males is less established in human neuroimaging studies. Although a recent meta-analysis reported that relative to cranial size men have larger hippocampal volume (Ruigrok et al., 2014), others, including another recent meta-analysis, reported that men and women have comparable hippocampal size (Gur et al., 2002; Tan et al., 2016), others that women have larger hippocampal volumes (for review, Cahill, 2006), while still others noted that the difference in size may shift across the lifespan with girls having larger hippocampi than boys, but with women experiencing greater hippocampal decline than men (for review, Cosgrove et al., 2007).

Despite the inconsistent results in humans for hippocampal volume, other work in rodents report larger hippocampal subfields in males which may relate to differences in spatial learning. In addition to having faster completion times during a maze task, male rats showed CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cell field volumes approximately 20% larger than females and pyramidal neuron soma sizes 14–18% larger than females (Isgor and Sengelaub, 1998). This pattern of larger cell fields and better performance in males suggests that CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cells are highly involved in spatial tasks associated with better performance in males over females.

Perhaps more influential than structural differences on sex differences in behavior, are the observations suggesting there are sex differences in the recruitment of other brain regions during spatial tasks. Lesions of the entorhinal cortex, located in the parahippocampal gyrus and sharing connections with CA1 and CA3, cause greater impairment in males than in females on the Morris water maze (Roof et al., 1993). By contrast, female rats show greater deficits on most measures of a radial maze and Morris water maze tasks when they received frontal cortex lesions (Kolb and Cioe, 1996). In humans, a similar reliance on the hippocampus in men and frontal cortex regions in women was observed using a maze task. It was reported that in addition to finding their way out of the maze faster, men showed greater activation of the left hippocampus, right parahippocampal gyrus, and the left posterior cingulate, whereas women consistently recruited right parietal and right prefrontal cortex during the maze task (Grön et al., 2000).

That women tend to rely on and recruit more frontal regions during spatial tasks aligns with the above-discussed behavioral studies showing women navigate using landmarks, while men navigate using more allocentric strategies. In strategies using landmarks, working memory processes should come online in order to maintain the landmarks in accessible short-term memory. Working memory relies on frontal regions more than on hippocampal regions (Curtis and D’Esposito, 2003), which may account for why females show frontal recruitment during the spatial tasks and males do not (Grön et al., 2000).

3.3. Sex differences in brain laterality and perceptual processing

Sex differences in the relationship between brain activation and global/local processing also have been observed (Müller-Oehring et al., 2007; Pletzer et al., 2013; Roalf et al., 2006), although as seen with the global/local behavioral findings, patterns of brain activation differences are less robust and consistent than such differences seen for emotional memory and spatial ability.

Earlier, we discussed findings showing women responded faster when a target letter appeared at the local versus global level, while men did not differ in their response times (Roalf et al., 2006). Brain event related potential (ERP) recordings from this same study revealed some differences in ERP responses for those components related to early visual processing (P100 and N150) and cognitive processing (P300). In contrast to bilateral P100 responses in the occipital lobes when women were viewing global targets, women only showed P100 responses in the right occipital hemisphere when viewing local targets (Roalf et al., 2006). Meanwhile, men showed larger amplitude ERPs for the N150 component when the target letter was in a global location (Roalf et al., 2006). The ERP for the cognitive P300 component followed the behavioral responses, with men showing no difference between global and local location of the target letter, whereas women showed higher amplitude P300 components when the target letter was locally located versus globally located (Roalf et al., 2006).

Brain activation measured via fMRI also revealed sex differences. In the task where participants made judgements about which number in a pair of numbers was larger, women showed greater bilateral activation throughout, with greater recruitment of fronto-parietal regions during within-decade pairs and posterior superior parietal lobule during different-decade pairs than men during the high-hormone luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (Pletzer et al., 2013).

