Summary

Aims

It has been well documented that angiotensin II type 1 (AT 1) receptor blockers (ARBs) are known to attenuate neural damage and the c‐Jun N‐terminal protein kinase 3 (JNK3) pathway and caspase‐3 signal are involved in neuronal cell death following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R). In this study, we first showed that losartan could protect neurons against cerebral I/R‐induced injury.

Methods

Cerebral ischemia model was induced by four‐vessel occlusion. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) against AT1 receptor and losartan were used to detect whether the AT1 receptor implicated in cerebral I/R. Immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting (IB) were used to detect the interactions between β‐arrestin‐2 and AT1/apoptosis signal‐regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)/MAP kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) signaling module following cerebral I/R.

Results

First, losartan decreased cerebral I/R‐induced neuronal death. Second, losartan depressed the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module. Third, losartan depressed the activation of c‐jun, JNK3, Bcl‐2, caspase‐3 and the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to cytoplasm.

Conclusion

Taken together, losartan could attenuate neural damage following the cerebral I/R via inhibiting the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module and depressing the activation of c‐jun, JNK3, and caspase‐3 and the release of cytochrome c.

Keywords: ASK1, AT1, Cerebral ischemia, JNK3, Losartan

Introduction

Drugs targeting G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) are used in a wide range of diseases. These strategies have successfully targeted dozens of GPCRs in the discovery of new therapeutic agents 1. GPCRs can activate parallel and sometimes distinct signals. The most general of these are mediated by β‐arrestin, which binds to activated receptor to desensitize G protein signaling, promote receptor internalization, and activate distinct signal transduction cascades that can be independent of G protein coupling 2, 3, 4, 5. In many cases, the physiological effect of the agonist activating a GPCR can be separated into β‐arrestin‐2 and G protein‐mediated components 6.

Neuronal apoptosis in the brain is involved in regulating synaptic plasticity and neural function 7, 8. Glutamate excitotoxicity, calcium overload, and free radical damage are the most important factors affecting the survival of neurons 9. ARBs are known to prevent the onset of stroke and to attenuate neural damage 10. Neuronal apoptosis is characterized by the release of cytochrome c and the activation of caspase‐3, which is the major executioner caspase in neurons 11. Interaction of β‐arrestin‐2 with c‐Src is involved in the early steps leading to the activation of MAP kinase pathways. β‐Arrestins also function as scaffold proteins to mediate assembly of multiprotein MAP kinase cascades such as those for extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) and JNK 4, 12. β‐Arrestin‐2 forms complexes with MAP kinase cascades to facilitate the activity of the ERK1/2 and JNK3 13, 14, 15. Agonist stimulation of AT1 can improve the recruitment of β‐arrestin‐2 and the activation of MAP kinase cascades to the AT1 11, 15, 16.

In the present study, we showed that compared with the ischemia group, losartan decreased 27.4% of neuronal loss in rat hippocampal CA1 region and could attenuate neural damage following the cerebral I/R via inhibiting the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module and depressing the activation of c‐jun, JNK3, and caspase‐3 and the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to cytoplasm.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model of Cerebral I/R

Animal care and procedures followed were in accordance with the Laboratory Animal Care Guidelines approved by Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences of Chinese Academy of Sciences. Permit numbers were SCXK (HU) 2007–0005 and SYXK (HU) 2008–0049. This study was approved by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality.

Adult male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats weighing 200–250 g were used in our study. At least six SD rats were used in each group. Transient cerebral ischemia was induced by four‐vessel occlusion (4‐VO) as described elsewhere 17. Briefly, SD rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (300 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection. Both vertebral arteries were occluded permanently by electrocautery. The following day, both carotid arteries were occluded with aneurysm clips to induce cerebral ischemia. After 15 min of occlusion, the aneurysm clips were removed for reperfusion. SD rats that lost their righting reflex and whose pupils were dilated and unresponsive to light were selected for the experiments. Rectal temperature was maintained at 36.5–37.5°C throughout the procedure. SD rats with seizures were discarded. Sham controls were performed using the same surgical exposure procedures, except that the arteries were not occluded.

