Abstract

Background

Excessive drinking is a significant cause of mortality, morbidity and social problems in many countries. Brief interventions aim to reduce alcohol consumption and related harm in hazardous and harmful drinkers who are not actively seeking help for alcohol problems. Interventions usually take the form of a conversation with a primary care provider and may include feedback on the person's alcohol use, information about potential harms and benefits of reducing intake, and advice on how to reduce consumption. Discussion informs the development of a personal plan to help reduce consumption. Brief interventions can also include behaviour change or motivationally‐focused counselling.

This is an update of a Cochrane Review published in 2007.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of screening and brief alcohol intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in hazardous or harmful drinkers in general practice or emergency care settings.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, and 12 other bibliographic databases to September 2017. We searched Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Science Database (to December 2003, after which the database was discontinued), trials registries, and websites. We carried out handsearching and checked reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of brief interventions to reduce hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption in people attending general practice, emergency care or other primary care settings for reasons other than alcohol treatment. The comparison group was no or minimal intervention, where a measure of alcohol consumption was reported. 'Brief intervention' was defined as a conversation comprising five or fewer sessions of brief advice or brief lifestyle counselling and a total duration of less than 60 minutes. Any more was considered an extended intervention. Digital interventions were not included in this review.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We carried out subgroup analyses where possible to investigate the impact of factors such as gender, age, setting (general practice versus emergency care), treatment exposure and baseline consumption.

Main results

We included 69 studies that randomised a total of 33,642 participants. Of these, 42 studies were added for this update (24,057 participants). Most interventions were delivered in general practice (38 studies, 55%) or emergency care (27 studies, 39%) settings. Most studies (61 studies, 88%) compared brief intervention to minimal or no intervention. Extended interventions were compared with brief (4 studies, 6%), minimal or no intervention (7 studies, 10%). Few studies targeted particular age groups: adolescents or young adults (6 studies, 9%) and older adults (4 studies, 6%). Mean baseline alcohol consumption was 244 g/week (30.5 standard UK units) among the studies that reported these data. Main sources of bias were attrition and lack of provider or participant blinding. The primary meta‐analysis included 34 studies (15,197 participants) and provided moderate‐quality evidence that participants who received brief intervention consumed less alcohol than minimal or no intervention participants after one year (mean difference (MD) ‐20 g/week, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐28 to ‐12). There was substantial heterogeneity among studies (I² = 73%). A subgroup analysis by gender demonstrated that both men and women reduced alcohol consumption after receiving a brief intervention.

We found moderate‐quality evidence that brief alcohol interventions have little impact on frequency of binges per week (MD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.14 to ‐0.02; 15 studies, 6946 participants); drinking days per week (MD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.23 to ‐0.04; 11 studies, 5469 participants); or drinking intensity (‐0.2 g/drinking day, 95% CI ‐3.1 to 2.7; 10 studies, 3128 participants).

We found moderate‐quality evidence of little difference in quantity of alcohol consumed when extended and no or minimal interventions were compared (‐20 g/week, 95% CI ‐40 to 1; 6 studies, 1296 participants). There was little difference in binges per week (‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.12; 2 studies, 456 participants; moderate‐quality evidence) or difference in days drinking per week (‐0.45, 95% CI ‐0.81 to ‐0.09; 2 studies, 319 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). Extended versus no or minimal intervention provided little impact on drinking intensity (9 g/drinking day, 95% CI ‐26 to 9; 1 study, 158 participants; low‐quality evidence).

Extended intervention had no greater impact than brief intervention on alcohol consumption, although findings were imprecise (MD 2 g/week, 95% CI ‐42 to 45; 3 studies, 552 participants; low‐quality evidence). Numbers of binges were not reported for this comparison, but one trial suggested a possible drop in days drinking per week (‐0.5, 95% CI ‐1.2 to 0.2; 147 participants; low‐quality evidence). Results from this trial also suggested very little impact on drinking intensity (‐1.7 g/drinking day, 95% CI ‐18.9 to 15.5; 147 participants; very low‐quality evidence).

Only five studies reported adverse effects (very low‐quality evidence). No participants experienced any adverse effects in two studies; one study reported that the intervention increased binge drinking for women and two studies reported adverse events related to driving outcomes but concluded they were equivalent in both study arms.

Sources of funding were reported by 67 studies (87%). With two exceptions, studies were funded by government institutes, research bodies or charitable foundations. One study was partly funded by a pharmaceutical company and a brewers association, another by a company developing diagnostic testing equipment.

Authors' conclusions

We found moderate‐quality evidence that brief interventions can reduce alcohol consumption in hazardous and harmful drinkers compared to minimal or no intervention. Longer counselling duration probably has little additional effect. Future studies should focus on identifying the components of interventions which are most closely associated with effectiveness.

Plain language summary

Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations

What is the aim of this review?

We aimed to find out whether brief interventions with doctors and nurses in general practices or emergency care can reduce heavy drinking. We assessed the findings from 69 trials that involved a total of 33,642 participants; of these 34 studies (15,197 participants) provided data for the main analysis.

Key messages

Brief interventions in primary care settings aim to reduce heavy drinking compared to people who received usual care or brief written information. Longer interventions probably make little or no difference to heavy drinking compared to brief intervention.

What was studied in the review?

One way to reduce heavy drinking may be for doctors and nurses to provide brief advice or brief counselling to targeted people who consult general practitioners or other primary health care providers. People seeking primary healthcare are routinely asked about their drinking behaviour because alcohol use can affect many health conditions.

Brief interventions typically include feedback on alcohol use and health‐related harms, identification of high risk situations for heavy drinking, simple advice about how to cut down drinking, strategies that can increase motivation to change drinking behaviour, and the development of a personal plan to reduce drinking. Brief interventions are designed to be delivered in regular consultations, which are often 5 to 15 minutes with doctors and around 20 to 30 minutes with nurses. Although short in duration, brief interventions can be delivered in one to five sessions. We did not include digital interventions in this review.

Search date

The evidence is current to September 2017.

Study funding

Funding sources were reported by 60 (87%) studies. Of these, 58 studies were funded by government institutes, research bodies or charitable foundations. One study was partly funded by a pharmaceutical company and a brewers association, another by a company developing diagnostic testing equipment. Nine studies did not report study funding sources.

What are the main results of the review?

We included 69 controlled trials conducted in many countries. Most studies were conducted in general practice and emergency care. Study participants received brief intervention or usual care or written information about alcohol (control group).

The amount of alcohol people drank each week was reported by 34 trials (15,197 participants) at one‐year follow‐up and showed that people who received the brief intervention drank less than control group participants (moderate‐quality evidence). The reduction was around a pint of beer (475 mL) or a third of a bottle of wine (250 mL) less each week.

Longer counselling probably provided little additional benefit compared to brief intervention or no intervention.

One trial reported that the intervention adversely affected binge drinking for women, and two reported that no adverse effects resulted from receiving brief interventions. Most studies did not mention adverse effects.

Quality of the evidence

Findings may have been affected because participants and practitioners were often aware that brief interventions focused on alcohol. Furthermore, some participants could not be contacted at one‐year follow‐up to report drinking levels. Overall, evidence was assessed as mostly moderate‐quality. This means the reported effect size and direction is likely to be close to the true effect of these interventions.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Excessive drinking is a significant cause of mortality, morbidity and social problems in many countries, with a greater global cost to health than for tobacco (WHO 2014). The true impact of alcohol on the health of individuals and the wider community is difficult to estimate because of the many effects resulting from alcohol use, including increased levels of violence, accidents and suicide (GBD 2017). The heavy burden that alcohol use imposes on health, and its significant economic consequences, has led to national and international programmes and policies that seek to reduce consumption levels and so reduce a primary cause of avoidable ill health (Bailey 2011; UK Government 2012).

The impetus for a preventive approach to alcohol problems has been reinforced by epidemiological research. At a population level, most alcohol‐related harm is not due to drinkers with severe alcohol dependence but attributable to a much larger group of excessive (hazardous and harmful drinkers) whose consumption exceeds recommended drinking levels (Anderson 1991). Therefore, at a population level, the greatest impact on alcohol‐related problems can be made by addressing interventions aimed for excessive rather than dependent drinkers (McGovern 2013).

Description of the intervention

Early identification and secondary prevention of alcohol problems, using screening and brief interventions in primary care, has long been advocated as a strategy to reduce excessive drinking and is the focus of a great deal of research (O'Donnell 2014).

