Abstract

The loss of sexual ornaments is observed across taxa, and pleiotropic effects of such losses provide an opportunity to gain insight into underlying dynamics of sex-biased gene expression and intralocus sexual conflict (IASC). We investigated this in a Hawaiian field cricket, Teleogryllus oceanicus, in which an X-linked genotype (flatwing) feminizes males' wings and eliminates their ability to produce sexually selected songs. We profiled adult gene expression across somatic and reproductive tissues of both sexes. Despite the feminizing effect of flatwing on male wings, we found no evidence of feminized gene expression in males. Instead, female transcriptomes were more strongly affected by flatwing than males’, and exhibited demasculinized gene expression. These findings are consistent with a relaxation of IASC constraining female gene expression through loss of a male sexual ornament. In a follow-up experiment, we found reduced testes mass in flatwing males, whereas female carriers showed no reduction in egg production. By contrast, female carriers exhibited greater measures of body condition. Our results suggest sex-limited phenotypic expression offers only partial resolution to IASC, owing to pleiotropic effects of the loci involved. Benefits conferred by release from intralocus conflict could help explain widespread loss of sexual ornaments across taxa.

Keywords: demasculinization, feminization, intralocus sexual conflict, sexual dimorphism, sex-biased gene expression, Teleogryllus oceanicus

1. Introduction

Sex-biased gene expression produces striking phenotypic differences in species where the sexes share a substantial portion, if not all, of the same genome [1–4]. Such evolved differences between sexes in gene regulation play an important role in attenuating intralocus sexual conflict (IASC), which arises when sexes are under contrasting selection pressures at shared loci, by achieving phenotypic dimorphism [5–8]. However, it is increasingly recognized that resolution of such conflict is not necessarily complete [9–12], and that IASC can persist even when genes and phenotypes have evolved under contrasting selection pressures to exhibit sex-biased or even sex-limited expression [13,14]. One of the reasons for this is pleiotropy exerted by loci involved in the conflict upon other traits which are not directly under selection (figure 1). Sexual trait loci can thus exert spillover effects across sexes and tissues. For example, the enlarged mandibles of male broad-horned flour beetles Gnatocerus cornutus are genetically associated with reduced female lifetime fecundity [13] despite their sex-limited expression, illustrating incomplete resolution of associated IASC.

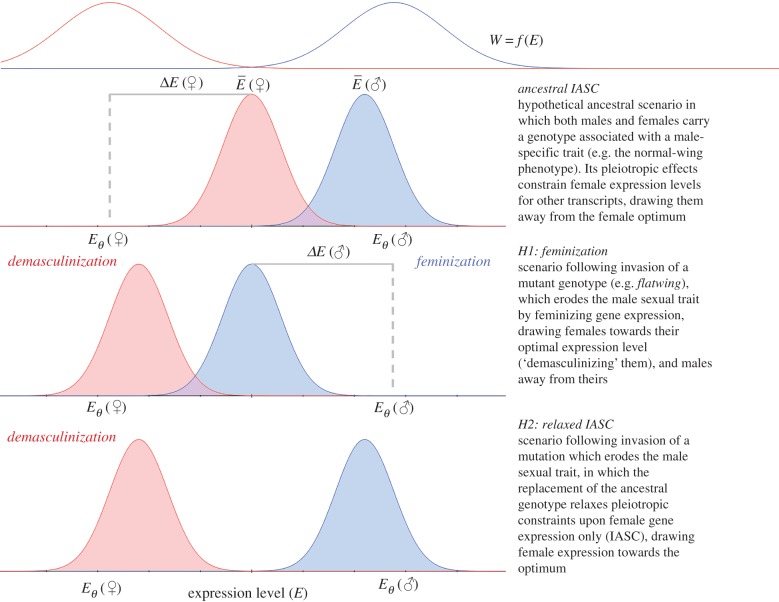

Figure 1.

Hypothetical effects of male sexual trait loss on IASC at the level of gene expression. The schematic shows expression levels (E) and fitness (W) for a transcript assumed to be pleiotropically influenced by a sexual trait locus, thus contributing to incompletely resolved IASC. Expression optima (Eθ) and observed average expression values () differ between the sexes, and shaded curves illustrate frequency distributions for sex-specific expression. Within each sex, fitness is a function of expression level, maximized at the optimum (top red and blue lines indicating hypothetical stabilizing fitness functions for females and males, respectively). Thus, ΔE describes displacement from the optimum level of expression for each sex. The descriptors ‘feminization’ and ‘demasculinization’ refer to the identity of the individual under consideration: females whose gene expression shifts away from the male optimum are demasculinized, whereas males whose gene expression shifts in the same direction are feminized. (Online version in colour.)

