Abstract

Objective

The role of primary care providers (PCP) in the cancer care continuum is expanding. In the post-treatment phase, this role is increasingly recognised by policy makers and healthcare professionals. During treatment, however, the role of PCP remains largely undefined. This systematic review aims to map the content and effect of interventions aiming to actively involve the general practitioner (GP) during cancer treatment with a curative intent.

Study design

Systematic review.

Participants

Patients with cancer treated with curative intent.

Data sources

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCT), controlled before and after studies and interrupted time series focusing on interventions designed to involve the GP during curative cancer treatment were systematically identified from PubMed and EMBASE and were subsequently reviewed. Risk of bias was scored according to the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group risk of bias criteria.

Results

Five RCTs and one CCT were included. Interventions and effects were heterogeneous across studies. Four studies implemented interventions focussing on information transfer to the GP and two RCTs implemented patient-tailored GP interventions. The studies have a low–medium risk of bias. Three studies show a low uptake of the intervention. A positive effect on patient satisfaction with care was found in three studies. Subgroup analysis suggests a reduction of healthcare use in elderly patients and reduction of clinical anxiety in those with higher mental distress. No effects are reported on patients’ quality of life (QoL).

Conclusion

Interventions designed to actively involve the GP during curative cancer treatment are scarce and diverse. Even though uptake of interventions is low, results suggest a positive effect of GP involvement on patient satisfaction with care, but not on QoL. Additional effects for vulnerable subgroups were found. More robust evidence for tailored interventions is needed to enable the efficient and effective involvement of the GP during curative cancer treatment.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018102253.

Keywords: primary care, shared care, curative treatment, patient satisfaction, general practitioner, cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first review that systematically reviews evidence-based interventions, aiming at general practitioner involvement during the curative treatment phase of the cancer care continuum.

The electronic database search was performed without restriction on languages and period.

We evaluate the studies with the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group risk of bias tool, which is the most appropriate tool to assess bias for complex interventions.

The title/abstract screening is done by single reviewer, two authors screened the full text, and the search was complemented with reference checks of relevant articles.

The included studies are heterogeneous in intervention and outcome, and therefore strong conclusions could not be made.

Background

Cancer incidence and prevalence is increasing as a result of the ageing population combined with expanding diagnostic and treatment possibilities. Due to improved outcome following cancer treatment, the nature of cancer treatment is changing toward more chronic disease management. Health policy makers and healthcare professionals therefore call for a change in the way cancer care is provided, to focus on more integrated and personalised cancer care during and after treatment.1 2 In countries with gatekeeper healthcare systems, such as The Netherlands, general practitioners (GPs) are generally the coordinators of care, who have a longstanding and personal relationship with their patients. This enables knowledge of both the medical and personal situation of the patient and care, which is provided in a trusted environment with a familiar healthcare worker. Therefore, primary care is increasingly promoted as the preferred setting to provide integrated support during and after active cancer treatment, both to meet patient preference and to stabilise costs.2 3 The concept of shared care has been suggested as the way forward in the organisation of integrated cancer care.2 3 This shared care model is an organisational model involving both GPs and specialists in a formal, explicit manner. Shared care models enhance the optimal access of patients to both hospital care and community-based supportive care along the entire cancer care continuum.4 In shared care models, GPs, along with other primary care professionals, add their competence to balance the biomedical aspects of cancer care with the psychosocial context and preferences of the individual patient,5 ensuring personalised, integrated care. To achieve shared care, the GP should be involved in the organisation of care during cancer treatment.

Traditionally, the role of primary care in palliative and end-of-life care is well established.6 In addition, evidence suggests a solid role for primary care in cancer follow-up after treatment and survivorship care.7–9 Less well appreciated, however, is primary care involvement during cancer treatment, particularly for patients treated with a curative intent. It is well established that in this phase, patients frequently experience psychosocial distress and treatment-related side effects that negatively affect their quality of life.10 Several studies suggest primary care involvement during active treatment, to improve patient outcomes and to ensure continuity in guidance from primary care.3 11 In the near future, the GP might even be involved in treatments in primary care such as chemotherapy or hormone therapy. Currently, however, involvement of primary care is generally restricted to supportive care during cancer treatment.

