Abstract

Maternal weight before and during pregnancy is associated with offspring neurobehaviour in childhood. We investigated maternal weight prior to and during pregnancy in relation to neonatal neurobehaviour. We hypothesized that maternal obesity and excessive gestational weight gain would be associated with poor neonatal attention and affective functioning. Participants (n = 261) were recruited, weighed and interviewed during their third trimester of pregnancy. Pre‐pregnancy weight was self‐reported and validated for 210 participants, with robust agreement with medical chart review (r = 0.99). Neurobehaviour was measured with the NICU Network Neurobehavioural Scale (NNNS) administered on Days 2 and 32 postpartum. Maternal exclusion criteria included severe or persistent physical or mental health conditions (e.g. chronic disease or diagnoses of Bipolar Disorder or Psychotic Spectrum Disorders), excessive substance use, and social service/foster care involvement or difficulty understanding English. Infants were from singleton, full‐term (37–42 weeks gestation) births with no major medical concerns. Outcome variables were summary scores on the NNNS (n = 75–86). For women obese prior to pregnancy, those gaining in excess of Institute of Medicine guidelines had infants with poorer regulation, lower arousal and higher lethargy. There were no main effects of maternal pre‐pregnancy body mass index on neurobehaviour. Women gaining above Institute of Medicine recommendations had neonates with better quality of movement. Additional studies to replicate and extend results past the neonatal period are needed. Results could support underlying mechanisms explaining associations between maternal perinatal weight and offspring outcomes. These mechanisms may inform future prevention/intervention strategies. © 2016 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Keywords: maternal obesity, pregnancy, weight gain, neonate, neurobehaviour, maternal public health

In the past two decades, US pre‐pregnancy obesity rates have increased steadily, with over half of women of childbearing age being overweight or obese (Huda et al. 2010). Elevated pre‐pregnancy weight increases risk for excessive gestational weight gain (GWG), above and beyond pregnancy‐related health conditions and modifiable pregnancy risk factors (Brawarsky et al. 2005). This is concerning given that elevated pre‐pregnancy weight and excessive GWG lead to pregnancy (e.g. gestational diabetes, hypertension, and pre‐eclampsia; Baeten et al. 2001) and delivery complications (e.g. caesarean sections, labour induction, and perinatal mortality; Cogswell et al. 2001). These factors could increase the risk for infant cardiovascular and neurodevelopmental outcomes given weight‐related metabolic, hormonal and oxygen transport alterations, magnified by pre‐existing obesity (Sen et al. 2012: Mann et al. 2013).

Van Lieshout and colleagues conducted two systematic reviews (Van Lieshout et al. 2011, 2013a,2013b) which revealed 22 published articles examining effects of maternal overweight/obesity on offspring cognitive, behaviour and emotional difficulties. Of these, only two examined risk markers before age 1 (i.e. fetal alcohol syndrome) and only five examined GWG. After age 1, maternal prenatal obesity was related to poorer cognitive performance from age 2 (Hinkle et al. 2012; Craig et al. 2013) to 12 (Neggers et al. 2003), and behavioural and affective difficulties from age 2 (Van Lieshout et al. 2013a,2013b) to 17 (Robinson et al. 2013; Van Lieshout et al. 2013a,2013b). Maternal gestational overweight/obesity was also related to more Attention‐Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder symptoms in 5‐year‐olds (Rodriguez 2010). Excessive GWG exacerbated, although not significantly, these effects in 7 to 12‐year‐olds (Rodriguez et al. 2008). A recent study (Keim & Pruitt 2012) found U‐shaped associations between GWG and cognitive outcomes at 4 and 7 years of age utilizing data from the U.S. Collaborative Perinatal Project, suggesting that low and high GWG may be detrimental on offspring cognitive development (i.e. standardized IQ test scores). These associations were largely eliminated after controlling for familial factors, with the exception of differences in spelling performance as a result of falling ‘above’ vs. ‘within’ Institute of Medicine (IOM) GWG guidelines. This supports the consideration of family risk factors in future research as well as IOM guidelines. Another recent investigation (Pugh et al. 2015) drawing data from the Maternal Health Practices and Child Development cohort investigated interactions between GWG and pre‐pregnancy Body Mass Index (BMI) in predicting cognitive outcomes at age 10. While interaction results were non‐significant, results suggested that pre‐pregnancy BMI may have a stronger relation than GWG to offspring intelligence and executive function, although no such comparisons have been made regarding cognitive and other neurobehavioural outcomes in the neonatal period.

To our knowledge, there are no published studies relating maternal weight before and during pregnancy to neonatal neurobehaviour. Evidence supports that GWG may exacerbate associations between pre‐pregnancy weight and early neurodevelopment, but more studies are needed. The current study examined individual and interactive effects of pre‐pregnancy obesity and GWG on neonatal neurobehaviour from 2 (early) to 32 (late) days. We hypothesized that pre‐pregnancy obesity and excessive GWG would be associated with NNNS primary outcome summary scores indicative of poorer infant attention, self‐regulation, arousal and increased need for handling and that these effects would be exacerbated by excessive GWG (i.e. above IOM guidelines based on pre‐pregnancy BMI). Secondary outcomes included excitability, stress, lethargy, asymmetrical and non‐optimal reflexes, and quality of movement summary scores on the NNNS.

Key messages:

Infants born to obese mothers who gained excess weight during pregnancy were more lethargic and less aroused immediately after birth and had more difficulties in self‐soothing at 1 month vs. obese mothers who did not gain excessive weight during pregnancy.

Additional studies are needed to replicate and extend current study results from the neonatal period through childhood.

Future studies should also explore underlying mechanisms of associations between maternal elevated perinatal weight and offspring neurobehavioural impairments to inform the development of interventions.

Detection of neonatal neurobehavioural deficits from a well‐validated instrument like the NNNS may highlight intervention targets.