As well as its role in regulating differences between sexes, recent studies have demonstrated that varying degrees of sex-biased gene expression are associated with intra-sexual phenotypic variance, often with fitness-associated effects [15]. Pointer et al. [16] found subordinate males of the wild turkey Meleagris gallopavo exhibit feminized patterns of gene expression relative to more ornamented dominant males. Similarly, in the bulb mite Rhizoglyphus robini, ‘fighter’ male morphs show exaggerated transcriptional sexual dimorphism compared with unarmoured ‘scrambler’ males [17], and are associated with increased IASC at the population level [18,19]. A fundamental assumption of sexual selection models is that such elaborated, dimorphic sexual traits should eventually be checked by countervailing natural selection [20–22], but evidence for the involvement of sex-biased pathways of gene expression in naturally selected adaptations is surprisingly limited, and the consequences for IASC after sexual trait reduction or loss are therefore of key interest.

To explore these consequences, we examined the effects of sexual trait loss on patterns of sex-biased gene expression in the rapidly evolving Hawaiian field cricket, Teleogryllus oceanicus. Approximately 15 years ago, male morphs incapable of producing sexual advertisement calls were observed to appear and rapidly spread on multiple Hawaiian islands under natural selection from a phonotactic parasitoid fly, Ormia ochracea [23]. Obligate silence is caused by mutation(s) that cause males to develop female-like wing venation, erasing sound-producing structures and protecting them against fatal parasitism. The silent male phenotype, flatwing, segregates as a single-locus variant (flatwing) on the X chromosome (sex determination is XX/XO; males and females share all genes), though the exact nature of the mutation(s) is not known [24]. Although it is transmitted on the X, flatwing's effects upon wing phenotype appear to be male-limited; female carriers show no readily detectable wing differences. There is evidence for widespread pleiotropic effects of flatwing in both sexes [25,26], and males carrying the genotype exhibit more female-like cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) [24], in addition to their feminized wing membranes. Given the potential role of pleiotropy in IASC (figure 1), we profiled gene expression from a range of non-wing, somatic and gonad tissues of adults from lines that were pure-breeding for flatwing or normal-wing genotypes. Our aims were to test the role of sex-biased genes in evolved song loss, and explore the latter's consequences for IASC.

If flatwing widely impacts sex-biased pathways of gene expression, we anticipated one of two patterns among affected loci. Given its feminizing effect in male wing tissues, and upon male cuticular hydrocarbons, flatwing might be associated with a general increase in female-biased gene expression, demasculinizing female carriers and feminizing male carriers (hypothesis 1 in figure 1) [19,27]. An alternative, but non-mutually exclusive, scenario is that the loss of the male sexual trait releases female gene expression from pleiotropic IASC-associated constraints, in which case we anticipated upregulation of female-biased (or downregulation of male-biased) gene expression (demasculinization) predominantly affecting females (hypothesis 2 in figure 1). Unexpectedly, we found that female gene expression was much more strongly affected by carrying the flatwing genotype than was males', particularly in thoracic muscle and gonad tissues. Gene expression in adult flatwing males showed no evidence of being feminized, but we did observe demasculinized gene expression among female carriers consistent with predictions under relaxed IASC. In a follow-up experiment, we found that flatwing males had reduced testes mass while flatwing-carrier females showed no differences in egg production, but exhibited higher body condition. Our results show that at adult stages, female gene expression is more strongly affected by a genotype responsible for the loss of a male sexual trait. Females also show a pattern of demasculinized gene expression and increased body condition, and analyses of the tissue-specificity of gene expression supported a role for pleiotropy in driving IASC in this system. These findings are consistent with female release from constraints relating to IASC in the rapid spread of a mutation associated with the loss of a male sexual trait, a phenomenon which may play an important role in the widely observed loss of sexual ornaments [28].

2. Material and methods

(a). Sampling, sequencing and differential expression analysis

Detailed descriptions of all methodologies are provided in the electronic supplementary material, Methods. Briefly, we collected tissue samples from virgin adults (ca three months from egg stage) from replicate lines breeding pure with respect to each morph genotype (flatwing ‘FW’ or normal-wing ‘NW’). RNA was extracted from three tissues (neural, thoracic and gonads) of a single male and a single female from each of six lines (n = 3 lines of each genotype), for a total of 36 samples from 12 individuals. The lines were all bred from the same laboratory population originally established from Kauai, with no differences in selective regime (see the electronic supplementary material, Methods and [25]). Multiple lines were included in each group to account for between-line variance and to enable detection of expression differences attributable to morph genotype. Females were homozygous diploid for the respective genotype while males were hemizygous (XX/XO). Dissections and Trizol RNA extractions were performed following [26].

Paired-end reads of all 36 samples were generated on an Illumina HiSeq 2000, and a de novo transcriptome was assembled from trimmed reads of all samples in Trinity using in silico normalization [29]. Similar transcripts were clustered in CD-hit-est [30], and lowly expressed transcripts (those not expressed at greater than 1 count per million in at least three samples) and transcripts without an open reading frame of greater than 100 amino acids were filtered from the transcriptome. Reads were aligned to the transcriptome using Bowtie2 [31] with strand-specific settings, and quantified in RSEM [32]. Differential expression (DE) analyses were performed in edgeR [33] at the level of Trinity ‘genes’; henceforth referred to as ‘transcripts’ in acknowledgement that not all Trinity-identified genes passing filtering will represent genes in the strictest sense. Because our analysis was at the gene level, isoform variants should not contribute to the patterns of DE we observe. Clustering of similar genes by CD-hit-est (see above) was used to further ensure isoform variants were not represented as multiple genes, and we used the results of BUSCO analysis of conserved genes [34] to verify that our transcriptome was not highly duplicated. Separate models were constructed for somatic (neural, thoracic muscle) and gonad tissues, to examine effects of sex and morph, with significance testing performed using likelihood ratio tests. To restrict our analyses to transcripts showing strong evidence of DE, we adopted a conservative significance threshold of false discovery rate-adjusted p (FDR) < 0.01 to consider a transcript significantly DE or sex-biased. We checked whether results qualitatively changed if we used another common approach of imposing a fold-change threshold of greater than 2 for a transcript to be considered DE/sex-biased, with FDR < 0.05 (e.g. [35]), and found they did not (see Results).

