Abstract

Residential care agencies have been making efforts to provide better quality care through the implementation of evidence-based program models and evidence-based treatments. This paper retraces the developments that led to such efforts. It further aims to answer two questions based on the available conceptual and empirical literature: (1) What is the current status on milieu-based program models that were developed for residential care settings with a therapeutic focus? (2) What is known about the implementation of client- or disorder-specific evidence-based treatments into residential care settings? Findings from this review will be integrated to provide recommendations to residential care providers about the integration of evidence-based treatments into their agencies and to point to the challenges that remain for the field.

Introduction

In 2009, the Association of Children’s Residential Centers (then still called the American Association of Children’s Residential Centers) published a paper, which provided background information to residential care providers on the use of evidence-based practices and urged the field of residential care “to embrace the EBP challenge and to develop evidence based cultures” (p.251). At that time, the authors suggested that implementing evidence-based practices was a “daunting” task for residential care providers. Eight years later, it seems appropriate to consider whether this call was heeded and what progress has been made.

This paper is written with the community of residential care providers in mind who have been wrestling with the implementation of evidence-based treatments, largely without much guidance from theory or research. In it, I attempt to take stock of the advances made in this area by first retracing the developments that led to the 2009 publication and have since then shaped the field of residential care.2 I will further aim to answer two questions based on the available conceptual and empirical literature: (1) What is the current status on milieu-based program models that were developed for residential care settings with a therapeutic focus? (2) What is known about the implementation of client- or disorder-specific evidence-based treatments into residential care settings? Findings from this review will be integrated to provide recommendations to residential care providers about the integration of evidence-based treatments into their agencies and to point to the challenges that remain for the field. 3

Towards Evidence-Based Practice in Children’s Services

One could argue that the ‘evidence-based practice debate’ fully entered real-world child-serving systems with the 1999 Surgeon General’s report on Mental Health, which included a full chapter on effective mental health treatments for children and adolescents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). The chapter, which was later published in article form by Burns, Hoagwood and Mrazek (1999) reviewed preventive treatments, traditional and community-based treatments as well as crisis and support services, aimed at addressing the mental health problems of children and adolescents. In the context of their review, the authors also summarized the cumulative evidence for residential treatment centers and community-based therapeutic group homes. Residential treatment centers were viewed critically due to their costliness, the lack of research evidence supporting their effectiveness, and their distance from children’s families and their natural communities. The authors also noted that research on residential treatment centers was mostly dated and largely based on uncontrolled studies, preventing definitive conclusions about their benefits vis-à-vis their potential risks. While therapeutic group homes were judged somewhat more favorably given their smaller size and their embeddedness in children’s natural ecology, research was again described as limited with attainment of long-term outcomes likely related to moderating and mediating factors, such as the quality and extent of aftercare services.4

Subsequently, systematic reviews and special issues on various empirically supported treatments for children and adolescents appeared in the scientific literature with some regularity, substantiating the potential of interventions considered to be less invasive than traditional long-term residential care. Funding and research priorities focused on the advancement of home- and community-based alternatives to residential care, which contributed to a growing body of knowledge on a range of treatments and services (e.g., Multisystemic Therapy, Wraparound Services, Treatment Foster Care Oregon, etc.). These efforts were aimed at preventing out-of-home care or reducing the time in such settings if placement was unavoidable. Findings derived from outcome research were disseminated to the practice community by governmental entities as well as various foundations through the growing spectrum of web-based methods, e.g., webinars, clearinghouses, etc. Through these methods, available treatments for different populations were introduced to the wider practice community, were rated and ranked, and when indicated by the criteria applied by a particular organization, received the coveted ‘evidence-based label’ (e.g., Soydan, Mullen, Alexandra, Rehnman & Li, 2011).

An entire industry devoted to the promotion of evidence-based interventions sprang up. Scientifically, these developments gained traction through the rapid growth of the interdisciplinary field of dissemination and implementation science, which focused on bridging the gap between research and practice (Dearing & Kee, 2012). The National Institute of Mental Health created a new branch devoted to implementation science and thus provided an infrastructure for the systematic investigation of the processes and outcomes related to the implementation of evidence-based interventions into real-world service settings (e.g., Brownson, Colditz & Proctor, 2012). Since then, thousands of articles have been written on implementation, and knowledge in this area has grown in leaps and bounds within a relatively short period of time.

While placement into the least restrictive placement possible had been federal policy in the United States since the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980 (P.L. 96–272), increasingly residential care came to be viewed as a placement of last resort (Frensch & Cameron, 2002; James, Landsverk, Leslie, Slymen & Zhang, 2008) and an adverse service system outcome, only to be used for youth for whom all other options had failed and in cases where no other services were available (Barth, 2002).5 Federal and state initiatives and policies as well as a number of class action lawsuits promoted, and in some cases mandated, the use of community-based interventions with empirical support over traditional residential care options (e.g., Alpert & Meezan, 2012; Lowry, 2012; Testa & Poertner, 2010). The totality of these developments put residential care at the opposite end of evidence-based practice; or in other words, evidence-based treatments were meant to replace residential care. The consequences for residential care have been varied and can be thought of in two ways: For one, they caused significant reductions in residential care in the United States. Secondly, they prompted a transformative process in the field towards the integration of evidence-based concepts.

