Abstract

Aim:

Cancer diagnosis and treatment depend on pathology reports but naming a cancer is sometimes impossible without specialized techniques. We aimed to evaluate the sensitivity of cytological sub-classification of non-small cell lung carcinoma, not otherwise specified group (NSCLC-NOS) into Adenocarcinoma (AC) and Squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) without using immunohistochemistry.

Methods:

Endobronchial ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration biopsies and cytology slides diagnosed as NSCLC-NOS between 2004- 2008 were reviewed retrospectively. The final diagnosis was reached by immunohistochemistry (TTF-1, p63) when necessary.

Results:

One hundred-twenty nine cases were retrieved. The final diagnoses were as follows: SqCC: 30.3%; AC: 65.7%; combined tumor (3 adenosquamous and 1 small cell + SqCC): 4%. Cytological diagnoses rendered were as follow: Definitely SqCC: 10.1%; favor SqCC: 14.1%; definitely AC: 38.4%; favor AC: 35.4%; NSCLC-NOS: 2%. The sensitivity and specificity of cytology were 86.3 and 87.5% for AC diagnosis respectively.

Conclusion:

Positive and negative predictive value of cytology was 95.3% and it was even 100% for well to moderately differentiated tumors. There was a tendency to sub-classify poorly differentiated SqCC as AC. Papanicolaou stain increased the diagnostic accuracy of SqCC. The combined tumor rate was 4% and after recognizing a tumor component, the second component was missed if the slide examination was terminated prematurely.

Keywords: Cytology, lung carcinoma, non-small cell lung carcinoma, sub-classification, poor-resource yes, resource-poor is better

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 70% of lung cancer patients are diagnosed in the advanced stage. Diagnosis and staging and treatment are done only with cytology (sputum, endobronchial cytology, and transthoracic biopsy) and core biopsy.[1,2,3,4,5] The accuracy rate of these methods to sub-classify lung tumors into small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is 98%.[6]

The histopathologic distinction of lung carcinoma based on the 2004 World Health Organization classification of SCLC and NSCLC became inadequate in the light of the genetic diversity of the tumors in what is otherwise called “NSCLC”. Additionally, bevacizumab and pemetrexed that are used for NSCLC treatment necessitate sub-classifying of NSCLC into adenocarcinoma (AC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC).[1] With the ready-to-use immunohistochemical (IHC) markers, differentiating of NSCLC into AC and SqCC is not a huge task for pathologists, but these techniques, however, come with rising costs and specialized equipment. This is especially true for low- and middle-income countries.[7] Especially in sub-Saharan Africa, pathology services are poorly developed[8,9,10] and low-cost tests such as cytology are needed to provide accurate pathology reports, with the ultimate goal of improving treatment of patients with lung cancer in these regions.

In spite of a high biopsy-based accuracy rate observed in the distinction of SCLC and NSCLC in Western countries,[11] no NSCLC subtyping has been sought on the basis of resource-poor settings. In this study, NSCLC cases admitted to pathology laboratory together with cytology samples were sub-classified by senior pathologists so as to determine the discriminatory power of cytology without IHC markers and to find potential pitfalls that the pathologist faces while struggling with these slides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed NSCLC, not otherwise specified (NSCLC-NOS) cases diagnosed at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, between 2004 and 2008. Exclusion criteria were the absence of cytology or histology slides for each case. For each case, cytologic and histologic slides were reviewed separately by two senior pathologists (BCAK) to whom the diagnosis was masked. To reach final diagnosis, the immunostains thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) (clone 8G7G3/1; Dako) and p63 (catalog No. CM163C; Ventana Medical Systems Inc., and Biocare Medical LLC) were applied to cases for tumor classification. Cytologic and histologic diagnoses were made on the basis of guidelines from the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, the American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society. These diagnoses included definitely AC, favor AC, definitely SqCC, favor SqCC, and NSCLC-NOS.[12,13] If clear-cut evidence of pearl formation and keratinization for SqCC differentiation and glandular structure for AC differentiation were present, these cases were accepted as AC or SqCC. Even if both immunostainings were negative but there was an obvious keratin production or glandular arrangements in the tumor histologically, then the diagnosis was given according to the histological appearance. A similar practice was used when there were no tumor cells on the immune staining slides. For other cases, the final diagnosis was determined with p63 or TTF-1 immunostain. Only p63 immunoreactivity was accepted for a SqCC diagnosis, whereas TTF-1 positivity was accepted for AC. When positivity for TTF-1 and p63 was seen together in the same biopsy but in different cells, the diagnosis was assigned as adenosquamous cell carcinoma. If cytology was NSCLC-NOS, histology was NSCLC-NOS, and IHC was not satisfied, then the final diagnosis was NSCLC-NOS.