Administration of Drug

Losartan (dissolved in 0.9% NaCl, 1, 3, 10 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) was administered to the SD rats by intraperitoneal injection 30 min before cerebral ischemia. One hundred micrograms of specific antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) against AT1 in 10 μL TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) was administered to the SD rats every 24 h for 3 days through cerebral ventricular injection (anteroposterior, 0.8 mm; lateral, 1.5 mm; depth, 3.5 mm from bregma). The same dose of missense ODNs and TE buffer were used as control. Following sequences of antisense of AT1 18 are used: forward primer: 5‐GGATGG TTCTCAGAGAGAGTACAT‐3 and reverse primer: 5‐CCTGCCCTCTTGT ACCTGTTG‐3.

Sample Preparation

Sprague–Dawley rats were decapitated immediately after different times of reperfusion, and then, the CA1 regions were isolated and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. The CA1 regions were homogenized in an ice‐cold homogenization buffer containing 50 mM 3‐N‐morpholino propanesulphonic acid (MOPS) (pH 7.4; Sigma Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO, USA), 100 mM KCl, 320 mM sucrose, 50 mM NaF, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM DTT, 1 mM ethylene glycol bis (2‐aminoethyl ether) tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4 (Sigma), 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 mM ß‐phosphoglycerol, 1 mM p‐nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP), 1 mM benzamidine, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 5 μg/mL each of leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin A. The homogenates were centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 100,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully removed, and 500 μL homogenization buffer containing 1% Triton X‐100 was added to the pellets, which were then exposed to ultrasound. Protein concentration was determined by the methods of Lowry et al.

Mitochondria Extraction

The CA1 regions were immediately isolated to prepare mitochondrial fractions. All procedures were conducted in a cold room. Nonfrozen brain tissues were used to prepare mitochondrial fractions. The CA1 regions were homogenized in 1:10 (w/v) ice‐cold homogenization buffer. The homogenates were centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellets were discarded, and supernatant was centrifuged at 17,000 g for 20 min at 4°C to obtain the cytosolic fraction in the supernatant and the crude mitochondrial fraction in the pellets. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Lowry. Samples were stored at −80°C.

Nuclei Extraction

The homogenates were centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant containing the cytosol part was collected, and protein concentrations were determined. Nuclear pellets were extracted with 20 mM 4‐(2‐Hydroxyethyl)‐1‐piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.9, 20% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and enzyme inhibitors for 30 min at 4°C with constant agitation. After centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, supernatant containing nuclear part was collected, and protein concentrations were determined. Samples were stored at −80°C and were thawed only once.

Immunoprecipitation

Tissue homogenates (400 μg of protein) were diluted 4‐fold with 50 mM HEPES buffer, (pH 7.4), containing 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 1%Triton X‐100, 0.5% NP‐40, and 1 mM each of EDTA, EGTA, PMSF, and Na3VO4. Samples were preincubated for 1 h with 20 μL protein A Sepharose CL‐4B (Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden) at 4°C and then centrifuged to remove proteins adhered nonspecifically to protein A. Supernatant was incubated with 2 μg β‐arrestin‐2 antibodies for 4 h or overnight at 4°C. Protein A was added to the tube for another 2 h of incubation. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 2 min at 4°C, and the pellets were washed with immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer for three times. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling at 100°C for 5 min in SDS–PAGE loading buffer and then isolated by centrifuge. The supernatant was used for immunoblotting analysis.

Immunoblot

Equal amounts of protein (60 μg/lane) were separated on polyacrylamide gels and then electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). After blocking for 3 h in Tris‐buffered saline with 0.1% Tween‐20 (TBST) and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies in TBST containing 3% BSA. Membranes were then washed and incubated with alkaline phosphatase–conjugated secondary antibodies in TBST for 2 h and developed using nitro blue tetrazolium/ 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl‐phosphate color substrate (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The densities of the bands on the membrane were scanned and analyzed with an image analyzer (Lab Works Software, UVP Upland, CA, USA).

Histology

Sprague–Dawley rats were perfusion‐fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) under anesthesia after 5 days of I/R. Brains were removed quickly and further fixed with the same fixation solution at 4°C overnight. Postfixed brains were embedded by paraffin, followed by preparation of coronal sections 5 μm thick using a microtome. Paraffin‐embedded brain sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated by ethanol at graded concentrations of 100–70% (v/v), followed by washing with water. The sections were stained with 0.1% (w/v) cresyl violet and were examined with light microscopy, and the number of surviving hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells per 1 mm length was counted as the neuronal density.

