Abstract

Introduction

Managing nutrition is critical for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients on haemodialysis but adherence to the complex dietary restrictions remains problematic. Innovative interventions to enhance the delivery of nutritional care are needed. The aim of this phase II trial is to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a targeted mobile phone text messaging system to improve dietary and lifestyle behaviours in patients on long-term haemodialysis.

Methods and analysis

Single-blinded randomised controlled trial with 6 months of follow-up in 130 patients on haemodialysis who will be randomised to either standard care or KIDNEYTEXT. The KIDNEYTEXT intervention group will receive three text messages per week for 6 months. The text messages provide customised dietary information and advice based on renal dietary guidelines and general healthy eating dietary guidelines, and motivation and support to improve behaviours. The primary outcome is feasibility including recruitment rate, drop-out rate, adherence to renal dietary recommendations, participant satisfaction and a process evaluation using semistructured interviews with a subset of purposively sampled participants. Secondary and exploratory outcomes include a range of clinical and behavioural outcomes and a healthcare utilisation cost analysis will be undertaken.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee—Westmead. Results will be presented at scientific meetings and published in peer-reviewed publications.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12617001084370; Pre-results.

Keywords: dialysis, telemedicine, nutrition, dietary intervention

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Mobile phone technology is inexpensive and widely available, and has been found to be effective in improving clinical outcomes in some chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease.

This intervention will be evaluated in a randomised controlled study, with outcome assessors and statistician blinded to participant allocation.

The trial will be conducted in Australia and recruit participants from culturally diverse populations.

Dietary intake will be measured using patients’ self-report. Self-reported dietary intake may not accurately reflect an individual’s actual intake; however, we are using validated 24-hour dietary recall methodology to standardise dietary intake assessment and minimise bias.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is recognised as a global public health problem that affects ~13% of the population globally, and continues to increase.1 2 Compared with the general population, people with CKD have an increased risk of mortality from 1.2 times higher in those with mild dysfunction in early CKD to 5.9 times higher in patients on dialysis.2

In CKD, dietary management plays an important role in preventing the development and progression of CKD, improving clinical outcomes (eg, proteinuria, hypertension), reducing symptom burden and managing electrolyte abnormalities frequently seen in end-stage kidney disease, particularly in people requiring haemodialysis.3 Dietary management in patients on haemodialysis is particularly challenging because patients have to integrate complex and restrictive dietary requirements specific to CKD such as restricting protein, fluid, sodium, potassium and phosphorus. In addition, they may need to follow recommendations for comorbidities such as diabetes, as well as following general healthy eating principles.4 Furthermore, dietary prescription can vary substantially among patients depending on age, comorbidities and goals of treatment.5 In the haemodialysis population, educating patients about end-stage kidney disease fosters capacity for self-management and shared decision-making, which can in turn contribute to improved health-related behaviours (eg, diet, exercise and smoking cessation)6 and reduce burden on the healthcare system.

Patients and health professionals have identified lifestyle and nutrition as a high-priority research topic7 8 and is an important clinical management intervention that reduces symptom burden and acute medical events due to electrolyte abnormalities, as well as enhancing patients’ quality of life.9 However, dietary prescription on haemodialysis is often seen as restrictive and difficult for patients to adhere to.4 Patients have reported that one off didactic education sessions are overwhelming and difficult to comprehend, particularly at the time of diagnosis.4 Dietary-related behaviour change and self-management may be most effectively achieved through individualised education with a dietitian, frequent feedback and monitoring and longer duration of intervention (eg, at least 6 months).10 11 Patient-centred interventions that are individualised and provide progressively simple to more complex education over time to support and engage patients may help to improve outcomes in this population.

Electronic health interventions (eHealth) refers to ‘health services and information delivered or enhanced through the internet and related technologies’.12 eHealth interventions improve consumer access to relevant health information, enhances the quality of care and encourages the adoption of healthy behaviours.12 Globally, the use of technology is increasing; with a median of 87% of people regularly using the internet in high-income countries and a median of 54% of people regularly use the internet in developing countries.13 Australia has one of the highest rates of mobile phone ownership, with 88% of Australians owning a smart phone.14 Given this, there is increasing interest in the use of eHealth in healthcare. Systematic reviews have shown that eHealth interventions are effective in changing health-related behaviour and in improving outcomes in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease.15–19 Specifically, telehealth (ie, the use of telecommunication techniques to provide health education remotely)20 and mobile phone text messaging21 have shown positive improvements in dietary behaviours and clinical outcomes when compared with usual care in people with chronic diseases (eg, chronic lung disease, diabetes) and coronary heart disease, respectively.

