Abstract

Background: Acupuncture is a recognized integrative modality for managing hot flashes. However, data regarding predictors for response to acupuncture in cancer patients experiencing hot flashes are limited. We explored associations between patient characteristics, including traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) diagnosis, and treatment response among cancer patients who received acupuncture for management of hot flashes. Methods: We reviewed acupuncture records of cancer outpatients with the primary reason for referral listed as hot flashes who were treated from March 2016 to April 2018. Treatment response was assessed using the hot flashes score within a modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (0-10 scale) administered immediately before and after each acupuncture treatment. Correlations between TCM diagnosis, individual patient characteristics, and treatment response were analyzed. Results: The final analysis included 558 acupuncture records (151 patients). The majority of patients were female (90%), and 66% had breast cancer. The median treatment response was a 25% reduction in the hot flashes score. The most frequent TCM diagnosis was qi stagnation (80%) followed by blood stagnation (57%). Older age (P = .018), patient self-reported anxiety level (P = .056), and presence of damp accumulation in TCM diagnosis (P = .047) were correlated with greater hot flashes score reduction. Conclusions: TCM diagnosis and other patient characteristics were predictors of treatment response to acupuncture for hot flashes in cancer patients. Future research is needed to further explore predictors that could help tailor acupuncture treatments for these patients.

Keywords: acupuncture, hot flashes, traditional Chinese medicine, integrative medicine, cancer, complementary health approaches

Introduction

Hot flashes are a common symptom among cancer patients, particularly women with breast cancer who receive endocrine therapy or with chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure1,2 and men with prostate cancer who undergo androgen-deprivation therapy.3 Hot flashes, though not life-threatening, can adversely affect the quality of life and may result in poor tolerance and early discontinuation of treatment.4-6 Most patients with cancer therapy–related hot flashes are limited to receiving non-hormonally based interventions because hormone replacement therapy is contraindicated for them. Non-hormonally based drugs such as antidepressants, gabapentinoids, and other centrally acting agents have shown limited benefit compared with estrogen,7 as well as considerable side effects.8,9

Acupuncture, a therapy that has been used for more than 2500 years as part of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), is now used in at least 103 countries.10 Many comprehensive cancer centers incorporate acupuncture for cancer symptom management.11 Though the underlying mechanisms of acupuncture are not fully understood, its role in the management of various cancer- and treatment-related symptoms has been well characterized.12 Our own published experience in an outpatient cancer care setting has demonstrated statistically and clinically significant effects of acupuncture on self-reported symptoms.13

Acupuncture has shown promising treatment efficacy for managing hot flashes and a low incidence of adverse effects.14-16 Mao et al17 found that the effects of electroacupuncture on hot flashes among women with breast cancer were similar to, but more durable than, those of gabapentin, with fewer side effects. Another large randomized clinical trial found that compared with enhanced usual care alone, the addition of acupuncture was superior in reducing hot flashes and improving quality of life among breast cancer patients.18

A heterogeneous response rate of acupuncture for hot flashes has been reported by many studies12,19,20 and observed by our acupuncture practitioners. This should not be surprising considering well-known variations in disease response to many conventional treatments. However, information about predictors for acupuncture response is much more limited compared with what is known about conventional treatment. One study of 209 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women (age 45-60 years) with hot flashes reported that older age and presence of the TCM diagnosis of kidney yin deficiency predicted low acupuncture response rate.21 Our study aimed to measure the association of patient characteristics, baseline symptoms, and TCM diagnosis with response to acupuncture for management of hot flashes in cancer patients.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This retrospective study was approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Institutional Review Board in accordance with an assurance filed with, and approved by, the Department of Health and Human Services. Acupuncture records of patients treated from March 2016 to April 2018 were identified through a search of the institutional electronic medical records. The primary reason for acupuncture referral, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-10 scores, before and after acupuncture treatment scores from a modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale22 (ESAS; 0-10 scale) including scores for hot flashes, and TCM diagnosis were extracted from acupuncture treatment notes in the medical record. Patients’ demographics, vital signs including weight and height at each visit, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes, and pharmacy data were obtained from the institutional data warehouse.

