Abstract

Background

Persistent infection with high‐risk human papillomaviruses (hrHPV) types is causally linked with the development of cervical precancer and cancer. HPV types 16 and 18 cause approximately 70% of cervical cancers worldwide.

Objectives

To evaluate the harms and protection of prophylactic human papillomaviruses (HPV) vaccines against cervical precancer and HPV16/18 infection in adolescent girls and women.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Embase (June 2017) for reports on effects from trials. We searched trial registries and company results' registers to identify unpublished data for mortality and serious adverse events.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing efficacy and safety in females offered HPV vaccines with placebo (vaccine adjuvants or another control vaccine).

Data collection and analysis

We used Cochrane methodology and GRADE to rate the certainty of evidence for protection against cervical precancer (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and above [CIN2+], CIN grade 3 and above [CIN3+], and adenocarcinoma‐in‐situ [AIS]), and for harms. We distinguished between the effects of vaccines by participants' baseline HPV DNA status. The outcomes were precancer associated with vaccine HPV types and precancer irrespective of HPV type. Results are presented as risks in control and vaccination groups and risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

Main results

We included 26 trials (73,428 participants). Ten trials, with follow‐up of 1.3 to 8 years, addressed protection against CIN/AIS. Vaccine safety was evaluated over a period of 6 months to 7 years in 23 studies. Studies were not large enough or of sufficient duration to evaluate cervical cancer outcomes. All but one of the trials was funded by the vaccine manufacturers. We judged most included trials to be at low risk of bias. Studies involved monovalent (N = 1), bivalent (N = 18), and quadrivalent vaccines (N = 7). Most women were under 26 years of age. Three trials recruited women aged 25 and over. We summarize the effects of vaccines in participants who had at least one immunisation.

Efficacy endpoints by initial HPV DNA status

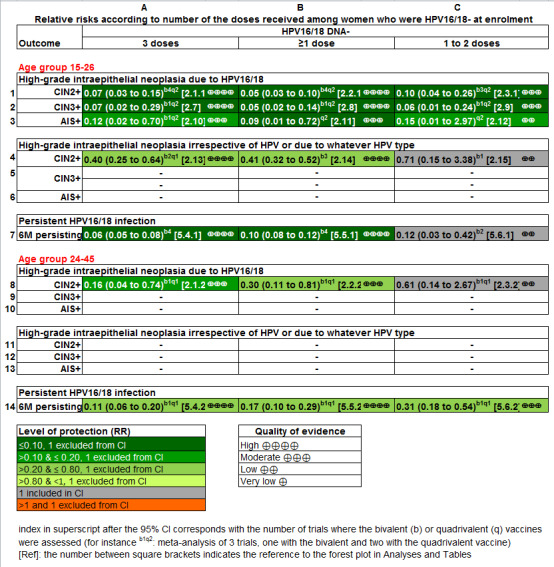

hrHPV negative

HPV vaccines reduce CIN2+, CIN3+, AIS associated with HPV16/18 compared with placebo in adolescent girls and women aged 15 to 26. There is high‐certainty evidence that vaccines lower CIN2+ from 164 to 2/10,000 (RR 0.01 (0 to 0.05)) and CIN3+ from 70 to 0/10,000 (RR 0.01 (0.00 to 0.10). There is moderate‐certainty evidence that vaccines reduce the risk of AIS from 9 to 0/10,000 (RR 0.10 (0.01 to 0.82).

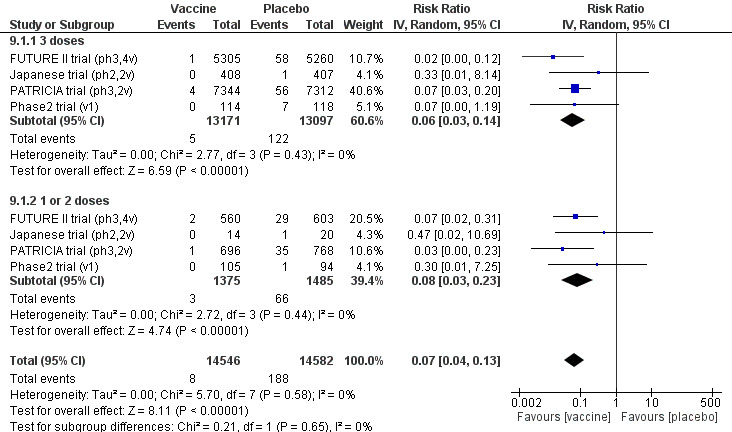

HPV vaccines reduce the risk of any CIN2+ from 287 to 106/10,000 (RR 0.37 (0.25 to 0.55), high certainty) and probably reduce any AIS lesions from 10 to 0/10,000 (RR 0.1 (0.01 to 0.76), moderate certainty). The size of reduction in CIN3+ with vaccines differed between bivalent and quadrivalent vaccines (bivalent: RR 0.08 (0.03 to 0.23), high certainty; quadrivalent: RR 0.54 (0.36 to 0.82), moderate certainty). Data in older women were not available for this comparison.

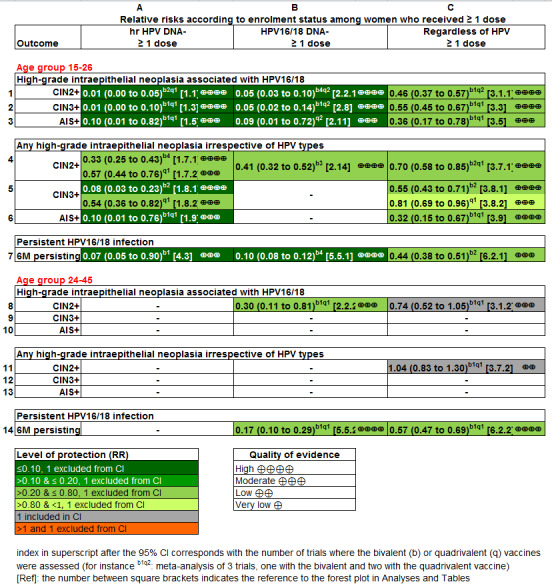

HPV16/18 negative

In those aged 15 to 26 years, vaccines reduce CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18 from 113 to 6 /10,000 (RR 0.05 (0.03 to 0.10). In women 24 years or older the absolute and relative reduction in the risk of these lesions is smaller (from 45 to 14/10,000, (RR 0.30 (0.11 to 0.81), moderate certainty). HPV vaccines reduce the risk of CIN3+ and AIS associated with HPV16/18 in younger women (RR 0.05 (0.02 to 0.14), high certainty and RR 0.09 (0.01 to 0.72), moderate certainty, respectively). No trials in older women have measured these outcomes.

Vaccines reduce any CIN2+ from 231 to 95/10,000, (RR 0.41 (0.32 to 0.52)) in younger women. No data are reported for more severe lesions.

Regardless of HPV DNA status

In younger women HPV vaccines reduce the risk of CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18 from 341 to 157/10,000 (RR 0.46 (0.37 to 0.57), high certainty). Similar reductions in risk were observed for CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18 (high certainty). The number of women with AIS associated with HPV16/18 is reduced from 14 to 5/10,000 with HPV vaccines (high certainty).

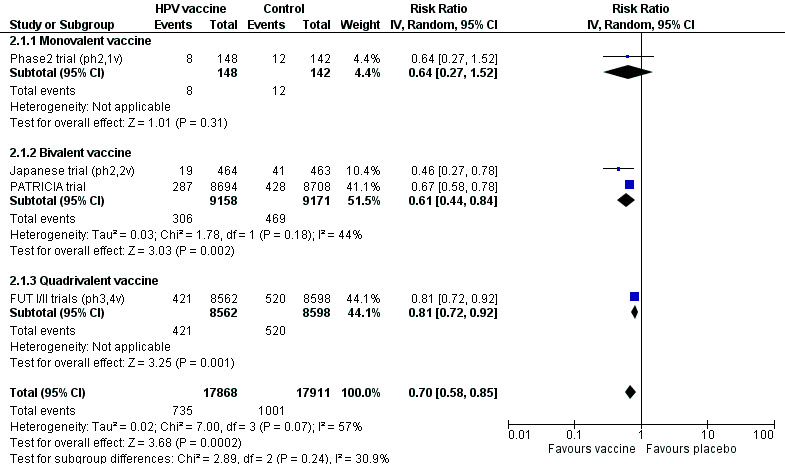

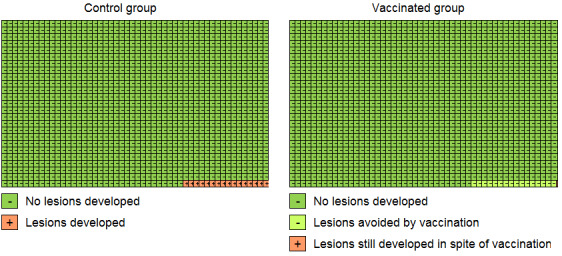

HPV vaccines reduce any CIN2+ from 559 to 391/10,000 (RR 0.70 (0.58 to 0.85, high certainty) and any AIS from 17 to 5/10,000 (RR 0.32 (0.15 to 0.67), high certainty). The reduction in any CIN3+ differed by vaccine type (bivalent vaccine: RR 0.55 (0.43 to 0.71) and quadrivalent vaccine: RR 0.81 (0.69 to 0.96)).

In women vaccinated at 24 to 45 years of age, there is moderate‐certainty evidence that the risks of CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18 and any CIN2+ are similar between vaccinated and unvaccinated women (RR 0.74 (0.52 to 1.05) and RR 1.04 (0.83 to 1.30) respectively). No data are reported in this age group for CIN3+ or AIS.