Materials and methods

Participants

Current study participants' were derived from two larger studies including the Behavior and Mood of Babies and Mothers (BAM BAM) and Behavior and Mood in Mothers and Behavior in Infants (BAMBI) studies. The BAM BAM study was designed to examine effects of maternal perinatal smoking on fetal and infant neurobehaviour; the BAMBI study was designed to assess the effects of maternal perinatal depression on maternal–placental neuroendocrine dysregulation, fetal/infant stress response and fetal/infant neurobehaviour. All participants who did not meet exclusion criteria in the larger studies and had complete data for the current investigation were utilized in analyses (i.e. participants were not recruited or retained in current analyses based on BMI status).

Recruitment and data collection for the two samples occurred in Providence, Rhode Island from 2006 to 2012 using similar recruitment strategies. Pregnant women were recruited from prenatal clinics and community centres via active recruitment and passive flyers/brochures. Research assistants contacted potential participants to describe the study and screen for exclusion criteria. Both studies included (1) prospective interviews over second and/or third trimester of pregnancy; (2) delivery weight via medical chart review; and (3) infant neurobehavioural exams at M = 2 days (SD = 1 day, range 1–4 days) and M = 32 days, (SD = 3 days, range 25–46 days) postpartum. Both samples included mothers with high rates of overweight (25%) and obesity (27%). Infants included in the study were singleton, full‐term (37–42 weeks gestational age) with no major medical complications, congenital malformations or chromosomal anomalies. All had Apgar scores ≥ 7 at 5 min postpartum. Although the focus of the two studies was different, methods, variables and recruitment populations were similar, justifying the combining of samples for the current analyses. Consistently, there were no significant differences in BMI (χ 2 = 4.87, p = .181) or GWG groups (χ 2 = 1.34, p = .246) between participants enrolled in BAM BAM vs. BAMBI.

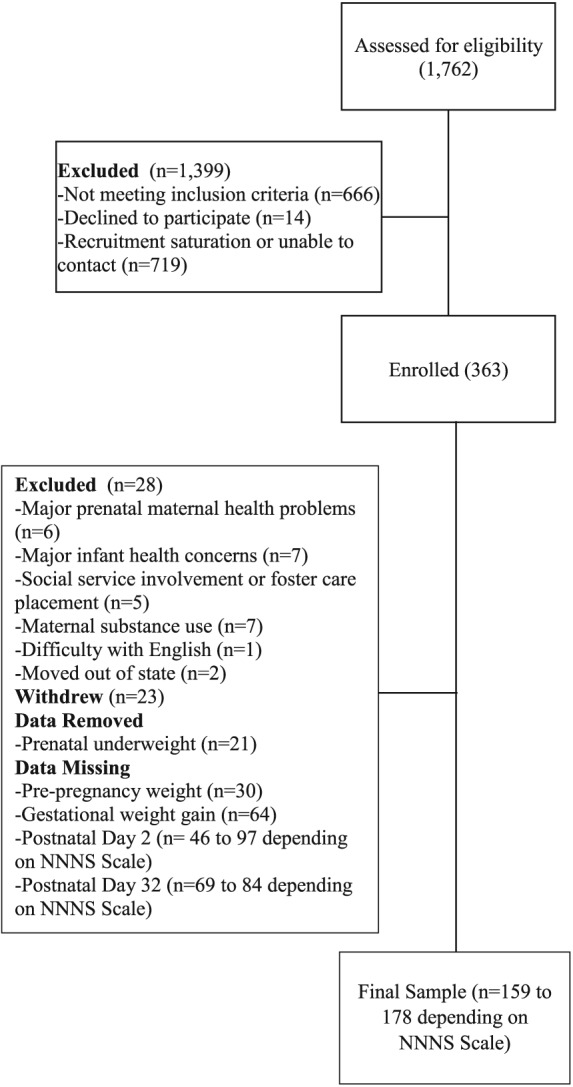

There were 1762 (497 from BAM BAM and 1265 from BAMBI) prospective participants assessed for eligibility (see Fig. 1 for a CONSORT diagram of study enrollment and attrition). Of those, 666 (147 from BAM BAM and 519 from BAMBI) did not meet inclusion criteria, 14 (5 from BAM BAM and 9 from BAMBI) declined to participate prior to being enrolled and 719 (197 from BAM BAM and 522 from BAMBI) were unreachable or unscheduled because of recruitment saturation. Three‐hundred‐and‐sixty‐three participants (148 in BAM BAM and 215 in BAMBI) were enrolled in both studies. Twenty‐eight were excluded during the study because of major prenatal maternal physical (n = 5) or mental health (n = 1) problems, pre‐term birth (n = 5), poor infant health (n = 1), infant drug withdrawal (n = 1), social service involvement (n = 4) or foster care placement (n = 1), excessive alcohol or drug use (n = 7), difficulty understanding English (n = 1) and participant relocation out of state (n = 2). An additional 23 participants withdrew during the study. Twenty‐one women who were underweight during pregnancy were removed from analyses because only eight had complete NNNS data. Thirty were missing maternal pre‐pregnancy weight, yielding 261 (72% of larger studies' enrollment) for analyses investigating main effects of pre‐pregnancy weight. An additional 64 were missing delivery weight data, yielding 197 (54% of larger studies' enrollment) for analyses of main effects of GWG. Several scales on the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS) also had missing data. Sample sizes for analyses are shown in the tables.

Figure 1.

Enrollment and attrition flowchart.