RESULTS

Between January 2004 and December 2008, 129 NSCLC-NOS cases were retrieved. Ninety-nine of these cases were available for the study. Patients’ informed consent was not obtained because of the retrospective nature of the study. All slides were archived materials. Clear-cut evidence of pearl formation and keratinization was seen in 14 cases, and the glandular structure was seen in fifty cases. Together with the diagnosis of the remaining cases supported by the IHC findings, the final diagnoses were as follows: SqCC (30 cases), AC (65 cases), adenosquamous carcinoma (3 cases), and squamous + small cell mix carcinoma (1 case) [Table 1]. The corresponding cytological diagnoses of these cases were as follows: definitely SqCC (10 cases), favor SqCC (14 cases), definitely AC (38 cases), favor AC (35 cases), and NSCLC-NOS (2 cases) [Table 2]. When we excluded two NSCLC-NOS cases and included four combined tumors in which at least one component was recognized by the pathologist, we noticed that 84 out of 97 cases (86.8%) were sub-classified successfully by cytology. Discordant 13 cytological diagnoses were summarized in Table 3. Most of these cases were categorized as “favor AC:” 8 out of 13 cases. The cytological diagnoses of these discordant cases were as follows: 2 definitely AC, 8 favor AC, and 3 favor SqCC.

Table 1.

The cytological and the final diagnoses of the cases

| Final diagnosis | Cytological diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | SqCC | NSCLC-NOS | Total | |

| AC | 61 | 3 | 1 | 65 |

| SqCC | 10 | 19 | 1 | 30 |

| Adenosquamous CC | 2a | 1b | - | 3 |

| SqCC + small CC | - | 1c | - | 1 |

| Total | 63a/73 | 21b,c/24 | 2 | 99 |

aSqCC, bAC, and cSmall CC component missed at cytology. AC: Adenocarcinoma, SqCC: Squamous cell carcinoma, CC: Cell carcinoma, NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer, NOS: Not otherwise specified

Table 2.

Topographic distribution of the cases rendered cytologically and histologically

| Cell-block diagnosis without immunohistochemistry | Cytological diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely AC | Favor AC | Definitely SqCC | Favor SqCC | NSCLC-NOS | Total | |

| Definitely AC | 34 | 16 | - | - | - | 50/50 |

| Favor AC | 1 | 5 1 SqCC |

1 SqCC | 2 AC | - | 8/10 |

| Definitely SqCC | - | 2 SqCC 1 AdSqCCa |

5 1 small + SqCCc |

4 | 1 SqCC | 14a,c/14 |

| Favor SqCC | 2SqCC | 2 SqCC 1 AC |

2 | 7 | - | 13/14 |

| Adenosquamous CC | 1a | 1/1 | ||||

| NSCLC-NOS | - | 4 3 SqCC |

1 adenosquamous CC |

1 AC | 1d | 10 |

| Total | 36a/38 | 27a/35 | 10b,c/10 | 11/14 | 2 | 99 |

aSqCC, bAC, and cSmall CC component missed at cytology; dThis case is AC by immunohistochemistry. Smaller fonts are misdiagnosed as either cytologically or histologically and underlined three cases show final diagnosis. AC: Adenocarcinoma, SqCC: Squamous cell carcinoma, CC: Cell carcinoma, NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer, NOS: Not otherwise specified

Table 3.

