This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial compared mortality among suicidal adolescents who received a psychoeducational social support suicide prevention intervention with that among suicidal adolescents who received treatment as usual.

Key Points

Question

Is the Youth-Nominated Support Team Intervention for Suicidal Adolescents–Version II associated with reduced mortality across 11 to 14 years?

Findings

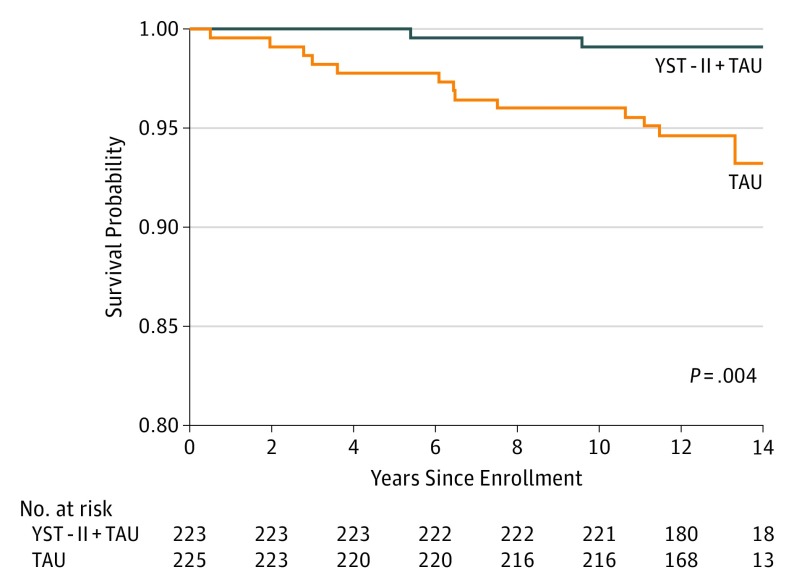

In this secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial that included 448 adolescents hospitalized for suicide risk, there were 2 deaths among adolescents in the Youth-Nominated Support Team at 11- to 14-year follow-up compared with 13 in the group allocated to treatment as usual, a significant difference.

Meaning

The implementation of the Youth-Nominated Support Team Intervention for Suicidal Adolescents–Version II with hospitalized suicidal adolescents may be associated with a reduced risk of mortality; however, findings are preliminary and in need of replication.

Abstract

Importance

The prevalence of suicide among adolescents is rising, yet little is known about effective interventions. To date, no intervention for suicidal adolescents has been shown to reduce mortality.

Objective

To determine whether the Youth-Nominated Support Team Intervention for Suicidal Adolescents–Version II (YST) is associated with reduced mortality 11 to 14 years after psychiatric hospitalization for suicide risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This post hoc secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial used National Death Index (NDI) data from adolescent psychiatric inpatients from 2 US psychiatric hospitals enrolled in the clinical trial from November 10, 2002, to October 26, 2005. Eligible participants were aged 13 to 17 years and presented with suicidal ideation (frequent or with suicidal plan), a suicide attempt, or both within the past 4 weeks. Participants were randomized to receive treatment as usual (TAU) or YST plus TAU (YST). Evaluators and staff who matched identifying data to NDI records were masked to group. The length of NDI follow-up ranged from 11.2 to 14.1 years. Analyses were conducted between February 12, 2018, and September 18, 2018.

Interventions

The YST is a psychoeducational, social support intervention. Adolescents nominated “caring adults” (mean, 3.4 per adolescent from family, school, and community) to serve as support persons for them after hospitalization. These adults attended a psychoeducational session to learn about the youth’s problem list and treatment plan, suicide warning signs, communicating with adolescents, and how to be helpful in supporting treatment adherence and positive behavioral choices. The adults received weekly supportive telephone calls from YST staff for 3 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Survival 11 to 14 years after index hospitalization, measured by NDI data for deaths (suicide, drug overdose, and other causes of premature death), from January 1, 2002, through December 31, 2016.