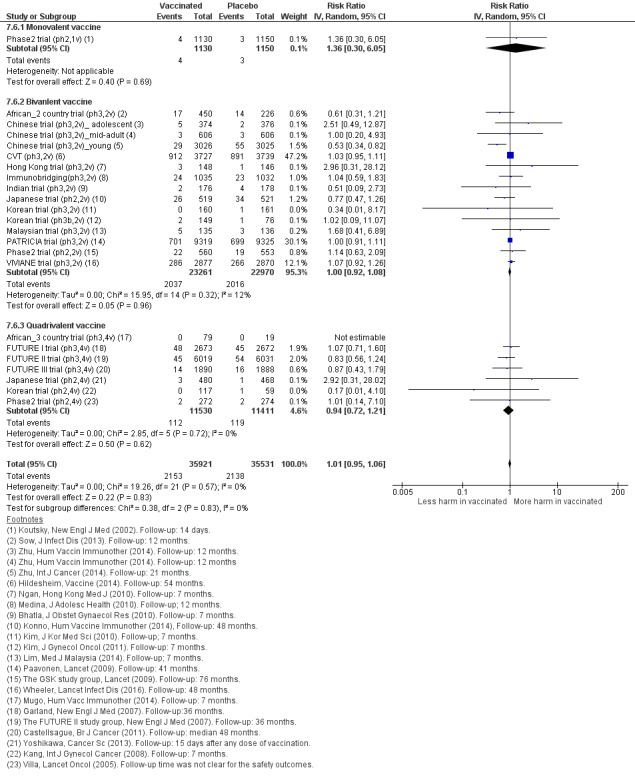

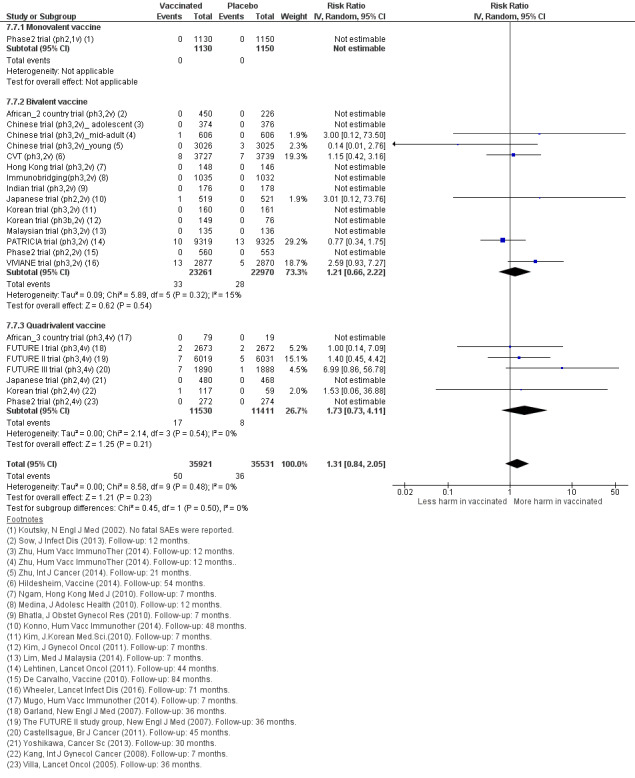

Adverse effects

The risk of serious adverse events is similar between control and HPV vaccines in women of all ages (669 versus 656/10,000, RR 0.98 (0.92 to 1.05), high certainty). Mortality was 11/10,000 in control groups compared with 14/10,000 (9 to 22) with HPV vaccine (RR 1.29 [0.85 to 1.98]; low certainty). The number of deaths was low overall but there is a higher number of deaths in older women. No pattern in the cause or timing of death has been established.

Pregnancy outcomes

Among those who became pregnant during the studies, we did not find an increased risk of miscarriage (1618 versus 1424/10,000, RR 0.88 (0.68 to 1.14), high certainty) or termination (931 versus 838/10,000 RR 0.90 (0.80 to 1.02), high certainty). The effects on congenital abnormalities and stillbirths are uncertain (RR 1.22 (0.88 to 1.69), moderate certainty and (RR 1.12 (0.68 to 1.83), moderate certainty, respectively).

Authors' conclusions

There is high‐certainty evidence that HPV vaccines protect against cervical precancer in adolescent girls and young women aged 15 to 26. The effect is higher for lesions associated with HPV16/18 than for lesions irrespective of HPV type. The effect is greater in those who are negative for hrHPV or HPV16/18 DNA at enrolment than those unselected for HPV DNA status. There is moderate‐certainty evidence that HPV vaccines reduce CIN2+ in older women who are HPV16/18 negative, but not when they are unselected by HPV DNA status.

We did not find an increased risk of serious adverse effects. Although the number of deaths is low overall, there were more deaths among women older than 25 years who received the vaccine. The deaths reported in the studies have been judged not to be related to the vaccine. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes after HPV vaccination cannot be excluded, although the risk of miscarriage and termination are similar between trial arms. Long‐term of follow‐up is needed to monitor the impact on cervical cancer, occurrence of rare harms and pregnancy outcomes.

Plain language summary

HPV vaccination to prevent cancer and pre‐cancerous changes of the cervix

Background Human papillomaviruses (HPV) are sexually transmitted and are common in young people. Usually they are cleared by the immune system. However, when high‐risk (hr) types persist, they can cause the development of abnormal cervical cells, which are referred to as cervical precancer if at least two thirds of the surface layer of the cervix is affected. Precancer can develop into cervical cancer after several years. Not everyone who has cervical precancer goes on to develop cervical cancer, but predicting who will is difficult. There are a number of different hrHPV types which can cause cervical precancer and cancer. HPV16 and 18 are the most important high‐risk types, since they cause about 70% of cervical cancers worldwide. Preventive vaccination, by injection of HPV virus‐like particles in the muscle, triggers the production of antibodies which protect against future HPV infections.

Review question Does HPV vaccination prevent the development of cervical precancer or cancer and what are the harms?

Main results We included 26 studies involving 73,428 adolescent girls and women. All trials evaluated vaccine safety over a period 0.5 to 7 years and ten trials, with follow‐up 3.5 to 8 years, addressed protection against precancer. Cervical cancer outcomes are not available. Most participants enrolled were younger than 26 years of age. Three trials recruited women between 25 to 45 years. The studies compared HPV vaccine with a dummy vaccine.

We assessed protection against precancer in individuals who were free of hrHPV, free of HPV16/18 or those with or without HPV infection at the time of vaccination. We separately assessed precancer associated with HPV16/18 and any precancer.

Protection against cervical precancer

1) Women free of hrHPV

Outcomes were only measured in the younger age group for this comparison (15 to 25 years). HPV vaccines reduce the risk of cervical precancer associated with HPV16/18 from 164 to 2/10,000 women (high certainty). They reduce also any precancer from 287 to 106/10,000 (high certainty).

2) Women free of HPV16/18

The effect of HPV vaccines on risk of precancer differ by age group. In younger women, HPV vaccines reduce the risk of precancer associated with HPV16/18 from 113 to 6/10,000 women (high certainty). HPV vaccines lower the number of women with any precancer from 231 to 95/10,000 (high certainty). In women older than 25, the vaccines reduce the number with precancer associated with HPV16/18 from 45 to 14/10,000 (moderate certainty).

3) All women with or without HPV infection

In those vaccinated between 15 to 26 years of age, HPV vaccination reduces the risk of precancer associated with HPV16/18 from 341 to 157/10,000 (high certainty) and any precancer from 559 to 391/10,000 (high certainty).

In older women, vaccinated between 25 to 45 years of age, the effects of HPV vaccine on precancer are smaller, which may be due to previous exposure to HPV. The risk of precancer associated with HPV16/18 is probably reduced from 145/10,000 in unvaccinated women to 107/10,000 women following HPV vaccination (moderate certainty). The risk of any precancer is probably similar between unvaccinated and vaccinated women (343 versus 356/10,000, moderate certainty).

Adverse effects

The risk of serious adverse events is similar in HPV and control vaccines (placebo or vaccine against another infection than HPV (high certainty). The rate of death is similar overall (11/10,000 in control group, 14/10,000 in HPV vaccine group) (low certainty). The number of deaths overall is low although a higher number of deaths in older women was observed. No pattern in the cause or timing of death has been established.

Pregnancy outcomes

HPV vaccines did not increase the risk of miscarriage or termination of pregnancy. We do not have enough data to be certain about the risk of stillbirths and babies born with malformations (moderate certainty).

Conclusion There is high‐certainty evidence that HPV vaccines protect against cervical precancer in adolescent girls and women who are vaccinated between 15 and 26 years of age. The protection is lower when a part of the population is already infected with HPV. Longer‐term follow‐up is needed to assess the impact on cervical cancer. The vaccines do not increase the risk of serious adverse events, miscarriage or pregnancy termination. There are limited data from trials on the effect of vaccines on deaths, stillbirth and babies born with malformations.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Burden of cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide. It is estimated that in 2012, approximately 528,000 women developed cervical cancer and that 266,000 died from the disease (Ferlay 2015). Eighty‐six per cent of cervical cancer cases occur in developing countries (Arbyn 2011). Cervical cancer is the predominant cancer in women in Eastern Africa, South‐Central Asia and Melanesia, where a woman's risk of developing this disease by age 75 years ranges between 2.3% and 3.9%. In many developed countries, the incidence of, and mortality from, squamous cervical cancer has dropped substantially over the last decades, as a consequence of population‐based screening programmes (Arbyn 2009; Bray 2005a; Ferlay 2015; IARC 2005). However, approximately 54,000 and 11,000 cases are reported each year in Europe and the USA, respectively (Arbyn 2011; Ferlay 2013), and screening with cytology is less effective at preventing cervical adenocarcinoma (Bray 2005; Smith 2000). In contrast to many other malignancies, cervical cancer primarily affects younger women, with the peak age of incidence in the UK now between 25 and 29 years; between 2012 and 2014, 52% of cancers occurred in those under 45 years of age (Cancer Research UK 2018). In the UK (2010 to 2011), despite a comprehensive screening programme, 37% of women with cervical cancer died from the disease within 10 years of diagnosis (Cancer Research UK 2018).

