No more substrate restrictions! Cerium photocatalytic decarboxylative hydrazination of carboxylic acids yields synthetically useful hydrazine derivatives under mild reaction conditions.

No more substrate restrictions! Cerium photocatalytic decarboxylative hydrazination of carboxylic acids yields synthetically useful hydrazine derivatives under mild reaction conditions.

Abstract

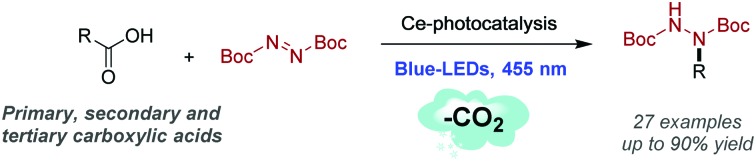

We report the cerium photocatalyzed radical decarboxylative hydrazination of carboxylic acids with di-tert-butylazodicarboxylate (DBAD). The operationally simple protocol provides rapid access to synthetically useful hydrazine derivatives and overcomes current scope limitations in the photoredox-catalyzed decarboxylation of carboxylic acids.

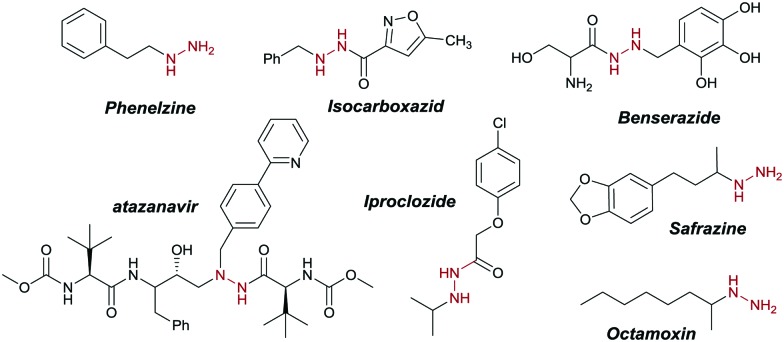

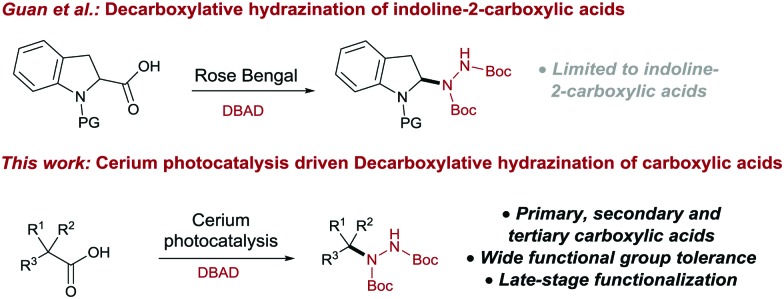

Visible-light photocatalysis is a powerful tool to generate various chemical motifs under very mild reaction conditions.1a–f Many different classes of photocatalysts have been developed over the past decade, but ruthenium and iridium complexes initiating single electron transfer (SET) from a Metal to Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT) state still dominate in synthetic procedures.1a,2a–d However, these transition-metal complexes are rather expensive, potentially toxic and the metal salts are of limited availability.3 Recently, visible-light induced Ligand to Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT) emerged as a robust alternative to generate radical species by the homolysis of the metal–ligand bond.4a–c,5a–c This strategy replaces transition metal complexes with inexpensive metal salts, thus overcoming some of the aforementioned drawbacks. Moreover, as the coordination of the substrate is required for the electron transfer to occur, this approach allows envisioning new scenarios for the late-stage functionalization of complex molecules.5a Decarboxylation reactions convert widely available and inexpensive carboxylic acids into reactive intermediates for the synthesis of valuable chemicals.6a–c Radical decarboxylation of carboxylic acids has been widely explored in synthesis,6c,7a–g as the liberation of CO2 as a traceless and volatile by-product provides a strong driving force for the reaction, forming versatile radical intermediates