Sequences of DE transcripts were entered as BLASTX queries against the NCBI non-redundant protein database, with an e-value threshold of 10−3 and a maximum of 20 hits. Mapping and annotation were performed in Blast2GO [36] with default parameters. Functional enrichment of gene ontologies (GO) was assessed using transcripts which passed filtering and showed homology with Drosophila melanogaster proteins.

(b). Gene expression feminization, demasculinization and tissue-specificity

We defined feminized and demasculinized expression, applied to males and females respectively, as upregulation of female-biased transcripts (or downregulation of male-biased transcripts) in males, and downregulation of male-biased transcripts (upregulation of female-biased transcripts) in females (figure 1). Thus, the terminology indicates the sex experiencing the effect. Identification of sex-biased genes was performed using differential expression analysis, averaging expression values across both morph genotypes in each sex; genes upregulated at FDR < 0.01 in males were considered male-biased, and genes upregulated in females considered female-biased. To test for feminization and demasculinization, we took the subset of transcripts that were DE in both morph genotype and sex comparisons and compared the direction of change between the two for each tissue separately.

To understand whether changes in expression associated with morph genotype were correlated between sexes, we tested whether log-fold changes in expression for transcripts DE in one or both sexes were correlated between males and females. We also investigated the level of tissue-specificity of genotype-associated effects in each sex by comparing log-fold changes among all transcripts DE in either comparison [37]. To test whether sex-limited and tissue-specific transcripts were less likely to be DE between morph genotypes, which could support the involvement of pleiotropy affecting genes shared between sexes, we subset for each sex*tissue combination transcripts expressed at greater than 1 counts per million (cpm) in all six samples, and transcripts expressed at less than 1 cpm in all six samples, then compared identity across tissues to define sets of sex-specific and tissue-specific transcripts.

(c). Reproductive tissue and condition measures

We investigated whether sex-specific reproductive fitness measures differed between separate, recently outcrossed (see the electronic supplementary material) pure-breeding NW (n = 4) and FW (n = 3) lines derived from the same base population. At 7 days post-adult eclosion, gonad characteristics were measured in virgin male (n = 140; 18–21 per biological line) and female (n = 145; 19–24 per biological line) crickets that had been reared at standard stock densities. As proximate measures of reproductive output, we obtained wet mass of dissected testes to the nearest mg, and for females counted the number and measured the total wet mass in mg of eggs contained within the ovaries.

Testes mass was analysed using a linear mixed model (LMM), while female total egg mass was analysed using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a negative binomial distribution. Total egg mass followed a negative binomial distribution owing to the Poisson distribution of egg numbers. Both models included predictor variables of morph genotype, log pronotum length, log somatic mass and a random effect of biological line. We calculated somatic (i.e. not including gonad masses) scaled mass index (SMI) from pronotum length and somatic wet mass, often used as a proximate measure for individual body condition [38]. Log-transformed SMI was analysed using an LMM with predictor variables of morph genotype, sex, an interaction between the two and a random effect of biological line. Following the SMI comparison, contributions of differences in pronotum length and somatic wet mass were investigated using LMMs with the same predictors and random effect. Mixed models were run in the R package lme4 [39], with MASS used to fit the negative binomial GLMM. Significance of predictor terms was tested using Wald's χ2.