High‐grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2+) is treated by local destruction (ablation) or excision of neoplastic tissue (Jordan 2009). Therapeutic procedures are similarly effective (Martin‐Hirsch 2013), but are associated with an average risk of residual or recurrent CIN2+ of 7% (Arbyn 2017), and an increased risk of late miscarriage and premature labour (Kyrgiou 2017). Primary prevention of CIN lesions by prophylactic (an agent used to prevent disease) vaccination can therefore reduce the burden, costs and adverse effects associated with its treatment.

Association between human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and cervical cancer and other HPV‐related cancers and their precursors

Papillomaviruses are small, icosahedral DNA viruses, that consist of one single double‐stranded circular DNA molecule of approximately 8,000 base‐pairs, contained within a protein capsid. The capsid is composed of two structural proteins, both are encoded by the viral genome: L1 and L2 (IARC 2007). The natural history of HPV infection towards cervical precancer and finally invasive cancer is well documented (Bosch 2002; Castellsagué 2006; IARC 2007). The development of cervical cancer passes through a number of phases: (a) infection of the cervical epithelium with high‐risk human papillomaviruses (hrHPV); (b) persistence of the HPV infection; (c) progression to precancerous lesions with malignant transformation of infected cells; and (d) invasion of surrounding tissue. The steps prior to development of cancer, can regress spontaneously, although regression rates decrease with increasing severity of the precancerous lesion.

Twelve hrHPV types (HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59) are causally linked with the development of cervical cancer (Bouvard 2009). HPV68 is considered as probably carcinogenic (Schiffman 2009). Some other HPV types may in rare occasions also cause cervical cancer (Arbyn 2014). HPV type 16, in particular, has a high potential for malignant transformation of infected cervical cells (Schiffman 2005). The HPV types 16 and 18 jointly cause seven out of 10 cervical cancers worldwide (Munoz 2004). The five next most important high‐risk HPV types (HPV31, HPV33, HPV45, HPV52, and HPV58) together with HPV16/18 are causally linked with approximately 90% of cervical cancers (de Sanjose 2010). HPV16 is also linked with rarer types of cancer, such as cancer of the vulva and vagina in women, penile cancer in men and anal and oropharyngeal cancer in women and men (Cogliano 2005; IARC 2007).

The low‐risk HPV types 6 and 11 cause approximately 90% of genital warts in women and men (Lacey 2006). They occur in low‐grade dysplastic cervical lesions, but are not associated with developing cervical cancer (IARC 2007). HPV types 6 and 11 cause recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, a rare but very serious disease of the upper airways often requiring repetitive surgical interventions (Lacey 2006).

The main route of HPV transmission is sexual contact. Infection usually occurs soon after the onset of sexual activity (Winer 2003; Winer 2008). The prevalence of HPV infection in women generally peaks in late teenage or early twenties (de Sanjose 2007). HPV infection is usually cleared by the immune system (Ho 1998). HPV infection can result in cervical precancer (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)), which can be detected by cervical cytological screening. By microscopic inspection of a cervical smear (also known as a Papanicolaou or 'Pap' test, cervical lesions can be detected (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC‐US), low‐grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high‐grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL),: atypical glandular cells (AGC); for a complete list of abbreviations used in the review, see Appendix 1), which can be confirmed histologically following a cervical biopsy at colposcopic examination (Jordan 2008). In some countries, cytological cervical cancer screening is being replaced by HPV‐based screening, because the latter is more effective at preventing future CIN3 or invasive cancer (Arbyn 2012; Ronco 2014).

A World Health Organization (WHO) expert group accepted a reduction in the incidence of high‐grade CIN (CIN2+) and cervical adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) or worse as an acceptable surrogate outcome of HPV vaccination trials (Pagliusi 2004). This is because the reduction of the incidence of invasive cervical cancer would require large and very long‐term studies, which are unlikely to be undertaken. The progression of HPV infection to invasive cancer is thought to take a minimum of 10 years (IARC 2007). Although CIN can regress, from historical data, it has been estimated that CIN3 has a probability of progressing to invasive cancer of 12% to 30%, whereas for CIN2 this probability is substantially lower (McCredie 2008; Ostor 1993).

The recognition of the strong causal association between HPV infection and cervical cancer led to the development of molecular HPV assays to detect cervical cancer precursors (Iftner 2003), and of vaccines that prevent HPV infection (prophylactic vaccines) or that aim to treat present HPV infection or HPV‐induced lesions (therapeutic vaccines) (Frazer 2004; Galloway 2003; Schneider 2003). Therapeutic vaccines are still in early experimental phases and are not further considered in this review.

Throughout this review, we will use the 2001 Bethesda System to define cytologically‐defined neoplastic lesions of the cervical epithelium (Solomon 2002) and the CIN nomenclature to define histologically‐confirmed CIN (Richart 1973).

Description of the intervention

The intervention evaluated in this review is prophylactic vaccination against the most carcinogenic HPV types. Prophylactic HPV vaccines are composed of virus‐like particles (VLPs) of the L1 protein, which is the major protein of the capsid (shell) of the HPV virus. VLPs, do not contain viral DNA, and so are incapable of causing an active infection.

This review addresses evidence of three prophylactic HPV vaccines that have been clinically evaluated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs): a monovalent HPV16 vaccine (manufactured by Merck, Sharpe & Dome (Merck), Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA); a quadrivalent vaccine, containing the L1 protein of HPV6, HPV11, HPV16 and HPV18 (Gardasil®, produced by the same manufacturer as the monovalent vaccine); and a bivalent vaccine containing L1 of HPV types 16 and 18 (Cervarix®, produced by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Rixensart, Belgium). The vaccines produced by Merck contain amorphous aluminium hydroxyphosphate sulphate as an adjuvant, whereas the GSK vaccine contains aluminium salt and AS04 or monophosphoryl lipid A, which is an immunostimulating molecule (WHO 2009). Recently, a nona‐valent vaccine targeting nine HPV types (HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 52 and 58) has been developed by Merck. We did not include the nona‐valent vaccine in the current review, since the randomised trials assessing the efficacy of the nona‐valent vaccine did not incorporate an arm with a non‐HPV vaccine control, Nevertheless, data regarding the nona‐valent vaccine are included in the Discussion. More details about the prophylactic HPV vaccines used are described in Appendix 2.

How the intervention might work

Animal experiments have shown that neutralising antibodies, elicited by vaccination with papillomavirus VLPs, prevent type‐specific infection and subsequent development of lesions after viral challenge (Breitburd 1995; Ghim 2000; Stanley 2006). Vaccination by intramuscular injection of L1 VLPs in humans has been demonstrated to be highly immunogenic in phase I trials, which means that they induce high titres of anti‐HPV antibodies in serum which are considerably higher than after natural infection. (Ault 2004; Brown 2001; Evans 2001; Harro 2001). Serum anti‐L1 antibodies can transudate to the mucosa (cervical or other sites) where new HPV infection is impeded through virus‐neutralisation (Stanley 2012). Prophylactic HPV vaccines may also induce specific memory B‐lymphocytes which play a role in long‐term humoral immunity (Giannini 2006). Anti‐HPV antibodies do not trigger the elimination of an existing HPV infection. Cell‐mediated immunity is required for viral clearance and regression of CIN lesions (Stanley 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Several phase II and III studies have been conducted to date and numerous reviews have tried to summarise the results (Ault 2007; Arbyn 2007; Harper 2009; Initiative 2009; Kahn 2009; Kjaer 2009; Koutsky 2006; Lu 2011; Medeiros 2009; Rambout 2007; Szarewski 2010). However, none of the reviews combined information on all the available endpoints. Our purpose was to pool efficacy outcomes only when outcomes were similarly defined, taking the timing of follow‐up into account. This review is also important since it provides a template for reporting future results of prophylactic vaccination trials according to the different outcomes (infections or cervical precancerous lesions, either associated with infection with vaccine types or irrespective of HPV infection) for different exposure groups (defined essentially by absence of hrHPV, absence of the HPV types included in the vaccine, or regardless of HPV infection at enrolment). Particular effort was undertaken to assess severe adverse effects in order to inform health professionals, stakeholders, adolescent girls and women, not only about the potential beneficial effects of HPV vaccines but also about possible harms.

Objectives

To evaluate the harms and protection of prophylactic human papillomaviruses (HPV) vaccines against cervical precancer and HPV16/18 infection in adolescent girls and women.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered only phase II and phase III randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included studies enrolling female participants, without any age restriction, distinguishing:

female participants with no evidence of baseline infection with high‐risk human papillomaviruses (hrHPV) types (this group reflects the first target of basic vaccination programmes, i.e. girls before onset of sexual activity);

female participants with no evidence of baseline infection with HPV types included in the vaccines (per protocol population);

all female participants regardless of baseline infection with HPV (this group reflects the target of catch‐up vaccination programs, adolescents or young adult women aged 15 to 26 years, where a considerable proportion may already have been exposed to HPV infection).