Procedure/materials

The first prenatal session (12–28 weeks gestation) included study review, consent, and interviews of participant demographics, health history and pre‐pregnancy weight. Maternal height was measured with a wall‐mounted standing stadiometer (Perspectives Enterprises, Portage, MI; accuracy ± .057 cm). Maternal pre‐pregnancy BMI was calculated with the following formula: . Participants were classified as obese (BMI ≥ 30), overweight (BMI = 25–29.9) or normal (BMI 18.5–24.9; 10). Maternal delivery weight was obtained by medical chart review. GWG was computed by subtracting pre‐pregnancy from delivery weight. Women were categorized as gaining above or below IOM recommendations, according to their pre‐pregnancy BMIs (11–15 kg for normative weight, 6–11 kg for overweight, 4–9 kg for obese women) (Rasmussen & Yaktine 2009). Medical chart review was used to validate self‐reported pre‐pregnancy weight for 210 participants, with robust agreement (r = .99).

Infant neurobehaviour was measured using a standardized assessment (NNNS; see detailed description below; Lester et al. 2004) in the hospital within the first few days after delivery and again at home in the fourth week after delivery. Trained examiners attempted to administer the first NNNS between feedings, and after infants had been changed and sleeping for approximately 30 min. NNNS examiners were blind to maternal pre‐pregnancy BMI and GWG status. These parameters were used to standardize infants' baseline states as much as possible. The NNNS examines neurological, behavioural and social components of neurobehaviour using a semi‐structured series of assessment items. Support for the NNNS comes from its widespread use and association with prenatal maternal substance use and psychopathology, (Salisbury et al. 2007, 2011) as well as health and behaviour later in childhood (Salisbury et al. 2011). Summary scores include habituation (infants' ability to tune out stimuli after initial response), attention (orientation to auditory and visual stimuli), self‐regulation (self and other soothing capabilities), arousal (states of motor arousal reached during the examination as well as irritability and response to handling), need for handling (number and type of manoeuvers required to enhance infant alertness and reduce irritability during attention task), excitability (level of motor state and physiological reactivity), stress signs (colour changes, startles and tremors), lethargy (drowsiness and non‐reactivity), hyper/hypotonicity (too much or too little muscle tone), asymmetric reflexes (consistency in strength of reflexes on left vs. right side of body), non‐optimal reflexes (the number of non‐optimal reflexive responses based on infant age) and quality of movement (motor control including smoothness, maturity and modulation). Given the missing habituation data, particularly at the late neonatal visit (infants must be asleep at the start of the NNNS for this data) and bimodal distributions of hypo‐ and hypertonicity, these scales were not used. The NNNS takes about 30 min to complete (American Psychiatric Association [APA] 1994). Infant examiners were trained and certified on the NNNS by a certified instructor at the Brown Center for the Study of Children at Risk. Certified NNNS examiners were supervised by ALS, who ensured reliability by conducting review of mock assessments with 80–90% score agreement. The study was approved by the Women and Infants Hospital and Lifespan Corporation Institutional Review Boards.

Statistical analysis

Repeated‐measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used. Although the cell sizes for the groups varied, we did not violate the core assumptions of ANOVA. Particularly, unequal cell sizes across groups may be a concern that data are heteroscedastic. However, all Levene's tests for significant effects were non‐significant. Maternal pre‐pregnancy BMI groups (3; normative, overweight, and obese) and GWG groups (2; above or below IOM guidelines based on pre‐pregnancy BMI) were utilized as between‐subjects factors, while postpartum time (i.e. infant age from early to late neonatal time periods) served as the within‐subjects factor. Main effects of group and time and the group‐by‐time interactions were evaluated. For examination of interactive effects of BMI and GWG over time, 2(time, repeated measures) by 2(GWG) by 3(BMI) factorial ANOVAs were conducted. Follow‐up, within‐time simple effects tests were used to explore significant interactions, while paired comparisons aided in examining significant main effects. The following NNNS scales were examined as outcome variables: attention, self‐regulation, arousal, handling, excitability, stress, lethargy, asymmetrical reflexes, non‐optimal reflexes and quality of movement. Sampling distributions of residuals were examined for normality and logarithmic transformations were applied for infants' asymmetrical reflex variables at both ages.

Covariates in the current analyses included: maternal depression diagnosis (Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐4th edition; past or current Major or Minor Depressive Disorder; APA 1994) and smoking (>40 or ≤40 cigarettes) during pregnancy (Timeline Followback; Brown et al. 1998; Robinson et al. 2014) because these two variables were the primary independent variables in the larger studies. Additional potential confounders were examined to determine whether they were systematically related to both predictor and outcome variables. This included conducting one‐way ANOVAs or chi‐square tests of association with maternal age, race, marital status, education, socioeconomic status from Hollingshead instrument, gravida, caffeine use, medical conditions (i.e. asthma, anaemia, gestational diabetes, hypertension and herpes simplex virus), prenatal infections, recreational substance use (including tobacco, alcohol and marijuana) and type of delivery. Infant variables assessed included: gestational age at birth, small‐for‐gestational‐age, age during early and late neonatal exams, sex, birth weight percentile, primary feeding type, fetal distress, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min postpartum and medical conditions diagnosed in the early or late neonatal period. No significant differences in the two independent variables (GWG or pre‐pregnancy BMI) were found between participants who completed all prenatal sessions vs. those who only attended the first prenatal session and those who completed prenatal but not postnatal sessions. Therefore, no adjustment was made to quantitative analyses based on current sample attrition. Given the multiple ANOVAs run, a Bonferroni correction (i.e. α = .0125) was applied to the four planned, a priori analyses (i.e. for attention, regulation, arousal and need for handling), and a Fisher's LSD correction was applied to all other exploratory analyses.