without the need of pre-functionalization or additional activation reagents.7c Hydrazine derivatives are widely used in the pharmaceutical, agricultural, photographic and dye stuff industries, as well as precursors for heterocyclic compounds such as pyrazoles, pyrazines, and indoles.8 Moreover, the reductive cleavage of the N–N bond gives access to amines (Scheme 4).9a–c The hydrazine motif is found in many pharmacologically active compounds, such as phenelzine, isocarboxazid, iproclozide, safrazine and octamoxin, which show remarkable monoamine oxidase inhibiting (MAOI) activity.10,11 Other compounds, such as the anti-retroviral atazanavir (Scheme 1), proved to be effective in HIV-1 infection treatment.12 Benserazide (Scheme 1), a DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor, is used as therapeutic agent in Parkinson disease treatment.13a,b Considering the prevalence of alkyl and benzylic hydrazine derivatives in the clinical practice, more efficient methods for their synthesis are highly desirable. In 2012, Nishibayashi et al. developed a visible-light Ir-catalyzed C–H hydrazination, limited to the α-amino position.14 More recently, the Guan group reported the hydrazination of the protected indoline core via α-aminoalkyl radicals, using rose Bengal as the photocatalysts under visible light (Scheme 2, upper).15 In 2016, Tunge and co-workers were able to perform the radical decarboxylative hydrazination of carboxylic acids with DIAD (di-isopropyl azo dicarboxylate) as a coupling partner, using the highly oxidizing Fukuzumi catalyst.16 However, no literature method for the deprotection of these DIAD-derived hydrazines into free hydrazine has been reported, thus limiting the broader application of the protocol.17 Herein, we report the first cerium photocatalyzed decarboxylative hydrazination reaction of carboxylic acids with DBAD18 in the presence of visible light at room temperature.

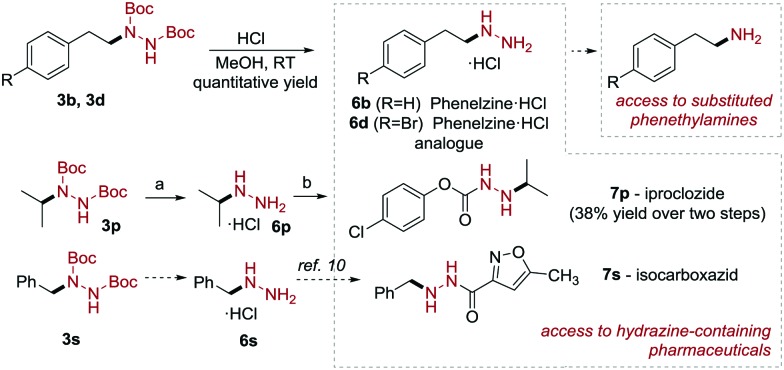

Scheme 4. Access to pharmacologically active scaffolds. Conditions: (a) HCl, MeOH, RT, 3 h, quantitative yield; (b) 4-Cl-phenoxyacetic acid, CDI, THF:DMF, RT, 60 min then 6p, TEA, DMF, 80 °C, overnight, 38% over two steps.

Scheme 1. Pharmaceutically relevant hydrazines.

Scheme 2. Visible light driven radical decarboxylative hydrazination of carboxylic acids using DBAD.