The distinction of different participant categories by HPV status at enrolment is essential, since the trial outcomes are expected to differ in women who are already infected with HPV types included in the vaccine and those who are not infected, Further distinction was made by:

broad age group (adolescents and young adult women, aged 15 to 26 years) and mid‐adult women (25 to 45 years);

number of received doses: three doses in agreement with the trial protocol, at least one dose, and fewer than three doses (the latter analysis being a post‐hoc assessment);

type of vaccine received (mono‐, bi‐ or quadrivalent vaccine).

Studies with male participants or special target groups such as immunocompromised patients were not included. However, trials enrolling both female and male participants were potentially eligible under the condition that separate outcomes for female participants were reported or could be obtained from the authors.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Vaccination with prophylactic HPV vaccines containing virus‐like particles composed of the L1 capsid protein of HPV16 (monovalent vaccine), HPV16 and HPV18 (bivalent vaccine), or HPV6, HPV11, HPV16 and HPV18 (quadrivalent vaccine) (see Appendix 2). All vaccines were administered by intramuscular injection over a period of six months. The monovalent and quadrivalent vaccines were injected at zero, two and six months, whereas the bivalent vaccine was administered at zero, one and six months.

Comparison

Administration of placebo containing no active product or only the adjuvant of the HPV vaccine, without L1 VLP, or another non‐HPV vaccine.

In head‐to‐head trials comparing directly the bivalent with the quadrivalent vaccine, participants who received the bivalent vaccine constituted the experimental group and participants who received the quadrivalent vaccine were considered as the comparison group.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Histologically‐confirmed high‐grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2, CIN3 and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS)) or worse, associated with the HPV types included in the vaccine or any lesions irrespective of HPV type. Association between HPV types and a diagnosed lesion means that the particular type or types have been detected in that lesion. These primary outcomes were judged by WHO to be adequate endpoints (Pagliusi 2004).

Invasive cervical cancer.

Safety/occurrence of adverse effects:

local adverse effects (redness, swelling, pain, itching at the injection site);

mild systemic effects;

serious systemic effects;

mortality;

pregnancy outcomes observed during the trials, in particular occurrence of congenital anomalies.

Secondary outcomes

Incident infection with vaccine HPV types (HPV16 and HPV18, jointly; and HPV6, HPV11, HPV16 and HPV18 jointly).

Persistent infection (persisting during at least six months or at least 12 months) with vaccine HPV types.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for papers in all languages and translations were undertaken, if necessary.

Electronic searches

We retrieved published studies from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL the Cochrane Library), MEDLINE and Embase.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2002 to 2017, Issue 5). MEDLINE (2002 to June Week 1 2017). Embase (2002 to 2017 week 24).

The search strategies for MEDLINE, CENTRAL and Embase are listed in Appendix 3, Appendix 4 and Appendix 5.

The search string for MEDLINE was saved in My NCBI, an electronic search tool developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at the National Library of Medicine, which saves searches and automatically retrieves newer references not picked‐up at previous searches. An auto‐alert was set up in Embase.

The 'related articles' feature in PubMed was used, departing from the original included studies; similarly, Scopus was used to retrieve articles which cite the originally included studies.

We searched databases were searched from 2002 (the year of publication of the results of the first phase II trial) until June 2017.

Searching other resources

Registries of randomised trials

We searched the following registries to identify unpublished or ongoing trials: www.clinicaltrials.gov, www.isrctn.com, and www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials.

Data on adverse effects published in the peer‐reviewed literature were complemented by searches in wwww.clinicaltrials.gov for the quadrivalent vaccine and on http://www.gsk‐clinicalstudyregister.com/ for the bivalent vaccine. We collected data for the outcomes of serious adverse events, all‐cause mortality and pregnancy outcomes from these sources and compared them with data extracted from the primary trial publications.

International public health organisations

We contacted international public health organisations that have investigated questions on HPV vaccine efficacy and safety or that have formulated recommendations on the use of HPV vaccines, to retrieve key documents. Concerned organisations included: the World Health Organization (WHO, Geneva), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta), the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC, Stockholm), and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC, Lyon).

Handsearching

We handsearched the citation lists of included studies.

In addition, we searched the abstracts of the latest conferences of relevant scientific societies related to vaccination, virology (in particular the International Papillomavirus Society), paediatrics, and gynaecology for new or pending information not yet published in peer‐reviewed journals.

Correspondence

We contacted study authors to request results on effects separated by gender, if the reports only contained data combined for both genders.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to a bibliographic database stored in Reference Manager. We added any references obtained by handsearching and removed any duplicates.

We (MA, CS and LX) independently verified inclusion and exclusion of eligible studies and discussed any disagreements. In case of doubt, the full‐text report was read. If no consensus could be reached, review author PMH was consulted. We documented reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

For included studies, we extracted the following study characteristics and outcome data.

Study identification: first author, year of publication, journal, trial number.

Geographical area where the study was conducted.

Period when study was conducted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Characteristics of included participants (total number enrolled, age, number of previous sexual partners).

Initial HPV status (presence or absence of hrHPV DNA; presence or absence of DNA of the vaccine HPV types; serological status (presence of antibodies against vaccine HPV types) at enrolment). Differences in efficacy outcomes by initial HPV status will reflect protection in women or girls previously exposed, or not exposed to prior HPV infection.

-

Study design:

phase of the randomised trial (II or III);

type of vaccine evaluated (monovalent, bivalent, or quadrivalent);

control group: type of placebo or other vaccine administered;

time points (mean duration of follow‐up after first dose) at which outcomes were collected and reported;

study size at enrolment and at subsequent time points of follow‐up;

number of doses received;

scheduling of screening tests (HPV tests, cytology);

diagnostic algorithms used to confirm outcomes;

definition of study groups on which per‐protocol and intention‐to‐treat analyses were applied;

risk of bias in study design (see below: Assessment of risk of bias in included studies).

-

Outcomes, subdivided by (i) the association with vaccine HPV types and (ii) irrespective of HPV types:

outcome definition (including diagnostic criteria and assays);

results: number of participants allocated to each intervention group; number of missing values and absolute values required to compute effect measures (see Types of outcome measures);

data for the efficacy outcomes and short‐term adverse events relating to the injection procedures were collected from primary trial publications. For outcomes relating to serious adverse events, all‐cause mortality and pregnancy outcomes, data were cross‐checked between trial registries, study results websites, correspondence with investigators and the primary trial reports. The primary analysis used the data derived from the reports with the longest follow‐up time. A sensitivity analysis on serious adverse effects and mortality was restricted to data derived from reports published in peer‐reviewed journals.

Involvement of manufacturers.

We extracted data on outcomes as follows.

For dichotomous outcomes, we extracted the number of participants in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of participants assessed at endpoint in order to estimate a risk ratio (RR) or risk difference (RD). Where possible, we also extracted the number of person‐years at risk in order to compute incidence rates and incidence rate ratios or differences.

We (MA, CS until 2011 and LX from 2012) independently extracted data onto a data abstraction form specially designed for the review. Differences between review authors were resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (PMH) if necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in included RCTs using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool and the criteria specified in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). This included assessment of:

the method used for randomisation to generate the sequence of participants allocated to the treatment arms;

allocation concealment;

blinding (of participants, healthcare providers;

blinding of outcome assessment;

reporting of incomplete outcome data for each outcome;

selective reporting of outcomes.

We (MA, CS and LX) independently applied the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool and differences were resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (PMH). Results were presented in both a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary. We interpreted the results of meta‐analyses in the light of the findings with respect to risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We computed risk ratios (RR) from the ratio of proportions or rates of events among vaccine recipients versus placebo recipients. In the literature, protection against HPV infection or cervical precancer is usually presented as vaccine efficacy (VE), VE = (1‐RR)*100. However, pooling of VE is not supported by the Review Manager (RevMan) software (Review Manager 2014). Where perfect efficacy corresponds with VE = 100%, the corresponding RR = 0; VE = 0% or RR = 1 means absence of protection. Negative VE or RR exceeding unity reflect adverse protection (vaccinated participants are more at risk than non‐vaccinated participants). When the 95% confidence interval contains unity, the protective effect is statistically insignificant. The number of participants needed to vaccinate (NNV) to avoid one outcome event was computed from the risk difference (NNV = 1/RD).

To show vaccination effects at population level, Cates plots were drawn, showing effects in 1000 vaccinated and 1000 non‐vaccinated women (Cates 2015).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors or data owners to request data on the outcomes, separated by gender, if the reports only contained data combined for both genders in trials where both women and men were enrolled. We did not impute missing outcome data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between studies by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between trials that could not be ascribed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003), by a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity (Deeks 2001) and, if possible, by subgroup analyses. If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, we investigated and reported the possible reasons.

In order to avoid heterogeneity, we did not combine data series from participants with different baseline HPV status (presence of hrHPV DNA, presence of DNA of the HPV vaccine types). Age group and sexual history were investigated as potential sources that could explain possible heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to construct funnel plots and to perform regression tests to identify asymmetry in the meta‐analysis (Harbord 2009). However, since each meta‐analysis contained seven or fewer studies, this was not feasible. Instead, we performed meta‐regression to identify possible small‐study effects grouping studies in two categories: large (> = 3000 participants) and small (< 3000 participants).

Data synthesis

Random‐effects models with inverse variance weighting were applied using the RevMan 5 (DerSimonian 1986). From the pooled RR, VE was computed (VE = 1‐RR). Pooled risk differences were computed also for the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed separate analyses determined by the participant's HPV status as defined by the result of an HPV DNA tests at enrolment. Three groups were distinguished: a) initially hrHPV DNA negative, b) initially HPV16/18 DNA negative, and c) regardless of initial HPV DNA test results. Subgroup meta‐analyses were performed, if possible, using vaccine type and age group as a stratifying variable. We distinguished younger (15 to 26 years) from mid‐adult women (24 to 45 years), which were the two age groups assessed in the available randomised trials. If efficacy estimates were not significantly different by vaccine type, jointly pooled estimates were retained. Only when significant heterogeneity by vaccine types was noted, were separate efficacy estimates by vaccine type pooled. We used meta‐regression to investigate sources of heterogeneity such as serological status, study design items, study size and sexual history (Sharp 1998; Thompson 1999). The log relative risk (vaccinated versus placebo recipients) was used as the dependent variable. The antilog of coefficients of the meta‐regression yielded relative risk ratios (RRR). 95% confidence intervals around the RRR excluding unity indicated a statistically influential factor.

