Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) hotspots are defined as countries, regions, communities or ethnicities with higher than average incidence of CKD when compared with the worldwide, country or regional rates. Here, we describe what is known about socially determined CKD hotspots, that is, the burden of CKD among socially-defined ‘communities’ that often collocate geographically. We focus on ‘the poor’, ‘the homeless’ and ‘the food insecure’ and their intersection with other social determinants of health, including race/ethnicity. In addition to discussing the burden of CKD in these communities, we describe some efforts to mitigate this burden and identify gaps in current knowledge.

Keywords: food insecurity, poverty, homelessness, health disparities, epidemiology

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) hotspots are defined as countries, regions, communities or ethnicities with higher than average incidence of CKD when compared with the worldwide, country or regional rates. While determinants of CKD hotspots are numerous, understanding those that are socially determined could point to opportunities for prevention and early treatment of CKD among vulnerable groups. Focused efforts early in the disease course could lead to reductions in end stage kidney disease (ESKD) and mortality in these groups.

In this review, we describe some recent data on socially determined CKD hotspots, that is, the burden of CKD among socially-defined ‘communities’ that often collocate geographically. We focus on ‘the poor’, ‘the homeless’ and ‘the food insecure’ and their intersection with other social determinants of health, including race/ethnicity. In addition to discussing the burden of CKD in these communities, we describe some efforts to mitigate this burden.

‘The Poor’

Poverty is estimated to affect 12.7% of the global population1. Along with having increased risk of many adverse health conditions, people living in poverty have lower life expectancy than those with higher incomes. A U.S. study, inclusive of 1.4 billion person-year observations, found that between 2001 and 2014, higher income was associated with greater longevity, and differences in life expectancy across income groups increased.2 At the age of 40 years, the gap in life expectancy between individuals in the top and bottom 1% of the income distribution was 15 years for men and 10 years for women.2 Significant regional variability was noted in this survival gap, and the majority of the variation among individuals in the bottom income quartile was related to medical causes, including heart disease and cancer, as opposed to external causes such as vehicle crashes and homicide.2

An association between poverty, or low income, and CKD is well-established worldwide3–5. Raising the risk of CKD among the poor, is their greater burden of important antecedents and risk factors, including albuminuria6, diabetes7 and hypertension8, and the intersection of poverty with other social determinants of health, including race/ethnicity. Taken together, these factors make ‘the poor’ a CKD hotspot.

CKD Prevalence among ‘The Poor’

Intersections with Race/Ethnicity

Most studies of the relation of poverty and prevalent CKD have been performed in higher income countries, where race, ethnicity and income are often closely intertwined and income disparities are profound. For example, in the U.S., in 2011, 27.6% of blacks lived below the U.S. federal poverty level compared to 9.8% of non-Hispanic whites.9 In a study of over 20,000 black and white adults residing primarily in the southern U.S., low household income (defined as <$20,000 per year) was associated with a higher prevalence of albuminuria for both whites and blacks in unadjusted analyses. However, after adjustment for demographics, lifestyle factors, comorbid illnesses, and estimated glomerular filtration rate, there was a trend toward a stronger association between lower income levels and albuminuria in blacks, than was present among whites.10

In studies of the relation of poverty, and/or other metrics of low socioeconomic status (SES), and reduced kidney function, variable associations with race have been reported. In a racially and socioeconomically diverse urban population of U.S. adults, it was found that individual-level poverty was associated with prevalent reduced kidney function [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min per 1.73m2) among African Americans, but not among whites.11 McClellan et al. examined data from participants of the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study and found that household, but not community poverty (defined as 25% or more of the households living below the U.S. federal poverty level) was independently associated with impaired kidney function, and attenuated but did not fully explain racial differences observed in the study.12 Shoham et al. found in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study that working class membership during the life-course (a proxy for low income status) was more strongly associated with CKD among African Americans than among whites, independent of hypertension and diabetes status4. However, in an earlier ARIC study, Merkin et al. noted that living in a low SES area was associated with progressive CKD only among white men13.