Reductions in Residential Care

In many youth-serving systems, policies favoring community-based interventions over residential care led to the closure of some facilities, in particular smaller ones with fewer resources and less ability to diversify and restructure their services. Other agencies reduced their residential care capacity while focusing on diversifying their program offerings in order to ensure financial viability and remain attractive within the system of care (Courtney & Iwaniec, 2009; Lee & McMillen, 2007). U.S. federal child welfare statistics show a continuous decline in the proportion of children placed into group homes and residential care institutions from about 19% to 14% since 2004 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004–2016). However, significant regional variation in reductions can be noted, ranging from 7% to 78% (Malia, Quigley, Dowty & Danjczek, 2008); and some states have in fact increased placement rates into residential care settings during this time. Reasons for the continued reliance on residential care include a limited availability of alternative placement options and high rates of placement disruptions in family-based settings among youth with severe behavioral health disorders (Malia et al., 2008; Thompson, Huefner, Daly & Davis, 2014).

Trends toward reduction continue and are most aptly exemplified by current developments in California where bill AB 403, which was passed in 2015 and has begun to be implemented in 2017, redefines ‘group homes’ as short-term residential centers for youth with indicated clinical need. The expressed goal of the bill is to move all youth in out-of-home care into family-based settings as quickly as possible (California Legislative Information, 2015), effectively putting an end to traditional residential care facilities, which still provide longer-term care for children with a range of different needs. While well intended, there is evidence that such policies may have many unintended negative consequences, such as increasing the severity of problems and disorders among the residential care population (Duppong Hurley et al., 2009). This has put further strain on residential care settings, placing them into the role of ‘de facto’ psychiatric inpatient facilities or reducing them to ‘stop-gap’ options (Duppong Hurley et al., 2009; McCurdy & McIntyre, 2004). Reports from countries such as Australia or Sweden further indicate that drastic reductions in residential care placement can overwhelm already limited resources in family foster care, increase entry rates into the juvenile justice system as well as the risk that youth may be placed far away from their families and communities (Ainsworth & Hansen, 2005; Healy, Lundström & Sallnäs, 2011).

Redefining Residential Care as Evidence-based Care

While some experts have argued for a replacement of residential care through family-based options (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2014; Dozier et al., 2014), others continue to see residential care as more than a ‘last-resort placement’ or a ‘failure option.’ They see residential care as a setting that remains an essential part of a comprehensive continuum of services for children and adolescents with emotional and behavioral disorders, while acknowledging that it requires additional attention to quality of care (Blau et al., 2010; Farmer, Murray, Ballentine, Rauktis & Burns, 2017; James et al., 2006; Leichtman, 2006; Whittaker et al., 2014; Whittaker et al., 2016). Their efforts have been aimed at more clearly defining the nature and role of residential care and identifying and specifying elements that are critical to the success of residential care (e.g., Building Bridges Initiative, 2017; Pecora & English, 2016; Whittaker, 2017). From this perspective, the shifts in policy toward family-based care have been viewed as an opportunity to be leveraged toward greater quality and coherence in residential care practice.

Several articles during the early years of the new millennium emphasized the need for outcome-oriented and data-driven practice within residential care, described or argued for efforts to integrate evidence-based practice within residential care (e.g., Lovelle, 2005; McCurdy & McIntyre, 2004; Stewart & Bramson, 2000; Whittaker et al., 2006), and some even evaluated such efforts (e.g., Soberman, Greenwald & Rule, 2002; Sunseri, 2004). John Lyons’ extensive work on evidence-based assessments and outcome-oriented practice in residential care settings further highlighted the benefits of a data-driven approach for residential care (e.g., Lyons, McCulloch & Romansky, 2006; Lyons, Woltman, Martinovich & Hancock, 2009).

It is within this context that the 2009 ACRC publication was written. It asserted that residential agencies were engaged in “adding client-specific models … into their programming; introducing milieu-wide interactive approaches …; and working with community partners to send youth to evidence based treatments offered in community settings” (p.249). By doing so, it signaled the willingness of the residential care field to adjust to the new evidence-based climate and meet expectations for evidence-based practice by service systems and funders. However, it appeared that this assertion was primarily based on reports from the residential care practice field, since up to that point there had been little empirical evidence of such efforts in the literature. It was neither known what types of evidence-based interventions were being used by residential care providers nor to what degree they were being implemented; and no systematic knowledge existed on how to implement them.