Sex differences in lateralization have also been observed using letter and shape stimuli (Pletzer and Harris, 2017). Performance of the Navon task was generally associated with bilateral increased activation in the parietal and occipital lobes and decreased activation in the inferior parietal gyri, precuneus, anterior cingulate cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex. However, brain activation in the occipital lobes was largely right lateralized for global targets and left lateralized for local targets (Pletzer and Harris, 2017). Lateralization scores, which indicate greater activation in one hemisphere over the other, showed that women displayed greater left lateralization in the occipital lobe than men for local targets particularly during selected attention blocks. Such an effect was not observed in men unless inter-hemispheric connectivity was taken into account. In this regard, greater negative parieto-parietal connectivity was associated with greater left lateralization in the parietal lobe and greater global advantage. This pattern suggests that men may require more energetic resources to process local details than women, while women may not require a complimentary increase in energetic resources to process global items.

3.4. Overview

In the above section, we reviewed evidence that sex differences in behavior show corresponding differences in the brain, although differences for emotional memory and spatial ability are more consistent than for perceptual processing. Given the importance of these brain structures for the successful execution of their relative cognitive tasks, it is likely that sex differences in these regions contribute to sex differences in behavior and cognition. One remaining question is whether these sex differences developed independently from one another (e.g., sex differences in the amygdala developed with no relation or consequence to sex differences in hippocampus or hemispheric activation, all of which, coincidentally, led to similar sex differences in behavioral/cognitive outcomes) or whether some additional mechanism led to a more favorable gist versus detail strategy in males and females leading to similar sex differences to take shape in the brain, behavior, and cognition. Concluding that the similarity of sex differences across these three domains all developed as independent systems, with no common guiding mechanism, suggests that brain development occurs in an unorganized, stochastic fashion, which is not the case (Schottdorf et al., 2015; Sporns et al., 2004). As a result, it seems more likely that more specific pressures or mechanisms led to common sex differences across these domains and related brain regions. Below we review possible mechanisms for why and how these differences developed.

4. Are there any general brain mechanisms that could help account for the similar sex differences seen across multiple domains?

There are multiple possibilities for why this gist and detail parallel is observed across multiple domains. Each of which can account for the parallel to some extent, but generally fall short when the questions of “why and “how” are posed. Ideally, a mechanism able to explain this parallel would address both why the difference occurs and how the difference occurs. Below we review three possible explanations, and their individual strengths and weaknesses.

4.1. Sex differences in global and local perceptual processing as a mechanism for sex differences in gist and detail encoding and retrieval in emotional and spatial memory

It has been proposed that sex differences in visuospatial processing of global and local features drive sex differences in other aspects of cognition, including spatial abilities, emotional memory, and verbal abilities (Pletzer, 2014; Pletzer et al., 2013). In one such account, men and women attend to different aspects of presented scenes, leading to sex differences in recall or navigation performance (Pletzer, 2014). However, this account ignores work showing that men and women scan, fixate, and attend to emotional scenes (Nielsen et al., 2013, 2014; Nielsen et al., 2011) and maps (MacFadden et al., 2003) in a similar fashion. Nonetheless, one study examining the relationship between global-to-local processing and other cognitive domains (spatial navigation and verbal fluency), did find that global advantage in the Navon task during selected attention blocks was related to better performance on a spatial task requiring allocentric navigation, however, the effect was stronger in women than men (Pletzer et al., 2017).

Some studies have examined how manipulating the spatial nature of hierarchical stimuli (line orientation vs. shape judgement) might modulate sex differences in global and local processing. In one study (Kimchi et al., 2009), men and women both showed global advantage (i.e., faster reaction times to global targets than local targets), and did not differ in local processing reaction times. However, sex differences did emerge when stimulus type was taken into consideration. For instance, women were sensitive to differences in line orientation between global and local levels, such that they showed global interference of classification of local line orientation when the global line orientation differed. Men, on the other hand, did not show global interference resulting from differences in line orientation (Kimchi et al., 2009). Conversely, women more accurately classified shape stimuli as either open or closed patterns than men (Kimchi et al., 2009). This pattern follows sex differences in spatial ability, suggesting that men outperform women on tasks centered on orienting oneself or objects in space and women outperform men on tasks centered on object recognition.