Given mounting interest in understanding the contribution of APOL1 risk variants to the greater burden of CKD among persons with African ancestry, poverty and other measures of SES have also been examined in related studies. Tamrat et al. in a sample of 462 African Americans in Baltimore City, Maryland, found that the lowest income group had higher adjusted odds of mildly reduced eGFR than the higher income group [aOR 1.8, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.2–2.7], however there were no significant interactions between APOL1 risk variants and income.14 Peralta et al. examined associations of APOL1 risk variants with incident albuminuria and kidney function decline among 3030 young adults with preserved kidney function at baseline. They found that compared to whites and low-risk blacks, blacks with two APOL1 risk alleles had the highest risk for albuminuria and kidney function decline. Disparities between low- risk blacks and whites were explained by differences in traditional risk factors, including socioeconomic position.

Taken together, these studies underscore the complex relationships between poverty, race/ethnicity and kidney disease, particularly in racially and socioeconomically diverse nations such as the U.S. and suggest that interventions targeting the poor are needed to reduce CKD burden.

Summary of Recent Studies

Vart et al. conducted a systematic review of studies addressing socioeconomic disparities in CKD through January 2013.5 Among 35 studies meeting inclusion criteria, low SES was associated with low eGFR [Odds Ratio (OR)=1.41, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.21, 1.62), high albuminuria (OR=1.52, 95% CI 1.22, 1.82), low eGFR and/or high albuminuria (OR=1.38, 95% CI 1.03, 1.74), and renal failure (OR=1.55, 95% CI 1.40, 1.71). Variations in the strength of associations appeared to be primarily due to the level of adjustment for potential confounders as opposed to the choice of measure (e.g. income, education, occupation) of low SES.5

Consequences of CKD among ‘The Poor’

ESKD and Mortality

CKD can lead to several adverse health outcomes including ESKD and mortality. Prospective studies of the relation of poverty to declines in kidney function or development of ESKD are limited. Most have made use of area-level poverty or SES measures, which might serve to identify CKD hotspots in future work. Merkin et al. examined this question in the context of the ARIC study.15 Progressive CKD was defined as a serum creatinine elevation of 0.4 mg/dL or greater (>35μmol/L) during follow-up, hospitalization for CKD, or death. They found that living in the lowest versus the highest SES-area quartile was independently associated with a 60% greater risk for progressive CKD in white men after adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical factors, including individual-level SES. They found no independent association of area-level SES with progressive CKD risk in white women, African-American women or African-American men.15 In contrast, a retrospective study of over 30,000 patients initiating dialysis between 1998 and 2002 in three southeastern U.S. states by Volkova et al. found increasing neighborhood poverty was associated with increasing risk of ESKD for both African Americans and whites but the effect was greatest for African Americans.16 These studies laid the foundation for a recent report on time trends in the association of incident ESKD with area-level poverty in the U.S. This study noted that the proportion of new ESKD patients who reside in high poverty areas (those with ≥20% of households living below the federal poverty line) has increased in recent years. The percentage of U.S. adults initiating dialysis with area-level poverty increased from 27.4% during 1995 through 2004 (Period 1) to 34.0% in Period 2 (2005 through 2010).17 These proportions are in contrast to the overall proportion of the U.S. population living in high poverty areas during those time periods (10.9% in Period 1 and 12.5% in Period 2)17.

Outside of the U.S., a recent study by Akrawi et al. examined a cohort of 5.6 million adults in Sweden and used a neighborhood index inclusive of 4 items measured at the neighborhood level [low education level (<10 years of formal education), low income (defined as less than 50% of the median individual income), unemployment and receipt of social welfare].18 They found that the risk of ESKD in persons residing in the most deprived neighborhoods was increased independent of individual- level SES and comorbidities, including a 17% greater risk among men and an 18% greater risk among women.18 The impoverished/deprived areas described in the U.S. and Sweden might aptly be regarded as CKD hotspots.