Results

National Death Index records were reviewed for all 448 YST study participants (319 [71.2%] identified as female; mean [SD] age, 15.6 [1.3] years; 375 [83.7%] of white race/ethnicity). There were 13 deaths in the TAU group and 2 deaths in the YST group (hazard ratio, 6.62; 95% CI, 1.49-29.35; P < .01). No patients were withdrawn from YST owing to adverse effects.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that the YST intervention for suicidal adolescents is associated with reduced mortality. Because this was a secondary analysis, results warrant replication with examination of mechanisms.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00071617

Introduction

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents in the United States and worldwide1,2 and a growing public health concern. Since 2000 in the United States, the suicide rate among adolescents aged 14 to 19 years has increased 28%, and among young adults aged 20 to 25 years, it has increased 31%.1

Adolescents who are hospitalized for suicide risk are at high risk for continued morbidity in the months3,4,5,6 and years following hospitalization.7,8 Some of these adolescents experience chronic suicidal ideation,9 make a suicide attempt, are rehospitalized,3,4,7,10 and experience persistent psychosocial impairment.11,12,13 In a study of adolescents who had attempted suicide, 8.7% of male and 1.2% of female patients died by suicide during an average follow-up period of 5 years.14 In a 10- to 15-year follow-up of adolescents who had attempted suicide, approximately 10% of male and 3% of female patients died by suicide.15 These findings document the high risk of mortality among persons who attempt suicide in addition to the higher proportion of males than females who die by suicide.

We have limited knowledge of effective therapeutic interventions for adolescents who attempt suicide and engage in self-harm.16,17,18 A recent meta-analysis18 of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) identified 19 studies involving 2176 adolescents with psychosocial interventions, and, to our knowledge, no RCTs with pharmacological treatments have been conducted with adolescents. That meta-analysis18 indicated an overall intervention effect for self-harm (suicide attempt or nonsuicidal self-harm) but no overall effect for suicide attempts examined independently. A review of specific types of therapeutic interventions identified several as “probably efficacious” for reducing suicidal and self-injurious behavior. These were variants of cognitive-behavioral, family-based, and psychodynamic therapies with family or parent components.17 Most interventions with positive effects included family involvement or nonfamilial support.16 Consistent with this, a recent RCT, the Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youth Program, linked suicide-attempting or self-harming youth to individual and family therapists. Results showed reduced suicide attempts at 3-month follow-up.19 In addition, a recent RCT of dialectical behavior therapy for suicidal adolescents reported that dialectical behavior therapy was more effective than supportive therapy.20 To our knowledge, previous studies have not examined mortality outcomes associated with interventions for adolescent suicide risk.

The Youth-Nominated Support Team–Version II (YST) is a psychoeducational, social support intervention for adolescents with suicidal ideation or attempt after psychiatric hospitalization.5 In YST, adolescents nominate “caring adults,” who, with the permission of parents or guardians, meet with YST intervention specialists to learn about the adolescent’s psychopathology and treatment plan and ways to support the youth. They have regular contact with the youth, with YST staff support, for 3 months. In the initial RCT, YST was associated with a significant positive main effect for the primary outcome, suicidal ideation. Adolescents in the YST plus treatment as usual (TAU) group compared with adolescents in the TAU group reported a greater reduction in the severity of suicidal thoughts at 6-week follow-up, although this difference was not maintained.5 Nevertheless, YST was associated with several other promising indicators across the 12-month study period: no suicide in the YST group vs 1 in the TAU group; 29 suicide attempts in the YST group vs 35 in the TAU group; a modest positive effect for functional impairment at 12 months, moderated by multiple suicide attempt status; and positive trends for greater treatment utilization. The purpose of our study was to examine mortality outcomes of study participants 11 to 14 years after enrollment. We hypothesized that YST would be associated with lower mortality.

Methods

Study Design and Settings

This study was a secondary analysis of National Death Index (NDI) mortality outcome data for a previously conducted single-blind RCT examining the effectiveness of YST (trial protocol is given in Supplement 1).5 Youth recruitment and baseline assessment occurred between November 10, 2002, and October 26, 2005, with follow-up assessments (6 weeks and 3, 6, and 12 months) conducted by staff masked to intervention status. A CONSORT flow diagram of participants in the RCT was published previously.5 National Death Index data were queried for all participants from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2016. The length of NDI follow-up ranged from 11.2 to 14.1 years (mean, 12.8). This study used baseline assessment, follow-up assessment (ie, mental health service use), and NDI data. Analyses were conducted between February 12, 2018, and September 18, 2018. The University of Michigan institutional review board approved this NDI follow-up study. Adolescents’ parents provided written informed consent, and adolescents provided written informed assent.

