Abstract

Objectives

Postoperative wound dehiscence (PWD) is a serious complication to laparotomy, leading to higher mortality, readmissions and cost. The aims of the present study are to investigate whether risk adjusted PWD rates could reliably differentiate between Norwegian hospitals, and whether PWD rates were associated with hospital characteristics such as hospital type and laparotomy volume.

Design

Observational study using patient administrative data from all Norwegian hospitals, obtained from the Norwegian Patient Registry, for the period 2011–2015, and linked using the unique person identification number.

Participants

All patients undergoing laparotomy, aged at least 15 years, with length of stay at least 2 days and no diagnosis code for immunocompromised state or relating to pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium. The final data set comprised 66 925 patients with 78 086 laparotomy episodes from 47 hospitals.

Outcomes

The outcome was wound dehiscence, identified by the presence of a wound reclosure code, risk adjusted for patient characteristics and operation type.

Results

The final data set comprised 1477 wound dehiscences. Crude PWD rates varied from 0% to 5.1% among hospitals, with an overall rate of 1.89%. Three hospitals with statistically significantly higher PWD than average were identified, after case mix adjustment and correction for multiple comparisons. Hospital volume was not associated with PWD rate, except that hospitals with very few laparotomies had lower PWD rates.

Conclusions

Among Norwegian hospitals, there is considerable variation in PWD rate that cannot be explained by operation type, age or comorbidity. This warrants further investigation into possible causes, such as surgical technique, perioperative procedures or handling of complications. The risk adjusted PWD rate after laparotomy is a candidate quality indicator for Norwegian hospitals.

Keywords: postoperative wound dehiscence, surgical quality, quality indicators, patient safety

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Includes all laparotomies performed in the nation over a 5-year period, with patients followed across hospitals.

Extends previous studies to a new health system and a new coding system.

The statistical analysis uses methods for low event rates, avoiding asymptotic approximation.

Results may be subject to coding inaccuracy and incompleteness, as well as selection effects.

There were no data for surgical technique, nor for some clinical factors known to be relevant.

Introduction

The past decades have seen a major growth in initiatives for measuring, monitoring and improving the quality of healthcare services. Quality indicators are regularly published in many healthcare systems. Performance of healthcare systems is also compared across nations, for instance in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Health Care Quality and Outcomes initiative, which Norway is a part of.1 2 Norway has a national quality indicator system for monitoring and comparing hospital performance, however, not all areas of hospital performance are covered by existing national quality indicators. While there are quality indicators for outcomes such as mortality and process measures such as waiting times, complications following hospital care is less explored, which is especially relevant following surgical procedures.

Postoperative wound dehiscence (PWD) rates after open abdominal surgery (laparotomies) was introduced as a patient safety indicator in the United States and later as a quality indicator by OECD.3–6 Norway reported the second highest numbers for 2014–2015, with a PWD rate of 1.02%. The overall range was 0.055% to 1.05%.5 Neighbouring Sweden, with comparable population health and healthcare, reported 0.30%. Moreover, a recent study comparing adverse events in Norway and Sweden found significantly higher adverse event rates of surgical complications in Norwegian hospitals, compared with Swedish hospitals.7

PWD is a serious complication that leads to higher mortality rates, higher implicit, explicit and social costs as well as increased readmission rates.8 9 The PWD rate has been studied elsewhere as a quality indicator for hospitals, and found to have a high positive predictive value.10 11 It is useful as a quality indicator, since several of the risk factors are modifiable and within control of the hospital and surgical team. There are few events per hospital, making it challenging to identify outlier hospitals for quality improvement because of the high statistical uncertainty.