Results

No potential confounders were related to outcomes and predictors, and their distributions across pre‐pregnancy BMI and GWG groups can be seen in Table 1. Analysis sample sizes can be seen in Tables 2, 3, as well as descriptives for NNNS scores across predictors (i.e. BMI category and GWG group). Participants' mean age was 26 years (SD = 5 years). The sample was racially/ethnically diverse, including: 55% Non‐Hispanic White women; 27% Hispanic or Latina; 18% Non‐Hispanic Black; 3% Asian; 2% American Indian/Alaska Native; 1% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander and 4% multiracial. Participants were largely low‐income (59% < $40 000/year) mothers with unplanned pregnancies (65%). Most were unmarried (64%) and multiparous (52%). These sociodemographic characteristics are consistent with recruitment in low income clinics within the Providence area. Infants had similar racial and ethnic distributions as mothers. Roughly half (54%) were male, and most were delivered vaginally (73%). On average, infants were 39 weeks gestation (SD = 2 weeks) at delivery, 2 days old (SD = 1 day, range = 1–4 days) at the first NNNS session and 32 days old (SD = 3 days, range = 25–46 days) at the second NNNS session.

Table 1.

Maternal and infant descriptives by maternal pre‐pregnancy BMI and GWG groups

| Obese n = 70 | Overweight n = 65 | Normal n = 126 | Within IOM n = 90 | Above IOM n = 104 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or M(SD) | % or M(SD) | % or M(SD) | F or χ2 | p | % or M(SD) | % or M(SD) | F or χ2 | p | |

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||||

| Age (years) | 25.76(5.42) | 25.88(5.32) | 25.81(5.50) | 0.01 | .99 | 26.23(5.50) | 25.92(5.63) | 0.15 | .70 |

| Gravida | 2(1) | 3(2) | 2(2) | 3.52 | .03 | 2(2) | 2(2) | 0.02 | .90 |

| % Major depression | 28% | 20% | 27% | 7.26 | .51 | 33% | 29% | 3.83 | .43 |

| % Drug use | 25% | 34% | 33% | 2.23 | .33 | 24% | 34% | 1.97 | .16 |

| % Medical cond. | 32% | 30% | 34% | 0.43 | .81 | 31% | 31% | 0.01 | .92 |

| % Low SES | 12% | 13% | 16% | 7.10 | .53 | 11% | 11% | 3.75 | .44 |

| % Married | 31% | 35% | 39% | 17.47 | .07 | 37% | 34% | 3.99 | .55 |

| % Hispanic | 34% | 26% | 24% | 14.24 | .43 | 26% | 24% | 4.01 | .78 |

| % Non‐white | 66% | 56% | 49% | 14.24 | .43 | 56% | 50% | 4.01 | .78 |

| Neonate characteristics | |||||||||

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 39.48(1.62) | 39.06(2.68) | 39.43(1.46) | 1.25 | .29 | 39.48(1.50) | 39.51(1.85) | 0.01 | .91 |

| Birth weight % | 49.00(24.90) | 48.18(25.26) | 44.56(26.57) | 0.95 | .39 | 41.16(24.49) | 48.23(26.70) | 3.64 | .06 |

| APGAR (1 min) | 7.76(1.19) | 7.63(1.46) | 7.60(1. 76) | 0.29 | .75 | 7.77(1.40) | 7.54(1.67) | 1.05 | .31 |

| APGAR (5 min) | 9.00(0.28) | 8.72(0.99) | 8.81(0.77) | 2.83 | .06 | 8.81(0.86) | 8.87(0.56) | 0.28 | .60 |

| Early neonatal age (days) | 1.56(0.68) | 1.56(0.49) | 1.58(0.56) | 0.02 | .98 | 1.47(0.62) | 1.55(0.57) | 0.74 | .39 |

| Late neonatal age (days) | 31.68(3.40) | 32.53(3.40) | 31.73(3.19) | 1.58 | .21 | 31.96(3.34) | 31.95(3.31) | 0.01 | .98 |

| % Male infants | 52% | 57% | 54% | 0.46 | .80 | 50% | 49% | 0.02 | .89 |

| % Caesarean | 25% | 27% | 28% | 0.34 | .84 | 24% | 27% | 0.16 | .69 |

| % Fetal distress | 33% | 33% | 37% | 0.44 | .80 | 34% | 36% | 0.03 | .87 |

| % Medical cond. | 5% | 6% | 8% | 0.98 | .61 | 9% | 2% | 5.10 | .08 |

| % Breastfeeding | 32% | 24% | 29% | 1.32 | .86 | 37% | 21% | 6.49 | .04 |

Pre‐pregnancy weight group differences in semi‐continuous descriptives were investigated via ANOVAs, yielding F statistics, while differences in categorical variables were investigated using chi‐square tests of association, yielding χ2 values. The following categories were defined as such: Major Depression (diagnosis during pregnancy via SCID interview), gestational drug use (% participants ingesting >40 alcoholic drinks or smoking > 40 cigarettes or marijuana joints during pregnancy), maternal medical cond. (i.e. major maternal infections or other conditions requiring observation, hospitalization or surgery assessed from maternal interview and medical chart review), low SES (% participants in category 5 or low socioeconomic status on the Hollingshead Questionnaire), Hispanic (% of mothers reporting Hispanic ethnicity, regardless of race), Non‐white (% of mothers reporting a racial or ethnic category that was not White), and APGAR (physical functioning assessment of neonates' skin colour, heart rate, reflex irritability, muscle tone and respiration), fetal distress (% neonates diagnosed by physician as distressed and/or in utero exposure to meconium) and neonatal medical cond. (% neonates with any minor or major medical diagnoses within 30 days postpartum).

Table 2.