While sex differences in global versus local processing may contribute to sex differences in gist versus detail encoding and retrieval in spatial tasks, it does not account for why scenes and spaces are encoded and later retrieved differentially between males and females. Evolution and natural selection suggest that these differences would have been selected to increase survival. Thus, while sex differences in visuospatial processing may contribute to sex differences in encoding and retrieval across domains, that explanation still does not address why males and females would develop sex differences in and across these domains.

One proposal, aimed at explaining how sex differences occur across domains, suggests that sex differences in brain laterality related to visuospatial processing drive sex differences in and across different cognitive functions (Pletzer, 2014). Problematically, laterality differences have been observed in emotional memory and global/local processing, but not in an entirely coherent manner across the two domains. While sex differences in emotional memory show greater left amygdala and hemisphere activation in women and right amygdala and hemisphere activation in men (Cahill et al., 2001; Cahill et al., 2004; Canli et al., 2002; Stevens and Hamann, 2012), the findings for sex differences in left versus right hemisphere activation for global versus local stimuli is less consistent (Pletzer and Harris, 2017; Pletzer et al., 2013; Roalf et al., 2006). This is problematic given the striking conceptual parallel between the gist and detail differences in emotional memory and the global and local differences in visuospatial processing (see Section 3 for discussion). Furthermore, as discussed in Section 3, sex differences in laterality of the amygdala for emotional memory and more generally between hemispheres for perceptual processing do not account for why and how these differences came to exist. Importantly, this account also does not adequately explain sex differences in the hippocampus and elsewhere in the brain as they pertain to spatial abilities where laterality does not play a robust or consistent role. Thus, in order to make progress toward what forms these sex differences take in the brain and behavior, we could benefit from a more cohesive and efficient mechanism to account for sex differences across cognitive domains and the brain.

4.2. Differential evolutionary pressures favored different encoding and retrieval strategies between males and females

One possible explanation for “why” sex differences exist in such a uniform manner across cognitive domains are theories of differing evolutionary pressures for males and females. Evolutionary pressures associated with spatial navigation may account for biases toward encoding and retrieving gist versus detail information in males and females. When looking at the spatial tasks in which males outperform females and vice versa, one can see that the spatial abilities being measured differ, with males performing better on tasks requiring orienting oneself in space or mentally manipulating objects in space (Astur et al., 1998; Beatty, 1984; Cherney et al., 2008; Dawson et al., 1975; Galea and Kimura, 1993; Grön et al., 2000; Isgor and Sengelaub, 1998; Linn and Petersen, 1985; MacFadden et al., 2003; Postma et al., 2004; Saucier et al., 2002) and females performing better on tasks requiring the recall of object locations in space (Cherney et al., 2008; Eals and Silverman, 1994; Galea and Kimura, 1993; James and Kimura, 1997; MacFadden et al., 2003; McBurney et al., 1997; Saucier et al., 2002; Silverman and Eals, 1992). These features may also relate to findings that men tend use allocentric navigation strategies while women tend to use egocentric navigation strategies (Cherney et al., 2008; Lawton, 1994; Saucier et al., 2002).

The Hunter-Gatherer Theory (Eals and Silverman, 1994) posits that the pattern of sex differences observed in spatial ability arises from different evolutionary pressures facing men and women, where early man needed to travel over large areas to hunt, and women were more likely to live and forage in one region (Silverman et al., 2007; Silverman and Eals, 1992). Thus, the types of tasks men excel in are abilities allowing for a more allocentric approach to encoding spatial information and navigation (Dabbs et al., 1998; Silverman and Eals, 1992). For instance, when hunting prey males do not know where or how far from home the hunt will come to end. If males encoded and retrieved landmark information they would need to retrace their steps to return home. However, that may not be the most direct route home, making egocentric navigation (e.g., using landmarks and “right”/”left” direction) a less adaptive strategy for males than the allocentric strategy that males tend to utilize. By contrast, the types of tasks women excel in would, for example, allow women to better recall the locations of items fixed in place, such as a particular food source and better monitor their immediate surroundings (Dabbs et al., 1998; Silverman and Eals, 1992).