3. Results

(a). Morph genotype has larger effects on gene expression in females

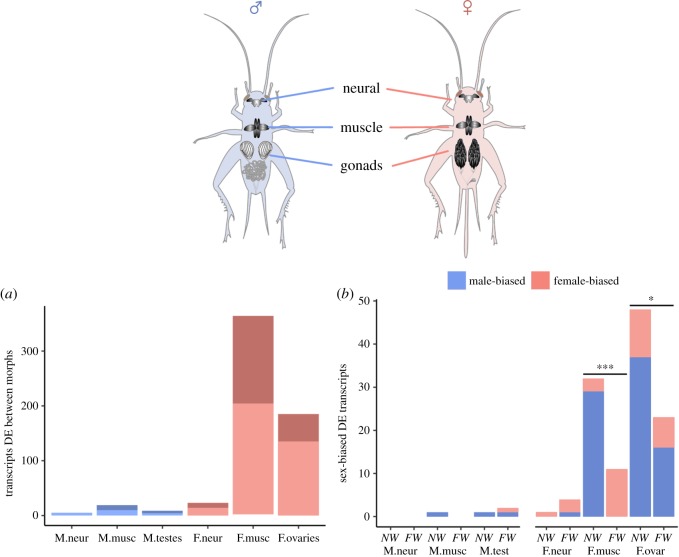

Female transcriptomes were more strongly impacted by carrying the flatwing genotype than were males'. The unfiltered T. oceanicus transcriptome contained complete sequences for 90.6% conserved insect BUSCO genes, with low duplication rates (1.8% of complete genes; see the electronic supplementary material), and 42 496 transcripts (Trinity-identified ‘genes’) passed filtering. Differential expression results are summarized in table 1. In all tissues, the number of DE transcripts (FDR < 0.01) associated with morph genotype was greater among females than males, and female thoracic muscle and ovaries were particularly strongly affected (neural tissue: , p < 0.001; thoracic muscle: , p < 0.001; gonads: , p < 0.001) (figure 2a). This interpretation remained unchanged if a fold-change of greater than 2 and FDR < 0.05 was instead adopted (greater DE in females: all p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Numbers of DE genes for contrasts examining sex-biased expression (top section) and morph genotype in each tissue and sex (middle and bottom section).

| tissue | DE_Downb | DE_Upb | DE_Sumb |

|---|---|---|---|

| sex (M)a | |||

| neural | 379 | 152 | 531 |

| muscle | 726 | 492 | 1218 |

| gonads | 9030 | 11 267 | 20 297 |

| male genotype (NW) | |||

| neural | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| muscle | 9 | 10 | 19 |

| testes | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| male total | 14 | 19 | 33 |

| female genotype (NW) | |||

| neural | 9 | 14 | 23 |

| muscle | 160 | 204 | 364 |

| ovaries | 50 | 135 | 185 |

| female total | 219 | 353 | 572 |

aReference group for each contrast is given in parentheses: M, males; NW, normal-wing.

bAll DE inferred using FDR < 0.01.

Figure 2.

The flatwing genotype's effect on gene expression. The top panel shows tissues sampled. (a) Numbers of transcripts upregulated in NW-carrying crickets for males (light blue) and females (light red), versus upregulated in FW-carrying individuals of either sex (dark blue/red). (b) Sex-biased genes that differed between female morph genotypes showed patterns of demasculinization in FW females. (Too few sex-biased genes were DE between male genotypes for statistical comparison.) Numbers of sex-biased transcripts upregulated in each morph genotype with respect to the other are plotted, and colours show female-biased (red) versus male-biased (blue) expression. Significance (***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05) is shown for differences between genotypes in the number of transcripts showing masculinized/demasculinized expression. Significance was not tested for neural tissue, in which just five sex-biased transcripts were DE between genotypes. (Online version in colour.)

Of 560 unique transcripts DE between genotypes in either sex, 296 (52.86%) had significant BLASTX hits. None of the annotated transcripts had obvious known functions or GO terms related to sexual dimorphism in insects. Over-represented GO terms among transcripts upregulated in each of the female genotypes are given in the electronic supplementary material, table S1. Neither male morph showed significant over-representation for any GO categories.

(b). Male trait loss is associated with demasculinized female gene expression

FW females showed demasculinized gene expression compared with NW females (figure 2b). Of the 119 sex-biased transcripts DE between female genotypes across all tissues, 87 (73.11%) showed expression patterns consistent with demasculinization of FW females (either female-biased transcripts upregulated in FW females or male-biased transcripts upregulated in NW females), compared with only 32 transcripts (26.89%) showing the reverse pattern (, p < 0.001). The pattern of demasculinization in FW relative to NW samples was consistent across female thoracic muscle and ovaries tissues (thoracic muscle: , p < 0.001; ovaries: , p = 0.044), but numbers were too low for quantitative comparison in neural tissues. Interpretation of demasculinized expression remained unchanged under fold-change > 2 and FDR < 0.05 criteria (neural tissue: too few for comparison; thoracic muscle: , p < 0.001; ovaries: , p = 0.015).

(c). Magnitude of differential expression associated with male trait loss across sexes and tissues

For transcripts DE between genotypes in one or both sexes, changes in gene expression were positively correlated between sexes in neural (Spearman's rank: r = 0.920, n = 26, p < 0.001) and gonad (r = 0.203, n = 193, p = 0.005) tissues, but not in thoracic muscle (r = 0.046, n = 378, p = 0.372) (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Across the 19 transcripts showing concordant and significant DE in males and females, after relaxing the significance threshold to FDR < 0.05 to increase sample size, there was no indication that females showed greater log-fold changes; male genotypes tended to exhibit greater differences (male log2-fold change–female log2-fold change: average = 0.386, p = 0.123). Changes in expression associated with the FW genotype were concordant in pairwise comparisons across tissues within each of the sexes (Spearman's rank: all r > 0.465, p < 0.01; electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2), suggesting a relatively high degree of pleiotropy [37]. Interpretations above were unchanged under fold-change > 2 and FDR < 0.05 criteria.