NNNS subscales at 2 days of age by maternal weight groups (n = 159–178)

| Early neonatal (M = 2 days) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within IOM | Above IOM | ||||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | ||

| Attention | Normal | 27 | 3.99 | 1.26 | 53 | 4.25 | 1.02 |

| Overweight | 19 | 3.86 | 1.57 | 18 | 4.32 | 1.28 | |

| Obese | 29 | 4.38 | 1.16 | 13 | 3.81 | 0.89 | |

| Total | 75 | 4.11 | 1.31 | 84 | 4.19 | 1.07 | |

| Regulation | Normal | 30 | 4.84 | 0.76 | 60 | 4.72 | 0.74 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.77 | 0.76 | 20 | 4.58 | 0.92 | |

| Obese | 33 | 4.65 | 1.09 | 15 | 4.89 | 0.64 | |

| Total | 83 | 4.74 | 0.90 | 95 | 4.72 | 0.76 | |

| Arousal | Normal | 30 | 4.39 | 0.66 | 60 | 4.55 | 0.63 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.26 | 0.60 | 20 | 4.58 | 0.58 | |

| Obese | 33 | 4.41 | 0.62 | 15 | 4.02 | 0.59 | |

| Total | 83 | 4.37 | 0.63 | 95 | 4.47 | 0.64 | |

| Handling | Normal | 29 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 60 | 0.40 | 0.21 |

| Overweight | 19 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 20 | 0.46 | 0.24 | |

| Obese | 32 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 13 | 0.41 | 0.21 | |

| Total | 80 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 93 | 0.41 | 0.22 | |

| Excitability | Normal | 30 | 4.67 | 1.88 | 60 | 4.70 | 2.20 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.80 | 2.67 | 20 | 5.10 | 2.22 | |

| Obese | 33 | 4.55 | 2.55 | 15 | 3.47 | 1.81 | |

| Total | 83 | 4.65 | 2.33 | 95 | 4.59 | 2.19 | |

| Stress abstinence | Normal | 30 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 60 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Overweight | 20 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 20 | 0.14 | 0.07 | |

| Obese | 33 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 15 | 0.13 | 0.04 | |

| Total | 83 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 95 | 0.13 | 0.06 | |

| Lethargy | Normal | 30 | 5.87 | 2.62 | 60 | 5.27 | 2.19 |

| Overweight | 20 | 6.70 | 3.15 | 20 | 5.95 | 2.68 | |

| Obese | 33 | 5.21 | 2.50 | 15 | 7.27 | 2.63 | |

| Total | 83 | 5.81 | 2.74 | 95 | 5.73 | 2.46 | |

| Asymmetrical reflexes | Normal | 30 | 1.40 | 1.22 | 60 | 1.12 | 1.11 |

| Overweight | 20 | 1.45 | 1.05 | 20 | 1.50 | 1.36 | |

| Obese | 33 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 15 | 1.53 | 1.64 | |

| Total | 83 | 1.30 | 1.11 | 95 | 1.26 | 1.26 | |

| Non‐optimal reflexes | Normal | 30 | 3.70 | 1.97 | 60 | 3.58 | 1.83 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.60 | 1.67 | 20 | 4.25 | 1.97 | |

| Obese | 33 | 3.88 | 1.83 | 15 | 4.67 | 1.76 | |

| Total | 83 | 3.99 | 1.86 | 95 | 3.89 | 1.88 | |

| Quality of movement | Normal | 30 | 4.12 | 0.48 | 60 | 4.35 | 0.61 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.08 | 0.53 | 20 | 4.39 | 0.45 | |

| Obese | 33 | 4.11 | 0.61 | 15 | 4.32 | 0.33 | |

| Total | 83 | 4.11 | 0.54 | 95 | 4.35 | 0.54 | |

Table 3.

NNNS subscales at 32 days of age by maternal weight groups (n = 161–166)

| Late neonatal (M = 32 days) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within IOM | Above IOM | ||||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | ||

| Attention | Normal | 25 | 5.19 | 1.16 | 54 | 5.50 | 1.28 |

| Overweight | 20 | 5.29 | 1.41 | 17 | 4.90 | 1.45 | |

| Obese | 33 | 5.79 | 1.27 | 12 | 5.24 | 1.10 | |

| Total | 78 | 5.47 | 1.29 | 83 | 5.34 | 1.30 | |

| Regulation | Normal | 27 | 5.47 | 0.71 | 57 | 5.56 | 0.89 |

| Overweight | 20 | 5.28 | 0.78 | 17 | 5.15 | 1.17 | |

| Obese | 33 | 5.68 | 0.82 | 12 | 5.08 | 0.94 | |

| Total | 80 | 5.51 | 0.78 | 86 | 5.41 | 0.97 | |

| Arousal | Normal | 27 | 4.01 | 0.67 | 57 | 3.98 | 0.81 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.17 | 0.83 | 17 | 4.08 | 0.86 | |

| Obese | 33 | 3.96 | 0.69 | 12 | 4.26 | 0.95 | |

| Total | 80 | 4.03 | 0.72 | 86 | 4.04 | 0.83 | |

| Handling | Normal | 26 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 56 | 0.29 | 0.24 |

| Overweight | 20 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 17 | 0.32 | 0.29 | |

| Obese | 33 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 12 | 0.40 | 0.29 | |

| Total | 79 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 85 | 0.31 | 0.26 | |

| Excitability | Normal | 27 | 2.78 | 1.93 | 57 | 2.91 | 2.25 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.05 | 2.31 | 17 | 3.29 | 2.89 | |

| Obese | 33 | 2.48 | 2.37 | 12 | 3.58 | 2.35 | |

| Total | 80 | 2.98 | 2.28 | 86 | 3.08 | 2.38 | |

| Stress abstinence | Normal | 27 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 57 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Overweight | 20 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 17 | 0.12 | 0.06 | |

| Obese | 33 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 12 | 0.10 | 0.05 | |

| Total | 80 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 86 | 0.11 | 0.05 | |

| Lethargy | Normal | 27 | 4.04 | 1.56 | 57 | 4.00 | 1.93 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.20 | 2.07 | 17 | 5.18 | 2.10 | |

