Arabidopsis, which does not normally emit isoprene, was engineered to emit isoprene, and growth and development as well as gene expression were analyzed to determine how isoprene affects plants.

Abstract

Isoprene synthase converts dimethylallyl diphosphate to isoprene and appears to be necessary and sufficient to allow plants to emit isoprene at significant rates. Isoprene can protect plants from abiotic stress but is not produced naturally by all plants; for example, Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) do not produce isoprene. It is typically present at very low concentrations, suggesting a role as a signaling molecule; however, its exact physiological role and mechanism of action are not fully understood. We transformed Arabidopsis with a Eucalyptus globulus isoprene synthase. The regulatory mechanisms of photosynthesis and isoprene emission were similar to those of native emitters, indicating that regulation of isoprene emission is not specific to isoprene-emitting species. Leaf chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were enhanced by isoprene, which also had a marked positive effect on hypocotyl, cotyledon, leaf, and inflorescence growth in Arabidopsis. By contrast, leaf and stem growth was reduced in tobacco engineered to emit isoprene. Expression of genes belonging to signaling networks or associated with specific growth regulators (e.g. gibberellic acid that promotes growth and jasmonic acid that promotes defense) and genes that lead to stress tolerance was altered by isoprene emission. Isoprene likely executes its effects on growth and stress tolerance through direct regulation of gene expression. Enhancement of jasmonic acid-mediated defense signaling by isoprene may trigger a growth-defense tradeoff leading to variations in the growth response. Our data support a role for isoprene as a signaling molecule.

Isoprene (2-methyl-1,3-butadiene), the lowest molecular weight hydrocarbon in the terpene family, is released by some but not all plants (Sharkey et al., 2008). Isoprene is synthesized by the methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in the chloroplast stroma, and the conversion of dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMADP) to isoprene is catalyzed by isoprene synthase (ISPS; Silver and Fall, 1995; Miller et al., 2001; Sharkey et al., 2013). Production of DMADP by the MEP pathway requires two substrates derived from the Calvin-Benson cycle, pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. Therefore, the rate of isoprene synthesis is dependent on photosynthesis and is driven by environmental factors such as light, temperature, and [CO2] (Monson and Fall, 1989; Sharkey and Yeh, 2001; Sanadze, 2004; Sun et al., 2013a, 2013b). Abiotic stress conditions such as drought and salt stress increase isoprene synthesis, while ozone decreases isoprene synthesis in plants expressing ISPS (Loreto and Delfine, 2000; Genard-Zielinski et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2016).

The carbon (C) and energy cost of isoprene production has been found to vary depending on the plant species and environmental conditions. For example, trees that normally produce isoprene, such as eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides), consume about 2% (Schnitzler et al., 2010; Way et al., 2011), while kudzu (Pueraria montana) can consume up to 64% (Sharkey and Loreto, 1993) of photosynthetic C for isoprene production. Under high temperature, C consumption for isoprene synthesis increases: gray poplar (Populus × canescens) at 42°C (Way et al., 2011) and oak (Quercus robur) at 40°C (Way et al., 2013) release about 25% and 14% of photosynthesized C as isoprene, respectively. In addition, the energy expenditure required for isoprene production is quite high. One isoprene molecule made via the MEP pathway requires 20 ATP and 14 NADPH (Sharkey and Yeh, 2001). The fact that the ISPS gene and the ability to synthesize isoprene were evolutionarily retained in some plants despite the comparatively high C and energy demand associated with isoprene production has been interpreted to indicate that isoprene is likely beneficial, although perhaps only in some species and under specific environmental conditions (Monson et al., 2013; Sharkey, 2013). Phylogenetic analyses show that, while present in ancestral lines, including Glycine soja, ISPS was lost from Glycine max probably fairly recently during the domestication process (Sharkey et al., 2013). Understanding how isoprene affects plant growth and physiology will allow researchers to determine whether ISPS will be a beneficial trait to be reintroduced to plants, especially for the purpose of crop improvement.

In general, isoprene emission has been shown to protect plants from abiotic stress, such as high-temperature stress, exposure to ozone and other reactive oxygen species (ROS), and herbivory (Loreto et al., 2001; Loreto and Velikova, 2001; Affek and Yakir, 2002; Sasaki et al., 2007; Laothawornkitkul et al., 2008; Loivamäki et al., 2008; Vickers et al., 2009a; Loreto and Schnitzler, 2010; Centritto et al., 2014). Inhibition of the MEP pathway by fosmidomycin blocks isoprene synthesis in plants, enhancing sensitivity to high temperature and ozone and leading to more severe oxidative damage (Loreto and Velikova, 2001; Sharkey et al., 2001; Velikova and Loreto, 2005; Velikova et al., 2006). In contrast, when plants are fumigated with isoprene, they suffer less damage when exposed to ozone and oxidative stress and recover more rapidly from thermal stress than untreated controls (Singsaas et al., 1997; Loreto et al., 2001; Sharkey et al., 2001; Velikova et al., 2006).

However, while isoprene synthesis, regulation, and its role in plant stress tolerance have been studied for several decades, its exact physiological role and the mechanism of action are still not fully understood. For many years, the underlying mechanisms of the above protective roles of isoprene were hypothesized to be mainly through stabilizing thylakoid membranes (Sharkey and Singsaas, 1995; Singsaas and Sharkey, 1998, 2000; Owen and Peñuelas, 2005; Behnke et al., 2007; Vickers et al., 2009a; Velikova et al., 2011), dissipating excess energy absorbed by photosynthetic pigments (Sanadze, 2010; Pollastri et al., 2014), antioxidant properties and ozone quenching (Loreto et al., 2001; Affek and Yakir, 2002; Sharkey et al., 2008; Vickers et al., 2009b), and indirect effects on ROS signaling (Vickers et al., 2009a). However, recently, Harvey et al. (2015) showed that isoprene is normally present at very low concentration (about 60 isoprene molecules per million lipid molecules), and even at very high concentration it is unable to cause changes to membrane fluidity. Thus, at normal concentrations, isoprene is very unlikely to affect membrane stability, and it also is not an effective method for quenching ROS compared with molecules such as β-carotene that are present at higher levels and act at much faster rates than isoprene (Harvey et al., 2015; Harvey and Sharkey, 2016).

New evidence based on RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated suppression of isoprene emission in gray poplar (Behnke et al., 2010) and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) fumigated with isoprene (Harvey and Sharkey, 2016) shows that isoprene leads to changes in the expression of many gene networks important for stress responses and also plant growth. Isoprene has also been shown to cause changes in the proteome (Vanzo et al., 2016), metabolome (Way et al., 2013), and metabolic fluxes (Behnke et al., 2010; Ghirardo et al., 2014) in plants. Evidence that shows isoprene can affect ATP-synthase activity in thylakoid membranes in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS (Velikova et al., 2011) allowed the hypothesis that isoprene may interact with membrane-bound proteins to induce signal transduction networks (Harvey and Sharkey, 2016). When Arabidopsis plants were fumigated for 24 h with a physiologically relevant concentration (20 μL L−1) of isoprene, microarray analysis found altered expression of genes that code for proteins functionally associated with many pathways, such as photosynthetic light reaction machinery, cell wall synthesis, stress responses, flavonoid and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, etc. (Harvey and Sharkey, 2016). Based on these data, Harvey and Sharkey (2016) proposed that isoprene can act as a signaling molecule to alter gene expression and thereby bring about its effects on abiotic stress tolerance. The specific growth-related and stress-related signaling pathways likely affected by isoprene and specific genes of these pathways that are responsive to isoprene are not known.

The aim of this study was to investigate in detail the effects of isoprene on plant growth under normal environmental conditions in Arabidopsis transformed with a Eucalyptus globulus ISPS. Arabidopsis does not naturally produce isoprene. Our goal was to investigate the effects on the MEP pathway metabolome and photosynthesis and how isoprene emission is regulated under different environmental conditions when Arabidopsis is engineered to emit isoprene. We tested whether the effects of isoprene seen in Arabidopsis were common to other species by comparing our Arabidopsis model system with an isoprene-emitting tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) model system developed by Vickers et al. (2009b). Like Arabidopsis, tobacco does not naturally produce isoprene. We also carried out gene expression analyses and a comprehensive comparison of isoprene-responsive genes from three different systems: (1) Arabidopsis and (2) tobacco expressing ISPS as well as (3) nontransformed wild-type Arabidopsis fumigated with isoprene. In doing so, we hoped to gain insight into the mechanisms through which isoprene can affect stress responses in plants.

RESULTS

Characterization of Arabidopsis Transgenic Lines Expressing ISPS

Expression of the ISPS Transgene in Arabidopsis

Arabidopsis wild-type Columbia-0 (Col-0) plants were transformed with an ISPS gene from E. globulus with an Arabidopsis Rubisco small subunit promoter (rbcS-1A; At1g67090), because this ISPS has a high affinity for DMADP. Results from PCR analyses confirmed the presence of vector DNA without ISPS in EV-A1, EV-B3, and EV-F1 and the presence of the ISPS gene in A1, B2, B4, C1, C3, C4, and F2 lines (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Photosynthesis and Isoprene Emission

Photosynthesis rates were similar between lines carrying the ISPS gene and control lines (Fig. 1A). Significant rates of isoprene emission were detected in Arabidopsis lines carrying the ISPS gene (Fig. 1B). The Col-0 line and empty vector lines had trivial isoprene emission rates, although EV-F1 had a higher rate than the other empty vector lines. We believe this to be nonenzymatic conversion of DMADP to isoprene. Within isoprene-emitting lines, C3 and B4 exhibited lower rates of emission, A1 and F2 emitted moderate amounts of isoprene, and C1, C4, and B2 exhibited the highest rates of isoprene emission compared with the control lines.

Figure 1.

Carbon assimilation and isoprene emission in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS. Photosynthesis (A) and isoprene emission (B) were measured simultaneously in Arabidopsis wild-type Col-0, empty vector controls (EV-A2, EV-B3, and EV-F1), and lines expressing ISPS (C3, B4, A1, F2, C1, C4, and B2). Measurements were made on plants 45 to 47 d old. All transgenic lines belonged to the T3 generation. Values in graphs represent means ± se (n = 5–7 plants per line). Arabidopsis lines expressing ISPS that are significantly different from Col-0 and empty vector lines EV-A2 and EV-B3 are marked with asterisks: **, P < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test.

