Abstract

Background

Corticosteroids are often preferred over enteral nutrition (EN) as induction therapy for Crohn's disease (CD). Prior meta‐analyses suggest that corticosteroids are superior to EN for induction of remission in CD. Treatment failures in EN trials are often due to poor compliance, with dropouts frequently due to poor acceptance of a nasogastric tube and unpalatable formulations. This systematic review is an update of a previously published Cochrane review.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of exclusive EN as primary therapy to induce remission in CD and to examine the importance of formula composition on effectiveness.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase and CENTRAL from inception to 5 July 2017. We also searched references of retrieved articles and conference abstracts.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials involving patients with active CD were considered for inclusion. Studies comparing one type of EN to another type of EN or conventional corticosteroids were selected for review.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted independently by at least two authors. The primary outcome was clinical remission. Secondary outcomes included adverse events, serious adverse events and withdrawal due to adverse events. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). A random‐effects model was used to pool data. We performed intention‐to‐treat and per‐protocol analyses for the primary outcome. Heterogeneity was explored using the Chi2 and I2 statistics. The studies were separated into two comparisons: one EN formulation compared to another EN formulation and EN compared to corticosteroids. Subgroup analyses were based on formula composition and age. Sensitivity analyses included abstract publications and poor quality studies. We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess study quality. We used the GRADE criteria to assess the overall quality of the evidence supporting the primary outcome and selected secondary outcomes.

Main results

Twenty‐seven studies (1,011 participants) were included. Three studies were rated as low risk of bias. Seven studies were rated as high risk of bias and 17 were rated as unclear risk of bias due to insufficient information. Seventeen trials compared different formulations of EN, 13 studies compared one or more elemental formulas to a non‐elemental formula, three studies compared EN diets of similar protein composition but different fat composition, and one study compared non‐elemental diets differing in glutamine enrichment. Meta‐analysis of 11 trials (378 participants) demonstrated no difference in remission rates. Sixty‐four per cent (134/210) of patients in the elemental group achieved remission compared to 62% (105/168) of patients in the non‐elemental group (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.18; GRADE very low quality). A per‐protocol analysis (346 participants) produced similar results (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.18). Subgroup analyses performed to evaluate the different types of elemental and non‐elemental diets (elemental, semi‐elemental and polymeric) showed no differences in remission rates. An analysis of 7 trials including 209 patients treated with EN formulas of differing fat content (low fat: < 20 g/1000 kCal versus high fat: > 20 g/1000 kCal) demonstrated no difference in remission rates (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.26). Very low fat content (< 3 g/1000 kCal) and very low long chain triglycerides demonstrated higher remission rates than higher content EN formulas. There was no difference between elemental and non‐elemental diets in adverse event rates (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.60; GRADE very low quality), or withdrawals due to adverse events (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.09; GRADE very low quality). Common adverse events included nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and bloating.

Ten trials compared EN to steroid therapy. Meta‐analysis of eight trials (223 participants) demonstrated no difference in remission rates between EN and steroids. Fifty per cent (111/223) of patients in the EN group achieved remission compared to 72% (133/186) of patients in the steroid group (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.03; GRADE very low quality). Subgroup analysis by age showed a difference in remission rates for adults but not for children. In adults 45% (87/194) of EN patients achieved remission compared to 73% (116/158) of steroid patients (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.82; GRADE very low quality). In children, 83% (24/29) of EN patients achieved remission compared to 61% (17/28) of steroid patients (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.97; GRADE very low quality). A per‐protocol analysis produced similar results (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.14). The per‐protocol subgroup analysis showed a difference in remission rates for both adults (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.95) and children (RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.97). There was no difference in adverse event rates (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.62 to 3.11; GRADE very low quality). However, patients on EN were more likely to withdraw due to adverse events than those on steroid therapy (RR 2.95, 95% CI 1.02 to 8.48; GRADE very low quality). Common adverse events reported in the EN group included heartburn, flatulence, diarrhea and vomiting, and for steroid therapy acne, moon facies, hyperglycemia, muscle weakness and hypoglycemia. The most common reason for withdrawal was inability to tolerate the EN diet.

Authors' conclusions

Very low quality evidence suggests that corticosteroid therapy may be more effective than EN for induction of clinical remission in adults with active CD. Very low quality evidence also suggests that EN may be more effective than steroids for induction of remission in children with active CD. Protein composition does not appear to influence the effectiveness of EN for the treatment of active CD. EN should be considered in pediatric CD patients or in adult patients who can comply with nasogastric tube feeding or perceive the formulations to be palatable, or when steroid side effects are not tolerated or better avoided. Further research is required to confirm the superiority of corticosteroids over EN in adults. Further research is required to confirm the benefit of EN in children. More effort from industry should be taken to develop palatable polymeric formulations that can be delivered without use of a nasogastric tube as this may lead to increased patient adherence with this therapy

Plain language summary

Enteral nutritional therapy for treatment of active Crohn's disease

What is Crohn's disease?

Crohn's disease is a long‐term inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, occurring anywhere from mouth to anus. Common symptoms of this condition include abdominal pain, diarrhea and weight loss. When Crohn's disease patients are experiencing symptoms, it is characterized to be 'active' disease. When the symptoms stop, it is called 'remission'.

What is enteral nutrition?

Enteral nutrition is a feeding method where all of a person's daily caloric intake is delivered using the GI tract. An example of this is nasogastric tube feeding, where a tube is inserted through a person's nose to deliver their daily nutritional requirements in liquid form. Enteral nutrition can be a form of nutritional therapy for Crohn's disease patients. Enteral nutrition is categorized into elemental and non‐elemental (semi‐elemental and polymeric) diets. Elemental diets come from amino‐acid sources, whereas non‐elemental diets come from oligopeptide or whole protein sources.

What are corticosteroids?

Corticosteroids are an effective treatment option for active Crohn's disease. These drugs that are taken by mouth and work as immunosuppressants.

What did the researchers investigate?

The researchers studied whether enteral nutrition is better than steroid therapy at producing remission in Crohn's disease patients. In addition, the investigators looked to see if one type of enteral nutrition was better than another (e.g. elemental vs.non‐elemental) at producing remission in Crohn's disease.

What did the researchers find?

The researchers found twenty‐seven studies (1,011 participants) that fulfilled the search criteria. Eleven of these studies, which included 378 patients, compared elemental to non‐elemental diets at producing remission in Crohn's disease. Eight studies, which included 352 patients, investigated enteral nutrition compared to steroid therapy at inducing remission in Crohn's disease. The researchers searched the medical literature extensively up to July 5, 2017.

Very low quality evidence suggests that steroids may be more effective than enteral nutrition for induction of remission in adults with active Crohn's disease. Very low quality evidence also suggests that enteral nutrition may be more effective than steroids for induction of remission in children with active Crohn's disease. There was no difference in remission rates between elemental and non‐elemental diets. An increase in side effects was not seen with elemental diets compared to non‐elemental diets, nor with enteral nutrition compared to steroids. Common side effects experienced with enteral nutrition included vomiting, diarrhea, heartburn and flatulence . Common side effects associated with steroid use included acne, moon facies, muscle weakness, hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) and hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) . Patients on enteral nutrition were more likely to withdraw from the study due to side effects than those on steroids. The most common reason for study withdrawal was inability to tolerate the taste of the enteral nutrition diet. Enteral nutrition should be considered in pediatric Crohn's patients or in adult patients who can comply with nasogastric tube feeding or perceive the formulations to be palatable, or when steroid side effects are not tolerated or better avoided. Further research is required to confirm the superiority of corticosteroids over EN in adults. Further research is required to confirm the benefit of EN in children. More effort from industry should be taken to develop palatable polymeric formulations that can be delivered without use of a nasogastric tube as this may lead to increased patient compliance with this therapy.