Brief intervention is grounded in social‐cognitive theory and typically incorporates some or all of the following elements:

feedback on the person's alcohol use and any alcohol‐related harm clarification as to what constitutes low risk alcohol consumption;

information on the harms associated with risky alcohol use;

benefits of reducing intake;

advice on how to reduce intake;

motivational enhancement; analysis of high risk situations for drinking and coping strategies; and

the development of a personal plan to reduce consumption.

Brief intervention is typically structured according to the FRAMES approach which involves practitioners: giving Feedback on the person’s intake, impressing the Responsibility for change onto them, offering Advice, listing a Menu of options for behavioural change, having an Empathic approach and building Self‐efficacy in the person receiving the brief intervention (Miller 1994).

Some brief intervention trials have included motivational interviewing (Rollnick 1995) or lifestyle counselling approaches. Although forms of brief intervention vary among studies (Heather 1995), core features in primary care are delivery by generalist healthcare workers, targets excessive (hazardous and harmful) drinkers who tend not to be seeking help for alcohol problems, and aims for reduced consumption and alcohol‐related harms. Brief interventions in primary care have focused less frequently on dependent drinkers because these people often need more intensive treatment than is available routinely and are likely to require a goal of total abstinence.

How the intervention might work

Excessive drinking can be identified routinely in general practice and emergency care. People are often asked about alcohol consumption during new patient registrations, general health checks, specific disease clinics (e.g. hypertension, diabetes) and other health screening procedures. This identification process is often referred to as screening and typically involves asking a relatively small number of standardised questions about alcohol consumption (e.g. quantity, frequency and intensity of use) and any associated effects using a validated questionnaire or screening tool. Screening and brief alcohol intervention in routine primary care typically occurs opportunistically ‐ when the main purpose of the appointment is something other than help with drinking.

The brief intervention must be delivered within the limited time frame of a standard consultation (typically 5 to 15 minutes for general practitioners (GPs), or up to 30 minutes for nurses). It also needs to fit in with routine practice (e.g. initial screening plus either referral to a practice colleague or later return for intervention). However, brief intervention trials have evaluated a wide range of activity. The shortest of these is a single 5 to 10 minute session of structured advice delivered by GPs or nurses. More intense interventions can provide multiple sessions of motivational interviewing or some other form of counselling, accompanied by repeated follow‐up and delivered by primary healthcare workers. Other variations relate to the type of population being treated, the amount of training and support received by therapists, the theoretical basis underlying the intervention, and the use of accompanying written material.

Why it is important to do this review

Although previous reports and reviews have indicated beneficial outcomes of screening and brief intervention for excessive drinkers, crucial questions remain concerning its impact in routine practice and applicability to the broader population (Agosti 1995; Bien 1993; Moyer 2002; NHS CRD 1993; Poikolainen 1999; UK Government 2012; Wilk 1997). Whilst there appears to be little doubt that screening and brief intervention with excessive drinkers can work successfully in research settings where intervention delivery and follow‐up is carefully managed (Flay 1986), there has been uncertainty about extrapolation to real world routine primary care (Heather 2014; Holder 1999; Kaner 2001). However, if health professionals are to be encouraged to adopt and administer brief interventions in routine practice, it is necessary to establish a realistic effect size for brief intervention delivered in clinically‐relevant contexts.

The term 'hazardous and harmful drinkers' contains a number of subgroups (e.g. young people, older people, and ethnic minorities). Little is known about how these subgroups respond to brief intervention in primary care. Differential loss of participants from early brief intervention trials led to a call for caution in generalising results to routine practice (Edwards 1997) but types of participants who were lost remains unclear. Therefore, there is need to characterise the types of drinkers for whom brief interventions have a positive impact and any subgroups who have not been represented in the trials to date.

This is an update of our 2007 review (Kaner 2007). An update was necessary because many trials have been conducted since initial publication and relevant developments have occurred in the wider literature; consequently we have added 42 new trials and conducted new subgroup analyses. Firstly, specific tools to measure efficacy and effectiveness have been published (Gartlehner 2006; Koppenaal 2011), which supercede the scale used in the 2007 review. Secondly, the concepts of screening reactivity and assessment reactivity have been defined (McCambridge 2011). These definitions describe how the very process of screening for alcohol consumption or having the effects of drinking assessed may influence reported drinking behaviour, independent of any further brief intervention input. Furthermore, recent literature contains a bigger subgroup of trials that focus on emergency care rather than general practice‐based primary care, whereas previously the vast majority of the trials took place in primary care. Finally, interventions in more recent trials are often based on counselling techniques such as motivational interviewing rather than simpler advice‐based input.

An important development has been in the digitisation of interventions to reduce hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption, using technologies such as websites and smart phone apps. These interventions (and their comparison with face‐to‐face brief interventions) are the focus of another Cochrane Review (Kaner 2017), and were excluded from this review.

Objectives

Main objective

To assess the effectiveness of screening and brief alcohol intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in hazardous or harmful drinkers in general practice or emergency care settings.

Secondary objectives

Specific questions addressed by this review were:

Are brief interventions superior to minimal or no intervention?

Are extended brief interventions containing more or longer sessions superior to no intervention or to standard brief interventions?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials and cluster‐randomised controlled trials were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

People who routinely presented to general practice, emergency care or other primary care settings for a range of health problems, whose alcohol consumption was identified by a screening tool as being excessive, or who had experienced harm as a result of their drinking behaviour. Studies that recruited participants who were seeking treatment specifically for an alcohol problem or who were mainly dependent on alcohol were excluded.

We defined primary care as all immediately accessible, general healthcare facilities. People needed to be able to access services on demand rather than through a specialist referral, and services needed to cover a broad range of problems. Participants recruited in emergency departments and trauma centres were included if this was the first contact following the emergency event.

Types of interventions

Experimental condition: Brief intervention comprised a single session and up to a maximum of five sessions of verbally‐delivered information, advice or counselling that was designed to achieve a reduction in risky alcohol consumption, alcohol‐related problems, or both (Babor 1994).

Control conditions: screening or assessment only, usual care for the presenting condition or written information such as a health or alcohol education leaflet (described as minimal intervention).

Psychology‐based counselling aimed at reducing alcohol consumption or alcohol‐related problems that was unlikely to occur in routine practice, for reasons of length or intensity, were referred to as extended intervention. We defined extended interventions as those that consisted of more than five sessions or total combined session durations was more than 60 minutes.

Interventions specifically aimed at people who were dependent on alcohol were excluded. Digital interventions (e.g. websites, smart phone apps or computer programmes) were excluded because these were investigated in another Cochrane Review (Kaner 2017).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was consumption of alcohol. This was most often reported as:

Self‐reported or other reports of drinking quantity (e.g. drinks per week).

Self‐reported or other reports of binge drinking frequency (e.g. number of binges per week).

Self‐reported or other reports of drinking frequency (e.g. drinking days per week).

Self‐reported or other reports of drinking intensity (e.g. number of drinks per drinking day).

Self‐reported or other reports of drinking within recommended limits (e.g. government recommended limits). Although limits vary among countries, practitioners tend to use the national government recommended limits as a guide.

Although not specified in the protocol, we also noted the following consumption outcomes if these were reported.

Proportion of heavy drinkers (in Kaner 2007 a common example was > 35 units/week, but these definitions have reduced recently).

Proportion of binge drinkers.

Secondary outcomes

Levels of laboratory markers of reduced alcohol consumption (e.g. serum gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV)).

Alcohol‐related harm to drinkers or others affected (e.g. via questionnaires such as the drinking problems index).

Patient satisfaction measures.

Health‐related quality of life.

Economic measures including use of health services.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Current update searches

We searched the following databases from 2005 to September 2017:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 8, 2017; searched 25 September 2017);

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Issue 9, 2017; searched 25 September 2017);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (Issue 2, 2015; searched 25 September 2017);

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1966 to September week 2, 2017; searched 21 September 2017);

Embase (Ovid 1980 to 2017 week 38; searched 21 September 2017);

PsycINFO (Ovid 1840 to September week 3 2017; searched 21 September 2017);

CINAHL (EBSCO, 1982 to 25 September 2017);

Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) (Web of Science, 2005 to 25 September 2017);

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (CPCI‐S) (2005 to 25 September 2017);

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) (Web of Science, 2005 to 25 September 2017);

Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) (Web of Science, 2015 to 25 September 2017);

NHS‐EED (Wiley, issue 2 of 4, 2015; searched 25 September 2017).

Search strategies are reported in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; and Appendix 9.

We applied no language or publication restrictions.