Subsequent reviews addressed the three parts of the ACRC statement (James, 2011; James, Alemi & Zepeda, 2013; James, 2014). Since then, these have been augmented and updated by other reviews (Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016; Building Bridges Initiative, 2017; Pecora & English, 2016) and research studies (James et al., 2015; James, Thompson & Ringle, 2017; Ringle, James, Ross & Thompson, 2017; Stuart et al., 2009), focusing specifically on evidence-based practice and residential care (also see the 2017 Special Issue on residential care in the Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders edited by Farmer and Rauktis). In 2014, Whittaker and colleagues’ book on Therapeutic Residential Care was published and constituted an international effort to bring greater conceptual clarity to residential care practice with a treatment orientation and to develop the evidence-base of therapeutic residential care. This was followed by a Consensus Statement of the International Work Group on Therapeutic Residential care (Whittaker et al., 2016). The Statement summarized ongoing efforts to bring conceptual clarity to ‘residential care’ and explicated principles for the continued role of therapeutic residential care within an international context.

Program Models and Evidence-Based Treatments in Residential Care

Having discussed the developments leading toward a conceptual convergence (if not integration) of evidence-based practice and residential care, the second part of this paper will summarize what is currently known about the use and outcomes of evidence-based residential care program models and client- or disorder-specific evidence-based treatments in residential care.

1. What is the current status on milieu-based program models that were developed for residential care settings with a therapeutic focus?

Residential care program models can be described as milieu-wide approaches, specifically developed for the residential care context. They tend to be comprehensive in scope and potentially affect every aspect of practice within a residential care setting. Several program models can be identified from two reviews and the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (James, 2011; Pecora & English, 2016; www.cebc4cw.org): Positive Peer Culture, Boys Town Family Home Program and Teaching Family Model, The Sanctuary Model, The Stop-Gap Model, Phoenix House Academy, Children and Residential Experiences (CARE), Re-Education (Re-ED), Boys Republic Peer Accountability Model, Menninger Clinical Residential Treatment Program, and Multifunctional Treatment in Residential and Community Settings. Table 1 provides an overview of the evidence level for each model, according to the scientific rating scale used by the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse.

Table 1.

Known Program Models in Residential Care *

| Evidence level** | Models |

|---|---|

| Support (randomized controlled trial) | Positive Peer Culture |

| Promising (comparison group design) | Boys Town Family Home Program and Teaching Family Model |

| Sanctuary Model | |

| Stop-Gap Model | |

| Phoenix House Academy | |

| Children and Residential Experiences (CARE)*** | |

| Multifunctional Treatment in Residential and Community Settings (MultifunC)*** | |

| Insufficient Research Evidence (pre-post design or less) | Re-ED |

| Boys Republic Peer Accountability Model | |

| Menninger Clinical Residential Treatment |

adapted from Pecora & English (2016); also see James, 2011 and www.cebc4cw.org

reflects classification of www.cebc4cw.org

CARE and MultifunC have not yet been evaluated by the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare and ratings are preliminary and based on the author’s assessment

With regard to program models, several observations can be made: First, research on program models remains in early developmental stages. The Boystown Family Home Program – an adaptation of the Teaching Family Model – is probably the lone exception, with a sizable research base and a solid research infrastructure. However, it still lacks a controlled trial, but according to Whittaker (2017), may currently be in the strongest position to be ready for such a trial. Program models, such as Re-Ed (Hobbs, 1966) or Positive Peer Culture (Vorrath & Brendtro, 1985), were developed decades ago but their research base has not significantly advanced. So even if the sole randomized trial of the Positive Peer Culture model puts it in the ‘research-supported’ evidence category, the work is dated and new evaluative work is long overdue. The Stop-Gap Model constituted a compelling conceptual model that was evaluated once, but not developed further (McCurdy & McIntyre, 2004). The Sanctuary Model is often cited by residential care providers as being used, but to our knowledge, evaluative work has not advanced beyond three studies (Esaki et al., 2013; Rivard et al., 2004; Stein, Sorbero, Kogan & Greenberg, 2011). Phoenix House Academy targets youth with substance abuse and mental health problems and has been evaluated with positive results (Edelen, Slaughter, McCaffrey, Becker & Morral, 2010; Morral, McCaffrey & Ridgeway, 2004). The Children and Residential Experiences (CARE) model, developed at Cornell University by Martha Holden and colleagues (Holden, 2009; Holden, Anglin, Nunno & Izzo, 2014) is a relatively new model that has been exemplary in combining program development and evaluation (Izzo et al., 2016; Nunno, Smith, Martin & Butcher, 2015).6 Similarly, research is progressing on Multifunctional Treatment (MultifunC). This model was first developed in Norway to address the needs of delinquent youth within the child welfare system (Andreassen, 2015). The model is currently being implemented in several Scandinavian countries, and to date, two matched control group design studies with positive results for the experimental group have been conducted – one in Sweden and one in Norway (personal communication, T. Andreassen, 4/6/17). Results of the studies have not yet been published in English, but the outcome study conducted in Sweden has been published in a Swedish journal (www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2017/2017-1-12). Research on the remaining models has not progressed sufficiently to allow for a rating of evidence yet. As Whittaker et al. (2016) have pointed out, the lack of development in this area should not be surprising given that “it has been more than 40 years since TRC [therapeutic residential care] has received any significant government or private foundation monies for the development of model TRC programs” (p.98).