Participants were randomized to either the TAU group or the YST plus TAU group (YST group) using a computerized balanced allocation strategy, which ensured that sex, age (<15 years, ≥15 years), and history of multiple suicide attempts were balanced for groups at each site. Group assignments were unknown until after the consent process. Youth received $20 at baseline and $30 per follow-up assessment; each youth’s parent or guardian received $20 per assessment. Methodological details for the randomized clinical trial were published previously.5

Participants

Adolescents aged 13 to 17 years who were patients on a psychiatric unit at a university or private hospital were eligible for the study if they reported serious thoughts about killing themselves within the past 4 weeks (many times or with a plan) or a suicide attempt within the past month, defined by parent or adolescent report on the National Institutes of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children–Version IV (DISC-IV).21 Study exclusion criteria included severe cognitive impairment, direct transfer to a medical unit or residential placement, and residence outside geographic area. Nearly half of study-eligible youths (448 of 1050 [42.7%]) were recruited.

Measures

Study measures have been described previously.5 The DISC-IV suicidal ideation and behavior questions were used to assess study eligibility (noted above), lifetime history of suicide attempt (yes or no), and number of attempts.21 The Kaufman Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (KSADS-PL)22 was administered to assess the presence or absence of the major diagnostic categories reported herein. Adolescents and parents were independently administered the affective disorders section; adolescents were also interviewed about other disorders.

The 15-item, self-reported Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire- Junior (SIQ-JR)23 was used to measure the frequency of a wide range of suicidal thoughts using a 7-point scale ranging from “I never had this thought” to “almost every day.” Total scores range from 0 to 90, with higher scores indicating more suicidal thoughts. The Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised,24 a 17-item semi-structured interview, was administered to adolescents to assess depressive symptoms during the previous 2 weeks. Scores range from 17 to 113 and higher scores indicate more severe depression. Three items from the self-report Personal Experiences Screen Questionnaire (PESQ)25 were used to assess alcohol, marijuana and other substance use (yes or no). In addition, the 18-item PESQ Problem Severity Scale was used to assess level of involvement with drugs. Youth’s suicide attempt history at baseline was assessed with the following items from the NIMH-DISC Mood Disorders module: “Have you ever, in your whole life tried to kill yourself or made a suicide attempt?” and “How many times have you tried to kill yourself?”21

Outcomes

The Services Assessment Record Review is a shorter, adapted version of the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents–Parent Interview26 that we developed specifically for the RCT. It was completed by parents at each follow-up assessment (6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months) with data summed across time periods. Only data from questions assessing number of outpatient psychotherapy sessions, outpatient medication management sessions, and participation in alcohol and drug treatment were analyzed for this report.

A match between the NDI mortality record and a study participant was defined by exact agreement on 1 of the following sets: first name or initial, last name, date of birth, and Social Security number; first name, last name, and date of birth when Social Security number was not available in study records; or first name, last name, date of birth and 7 of 9 Social Security numbers. These match criteria are consistent with guidelines provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.27 Owing to the possibility of false nonmatches for female participants who changed names, it was possible to examine fathers’ surnames as auxiliary information.28 However, no female participants matched on all required criteria but last name. Two research staff masked to intervention status independently evaluated each record. Agreement between study staff was 100%. All NDI matches, as well as 1 obituary report, were confirmed with state death certificates.

Intervention

The YST is a psychosocial intervention designed to supplement routine care for suicidal adolescents after psychiatric hospitalization.5 With support from intervention specialists (psychologists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses), youths randomized to YST5 nominated “caring adults” (from family, school, and community) who they believed would be supportive after hospital discharge. Parental approval was obtained for the involvement of these adults, hereafter referred to as support persons.