Plant Growth

Hypocotyls were taller (Fig. 2, A and B) and cotyledons were larger (Fig. 2, C and D) in seedlings of isoprene-emitting lines than the controls. Except C1, cotyledon area seemed to be largest in plants that produced the highest amounts of isoprene at maturity. This relationship was not seen in terms of hypocotyl elongation.

Figure 2.

Early seedling growth in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS. Comparison of hypocotyl length (A and B) and cotyledon size (C and D) in 7-d-old Arabidopsis wild-type Col-0, empty vector controls (EV-A2, EV-B3, and EV-F1), and lines expressing ISPS (C3, B4, A1, F2, C1, C4, and B2). All transgenic lines belonged to the T3 generation. Values in graphs represent means ± se. In B, n = 22 to 41 plants per line; in D, n = 12 to 26 plants per line. Arabidopsis lines expressing ISPS that are significantly different from Col-0 and empty vector lines EV-A2 and EV-B3 are marked with symbols: +, P < 0.1; *, P < 0.05; and **, P < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test. In D, C1 was only statistically different from Col-0, EV-B3, and EV-F1.

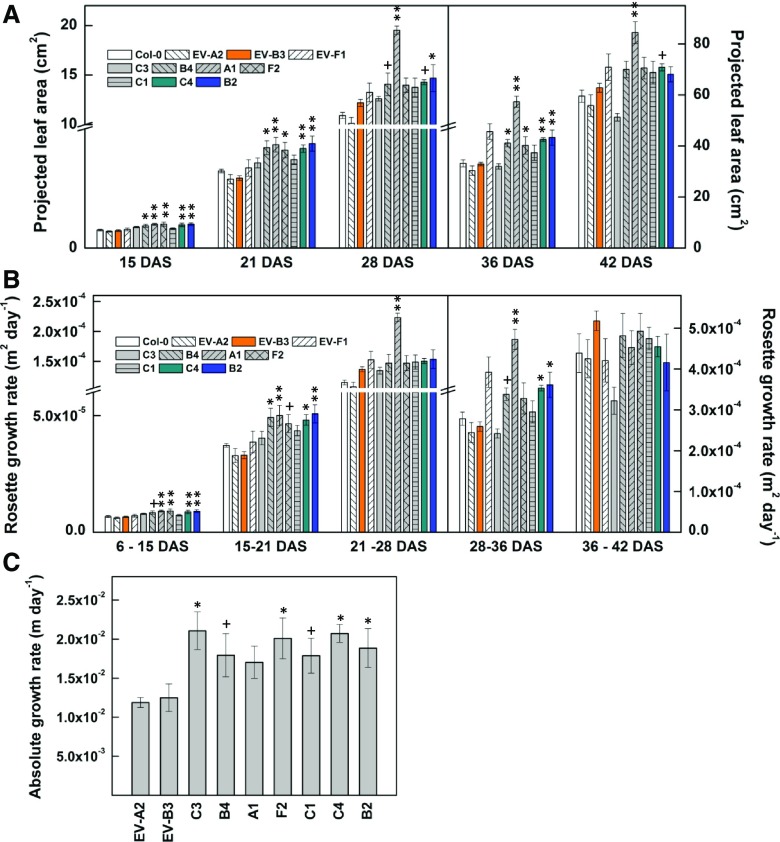

During the initial phenotypic characterization of the Arabidopsis mutant lines expressing ISPS, we focused mainly on rosette growth as a whole and rosette and stem growth rates. Projected leaf area (rosette area as seen from above with no correction for overlapping or curling leaves) was consistently larger in isoprene-emitting lines throughout the life cycle compared with the control lines (Figs. 3, A and B, and 4A). At maturity (50 d after seeding [DAS]), rosette dry weight was greater in F2, C4, and B2 compared with all control lines (Fig 3C). All isoprene-emitting lines except C3 exhibited greater total shoot dry weight than Col-0, EV-A2, and EV-B3 (Fig. 3D). In contrast to the wild type and other empty vector lines, EV-F1 showed a similarly increased shoot dry weight to the isoprene-producing lines (Fig. 3D). Most of the isoprene-emitting lines maintained higher rosette growth rates throughout their life span (Fig. 4B). In addition, stem growth rates were higher in isoprene-emitting lines than in EV-A2 and EV-B3 (Fig. 4C). Moreover, all isoprene-emitting lines flowered earlier than EV-A2 and EV-B3 (Fig. 3E) and produced taller inflorescences (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Rosette and inflorescence growth in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS. Photographs comparing rosette size and projected leaf area of 21-d-old (A) and 50-d-old (B) T3 plants, and leaf dry weight (C), shoot (leaf + inflorescence) dry weight (D), number of days required for inflorescence initiation (E), and height of the primary (1°) inflorescence axis (F) in 50-d-old Arabidopsis wild-type Col-0, empty vector controls (EV-A2, EV-B3, and EV-F1), and lines expressing ISPS (C3, B4, A1, F2, C1, C4, and B2), are shown. All transgenic lines belonged to the T3 generation. Values in graphs represent means ± se. In C and D, n = 4 to 8 plants per line; in E and F, n = 3 to 6 plants per line. Arabidopsis lines expressing ISPS that are significantly different from Col-0 and empty vector lines EV-A2 and EV-B3 are marked with symbols: +, P < 0.1; *, P < 0.05; and **, P < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test; in E and F, symbols denote statistical comparisons relative to only EV-A2 and EV-B3.

Figure 4.

Rosette and inflorescence stem growth rates in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS. Projected leaf area over time (A), absolute growth rates calculated as the increase in projected leaf area per day (B), and increase in the height of the primary inflorescence axis (stem) per day (C) are shown. All transgenic lines belonged to the T3 generation. Values in graphs represent means ± se. In A and B, n = 4 to 6 plants per line. In C, n = 3 to 5 plants per line. Arabidopsis lines expressing ISPS (C3, B4, A1, F2, C1, C4, and B2) significantly different from Col-0 and empty vector lines EV-A2 and EV-B3 are marked with symbols. +, P < 0.1; *, P < 0.05; and **, P < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test. In C, symbols denote statistical comparisons relative to only EV-A2 and EV-B3.

In summary, while the magnitude of growth enhancement was variable between the seven isoprene-emitting lines, isoprene had a consistent positive effect on early seedling growth and both vegetative and reproductive growth in Arabidopsis.

Comparison of the Isoprene-Emitting Arabidopsis and the Isoprene-Emitting Tobacco Model Systems

After characterization of the isoprene-emitting Arabidopsis lines, one of the empty vector lines (EV-B3) and the two lines that exhibited the highest rates of isoprene emission (B2 and C4) were selected for more in-depth growth analysis and comparison with tobacco azygous plants not emitting isoprene (NE) and transformed, isoprene-emitting (IE) lines to study in more detail the regulation of isoprene emission and photosynthesis under varying temperature, CO2, light and darkness, postillumination isoprene emission, MEP pathway metabolites, and growth. Data were compared among three systems: fumigated Arabidopsis, ISPS-transformed Arabidopsis, and ISPS-transformed tobacco. To find out if the observed effects were affected by growth light levels, Arabidopsis was grown under two light intensities: 100 and 200 µmol m−2 s−1.

Arabidopsis

Photosynthesis and Isoprene Emission

Whether Arabidopsis was grown under 200 or 100 μmol m−2 s−1 light, there was no significant difference in photosynthesis among EV-B3, B2, and C4 lines at either of the two time points analyzed (Supplemental Fig. S2). B2 had the highest isoprene emission rate, while no isoprene emission was detected from EV-B3 (Supplemental Fig. S2). Behnke et al. (2007) also reported that rates of photosynthesis were not different between isoprene-emitting gray poplar and gray poplar lacking isoprene emission due to RNAi-mediated suppression of ISPS.

Response of Photosynthesis and Isoprene Emission to Temperature, CO2, Light, Darkness, and N2 Break

Increasing temperature from 23°C to 30°C did not have a significant effect on photosynthesis in wild-type Arabidopsis or B2 (Fig. 5A). However, at temperatures above 30°C, photosynthesis declined gradually with increasing temperature. High temperature promoted isoprene emission in transgenic line B2. These data are consistent with data previously published (Possell and Hewitt, 2009, 2011; Vickers et al., 2009b; Niinemets and Sun, 2015). To our surprise, wild-type plants released isoprene at 35°C, at an emission rate of 0.1 nmol m−2 s−1, and the emission rate increased by 1.5- and 3.8-fold, respectively, at 40°C and 45°C (Fig. 5A). This emission was also observed in NE tobacco and may result from nonenzymatic conversion of DMADP to isoprene (Brüggemann and Schnitzler, 2002; Ghirardo et al., 2010).

Figure 5.

Photosynthesis and isoprene emission under varying environmental conditions in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS. The responses of photosynthesis (Photo) and isoprene emission to temperature (A), CO2 (B), light (C), darkness (D), and N2 break (E) in 39- to 42-d-old Arabidopsis empty vector control (EV-B3) and lines expressing ISPS (B2 and C4) are shown. In A, the wild type (WT) was used as the control. Data from B2 are shown in D and E. All plants were grown in growth chambers under a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1. Measurements were taken 30°C (B–E) and 500 μmol m−2 s-1 light intensity (A, B, and E). In D, plants were exposed to 500 μmol m−2 s−1 light before being exposed to sudden darkness. Values in A to C represent means ± se; values in D represent means (n = 5). In E, representative data from a single leaf are presented.

Control line EV-B3 and transgenic line B2 showed similar photosynthesis responses to CO2 whether they were grown at a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 5B) or 100 μmol m−2 s−1 (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Photosynthesis in EV-B3 and B2 increased with rising CO2 concentration, and there was no obvious difference between the two lines (Fig. 5B). Isoprene emission from B2 increased gradually as CO2 concentration was increased from 0 to 250 μmol mol−1, and then remained stable up to 500 μmol mol−1 CO2. Above 500 μmol mol−1, the rate of isoprene emission declined. There was no isoprene emission from EV-B3.