So far, the most effective approach to involve primary care during cancer treatment remains unclear.

This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the content and effect of interventions aiming at active involvement of the GP during cancer treatment with curative intent compared with usual care.

Methods

Data source and search

A literature search was conducted in PubMed and EMBASE for articles describing randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs), controlled before and after studies and interrupted time series published in any language until the 3 July 2018. We used a search strategy that was previously applied in a review assessing continuity of care in the follow-up of patients with cancer.12 Subsequently, this strategy was adapted for completeness and relevance based on sequential testing of search strategies to develop our final search strategy. The details of the sequential and final search strategies are listed in online supplementary appendix A. The search terms include keywords and controlled vocabulary terms surrounding the central themes ‘general practitioner’, ‘primary care’, ‘oncology’ and ‘care’. Outcome measures and comparing study arm were not included in the selection criteria to widen the scope of the review. Instead of a database-integrated filter, a tailored methodological search filter was used to limit retrieval to appropriate study design.12 We reviewed references of selected articles for additional papers.

bmjopen-2018-026383supp001.pdf (55KB, pdf)

Outcomes were included if they were related to the quality of healthcare (eg, healthcare use), the healthcare experience of: healthcare professionals, informal caregivers and patients, or outcomes at the patient-level, with a focus on, for example, disease, quality of life and psychosocial impact.

Study selection

Articles were selected if they described an intervention; (1) for patients with cancer, (2) starting during curative treatment, (3) evaluating involvement of the GP and (4) tested in a randomised controlled setting, CCT, controlled before and after studies or interrupted time series. Studies with a majority (>75%) of curative patients were included. In case, the proportion of curative patients was unclear, the original authors were contacted. Without response, the inclusion of the trial was based on >75% patient survival during the trial.

Data extraction and management

To determine relevance, the records were divided and screened on title and abstract by two single reviewers (IP,JB) and discussed with three additional reviewers in case of doubt (AM,CH and JB or IP). Two authors (IP,JB) performed full-text screening. Disagreements on eligibility were resolved in group discussion with researchers and clinicians (IP,JB,AM,CH). A meta-analysis was planned to be conducted if possible.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design of the current study.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias for individual studies was scored by two authors (JB,IP) with the risk of bias criteria from the “Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC), which is a Cochrane review group.13 In case outcomes of homogeneous study designs could be merged, we rated the body of the evidence following the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach (GRADE)14 from the Cochrane collaboration. This systematic review is reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2009 checklist.15

