Abstract

Background

foot problems are independent risk factors for falls in older people. Podiatrists diagnose and treat a wide range of problems affecting the feet, ankles and lower limbs. However, the effectiveness of podiatry interventions to prevent falls in older people is unknown. This systematic review examined podiatry interventions for falls prevention delivered in the community and in care homes.

Methods

systematic review and meta-analysis. We searched multiple electronic databases with no language restrictions. Randomised or quasi-randomised-controlled trials documenting podiatry interventions in older people (aged 60+) were included. Two reviewers independently applied selection criteria and assessed methodological quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. TiDieR guidelines guided data extraction and where suitable statistical summary data were available, we combined the selected outcome data in pooled meta-analyses.

Results

from 35,857 titles and 5,201 screened abstracts, nine studies involving 6,502 participants (range 40–3,727) met the inclusion criteria. Interventions were single component podiatry (two studies), multifaceted podiatry (three studies), or multifactorial involving other components and referral to podiatry component (four studies). Seven studies were conducted in the community and two in care homes. Quality assessment showed overall low risk for selection bias, but unclear or high risk of detection bias in 4/9 studies. Combining falls rate data showed significant effects for multifaceted podiatry interventions compared to usual care (falls rate ratio 0.77 [95% CI 0.61, 0.99]); and multifactorial interventions including podiatry (falls rate ratio: 0.73 [95% CI 0.54, 0.98]). Single component podiatry interventions demonstrated no significant effects on falls rate.

Conclusions

multifaceted podiatry interventions and multifactorial interventions involving referral to podiatry produce significant reductions in falls rate. The effect of multi-component podiatry interventions and of podiatry within multifactorial interventions in care homes is unknown and requires further trial data.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017068300.

Keywords: falls, podiatry, care homes, community dwelling, older people, systematic review

Key points

Podiatry interventions reduce falls in older people who live in their own homes.

Evidence is less clear for older people living in care homes.

Referral to podiatry services provides reductions in falls.

There is a strong case for trials of podiatry interventions to reduce falls in care homes.

Introduction

Falls are common among older people in both community and care home settings, leading to injury, fear, hospitalisation, loss of function and death [1, 2]. Annually, falls cost the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK more than £2 billion and in the USA, this figure is as high as $100 billion [3, 4]. To date, preventative interventions have typically included strengthening and balance exercises, medication review, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and detecting and treating visual impairment [5].

More recently, foot problems in older people [6, 7] have been shown to be associated with falls [8, 9]. Foot-related risk factors include foot pain, reduced ankle joint range of motion, hallux valgus deformity (bunion), and reduced toe plantar flexor muscle strength, while footwear-related risk factors include increased heel height, the absence of a strap, lace or other retaining medium and reduced sole contact area [8–11]. These factors have led to the development of podiatry interventions to reduce falls [12, 13]. Podiatrists improve mobility for patients by providing assessment, diagnosis and treatment of common and complex lower-limb pathology using a wide range of treatment modalities (manual debridement, surgical techniques, exercises, footwear and orthoses provision) [14].

Previous systematic reviews have shown encouraging effects of foot and ankle exercises alone on balance and falls. Furthermore, footwear and orthoses interventions have been shown to have a beneficial effect on balance only in community-dwelling older people [15, 16]. A systematic evaluation of multifaceted podiatry intervention packages (callus debridement, exercise, footwear, orthoses) on falls or falls rate has not been undertaken.

Older people living in care homes are around three times more likely to fall compared with those living in the community, therefore understanding effective ways to reduce falls in care homes is important [17]. Evidence for reducing care home falls remains equivocal [18] and other than footwear assessment, the effects of podiatry interventions on falls have not been evaluated in this setting.

The aim of this systematic review is to determine the effectiveness of podiatry interventions for falls reduction in older adults residing in the community and in care homes.