Beyond risk of ESKD, some recent studies have reported a relation between poverty and mortality in CKD. Fedewa et al. examined 2,761 participants with CKD stages 3 or 4 in the REGARDS cohort.19 A total of 750 (27.5%) deaths occurred over follow up, and low income participants (annual household income <$20,000) had an elevated risk of death [Hazard Ratio (HR) = 1.58, 95% CI 1.24–2.00] compared to higher income participants. This finding was consistent among both African American and white participants, and was independent of county-level poverty.19

Bidirectional Relationship of Poverty and CKD

While most literature has focused on describing how poverty might lead to CKD and adverse CKD outcomes, a recent study points to the potential for a bidirectional association between poverty and CKD. Morton et al. analyzed data from 2914 participants (from 14 countries) of the Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP), a prospective cohort of adults with moderate-to-severe CKD.20 They found that 22% of those not in relative poverty (household income <50% of their country’s median income) at the beginning of the study had fallen into relative poverty by study end (median of 5 years). The risk of poverty increased with severity of CKD stage. Compared with participants with stage 3 CKD at baseline, the odds of falling into poverty were 51% higher for those with stage 4, 66% higher for those with stage 5, and 78% higher for those on dialysis at study baseline. Participants with a kidney transplant at study end had approximately half the risk of relative poverty of those on dialysis or those with CKD stages 3 to 5.20

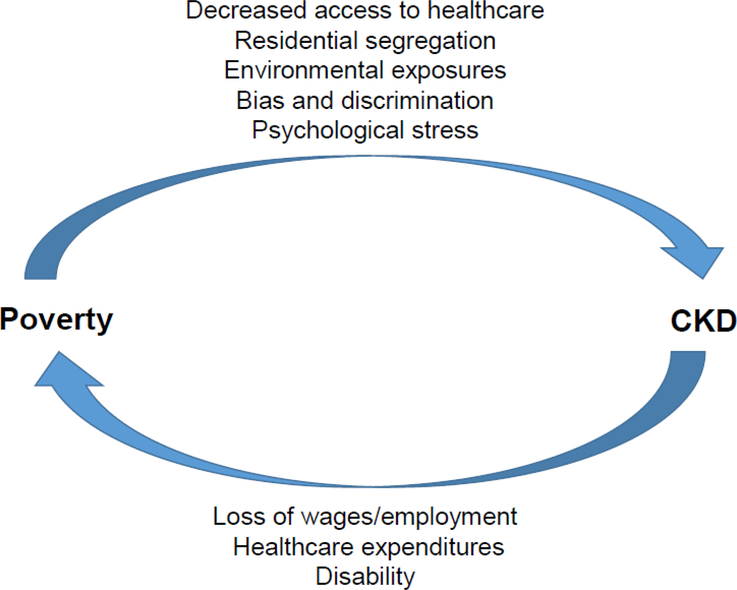

Poverty can lead to CKD through many pathways, including its impact on access to healthcare, likelihood of living in an economically segregated community with limited access to health-promoting goods and services and environmental exposures (e.g. lead).21 People living in poverty may also be subject to bias, discrimination and psychological stress that could impact their kidney health. The findings by Morton et al. call into question whether CKD might influence risk of poverty via loss of employment, high healthcare expenditures and/or disability. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

A potential bidirectional relation of poverty and CKD.