Evolution is aimed at balancing optimal efficiency of each system within an organism (Noor and Milo, 2012; Schuetz et al., 2012; Shoval et al., 2012; Yun et al., 2006). Hunting and foraging for food was essential for survival, making evolutionary pressures for spatial strategies of utmost importance. Given that systems would be geared toward efficiency, these encoding and retrieval processes should then be utilized for other behavioral and cognitive domains. These pressures offer an account of “why” sex differences occur, but still do not address “how” they are occurring.

We propose that the “how” mechanism results from differences in the brain. However, following the concept of efficiency within and across systems, it seems unlikely that the aforementioned sex differences in the brain regions related to these behavioral and cognitive processes developed independent of one another in a stochastic fashion. Rather, it is possible that another brain region, able to effect change throughout the brain, modulates these processes differently in males and females leading to different patterns of brain activation and different patterns of performance.

One brain region that may be able to exert the level of widespread neural modulation required to affect each of these domains is the locus coeruleus (LC). The LC regulates vigilance and re-orienting attention to all manner of salient stimuli, regardless of valence. Through its broad and diffuse release of norepinephrine (NE) across most of the brain (Abercrombie et al., 1988; Aston-Jones, 2004; Morrison et al., 1978), the LC is ideally positioned to modulate activity in various regions implicated in attention and memory (for reviews see, Sara, 2009; Sara and Bouret, 2012), and importantly, to exert different effects throughout the brain via sex differences in its own structure and function. Furthermore, local cortical NE-glutamate interactions spark “hot spots” of high excitation that promote processing of whatever is most salient at that moment (Mather et al., 2016).

4.3. LC-NE system as a potential mechanism for facilitating these differential strategies

The LC is a small pontine nucleus whose role is identifying and orienting attention to salient stimuli, which makes the LC an ideal candidate for mediating sex differences between gist and detail memory. It is possible that while men and women are attending to the same scene, LC signaling may inform a female system that detail-level stimuli are salient and should be attended to. This would be adaptive based on the aforementioned evolutionary pressures hypothesized to affect women more than men. In contrast, those pressures hypothesized to affect men more than women may make the male LC less likely to identify detail features as salient and worth encoding for later retrieval. The question then becomes, how the LC effects the neural milieu exerting such sex differences.

4.3.1. Sex differences in the locus coeruleus

Sex differences in the LC-NE system, particularly with respect to a higher prevalence of stress- and anxiety-related disorders in women, have been skillfully and extensively reviewed elsewhere (Bangasser et al., 2017; Bangasser and Valentino, 2012, 2015; Bangasser et al., 2016). Here, we briefly review evidence showing that male and female LC differ on various indices, including size/volume, morphology, and function. Given the small size and location of this nucleus, much of the structural and activational work is conducted in animals, unless otherwise indicated.

Sex differences in this midbrain pontine structure are documented to begin during adolescence, with males and females showing differences in LC volume and neuron number during puberty. Continued LC neurogenesis in females through puberty and discontinued neurogenesis in males at the onset of puberty drive these sex differences (Pinos et al., 2001). Evidence suggests that the onset of estradiol cyclicity in females is the catalyst for differences appearing at the onset of puberty. Disruption of estradiol production and concentration, even after puberty, has been shown to abolish the formation of larger LC volume and higher neuron count in females (De Blas et al., 1990). Further evidence for the driving role of estradiol leading to larger LC volume and neuron number in females is the androgenizing effect of testosterone propionate when administered to females on postnatal day 1. These females no longer differed from males and had smaller LC volume and neuron count than normal intact females, however, orchiectomy of males had no effect on LC volume or neuron number (Guillamón et al., 1988). Showing that testosterone resulted in smaller LC volume and lower neuron count in females, while loss of testosterone in males did not lead to changes in LC volume or neuron number, suggests that the observed effect in females was not a result of testosterone action on the female LC but rather disruption of the normal estradiol-induced organization and modulation of LC development resulting from the testosterone administration in early development.

Others have shown that larger LC volume in females compared with males is driven by sex differences in the overall volume and number of NE neurons in the LC, particularly in the intermediate anterior regions of the LC in females (Luque et al., 1992). Interestingly, however, some evidence suggests that males do have a larger LC volume depending on the LC subregion of interest (Babstock et al., 1997). This study found that adult male Sprague-Dawley rats exhibited larger dorsal LC volume, a difference driven by a subregion of the dorsal LC that heavily innervates the hippocampus (Babstock et al., 1997), which may have important implications for spatial abilities in males.