The cytological distribution of the discordance cases according to their final diagnoses

| Case # | Cytological diagnosis | Final diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | Favor AC | SqCC | Favor SqCC | ||

| 10 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 14 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 15 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 22 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 23 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 30 | 1 | Adenocarcinoma | |||

| 31 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 49 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 52 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 60 | 1 | Adenocarcinoma | |||

| 84 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 85 | 1 | SqCC | |||

| 114 | 1 | Adenocarcinoma | |||

| Total | 2 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 13 |

AC: Adenocarcinoma, SqCC: Squamous cell carcinoma

The corresponding cell-block diagnoses of the cases were as follows: definitely SqCC (14 cases), favor SqCC (14 cases), definitely AC (50 cases), favor AC (10 cases), and NSCLC-NOS (10 cases) [Table 4]. When we excluded ten NSCLC-NOS cases and three combined tumors in which at least one component was recognized by the pathologist, we noticed that 83 out of 86 cases (97.64%) were sub-classified successfully by histology only. The cell-block diagnoses of these three discordant cases were as follows: 2 cases of favor AC and 1 case of favor SqCC.

Table 4.

The cell-block and the final diagnoses of the cases

| Final diagnosis with immunohistochemistry | Cell-block diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely AC | Favor AC | Definitely SqCC | Favor SqCC | NSCLC-NOS | Adenosquamous CC | Total | |

| AC | 50 | 8 | - | 1 | 6 | - | 69 |

| SqCC | - | 2 | 12 | 13 | 3 | - | 28 |

| Adenosquamous CC | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| SqCC + small CC | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Total | 50 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 99 |

AC: Adenocarcinoma, SqCC: Squamous cell carcinoma, CC: Cell carcinoma, NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer, NOS: Not otherwise specified

DISCUSSION

Lung cancer treatment had been classified as SCLC and NSCLC for many years. NSCLC classification is actually a heterogeneous group that includes AC, SqCC, and large cell carcinoma, but these cases were used to classify and were treated as a single cancer type.

The innovations, established in carcinogenesis, have marked a new era. For example, epidermal growth factor receptor mutation was detected in AC cases and this tumor has begun to be treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.[14] While pemetrexed is a safe drug, the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody bevacizumab causes pulmonary hemorrhage in patients who have SqCC. Hence, treating all NSCLC cases as a whole group is not advisable, and pathologists are to be expected to sub-classify NSCLC cases as much as possible. The histopathological sub-classification of NSCLC by a pathologist is not difficult when keratin production or gland formation is observed under the light microscope. When absent, IHC is complementary, though expensive, and it needs special techniques.[7,8,9,10]

When patients are admitted to the hospital at the very first time, almost 70% of the lung cancer is at the advanced stage, and the diagnosis is made with sputum or bronchial lavage cytologically.[3,4,5] Cytology is especially useful for diagnosing and staging of peripherally or centrally located bronchial tumors.[15,16] As a matter of fact, 31.4% of lung cancer staging is done by this method in Western countries,[17,18] and the sensitivity and specificity for cancer diagnosis are reported to be 85%–92% and 100%, respectively.[19,20] To the best of our knowledge, there is no such study done for cytological sub-classification of NSCLC. We evaluated the concordance between the final diagnosis and histological diagnosis of cell blocks in our study. It was 86 out of 96 (89.6%) cases. This concordance was seen in 84 out of 97 cases (86.6%) for cytological diagnosis. Although the concordance rate we achieved with histology seems a bit better, the number of NSCLC-NOS was five times common at the histological diagnosis compared to cytology (10 vs. 2 cases). In other words, more cases were left unclassified during histological evaluation (10.1% vs. 2.02%). It seems that either we feel more confident while sub-classifying these cases with cytology, or cytology reveals more identifiable morphological features to reach a diagnosis. Indeed, details of cells are easily distinguished cytologically and, when we excluded combined tumors, the number of cases that were failed to be sub-classified by cytology and histology have been pretty much the same in this study (15.95 and 12.5%, respectively). Moreover, while four cases in which cell-block diagnosis was NSCLC-NOS have been successfully sub-classified by cytology, only one case in which cytological diagnosis was NSCLC-NOS has been sub-classified successfully by histology [Table 2].