Summary of findings

Background

Elemental diets were first used in Crohn's disease to provide preoperative nutritional support. Primary therapeutic efficacy was suspected in an uncontrolled study where patients awaiting surgery appeared to experience improvement in the clinical activity of their inflammatory bowel disease as well as in their nutritional status (Voitk 1973). There is now a vast experience and literature supporting the use of nutritional therapy in Crohn's disease but the mechanism of action and ideal formulation are still unknown. Nutritional therapy is classified by the nitrogen source derived from the amino acid or protein component of the formula. Elemental diets are created by mixing of single amino acids and are entirely antigen free. Oligopeptide or semi‐elemental diets are made by protein hydrolysis and have a mean peptide chain length of four or five amino acids which is too short for antigen recognition or presentation. Polymeric diets contain whole protein from sources such as milk, meat, egg or soy. Polymeric diets can be classified more simply as elemental (amino acid‐based), semi‐elemental (oligopeptide) and polymeric (whole protein) diets.

The use of enteral nutritional therapy to treat active Crohn's disease has been shown to be less effective than conventional corticosteroid therapy in three meta‐analyses published in the mid nineties (Fernandez‐Banares 1995; Griffiths 1995; Messori 1996). This was demonstrated again in previous Cochrane meta‐analyses (Zachos 2001; Zachos 2007), despite differences in criteria for study inclusion. However, in some of the trials evaluating enteral nutrition versus steroids, the steroid‐treated patients sometimes received additional concurrent drug therapy such as sulfasalazine or antibiotics. Exclusion of such trials (Lochs 1991; Malchow 1990), resulted in a lack of superiority of steroids over enteral nutritional therapy, but the sample size was also markedly reduced. One further meta‐analysis showed no difference in effectiveness between enteral nutrition and corticosteroid therapy for the treatment of acute Crohn's disease in children (Heuschkel 2000). This apparent discrepancy may stem from differences involving the study populations (e.g. ages, disease activity, disease duration), interventions (e.g. with or without concurrent 5‐ASA preparations), outcome assessments (disease activity measures), methodology (e.g. sample size, blinding, randomization), and patient compliance (adults may not readily accept nasogastric feeding).

Regardless of whether enteral nutrition therapy is equal or slightly inferior in effectiveness to corticosteroids, its use deserves consideration in both the adult and pediatric population. There is a growing resistance to the frequent use of corticosteroids in children with Crohn's disease due to numerous adverse effects, particularly on growth, bone mineral density and body image. In addition, corticosteroids are not effective therapies for achieving mucosal healing (Landi 1992; Modigliani 1990). Therefore, in some parts of the world such as in Europe, enteral nutrition is presented as first line therapy based on good efficacy data for induction of remission as well as beneficial effects on growth, rapid nutritional restitution, fewer adverse effects and improved quality of life (Afzal 2004). The argument for the use of enteral nutrition as primary therapy for Crohn's disease is further supported by evidence of mucosal healing (Afzal 2004; Fell 2000; Yamamoto 2007), and one study demonstrated significantly higher rates of mucosal healing compared to patients receiving corticosteroids (Berni Canani 2006).

Enteral nutrition as a primary therapy for induction of Crohn's disease is often overlooked as a treatment option in the United States. Despite the evidence supporting its role as a means for induction of remission, only 4% of American gastroenterologists use it regularly to manage mild to moderately active pediatric Crohn's disease (Levine 2003). Reasons for lack of uptake among physicians include concerns about poor acceptability of nasogastric tubes by patients, palatability of formulations, and lack of compliance with a restrictive dietary intervention (Kansal 2013). However, palatable polymeric formulations have been produced recently and oral administration of these formulations has been demonstrated to be as efficacious as feeds delivered by the nasogastric route (Rubio 2011). The ability to use a palatable oral polymeric formulation as a means of induction therapy helps to overcome some of the prior limitations of enteral nutrition treatment. This systematic review and meta‐analysis is an update of a previously published Cochrane review (Zachos 2001; Zachos 2007). Prior versions of this systematic review and meta‐analyses were performed using an intention‐to‐treat analysis, which includes treatment failures who withdrew due to poor acceptance of enteral feeding (Zachos 2001; Zachos 2007). This updated meta‐analysis therefore aimed to also perform a per‐protocol analysis to compare enteral feeding versus corticosteroids for treatment of active Crohn's disease, but exclude treatment failures that occurred on the basis of poor palatability or lack of acceptance of a nasogastric tube, since these limitations may be overcome with use of palatable oral polymeric formulations. This review also provides an update on the existing effectiveness and safety data for both corticosteroids versus enteral nutrition, and for elemental versus non‐elemental feeds (i.e. one form of enteral nutrition versus another) for induction of remission of active Crohn's disease.

Objectives

The primary objectives were to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of exclusive enteral nutrition as primary therapy to induce remission in Crohn's disease and to examine the importance of formula composition on effectiveness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials published in any language were considered for inclusion in the review. Trials published in abstract form were included if full details of the protocol and results could be obtained from the authors.

Types of participants

Patients with active Crohn's disease defined by a clinical disease activity index were considered for inclusion.

Types of interventions

Studies that compared the exclusive administration of one type of enteral nutrition (i.e. elemental, semi‐elemental, or polymeric) to another type of enteral nutrition or conventional corticosteroids were considered for inclusion. We excluded the following types of studies: trials allowing oral intake other than clear liquids; trials allowing co‐intervention with antibiotics, or corticosteroids in high or recently increased doses among patients allocated to enteral nutrition; and trials not defining disease activity and remission.

Types of outcome measures

The studies used one of various measures to assess remission: the Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI), van Hees Index, the simple Crohn's Disease Index (or Harvey‐Bradshaw simple CDI), the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Index (IOIBD) and the Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index (PCDAI). The definition of remission can vary across studies using the same assessment scale. Thus, the primary outcome was the number of patients achieving remission, as defined by each individual study, and expressed as a percentage of the patients randomized (intention‐to‐treat analysis). Additional analysis was performed on a per‐protocol basis, excluding patients who withdrew due to lack of acceptability of a nasogastric tube for feeding or palatability of the enteral feed. Patients who withdrew for other reasons were still counted as treatment failures. Secondary outcomes included adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events and serious adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched MEDLINE (Ovid) Embase (Ovid) and the Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) from inception to 5 July 2017. The search strategy is reported in Appendix 1.

In addition, a manual search of American Journal of Gastroenterology, Gut, Gastroenterology, Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, and Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition from January 1995 to July 2017 was conducted and included abstracts submitted to major gastroenterologic meetings. Additional citations were sought using references from applicable systematic reviews and studies retrieved from the computerized and manual searches.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection: The studies (and abstracts when available) retrieved by the search strategy were independently reviewed by at least two investigators (NN, AD or DZ). Study eligibility was determined by discussion and consensus.

Quality Assessment: The quality of included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011). We assessed the following domains: methods used for randomization and allocation concealment (selection bias); blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors (performance and detection bias); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); selective reporting of study outcomes and other potential sources of bias. Each potential source of bias was rated as low, high or unclear risk of bias. If an item could not be evaluated due to missing information, it was rated as an unclear risk of bias. The quality of studies was independently assessed by at least two investigators (NN, AD or DZ) with disagreements settled by consensus with all authors. Studies with at least one domain at high risk of bias were excluded on sensitivity analyses.