When EV-B3 and B2 plants grown under a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 were subjected to varying light intensities, photosynthetic rates were highest at 500 μmol m−2 s−1 and remained nearly stable at intensities above 500 μmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 5C). The response of isoprene emission from B2 to light was similar to that of photosynthesis when the light intensity was below 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1; above that a slight decline occurred. No isoprene was released from EV-B3. Similar responses were also found in EV-B3 and B2 grown at 100 μmol m−2 s−1 (Supplemental Fig. S3B).

B2 grown at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 5D) and 100 μmol m−2 s−1 (Supplemental Fig. S3C) showed a rapid decline in isoprene in response to sudden darkness. This has been observed in previous studies in oak and eastern cottonwood (Sharkey and Loreto, 1993; Li et al., 2011). However, unlike in oak and poplar, no postillumination peak was detected in Arabidopsis plants (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Fig. S3C).

Under illumination, when B2 was exposed to pure N2, isoprene emission declined to low levels (Fig. 5E). When it was exposed to air again after 17 min in pure N2, isoprene emission rapidly increased and reached a maximum about 10 min after restoring oxygen and CO2, with an increase of 91% compared with the isoprene emission rate before exposure to N2. This behavior has also been reported for aspen (Populus tremula × Populus alba) by Li and Sharkey (2013a), who hypothesized that it is caused by accumulation of methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcDP) during the N2 exposure.

MEP Pathway Metabolomics

There were no significant differences between Arabidopsis EV-B3, B2, and C4 in the levels of MEP pathway metabolites in plants grown under a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 6A). MEcDP levels were lower and MEP levels were higher in Arabidopsis than in tobacco (Fig. 6). Because of compounds interfering with the mass spectrometer measurement of DMADP/isopentenyl diphosphate (IDP), we assessed DMADP/IDP by integrating the postillumination isoprene emission (Rasulov et al., 2009; Weise et al., 2013). This technique can only be used with emitting plants, so there are no data available for DMADP in nonemitting lines. The concentration of DMADP/IDP was low (note the extremely fast decline in isoprene emission upon darkening in Fig. 5D) relative to the values found in aspen, which were around 800 nmol m−2 s−1 (Li and Sharkey, 2013a). The low MEcDP content of Arabidopsis leaves is consistent with the lack of the postillumination emission described above (Fig. 5D). For a comparison of metabolite levels in Arabidopsis and tobacco, the data in Figure 6 are plotted together in Supplemental Figure S4.

Figure 6.

MEP pathway metabolites in Arabidopsis and tobacco expressing ISPS. Metabolite levels in leaves harvested from 42-d-old Arabidopsis empty vector control (EV-B3) and lines expressing ISPS (B2 and C4; A), and 42-d-old NE and IE tobacco (B), are shown. Arabidopsis plants were grown in a growth chamber under a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1. Tobacco was grown in the greenhouse. CDP-ME, Diphosphocytidylyl methylerythritol; DXP, deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate; HMBDP, hydroxymethylbutenyl diphosphate. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the three Arabidopsis lines or between NE and IE at P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test (i.e. there were no differences). Values represent means ± se. For Arabidopsis, n ≥ 5 plants per line; for tobacco, n = 7. Because DMADP + IDP were measured by postillumination isoprene emission, there are no data for Arabidopsis EV-B3 and tobacco NE lines.

Alterations in Plant Growth in Isoprene-Emitting Arabidopsis Lines

Arabidopsis lines B2 and C4 expressing ISPS produced larger cotyledons and longer hypocotyls than the empty vector control line EV-B3 (Supplemental Fig. S5), as had been seen in the preliminary screen (Fig. 2). This experiment showed that the effect was not dependent on light intensity.

While whole rosette growth was the main focus during characterization of the seven Arabidopsis lines expressing ISPS, here we explored in more detail leaf characteristics and growth of the two highest emitting lines. Compared with EV-B3, projected leaf area was consistently larger in B2 and C4 (Fig. 7, A–C). In addition, B2 and C4 also produced longer leaves and a greater number of leaves than EV-B3 (Table 1; Fig. 7, D–F; Supplemental Table S1), regardless of the light level the plants were grown in. Overall, the total leaf area was larger in B2 and C4 than in the control at both 28 and 35 DAS in plants grown under 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (Table 1; Fig. 7, D–F). Similar results were obtained from plants grown under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 (Supplemental Table S1). In fact, at maturity (50 DAS), the total leaf area was greater in most of the isoprene-emitting lines than in the four control lines (Fig. 7G).

Figure 7.

Leaf growth in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS. A comparison of rosette size reflecting projected leaf area (A–C) and leaves after being separated from the rosettes reflecting apparent total leaf area (D–F) in 35-d-old Arabidopsis empty vector control (EV-B3) and lines expressing ISPS (B2 and C4) are shown. For A to F, all plants were grown in growth chambers under a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1. G shows a comparison of total leaf area of all lines used in this study. Plants used in G were 50 d old and grown at 120 μmol m−2 s−1. In G, Arabidopsis lines expressing ISPS that are significantly different from Col-0 and empty vector lines EV-A2 and EV-B3 are marked with asterisks: *, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test.

Table 1. Plant growth in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS.

Leaf area, leaf curling, dry weights of leaf, stem, and aboveground plant organs, LMA, length of leaf, number of leaves, and inflorescence stem height were measured in 28- and 35-d-old Arabidopsis empty vector control (EV-B3) and lines expressing ISPS (B2 and C4). All plants were grown in growth chambers under a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1. Nd, Not determined. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between the three lines at P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test. Values represent means ± se (n = 5 plants per line).

| Age | Plant Line | Leaf Area (cm2) | Curling | Weight (mg) | LMA (g/m2) | Leaf Length (cm) | Leaf No. | Inflorescence Stem Height | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | Stem | Aboveground | ||||||||

| Day 28 | EV-B3 | 46.0 ± 4.2 b | Nd | 89 ± 4 b | Nd | Nd | 19.7 ± 1.0 a | 4.88 ± 0.16 b | 27.4 ± 1.3 a | Nd |

| B2 | 57.1 ± 4.3 a,b | Nd | 129 ± 5 a | Nd | Nd | 23.1 ± 1.7 a | 5.41 ± 0.21 a,b | 28.2 ± 0.9 a | Nd | |

| C4 | 60.1 ± 2.6 a | Nd | 129 ± 4 a | Nd | Nd | 21.7 ± 1.3 a | 5.48 ± 0.11 a | 29.6 ± 1.1 a | Nd | |

| Day 35 | EV-B3 | 104 ± 5 b | 14.7 ± 1.5 a | 262 ± 1.6 b | 7 ± 0.0 b | 269 ± 16 b | 25.2 ± 0.5 a | 6.05 ± 0.13 b | 31.4 ± 1.7 b | 0.86 ± 0.07 b |

| B2 | 126 ± 3 a | 12.3 ± 1.3 a | 335 ± 6 a | 10 ± 1 a,b | 345 ± 7 a | 26.5 ± 0.5 a | 6.61 ± 0.07 a | 37.2 ± 1.6 a | 1.54 ± 0.21 a | |

| C4 | 118 ± 4 a | 10.1 ± 1.8 a | 319 ± 6 a | 15 ± 2 a | 334 ± 13 a | 27.0 ± 0.5 a | 6.46 ± 0.09 a | 38.0 ± 1.9 a | 1.68 ± 0.15 a | |

Regardless of the growth light intensity, leaf, inflorescence stem, and total aboveground dry weight in B2 and C4 was greater than in EV-B3 (Table 1; Supplemental Table S1). However, there was no significant difference in the leaf mass per unit leaf area (LMA; Table 1; Supplemental Table S1).

In 35-d-old B2 and C4 lines grown under a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1, leaves curled less compared with those of EV-B3, although the difference was not statistically significant (Table 1; Fig. 7). However, a significant difference in the degree of leaf curling was found between emitting and nonemitting lines when these plants were grown under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 light (Supplemental Table S1).

Isoprene-emitting lines B2 and C4 also showed early inflorescence initiation when grown under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 (Supplemental Table S1). The height of the primary inflorescence axis or inflorescence stem was also significantly longer in B2 and C4 than in EV-B3 (Table 1).

Plant Pigment Content in Arabidopsis Expressing ISPS

While lines B2 and C4 with the highest isoprene emission rates always produced the highest leaf pigment concentrations, other isoprene-emitting lines also produced higher pigment concentrations relative to the controls (Fig. 8). The chlorophyll (Chl) a/b ratio was unchanged in isoprene-emitting lines. Enhanced Chl and carotenoid levels in B2 and C4 were also seen despite growth light conditions.

Figure 8.

Comparison of photosynthetic pigment concentrations in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS. Concentrations of Chl a (A), Chl b (B), and total Chl (C), Chl a/b ratio, and carotenoid concentration (E) in leaves harvested from 49-d-old Arabidopsis wild-type Col-0, empty vector controls (EV-A2, EV-B3, and EV-F1), and lines expressing ISPS (A1, F2, C1, C4, and B2) are shown. All transgenic lines belonged to the T2 generation. Values represent means ± se (n = 4 or 5 plants per line). Arabidopsis lines expressing ISPS that are significantly different from Col-0 and empty vector lines EV-A2 and EV-B3 are marked with symbols: +, P < 0.1 and *, P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test.

Tobacco

Plants grown from seeds of a nonemitting, azygous control (NE) and an emitting line (IE) of tobacco corresponding to line 32 originally described by Vickers et al. (2009b) were studied for comparison with the Arabidopsis model system generated by us.