There is a paucity of research using eHealth interventions, particularly interventions utilising mobile phone technologies, to target diet and lifestyle in the haemodialysis population.22 There is some indication that using electronic self-monitoring apps with additional dietary counselling may improve dietary sodium intake23 24 in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis populations; however, these studies were small and of short duration. In coronary heart disease, mobile phone text messaging has been shown to improve both dietary and clinical outcomes in patients, and to be well accepted, with >90% of participants reporting that the text messaging was useful and easy to understand.21 Given the complexity of dietary requirements in haemodialysis and the difficulty patients have in comprehending and integrating these requirements, text messaging offers an inexpensive and readily available way to motivate and help patients with managing their diet by providing frequent, short bursts of information over an extended period of time.

The aim of this study is to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of a mobile phone text message intervention to improve dietary and lifestyle behaviour in patients on haemodialysis. The results of this study will inform a larger trial.

Methods and analysis

Design

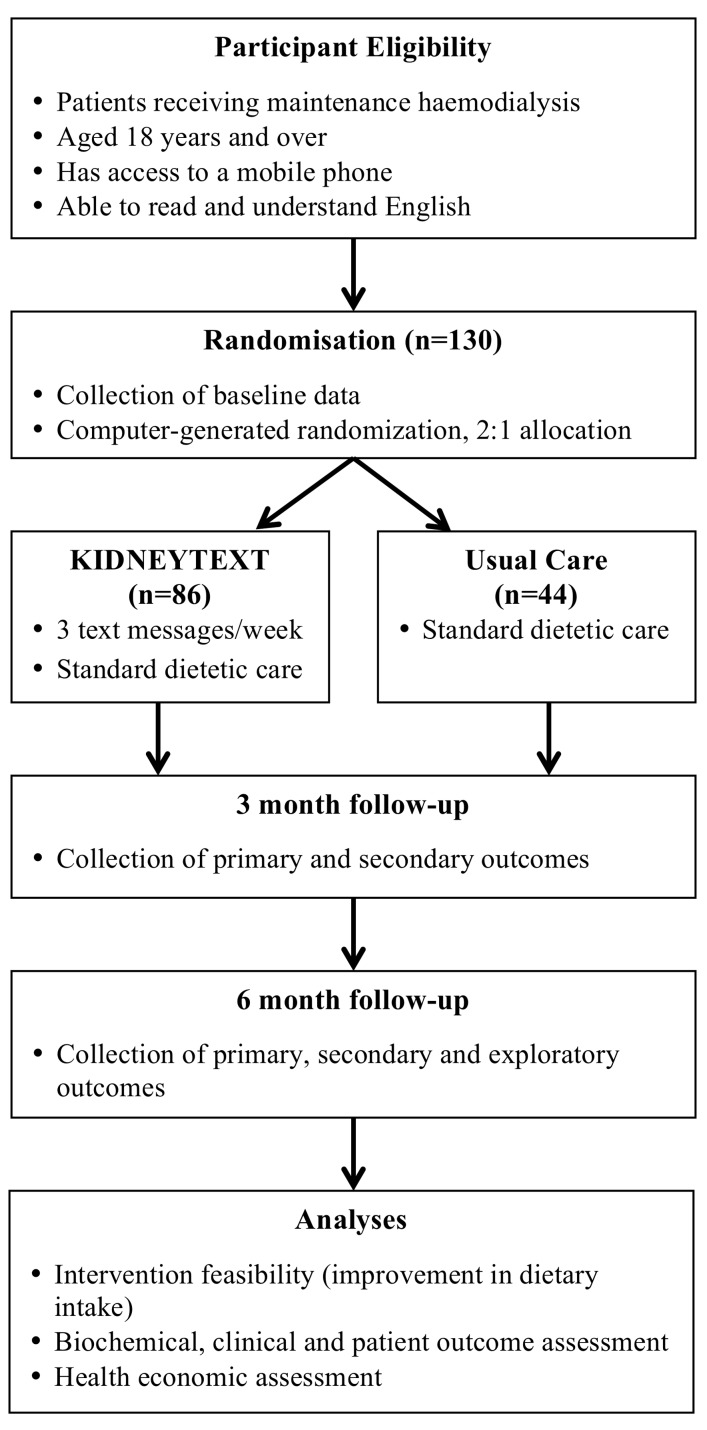

The design and development of KIDNEYTEXT has been underpinned by frameworks for the development of complex interventions25 and a range of behaviour change frameworks.26 KIDNEYTEXT is a 6-month single-blinded randomised controlled trial, with a 2:1 allocation ratio (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design and flow.

Study setting

This study will be conducted in six dialysis units across three local health districts in Sydney, Australia that serves ethnically, culturally and socioeconomically diverse populations.