The GRADE approach was used to evaluate the overall quality of evidence supporting the primary and selected secondary outcomes (Guyatt 2008; Schunemann 2011). The GRADE approach allows overall appraisal of the quality of evidence such that one can determine confidence in how likely the effect estimate reflects the item of interest. Randomized trials start as high quality of evidence, but can be downgraded due to risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, unexplained heterogeneity, imprecision, and publication bias. After consideration of these factors, the overall quality of the evidence was graded as one of:

‐ High ‐ further research is unlikely to change confidence in the estimate of effect;

‐ Moderate ‐ further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate;

‐ Low ‐ further research is very likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; or

‐ Very low ‐ any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Data extraction: Data extraction forms were developed and data were independently extracted from eligible studies by at least two investigators (NN, AD or DZ). Rereading and discussion resolved any discrepancies in data recorded on the extraction forms. The extracted data included baseline characteristics of patients (i.e. number of patients randomized, age, sex, anatomic distribution of disease, duration of diagnosed disease, disease activity score, and co‐intervention if any); details of formulation and therapeutic administration of enteral nutrition or corticosteroid therapy; details on dropouts/withdrawals; and outcome assessment (i.e. time of assessment, clinical disease activity index used, definition of clinical remission, and remission rates according to the total number of patients randomized). A separate per‐protocol assessment was conducted by removing patients from the analysis who could not tolerate enteral feeding due to palatability of the formulation or non‐acceptance of a nasogastric tube.

Statistical analyses: Data were analyzed using Review Manager (RevMan 5.3.5, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Data were analyzed on an intention‐to‐treat and a per‐protocol basis. For the dichotomous outcomes such as achievement of remission, individual and pooled trial statistics were calculated as risk ratios (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). A random‐effects model was used to pool data. The results for each analysis were tested for heterogeneity using the Chi2 and I2 statistics.

Studies were separated into two groups: A. one form of enteral nutrition compared to another form of enteral nutrition and B. one form of enteral nutrition compared to corticosteroids. Pre‐specified subgroup analyses included: (i) age (i.e. adults > 18 years versus children < 18 years); (ii) disease duration (i.e. new onset defined as disease duration of < 6 months versus chronic disease defined as disease duration of > 6 months); (iii) disease location (i.e. small bowel, large bowel, or both); (iv) fat composition (i.e. low fat versus high fat content; long chain triglyceride content; or fatty acid content); (v) protein composition (i.e. elemental, semi‐elemental polymeric; or nitrogen source); and (vi) type of carbohydrate source.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted on the basis of: (i) the inclusion of abstracts; and (ii) methodologic quality, excluding studies of lower quality (i.e. at least one aspect of the study considered to be at high risk of bias).

Results

Description of studies

The literature search conducted on July 5, 2017 identified 1135 records. After duplicates were removed, a total of 859 remained for review of titles and abstracts. At least two authors (NN, AD and DZ) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of these trials. A total of 80 studies were selected for full text review (see Figure 1). Forty reports of 38 studies were excluded (see:Characteristics of excluded studies). Thirty‐four reports of 27 studies (1,011 participants) studies met the pre‐defined inclusion criteria and were included in the review (see Characteristics of included studies). Six ongoing studies were also identified (NCT00265772; NCT01728870; NCT02056418; NCT02231814; NCT02843100; NCT03176875; see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease Of the 17 trials comparing different formulations of enteral nutrition, 13 compared two or more enteral nutrition formulas based on the nitrogen source. See additional Table 3 for formula composition in studies comparing different forms of enteral nutrition. Of these trials, four compared one or more elemental formulae to a semi‐elemental formula (Mansfield 1995: Middleton 1995; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002). One of these studies had four arms, three of which were different elemental diets while the fourth arm was a semi‐elemental diet (Middleton 1995). For comparative purposes, the three elemental arms were pooled into one elemental group (standard elemental + long chain triglyceride enriched elemental + medium‐chain triglyceride enriched elemental) for analysis. Seven additional trials compared an elemental to a polymeric formula (Giaffer 1990; Grogan 2012; Kobayashi 1998; Park 1991; Raouf 1991; Rigaud 1991; Verma 2000), while two trials compared a semi‐elemental to a polymeric formula (Griffiths 2000; Seidman 2003). The Griffiths 2000 study, published in abstract form, was only included in the sensitivity analysis. An additional study compared two polymeric diets differing only in glutamine enrichment (Akobeng 2000). This study was not included in the primary analysis but in the subgroup analyses.

1. Formula Composition in Studies Comparing Different Forms of Enteral Nutrition.

| Study | EN type / name | Route | TME (kcal/d) | Ptn (g/1000kcal) | Fat (g/1000kcal) | C (g/1000kcal) |

| Akobeng 2000 | Polymeric glutamine enriched/NS | oral/NG | 2400 | 39.6 | 38.8 | 123 |

| Polymeric/NS | oral/NG/gastrostomy | 2200 | 35.4 | 38.5 | 128.1 | |

| Bamba 2003 | Elemental/Elental (low) | NG | 2400 | 32.85 | 1.3 | 221 |

| Elemental/Elental (medium) | NG | 2400 | 32.85 | 6.9 | 208 | |

| Elemental/Elental (high ) | NG | 2400 | 32.85 | 12.5 | 196 | |

| Gassull 2002 | Polymeric/n9‐rich | oral/NG | 2307 | 54 | 35 | 116 |

| Polymeric/n6‐rich | oral/NG | 2266 | 54 | 35 | 116 | |

| Giaffer 1990 | Elemental/Vivonex | NG | 2500 | 20.5 | 1.44 | 225 |

| Polymeric/ Fortison | NG | 2500 | 40 | 40 | 120 | |

| Grogan 2012 | Elemental/Emsogen | oral/NG | 2106 | 33.07 | 39.23 | 129.2 |

| Polymeric/Alicalm | oral/NG | 2176 | 30.8 | 39.23 | 126.9 | |

| Leiper 2001 | Polymeric (low LCT) | oral (NG if could not tolerate oral) | NS | 39.8 | 38.7 | 122.8 |

| Polymeric (high LCT) | oral (NG if could not tolerate oral) | NS | 39.8 | 38.7 | 122.8 | |

| Mansfield 1995 | Elemental/E028 | NG | 2250 | 26.2 | 17.4 | 184.6 |

| Semi‐elemental/Pepti‐2000 LF liquid | NG | 2250 | 40 | 10 | 187.5 | |

| Middleton 1995 | Elemental/E028 | oral | NS | 26.2 | 17.4 | 184.6 |

| Elemental MCT‐enriched/E028 MCT | oral/NG | NS | 28.2 | 39.5 | 133.2 | |

| Elemental LCT‐enriched/E028 LCT | oral/NG | NS | 25 | 35 | 146 | |

| Semi‐elemental/ Pepdite 2+ | oral | NS | 29.4 | 36.9 | 137.5 | |

| Park 1991 | Elemental/E028 | NG | 2266 | 30 | 16.7 | 194.6 |

| Polymeric/Enteral 400 | NG | 2289 | 28.75 | 39.16 | 144 | |

| Raouf 1991 | Elemental/E028 | oral | 2000 | 126.2 | 17.4 | 184.6 |

| Polymeric | oral | 2000 | 40 | 40 | 120 | |

| Rigaud 1991 | Elemental/Vivonex HN | NG | 2286 | 45 | 0.9 | 203 |

| Polymeric/Ralmentyl | NG | 2311 | 45 | 30 | 137.5 | |

| Polymeric/Nutrison | NG | 2311 | 40 | 39 | 123 | |

| Royall 1994 | Elemental/Vivonex TEN | ND | NS | 38 | 2.8 | 210 |

| Semi‐elemental/Peptamen | ND | NS | 40 | 39 | 127 | |

| Sakurai 2002 | Elemental/Elental | ND | NS | NS | 1.2 | NS |

| Semi‐elemental/Twinline | ND | NS | NS | 27.8 | NS | |

| Verma 2000 | Elemental/NS | NG | 2500 | 53 | 39.5 | 133.2 |

| Polymeric/NS | NG | 2500 | 53 | 39.5 | 133.2 | |

EN = enteral nutrition

NS = not specified

ND = nasoduodenal

NG = nasogastric

TME = total mean energy intake

Ptn = protein

C = carbohydrate

The studies Griffiths 2000, Kobayashi 1998, Pigneur 2014 and Seidman 2003 were not included in the table because the details for formula composition were not available

The remaining three studies used formulas with a similar protein composition and compared two or more enteral nutrition formulas based on fat composition. Two of these trials compared two polymeric diets (Gassull 2002; Leiper 2001) and one compared three elemental diets (Bamba 2003). One trial had a third arm investigating the effect of steroid therapy (Gassull 2002), which is reported below.