Previous searches

We searched the following sources from the earliest available date to 2006:

Cochrane Drug and Alcohol Group specialised register (February 2006);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1966 to 2005);

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to 2005);

PsycINFO (Ovid, 1840 to 2005);

CINAHL (EBSCO, 1982 to 2005);

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) (Web of Knowledge, 1970 to 2005);

Science Citation Index (SCI) (Web of Knowledge, 1970 to 2005);

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group specialised register (2005);

Alcohol Education and Research Council (AERC) alcohol library, searched 2005;

HEED (searched 3 December 2014 ‐ no access for the September 2017 search); and

Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Science Database, ETOH (1972 to 2003, after which the database was discontinued).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews. We contacted key informants and experts to enquire about unpublished work and ongoing research, particularly through links with the International Network on Brief Interventions for Alcohol and other drugs (INEBRIA).

We also searched clinicaltrials.gov (25 September 2017).

We searched organisational websites for reports of eligible trials on 26 September 2017:

USA Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), National Registry of Evidence Based Programs and Practices (NREPP);

SAMHSA Screening Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT);

Information on Drugs and Alcohol (IDA);

Alcohol Concern;

Drug and Alcohol Findings;

International Network on Brief Interventions for Alcohol and Other Drugs (INEBRIA); and

National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed titles and abstracts in EndNote (EndNote 2015). If the title, abstract and keywords did not yield enough information to ascertain potential for inclusion then the full paper was retrieved.

We initially piloted the inclusion criteria on six retrieved papers for the original review (Kaner 2007). Two review authors independently assessed the study eligibility for both the original review and this update. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus, or adjudication by a third review author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data using a piloted data extraction form. We extracted citation information, participants' characteristics (e.g. age, gender, baseline alcohol consumption), intervention descriptions (e.g. number, content and frequency of brief intervention sessions), setting and outcome data to RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014). We also extracted methodological information to enable critical appraisal. Where data were missing or unclear we emailed study authors to request clarification or further data.

In the protocol, we specified the use of an intention‐to‐treat analysis as a criterion of quality. However, this was revised in light of current Cochrane Handbook guidance (Higgins 2011b). Intention‐to‐treat analysis is usually understood to mean that participants were analysed in the groups to which they were randomised, regardless of the treatment they actually received. However, it is also sometimes understood to imply that all participants were included regardless of whether their outcomes were actually collected, which requires imputation of missing outcomes. Rather than using intention‐to‐treat analysis as a quality criterion, we attempted to extract data for participants in the groups to which they were randomised, regardless of the treatment they actually received, i.e. corresponding to the more widely agreed definition of intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Outcome data on quantity of alcohol consumed in a specific time period were converted to grams per week for each study. Drinks and units were converted to grams using either a conversion factor reported in the relevant paper or, if none was reported, using the conversion factor appropriate for the country where the study was conducted (Furtwaengler 2013; Gual 1999; Heather 2006; Miller 1991). Months were converted to weeks by multiplying by 52/12. Drinking intensity, drinking days, drinking sessions and occasions were all assumed to be equivalent to drinking days. For laboratory markers of gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT) (Israel 1996; Romelsjö 1989; Scott 1990; Wallace 1988), microkatals/litre were converted to international units/litre (IU/L) by multiplying by 60. Where relevant, values from analyses that involved adjustment for missing data (e.g. through the imputation of baseline values for participants lacking follow‐up data) were used in preference to unadjusted values.

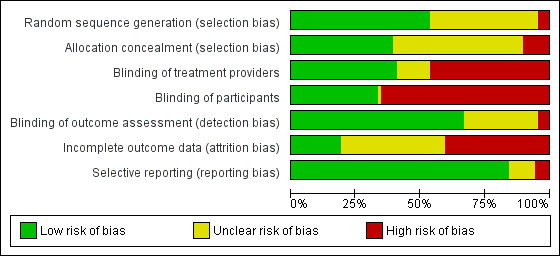

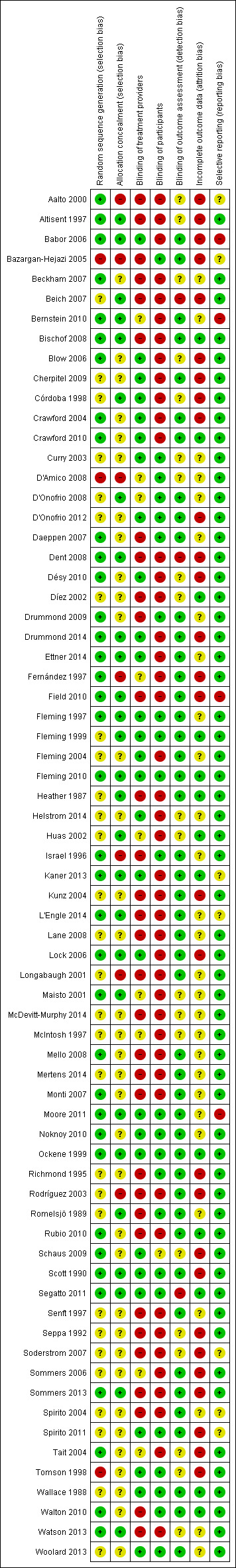

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed potential risk of bias resulting from the trial design according to Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool as described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). This is a two‐part tool, addressing the following domains.

Sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and providers (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

Other source of bias.

The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias in terms of low, high or unclear risk. We used the criteria indicated by the Cochrane Handbook adapted to the addiction field to make these judgments (see Appendix 10).

Any discrepancies between review authors were resolved by discussion to achieve consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated the mean difference (MD) and standard deviation (SD) between the value of the outcome measure at 12 months following the brief intervention and the corresponding value following the control intervention for each continuous outcome. If standard deviations of final values were not available, the change score (i.e. the difference between the final and initial value of the outcome measure) was used if its standard deviation was available. If no standard deviations were available, these trials were omitted from the primary analysis but included in a sensitivity analysis using imputed standard deviations.

The risk difference (RD) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for dichotomous outcomes because 95% CIs are intuitively clearer and this was consistent with the approach applied previously (Kaner 2007).

Unit of analysis issues

We extracted a direct estimate of the desired treatment effect and its standard error where analyses accounted for clustering in cluster‐randomised trials. We assigned imputed standard deviations to the treatment and control groups, such that the standard error of the treatment effect estimated by the weighted mean difference method in RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014) was the same as that reported in the analysis accounting for clustering. If the analysis did not account for the cluster design, we extracted the number of clusters randomised to each intervention, the average cluster size in each intervention group, and the outcome data for all participants in each intervention group.

A design effect was estimated using an external estimate of the intra‐cluster coefficient (ICC). In this way we inflated the variance of the effect estimate. In the case of dichotomous outcomes, this involved reducing the total number of participants and the number of participants with events, whilst keeping the proportion with events fixed. It was then possible to enter data to RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014), and combine cluster‐randomised trials with individually randomised trials in the same meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to obtain missing data and seek clarification where appropriate. Studies with missing standard deviations or for which the number of participants in each arm was not reported were excluded from the main analysis for the associated continuous measure. These studies were included in a sensitivity analysis, using imputed values for the standard deviations or the number of participants in each arm.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The magnitude of heterogeneity among trials was assessed using the I² statistic (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003). The statistical significance of heterogeneity was assessed using P values derived from Chi² tests (Deeks 2001).

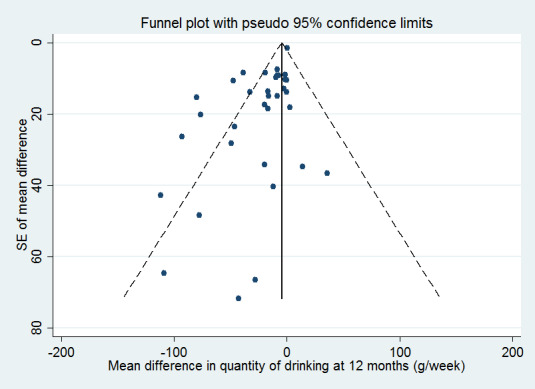

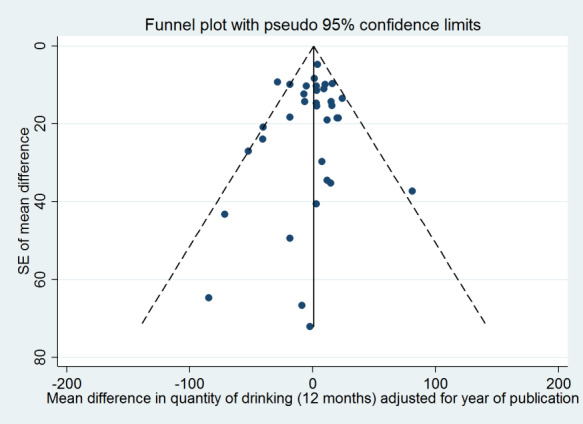

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed whether studies appeared to have incomplete reporting bias by noting in the risk of bias assessments whether the reported outcomes matched methods sections or any published protocols. We made every effort to minimise publication bias by searching a wide range of databases and sources of grey literature and not restricting by language or publication status. We constructed funnel plots (plots of the effect estimate from each study against the effect standard error) to assess potential for bias related to the size of the trials, which could indicate possible publication bias.