We assessed the influence of covariates, which were not defined uniformly throughout the trials, by Poisson regression in each trial concerned, separately and using person‐years at risk as an offset.

A posteriori analysis was performed to investigate vaccine efficacy in women who had received fewer than three doses of vaccine, by subtraction of the number of events and total number of participants who had received three doses from those who had received at least one dose. This was the only possible approach, since outcomes stratified by number of doses received, were not usually reported in the published papers.

Sensitivity analysis

We assessed the robustness of data collected for serious adverse events, all‐cause mortality and pregnancy outcomes based on the source of data. The primary analysis for these outcomes included data that we considered to represent the most complete follow‐up. As a sensitivity analysis we used data for these same outcomes that had only been reported in the published trial reports.

'Summary of findings' tables

We created 'Summary of findings' tables for three populations of interest.

Adolescent girls and women who were negative for hrHPV DNA at baseline

Adolescent girls and women who were negative for HPV16/18 DNA at baseline

Adolescent girls and women regardless of HPV DNA status at baseline

We included findings for the following outcomes for each population.

Cervical cancer

CIN2+ or CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18; any CIN2+ or CIN3+, irrespective of HPV types

AIS associated with HPV/16/18; any AIS irrespective of HPV types

All‐cause mortality (in all enrolled women)

Serious adverse events (in all enrolled women)

We included a fourth table summarising pregnancy outcomes as follows.

Spontaneous abortion/miscarriage

Elective termination/induced abortion

Spontaneous miscarriage

Babies born with congenital malformations

Since only randomised clinical trials were included in the review, the rating for each outcome started as high‐quality evidence and was downgraded for the following considerations according to GRADE guidance (Higgins 2011b).

Risk of bias

Inconsistency (both quantitative and qualitative)

Imprecision (relating to the width of the 95% confidence interval and number of participants in the analysis)

Indirectness

Publication bias

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

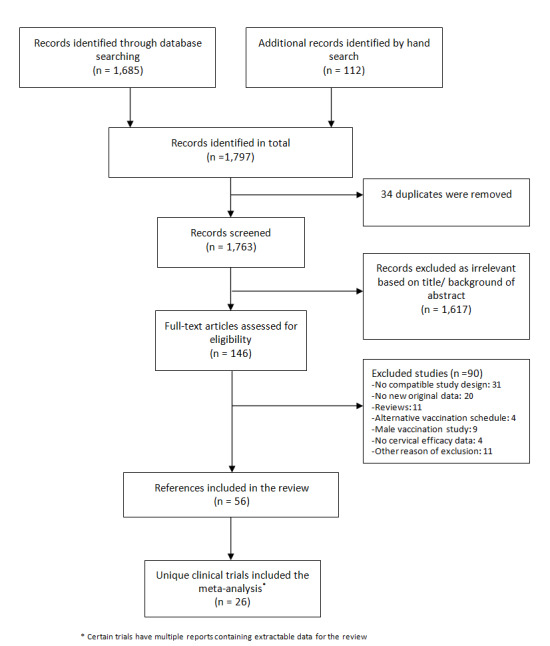

The search in MEDLINE, Embase and CENTRAL, conducted after the publication of the updated protocol (Arbyn 2013), was updated up on 15 June 2017, which resulted in 1685 records and was completed with 112 citations of previously published reviews retrieved from Scopus and reports from the personal CERVIX bibliographic database, yielding 1797 records. After eliminating 34 duplicates, 1763 references were considered from which 1617 could be excluded based on title or objectives described in the abstract. Full reading of the abstracts and materials of 146 papers allowed exclusion of 90 reports. Finally, 56 relevant references describing characteristics and results of 26 randomised trials were selected for this review (Characteristics of included studies). The retrieval and selection of studies is summarised in the PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1. In addition, we included two reports of pooled analyses of included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with original data (FUT I/II trials (ph3,4v); PATRICIA & CVT (ph3,2v)).

1.

Flow diagram summarising the retrieval, inclusion and exclusion of relevant reports of randomised trials assessing the safety and effects of prophylactic HPV vaccines.

Details about the completeness of publication of HPV vaccination trials, registered in www.clinicaltrials.gov, can be found in Appendix 6. No additional studies could be retrieved from www.isrctn.com or www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials.

Included studies

Twenty‐six randomised trials were identified that contained data on vaccine efficacy and/or safety, which all together enrolled 73,428 women. One trial (Phase2 trial (ph2,1v)) evaluated effects of a monovalent HPV16 vaccine, 18 trials evaluated the bivalent vaccine (African_2 country trial (ph3,2v); Chinese trial (ph3,2v)_ adolescent; Chinese trial (ph3,2v)_mid‐adult; Chinese trial (ph3,2v)_young; Co‐vaccination_dTpa_IPV trial (ph3,2v); Co‐vaccination_HAB trial (Ph3, 2v); Co‐vaccination_HepB trial (ph3, 2v); CVT (ph3,2v); Hong Kong trial (ph3,2v); Immunobridging(ph3,2v); Indian trial (ph3,2v); Japanese trial (ph2,2v); Korean trial (ph3,2v); Korean trial (ph3b,2v); Malaysian trial (ph3,2v); PATRICIA trial (ph3,2v); Phase2 trial (ph2,2v); VIVIANE trial (ph3,2v)) and seven others the quadrivalent vaccine (African_3 country trial (ph3,4v); FUTURE III trial (ph3,4v); FUTURE II trial (ph3,4v); FUTURE I trial (ph3,4v); Japanese trial (ph2,4v); Korean trial (ph2,4v); Phase2 trial (ph2,4v)). Six studies were phase II trials and 20 others were phase III trials. No phase I trials were included.

All trials were funded by the respective manufacturers of the vaccines, except one trial, which was financed by the National Cancer Instituite (CVT (ph3,2v)). The study size varied between 98 (African_3 country trial (ph3,4v)) and 18,644 (PATRICIA trial (ph3,2v)). The smaller studies (<1000) essentially assessed safety and immunogenicity (not assessed in this review) or only addressed protection against infection with the HPV vaccine types, whereas the larger phase III trials assessed also protection against cervical precancer (CIN2+, CIN3+ and AIS+). A listing of the 26 studies ranked by valency of the vaccine, phase (II or III) and alphabetic order is provided in Table 5.

1. Listing of included trials.

Other characteristics which are not described in Characteristics of included studies, are presented in Appendix 7 and Appendix 8.

Excluded studies

A list of 90 excluded studies and reasons for exclusion can be found below (Characteristics of excluded studies). We excluded a Chinese study (Li 2012) and an immuno‐bridging study (Reisinger 2007), which contained safety and immunogenicity data reported jointly for men and women. We sent a request to the authors for separate data for women but we did not receive a reply from the former and an answer that gender‐separated data were not available from the latter.

Risk of bias in included studies

The assessment of the risk of possible bias present in the selected studies according to the six criteria incorporated in Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials (Higgins 2011b) is shown in Characteristics of included studies.