Transcripts showing sex-limited expression did not show substantial DE between genotypes. In ovaries, the female tissue which showed the greatest degree of sex-limited expression, sex-limited transcripts (expressed greater than 1 cpm in all ovaries samples and less than 1 cpm in all testes samples) tended to be under-represented among those DE between morph genotypes (11 of 185 DE transcripts sex-limited, versus 1782 of the 17 254 transcripts greater than 1 cpm in all six samples; , p = 0.067). No sex-limited transcripts were DE between morph genotypes in testes, or neural and thoracic muscle tissues of either sex.

Among transcripts showing tissue-specific expression within each sex (e.g. expressed at greater than 1 cpm in all female neural samples but less than 1 cpm in all female thoracic muscle and ovaries samples) fewer than expected were DE between morph genotypes in ovaries (7 out of 178 DE transcripts showed tissue-specific expression, versus 1576 out of 17 254 of those expressed at greater than 1 cpm in all six samples; , p = 0.023). No tissue-specific transcripts were DE between genotypes in any of the other tissues; including testes, despite the large number of tissue-specific transcripts (0 out of 9 versus 6658 out of 20 998). In somatic tissues, tissue-specific transcripts were less likely to show sex-bias than were non-tissue-specific transcripts also expressed at greater than 1 cpm in all six samples for the respective tissue (χ2: p < 0.001 in both tissues and sexes), but this pattern was reversed in ovaries, where tissue-specific transcripts were more likely to show sex-bias (χ2 = 26.763, p < 0.001). There was no difference in testes samples (χ2 = 0.300, p = 0.584).

(d). Sex and morph variation in reproductive tissues and condition

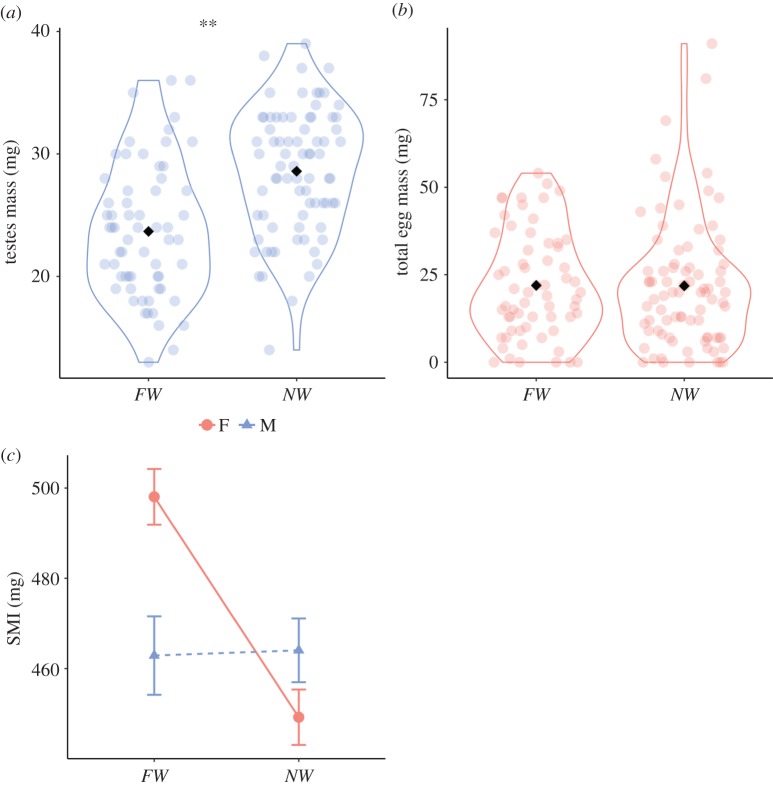

Adult NW males grew larger testes (LMM: , p = 0.003; figure 3a), but there was no difference in the mass of eggs produced by females of either genotype (GLMM: , p = 0.916; figure 3b; electronic supplementary material, table S2). Nevertheless, FW females achieved better condition. Their SMI was greater than that of NW females, but a significant sex × morph interaction (LMM: , p < 0.001) indicated there was no similar effect observed in males (figure 3c; electronic supplementary material, table S2). Thus, FW lines showed greater divergence in SMI between sexes, and this effect appeared largely related to changes in mass (electronic supplementary material, tables S2 and S3).

Figure 3.

Sex-specific differences in gonad phenotypes and body condition in FW versus NW genotypes. (a) Male testes mass and (b) female total egg mass, at 7 days post-eclosion. Black points illustrate means, and asterisks (**) indicate a significant difference at p < 0.01 (electronic supplementary material, table S2). (c) FW females showed increased SMI compared to NW females, but SMI did not differ between male genotypes. Points illustrate means, error bars ± s.e. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

Influential models of sexual selection and sexual conflict predict that sex differences in gene expression underlying sexually selected traits arise owing to IASC [7]. However, such resolution of IASC is often expected to be incomplete, and costly elaboration of sexual traits should eventually be checked by natural selection [20–22]. Surprisingly, we found that the naturally selected, genetic loss of a male sexual signal in crickets, via feminization of male wing structures, affected gene expression more strongly in adult females than in males. There was no evidence of feminization detectable in adult flatwing males, though this does not preclude such a role during earlier stages of development (e.g. [40]), which is hinted at by their reduced testes mass, and feminized CHCs [24]. By contrast, gene expression was demasculinized in female carriers of the flatwing genotype, which also showed increased body condition. These results support our predictions under a scenario of relaxed IASC following male sexual trait loss (figure 1).