The study included all patients with cancer who received acupuncture treatment for a primary indication of hot flashes. Each acupuncture session was documented indicating the details of the acupuncture treatment, ESAS scores that were collected immediately before and after treatment, and TCM assessment and diagnosis. For each visit, treatment response was calculated: (ESAS hot flashes score before acupuncture treatment − ESAS hot flashes score after acupuncture treatment) × 100/ESAS hot flashes score before acupuncture treatment. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula weight in kg/(height in m)2. Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated using ICD-9 codes.23 A patient was considered to be on hormonal treatment if he/she received any of the following drugs: tamoxifen, anastrozole, letrozole, megestrol, medroxyprogesterone, fulvestrant, exemestane, megestrol acetate, or toremifene at the time of acupuncture treatment, or his/her acupuncture treatment was within 3 months following leuprolide or 1 month following goserelin administration. Similarly, non-hormonal pharmacologic management for hot flashes was defined as being on venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, citalopram, escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, gabapentin, or pregabalin during the time period of receiving acupuncture.

Intervention

Patients referred to the Integrative Medicine Center from within MD Anderson Cancer Center, a large tertiary institution specializing in cancer care and research, were initially evaluated by a physician and referred for acupuncture treatment based on the physician’s assessment after reviewing the patients’ oncology history and symptoms. Acupuncture treatment was provided in our outpatient center by licensed, experienced (>10 years average) acupuncturists credentialed through the institution’s Medical Staff Office. Initial acupuncture visit duration was approximately 1 hour, with follow-up visits of about 30 minutes. The acupuncturists obtained a symptom history from patients, conducted a physical assessment that included pulse palpation and tongue inspection, and then formulated TCM diagnoses and individualized treatment plans outlining acupuncture point selection. The TCM diagnoses and chosen acupuncture points were based on the clinical judgment of the treating acupuncturist following TCM diagnostic principles. One TCM diagnosis usually represents a group of symptoms rather than a single symptom. For instance, symptoms of fatigue, edema, swelling, abdominal distension, cold extremities, and poor memory and appetite in a patient with hot flashes indicate a diagnosis of damp accumulation, while the presence of sensations of heat, especially in the face in the afternoon, sweating, cheek flush, dizziness, poor vision (especially at night), insomnia, palpitations, and irritability is consistent with a diagnosis of yin deficiency.24 The symptom of hot flashes can be associated with different diagnoses depending on its accompanying symptoms. The acupuncturists were not under mandates of protocols with predetermined TCM diagnosis or acupuncture point selection for individual referring symptoms. TCM assessment and diagnoses were documented in the medical record as part of the acupuncture encounter. The acupuncture procedure involves inserting small, sterile, solid, stainless steel needles, typically 32 to 40 gauge, into specific acupuncture points on the body. The needles are left in place for 20 to 30 minutes. Manual or electrical stimulation of the needles may be applied to augment the acupuncture effects. No restrictions were placed on treatment frequency, which varied according to patient response, changes of symptoms, and patients’ convenience to clinical visits.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was treatment response, defined as (ESAS hot flashes score before acupuncture treatment − ESAS hot flashes score after acupuncture treatment) × 100/ESAS hot flashes score before acupuncture treatment. We used descriptive statistics to report the frequencies, medians, means, and standard deviations of the study variables for the study cohort. Univariate analysis between patients’ characteristics and TCM diagnosis and treatment response was evaluated using the mixed-effects linear regression. Factors with P value below .2 from the univariate analysis were considered for multivariate analysis. Mixed effects linear regression was further applied in the multivariate analysis with variable selection based on conditional Akaike Information Criterion (cAIC) to identify the best set of predictors.25 All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.5.0, The R Foundation, http://www.r-project.org).