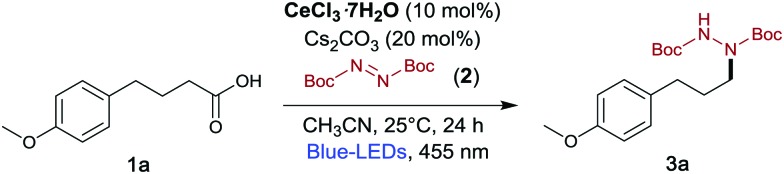

Inspired by the recent work of Zuo et al., who generated 1,5-HAT-hydrazination from alcohols with a cerium-photocatalyst,5a we wondered how carboxylic acids would behave under similar reaction conditions. At first, we investigated the reaction of 4-(4-methoxyphenyl)butyric acid (1a) with DBAD (2) using different reaction conditions (Table 1). To our delight, when a solution of 1a with 1.5 equiv. of DBAD in the presence of Cs2CO3 (20 mol%) and CeCl3·7H2O (10 mol%) in acetonitrile (MeCN) was illuminated with a blue LED (455 nm) at 25 °C for 24 h, compound 3a was obtained in 90% yield (Table 1, entry 1). The reaction using anhydrous CeCl3 as a photocatalyst also proceeded smoothly to give 3a in 80% yield (Table 1, entry 2),19 while the conversion to 3a slightly decreased upon use of other cerium salts (Table 1, entry 3 and 4). When Cs2CO3 was replaced by K2CO3, 3a was afforded in 66% yield (Table 1, entry 5), while other bases such as Na2CO3, Li2CO3 and NaHCO3 caused a drastic reduction in the yield (Table 1, entries 6–8).

Table 1. Optimization of the reaction conditions. 1a (0.1 mmol), DBAD (0.15 mmol), CeCl3·7H2O (10 mol%), CH3CN (0.1 M) at 25 °C, 455 nm LED for 24 h.

| ||

| Entry | Deviation from standard conditions | 3a a (%) |

| 1 | None | 90 (80) b |

| 2 | CeCl3 instead of CeCl3·7H2O | 80 |

| 3 | Ce(OTf)3 instead of CeCl3·7H2O | 66 |

| 4 | Ce(OTf)4 instead of CeCl3·7H2O | 63 |

| 5 | K2CO3 instead of Cs2CO3 | 66 |

| 6 | Na2CO3 instead of Cs2CO3 | 55 |

| 7 | Li2CO3 instead of Cs2CO3 | 25 |

| 8 | NaHCO3 instead of Cs2CO3 | 23 |

| 9 | Without base | 20 |

| 10 | DCM instead of CH3CN | 85 |

| 11 | DCE instead of CH3CN | 86 |

| 12 | CHCl3 instead of CH3CN | 66 |

| 13 | DMSO instead of CH3CN | 61 |

| 14 | Without light | 0 |

| 15 | Without CeCl3·7H2O | 0 |

aNMR yields using benzoyl benzoate as internal standard.

bIsolated yield.

Solvents such as chloroform (CHCl3) and DMSO had a detrimental effect on the reaction (Table 1, entries 12 and 13). Additionally, control experiments revealed that a catalytic amount of base (Table 1, entry 9), the cerium salt and light irradiation were required for the transformation to occur. Not even traces of 3a were found in the absence of light or the cerium catalyst (Table 1, entries 14 and 15).