Photosynthesis and Isoprene Emission

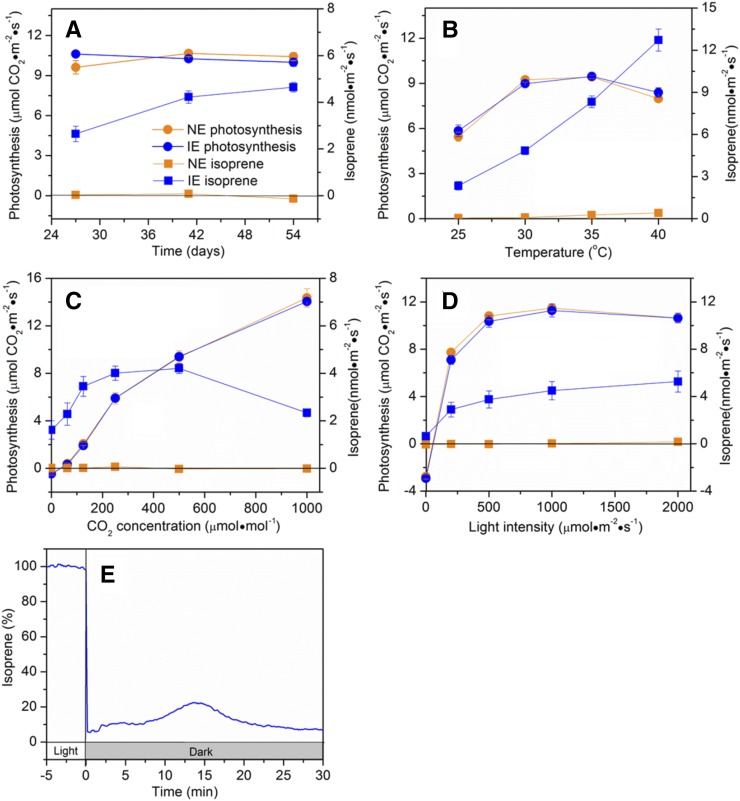

The isoprene emission status of the tobacco lines was confirmed. The photosynthetic rate in NE and IE tobacco was stable from day 27 to day 54, and no significant difference was found between the two lines (Fig. 9A). Isoprene was not released from NE lines, while its emission rate increased during growth of the transformed line, with increases of 60% and 75% on day 41 and day 54, respectively, compared with day 27 (Fig. 9A). A modest but significant improvement in thermotolerance was observed (Supplemental Fig. S6). To compare with that seen in Arabidopsis, we also reconfirmed the responses of isoprene to temperature and light studied in tobacco by Vickers et al. (2009b) and examined isoprene responses to CO2 and exposure to sudden darkness.

Figure 9.

Comparison of photosynthesis and isoprene emission under varying environmental conditions in NE and IE tobacco. Photosynthesis and isoprene emission measured simultaneously in 27-, 41-, and 54-d-old NE and IE tobacco (A), and responses of photosynthesis and isoprene emission to temperature (B), CO2 (C), light (D), and darkness (E) in 43- to 47-d-old NE and IE tobacco, are shown. Measurements were taken at 30°C (A and C–E) and 800 μmol m−2 s-1 light intensity (A–C). In E, plants were under 800 μmol m−2 s-1 light before being exposed to sudden darkness. Values in A to D represent means ± se; values in E represent means (n = 5).

Response of Photosynthesis and Isoprene Emission to Temperature, CO2, Light, and Darkness

Photosynthesis in NE and IE lines increased with increasing temperature up to 35°C and then declined above that temperature (Fig. 9B), but there was no substantial difference between the two lines. Isoprene emission rate from IE plants increased with increasing temperature, and NE plants began to release isoprene at high temperature at very low but easily measured rates. At 35°C, NE plants had an emission rate of 0.27 nmol m−2 s−1, which was further elevated with increasing temperature.

Photosynthesis rates increased with rising CO2 concentration both in NE and IE lines and did not differ between the two lines (Fig. 9C). Isoprene emission from IE plants increased with CO2 concentration from 0 to 250 μmol mol−1, remained stable between 250 and 500 μmol mol−1 CO2, then declined above 500 μmol mol−1. Isoprene emission was not detected in NE plants at any CO2 level.

Photosynthesis increased with light intensity in NE and IE plants (Fig. 9D). A weak decrease was found above 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1. However, there was no significant difference in photosynthesis rate between the two lines. Isoprene emission increased with increasing light intensity in IE, while no isoprene emission was seen in NE lines.

When IE leaves kept under a light intensity of 800 μmol m−2 s−1 were abruptly exposed to darkness, isoprene emission quickly declined by 94% (Fig. 9E). However, unlike Arabidopsis, an emission peak appeared after 13.7 min in darkness in tobacco (Figs. 5D and 9E), similar to that observed in oak and poplar (Li et al., 2011).

MEP Pathway Metabolomics

Tobacco leaves had lower levels of MEP and higher levels of MEcDP and HMBDP than Arabidopsis regardless of whether they were making isoprene or not (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Fig. S4). In tobacco, both MEcDP and HMBDP were higher than deoxyxylulose phosphate or MEP. The high level of MEcDP is consistent with the postillumination burst of isoprene described above (Fig. 9E). The high level of HMBDP was not seen in metabolomics of aspen (Li and Sharkey, 2013a).

Plant Growth

Vickers et al. (2009b) did not see a statistically significant difference in growth between mature NE and IE plants (see plant line 32 in supplementary data in Vickers et al., 2009b). We examined the growth of these lines under normal (unstressed) growth conditions in both young seedlings and mature plants.

There was a significant difference in cotyledon area between NE and IE tobacco grown in soil, whether they were grown in the greenhouse or in growth chambers. In contrast to that seen in Arabidopsis, the cotyledon area of IE lines grown in the greenhouse and in growth chambers was reduced by 34% and 24%, respectively, compared with that in NE (Fig. 10A). This difference was also found in tobacco grown in rock wool in the growth chamber (Fig. 10B). However, similar to Arabidopsis, IE seedling hypocotyls were taller than those of NE plants (Fig. 10C).

Figure 10.

Comparison of cotyledon and hypocotyl growth in NE and IE young tobacco seedlings. Cotyledon areas of NE and IE young tobacco seedlings grown in Suremix either in the greenhouse or in the growth chamber (under a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1) at 12 DAS (A), and representative photographs of cotyledons (B) and hypocotyls (C) of tobacco grown hydroponically in rock wool in 2-mL tubes in a chamber with a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 at 10 DAS, are shown. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between NE and IE at P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test. Values in A represent means ± se (n ≥ 12 plants per line).

Leaf area in 27-, 41-, and 54-d-old IE lines was smaller than that in NE lines (Table 2; Fig. 11, A–E). Stem height of the IE lines was also significantly shorter than NE lines (Table 2; Fig. 11, A, C, and F). Consistently, the weight of leaf, stem, and aboveground parts in IE plants was also less (Table 2). Opposite trends were seen in Arabidopsis (Table 1; Figs. 3, 4, and 7). The decrease in leaf area and leaf mass in IE agrees with data obtained by Vickers et al. (2009b). In general, LMA was greater in IE leaves than in NE leaves (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of plant growth in NE and IE tobacco.

Leaf area, dry weights of leaf, stem, and aboveground plant organs, LMA, and plant stem height were measured in 27-, 41-, and 54-d-old tobacco plants. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between NE and IE at P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test. Values represent means ± se (n = 5 plants per line).

| Age | Plant Line | Leaf Area (cm2) | Weight (g) | LMA (g⋅m−2) | Stem Height (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | Stem | Aboveground | |||||

| Day 27 | NE | 56.4 ± 1.9 a | 0.069 ± 0.004 a | 0.009 ± 0.001 a | 0.078 ± 0.004 a | 12.2 ± 0.3 b | 3.3 ± 0.2 a |

| IE | 43.4 ± 2.2 b | 0.058 ± 0.003 b | 0.006 ± 0.001 b | 0.064 ± 0.004 b | 13.5 ± 0.4 a | 2.3 ± 0.1 b | |

| Day 41 | NE | 532 ± 16 a | 0.80 ± 0.05 a | 0.32 ± 0.02 a | 1.13 ± 0.07 a | 15.1 ± 0.5 a | 24.9 ± 0.8 a |

| IE | 314 ± 18 b | 0.51 ± 0.02 b | 0.21 ± 0.01 b | 0.71 ± 0.03 b | 16.2 ± 0.4 a | 19.8 ± 0.6 b | |

| Day 54 | NE | 2,320 ± 61 a | 3.75 ± 0.06 a | 2.39 ± 0.06 a | 6.16 ± 0.11 a | 16.2 ± 0.3 a | 61.0 ± 2.0 a |

| IE | 1,531 ± 51 b | 2.42 ± 0.09 b | 1.49 ± 0.22 b | 3.91 ± 0.30 b | 15.8 ± 0.3 a | 46.7 ± 0.7 b | |

Figure 11.

Comparison of leaf and plant growth over time in NE and IE tobacco. Photographs depict the front and top views of tobacco plants taken at day 27 (A and B), day 41 (C and D), and day 54 (E and F) of plant growth. In G, the shape of leaf tips of the sixth mature leaf is compared.

Interestingly, the shape of the leaf tip in leaves appearing after the sixth leaf differed between IE and NE lines. The sixth leaf produced by NE lines still had a sharp, pointed leaf tip, while in IE it was notched (Fig. 11G).

Differences in Pigment Content

Tobacco IE leaves had more Chl a, Chl b, and carotenoids than NE leaves (Table 3). However, the Chl a/b ratio was not different between the two lines. Vickers et al. (2009b) did not see a difference in pigment levels measured in µg g−1 fresh weight between NE and IE. For comparison, we also estimated pigment content in mg g−1 dry weight, taking into account differences in LMA ( Table 3). The increase in pigment concentration in IE lines was still evident even when expressed in mg g−1 leaf dry weight, which shows that observed differences in pigment content between NE and IE when measured based on leaf area are not a result of variations in LMA.

Table 3. Pigment content in NE and IE tobacco.