Data synthesis

The weighted mean difference method was used to estimate pooled effect sizes and 95% CI, if sufficient studies reporting the outcome were available. Most trials reported weekly or monthly alcohol consumption and few reported drinking frequency or intensity. Hence, the meta‐analysis of alcohol quantity consumed per week provided most information and constituted the primary meta‐analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014). Because the populations and interventions evaluated by the trials were so heterogeneous, it was deemed more appropriate to use a random‐effects model for all analyses (DerSimonian 1986). Random‐effects meta‐regression modelling was conducted using the metareg command in Stata version 14.1 (Stata 2015). Meta‐regression was used to assess any differences in calculated effect associated with the publication date of studies, baseline consumption of participants, duration of treatment, and efficacy/effectiveness score.

For dichotomous outcomes (participant classified as a heavy or binge drinker), RDs and 95% CIs were calculated and pooled in a random‐effects meta‐analysis using Mantel‐Haenszel test weighting.

We addressed variable risk of bias using sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis).

If trials had more than one control arm and the various control arms were very similar (e.g. Sommers 2013), the results for these arms were combined by calculating weighted means of continuous outcomes and summing dichotomous outcomes; likewise for very similar treatment arms (D'Onofrio 2012).

'Summary of findings' tables

We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence. GRADE takes into account issues related to both internal and external validity, such as directness of results (Atkins 2004; Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2011). The 'Summary of findings' tables present main review findings in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, 'Summary of findings' tables provide key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence.

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

We used GRADEpro GDT 2015 to import data from Review Manager 2014 for the main outcomes of quantity of drinking (g/week), frequency of drinking (days per week and binges per week) and intensity of drinking (drinks/drinking day) for each of the comparisons (brief intervention versus minimal or no intervention, extended intervention versus minimal or no intervention, extended intervention versus brief intervention) (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3).

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Brief intervention compared to no or minimal intervention for people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption.

| Brief intervention compared to no or minimal intervention for people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption as identified by a screening tool Setting: primary care (directly accessible to participant, no referral required), mostly high income countries Intervention: brief intervention Comparison: no or minimal intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with Brief intervention | |||||

| Quantity of drinking (g/week) at 12 months | The mean quantity of drinking (g/week) at 12 months was 238 g/week | MD 20.08 g/week lower (28.36 lower to 11.81 lower) | ‐ | 15197 (34 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Heterogeneity was substantial (73%) but not unexplained; interventions differed in content and delivery. The direction of effect favoured the intervention in 82% of the studies |

| Frequency of drinking (no. binges/wk) at 12 months | The mean frequency of drinking (no. binges/wk) at 12 months was 0.98 binges/week | MD 0.08 binges/week lower (0.14 lower to 0.02 lower) | ‐ | 6946 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Frequency of drinking (no. days drinking/wk) at 12 months | The mean frequency of drinking (no. days drinking/wk) at 12 months was 2.73 drinking days/week | MD 0.13 drinking days/week lower (0.23 lower to 0.04 lower) | ‐ | 5469 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Intensity of drinking (g/drinking day) at 12 months | The mean intensity of drinking (g/drinking day) at 12 months was 55 g/drinking day | MD 0.18 g/drinking day lower (3.09 lower to 2.73 higher) | ‐ | 3128 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Adverse effects | Only five trials reported adverse effects. No participants experienced any adverse effects in two trials; one trial reported that the intervention increased binge drinking for women; and two trials reported adverse events related to driving outcomes but concluded they were equivalent in both study arms. | ‐ | (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 12 |

||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 High levels of performance bias due to difficulties with blinding participants and providers 2 Downgraded due to inconsistency and imprecision; very few studies provided data, and reporting is inconsistent and data unavailable in a format conducive to meta‐analysis

Summary of findings 2. Extended intervention compared to no or minimal intervention for people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption.

| Extended intervention compared to no or minimal intervention for people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption Setting: primary care (directly accessible to participant, no referral required) Intervention: extended intervention Comparison: no or minimal intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with Extended intervention | |||||

| Quantity of drinking (g/week) at 12 months | The mean quantity of drinking (g/week) at 12 months was 236 g/week | MD 19.50 g/week lower (40.47 lower to 1.48 higher) | ‐ | 1296 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Frequency of drinking (no. binges/wk) at 12 months | The mean frequency of drinking (no. binges/wk) at 12 months was 1.3 binges/week | MD 0.08 binges/week lower (0.28 lower to 0.12 higher) | ‐ | 456 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Frequency of drinking (no. days drinking/week) at 12 months | The mean frequency of drinking (no. days drinking/week) at 12 months was 2.1 drinking days/week | MD 0.45 drinking days/week lower (0.81 lower to 0.09 lower) | ‐ | 319 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Intensity of drinking (g/drinking day) at 12 months | The mean intensity of drinking (g/drinking day) at 12 months was 76.6 g/day | MD 8.51 g/day lower (25.69 lower to 8.67 higher) | ‐ | 158 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 High risk of performance bias due to difficulties with blinding participants and providers 2 Imprecision suggested by small number of trials/participants

Summary of findings 3. Extended intervention compared to brief intervention for people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption.

| Extended compared to brief intervention for people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption Setting: primary care (directly accessible to participant, no referral required) Intervention: extended intervention Comparison: brief intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with brief intervention | Risk with Extended | |||||

| Quantity of drinking (g/week) at 12 months | The mean quantity of drinking (g/week) at 12 months was 251 g/week | MD 1.54 g/week higher (42.01 lower to 45.10 higher) | ‐ | 552 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Frequency of binge drinking (no. binges/wk) at 12 months ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Frequency of drinking (no. days drinking/week) at 12 months | The mean frequency of drinking (no. days drinking/week) at 12 months was 2.82 days drinking/week | MD 0.51 drinking days/week lower (1.21 lower to 0.19 higher) | ‐ | 147 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | |

| Intensity of drinking (g/drinking day) at 12 months | The mean intensity of drinking (g/drinking day) at 12 months was 70 g/drinking day | MD 1.7 g/drinking day lower (18.86 lower to 15.46 higher) | ‐ | 147 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Imprecision suggested by very wide confidence intervals

2 High risk of performance bias due to difficulties blinding participants and providers

3 Imprecision suggested by small number of trials/participants

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We carried out subgroup analyses to address the effects of each of the following:

Applicability issues ‐ population characteristics, setting and mode of intervention

Where reported, we recorded the gender, age and ethnicity of included participants to assess how applicable brief interventions are to different groups of people presenting to primary care. We conducted subgroup analyses for the primary outcome (alcohol consumption at 12‐months follow‐up) based on gender and according to adolescents or young adults versus with other age groups. We also examined study settings (general practice or emergency care). We also investigated the modality of the intervention (whether it was reported as advice or counselling‐based).

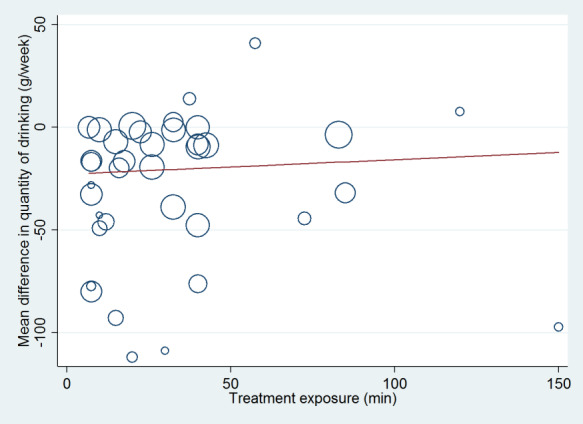

Variability in treatment exposure, control condition, year of publication, baseline consumption and follow up time scales

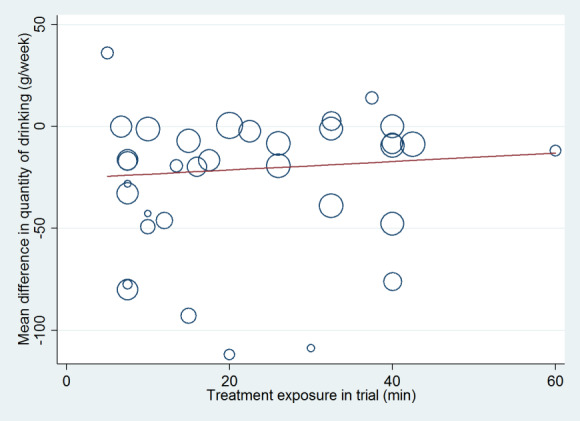

We calculated a measure of treatment exposure as the sum of the duration of the initial brief intervention plus the total duration of all booster sessions, in minutes. If a range of durations was given then we used the mean. If duration was not reported, we assumed the brief intervention to take 5 to 10 minutes, with a mean of 7.5 minutes. We carried out a meta‐regression analysis to look for any association between the impact of treatment on the quantity of alcohol consumed at 12 months and the level of treatment exposure. We performed this analysis separately for trials that compared a brief intervention with minimal or no intervention, and for trials that compared an extended intervention with minimal or no intervention. Only results from the comparison of extended intervention versus minimal or no intervention were included in meta‐regression analysis for trials that included three intervention arms (minimal or no intervention, brief intervention and extended intervention).