Results

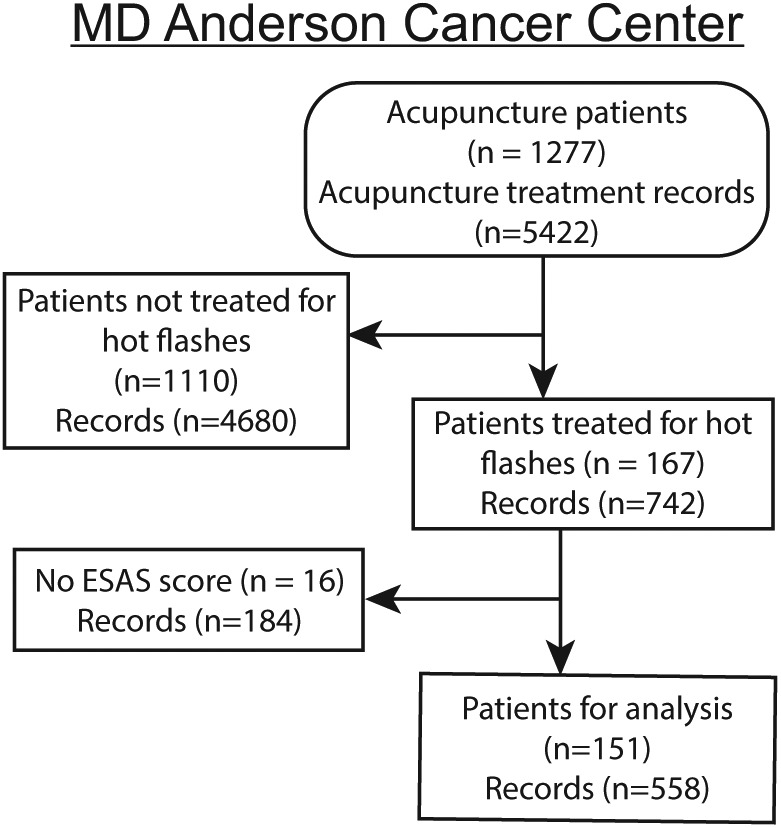

Figure 1 depicts the flow of patient selection. The final cohort included 151 patients and 558 acupuncture treatment records.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study eligibility.

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. Women accounted for 89.9% of the study population, and breast cancer 65.8% of all cancer diagnoses. The median age and BMI were 53 years and 27.6 kg/m2, respectively. The median ESAS hot flashes score before acupuncture treatment was 5. A median of 3 acupuncture treatments were received per patient, with a median treatment response of 25% reduction in the hot flashes score. Table 1 lists the 5 most frequent TCM diagnoses in the study patients, with qi stagnation being the most common. Each patient may have one or more TCM diagnoses.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic, Clinical, and TCM Characteristics.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 167 |

| Age, median [IQR], years | 52 [47-61] |

| Race | |

| White | 122 (73.1) |

| Non-White | 45 (26.9) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 150 (89.8) |

| Male | 17 (10.2) |

| BMI, median [IQR] | 27.6 [23.9-32.8] |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median [IQR] | 2 [2-6] |

| Cancer type | |

| Breast | 102 (65.8) |

| Prostate | 10 (6.5) |

| Other | 55 (35.5) |

| Pretreatment hot flashes score, median [IQR] | 7 [5-8] |

| Patients with pretreatment TCM diagnosis | |

| Qi stagnation | 135 (80.8) |

| Blood stagnation | 95 (56.9) |

| Yin deficiency | 90 (53.9) |

| Qi deficiency | 76 (45.5) |

| Damp accumulation | 42 (25.1) |

| Number of acupuncture treatments, median [IQR] | 3 [1-6] |

| Treatment response, median [IQR], percent | 25% [0% to 66.7%] |

Abbreviations: TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index.