The Chl a, Chl b, and carotenoid (Car) pigment contents obtained from mature leaves harvested from 27-, 41-, and 54-d-old tobacco plants are shown. Raw data for LMA (g m−2 leaf area) and pigment content (μg m−2 leaf area) were used to estimate pigment content (mg g−1 leaf dry weight). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between NE and IE at P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s lsd test. Values represent means ± se (n = 5 plants per line).

| Age | Plant Line | Pigment Content (μg⋅m−2) | Pigment Content (mg⋅g−1 DW) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chl a | Chl b | Car | Chl a | Chl b | Car | ||

| Day 27 | NE | 12.3 ± 0.2 b | 4.1 ± 0.1 a | 2.6 ± 0.1 b | 10.06 ± 0.19 a | 3.36 ± 0.07 a | 2.16 ± 0.04 a |

| IE | 13.4 ± 0.3 a | 4.4 ± 0.1 a | 2.9 ± 0.1 a | 9.97 ± 0.22 a | 3.26 ± 0.06 a | 2.19 ± 0.04 a | |

| Day 41 | NE | 17.7 ± 0.4 b | 5.6 ± 0.1 b | 3.7 ± 0.1 a | 11.75 ± 0.28 b | 3.70 ± 0.07 b | 2.46 ± 0.07 a |

| IE | 19.8 ± 0.5 a | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 4.0 ± 0.1 a | 12.31 ± 0.32 a | 4.06 ± 0.08 a | 2.49 ± 0.07 a | |

| Day 54 | NE | 19.5 ± 0.4 b | 6.8 ± 0.1 b | 3.8 ± 0.1 a | 12.04 ± 0.25 b | 4.18 ± 0.07 b | 2.37 ± 0.06 b |

| IE | 21.7 ± 0.7 a | 7.4 ± 0.2 a | 4.1 ± 0.2 a | 13.79 ± 0.45 a | 4.72 ± 0.14 a | 2.59 ± 0.10 a | |

Effects of Isoprene on Gene Expression in Arabidopsis and Tobacco

In Arabidopsis expressing ISPS (line B2), 551 genes were differentially expressed when compared with expression in the empty vector line EVB3. Of these, 292 had higher expression and 259 had lower expression at α = 0.1 (at α = 0.05, 108 genes were up-regulated and 87 were down-regulated; Supplemental File S1). In tobacco expressing ISPS (IE), 3,779 genes were differentially expressed, out of which 1,732 were up-regulated and 2,067 were down-regulated at α = 0.1 (at α = 0.05, 1,321 genes were up-regulated and 1,345 were down-regulated; Supplemental File S2). We compared differentially expressed genes in the above two systems and those found in Arabidopsis fumigated with isoprene (Harvey and Sharkey, 2016) to identify isoprene-responsive genes common to at least two or all three systems. These data are summarized in Supplemental Tables S2 to S5. Although only one isoprene-emitting line was used for Arabidopsis (B2) and tobacco (IE), we believe that selecting differentially expressed genes common to more than one system facilitated the selection of genes reflective of the isoprene treatment regardless of both interspecies variation and position-of-integration effects. Although altered in expression in all three systems, uncharacterized genes were not included in Supplemental Tables S2 to S5. A list of descriptive gene names of all the genes mentioned in the following text is provided in the Supplemental Materials under the title "List of gene/domain names used in the paper".

Isoprene Alters Expression of Genes of Specific Growth Regulator Signaling Pathways

Transcriptomic analyses revealed that expression of key genes important for the synthesis of specific growth regulators, as well as key components of these growth regulator-signaling pathways, were altered in plants exposed to isoprene either internally (Arabidopsis and tobacco expressing ISPS) or externally (Arabidopsis fumigated with isoprene; Supplemental Table S2). Isoprene altered gene expression to support the enhancement of jasmonic acid (JA), cytokinin (CK), gibberellins (GA), and ethylene signaling. The altered genes affecting JA include BBD1, BBD2, LOX1, LOX3, LOX4, LOX5, OPR3, and MYB59. Genes affecting cytokinins include KFB20 and WIND1. Those affecting gibberellins include TZF5, MARD5, TEM1, and DFL2. Genes related to ethylene include EBF1, EBF2, and ACO4. Changes in transcription of key genes in brassinosteroid (BR; BRI1), auxin (MYB73, BPC, and KFB20), and salicylic acid, (SA; CBP60A, ATAF1, EBF1, and EBF2) signaling provided evidence for the down-regulation of these pathways in the presence of isoprene. Interestingly, expression of genes belonging to the abscisic acid (ABA) signaling branch required to achieve drought tolerance (NCED3, NCED5, and ATAF1) was enhanced in response to isoprene, while expression of genes involved in ABA signaling associated with seed dormancy (TZF5, MARD1, NCED4, and MYBS2), pathogen resistance (BBD1, BBD2, and MPK7), and heat (NCED4) and salt (CIPK20) stress appeared to be down-regulated (Supplemental Table S2).

Among the isoprene-responsive genes associated with the biosynthesis of specific growth regulators and their signaling were a number encoding MYB family transcription factors (MYB59, MYB73, and MYBS2), an AP2/ERF transcription factor (WIND1), a RAV1-like ethylene-responsive transcription factor (TEM1), a NAC transcription factor (ATAF1), a basic penta-Cys transcription factor (BPC4), and a calmodulin-binding transcription factor (CBP60A; Supplemental Table S2). Genes responsive to isoprene also encoded different types of proteins, such as F-box proteins (KFB20, EBF1, and EBF2), zinc finger proteins (TZF5 and MARD1), GH3-related proteins (DFL2), and nucleases (BBD1 and BBD2), oxygenases (LOX1, LOX3, LOX4, LOX5, NCED3, NCED4, and NCED5), oxidases (ACO4), reductases (OPR3), and different types of kinases, including Ser/Thr (CIPK20), mitogen-activated (MPK7), and Leu-rich repeat receptor (BRI1) kinases (Supplemental Table S2).

Isoprene Alters Expression of Genes That Lead to Abiotic Stress Tolerance

Even though we used unstressed plants for gene expression analyses, the expression of a number of genes in abiotic stress signaling pathways was altered in response to isoprene (Supplemental Table S3). Isoprene seemed to affect gene expression that leads to detoxification of heavy metals (MRP2, MRP4, MRP5, MRP8, MRP11, HIPP32, and MYB59), protection against xenobiotics and excess secondary metabolites (MRPs), and enhanced tolerance to soil acidity (NRT1.1), high/fluctuating/low light (MPH1, MPH2, NDHL, NDHN, and SAUL1), heat (NCED4, MRP5, NRT1.1, ADC1, ADC2, CuAO3, NDHL, NDHN, PTI1, COP1, PAL, and other genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway), salinity (MYB73, CIPK20, NCED3, ADC1, ADC2, and PIP5K2), drought (NCED3, NCED5, ATAF1, MRP4, CuAO3, and WIND1), and oxidative stress (NADK1, AXS2, CATHB3, ADC1, ADC2, and PTI1). Tolerance against heat and oxidative stress are well-known protective functions of isoprene in plants. In contrast, gene expression associated with freezing tolerance appeared to be reduced in the presence of isoprene (CRPK1 and LTP3).

Interestingly, isoprene-responsive genes involved in abiotic stress tolerance included many proteins involved in transport mechanisms: ABC transporters (MRP2, MRP4, MRP5, MRP8, and MRP11), metallochaperones (HIPP32), NO3− transporters (NRT1.1), and proteins associated with lipid transport (LPT3) and those that induce bulk-flow endocytosis (PIP5K2; Supplemental Table S3). Isoprene-responsive genes that promoted abiotic stress coded for proteins important for cation (Ca2+ and NO3−) signaling and homeostasis (MYB59, MRPs, and NRT1.1), membrane proteins (MRPs, MPH1, NRT1.1, CRPK1, NDHL, and NDHN), different types of kinases, including Ser/Thr (CIPK20 and PTI1), cold-responsive (CRPK1), phosphatidylinositol monophosphate 5-kinase2 (PIP5K2), and NAD(H) kinase (NADK1), transcription factors (WIND1, MYB59, ATAF1, and MYB73), and secondary metabolite synthesis and sequestration, such as glucosinolate sequestration (MRPs), polyamine biosynthesis (ADC1, ADC2, and CuAO3), phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and regulation (PAL1, PAL2, PAL4, CPK1, 4CLI1, 4CLI2, 4CLI3, CCOAMT, DHQ-SDH, and KFB20; Supplemental Tables S3 and S4), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate synthesis (PIP5K2), and apiose and apiin biosynthesis (AXS2; Supplemental Table S3). There were also E3 ubiquitin ligases (SAUL1), oxidases (CuAO3), decarboxylases (ADC1 and ADC2), proteases (CATHB3), synthases (AXS2), and oxygenases (NCED3, NCED4, and NCED5) associated with abiotic stress responses whose expression was altered by isoprene (Supplemental Table S3).

Functions of proteins encoded by ADC1, ADC2, CuAO3, NADK1, MPH1, MPH2, PAL1, PAL2, PAL4, CPK1, 4CLI1, 4CLI2, 4CLI3, CCOAMT, DHQ-SDH, and KFB20 include stabilization of thylakoid membranes under heat, salt, and oxidative stress, remedying of oxidative damage under a variety of stresses, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and ozone, prevention of photoinhibition, repair of PSII under high light, etc.

Isoprene Alters Expression of Genes That Enhance Resistance to Biotic Stress

Transcriptomic data also revealed that isoprene affects the expression of key genes that are components of signaling pathways related to biotic stress, such as herbivory and wounding, and infection by necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogens (Supplemental Table S4). Isoprene-responsive gene expression supported resistance against herbivory and wounding (LOX1, LOX3, LOX4, LOX5, OPR3, MRP2, MRP4, MRP5, MRP8, MRP12, ADC1, ADC2, MYB59, WIND1, PAL1, PAL2, PAL4, CPK1, 4CLI, CCOAMT, DHQ-SDH, KFB20, AXS2, and CYP81D8). Most of these genes belong to JA-mediated defense signaling, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and regulation, CK-mediated wound repair, as well as signaling mediated by oxylipin, glutathione, and apiose (Supplemental Table S4). Isoprene-mediated resistance against herbivory has been reported (Laothawornkitkul et al., 2008). Almost all enzymes of the phenylpropanoid pathway were up-regulated in Arabidopsis fumigated with isoprene (Harvey and Sharkey, 2016), and expression of PAL, 4CLI, CCOAMT, and DHQ-SDH was also up-regulated in tobacco expressing ISPS (Supplemental Table S4). In addition, expression of CPK1, which encodes a calcium-dependent protein kinase that phosphorylates and activates PAL (Cheng et al., 2001; Boudsocq and Sheen, 2013), was up-regulated in all three model systems tested; expression of KFB20, which encodes a protein that physically interacts with and targets PAL isozymes for degradation through ubiquitination (Zhang et al., 2013), was suppressed in both Arabidopsis expressing ISPS and Arabidopsis fumigated with isoprene. Expression of PAL, 4CLI, CCOAMT, and DHQ-SDH was significantly down-regulated in poplar subjected to RNAi-mediated suppression of ISPS under moderate heat stress (Behnke et al., 2010), supporting the hypothesis that the changes in gene expression observed in our study were mediated by isoprene. There were no statistically significant changes in the expression of phenylpropanoid pathway enzymes in Arabidopsis expressing ISPS.