Methods

The review was conducted according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (v 5.10) [19] and reported using PRISMA statement guidance [20]. Methods with an explicit PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study-type) statement were pre-specified and documented in a protocol registered with PROSPERO, registration number CRD42017068300 [21].

Search strategy and selection criteria

Ten electronic databases (Medline, AMED, PeDRO, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CDSR, DARE, HTA and ZETOC) were searched for randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-RCTs published between inception and 18 July 2018.

No date or language restrictions were employed. An example search string is shown Appendix 1. Clinical trial registries (e.g. WHO ICTRP), grey literature (Google scholar, EThOS), podiatry-specific journals and reference lists of included studies were also searched. Forward citation tracking using Google Scholar was also employed to identify other potential studies.

RCTs or quasi-RCTs conducted with ambulatory adults (≥60 years), living in the community or in care home settings of any type were included. Interventions had to be delivered by podiatrists or staff trained in delivering podiatry interventions (for example, footwear provision, foot orthoses, toe exercises) to reduce pain, improve balance or preserve or improve foot health. Internationally, podiatry encompasses a wide range of techniques that could potentially be delivered by non-podiatrists so we were inclusive in our definition of podiatry-delivered interventions to include podiatry referral, footwear provision and orthosis provision. Foot and ankle exercises were included only in the context of a podiatry intervention, not as a primary falls prevention intervention [22].

Data collection and extraction

One reviewer (P.C.) examined searches and eliminated irrelevant titles. Two reviewers (C.T. and G.W.) independently screened remaining abstracts and full texts that met selection criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer (P.C. or H.F.) if required. Data was extracted to a standardised, pre-piloted form based on TIDieR reporting guidelines [23]. One reviewer extracted data (C.T.), another independently checked all data extraction (P.C. and G.W.). Missing information was requested from study authors.

Assessing methodological quality of included studies

Risk of bias was independently assessed by two reviewers (P.C. and C.T.). Studies were judged as either as ‘low risk’, ‘unclear’ or ‘high risk’ according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [19]. We considered the methodological quality for each study on the basis of the following categories: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, potential for attrition bias, potential for reporting bias and other potential bias [24]. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third review author where necessary.

Statistical analysis

Where suitable statistical summary data were available, we combined selected outcome data in pooled meta-analyses using the Cochrane statistical package RevMan [25]. Rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to examine falls rate. We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic with a value of greater than 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. Where we observed substantial heterogeneity, we used a random-effects model to pool the data and investigated the source of the heterogeneity. Where the value of the I2 statistic was less than 50% the data were pooled using a fixed-effect model.