Antibody and Reagents

The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti‐p‐c‐jun antibody (sc‐16312), rabbit polyclonal anti‐Bcl‐2 antibody (sc‐492), goat polyclonal anti‐p‐Bcl‐2 antibody (sc‐16323), mouse monoclonal anti‐p‐JNKs antibody (sc‐6254), anti‐MKK4 antibody (sc‐964), goat polyclonal IgG anti‐β‐arrestin‐2 antibody (sc‐30938), rabbit IgG anti‐p‐ASK1 antibody (sc‐101633), mouse monoclonal anti‐ASK1 antibody (sc‐5294), goat polyclonal IgG anti‐AT1 (sc‐31181), and mouse monoclonal anti‐β‐actin antibody (sc‐130300) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anticytochrome c antibody (#4272), anti‐p‐MKK4 antibody (#9156), and rabbit polyclonal anti‐caspase‐3 antibody (#9661) were obtained from Cell Signaling Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti‐JNK3 antibody (06–749) was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Buffalo, NY, USA). The secondary antibodies used in our experiment were goat anti‐mouse IgG antibody, goat anti‐rabbit IgG antibody, and donkey anti‐goat IgG antibody, all obtained from Sigma. Nonspecific mouse or rabbit IgG antibody was obtained from Sigma.

Statistics

Values were expressed as mean ± SD and obtained from six independent SD rats. Statistical analysis of the results was carried out by one‐way analysis of the variance (anova), followed by the Duncan's new multiple range method or Newman–Keuls test. Differences of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

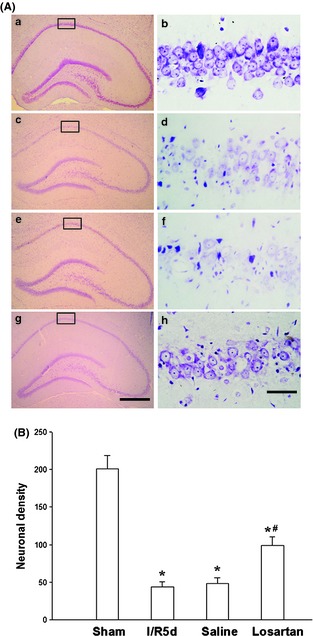

Losartan Decreased Cerebral I/R‐Induced Neuronal Death

To investigate whether pretreatment of losartan would decrease cerebral I/R‐induced neuronal cell death, SD rats were pretreated with losartan 3 mg/kg by intraperitoneal 30 min before cerebral ischemia. After 5 days of reperfusion, SD rats were perfusion‐fixed with paraformaldehyde, and cresyl violet staining was used to examine the survival of the pyramidal neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region. Results from histology indicated that normal CA1 pyramidal neurons showed round and palely stained nuclei (Figure 1Aa,b), whereas the shrunken cells with pyknotic nuclei after reperfusion were counted as dead cells (Figure 1Ac,d). Administration of losartan 30 min before cerebral ischemia significantly decreased neuronal degeneration (Figure 1Ag,h); at the same time, as a control, saline did not show any protection against the degeneration induced by 5 days of cerebral I/R (Figure 1Ae,f). Neuronal densities of the sham group, cerebral I/R control group, saline control group, and losartan group were 201.0 ± 11.7, 43.5 ± 7.2, 48.1 ± 8.3, and 98.6 ± 11.5, respectively (Figure 1B); compared with the cerebral I/R group, losartan decreases 27.4% of neuronal loss in rat hippocampal CA1 region.

Figure 1.

Losartan decreased cerebral I/R‐induced neuronal death. (A) Cresyl violet staining was performed on the sections from the hippocampus in sham (a, b), and rats were subjected to 5 days of reperfusion after 15 min of cerebral ischemia (c, d), administration of the saline as control (e, f), and 3 mg/kg losartan (g, h) before cerebral ischemia. Boxed areas in left column were shown at higher magnification in right column. a, c, e, g: ×40; b, d, f, h: ×400. Scale bar = 200 μm in g (applies to a, c, e, g) 10 μm in h (applies to b, d, f, h). (B) Data were expressed as mean ± SD from six separate experiments. *P < 0.05 as compared with sham group; #P < 0.05 as compared with I/R control group.