Sex-biased gene expression is likely to be associated with underlying IASC at loci where selection pressures differ between males and females [4,6], and sexual ornaments provide a clear example of a trait with contrasting fitness optima between sexes [13]. The association between sexually selected traits and sexual conflict has frequently been inferred by comparing laboratory lines reared under contrasting selection regimes [19,27,41–43]. In T. oceanicus, our results raise the intriguing possibility that relaxed IASC among females accompanied evolutionary loss of a male sexual trait in the wild. Female release from IASC could occur more widely than is generally considered, given repeated secondary losses of sexually selected male traits across taxonomic groups [28,44–46], and could even facilitate these losses given the arms race-like dynamics with which IASC is frequently associated [47].

Recent evidence suggests increased sexually dimorphic gene expression is associated with increased fitness [15]. We therefore expected males and females from flatwing lines to show contrasting fitness effects of the mutant genotype, with females benefitting from demasculinized gene expression and males showing no variation. Flatwing males exhibited reduced testes mass, consistent with a previous report [48], but females carrying the flatwing genotype did not differ in reproductive output. Instead, they exhibited increased SMI, a proximate measure of body condition, whereas flatwing males showed no such increase. While we are cautious about making direct inference about fitness effects of SMI, evidence of IASC over body size in species as diverse as humans [49] and Indian meal moths Plodia interpunctella [50], illustrates that males and females are frequently subject to contrasting optima for mass and structural size. In T. oceanicus, structural body size is likely to have an important influence on male mating success through male–male competition and female choice, while females less subject to pressures of sexual selection may benefit from maximizing energy reserves [51]. Phenotypic evidence suggests, therefore, that flatwing males are disadvantaged above and beyond their inability to signal, whereas female flatwing carriers are not strongly disadvantaged, and may actually benefit, potentially as a result of relaxed IASC.

While demasculinized gene expression and increased body condition in flatwing-carrying females support a hypothesis of relaxed IASC following male sexual trait loss, several caveats are worth considering. For example, demasculinized expression does not itself illustrate female benefit, though this interpretation is supported by the increased body condition observed, which may or may not be directly related to demasculinized gene expression, and by others' findings of an association between greater sex-biased gene expression and fitness-associated traits [15]. Additionally, while our focus was on sex-biased transcripts, genotype also affected many transcripts in both sexes which did not show sex-bias. It is difficult to make inferences about the importance of these changes, or relate them to phenotypic traits, however it would affect interpretation of female benefit from carrying the FW genotype if, for example, changes to non-sex-biased transcripts had contrasting fitness-associated effects [52]. Finally, we examined differences between pure-breeding lines derived from a single wild population, but interpretation of our results would benefit from future work testing patterns of sex-specific selection across lines derived from wild populations with contrasting proportions of flatwing/normal-wing male phenotypes, to assess whether this influences IASC on a population level [18].

Comparing gene expression profiles across tissues within each sex revealed a strong pattern for transcripts differentially expressed between morphs in one tissue to show evidence of concordant differences in others. A lack of tissue-specificity is often used as a proxy measure for pleiotropy (i.e. more pleiotropic loci are likely to be less tissue-specific) [37], and extensive pleiotropy is widely expected to constrain the rate of evolution owing to the reduced likelihood of a net increase in fitness [53]. We found that very few transcripts showing tissue-specific or sex-limited expression differed in expression between genotypes. This supports the view that changes we observe to be associated with carrying flatwing are primarily among transcripts that have detectable levels of expression in both sexes, across tissues, and represent spillover effects of the flatwing locus in non-wing tissues. As well as showing flatwing has pervasive pleiotropic effects across multiple tissues, these results are consistent with the idea that the adaptive benefit of the flatwing phenotype in males outweighs costs associated with pleiotropic effects in non-focal tissues. Given the observed demasculinization of female transcriptomes, and evidence for increased female body condition, our results also raise the intriguing prospect that positive pleiotropic effects of flatwing on females through relaxed IASC could actually have facilitated its rapid spread.

5. Conclusion

Our results are consistent with theoretical expectations for relaxed genomic conflict following reduction of sexual selection [10]. The relaxation of genomic conflict may be an underappreciated yet capacitating feature of the widely observed loss of sexual ornaments, for which the genetic and evolutionary mechanisms are not well understood [28]. It is generally expected that the maintenance of sexually selected ornaments will be associated with IASC, and also acted against to varying degrees by natural selection. In T. oceanicus, the evolutionary loss of a male-specific sexual ornament may reduce IASC-associated constraints upon female gene expression, supporting the view that sex-biased gene expression only partially resolves underlying forces of IASC even when phenotypes are sex-limited in their expression [11,13]. More generally, IASC may be an underappreciated driver during the evolutionary reduction or loss of secondary sexual traits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to David Forbes for help with cricket rearing, and Xuan Liu, John Kenny, Nicola Rockliffe and staff at the Centre for Genomic Research in Liverpool, UK for library preparation and sequencing plus delivery of trimmed reads. Ramon Fallon provided valuable bioinformatic support, Michael G. Ritchie contributed helpful feedback about the interpretation of results, and Xiao Zhang provided useful remarks on an earlier version of the manuscript. Two reviewers and the Associate Editor provided further comments which greatly improved our manuscript.