Study population

A total of 130 patients receiving maintenance haemodialysis will be included. Patients receiving maintenance haemodialysis in the three local health districts in Sydney, Australia will be eligible to enrol in the study. Eligibility criteria include receiving maintenance haemodialysis for at least 90 days, aged 18 years and over, having sufficient English language skills to read and understand text messages and having access to a mobile phone throughout the duration of the study. If patients do not have their own mobile phone, a partner or close family member involved in meal provision may consent to have their mobile phone number used throughout the trial. Patients will be ineligible if they are prescribed a diet, that is, incongruent with standard renal dietary education (eg, immediately post bariatric surgery), acutely unwell (eg, septic), if they are not expected to be on haemodialysis for the forthcoming 6 months (eg, change of dialysis modality or transplantation), if they have a life expectancy of <12 months, pregnant or breastfeeding or if they have significant cognitive impairment or intellectual disability that would inhibit their understanding of the text messages. A ‘screening log’ containing basic demographic information and reason for non-participation will be kept for patients who are ineligible or decline to participate.

Interventions

Participants will be randomly allocated to either control or intervention group. The control group will continue to receive standard care provided by the dialysis unit that they attend. Standard care practices may differ between dialysis units; however, there will be no change to frequency of usual dietetic consultations or service delivery throughout the study.

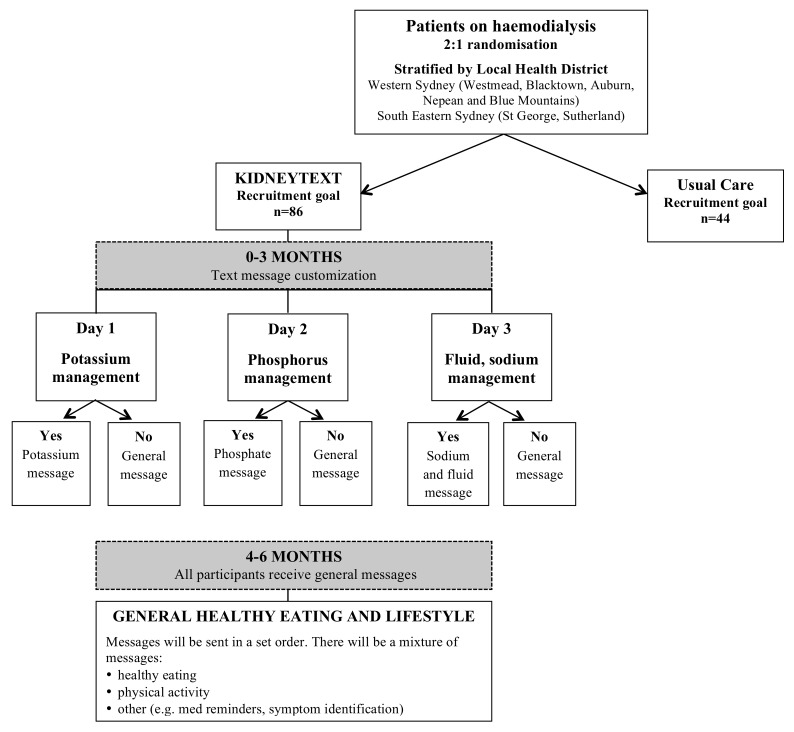

The KIDNEYTEXT intervention group will receive standard care plus they will receive three text messages per week over a 6-month period. Text messages will be unidirectionall (ie, one-way with no response required from participants), as they are intended to function as reminders and reinforcements of various dietary components. Unidirectional text messages have improved dietary and lifestyle behaviours in patients with coronary heart disease21 and are more time and cost-effective compared with in-person interventions. The messages will provide advice, information, motivation and support to improve renal dietary behaviours (related to potassium, phosphorus, sodium, fluid) and general healthy eating and lifestyle behaviours (box 1). From baseline to 3 months, patients may receive messages relating to dietary modification of potassium, phosphorus and sodium and fluid (figure 2). Participants will receive messages relating to potassium if one or both of the following guidelines is exceeded.

Baseline dietary intake exceeds guidelines for potassium (1 mmol/kg of ideal body weight per day).27

Two of three previous predialysis serum potassium levels exceeds 5.5 mmol/L.28 Baseline blood values will be based on the previous three routine dialysis blood tests.

Box 1. Examples of text messages to be sent to the KIDNEYTEXT intervention group.

Potassium

Did you know the way you cook your vegetables can change their potassium content? Boil vegetables in water to get rid of some potassium.

Not sure what is causing high potassium levels? Write down everything you are eating and drinking and discuss with your dietitian.

How much dairy do you have? Limit to 250 mL milk and milk products (eg, yoghurt and custard) daily to help control your potassium levels.