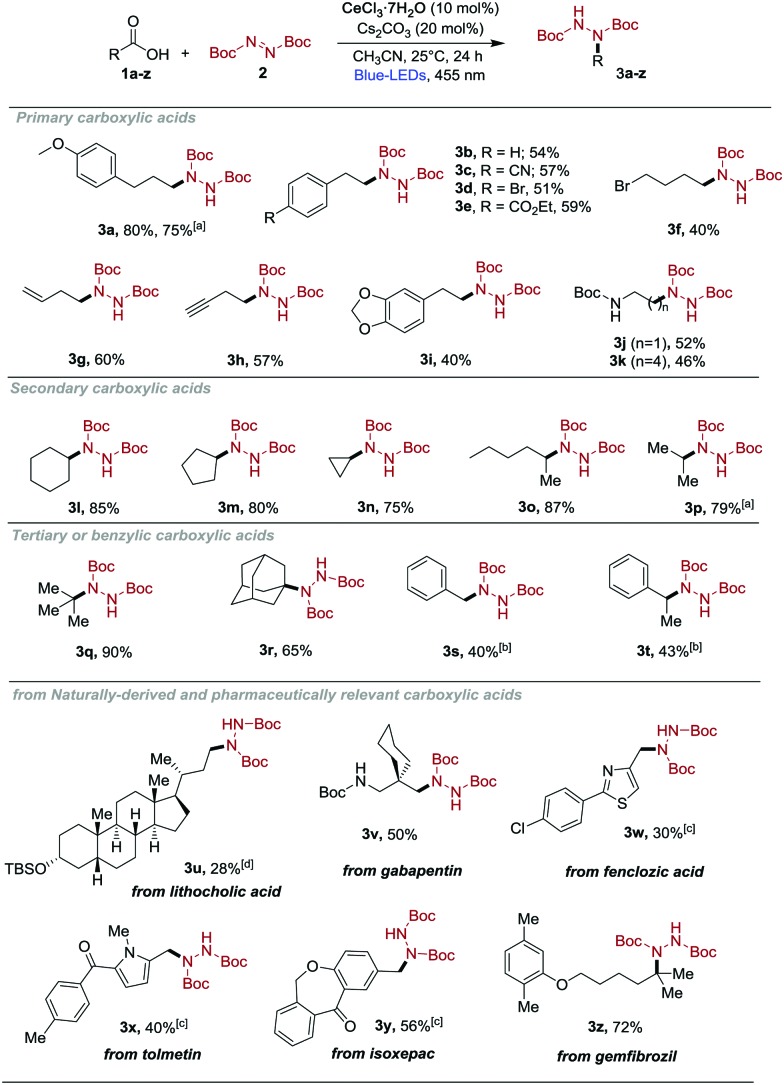

With the optimized conditions in hand, we evaluated the scope of the reaction. As shown in Scheme 3, a broad range of carboxylic acids reacted, providing the corresponding hydrazine derivatives in good to excellent yield. Primary carboxylic acids were found to be generally competent; diverse electron-withdrawing (3c and 3e, 57% and 59% yield), electron-donating (3a, 80% yield) or electron-neutral substituents (3b, 54% yield) as well as cyclic ketals (3i) were tolerated on the aryl ring. Deprotection of 3b under acidic conditions afforded the HCl salt of phenelzine 6b (Scheme 4), which is currently used for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, in quantitative yield. Amino acid derivatives (1j and 1k) were also viable substrates and gave the corresponding products 3j and 3k in moderate yields (52% and 46%). Terminal alkenes (3g) and alkynes (3h) were tolerated under the mild reaction conditions.

Scheme 3. Decarboxylative hydrazination of carboxylic acids. Reaction conditions as given in Table 1 (entry 1). Isolated yields, average of at least two independent runs. a Reaction performed at 1.0 mmol scale. b Degassed CH3CN was used as a solvent. c Degassed DMSO was used as a solvent. d Degassed DCM was used.

Next, we turned our attention to secondary and tertiary carboxylic acids (3l–3r, 3t, 65–90% yield). We were pleased to find that cyclic secondary carboxylic acids, including strained 3-membered rings (1n) as well as larger homologues (1l, 1m) participate in this reaction in good to excellent yield (3n–3m, 75–85% yield). Moreover, secondary acyclic systems also produced the desired hydrazine derivatives with good efficiency (3o and 3p, 87% and 80% yield, respectively). Compound 3p was used to prepare iproclozide 7p (Scheme 4), which is used as antidepressant drug. The acidic deprotection of 3p yielded the corresponding hydrazium salt (6p) in quantitative yield, which was coupled with 4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid. A number of other tertiary alkyl carboxylic acids were also successfully converted to hydrazine derivatives in excellent yields (3q and 3r, 90% and 65% yield). To our surprise, phenyl acetic acids (1s and 1t) afforded the corresponding products (3s, 3t) only in moderate yields (40% and 43%). Nevertheless, the former product (3s) can be envisaged as an advanced intermediate for the formal synthesis of isocarboxazid in 7s in two steps (Scheme 4).10

To further demonstrate the utility of this decarboxylative hydrazination approach, we performed a series of late-stage modifications on active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and compounds derived from natural products (Scheme 3, 1u–z). To our delight, a large variety of such molecules containing carbonyl groups and heterocycles (1x–y) react chemoselectively by introducing the hydrazine moiety (3u–z, 28–72% yield). Furthermore, the reaction can be conducted at a one mmol scale without any significant erosion in the yield (3a and 3p).