Univariate Analysis

Among the clinical and demographic characteristics, only age was significantly correlated with treatment response (P = .019), with older age having a greater reduction in the hot flashes score (Table 2). None of the patient self-reported symptoms were associated with reduction in the hot flashes score in response to acupuncture, except anxiety level. Anxiety levels were positively correlated with treatment response (P = .054), suggesting the higher the anxiety levels the better the response. A TCM diagnosis of damp accumulation was associated with greater reduction in the hot flashes score (P = .032). Receiving hormonal/endocrine therapy or a pharmacological intervention for hot flashes did not correlate significantly with treatment response of hot flashes to acupuncture.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Treatment Response.

| Factors | Coefficient | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | Age | 0.648 | .019 |

| Body mass index | −0.153 | .710 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2.270 | .185 | |

| Sex—Male | 0.525 | .959 | |

| Race—White | −4.938 | .468 | |

| Patient self-reported symptoms | Anxiety | 1.823 | .054 |

| Depression | 0.965 | .397 | |

| Fatigue | 0.725 | .388 | |

| Sleep problems | −0.491 | .526 | |

| Financial distress | −0.062 | .945 | |

| PROMIS PH | −0.315 | .805 | |

| PROMIS MH | 0.836 | .457 | |

| TCM diagnosis | Qi stagnation | 2.921 | .675 |

| Blood stagnation | 1.241 | .823 | |

| Yin deficiency | 7.356 | .190 | |

| Qi deficiency | −3.300 | .558 | |

| Damp accumulation | 13.263 | .032 | |

| Pharmacologic intervention | Active hormonal therapy | −0.446 | .149 |

| Active antihot flashes therapy | 0.056 | .906 |

Abbreviations: TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; PROMIS PH, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, Physical Health; PROMIS MH, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, Mental Health.

Multivariate Analysis

The model selection for multivariate analysis included 5 factors that were P < .2 from the univariate analysis. The model achieving the minimum cAIC value indicates the best predictive performance in estimating treatment response. The significant factors are shown in Table 3. Age (1.823; P = .018), anxiety level (1.793; P = .056), and TCM diagnosis of damp accumulation (12.276; P = .047) all remained associated with larger decrease in hot flashes score in the multivariate analyses. Though P value for anxiety was .056 indicting marginal significance, the addition of anxiety in multivariate analysis improved the overall predictive performance for acupuncture response.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Treatment Response.

| Factors | Coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.654 | .018 |

| Anxiety | 1.793 | .056 |

| Damp accumulation | 12.276 | .047 |

Discussion

Our study is the first of its kind as we included a large cohort of cancer patients who received acupuncture treatment for hot flashes and examined the association between changes in hot flashes and multiple common demographic and clinical characteristics such as sex, age, self-reported symptoms, pharmacological factors, and TCM diagnosis. It is also unique that our study evaluated TCM diagnosis and treatment response of each individual acupuncture treatment session. The research methodology was designed to model the TCM clinical practice principle of independently evaluating each acupuncture encounter and to reach a TCM diagnosis that may vary from visit to visit as symptom clusters and clinical assessment change. Our study used a novel approach to explore correlations between TCM diagnosis and treatment response in a real-world acupuncture practice setting, and our findings suggest future research designs should include TCM diagnosis as predictors of symptom response to acupuncture treatment.

Although older age was previously reported to be associated with more severe vasomotor symptoms of hot flashes26 and to predict a lower acupuncture response rate,21 our findings indicated age was associated with greater acupuncture response. The difference could be due to our study population being cancer patients only and/or to differences in the study designs. Future studies are needed to confirm such associations in cancer patients and determine whether these clinical factors affect the immediate and cumulative treatment response to acupuncture differently.

Mood disorders including anxiety are common among cancer patients.27 Anxiety is reported to significantly predict hot flashes in menopausal women as well as in patients with breast cancer and treating anxiety is suggested as an intervention target to reduce hot flashes.28,29 Our analysis showed that patient self-reported anxiety level prior to acupuncture treatment was associated with a better treatment response of reducing hot flashes. This interesting observation may not necessarily indicate anxiety as a beneficial predictor of treatment response of hot flashes to acupuncture, but rather is a reflection of the uniqueness of acupuncture as a treatment modality that aims at not only the primary symptom but also the coexisting symptoms. Future studies are needed to further confirm and explore the impact of patient self-reported symptoms on acupuncture treatment response.