Second, comparing the various program models in their utility for residential care settings or to distill core ingredients or common elements is not straightforward. While there is some convergence in target groups and target outcomes, the theoretical underpinnings and intervention approaches show sufficient distinction to prevent derivation of a ‘meta’ model from the existing programs. And as stated, the research on the models is too uneven to draw definitive conclusions about effectiveness. However, in our view the research literature on risk and protective factors for a positive development of children’s mental health is sufficiently strong to advocate for a number of features in (therapeutic) residential care program models: small (family-like) units, a stable and well trained residential care workforce, inclusion of caregivers, a solid behavioral management program for stabilization and the promotion of prosocial skills, trauma-informed elements, timely aftercare services and avoidance of lengthy stays or repeated episodes in residential care (James, 2017; Pecora & English, 2016). Additional elements are outlined in the recently published resource guide by the Building Bridges Initiative (2017). The search for quality standards in residential care is not new (e.g., Boel-Studt & Huefner, 2017; Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016; Farmer et al., 2017; Lee & McMillen, 2007), but additional work is needed in this area to identify and empirically validate quality standards and benchmarks.

Third, information on the utilization of known program models remains limited. A recent survey7 on the use of evidence-based practices among ACRC providers (James et al., 2015; James et al., 2017) indicated that of the many evidence-based practices being implemented by residential care agencies, very few were program models. Given the extensive structural/organizational changes that would be required to shift an existing residential care program to one of the evidence-based program models, this is perhaps not surprising. It is believed that instead agencies use “home-grown” milieu-based models, which have developed over time and thus have validity within the context of an agency’s history and environmental context. These may be informed by existing models, may meet the agency’s needs for providing a general framework for their services and are, at minimum, sufficiently cogent to meet requirements for licensing and accreditation. As such, providers may simply see no need to switch to one of the more evidence-based program models, and as pointed out earlier, to date the research base of program models is not strong enough to unequivocally recommend one program over another. More concerning are data that suggest that many residential care agencies seem to lack a well-defined and specified program model and that a majority of line staff seem to be unable to describe the overall conceptual approach or theory of change of their agency (Farmer, Seifert, Wagner, Murray & Burns, in press; Guender, 2015).

In light of these challenges, there is definitive need to continue to develop the research base for existing program models. However, we also need to increase our understanding of ‘home-grown’ or ‘usual care’ program models. In the already mentioned Special Issue on residential care in the Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, Lee and McMillen (2017) recommended the development, specification and careful evaluation of “home-grown” programs as a viable alternative for residential care agencies that cannot or do not want to shift to one of the existing evidence-based program models but want to develop an overall evidence-based approach to their program. While this may in fact be the most feasible approach for many providers, systematic and iterative evaluative work takes time, resources and skills that are often not available to residential care agencies.

2. What is known about the implementation of client- and disorder-specific evidence-based treatments into residential care settings?

Despite limited use of known milieu-based program models, there is evidence that many residential care providers have begun implementing client- or disorder-specific evidence-based treatments (James et al., 2015; James et al., 2017). These are treatments or interventions that are meant to augment “residential care as usual” to address specific problems and disorders, such as aggression, trauma or self-harm. Many of these psychosocial interventions have not been developed for or in residential care, and some have in fact been created as alternatives to residential or inpatient care. Adopting a client-specific evidence-based treatment may not require the restructuring of an entire therapeutic or pedagogical concept of a facility, making it a less resource-intensive option for integrating evidence-based practice into a setting.

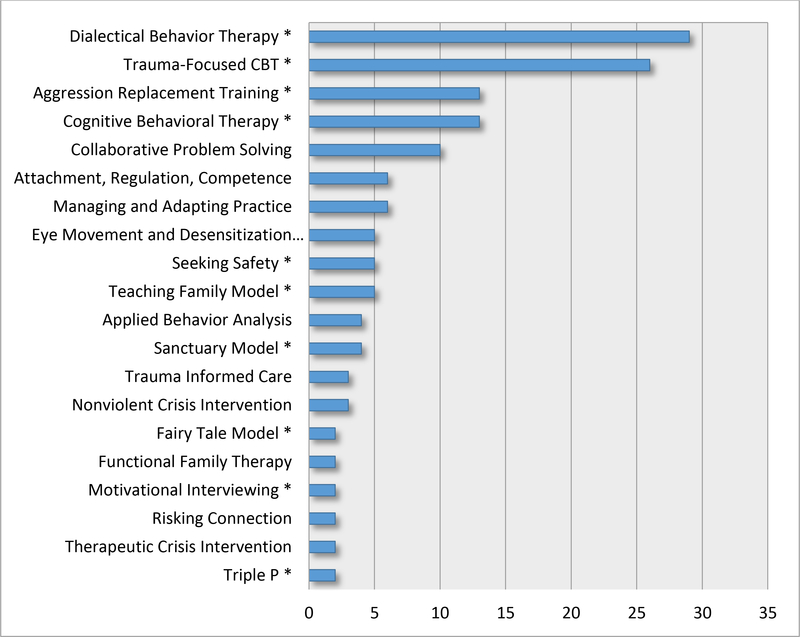

Results from the ACRC survey (James et al., 2015) indicated that 88% of agencies in our sample were implementing client-specific evidence-based treatments with two-thirds using more than one practice and one-fifth using four or five. Treatments uniformly involved cognitive-behavioral interventions and almost two-thirds implemented practices that were addressing trauma. The most utilized interventions were DBT, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Aggression Replacement Training, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Collaborative Problem Solving (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Types of Client-Specific Evidence-Based Treatments.

