Abstract

Background

Contracting out of governmental health services is a financing strategy that governs the way in which public sector funds are used to have services delivered by non‐governmental health service providers (NGPs). It represents a contract between the government and an NGP, detailing the mechanisms and conditions by which the latter should provide health care on behalf of the government. Contracting out is intended to improve the delivery and use of healthcare services. This Review updates a Cochrane Review first published in 2009.

Objectives

To assess effects of contracting out governmental clinical health services to non‐governmental service provider/s, on (i) utilisation of clinical health services; (ii) improvement in population health outcomes; (iii) improvement in equity of utilisation of these services; (iv) costs and cost‐effectiveness of delivering the services; and (v) improvement in health systems performance.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, EconLit, ProQuest, and Global Health on 07 April 2017, along with two trials registers ‐ ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform ‐ on 17 November 2017.

Selection criteria

Individually randomised and cluster‐randomised trials, controlled before‐after studies, interrupted time series, and repeated measures studies, comparing government‐delivered clinical health services versus those contracted out to NGPs, or comparing different models of non‐governmental‐delivered clinical health services.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened all records, extracted data from the included studies and assessed the risk of bias. We calculated the net effect for all outcomes. A positive value favours the intervention whilst a negative value favours the control. Effect estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals. We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty of the evidence and we prepared a Summary of Findings table.

Main results

We included two studies, a cluster‐randomised trial conducted in Cambodia, and a controlled before‐after study conducted in Guatemala. Both studies reported that contracting out over 12 months probably makes little or no difference in (i) immunisation uptake of children 12 to 24 months old (moderate‐certainty evidence), (ii) the number of women who had more than two antenatal care visits (moderate‐certainty evidence), and (iii) female use of contraceptives (moderate‐certainty evidence).

The Cambodia trial reported that contracting out may make little or no difference in the mortality over 12 months of children younger than one year of age (net effect = ‐4.3%, intervention effect P = 0.36, clustered standard error (SE) = 3.0%; low‐certainty evidence), nor to the incidence of childhood diarrhoea (net effect = ‐16.2%, intervention effect P = 0.07, clustered SE = 19.0%; low‐certainty evidence). The Cambodia study found that contracting out probably reduces individual out‐of‐pocket spending over 12 months on curative care (net effect = $ ‐19.25 (2003 USD), intervention effect P = 0.01, clustered SE = $ 5.12; moderate‐certainty evidence). The included studies did not report equity in the use of clinical health services and in adverse effects.

Authors' conclusions

This update confirms the findings of the original review. Contracting out probably reduces individual out‐of‐pocket spending on curative care (moderate‐certainty evidence), but probably makes little or no difference in other health utilisation or service delivery outcomes (moderate‐ to low‐certainty evidence). Therefore, contracting out programmes may be no better or worse than government‐provided services, although additional rigorously designed studies may change this result. The literature provides many examples of contracting out programmes, which implies that this is a feasible response when governments fail to provide good clinical health care. Future contracting out programmes should be framed within a rigorous study design to allow valid and reliable measures of their effects. Such studies should include qualitative research that assesses the views of programme implementers and beneficiaries, and records implementation mechanisms. This approach may reveal enablers for, and barriers to, successful implementation of such programmes.

Plain language summary

Contracting out to improve the use of clinical health services and health outcomes in low‐ and middle‐income countries

What is the aim of this Review?

This Cochrane Review aims to assess the effects of contracting out healthcare services. Cochrane researchers searched for all relevant studies to answer this question. Two studies met their criteria for inclusion in the Review.

Key messages

Contracting out healthcare services may make little or no difference in people’s use of healthcare services or to children’s health, although it probably decreases the amount of money people spend on health care. We need more studies to measure the effects of contracting out on people’s health, on people's use of healthcare services, and on how well health systems perform. We also need to know more about the potential (negative) effects of contracting out, such as fraud and corruption, and to determine whether it provides advantages or disadvantages for specific groups in the population.

What was studied in the Review?

When governments contract out healthcare services, they give contracts to non‐governmental organisations to deliver these services.

Contracting out healthcare services is common in many middle‐income countries and is becoming more common in low‐income countries. In many of these countries, government‐run services are understaffed or are not easily accessible. Private healthcare organisations, on the other hand, often are more widespread and sometimes are well funded by international donors. By contracting out healthcare services to these organisations, governments can make healthcare services accessible to more people, for example, those in rural and remote areas.

However, contracting out might be a more expensive way of providing healthcare services when compared with services provided by governments themselves. Some governments may find it difficult to manage non‐governmental organisations and to ensure that contractors deliver high‐quality, standardised care. The process of giving and managing contracts may create opportunities for fraud and corruption.

What are the main results of the Review?

The review authors found two studies that met the criteria for inclusion in this Review. One study was from Cambodia. This study compared districts that contracted out healthcare services versus districts that provided healthcare services that were run by the government. The second study was from Guatemala. This study assessed what happened before and after preventive, promotional, and basic curative services were contracted out. These studies showed that contracting out:

• probably makes little or no difference in children’s immunisation uptake, women’s use of antenatal care visits, or women’s use of contraceptives (moderate‐certainty evidence);

• may make little or no difference in the number of children who die before they are one year old, or who suffer from diarrhoea (low‐certainty evidence); and

• probably reduces the amount of money people spend on their own health care (moderate‐certainty evidence).

Included studies did not report the effect of contracting out on fairness (equity) in the use of healthcare services nor on side effects such as fraud and corruption.

How up‐to‐date is this Review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to April 2017.

Summary of findings

Background

The origin of contracting public (i.e. governmental) services out to non‐governmental service providers can be traced back to the rise of the new public management doctrine in the 1980s, with its emphasis on results‐oriented management and improved productivity in the public service sector (Hood 1991). Around the same time, it became increasingly common for governmental services, including healthcare services, to be contracted out to non‐governmental (i.e. private) service providers (Greve 2001; Palmer 2006). Many elements of this new public management doctrine, such as linking rewards with performance and promoting competition between service providers, became part of the way in which governments engage with non‐governmental providers (NGPs), whether for‐profit or not‐for‐profit enterprises.

Contracting out of public health services is a financing strategy that governs the way in which public sector funds are used to deliver these services (Lagarde 2009). This strategy is operationalised in many different ways (see How the intervention might work below) but at its core is a contract between the government and the NGP that details the mechanisms and conditions by which the NGP is to provide healthcare services on behalf of the government (Lagarde 2009; Levin 2011).

Contracting with NGPs is a viable option for meeting human resource shortages in rural and remote areas (Randive 2012). Advantages include that it offers a more focussed service provision because measurable outcomes are specified in the contract (Marek 1999; Palmer 2006); it circumvents governmental bureaucracy; it decentralises decision‐making to those who provide the services (Loevinsohn 2004); it allows governments to focus on roles they are uniquely placed to play, such as planning and standard setting (Loevinsohn 2004); and it may improve equity in the utilisation of clinical health services (Bhushan 2002). Key to the success of contracting out is close monitoring and evaluation of how the NGP meets contract deliverables (Greve 2001; Liu 2007). One consequence of contracting out that is ambiguous in terms of being positive or negative is fragmentation of health services: Palmer 2006 cited examples from England and New Zealand in which fragmentation, or decentralising, of services, was beneficial, whilst it had the opposite effect in Afghanistan (Arur 2010). In the latter case, the detrimental effect of lacking standardised practises was made worse by further decentralisation of services to different NGPs.

Many confounders can impact the effects of contracting out. These include, amongst other issues, (i) opportunities for fraud and corruption may occur during the tender and contract management processes (Greve 2001; Heard 2011); (ii) contracting out may be more expensive than provision of the same service by the government because of high transaction costs between the government and the NGP (Bel 2007); (iii) mistrust may develop in the contractual relationship for the NGP, government, or both (Batley 2006; Girth 2014; Van Slyke 2007); and (iv) governments may be unable to sustain contracts (England 2004). It is argued that when contracting out occurs in response to ineffective government service delivery, these same governments often lack the capacity to effectively manage the contract, thereby countering the aim of improved service delivery by an NGP (Bustreo 2003; Mills 1998a).