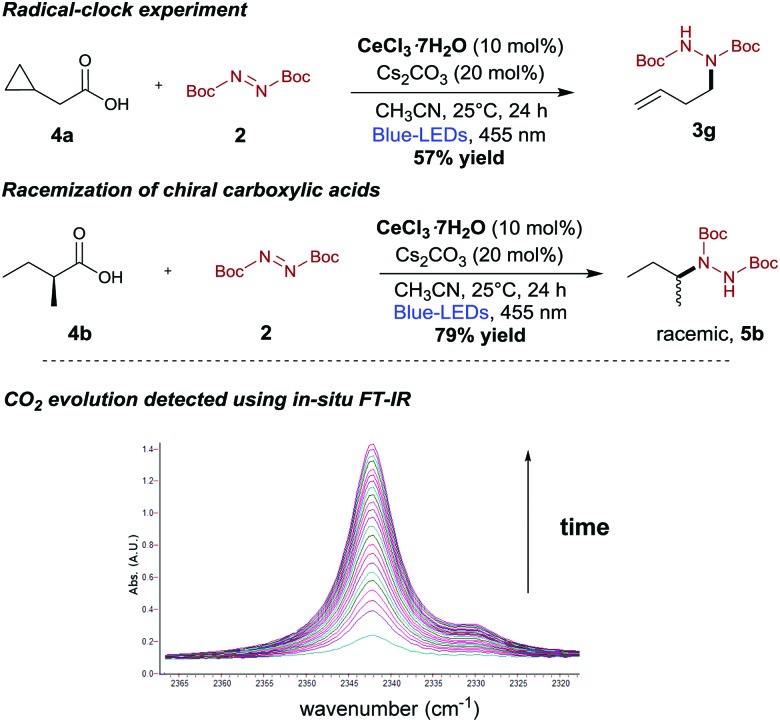

The efficiency of our decarboxylative hydrazination prompted us to conduct some preliminary mechanistic studies (Scheme 5). As anticipated, intermittent irradiation experiments confirmed that our reaction required a continuous visible light irradiation to proceed (see ESI†). We currently believe that this decarboxylative hydrazination reaction could proceed via the generation of alkyl radicals.20 In a radical clock experiment using 2-cyclopropylacetic acid (4a) under our reaction conditions, the ring-opened product 3g was isolated (Scheme 5, upper). Moreover, enantiopure (S)-2-methylbutanoic acid (4b) provided the racemic hydrazination product 5b (Scheme 5, center). The inhibition of any catalytic activity upon TEMPO addition further corroborated the hypothesis that the reaction proceeds via radical intermediates. Additionally, we were able to monitor the CO2 evolution by in situ infrared spectroscopy using a custom-made dedicated set-up (Scheme 5, lower).

Scheme 5. Preliminary mechanistic investigations: for full FT-IR spectrum, see ESI.† .