Four studies included pediatric participants (Akobeng 2000, Griffiths 2000, Grogan 2012). All of the other studies enrolled adults. Diets were administered by either nasogastric tube feeds or orally. Withdrawals were higher in the patients using oral administration due to unpalatability. The majority of trials described a mixture of participants with new onset disease and chronic disease as well as a mix of disease location (i.e. small bowel, large bowel or both). Disease activity and remission were defined using the CDAI for eight of the studies (Giaffer 1990; Griffiths 2000; Leiper 2001; Mansfield 1995; Rigaud 1991; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002; Verma 2000), although one study (Royall 1994), used a higher CDAI score of 250 for inclusion criteria as opposed to a CDAI score of 150 or 200 for inclusion in the other studies. The remainder used either the PCDAI (Akobeng 2000; Grogan 2012), the IOIBD plus an elevation of either C‐reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (Bamba 2003; Kobayashi 1998), the Van Hees activity index plus abnormal laboratory results (Gassull 2002), or the Harvey‐Bradshaw simple CDI (Middleton 1995, Park 1991, Raouf 1991), with considerable variation in the disease activity and remission criteria among the three studies. Outcomes were assessed at 28 days in eight trials (Akobeng 2000; Bamba 2003; Gassull 2002;Griffiths 2000; Mansfield 1995; Park 1991; Rigaud 1991; Verma 2000), at 21 days in four trials (Middleton 1995, Leiper 2001; Raouf 1991; Royall 1994), at 24 days in one trial (Kobayashi 1998), at 10 days in one trial (Giaffer 1990), and at 42 days in two trials (Sakurai 2002; Grogan 2012).

Enteral nutritional therapy versus steroid therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease

Among the ten trials comparing enteral nutrition to steroid therapy (see additional Table 4 for formula composition in studies comparing enteral nutrition to steroids), three were abstract publications included only in the sensitivity analysis (Mantzaris 1996; Pigneur 2014; Seidman 1991). The study participants were adults for all the trials except for two (Borrelli 2006; Terrin 2002). All of the trials used conventional PCDAI or CDAI scores to define disease activity and remission except for two trials, which used the van Hees Activity Index (Gassull 2002; Gonzalez‐Huix 1993). Outcome assessments were made at 70 days for one trial (Borrelli 2006), two months for one trial (Pigneur 2014) 42 days in two trials (Lochs 1991; Malchow 1990), at 28 to 30 days in five trials (Gassull 2002; Gonzalez‐Huix 1993; Lindor 1992; Mantzaris 1996; Terrin 2002) and at 21 days in one trial (Seidman 1991).

2. Formula Composition in Studies Comparing Enteral Nutrition to Steroids.

| Study | EN type/name | Route | TME (kcal/d) | Ptn (g/1000kcal) | Fat (g/1000kcal) | C (g/1000kcal) |

| Borrelli 2006 | Polymeric | NG or oral | 120‐130% of RDI (1500‐3000kcal/d) | 35 | 46.6 | 110 |

| Gonzales‐Huix 1993 | Polymeric/Edanec HN | NG | 2800 | 54.6 | 114.2 | 36.2 |

| Lindor 1992 | Semi‐elemental/Vital HN | NS | 40kcal/kg/d | 42 | 11 | 186 |

| Lochs 1991 | Semi‐elemental/Peptisorb | ND | 35kcal/kg ideal BW | 37.5 | 182.5 | 11.1 |

| Malchow 1990 | Semi‐elemental/DFD | oral | 33kcal/kg/d | 35 | 11.1 | 190 |

| Mantzaris 1996 | Polymeric/Nutrison HE | ND | 1.5L/d | 40 | 39 | 123 |

| Saverymuttu 1985 | Elemental diet (Vivonex) plus oral framycetin, colistin and nystatin | NG | 1800‐2400 ml/d | |||

| Seidman 1991 | Elemental/Vivonex | NG | 1kcal/ml, 50‐80kcal/kg/d | |||

| Terrin 2002 | Elemental diet (Pregomin, Milupa), | NG | 50‐60kcal/kg/d | |||

| LEGEND | EN=enteral nutrition; NS= not specified | ND=nasoduodenal; NG=nasogastric | TME=total mean energy intake; RDI=recommended dietary intake | Ptn=protein | C=carbohydrate |

EN = enteral nutrition

NS = not specified

ND = nasoduodenal

NG = nasogastric

TME = total mean energy intake

RDI = recommended dietary intake

Ptn = protein

C = carbohydrate

The Pigneur 2014 study was not included in the table because the details for formula composition were not available

The diets were administered by nasogastric tubes in all but three trials (Borrelli 2006; Gassull 2002; Malchow 1990). In the trial with two enteral nutrition arms versus a steroid arm (Gassull 2002), participants with mild disease activity were allowed to take the feeds orally, while those with moderate to severe disease received the diet nasogastrically. There was a cumulative withdrawal rate of 26% in those receiving enteral nutrition therapy compared to no withdrawals in the steroid group. For the purpose of analysis, the two groups that received different feeds were combined into one enteral nutrition arm and compared to the steroid arm (Gassull 2002). In the second trial that allowed oral intake of the dietary therapy (Malchow 1990), there was a 39% withdrawal rate in the enteral diet group compared to only 9% in the steroid group. In the pediatric study (Borrelli 2006), the majority of participants took the feed orally, but if they failed adequate oral consumption, nasogastric tube feeds were administered (in 23.5% of subjects). The withdrawal rates were similar in both the enteral nutrition (10.5%) and the steroid arm (11.1%). Borrelli 2006 also differed substantially from all other studies in other respects. It included the longest duration of enteral nutrition therapy (70 days) and all patients were recently diagnosed with Crohn's disease (within 12 weeks from presentation). As a result the patients had not been exposed to any medications other than 5‐aminosalicylates (which were discontinued) prior to entering the study.

Two trials included a third arm of combined steroid plus enteral nutritional therapy (Lindor 1992; Mantzaris 1996). The data from these third arms were not included in the analysis. Two trials allowed the use of similar concurrent therapy in both groups (Gonzalez‐Huix 1993; Lindor 1992). These trials were included despite the use of antibiotics since only one or two patients received antibiotics in each group. The use of concurrent therapy with three grams of sulfasalazine per day in the steroid group was reported in two trials (Lochs 1991; Malchow 1990). These were the only two studies that had more than 100 participants in total (Lochs 1991; Malchow 1990). Malchow 1990 had a large dropout rate in the enteral nutrition arm. The concurrent therapy in the steroid arm, the high dropout rate in the nutritional arm and the relatively large sample sizes of these two studies might contribute substantial bias against enteral nutrition in the overall analysis. For this reason, a further subgroup analysis was conducted post hoc, excluding these two trials which used concurrent therapy only in the steroid group. In contrast, the remaining trials in the post hoc subgroup analysis used similar concurrent therapy in both the enteral nutrition and steroid arms (Gonzalez‐Huix 1993, Lindor 1992).

Risk of bias in included studies

The results of the risk of bias analysis are summarized in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Nine studies were judged to have a low risk of bias for random sequence generation (Borrelli 2006; Gassull 2002; Gonzalez‐Huix 1993; Grogan 2012; Leiper 2001; Mansfield 1995; Rigaud 1991; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002). Five studies were rated as low risk of bias for allocation concealment (Akobeng 2000; Gassull 2002; Grogan 2012; Leiper 2001; Royall 1994). The rest of the studies were rated as unclear risk of bias due to insufficient information to permit judgment on at least one of the corresponding items.