Support persons for each youth attended the psychoeducational session individually or as a group. Intervention specialists provided tailored information about adolescent diagnosis and risk factors, treatment plan rationale, suicide warning signs, communicating with adolescents, and emergency services. Much of the session focused on how the support person could be helpful in supporting the youth’s treatment adherence and positive behavioral choices. Support persons were encouraged to maintain weekly contact with youths. Intervention specialists maintained weekly telephone contact with support persons for 3 months.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in mortality between YST and TAU groups are shown by Kaplan-Meier curves of survival probabilities, plotted by group, with the 2-sided log-rank test of equality between groups. The estimated hazard ratio (HR) comparing TAU to YST, with 95% CI, was obtained by using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. We assessed whether the treatment effect was robust to age and sex adjustment by adding each to this model separately owing to small event numbers.

Tests for equality of number of sessions (psychotherapy or medication management) between groups were performed using 2-sample t tests on log(x +1)-transformed data; χ2 tests were used to examine differences in the likelihood of receiving alcohol treatment, drug treatment, or both. One-sided tests were used because YST emphasized the role of support persons in encouraging youths’ treatment adherence. The expectation was that use of mental health services would be the same or greater for the YST vs TAU group. All tests were performed with a P = .05 significance level. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc),29 and SPSS statistical software, version 22 (SPSS Inc).30

Results

Participant Characteristics

The study included 448 adolescents, 132 recruited from a university psychiatric hospital and 316 from a private psychiatric hospital; 223 were allocated to the YST group and 225 to the TAU group. The mean (range) age of participants was 15.6 (13-17) years. Most adolescents identified as female (319 [71.2%]). Race/ethnicity was distributed as follows: white (375 [83.7%]), black (29 [6.5%]), Hispanic (8 [1.8%]), and other or missing (36 [8.0%]). The median household income interval was $40 000 to $59 000. Adolescent diagnoses among the 448 participants included depressive disorder (394 [87.9%]), posttraumatic stress disorder or acute stress disorder (113 [25.2%]), other anxiety disorder (129 [28.7%]), disruptive behavior disorder (186 [41.5%]), and alcohol or substance use disorder (93 [20.8%]).5 Table 1 provides additional demographic and clinical characteristics for adolescents in the total sample and YST and TAU groups. Of the 448 participants, 390 (87%) completed at least 1 follow-up assessment; 346 (77%) completed the 12-month assessment. Retention did not differ by intervention group.5

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Full Sample, YST Group, and TAU Group.

| Characteristic | Full Sample (N = 448) | YST Group (n = 223) | TAU Group (n = 225) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline, mean (SD), y | 15.6 (1.3) | 15.6 (1.2) | 15.6 (1.4) |

| Female, No. (%) | 319 (71.2) | 159 (71.3) | 160 (71.1) |

| Household income, No. (%) | |||

| <$15 000 | 23 (5.1) | 10 (4.5) | 13 (5.8) |

| $15 000-$39 000 | 87 (19.4) | 48 (21.5) | 39 (17.3) |

| $40 000-$59 000 | 83 (18.5) | 45 (20.2) | 38 (16.9) |

| $60 000-$79 000 | 61 (13.6) | 29 (13.0) | 32 (14.2) |

| $80 000-$99 000 | 56 (12.5) | 27 (12.1) | 29 (12.9) |

| >$100 000 | 72 (16.1) | 38 (17.0) | 34 (15.1) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| White | 375 (83.7) | 186 (83.4) | 189 (84.0) |

| Black | 29 (6.5) | 14 (6.3) | 15 (6.7) |

| Hispanic | 8 (1.8) | 4 (1.8) | 4 (1.8) |

| Other or missing | 36 (8.0) | 19 (8.5) | 17 (7.5) |

| Depression, CDRS-R, mean (SD)a | 60.8 (12.1) | 60.8 (13.6) | 60.9 (12.6) |

| Suicidal ideation, SIQ-JR, mean (SD)b | 46.2 (21.4) | 46.6 (21.7) | 45.8 (21.2) |

| Single suicide attempt history, No. (%) | 153 (34.2) | 77 (34.5) | 76 (33.8) |

| Multiple suicide attempt history, No. (%) | 178 (39.7) | 92 (41.3) | 86 (38.2) |

| Alcohol use, No. (%)c | 283 (63.2) | 146 (65.5) | 137 (60.9) |

| Marijuana use, No. (%)c | 211 (49.1) | 115 (51.6) | 96 (42.7) |

| Other drug use, No. (%)c | 121 (27.0) | 71 (31.8) | 50 (22.2) |

Abbreviations: CDRS-R, Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised; SIQ-JR, Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior; TAU, treatment as usual; YST, Youth-Nominated Support Team Intervention for Suicidal Adolescents–Version II.