Perhaps more importantly from a functional standpoint, adult females are reported to exhibit larger density of the dendritic field throughout the LC and peri-LC regions, including the core, ventromedial LC, and dorsolateral LC, likely resulting from females showing greater number of dendritic nodes and ends, dendritic length, and higher branch order (Bangasser et al., 2011). The length of longest dendritic tree was also longer in females than in males. As would be expected with a greater number of dendrites, females also appear to have more synapses based on higher levels of synaptophysin in the core and dorsolateral LC (Bangasser et al., 2011).

Another set of important functional findings show that the female LC is more responsive to stressful stimuli. For instance, females show a greater increase in tonic LC neuronal firing rates in response to hypotensive stress than males (Curtis et al., 2006). This larger neuronal response to the same stressor was driven by greater sensitivity of LC neurons to corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in females, such that a lower dose of CRF resulted in a greater increase of tonic LC firing rates in females than in males (Curtis et al., 2006). The sex difference in CRF sensitivity appears at the level of receptor signaling. The CRF receptor involved in this process is a G-protein coupled receptor (Grammatopoulos et al., 2001; Hillhouse and Grammatopoulos, 2006), which increases LC tonic firing rates via activation of a cAMP-dependent intracellular signaling cascade (Jedema and Grace, 2004). In contrast with unstressed males, the larger LC neuronal response to a low dose of CRF in females was found to be completely mediated by this cAMP-dependent cascade. However, when males were first exposed to a stressor, they exhibited a sensitized LC response, such that neurons responded to a lower dose of CRF. This sensitization of LC neurons in males was completely cAMP-dependent (Bangasser et al., 2010). This pattern suggests that females experience a near maximal response in the LC to stressors that do not affect the male LC system. This increased sensitivity may have important implications for the LC even in the absence of stress. Recall that the LC plays an integral role in identifying and orienting to salient stimuli (Sara, 2009; Sara and Bouret, 2012). Thus, if the female system is more sensitive to stressors, it might be the case that the female system also identifies different stimuli as salient, which would result in encoding of different features of the same scene than males.

4.3.2. Sex differences in the locus coeruleus and norepinephrine drive sex differences in emotional memory

The LC shares bidirectional projections with the amygdala (Buffalari and Grace, 2007; Canteras et al., 1995; Cedarbaum and Aghajanian, 1978; Jones and Moore, 1977; Segal et al., 1973; Wallace et al., 1992), and NE activation of the amygdala is necessary for successful encoding and consolidation of emotional memory (Hermans et al., 2014; Roozendaal and Hermans, 2017). For instance, in humans NE facilitates memory enhancement for the middle portion of the negative version of the three-phase story (Cahill et al., 1994), and NE must act centrally, not peripherally, to yield such memory enhancement effects (van Stegeren et al., 1998). Given the sex differences that exist in the NE system and in emotional memory, it should not be surprising that there are sex differences in how NE influences emotional memory.

Following up on their work showing propranolol, a β-adrenoreceptor blocker, abolished enhancement for the middle phase of the negative version of the three-phase story (Cahill et al., 1994; van Stegeren et al., 1998), Cahill and van Stegeren (2003) found that the effects of propranolol on gist and detail memory differed by sex. As reviewed previously, men typically recall the gist, while women recall the details (depending on menstrual cycle phase and contraceptive status) of a scene. In line with the observed sex difference under control conditions, administration of propranolol prior to encoding diminished emotion-related enhancement of gist memory in men and detail memory in women (Cahill and van Stegeren, 2003). This pattern suggests that LC-NE modulation of the amygdala not only plays a role in encoding emotional memories, but also plays a role in the sex differences observed for encoding of detail versus gist information in women and men, respectively.