| Obese | 33 | 3.61 | 1.32 | 12 | 3.50 | 1.62 | |

| Total | 80 | 3.90 | 1.61 | 86 | 4.16 | 1.98 | |

| Asymmetrical reflexes | Normal | 27 | 1.63 | 1.31 | 57 | 1.44 | 1.15 |

| Overweight | 20 | 1.65 | 1.09 | 17 | 1.82 | 1.13 | |

| Obese | 33 | 1.88 | 1.63 | 12 | 1.92 | 2.15 | |

| Total | 80 | 1.74 | 1.39 | 86 | 1.58 | 1.32 | |

| Non‐optimal reflexes | Normal | 27 | 3.93 | 1.88 | 57 | 3.75 | 1.78 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.15 | 1.69 | 17 | 3.94 | 1.43 | |

| Obese | 33 | 3.73 | 1.33 | 12 | 3.83 | 1.75 | |

| Total | 80 | 3.90 | 1.61 | 86 | 3.80 | 1.69 | |

| Quality of movement | Normal | 27 | 4.71 | 0.53 | 57 | 4.71 | 0.57 |

| Overweight | 20 | 4.74 | 0.47 | 17 | 4.79 | 0.56 | |

| Obese | 33 | 4.86 | 0.72 | 12 | 4.67 | 0.48 | |

| Total | 80 | 4.78 | 0.60 | 86 | 4.72 | 0.55 | |

NNNS scale scores at both the early (M = 2 days) and late (M = 32 days) neonatal period across pre‐pregnancy BMI categories are presented in Table 1. Within‐subjects analyses supported age‐appropriate improvements in infants' quality of movement [F(1 160) = 38.33, p < .001, η 2 partial = 0.19], regulation [F(1 160) = 29.08, p < .001, η 2 partial = 0.15], stress abstinence [F(1 160) = 7.41, p = .007, η 2 partial = 0.04], arousal [F(1 160) = 5.62, p = .019, η 2 partial = 0.03], lethargy [F(1 160) = 25.99, p < .001, η 2 partial = 0.14], need for handling [F(1 152) = 4.61, p = .033, η 2 partial = 0.03], excitability [F(1 160) = 13.95, p < .001, η 2 partial = 0.08] and attention [F(1 136) = 51.85, p < .001, η 2 partial = 0.28] from the early to late neonatal period.

Effects of pre‐pregnancy BMI and GWG on infant neurobehaviour

No significant differences were noted for BMI or GWG main effects individually.

Interaction effects of pre‐pregnancy BMI and GWG on neurobehaviour

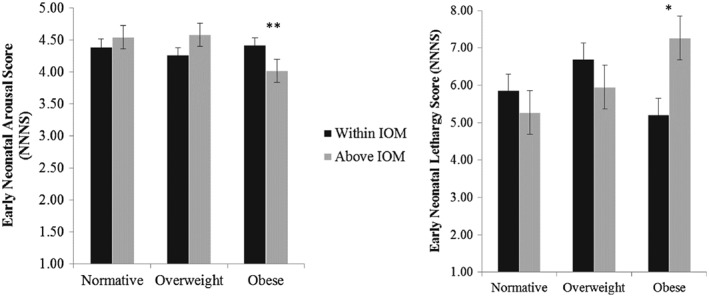

There were significant time by BMI by GWG interactions on arousal [F(1 155) = 7.31, p = .008, η 2 partial = 0.05], lethargy [F(1 155) = 13.55, p < .001, η 2 partial = 0.08] and regulation [F(1 155) = 7.47, p = .007, η 2 partial = 0.05]. For women obese prior to pregnancy, those who gained in excess of IOM guidelines compared to those gaining within IOM guidelines had infants with lower arousal [F(1 175) = 7.38, p = .007, η 2 partial = 0.04] and higher lethargy [F(1 175) = 5.84, p = .017, η 2 partial = 0.03] in the early neonatal period (see Fig. 2). Obese women gaining in excess of IOM recommendations compared to those gaining within IOM guidelines had infants with poorer regulation in the late neonatal period [F(1 163) = 4.78, p = .030, η 2 partial = 0.03].

Figure 2.

For women who were obese prior to pregnancy, those gaining in excess of IOM gestational weight recommendations had infants with lower arousal and more lethargy in the early neonatal period (M = 2 days).

Discussion

Maternal weight and neonatal neurobehaviour

Study results support our hypothesis that elevated maternal weight gain during pregnancy has a detrimental effect on offspring neonatal neurobehaviour for women who were obese prior to conception. Women who were obese prior to pregnancy and gained excessive weight during pregnancy had infants who were more lethargic and aroused or irritability in the early neonatal period (day 2). Infants of obese mothers with excessive GWG displayed poorer self‐regulation than those whose mothers did not gain excessive weight, from the early to late neonatal periods. This suggests that neonates of obese women with excessive weight gain compared to those who gained within IOM guidelines, are less active and have greater arousal/irritability.

Early deficits in infant arousal/irritability and lethargy may be because of the effects of excessive maternal prenatal weight on elevated infant glucose levels (King 2006), higher or lower (because of increased risk of pre‐term birth in obese mothers) birth weight (Lu et al. 2001), breastfeeding difficulties (Amir & Donath 2007), labour and delivery complications and/or infant developmental disorders (Catalano & Ehrenberg 2006). Therefore, these outcomes, more commonly seen in overweight and obese women, may be acute and not stable over time. Follow‐up analyses were utilized to examine whether prenatal BMI and GWG were related to maternal delivery type and infants' birth weight, gestational age, breastfeeding and medical conditions. None of these potential confounds were related to pre‐pregnancy BMI group. Similarly, none of these variables were related to GWG category or the interaction between pre‐pregnancy BMI and GWG category. Therefore, associations between maternal weight and infant neurobehaviour are unlikely to be explained by the effects of delivery complications or early medical difficulties. However, other biological mechanisms should be explored with regard to these acute effects (e.g. glucose levels and inflammation).