Our study patients with the TCM diagnostic category of damp accumulation had a more favorable response to acupuncture than those without damp accumulation. Predicting acupuncture response by TCM diagnosis has rarely been studied. Avis et al21 observed significant differences in TCM diagnosis among women with hot flashes and found kidney yin deficiency was associated with less reduction in hot flashes in response to acupuncture. Similarly, our study also observed significant differences in TCM diagnosis for the primary symptom of hot flashes among the patients, but differently, qi stagnation was the most frequent TCM diagnosis. The current understanding of the relationship between TCM diagnoses/syndromes and disease pathophysiology by conventional Western medicine is very limited. Nevertheless, similar to conventional Western medicine, TCM diagnosis of bodily dysfunction has significant prognostic value.24 The impact of TCM diagnosis on acupuncture treatment response deserves further investigation.

Our study is unique in its study design modeling TCM principles of assessment and treatment by which diagnosis could vary from one acupuncture visit to another depending on accompanying symptom clusters. The clinical practice of acupuncture is often methodologically different from many acupuncture research, which mostly applies pre-fixed acupuncture points based on presumed diagnosis for the targeted symptom without consideration of accompanying symptom clusters. This retrospective review of associations between patient self-reported symptoms and TCM diagnosis and acupuncture treatment response of hot flashes will enrich the current literature, which lacks reports on real-world acupuncture practice. More clinically relevant research is needed to identify predictors of acupuncture treatment response and treatment individualization.

Our retrospective study shares some methodological challenges that has confronted clinical acupuncture research illustrated in many systematic reviews.12,19 First, the association of symptom clusters and TCM diagnosis is not so clearly defined by the TCM diagnostic principles that only an exclusive diagnosis can be concluded from a unique cluster of symptoms. Thus, variations of TCM diagnosis by individual acupuncturists are unavoidable. In addition, the current understanding of biological mechanisms of acupuncture and underlining pathophysiological process of TCM diagnosis is severely lacking. These challenges faced in acupuncture research as well as real-world practice demand extensive basic and clinical acupuncture research collectively to provide the solutions that can produce a standardized guideline for the practice of this ancient Chinese method globally. Our study has some other limitations to note. It focused only on hot flashes in cancer patients and 90% of patients included in the analysis were women. This limits its generalizability to other symptoms, and it may not be representative of response in males. However, sex was not associated with treatment response. Anxiety, among many factors that are involved in nonspecific (placebo) effects of acupuncture,30 has been reported to affect treatment expectation in patients receiving acupuncture therapy.31 Reduction in anxiety is often observed in response to acupuncture that is targeted on other symptoms.32,33 Our observation of anxiety predicting acupuncture response may also reflect nonspecific effects of acupuncture treatment. However, age is not known to affect patient expectation about acupuncture. Though the acupuncture treatments for our patients were initiated by the referral physician’s suggestions, they are free to decide whether or not to receive or continue the treatments. Self-selection bias may be limited, but cannot be excluded in our study. Furthermore, this was not a randomized controlled trial and a comment on efficacy cannot be made with the current design. The time interval between acupuncture treatments and total number of treatments received by each patient differed between patients. The impact of these factors on acupuncture response cannot be excluded and the specificity of acupuncture treatment response cannot be determined. Future prospective studies are needed to determine the optimum acupuncture treatment frequency and duration for hot flashes and to confirm the predictive impact of clinical characteristics and TCM diagnosis on the treatment response.

Conclusions

Age, patient self-reported symptoms, and certain features of TCM diagnoses were predictors of treatment response to acupuncture for hot flashes in cancer patients in a large hospital practice. Future research is warranted to further explore predictors that can guide personalization of acupuncture treatment for these patients.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016672. The research was funded in part through the support of the Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment.