Phosphorus

Phosphate is added to prepackaged foods and convenience foods. Choose fresh foods to reduce how much phosphate you eat.

Phosphate binders act like a magnet and stop you from absorbing some phosphate. Take your phosphate binders with your meals so that they work properly.

Sodium and fluid

Make sure you know what is in your foods! Look for foods that contain <400 mg/100 g of sodium.

To get more flavour into your food use pepper, chilli, herbs and spices in your cooking.

Use smaller cups to help reduce how much you drink.

General healthy eating and lifestyle

Getting enough physical activity? Set regular goals to help you get to your target. Start small and build up over time. Every bit helps.

Include low potassium fruits and vegetables daily to make sure you get enough fibre.

Are you a bit off your food? Including small snacks can be a good way to keep up your nutrition.

The colour of vegetables gives a clue to what nutrients they contain. By including a variety of colours you will get more vitamins and nutrients.

Figure 2.

Text message allocation.

Participants will receive messages relating to phosphorus if one or both of the following guidelines is exceeded:

Baseline dietary intake exceeds guidelines for phosphorus (>1000 mg/day).27

Two of three previous predialysis serum phosphate levels exceeds 1.78 mmol/L.29 Baseline blood values will be based on the previous three routine dialysis blood tests.

Participants will receive messages relating to sodium and fluid if one or both of the following guidelines is exceeded:

Baseline dietary intake exceeds guidelines for sodium (>2300 mg/day).27

An average of interdialytic fluid gains from the previous three dialysis sessions being >3.5% of body weight or ≥3 kg.30

If a participant satisfies all of these guideline criteria they will only receive general healthy eating and lifestyle messages from baseline to 3 months.

From 4 to 6 months, all participants will receive general healthy eating and lifestyle messages that are congruent with renal dietary guidelines (figure 2). Feedback regarding participants’ biochemical and clinical parameters will continue to be provided as per the standard care of each dialysis unit (eg, via nursing and medical staff).

Message delivery will be managed by computerised software (TextQStream, Python V.3.6 using Pycap V.1.02 library) that was developed and customised in-house for use in this trial. Computer software is run through the University of Sydney RedCap system. The programme will keep a log of all messages sent to each participant. The messaging engine will send messages through a gateway interface that can be sent through Australian phone network at no cost to the participant. Data exports will be compliant with privacy legislation and held in strict privacy, centrally managed at Westmead Hospital. There will be no access to data by any third party, including the software developers.

While participants are asked not to respond to text messages, a record of any text messages received from participants will be kept and managed by a researcher who is not involved in recruitment or outcome assessment. Participants will have the opportunity to withdraw via a text message and the researcher will contact the software manager in order to initiate the withdrawal.

KIDNEYTEXT intervention development

In total, 160 text messages have been systematically developed through an iterative process and based on renal dietary recommendations27–30 and general healthy eating guidelines.31 Messages targeting renal-specific dietary components provide advice to assist participants in reducing their intake of potassium, phosphorus, sodium and fluid and provide prompts for self-monitoring and self-management behaviours. General healthy eating and lifestyle messages promote general healthy eating principles, such as increasing dietary fibre, encouraging physical activity and improving medication management.

The text message bank was developed in three stages. Initially, text messages were developed using behaviour change frameworks including information–motivational–behavioural skills model, theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behaviour and social cognitive theory.26 Table 1 outlines behaviour change techniques with examples of text messages used in KIDNEYTEXT.

Table 1.

Behavioural frameworks used to develop text messages

| Technique (theoretical framework) |

Definition | Examples |

| Provide information about behaviour link (information–motivational–behavioural skills model) |

General info re: behavioural risk (eg, susceptibility to poor health outcomes or mortality risk in relation to behaviour) | Look out for symptoms of high potassium levels. Nausea, tiredness, muscle weakness and an irregular heartbeat. Check your blood tests regularly. |

| Provide information on consequences (theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behaviour, social cognitive theory, information–motivational–behavioural skills model) |

Information about the benefits and costs of action or inaction, focusing on what will happen if the person does/does not perform the behaviour | Did you know that having a low or high potassium can cause a heart attack? Aim for a potassium level between 4 and 6 mmol/L. Having high blood phosphate levels for a long time causes your bones to become weak and fragile. To keep them strong follow a low phosphate diet. |

| Prompt intention formation (theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behaviour, social cognitive theory, information–motivational–behavioural skills model) |