The CDRS-R is a 17-item semistructured interview. Possible scores range from 17 to 113, with higher scores indicating more severe depression.25

The SIQ-JR is a 15-item, self-reported questionnaire that uses a 7-point scale. Possible scores range from 0 to 90, with higher scores indicating more suicidal thoughts.24

Marijuana and other drug use coded as present if youth reported any use on 3 items from the Personal Experiences Screen Questionnaire (PESQ).26 The YST group reported more other drug use: χ2 = 4.9; P = .03. In addition, the YST group had higher scores than the TAU group on the PESQ Problem Severity Scale (mean [SD] = 27.0 [11.2] vs 29.6 [12.1]; P = .02).

YST Dosage

A total of 656 youth-nominated adults provided written informed consent for study participation. For each adolescent assigned to YST, a mean (SD) of 3.4 (0.9) support persons attended a psychoeducation session. Support persons were predominantly white (527 [80.3%]) and female (461 [70.2%]), with a mean (SD) age of 41.5 (12.3) years. They had a range of relationships to the adolescents and included parents, grandparents, other adult family members, teachers, coaches, parents of friends, and youth group leaders.5 Psychoeducation sessions lasted approximately 1 hour (mean [SD], 63.6 [22.6] minutes), and support persons had a mean (SD) of 9.5 (3.9) contacts with adolescents during the 3-month intervention.5

Mental Health Services Following Study Enrollment

During the 12 months after the youths’ index psychiatric hospitalization, parents or guardians reported that adolescents in the YST group, vs those in the TAU group, attended more outpatient psychotherapy sessions (mean [SD], 26.2 [25.7] vs 22.5 [18.3]; 1-sided t382 = 1.7; P = .04) and medication follow-up sessions (mean [SD], 9.4 [10.5] vs 8.5 [9.8], 1-sided t382 = 1.9; P = .03). Youth in the YST group also were more likely than youth in the TAU group to participate in some type of outpatient alcohol or drug treatment (20 of 165 [12.1%] vs 10 of 166 [6.0%]; χ2 = 3.7; 1-sided P = .03; there was no group difference for inpatient alcohol or drug treatment (12 of 172 [7.0%] for YST vs 8 of 171 [4.7%] for TAU).

Outcomes

Fifteen study participant deaths were identified and confirmed. Table 2 presents the documented cause of death and the NDI and state death certificate match criteria met for each death. Causes of death included suicide (n = 4), drug overdose, accidental or undetermined (n = 8), traffic fatality (n = 1), homicide (n = 1), and infective endocarditis (secondary to drug use [n = 1]). Nine male and 6 female participants died; all deaths occurred between the ages of 18.3 and 27.5 years. Decedents included 13 white, 1 Native American, 1 black, and 2 Hispanic individuals.

Table 2. Study Decedents: Cause of Mortality, NDI Match Criteria, and State Verification.

| Patient/Group/Sex | Age at Death, y | Cause of Death Information | NDI Match Criteria | State Death Certificate Criteria | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDI | State Death Certificate | FN | LN | DOB | SSN | FN | LN | DOB | SSN | ||

| 1/TAU/F | 24.2 | Intentional self-harm (suicide) by hanging, strangulation and suffocation | Hanging | Xa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 2/TAU/M | 24.2 | Intentional self-harm (suicide) by other and unspecified firearm discharge | Gunshot wound to the head | X | X | X | Xb | X | X | X | Xb |

| 3/TAU/M | 18.4 | Intentional self-poisoning (suicide) by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments, and biological substances | Acute drug intoxication (Diprivan, amphetamine, and Ketamine) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4/TAU/M | 21.9 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments, and biological substances | Multiple drug (heroin and chlordiazepoxide) intoxication | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 5/TAU/Fc | 19.8 | Accidental poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics (hallucinogens) | Heroin toxicity | X | X | X | NA | X | X | X | NA |

| 6/TAU/Fc | 26.9 | Mental and behavior disorders due to multiple-drug use and use of other psychoactive harmful use | Drug abuse and complications | X | X | X | NA | X | X | X | NA |