Previous research has identified a number of risk factors for PWD. Examples of such factors are: (I) patient related variables and comorbidities: smoking,12 obesity,13 chronic pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency or diabetes14 and use of immunosuppressive agents15 16; (II) procedure related factors: operation type,9 17 type of incision and closure18–20 and length of operation time21; (III) postoperative parameters: clean wound classification,21 coughing9 and wound infection9 14; (IV) operative scenario: for example, qualifications of the surgeon21–23 and of the perioperative team, and whether the surgery is emergent.9 13

The objectives of this study are to study the occurrence and variation of PWD after laparotomy at Norwegian hospitals, and the potential usefulness of a PWD indicator for the Norwegian healthcare system, computed from patient administrative data. More specifically we aimed to (1) investigate the possibility to identify hospitals with higher or lower laparotomy PWD rate than average, after appropriate risk adjustment, (2) study the variability of the PWD rate among hospitals, and its relation to hospital type and laparotomy volume.

Material and methods

Patient administrative data from all Norwegian hospitals were provided by the Norwegian Patient Registry (NPR) for the period 2011–2015.24 This comprised individual patient data from all department stays: type of admission (acute or elective), primary and secondary diagnosis codes according to the Norwegian version25 of ICD-10, surgical and medical procedures, age, gender, date and time of ward admission and discharge. Surgical procedures and operations were coded according to the Norwegian version of the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) Classification of Surgical Procedures.26 Procedure time and date were not available. It was therefore not possible to exclude reclosures of wounds occurring before or on the same day as laparotomies within the same episode, as requested in the OECD indicator specification. The NPR data files were checked for missing values and inconsistencies between variables, such as date and time of discharge before admission or invalid ICD-10 code. We had no access to clinical data, such as, eg, type of suture, which would have enabled us to study the causes of the reported dehiscences.

Wound dehiscence was defined as the occurrence of a code for a reclosure operation, that is, a reoperation for wound dehiscence. This excludes superficial dehiscences, as these are usually not resutured, and the code for reclosure operation is restricted to deep wound dehiscences. Laparotomies and wound reclosure operations were identified according to procedure codes. An operation coded with a laparotomy code, signifies an incision into the abdominal wall, through the fascia and with an opening of the abdominal cavity. Laparoscopic and endoscopic procedures were not included. Details of the codes used can be found in the online supplementary file.

bmjopen-2018-026422supp001.pdf (791.8KB, pdf)

All permanent residents in Norway have a personal identification number (PIN), registered in the NPR. NPR prepared an encrypted PIN for all patients with a valid PIN, allowing tracking of patients over time and between hospitals. The data were linked with the National Registry to provide data of death (when applicable), using the PIN.

Ward admissions for each patient, at more than one hospital in case of transfers, were linked into episodes of care when less than 8 hours elapsed from time of discharge to the next ward admission.27 An episode was regarded as acute if the first admission in the episode was coded as non-elective, as a laparotomy episode if it included any procedure code for laparotomy (reclosures not included), and a reclosure episode if a reclosure code was found. The initial data set consisted of all laparotomy and reclosure episodes. Each reclosure episode was linked to the laparotomy episode immediately preceding or coinciding with it. Reclosure episodes with no preceding laparotomy episode within 30 days, as well as laparotomy or reclosure episodes following a reclosure episode within 30 days, were excluded. Note that the linking of laparotomies and reclosures was not part of the original OECD specification, but is required in order to attribute PWD to hospitals and to enable risk adjustment. Following the OECD specification, laparotomy episodes (and consequently any linked reclosure episodes) were excluded if a diagnosis code for immunocompromised state or relating to pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium was present, if the length of stay was less than 2 days, or if the patient’s age was less than 15 years. Hospitals with less than 10 laparotomies over the 5-year period were excluded. The hospitals belonged to one of three types: regional, large with acute function and small with acute function. For details of the diagnosis and operation codes used, see the online supplementary file. For risk adjustment, Charlson comorbidities were determined from previous admissions 3 years prior to, but not including the current episode of care.27–29 Diagnoses were grouped according to the Clinical Condition Summary system, adapted to the Norwegian version of ICD-10.30

Statistical methods

Risk adjusted probabilities for a laparotomy episode resulting in a reclosure operation were estimated by bias corrected logistic regression.31 The final model was fit by stepwise regression with the BIC criterion, allowing for potential two-way interactions.