Results

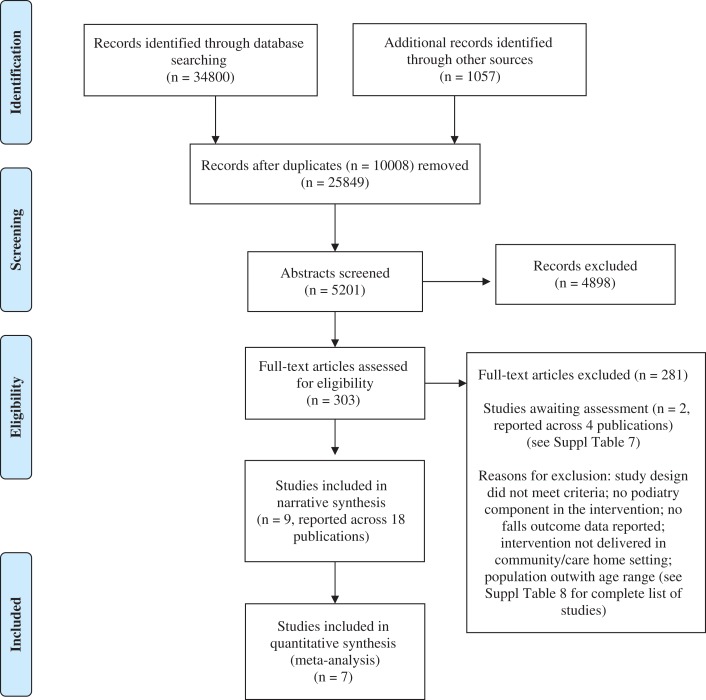

Our systematic search identified 35,857 records, of which 35,838 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were due to the study design not meeting the selection criteria or the intervention was not a podiatry intervention. A list of excluded studies can be found in Appendix 7. Nine studies (18 reports) were eligible for inclusion [12, 13, 26–32]. Two studies had insufficient detail to include in analyses and further details have been sought from the authors (see Appendix 8). Results of the study flow are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Included studies

Studies employed a number of different designs including: quasi-experimental (two studies), RCT (six studies) and cluster-RCT (one study). Table 1 summarises the key characteristics of the included studies. Additional details are available in Appendix 2. Studies were conducted in Australia, the USA, Canada, Spain, the UK and Ireland (Table 1). Seven trials were conducted in the community and in participants’ homes [12, 13, 26–29, 32]; two trials took place in care homes [30, 31].

Table 1.

Summary of key characteristics of included studies

Study

|

Participants and setting

|

Intervention (I)a

|

Comparison (C) | Primary outcomesb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SINGLE COMPONENT PODIATRY INTERVENTIONS | ||||

|

|

|

Podiatry treatment only | Foot Pain and Function (Foot Health Status—Pain Questionnaire) |

|

|

|

Conventional insole | Lateral stability (gait perubation protocol) |

| MULTIFACETED PODIATRY INTERVENTIONS | ||||

|

|

|

Routine podiatry care incl. treatment of pathological nails and skin lesions | Falls Rate (Falls Calendar) |

|

|

|

Routine podiatry care incl. treatment of pathological nails and skin lesions | Proportion of fallers/ Multiple fallers; Falls rate; Time to first fall (Falls Calendar) |

|

|

|

Routine podiatry care incl. treatment of pathological nails and skin lesions | No. of falls; Time to first fall (Accident Records); Feasibility (Recruitment, retention, adherence and missing data) |

| MULTIFACTORIAL INTERVENTIONS | ||||

|

|

|

None | Falls Rate/Recurrent Falls Rate (Falls Calendar) |

|

|

|

In-home assessment | Falls Rate (Falls diary/calendar) |

|

|

|

Routine healthcare | Falls Rate; Mean no. falls/year; No. multiple fallers |

|

|

|

Standard care as organised by ED staff | Falls Rate; Falls Injuries (Falls Calendar) |

Abbreviations: C—Control/ Comparator; ED—Emergency Department; F—female; I—Intervention; M—male; NR—not reported; SD—Standard Deviation; TC—telephone contact.

Key:aFurther intervention details profiled using TiDIER reporting guidelines [23] are shown in Supplementary Table S3, available at Age and Ageing online; bAdditional outcomes reported in Supplementary Table S2, available at Age and Ageing online. Explanation of falls outcomes: Number of fallers—Number of participants sustaining a fall; Falls incidence—number of falls; Falls rate—expressed as either the number of falls per person or with an additional time denominator; Time to first fall—falls free survival time.

Participants

The number of randomised participants (n = 6,502) ranged from 40 to 3,727 in each trial. The age of participants ranged between 69 and 87 years. Both sexes participated in each trial, the percentage of women (65.2%) taking part in the trials was higher than men. Six studies were conducted with people who had fallen or were at risk of falls, and three were conducted with participants who had existing health conditions such as peripheral sensory loss [26] and foot pain [13, 32] (Table 1).

Interventions

Three types of intervention were identified based on the falls taxonomy developed by Lamb et al. [33]:

Single component podiatry interventions (two studies, 167 participants) [26, 32], using insoles [26] or off-the-shelf footwear in addition to routine podiatry care [32].