Results

Study selection

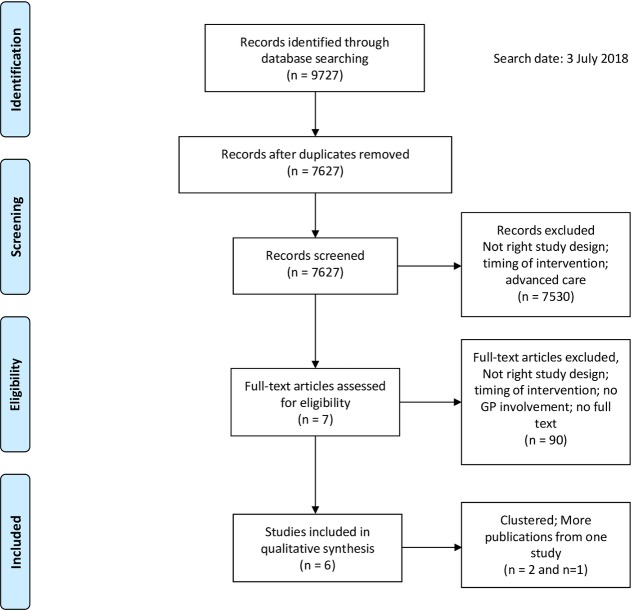

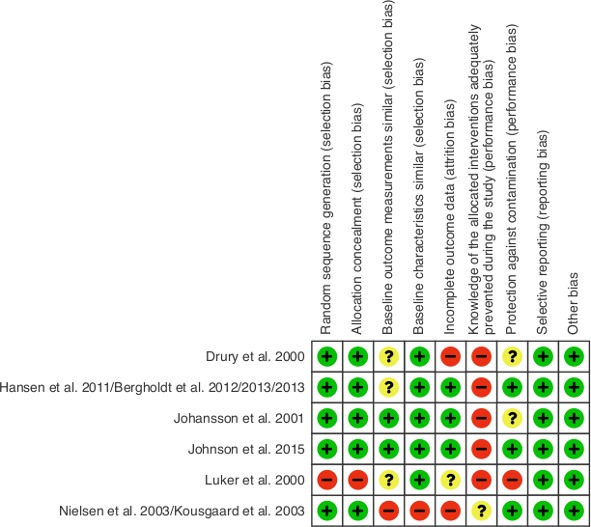

As shown in figure 1, 7627 records were eligible for inclusion after removal of duplicates. Title and abstract screening yielded 97 articles. Of these, 90 were excluded after full-text screening. Main reasons for exclusion were (1) insufficient involvement of the GP, (2) GP involvement started after completion of primary cancer treatment or (3) no RCT, CCT, controlled before and after study or interrupted time series design was used. Three studies published multiple articles based on the same data.16–23 As a result, five RCTs and one CCT were considered eligible for inclusion, which were described in 10 articles. No additional eligible studies were identified in the reference lists of selected studies. Figure 2, tables 1 and 2 show a detailed account of the risk of bias, patient population, interventions, outcomes assessed and observed results for each study. Given the various research questions, interventions and heterogeneity of outcome measures, pooling of data and GRADE assessment were not feasible.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies, based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.15 GP, general practitioner.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias measured according to the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group criteria.

Table 1.

Details of interventions aiming at active involvement of the GP during treatment with curative intent

| Reference, Country |

Population n=number, Cancer origin, Stage |

Timing of: Inclusion, Intervention, Follow-up |

Nature of the intervention and comparison groups |

| Drury et al

25

UK |

n=650 60% ♀ MAM (33%), LUN, GI, GYN, URO, H&N, other (13%); Cancer stage not specified. 59 patients died ≤3 months from baseline, which may reflect inclusion of patients with advanced disease. |

Inclusion

During any RT clinic visit Time after diagnosis not specified Intervention On enrolment Follow-up 3 months |

UC and intervention vs UC Patients received a PHR Initiative GP contact: Patient PHR: A4 size plastic wallet content:

|

| Bergholdt et al Hansen et al

18–21

Denmark |

n=955 72% ♀ MAM (43%), LUN, GI, other (19%), MEL Cancer stage unknown, no deceased |

Inclusion

Cancer diagnosis<3 months Intervention On enrolment Follow-up 14 months |

Intervention vs UC Rehabilitation primary care programme Initiative GP contact: Healthcare worker Rehabilitation primary care programme consisting of:

|

| Johansson et al

23

Sweden |

n=463 57% ♀ MAM (47%), GI, PRO 22% with advanced disease. |

Inclusion

Newly diagnosed patients (<3 months after diagnosis) Intervention On enrolment Follow-up 3 months |

Intervention vs UC Intensified primary care programme Initiative GP contact: Healthcare worker Individual support intervention consisting of:

|

| Johnson et al

26

Australia |

n=97 Stopped early (slow accrual); underpowered for the main analysis. 86% ♀ MAM (76%), HEM, GYN, GI Cancer stage 3.3% palliative |

Inclusion

During first course of CT Intervention First through last course of CT Follow-up 6 cycles of CT |

UC and intervention vs UC (discharge summary) Shared care programme+PHR Initiative GP contact: Patient PHR content:

|

| Luker et al

24

UK |

n=79 100% ♀ MAM (100%) Cancer stage 100% curative |

Inclusion

<4 weeks after diagnosis Intervention At start of treatment Follow-up 4 months |

UC and intervention vs UC Patients received information cards Initiative GP contact: Patient Information card content:

|

| Nielsen et al

16

Kousgaard et al 17 Denmark |

N = 248 64% ♀ MAM(39%), GI, GER, GYN, H&N, LUN, others (16%), MEL Cancer stage 15% palliative |