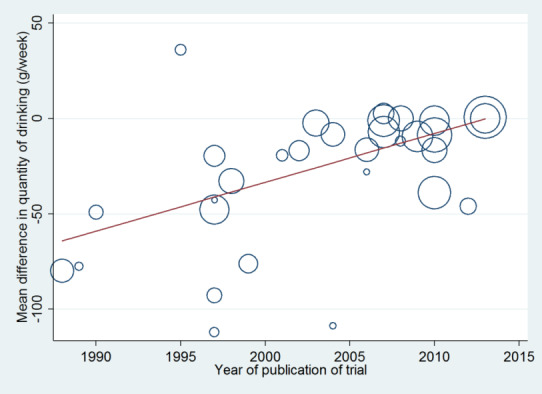

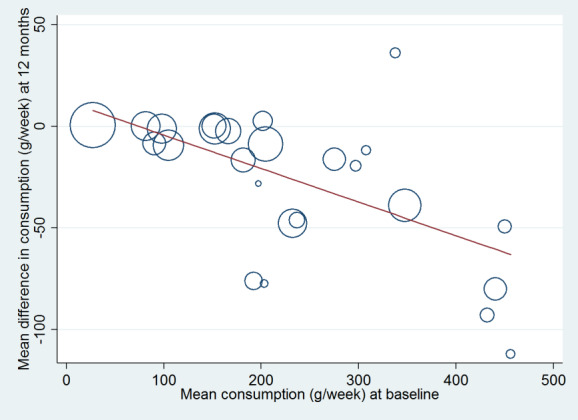

The definition of excessive drinking has changed over time (e.g. NHMRC 2009; UK Department of Health 2016), particularly regarding the threshold for entry into trials. To examine the impact of this and any other temporal factors, trials were classified by year of publication and meta‐regression analysis performed to look for any relationship between publication date and the primary outcome measure. This enabled examination of whether the intervention effect had diminished as the definition of excessive drinking has reduced. A meta‐regression analysis was also conducted on whether the primary outcome measure was related to the level of consumption at baseline. Because baseline consumption varied over time, meta‐regression analysis informed examination of changes when adjustment was made for year of publication. We analysed studies added for this update separately from studies included in the previous review version (Kaner 2007). This analysis was planned to illustrate if primary outcome measure findings were compatible.

The primary analyses reported outcomes at 12 month follow‐up, reflecting the large number of studies with information at this time point, and our interest in investigating robust changes in drinking behaviour rather than shorter term or transient changes. Where sufficient information was available (specifically, for quantity of alcohol consumed and frequency of drinking), analyses were undertaken based on other follow‐up times. The minimum follow‐up time was six months.

Effectiveness and efficacy

Efficacy trials tend to take place in tightly controlled research environments. They typically recruit a more homogenous group of participants than effectiveness trials. The former involve practitioners or interventionists who are likely to have more skills in alcohol intervention or behaviour change work than generalists working in routine primary care. They may occur in specialist healthcare or university settings and are often well‐resourced, supported or closely monitored to ensure that interventions are delivered precisely as intended. Conversely, effectiveness trials are closer to a real world situation and are more representative of routine clinical practice. These tend to have a broader range of participants, involve clinicians who routinely work in primary care and allow more flexibility in the way the intervention is delivered. We developed a scale based on the work of Shadish 2000 to categorise included trials along a spectrum of efficacy to effectiveness.

Two review authors independently classified each trial (see Table 4). If an item appeared to be partially clinically representative on any item, then we gave a midpoint score (either 1 or 0.5 as applicable). If the study authors did not report data relating to a particular item, then we allocated an intermediate score to limit bias in the trial toward the effectiveness or efficacy domain. We resolved disagreements concerning classification by discussion to achieve consensus.

1. Effectiveness ‐ efficacy scale.

| Scale item | Score | Meaning |

| Patients and problems | 2 | Clinically representative people initially present with a typically wide range of problems via self‐referral or invitation for a health check |

| 1 | Mixed: e.g. routine patients but paid for participation in study, or patients prescreened then invited research representative subjects may be paid patients | |

| 0 | Researcher‐solicited volunteers (e.g. via advertisement) or referrals from specialist services | |

| Practice context | 2 | Clinically representative is a community‐based setting in which a range of clinical services are usually provided to patients |

| 1 | Mixed | |

| 0 | Research representative is a setting in which the research function clearly dominates any clinical one (e.g. clinic at a university or hospital) | |

| Practitioners and therapists | 2 | Clinically representative practitioners are practising doctors, nurses and qualified therapists who earn their main living by providing health services in primary care |

| 1 | Qualified clinician but specifically recruited for the study | |

| 0 | Research representative practitioners are non‐clinicians, or clinicians in training, who are contracted to deliver interventions for the purposes of the study | |

| Intervention content | 2 | Clinically representative intervention fits with current practice in terms of timing, content or style (e.g. for primary care 5 to 15 minutes for a GP; 20 to 30 minutes for a nurse or initial screening accompanied by a return visit for brief intervention; for emergency settings motivational interviewing‐style intervention fits in here, e.g. 45 minutes |

| 0 | Research representative treatment would not normally occur in routine practice e.g. unusually long consultations | |

| Therapeutic flexibility | 1 | Clinically representative: allows professional judgement in how an intervention is delivered e.g. freedom to focus on particular issues according to patient need |

| ½ | Flexible protocol (tailored to participants) | |

| 0 | Research representative: strict adherence to a prescribed protocol or script that does not allow for variability in practice | |

| Pre‐therapy training | 1 | Clinically representative training in intervention procedures occurs according to typical CPD/CME procedures (e.g. outreach visits, seminars, one‐off training days). Full day off‐site (for emergency care staff) |

| ½ | Full day off‐site (for primary care staff) | |

| 0 | Research representative training is unusually intensive or requiring of atypical levels of interest or motivation, e.g. prolonged or intensive courses, formal qualification | |

| Intervention support | 1 | Clinically representative support occurs within standard practice resources (e.g. colleague assistance with screening, IT flagging, provision of general (uncustomised) manual. Note for emergency care settings some procedures are clinically representative (e.g. taking bloods and doing various tests) |

| 0 | Research representative support would not typically be available (e.g. researcher help to flag notes, extra staff for period of the trial) | |

| Intervention monitoring | 1 | Clinically representative monitoring of intervention delivery does not interfere with practitioners' behaviour or their relationships with patients |

| 0 | Research representative monitoring would be direct observation of therapist behaviour or ongoing/immediate feedback to practitioners after each session |

Abbreviations: CPD: continuing professional development; CME: continuing medical education; GP: general practitioner; IT: information technology

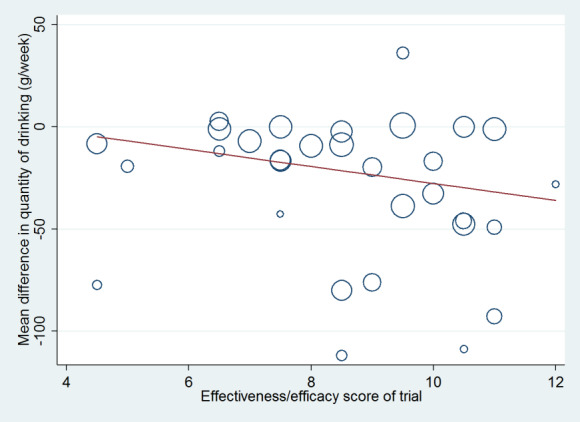

We summed all items for each study to provide an efficacy/effectiveness score of 0 to 12. If a study scored highly it was likely to be highly clinically relevant and was considered to be an effectiveness trial with high external validity. Conversely, if a trial scored very low, it was highly research relevant and considered to be an efficacy trial with high internal validity. We plotted the effect of brief intervention compared to minimal or no intervention on the quantity of alcohol consumed, as estimated from random‐effects meta‐analysis, against the efficacy/effectiveness score. We performed meta‐regression analysis to assess whether this treatment effect was related to the efficacy/efficiency score. We also categorised trials as effectiveness or efficacy trials based on score above or below the median and performed subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed based on the following characteristics.