To identify outlier hospitals, that is, those with high or low risk adjusted PWD probabilities, estimated hospital effects were compared with a reference value, defined as the 25% trimmed mean of the hospital effects on the logistic scale.32 As some hospitals reported zero reclosures, ordinary maximum likelihood estimates of the model parameters do not exist, due to separation,33 and the estimated variances of the fitted parameters, based on their asymptotic distribution, become unreliable. The comparison used an exact test based on the Poisson binomial distribution for the number of PWDs per hospital, using the estimated probabilities for each case, together with parametric bootstrapping to account for the estimation uncertainty in the model parameters. Tests for significance were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Guo-Romano method,34 and outlier status assigned according to the false discovery rate (FDR). An FDR not exceeding 5% was regarded as significant. For sensitivity analysis, two alternative risk adjustment models were tested, with either a four-category grouping of procedures, or with diagnosis categories, instead of the 13-category procedure grouping. In addition, a model with the four Norwegian hospital regions was also estimated.

Hospital volume, modelled by splines,35 was tested for inclusion in the model. We also performed this test after exclusion of hospitals with zero reclosures.

Finally, the hospital specific effects were modelled as a mixture of two normal distributions. The expectation-maximisation algorithm was used, taking into account the estimation variances. The mixture model yielded estimates of the quartiles of the hospital ORs and the scaled IQR (normalised by dividing by 1.349, to give the SD in the case of a normal distribution) was computed as a measure of spread among hospitals. Bootstrapping of the mixture model was used to find a 95% CI for the scaled IQR.

Risk adjustment

The following case-mix variables were included as candidates in the stepwise regression: age, gender, indicators for the individual Charlson comorbidities, number of previous hospital admissions 2 years prior to current admission, and whether the episode was acute or elective. A linear trend in admission year was also included. Age was modelled by natural splines with knots at the median and quartiles.35 Based on previous studies of risk factors,9 17 procedures were categorised into 13 types, according to the body system or organ involved. The effects of operation types were normalised to have zero sum on the logistic scale.

For a quality indicator, only characteristics of the patient when entering the hospital, are meaningful risk adjustment variables. No data were available for smoking, obesity or other patient or case characteristics such as nutritional status. There was no information about operation urgency beyond the status of the hospital admission or episode as elective or acute.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the planning, conduct or analysis of this study. The policy of the Norwegian Institute of Public health is to publish hospital quality indicators, when they have been successfully validated.

Results

The initial data set comprised 96 102 episodes with laparotomy and 1909 with a reclosure operation. After restricting data to reclosures paired with a laparotomy within 30 days, 1580 reclosures remained. After exclusions for pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium or immunocompromised state, age and length of stay, 78 299 laparotomies remained. Lastly, hospitals with less than 10 laparotomies were excluded, yielding a final data set with 66 925 unique patients, 78 086 laparotomies and 1477 reclosures from 47 hospitals. Descriptive statistics for the dataset are shown in table 1. The operation types are tabulated in the online supplementary file.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for final data set

| PWD | No PWD | |

| Age, years, median (quartiles) | 69 (61–78) | 65 (51–75) |

| Gender, females, n (%) | 517 (35) | 43 094 (56) |

| Acute laparotomy episode, n (%) | 657 (44) | 26 381 (34) |

| Main diagnosis for reclosure episode coded as PWD, n (%) | 45 (3.1) | — |

| Main diagnosis for reclosure episode coded as deep wound infection, n (%) | 274 (19) | — |

| Hospital type for laparotomy episodes | ||

| Regional, n (%) | 545 (37) | 28 104 (37) |

| Large with acute function, n (%) | 810 (55) | 40 291 (53) |

| Small with acute function, n (%) | 122 (8.3) | 8214 (11) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes with complications, n (%) | 18 (1.2) | 893 (1.2) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease, n (%) | 196 (13) | 5147 (6.7) |