Inclusion

Newly diagnosed patients Intervention From referral onwards; during treatment Follow-up 6 months |

UC and intervention vs UC Shared care programme Initiative GP contact: Patient Oncologists provided GP with a discharge summary with:

|

CT, chemotherapy; GER, germinal cell; GI, gastrointestinal tract; GP, general practitioner; GYN, gynaecological; HEM, haematological; H&N, head and neck; LUN, lung; MAM, mamma; MEL, melanoma; PHR, patient held record; PRO, prostate; RC, rehabilitation coordinator; RT, radiotherapy; UC, usual care; UK, United Kingdom; URO, urogenital; vs, versus.

Table 2.

Study results for interventions aiming at active involvement of the GP during curative intent

| Reference, Country |

Primary and secondary outcome measures (instrument used), Timing of measurement |

Findings if applicable to study: 1. Uptake of intervention 2. Healthcare use 3. Patient-related outcomes 4. GP-related outcomes |

| Drury et al 25 |

Primary

Single measurement at 3 months |

Uptake of intervention 27.3% of 202 responding GPs had seen the PHR Healthcare use (intervention vs. control)

|

| Bergholdt et al

Hansen et al 20 |

Primary

Quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30) Secondary

At 6 and 14 months |

Uptake of intervention proactivity of GP intervention vs control: GP reported 61.2% vs 55.2% p=0.10, patient reported 60.1% vs 51.9% p=0.15. Patient-related outcomes (intervention vs control)

|

| Johansson et al 23 |

Primary

Healthcare use:

Single measurement at 3 months |

Uptake of intervention Not reported Healthcare use (intervention vs. control)

|

| Johnson et al 26 |

Primary

|

Uptake of intervention Not reported Healthcare use (intervention vs. control)

|

| Luker et al 24 |

Primary

|

Uptake of intervention 8 of the 31 interviewed GPs recall seeing the information card Healthcare use (intervention vs. control)

|

| Nielsen et al

16

Kousgaard et al 17 |

Primary

Patient:

|

Uptake of intervention Not reported Patient-related outcomes (intervention vs control)

|

CA, clinically anxious; CT, chemotherapy; Dan-PEP, Danish Patients Evaluate General Practice; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General; GP, general practitioner; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; Mini-MAC, Mini Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale; NA-ACP, Needs Assessment for Advanced Cancer Patient; NS, not significant, no p-value or CI was provided nor could be calculated; OR adj, OR ratio adjusted for confounders sex and age; PACIC, Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care; PES, Patient Empowerment Scale; PHR, Patient Held Record; POMS, Profile of Mood States; SDQ, Self Developed Questionnaire; SCNS-SF34, Supportive Care Needs Survey Short Form 34; UC, usual care; y, years of age.

Quality of studies

The EPOC risk of bias is presented in figure 2. Luker et al 24 and Nielsen/Kousgaard et al 16 17 show a high risk of bias, resulting from high risk of selection and information bias.16 17 24 Drury et al 25 scored a medium risk of bias.25 And the studies of Johnson et al,26 Johansson et al 23 and Bergholdt et al show a low risk of bias.18–20 23 26 Regarding the RCT by Nielsen/Kousgaard et al 16 17 several limitations should be kept in mind. The randomisation produced an imbalance, which influenced comparability of outcomes between study groups without corresponding correction in the analyses. Furthermore, it was not reported whether a baseline measurement was performed and the exact timing of the first measurement (table 2). Also, the percentage of missing data was 33% in the intervention and 26% in the control group.16

Study populations

The six eligible studies were conducted in Europe (five) and Australia (one) among different cancer patient populations over the past two decades. Patients with breast cancer were the most commonly studied group (between 33% and 100% of the study populations). Five RCTs included patients with more than one type of cancer, in different stages. Three studies included palliatively treated patients (<25% of total study population). In two, RCT’s cancer stage was not specified.