‘The Homeless’

The state of housing instability is characterized by high housing costs or unsafe living conditions that prevent general self-care and threaten independence.22,23 It is often defined as having one (or all) of the following: debilitating housing costs (i.e. >30–37% of monthly income), living in unsafe or overcrowded housing conditions, and/or notice of home foreclosure.23–26 Homelessness is a type of housing instability, and specifically refers to living in locations not meant for habitation, emergency and transitional shelters, and staying with friends or family due to lack of shelter. Many individuals transition back and forth between homelessness and states of housing instability. In January 2015, over 500,000 people were experiencing homelessness in the U.S., with an incidence rate of 17.7 per 10,000 people per year.27 Approximately 3 million people in the U.S. have experienced an episode of homelessness in their lifetime28 and homelessness has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared to domiciled individuals.29–34

CKD among ‘The Homeless’

Few published studies address CKD among individuals with housing instability, and most have focused on CKD in the setting of homelessness.35–37 In 2012, Hall et al. examined the association between homelessness and CKD outcomes in a retrospective cohort of 15,353 adults with CKD stages 3–5 who received medical care from 1996–2005 from a community health network in San Francisco.35 They reported that homeless adults had a higher prevalence of heavy proteinuria and advanced CKD than housed adults. They also had more frequent hospital admissions, relied more on emergency departments for care, had reduced odds of early nephrology referral, and were more likely to progress to ESRD or die when compared to their domiciled counterparts.35 Among the same cohort of adults with CKD, Maziarz et al. developed a risk prediction model to identify those who would most benefit from supportive services and outreach.37 In addition to lower eGFR and proteinuria, significant predictors of progression to ESKD in this population included younger age, male sex, non-white race, diabetes, and public health insurance coverage (p<0.001). They found that the incidence rate difference in ESKD for homeless versus housed individuals was 3.9 per 1000-person years, and most could have been identified years before reaching ESKD. The authors proposed targeted interventions aimed at homeless individuals at greatest risk for ESKD, and concluded that supportive services might facilitate less fragmented care, reduce emergency room and admission costs, and enable successful transition to stable housing.37

ESKD among ‘the Homeless’

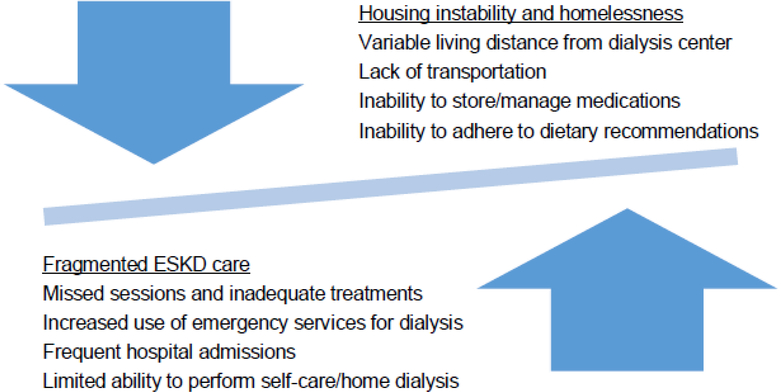

People with housing instability face multiple barriers to optimal care.23,24,37 These barriers might pose particular challenges in the setting of ESKD, making ‘the homeless’ a hotspot for poor outcomes. While understudied, homelessness likely hampers adequate management of ESKD leading to fragmented medical care, and subsequent health complications perpetuate the cycle of housing instability and homelessness. (Figure 2) For example, in one study outside of kidney disease, housing instability was associated with increased odds of not having a usual source of medical care, postponing needed medical care, increased use of the emergency department, and hospitalizations.23 In ESKD treated with in-center dialysis, frequent moves and limited transportation may lead to skipped he hospital admissions, increased engagement in care, improvements in modialysis sessions and inadequate treatment among people with housing instability. Housing instability might also make home dialysis a nearly impossible option. These barriers could lead to overreliance on emergency services for dialysis. In other populations, emergency-only dialysis has been associated with a 14-fold increased risk of death compared to standard hemodialysis.38

Figure 2.

Proposed relationship between housing instability and ESKD.