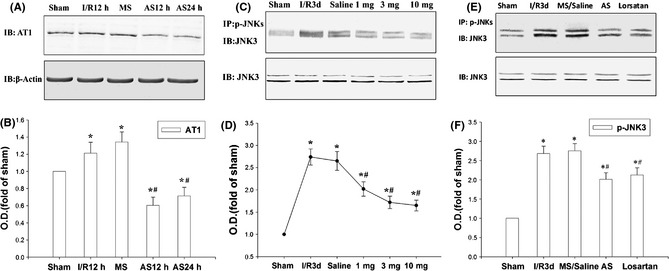

Losartan Depressed the Activation of JNK3 via AT1 Receptor

To investigate whether AT1 receptor was involved in the cerebral I/R, the AT1 receptor antisense ODNs (AS) were used to reduce the expression of AT1 receptor. Results from Western blot showed that the expression of AT1 receptor on the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus was significantly upregulated following 12 h of cerebral I/R, but the AT1 receptor antisense ODNs (AS) were notably depressed following 12 and 24 h of cerebral I/R‐induced upregulation of AT1 receptor (Figure 2A,B). Three different dosages of losartan were administrated to SD rats to investigate the effect of AT1 receptor on the activation of JNK3. Because JNK3 was selectively phosphorylated in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus, the CA1 region was isolated for further examination 19. The results showed that 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg of losartan all depressed 3 days of cerebral I/R‐induced phosphorylation of JNK3 (Figure 2C,D); 3 mg/kg losartan is the most effective dose. The results of IP revealed that the phosphorylation of JNK3 (Figure 1B) after 3 days of cerebral I/R is suppressed by the application of losartan (3 mg/kg) and the AT1 receptor antisense ODNs.

Figure 2.

Losartan depresses the phosphorylation of JNK3 via AT1 receptor. (A, B) Effects of pretreatment with AT1 antisense (AS) or missense (MS) oligodeoxynucleotides on the expression of AT1 induced by 12 and 24 h of I/R in rat hippocampus CA1. (C, D) The immunoprecipitation (IP) and IB results showed that losartan depressed 3 days of I/R‐induced phosphorylation of JNK3. (E, F) AS and losartan 3 mg/kg repressed the 3 days of cerebral I/R‐induced phosphorylation of JNK3. β‐Actin was blotted as controls. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from four separate experiments. *P < 0.05 as compared with sham group; #P < 0.05 as compared with cerebral I/R control group. O.D., optical density.

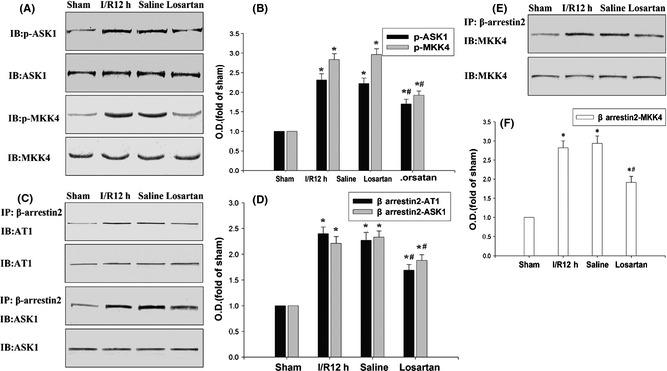

Losartan Depressed the β‐Arrestin‐2‐Assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 Signaling Module

Previous studies indicate that the β‐arrestin‐2 is responsible for high‐level JNK3 phosphorylation via β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled ASK1/MKK4/JNK3 signaling module 20. So we hypothesize that losartan could inhibit the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module and subsequently decrease the phosphorylation of JNK3 as well as neuronal cell death following cerebral I/R.

After 12 h of reperfusion, the phosphorylation of ASK1 and MKK4 was examined. IP and immunoblotting results showed that the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module reached a high level at 12 h following cerebral I/R (Figure 3A,B). Losartan 3 mg/kg obviously depressed the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module and the phosphorylation of ASK1 and MKK4 (Figure 3A,B). Meanwhile, the protein levels were not altered, and the saline control did not affect the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module and the phosphorylation of ASK1 and MKK4.

Figure 3.

Losartan depressed the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/ MKK4 signaling module. (A–D) The immunoprecipitation (IP) and IB results showed that losartan obviously depressed the 12 h of cerebral I/R‐induced β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1, ASK1, MKK4 signaling module. (E, F) IB results showed that losartan depressed the 12 h of cerebral I/R‐induced phosphorylation of ASK1 and MKK4. β‐Actin, ASK1, and MKK4 were blotted as controls. Data were expressed as mean ± SD from four separate experiments. *P < 0.05 as compared with sham group; #P < 0.05 as compared with cerebral I/R control group. O.D., optical density.