Usual care

In most studies, usual care was not described in detail. Only Luker et al 24 described the structured care that usual care patients received, which included home visits from a breast care nurse and written patient information on treatments. In general, the patient’s GP received a discharge summary16–18 20 21 26 at the end of the treatment period16 17 or after each visit.26 Other types of transferred information to the GP included an extract of the hospital record16 17 or communication by telephone.26 Two studies did not describe what usual care entailed.22 23 25

Type of interventions

All participants received usual care, which was extended when the participant was appointed to the intervention. The interventions in the studies (table 1) were heterogeneous, but can be divided in mainly information transfer to the GP (n=4)16 17 24–26 and tailored primary care interventions (n=2).18–21 23

Interventions focusing on information transfer, provided additional, disease-specific educational and practical information concerning treatment and care directly to the GP or via the patient. Interventions were either directed at enhancing communication between GP and another party (ie, secondary care or patient), or directed at improving patient’s attitude towards the healthcare system (ie, healthcare in general or intervention), physical or psychological complains. Three interventions provided patients with information, which was to be transferred to the GP. In one CCT,24 informational cards were provided to the patients for use in primary care. Two other RCTs described an intervention with a Patient Held Record (PHR)25 26 aimed to facilitate intersectoral communication, to provide patients with an aide memoire and with the opportunity to stay actively involved in their treatment. One RCT supplied the GP with patient-specific discharge summaries by secondary care, aiming to enhance GP knowledge of chemotherapy treatment and expected adverse effects.16 17

The tailored primary care interventions aimed to support patients in managing their disease and treatment.18 19 21 23 The interventions were to diverse to be merged and they are therefore described separately. In Johansson et al, 23 primary care was intensified by means of recruitment of a home care nurse, psychologist, dietician and training of the GP. The home care nurse initiated contact. The GP was regularly informed by the specialist and educated on management of patients with cancer. In the one RCT from Hansen et al and Bergholdt et al,18–21 a rehabilitation team interviewed all patients on different aspects of rehabilitation. Afterwards the GP was informed on patient-specific rehabilitation needs and encouraged to proactively contact the patient to support the patient in his/her needs.

Study outcomes

The most often measured primary outcomes were healthcare utilisation16 17 23–25 and quality of life,16–18 25 as presented in table 2. Other outcomes consisted of patient and GP perceptions of care, symptoms, coping and empowerment. The following outcomes were not presented in the included articles: healthcare experience by informal caregivers and disease-specific outcomes (ie, progress, mortality). Outcomes are described in more detail below.

Intervention fidelity/compliance and healthcare use

Healthcare use is related to the uptake of the intervention. For example, if the intervention aims at more GP involvement, healthcare use is likely to increase. Although all interventions aimed at increased involvement of primary care, four interventions did not show a significant increase of GP consultations.16 19 24 25 Correspondingly, the uptake of interventions appeared to be low in the majority of the studies. This is illustrated by Bergholdt et al 19 which describes an ‘active involvement’ intervention, in which GP proactivity was comparable to GP proactivity in the control group (60% versus 52%, OR adjusted for sex and age 1.44 95%CI 0.80-2.36).19 In two studies, information transfer to the GP by their patients was hardly used or remembered by the majority of the GPs.24 25

Five studies, evaluated the effect of the intervention on hospital and/or primary care resource use. These studies showed no significant effect on secondary care healthcare use.23–25 Only the subgroup of older patients (≥70 years of age) had a significantly lower use of secondary care23 when primary care was actively involved. Even though GP consultations where part of the interventions, several studies reported no difference in the number of GP consultations in the intervention group compared with the control group.16 17 24–26