-

Risk of bias: the primary meta‐analysis was repeated in analyses:

including only studies at low risk of bias due to allocation concealment; and

excluding studies at high risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data (i.e. attrition bias). We did not conduct a sensitivity analysis on the basis of risk of bias due to blinding because it is not possible to mask the nature of the intervention to providers or participants.

Missing standard deviations: we imputed the median standard deviation of the relevant outcome from other trials to both treatment and control groups of those with missing SDs.

Comparison of outcomes from cluster and individually randomised trials: a sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate the robustness of the conclusions, especially of the effect of varying assumptions about the magnitude of the ICC.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

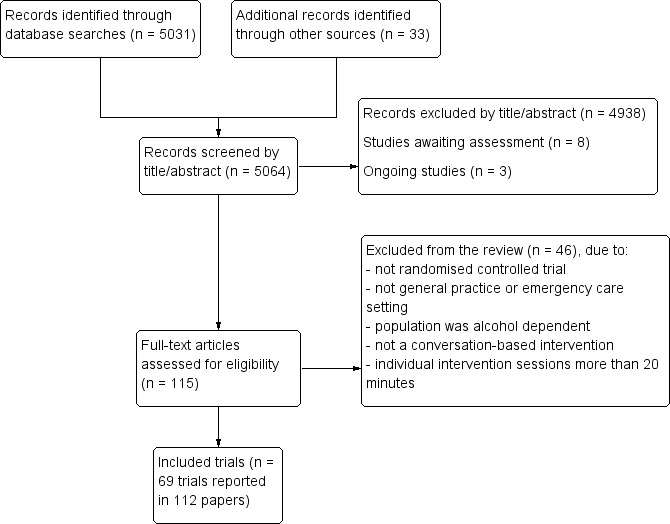

Searches identified 4004 potentially relevant records which were screened by title and abstract for eligibility. We retrieved 165 records for full text assessment. We added 42 studies (73 reports) for this update. The previous version of this review included 29 studies (39 reports) (Kaner 2007). This review included 69 studies (112 reports) (Figure 1; Characteristics of included studies),

1.

Study flow diagram.

We contacted 10 authors to request missing data or ask for clarification for this update.

Included studies

Population

The 69 included trials randomised a total of 33,642 participants (median 378, IQR 152 to 599). The mean percentage of male participants was 70%. Among the 45 trials that reported participants' age, the mean age was 40 years (SD 11.18). Eight trials focused on adolescents, young adults, or both (D'Amico 2008; Mertens 2014; Monti 2007; Segatto 2011; Spirito 2004; Spirito 2011; Tait 2004; Walton 2010). Four trials focused on older adults (aged > 55 years, aged > 60 years, or aged > 65 years) (Ettner 2014; Fleming 1999; Moore 2011; Watson 2013). Half the included trials (51%) reported participants' ethnicity; most participants were Caucasian (n = 28 trials, 78%).

In many cases, potential participants were excluded from trials if they were heavily alcohol dependent, already on an alcohol treatment programme, or had been in the previous year. However, some trials did not specify any exclusion criteria and included a proportion of participants who may have been dependent drinkers. These trials were included where most participants were not identified as being dependent on alcohol and the intervention was not aimed at dependent drinkers.

All participants were screened for eligibility into trials. Screening methods included general health questionnaires (such as the Health and Habits Survey), which sometimes incorporated alcohol consumption questions, and established alcohol screening tools such as CAGE, AUDIT or MAST. Some trials used a combination of these tools and determined alternative inclusion criteria to increase the likelihood of picking up relevant participants. Most trials administered the screening tool by telephone or in a clinic as soon as the person had registered for their appointment; one study administered the questionnaire by telephone following the intervention. There were difference in alcohol consumption inclusion criteria among trials, for example by number of units per week, screening tool score, level of binge, or high intensity drinking.

The mean overall baseline consumption for participants in the 32 trials that reported these data was 244 g/week (SD 119) (about 30 UK units). We included 13 trials that reported baseline consumption for men only (or recruited men only) and also reported the number of men randomised (Aalto 2000; Altisent 1997; Babor 2006; Beich 2007; Córdoba 1998; Díez 2002; Fleming 1997; Huas 2002; McIntosh 1997; Richmond 1995; Rubio 2010; Scott 1990; Wallace 1988). In these trials, the mean baseline consumption was 350 g/week (around 44 UK units). The corresponding value for the nine trials that reported consumption for women was 190 g/week (around 24 UK units). Mean baseline consumption differed between older studies included in the original review and the more recent studies included for this update. Previously, the overall mean baseline consumption in 21 trials reporting these data was 313 g/week (about 39 UK units). Only 11 trials added for this update reported overall mean baseline consumption, which was 181 g/week (about 23 UK units).

We included 14 trials that reported baseline measures of frequency of drinking which could be converted to days drinking per week; the mean value was 2.07 days/week (Aalto 2000; Bernstein 2010; Cherpitel 2009; Daeppen 2007; Fleming 1997; Fleming 2010; Helstrom 2014; Monti 2007; Noknoy 2010; Rubio 2010; Schaus 2009; Senft 1997; Soderstrom 2007; Spirito 2004). Baseline intensity of drinking was reported in 11 trials, in which the mean baseline value was 69 g/drinking day.

There was substantial heterogeneity among trials in terms of the mechanisms of screening participants for inclusion and in the content of both control and intervention arms.

Setting

Most trials (n = 34) took place in the USA (Babor 2006; Bazargan‐Hejazi 2005; Beckham 2007; Bernstein 2010; Blow 2006; Curry 2003; D'Amico 2008; Désy 2010; D'Onofrio 2008; D'Onofrio 2012; Ettner 2014; Field 2010; Fleming 1997; Fleming 1999; Fleming 2004; Fleming 2010; Helstrom 2014; Kunz 2004; Longabaugh 2001; Maisto 2001; McDevitt‐Murphy 2014; Mello 2008; Monti 2007; Moore 2011; Ockene 1999; Schaus 2009; Senft 1997; Soderstrom 2007; Sommers 2006; Sommers 2013; Spirito 2004; Spirito 2011; Walton 2010; Woolard 2013); 10 in the UK (Crawford 2004; Crawford 2010; Drummond 2009; Drummond 2014; Heather 1987; Kaner 2013; Lock 2006; Scott 1990; Wallace 1988; Watson 2013); six in Spain (Altisent 1997; Córdoba 1998; Díez 2002; Fernández 1997; Rodríguez 2003; Rubio 2010); four in Australia (Dent 2008; Lane 2008; Richmond 1995; Tait 2004); two each in Canada (Israel 1996; McIntosh 1997), Finland (Aalto 2000; Seppa 1992) and Sweden (Romelsjö 1989; Tomson 1998); and one each in Denmark (Beich 2007), France (Huas 2002) Germany (Bischof 2008), Poland (Cherpitel 2009), Switzerland (Daeppen 2007), South Africa (Mertens 2014), Kenya (L'Engle 2014), Brazil (Segatto 2011) and Thailand (Noknoy 2010).

Many interventions (n = 38, 55%) were delivered in general practices (Aalto 2000; Altisent 1997; Babor 2006; Beckham 2007; Beich 2007; Bischof 2008; Córdoba 1998; Curry 2003; D'Amico 2008; Díez 2002; Drummond 2009; Ettner 2014; Fernández 1997; Fleming 1997; Fleming 1999; Fleming 2004; Heather 1987; Helstrom 2014; Huas 2002; Israel 1996; Kaner 2013; L'Engle 2014; Lock 2006; Maisto 2001; McIntosh 1997; Mertens 2014; Moore 2011; Noknoy 2010; Ockene 1999; Richmond 1995; Romelsjö 1989; Rubio 2010; Scott 1990; Senft 1997; Seppa 1992; Tomson 1998; Wallace 1988; Watson 2013) and 27 (39%) were carried out in emergency departments (Bazargan‐Hejazi 2005; Bernstein 2010; Blow 2006; Cherpitel 2009; Crawford 2004; Crawford 2010; D'Onofrio 2008; D'Onofrio 2012; Daeppen 2007; Dent 2008; Désy 2010; Drummond 2014; Field 2010; Kunz 2004; Longabaugh 2001; Mello 2008; Monti 2007; Rodríguez 2003; Segatto 2011; Soderstrom 2007; Sommers 2006; Sommers 2013; Spirito 2004; Spirito 2011; Tait 2004; Walton 2010; Woolard 2013). Two studies took place in college health clinics (Fleming 2010; Schaus 2009), one in a public sexual health clinic (Lane 2008) and one in a veterans' affairs medical centre (McDevitt‐Murphy 2014). The studies by Lane 2008 and McDevitt‐Murphy 2014 were included because although they did not take place in general practice clinics, the interventions were available without referral to large groups of people. One study reported findings for two primary care settings and two other settings; only data from primary care settings were included in the meta‐analyses (Díez 2002).