Blinding

Seven studies were rated as low risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel (Akobeng 2000; Gassull 2002; Grogan 2012; Leiper 2001; Park 1991; Royall 1994; Verma 2000). Five studies were judged to be at high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel (Borrelli 2006; Gonzalez‐Huix 1993; Lindor 1992; Lochs 1991; Raouf 1991). The remaining studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel due to insufficient information to permit a judgement. Five studies were judged to be at low risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment (Gassull 2002; Leiper 2001; Rigaud 1991; Royall 1994; Terrin 2002). The remaining twenty‐four studies have an unclear risk of bias due to insufficient information to permit judgment on at least one of the corresponding items.

Incomplete outcome data

Twenty‐one studies were rated to be low risk of bias in regards to incomplete outcome data (Akobeng 2000; Borrelli 2006; Gassull 2002; Giaffer 1990; Gonzalez‐Huix 1993; Grogan 2012; Kobayashi 1998; Leiper 2001; Lindor 1992; Lochs 1991; Malchow 1990; Mansfield 1995; Middleton 1995; Park 1991; Raouf 1991; Rigaud 1991; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002; Saverymuttu 1985; Terrin 2002; Verma 2000). Two studies were rated as high risk of bias (Bamba 2003; Griffiths 2000). The remaining four studies have an unclear risk of bias due to insufficient information to permit judgement on this item (Mantzaris 1996; Pigneur 2014; Seidman 1991; Seidman 2003).

Selective reporting

Twenty‐three studies were rated to have low risk of bias in terms of selective reporting (Akobeng 2000; Bamba 2003; Borrelli 2006; Gassull 2002; Giaffer 1990; Gonzalez‐Huix 1993; Griffiths 2000; Grogan 2012; Kobayashi 1998; Leiper 2001; Lindor 1992; Lochs 1991; Malchow 1990; Mansfield 1995; Middleton 1995; Park 1991; Raouf 1991; Rigaud 1991; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002; Saverymuttu 1985; Terrin 2002; Verma 2000). Four studies have an unclear risk of bias due to insufficient information to permit judgment on this item (Mantzaris 1996;Pigneur 2014; Seidman 1991; Seidman 2003).

Other potential sources of bias

Twenty‐one studies were rated as low risk of bias for other potential sources of bias (Akobeng 2000; Bamba 2003; Borrelli 2006; Gassull 2002; Giaffer 1990; Gonzalez‐Huix 1993; Grogan 2012; Kobayashi 1998; Leiper 2001; Lindor 1992; Lochs 1991; Malchow 1990; Mansfield 1995; Middleton 1995; Park 1991; Raouf 1991; Rigaud 1991; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002; Terrin 2002; Verma 2000). One study had a high risk of bias for other bias (Griffiths 2000). Five studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias for other bias due to insufficient information to permit judgment on this item (Mantzaris 1996; Pigneur 2014; Saverymuttu 1985; Seidman 1991; Seidman 2003).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Elemental compared to non‐elemental enteral feeds for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Elemental compared to non‐elemental enteral feeds for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: induction of remission in Crohn's disease Setting: Intervention: Elemental Comparison: non‐elemental enteral feeds | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐elemental enteral feeds | Risk with Elemental | |||||

| Remission rate ‐ Intention to treat | 625 per 1,000 | 638 per 1,000 (550 to 737) | RR 1.02 (0.88 to 1.18) | 378 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1,2 | |

| Adverse events | 174 per 1,000 | 176 per 1,000 (108 to 287) | RR 1.01 (0.62 to 1.65) | 323 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3,4 | |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 173 per 1,000 | 237 per 1,000 (143 to 389) | RR 1.37 (0.83 to 2.25) | 272 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 5,6 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to high or unclear risk of bias. Of 11 studies in the pooled analysis, 2 were rated as low risk of bias, 1 was rated as high risk of bias and 8 were unknown risk of bias

2 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (239 events)

3 Downgraded two levels due to high or unclear risk of bias. Of 9 studies in the pooled analysis, 3 were rated as low risk of bias, 1 was rated as high risk of bias and 5 were rated as unclear risk of bias

4 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (56 events)

5 Downgraded two levels due to unclear risk of bias. Of 7 studies in the pooled analysis, 2 were rated as low risk of bias and 5 were rated as unclear risk of bias

6 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (54 events)

Summary of findings 2. Enteral nutrition compared to corticosteroids for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Enteral nutrition compared to corticosteroids for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: induction of remission in Crohn's disease Setting: Intervention: Enteral nutrition Comparison: corticosteroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with corticosteroids | Risk with Enteral nutrition | |||||

| Remission rate ‐ ITT | 715 per 1,000 | 551 per 1,000 (415 to 737) | RR 0.77 (0.58 to 1.03) | 409 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2, 3 | |

| Remission rate ‐ ITT adult studies | 734 per 1,000 | 477 per 1,000 (382 to 602) | RR 0.65 (0.52 to 0.82) | 352 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 4, 5 | |

| Remission rate ‐ ITT pediatric studies | 607 per 1,000 | 820 per 1,000 (559 to 1,000) | RR 1.35 (0.92 to 1.97) | 57 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 6, 7 | |

| Remission rate ‐ per‐protocol ‐ pediatric studies |

607 per 1,000 | 868 per 1,000 (625 to 1,000) | RR 1.43 (1.03 to 1.97) | 55 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 6, 7 | |

| Adverse events | 159 per 1,000 | 221 per 1,000 (99 to 495) | RR 1.39 (0.62 to 3.11) | 389 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 8, 9, 10 | |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 64 per 1,000 | 189 per 1,000 (65 to 544) | RR 2.95 (1.02 to 8.48) | 169 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 11, 12 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; ITT: Intention‐to‐treat | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to high and unclear risk of bias. Of 8 studies in the pooled analysis 1 was rated as low risk of bias, 4 were rated as high risk of bias and 3 were rated as unclear risk of bias.

2 Downgraded one level due to unexplained heterogeneity (I2 = 67%)

3 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (244 events)

4 Downgraded two levels due to high and unclear risk of bias. Of 6 studies in the pooled analysis 1 was rated as low risk of bias, 3 were rated as high risk of bias and 2 were rated as unclear risk of bias

5 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (203 events)

6 Downgraded two levels due to high and unclear risk of bias. Of 2 studies in the pooled analysis 1 was rated as high risk of bias and the other was rated as unclear risk of bias

7 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (41 events)

8 Downgraded two levels due to high and unclear risk of bias. Of 7 studies in the pooled analysis 1 was rated as low risk of bias, 4 were rated as high risk of bias and 2 were rated as unclear risk of bias.

9 Downgraded one level due to unexplained heterogeneity (I2 = 60%)

10 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (82 events)

11 Downgraded two levels due to high or unclear risk of bias. Of three studies in the pooled analysis, 1 was rated as high risk of bias and 2 were rated as unclear risk of bias.

12 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (26 events)

Enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease

Clinical remission

A meta‐analysis of eleven trials which included 378 patients (adult and pediatric) treated with an elemental diet or a non‐elemental (semi‐elemental or polymeric) diet for active Crohn's disease demonstrated no statistically significant difference in remission rates among diet formulations. Sixty‐four per cent (134/210) of patients in the elemental diet group entered remission compared to 62% (105/168) in the non‐elemental group (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.18; GRADE very low quality). No heterogeneity was detected for this comparison (I2 = 0%). Per‐protocol analysis and a sensitivity analysis excluding a high risk of bias study (Raouf 1991), had no effect on the results.

Adverse events

Nine of the studies examining elemental to non‐elemental diets (semi‐elemental or polymeric) reported on adverse events. Meta‐analysis of these nine studies including 320 patients, showed no statistically significant difference in adverse events rates between the two groups. Seventeen per cent (32/185) of participants in the elemental diet group had an adverse event compared to 17% (24/138) in the non‐elemental diet group (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.65; GRADE very low quality).

Most of the studies did not describe the types of adverse events experienced. However, of those adverse events reported, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal bloating were associated with both elemental and non‐elemental diets.