Patient perception

Positive effects on patients’ satisfaction with care were indicated by three studies. Extended information by PHR or discharge summary improved patient perceived intersectoral cooperation.16 17 GP consultations were evaluated as useful. Also patients reported that ‘the GP could help in the way a specialist could not’.26 Regardless of the uptake of the intervention, one study showed an improved satisfaction with communication and participation with care.25 The significantly higher levels of perceived GP support shortly after the intervention described in Nielsen et al 16 declined to non-significant levels at 6 months after start of intervention. The authors did not present a mean difference overtime. One study with a low uptake of intervention showed no significant effect on patients satisfaction.21

Quality of life and psychological outcomes

No study found a significant effect on quality of life.16 18 25 Johnson et al,24 showed a significant difference in change of depression scores (p0.04). In the intervention group, depression scores remained unchanged, whereas scores in the control group, deteriorated significantly. Also, using a PHR combined with routine visits to the GP led to a significantly higher reduction of the number of clinically anxiousness patients compared with usual care.26

GPs perceptions of care

Four out of five studies evaluating effects on GPs perceptions of care did not find relevant effects on GP’s confidence in disease management and knowledge nor in the communication with the specialist.17 21 24 26 Studies in which information was carried by the patient (a PHR or informational cards) showed little impact on GP satisfaction with care mostly due to low uptake of intervention. Only Nielsen/Kousgaard et al 16 17 found significant positive effects on GP perceived intersectoral cooperation and GP satisfaction with information.

Discussion

This systematic review shows that published research describing the effect of interventions designed to involve the GP during curative cancer treatment is scarce. The six studies that were published evaluate either additional information transfer to the GP or tailored primary care. In general, the intervention uptake was low, and the risk of bias was low to moderate. Results indicate a positive effect of increased GP involvement in cancer care on patient satisfaction with care but not on quality of life. In subgroups, it may lower healthcare use and anxiety.

Even though active involvement of the GP during cancer treatment might have positive effects, implementation appears to be difficult to realise. This is seen for all interventions, irrespective whether the GP contact is initiated by the patient or by the healthcare provider. This shows that finding a feasible intervention is challenging. Drury et al 25 suggested that a reason for the low uptake might be that GPs are not motivated to participate in the care of patients with curative disease as they do not feel closely involved in this stage.25 This may explain why no studies were found where the GP was the initiator of involvement in care during cancer treatment. Low GP motivation is in contrast to what Dossett et al 27 show in their review on communication of specialist and GP during the cancer care continuum, they state that GPs desire involvement but think that specialist and patient prefer a specialist-based instead of shared-based cancer care.27 Dossett et al 27 confirms a preference of a specialist-based model of care by specialists, which may result in a low motivation to activate the patient to see the GP.27 Another reason for low uptake may be the difficulty to promote proactivity by GPs.18 19 Dossett et al 27 suggest that an adequate relationship and communication between the specialist and GP are important elements for the success of an intervention.27 These findings suggest that, when designing an intervention, raising support of both primary and secondary healthcare workers is vital. The fact that healthcare systems have different challenges and needs (eg, communication between caregiver or distance to healthcare services), strengthens the need to tailor the potential solutions to local needs.

Specific subgroups may benefit more from involvement of primary care. A stronger decrease in anxiety was reported in patients with elevated levels of anxiety26 andthe GP involvement led to a reduction in secondary care use among older patients.23 It has been suggested that different cancer diagnoses bring different psychological burdens and care needs,28 but this could not be concluded from this review.

This review has several limitations. To provide a comprehensive overview, we used a broad research question and search strategy. Consequently, we included heterogeneous studies. Due to this heterogeneity and the low number of available studies, data pooling was not possible, and the estimate of effect could not be assessed according to the GRADE approach. To add to the difficulty of reviewing heterogeneous studies, most studies addressed complex interventions. The challenge of providing an overview of such studies could partly be countered by the limited availability of process measures (eg, uptake of intervention), but still strong conclusions could not been drawn. Another potential limitation is that two databases were used to screen on title and abstract by one researcher, possibly leading to missing studies. However, since screening of references did not provide additional studies, we expect this limitation to be without effect. In addition, to be complete, we included studies that also included palliatively treated patients. Some publications did not show separate results for the curatively and palliatively treated population. We used a threshold for the minimum proportion of curatively treated patients (ie, 75%), but we cannot exclude that the observed effects were influenced the inclusion of palliative patients. Finally, the review relied solely on published studies, so we cannot exclude publication bias.