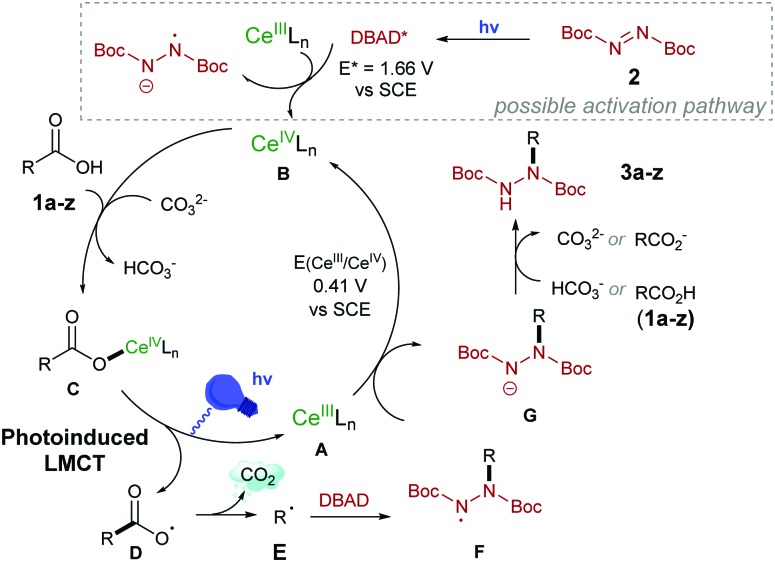

Based on these experimental observations and the reports of Zuo et al.5a–c we propose that the decarboxylative hydrazination proceeds via Ligand to Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT), which generates the key carboxy-radical. The simplified mechanistic proposal is shown in Scheme 6. The putative CeIII species A could be oxidized to CeIV (E1/2(CeIII/CeIV) = 0.41 V vs. SCE in MeCN) either by the N-centered radical F or by the photo-excited DBAD (E* = 1.66 V vs. SCE in MeCN).5b The coordination of the substrate forms complex C, which undergoes the photoinduced Ce–O(CO) homolytic cleavage20 to yield the “spring-loaded” carboxy-radical D and regenerates the catalytically competent CeIII species A (detected by UV spectroscopy, see ESI†). Upon rapid decarboxylation, the carbon-centered radical E forms and is trapped by DBAD to provide the more stable N-centered radical (F), which upon a SET-protonation cascade yields the product 3a–z. The proposed mechanism emphasizes the catalytic role of the base that is consumed in the coordination step from 1a–z and regenerated upon the proton-transfer to G.

Scheme 6. Proposed mechanism for the decarboxylative hydrazination.

In summary, we have developed a general strategy for the catalytic, radical decarboxylative hydrazination of unactivated carboxylic acids using an inexpensive cerium photocatalyst.

This operationally simple protocol allows an efficient synthesis of hydrazine derivatives and was applied to the modification of API related compounds. The method provides a new and simple route to hydrazine derivatives and may be of use for the discovery of new hydrazine-based compounds with biological activity.

We Thank European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 741623) for financial support and P. B. thanks the Elitenetzwerk Bayern (SynCat) for financial support. We also thank Dr G. Huff for the in situ IR spectroscopy and N. Wurzer for an optical rotation measurement.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9cc00492k