| Renal disease, n (%) | 66 (4.5) | 2716 (3.5) |

| 30-day mortality (laparotomy episode), % | 67 (4.5) | 2668 (3.5) |

| Length of stay laparotomy episode, days, median (quartiles) | 19 (11–29) | 7.4 (4.4–13) |

| Reclosure and matched laparotomy in same episode, n (%) | 1211 (82) | — |

| Converted from laparoscopy or endoscopy to laparotomy, n (%) | 12 (0.81) | 578 (0.75) |

| Robot assistance in laparotomy, n (%) | 3 (0.2) | 404 (0.53) |

PWD, postoperative wound dehiscence.

From 2011 to 2015, the annual volume of laparotomies decreased somewhat, from 16 730 to 14 419, while the proportion of acute laparotomies remained stable at around 35%.

The overall rate of PWD for the 5-year period was 1.89%. Crude PWD rates varied from 0% to 5.1% among hospitals. After risk adjustment, the range was 0.1%–5.4%. Table 2 shows the ORs of the final logistic regression model. No interactions were included. The model showed good fit according to the modified Hosmer-Lemeshow test36 (p=0.53) and good predictive ability, with an area under the operating characteristic (c-statistic) of 0.73.

Table 2.

Final multivariate logistic model for risk adjustment

| Variable | Adjusted ORs (95% CI) |

| Year of admission | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.96) |

| Age, spline function | |

| 40 (reference) | 1.00 |

| 50 | 1.37 (1.25 to 1.49) |

| 60 | 1.97 (1.65 to 2.36) |

| 70 | 2.39 (1.97 to 2.90) |

| Gender | |

| Female (reference) | 1 |

| Male | 2.42 (2.16 to 2.72) |

| Elective laparotomy episode (reference) | 1 |

| Acute laparotomy episode | 1.36 (1.21 to 1.52) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.72 (1.47 to 2.01) |

| Operation type* | |

| Exploratory laparotomy | 2.40 (1.78 to 3.24) |

| Hernia (diaphragmal) | 2.57 (1.37 to 4.81) |

| Thoracoabdominal aorta | 2.08 (0.85 to 5.09) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 2.04 (1.69 to 2.46) |

| Liver | 1.14 (0.69 to 1.87) |

| Biliary tract | 0.12 (0.05 to 0.28) |

| Pancreas | 0.79 (0.40 to 1.58) |

| Spleen | 1.20 (0.45 to 3.24) |

| Other digestive system | 1.46 (1.03 to 2.07) |

| Kidney | 0.09 (0.03 to 0.28) |

| Other urinary and male genital organs | 0.52 (0.37 to 0.71) |

| Female genital organs | 1.43 (1.06 to 1.92) |

| Peripheral vascular surgery | 1.21 (0.93 to 1.57) |

| More than one type of surgery† | 2.58 (2.12 to 3.15) |

| Hospital | |

| Scaled IQR | 0.30 (0.23 to 0.34) |

*ORs for operation type is scaled to have geometric mean of one.

†Not counting exploratory laparotomy.