4.3.3. Sex differences in the locus coeruleus and dopamine may drive sex differences in spatial memory

The LC and hippocampus are also highly interconnected. The LC innervates the hippocampus (Jones and Moore, 1977; Loughlin et al., 1986a; Loughlin et al., 1986b; Pasquier and Reinoso-Suarez, 1978; Segal and Landis, 1974; Segal et al., 1973) and receives afferents from the subiculum (Swanson and Cowan, 1977). In addition to sharing efferents and afferents, the LC-NE system contributes to spatial abilities (Lemon et al., 2009; Lemon and Manahan-Vaughan, 2012; Nakao et al., 2002) via modulation of long-term plasticity within the hippocampus related to spatial memory formation (Hansen and Manahan-Vaughan, 2015a, b). Recent work suggests that the LC specifically modulates spatial learning and memory (Kempadoo et al., 2016), via dopaminergic innervation of the hippocampus (Kempadoo et al., 2016; Kentros et al., 2004). While not the primary source of neural dopamine (DA), the LC is also involved in DA release throughout the brain (Devoto and Flore, 2006; Devoto et al., 2005; Grenhoff et al., 1993; Kempadoo et al., 2016; Lategan et al., 1990; Lemon and Manahan-Vaughan, 2006), an effect that appears to be mediated by NE action.

Recent work demonstrated that LC modulates spatial memory via DA action (Kempadoo et al., 2016). This study found that while dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons send projections to the CA1, of the two catecholamines, increasing dopaminergic tone to the dorsal hippocampus by stimulating LC dopamine release resulted in enhanced spatial performance across a battery of spatial tests, including a spatial object recognition test, the Barnes maze, and a conditioned place preference test, in animals that otherwise would not have learned. This effect occurred primarily through activation of the dopamine D1/D5 receptor complex (Kempadoo et al., 2016). Dopamine D1/D5 receptors are featured prominently on pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus and other cortical regions (Bergson et al., 1995), where they are important for long-term plasticity in the hippocampus (Hansen and Manahan-Vaughan, 2014) and for spatial learning (Granado et al., 2008).

While little work has examined sex differences in LC projections to, or LC modulation of activity in, the hippocampus, extant data suggest that men receive greater LC input to the hippocampus than women. In animals, the dorsal region of the LC, which heavily innervates the hippocampus (Mason and Fibiger, 1979), is larger in males than females (Babstock et al., 1997). In humans, one resting-state fMRI study also suggests that fluctuations in LC activity are more tightly coupled with activity in the hippocampus and other medial temporal lobe regions in males than females (Zhang et al., 2016). This preferential LC modulation of the hippocampus in males may at least partially explain why males exhibit better performance on spatial tasks requiring orienting oneself or objects in space (Zhang et al., 2016).

Unlike investigation of sex differences in LC-hippocampus interactions, there is ample evidence of sex differences in the DA system, although much of this research is confined to the domain of reward learning. Nonetheless, much of this research shows that males show overproduction of DA receptors in the striatum until puberty and retain greater D1 receptor density in the nucleus accumbens (Andersen et al., 1997) and greater DA release in the striatum in response to amphetamine administration (Munro et al., 2006). On the other hand, females show greater DA clearance efficiency (Mozley et al., 2001), suggesting the male system maintains higher levels of DA. Given the importance of DA and the D1/D5 receptor complex in spatial learning and memory, this pattern of greater DA may speak to the aforementioned greater reliance on the hippocampus for spatial tasks in males compared to females who also recruit frontal regions during spatial tasks (Grön et al., 2000; Kolb and Cioe, 1996; Roof et al., 1993), as discussed in section 3.