Evidence on the outcomes of contracting out is as varied as its benefits and challenges. One review found mixed results when non‐clinical services were contracted out (Mills 1998a); another review highlighted the paucity of high‐certainty evidence (England 2004); and the Loevinsohn 2004 and Liu 2007 reviews reported positive evidence for some outcomes, such as a decline in child malnutrition and improved utilisation of services, respectively. This is the first update of the Cochrane Review published in 2009 (Lagarde 2009).

Description of the condition

Although contracting out of public healthcare services initially occurred mainly in middle‐income countries, it is increasingly found in low‐income countries (Arur 2010). Palmer 2006 surmises that this is due to the fact that contracting out is presented as a solution to address inadequate provision of health care by governments (Mills 1998; Tanzil 2014), and that it is used when the private sector is well funded by international donors (Vian 2007). Contracting out is therefore seen as a useful strategy for improving and scaling up healthcare service delivery in fragile states (Bloom 2006).

Description of the intervention

The intervention ‐ contracting out ‐ is defined as the provision of any clinical health service on behalf of the government (purchaser) by non‐governmental providers (NGPs), regardless of whether they are for‐profit or not‐for‐profit providers (Heard 2011; Palmer 2006), whereby NGPs (contractors) are compensated for the services they provide (Levin 2011). For this review, we have defined clinical health services as any preventative and/or curative medical services that are provided by professional (e.g. doctors, pharmacists, psychologists, occupational therapists, nurses) or para‐professional healthcare workers (e.g. formally trained nurse aides, physician assistants, emergency service paramedical workers) at primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare facilities. These two cadres of health workers received formal tertiary education for their respective professions (Lewin 2005). We excluded from this review healthcare services contracted out to lay health workers (i.e. workers with no professional or paraprofessional tertiary education) (Lewin 2005).

How the intervention might work

The most fundamental element of the intervention is a contract between a government and an NGP that details (i) the healthcare services the NGP will provide on behalf of the government (Lagarde 2009), and (ii) the compensation offered by the government in return for these services (Liu 2007). However, as alluded to in the flowchart below, the government can source NGPs and adjudicate contracts in more than one way (Waters 2000). Governments may choose to select the NGP rather than inviting interested agencies to apply. They can contract with one NGP to provide an agreed service, or they can reduce the risk of selecting a contractor who may not honour the contract by contracting with several NGPs for each to provide a proportion of an agreed service (Heard 2011). Commonly, the NGP is an organisation, yet a government can also contract with individuals, as was the case with private specialists who were contracted by the government to provide emergency obstetrical care in rural India (Randive 2012).

If sourcing NGPs is accomplished through a tendering process, the contract amount could be specified in the tender documentation made available beforehand, or the tendering brief may invite applicants to state a cost for services that they wish to provide (Zaidi 2012). In a similar way to sourcing NGPs, government can manage the NGP’s performance in different ways ‐ an issue that is becoming increasingly more challenging as contractual relationships become more complex and ambiguous (Girth 2014). A third party can be appointed for this role, or it can be performed in‐house by the government (Heard 2011), and payment penalties, also referred to as “sanctions”, and/or bonus payments may be used to ensure that the NGP honours the contract (Girth 2014, p. 318).

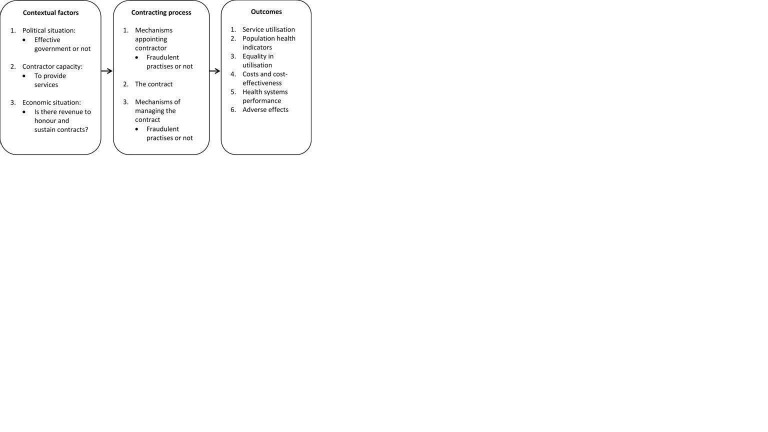

As pointed out by Agyepong and Adjei, any health reform, including contracting out, is as much a political matter (i.e. shaped by those in power who determine health policies and oversee their implementation) as it is a technical matter (i.e. its content and implementation requires technical expertise from all involved in the contracting out process) (Agyepong 2008). Contextual issues and processes such as those listed in Figure 1 were planned to be treated as effect modifiers and included in the analysis, as their importance in shaping the contracting out process and ultimately the outcomes cannot be ignored (Bel 2007; Greve 2001; Lagarde 2009; Liu 2007; Mills 1998a). When the included studies did not present these modifiers as numerical data, it was decided that they should be narratively reported in the same way as in the original review (Lagarde 2009).

1.

How the intervention might work.

Why it is important to do this review

In an attempt to ensure that high‐quality public health services are equitable and accessible in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMIC), it often happens that governments will contract these services to non‐governmental providers. A case in point is the National Department of Health in South Africa, which in 2011/12 adopted a ‘National Health Insurance’ policy with the aim of increasing participation of the private sector in the delivery of public health services. Private general practitioners and community pharmacies are among the providers earmarked by the National Department of Health to be contracted with to provide clinical health services on behalf of the government. Similarly, in Nigeria, the federal government, through the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), has involved a non‐governmental organisation in the accreditation of private and public hospitals to implement NHIS (see NHIS 2011).

Lagarde 2009, the original EPOC review on this topic, was published in 2009, with the main searches completed in 2006 and updated in May 2009. This review indicated that contracting out has become more common practise in many low‐ and middle‐income countries, and it can be assumed that evidence on its effects continue to accumulate. This update also expanded the outcomes by including health system performance as a measure of its effects. This inclusion reflects concern expressed in Liu 2007 that past evaluations reported primarily on how contracting out impacted access to, and utilisation of, services, with little reference to its impact on the healthcare system.

Objectives

To assess effects of contracting out governmental clinical health services to non‐governmental service provider/s on (i) utilisation of clinical health services; (ii) improvement in population health outcomes; (iii) improvement in equity of utilisation of these services; (iv) costs and cost‐effectiveness of delivering the services; and (v) improvement in health systems performance.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered the following study designs for inclusion (EPOC 2017a).

Individual randomised trials.

Cluster‐randomised trials and non‐randomised studies with at least two intervention sites and two control sites, or two intervention groups for each type of intervention.

Controlled before‐after (CBA) studies with at least two intervention sites and two control sites at which data collection was contemporaneous and identical methods were used.

Interrupted time series studies with at least three data points before and three after the intervention.

Repeated measures studies wherein measurements were made for the same individuals at least three data points before and three after the intervention.

Types of participants

The unit of analysis was the populations that access and use governmental clinical health services that are contracted out to non‐governmental providers, whether for‐profit and/or not‐for‐profit providers. Participants included users and non‐users of these services, as well as health facilities at all levels where these contracted services are provided. Given that the intervention is directly linked to, and impacted by, the economic status and political conditions of a country, we assumed that the outcomes would not be transferable between LMIC and high‐income countries. We therefore limited the review to LMIC as defined by the World Bank (World Bank 2016), using its classification of countries into low‐income, lower‐middle‐income, and upper‐middle‐income economies.

Types of interventions

We defined the intervention ‐ contracting out ‐ as the provision of any clinical health service on behalf of the government by for‐profit and/or not‐for‐profit, non‐governmental providers. The intervention had to meet the following two criteria.