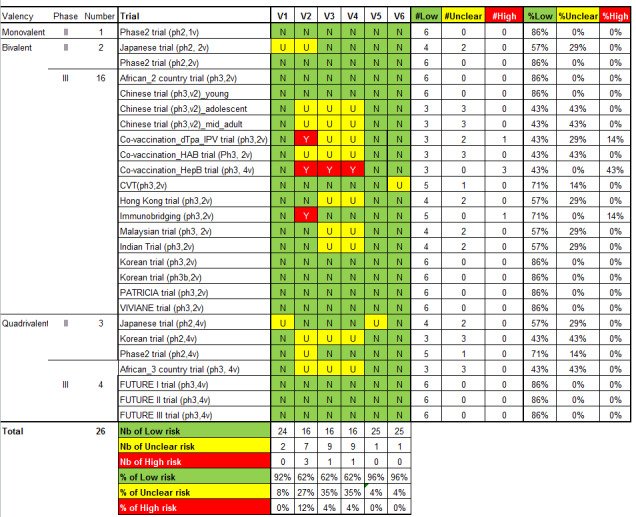

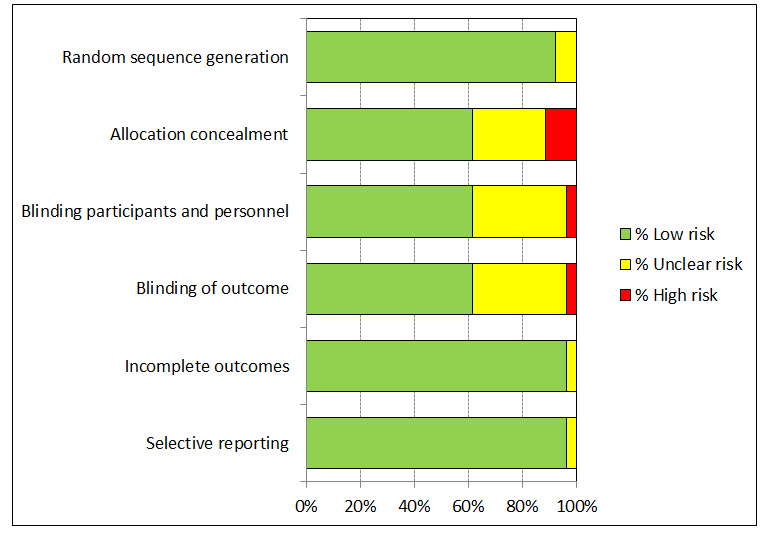

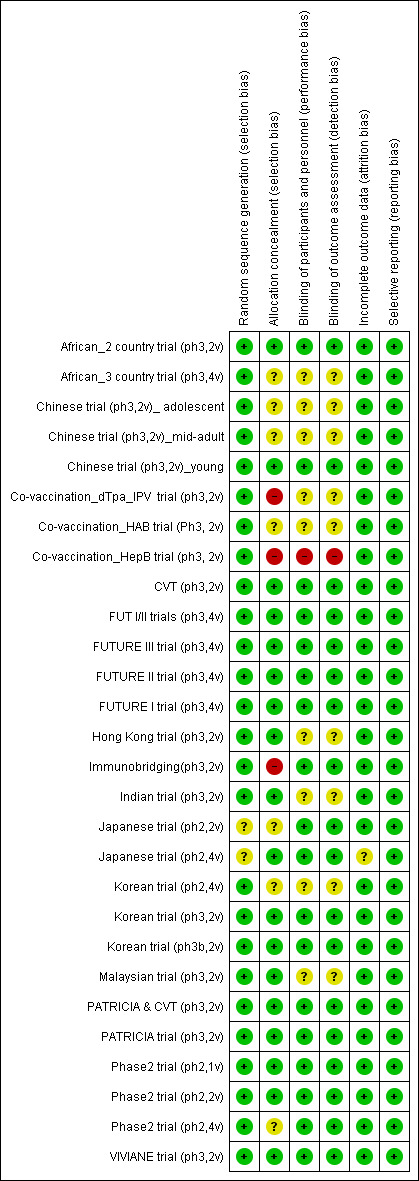

We judged the risk of bias related to the six Cochrane criteria as low in most of the included trials (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). We judged the generation of a random sequence as adequate in 24/26 trials ( = 92%). In two studies, the system used for randomisation was insufficiently described (unclear risk of bias) (Japanese trial (ph2,4v); Japanese trial (ph2,2v)).

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study. V1 = Random sequence generation; V2 = Allocation concealment; V3 = Blinding participants & personnel; V4 = Blinding of outcome assessment; V5 = Incomplete outcomes; V6 = Selective reporting.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

The allocation of participants to the vaccine or placebo arm was clearly concealed in 16/26 (62%) trials. In three studies, randomisation was by design not concealed (Co‐vaccination_dTpa_IPV trial (ph3,2v)); Co‐vaccination_HepB trial (ph3, 2v); Immunobridging(ph3,2v)). These studies did not assess efficacy but compared immunogenicity and safety of HPV vaccines with other vaccines or combination of HPV vaccine and other vaccines that were visually distinguishable. Concealment of allocation was unclear in seven studies (African_3 country trial (ph3,4v); Chinese trial (ph3,2v)_ adolescent; Chinese trial (ph3,2v)_mid‐adult; Japanese trial (ph2,2v); Korean trial (ph2,4v); Phase2 trial (ph2,4v);Co‐vaccination_HAB trial (Ph3, 2v) ).

Blinding of study participants and medical personnel and blind assessment of outcomes were assured in 16 trials but were not clearly documented in nine trials (9/ 26 = 35% unclear risk). One trial assessing immunogenicity and safety of HPV vaccine only versus vaccination of HPV vaccine with other vaccines was by design unblinded (Co‐vaccination_HepB trial (ph3, 2v)). Drop out of enrolled participants, who did not follow the foreseen vaccination schedule, occurred in all trials, but the reasons for exclusion were well described in 25/26 (96%) and outcomes were presented separately for restricted per‐protocol groups and larger intention‐to‐treat groups in nearly all trials with one exception. In the Japanese trial (ph2,4v) only per‐protocol results were presented. All intended outcomes were reported according to pre‐published registered protocols in all included trials.

We did not judge any of the included trials assessing efficacy outcomes as having a high risk of bias. In eight of the included efficacy trials were considered to be at low risk of bias.

Only one study (CVT (ph3,2v)) was funded and conducted by an independent research institution.

Whether involvement of industry or other quality criteria influenced study outcomes will be explored below (Results, section 9.3).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. HPV vaccine effects on cervical lesions in adolescent girls and women negative for hrHPV DNA at baseline.

| HPV vaccine effects on cervical lesions in adolescent girls and women who are hrHPV DNA negative at baseline | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adolescent girls and women aged 15 to 26 years who are hrHPV negative before vaccination Setting: Europe, Asia Pacific countries, South & North America Intervention: HPV vaccines (at least one dose of bivalent or quadrivalent vaccines) Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with HPV vaccination1 | |||||

| Cervical cancer ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18. Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years |

164 per 10,000 | 2 per 10,000 (0 to 8) | RR 0.01 (0.00 to 0.05) | 23,676 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18 Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years |

70 per 10,000 | 0 per 10,000 (0 to 7) | RR 0.01 (0.00 to 0.10) | 20,214 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Continuity correction |

| AIS associated with HPV16/18 Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years |

9 per 10,000 | 0 per 10,000 (0 to 7) | RR 0.10 (0.01 to 0.82) | 20,214 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Continuity correction |

| Any CIN2+ irrespective of HPV type, bivalent or quadrivalent vaccine Follow‐up: 2 to 6 years |

287 per 10,000 | 106 per 10,000 (72 to 158) | RR 0.37 (0.25 to 0.55) | 25,180 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Substantial subgroup heterogeneity was observed (I2= 84.3%) for bi‐ and quadrivalent vaccines. So results are reported separately for the 2 vaccines (see next 2 rows). |

| Any CIN2+ irrespective of HPV type Follow‐up (bivalent): 3.5 to 6 years Follow‐up (quadrivalent): 3.5 years |

Bivalent vaccine | RR 0.33 (0.25 to 0.43) |

15,884 (4 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 285 per 10,000 | 94 per 10,000 (71 to 122) |

|||||

| Quadrivalent vaccine | RR 0.57 (0.44 to 0.76) |

9296 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE3 | |||

| 291 per 10,000 | 166 per 10,000 (128 to 221) |

|||||

| Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV type, bivalent or quadrivalent vaccine Follow‐up: 3.5 to 4 years |

109 per 10,000 | 23 per 10,000 (4 to 120) | RR 0.21 (0.04 to 1.10) | 20,719 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | Substantial subgroup heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 84.3%) for bi‐ and quadrivalent vaccines. So results are reported separately for the 2 vaccines (see next 2 rows). |

| Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV type Follow‐up (bivalent): 4 years Follow‐up (quadrivalent): 3.5 years |

Bivalent vaccine | RR 0.08 (0.03 to 0.23) |

11,423 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 81 per 10,000 | 6 per 10,000 (3 to 19) |

|||||

| Quadrivalent vaccine | RR 0.54 (0.36 to 0.82) |

9296 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE3 | |||

| 143 per 10,000 | 77 per 10,000 (51 to 117 ) |

|||||

| Any AIS irrespective of HPV type Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years | 10 per 10,000 | 0 per 10,000 (0 to 8) | RR 0.10 (0.01 to 0.76) | 20,214 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Continuity correction |

| 1The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). When risk in vaccine group is zero, the 95% CI is computed using an exact binomial method. AIS: adenocarcinoma in situ; CI: Confidence interval; CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Assumed risk calculated from the sum of control group event rates.

2 Downgraded due to serious imprecision in effect estimate (width 95% CI around RR > 0.6).

3 Downgraded one level due to serious imprecision. Few events observed in the two studies (9 in placebo arms and 0 in vaccination arms for the outcome of AIS HPV16/18 and 7 in placebo arms and 0 in vaccination arms for outcome of AIS of any type).

Summary of findings 2. HPV vaccine effects on cervical lesions in adolescent girls and women negative for HPV16/18 DNA at baseline.

| HPV vaccine effects on cervical lesions in adolescent girls and women negative for HPV16/18 DNA at baseline | ||||||

| Patient or population: adolescent girls and women aged 15 to 45 years who were HPV16/18 negative before vaccination Setting: Europe, Asia Pacific countries, South & North America Intervention: HPV vaccines (at least one dose of bivalent or quadrivalent vaccines) Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with HPV vaccination1 | |||||

| Cervical cancer ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18 Follow‐up (age 15 to 26 years): 1 to 8.5 years Follow‐up (age 24 to 45 years): 4 to 6 years |

15 to 26 years | RR 0.05 (0.03 to 0.10) | 34,478 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 113 per 10,000 | 6 per 10,000 (3 to 11) | |||||

| 24 to 45 years | RR 0.30 (0.11 to 0.81) |

7552 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 |

|||

| 45 per 10,000 | 14 per 10,000 (5 to 37) |

|||||

| CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18 (age 15 to 26 years) Follow‐up: 3 years |

57 per 10,000 | 3 per 10,000 (1 to 8) |

RR 0.05 (0.02 to 0.14) |

33,199 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| AIS associated with HPV16/18 or 6/11/16/18 (age 15 to 26 years) Follow‐up: 3 years |

12 per 10,000 | 0 per 10,000 (0 to 8) | RR 0.09 (0.01 to 0.72) | 17,079 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 |

Continuity correction |

| Any CIN2+ irrespective of HPV type (age 15 to 26 years) Follow‐up: 2 to 6.5 years |

231 per 10,000 | 95 per 10,000 (74 to 120) | RR 0.41 (0.32 to 0.52) | 19,143 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV type ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Any AIS irrespective of HPV type ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

| 1The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Exception: when risk in vaccine group is zero, the 95% CI is computed using an exact binomial method.. AIS: adenocarcinoma in situ; CI: Confidence interval; CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Assumed risk calculated from the sum of control group event rates.