Interventions

Brief intervention

Most studies (n = 61) compared brief intervention with minimal or no intervention. Of these, five also included an extended intervention arm (Aalto 2000; Bischof 2008; Longabaugh 2001; Maisto 2001; Richmond 1995), and eight included two minimal or no intervention arms (Bernstein 2010; Blow 2006; Cherpitel 2009; Daeppen 2007; D'Onofrio 2012; Heather 1987; Richmond 1995; Sommers 2013). Two studies included two intervention arms with identical content but delivered by different health professionals (Babor 2006; McIntosh 1997). Three studies included two substantively different intervention arms (Dent 2008; D'Onofrio 2012; Walton 2010). Four studies delivered minimal intervention which was sometimes described as a control condition and sometimes as an intervention condition (Heather 1987; Kaner 2013; Richmond 1995; Sommers 2006). One study compared an extended intervention with a brief intervention (Spirito 2011). Four studies compared only an extended intervention with minimal or no intervention (Israel 1996; L'Engle 2014; Monti 2007; Moore 2011).

All interventions provided feedback on the screening outcome plus structured advice about potential risks of heavy drinking and ways to reduce consumption. Feedback and structured advice took several formats: described as brief Intervention (and assumed to be based on FRAMES where not reported) (n = 27); based on or informed by motivational interviewing, Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET), or Brief Negotiated Interview (BNI) (n = 32); or based on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) techniques (n = 2). Some were backed up by diaries or exercises for the participant to complete at home, and follow‐up telephone calls.

A single brief intervention session was evaluated in 29 studies (Bazargan‐Hejazi 2005; Beckham 2007; Blow 2006; Cherpitel 2009; Córdoba 1998; Crawford 2004; Crawford 2010; D'Onofrio 2008; Daeppen 2007; Désy 2010; Díez 2002; Drummond 2014; Fernández 1997; Field 2010; Kaner 2013; Kunz 2004; Lane 2008; Lock 2006; Longabaugh 2001; Maisto 2001; McDevitt‐Murphy 2014; Mertens 2014; Ockene 1999; Rodríguez 2003; Scott 1990; Segatto 2011; Spirito 2004; Spirito 2011; Walton 2010). In the remaining studies, there were between two and five sessions, where individual sessions varied from one to a maximum of 60 minutes. General practitioners, nurse practitioners, health psychologists or trainee health psychologists administered the interventions.

Extended interventions

Extended interventions also provided feedback and structured advice but comprised either more than five sessions or more than 60 minutes in total. Extended interventions were based on motivational interviewing (five studies), MET (two studies), multiple FRAMES sessions (two studies), or CBT (one study) approaches. Extended interventions were evaluated in 10 trials (Aalto 2000; Bischof 2008; Israel 1996; L'Engle 2014; Longabaugh 2001; Maisto 2001; Monti 2007; Moore 2011; Richmond 1995; Spirito 2011), in which the total duration was greater than 60 minutes and the number of sessions delivered to participants ranged from two to seven. The total duration of extended intervention sessions ranged from 60 minutes to 180 minutes..

Total treatment exposure

Total treatment exposure was calculated as a combination of the initial session plus any additional sessions. Treatment duration in the intervention arm ranged from less than five minutes (Babor 2006; Huas 2002) to 60 minutes (McIntosh 1997) of advice or counselling. The median duration was 25 minutes and IQR 7.5 to 30.0 minutes. Treatment duration in the control group was up to 10 minutes (Díez 2002; Rodríguez 2003). In the extended intervention conditions, the treatment exposures ranged from 65 minutes to 175 minutes .

Control group content

Five categories of control condition were reported. Participants received:

screening only; or

screening and assessment only; or

usual care ‐ this was usually not described further but was assumed to be care for the presenting condition or usual advice about alcohol consumption; or

general health advice or minimal advice about alcohol, comprising general health information or very limited alcohol‐related information which often included an instruction to cut down drinking; or

a leaflet with either general health and lifestyle advice or more specific information about the risks of hazardous alcohol consumption.

Some trials provided control participants with both usual care and a leaflet. One trial did not include a control condition but compared extended intervention with brief motivational intervention (Spirito 2011).

Efficacy/effectiveness scores

Efficacy/effectiveness scores ranged from 4.5 (Beckham 2007; Fleming 2004; Romelsjö 1989) to 12 (Lock 2006). The median was 8.5 and IQR 7 to 10.5 (Table 5).

2. Conversion factors for alcohol consumption and efficacy scores of trials.

| Trial | Reported units | Conversion factor | Source of conversion | Efficacy score | Treatment exposure1 |

| Aalto 2000 | g/week | 1 | NA | 10.5 | 45, 105 |

| Altisent 1997 | Units/week | 8 | Altisent 1997 | 8.5 | 20 |

| Babor 2006 | Drinks/week | 14 | Babor 2006 | 11 | 4 |

| Bazargan‐Hejazi 2005 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 9 | 17.5 |

| Beckham 2007 | Drinks/day | 11.671 x 7 | Miller 1991 | 4.5 | 52.5 |

| Beich 2007 | Drinks/week | 12 | Beich 2007 | 11 | 10 |

| Bernstein 2010 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 6.5 | 32.5 |

| Bischof 2008 | g/day | 7 | NA | 6.5 | 60 |

| Blow 2006 | Drinks/week | 13 | Blow 2009* | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Cherpitel 2009 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 9 | 17.5 |

| Córdoba 1998 | Units/week | 8 | Córdoba 1998 | 11 | 15 |

| Crawford 2004 | Units/week | 8 | Miller 1991 | 10.5 | 30 |

| Crawford 2010 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 8.5 | 30 |

| Curry 2003 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 8.5 | 22.5 |

| D'Amico 2008 | Basic statistics | NR | NA | 7.5 | 25 |

| D'Onofrio 2008 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 10.5 | 6.7 |

| D'Onofrio 2012 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 10.5 | 7;17 |

| Daeppen 2007 | Drinks/week | 10 | Daeppen 2007 | 7 | 15 |

| Dent 2008 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 11.5 | 5; 45 |

| Désy 2010 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 10.5 | 7.5 |

| Díez 2002 | Units/week | 8 | Díez 2002 | 10.5 | 10 |

| Drummond 2009 | Drinks previous 180 days | 8 x (7/180) | Drummond 2009 | 10.5 | 40; 200 |

| Drummond 2014 | Drinks/day | 8 x 7 | Drummond 2009 | 8 | 26 |

| Ettner 2014 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 11 | 108 |

| Fernández 1997 | Units/week | 10 | Miller 1991 | 7.5 | 10 |

| Field 2010 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 7.5 | 17.5 |

| Fleming 1997 | Drinks/week | 12 | Fleming 1997 | 10.5 | 40 |

| Fleming 1999 | Drinks/week | 12 | Fleming 1999 | 9 | 40 |

| Fleming 2004 | Drinks/month | 11.671 x (12/52) | Miller 1991 | 4.5 | 40 |

| Fleming 2010 | Drinks in previous 28 days | 11.671 x (7/28) | Miller 1991 | 8.5 | 42.5 |

| Heather 1987 | Units/month | 8 x (12/52) | Heather 1987 | 8.5 | 7.5 |

| Helstrom 2014 | Drinks/day | 11.671 x 7 | Miller 1991 | 7 | 37.5 |

| Huas 2002 | Units/week | 10 | Heather 2006 | 10 | 7.5 |

| Israel 1996 | Drinks/month | 13.456 x (7/28) | Miller 1991 | 7.5 | 150 |

| Kaner 2013 | Drinks/day | 8 x 7 | Kaner 2013 | 11 | 26 |

| Kunz 2004 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 6 | 37.5 |

| L'Engle 2014 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 8 | 180 |

| Lane 2008 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 10.5 | 7.5 |

| Lock 2006 | Drinks/week | 8 | Miller 1991 | 12 | 7.5 |

| Longabaugh 2001 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 6 | 50 |

| Maisto 2001 | Drinks/month | 17.01 x (7/30) | Miller 1991 | 5 | 13.5; 65 |

| McDevitt‐Murphy 2014 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 5.5 | 60 |