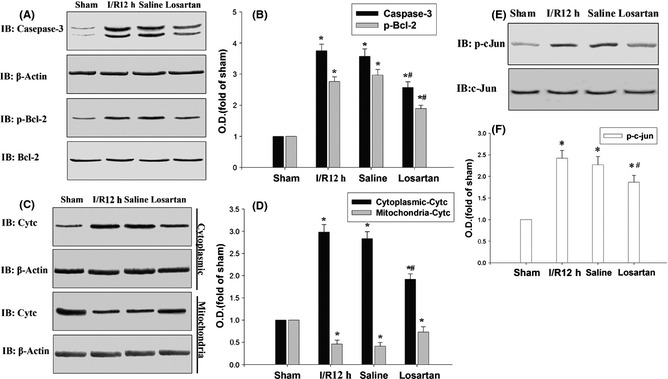

Losartan Depressed the Activation of C‐Jun, Bcl‐2, Caspase‐3 and the Release of Cytochrome c

To investigate whether losartan inhibited the activation of c‐jun, nuclear extracts from the CA1 regions were subjected to immunoblotting analysis with anti‐p‐c‐jun antibody. As shown in Figure 4A–D, c‐jun and Bcl‐2 were activated after reperfusion and reached a high level at 12 h following cerebral I/R; losartan prevented the increased c‐jun and Bcl‐2 activation following 12 h of cerebral I/R.

Figure 4.

Losartan depressed the activation of c‐jun, Bcl‐2 caspase‐3 and the release of cytochrome c. (A–D) The IB results showed that losartan depressed 12 h of cerebral I/R‐induced phosphorylation of c‐jun, Bcl‐2, and the activation of caspase‐3. (E, F) The IB results showed that losartan depressed 12 h of cerebral I/R‐induced cytochrome c releasing from mitochondria to cytosolic. β‐Actin, c‐jun, and Bcl‐2 were blotted as controls. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from four separate experiments. *P < 0.05 as compared with sham group; #P < 0.05 as compared with I/R control group. O.D., optical density.

In cerebral I/R studies, caspase‐3 showed a key role in neuronal death following cerebral I/R. A previous study demonstrated that the activation of caspase‐3 should be cleaved subunits of caspase‐3 21. Activation of caspase‐3 was confirmed following 12 h of cerebral I/R by the methods of immunoblotting with antibodies recognizing the activated fragments for caspase‐3, and losartan prevented the increased caspase‐3 activation following 12 h of cerebral I/R (Figure 4A,B).

To detect whether the mitochondrial protein cytochrome c was released from mitochondria 22, we examined the cytochrome c level in the cytoplasm and mitochondria fraction using anticytochrome c oxidase subunit IV, β‐actin as control. A high level of cytochrome c was detected in the cerebral I/R control group and saline control group, but 3 mg/kg of losartan obviously depressed the 12 h of cerebral I/R‐induced high level of cytochrome c in the cytoplasm. In contrast, a low level of cytochrome c was detected in the cerebral I/R control group and saline control group in the mitochondria and 3 mg/kg of losartan obviously depressed the 12 h of cerebral I/R‐induced cytochrome c released from the mitochondria.

Discussion

The present study investigated the role and possible mechanisms of losartan on cerebral I/R injury by a 4‐VO rat model. Our results showed that losartan could attenuate neural damage following the cerebral I/R via inhibiting the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module.

It is reported that ischemia‐induced brain damage is enhanced in human renin and angiotensinogen double‐transgenic mice 23. ARBs have been demonstrated to significantly improve the neurological outcome and reduce the infarct volume after experimental focal cerebral ischemia in normal rats 24, 25. Meanwhile, clinical studies also reveal the protective role of ARBs in cerebral ischemia injury and the utility of this therapy for stroke 26, 27. Although it is well shown that losartan protected against cerebral ischemic injury by reducing infarct volume and promoting functional recovery, which is associated with the activation of eNOS through the PI3K‐Akt signaling pathway 28, the whole mechanism by which ARBs protect against cerebral I/R injury is still unclear. Here, our results indicated that AT1 receptor was involved in cerebral I/R injury via upregulating phosphorylation of ASK1, MKK4, and JNK3.