2 Downgraded due to serious imprecision in effect estimate (width 95% CI around RR > 0.6).

Summary of findings 3. HPV vaccine effects in adolescent girls and women regardless of HPV DNA status at baseline.

| HPV vaccine effects on cervical lesions in adolescent girls and women unselected for HPV DNA status at baseline | ||||||

| Patient or population: adolescent girls and women aged 15 to 45 years regardless of HPV DNA status at baseline Setting: Europe, Asia Pacific countries, South & North America and Africa Intervention: HPV vaccines (at least one dose of bivalent or quadrivalent vaccines) Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with HPV vaccination1 | |||||

| Cervical cancer ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18 Follow‐up (age 15 to 26 years): 3.5 to 8.5 years Follow‐up (age 24 to 45 years): 3.5 years |

15 to 26 years | RR 0.46 (0.37 to 0.57 |

34,852 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 341 per 10,000 | 157 per 10,000 (126 to 194) | |||||

| 24 to 45 years | RR 0.74 (0.52 to 1.05) |

9200 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | |||

| 145 per 10,000 | 107 per 10,000 (76 to 152) |

|||||

| CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18 Follow‐up: 3.5 years |

165 per 10,000 | 91 per 10,000 (74 to 127) |

RR 0.55 (0.45 to 0.67) |

34,562 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Adeno carcinoma in situ (AIS) associated with HPV16/18 Follow‐up: 3.5 years |

14 per 10,000 | 5 per 10,000 (3 to 11) | RR 0.36 (0.17 to 0.78) | 34,562 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Any CIN2+ irrespective of HPV type Follow‐up (age 15 to 26 years): 3.5 to 8.5 years Follow‐up (age 24 to 45 years): 3.5 to 6 years |

15 to 26 years | RR 0.70 (0.58 to 0.85) | 35,779 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 559 per 10,000 | 391 per 10,000 (324 to 475) | |||||

| 24 to 45 years | RR 1.04 (0.83 to 1.30) | 9287 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | |||

| 343 per 10,000 | 356 per 10,000 (284 to 445) | |||||

| Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV type (age 15 to 26 years) Follow‐up: 3.5 to 4 years |

266 per 10,000 | 178 per 10,000 (231 to 247) |

RR 0.67 (0.49 to 0.93) |

35,489 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE | Substantial subgroup heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 84.3%) for bivalent and quadrivalent vaccines. So results are reported separately for two vaccines. |

| Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV type (age 15 to 26 years), Follow‐up (bivalent): 3.5 to 4 years Follow‐up (quadrivalent): 3.5 years |

Bivalent vaccine | RR 0.55 (0.43 to 0.71) |

18,329 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 188 per 10,000 | 104 per 10,000 (81 to 134) |

|||||

| Quadrivalent vaccine | 0.81 (0.69 to 0.96) |

17,160 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | |||

| 349 per 10,000 | 283 per 10,000 (241 to 335) |

|||||

| Any AIS irrespective of HPV type (age 15 to 26 years) Follow‐up: 3.5 years |

17 per 10,000 | 5 per 10,000 (3 to 11) | RR 0.32 (0.15 to 0.67) | 34,562 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 6 months to 7 years |

669 per 10,000 | 656 per 10,000 (616 to 703) | RR 0.98 (0.92 to 1.05) | 71,597 (23 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Deaths Follow‐up: 7 months to 10 years. Most of the information in the analysis comes from studies with follow‐up ranging from 5‐10 years. |

11 per 10,000 | 14 per 10,000 (9 to 22) | RR 1.29 (0.85 to 1.98) | 71,176 (23 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 5 | Older women had higher fatality rate (RR 2.36, 95% CI 1.10 to 5.03). Assessment of the deaths in the studies has not been able to identify a pattern in the cause or timing of death. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AIS: adenocarcinoma in situ; CI: Confidence interval; CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Assumed risk calculated from the sum of control group event rates for all outcomes unless otherwise stated.

2 Downgraded due to serious imprecision. Confidence interval is wide and includes large decrease and small increase in lesions with vaccination group in the older age group.

3 Downgraded one level due to serious inconsistency. Reduction in lesions was greater in younger women than in older women (RR 0.46 in 15 to 26 years versus RR 0.74 in 24 to 45 years; P = 0.02 for interaction).

4 Downgraded one level due to serious imprecision. Confidence interval includes potentially meaningful increase in risk of mortality.

5 Downgraded one level due to serious inconsistency. Despite limited evidence of statistical variation, sub grouping studies by age showed higher fatality rate with vaccines in older age group. There is no clear pattern in causes or timing of deaths.

Summary of findings 4. HPV vaccine effects on pregnancy outcomes.

| HPV vaccine adverse pregnancy outcomes (regardless of DNA status and age) | ||||||

| Patient or population: adolescent girls and women aged 15 to 45 years who became pregnant during the study Setting: Europe, Asia Pacific, North, Central and South America Intervention: HPV vaccines (bivalent or quadrivalent vaccines) Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with HPV vaccines | |||||

| Spontaneous abortion/miscarriage Follow‐up: 1 to 7 years |

Study population | RR 0.88 (0.68 to 1.14) | 8618 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 1618 per 10,000 | 1,424 per 10,000 (1,100 to 1844) | |||||

| Elective termination/induced abortion Follow‐up: 1 to 7 years |

Study population | RR 0.90 (0.80 to 1.02) | 10,909 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 1 | ||

| 931 per 10,000 | 838 per 10,000 (745 to 950) | |||||

| Stillbirth Follow‐up: 1 to 3.5 years |

Study population | RR 1.12 (0.68 to 1.83) | 8754 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | ||

| 70 per 10,000 | 78 per 10,000 (48 to 128) | |||||

| Babies born with congenital malformations Follow‐up: 3 to 7 years |

Study population | RR 1.22 (0.88 to 1.69) | 9252 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | ||

| 205 per 10,000 | 250 per 10,000 (180 to 346) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Confidence interval rules out an increased risk of termination so there is no downgrade for imprecision.

2 Downgraded one level due to serious imprecision. Confidence intervals for both outcomes include meaningful increase and reduction in risk of stillbirth or abnormal infants following vaccination.

The duration of follow‐up post vaccination in the studies was too short to show effects on cervical cancer outcomes. The presentation of the results on vaccine efficacy focuses on protection against precancerous cervical lesions and of HPV16/18 infection. They are organised according to the following features (see Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 6):

2. Results of all the efficacy outcomes.

| Outcomes and exposure subgroups | Absolute risk / per 10,000 | Relative risk (95% CI) |

Vaccine efficacy (95% CI) |

Risk difference/ per 10,000 (95% CI) |

No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE)* | |

| Placebo | Vaccinated | ||||||

| 1. High‐grade cervical lesions in women who were hrHPV DNA negative at baseline | |||||||

| Analysis 1.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 164 | 2 |

0.01 (0.00 to 0.05) |

99% (95% to 100%) |

162 (157 to 164) |

23,676 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 1.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 197 | 2 |

0.01 (0.00 to 0.09) |

99% (91% to 100%) |

195 (179 to 197) |

9296 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 1.3 CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 70 | 0* |

0.01 (0.00 to 0.10) |

99% (90% to 100%) |

70 (63 to 70) |

20,214 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 1.4 CIN3+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 94 | 0* |

0.01 (0.00 to 0.18) |

99% (82% to 100%) |

94 (77 to 94) |

9296 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 1.5 AIS associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 9 | 0* |

0.10 (0.01 to 0.82) |

90% (18% to 99%) |

9 (2 to 9) |

20,214 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 1.6 AIS associated with HPV6/11/16/18m at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 6 | 0* |

0.14 (0.01 to 2.8) |

86% (‐180% to 99%) |

6 (‐12 to 6) |

9296 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 1.7.1 Any CIN2+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose of the bivalent vaccine, age 15‐26 years | 285 | 94 |

0.33 (0.25 to 0.43) |

67% (57% to 75%) |

191 (163 to 214) |

15,884 (4 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 1.7.2 Any CIN2+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose of the quadrivalent vaccine, age 15‐26 years | 291 | 166 |

0.57 (0.44 to 0.76) |

43% (24 to 56%) |

125 (70 to 163) |

9296 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 1.8.1 Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose of the bivalent vaccine, age 15‐26 years | 81 | 6 |

0.08 (0.03 to 0.23) |

92% (77% to 97%) |

74 (62 to 78) |

11,423 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 1.8.2 Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose of the quadrivalent vaccine, age 15‐26 years | 143 | 77 |

0.54 (0.36 to 0.82) |

46% (17% to 64%) |

66 (26 to 92) |

9296 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 1.9 Any AIS irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose | 10 | 0* |

0.10 (0.01 to 0.76) |

90% (24% to 99%) |

10 (2 to 10) |

20,214 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| 2. High‐grade cervical lesions in women who were HPV16/18 negative at baseline | |||||||

| Analysis 2.1.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 74 | 5 |

0.07 (0.03 to 0.15) |

93% (85% to 97%) |

69 (63 to 72) |

36,579 (6 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 2.1.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, 3 doses, 24‐45 years | 36 | 6 |

0.16 (0.04 to 0.74) |

84% (26% to 96%) |

30 (9 to 34) |

6797 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 2.2.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, 15‐26 years | 113 | 6 |

0.05 (0.03 to 0.10) |

95% (90% to 97%) |

107 (102 to 110) |

34,478 (6 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 2.2.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 24‐45 years | 45 | 14 |