People with ESKD typically have complicated medication regimens, and housing instability might prevent proper medication storage and lead to incorrect use. Numerous dietary restrictions accompany ESKD, but housing instability, and limited control over the types of food available might impede adherence, which could precipitate electrolyte abnormalities, volume overload and even death.

Housing Programs for Persons with Chronic Illnesses

Housing programs targeting individuals with HIV, mental illness, and substance use disorders have expanded throughout the U.S. in recent years. Program offerings include the provision of housing vouchers, shortterm rental assistance, transitional housing and permanent supportive housing that combines affordable housing with medical, mental health, and local social services.39 These programs have led to reductions in hospital admissions, increased engagement in care, improvements in overall survival, and significant reductions in healthcare spending.39–41 Homeless individuals with ESKD would likely benefit from targeted housing interventions, yet such programs are few. The Ottawa Inner City Health Project (ICHP) in Canada is a housing program inclusive of services for adults with ESKD. For its residents with ESKD, the ICHP provides housing with on-site physicians, nurses and social workers to help with medication management, diet, and transportation to and from dialysis.42 The results of ICHP have been less reliance on emergency services for ESKD patients, reduced complications, and even a successful kidney transplantation.42

‘The Food Insecure’

Many individuals with low incomes experience food insecurity (“limited or uncertain ability to acquire nutritionally adequate and safe foods in socially acceptable ways”)43. In developing countries, food insecurity may lead to undernutrition and frank starvation.44,45 Rates of undernourishment are as high as 35% in some low income countries.5 However, in higher income countries, food insecurity is often associated with overnutrition, such that food insecure persons have increased risk of overweight or obesity due to high consumption of energy-dense foods with poor nutritional quality.46,47 In this setting, food insecurity has been associated with several diet-sensitive conditions, including diabetes and hypertension48,49.

CKD among ‘the Food Insecure’

An association between food insecurity and prevalent CKD has been documented among persons with either diabetes or hypertension.50 In a study by Banerjee et al.51, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III in the U.S., food insecurity was assessed as an affirmative response to the question “In the last 12 months, did you or your household ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn’t enough money for food?”52. Among 2,320 adult NHANES participants with CKD, and compared to food security, food insecurity was associated with greater risk of progression to ESKD over a median of 12 years of follow up (relative hazard 1.38; 95% CI, 1.08– 3.10).51 Thus ‘the food insecure’ can be regarded as a CKD hotspot.

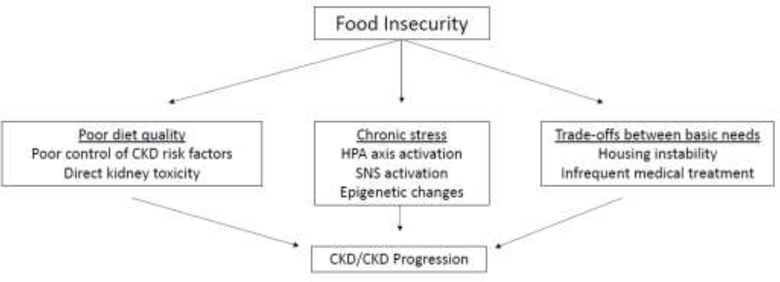

Food insecurity might lead to increased risk of CKD and CKD progression through multiple pathways (Figure 3). Diet quality is strongly influenced by financial means to purchase healthful foods. Dietary patterns impact risk of CKD and CKD progression via their influence on control of CKD risk factors (e.g. diabetes, obesity and hypertension) and via more direct toxicity, such as dietary acid load. Several observational studies have documented the association of healthful dietary patterns with favorable CKD outcomes53,54 and highlight barriers that low income individuals may face in following such diets55.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanisms by which food insecurity can lead to CKD/CKD progression. Abbreviations: HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary– adrenal; SNS, sympathetic nervous system

Food insecurity is a form of financial resource strain, and may lead to chronic psychological stress.56,57 While few empirical studies exist linking psychological stressors to kidney outcomes58–60, socially disadvantaged groups experience psychological stressors to a greater extent than the majority population, and this has been proposed as a possible explanatory link between disadvantage and greater risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease.61

Food-insecure households and individuals are not necessarily food insecure all of the time. Trade-offs can occur between paying for important basic needs, such as housing or medical bills, and purchasing nutritionally adequate foods. These trade-offs can also influence risk of CKD and CKD progression.