Current literature shows several important challenges for designing and studying interventions which effectively involve GPs in cancer care. First, finding a feasible intervention seems challenging. Second, when designing an intervention, raising support of primary and secondary healthcare workers seems vital. Third, challenges and solutions may be setting and population specific. For these reasons, exploratory research seems necessary to design feasible and effective interventions and meaningful studies. Fourth, large studies with a robust design are needed, which should focus on the effect of primary care involvement for various populations, including specifications for cancer types and vulnerable populations (eg, elderly and patients with physical or mental comorbidity).

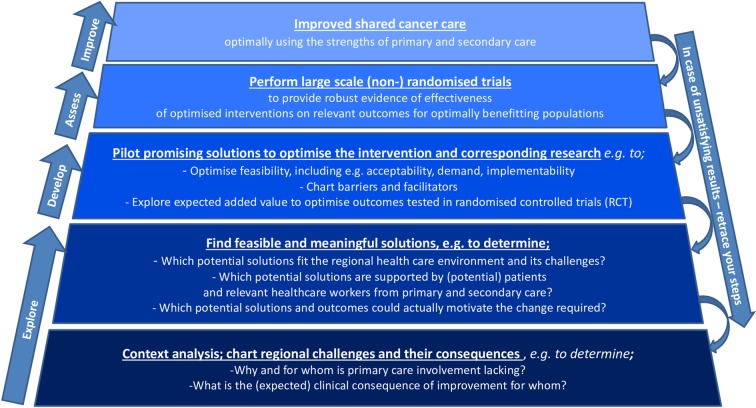

Based on the findings in this review and guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions29 and feasibility studies,30 we propose a framework, which describes consecutive steps that can guide the future development of effective interventions (figure 3). In this framework, each step is aimed to provide a foundation for the next step, thereby providing a stepwise approach to feasible and meaningful involvement of the GP in cancer care. This framework should support us in finding definitive answers on the effects of GP involvement in the cancer care pathway in different healthcare settings, for a variety of populations. Interventions based on the framework should optimally facilitate primary care workers to appropriately implement their role in shared care, by making full use of their specific expertise by consideration of the patients’ context and values, provided in a trusted environment.

Figure 3.

Framework for development of interventions aimed to effectively involve the GP in cancer care. In this framework, each step is aimed to provide a foundation for the next step, thereby providing a stepwise approach to feasible and meaningful involvement of the GP in cancer care. GP, general practitioner.

Conclusion

Literature addressing the effects of interventions designed to actively involve the GP during curative cancer treatment is scarce, and the results are diverse. Even though uptake of interventions is generally low, these studies suggest positive effects of increased primary care involvement on patient satisfaction. Other positive effects were seen, particularly for vulnerable populations. In view of various healthcare strategies, which aim to transfer parts of the cancer care paths from secondary to the primary care, it is adamant to gather more robust evidence for customised interventions to enable the efficient and effective involvement of the GP during cancer treatment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship. JAB, IAAP: acquisition of data. IAAP, JAB, AMM, CWH: analysis and interpretation of data. IAAP, JAB, AMM, NW, EW, CWH: conception and design of the study, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: For the current study, we did not generate new data. Therefore, sharing new data is not possible.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Kankerbestrijding SK van KWF. Nazorg bij kanker: de rol van de eerstelijn. Amsterdam: KWF Kankerbestrijding, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, et al. . The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1231–72. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00205-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campbell NC, MacLeod U, Weller D. Primary care oncology: essential if high quality cancer care is to be achieved for all. Fam Pract 2002;19:577–8. 10.1093/fampra/19.6.577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith SM, Cousins G, Clyne B, et al. . Shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in management of long term conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:CD004910 10.1002/14651858.CD004910.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Royal College of General Practitioners. Medical generalism 2013:1–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ramanayake RPJC, Dilanka GVA, Premasiri LWSS. Palliative care; role of family physicians. J Family Med Prim Care 2016;5:234–7. 10.4103/2249-4863.192356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grunfeld E, Fitzpatrick R, Mant D, et al. . Comparison of breast cancer patient satisfaction with follow-up in primary care versus specialist care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Emery JD, Shaw K, Williams B, et al. . The role of primary care in early detection and follow-up of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014;11:38–48. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ngune I, Jiwa M, McManus A, et al. . Do Patients Treated for Colorectal Cancer Benefit from General Practitioner Support? A Video Vignette Study. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e249 10.2196/jmir.4942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pascoe SW, Neal RD, Allgar VL, et al. . Psychosocial care for cancer patients in primary care? Recognition of opportunities for cancer care. Fam Pract 2004;21:437–42. 10.1093/fampra/cmh415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kendall M, Boyd K, Campbell C, et al. . How do people with cancer wish to be cared for in primary care? Serial discussion groups of patients and carers. Fam Pract 2006;23:644–50. 10.1093/fampra/cml035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aubin M, Giguère A, Martin M, et al. . Interventions to improve continuity of care in the follow-up of patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD007672 10.1002/14651858.CD007672.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. 2017. http://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors.