References

- For selected reviews on photoredox catalysis, see: ; (a) Marzo L., Pagire S. K., Reiser O., König B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018;57:10034. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kärkäs M., Porco Jr. J., Stephenson C. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:9683. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Romero N. A., Nicewicz D. A. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:10075. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Skubi K., Blum T., Yoon T. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:10035. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Shaw M. H., Twilton J., MacMillan D. W. C. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:6898. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Twilton J., Le C. C., Zhang P., Shaw M. H., Evans R. W., MacMillan D. W. C. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017;1:52. [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see: ; (a) Musacchio A., Nguyen L., Beard G., Knowles R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12217. doi: 10.1021/ja5056774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zuo Z., Ahneman D., Chu L., Terrett J., Doyle A., MacMillan D. W. C. Science. 2014;345:437. doi: 10.1126/science.1255525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jeffrey J., Terrett J., MacMillan D. W. C. Science. 2015;349:1532. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chu J., Rovis T. Nature. 2016;539:272. doi: 10.1038/nature19810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M., Füldner S., Koenig B., Zeitler K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:951. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Balzani V., Ceroni P. and Juris A., Photochemistry and photophysics: concepts, research, applications, John Wiley & Sons, 2014. [Google Scholar]; (b) Natarajan E., Natarajan P. Inorg. Chem. 1992;31:1215. [Google Scholar]; (c) Vogler A., Kunkely H. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2006;359:4130. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Hu A., Guo J.-J., Pan H., Tang H., Gao Z., Zuo Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1612. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b13131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hu A., Guo J.-J., Pan H., Zuo Z. Science. 2018;361:668. doi: 10.1126/science.aat9750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hu A., Chen Y., Guo J.-J., Yu N., An Q., Zuo Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:13580. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews on decarboxylative strategies, see: ; (a) Rodriguez N., Gooßen L. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:5030. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15093f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dzik W., Lange P., Gooßen L. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:2671. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wei Y., Hu P., Zhang M., Su W. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:8864. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected articles on photocatalyzed decarboxylation, see: ; (a) Zuo Z., MacMillan D. W. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:5257. doi: 10.1021/ja501621q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zuo Z., Ahneman D. T., Chu L., Terrett J. A., Doyle A. G., MacMillan D. W. C. Science. 2014;345:437. doi: 10.1126/science.1255525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xuan J., Zhang Z.-G., Xiao W.-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:15632. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Johnston C. P., Smith R. T., Allmendinger S., MacMillan D. W. C. Nature. 2016;536:322. doi: 10.1038/nature19056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Huang H., Jia K., Chen Y. ACS Catal. 2016;6:4983. [Google Scholar]; (f) Lin J., Li Z., Su W., Li Y. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14353. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Yang B., Yu D., Xu X.-X., Qing F.-L. ACS Catal. 2018;8:2839. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Hydrazine and its Derivatives, In Kirk-Othmer – Encylopedia Chemical Technology, ed. R. E. Kirk and D. F. Othmer, Wiley, New York, 4th edn, vol. 13, 1995. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ragnarsson U. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2001;30:205. [Google Scholar]

- Selected publications: ; (a) Panas M. W., Xie Z., Panas H. N., Hoener M. C., Vallender E. J., Miller G. M. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:866. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9321-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Araujo A. N., Carvalho F., Bastos Md. L., de Pinho P. G., Carvalho M. Arch. Toxicol. 2015;89:1151. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1513-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gainetdinov R. R., Hoener M. C., Berry M. D. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018;70:549. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.015305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner T. S., Rutherford Lee J., Fells E. and Wenis E., US Pat., US2908688, 1959; Chem. Abstr., 1962, 56, 25114. [Google Scholar]

- Youdim M. B. H., Edmondson D., Topton K. F. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:295. doi: 10.1038/nrn1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Bold G., Fassler A., Capraro H.-G., Cozens R., Klimkait T., Lazdins J., Mestan J., Poncioni B., Rosel J., Stover D., Tintelnot-Blomley M., Acemoglu F., Ucci-Stoll K., Wyss D., Lang M. J. Med. Chem. 1988;41:3387. doi: 10.1021/jm970873c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kroom K. F., Dhillon S., Keam S. J. Drugs. 2009;69:1107. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969080-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Mutschler E., Geisslinger G., Kroemer H. K., Ruth P. and Schäfer-Korting M., Drug Effects Textbook of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Scientific publishing house, Stuttgart, 9th edn, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8047-1952-1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barbeau A., Roy M. Neurology. 1976;26:399. doi: 10.1212/wnl.26.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y., Nakajima K., Nishibayashi Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012;18:16473. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.-J., Schroeder G. M., He Y.-H., Guan Z. RSC Adv. 2016;6:96693. [Google Scholar]

- Lang S. B., Cartwright K. C., Welter R. S., Locascio T. M., Tunge J. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016:3331. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201600620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The corresponding iPr-carbamates, derived from amines, are usually deprotected under harsh conditions, for instance: (a) HCl, AcOEt, 100 °C; (b) AlCl3, DCM; (c) HBr, H2O, reflux; (d) HCl, water, 90 °C, 48 h.

- DEAD and DIAD performed equally well, but DBAD was chosen for the versatility of the products.

- The lower yield was possibly due to the reduced solubility in organic solvents.

- Sheldon R. A., Kochi J. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90(24):6688. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.