Isoprene altered gene expression that can enhance resistance against biotrophic pathogens (MORC7, BRI1, PCRK1, PTI1, GH9C2, and BRI1; Supplemental Table S4). However, some isoprene-responsive genes appeared to reduce resistance against the biotrophic pathogens Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola strain ES4326 (CBP60A) and Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato strain DC3000 (ATAF1, EBF1, EBF2, and MPK7; Supplemental Table S4). Data indicated that isoprene-responsive genes that supported enhanced resistance to biotrophs belonged to signaling pathways independent of SA and ABA and that isoprene-mediated gene expression that supports the suppression of SA and ABA pathways increases the susceptibility of isoprene-emitting plants to biotrophs.

Isoprene suppressed the expression of the Leu-rich repeat receptor kinase BRI1 (Supplemental Table S4), the main BR receptor localized in the plasma membrane, which launches a signaling cascade with subsequent induction of BR-induced changes in gene expression (Lozano-Durán and Zipfel, 2015). Suppression of this BRI1 has been shown to enhance resistance against many necrotrophic pathogens, like Fusarium pseudo-graminearum, Fusarium culmorum, Pyrenophora teres, Gaeumannomyces graminis, Oculimacula spp., and Barley stripe mosaic virus (Lozano-Durán and Zipfel, 2015). However, alteration of the expression of some genes may lead to enhanced susceptibility to the necrotrophic pathogens Botrytis cinerea (BBD1, BBD2, and ATAF1) and Alternaria brassicicola (ATAF1; Supplemental Table S4). Thus, suppression of BRI1 and WAKL6 by isoprene supported resistance against many necrotrophic pathogens.

Isoprene-responsive genes that favored resistance to herbivory and wounding, as well as biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens, also included additional proteins such as calcium-dependent protein kinase (CPK1), MAPK (MPK7), cytochrome P450 SA-independent systemic acquired resistance gene (CYP81D8), and membrane proteins such as GHKL ATPase (MORC7), receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase (PCRK1), Leu-rich repeat receptor kinase (BRI1), and transmembrane protein with a cytoplasmic Ser/Thr kinase domain (WAKL6; Supplemental Table S4). Among the isoprene-responsive genes that enhance response to biotic stress were three genes that enhance the synthesis of structural carbohydrates: apiose (also a secondary metabolite; AX2), callose (WIND1, BBD1, BBD2, and PCRK1), and cellulose (G69C2).

Isoprene Alters Expression of Genes That Affect Photosynthesis, Seed Germination, and Seedling and Plant Growth

Expression of genes important for photosynthesis and plant growth was also significantly affected by isoprene (Supplemental Table S5). For example, expression of PRPS20 (Wu et al., 2007; Romani et al., 2012; Gong et al., 2013; Tiller and Bock, 2014) and RPL24 (Tiller et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014; Tiller and Bock, 2014), which lead to enhancement of chloroplast development and Chl production, was up-regulated in the presence of isoprene. CK can also promote Chl production and delay senescence (Supplemental Table S2). These gene expression data are in agreement with enhanced pigment concentrations in leaves of both Arabidopsis and tobacco emitting isoprene.

Genes encoding subunits of the NADH dehydrogenase-like complex (NDHL and NDHN) associated with PSI, which is involved in cyclic electron flow that protects PSII under abiotic stress, as well as thylakoid and stromal proteins important for protecting and stabilizing PSII under high light stress (MPH1 and MPH2), were also up-regulated by isoprene (Supplemental Table S5). Isoprene also altered gene expression in a manner that can lead to reduced chloroplast movement under blue light (WEB1) and increase polyamine biosynthesis and protection of photosynthetic components against a variety of stresses (ADC1, ADC2, and CuAO3), including heat, salt, and oxidative stress.

A number of genes that are crucial for early seedling establishment were altered by isoprene, which included genes essential for seed dormancy inhibition and enhanced seed germination (MYBS2, EBS, TZF5, NCED4, MARD1, ADC1, and ADC2), proper embryo development (PRPS20, RPL24, EMB2184, and MYBS2), seedling growth (PRPS20, RPL24, EMB2184, MYBS2, DFL2, and COP1), and elongation of hypocotyls (DFL2, TEM1, and COP1; Supplemental Table S5). Isoprene also altered gene expression in favor of enhanced leaf expansion and growth (TEM1, TZF5, AXS2, and PIP5K2), root growth (PIP5K2, MYB59, NRT1.1), and early flowering (TZF5, TEM1, COP1, ZFP8, EBS, WIND1, and AGP3). Growth-promoting genes included chloroplast ribosomal subunit genes (PRPS20, RPL24, and EMB2184), GA-signaling pathway genes (TZF5 TEM1, DFL2, and MARD1), interactors of phytochrome interacting factors or PIF (COP1), CK-signaling pathway genes (WIND1), cell cycle regulators (MYB59), transcription factors (ZFP8, MYBS2, MYB59, and EBS), apiose (AXS2) and polyamine synthesis genes (ADC1 and ADC2), and an auxin transport and phosphoinositide synthesis gene (PIP5K2). These data correspond well with the observed growth enhancement in seedlings and rosettes as well as the early-flowering phenotype seen in Arabidopsis isoprene-emitting lines. Interestingly, the growth-promoting genes were associated with GA and PIF signaling and were mostly differentially expressed in the two Arabidopsis model systems (Supplemental Table S5). Growth-promoting genes expressed in tobacco were PRPS20, RPL24, EMB218, COP1, ZFP8, MYBS2, EBS, AXS2, and PIP5K2. The reasons why tobacco showed reduced growth will be discussed later. A few genes were altered in a manner that can have a negative impact on growth (LTP3, PATL1, ZIM, BRI1, and BPC4). Isoprene also altered gene expression that can prevent (TEM1 and SAUL1) or enhance (ATAF1 and ADC7) senescence.

DISCUSSION

Genetically engineering nonemitting wild-type plant species (e.g. Arabidopsis and tobacco) to express ISPS (Sharkey et al., 2005; Loivamäki et al., 2007; Sasaki et al., 2007; Vickers et al., 2009b) and to suppress ISPS in plants known to be strong emitters (Behnke et al., 2007) has been a useful method to investigate the effects of isoprene on plant stress tolerance. In this study, we used Arabidopsis lines transformed to express ISPS to determine growth, photosynthesis, and isoprene emission in unstressed plants and to study how the regulation of isoprene emission takes place when ISPS is introduced to plants such as tobacco and Arabidopsis that do not normally have ISPS. We also investigated the role of isoprene as a signaling molecule and the key signaling pathways affected by isoprene. We saw that although Arabidopsis and tobacco do not normally produce isoprene, when engineered to do so, the same responses to temperature, CO2, and light can be observed as in native emitters. Hypocotyl elongation was promoted in isoprene-emitting Arabidopsis and tobacco. Isoprene promoted cotyledon and leaf expansion, length and number of leaves, growth rates, and leaf and whole-plant dry weights and resulted in early flowering and taller inflorescences in Arabidopsis; cotyledon and leaf growth was reduced in tobacco IE lines. Transformation with ISPS brought about significant increases in Chl and carotenoid contents in both Arabidopsis and tobacco. These phenotypes observed in the isoprene-emitting transgenic lines were a result of isoprene and not an effect of growth light or as a result of changes in the MEP pathway metabolites. The mechanisms through which isoprene may exert changes in plant growth, the role of isoprene as a signaling molecule, and the significance of our findings are discussed in the following sections.

The DMADP Pools in Nonemitting Plants Is Sufficient to Sustain Isoprene Synthesis under Different Environmental Conditions

Examination of the patterns of isoprene emission under normal conditions as well as under different levels of temperature, CO2, and light revealed that the chloroplastic DMADP pools in both tobacco and Arabidopsis are sufficient to maintain isoprene production under different environmental conditions. Tobacco had a higher level of MEcDP, similar to levels seen in aspen (Li and Sharkey, 2013a). Arabidopsis had relatively more MEP. DMADP synthesis from MEcDP is highly dependent on reducing power (Banerjee and Sharkey, 2014). Conversion of MEP to MEcDP is dependent on ATP (Banerjee and Sharkey, 2014). Higher levels of MEP in Arabidopsis compared with tobacco, and higher levels of MEcDP in tobacco compared with Arabidopsis, indicate that Arabidopsis may be more limited by ATP while tobacco may be more limited by reducing power. The fact that MEP pathway metabolites were not altered suggests that the alteration in phenotypes observed in the isoprene-emitting transgenic lines is in fact a result of isoprene and not a result of changes in the MEP pathway metabolites, such as MEcDP, which can act as a retrograde signal (Xiao et al., 2012). As only one representative tobacco line was used for the biochemical analysis above, the use of more transgenic lines is necessary to further confirm the above comparisons.

Although the DMADP pools in Arabidopsis were lower than those in tobacco (this study) and aspen (Li and Sharkey, 2013a), the emission rates were slightly higher than those reported previously in transformed Arabidopsis (Sharkey et al., 2005; Loivamäki et al., 2007). For example, isoprene emission rates in Arabidopsis transformed with an ISPS from gray poplar showed uppers limit of about 2.5 nmol m−2 s−1 at 30°C and 3 nmol m−2 s−1 at 40°C (see Figure 7I in Loivamäki et al., 2007). In Arabidopsis transformed with an ISPS from kudzu, an isoprene emission rate of 1.32 nmol m−2 s−1 was detected at 30°C (see Figure 10 in Sharkey et al., 2005). In this study, the emission rate was greater than 6 nmol m−2 s−1 at 40°C in B2 (Fig. 5A).