| 7/TAU/F | 18.3 | Mental and behavior disorders due to multiple-drug use and use of other psychoactive harmful use | Drug abuse | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 8/TAU/M | 21.1 | No NDI information found | Multiple drug (morphine, citalopram, and dextro-methorphan) intoxication | NA | NA | NA | NA | X | X | X | X |

| 9/TAU/Mc | 20.8 | Poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments, and biosubstances; undetermined intent | Mixed drugs intoxication | X | X | X | NA | X | X | X | NA |

| 10/TAU/F | 20.8 | Mental and behavior disorders due to use of opioids–harmful use | Heroin abuse | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 11/TAU/M | 19.5 | Driver injured in collision with other and unspecified motor vehicles in traffic accident | Multiple injuries | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 12/YST/Mc | 21.4 | Assault (homicide) by other and unspecified firearm discharge | Multiple gunshot wounds | X | X | X | NA | X | X | X | NA |

| 13/TAU/M | 27.5 | Mental and behavioral disorders due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances, acute intoxication–harmful use | Drug abuse | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 14/YST/Mc | 25.8 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapors | Smoke inhalation | X | X | X | NA | X | X | X | NA |

| 15/TAU/F | 25.8 | Acute and subacute infective endocarditis | Bacterial endocarditis and complications (secondary: drug abuse) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Abbreviations: DOB, date of birth; FN, first name; LN, last name; NA, not available; NDI, National Death Index; SSN, Social Security number; TAU, treatment as usual; YST, Youth-Nominated Support Team Intervention for Suicidal Adolescents–Version II.

The NDI match was on first initial of first name.

Match on 7 of 9 SSNs.

The SSN was not available in study records.

There were 13 deaths in the TAU group and 2 deaths (1 homicide, 1 suicide) in the YST group. The Figure shows survival probabilities for these groups across the 11- to 14-year follow-up. A log-rank test rejected the null hypothesis that groups were the same (χ21 = 8.27; P = .004). The HR for death in the TAU group compared with the YST group was 6.62 (95% CI, 1.49-29.35), meaning that those in the TAU group had a 6.6-fold higher risk of death than those in the YST group. Adjusting for sex or age had little effect on the estimate and the statistical significance.

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Survival Probabilities for Youth-Nominated Support Team Intervention for Suicidal Adolescents–Version II (YST) and Treatment as Usual (TAU) Groups.

When only the 9 suicide deaths and drug-related deaths with unknown intent (not coded as accidental deaths) were considered (8 in TAU, 1 in YST), a log-rank test similarly rejected the null hypothesis that groups were the same (HR, 8.18; 95% CI, 1.02-65.43; P = .02). However, when only the 4 suicide deaths were considered (3 in TAU, 1 in YST), the null hypothesis was not rejected (HR, 3.05; 95% CI, 0.32-29.31; P = .31).

There were no deaths among the 39 youths treated for substance abuse (inpatient or outpatient). A likelihood ratio test examining mortality outcomes associated with substance abuse treatment (any vs none) yielded a P value of .13.

Discussion

The YST, a psychoeducational social support intervention involving youth-nominated caring adults, was associated with reduced mortality across a 11- to 14-year follow-up period. The hazard ratio indicated a 6.6-fold increased risk of death for the TAU group vs the YST group. Although the 95% CI (1.5-29.3) was wide, reflecting the relatively small number of deaths (15), even the lower end of this CI indicates 50% higher mortality in the TAU group. Moreover, YST was previously shown to be a safe intervention with no associated negative outcomes during a 12-month follow-up involving repeated assessment.5 Taken together, although YST was not associated with fewer deaths coded as suicides, this secondary analysis of mortality outcomes indicates that YST may be associated with positive youth trajectories and reduced mortality. To our knowledge, no other intervention for suicidal adolescents has been associated with reduced mortality.