Note.- Table is based on data from ACRC survey (James et al., 2015); includes evidence-based treatments that were at least mentioned twice or more; all treatments with an * were validated as being ‘evidence-based’ by one of four clearinghouses; treatments without were considered evidence-based by the providers but had not been reviewed or rated by the time of publication (see James et al. 2015 for details)

Agencies adopted evidence-based interventions primarily based on their research support and promised effectiveness but also because of mandates from state and local organizations for the adoption of evidence-based approaches. While the ACRC survey data supported considerable openness toward evidence-based practice, which were concomitant with actual implementation efforts, findings related to fidelity painted a far less encouraging picture (James et al., 2017). Findings suggested that efforts to implement evidence-based treatments may be haphazard with little attention paid to sustained training and other factors necessary to ensure the integrity of the treatment, and limited understanding of what may be required to successfully implement an evidence-based intervention. This raises the question about what agencies are in fact doing when they state they are implementing evidence-based treatments, and what the reasons are that may prevent agencies from following treatment protocols. The survey’s data on barriers and facilitating factors shed some light in terms of the burden of training, the lack of resources and concerns about limiting individualized care, but findings raised the question about how many agencies are in fact simply trying to satisfy external demands for evidence-based practice without the resources, ability or required commitment to see an implementation effort through.

Beyond evidence that few agencies may in fact implement evidence-based treatments with fidelity, there are a number of other concerns: Only a few studies to date have in fact examined outcomes when evidence-based treatments, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy or Aggression Replacement Training, were implemented in residential care settings (see review by James et al., 2013). Overall, study designs were weak, lacking comparison or control groups, and results were mixed, with small and a few medium size effects in some domains, and no effects in other domains. This means that residential care providers may be overly confident that evidence-based treatments “sold” as effective on the ‘evidence-based market’ will necessarily be producing positive results in their agencies. It needs to be stated clearly that from a scientific standpoint, definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of evidence-based treatments in residential care in comparison to ‘usual care’ services cannot be drawn at this point. As such, we can only speculate which adaptations to evidence-based treatments may be necessary to increase fit and ensure effectiveness in the context of residential care settings. The ACRC survey suggested that providers made a range of adaptations to implement evidence-based treatments: making adjustments for the target group (e.g., youth with developmental and cognitive deficits), only providing part of the treatment (e.g, skills groups for DBT), making adjustments to individualize the treatment, increasing the intensity, etc. (James et al., 2017). The adaptation of either the specific treatment or the program model were also suggested by Lee and McMillen (2017) as alternatives to the whole-sale adoption of ‘packaged programs.’ These approaches are worth exploring for the residential care context.

In addition, very little is known about the conceptual fit of a chosen client-specific evidence-based treatment with the overall treatment concept of a residential care program. It is further unclear how adding multiple manualized treatments within the framework of an overall program model works and what it may add to the improvement of outcome, especially in light of the cost and resources that would be involved. This is an area ripe for research, yet also very challenging, given the number of factors and comparisons that would need to be taken into account.

Finally, the common elements approach has been suggested as a more fitting model for residential care (Barth, Kolivoski, Lindsey, Lee & Collins, 2014; Chorpita et al., 2005; Lee & McMillen, 2017). It is more flexible than standard manualized treatments, minimizes training demands, allows for greater individualization, and follows “a modularized approach to delivering the practice elements” (Lee & McMillen, 2017, p.20). Studies comparing the common elements approach to a more traditional evidence-based practice approach would certainly be of interest to the field.

Recommendations

Implementing evidence-based program models and treatments in residential care settings is neither easy, inexpensive nor straight-forward. Multiple barriers at various levels can undermine adherence and sustainability of a treatment (e.g., Aaron, Horowitz, Dlugosz & Ehrhart, 2012), and as has been shown throughout the discussion, there are many challenges that remain for residential care settings in this endeavor. Several avenues for transporting evidence-based practice into residential care have been suggested (Lee & McMillen, 2017), and it remains to be seen which model will be the most viable and effective option for residential care. Within the context of these challenges and limitations, I would like to make a few recommendations for agencies who want to become ‘more evidence-based.’