Multifaceted podiatry interventions (three studies, 1,358 participants) [12, 13, 31]. A package of podiatry interventions was given to every participant and included routine podiatry, the provision of advice and information, footwear and/or orthoses if required and home-based foot and ankle exercises.

Multifactorial interventions (four studies, 4,984 participants) [27–30]. These were assessment and referral based and carried out by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT), all included a podiatry risk assessment and referral to podiatry. It is unclear if referral led to podiatry treatment or not.

Intervention details profiled using the TiDieR guidelines [23] are summarised in Appendix 3.

Of the nine studies, eight compared an ‘active’ intervention with usual care [12, 13, 27–32], and one with a sham insole [26]. The interventions were typically delivered by a podiatrist. In four trials, a podiatrist facilitated the intervention as part of a wider MDT delivering the intervention (Appendix 3). There was limited information about intervention content, dose or frequency. The length of the intervention period ranged from 12 weeks [26, 30, 31] to 104 weeks [28] (Table 1). Assessment of intervention fidelity regarding referral, participant attendance at podiatry and adoption of recommendations was conducted in four studies [12, 13, 27, 28].

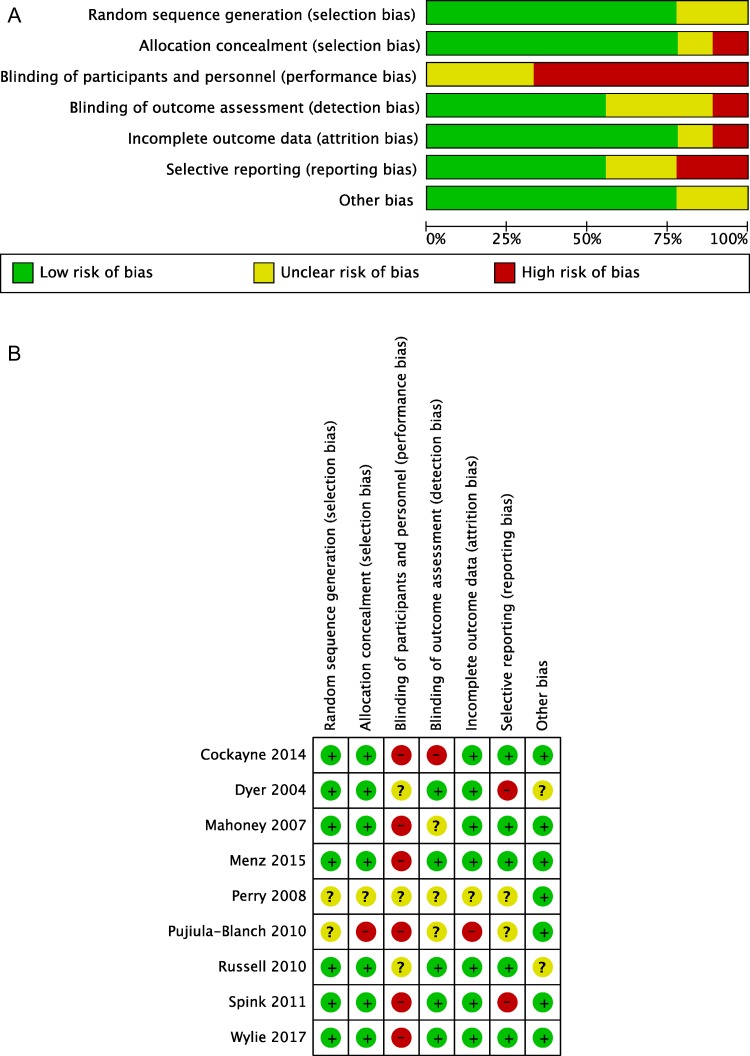

Study quality and risk of bias

Risk of bias is summarised for individual trials in Figure 2 and Appendix 4. The majority of included studies had balanced groups at baseline. Allocation concealment and methods of randomisation sequence generation were adequately reported 7/9 studies. Only five studies reported blinding of outcome assessors [13, 27, 29–31]. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding was not possible in 6/10 studies [12, 13, 28, 29, 31, 32].