- 14. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. . GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nielsen JD, Palshof T, Mainz J, et al. . Randomised controlled trial of a shared care programme for newly referred cancer patients: bridging the gap between general practice and hospital. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:263–72. 10.1136/qhc.12.4.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kousgaard KR, Nielsen JD, Olesen F, et al. . General practitioner assessment of structured oncological information accompanying newly referred cancer patients. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003;21:110–4. 10.1080/02813430310001725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bergholdt SH, Larsen PV, Kragstrup J, et al. . Enhanced involvement of general practitioners in cancer rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000764 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bergholdt SH, Søndergaard J, Larsen PV, et al. . A randomised controlled trial to improve general practitioners' services in cancer rehabilitation: effects on general practitioners' proactivity and on patients' participation in rehabilitation activities. Acta Oncol 2013;52:400–9. 10.3109/0284186X.2012.741711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hansen DG, Bergholdt SH, Holm L, et al. . A complex intervention to enhance the involvement of general practitioners in cancer rehabilitation. Protocol for a randomised controlled trial and feasibility study of a multimodal intervention. Acta Oncol 2011;50:299–306. 10.3109/0284186X.2010.533193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bergholdt SH, Hansen DG, Larsen PV, et al. . A randomised controlled trial to improve the role of the general practitioner in cancer rehabilitation: effect on patients' satisfaction with their general practitioners. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002726 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johansson B, Berglund G, Glimelius B, et al. . Intensified primary cancer care: a randomized study of home care nurse contacts. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:1137–46. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johansson B, Holmberg L, Berglund G, et al. . Reduced utilisation of specialist care among elderly cancer patients: a randomised study of a primary healthcare intervention. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:2161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luker K, Beaver K, Austin L, et al. . An evaluation of information cards as a means of improving communication between hospital and primary care for women with breast cancer. J Adv Nurs 2000;31:1174–82. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Drury M, Yudkin P, Harcourt J, et al. . Patients with cancer holding their own records: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:105–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson CE, Saunders CM, Phillips M, et al. . Randomized Controlled Trial of Shared Care for Patients With Cancer Involving General Practitioners and Cancer Specialists. J Oncol Pract 2015;11:349–55. 10.1200/JOP.2014.001569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dossett LA, Hudson JN, Morris AM, et al. . The primary care provider (PCP)-cancer specialist relationship: A systematic review and mixed-methods meta-synthesis. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:156–69. 10.3322/caac.21385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh RP, Singh H, Singh CJ, et al. . Screening of Psychological Distress in Cancer Patients During Chemotherapy: A Cross-sectional Study. Indian J Palliat Care 2015;2121:3055–10. 10.4103/0973-1075.164887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. . How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:452–7. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026383supp001.pdf (55KB, pdf)