Future studies are needed to replicate our study findings and examine YST’s mechanisms of action, which are suggested by its psychoeducational component, its underlying social support conceptual model,5 and the study results indicating that YST was associated with more outpatient psychotherapy, medication follow-up, and drug treatment. Treatment adherence may have been enhanced by support persons, who learned about the adolescent’s treatment plan and brainstormed ways to encourage adherence during psychoeducation sessions. The association of YST with more drug treatment, the absence of suicides among those who obtained drug treatment, and the number of drug overdose deaths in the TAU group are particularly intriguing in this regard. A second possible mechanism is an increase in perceived support, perhaps coupled with facilitation of problem solving. Perceived support has been associated with less suicidal behavior in multiple studies of adolescents,31 and previous research indicates the possible benefit of brief adjunctive contact interventions for suicide risk.32 Such interventions maintain encouraging contact via telephone or written messages (eg, postcards), and social support and suicide prevention literacy are their likely mechanisms of action.33 Finally, a third possible mechanism is adolescent skill development, learning to communicate with and accept help from supportive adults.

Recent reviews of interventions for suicidal adolescents indicate that family involvement and nonfamilial support may be key ingredients for effectiveness.17,18 The YST intervention was developed with the belief that parental support and involvement in adolescents’ treatment was critically important and could be facilitated by tailored psychoeducation and collaborative discussions. Furthermore, it was based on the notion that parental support could be supplemented by (or compensated for, if limited in some way or unavailable) support from other adult family members and caring adults in the community. The YST provides adolescents with the choice of adult support persons (pending parental approval), which is consistent with health behavior theory principles emphasizing autonomy and choice.34

On the basis of earlier follow-up studies of adolescents attempting suicide, approximately 9% of male and 2% to 3% of female patients would die by suicide during this study’s follow-up.14,15 This is relatively consistent with study findings for the TAU group, in which 10.8% of males and 3.8% of females died. In contrast, only 3.3% of males and 0% of females died in the YST group. However, we note 2 caveats: our sample included some adolescents who had not made suicide attempts (frequent suicidal ideation only) and may have been at lower risk than those in these earlier studies, and the adolescent suicide rate has increased significantly in the United States since these studies were conducted.1

More study participants died of drug overdose (accidental or unknown intent) than suicide during the 11- to 14-year follow-up. This is consistent with recent large-scale studies, which documented increased risk of alcohol- and drug-related deaths among adolescents who initially presented with self-harm injuries to emergency35 and primary care settings.36 Among adolescents and young adults aged 14 to 29 years, the prevalence rate for deaths due to drug poisoning increased from 4.4 to 18.1 per 100 000 between 2000 and 2014.37 Suicide and drug-related deaths share risk profiles and overlap regarding classification. Medical examiners determine cause of death by weighing findings from toxicology reports with evidence of suicide intent,38 and lines between intentional and accidental deaths can be blurry. Adding to the complexity are a lack of standardized definitions and family preferences in coding cause of death.39

Limitations

Study limitations include a relatively small sample size for a mortality outcomes study. Although group differences were found for both premature death and death due to suicide or drug overdose with unknown intent (excluding overdoses coded accidental), there is a small possibility that these findings can be attributed to chance. Results are most meaningfully expressed in terms of CIs for interpretation.40 Second, we did not find intervention main effects for our initial primary outcomes (eg, suicidal ideation) at 12-month follow up, and limited data are available on possible mechanisms of action. Whereas we primarily assessed psychiatric outcomes such as suicidal ideation, it is possible that other intermediary outcomes (eg, improved problem solving and behavioral choices) were important to mortality outcomes. Third, because of the documented limitations of NDI data,28 some deaths may have occurred that we were unable to locate.