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary. A. Review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. B. Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each study.

Studies reported a low level of withdrawals. Overall, ~89% of participants were retained over the follow-up period, which was similar in both intervention and control groups. One study did not report the number of withdrawals [28].

Synthesis of results and effectiveness for podiatry interventions

The included trials used a large number of heterogeneous validated and non-validated outcome measures and were recorded at multiple time points during and after the intervention period (Appendix 2).

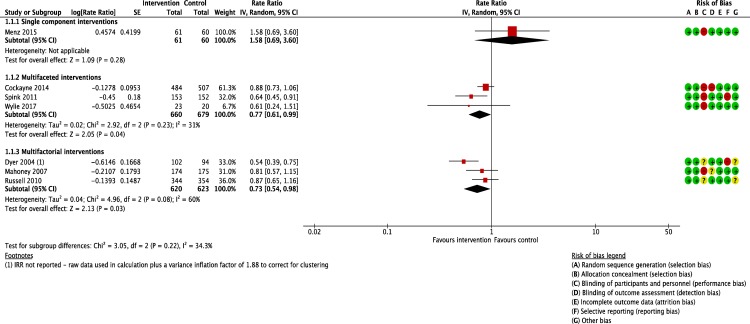

Primary outcome: falls rate

Falls rate, that is, number of falls over a defined period, was the primary outcome in seven studies (Table 1) [12, 13, 27–31]. Self-report methods using monthly falls calendars or diaries were used to report on falls rate, number of falls, time to first fall, proportion of fallers and proportion of multiple fallers. This diversity of assessment methods made comparison across the studies challenging. Two trials reported lateral balance [26] and foot pain [32] as the primary outcome with falls as a secondary or exploratory outcome. However, it was possible to calculate rate ratios for falls across multiple component podiatry interventions (three studies), multifactorial multi-disciplinary interventions (three studies) and for one single component podiatry intervention. Findings are reported below with the forest plot in Figure 3. Falls rates for individual studies and absolute differences are reported separately in Appendix 5.

Figure 3.

Forest plot: pooled results of single, multifaceted, and multifactorial interventions versus usual care: falls rate.

Single component podiatry interventions

Falls rate data were available only for one trial (n = 121 participants) for a single component podiatry intervention [32], and showed no significant effect on falls rate (RaR 1.58 [95% CI 0.69, 3.60]) (Figure 3) (Appendix 5).

Multifaceted podiatry interventions

Pooling data from the three multifaceted podiatry interventions [12, 13, 31], (n = 1,339 participants) demonstrated a significant benefit for falls rate (RaR 0.77 [95% CI 0.61, 0.99]). The absolute difference in falls rate ranged from 0.13 [34] to 0.39 [13] (Appendix 5). Overall heterogeneity was low (I2 = 31%).

Multifactorial interventions

Data for falls rates were also pooled from the three multifactorial trials which included podiatry referral as an intervention component [27, 29, 30] and showed a significantly beneficial effect when compared to usual care on falls rate (RaR 0.73 [95% CI 0.54, 0.98]) (Figure 3). The absolute falls rate difference ranged from 0.43 to 1.85 (Appendix 5). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 60%), and it is also possible that podiatry interventions were not received by those participants who were referred.

Falls prevention in care homes

Two studies examined podiatry interventions for falls prevention in care homes [30, 31]. Data could not be pooled due to heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes. One study involved a multifactorial intervention including podiatry referral [30] and although study findings significantly favoured the intervention, there was no detail about the actual podiatry treatment received. The other was a small pilot study examining a multifaceted podiatry intervention [31]. Although showing a small effect on falls rate, small sample size and high variability of scores meant no definitive conclusions about effectiveness could be drawn.