| McIntosh 1997 | Drinks/month | 13.456 x (12/52) | Miller 1991 | 10.5 | 60 |

| Mello 2008 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 7 | 45 |

| Mertens 2014 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 7.5 | 10 |

| Monti 2007 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 7.5 | 85 |

| Moore 2011 | Standard drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 9.5 | 83 |

| Noknoy 2010 | Drinks/week | 10 | Furtwaengler 2013 | 11 | 45 |

| Ockene 1999 | Drinks/week | 12.8 | Ockene 1999 | 10 | 7.5 |

| Richmond 1995 | Drinks/week | 10 | Richmond 1995 | 9.5 | 5, 57.5 |

| Rodríguez 2003 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 10.5 | 17.5 |

| Romelsjö 1989 | g/day | 1 x 7 | NA | 4.5 | 7.5 |

| Rubio 2010 | Drinks/week | 12.8 | Rubio 2010 | 9.5 | 32.5 |

| Schaus 2009 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 8 | 40 |

| Scott 1990 | Units/week | 8 | Miller 1991 | 11 | 10 |

| Segatto 2011 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 6 | 45 |

| Senft 1997 | Drinks/3 months | 11.671 x (4/52) | Miller 1991 | 9 | 16 |

| Seppa 1992 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 8.5 | 15 |

| Soderstrom 2007 | Drinks/last 90 days | 11.671 x (7/90) | Miller 1991 | 6.5 | 32.5 |

| Sommers 2006 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 7 | 40 |

| Sommers 2013 | Drinks/week | 11.671 | Miller 1991 | 7.5 | 40 |

| Spirito 2004 | Standard drinks/month | 11.671 x (12/52) | Miller 1991 | 7 | 40 |

| Spirito 2011 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 7.5 | 52.5 |

| Tait 2004 | alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 8 | 37.5 |

| Tomson 1998 | g/week | 1 | NA | 8.5 | 37.5 |

| Wallace 1988 | Units/week | 8 | Miller 1991 | 9.5 | 7.5 |

| Walton 2010 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 7 | 37 |

| Watson 2013 | Drinks/week | 8 | Watson 2013 | 9.5 | 20 |

| Woolard 2013 | Alcohol consumption | NR | NA | 5.5 | 72.5 |

* Blow 2009 is a report of Blow 2006. 1 Treatment exposure was calculated in minutes. Where two values appear, these are the durations of different intervention arms.

Abbreviations: NA: not applicable; NR: not reported.

Reporting of outcomes

The included studies reported many different measures of the primary outcome. We could not include 22 studies in meta‐analyses (Aalto 2000; Bazargan‐Hejazi 2005; Beckham 2007; Crawford 2010; D'Amico 2008; Dent 2008; Désy 2010; Díez 2002; Drummond 2009; Heather 1987; Kunz 2004; L'Engle 2014; Lane 2008; McDevitt‐Murphy 2014; Mello 2008; Mertens 2014; Noknoy 2010; Rodríguez 2003; Segatto 2011; Sommers 2006; Tait 2004; Woolard 2013), either because outcomes were not reported at 12 months, or outcome measures differed from those prespecified for this review (such as AUDIT score).

Quantity of alcohol consumed in a specified time period

Quantity of alcohol consumed in a specified time period (usually a week or a month) was reported in 51 studies that compared a brief intervention with minimal or no intervention. Of these, 27 studies reported quantity and corresponding standard deviation at 12 months (Altisent 1997; Beich 2007; Bernstein 2010; Blow 2006; Córdoba 1998; Crawford 2004; Daeppen 2007; D'Onofrio 2008; D'Onofrio 2012; Drummond 2014; Fleming 1997; Fleming 1999; Fleming 2004; Fleming 2010; Helstrom 2014; Kaner 2013; Lock 2006; Maisto 2001; Richmond 1995; Rubio 2010; Schaus 2009; Scott 1990; Senft 1997; Soderstrom 2007; Sommers 2013; Wallace 1988; Watson 2013). The authors of one study provided unpublished data on the corresponding standard deviation (Curry 2003). A further six studies reported the change between baseline and the end of follow‐up (change score) in the quantity of alcohol consumed in a specified time period and the corresponding standard deviation (Bischof 2008; Fernández 1997; Field 2010; Huas 2002; Ockene 1999; Romelsjö 1989). We included 34 studies in the primary meta‐analysis comparing the effects of a brief intervention with minimal or no intervention on the quantity of alcohol consumed per week, reported at 12 months follow‐up. Two studies reported the quantity of alcohol consumed per week both as assessed by structured interview and as reported on a self‐completed questionnaire; we used the interview data (Scott 1990; Wallace 1988).

Five studies reported the final values of the quantity of alcohol consumed in a specified time period at 12 months but without corresponding standard deviations (Babor 2006; Cherpitel 2009; Ettner 2014; McIntosh 1997; Spirito 2004). These studies could not be included in the primary meta‐analysis but were included in a sensitivity analysis with imputed standard deviations.

Six studies compared an extended intervention with minimal or no intervention and reported quantity of alcohol consumed at 12 months (Bischof 2008; Israel 1996; Maisto 2001; Monti 2007; Moore 2011; Richmond 1995). Three of these studies also compared an extended intervention to a brief intervention (Bischof 2008; Maisto 2001; Richmond 1995). One study, which compared an extended to a brief intervention, was included in a meta‐analysis with imputed standard deviations (Spirito 2011).

The units of alcohol used in each trial with the conversion factor used to convert to grams of alcohol are presented in Table 5.

Frequency of drinking (number of drinking sessions in a specified time period)

We included 15 trials that compared brief intervention to no or minimal intervention and reported frequency of drinking in terms of number of binge drinking occasions each week or each month at six or 12 months (Blow 2006; Daeppen 2007; D'Onofrio 2008; D'Onofrio 2012; Fleming 1997; Fleming 1999; Fleming 2004; Fleming 2010; Helstrom 2014; Longabaugh 2001; Ockene 1999; Rubio 2010; Spirito 2004; Soderstrom 2007; Schaus 2009). Two trials reported this outcome for extended versus no or minimal intervention (Longabaugh 2001; Monti 2007).

Frequency of drinking in terms of number of days drinking each week or each month was reported by 11 trials at 6 or 12 months (Bernstein 2010; Cherpitel 2009; Crawford 2004; Curry 2003; Daeppen 2007; Field 2010; Fleming 2010; Helstrom 2014; Maisto 2001; Senft 1997; Spirito 2004). Longabaugh 2001 reported the number of days drinking but the number of participants assessed was not reported. Two trials reported this outcome for extended versus no or minimal intervention (Maisto 2001; Monti 2007), and one for extended versus brief intervention (Maisto 2001).

Intensity of drinking (amount of alcohol consumed in a drinking session)

We included 10 trials that compared brief intervention to no or minimal intervention and reported intensity of alcohol consumption in terms of number of drinks per occasion at 12 months (Bernstein 2010; Cherpitel 2009; Crawford 2004; Curry 2003; Daeppen 2007; Helstrom 2014; Maisto 2001; Schaus 2009; Senft 1997; Spirito 2004). One trial reported this outcome for extended intervention versus no or minimal intervention and versus brief intervention (Maisto 2001).

Laboratory markers

We included seven studies that compared brief intervention to no or minimal intervention and reported gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT) (Aalto 2000; Beckham 2007; Noknoy 2010; Romelsjö 1989; Scott 1990; Tomson 1998; Wallace 1988). Romelsjö 1989 reported change scores whereas the other studies reported final values; only three studies reported at 12 months. One study reported this outcome for extended versus no or minimal intervention (Israel 1996).

One trial reported mean corpuscular volume (MCV) for this comparison (Seppa 1992).

Alcohol‐related harm

A measure of alcohol‐related consequences or harm (e.g. Drinker Inventory of Consequences ‐ DrInC; Alcohol Problems Quesionnaire ‐ APQ) was reported by 21 studies (Blow 2006; Cherpitel 2009; D'Onofrio 2012; Drummond 2009; Drummond 2014; Fleming 2010; Heather 1987; Helstrom 2014; Kaner 2013; Lane 2008; Longabaugh 2001; McDevitt‐Murphy 2014; McIntosh 1997; Mello 2008; Monti 2007; Romelsjö 1989; Schaus 2009; Spirito 2004; Walton 2010; Watson 2013; Woolard 2013).

Secondary outcomes