4.3.4. Can sex differences in the locus coeruleus and arousal speak to sex differences in global and local processing

Recall that while there is a general effect of global precedence in perceptual processing, sex differences in global and local processing suggest that men show a tendency to perform better on global processing and women on local processing (Kimchi et al., 2009; Kramer et al., 1996; Müller-Oehring et al.; Pletzer and Harris, 2017; Pletzer et al., 2013; Pletzer et al., 2014; Roalf et al., 2006; Scheuringer and Pletzer, 2016). Given the role of the LC/NE system to identify salient stimuli and reorient attention to those salient stimuli (for reviews see, Sara, 2009; Sara and Bouret, 2012), it would be expected that arousal would amplify this pattern of differences in men and women. However, limited work has examined the effects of arousal on global and local perceptual processing. This limited work in humans has examined how manipulating arousal levels via presentation of a tone might affect performance on these tasks, but do not account for sex (Weinbach and Henik, 2011, 2014). In these studies, flanker tasks were modified to mimic Navon stimuli3 and auditory tones were played prior to congruent or incongruent trials. The measure of performance on these tasks was the “congruency effect” (mean reaction time for incongruent trials minus mean reaction time for congruent trials). In a version of the study where the salience of the local and global interfering information was manipulated, arousal increased attentional biases to whichever aspect of the stimuli was most salient in that context (Weinbach and Henik, 2014). Thus, these findings suggest that if there are sex differences in whether global vs. local stimuli are more salient, increased LC activation due to arousal should increase those sex differences.

4.4. Overview

As seen in sections 4.3.2 and 4.3.3, although structural differences in LC have been reported between males and females, LC structure alone cannot account for why women appear to encode more detail information and men appear to encode more gist information. However, given the known role of NE in re-orienting attention and in regulating vigilance (for reviews see, Sara, 2009; Sara and Bouret, 2012), LC modulation of the NE system and the sex differences indicating the female LC-NE system is more responsive to detail items within a scene or environment may account for this difference. Recall that the female LC is more sensitive to stressors than the male LC (Bangasser et al., 2010; Curtis et al., 2006). This increased sensitivity has often been discussed in its relation to stress- and anxiety-related psychiatric disorders (Bangasser et al., 2017; Bangasser and Valentino, 2012, 2015). However, this increased sensitivity may not be limited to events commonly considered stressors. In particular, evolutionary pressures resulting in differential encoding of detail and gist information between females and males could have capitalized on the widespread influence of the LC throughout the brain to instantiate such differences in other perceptual, cognitive, and neural domains. In doing so, the LC may promote different thresholds in females and males of determining that features of a scene are salient or behaviorally relevant, leading to a preferential encoding of details or local information in females and a preferential encoding of gist or global information in males.

5. Future directions and limitations

Importantly, this is just one possible account for how similarities in sex differences are observed across these three domains and there is still a great deal of research that must be done to test the veracity of this theoretical account. Behaviorally, these effects appear to be stable in emotional memory, but less so in spatial ability and perceptual processing. For instance, experiments linking gist versus detail memory and spatial ability, in particular preferring allocentric or egocentric navigation strategies, remain to be conducted. There is also a need to further explore whether and how increased arousal or direct norepinephrine manipulation affects performance on global-to-local processing tasks. The clearest experimental design to address this issue would involve manipulating LC activation independently from the stimuli used to examine attentional biases toward detail and gist information (for examples of this approach of independently manipulating LC activation levels and stimuli salience see, Clewett et al., 2018; Lee et al., in press)

Another challenge is to determine whether there are sex differences in which aspects of stimuli or scenes the LC tends to amplify processing of during baseline states (i.e., not under states of stress or arousal). Molecular and cellular studies examining neuronal LC response to stimuli typically focus on LC response to stressors, which lead to robust neuronal and neuromodulatory responses, however, our proposed model does not directly benefit from such paradigms. Our model proposes that under normal conditions the LC is differentially identifying whether detail-level items within a global scene are salient and worth encoding in males and females. Testing this would require electrophysiological studies which can measure how LC neurons are responding to different individual stimuli within a scene or environment. A similar model could be tested in humans using the constantly improving technology and imaging sequences for fMRI. LC responses could then be related to performance on memory tasks for global vs. local stimuli within a scene or environment.

A final caveat is the proposed influence of evolutionary pressures on the development of these parallel sex differences across domains. Evolutionary theories are subject to criticism, in particular, the concept of spandrels (Gould and Lewontin, 1979) which discusses how theories centered on evolutionary psychology are in danger of ignoring alternative explanations. In this regard, evolutionary foundation for modern behaviors are at risk of missing alternative causes for said behaviors. As such, it is important to note that evolutionary pressures are not the only possible driving force for shaping and selecting the observed sex differences. One possibility for testing the potential influence of these evolutionary pressures would be to begin incorporating tasks which can decipher detail versus gist memory in anthropological studies focused on current-day hunter-gatherer societies. Alternatively, or additionally, pre-existing data from such hunter-gatherer studies (e.g., Reyes-García et al., 2016) might be reexamined to determine whether some tasks within the datasets may be able to speak to detail versus gist memory and whether performance on those tasks differ by sex.