1. Take a Critical Look at Your Program Model

A sound program model is the necessary foundation or umbrella for effective residential care practice, and without it nothing else will likely matter. It constitutes ‘the other 23 hours’ (Trieschman, Whittaker & Brendtro, 1969) of the therapeutic milieu, in which development occurs and therapeutic relationships develop (Duppong Hurley, Lambert, Gross, Thompson & Farmer, 2017). If implementation of one of the current promising or research-supported programs is not feasible or desired, agencies are advised to at least review whether they have a program model that is theoretically grounded and defensible, integrates current knowledge on risk and protective factors and includes treatment elements that, with the currently available understanding, are believed most likely to contribute to good outcomes (see earlier discussion; also see Pecora & English 2016). The following guiding questions are suggested (though they are likely not exhaustive):

When did your program model develop?

What are the theories that are guiding your agency’s approach?

What is your theory of change?

What implications does your overall model have for staff, for children and their families?

How explicit is your program model in the day-to-day work of your agency?

Do all staff (residential care staff included) understand the model?

Who is responsible for the integrity of the model?

How does the model change between the levels of care?

Has the model changed over time?

Are you satisfied with the elements and the outcomes of your program model?

An important next step should be the manualization of your model. Many agencies already use manuals to guide part of their practice, but manualization is often resisted by the practice community for fear that it will undermine client-centered care and that it would stifle the ‘creative’ part of relational work with clients. Some have critically described it as a ‘paint by numbers’ approach (e.g., Silverman, 1996). Yet the process of actually manualizing a program model can lead to greater clarity about the flow and the elements of a(n already implicit) program model and can point to important conceptual gaps. Developing a manual is important in the dissemination of the model, i.e. the training of staff, and it is a necessary step for evaluative work (e.g., Addis & Cardemil, 2005).

2. Foster the Stability and Quality of Direct Care Staff

Staff turnover has been a persistent challenge for residential care agencies (e.g., Colton & Roberts, 2007; Connor et al., 2003), and reasons for it are complex and manifold and beyond the scope of this paper. High turnover rates have been associated with lower performance, low productivity and negative organizational climate and culture and have been shown to negatively impact the outcomes of services (e.g., Aarons & Sawitzky, 2008; Landsman, 2007). Quality residential care and the implementation of evidence-based approaches in residential care will not be possible without paying attention to the stability and quality of direct care staff (e.g., Aarons, Fettes, Flores & Sommerfeld, 2009). While much needs to be learned about the needs and characteristics of effective residential care staff, there is evidence from related research that enhanced (training and financial) support of staff will directly increase retention and satisfaction and indirectly affect and improve outcomes for children and youth (e.g., Chamberlain, Moreland & Reid, 1992; Glisson, Dukes & Green, 2006). Explicit inclusion of direct care staff in the training and implementation activities of a program model or specific evidence-based intervention is believed to enhance commitment and buy-in and positively affect retention. In the absence of a stable workforce, the implementation of evidence-based treatments is likely to be unsuccessful.

3. Assessing Readiness for the Implementation of (Multiple) Evidence-Based Treatments

When considering the implementation of an evidence-based model or treatment, sufficient preparation time is necessary to assess the readiness of an agency. This is seen as a vital initial step in the implementation process (Aarons, Hurlburt & Horwitz, 2011). Many purveyors of evidence-based treatments not only offer manuals and training but also provide initial consultation to assess an agency’s readiness for an evidence-based treatment. In addition, some states and counties have developed structures to guide agencies through the complex steps of implementation (e.g., Sosna & Marsenich, 2006; Aarons et al., 2014). There are also readiness scales that have been developed and could be of help to agencies in the initial decision-making and planning phase (Ehrhart, Aarons & Farahnak, 2014). Questions to be addressed during this phase include:

What is the primary reason your agency wants to adopt a specific evidence-based model/treatment?

What are your agency’s short- and long-term goals? Who is your client population?

Which evidence-based model/treatment is being considered and how does it fit you’re your agency’s client population and its stated goals?

How stable is your agency? Where is your agency developmentally (e.g., Is it a new or established agency? Has it recently gone through significant changes or even turmoil?)

Who is the initiator of this effort? Is there leadership support and buy-in? Is there buy-in from all/most staff?

How would you describe your agency’s working climate?

How committed is the agency to implementing the EBP?

Does your agency have the resources (personnel, contextual, financial) to implement the EBP?

If an agency does not meet criteria for readiness, it might be better to delay implementation efforts.

A similar approach should be taken when implementing multiple evidence-based treatments. Little is known about the implementation of multiple evidence-based interventions in one setting, and I would generally advise against implementing too many treatments within a short period of time given the training, cost and monitoring that may be involved and the high likelihood that such an effort will overwhelm the resources and capacities of an agency. It is advised that different treatments should be introduced sequentially to ensure that they are in different phases of the implementation process and not all in the preparation or initial implementation phase (Aarons et al., 2011). Questions should further be asked about the conceptual fit of different evidence-based treatments with each other and with regard to the overall program model. Finally, the question should be asked whether an agency has the resources to sustain training and fidelity monitoring for multiple evidence-based treatments. In my view, it is better to implement one evidence-based treatment well than to implement many poorly.