A formal contractual relationship between the government and a non‐governmental provider must be described.

The object of the contract must be that the non‐governmental provider will provide, on behalf of the government, clinical health services for a specific (i) geographical area, (ii) patient population, and (iii) period of time. Non‐clinical services, such as catering, will not be included.

We measured the intervention effect by comparing:

contracting out versus no contracting out. Outcomes (listed under Types of outcome measures below) for routine governmental clinical health services that are not contracted out were to be compared with the same set of outcomes for governmental clinical health services that are contracted out to NGP/s; and

-

one model of contracting out versus another model. In this instance, the compared models had to be different from each other based on well‐described contracting features, for example:

tender process: competitive bidding versus fixed bidding for the contract;

contract duration: annual renewal versus multi‐year contracts; or

governmental stewardship: different incentive structures offered by the government and/or whether the government does the monitoring and evaluation of contract deliverables in‐house versus an externally appointed agency.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Utilisation of health services

Utilisation of clinical health services that are contracted out, with the unit of analysis being an individual’s initial contact with a professional health worker during a given time period and/or the number of services an individual received from a healthcare professional in a given time period for those services contracted out (Andersen 2005; Bhandari 2006)

Health outcomes

Measured as patient level mortality and morbidity

Secondary outcomes

Equity in utilisation of clinical health services

Measured as the level of disparity in healthcare utilisation by individuals of different socio‐economic status (Braveman 2003; Waters 2000); use of healthcare services was to be treated as a dependant variable, and independent variables were to include issues such as personal income, employment status, private health insurance or not, and the degree of ill health

Economic outcomes

Cost‐effectiveness of delivering contracted out clinical health services measured in terms of incremental cost per quality‐adjusted life‐years (QALYs) gained or incremental cost per disability‐adjusted life‐years (DALYs) averted

Costs and savings to government, contracted agencies, and patients

Economic measure of health benefit such as QALYs and DALYs

Health system performance

Measured in terms of health service delivery, health workforce, health information, availability of essential medicines, and health financing indicators (as listed below) (World Health Organization 2010a)

Health service delivery

Number and distribution of inpatient beds per 10,000 population

Number of outpatient department visits per 10,000 population per year (service utilisation)

General and specific service readiness scores for health facilities

Proportion of health facilities offering specific services

Number and distribution of health facilities offering specific services per 10,000 population

Quality of services (i.e. structural indicators that assess NGP attributes such as availability of specified services, as well as compliance with clinical guidelines) (Liu 2007)

Health workforce

Number of healthcare workers per 10,000 population

Distribution of healthcare workers by specialisation, region, place of work, and gender

Health information

Health information system performance index, which is a composite of scores showing the overall availability of national databases for various health statistics. Although this particular indicator may not be used in the included studies, they may include outcomes measured with respect to availability and/or quality of clinical data for monitoring and evaluation

Availability of selected essential medicines

Average availability of selected essential medicines in public and private facilities

Median consumer price ratio of selected essential medicines in public and private facilities

Health financing

Ratio of household out‐of‐pocket payments for health to total expenditure on health, noting that this will be differently interpreted in a very low‐income setting than in a low‐income setting (World Health Organization 2010b)

Adverse effects

Fraudulent practices in contracting non‐governmental providers

Job insecurity for governmental‐provider employees

Compared with standard care, the intervention does not improve but worsens the primary and secondary outcomes listed above

It should be noted that we did not include the economic and health system performance outcomes in the previous version of this review (Lagarde 2009). We added these to provide additional insight into the effects of contracting out.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) for primary studies included in related systematic reviews.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases for related reviews.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 3) in the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) (searched 06 April 2017).

We searched the following databases for primary studies.

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily, and MEDLINE 1946 to Present, Ovid (searched 06 April 2017).

National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED; 2015, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) (searched 06 April 2017).

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily and MEDLINE 1946 to Present, Ovid (searched 06 April 2017).

Embase 1974 to 2017 April 05, Ovid (searched 06 April 2017).

EconLit 1969 to present, ProQuest (searched 19 April 2016).

Global Health 1973 to 2016 Week 14, Ovid (searched 19 April 2016).

Latin American Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Virtual Health Library (LILACS VHL) (http://lilacs.bvsalud.org/en/) (searched 06 April 2017).

The EPOC Information Specialist in consultation with the review authors developed the search strategies. Search strategies comprised keywords and controlled vocabulary terms. We applied no language or time limits. We searched all databases from database start date to date of search.

Searching other resources

We conducted a grey literature search to identify studies not indexed in the databases listed above.

Grey literature

Eldis: http://www.eldis.org/ (searched 09 October 2014)

Google Scholar: http://scholar.google.com/ (searched 06 October 2017)

Grey Literature Report: http://www.nyam.org/library/ (searched 06 October 2017)

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Library: http://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/search/advanced (searched 26 January 2018)

OpenGrey: http://www.opengrey.eu (searched 06/10/2017)

World Bank: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/docadvancesearch (searched 26 January 2018)

Trial registries

ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (NIH): clinicaltrials.gov (searched 10 October 2017)

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), World Health Organization (WHO): http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/ (searched 10 October 2017)

We also:

screened individual journals and conference proceedings (e.g. handsearch);

reviewed reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews/primary studies;

contacted authors of relevant studies/reviews to clarify reported published information and to seek unpublished results/data;

contacted researchers with expertise relevant to the review topic/EPOC interventions; and

conducted a cited reference search for all included studies in Web of Science.

We have provided in Appendix 1 all strategies used, including a list of sources screened and relevant reviews/primary studies reviewed.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors screened abstracts and titles and the full texts retrieved for studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria (see the screening tool in Appendix 2). We resolved disagreements during the abstract/title and full text screening by conducting internal discussions and consulting with the EPOC contact editor.

Data extraction and management

We used a standardised data extraction form to record the following information from included studies.

Type of study.

Duration of study.

Study setting (country, key features of the healthcare system, external support, other health financing options in place, other ongoing economic/political/social reforms).

Characteristics of participants (e.g. catchment area size, characteristics of the population, existing health service provision).

Characteristics of interventions (nature of the contractor, scope and characteristics of the contract).

Main outcome measures and results.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias using the EPOC prespecified domains (EPOC 2017b). We resolved disagreements by discussion or, when no consensus was reached, by involving a third review author. These risk of bias domains include random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, missing outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases identified by review authors.

We have judged each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear and have provided a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised 'Risk of bias' judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed.

We also assessed included studies for risks specifically associated with cluster‐randomised trials (Higgins 2011). We assessed the study on recruitment bias (when individuals were recruited to the trial after clusters were randomised), imbalance between clusters at baseline, loss of clusters during the trial, incorrect analysis methods, and comparability of the study with other randomised trials.

In assessing the overall risk, we considered the likely direction and magnitude of the risks and whether they resulted in biased findings. An overall high risk of bias, being a plausible bias that seriously weakens the level of certainty of results, implied a ‘high risk’ score in one or more of the domains. An overall unclear risk of bias, being a plausible bias that raises some doubt about certainty of the results, meant an ‘unclear risk’ score in one or more of the domains. An overall low risk of bias, being a plausible bias unlikely to seriously change the results, implied a ‘low risk’ score in all domains.

Measures of treatment effect

We measured effects by mean percentages before and after the intervention. We calculated the intervention effect as the percentage difference between pre‐intervention and post‐intervention (i.e. INTeffect = INTpost ‐ INTpre). Similarly, we calculated the control effect as CONTeffect = CONTpost – CONTpre. We then calculated the net effect as the difference between intervention and control effects: Net effect = INTeffect ‐ CONTeffect. This net effect, which uses the scale of percentage points, is comparable with difference‐in‐difference estimates, as it is calculated in the same way and on the same scale. The net effect is thus the intervention effect after adjustments for the control effect. The percentage point is the arithmetical difference between two percentages, and as such, it can be a positive or negative value, indicating the direction of the net effect. Positive percentage differences favour the intervention, whilst negative percentage differences favour the control. The magnitude of the difference suggests the extent of the favour. We have presented effect estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We calculated the net effect for Bloom 2006 to allow for comparison with Cristia 2015, which reported difference‐in‐difference estimates. The CIs presented for Bloom 2006 represent CIs for the intervention effect and can be found in Table 2. We could not calculate CIs for the net effect in Bloom 2006, as standard errors for the comparison were not provided in the text. The CIs presented for Cristia 2015 represent the CIs for the net effect.