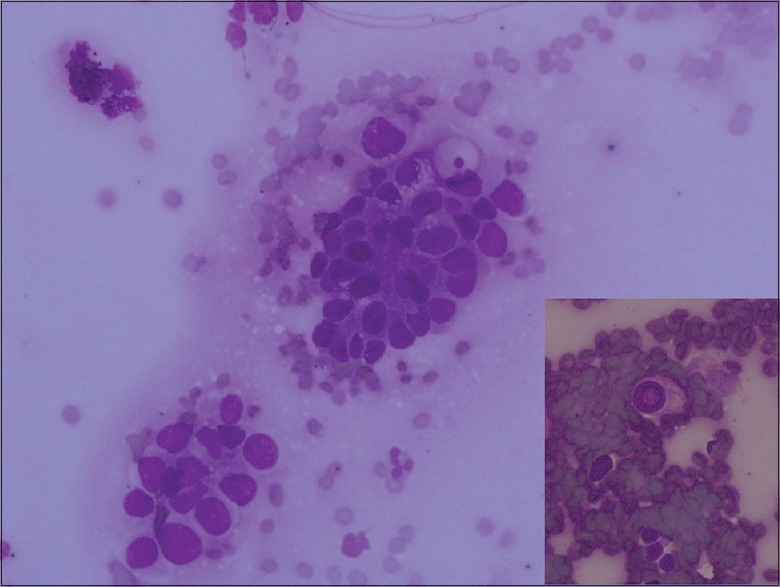

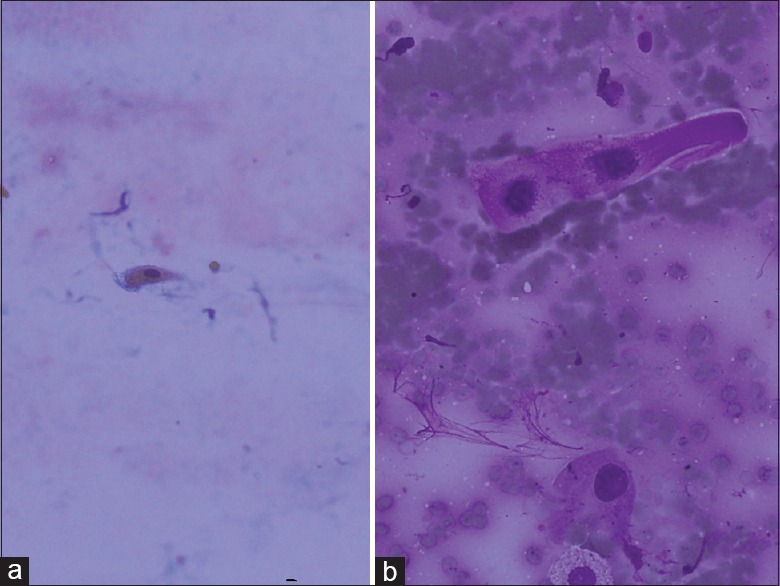

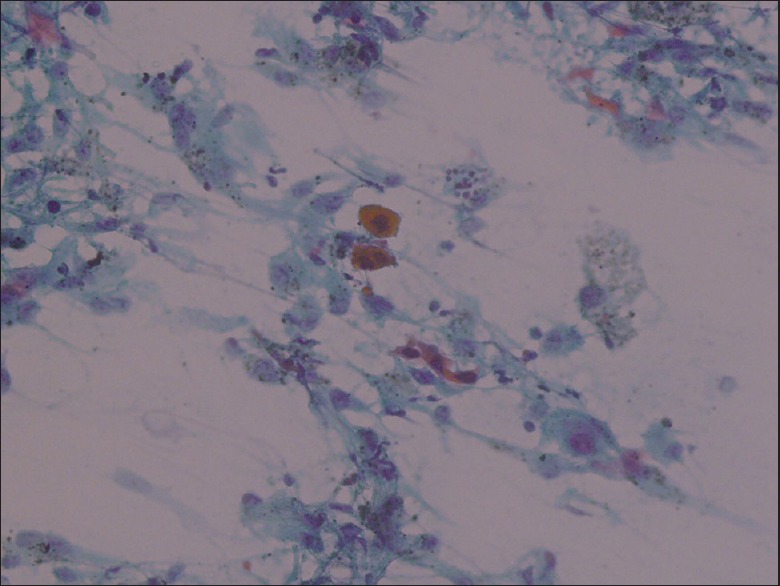

Cytologically, the AC diagnosis is not difficult in the presence of glands, three-dimensional cell clusters, papillary structures, polarity described as pushing the nucleus to one edge, and intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions [Figure 1]. These structures were recognized easily and reported as “definitely AC.” However, two cytological “definitely AC” diagnoses have been SqCC at the final step, and the sensitivity of cytology has been 94.7% for “definitely AC” diagnosis [Table 1]. Cytologically, SqCC diagnosis is not difficult in the presence of keratinization, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and tad-pole cells [Figure 2]. These cases were recognized easily as well and reported as “definitely SqCC.” All cases that were diagnosed as “definitely SqCC” have been SqCC at the final step, and the sensitivity of histology has been 100% for “definitely SqCC” diagnosis [Table 1]. Our cases in this category consisted of well-differentiated tumors and there is no cytological difficulty in well-differentiated SqCC diagnosis. Between the staining methods, we found that Papanicolaou (PAP) stain was superior to Giemsa stain for detecting cytoplasmic keratinization [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

The cell group that tends to form a lumen. Polarity by pushing the nucleus to one edge is easily appreciated (Giemsa, ×20). Intranuclear cytoplasmic curve typical for adenocarcinoma (Giemsa, ×40)

Figure 2.

(a) Keratinized cell, PAP, ×20 (b) tad-pole cell. This cell seen as stretching of cytoplasm is typical for squamous cell carcinoma (Giemsa, ×40)

Figure 3.

Cytoplasmic eosinophilia, typical for squamous cell carcinoma (PAP, ×20)