Encouraging the person to decide to act or set a general goal (eg, make behavioural resolutions ‘I will exercise more this week’) | Getting enough physical activity? Set regular goals to help you get to your target. Start small and build up over time. Every bit helps. Get on the move! |

| Prompt barrier identification (social cognitive theory) |

Identify barriers to performing the behaviour and plan ways of overcoming them | A high salt diet will make you thirstier and harder to stick to your fluid restriction. Avoid adding salt to your meals and limit takeaways and processed foods. |

| Set graded tasks (social cognitive theory) |

Set easy tasks and increase difficulty until target behaviour is performed | Getting enough physical activity? Set regular goals to help you get to your target. Start small and build up over time. Every bit helps. Get on the move! |

| Provide instruction (social cognitive theory) |

Telling person how to perform a behaviour and/or preparatory behaviours | Did you know the way you cook your vegetables will change their potassium content? Boil vegetables in water to get rid of potassium. |

| Prompt self-monitoring of behaviour (control theory) |

Person is asked to keep a record of specified behaviours (eg, a diary) | Not sure what is causing high potassium levels? Write down everything you are eating and drinking and discuss with your dietitian. |

| Teach to use prompts/cues (operant conditioning) |

Teach person to identify environ cues which can be used to remind them to perform behaviour, including times of day, contexts | Having trouble sticking to your fluid restriction? Drink only out of a water bottle so you can measure how much you are drinking! |

| Relapse prevention (relapse prevention theory) |

Following initial change, help identify situations likely to result in readopting risk behaviours or failure to maintain new behaviours and help the person plan to avoid or manage these situations | Had a lapse in exercise? This is normal, but it is important to get back on track. Plan exercise into your day. Park your car further away or take the stairs. |

| Time management | Helping person make time for the behaviour (eg, to fit it into daily schedule) | Aim for 30 min of exercise most days. You can break your daily exercise into smaller 10–15 min blocks. |

Text message content was assessed for readability using Flesh-Kincaid, with an average Flesh-Kincaid score of 6 or less being deemed appropriate. An expert review panel including renal dietitians, nephrologists, renal nurses and social scientists then reviewed each message to ensure the content of the messages were accurate. The final draft of text messages were reviewed by people on haemodialysis, caregivers and public health researchers who rated the usefulness and understanding of the text messages on a five-point Likert scale with additional space for comments. Feedback from these ratings was incorporated into the final draft of text messages for the KIDNEYTEXT intervention.

Patient and public involvement

We sought feedback from people on haemodialysis during the design and development stages of KIDNEYTEXT. We conducted semistructured interviews with 35 patients on haemodialysis to elicit their perspectives regarding the use of eHealth, particularly mobile phone technology to support current nutritional management. Based on these interviews, three text messages per week were indicated as an acceptable frequency of receiving text messages. We incorporated feedback from these interviews into the design of KIDNEYTEXT. Once an initial bank of text messages was developed, we asked patients to review all message content for accuracy, relevancy and usability. Each message was reviewed by at least three consumers and we integrated their feedback into the final set of text messages for use in the trial. A process evaluation exploring the feasibility of the trial, including burdens and benefits to participants, will be undertaken at the completion of the trial. We will disseminate deidentified findings from the trial to study participants and dialysis units at the completion of the trial.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome will be the feasibility of the mobile phone text messaging intervention. Feasibility will be assessed as a composite outcome of recruitment rate, retention rate, adherence to renal dietary recommendations, participant satisfaction and changes in dietary knowledge, attitude and behaviours (box 2). Adherence to dietary recommendations will be defined as participants meeting three of the four dietary guideline recommendations with respect to protein, potassium, phosphorus and sodium (table 1). Dietary intake will be assessed by two dietitians blinded to participant allocation, using the validated 24-hour pass methodology.32 Dietary recalls will be conducted in-person, or if this is not possible, on the telephone with food models to assist with portion size estimations. Dietary intake will be assessed using a 24-hour recall, of both a dialysis day and a non-dialysis day, to ensure that we are capture any differences in dietary intake on these days. Dietary intake will be assessed at baseline, 3 months and 6 months, and will be taken assessed within 2 weeks a participant’s scheduled review. Dietary intake data will be analysed using Xyris Software Foodworks V.9 Pty (using food databases AUSNUT 2011–2013, Aus Foods 2017, Aus Brands 2017).

Box 2. Primary, secondary and exploratory outcome measures.

Primary outcome (measured at baseline, 3 months and 6 months)

Feasibility will be measured using:

-

Adherence to dietary recommendations. This will be measured using the 24-hour pass methodology to assess dietary intake with particular focus on renal dietary components: protein, potassium, phosphorous and sodium intake compared with renal dietary guideline recommendations. Adherence will be defined as meeting three of the four nutrition guidelines.

Dietary protein intake ≥1.2 g of protein per kilogram of ideal body weight per day.

Dietary potassium intake ≤1 mmol of potassium per kilogram of ideal body weight per day.