None of these studies reported on the occurrence of serious adverse events.

Withdrawals due to adverse events

Withdrawals due to adverse events were reported in seven studies. Meta‐analysis of these seven studies, which included 272 patients, showed no significant difference in withdrawals due to adverse events. Twenty‐two per cent (35/162) of patients in the elemental diet group withdrew due to an adverse event compared to 17% (19/110) of patients in the non‐elemental diet group (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.83 to 2.25; GRADE very low quality).

Subgroup analyses: Subgroup analyses were planned a priori to evaluate the influence of disease duration and disease location on remission induction. However, there were inadequate data to allow for these comparisons.

Formula composition:

Protein composition Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the different types of diets (elemental, semi‐elemental and polymeric). There was no statistically significant difference in remission rates between trials comparing elemental and polymeric diets [RR 1.06; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.34] (Giaffer 1990; Grogan 2012; Kobayashi 1998; Park 1991; Raouf 1991; Rigaud 1991; Verma 2000) or between trials comparing elemental and semi‐elemental diets (RR 0.99; 95%CI 0.81 to 1.22) (Mansfield 1995; Middleton 1995; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002). For both comparisons, the statistical test for heterogeneity was not significant. Sensitivity analyses excluding studies at high risk of bias for these two subgroups analyses demonstrated similar results. A sensitivity analysis was conducted including an abstract publication comparing one type of semi‐elemental diet to a polymeric diet in children (Griffiths 2000). The results from the abstract were pooled in the analysis comparing elemental and polymeric diets as one may consider that semi‐elemental diets are more similar in composition to elemental diets as compared to polymeric diets. Therefore, meta‐analysis of eight trials resulted in an increase in the number of participants to 133 in the elemental or semi‐elemental formula groups and 130 in the polymeric group and demonstrated no difference in remission rates between the two cohorts (RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.31). The statistical test for heterogeneity was not significant (I2 = 7%).

All studies compared elemental to non‐elemental diets except one. In this one study, nine patients received a polymeric diet and nine received the same polymeric diet with glutamine enrichment (Akobeng 2000). There was no statistically significant difference in remission rates (RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.31 to 2.04).

Fat content A subgroup analysis was conducted on seven trials comparing low fat (< 20 g fat/1000 kCal) to high fat (>20 g fat/1000 kCal) enteral nutritional therapy including 105 and 104 patients in each group, respectively (Giaffer 1990; Middleton 1995; Park 1991; Raouf 1991; Rigaud 1991; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002). No statistically significant difference in remission rates was found between the groups (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.26) and heterogeneity was not demonstrated (i2=12%). Similarly, a subgroup analysis conducted on four trials comparing very low fat (< 3 g fat/1000 kCal) to high fat formulas (Giaffer 1990; Rigaud 1991; Royall 1994; Sakurai 2002), which included 68 patients in each group demonstrated no statistically significant difference in remission rates between the groups (RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.46) and heterogeneity was not demonstrated (I2=32%).

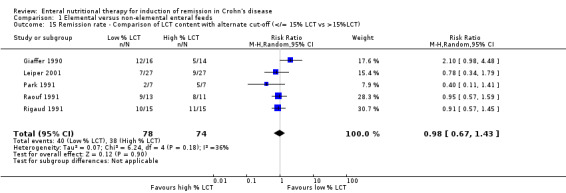

Subgroup analyses were performed on the basis of long chain triglyceride (LCT) content in feeds (in terms of percentage of total energy). The LCT content was classified as low (< 10% LCT) or high (> 10% LCT). Meta‐analysis of six trials (Bamba 2003; Giaffer 1990; Leiper 2001; Rigaud 1991; Raouf 1991; Sakurai 2002) which included 111 patients treated with low LCT content formula and 99 patients treated with a high LCT content formula demonstrated no statistically significant difference in remission rates among diet formulations (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.49). Statistically significant heterogeneity was not present (I2 = 32%). Further analyses using different cut‐offs of % LCT (e.g. 5%, 15%) did not affect the results.

Further subgroup analyses were conducted in three trials (168 patients) on the basis of n‐6 poly‐unsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) composition (Gassull 2002; Griffiths 2000; Grogan 2012). There was no significant difference in remission rates (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.73). A subgroup analysis in two trials (97 patients) on the basis of n‐9 mono‐unsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) composition (Gassull 2002; Leiper 2001), found no significant difference in remission rates (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.36).

Carbohydrate composition When available, the carbohydrate composition was similar between the different formulations and therefore further analyses were not performed.

Enteral nutritional therapy versus steroid therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease

Clinical remission

A meta‐analysis of eight trials, which included 223 patients (adult and pediatric) treated with enteral nutrition and 186 treated with steroids, yielded no statistically significant difference in remission rates between the two groups. Fifty per cent (111/223) of patients in the enteral nutrition group achieved remission compared to 72% (133/186) of patients in the steroid group (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.03; GRADE very low quality). Statistically significant heterogeneity was identified (I2 = 67%). Subgroup analysis by age (children versus adults) demonstrated a statistically significant difference favouring steroid therapy over enteral nutrition for inducing remission in Crohn's disease in adults but not children. Forty‐five per cent (87/194) of adult patients in the enteral nutrition group achieved remission compared to 73% (116/158) of the steroid group (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.82; GRADE very low quality). No significant heterogeneity was demonstrated for this analysis (i2 = 36%). Eighty‐three per cent (24/29) of pediatric patients in the enteral nutrition group achieved remission compared to 61% (17/28) of the steroid group (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.97; GRADE very low quality). No significant heterogeneity was demonstrated for this analysis (i2 = 14%). When a per‐protocol analysis accounting for withdrawals due to inability to tolerate the nasogastric tube or poor palatability of the formulation was performed, there was no statistically significant difference in overall remission rates seen between patients treated with enteral nutrition or steroids. Sixty‐three per cent (111/176) of patients in the enteral nutrition group achieved remission compared to 72% (133/186) of patients in the steroid group (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.14). However, there was a statistically significant difference in remission rates for each age‐based subgroup. Fifty‐eight per cent (87/149) of adult patients in the enteral nutrition group achieved remission compared to 73% (116/158) of the steroid group (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.95). No significant heterogeneity was demonstrated for this analysis (i2 = 0%). Eighty‐nine per cent (24/27) of pediatric patients in the enteral nutrition group achieved remission compared to 61% (17/28) of the steroid group (RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.97; GRADE very low quality). No significant heterogeneity was demonstrated for this analysis (i2 = 0%). In a sensitivity analysis that included two abstract publications, the combined sample sizes increased to 235 in the enteral nutrition group and 195 in the steroid group. There was no statistically significant difference in remission rates (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.10).

As previously reported, the difficulties in double blinding in trials that compare enteral nutrition to steroids led to a high risk of bias rating for the majority of trials. A sensitivity analysis was performed with the two studies that did not have high risk of bias (Gassull 2002; Malchow 1990), and there was a statistically significant result favouring steroid therapy over enteral nutrition (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.70). Heterogeneity was not demonstrated for this comparison(I2 = 0%). There were inadequate data from full publications to perform further subgroup analyses by age, disease duration or disease location.

Adverse events

Seven trials (389 patients) comparing enteral nutrition to steroid therapy reported on the occurrence of adverse events. Meta‐analysis of these trials showed no statistically significant difference in adverse event rates between the two groups. Twenty‐five per cent (54/213) of patients in the enteral nutrition group experienced an adverse event compared to 16% (28/176) of patients in the steroid group (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.62 to 3.11; GRADE very low quality).

While there was no statistical difference in adverse event rates, the types of adverse events experienced amongst the two groups differed. Adverse events experienced in the enteral nutrition group include heartburn, flatulence, diarrhea and vomiting. Whereas in the steroid therapy group,common adverse events experienced are acne, moon facies, hyperglycemia, muscle weakness and hypoglycemia. One patient on steroid therapy reported having an intraabdominal abscess.