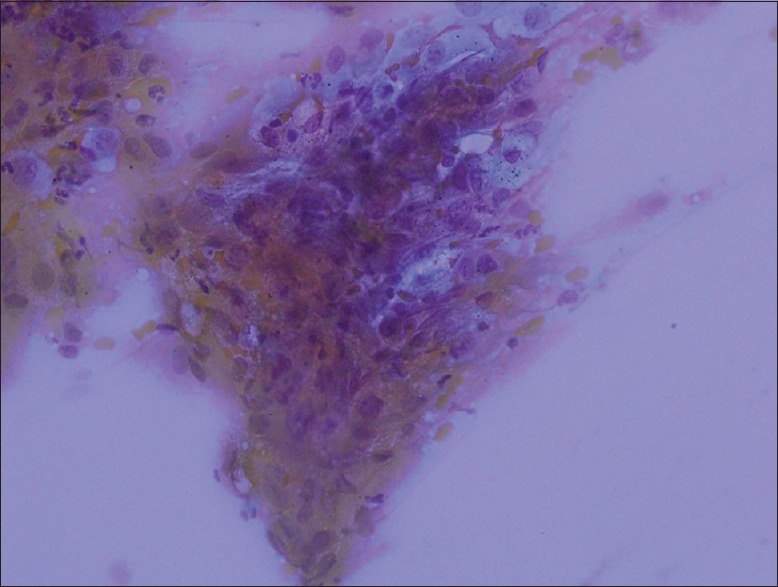

The sensitivity of “favor AC” and “favor SqCC” has been a bit complicated [Table 2]. These cases were moderately or poorly differentiated tumors. At the final step, 8 out of 35 cases which were diagnosed as “favor AC” and 3 out of 14 cases which were diagnosed as “favor SqCC” have been SqCC and AC, respectively. The sensitivity for “favor AC” and “favor SqCC” diagnosis has been 77.14% and 78.57%, respectively [Table 2]. The sensitivity of cytology in both well-differentiated tumors and moderately differentiated tumors has been close to each other no matter if it is AC or SqCC. In this study, the reason why the diagnosis of “favor AC” was given instead of SqCC was the staining quality of the slide rather than the misinterpretation: as stated above, the cellular features of SqCC are better seen in PAP staining and, in our laboratory practice, the first slide which is rich in cells is stained with Giemsa and the second slide which has fewer cells is stained with PAP [Figure 4]. In addition, staining quality was found sub-optimal for these slides and instead of to de-color and to re-stain these slides, we tried to sub-classify these cases as much as possible, even if slides were hypocellular [Figure 4]. If these slides had been re-stained again, we believe that our cytological sensitivity in “favor SqCC” diagnosis would have been higher.[21]

Figure 4.

An example of suboptimal slides. The details of the cell group cannot be distinguished (Giemsa, ×20)

The 55.3% of fine-needle aspiration evaluation is done by general pathologists in the UNITED STATES.[22] As a general pathologist, there was a tendency to sign out the case as “favor AC” if differentiation of cells was not obvious as seen in “definitely” category: uniform cell groups are seen in nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and relatively thinner chromatin and “red single nucleolus” were misinterpreted as AC by the pathologist. We also noticed that whenever seen, indistinct cytoplasmic borders which are described for AC have been misinterpreted as “favor AC” by the pathologist.[22]

There were limitations to our study. Our study population consisted of endobronchial ultrasound materials. Variables such as specimen adequacy and nonmalignant conditions such as metaplasia-dysplasia were not evaluated. We also did not compare interobserver variation in cytopathological assessment between general pathologists and a specialist in lung cytology. Moreover, the ability of the radiologist that could affect the specimen adequacy was not included in the study.[23] For example, in a questionnaire study conducted in the US, 50% of the doctors who had a subspecialty in lung diseases pointed out that their aspiration training was not sufficient.[2]

CONCLUSION

The pathologist's sufficiency for making a distinction between AC and SqCC in well-differentiated tumors is closer to 100%, whereas this rate lowers in moderately differentiated tumors. As the differentiation of the tumor decreases, the tendency to make an AC diagnosis increases erroneously. The main reason for this is the subjective criteria in the evaluation of the cell borders, chromatin, and nucleolus. Considering the rate of 4% combined tumor that was seen in this study, the whole slide must be scanned, not to rush out for diagnosis. Well-prepared and stained cytological samples provide an enormous improvement at the pathologist's diagnostic skill. Cytology, with or without cell block, successfully sub-classifies NSCLC-NOS cases and can be a substitute for IHC in resource-poor laboratories and in low-income countries. Pathologist's experience is a must. In either way, 1% of the case will be left unclassified due to hypocellularity.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Study design: BC and TB; reviewing slides: BC and AK; writing draft: BC.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, ethical approval was not sought.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

AC - AdenoCarcinoma

IHC - Immunohistochemistry

INCI - Intra-nuclear cytoplasmic inclusion

NSCLC - Non Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

NSCLC-NOS - Non Small Cell Lung Carcinoma-Not Otherwise Specified

NPV - Negative Predictive Value

PPV - Positive Predictive Value

SCLC - Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

SqCC - Squamous Cell Lung Carcinoma

TTF-1 - Thyroid Transcription Factor-1.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Contributor Information

Betul Celik, Email: bet_celik@yahoo.com.

Tangul Bulut, Email: tangul07@yahoo.com.