Dietary phosphate intake ≤1000 mg phosphorus per day.

Dietary sodium intake ≤2300 mg sodium per day.

Recruitment rate.

Drop-out rate.

Participant satisfaction (measured using a 7-point Likert scale).

Semistructured interviews to describe perspectives on participating in the trial, use of the intervention information, self-monitoring behaviours, decision-making, problem solving and behaviour change (only conducted in KIDNEYTEXT intervention group). Interviews will be conducted in-person or on the telephone within 8 weeks of completing the trial.

Secondary outcomes (measured at baseline, 3 months and 6 months)

Serum electrolytes (potassium, phosphate).

Interdialytic weight gains (average of the previous three haemodialysis sessions).

Changes in nutritional status as measured using the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment tool.

Change in quality of life scores measured using EQ-5D-5L.

Change in dietary quality measured using the Australian Healthy Eating Index.

The mean change in the intake of renal-specific dietary components across all time points.

Exploratory outcomes (measured at baseline and 6 months)

Blood pressure within recommended targets for patients on haemodialysis.

Serum parathyroid hormone, urea, bicarbonate, albumin levels.

Glycaemic control, measured using glycated haemoglobin levels (HbA1c) (subgroup analysis for patients with diabetes).

Healthcare utilisation.

After completion of the 6-month follow-up, a qualitative process evaluation33 will be undertaken using semistructured interviews conducted among a subset of 25–30 purposively sampled participants from the KIDNEYTEXT intervention group. Semistructured interviews will elicit participants’ perspectives regarding their satisfaction, acceptability and use of KIDNEYTEXT, and also their views and attitudes regarding changes in dietary behaviours, self-monitoring, decision-making and problem solving as a result of the KIDNEYTEXT intervention. With the consent of the participants, all interviews will be audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts will be entered in the computer software package ‘HyperRESEARCH V.3.0’ for storage, coding and searching of data. The audio recordings will be stored in a password-protected computer drive and hardcopy transcripts will be stored in a locked cabinet.

Secondary outcomes (outlined in table 1) will be assessed by two dietitians blinded to participant allocation, and include changes in serum potassium, serum phosphate, interdialytic weight gain, dietary quality and nutritional status. Dietary quality will be evaluated using the Australian Healthy Eating Index34 which uses seven parameters to assess the quality of a person’s diet. Nutritional status will be assessed using the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. Quality of life will be measured using the EQ-5D-5L instrument.35 The EQ-5D-5L is a standardised instrument for measuring generic health status using five dimensions of health rated on a five point scale and a rating of overall health status using a visual analogue scale. All secondary outcomes will be measured at baseline, 3 months and 6 months, except for nutritional status which will be assessed at baseline and 6 months only.

Additional exploratory outcomes will also be measured at baseline and 6 months and comparisons made between the control and the KIDNEYTEXT intervention groups. Exploratory outcomes will include biochemical parameters (urea, albumin, bicarbonate, parathyroid hormone, glycated haemoglobin), blood pressure (predialysis and postdialysis) and healthcare utilisation. Healthcare utilisation will be estimated from participant self-reported records of their healthcare-related appointments (including general practitioner, medical specialists and allied health) using a calendar supplied by the research team. Any hospital and emergency department admissions will be collected from medical records. Data relating to dialysis prescription (eg, dialysate composition, frequency and duration of dialysis) and dialysis-related medications (eg, prescription details of phosphate binders, resonium and diuretics) will be collected at baseline, 3 months and 6 months. The cost of implementation of the intervention, including cost of sending the text messages and software development, will be estimated.

An exploratory cost analysis from the perspective of the healthcare provider for the intervention compared with standard care, will be completed using costs estimated from the health service utilisation records and the cost of implementation of the intervention. The EQ-5D-5L scores will be used to calculate quality adjusted life years for the control and intervention groups. Although the main purpose is to determine the feasibility of collecting healthcare utilisation and QOL in this patient population, should the data be sufficiently robust, a preliminary calculation of an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio may be possible.

Randomisation

The random allocation sequence will be in a 2:1 (intervention:control) allocation ratio stratified by geographical location (Western Sydney, South Eastern Sydney). Randomisation will occur via a computerised randomisation programme that will be accessible by study staff with username and password through a web interface. Allocation will be concealed from study personnel undertaking assessments until the completion of the trial. Participants will be notified of their allocation via text message and will be asked not to disclose their allocation to study personnel.