In the later newborn period, infants of obese women had lower regulation scores, but only if their mothers gained excessive weight in the pregnancy. Examination of group means for excitability, handling and arousal in the later newborn period suggests that these infants were irritable rather than under‐aroused or non‐reactive at this later age. This is important because increased arousal, poor self‐regulation and increased excitability on the NNNS are related to school readiness, behaviour problems and IQ, through 4.5 years of age (Liu et al. 2010).

Maternal weight and GWG may programme infant neurobehavioural development via hormonal pathways. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is the primary system that controls stress reactivity, while the hypothalamus aids in the regulation of energy homeostasis, including metabolism and appetite, as well as the regulation of mood and emotions (Ahima & Antwi 2008). Previous work with a subset of participants from the current study suggested that women who were obese prior to pregnancy and gained excessive weight during pregnancy, experienced dysregulation of their HPA axes, leading to greater release of stress hormones during the last trimester (Aubuchon‐Endsley et al. 2014). Fetal exposure to high levels of stress hormones during sensitive periods is associated with decreased infant weight (Sen et al. 2012) and may permanently programme dysregulation of HPA circuitry in offspring, particularly when coupled with genetic vulnerabilities (Duthie & Reynolds 2013).

This dysregulation could be manifested behaviourally in infants as poorer self‐regulation, associated with parental overfeeding and elevated infant weight/adiposity (Anzman‐Frasca et al. 2012). Poorer abilities to regulate emotions may also lead to poor dietary practices and weight management throughout childhood and adulthood. Thus, fetal exposure may represent the first insult in a line of complex, bidirectional processes leading to multigenerational transfer of metabolic and mental health difficulties. Future longitudinal studies are needed to investigate these hypotheses from the neonatal to later childhood periods and should investigate alternative or complimentary mechanisms that may explain study relations such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and nutrient deficiencies or excesses. It is important to begin measuring neurobehaviour in the neonatal period in order to parse apart contributions of in utero biological factors from postnatal caregiving on offspring behavioural outcomes. Additionally, pre‐pregnancy weight and GWG seemed to affect different neurobehavioural domains so the underlying mechanisms of their influence on offspring behaviour may vary and should be examined more specifically.

It is unclear why no main effects of pre‐pregnancy BMI or GWG were found in the current study given previous studies supporting these main effects (Van Lieshout et al. 2011, 2013a,2013b). More studies are needed which concurrently consider maternal pre‐pregnancy BMI and GWG. It could be that neonatal outcomes, rarely studied in relation to both maternal weight risk variables, are more robustly impacted by the interaction than longer‐term associations. It could also be that the NNNS variables used to define neurobehavioural outcomes in the current study are more sensitive to such interaction effects. Therefore, future studies should examine short‐ and long‐term effects using multiple measures of neurobehaviour to define differential sensitivities in identifying neurobehavioural deficits associated with excessive perinatal weight.

Study strengths and limitations

The current study strengths include the combination of two large datasets of mother–infant dyads followed prospectively throughout the perinatal period. The validity of maternal weight data was supported by medical chart review, and infant assessments included a well‐validated, standardized measure of multiple neurobehavioural domains. Despite these strengths, conclusions should be evaluated within the context of study limitations. Maternal pre‐pregnancy weight variables were derived via self‐report in a sample not originally intended for this purpose, while sociodemographic variables and sample sizes were not evenly dispersed across weight groups, suggesting that future studies utilize samples with matched‐samples designs. The current sample was selected to be at low risk for major adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes, and therefore results from this study may not generalize to high‐risk pregnancies including major maternal mental and physical health diagnoses. Last, corrections were not made for attrition because no differences were found in the IVs based on length of participation in the study. Therefore, results may only generalize to women who elected to initiate and maintain research involvement in the study, whose demographic characteristics can be seen in Table 1.

In sum, for women who were obese prior to pregnancy, those gaining in excess of IOM guidelines had infants with deficits in self‐regulation, arousal and lethargy though no main effects were significant. Therefore, further studies are needed to examine main and interactive effects of pre‐pregnancy BMI and GWG to determine the generalizability and stability of such findings across samples and for offspring from birth through childhood. Given mixed findings in the literature, future studies should continue examining the direction of effects between GWG and infant motor development within the context of other key variables (e.g. infant growth, nutrition and environmental aids) shown to influence motor development. Additionally, studies should focus on underlying mechanisms between maternal weight‐related risk and offspring outcomes.

Source of funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including R01MH079153 (LRS), R01DA019558 (LRS) and 2T32HL076134 (NAE). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The individual who wrote the first draft of the manuscript was Dr. Nicki Aubuchon‐Endsley, during her postdoctoral research fellowship (2T32HL076134). No honorarium, grant or other form of payment was given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributions

The seven authors contributed substantially in the following ways: NAE (data analysis/interpretation and drafting/revising the work), MM (data acquisition/interpretation and critically revising the work), CG (data acquisition/interpretation and critically revising the work), MHB (data acquisition/interpretation and critically revising the work), BML (conception/design, data interpretation and critically revising the work), ALS (conception/design, data interpretation and critically revising the work) and LRS (conception/design, data acquisition/analysis/interpretation and critically revising the work).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all of the BAM BAM and BAMBI project staff, volunteers, and participants for their many contributions.

Aubuchon‐Endsley, N. , Morales, M. , Giudice, C. , Bublitz, M. H. , Lester, B. M. , Salisbury, A. L. , and Stroud, L. R. (2017) Maternal pre‐pregnancy obesity and gestational weight gain influence neonatal neurobehaviour. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13: e12317. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12317.