Time to first fall

Time to first fall was only measured in multifaceted podiatry interventions. None showed statistically-significant differences between intervention and control groups [12, 13, 31].

Injury data

Six studies reported injury data [13, 27–29, 31, 34]. Two studies reported rate ratios. Where reported, rate ratios for injury at the end of the intervention ranged from 0.87 [31] to 1.11 [27], suggesting no effect on falls with harm.

Secondary outcomes

There was a diverse range of secondary outcomes therefore meta-analysis was not appropriate. Studies examining number of fractures [12, 13, 27, 28], functional ability [13, 21, 32], activities of daily living [12, 13, 29] and health-related quality of life did not demonstrate any significant differences [12, 13, 31, 32]. However, significant positive effects on a range of balance measures were demonstrated in some single component podiatry interventions [26] and multifactorial interventions [30]. Although one multifaceted intervention demonstrated some between-group differences in balance, these were inconclusive [13]. Significant effects of single component interventions on foot pain and function were found using the Foot Health Status Questionnaire [32], but not the Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index used in both single and multifaceted podiatry intervention studies [13, 32].

Economic analysis

One trial reported economic data [12]. The study used the EQ-5D, demonstrating 0.0129 enhancement of quality adjusted life years (QALYs) over 12 months. The cost per QALY ranged between £19,494 and £20,593. The cost per fall averted was £1,254 [34].

Adverse events

Five studies examined adverse events [12, 13, 26, 31, 32]. In single component interventions, bruising, ankle pain and blisters [26, 32] were experienced by participants wearing insoles and off-the-shelf shoes, which diminished over time. One multifaceted podiatry intervention study [12] reported greater foot pain at 12 months in intervention participants.

Adherence

Intervention adherence and reporting of adherence was suboptimal across the trials. Six trials reported adherence using self-report methods [12, 26, 27, 29, 31, 32]. Participants in these trials reported wearing foot orthoses or footwear most or all of the time (between 37% and 56%) [13, 31]. Similarly, a third of participants reported completing exercises at the prescribed frequency of three times per day [12, 31]. Podiatry referral rates varied significantly within multifactorial interventions: the highest in one trial, at 59% of intervention group participants [30] and lowest at 32% [29]. Data for actual uptake of the podiatry intervention in the multifactorial trials were not reported.

Completion rate

The odds ratio for drop out rate was no higher in intervention than control groups, indicating that participants tolerate the podiatry interventions well as well as control group participants receiving usual care (Appendix 6).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to specifically examine the role of podiatry in falls prevention. The falls rate ratio size was broadly in line with effects of other similar interventions identified in a Cochrane Review of falls prevention interventions in community-dwelling older people [35]. In considering the role of podiatry alongside other interventions, the effect size for multifacteted podiatry interventions compared to group exercise was similar, suggesting that within multifaceted podiatry interventions, foot and ankle exercises may confer a strong protective effect against falls. This may also explain why the multifactorial effect is similar to the effect seen in multifaceted podiatry interventions. Only two studies were conducted in care homes, and study heterogeneity prevented any conclusions being drawn about effectiveness in this setting.

Study quality was moderate. Lack of participant and intervention provider blinding was a source of bias, a common issue in studies where care providers deliver interventions. Blinding of outcome assessors was undertaken in most included studies, thus detection bias was likely to be low. Seven studies recorded falls and timescales over which falls were recorded; these ranged from 1 to 12 months. This heterogeneity meant data pooling was possible for three multifaceted podiatry interventions, and three multifactorial interventions at 6 months only. Statistically-significant effects were found for both multifacteted and multifactorial interventions, but the diverse care home and community settings mean that conclusions relevant to each setting are limited.