1. Bloom results: intervention effects and confidence intervals reported as percentages.

| Outcome | Intervention effect (CI) |

| Immunisation of children 12 to 24 months old over a 12 month period | 7.6% (‐10.0% to 25.2%) |

| High‐dose vitamin A to children 6 to 59 months old over a 12 month period | 20.3% (6.6% to 34.0%) |

| Antenatal visits in the previous 12 months | 13.8% (‐5.8% to 33.4%) |

| Birth deliveries by trained professionals over a 12 month period | ‐5.5% (‐11.4% to 0.4%) |

| Female use of contraceptives in the previous 12 months | ‐1.5% ( ‐7.4% to 4.4%) |

| Use of district public healthcare facilities when sick in the previous 12 months | 16.6% (6.8% to 26.4%) |

| Mortality in the past year of children younger than 1 year over a 12 month period | ‐4.3% (‐10.2% to 1.6%) |

| Incidence of diarrhoea in children younger than 5 years over a 12 month period | ‐25.2% (‐62.4% to 12.0%) |

| Individual healthcare expenditures over a 12 month period | $ ‐25.89 (2003 USD) ($ ‐35.93 to $ ‐15.855) |

| Health information: accuracy of facility registers | 12.7% (‐57.9% to 83.3%) |

| Availability of selected essential medicines: availability of child vaccines at facilities in the previous 3 months | 14.6% (‐20.7% to 49.9%) |

In future updates, we plan to meta‐analyse intervention outcomes by converting estimates of effect from the primary analysis into risk ratios, with reported adjusted analyses for dichotomous or continuous outcomes. Should odd ratios be reported for dichotomous outcomes, we will convert these into risk ratios before doing the meta‐analysis, using RevMan 5.3 (2014). If we find any interrupted time series studies in future, we plan to record changes in level and slope. If these results are not properly analysed and reported, we will attempt to re‐analyse the data using methods described in Ramsay 2003. If this review is to be updated, we suggest that studies reporting multiple measures of the same outcome should be analysed in accordance with steps proposed by Brennan 2009. These include choosing the trial authors' primary outcome/s that relate closest to the review's primary outcomes; should we identify no such primary outcome/s, selecting the outcome used in calculating the sample size; when no sample size calculations are found, ranking the effect estimates and using the outcome with the median effect estimate. We also propose for the next update of this review that economic outcome data should be extracted in keeping with guidelines described in the UK National Health Services’ Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (Craig 2007).

Unit of analysis issues

For future updates we will re‐analyse the cluster‐randomised trials that do not account for clustering, provided that the following information is available.

Number of clusters that were randomised to each intervention group, or the mean size of each cluster.

Estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (if this is not reported, this coefficient will be extracted from similar CRTs).

Outcome data for the total number of individuals in the study, thus not taking clusters into account.

When it is not possible to adjust the analysis, we will present the results separately and will not combine them in a meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

For this update, we identified no missing data. Should data be missing, we would contact trial authors to request the data. We will report data not obtained as missing data in the risk of bias table.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed whether studies were similar with respect to participants, settings, interventions, and outcome measures. When meta‐analysis was possible, we would have assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection of the meta‐analyses' forest plots (i.e. by looking at the direction of the intervention effect and its size). We would have used a Chi2 test to determine whether observed differences in outcomes between studies are due to chance only. If differences were bigger than expected by chance only, we will assume that statistical and/or clinical heterogeneity is present across studies. We will use the I2 statistic to indicate the degree of statistical heterogeneity. The threshold for substantial heterogeneity will be an I2 value between 50% and 100%, and we will further analyse such cases in subgroup analyses as described below.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots to examine asymmetry and to assess the potential that any asymmetry may be due to publication bias. However, we identified too few studies of similar comparisons to allow a meaningful assessment of asymmetry.

Data synthesis

As the two included studies used different study designs (cluster trial and before‐after study), we did not synthesise the data. We graded our confidence in available estimates of effects using GRADE, as described in Cochrane 2011. This approach classifies the certainty of evidence into four categories: high, moderate, low, and very low.

For future updates, we will use RevMan software to conduct meta‐analyses of pooled outcome data. We will present an estimate of treatment effect for different studies with similar interventions; these studies must be comparable with respect to methods, settings, participants, and outcomes. We will not combine randomised and non‐randomised trials. We will calculate pooled estimates for non‐randomised trials using different designs. We will perform random‐effects meta‐analysis to combine data, as heterogeneity across studies is assumed, given differences in settings and intervention mechanisms. For studies with results adjusted for confounding variables, we will use the inverse variance available in RevMan (version 5.3) for the meta‐analysis. We will analyse repeated measures studies and interrupted time series studies using a regression analysis with time trends before and after the intervention. We will express outcomes for such studies as changes in:

level (i.e. the immediate effect of the intervention, measured as the difference between the fitted value for the first post‐intervention data point minus the predicted outcome measured at the first post‐intervention data point); and

slope (i.e. the change in trend from before to after the intervention). We will present long‐term effects in a similar way as immediate effects. We will report effects at six months as the difference between the fitted value for month six as the post‐intervention data point minus the predicted outcome six months post intervention based on the pre‐intervention slope. We will apply the same method to measure effects after 12 and 24 months.

'Summary of findings'

We prepared a ‘Summary of findings’ table for the main intervention comparison and included the seven most important outcomes, based on the review team's judgement of outcomes most likely to influence (i) policy makers' decision to implement contracting out, and (ii) use of these contracted out services by patients and the general public. The seven outcomes are immunisation of children, antenatal visits, female use of contraceptives, mortality of children younger than one year, diarrhoea in children under five years old, equity in the use of clinical health services, and individual healthcare expenditures (Table 1). Two review authors independently assessed the overall certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low, and very low), using the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to downgrade the certainty and three factors to upgrade the certainty (large effect size, confounder, dose response) (Guyatt 2008). We used methods and recommendations as described in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011), along with the EPOC worksheets (EPOC 2017c). We provided justification for decisions to downgrade or upgrade the ratings using footnotes in the table and made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review when necessary. We used plain language statements to report these findings in the review (EPOC 2017d). For outcomes presented in Table 1, we have presented the evidence profile in Appendix 3, and for all other outcomes, in Appendix 4.

for the main comparison.

| Contracting out compared with not contracting out for providing clinical healthcare services | |||||

|

Population: people who use governmental clinical health services that are contracted out to non‐governmental providers Intervention: provision of any clinical health service on behalf of the government by for‐profit and/or not‐for‐profit, non‐governmental providers Comparison: contracting out vs no contracting out | |||||

| Outcomes | Net effecta | No. of studies | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE)b | Results in words | Comments |

| Utilisation of health services | |||||

|

Immunisation of children 12 to 24 months old (over a 12 month period) |

Fully immunised Net effect = ‐39.4%, intervention effect P = 0.46, clustered SE = 9.0%; see Table 2 for the CI Measles Net effect = 46.5%, SE = 28.5%, 95% CI ‐9.4% to 102.4% DPT Net effect = ‐1.4%, SE = 22.9%, 95% CI ‐46.3% to 43.5% Polio Net effect = ‐7.6%, SE = 24.1%, 95% CI ‐54.8% to 39.6% |