Addressing Food Insecurity

In several nations, food assistance is available for qualifying low income persons through governmental programs. In the U.S., the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) has few restrictions on the types of foods purchased, with the only restrictions being on the purchase of alcoholic beverages, restaurant food, and dietary supplements. A recent study examined whether incentives and purchase restrictions for SNAP eligible (but not yet enrolled) adults would lead to purchases of more healthful foods.62 The investigators found that, compared to no incentives or restrictions, paired financial incentives and restrictions on foods and beverages purchased through this program led to more healthful purchases.62 The impact of programs like this on clinical outcomes, such as CKD, is under-explored. An ongoing study addressing disparities in CKD outcomes, “Five, Plus Nuts and Beans for Kidneys” (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03299816), is testing whether tailored dietary advice from a study coach plus $30 per week worth of healthful foods will reduce urinary albumin excretion among low income African Americans with hypertension and early CKD (albuminuria with or without eGFR <60 and ≥30 ml/min/1.73m2). Many participants in this study are food insecure, affording an opportunity to address outcomes in this CKD hotspot.

Conclusions

Several socially-defined CKD hotspots exist including ‘the poor’, ‘the homeless’ and ‘the food insecure’. The risks conferred by these hotspots intersect with other risk factors for poor health outcomes among socially disadvantaged groups. Despite several reports documenting the burden of CKD in these populations, and some promising approaches to improving outcomes, there is a growing need to develop sustainable interventions and public policies mitigating this burden.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Crews was supported, in part, by grant U01MD010550 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Novick was supported by grant T32DK007732 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH.

Financial support: Supported in part by grant U01MD010550 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health (D.C.C.); and by grant T32DK007732 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (T.N.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.The World Bank. Poverty & Equita Data, 2012; http://data.worldbank.org/topic/poverty, Accessed August 15, 2016.

- 2.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States. 2001–2014. Jama. Apr 26 2016;315(16):1750–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hossain MP, Goyder EC, Rigby JE, El Nahas M. CKD and poverty: a growing global challenge. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. January 2009;53(1):166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoham DA, Vupputuri S. Kaufman JS, et al. Kidney disease and the cumulative burden of life course socioeconomic conditions: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Soc Sci Med October 2008;67(8):1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The FAO Hunger Map 2015. 2015. http://www.fao.org/hunger/en/.