Recommendations for standardisation of outcome and intervention reporting in falls trials are well established [33, 36]. Falls rate per person per year is recommended as the primary falls outcome [36], and a taxonomy of intervention domains [33] should be reported to ensure full intervention description. Few of the included studies adhered to all elements of current reporting recommendations. The control arm was also poorly defined in many trials. For multifactorial interventions, it was unclear if the podiatry component, usually referral or assessment, was usual care or in addition to usual care. Furthermore, in the multifactorial studies, although podiatry was an intervention component it was not clear how many participants actually received podiatry referrals, or what intervention activities were undertaken. This hampers attempts to understand the specific contribution made by podiatry interventions.

Falls were recorded by self-report falls calendar or accident reports. Both methods rely on accurate completion of written records that may not be reliably completed. Alternative objective approaches to falls assessment should be pursued to increase accuracy and validity of reporting.

Two studies evaluated effects of podiatry on falls within care homes. Differences in outcome assessment and interventions means that comparison is difficult and data pooling unfeasible. Dyer [27, 29, 30] reported significantly increased podiatry assessment frequency, but no detail about actual assessment and treatment. Wylie [31] detailed the podiatry intervention, but the study was not powered to assess effectiveness, although effect sizes were in favour of the podiatry intervention in care homes. Another Cochrane Review identified possible benefits of multifactorial interventions in care homes, and although footwear assessment was a component of some interventions, the wider package of podiatry components was not evaluated in any of the included 43 trials [18]. Thus, although the present review has shown effectiveness for podiatry interventions in community settings, the evidence for podiatry interventions in care homes is inconclusive. A full-scale trial to examine the contribution of multifaceted podiatry interventions in this setting is therefore warranted. Sample size calculations based on the results of this meta-analysis suggest that between 500 and 1,000 participants would be required for a cluster RCT. Such a trial should include health economic analysis, which has not been performed for most podiatry trials to date.

Several limitations require comment. First, despite employing comprehensive search strategies, we may not have identified all trials. Second, meta-analysis on falls rate from three multifaceted podiatry trials combined trials conducted in care homes and the community, thereby limiting the generalisability to each setting of the findings. Data are lacking on the fidelity of intervention in most studies; it is therefore unclear how many people were referred to a podiatrist or saw a podiatrist, and whether patients adhered to treatment provided. Finally, planned sub-group analysis for residential setting, level of care, intervention dose, cognitive impairment and immediate and sustained effects were not possible because of study heterogeneity and/or lack of adherence to reporting guidelines [23]. These were deviations from analyses proposed in the registered PROSPERO protocol and therefore represent a protocol deviation.

Conclusion

Multifaceted podiatry interventions can prevent falls in community-dwelling older people. However, evidence to support podiatry interventions in care homes is scant. Future studies should address this gap in knowledge, but also define the degree of disability and cognitive status of the population and follow recommended guidelines for measuring and reporting falls prevention trials.

Supplementary Material

Declarations of Conflicts of Interest: None.

Declarations of Sources of Funding: Funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government, award number CGA/16/40. The financial sponsor played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data or writing of the study.