Data accessibility

Trimmed reads for each library are available at the European Nucleotide Archive under accession PRJEB27211, and phenotypic data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5421j87 [54].

Authors' contributions

J.G.R., S.P. and N.W.B. designed experiments; J.G.R. and S.P. performed experiments, J.G.R. and N.W.B. analysed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript and agree to be held accountable for its content.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

Bioinformatic analyses were supported by the University of St Andrew Bioinformatics Unit (Wellcome Trust ISSF award 105621/Z/14/Z). This work was supported by funding to N.W.B. from the UK Natural Environment Research Council which is gratefully acknowledged (NE/I027800/1, NE/G014906/1, NE/L011255/1).

References

- 1.Connallon T, Knowles LL. 2005. Intergenomic conflict revealed by patterns of sex-biased gene expression. Trends Gen. 21, 495–499. ( 10.1016/j.tig.2005.07.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellegren H, Parsch J. 2007. The evolution of sex-biased genes and sex-biased gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 689–698. ( 10.1038/nrg2167) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachtrog D, et al. 2014. Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoS Biol. 12, 1–13. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mank JE. 2017. The transcriptional architecture of phenotypic dimorphism. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0006 ( 10.1038/s41559-016-0006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lande R. 1980. Sexual dimorphism, sexual selection, and adaptation in polygenic characters. Evolution 34, 292–305. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04817.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pizarri T, Snook RR. 2003. Perspective: sexual conflict and sexual selection: chasing away paradigm shifts. Evolution 57, 1223–1236. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00331.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonduriansky R, Chenoweth SF. 2009. Intralocus sexual conflict. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 280–288. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2008.12.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison PW, Wright AE, Zimmer F, Dean R, Montgomery SH, Pointer MA, Mank JE. 2015. Sexual selection drives evolution and rapid turnover of male gene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4393–4398. ( 10.1073/pnas.1501339112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice WR, Chippindale AK. 2001. Intersexual ontogenetic conflict. J. Evol. Biol. 14, 685–693. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00319.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox RM, Calsbeek R. 2009. Sexually antagonistic selection, sexual dimorphism, and the resolution of intralocus sexual conflict. Am. Nat. 173, 176–187. ( 10.1086/595841) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connallon T, Cox RM, Calsbeek R. 2010. Fitness consequences of sex-specific selection. Evolution 64, 1671–1682. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00934.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger D, Berg EC, Widegren W, Arnqvist G, Maklakov AA. 2014. Multivariate intralocus sexual conflict in seed beetles. Evolution 68, 3457–3469. ( 10.1111/evo.12528) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harano T, Okada K, Nakayama S, Miyatake T, Hosken DJ. 2010. Intralocus sexual conflict unresolved by sex-limited trait expression. Curr. Biol. 20, 2036–2039. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng C, Kirkpatrick M. 2016. Sex-specific selection and sex-biased gene expression in humans and flies. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006170 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006170) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean R, Hammer C, Higham V, Dowling DK. 2018. Masculinization of gene expression is associated with male quality in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 72, 2736–2748. ( 10.1111/evo.13618) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pointer MA, Harrison PW, Wright AE, Mank JE. 2013. Masculinization of gene expression is associated with exaggeration of male sexual dimorphism. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003697 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003697) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuglik MT, Babik W, Prokop Z, Radwan J. 2014. Alternative reproductive tactics and sex-biased gene expression: the study of the bulb mite transcriptome. Ecol. Evol. 4, 623–632. ( 10.1002/ece3.965) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joag R, Stuglik M, Konczal M, Plesnar-Bielak A, Skrzynecka A, Babik W, Radwan J. 2016. Transcriptomics of intralocus sexual conflict: gene expression patterns in females change in response to selection on a male secondary sexual trait in the bulb mite. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 2351–2357. ( 10.1093/gbe/evw169) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plesnar-Bielak A, Skrzynecka AM, Miler K, Radwan J. 2014. Selection for alternative male reproductive tactics alters intralocus sexual conflict. Evolution 68, 2137–2144. ( 10.1111/evo.12409) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher RA. 1915. The evolution of sexual preference. Eugenics Rev. 7, 184–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lande R. 1981. Models of speciation by sexual selection on polygenic traits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3721–3725. ( 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3721) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirkpatrick M. 1982. Sexual selection and the evolution of female choice. Evolution 36, 1–12. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1982.tb05003.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuk M, Rotenberry JT, Tinghitella RM. 2006. Silent night: adaptive disappearance of a sexual signal in a parasitized population of field crickets. Biol. Lett. 2, 521–524. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0539) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascoal S, et al. 2018. Silent crickets reveal the genomic footprint of recent adaptive trait loss. bioRxiv . ( 10.1101/489526). [DOI]