4. Building an Evaluation and Research Infrastructure

Evidence-based practice inherently involves systematic evaluation throughout the practice process. It is the final step in the evidence-based practice process (Thyer, 2004) and is supposed to lead to refinement in practice with the goal of improving outcomes over time. One could argue that without evaluation there is no evidence-based practice. Some agencies may have sufficient resources to build their own research and evaluation unit; others may have to partner with local universities or external evaluation/research teams (also see Thompson et al., 2017). Such partnerships can be highly fruitful and are an explicit way of closing the research to practice gap.

Conclusion

This paper shows that the field of residential care has come a long way since 2009. There is much evidence of efforts to implement evidence-based practice and considerable openness as well as appreciation for the importance of effective residential care practice. However, this review also showed that from a research standpoint, we still know very little about the processes and outcomes related to the implementation of evidence-based practice in residential care settings. As such, no clear recommendations for specific program models or client-specific evidence-based treatments can be made at this time. We therefore encourage the residential care field to not simply adopt treatments that were not designed for residential care. Lee and McMillen’s recent article opened the possibility of different avenues toward evidence-based practice that may be more fitting for the residential care context than the transportation of ‘packaged models’ into agencies. These avenues should be explored. Yet regardless of what avenue is chosen – the implementation of an existing evidence-based program model, the adaptation of an evidence-based treatment to a residential care setting, the evaluation of a ‘home-grown’ model, etc. – each one requires systematic evaluation and research. For this practice-research partnerships will be essential.

If the encouraging developments of the last eight years are any indication, we can be hopeful that the next eight years will lead to systematic investigation in this area and allow the field of residential care to finally answer the question of ‘what works.’

Footnotes

This paper was invited by the Association of Children’s Residential Centers (ACRC). It was independently written and reviewed by Dr. James Whittaker and Dr. Elizabeth Farmer. Helpful feedback was also provided by Kari Sisson. The paper does not constitute an official position of the ACRC but is an attempt to summarize the current knowledge on evidence-based practice and residential care. The paper is published in this journal since it was written with its target audience (practitioners, providers, policymakers, and researchers engaged with the field of residential care) in mind.

While this review will primarily address policy and practice developments in the United States, a number of countries have experienced similar developments. However, it is important to note that considerable variability exists cross-nationally in the conceptualization, role and utilization of residential care (Ainsworth & Thoburn, 2014).

In this paper, I will use the generic term ‘residential care’ (primarily for the sake of ease), realizing the need for definitional and conceptual clarity of the role and function of residential care in the continuum of services for children and families as well as differing opinions on the best and most precise terminology to be used (e.g., Ainsworth & Thoburn, 2014; Butler & McPherson, 2007; Lee, 2008; Whittaker, del Valle & Holmes, 2014).

It deserves noting that evidence-based practice in this context was understood as treatments, interventions or services whose effectiveness was supported by carefully implemented scientific methods (Rosen & Proctor, 2002). This definition, which is now commonly associated with evidence-based practice, is more narrow than its original conceptualization, which described evidence-based practice as the integration of expert clinical practice, empirical support and client preference (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes & Richardson, 1996).

It is important to emphasize again that there are many countries where residential care is not seen as a ‘last-resort placement’ (e.g., Ainsworth & Thoburn, 2014; Courtney & Iwaniec, 2009). In an international comparison, the United States has a very low rate of residential care utilization.

While CARE has not yet been reviewed and rated by the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse, it is expected to receive a rating of ‘promising evidence’ based on the outcome studies that have been conducted to date.

Readers are referred to James et al., 2015 and James et al. 2017 for a description of the survey’s methods.

A version of the paper was presented as a Keynote Speech on April 27, 2017 under the title Best Practice Promising Models, Evidence Based Treatments: The Intricacies of Implementation at the 61st Annual Conference of the Association of Children’s Residential Centers in Portland, Oregon, USA.