In cerebral I/R injury, glutamate excitotoxicity, calcium overload, and free radical damage are the most important factors affecting the survival of neurons 9. Recent results show that the neuronal cell death resulting from ischemic events can be associated with abnormal activity of MAPKK signaling pathway 29, 30. So it is possible that suppressing the overactivation of MAPKKK signaling pathway can effectively protect neurons against cerebral I/R damage. The β‐arrestin‐2 scaffold protein supported protein kinase C–independent ERK1/2 activation and JNK3 activation by binding to its nonconserved N‐terminus to AT1 receptor 15, 31. The increased ASK1 expression induces apoptotic cell death after cerebral I/R; the ASK1‐siRNA attenuates upregulation of ASK1, which was followed by the reduction in infarction after cerebral I/R 32. Treatment of an inhibitor of JNKs SP600125 or N‐acetylcysteine (NAC) could decrease the activation of ASK1 during cerebral I/R and depressed the activation of JNK and c‐Jun 33. Here, our results showed losartan obviously depressed the high level of the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module and the phosphorylation of ASK1 and MKK4 following the cerebral I/R.

JNK3 phosphorylates Bcl‐2 in several conditions and the phosphorylation of Bcl‐2 decreases the protective effects of Bcl‐2 against cell death, as well as the phosphorylation of c‐jun following 12 h of cerebral I/R 22, 34. The mitochondrial protein cytochrome c was released from mitochondria to cytoplasm following cerebral I/R 22, 35. The capital role of caspase‐3 following the cerebral I/R‐induced apoptosis is very important. Increased caspase‐3 protease activity in the hippocampal CA1 region may be responsible for the delayed neuronal cell death after cerebral I/R 22, 36.