2c,d | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatee |

Contracting out probably makes little or no difference in immunisation uptake of children 12 to 24 months old over the previous 12 months. | |

|

Antenatal visits (over the previous 12 months) |

> 2 antenatal care visits Net effect = ‐12.2 %, intervention effect P = 0.35, clustered SE = 10.0%; see Table 2 for the CI ≥ 3 antenatal care visits Net effect = 27.4%, SE = 22.2%, 95% CI ‐16.1% to 70.9% |

2c,d | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatee |

Contracting out probably makes little or no difference in the number of women who had > 2 antenatal care visits over the previous 12 months. | |

|

Female use of contraceptives (over a 12 month period) |

Net effect = ‐11.5%, intervention effect P = 0.78, clustered SE = 3.0%; see Table 2 for the CI Net effect = 1.9%, SE = 6.9%, 95% CI ‐11.6% to 15.4% |

2c,d | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatee |

Contracting out probably makes little or no difference in female use of contraceptives over the previous 12 months. | |

| Health outcomes | |||||

|

Mortality in the past year of children younger than 1 year (over a 12 month period) |

Net effect = ‐4.3%, intervention effect P = 0.36, clustered SE = 3.0%; see Table 2 for the CI | 1c | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowe,f |

Contracting out may make little or no difference in the mortality of children younger than 1 year over a 12 month period. | Trial authors conclude that the sample size was too small to detect typical mortality. |

|

Incidence of diarrhoea in children younger than 5 years (over a 12 month period) |

Net effect = ‐16.2%, intervention effect P = 0.07, clustered SE = 19.0%; see Table 2 for the CI | 1c | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowe,f |

Contracting out may make little or no difference in the incidence of childhood diarrhoea over a 12 month period. | |

| Equity in utilisation of clinical health services | |||||

| Not reported in the included studies | |||||

| Economic outcomes | |||||

|

Individual healthcare expenditures (over a 12 month period) |

Net effect = $ ‐19.25 (2003 USD), intervention effect P = 0.01, clustered SE = $ 5.21; see Table 2 for the CI | 1c | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatee |

Contracting out probably reduces individual out‐of‐pocket spending on curative care over a 12 month period. | The reduction in individuals’ healthcare expenditure is in line with the reported decrease in people visiting private healthcare providers. |

| Adverse effects | |||||

| Not reported in the included studies. | |||||

|

a Calculated as the difference between the change in the intervention group and the change in the control group: Net effect = (INTpost – INTpre) – (CONTpost – CONTpre). bGRADE Working Group grades of evidence: ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High certainty: This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different* is low. ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate certainty: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different* is moderate. ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low certainty: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different* is high. ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very low certainty: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different* is very high. * Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision. cBloom 2006 (cluster‐randomised trial). dCristia 2015 (CBA). e Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias. Study 1 (Bloom 2006) is at high risk of bias as baseline participant characteristics are not reported, and Study 2 (Cristia 2015) is at high risk of other bias because estimates of effects correspond with a strengthened model of the intervention compared with the initial model. f Downgraded by one for serious imprecision. The study reported treatment of the treated (ToT) estimates. Actual numbers for numerator and denominator were not provided. | |||||

DPT: diphtheria‐pertussis‐tetanus

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Owing to the way participant groups were presented in the included studies, we conducted no subgroup analyses. For the next update, we will use the latest version of RevMan to conduct analyses between two or more subgroups to investigate the variance in intervention effect for different interventions and settings due to confounding variables (see Contextual factors and Contracting mechanisms, in Figure 1) that could impact the intervention effect. The analysis will detect true differences between subgroups, not sampling error. Subgroup samples must be exclusive to a group, enough trials must be reported before an important comparison is possible. If we identify 10 times or more studies than the number of independent variables, we will perform a meta‐regression analysis to simultaneously explore the intervention effect on estimates of effects and the effects of different settings and interventions. We will use non‐overlapping confidence intervals for random‐effects meta‐analyses to detect an important difference between subgroups in relation to the treatment effect. When meta‐analysis is not appropriate, we will report subgroup results narratively.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct a sensitivity analysis, as we included only two studies in this review. For future updates, we will conduct a sensitivity analysis by removing studies with an overall high risk of bias from the meta‐analyses described above. Should cluster‐randomised trials be combined, analysis will involve varying the intracluster correlation coefficient. For non‐randomised trials that present results adjusted and not adjusted for confounding variables, we will conduct a sensitivity analysis of results that were not adjusted.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

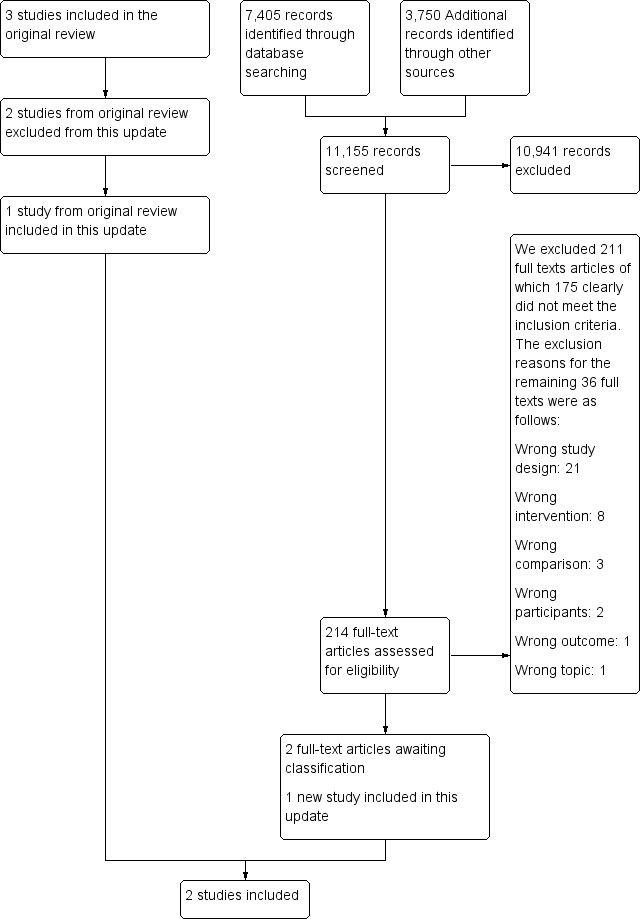

We screened 11,155 references retrieved from databases and other sources, and we excluded 10,941 records after a review of titles and abstracts. We retrieved the full texts of 214 articles for detailed assessment. Of these, we excluded 211 articles because they did not meet the review inclusion criteria. We included one new study in this update and one study from the previous version of the review. Two studies are awaiting classification. We have presented additional detail in the study flow diagram in Figure 2.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Two studies met the inclusion criteria of this review: a cluster‐randomised trial conducted in Cambodia (Bloom 2006), and a controlled before‐after study implemented in Guatemala (Cristia 2015). Bloom 2006 was included in the previous version of the Cochrane Review (Lagarde 2009).