Blinding

Blinded assessments will be conducted by two dietitians at baseline, 3 months and 6 months in face-to-face or telephone interviews. Prior to 3-month and 6-month reviews, participants will be sent a text message reminding them not to reveal their allocation to the outcome assessors. A statistician analysing data will also be blinded to participant allocation.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 129 participants, 86 in the intervention arm and 43 in the control arm, provide 80% power to detect an increase from 10% to 35% on adherence to dietary recommendations, with a significance level of 0.05. The analysis will follow an intention-to-treat principle. Balance across baseline characteristics (age, gender, haemodialysis type, dialysis vintage, dietary intake, biochemistry and interdialytic weight gains) will be checked. Continuous variables will be compared between groups using t-tests or Wilcoxon tests, according to their distribution. The χ2 test will be used to compare proportions. Logistic and linear mixed models will be used to analyse the longitudinal measurements of categorical and continuous outcomes, respectively. In particular, the interaction between time and group will allow for overall comparison between the two groups. Adjustment for unbalanced baseline characteristics will be considered in the analysis. A significance level of 5% will be used.

Safety and monitoring

If a participant is found to have a serum potassium level >6 mmol/L study personnel will alert dialysis staff. If a participant is commenced on a long-term (ie, longer than 1 month) dietary regime, that is, incongruent with standard renal dietary education (eg, immediately post bariatric surgery, total parenteral nutrition, complete enteral nutrition) during the study period the intervention will be ceased.

Ethics and dissemination

The findings of this study will be disseminated via scientific forums including peer-reviewed publications and presentations at international conferences. The study will be administered by the Westmead Clinical School, The University of Sydney, with the design and conduct overseen by a project management committee (authors). This committee has experience in large-scale clinical trials, qualitative research, health economics, renal medicine, renal dietetics and health policy implementation. Written and informed consent will be obtained from all participants.

Discussion

This study will evaluate a novel intervention to improve dietary behaviours in a haemodialysis population by using widely available and used mobile phone text messaging technology. Interventions using simple, inexpensive technology provide an opportunity to complement current dietary care and provide patients with more consistent support, particularly for those in resource poor settings and for those living in geographically isolated areas.

Rigorous studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of a mobile phone text message intervention targeting behaviour change in the haemodialysis population. No known studies have used mobile phone text messaging to improve dietary behaviours in a CKD or haemodialysis population; however, there is evidence that utilising mobile phone text messaging to improve dietary and clinical outcomes is feasible and effective in patients with coronary heart disease.21 36 37 Additionally, the content, level of individualisation, frequency and timing of text messages and level of interaction between healthcare professional and patient need to be determined. The current study will explore these important issues.

This KIDNEYTEXT trial will provide robust evidence about the feasibility of a targeted text messaging intervention to improve dietary behaviours and clinical outcomes in a haemodialysis population. Interventions to improve patients’ knowledge and motivation to alter their dietary behaviours in this population are needed to enhance patients’ quality of life and clinical care and are seen as a high priority for both patients and clinicians. This intervention has the potential as a cost-effective, readily accessible and simple method to improve patients’ dietary knowledge and behaviours.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All the authors acknowledge and are grateful for the support provided by Ms Adrienne Kirby, Dr Cindy Kok, Associate Professor Julie Redfern and Ms Caroline Wu at The University of Sydney. The authors thank those patients and renal clinicians who contributed to the design of KIDNEYTEXT.

Footnotes

Contributors: VWL, KLC, JC, AT and JS are the principle investigators who designed the study and drafted the manuscript. CC and AT made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the project. AT developed the software for use in the trial. CC, AT, KH, MH, MB, KS and RK have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. AT-P is in charge of the statistical analysis. KH and MH will lead the economic analysis. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: JS is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) PhD scholarship grant and NHMRC Better Evidence and Translation in Chronic Kidney Disease (BEAT-CKD) Program Grant (1092579). AT is supported by a NHMRC Fellowship (APP1106716). Funding for the trial was provided by a Sydney Medical School Foundation Grant and the Centre for Transplant and Renal Research at Westmead Hospital.

Competing interests: KS has received speaker’s honoraria from Baxter Healthcare, Roche, Amgen and Boehringer Ingelheim and conference or meeting sponsorships from Shire, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen, Sanofi and Novartis.