- 6.Martins D Tareen N. Zadshir A. et al. The association of poverty with the prevalence of albuminuria: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. June 2006;47(6):965–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins JM. Vaccarino V, Zhang H Kasl SV Socioeconomic status and type 2 diabetes in African American and non-Hispanic white women and men: evidence from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Public Health. January 2001;91 (1):76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coresh J, Wei GL, McQuillan G, et al. Prevalence of high blood pressure and elevated serum creatinine level in the United States: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994). Arch Intern Med May 14 2001;161(9):1207–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeNavas-Walt CPPB, Smith JC. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States in 2011. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crews DC, McClellan WM, Shoham DA, et al. Low income and albuminuria among REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study participants. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. November 2012;60(5):779–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crews DC, Charles RF, Evans MK, Zonderman AB, Powe NR. Poverty, race, and CKD in a racially and socioeconomically diverse urban population. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. June 2010;55(6):992–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClellan WM, Newsome BB, McClure LA, et al. Poverty and racial disparities in kidney disease: the REGARDS study. American journal of nephrology. 2010;32(1):38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merkin SS, Coresh J, Roux AV, Taylor HA, Powe NR. Area socioeconomic status and progressive CKD: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis August 2005;46(2):203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamrat R, Peralta CA, Tajuddin SM, Evans MK, Zonderman AB, Crews DC. Apolipoprotein L1, income and early kidney damage. BMC nephrology. 2015; 16(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merkin SS, Coresh J, Diez Roux AV, Taylor HA, Powe NR. Area socioeconomic status and progressive CKD: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. August 2005;46(2):203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volkova N, McClellan W, Klein M, et al. Neighborhood poverty and racial differences in ESRD incidence. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. February 2008;19(2):356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrity BH, Kramer H, Vellanki K, Leehey D, Brown J, Shoham DA. Time trends in the association of ESRD incidence with area-level poverty in the US population. Hemodialysis International. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akrawi DS, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, Zoller B. End stage renal disease risk and neighbourhood deprivation: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. European journal of internal medicine. November 2014;25(9):853–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fedewa SA, McClellan WM, Judd S, Gutierrez OM, Crews DC. The association between race and income on risk of mortality in patients with moderate chronic kidney disease. BMC nephrology. 2014;15:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morton RL, Schlackow I, Gray A, et al. Impact of CKD on Household Income. Kidney Int Rep. May 2018;3(3):610–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholas SB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Norris KC. Socioeconomic disparities in chronic kidney disease. Advances in chronic kidney disease. January 2015;22(1):6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute TU. Preventing homelessness: meeting the challenge. Washington, D.C: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. January 2006;21(1):71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cutts DB, Meyers AF, Black MM, et al. US Housing insecurity and the health of very young children. Am J Public Health. August 2011;101 (8): 15081514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma CT, Gee L, Kushel MB. Associations between housing instability and food insecurity with health care access in low-income children. Ambul Pediatr. 2008 Jan-Feb 2008;8(1):50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid KW, Vittinghoff E, Kushel MB. Association between the level of housing instability, economic standing and health care access: a metaregression. J Health Care Poor Underserved. November 2008;19(4):1212–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Alliance to End Homelessness. The State of Homelessness in America, 2017. http://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/2016-soh.pdf Accessed June 4, 2018.