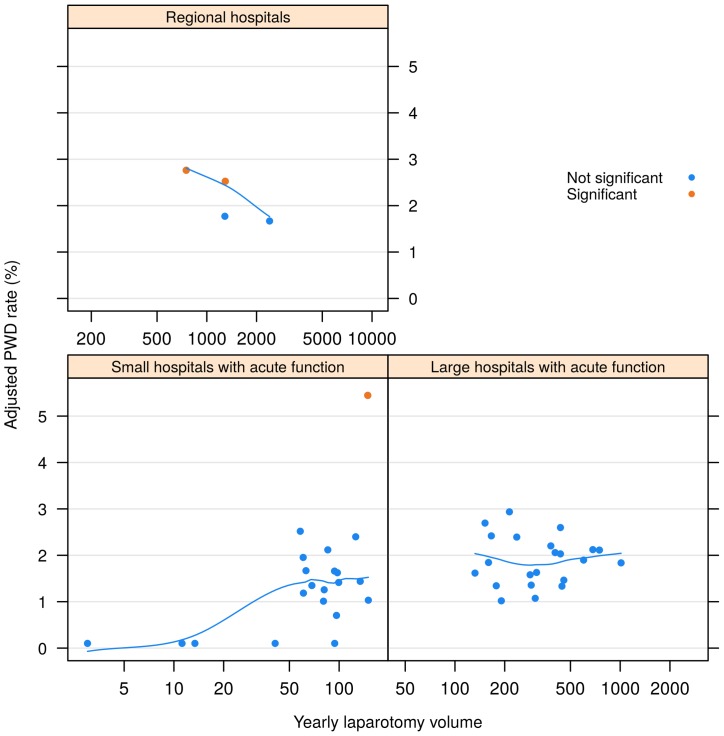

In figure 1, risk-adjusted PWD rates are shown for each hospital, plotted versus laparotomy volume and hospital type.

Figure 1.

Risk adjusted PWD rates versus yearly laparotomy volume, by hospital type. Trend curve is obtained by smoothing the scatterplot. Significance testing is adjusted for multiple comparisons. PWD, postoperative wound dehiscence.

After significance testing, we identified three hospitals with higher PWD and none with lower PWD than average, when correcting for multiple testing. Without multiple test correction, one additional hospital with high PWD was found to be marginally significant (p=0.053).

In the alternative model including volume, the PWD increased with yearly laparotomy volume from a very low level up to 120 laparotomies per year, after which it remained fairly constant, see figure 1. The effect of volume was significant (p<0.001), also after exclusion of the four smallest volume hospitals with zero reclosures (p=0.008). Hospital type coincided almost completely with a grouping of hospitals by volume, and was therefore not tested separately. There was significant variation among regions (p<0.001), with the Northern region having the highest and the South-Eastern region the lowest rates. Details can be found in the online supplementary file. Using diagnosis categories or aggregated operation type as risk adjustment variables resulted in very small changes in risk adjusted PWD rates.

Discussion

We have studied wound dehiscence after laparotomy, as a quality indicator based on the OECD specification, and found that it discriminated between Norwegian hospitals. The indicator was risk adjusted for differences in age, gender, comorbidity and type of surgery, and showed little sensitivity to changes in the set of risk adjustment variables. The overall PWD rate was 1.89%. After risk adjustment, the hospitals’ PWD rate varied between 0.1% and 5.4%. Laparotomy volume and type of hospital had little effect on the PWD rate, except for hospitals with very low volume. Advanced age, male gender, chronic pulmonary disease and emergency laparotomy were all significant risk factors for PWD. There were significant PWD differences according to the organ system targeted. The overall rate of PWD showed a small but statistically significant decline over the observation period 2011–2015. The relatively large variation of PWD rates between hospitals, after correction for patient characteristics and operation type, indicates possible variation in the quality of healthcare among hospitals. This may be due to variation in surgical technique and perioperative care, as well as the handling of postoperative complications, such as wound infection, which is known to be a risk factor for PWD.17 We found PWD rates well within the range reported in international studies.9 13 14 17 21 37 38 Also, the risk factors identified are in accordance with previous studies, although limited to administrative data. Laparotomy volume has negligible effect apart from the few hospitals with very low volume. A Japanese study reported a similar conclusion, while volume was found to have effect in US hospitals.39 40 The effect is likely a result of the types of operations performed at the low-volume hospitals, compared with the other hospitals.

Our study is based on complete data from all Norwegian hospitals performing laparotomies. It was possible to track patients during transfers and reoperations at different hospitals. To the best of our knowledge, no similar study has been performed. NPR, the data source, has been validated for several disease categories with respect to identification of cases based on diagnoses and/or procedures, and found to have a very high degree of completeness, compared with Norwegian national medical quality registries.41–44 At the time of writing, the completeness of NPR, after 24 registries have been studied, ranges from 83.5% to 99.8%.24

We cannot exclude a residual imbalance in case mix, affecting PWD through eg, smoking or obesity, which are known risk factors. There is regional variation in the prevalence of smoking and obesity in Norway.45 Obesity is more prevalent in Northern Norway, where PWD rates are somewhat higher. However, in some other areas where obesity is less prevalent, the rates are similar. There is no consistent correspondence between the known variation in smoking among counties and PWD rates. Some surgical procedures are performed only at regional hospitals, and it is therefore possible that selection effects are present. In that case, one would expect larger changes in PWD rates after risk adjustment for operation type, which was not found. One potential source of error in our study is the completeness and correctness of coding in the NPR, particularly the coding of reclosure operations. The risk adjustment depends on data from previous hospitalisation and may not capture all comorbidities. Moreover, selection effects cannot not be ruled out. Differing policies for operations on patients with known risk factors, for example, obesity or smoking, would likely cause variation in PWD rates. Patients who die before reoperation or are managed by other means will not be registered. We believe that this applies to very few patients and would not influence our results. No attempt was made to identify main operation or operation intent, as this would require a classification effort outside the scope of the present study. No clinical details about surgical technique and patient condition were available. Therefore, the causes of the observed PWD rate variation could not be investigated.

Previous studies have shown that the quality indicator has high positive predictive value, but only moderate sensitivity.10 46 47Since we have used specific wound reclosure codes, similar to those used in previous studies, we expect a high positive predictive value in Norway as well. Conceivably, the sensitivity depends on the coding system, in particular the various alternative codes related to complications. Sensitivity in Norway may thus differ from that of other healthcare systems. A recent retrospective medical record study from neighbouring Sweden reports that 86.9% of wound dehiscences were reoperated.38 Norway has an activity-based system for financing hospitals, which is an incentive to report all reclosure operations.

Conclusions

Among Norwegian hospitals, there is a significant variation in PWD rate after laparotomies that cannot be explained by operation type, age, comorbidity or whether the admission was elective or acute. This warrants further investigation into possible causes, such as patient related factors, surgical technique, perioperative procedures or handling of complications, for example, wound infections. Some of these factors are known to be amenable.20 48 The relatively large between-hospital variation found in the present study is an indication of potential for improvement. The risk adjusted PWD rate after laparotomy is a candidate for use as a quality indicator for Norwegian hospitals, and will make it possible to identify hospitals with apparent quality problems. To achieve sufficient discrimination, however, 5-year data are desirable, making it more difficult to monitor changes in hospital performance resulting from quality improvement efforts. It lies outside the scope of the present study to perform a comprehensive validation of the PWD rate as a quality indicator suitable for public reporting. There are uncertainties and potential biases in the indicator, implying that it must be regarded as a signal for follow-up within hospitals, rather than giving a final verdict of inferior or superior quality. For reporting on surgical quality, several indicators should be used to give a balanced view of the different aspects of quality and patient safety.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AKL and OT conceived the study. DTK, TMH, OT and SH participated in data preparation. OT, SH and AKL contributed to the analysis. OT helped draft the manuscript. JH was responsible for the statistical analysis and final manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Norwegian Directorate of Health and the Norwegian Data Protection Authority.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Carinci F, Van Gool K, Mainz J, et al. Towards actionable international comparisons of health system performance: expert revision of the OECD framework and quality indicators. Int J Qual Health Care 2015;27:137–46. 10.1093/intqhc/mzv004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. OECD. Health Care Quality and Outcomes: OECD, 2018. Available: http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/health-care-quality-and-outcomes.htm (accessed 06 Jun 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hannan EL. Using mortality data for profiling hospital quality of care and targeting substandard care. J Soc Health Syst 1989;1:31–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller MR, Elixhauser A, Zhan C, et al. Patient Safety Indicators: using administrative data to identify potential patient safety concerns. Health Serv Res 2001;36(6 Pt 2):110–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. OECD. Health Care Quality Indicators - Patient Safety, 2018. Available: http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/hcqi-patient-safety.htm (accessed 06 Jun 2018).

- 6. OECD. Definitions for Health Care Quality Indicators 2016-2017 HCQI Data Collection: OECD, 2016;113. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deilkås ET, Risberg MB, Haugen M, et al. Exploring similarities and differences in hospital adverse event rates between Norway and Sweden using Global Trigger Tool. BMJ Open 2017;7:e012492 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hannan EL, Bernard HR, O’Donnell JF, et al. A methodology for targeting hospital cases for quality of care record reviews. Am J Public Health 1989;79:430–6. 10.2105/AJPH.79.4.430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Ramshorst GH, Nieuwenhuizen J, Hop WC, et al. Abdominal wound dehiscence in adults: development and validation of a risk model. World J Surg 2010;34:20–7. 10.1007/s00268-009-0277-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Romano PS, Mull HJ, Rivard PE, et al. Validity of selected AHRQ patient safety indicators based on VA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. Health Serv Res 2009;44:182–204. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00905.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosen AK, Itani KM, Cevasco M, et al. Validating the patient safety indicators in the Veterans Health Administration: do they accurately identify true safety events? Med Care 2012;50:74–85. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182293edf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kean J. The effects of smoking on the wound healing process. J Wound Care 2010;19:5–8. 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.1.46092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shanmugam VK, Fernandez SJ, Evans KK, et al. Postoperative wound dehiscence: Predictors and associations. Wound Repair Regen 2015;23:184–90. 10.1111/wrr.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sandy-Hodgetts K, Carville K, Leslie GD. Determining risk factors for surgical wound dehiscence: a literature review. Int Wound J 2015;12:265–75. 10.1111/iwj.12088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Røine E, Bjørk IT, Oyen O. Targeting risk factors for impaired wound healing and wound complications after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc 2010;42:2542–6. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stephan RN, Munschauer CE, Kumar MS. Surgical wound infection in renal transplantation: outcome data in 102 consecutive patients without perioperative systemic antibiotic coverage. Arch Surg 1997;132:1315–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sørensen LT, Hemmingsen U, Kallehave F, et al. Risk factors for tissue and wound complications in gastrointestinal surgery. Ann Surg 2005;241:654–8. 10.1097/01.sla.0000157131.84130.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mahey R, Ghetla S, Rajpurohit J, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for abdominal wound dehiscence. International Surgery Journal 2017;4:24–8. 10.18203/2349-2902.isj20163983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deerenberg EB, Harlaar JJ, Steyerberg EW, et al. Small bites versus large bites for closure of abdominal midline incisions (STITCH): a double-blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:1254–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60459-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Israelsson LA, Millbourn D. Prevention of incisional hernias: how to close a midline incision. Surg Clin North Am 2013;93:1027–40. 10.1016/j.suc.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Webster C, Neumayer L, Smout R, et al. Prognostic models of abdominal wound dehiscence after laparotomy. J Surg Res 2003;109:130–7. 10.1016/S0022-4804(02)00097-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bucknall TE, Cox PJ, Ellis H. Burst abdomen and incisional hernia: a prospective study of 1129 major laparotomies. Br Med J 1982;284:931–3. 10.1136/bmj.284.6320.931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gislason H, Søreide O, Viste A. Wound complications after major gastrointestinal operations. The surgeon as a risk factor. Dig Surg 1999;16:512–4. 10.1159/000018778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Health NDo. Norsk pasientregister - innhold og kvalitet: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2018. Available: https://helsedirektoratet.no/norsk-pasientregister-npr/innhold-og-kvalitet (accessed 12 Jun 2018).