Our results showed that losartan depressed the activation of c‐jun, Bcl‐2, and caspase‐3 and inhibited the mitochondrial protein cytochrome c release from mitochondria to the cytoplasm following 12 h of cerebral I/R. Taken together, the results suggested that losartan could attenuate neural damage following the cerebral I/R via inhibiting the β‐arrestin‐2‐assembled AT1/ASK1/MKK4 signaling module and depressing the activation of c‐jun, JNK3, and caspase‐3 and the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to cytoplasm.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171014), the project of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (09DZ1950400), and the youth projects of National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100783). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Hopkins AL, Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2002;1:727–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reiter E, Lefkowitz RJ. GRKs and beta‐arrestins: roles in receptor silencing, trafficking and signaling. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2006;17:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Beta‐arrestins and cell signaling. Annu Rev Physiol 2007;69:483–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DeFea KA, Zalevsky J, Thoma MS, Dery O, Mullins RD, Bunnett NW. Beta‐arrestin‐dependent endocytosis of proteinase‐activated receptor 2 is required for intracellular targeting of activated ERK1/2. J Cell Biol 2000;148:1267–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Proceedings of the 55th International Symposium on Crop Protection. Gent, May 6, 2003. Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci 2003;68:455–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmid CL, Bohn LM. Physiological and pharmacological implications of beta‐arrestin regulation. Pharmacol Ther 2009;121:285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buss RR, Oppenheim RW. Role of programmed cell death in normal neuronal development and function. Anat Sci Int 2004;79:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Zio D, Giunta L, Corvaro M, Ferraro E, Cecconi F. Expanding roles of programmed cell death in mammalian neurodevelopment. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2005;16:281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi DW. Cerebral hypoxia: some new approaches and unanswered questions. J Neurosci 1990;10:2493–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsukuda K, Mogi M, Iwanami J, et al. Irbesartan attenuates ischemic brain damage by inhibition of MCP‐1/CCR2 signaling pathway beyond AT receptor blockade. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011;409:275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baydas G, Reiter RJ, Akbulut M, Tuzcu M, Tamer S. Melatonin inhibits neural apoptosis induced by homocysteine in hippocampus of rats via inhibition of cytochrome c translocation and caspase‐3 activation and by regulating pro‐ and anti‐apoptotic protein levels. Neuroscience 2005;135:879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 2000;103:239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scott MG, Le Rouzic E, Perianin A, et al. Differential nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of beta‐arrestins. Characterization of a leucine‐rich nuclear export signal in beta‐arrestin2. J Biol Chem 2002;277:37693–37701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang P, Wu Y, Ge X, Ma L, Pei G. Subcellular localization of beta‐arrestins is determined by their intact N domain and the nuclear export signal at the C terminus. J Biol Chem 2003;278:11648–11653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee MH, El‐Shewy HM, Luttrell DK, Luttrell LM. Role of beta‐arrestin‐mediated desensitization and signaling in the control of angiotensin AT1a receptor‐stimulated transcription. J Biol Chem 2008;283:2088–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tanoue T, Nishida E. Molecular recognitions in the MAP kinase cascades. Cell Signal 2003;15:455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB. A new model of bilateral hemispheric ischemia in the unanesthetized rat. Stroke 1979;10:267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kathmann M, Bauer U, Schlicker E. CB1 receptor density and CB1 receptor‐mediated functional effects in rat hippocampus are decreased by an intracerebroventricularly administered antisense oligodeoxynucleotide. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1999;360:421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gu Z, Jiang Q, Zhang G. c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase activation in hippocampal CA1 region was involved in ischemic injury. Neuroreport 2001;12:897–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller WE, McDonald PH, Cai SF, Field ME, Davis RJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Identification of a motif in the carboxyl terminus of beta ‐arrestin2 responsible for activation of JNK3. J Biol Chem 2001;276:27770–27777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang QG, Wang RM, Yin XH, Pan J, Xu TL, Zhang GY. Knock‐down of POSH expression is neuroprotective through down‐regulating activation of the MLK3‐MKK4‐JNK pathway following cerebral ischaemia in the rat hippocampal CA1 subfield. J Neurochem 2005;95:784–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu SQ, Zhu J, Pei DS, et al. Overexpression of the PDZ1 domain of PSD‐95 diminishes ischemic brain injury via inhibition of the GluR6.PSD‐95.MLK3 pathway. J Neurosci Res 2009;87:3626–3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen S, Li G, Zhang W, et al. Ischemia‐induced brain damage is enhanced in human renin and angiotensinogen double‐transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009;297:R1526–R1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dai WJ, Funk A, Herdegen T, Unger T, Culman J. Blockade of central angiotensin AT(1) receptors improves neurological outcome and reduces expression of AP‐1 transcription factors after focal brain ischemia in rats. Stroke 1999;30:2391–2398; discussion 98‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu H, Kitazato KT, Uno M, et al. Protective mechanisms of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker candesartan against cerebral ischemia: in‐vivo and in‐vitro studies. J Hypertens 2008;26:1435–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lithell H, Hansson L, Skoog I, et al. The Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE): principal results of a randomized double‐blind intervention trial. J Hypertens 2003;21:875–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schrader J, Luders S, Kulschewski A, et al. The ACCESS study: evaluation of acute candesartan cilexetil therapy in stroke survivors. Stroke 2003;34:1699–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu H, Liu X, Wei X, et al. Losartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, ameliorates cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury via PI3K/Akt‐mediated eNOS phosphorylation. Brain Res Bull 2012;89:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scarpidis U, Madnani D, Shoemaker C, et al. Arrest of apoptosis in auditory neurons: implications for sensorineural preservation in cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol 2003;24:409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bazenet CE, Mota MA, Rubin LL. The small GTP‐binding protein Cdc42 is required for nerve growth factor withdrawal‐induced neuronal death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:3984–3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guo C, Whitmarsh AJ. The beta‐arrestin‐2 scaffold protein promotes c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase‐3 activation by binding to its nonconserved N terminus. J Biol Chem 2008;283:15903–15911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim HW, Cho KJ, Lee SK, Kim GW. Apoptosis signal‐regulating kinase 1 (Ask1) targeted small interfering RNA on ischemic neuronal cell death. Brain Res 2011;1412:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Niu YL, Li C, Zhang GY. Blocking Daxx trafficking attenuates neuronal cell death following ischemia/reperfusion in rat hippocampus CA1 region. Arch Biochem Biophys 2011;515:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maundrell K, Antonsson B, Magnenat E, et al. Bcl‐2 undergoes phosphorylation by c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase/stress‐activated protein kinases in the presence of the constitutively active GTP‐binding protein Rac1. J Biol Chem 1997;12:180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Szczepanek K, Chen Q, Larner AC, Lesnefsky EJ. Cytoprotection by the modulation of mitochondrial electron transport chain: The emerging role of mitochondrial STAT3. Mitochondrion 2011;12:180–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zheng Z, Zhao H, Steinberg GK, Yenari MA. Cellular and molecular events underlying ischemia‐induced neuronal apoptosis. Drug News Perspect 2003;16:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]