None of these studies reported on the occurrence of serious adverse events.

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Only three trials reported on withdrawals due to adverse events (Borrelli 2006; Malchow 1990; Saverymuttu 1985). Meta‐analysis of these studies, which included 169 patients, showed no significant difference in withdrawal due to adverse events. Twenty‐three per cent (21/91) of patients in the enteral nutrition group withdrew due to an adverse event compared to 6% (5/78) of steroid patients (RR 2.95, 95% CI 1.02 to 8.48; GRADE very low quality).

Common reasons cited for withdrawal in the enteral nutrition were unpalatability of diet and non‐tolerance of the nasogastric tube. Some of the reasons given for withdrawal in the steroid therapy group were common side effects associated with steroid use, as described above.

Discussion

Individual studies comparing the effectiveness of enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease have varied considerably in results with remission rates ranging from 20 to 84.2%. This apparent discrepancy may stem from differences involving study populations (e.g. ages, disease activity), interventions (e.g. route of administration), outcome assessments (disease activity measures) and methodology (e.g. sample size, blinding, randomization). This meta‐analysis aimed to pool data from existing randomized controlled studies to examine whether formula composition affected efficacy. No difference in remission rates was observed when different formula compositions were compared by meta‐analytic techniques. Although the choice of activity index utilized in the studies varied, the majority of studies included in the meta‐analysis used a validated index with similar cut‐off values defining inclusion or remission (Sandborn 2002).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses based on study quality or specific aspects of protein or fat composition did not yield any statistically significant differences in remission rates. No statistically significant differences were seen between diets containing different nitrogen sources, classified simply as elemental (free amino acids), semi‐elemental (oligopeptides) or polymeric (whole protein). Comparisons between any combination of the different protein sources showed no significant difference in remission rates. Similarly, one study comparing polymeric diets differing in glutamine‐enrichment showed no difference in remission rates (Akobeng 2000). A non significant trend favouring very low fat and low LCT content was demonstrated in this review. Although different values for LCT content were evaluated and no statistically significant difference was found, the trend supporting lower LCT content was strongest for the lowest value evaluated (< 5% LCT). However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to statistically significant heterogeneity and small numbers of patients resulting in a lack of statistical power to show a difference should one exist. Several studies have hypothesized that the proportion or type of fat in an enteral feeding can affect the production of pro or anti‐inflammatory mediators (Bamba 2003; Gassull 2002; Leiper 2001; Sakurai 2002). The possibility that fat composition influences immunomodulatory or anti‐inflammatory effect in active Crohn's disease warrants further exploration with larger trials.

Data concerning effectiveness of enteral nutrition based on disease duration or disease distribution were not reported in the majority of studies, so subgroup analyses with respect to disease characteristics could not be performed. Several early reports suggest increased efficacy of enteral nutrition in patients with small bowel involvement and those patients with isolated colonic involvement seemed less likely to benefit from enteral feeding (Afzal 2005b; Wilschanski 1996). However, recent studies suggest disease phenotype may not impact response to enteral nutrition. Buchanan 2009 carefully defined phenotypic classification in 110 patients on enteral nutrition and found no significant differences in remission rates based on disease location. One retrospective study compared remission rates according to route of administration, and incidentally found that the site of disease involvement had no impact on response to nutritional therapy (Rubio 2011). Current recommendations suggest the use of exclusive enteral nutrition as first line therapy to induce remission in children with active luminal Crohn's disease (Ruemmele 2014). There are inadequate data from the trials examined in this meta‐analysis to confirm or refute this recommendation. The recent data demonstrating equal efficacy in colonic disease as compared to small bowel disease also suggests a potential role of enteral nutrition as a means to induce patients with ulcerative colitis and this merits further investigation.

The use of enteral nutritional therapy to treat active Crohn's disease was shown to be less effective than conventional corticosteroid therapy in past meta‐analyses (Fernandez‐Banares 1995; Griffiths 1995; Messori 1996). This updated meta‐analysis confirms this finding in adult populations and suggests that enteral nutrition may be more effective than steroids in pediatric populations. Further research about which form of intervention is most effective in pediatric patients is warranted. On a per‐protocol basis, no statistically significant difference in the overall effect estimate was seen between enteral nutrition and corticosteroid therapy. This suggests that failure of enteral nutrition therapy may be due to difficulty with tolerating nasogastric tube feeding and poorly palatable formulations. For the per‐protocol analysis, steroids were superior to enteral nutrition in adults and enteral nutrition was superior to steroids in children.

This meta‐analysis did not aim to compare the method by which enteral nutrition should be delivered to induce remission. Although polymeric diets are more palatable, failure of enteral nutrition can occur if inadequate oral administration occurs, and the nasogastric route should then be used to optimize compliance and effectiveness (Knight 2005). Although exclusion of a normal diet or nasogastric route of administration may be viewed as barriers to enteral nutritional therapy, even young children can learn to insert the tube for overnight feeds (Sanderson 2005). Recent efforts by industry to develop palatable polymeric formulas may help increase acceptance from patients since the use of nasogastric feeding can be avoided. Various flavouring agents also assist to make these formulas more palatable.

There is substantial variability in use of enteral nutrition in different parts of the world. Whereas 62% of western European gastroenterologists use this therapy routinely for the management of pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease, only 4% of American gastroenterologists regularly use enteral nutrition in their practice (Levine 2003). A barrier to its uptake in the United States is related to personal experience and training of clinicians involved in patient care. Clinicians trained in a centre where enteral nutrition is not used routinely are less likely to adapt it for use in their own practice. Other barriers preventing routine use of enteral nutrition include the lack of a uniform protocol on its use, uncertainty regarding the duration of treatment, uncertainty whether concurrent oral intake should be permitted, and how to reintroduce food once remission has been induced. Immunomodulators or biologic therapies are often used for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease, but there may be a role for continuing to use enteral nutrition in patients with quiescent disease. Small studies suggest remission could be maintained by delivering a portion of caloric intake via overnight enteral feeding by nasogastric tube and allowing patients to eat normally during the day (Takagi 2006; Wilschanski 1996; Yamamoto 2007). This needs to be confirmed in larger studies and different populations before being adapted.

There are several additional benefits to enteral nutrition that are not examined in this meta‐analysis due to insufficient data. Adverse events often seen in patients using corticosteroids such as stunted growth or osteoporosis are not a concern when using enteral nutrition. Although patients treated with corticosteroids often achieve clinical remission, corticosteroids often fail to induce mucosal healing (Modigliani 1990). Case series have described mucosal healing with enteral nutrition therapy (Fell 2000; Yamamoto 2007). The Borrelli 2006 trial which failed to show a significant difference in remission rates between enteral nutrition and corticosteroids, did demonstrate a significant difference in mucosal healing with enteral nutrition. The goals of treatment of Crohn’s disease have changed in the past decade, with a recent focus on targeting objective improvement in several domains including mucosal healing. In addition to symptom control, this advantage of enteral nutrition also adds further appeal over corticosteroid therapy.

In summary, meta‐analysis of the available trials has not demonstrated any significant benefit based on the formula composition of nutritional therapies. More prospective data are needed to evaluate the effect of disease factors such as disease location and duration on response to therapy. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of enteral nutrition for the induction of remission in Crohn's disease is evident from the remission rates shown in the trials included in this meta‐analysis. The additional benefits for mucosal healing, growth, nutritional status and quality of life should strengthen the argument for considering the use of enteral nutrition as primary therapy in Crohn's disease. Given that no statistically significant difference in remission rates was seen between enteral nutrition and corticosteroid therapy when analyzed on a per‐protocol basis, this suggests a need to focus on methods of increasing compliance with enteral nutrition therapy from patients, including the development of palatable polymeric formulations that can be delivered without use of a nasogastric tube. Further study on the mechanisms by which enteral nutrition works, its use in maintenance of remission, whether it should be combined with drug therapy for induction or maintenance of remission, and the efficacy of enteral nutrition in ulcerative colitis are needed.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Very low quality evidence suggests that corticosteroid therapy may be more effective than enteral nutrition for induction of clinical remission in adults with active Crohn's disease. Very low quality evidence also suggests that enteral nutrition may be more effective than steroids in children with active Crohn's disease. Protein composition does not appear to influence the effectiveness of enteral nutrition for the treatment of active Crohn's disease. Enteral nutritional therapy should be considered as therapy for Crohn's disease in certain cases, such as in pediatric patients or in patients who can comply with nasogastric tube feeding or perceive the formulations to be palatable, or when steroid side effects are not tolerated or better avoided.