Andras Khoor, Email: Khoor.andras@mayo.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ecka RS, Sharma M. Rapid on-site evaluation of EUS-FNA by cytopathologist: An experience of a tertiary hospital. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:1075–80. doi: 10.1002/dc.23047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu Y, Puri V, Crabtree TD, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Patterson AG, et al. Attaining proficiency with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:1387–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.07.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris CL, Toloza EM, Klapman JB, Vignesh S, Rodriguez K, Kaszuba FJ. Minimally invasive mediastinal staging of non-small-cell lung cancer: Emphasis on ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration. Cancer Control. 2014;21:15–20. doi: 10.1177/107327481402100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong X, Qiu X, Liu Q, Jia J. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in the mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1502–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raptakis T, Boura P, Tsimpoukis S, Gkiozos I, Syrigos KN. Endoscopic and endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle aspiration in the mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivera MP, Mehta AC, Wahidi MM. Establishing the diagnosis of lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed. American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e142S–65S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeder LF, Elbireer A, Jackson JB, Amukele TK. Laboratory diagnostics market in East Africa: A survey of test types, test availability, and test prices in Kampala, Uganda. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.African Strategies for Advancing Pathology. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec14]. Available from: http://www.pathologyinafrica.org .

- 9.Rambau PF. Pathology practice in a resource-poor setting: Mwanza, Tanzania. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:191–3. doi: 10.5858/135.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adesina A, Chumba D, Nelson AM, Orem J, Roberts DJ, Wabinga H, et al. Improvement of pathology in Sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e152–7. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celik B, Khoor A, Bulut T, Nassar A. Rapid on-site evaluation has high diagnostic yield differentiating adenocarcinoma vs. squamous cell carcinoma of non-small cell lung carcinoma, not otherwise specified subgroup. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:167–72. doi: 10.1007/s12253-014-9802-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–85. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joseph M, Jones T, Lutterbie Y, Maygarden SJ, Feins RH, Haithcock BE, et al. Rapid on-site pathologic evaluation does not increase the efficacy of endobronchial ultrasonographic biopsy for mediastinal staging. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:403–10. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson AG, Gonzalez D, Shah P, Pynegar MJ, Deshmukh M, Rice A, et al. Refining the diagnosis and EGFR status of non-small cell lung carcinoma in biopsy and cytologic material, using a panel of mucin staining, TTF-1, cytokeratin 5/6, and P63, and EGFR mutation analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:436–41. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c6ed9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonifazi M, Sediari M, Ferretti M, Poidomani G, Tramacere I, Mei F, et al. The role of the pulmonologist in rapid on-site cytologic evaluation of transbronchial needle aspiration: A prospective study. Chest. 2014;145:60–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Köksal D, Demıraǧ F, Bayız H, Koyuncu A, Mutluay N, Berktaş B, et al. The cell block method increases the diagnostic yield in exudative pleural effusions accompanying lung cancer. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2013;29:165–70. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2013.01184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karnak D, Ciledaǧ A, Ceyhan K, Atasoy C, Akyar S, Kayacan O, et al. Rapid on-site evaluation and low registration error enhance the success of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy. Ann Thorac Med. 2013;8:28–32. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.105716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travis WD, Rekhtman N, Riley GJ, Geisinger KR, Asamura H, Brambilla E, et al. Pathologic diagnosis of advanced lung cancer based on small biopsies and cytology: A paradigm shift. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:411–4. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d57f6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Da Cunha Santos G, Ko HM, Saieg MA, Geddie WR. “The petals and thorns” of ROSE (rapid on-site evaluation) Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:4–8. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madan M, Bannur H. Evaluation of fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of lung lesions. Turkish J Patol. 2010;26:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louw M, Brundyn K, Schubert PT, Wright CA, Bolliger CT, Diacon AH. Comparison of the quality of smears in transbronchial fine-needle aspirates using two staining methods for rapid on-site evaluation. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:777–81. doi: 10.1002/dc.21628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sturgis CD, Nassar DL, D’Antonio JA, Raab SS. Cytologic features useful for distinguishing small cell from non-small cell carcinoma in bronchial brush and wash specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:197–202. doi: 10.1309/8MQG-6XEK-3X9L-A9XU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dumonceau JM, Koessler T, van Hooft JE, Fockens P. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration: Relatively low sensitivity in the endosonographer population. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2357–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i19.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]