Conclusions

The YST was associated with reduced mortality for suicidal adolescents in this secondary analysis of long-term outcomes. Further research is recommended to replicate study findings and examine hypothesized mechanisms of action.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). 2017. https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcause.html. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- 2.World Health Organization Suicide. Fact sheet. 2018; https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en/. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- 3.Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Wartella ME, et al. . Adolescent psychiatric inpatients’ risk of suicide attempt at 6-month follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):95-105. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King CA, Hovey JD, Brand E, Wilson R, Ghaziuddin N. Suicidal adolescents after hospitalization: parent and family impacts on treatment follow-through. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(1):85-93. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King CA, Klaus N, Kramer A, Venkataraman S, Quinlan P, Gillespie B. The Youth-Nominated Support Team-Version II for suicidal adolescents: a randomized controlled intervention trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(5):880-893. doi: 10.1037/a0016552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yen S, Weinstock LM, Andover MS, Sheets ES, Selby EA, Spirito A. Prospective predictors of adolescent suicidality: 6-month post-hospitalization follow-up. Psychol Med. 2013;43(5):983-993. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldston DB, Daniel SS, Reboussin DM, Reboussin BA, Frazier PH, Kelley AE. Suicide attempts among formerly hospitalized adolescents: a prospective naturalistic study of risk during the first 5 years after discharge. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):660-671. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granboulan V, Rabain D, Basquin M. The outcome of adolescent suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(4):265-270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czyz EK, King CA. Longitudinal trajectories of suicidal ideation and subsequent suicide attempts among adolescent inpatients. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(1):181-193. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.836454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barter JT, Swaback DO, Todd D. Adolescent suicide attempts: a follow-up study of hospitalized patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1968;19(5):523-527. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1968.01740110011002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao U, Weissman MM, Martin JA, Hammond RW. Childhood depression and risk of suicide: a preliminary report of a longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):21-27. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Suicidal behaviour in adolescence and subsequent mental health outcomes in young adulthood. Psychol Med. 2005;35(7):983-993. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704004167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinherz HZ, Tanner JL, Berger SR, Beardslee WR, Fitzmaurice GM. Adolescent suicidal ideation as predictive of psychopathology, suicidal behavior, and compromised functioning at age 30. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1226-1232. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotila L, Lönnqvist J. Suicide and violent death among adolescent suicide attempters. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79(5):453-459. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otto U. Suicidal acts by children and adolescents: a follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1972;233:7-123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brent DA, McMakin DL, Kennard BD, Goldstein TR, Mayes TL, Douaihy AB. Protecting adolescents from self-harm: a critical review of intervention studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(12):1260-1271. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glenn CR, Franklin JC, Nock MK. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(1):1-29. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(2):97-107.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asarnow JR, Hughes JL, Babeva KN, Sugar CA. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment for suicide attempt prevention: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):506-514. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, et al. . Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):777-785. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C, Board N. DISC-IV. Diagnostic interview schedule for children (Youth Informant and Parent Informant Interviews): epidemiologic version. New York, NY: Joy and William Ruane Center to Identify and Treat Mood Disorders, Columbia University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. . Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980-988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds WM. Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winters KC. Development of an adolescent alcohol and other drug abuse screening scale: Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire. Addict Behav. 1992;17(5):479-490. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90008-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen PS, Eaton Hoagwood K, Roper M, et al. . The Services for Children and Adolescents-Parent Interview: development and performance characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(11):1334-1344. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000139557.16830.4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Center for Health Statistics National Death Index User’s Guide. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fillenbaum GG, Burchett BM, Blazer DG. Identifying a national death index match. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(4):515-518. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Software [computer program]. Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2013.

- 30.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [computer program]. Version 22. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013.

- 31.King CA, Merchant CR. Social and interpersonal factors relating to adolescent suicidality: a review of the literature. Arch Suicide Res. 2008;12(3):181-196. doi: 10.1080/13811110802101203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milner AJ, Carter G, Pirkis J, Robinson J, Spittal MJ. Letters, green cards, telephone calls and postcards: systematic and meta-analytic review of brief contact interventions for reducing self-harm, suicide attempts and suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(3):184-190. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milner A, Spittal MJ, Kapur N, Witt K, Pirkis J, Carter G. Mechanisms of brief contact interventions in clinical populations: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):194-203. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0896-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patrick H, Williams GC. Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):18-29. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbert A, Gilbert R, Cottrell D, Li L. Causes of death up to 10 years after admissions to hospitals for self-inflicted, drug-related or alcohol-related, or violent injury during adolescence: a retrospective, nationwide, cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390(10094):577-587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31045-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, et al. . Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ. 2017;359:j4351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER). 2017; https://wonder.cdc.gov/. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- 38.Oquendo MA, Volkow ND. Suicide: a silent contributor to opioid-overdose deaths. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(17):1567-1569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1801417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone DM, Holland KM, Bartholow B, et al. . Deciphering suicide and other manners of death associated with drug intoxication: a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention consultation meeting summary. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(8):1233-1239. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bacchetti P. Current sample size conventions: flaws, harms, and alternatives. BMC Med. 2010;8(1):17-23. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement