Abstract

Objectives

Physiological metabolic adaptations occur in the pregnant woman. These may persist postpartum and thereby contribute to an unfavourable cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk profile in parous women. The aim of the current study is to assess time-dependent changes of cardiometabolic health in parous women compared with nulliparous women.

Design and setting

We studied data of 2459 women who participated in the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease study, a population-based prospective longitudinal cohort for assessment of CVD and renal disease in the general population.

Participants

We selected women ≥40 years at the first visit, who reported no new pregnancies during the four follow-up visits. All women were categorised in parity groups, and stratified for age.

Outcome measures

We compared body mass index (BMI), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, blood pressure as continuous measurements and as clinical relevant CVD risk factors among parity groups over the course of 6 years using generalised estimating equation models adjusted for age.

Results

The BMI was significantly higher in women para 2 or more in all age categories: per child, the BMI was 0.6 kg/m2 higher. corresponding with 1.5–2.0 kg weight gain per child. HDL cholesterol was significantly lower in women para 2 or more aged 40–49 and 50–59 years: per child, the HDL cholesterol was up to 0.09 mmol/L lower. Blood pressure did not differ among parity groups in any of the age categories.

Conclusions

Higher parity is associated with higher BMI, lower HDL cholesterol and a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, which is constant over time. These findings warrant for prospective research assessing determinants of cardiometabolic health at earlier age to understand the role of pregnancy in the development of CVD in women.

Keywords: pregnancy, parity, cardiovascular risk factors, BMI, HDL cholesterol, hypertension

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This longitudinal cohort comprised a large, well-phenotyped cohort with uniform assessment of all measurements during a median follow-up of 6 years.

The generalised estimating equation analysis which was performed, allowed us to assess differences among groups over time, focusing on group effects.

Since parity itself was not assessed in this cohort, we used the number of children as a proxy for the number of childbirths.

Women para >2 were older, less often used oral contraceptives and more often used antihypertensive medication which might have resulted in a slightly different metabolic profile.

Age at first delivery, interpregnancy interval and lactation have not been assessed in this cohort and therefore, adjustment of the analyses for these factors was not possible.

Introduction

Pregnancy is associated with major alterations to the cardiovascular system and metabolic profile.1–4 Increases in weight, lipid levels, blood plasma volume and cardiac output are needed to maintain a healthy, physiological pregnancy. Postpartum, this maternal adaptation reverses to its prepregnancy state, although several changes, (eg, increased body weight and hypercholesterolaemia) may persist for several months or longer.5 Possibly, these persisting changes contribute to an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and an unfavourable cardiometabolic profile in parous women.6–8 The amount of gestational weight gain (GWG) affects postpartum weight retention.9 At long-term follow-up, excessive GWG is associated with an increased body mass index (BMI), up to a 3–4 kg/m2 21 years after pregnancy.10–12

Previous studies assessing the relation between parity and cardiometabolic health showed conflicting results and even the association between parity and obesity is questioned in some studies.13–16 Long-term effects have only scarcely been investigated and most studies had a follow-up of only 1–3 years postpartum.17 18 A recent large cross-sectional study among Hispanic women in the US demonstrated that multiparity (ie, more than four or more than six children) was associated with obesity, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and elevated fasting glucose, also after adjustment for sociodemographic and lifestyle factors.8 In addition, results from the cross-sectional Rotterdam study showed an lower HDL cholesterol and higher total cholesterol and glucose/insulin ratios with higher parity in Caucasian women at 70 years of age.6

Studies on the development of cardiovascular risk factors over time and the quantification of this effect per childbirth are conflicting. Some studies suggested a linear association between number of children and an unfavourable cardiometabolic profile, while others stated that only multiparity is associated with an increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.6–8 19 20

Some studies even showed a ‘J-shaped’ association in which women with two children had the lowest prevalence of coronary heart disease.6–8

The aim of the current study was to assess time-dependent changes of cardiometabolic health in parous women, stratified for number of children, as compared with nulliparous controls. This study was performed in a well-defined longitudinal prospective cohort study that primarily assessed development of CVD, albuminuria and renal disease.21

Methods

Participants

The Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease (PREVEND) study is a longitudinal cohort follow-up study for assessment of cardiovascular and renal disease in the general population. Details of this study have previously been published elsewhere.22 23 In summary, all inhabitants of the city of Groningen, the Netherlands, from 1997 to 1998 at age 28–75 years (n=85 421) were invited to participate. All that applied, filled out a questionnaire and collected a first-morning void urine sample. Pregnant women and subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus were excluded. The urinary albumin concentration was assessed in a total of 40 856 (47.8%) responders. A total of 6000 participants were enrolled out of 7768 subjects with a urinary albumin concentration ≥10 mg/L. In addition, 2592 participants were enrolled out of 3394 subjects with a urinary albumin concentration <10 mg/L. Thereby, the PREVEND study was enriched by subjects with an elevated albumin excretion.

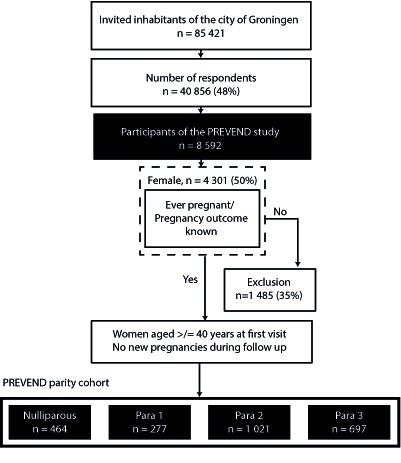

In total, 4301 women were enrolled in the PREVEND study (figure 1). For the current analysis, only women aged 40 years or older at the first visit and who reported no new pregnancies during the follow-up visits were included. Women who reported no children were categorised as nulliparous (n=464; 18.9%). Women who reported one child, two children or more than two children, were categorised as para 1 (n=277; 11.3%), para 2 (n=1021; 41.5%) and para >2 (n=697; 28.3%).

Figure 1.

Flowchart. PREVEND, Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease.

Patient and public involvement

No participants were involved with setting out the research question, developing the outcome measures or planning the study design. The results of study results will be disseminated by the newsletter and the study website.

Measurements and visits

Between 1997 and 2012, the screening visits took place every 2–4 years. Participants completed questionnaires and underwent physical examinations. Blood samples and 24 hours urine samples were taken. The questionnaires included questions regarding parity. Participants reported their number of children, which was used as a proxy for the number of childbirths. In addition, education level, current alcohol use and current smoking were assessed in these questionnaires. Details of clinical and laboratory measurements have previously been described elsewhere.22 Prescription data from pharmacies were used to assess the use of antihypertensive and lipid lowering medication. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg or the use of blood pressure lowering medication. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was defined as a fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L, random sample plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L, self-reported physician diagnosis of T2DM, and/or the use of glucose-lowering medication.24 Obesity was defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2.

Data selection for analyses was based on a fixed time interval of 6 years between the visits.

Statistical analysis

Data were arranged per patient per visit. Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as mean±SD and analysed using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey post hoc analysis. Continuous variables with a skewed distribution were expressed as median with 25th–75th percentile and analysed using Mann–Whitney U-test or Kruskall Wallis. Categorical variables were analysed using Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate.

For longitudinal assessment (time factor) of the outcome measures among the different parity groups (group factor), a generalised estimating equations (GEE) analysis was performed, including the interaction term group*visit (interaction factor). All analyses were performed using an autoregressive correlation matrix structure. This assumes a variable correlation between measurements depending on the time between measurements, as was expected in the current analysis. For GEE analyses of continuous dependent variables (BMI, HDL cholesterol and mean arterial pressure (MAP)), participants were further stratified in three age categories (40–49 years old, 50–59 years old and ≥60 years old). In addition, we performed a stepwise correction strategy, correcting for age (model 1), age and education (model 2), age and oral contraceptive use (model 3) and age, education and oral contraceptive use (model 4).

Data were analysed using SPSS V.22.0 (SPSS Inc.) and GraphPad prism V.5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California, USA). In all analyses, a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

Table 1 provides an overview of the baseline characteristics of women who were nulliparous, para 1, para t2 and para >2 at the first PREVEND visit. The mean age was significantly higher in women who were para >2. The majority of all women were Caucasian. The median follow-up time was 6 years in all groups. The cardiovascular risk profile among the parity groups differed significantly on BMI, blood pressure, smoking and use of alcohol. Unfavourable blood glucose measurements and cholesterol profiles were related to higher parity. The use of blood pressure lowering medication was higher in women who were para >2 compared with the other groups, but the use of glucose and lipid lowering medication did not differ among the groups. Women who were para >2 less often used oral contraceptives compared with women who were nulliparous, para 1 or para 2.

Table 1.

At entry table PREVEND stratified for parity

| No children (n=464)* |

One child (n=277)* |

Two children (n=1021)* |

More than two children (n=697)* | P value** | |

| General characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 52.2 (10.1) | 52.2 (9.0) | 52.3 (8.4) | 56.9 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up time (years) | 11 (11–12) | 11 (11–12) | 11 (11–12) | 11 (11–12) | 0.71 |

| Caucasian (n [%]) | 445 (96.9%) | 264 (96.4%) | 995 (98.0%) | 663 (95.7%) | 0.04 |

| Job (n [%]) | 315 (68.3%) | 127 (47.4%) | 467 (46.5%) | 264 (38.6%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular risk profile | |||||

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.6 (22.5–27.7) | 25.3 (22.5–28.6) | 25.8 (23.4–28.8) | 26.9 (24.0–30.2) | <0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 120 (109–138) | 121 (110–140) | 122 (111–138) | 130 (115–146) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 71 (65–78) | 71 (67–77) | 71 (66–78) | 73 (67–79) | 0.004 |

| Current smoker (n [%]) | 139 (30.0%) | 105 (37.9%) | 326 (31.9%) | 195 (28.0%) | 0.02 |

| Alcohol use (n [%]) | 203 (44.0%) | 137 (49.6%) | 503 (49.4%) | 378 (54.5%) | 0.007 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity (n [%]) | 11 (2.4%) | 11 (4.1%) | 24 (2.4%) | 24 (3.6%) | 0.30 |

| Renal disease requiring dialysis (n ([%]) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0.78 |

| Laboratory results | |||||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.6 (4.3–5.0) | 4.7 (4.3–5.1) | 4.7 (4.3–5.0) | 4.8 (4.4–5.2) | 0.002 |

| Insulin (mmol/L) | 7.0 (4.9–10.7) | 7.6 (5.1–11.5) | 7.8 (5.6–11.2) | 8.5 (6.0–13.4) | <0.001 |

| HOMAir | 1.4 (1.0–2.4) | 1.6 (1.0–2.5) | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) | 1.8 (1.2–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.7 (5.0–6.4) | 5.7 (5.1–6.5) | 5.8 (5.0–6.7) | 6.0 (5.3–6.7) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.0 (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 (0.9–1.7) | 1.1 (0.9–1.6) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | <0.001 |

| Medication use | |||||

| Total blood pressure lowering (n [%]) | 65 (16.4%) | 39 (16.5%) | 140 (15.6%) | 151 (24.4%) | <0.001 |

| ACEi/ARB (n [%]) | 19 (4.7%) | 8 (3.3%) | 41 (4.5%) | 44 (7.0%) | 0.07 |

| Glucose lowering (n [%]) | 7 (1.7%) | 2 (0.8%) | 12 (1.3%) | 12 (1.9%) | 0.63 |

| Lipid lowering (n [%]) | 19 (4.7%) | 15 (6.3%) | 32 (3.5%) | 37 (5.9%) | 0.11 |

| Oral contraceptive use ([n %]) | 79 (18.2%) | 50 (19.5%) | 198 (21.1%) | 90 (14.6%) | 0.01 |

Data are presented as median (25th–75th percentile) unless otherwise stated.

*Total number that participated at visit 1 of the study, not all variables were available for each participant at baseline.

**Significant at p <0.05

ACEi/ARB, ACE inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMAir, homeostatic model assessment index; PREVEND, Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Cardiometabolic profile in relation to parity and age

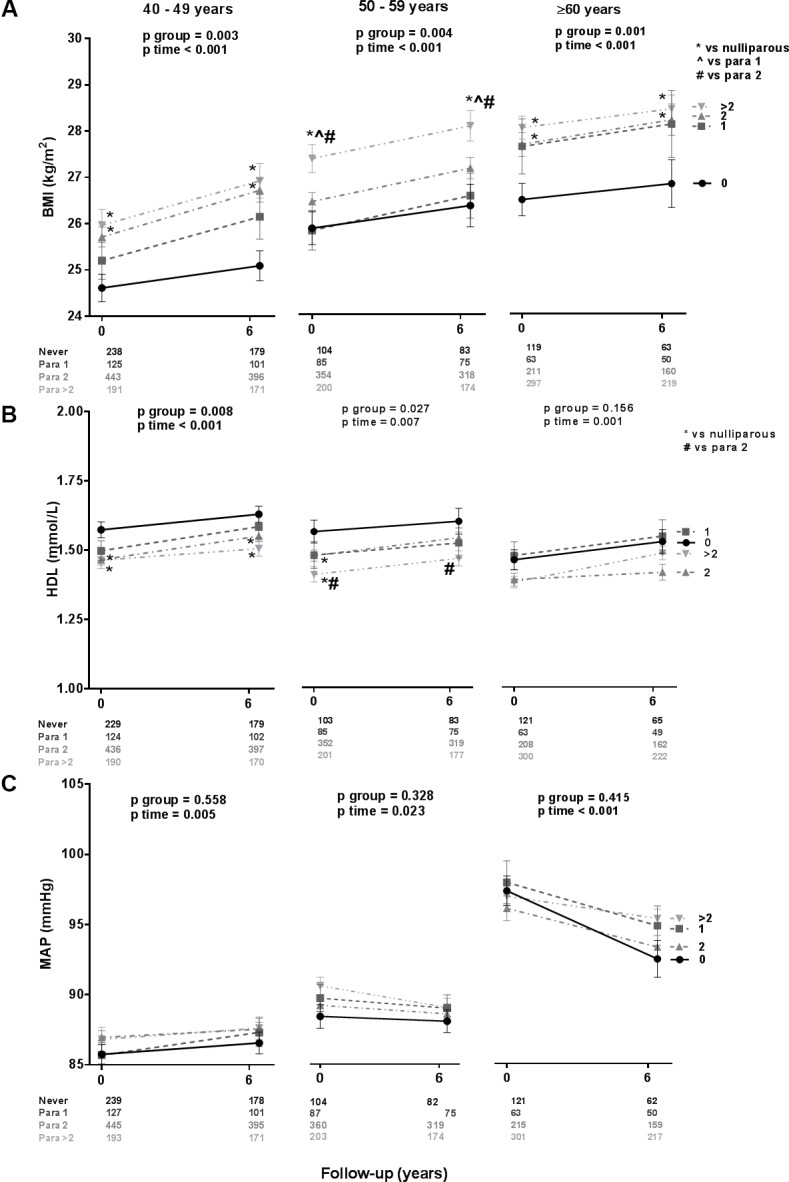

During the 6-year study period, there was a constant, significant difference in BMI among the parity groups at all age categories (figure 2A). The BMI was higher with every increase of parity at all age categories: per child, the BMI was 0.6 kg/m2 higher, equal to 1.5–2.0 kg. In women para >2, the BMI was 0.7–2.0 kg/m2 higher compared with the other parity groups. Over time, BMI increased significantly in all age groups (ptime<0.001), the change in BMI over time was similar among all parity groups (pinteraction=0.662–0.947). In a stepwise correction model, correction for age alone and correction for age and oral contraceptive use did not influence the differences in BMI among parity groups at all age categories (see online supplementary table 1). After correction for age, education level and oral contraceptive use, differences among parity groups were statistically significant at age 50–59 and >60 years only.

Figure 2.

Development over time of BMI (A), HDL cholesterol (B) and MAP (C), stratified for parity. BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

bmjopen-2018-024279supp001.pdf (92.5KB, pdf)

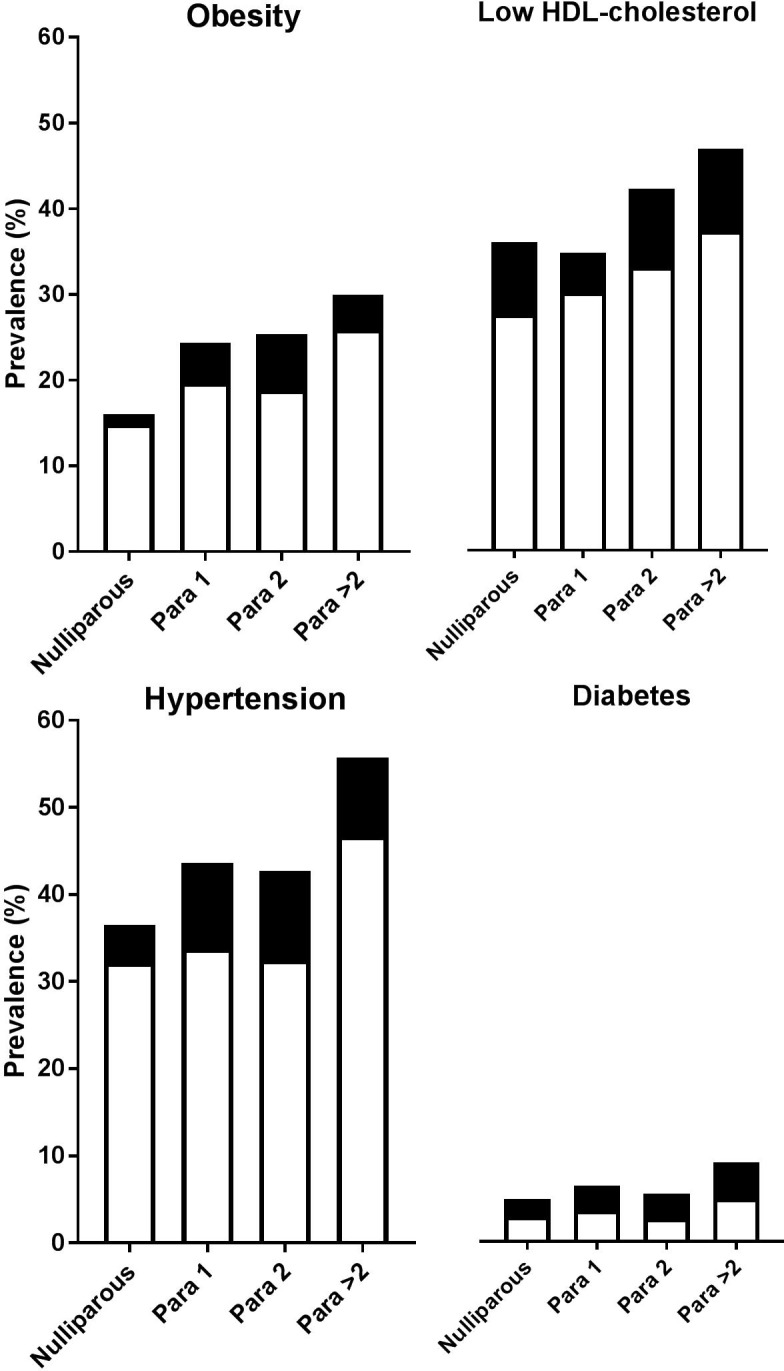

The prevalence of obesity increased with increasing parity at entry (pfor trend<0.001) and at 6-year follow-up (pfor trend<0.001; figure 3). At visit 1, 15% of the nulliparous women was obese, compared with 26% of the women para >2. After the course of 6 years, this was increased to 16% of the nulliparous women compared with 30% of the para >2. The increase in prevalence over time was similar among the groups (p=0.450). In a stepwise correction model, correction for age alone and correction for age and oral contraceptive use did not influence the differences in HDL cholesterol among parity groups at all age categories (see online supplementary table 1). After correction for age, education level and oral contraceptive use, differences among parity groups were not statistically significant anymore at all age groups.

Figure 3.

CVD risk factors at entry. Hypertension=blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg and/or use of antihypertensive medication; Obesity=BMI ≥30 kg/m2; Low HDL cholesterol=HDL cholesterol<1.29 mmol/L; Diabetes=fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L, self-report of a physician diagnosis and/or use of glucose-lowering medication.  =first visit;

=first visit;  =follow up visit. BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

=follow up visit. BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

HDL cholesterol differed among the groups, except for participants aged ≥60 years (figure 2B). The HDL cholesterol was lower with every increase of parity, except for participants older than 60 years: per child, the HDL decreased with 0.05 mmol/L. Women para 2 and women para >2 had significant lower HDL cholesterol at both measurements compared with nulliparous women aged 40–49 years (0.08–0.12 mmol/L) and 50–59 years (0.10–0.17 mmol/L). Over time, HDL cholesterol increased significantly in all age groups (ptime=0.001–0.007) and the change in HDL cholesterol over time was similar among all parity groups (pinteraction=0.163–0.530).

Low HDL cholesterol (<1.29 mmol/L) prevalence differed among the groups at visit 1 (pfor trend<0.001) and at follow-up visit (pfor trend=0.006); low HDL cholesterol was more common when parity increased (figure 3). Low HDL cholesterol prevalence inclined similar in all groups over time (p=0.160).

There were no differences among the parity groups over time in MAP at all ages, although MAP increased in all groups at age 40–49 years and 50–59 years and decreased in all groups at age ≥60 years (figure 2C). The change in MAP over time was similar among all parity groups (pinteraction=0.348–0.815). Prevalence of hypertension increased with parity both at entry visit (pfor trend<0.001) and at follow-up (pfor trend<0.001). Hypertension prevalence increased similar in all groups over time by 4%–10% (p=0.761; figure 3).

Occurrence of T2DM did not differ among the groups at entry (pfor trend=0.094), although a positive association was found between T2DM prevalence and parity after 6 years (pfor trend=0.018). The increase in T2DM over time was comparable at all groups (p=0.336). T2DM prevalence was <10% at all groups at both visits (figure 3).

Discussion

In this longitudinal cohort study, having two children or more was associated with a higher BMI in all age categories and with a lower HDL cholesterol, but not with changes in blood pressure. A higher parity was associated with higher prevalence of obesity, low HDL cholesterol and a higher prevalence of hypertension. These associations were constant over time. As analyses were stratified and/or adjusted for age, these results suggest a direct association of parity itself with BMI, HDL cholesterol levels and cardiovascular risk factor prevalence. Other factors attributing to parity, that is, education and oral contraceptive use, might have contributed to these differences and therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution.

Since BMI appears to be one of the most important cardiometabolic risk factors, the influence of parity on BMI is of great interest. This strong effect of BMI is due to the direct effect on CVD onset and due to its adverse effect on lipid profile and blood pressure.25–28 Results from a population-based cohort study among 4699 women suggested that weight or weight chances might be an important mediator in the effect of parity on MetS, thus confirming the importance of BMI in regard to cardiometabolic health.19 In our study, roughly each extra child is associated with 1.5–2.0 kg weight gain. Similar, each extra child is associated with 0.05 mmol/L decrease in HDL cholesterol, which might be the result of the increased BMI.

Specific BMI measures, HDL cholesterol levels and MAP measures differed among the three age groups. Because women from all different ages were seen throughout all screening visits, we expect this to be an effect of age itself, thereby reflecting the growing influence of age on cardiometabolic health with increasing age.

Parallel to these metabolic differences in continuous measurements among the groups, occurrence of several clinical relevant cardiovascular risk factors, such as obesity and hypertension, differed among the groups as well. This is in line with cross-sectional studies assessing metabolic profile in relation to the number of children.6–8 19 However, some studies could not confirm the relation between parity and metabolic health, especially after adjustment for covariates such as lifestyle.14 15 19 29 In the stepwise correction, we found no or minimal influence of age, age and education level or age and oral contraceptive use on our results. Only after full correction for age, education level and oral contraceptive use, the statistical significance among parity groups diminished. Consequently, our findings should be interpreted with caution, as these factors and others, such as lifestyle changes following childbirth, might influence cardiovascular health next to parity itself.29 Moreover, lifestyle effects of family life and the protective effect of lactation could explain the influence of parity on cardiometabolic health.30–32

Another possible explanation behind the mechanism of this relationship between parity and cardiovascular risk factors could be found in the effect of disturbances by pregnancy itself that continue to last postpartum. For example, breast feeding is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular risk factors, that is, T2DM, although the role of breast feeding remains controversial and a recent meta-analysis showed no significant effect of breastfeeding on postpartum weight retention.33–36 Other factors involved in the relationship between parity and cardiovascular risk factors might be found in circulation markers. An example might be found in the ovarian peptide hormone relaxin, produced by the corpus luteum or placental throughout pregnancy, has emerged as cardiovascular modulator involved in vasodilatation and inducing angiogenesis.37 38 Moreover, relaxin was positively associated with insulin sensitivity and lipid profile in women with T2DM as well.39

Previous cohort studies showed a ‘J-shaped’ association between parity and coronary heart disease, with lowest prevalence in women with two children, or stated that only multiparity (ie, more than four or five children) was associated with increased CVD risk.6–8 However, our results indicate a stepwise effect of parity on cardiometabolic health and having two children or more than two children already affects BMI, HDL cholesterol levels and cardiovascular risk factor prevalence.

Our paper is the first study providing detailed assessment of cardiometabolic health development over time in relation to parity. This longitudinal study comprised a large, well-phenotyped cohort with uniform assessment of all measurements during a median follow-up of 6 years. The GEE analysis which was performed, allowed us to assess differences among groups over time, focusing on group effects. However, several limitations need to be discussed. The mean age of women para >2 was significantly higher than women who were nulliparous, para 1 or para 2. In addition, women para >2 less often used oral contraceptives and more often used antihypertensive medication. This might result in a slightly different metabolic profile although correction of the GEE-analysis for age and oral contraceptive use did not significantly change the results. Despite extensive phenotyping, age at first delivery, interpregnancy interval and lactation have not been assessed in the PREVEND study and therefore, adjustment of the analyses for these factors was not possible. Since parity itself was not assessed in the PREVEND, we used the number of children as a proxy for the number of childbirths. This might lead to inaccurate estimates of parity numbers, as the possibility of surrogacy or twin pregnancies is not taken into account. Additionally, no information was available regarding subfertility and several pregnancy complications, which leads to a lower number of children in these women and might reflect influence the cardiometabolic profile in later life as well. More extensive information regarding socioeconomic status was not measured as well, thereby it was only possible to correct for education but not for other socioeconomic factors. Lastly, prepregnancy BMI and GWG have not been assessed in the PREVEND study either, although their role on postpartum weight retention seemed limited in a recent publication.9 18

The PREVEND study was enriched with subjects with an elevated albumin excretion, which mostly results in an unfavourable cardiovascular risk profile compared with the general population. However, albuminuria did not significantly differ among the groups within our analyses. Although our findings suggest an effect of parity itself on metabolic parameters, it should be noted that causality cannot be determined in our study. Therefore, one could argue that the relationship is reversed, for example, women with higher BMI or lower HDL cholesterol are more fertile and therefore have more children. Prospective research assessing prepregnancy determinants of cardiometabolic health are warranted to further assess the possible causal effect of pregnancy itself.

Conclusion

In this longitudinal cohort study, higher parity is associated with higher BMI and lower HDL cholesterol. This difference among parity groups is constant over time. Furthermore, higher parity is associated with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among the parity groups over time. These findings warrant for prospective research assessing determinants of cardiometabolic health at earlier age to understand the role of pregnancy and the influence of lifestyle factors in the development of CVD in women.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

BVR and TL contributed equally.

Contributors: GAZ, NDP, KG, RTG, HG and TL were involved in conception and design of the study. Data analyses were performed by GAZ, NDP, KG and HG. Interpretation of the results was performed by GAZ, NDP, KG, RTG, HG, AF, BVR and TL. GAZ, NDP, KG and TL drafted the manuscript. GAZ, NDP, KG, RTG, HG, AF, BVR and TL edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The PREVEND study was supported by Dutch Kidney Foundation (Grant E.033), The Groningen University Medical Center (Beleidsruimte) and Dade Behring, Ausam, Roche, Abbott and Gentian who financed laboratory equipment and reagents for various laboratory determinations. Gerbrand Zoet is supported by the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant number 2013T083). Titia Lely is supported by the ZonMW Clinical Fellowship (40-000703-97-12463).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The PREVEND study has been approved by the medical ethics committee of the University Medical Centre Groningen.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Patient level data and full dataset and technical appendix and statistical code are available from the corresponding author (gzoet@umcutrecht.nl).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Bartels Ä, O’Donoghue K. Cholesterol in pregnancy: a review of knowns and unknowns. Obstet Med 2011;4:147–51. 10.1258/om.2011.110003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tan EK, Tan EL. Alterations in physiology and anatomy during pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2013;27:791–802. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jebeile H, Mijatovic J, Louie JCY, et al. A systematic review and metaanalysis of energy intake and weight gain in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:465–83. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Haas S, Ghossein-Doha C, van Kuijk SM, et al. Physiological adaptation of maternal plasma volume during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;49:177–87. 10.1002/uog.17360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berge LN, Arnesen E, Forsdahl A. Pregnancy related changes in some cardiovascular risk factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1996;75:439–42. 10.3109/00016349609033350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Humphries KH, Westendorp IC, Bots ML, et al. Parity and carotid artery atherosclerosis in elderly women: The Rotterdam Study. Stroke 2001;32:2259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawlor DA, Emberson JR, Ebrahim S, et al. Is the association between parity and coronary heart disease due to biological effects of pregnancy or adverse lifestyle risk factors associated with child-rearing? Findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study and the British Regional Heart Study. Circulation 2003;107:1260–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vladutiu CJ, Siega-Riz AM, Sotres-Alvarez D, et al. Parity and components of the metabolic syndrome among US Hispanic/Latina women: results from the hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2016;9(2 Suppl 1):S62–S69. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rong K, Yu K, Han X, et al. Pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:2172–82. 10.1017/S1368980014002523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amorim AR, Rössner S, Neovius M, et al. Does excess pregnancy weight gain constitute a major risk for increasing long-term BMI? Obesity 2007;15:1278–86. 10.1038/oby.2007.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mamun AA. Associations of excess weight gain during pregnancy with long-term maternal obesity, hypertension and diabetes: Evidence from 21 years postpartum follow-up. Obes Rev 2010;11:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fraser A, Tilling K, Macdonald-Wallis C, et al. Associations of gestational weight gain with maternal body mass index, waist circumference, and blood pressure measured 16 y after pregnancy: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:1285–92. 10.3945/ajcn.110.008326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Steenland K, Lally C, Thun M. Parity and coronary heart disease among women in the American Cancer Society CPS II population. Epidemiology 1996;7:641–3. 10.1097/00001648-199611000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Kleijn MJ, van der Schouw YT, van der Graaf Y. Reproductive history and cardiovascular disease risk in postmenopausal women: a review of the literature. Maturitas 1999;33:7–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chung E, Kim Y, Usen O. Associations between parity, obesity, and cardiovascular risk factors among middle-aged women. J Womens Health 2016;25:818–25. 