ORCID iD: Wenli Liu  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1036-4564

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1036-4564

References

- 1. Francis PA, Regan MM, Fleming GF, et al. ; SOFT Investigators; International Breast Cancer Study Group. Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:436-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:107-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Higano CS. Side effects of androgen deprivation therapy: monitoring and minimizing toxicity. Urology. 2003;61(2 suppl 1):32-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Zambotti M, Colrain IM, Javitz HS, Baker FC. Magnitude of the impact of hot flashes on sleep in perimenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1708-1715.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Erlik Y, Tataryn IV, Meldrum DR, Lomax P, Bajorek JG, Judd HL. Association of waking episodes with menopausal hot flushes. JAMA. 1981;245:1741-1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:2057-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johns C, Seav SM, Dominick SA, et al. Informing hot flash treatment decisions for breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of randomized trials comparing active interventions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;156:415-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leon-Ferre RA, Majithia N, Loprinzi CL. Management of hot flashes in women with breast cancer receiving ovarian function suppression. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:82-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization. Essential medicines and health products. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014-2023. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm_strategy14_23/en/. Published December 2013. Accessed April 20, 2019.

- 11. Brauer JA, El Sehamy A, Metz JM, Mao JJ. Complementary and alternative medicine and supportive care at leading cancer centers: a systematic analysis of websites. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:183-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zia FZ, Olaku O, Bao T, et al. The National Cancer Institute’s Conference on acupuncture for symptom management in oncology: state of the science, evidence, and research gaps. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2017;2017(52). doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgx005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lopez G, Garcia MK, Liu W, et al. Outpatient acupuncture effects on patient self-reported symptoms in oncology care: a retrospective analysis. J Cancer. 2018;9:3613-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garcia MK, Graham-Getty L, Haddad R, et al. Systematic review of acupuncture to control hot flashes in cancer patients. Cancer. 2015;121:3948-3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Melchart D, Weidenhammer W, Streng A, et al. Prospective investigation of adverse effects of acupuncture in 97 733 patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:104-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walker EM, Rodriguez AI, Kohn B, et al. Acupuncture versus venlafaxine for the management of vasomotor symptoms in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:634-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Xie SX, Bruner D, DeMichele A, Farrar JT. Electroacupuncture versus gabapentin for hot flashes among breast cancer survivors: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3615-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lesi G, Razzini G, Musti MA, et al. Acupuncture as an integrative approach for the treatment of hot flashes in women with breast cancer: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial (AcCliMaT). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1795-1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garcia MK, McQuade J, Lee R, Haddad R, Spano M, Cohen L. Acupuncture for symptom management in cancer care: an update. Curr Oncol Rep. 2014;16:418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pan Y, Yang K, Shi X, et al. Clinical benefits of acupuncture for the reduction of hormone therapy-related side effects in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:602-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Avis NE, Coeytaux RR, Levine B, Isom S, Morgan T. Trajectories of response to acupuncture for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: the Acupuncture in Menopause study. Menopause. 2017;24:171-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hui D, Bruera E. The Edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:630-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wiseman N, Ellis A. Fundamentals of Chinese Medicine. Brookline, MA: Paradigm Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vaida F, Blanchard S. Conditional Akaike information for mixed-effects models. Biometrika. 2005;92:351-370. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gast GC, Samsioe GN, Grobbee DE, Nilsson PM, van der Schouw YT. Vasomotor symptoms, estradiol levels and cardiovascular risk profile in women. Maturitas. 2010;66:285-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:160-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Freeman EW, Sammel MD. Anxiety as a risk factor for menopausal hot flashes: evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging cohort. Menopause. 2016;23:942-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guimond AJ, Massicotte E, Savard MH, et al. Is anxiety associated with hot flashes in women with breast cancer? Menopause. 2015;22:864-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaptchuk TJ, Shaw J, Kerr CE, et al. “Maybe I made up the whole thing”: placebos and patients’ experiences in a randomized controlled trial. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2009;33:382-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Razavy S, Gadau M, Zhang SP, et al. Anxiety related to De Qi psychophysical responses as measured by MASS: a sub-study embedded in a multisite randomised clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2018;39:24-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miller KR, Patel JN, Symanowski JT, Edelen CA, Walsh D. Acupuncture for cancer pain and symptom management in a palliative medicine clinic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36:326-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Molassiotis A, Bardy J, Finnegan-John J, et al. Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4470-4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]