6. Conclusions

Men and women differ on a range of indices related to perceptual processing, emotional memory, and spatial ability. In these tasks, women tend to show greater encoding of detail information, leading to better performance on recall tasks for peripheral information in an emotional scene and landmarks in a route. Men tend to show greater encoding of gist information, leading to better performance on recall tasks for central information in an emotional scene and allocentric navigation. In a related domain, men and women also show differences in perceptual processing of hierarchical stimuli, with men performing better for global targets and women performing better for local targets. Such differences in perceptual processing seem attractive for explaining sex differences in encoding and retrieval for emotional memory and spatial ability, however they do not account for why and how these low-level sex differences in perception occur. The failure of perceptual processing to account for sex differences suggests that the sex differences observed in perceptual processing are a byproduct of another effect, just as seems likely for emotional memory and spatial ability.

Differing evolutionary pressures and LC innervation throughout the brain may help explain why and how these sex differences occur. Specifically, the greater sensitivity of the female LC-NE system may lead women to activate the LC-NE system in response to stimuli and goals that do not lead to increased activation in males. This non-stress level activation of the LC-NE system may lead to a greater level of vigilance in women when interacting with such stimuli and enhance encoding of detail information.

7. Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. David Clewett for reviewing an initial draft of this manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging awarded to MM (grant number R01AG025340).

Footnotes

The three-phase story is a slideshow of images with accompanying narrative (adapted from, Heuer and Reisberg, 1990). There is a neutral and a negative version, each consisting of a beginning, middle, and end. The middle phase differs between the neutral and negative version. The neutral version explains the middle set of slides as an emergency drill viewed by a mother and son. The negative version explains the same set slides as the son being seriously injured. The middle phase of the emotional version of the story is typically better recalled than the same phase of the neutral version (Cahill et al., 1994).

It is important to note that the hippocampus also is involved in emotional memory processes, such that amygdala activation modulates hippocampal function when forming these emotional memories. The amygdala aids in the formation of episodic memories containing emotional components, such that activation of the amygdala signals the hippocampus to maintain that information for future use (Phelps, 2004). The relationship between structures also is bidirectional, highlighting that episodic memories for information, in other words, for things that have not happened, to also lead to increased amygdala activation. For example, once one hears the phrase “leaves of three, leave them be” they may show an amygdala response to “leaves of three” similar to the response exhibited by someone who has experienced the negative effects of coming in contact with such leaves.

The arrow-flanker task requires participants to indicate the direction of a central arrow in a line of arrows. The arrows can either be congruent (→ → → → →) or incongruent (→ → ← → →). In the modified version of the task used in the reviewed studies (Weinbach, 2011, 2014), the arrows were arranged similar to Navon task stimuli, where one large arrow was made out of smaller arrows. In this formation, congruent trials were where the large, global, arrow and smaller, local, arrows were facing the same direction, while incongruent trials were where the large, global, arrow was facing one direction and the smaller, local, arrows were facing the opposite direction.

References

- Abercrombie E, Keller R, Zigmond M, 1988. Characterization of hippocampal norepinephrine release as measured by microdialysis perfusion: pharmacological and behavioral studies. Neuroscience 27, 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams S, Morris R, Polkey C, Jarosz J, Cox T, Graves M, Pickering A, 1999. Hippocampal involvement in spatial and working memory: a structural MRI analysis of patients with unilateral mesial temporal lobe sclerosis. Brain and cognition 41, 39–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Rutstein M, Benzo JM, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH, 1997. Sex differences in dopamine receptor overproduction and elimination. NeuroReport 8, 1495–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AK, Christoff K, Panitz D, De Rosa E, Gabrieli JD, 2003. Neural correlates of the automatic processing of threat facial signals. Journal of Neuroscience 23, 5627–5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]