As the manner in which the intervention was implemented differed substantially between studies, the table below summarises (i) contexts, content, and outcomes of respective contracting out programmes, and (ii) process variables listed in Figure 1, which we consider drivers of the intervention that are as important as the intervention itself. We have presented additional details in Characteristics of included studies.

| Descriptor | Bloom 2006 | Cristia 2015 |

| Context | (1) Cambodia, currently a lower‐middle‐income country. The intervention, implemented over 4 years (1999 to 2003), targeted the health needs of rural, under‐resourced communities and reached approximately 1.26 million people ‐ 11% of the country’s population. (2) The intervention aimed to redress a dysfunctional health system. (3) 12 districts were randomised to control and intervention arms. (4) The intervention arm also included a model of contracting for public health services. We excluded this model, as NGPs had to operate within government structures, and this did not meet our intervention inclusion criteria. | (1) Guatemala, currently a lower‐middle‐income country. The intervention, implemented over 10 years (1997 to 2007), targeted the health needs of rural, under‐resourced communities and reached about 4.2 million people ‐ a third of the country’s population. (2) The intervention was provided when a three‐decade‐long civil war ended and aimed to redress a dysfunctional health system. (3) Communities receiving the intervention were selected in an ad hoc manner. |

| Appointing non‐ governmental service providers (NGPs) | (1) NGPs were not required to be licensed before they could bid for the contract. (2) A competitive bidding process was followed and contracts awarded to NGPs with the highest score on technical abilities and costs. (3) All contracted NGPs were international non‐governmental organisations. | (1) NGPs in Guatemala had to be licensed, based on issues such as staff, infrastructure, and relevant experience, before they could bid for the contract. (2) A competitive bidding process resulted in contracts awarded only on technical abilities because the budget within which NGPs had to provide health care was predetermined. (3) Most contracted NGPs were local non‐governmental organisations. |

| Contract and intervention | (1) NGPs were contracted to provide all preventive, promotional, and basic curative healthcare services mandated for a district by the Ministry of Health; they had "pretty much full authority for and responsibility over their districts” (Bloom 2006, p. 7) and could decide how they would provide services, manage staff and salaries, and procure drugs, supplies, and equipment. (2) This was a facility‐based intervention that focussed on improving services at public facilities. (3) NGPs were contracted to deliver specific services and achieve corresponding targets. (4) The government did not involve local leaders to promote the use of contracted healthcare services. | (1) NGPs were contracted to establish mobile medical teams who provided a basic set of preventative care services for mothers and children up to two years old. The teams comprised a physician or a nurse and a health assistant, who conducted monthly visits to targeted communities. These visits included checkups, immunisations, and education sessions. (2) This was a community‐based intervention in which NGPs did not manage the public health facilities. (3) Contracts detailed specific services and corresponding targets that the NGP had to deliver and achieve. (4) The government involved local leaders and community volunteers to promote the use of contracted out healthcare services. |

| Outcomes | Maternal and child health outcomes plus other outcomes such as facility performance and healthcare expenditures over 12 months | Maternal and child health outcomes over 12 months |

| Monitoring mechanisms | (1) The government established monitoring teams that conducted quarterly visits to the districts. These visits comprised unannounced visits to health facilities, community surveys, and patient visits to establish whether patients received health care at the respective facilities. (2) Failing to meet agreed targets resulted in withholding of payment until the problem was resolved. (3) No fraudulent practises were reported. | (1) Monitoring mechanisms are not described, but contracts became more detailed and contract renewal criteria stricter over time. (2) Failure on contract deliverables resulted in cancellation of contracts by the government. (3) No fraudulent practices were reported. |

| Governmental commitment | The government provided political commitment and financial support for successful contracting out of health services. | Trial authors reported that the programme suffered substantial budget cuts between 2000 and 2004. However, a new president, elected in 2004, prioritised the programme, which resulted in huge revenue and support investments. This strengthened the programme considerably. |

| Funding sources | No mention of how the study was funded | No mention of how the study was funded |

| Note: No changes to the programme in Cambodia were reported (Bloom 2006), but several changes took place in Guatemala (Cristia 2015). The first two years (1997 to 1999) saw rapid programme expansion but poor government management and monitoring practises; between 2000 and 2004, drastic budget cuts were made; and a government change in 2004 resulted in a second expansion (2004 to 2005) with renewed government commitment and larger financial investments to make the programme work. Outcome data reported by Cristia 2015 are based on expansion of the programme (2004 to 2005), and "the estimated effects correspond to the strengthened version of the programme that was prevailing at the post‐treatment period (2006)" (Cristia 2015, p. 250). | ||

Bloom 2006 reported ‘intention‐to‐treat’ (ITT) and ‘treatment‐on‐the‐treated’ (TOT) analyses, respectively, for the results presented below. ITT analysis provides treatment effect estimates for all four randomised contracting out districts, including the two not included in the final report owing to unsuccessful bids. Bloom 2006 used ‘province X year fixed effects’ to increase the precision of intervention effect estimates, and to account for random natural events that could affect delivery of the intervention. An example of natural events would be substantial rainfall in a province. TOT analysis provides the treatment effect as measured only in the two successfully contracted out districts. TOT provides estimates for settings in which successful bidding can reasonably be expected. Given that ITT and TOT impact the certainty we place on evidence of the intervention effect (see Table 1), we indicated for each outcome reported by Bloom 2006 whether an ITT or TOT analysis was performed. When researchers reported both ITT and TOT estimates, we chose to report ITT estimates, as this is a more conservative approach to estimating an intervention effect (Armijo‐Olivo 2009). For some outcomes, Bloom 2006 reported only TOT estimates, and in these cases, this is what we have reported.

Outcomes reported in Cristia 2015 resulted from a routine survey conducted during the time of the intervention, but unrelated to the intervention implementation. Aspects of the survey covered maternal (women aged between 15 and 49 who gave birth in the past five years) and child (children aged between 0 and 5) health indicators relevant to the intervention. The survey conducted in the year 2000 served as the source of pre‐intervention data, and the 2006 survey as the source of post‐intervention data. Cristia 2015 used four models of analysis to report effects of the intervention. We reported this group's Model 4, which controlled for use of the same counties in pre‐intervention and post‐intervention assessments, as this model meets eligibility for a controlled before‐after study design in which data collection should be contemporaneous at study and control sites during pre‐intervention and post‐intervention periods of the study, and for which identical methods of measurement should be used. It should be noted that data show a marked difference in numbers of sites and observations compared with other models; for example, for antenatal care outcomes, 33 communities and 280 observations are reported in Model 4 compared with 112 communities and 504 observations reported in other analysis models. This trend is similar across all outcomes. Given that the roll‐out of the intervention was done in a haphazard way, sampling involved unequal probabilities of receiving the intervention. All outcomes have been weighted for representativeness of the population.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 211 full‐text articles. Of these, 175 clearly did not meet inclusion criteria for the review. For the remaining 36 full texts, we have provided reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Reasons for exclusion include ineligible study designs (n = 21), interventions (n = 8), comparisons (n = 3), participants (n = 2), outcomes (n = 1) and topics (n = 1).

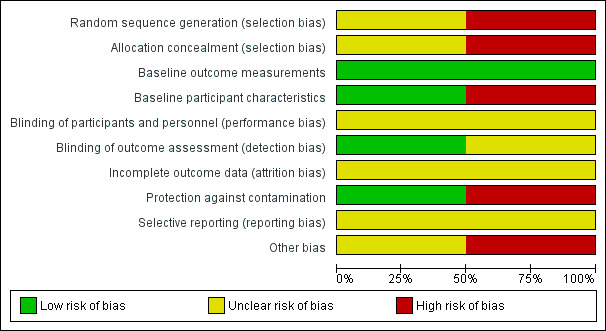

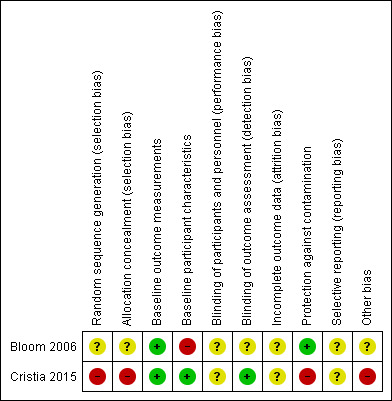

Risk of bias in included studies

We have presented our summary of risk of bias assessments in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Bloom 2006 is a cluster‐randomised trial, but the explanation of sequence generation provided is unclear and therefore may introduce bias. Cristia 2015 is at high risk of selection bias because investigators selected intervention communities in a non‐random manner.

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Bloom 2006 provides a poor description of allocation concealment and therefore has unclear risk of selection bias. Cristia 2015 describes ad hoc selection and allocation of the intervention communities and therefore can be assumed to have high risk of selection bias due to lack of allocation concealment.

Baseline outcome measurements

We rated both studies as having low risk of bias, as baseline outcome measures appear to be similar across intervention and control arms; however study authors report no test for statistical differences.