References

- 1. Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 2006; 35(Suppl 2):ii37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davis JC, Robertson MC, Ashe MC, Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Marra CA. International comparison of cost of falls in older adults living in the community: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 2010; 21: 1295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tian Y, Thompson J, Buck D, Sonola L. Exploring the system-wide costs of falls in older people in Torbay. UK: Kings Fund, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 9: CD007146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dunn JE, Link CL, Felson DT, Crincoli MG, Keysor JJ, McKinlay JB. Prevalence of foot and ankle conditions in a multiethnic community sample of older adults. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159: 491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffith L, Raina P, Wu H, Zhu B, Stathokostas L. Population attributable risk for functional disability associated with chronic conditions in Canadian older adults. Age Ageing 2010; 39: 738–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Awale A, Hagedorn TJ, Dufour AB, Menz HB, Casey VA, Hannan MT. Foot function, foot pain, and falls in older adults: the Framingham foot study. Gerontology 2017; 63: 318–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Menz HB, Morris ME, Lord SR. Foot and ankle risk factors for falls in older people: a prospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006; 61: 866–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mickle KJ, Munro BJ, Lord SR, Menz HB, Steele JR. ISB Clinical Biomechanics Award 2009: toe weakness and deformity increase the risk of falls in older people. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2009; 24: 787–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sherrington C, Menz HB. An evaluation of footwear worn at the time of fall-related hip fracture. Age Ageing 2003; 32: 310–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cockayne S, Adamson J, Clarke A et al. Cohort Randomised Controlled Trial of a Multifaceted Podiatry Intervention for the Prevention of Falls in Older People (The REFORM Trial). PLoS One 2017; 12: e0168712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spink MJ, Menz HB, Fotoohabadi MR et al. Effectiveness of a multifaceted podiatry intervention to prevent falls in community dwelling older people with disabling foot pain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011; 342: d3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vernon W, Borthwick A, Walker J. The management of foot problems in the older person through podiatry services. Rev Clin Gerontol 2011; 21: 331–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwenk M, Jordan ED, Honarvararaghi B, Mohler J, Armstrong DG, Najafi B. Effectiveness of foot and ankle exercise programs on reducing the risk of falling in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2013; 103: 534–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hatton AL, Rome K, Dixon J, Martin DJ, McKeon PO. Footwear interventions: a review of their sensorimotor and mechanical effects on balance performance and gait in older adults. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2013; 103: 516–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Osterweil D. Falls and fall prevention in the nursing home. Clin Geriatr Med 1996; 12: 881–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 12: CD005465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JPT, Green S Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 20. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009; 339: b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morris J, Witham M, Campbell P, Frost H, Torrens C, Wylie G Podiatry interventions to reduce falls in older people. PROSPERO. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22. Farndon L. The function and purpose of core podiatry: an in-depth analysis of practice.: Sheffield Hallam University; 2006.

- 23. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014; 348: g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins JPT, Green S Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/.

- 25. The Nordic Cochrane Centre TCC Review Manager (RevMan). 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

- 26. Perry SD, Radtke A, McIlroy WE, Fernie GR, Maki BE. Efficacy and effectiveness of a balance-enhancing insole. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008; 63: 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Russell MA, Hill KD, Day LM et al. A randomized controlled trial of a multifactorial falls prevention intervention for older fallers presenting to emergency departments. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58: 2265–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pujiula Blanch M, Quesada Sabate M, Avellana Revuelta E, Ramos Blanes R, Cubi Monfort R. Grupo AABSS [Final results of a multifactorial and community intervention study for the prevention of falls in the elderly]. Aten Primaria 2010; 42: 211–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahoney JE, Shea TA, Przybelski R et al. Kenosha County falls prevention study: a randomized, controlled trial of an intermediate-intensity, community-based multifactorial falls intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dyer CA, Taylor GJ, Reed M, Dyer CA, Robertson DR, Harrington R. Falls prevention in residential care homes: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2004; 33: 596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wylie G, Menz HB, McFarlane S et al. Podiatry intervention versus usual care to prevent falls in care homes: pilot randomised controlled trial (the PIRFECT study). BMC Geriatr 2017; 17: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Menz HB, Auhl M, Ristevski S, Frescos N, Munteanu SE. Effectiveness of off-the-shelf, extra-depth footwear in reducing foot pain in older people: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015; 70: 511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamb SE, Becker C, Gillespie LD et al. Reporting of complex interventions in clinical trials: development of a taxonomy to classify and describe fall-prevention interventions. Trials 2011; 12: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cockayne S, Rodgers S, Green L et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a multifaceted podiatry intervention for falls prevention in older people: a multicentre cohort randomised controlled trial (the REducing Falls with ORthoses and a Multifaceted podiatry intervention trial). Health Technol Assess 2017; 21: 1–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 9: CD007146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lamb SE, Jorstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C. Prevention of Falls Network E, Outcomes Consensus G Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 1618–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.