10.1089/jwh.2015.5581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robinson WR, Cheng MM, Hoggatt KJ, et al. Childbearing is not associated with young women’s long-term obesity risk. Obesity 2014;22:1126–32. 10.1002/oby.20593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schmitt NM, Nicholson WK, Schmitt J. The association of pregnancy and the development of obesity - results of a systematic review and meta-analysis on the natural history of postpartum weight retention. Int J Obes 2007;31:1642–51. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nehring I, Schmoll S, Beyerlein A, et al. Gestational weight gain and long-term postpartum weight retention: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1225–31. 10.3945/ajcn.111.015289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen A, Pieper CF, Brown AJ, et al. Number of children and risk of metabolic syndrome in women. J Womens Health 2006;15:763–73. 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ness RB, Harris T, Cobb J, et al. Number of pregnancies and the subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1528–33. 10.1056/NEJM199305273282104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pinto-Sietsma SJ, Mulder J, Janssen WM, et al. Smoking is related to albuminuria and abnormal renal function in nondiabetic persons. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:585–91. 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hillege HL, Janssen WM, Bak AA, a Baa, et al. Microalbuminuria is common, also in a nondiabetic, nonhypertensive population, and an independent indicator of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular morbidity. J Intern Med 2001;249:519–26. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joosten MM, Gansevoort RT, Mukamal KJ, et al. Urinary and plasma magnesium and risk of ischemic heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:1299–306. 10.3945/ajcn.112.054114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abbasi A, Corpeleijn E, Gansevoort RT, et al. Role of HDL cholesterol and estimates of HDL particle composition in future development of type 2 diabetes in the general population: the PREVEND study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:E1352–E1359. 10.1210/jc.2013-1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lamon-Fava S, Wilson PW, Schaefer EJ. Impact of body mass index on coronary heart disease risk factors in men and women. The Framingham Offspring Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996;16:1509–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Sullivan L, et al. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bogers R, Bemelmans W, Hoogenveen R, et al. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1720–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mongraw-Chaffin ML, Peters SAE, Huxley RR, et al. The sex-specific association between BMI and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 95 cohorts with 1·2 million participants. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:437–49. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00086-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hardy R, Lawlor DA, Black S, et al. Number of children and coronary heart disease risk factors in men and women from a British birth cohort. BJOG 2007;114:721–30. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01324.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gunderson EP, Jacobs DR, Chiang V, et al. Childbearing is associated with higher incidence of the metabolic syndrome among women of reproductive age controlling for measurements before pregnancy: the CARDIA study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:177.e1–177.e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McClure CK, Catov JM, Ness RB, et al. Lactation and maternal subclinical cardiovascular disease among premenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:46.e1–46.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Natland Fagerhaug T, Forsmo S, Jacobsen GW, et al. A prospective population-based cohort study of lactation and cardiovascular disease mortality: the HUNT study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1070 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baker JL, Gamborg M, Heitmann BL, et al. Sørensen TI a, Rasmussen KM. Breastfeeding reduces postpartum weight retention. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:1543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jarlenski MP, Bennett WL, Bleich SN, et al. Effects of breastfeeding on postpartum weight loss among U.S. women. Prev Med 2014;69:146–50. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Britz SE, McDermott KC, Pierce CB, et al. Changes in maternal weight 5–10 years after a first delivery. Womens Health 2012;8:513–9. 10.2217/WHE.12.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. He X, Zhu M, Hu C, et al. Breast-feeding and postpartum weight retention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:3308–16. 10.1017/S1368980015000828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sherwood OD. Relaxin’s physiological roles and other diverse actions. Endocr Rev 2004;25:205–34. 10.1210/er.2003-0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bani D. Relaxin as a natural agent for vascular health. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2008;4:515–24. 10.2147/VHRM.S2177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Szepietowska B, Gorska M, Szelachowska M. Plasma relaxin concentration is related to beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;79:e1–e3. 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024279supp001.pdf (92.5KB, pdf)