Baseline participant characteristics

Bloom 2006 is at high risk of selection bias owing to absent or poor reporting of baseline participant characteristics. Cristia 2015 reports baseline characteristics and differences between intervention and control arms that are well balanced, except for a statistical difference in age among children aged 2 to 24 months. We rated this study as having low risk of potential bias.

Blinding of participants and personnel

Bloom 2006 and Cristia 2015 provide no description of blinding, and it is unlikely that this was done. It is unclear whether this would affect the performance of participants or study personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Neither of the included studies reported on blinding of outcome assessment. However, we assessed Bloom 2006 as having unclear risk, as it is unclear whether those who conducted baseline and post‐intervention surveys were not blinded to whether participants belonged to intervention or control arms. In Cristia 2015, risk for bias in this domain is low because the data used to assess intervention effects were extracted from routine surveys that were independent of the intervention itself.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

The included studies did not report attrition; therefore we assessed them as having unclear risk of attrition bias.

Protection against contamination

Bloom 2006 is at low risk for contamination between intervention and control arms because allocation to the respective arms was done at district level, and it is unlikely that the control group received the intervention. We judged the risk in Cristia 2015 as high because the intervention was delivered at a village level, and we cannot exclude the potential that people may have received the intervention when visiting neighbouring villages.

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

It is unclear whether included studies are at risk for bias due to selective reporting because we could not access the respective study protocols.

Other bias

We did not identify potential bias in Bloom 2006; however, we rated Cristia 2015 as having high potential risk of bias due to changes in the context in which the intervention was delivered from the start of evaluation to completion. At the time of the post‐intervention survey, the intervention had been implemented for about eight years, and trial authors reported that estimates of the effects correspond with a "strengthened version" of the intervention (Cristia 2015, p. 250).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

The net effect that we report below is the intervention effect after adjustments for the control effect. The percentage (%) is the arithmetical difference between two percentages, and as such, it can be a positive or negative value, indicating the direction of the net effect. Positive percentage values favour the intervention, whilst negative percentage values favour the control. The magnitude of the percentage suggests the extent of favour. The CIs presented for the intervention effect for Bloom 2006 can be found in Table 2. The grading of evidence certainty for the outcomes reported in the Table 1 is presented in Appendix 3, and for the remaining outcomes in Appendix 4.

We have reported below the effects of contracting out compared with not contracting out.

Primary outcomes

Utilisation of health services

Immunisation of children 12 to 24 months old

Contracting out probably makes little or no difference in immunisation uptake of children 12 to 24 months old over 12 months , whether 'immunisation' refers to being fully immunised or being immunised respectively for measles, diphtheria‐pertussis‐tetanus (DPT), and polio (fully immunised net effect = ‐39.4%, intervention effect P = 0.46, clustered standard error (SE) = 9.0%; moderate‐certainty evidence; Bloom 2006; ITT); (measles net effect = 46.5%, SE = 28.5%, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐9.4% to 102.4%; moderate‐certainty evidence; Cristia 2015); (DPT net effect = ‐1.4%, SE = 22.9%, 95% CI ‐46.3% to 43.5%; moderate‐certainty evidence; Cristia 2015); and (polio net effect = ‐7.6%, SE = 24.1%, 95% CI ‐54.8% to 39.6%; moderate‐certainty evidence; Cristia 2015).

High‐dose vitamin A to children 6 to 59 months old

Bloom 2006 found that contracting out probably slightly improves the number of children 6 to 59 months old who receive high‐dose vitamin A twice in the past 12 months (net effect = 2.3%, intervention effect P = 0.02, clustered SE = 7.0%; moderate‐certainty evidence; ITT).

Antenatal visits

Contracting out probably makes little or no difference in the number of women who had more than two antenatal care visits in the previous 12 months: (> 2 antenatal care visits net effect = ‐12.2%, intervention effect P = 0.35, clustered SE = 10.0%; moderate‐certainty evidence, Bloom 2006; ITT); (≥ 3 antenatal visits to a health professional net effect = 27.4%, SE = 22.2%, 95% CI ‐16.1% to 70.9%; moderate‐certainty evidence; Cristia 2015).

Birth deliveries by trained professionals

Bloom 2006 reported that contracting out probably makes little or no difference in the number of babies deliveries by professionals over 12 months (net effect = ‐15.5%, intervention effect P = 0.33, clustered SE = 3.0%; moderate‐certainty evidence; ITT).

Female use of contraceptives

Contracting out probably makes little or no difference in female use of contraceptives over a 12 month period (net effect = ‐11.5%, intervention effect P = 0.78, clustered SE = 3.0%; moderate‐certainty evidence; Bloom 2006; ITT); (net effect = 1.9%, SE = 6.9%, 95% CI ‐11.6% to 15.4%; moderate‐certainty evidence; Cristia 2015).

Use of district public healthcare facilities when sick

Bloom 2006 reported that contracting out probably slightly increases the use of governmental hospitals and primary healthcare facilities over a 12 month period when sick (net effect = 7.6%, intervention effect P = 0.02, clustered SE = 5.0%; moderate‐certainty evidence; ITT).

Health outcomes

Mortality in the past year among children younger than one year

Bloom 2006 found that contracting out may make little or no difference in the mortality of children younger than one year over a 12 month period (net effect = ‐4.3%, intervention effect P = 0.36, clustered SE = 3.0%; low‐certainty evidence; TOT).

Incidence of diarrhoea among children younger than five years

Bloom 2006 reported that contracting out may make little or no difference in the incidence of childhood diarrhoea over a 12 month period (net effect = ‐16.2%, intervention effect P = 0.07, clustered SE = 19.0%; low‐certainty evidence; TOT).

Secondary outcomes

Equity in utilisation of clinical health services

The included studies did not report the effect of contracting out on equity in use of services.

Economic outcomes

Government healthcare expenditures

Contracting out increased the government’s per capita expenditure by $2.94 (2003 USD) compared with a $1.59 (2003 USD) increase in the control arm over a 12 month period. Researchers performed no statistical comparisons.

Individual healthcare expenditures

Bloom 2006 found that contracting out probably reduces individual out‐of‐pocket spending over 12 months on curative care (net effect = $ ‐19.25 (2003 USD), intervention effect P = 0.01, clustered SE = $ 5.12 ; moderate ‐certainty evidence; ITT).

Health system performance

Health service delivery

The included studies did not report the effect of contracting out on health service delivery.

Health workforce

The included studies did not report the effect of contracting out on the health workforce.

Health information: accuracy of facility registers

Bloom 2006 found that contracting out may make little or no difference in the accuracy of facility registers (net effect = ‐54.3%, intervention effect P = 0.72, clustered SE = 36.0%; low‐certainty evidence; TOT).

Availability of selected essential medicines: availability of child vaccines at facilities

Bloom 2006 found that contracting out may make little or no difference in the availability of child vaccines at facilities in the last three months (net effect = ‐21.4%, intervention effect P = 0.84, clustered SE = 18.0%; low‐certainty evidence; TOT).

Health financing

The included studies did not report the effect of contracting out on health financing.

Adverse effects

The included studies did not report adverse effects resulting from implementing contracting out.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review, which updates the 2009 review (Lagarde 2009), aimed to update the evidence on effects of contracting governmental clinical health services out to non‐governmental service providers. Of the three studies included in Lagarde 2009, we excluded two, applying the revised EPOC study type criteria (EPOC 2017a). We included one new study (Cristia 2015). We found that contracting out may be no better or worse than usual delivery of government services. Specifically, this review confirms the findings from Lagarde 2009 that contracting out probably makes little or no difference in (i) immunisation uptake of children 12 to 24 months old (moderate‐certainty evidence), (ii) antenatal care visits (moderate‐certainty evidence), (iii) female use of contraceptives (moderate‐certainty evidence), (iv) the mortality of children younger than one year (low‐certainty evidence), and (v) childhood diarrhoea (low‐certainty evidence). It was also reported that contracting out probably reduces individual out‐of‐pocket spending on curative care (moderate‐certainty evidence). Neither study reported on any adverse effects that resulted from implementing contracting out, and neither reported on equity in the use of clinical health services. A narrative summary of these studies is provided in Table 3.