- 25. eHealth NDo. Helsefaglige kodeverk: Norwegian Directorate of eHealth, 2018. Available: https://ehelse.no/standarder-kodeverk-og-referansekatalog/helsefaglige-kodeverk (accessed 06 Jun 2018).

- 26. Norwegian Directorate of eHealth. NCMP, NCSP og NCRP: Klassifikasjon av medisinske, kirurgiske og radiologiske prosedyrer Norwegian Directorate of eHealth, 2018. Available: https://finnkode.ehelse.no/#ncmpncsp/0/0/0/-1 (accessed 15 May 2018).

- 27. Hassani S, Lindman AS, Kristoffersen DT, et al. 30-Day Survival Probabilities as a Quality Indicator for Norwegian Hospitals: Data Management and Analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136547 10.1371/journal.pone.0136547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–82. 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. (HCUP) HCaUP. Beta Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10-CM/PCS: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2018. Available: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp (accessed 06 Jun 2018).

- 31. Firth D. Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika 1993;80:27–38. 10.1093/biomet/80.1.27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kristoffersen DT, Helgeland J, Clench-Aas J, et al. Observed to expected or logistic regression to identify hospitals with high or low 30-day mortality? PLoS One 2018;13:e0195248 10.1371/journal.pone.0195248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Albert A, Anderson JA. On the existence of maximum likelihood estimates in logistic regression models. Biometrika 1984;71:1–10. 10.1093/biomet/71.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guo W, Romano JP. On stepwise control of directional errors under independence and some dependence. J Stat Plan Inference 2015;163:21–33. 10.1016/j.jspi.2015.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chambers JM, Hastie TJ, (). Statistical models in S. Pacific Grove: Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paul P, Pennell ML, Lemeshow S. Standardizing the power of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test in large data sets. Stat Med 2013;32:67–80. 10.1002/sim.5525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kenig J, Richter P, Lasek A, et al. The efficacy of risk scores for predicting abdominal wound dehiscence: a case-controlled validation study. BMC Surg 2014;14:65 10.1186/1471-2482-14-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walming S, Angenete E, Block M, et al. Retrospective review of risk factors for surgical wound dehiscence and incisional hernia. BMC Surg 2017;17:19 10.1186/s12893-017-0207-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kitazawa T, Matsumoto K, Fujita S, et al. Perioperative patient safety indicators and hospital surgical volumes. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:117 10.1186/1756-0500-7-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hernandez-Boussard T, Downey JR, McDonald K, et al. Relationship between patient safety and hospital surgical volume. Health Serv Res 2012;47:756–69. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01310.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bakken IJ, Gystad SO, Christensen ØO, et al. Comparison of data from the Norwegian Patient Register and the Cancer Registry of Norway. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2012;132:1336–40. 10.4045/tidsskr.11.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Høiberg MP, Gram J, Hermann P, et al. The incidence of hip fractures in Norway -accuracy of the national Norwegian patient registry. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:372 10.1186/1471-2474-15-372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Øie LR, Madsbu MA, Giannadakis C, et al. Validation of intracranial hemorrhage in the Norwegian Patient Registry. Brain Behav 2018;8:e00900 10.1002/brb3.900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Varmdal T, Bakken IJ, Janszky I, et al. Comparison of the validity of stroke diagnoses in a medical quality register and an administrative health register. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:143–9. 10.1177/1403494815621641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Health NIoP. Public Health report: Norwegian Institute of Public Health, 2018. Available: https://www.fhi.no/en/op/hin/ (accessed 06 Jun 2018).

- 46. Cevasco M, Borzecki AM, McClusky DA, et al. Positive predictive value of the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicator “postoperative wound dehiscence”. J Am Coll Surg 2011;212:962–7. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Borzecki AM, Cevasco M, Mull H, et al. Improving the identification of postoperative wound dehiscence missed by the Patient Safety Indicator algorithm. Am J Surg 2013;205:674–80. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg 2017;152:784–91. 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026422supp001.pdf (791.8KB, pdf)