Ethics approval: Formal ethical approval for this study has been obtained by the Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (Westmead) approval number HREC/16/WMEAD/396 and will adhere to their guidelines for ethical human research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:137 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, et al. Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158765 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ash S, Campbell KL, Bogard J, et al. Nutrition prescription to achieve positive outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nutrients 2014;6:416–51. 10.3390/nu6010416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palmer SC, Hanson CS, Craig JC, et al. Dietary and fluid restrictions in CKD: a thematic synthesis of patient views from qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:559–73. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Tortorici AR, Chen JL, et al. Dietary restrictions in dialysis patients: is there anything left to eat? Semin Dial 2015;28:159–68. 10.1111/sdi.12348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fraser SD, Roderick PJ, Casey M, et al. Prevalence and associations of limited health literacy in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:129–37. 10.1093/ndt/gfs371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. KidneyHealthAustralia. Exploring research priorities in chronic kidney disease: a summary report. Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hemmelgarn BR, Pannu N, Ahmed SB, et al. Determining the research priorities for patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017;32:847–54. 10.1093/ndt/gfw065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stevenson J, Tong A, Campbell KL, et al. Perspectives of healthcare providers on the nutritional management of patients on haemodialysis in Australia: an interview study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020023 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karavetian M, de Vries N, Rizk R, et al. Dietary educational interventions for management of hyperphosphatemia in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 2014;72:471–82. 10.1111/nure.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Desroches S, Lapointe A, Ratté S, et al. Interventions to enhance adherence to dietary advice for preventing and managing chronic diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:Cd008722 10.1002/14651858.CD008722.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eysenbach G. What is e-health? J Med Internet Res 2001;3:e20 10.2196/jmir.3.2.e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pew CR. Smartphone Ownership and Internet Usage Continues to Climb in Emerging Economies. Washington DC, 2016. Available: http://www.pewglobal.org/2016/02/22/smartphone-ownership-and-internet-usage-continues-to-climb-in-emerging-economies/ [Google Scholar]

- 14. Australia D. Mobile Consumer Survey: The Australian Cut, 2017. Available: https://www2.deloitte.com/au/mobile-consumer-survey

- 15. Kitsiou S, Paré G, Jaana M, et al. Effectiveness of mHealth interventions for patients with diabetes: An overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173160 10.1371/journal.pone.0173160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pal K, Eastwood S, Michie S. Computer based diabetes self-management interventions for adults with type two diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2013;28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Widmer RJ, Collins NM, Collins CS, et al. Digital health interventions for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:469–80. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhai YK, Zhu WJ, Cai YL, et al. Clinical- and cost-effectiveness of telemedicine in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2014;93:e312 10.1097/MD.0000000000000312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sorgente A, Pietrabissa G, Manzoni GM, et al. Web-Based Interventions for Weight Loss or Weight Loss Maintenance in Overweight and Obese People: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e229 10.2196/jmir.6972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kelly JT, Reidlinger DP, Hoffmann TC, et al. Telehealth methods to deliver dietary interventions in adults with chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104:1693–702. 10.3945/ajcn.116.136333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chow CK, Redfern J, Hillis GS, et al. Effect of Lifestyle-Focused Text Messaging on Risk Factor Modification in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015;314:1255–63. 10.1001/jama.2015.10945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Diamantidis CJ, Becker S. Health information technology (IT) to improve the care of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). BMC Nephrol 2014;15:7 10.1186/1471-2369-15-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koprucki M, Piraino B, Bender F, et al. 162: RCT of Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) supported dietary intervention to reduce sodium intake in PD. Am J Kidney Dis 2010;55:B72 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.02.169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sevick MA, Piraino BM, St-Jules DE, et al. No Difference in Average Interdialytic Weight Gain Observed in a Randomized Trial With a Technology-Supported Behavioral Intervention to Reduce Dietary Sodium Intake in Adults Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis in the United States: Primary Outcomes of the BalanceWise Study. J Ren Nutr 2016;26:149–58. 10.1053/j.jrn.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379–87. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ash S, Campbell K, MacLaughlin H, et al. Evidence based practice guidelines for the nutritional management of chronic kidney disease. Nutr Diet 2006;63:S33–S45. 10.1111/j.1747-0080.2006.00100.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Putcha N, Allon M. Management of hyperkalemia in dialysis patients. Semin Dial 2007;20:431–9. 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;42(4 Suppl 3):S1–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cabrera C, Brunelli SM, Rosenbaum D, et al. A retrospective, longitudinal study estimating the association between interdialytic weight gain and cardiovascular events and death in hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol 2015;16:113 10.1186/s12882-015-0110-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. NHMRC. Australian Dietary Guidelines : Council NHaMR, (). Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raper N, Perloff B, Ingwersen L, et al. An overview of USDA’s Dietary Intake Data System. J Food Compost Anal 2004;17:545–55. 10.1016/j.jfca.2004.02.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Welfare AIoHa. Australian diet quality index project. Canberra, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chow CK, Redfern J, Thiagalingam A, et al. Design and rationale of the tobacco, exercise and diet messages (TEXT ME) trial of a text message-based intervention for ongoing prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with coronary disease: a randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000606 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Redfern J, Thiagalingam A, Jan S, et al. Development of a set of mobile phone text messages designed for prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:492–9. 10.1177/2047487312449416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.