References

- Ahima R.S. & Antwi D.A. (2008) Brain regulation of appetite and satiety. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America 37, 811–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Press: Washington, D.C.. [Google Scholar]

- Amir L. & Donath S. (2007) A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 7, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzman‐Frasca S., Stifter C.A. & Birch L.L. (2012) Temperament and childhood obesity risk: a review of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 33, 732–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubuchon‐Endsley N.L., Bublitz M.H. & Stroud L.R. (2014) Pre‐pregnancy obesity and maternal circadian cortisol regulation: moderation by gestational weight gain. Biological Psychology 102C, 38–43 PMCID: PMC4157070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten J.M., Bukusi E.A. & Lambe M. (2001) Pregnancy complications and outcomes among overweight and obese nulliparous women. American Journal of Public Health 91, 436–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawarsky P., Stotland N.E., Jackson R.A., Fuentes‐Afflick E., Escobar G.J., Rubashkin N. et al. (2005) Pre‐pregnancy and pregnancy‐related factors and the risk of excessive or inadequate gestational weight gain. International Journal of Gynaecology Obstetrics 91, 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R.A., Burgess E.S., Sales S.D., Whiteley J.A., Evans D. & Miller I.W. (1998) Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow‐back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 12, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano P.M. & Ehrenberg H.M. (2006) Review article: The short‐ and long‐term implications of maternal obesity on the mother and her offspring. BJOG 113, 1126–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell M.E., Perry G.S., Schieve L.A. & Dietz W.H. (2001) Obesity in women of childbearing age: risks, prevention, and treatment. Primary Care Update for Ob/Gyns 8, 89–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig W.Y., Palomaki G.E., Neveux L.M. & Haddow J.E. (2013) Maternal body mass index during pregnancy and offspring neurocognitive development. Obstetric Medicine 6, 20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie L. & Reynolds R.M. (2013) Changes in the maternal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in pregnancy and postpartum: Influences on maternal and fetal outcomes. Neuroendocrinology 98, 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle S.N., Schieve L.A., Stein A.D., Swan D.W., Ramakrishnan U. & Sharma A.J. (2012) Associations between maternal prepregnancy body mass index and child neurodevelopment at 2 years of age. International Journal of Obesity 36, 1312–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huda S.S., Brodie L.E. & Sattar N. (2010) Obesity in pregnancy: prevalence and metabolic consequences. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 15, 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim S.A. & Pruitt N.T. (2012) Gestational weight gain and child cognitive development. International Journal of Epidemiology 41, 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J.C. (2006) Maternal obesity, metabolism, and pregnancy outcomes. Annual Review of Nutrition 26, 271–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester B.M., Tronick E.Z. & Brazelton T.B. (2004) The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale procedures. Pediatrics 113, 641–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Bann C., Lester B., Tronick E., Das A., Lagasse L. et al. (2010) Neonatal neurobehavior predicts medical and behavioral outcome. Pediatrics 125, e90–e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G.C., Rouse D.J., DuBard M., Cliver S., Kimberlin D. & Hauth J.C. (2001) The effect of the increasing prevalence of maternal obesity on perinatal morbidity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 185, 845–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann J.R., McDermott S.W., Hardin J., Pan C. & Zhang Z. (2013) Pre‐pregnancy body mass index, weight change during pregnancy, and risk of intellectual disability in children. BJOG 120, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neggers Y.H., Goldenberg R.L., Ramey S.L. & Cliver S.P. (2003) Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and psychomotor development in children. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica 82, 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh S.J., Richardson G.A., Hutcheon J.A., Himes K.P., Brooks M.M., Day N.L. et al. (2015) Maternal obesity and excessive gestational weight gain are associated with components of child cognition. The Journal of Nutrition 145, 2562–2569. DOI: 10.3945/jn.115.215525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K.M. & Yaktine A.K. (2009) Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. National Academy Press: Washington DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M., Zubrick S.R., Pennell C.E., Van Lieshout R.J., Jacoby P., Beilin L.J. et al. (2013) Pre‐pregnancy maternal overweight and obesity increase the risk for affective disorders in offspring. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease 4, 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S.M., Sobell L., Sobell M.B. & Leo G.I. (2014) Reliability of the timeline followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 28, 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A. (2010) Maternal pre‐pregnancy obesity and risk for inattention and negative emotionality in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 51, 134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A., Miettunen J., Henriksen T.B., Olsen J., Obel C., Taanila A. et al. (2008) Maternal adiposity prior to pregnancy is associated with ADHD symptoms in offspring: evidence from three prospective pregnancy cohorts. International Journal of Obesity 32, 550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury A.L., Lester B.M., Seifer R., Lagasse L., Bauer C.R., Shankaran S. et al. (2007) Prenatal cocaine use and maternal depression: effects on infant neurobehavior. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 29, 331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury A.L., Wisner K.L., Pearlstein T., Battle C.L., Stroud L. & Lester B.M. (2011) Newborn neurobehavioral patterns are differentially related to prenatal maternal major depressive disorder and serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment. Journal of Depression and Anxiety 28, 1008–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S., Carpenter A.H., Hochstadt J., Huddleston J.Y., Kustanovich V., Reynolds A.A. et al. (2012) Nutrition, weight gain and eating behavior in pregnancy: a review of experimental evidence for long‐term effects on the risk of obesity in offspring. Physiology & Behavior 107, 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieshout R.J., Taylor V.H. & Boyle M.H. (2011) Pre‐pregnancy and pregnancy obesity and neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews 12, 48–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieshout R.J., Robinson M. & Boyle M.H. (2013a) Maternal pre‐pregnancy body mass index and internalizing and externalizing problems in offspring. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 58, 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieshout R.J., Schmidt L.A., Robinson M., Niccols A. & Boyle M.H. (2013b) Maternal pre‐pregnancy body mass index and offspring temperament and behavior at 1 and 2 years of age. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 44, 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]