Implications for research.

Further research is required to confirm the superiority of corticosteroids over enteral nutrition in adults. Further research is required to confirm the benefit of enteral nutrition in children. More effort from industry should be taken to develop palatable polymeric formulations that can be delivered without use of a nasogastric tube as this may lead to increased patient compliance with this therapy..

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 March 2018 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Updated review with changes to the conclusions and new authors |

| 5 July 2017 | New search has been performed | New literature search was conducted on 5 July 2017. Four new studies were added to the review |

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Anne Griffiths for her contribution to the original meta‐analysis on this subject matter for the Cochrane Collaboration. The authors would also like to thank Mr. Byungju Lee for his assistance with the quality assessment and Dr. Latifa Yeung for translation of one study (Kobayashi 1998).

Funding for the Cochrane IBD Group (May 1, 2017 ‐ April 30. 2022) has been provided by Crohn's and Colitis Canada (CCC).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Embase on OVID:

1. random$.tw.

2. factorial$.tw.

3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).tw.

4. placebo$.tw.

5. single blind.mp.

6. double blind.mp.

7. triple blind.mp.

8. (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

9. (double$ adj blind$).tw.

10. (tripl$ adj blind$).tw.

11. assign$.tw.

12. allocat$.tw.

13. crossover procedure/

14. double blind procedure/

15. single blind procedure/

16. triple blind procedure/

17. randomized controlled trial/

18. or/1‐17

19. (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.)

20. 18 not 19

21. crohn*.mp.

22. exp Crohn disease/

23. ileitis.mp.

24. enteritis, regional.mp.

25. or/21‐24

26. 20 and 25

27. enteral nutrition.mp. or exp enteral nutrition/

28. food.mp. or exp food/

29. diet.mp. or exp diet/

30. polymeric diet.mp. or exp polymeric diet/

31. elemental diet.mp. or exp elemental diet/

32. or/27‐31

33. 26 and 32

MEDLINE on OVID:

1. random$.tw.

2. factorial$.tw.

3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).tw.

4. placebo$.tw.

5. single blind.mp.

6. double blind.mp.

7. triple blind.mp.

8. (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

9. (double$ adj blind$).tw.

10. (tripl$ adj blind$).tw.

11. assign$.tw.

12. allocat$.tw.

13. randomized controlled trial/

14. or/1‐13

15. (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.)

16. 14 not 15

17. crohn*.mp.

18. exp Crohn disease/

19. ileitis.mp.

20. enteritis, regional.mp.

21. or/17‐20

22. 16 and 21

23. enteral nutrition.mp. or exp enteral nutrition/

24. food.mp. or exp food/

25. diet.mp. or exp diet/

26. polymeric diet.mp. or exp polymeric diet/

27. elemental diet.mp. or exp elemental diet/

28. or/23‐27

29. 22 and 28

CENTRAL

#1. crohn* #2. enteral nutrition or food or diet or polymeric diet or elemental diet #3. #1 and #2

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 1 Remission rate ‐ Intention‐to‐treat.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 2 Remission rate ‐ Per‐protocol.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 3 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 4 Remission rate ‐ elemental versus polymeric enteral feeds.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 5 Remission rate ‐ elemental versus semi‐elemental.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 6 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis elemental vs polymeric, excluding studies at high risk of bias.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 7 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis elemental vs semi‐elemental, excluding studies at high risk of bias.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 8 Remission rate ‐ elemental vs non‐elemental enteral feeds: sensitivity analysis including abstract.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 9 Remission rate ‐ Protein composition: polymeric vs glutamine‐enriched polymeric.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 10 Remission rate ‐ Comparison of fat content: very low fat vs high fat.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 11 Remission rate ‐ Comparison of fat content: low fat vs high fat.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 12 Remission rate ‐Type of fat in non‐elemental feeds: n9 rich feeds.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 13 Remission rate ‐ Type of fat in non‐elemental feeds: n6 rich feeds.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 14 Remission rate ‐ Comparision of LCT content: low % LCT (<10%) vs high % LCT (>10%).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 15 Remission rate ‐ Comparison of LCT content with alternate cut‐off (</= 15% LCT vs >15%LCT).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 16 Remission rate ‐ Comparison of LCT content with alternate cut‐off (</=5%LCT vs >5% LCT).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 17 Adverse events.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elemental versus non‐elemental enteral feeds, Outcome 18 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

Comparison 2. Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Remission rate ‐ Intention‐to‐treat | 8 | 409 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.58, 1.03] |

| 1.1 Pediatric studies | 2 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.92, 1.97] |

| 1.2 Adult studies | 6 | 352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.52, 0.82] |

| 2 Remission rate ‐ Per‐protocol | 8 | 362 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.75, 1.14] |

| 2.1 Pediatric studies | 2 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.43 [1.03, 1.97] |

| 2.2 Adult studies | 6 | 307 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.70, 0.95] |

| 3 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis including abstracts | 10 | 430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.65, 1.10] |

| 4 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias | 2 | 157 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.39, 0.70] |

| 5 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis excluding trials with concurrent therapy | 4 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.48, 1.22] |

| 6 Remission rate ‐ published studies only semi‐elemental diet vs steroid | 3 | 221 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.50, 0.78] |

| 7 Remission rate ‐ polymeric diet vs steroids | 4 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.50, 1.18] |

| 7.1 Remission rate ‐ published studies only | 3 | 131 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.50, 1.32] |

| 7.2 Remission rate ‐ abstracts only | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.24, 1.35] |

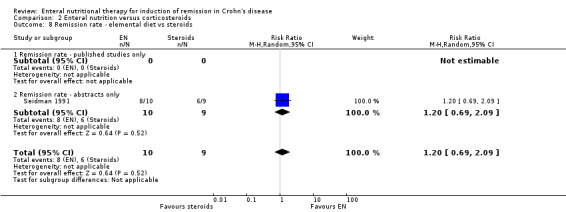

| 8 Remission rate ‐ elemental diet vs steroids | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.2 [0.69, 2.09] |

| 8.1 Remission rate ‐ published studies only | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 Remission rate ‐ abstracts only | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.2 [0.69, 2.09] |

| 9 Adverse events | 7 | 389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.62, 3.11] |

| 10 Withdrawal due to adverse events | 3 | 169 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.95 [1.02, 8.48] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 1 Remission rate ‐ Intention‐to‐treat.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 2 Remission rate ‐ Per‐protocol.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 3 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis including abstracts.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 4 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 5 Remission rate ‐ sensitivity analysis excluding trials with concurrent therapy.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 6 Remission rate ‐ published studies only semi‐elemental diet vs steroid.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 7 Remission rate ‐ polymeric diet vs steroids.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 8 Remission rate ‐ elemental diet vs steroids.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 9 Adverse events.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Enteral nutrition versus corticosteroids, Outcome 10 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Akobeng 2000.

| Methods | Randomized trial (assignments in sealed envelopes), double‐blind (three‐letter codes) | |

| Participants | 18 children, 10 males and 8 females with PCDAI > 12 | |

| Interventions | 9 patients received the glutamine‐enriched polymeric diet and 9 received the standard polymeric diet | |

| Outcomes | Remission rate defined by PCDAI < 10 after 28 days of treatment | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information about sequence generation |