While DMADP limitation may play a role in restricting isoprene emission in Arabidopsis compared with that in tobacco (this study) and other species such as aspen, poplar, etc., the difference in isoprene emission rates between our study and Loivamäki et al. (2007) and Sharkey et al. (2005) may be due to the different promoters used to express ISPS and/or differences between kinetic properties of the ISPS. A constitutive Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter with gray poplar ISPS was used by Loivamäki et al. (2007) and a promoter from kudzu with a kudzu ISPS coding sequence was used by Sharkey et al. (2005) to transform Arabidopsis. In contrast, we used an rbcS-1A promoter to express an ISPS gene from E. globulus. It is known that rbcS-1A drives high rates of gene expression (Izumi et al., 2012). The Km values of ISPS for DMADP reported for gray poplar and kudzu are 2.4 mm (Schnitzler et al., 2005) and 7.7 mm (Sharkey et al., 2005), respectively. In contrast, the Km of E. globulus ISPS is much lower, around 0.03 mm (Sharkey et al., 2013). Thus, we hypothesize that the comparatively higher rates of isoprene emission observed in Arabidopsis during this study may be the result of the chloroplast-specific rbcS-1A promoter and the higher affinity E. globulus ISPS for DMADP.

The Regulation of Isoprene Emission Is Similar in Genetically Engineered and Natural Isoprene-Emitting Species

The regulatory mechanisms of photosynthesis and isoprene emission in Arabidopsis and tobacco lines genetically engineered to express ISPS functioned in a manner similar to that in native emitters, as evident by the responses to temperature, CO2, light, darkness, and N2. In addition, isoprene synthesis in these plants did not have a significant effect on photosynthesis under nonstressed conditions or under varying temperature, CO2, or light levels. While photosynthesis is the principal source of C and energetic cofactors (ATP, NADPH, and ferredoxin) for the MEP pathway (Sharkey et al., 2008; Banerjee and Sharkey, 2014), the rate of isoprene emission responds to higher temperature, CO2, and light differently than does the rate of photosynthesis (Li et al., 2011; Li and Sharkey, 2013b; Sun et al., 2013a; Way et al., 2013; Potosnak et al., 2014). Similarly, during our study isoprene and photosynthesis showed very different temperature responses and even some differences in light response.

It has been found that the effects of temperature on isoprene emission are complex because it affects both ISPS activity and substrate DMADP levels (Wiberley et al., 2008; Rasulov et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011; Vickers et al., 2011). As temperature gradually increases to about 35°C, isoprene emission increases because both the activities of ISPS and DMADP pools increase. Above this temperature, the DMADP pool begins to decline but ISPS activity still increases even at 40°C to 45°C, resulting in an increase in isoprene emission (Rasulov et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011; Li and Sharkey, 2013b; Sharkey and Monson, 2014). The optimum temperature of isoprene emission is usually between 40°C and 48°C (Singsaas and Sharkey, 1998; Niinemets et al., 1999; Singsaas et al., 1999; Rasulov et al., 2010).

Interestingly, a weak isoprene emission was found in Arabidopsis empty vector lines and tobacco NE at 35°C. This was also seen in nonemitting poplar (Behnke et al., 2013) and is assumed to be due to nonenzymatic conversion of DMADP to isoprene in the leaf (Brüggemann and Schnitzler, 2002; Ghirardo et al., 2010). The trivial amounts of isoprene measured in EV-F1 (30°C) and EV-B3 and NE at temperatures above 35°C are likely not due to bacteria in the soil, because nonenzymatic isoprene production in bacteria occurs only when grown on specific growth media (Kuzma et al., 1995; Wagner et al., 2000), and in the case of NE (and poplar), only the leaf was in the leaf chamber during isoprene measurements. In addition, even though the presence of isoprene-degrading bacteria on leaf surfaces has been reported (Crombie et al., 2018), the presence of isoprene-emitting bacteria on the leaf phyllosphere and their contribution to nonenzymatic isoprene production are not known.

Elevated [CO2] has different effects on isoprene emission: no or moderate effects in P. alba (Loreto and Velikova, 2001; Loreto et al., 2007), Populus tremuloides (Calfapietra et al., 2008), and Populus × euramericana (Centritto et al., 2004) as well as promoting effects in Gingko biloba (Li et al., 2009) and P. tremula × P. tremuloides (Sun et al., 2012). Elevated [CO2] inhibited isoprene emission in Phragmites australis (Scholefield et al., 2004), Liquidambar styraciflua (Monson et al., 2007; Wilkinson et al., 2009), Platanus orientalis (Velikova et al., 2009), Acacia nigrescens (Possell and Hewitt, 2011), and E. globulus, P. tremuloides, and P. deltoides (Wilkinson et al., 2009). Both Arabidopsis and tobacco exhibited a high CO2 suppression of isoprene emission in this study. This decrease has been shown to result from the reduction of DMADP pools under elevated [CO2] (Possell and Hewitt, 2011; Sun et al., 2012).

While we only used one Arabidopsis (B2) and one tobacco isoprene-emitting line to test how isoprene emission varies under different environmental conditions, the temperature and light response curves were consistent with those published before for tobacco (Vickers et al., 2009b). In addition, although not performed in this study, measurements of ISPS activity and DMADP pool sizes under varying environmental conditions would further greatly clarify how isoprene formation is regulated in Arabidopsis and tobacco transgenic lines.

The Postillumination Burst May Be Species Specific Owing to Differences in MEcDP Pool Sizes

When a plant exposed to light is transferred to darkness, a discrete peak of emission of isoprene is detected after about 10 min in darkness. This is called the postillumination burst (Monson et al., 1991; Rasulov et al., 2010, 2011; Li et al., 2011) and is representative of the pool size of plastidic MEcDP (Li and Sharkey, 2013b). The reasons for the postillumination burst have been characterized as follows. Initially, isoprene emission following the imposition of darkness results from the consumption of DMADP plus IDP pools (Rasulov et al., 2009; Li et al., 2011; Li and Sharkey, 2013a, 2013b). In the MEP pathway, the conversion of MEcDP to HMBDP by HMBDP synthase is dependent on photosynthetic light reactions for reducing power (Seemann et al., 2002, 2006; Okada and Hase, 2005; Seemann and Rohmer, 2007; Li and Sharkey, 2013a, 2013b). However, with time the conversion of MEcDP to HMBDP and then to DMADP and IDP resumes, either because reducing power is supplied by an alternative source, possibly the pentose phosphate pathway, or because HMBDP synthase changes from requiring ferredoxin to accepting NADPH (Seemann et al., 2006), leading to isoprene emission in the dark (Li and Sharkey, 2013a, 2013b).

Arabidopsis had a small pool of MEcDP and no postillumination burst, while tobacco had a high level of MEcDP and showed a significant postillumination burst. Holding Arabidopsis leaves in N2 did allow for an overshoot in isoprene emission, likely the result of the accumulation of MEcDP in the N2 atmosphere. Thus, although we only used one representative isoprene-emitting Arabidopsis (B2) and tobacco line for the above experiments, the responses were similar to those reported previously.

In summary, our data show that regulation of isoprene emission in tobacco and Arabidopsis transformed with ISPS is similar to that in native isoprene emitters. Therefore, these responses are likely related to inherent regulatory mechanisms of the MEP pathway rather than reflecting regulation specific to isoprene.

Isoprene Has a Positive Effect on Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Production

Besides isoprene, the chloroplastic DMADP pool is used to synthesize myriad other volatile terpenoids, secondary products, and growth regulators. Geranyl diphosphate (GDP) synthesized from DMADP and IDP is the precursor for monoterpenes (Rohmer et al., 1993). Geranyl geranyl diphosphate synthesized from GDP is used to synthesize the phytol tail of Chl, phytoalexins, phylloquinones, plastoquinones, carotenoids, and tocopherols (Laule et al., 2003; Hwang and Sakakibara, 2006; Lichtenthaler, 2007, 2009; Kim et al., 2013). Carotenoids act as precursors for ABA and strigolactone biosynthesis (Beltran and Stange, 2016). Geranylgeranyl diphosphate also acts as a precursor for GA biosynthesis (Sun, 2008). Cytokinins can be made from HMBDP of the MEP pathway, although they are also made in the cytosol from DMADP from the mevalonic acid pathway (Kakimoto, 2003), which should not interact with isoprene synthesis.

The intuitive assumption would be that the production of Chl and carotenoids would decrease when chloroplastic DMADP is diverted to isoprene production when ISPS is introduced to nonemitting plants. But this was not the case both in Arabidopsis and tobacco. We saw a positive relationship between isoprene emission and Chl a, Chl b, and carotenoid content in Arabidopsis, which indicates that isoprene production favors Chl and carotenoid production in a dosage-dependent manner. In contrast to Vickers et al. (2009b), where a change was not observed, leaf pigment levels were also enhanced in tobacco IE lines during this study. Vickers et al. (2009b) expressed pigment concentration in µg g−1 fresh weight, and it is possible that variations in leaf fresh weight obscured the small differences in pigment concentrations between IE and NE lines evident in other studies. For example, a substantial positive correlation between isoprene emission and Chl, carotenoids, and xanthophyll cycle pigment synthesis (measured in µmol m−2) was found in basket willow (Salix viminalis; Harris et al., 2016). Behnke et al. (2007) saw reduced Chl and carotenoid contents (measured in nmol mg−1 dry weight) when isoprene emission was reduced in gray poplar by RNAi-mediated suppression of ISPS. However, in another study, when measured in µmol g−1 fresh weight, a difference in pigment concentration was not observed between isoprene-emitting gray poplar and RNAi lines (Behnke et al., 2010). Similarly, there was no difference (but no decline) in photosynthetic pigment concentrations (measured in mg g−1 fresh weight) in controls and Arabidopsis expressing ISPS from gray poplar (Loivamäki et al., 2007). The above examples show that the differences in pigment concentrations between isoprene-emitting and nonemitting lines are usually not seen when expressed on a fresh weight basis.