- 28.Burt MAL, Douglas T, Valente J, Lee E, Iwen B. Homelessness: Programs and the People they Serve: Findings from the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients, Technical Report. In: The Urban Institute, ed. Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer PJ, Breakey WR. The epidemiology of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among homeless persons. Am Psychol. November 1991;46(11):1115–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bird CE, Jinnett KJ, Burnam MA, et al. Predictors of contact with public service sectors among homeless adults with and without alcohol and other drug disorders. J Stud Alcohol. November 2002;63(6):716–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Booth BM, Sullivan G, Koegel P, Burnam A. Vulnerability factors for homelessness associated with substance dependence in a community sample of homeless adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(3):429–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P, Gelberg L. Determinants of regular source of care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Med Care. August 1997;35(8):814–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koegel P, Burnam MA, Farr RK. The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among homeless individuals in the inner city of Los Angeles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. December 1988;45(12):1085–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang SW, Aubry T, Palepu A, et al. The health and housing in transition study: a longitudinal study of the health of homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. Int J Public Health. December 2011;56(6):609–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall YN, Choi AI, Himmelfarb J, Chertow GM, Bindman AB. Homelessness and CKD: a cohort study. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. July 2012;7(7):1094–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall YN, Choi AI, Xu P, Smith NL, Boyko EJ. Predictors of end-stage renal disease in the urban poor. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. November 2013;24(4):1686–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maziarz M, Chertow GM, Himmelfarb J, Hall YN. Homelessness and risk of end-stage renal disease. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. August 2014;25(3):1231–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cervantes L, Tuot D, Raghavan R, et al. Association of Emergency-Only vs Standard Hemodialysis With Mortality and Health Care Use Among Undocumented Immigrants With End-stage Renal Disease. JAMA Intern Med. February 2018;178(2):188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burt MRWC, Mauch D. Medicaid and permanent supportive housing for chronically homeless individuals: literature synthesis and environmental scan.: Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Department of Health and Human Services, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ganann R, Krishnaratne S, Ciliska D, Kouyoumdjian F, Hwang SW. Effectiveness of interventions to improve the health and housing status of homeless people: a rapid systematic review. BMC Public Health. August 2011;11:638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, et al. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA April 2009;301(13):1349–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Podymow T Turnbull J Management of chronic kidney disease and dialysis in homeless persons. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). May 2013;3(2):230–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson SA. Core Indicators of Nutritional State for Difficult-to-Sample Populations. Journal of Nutrition. November 1990;120(11):1559–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasricha SR, Biggs BA. Undernutrition among children in South and South-East Asia. J Paediatr Child Health. September 2010;46(9):497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanumihardjo SA, Anderson C, Kaufer-Horwitz M, et al. Poverty, obesity, and malnutrition: an international perspective recognizing the paradox. J Am Diet Assoc. November 2007;107(11):1966–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shariff ZM, Khor GL. Obesity and household food insecurity: evidence from a sample of rural households in Malaysia. Eur J Clin Nutr. September 2005;59(9):1049–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Popkin BM. Contemporary nutritional transition: determinants of diet and its impact on body composition. Proc Nutr Soc. February 2011;70(1):82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. The Journal of nutrition. February 2010;140(2):304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castillo DC, Ramsey NL, Yu SS, Ricks M, Courville AB, Sumner AE. Inconsistent Access to Food and Cardiometabolic Disease: The Effect of Food Insecurity. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. June 2012;6(3):245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crews DC, Kuczmarski MF, Grubbs V, et al. Effect of food insecurity on chronic kidney disease in lower-income Americans. American journal of nephrology. 2014;39(1):27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banerjee T, Crews DC, Wesson DE, et al. Food Insecurity, CKD, and Subsequent ESRD in US Adults. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. July 2017;70(1):38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alaimo K, Briefel RR, Frongillo EA Jr., Olson CM Food insufficiency exists in the United States: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). American journal of public health. March 1998;88(3):419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gutierrez OM, Muntner P, Rizk DV, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of death and progression to ESRD in individuals with CKD: a cohort study. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. August 2014;64(2):204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banerjee T, Liu Y, Crews DC. Dietary Patterns and CKD Progression. Blood Purif. 2016;41(1–3):117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gutiérrez OM. Contextual poverty, nutrition, and chronic kidney disease. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2015;22(1):31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baum A, Garofalo JP, Yali AM. Socioeconomic status and chronic stress. Does stress account for SES effects on health? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896:131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holt JB. The topography of poverty in the United States: a spatial analysis using county-level data from the Community Health Status Indicators project. Preventing chronic disease. October 2007;4(4):A111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruce MA, Griffith DM, Thorpe RJ Jr. Stress and the kidney. Advances in chronic kidney disease. January 2015;22(1):46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beydoun MA, Poggi-Burke A, Zonderman AB, Rostant OS, Evans MK, Crews DC. Perceived Discrimination and Longitudinal Change in Kidney Function Among Urban Adults. Psychosom Med. September 2017;79(7):824–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lunyera J, Davenport CA, Bhavsar NA, et al. Nondepressive Psychosocial Factors and CKD Outcomes in Black Americans. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. February 7 2018;13(2):213–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Logan JG, Barksdale DJ. Allostasis and allostatic load: expanding the discourse on stress and cardiovascular disease. Journal of clinical nursing. April 2008;17(7B):201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.French SA, Rydell SA, Mitchell NR, Michael Oakes J, Elbel B, Harnack L. Financial incentives and purchase restrictions in a food benefit program affect the types of foods and beverages purchased: results from a randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. September 16 2017; 14(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]