2. Summary of contracting out programmes reported since 2009.

| Publication | Setting | Contracting model | Key messages | Study design |

|

Alonge 2014 Ameli 2008 Arur 2010 |

Afghanistan, 2003‐2006/7 (post‐Taliban conflict) | Three models: 1. Province‐wide lump sum contracts; performance bonuses; an independent group monitored performance; a high degree of NGP autonomy; limited capacity building of NGP; government managed contracts 2. Monthly reimbursements made; monitoring through an international non‐profit organisation; no performance bonuses 3. 80% of Year 1 budget paid in advance; donor‐monitored NGP performance; no performance bonuses |

1. Contracting out has been associated with substantial increases in use of curative care, in particular that of poor and female patients. 2. No conclusive evidence shows that any 1 model is more effective than another. 3. Linking equity goals to performance bonuses may reduce the inequity of service utilisation between the poor and the non‐poor. 4. Using service characteristics and geographical distances as planning parameters does not guarantee better resource allocation. 5. The impact of contracting out on the quality of services needs to be researched. |

Contracting out was implemented as routine care. |

|

De Costa 2014 Mohanan 2014 |

India, 2000‐2010 | 1. The government contracted private obstetricians who own hospitals to enable poor women in rural areas to deliver at these facilities. 2. Hospitals had to meet criteria related to size and emergency services. 3. Obstetricians received a fixed reimbursement per 100 deliveries. 4. The reimbursement amount had a build‐in disincentive for caesarean deliveries. |

1. Institutional deliveries increased by 50%. 2. Quality of care and provider attrition need to be researched. Mohanan 2014 3. Investigators contested the success of the programme: Studies claiming programme success did not (i) address the impact of self‐selection of institutional delivery, or (ii) address inaccurate reporting from hospitals. 4. Investigators found no important changes in the probability of institutional delivery. |

Contracting out was implemented as routine care. |

| Heard 2013 | Bangladesh, 1999‐2004 | 1. The government contracted with an NGP or with local government to deliver basic PHC. 2. Competitive bidding for NGP contracts 3. NGPs, but not the local government, were allowed to recruit staff and set salaries and working conditions. 4. NGPs, but not the local government, procured products directly from suppliers. 5. Both NGPs and the local government were reimbursed for documented expenditures. |

1. Improvement in PHC was seen in both models, but the overall quality of care was better in the NGP facilities. 2. NGP facilities provided more PHC services per capita spending. 3. Investing in PHC facilities and contracting with NGPs may improve urban health services. |

Contracting out was implemented as routine care. |

| Kane 2010 | India, 1‐year project, 2007‐2008 | 1. The government partnered with NGPs to improve TB case finding through including it in routine HIV prevention services. 2. 48% of NGPs had formal contracts. 3. The model was translated into national policy through a public sector‐funded TB‐HIV partnership scheme with NGPs. 4. No other details were reported. |

1. TB services can be effectively integrated into HIV prevention services and can be delivered through public‐private partnerships (PPPs). | The PPP was implemented as routine care. |

| Mairembam 2012 | India, 2008‐2012 | 1. PPP to attract and retain skilled health workers 2. Management functions in facilities were contracted to NGPs through a memorandum of understanding. 3. No other details were reported. |

1. Improved service delivery, building maintenance, and staff availability 2. NGPs’ flexible approach in staff recruitment and creating a supportive working environment reduced staff attrition. 3. Being isolated from government‐supported functions limited access to training programmes. 4. Contracting out must happen in the context of broader government support to address isolation from government support. |

The PPP was implemented as routine care. |

| Shet 2011 | India, 2004‐2007 | 1. At the public‐private facility, the government provided free treatment and the private hospital provided the premises, infrastructure, and human resources. 2. No other details were reported. |

1. The fully public and PPP facilities had notably better health outcomes compared with the fully private facility. 2. The fully public facility reported fewer treatment failures compared with PPP and private facilities. 3. Larger studies are required. |

The PPP was implemented as routine care. |

| Tanzil 2014 | Pakistan, 2005‐2011 | 1. The government outsourced administration of PHC to a semi‐autonomous government entity. 2. No other details were reported. |

1. Healthcare services were better managed in contracted out facilities than in fully governmental facilities. 2. Contracting may be effective in rebuilding PHC in low‐ and middle‐income countries. |

Contracting out was implemented as routine care. |

| Vieira 2014 | Guinea Bissau, 2012‐2013 | 1. The government entered a PPP with an NGP to manage a national TB reference centre. 2. Government provided the drugs and electricity, and paid staff. 3. The NGP topped up salaries and provided services. |

1. Since the contracting period, mortality and treatment failure were notably lower compared with during the pre‐contracting period. 2. Direct costs to patients were reduced. 3. PPP may, in the short term, increase adherence to the hospitalisation phase of intensive treatment. |

The PPP was implemented as routine care. |

| Zaidi 2012 | Pakistan, 2003‐2008 | 1. HIV prevention services were contracted out to NGPs through competitive bidding. 2. These were performance‐based contracts according to predefined targets. 3. Contracts were managed by the government. |

1. Contracting out is inherently a political process affected by the wider policy context. 2. Rapid roll‐out in unprepared contexts can be confounded by governments’ capacity to manage it. 3. Governments should be careful that contracting out does not distance NGPs from their historical attributes. 4. Governments’ political willingness and technical capacity are key components of successful programmes. |

Contracting out was implemented as routine care. |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

NGP: non‐governmental provider.

PHC: primary health care.

PPP: public‐private partnership

TB: tuberculosis

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Bloom 2006 reported 48 outcomes on effects of contracting out on various dimensions of the use and delivery of healthcare services. Cristia 2015 reported three outcomes, all of which are also reported in Bloom 2006; these studies reported similar findings. Contracting out is a strategy provided by governments to improve poor healthcare services (Mills 1998; Palmer 2006; Tanzil 2014), in particular in the context of political instability (Alonge 2014). Evidence from Bloom 2006 and Cristia 2015 is highly relevant to these contexts, given that contracting out was implemented after a period of civil war and political instability in the respective study countries. However, we acknowledge the limitation of having only two studies on which to base a decision to implement contracting out. Our review was limited to low‐ and middle‐income countries. As contracting out is impacted by the political conditions and economic status of a country (Bel 2007), it is not advisable to generalise review findings to settings that differ in terms of income status and study contexts.

Certainty of evidence

We presented six outcomes from Bloom 2006. For two of these, we assessed the certainty of evidence as low, given the absence of baseline participant characteristics and the less robust 'treatment of the treated' analysis, which did not provide actual numbers for numerators and denominators. We assessed one outcome as having moderate certainty and graded this down because of the absence of baseline participant characteristics. Cristia 2015 reported the three remaining outcomes; as assessed these as providing moderate‐certainty evidence, given the absence of baseline participant characteristics in Bloom 2006, and given that estimates of effects in Cristia 2015 corresponded with a strengthened model of the intervention compared with the initial model.

Potential biases in the review process

We recognise that we may not have found all studies that were eligible for inclusion in this review; however, we conducted a comprehensive search without restriction on language or date, and we undertook duplicate screening to identify eligible studies. Limiting our inclusion criteria to experimental studies is another potential source of bias. Our review may also have been biased in the light of our narrow definition of contracting out (i.e. that a formal contract between government and non‐governmental health service providers (NGPs) must detail the mechanisms and conditions on which the latter should provide health care on behalf of the government). We therefore excluded public‐private partnerships (PPPs), which are collaborations between governments and NGPs with no contractual arrangements, other than a joint decision to optimise services by working together (Kane 2010; Khatun 2011; Naqvi 2012; Shet 2011; Sinanovic 2006).