The fact that isoprene production does not negatively affect pigment production in transgenic lines may be because the MEP pathway is controlled primarily by feedback (Banerjee and Sharkey, 2014) and because GDP synthase that forms GDP from DMADP and IDP has a much higher affinity for DMADP than ISPS (Tholl et al., 2001; Laule et al., 2003; Orlova et al., 2009; Wang and Dixon, 2009; Rasulov et al., 2014).

The increase in Chl and carotenoid biosynthesis may be as a result of increased expression of genes associated with pigment biosynthesis by isoprene. For example, expression of the plastid ribosomal proteins PRPS20 and RPL24 was increased in both Arabidopsis and tobacco model systems during this study. These have been shown to enhance the expression of important Chl biosynthesis genes, including HEMA1, CAO1, YGL1, and PORAl, to increase rRNA processing in chloroplasts, and to promote chloroplast development (Wu et al., 2007; Romani et al., 2012; Tiller et al., 2012; Gong et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014; Tiller and Bock, 2014). In addition, isoprene-responsive gene expression favored enhanced CK signaling (KFB20), reduction of premature senescing (SAUL1 and TEM1), and polyamine biosynthesis genes in favor of spermidine and spermine synthesis (ADC1, ADC2, and CuAO3), all of which can promote Chl biosynthesis and retention (Capell et al., 2004; Mason et al., 2005; Raab et al., 2009; Woo et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2015; Groß et al., 2017).

In summary, our study along with data from previous studies provide strong evidence that the enhancement in photosynthetic pigment content in Arabidopsis and tobacco expressing ISPS is indeed due to isoprene and its effects on gene expression that promotes Chl and carotenoid biosynthesis.

Isoprene Affects Plant Growth and Development and Growth-Defense Tradeoffs

Isoprene caused significant effects on growth in both Arabidopsis and tobacco grown under unstressed conditions. The differences in growth between the isoprene-emitting plants and nonemitting plants in Arabidopsis and tobacco could be detected soon after germination. Both Arabidopsis and tobacco lines expressing ISPS produced seedlings with taller hypocotyls than the control lines, and cotyledons were larger in Arabidopsis and smaller in tobacco. We showed that these changes were not due to differences in growth conditions such as light level and growth media. This study found that isoprene affected the expression of a number of genes that promote embryo growth, seed germination, and seedling establishment, such as PRPS20, RPL24, EMB2184, MYBS2, EBS, NCED4, and COP1 (Gómez-Mena et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2007; Bryant et al., 2011; Muralla et al., 2011; Romani et al., 2012; Tiller et al., 2012; Bogamuwa and Jang, 2013, 2016; Gong et al., 2013; Huo et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014; Tiller and Bock, 2014; Chen et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018), in both Arabidopsis and tobacco, which may have contributed to hypocotyl elongation.

Two genes that specifically reduce hypocotyl elongation, DFL2 and TEM1 (Takase et al., 2003; Woo et al., 2010; Matías-Hernández et al., 2014), were down-regulated by isoprene in the two Arabidopsis systems (Fig. 12). These genes are located downstream of PIF in the Phytochrome B (PHYB)-mediated red light signaling pathway (Takase et al., 2003; Woo et al., 2010; Matías-Hernández et al., 2014). Interestingly, TZF5, which is down-regulated by isoprene, is located upstream of PHYB and PIF and is a negative regulator of expression of GA synthesis genes (GA3OX2; Bogamuwa and Jang, 2013, 2016; Fig. 12). The fact that the expression of TZF5, MARD1, DFL2, TEM1, and COP1 is altered by isoprene in a manner that enhances hypocotyl growth indicates that isoprene can activate PIF activity without PHYB and that the positive effects of isoprene on hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis may occur through this pathway. In tobacco, hypocotyl elongation may have been induced by isoprene-mediated enhancement of COP1 expression or a different isoprene-responsive genetic pathway, likely AXS2 (Eckey-Kaltenbach et al., 1993; Ahn et al., 2006; Pičmanová and Møller, 2016) and/or PIP5K2 (Ischebeck et al., 2013).

Figure 12.

Proposed model for how isoprene signaling can affect GA-mediated growth regulation and JA-mediated defense responses. Transcriptomic data revealed that isoprene can alter genes required for both GA accumulation and JA synthesis (genes shown in green font), which can promote both GA-mediated growth and JA-mediated defense simultaneously. We speculate that the observed growth enhancement in Arabidopsis engineered to emit isoprene is likely a result of the up-regulation of PIF. However, interactions between GA and JA pathways occur through DELLA and JAZ proteins (Campos et al., 2016). JA synthesis leads to the degradation of JAZ proteins that release the inhibition of transcription factors to enhance defense-related processes (Campos et al., 2016). Antagonistic interactions between JAZ and DELLA proteins play a part in regulating the growth-defense tradeoff mediated by GA and JA (Campos et al., 2016). Therefore, one possible explanation for the observed variations in isoprene-mediated growth effects in different species is the likely effect of isoprene on the growth-defense tradeoff. Genes belonging to other signaling pathways whose expression was altered by isoprene were omitted from this diagram for the sake of simplicity. Dotted lines and genes written in green font denote isoprene-responsive gene expression revealed during this study. Asterisks denote genes differentially expressed in both Arabidopsis expressing ISPS and Arabidopsis fumigated by isoprene but not differentially expressed in tobacco. Up-regulation and down-regulation of gene expression are denoted by pointed and blunt-ended arrows, respectively (DFL2 and TEM1 expression was down-regulated in the presence of isoprene in Arabidopsis). Solid lines denote signaling pathways that are well established. BBD, Bifunctional nuclease in basal defense response; CBF, CRT/DRE-binding factor; COP1, Constitutively photomorphogenic1, a ubiquitin ligase; CRPK1, Cold-responsive protein kinase1; DELLA, PIF transcription factor repressors; DFL2, Dwarf in light2, a GH3-related (auxin response-related) protein; FT, Flowering locus T; HY5, Elongated hypocotyl5; JAZ, Jasmonate ZIM-domain repressors; JMT, Jasmonic acid carboxyl methyltransferase; LOX, Lipoxygenase; MARD1, Mediator of ABA-regulated dormancy1, a novel zinc finger protein; MYB59, MYB domain protein59; MYC2, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor and a master regulator of JA signaling; OPR3, Oxophytodienoate-reductase3; TEM1, Tempranillo1, a RAV transcription factor; TZF5,Tandem CCCH zinc finger protein5; 14-3-3, highly conserved acidic proteins of the 14-3-3 protein family.

In addition to hypocotyl elongation, isoprene also had a positive effect on the growth of cotyledons, leaf area, leaf length, number of leaves, growth rates, leaf and inflorescence dry weight, early inflorescence initiation, and inflorescence stem height in Arabidopsis. Interestingly, mutant lines of phyB also exhibit elongated hypocotyls, larger cotyledons and larger leaf area and petiole length, reduced leaf curling, early flowering, and longer stems (Campos et al., 2016; Weraduwage et al., 2018). We speculate that these growth phenotypes in isoprene-emitting Arabidopsis lines may be in part a result of isoprene-mediated up-regulation of GA accumulation through TZF5 (and TEM1), with subsequent effects on GA-responsive genes through PIF (Fig. 12). In addition, alterations in AXS2 and PIPK5 may also have contributed to enhanced leaf growth in Arabidopsis. Loivamäki et al. (2007) also reported higher growth rates under both normal growth conditions and moderate heat stress in Arabidopsis lines transformed with an ISPS gene from gray poplar. Another lab that studied interactions between CK production and isoprene emission in the same Arabidopsis lines used in our study also saw faster growth rates and early inflorescence initiation in isoprene-emitting lines B2 and C4 (K.G.S. Dani, S. Pollastri, M. Reichelt, T.D. Sharkey, and F. Loreto, unpublished data). Evidence for higher levels of active CK and significant accumulation of its immediate precursors was also found in B2 and C4. It is proposed that isoprene-mediated higher CK levels facilitate better and faster growth and may be especially beneficial under short-term stress conditions. Overall, it is clear that isoprene-mediated changes to the transcriptome associated with CK signaling does in fact translate to changes in CK production, and this may, in part, explain the enhanced growth in Arabidopsis.

In contrast, cotyledon area, leaf area, leaf and plant stem dry weight, and plant stem height were reduced in the tobacco IE line (Fig. 12). There was no statistically significant effect on growth in the four tobacco IE lines studied by Vickers et al. (2009b) except line 22, where there was a significant enhancement in growth. However, tobacco IE line 32 that was also used in this study exhibited a trend of reduced leaf area and leaf fresh weight (Vickers et al., 2009b). It is possible that variations in isoprene-mediated growth effects are due to slight variations in growth conditions. For example, Arabidopsis lines transformed with ISPS from gray poplar showed faster growth rates on a leaf area basis than the wild type, especially under moderate heat stress (Loivamäki et al., 2007), and also grew better under severe heat stress (Sasaki et al., 2007). Thus, isoprene emission may offer a growth benefit only under a narrow range of environmental conditions. However, we can also provide several explanations for the opposite growth effects seen in Arabidopsis and tobacco, based on how isoprene affects the expression of growth- and defense-signaling genes. First, in contrast to Arabidopsis, the expression of genes of the GA signaling pathway was not altered in tobacco (Fig. 12; Supplemental Tables S2 and S5). Thus, GA-mediated growth effects may not be induced in tobacco. Second, it is possible that the reduction in growth in tobacco is JA mediated. A number of genes involved in JA signaling and JA-associated defense responses were enhanced in both Arabidopsis and tobacco (Fig. 12; Supplemental Table S2 and S3). While GA promotes growth, JA promotes defense responses and inhibits growth (Campos et al., 2016). This tradeoff between growth and defense in plants is mediated through interactions between DELLA and JAZ proteins, in the GA and JA signaling pathways, respectively (Fig. 12).