- 25.Pascoal S, Liu X, Ly T, Fang Y, Rockliffe N, Paterson S, Shirran SL, Botting CH, Bailey NW. 2016. Rapid evolution and gene expression: a rapidly evolving Mendelian trait that silences field crickets has widespread effects on mRNA and protein expression. J. Evol. Biol. 29, 1234–1246. ( 10.1111/jeb.12865) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pascoal S, Liu X, Fang Y, Paterson S, Ritchie MG, Rockliffe N, Zuk M, Bailey NW. 2018. Increased socially mediated plasticity in gene expression accompanies rapid adaptive evolution. Ecol. Lett. 21, 546–556. ( 10.1111/ele.12920) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollis B, Houle D, Yan Z, Kawecki TJ, Keller L. 2014. Evolution under monogamy feminizes gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Comm. 5, 3482 ( 10.1038/ncomms4482) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiens JJ. 2001. Widespread loss of sexually selected traits: how the peacock lost its spots. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 517–523. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02217-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabherr MG, et al. 2011. Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. ( 10.1038/nbt.1883) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W, Godzik A. 2006. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22, 1658–1659. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. ( 10.1038/nmeth.1923) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li B, Dewey CN. 2011. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinf. 12, 323 ( 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. 2015. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Immonen E, Sayadi A, Bayram H, Arnqvist G. 2017. mating changes sexually dimorphic gene expression in the seed beetle Callosobruchus maculatus. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 677–699. ( 10.1093/gbe/evx029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conesa A, Götz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. 2005. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dean R, Mank JE. 2016. Tissue specificity and sex-specific regulatory variation permit the evolution of sex-biased gene expression. Am. Nat. 188, E74–E84. ( 10.1086/687526) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peig J, Green AJ. 2009. New perspectives for estimating body condition from mass/length data: the scaled mass index as an alternative method. Oikos 118, 1883–1891. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17643.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bates D, Martin M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. ( 10.18637/jss.v067.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perry JC, Harrison PW, Mank JE. 2014. The ontogeny and evolution of sex-biased gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 1206–1219. ( 10.1093/molbev/msu072) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rice WR. 1996. Sexually antagonistic male adaptation triggered by experimental arrest of female evolution. Nature 381, 232–234. ( 10.1038/381232a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holland B, Rice WR. 1999. Experimental removal of sexual selection reverses intersexual antagonistic coevolution and removes a reproductive load. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5083–5088. ( 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crudgington HS, Beckerman AP, Brüstle L, Green K, Snook RR. 2005. Experimental removal and elevation of sexual selection: does sexual selection generate manipulative males and resistant females? Am. Nat. 165, S72–S87. ( 10.1086/429353) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porter ML, Crandall KA. 2003. Lost along the way: the significance of evolution in reverse. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 541–547. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00244-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris MR, Moretz JA, Farley K, Nicoletto P. 2005. The role of sexual selection in the loss of sexually selected traits in the swordtail fish Xiphophorus continens. Anim. Behav. 69, 1415–1424. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.08.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ptacek MB, Childress MJ, Petersen JA, Tomasso AO. 2011. Phylogenetic evidence for the gain and loss of a sexually selected trait in sailfin mollies. ISRN Zool. 2011, 251925 ( 10.5402/2011/251925) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pennell TM, de Haas FJ, Morrow EH, van Doorn GS. 2016. Contrasting effects of intralocus sexual conflict on sexually antagonistic coevolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E978–E986. ( 10.1073/pnas.1514328113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey NW, Gray B, Zuk M. 2010. Acoustic experience shapes alternative mating tactics and reproductive investment in male field crickets. Curr. Biol. 20, 845–849. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.063) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stulp G, Kuijper B, Buunk AP, Pollet TV, Verhulst S. 2012. Intralocus sexual conflict over human height. Biol. Lett. 8, 976–978. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0590) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis Z, Wedell N, Hunt J. 2011. Evidence for strong intralocus sexual conflict in the Indian meal moth, Plodia interpunctella. Evolution 65, 2085–2097. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01267.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitman DW. 2008. The significance of body size in the Orthoptera: a review. J. Orthoptera Res. 17, 117–134. ( 10.1665/1082-6467-17.2.117) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chevillon C, Bourguet D, Rousset F, Pasteur N, Raymond M. 1997. Pleiotropy of adaptive changes in populations: comparisons among insecticide resistance genes in Culex pipiens. Genet. Res. 70, 195–204. ( 10.1017/S0016672397003029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orr HA. 2000. Adaptation and the cost of complexity. Evolution 54, 13–20. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00002.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rayner JG, Pascoal S, Bailey NW. 2019. Data from: Release from intralocus sexual conflict? Evolved loss of a male sexual trait demasculinizes female gene expression Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.5421j87) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Rayner JG, Pascoal S, Bailey NW. 2019. Data from: Release from intralocus sexual conflict? Evolved loss of a male sexual trait demasculinizes female gene expression Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.5421j87) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Trimmed reads for each library are available at the European Nucleotide Archive under accession PRJEB27211, and phenotypic data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5421j87 [54].