0.30 (0.11 to 0.81) |

70% (19% to 89%) |

32 (9 to 40) |

7552 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 2.3.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, 1 or 2 doses, 15‐26 years*** | 436 | 44 |

0.10 (0.04 to 0.26) |

90% (74% to 96%) |

392 (323 to 418) |

2958 (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1$ |

| Analysis 2.3.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, 1 or 2 doses, age 24‐45 years*** | 134 | 82 |

0.61 (0.14 to 2.67) |

39% (‐167% to 86%) |

52 (‐2245 to 115) |

755 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1$,4 |

| Analysis 2.4 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, 3 doses, age 15‐45 years | 99 | 6 |

0.06 (0.01 to 0.61) |

94% (39% to 99%) |

93 (39 to 98) |

7664 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 2.4.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 142 | 0* | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.25) |

98% (75% to 100%) |

142 (93 to 190) |

4499 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 2.4.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, 3 doses, age 24‐45 years | 38 | 6 | 0.17 (0.02 to 1.39) |

83% (‐39% to 98%) |

32 (‐1 to 32) |

3165 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 |

| Analysis 2.5.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 160 | 0* |

0.01 (0.00 to 0.19) |

99% (81% to 100%) |

160 (130 to 159) |

5351 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 2.5.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, at least 1 dose, age 24‐45 years | 44 | 16 |

0.37 (0.10 to 1.41) |

63% (‐41% to 90%) |

28 (‐18 to 40) |

3629 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3,4 |

| Analysis 2.6 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, 1 or 2 doses, age 15‐45 years*** | 199 | 48 |

0.24 (0.01 to 5) |

76% (‐400% to 99%) |

151 (‐795 to 197) |

1316 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1$,4 |

| Analysis 2.6.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, 1 or 2 doses, age 15‐26 years*** | 258 | 0* | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.74) |

96% (26% to 100%)) |

258 (108 to 409) |

852 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1$,3,4 |

| Analysis 2.6.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, 1 or 2 doses, age 24‐45 years*** | 88 | 85 | 0.97 (0.14 to 6.80) |

3% (‐580% to 86%) |

3 (‐165 to 171) |

464 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1$,3,4 |

| Analysis 2.7 CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18, 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 40 | 3 |

0.07 (0.02 to 0.29) |

93% (71% to 98%) |

37 (28 to 39) |

29,720 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 2.8 CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 57 | 3 |

0.05 (0.02 to 0.14) |

95% (86% to 98%) |

54 (49 to 56) |

33,199 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 2.9 CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18, 1 or 2 doses, age 15‐26 years*** | 200 | 12 |

0.06 (0.01 to 0.24) |

94% (26% to 100%) |

188 (152 to 198) |

3479 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1$ |

| Analysis 2.10 AIS+ associated with HPV16/18, 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 8 | 0* |

0.12 (0.02 to 0.70) |

88% (36% to 99%) |

8 (2 to 8) |

29,707 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 2.11 AIS+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 12 | 0* |

0.09 (0.01 to 0.72) |

81% (28% to 99%) |

12 (3 to 12) |

17,079 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 2.12 AIS+ associated with HPV16/18 or HPV6/11/16/18, 1 or 2 doses, age 15‐26 years*** | 29 | 0* |

0.15 (0.01 to 2.97) |

85% (‐197% to 99%) |

29 (‐57 to 29) |

2015 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1$,4 |

| Analysis 2.13 CIN2+ irrespective of HPV types, 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 166 | 66 |

0.40 (0.25 to 0.64) |

60% (36% to 75%) |

99 (60 to 124) |

7320 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 2.14 CIN2+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 231 | 95 |

0.41 (0.32 to 0.52) |

58% (46% to 67%) |

136 (111 to 157) |

19,143 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 2.15 CIN2+ irrespective of HPV types, 1 or 2 doses, age 20‐25 years*** | 1000 | 710 |

0.71 (0.15 to 3.38) |

29% (‐238% to 85%) |

290 (‐2,380 to 850) |

34 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1$,3,4 |

| 3. High‐grade cervical lesions in all women regardless of HPV DNA status at baseline** | |||||||

| Analysis 3.1.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 341 | 157 |

0.46 (0.37 to 0.57) |

54% (43% to 63%) |

184 (147 to 215) |

34,852 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 3.1.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 24‐45 years | 157 | 116 |

0.74 (0.52 to 1.05) |

26% (‐5% to 48%) |

41 (‐8 to 75) |

9200 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 3.2.1 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 436 | 217 |

0.50 (0.42 to 0.59) |

50% (41% to 58%) |

219 (166 to 272) |

17,160 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 3.2.2 CIN2+ associated with HPV6/11/16/18, at least 1 dose, age 24‐45 years | 145 | 113 |

0.78 (0.44 to 1.37) |

22% (‐37% to 56%) |

143 (72 to 204 |

3723 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 3.3 CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 165 | 91 |

0.55 (0.43 to 0.68) |

74% (55% to 91%) |

74 (55 to 91) |

34,562 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 3.4 CIN3+ associated with HPV16/18, 1 or 2 doses, age 15‐26 years*** | 230 | 124 |

0.54 (0.43 to 0.68) |

46% (32% to 57%) |

106 (74 to 131) |

17,160 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

| Analysis 3.5 AIS associated with HPV16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 14 | 5 |

0.36 (0.17 to 0.78) |

64% (22% to 83%) |

9 (3 to 12) |

34,562 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 3.6 AIS associated with HPV6/11/16/18, at least 1 dose, age 15‐45 years | 15 | 6 |

0.40 (0.16 to 0.98) |

60% (2% to 84%) |

9 (0 to 13) |

20,830 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3,4 |

| Analysis 3.7.1 Any CIN2+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 559 | 391 |

0.70 (0.58 to 0.85) |

30% (15% to 42%) |

168 (84 to 235) |

35,779 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 3.7 2 Any CIN2+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose, age 24‐45 years | 342 | 356 |

1.04 (0.83 to 1.30) |

‐4% (‐30% to 17%) |

‐14 (‐103 to 58) |

9287 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 3.8 Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose, age 18‐26 years, bivalent vaccine | 188 | 103 |

0.55 (0.43 to 0.71) |

45% (29% to 57%) |

84 (54 to 1107) |

18,329 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 3.8 Any CIN3+ irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years, quadrivalent vaccine | 349 | 283 |

0.81 (0.69 to 0.96) |

19% (4% to 31%) |

66 (14 to 108) |

17,160 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 3.9 Any AIS irrespective of HPV types, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 17 | 5 |

0.32 (0.15 to 0.67) |

68% (33% to 0.85%) |

11 (6 to 14) |

34,562 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| 4. HPV16/18 infection in women who were hrHPV DNA negative at baseline | |||||||

| Analysis 4.1 Incident HPV16/18 infection, 3 doses, age 18‐26 years | 2,457 | 147 |

0.06 (0.02 to 0.20) |

94% (80% to 98%) |

2,310 (1,966 to 2,408) |

368 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 4.2 Persistent HPV16/18 infection(6M), 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 971 | 29 |

0.02 (0.00 to 0.35) |

97% (57% to 100%) |

942 (554 to 971) |

368 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 4.3 Persistent HPV16/18 infection(6M), at least 1 dose, age 18‐25 years | 96 | 7 |

0.07 (0.05 to 0.09) |

93% (81% to 95%) |

90 (88 to 91) |

10,826 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 4.4 Persistent HPV16/18 infection(12M), 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 571 | 23 |

0.04 (0.00 to 0.73) |

96% (27% to 100%) |

549 (154 to 571) |

368 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| Analysis 4.5 Persistent HPV16/18 infection(12M), at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 462 | 37 |

0.08 (0.05 to 0.12) |

92% (88% to 95%) |

425 (406 to 439) |

14,153 ( 2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| 5. HPV16/18 infection in women who were HPV16/18 negative at baseline | |||||||

| Analysis 5.1 Incident HPV16/18 infection, 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 474 | 81 |

0.17 (0.10 to 0.31) |

87% (78% to 92%) |

412 (369 to 436) |

8,034 (4 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 5.2 Incident HPV16/18 infection, at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 1,326 | 305 |

0.23 (0.14 to 0.37) |

81% (71% to 88%) |

1,074 (941 to 1,167) |

23,872 (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 5.3 Incident HPV16/18 infection, 1 or 2 dose, age 15‐26 years*** | 2,568 | 1207 |

0.47 (0.26 to 0.84) |

74% (31% to 90%) |

1,901 (796 to 2,311) |

331 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

| Analysis 5.4.1 Persistent HPV16/18 infection (6M), 3 doses, age 15‐26 years | 581 | 35 |

0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) |

94% (91% to 95%) |

546 (534 to 552) |

27,385 (6 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 5.4.2 Persistent HPV16/18 infection (6M), 3 doses, age 24‐45 years | 350 | 38 |

0.11 (0.06 to 0.20) |

89% (80% to 94%) |

311 (280 to 329) |

6728 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 |

| Analysis 5.5.1 Persistent HPV16/18 infection (6M), at least 1 dose, age 15‐26 years | 657 | 66 |

0.10 (0.08 to 0.13) |

90% (87% to 92%) |

591 (572 to 605) |

22,803 (4 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 5.5.2 Persistent HPV16/18 infection (6M), at least 1 dose, age 24‐45 years | 441 | 75 |

0.17 (0.10 to 0.29) |

83% (71% to 90%) |

366 (313 to 397) |

7520 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Analysis 5.6.1 Persistent HPV16/18 infection (6M), 1 or 2 doses, age 15‐26 years*** | 996 | 119 |

0.12 (0.03 to 0.42) |

88% (58% to 97%) |

876 (577 to 966) |