References

- Aarons GA, Fettes DL, Flores LE & Sommerfeld DH (2009). Evidence-based practice implementation and staff emotional exhaustion in children’s services. Behaviours Research and Therapy, 47(11), 954–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Fettes DL, Hurlburt MS, Palinkas LA, Gunderson L, Willging CE & Chaffin MJ (2014). Collaboration, negotiation, and coalescence for interagency-collaborative teams to scale-up evidence-based practice. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43 (6), 915–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons AA, Green AE, Trott E, Willging CE, Torres EM, Ehrhart MG & Roesch SC (2016). The roles of system and organizational leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: A mixed-method study. Administration of Policy and Mental Health, 43, 991–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Horowitz JD, Dlugosz LR, & Ehrhart MG (2012). The role of organizational processes in dissemination and implementation research In Brownson R, Colditz G, & Proctor E (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health. Translating science to practice (pp. 128–158). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38, 4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA & Sawitzky AC (2006). Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33, 289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME, & Cardemil E (2005). Psychotherapy manuals can improve outcomes In Norcross J, Beutler LE, & Levant R (Eds.), Evidence-based practices in mental health: Debate and dialogue on the fundamental questions (pp. 131–139). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth F & Hansen PA (2005). A dream come true – no more residential care. A corrective note. International Journal of Social Welfare, 14, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth F, & Thoburn J (2014). An exploration of the differential usage of residential childcare across national boundaries. International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(1), 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alpert LT, & Meezan W (2012). Moving away from congregate care: One state’s path to reform and lessons for the field. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 1519–1532. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Children’s Residential Centers (AACRC) (2009). Redefining residential: Integrating evidence-based practices. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 26, 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen T (2015). MultifunC: Multifunctional treatment in residential and community settings In Whittaker JK, del Valle JF & Holmes L (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care for children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 100–110). London, England: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Annie E Casey Foundation (2014). Rightsizing congregate care. Baltimore, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP (2002). Institutions vs. foster homes: The empirical base for the second century of debate. Chapel Hill, NC: Annie E. Casey Foundation, University of North Carolina, School of Social Work, Jordan Institute of Families. [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Kolivoski K, Lindsey MA, Lee BR & Collins K (2014). Translating common elements into social work research an education. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau GM, Caldwell B, Fisher SK, Kuppinger A, Levison-Johnson J & Lieberman R (2010). The Building Bridges Initiative: Residential and community-based providers, families and youth coming together to improve outcomes. Child Welfare, 89(2), 21–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boel-Studt SM & Huefner JC (2017). Measuring quality standards in Florida’s residential group homes. Presented at the 61st Annual Conference of the Association of Children’s Residential Centers, on 4/27/17 in Portland, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Boel-Studt SM, & Tobia L (2016). A review of trends, research, and recommendations for strengthening the evidence-base and quality of residential group care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33(1), 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson R, Colditz G, & Proctor E (2012). Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Building Bridges Initiative (2017). Best practices for residential interventions for youth and their families. A resource guide for judges and legal partners with involvement in the children’s dependency court system. Association of Children’s Residential Centers. [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Hoagwood K, & Mrazek PJ (1999). Effective Treatment for Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review, 2(4), 199–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler LS & McPherson PM (2007). Is residential treatment misunderstood? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 465–472. [Google Scholar]

- California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (n.d.). www.cebc4cw.org.

- California Legislation Information (2015). AB-403. Retrieved on 05/10/2017 from https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160AB403

- Chamberlain P, Moreland S & Reid K (1992). Enhanced services and stipends for foster parents: Effects on retention rates and outcomes for children. Child Welfare, LXXI, (5), 387–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL & Weisz JR (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7(1), 5–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton M & Roberts S (2007). Factors that contribute to high turnover among residential child care staff. Child and Family Social Work, 12, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Connor DF, McIntyre EK, Miller K, Brown C Bluestone H, Daunais D & LeBeau S (2003). Staff retention and turnover in a residential treatment center. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 20(3), 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME & Iwaniec D (Eds.) (2009). Residential care of children: Comparative perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing JW & Kee KF (2012). Historical roots of dissemination and implementation science In Brownson R, Colditz G, & Proctor EK (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (pp. 55–71). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Kaufman J, Kobak R, O’Connor TG, Sagi-Schwartz A, Scott S,…Zeanah CH (2014). Consensus statement on group care for children and adolescents: A statement of policy of the American Orthopsychiatric Association. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duppong Hurley K, Lambert M, Gross T, Thompson RW, & Farmer E (2017). The role of therapeutic alliance and model fidelity in predicting youth outcomes in therapeutic residential care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25, 37–45 [Google Scholar]

- Duppong Hurley K, Trout A, Chmelka MB, Burns BJ, Epstein MH, Thompson RW, …Daly DL (2009). The changing mental health needs of youth admitted to residential group home care. Comparing mental health status at admission in 1995 and 2004. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 17, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Edelen MO, Slaughter ME, McCaffrey DF, Becker K, & Morral AR (2010). Long-term effect of community-based treatment: Evidence from the adolescent outcomes project. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 107(1), 62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart Aarons, Faraknah Esaki ,N, Benamati J, Yanosy S, Middleton J, Hopson L, Hummer V, & Bloom S (2013). The Sanctuary Model: Theoretical framework. Families in Society, 94(2), 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ, Murray LM, Ballentine K, Rauktis ME & Burns BJ (2017). Would we know it if we saw it? Assessing quality of care in group homes for youth. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25 (19), 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ & Rauktis MB (Eds.) (2017). Special issue on the implementation of evidence-based practice in residential care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25 (1). [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ, Seifert HP, Wagner HR, Murray M, & Burns BJ (in press). Does model matter? Examining change across time for youth in group homes. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, TBA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frensch KM, & Cameron G (2002). Treatment of choice or a last resort? A review of residential mental health placements for children and youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 31(5), 307–339. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Dukes D & Green P (2006). The effects of the ARC organizational intervention on caseworker turnover, climate and culture in children’s service systems. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30, 849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guender R (2015). Praxis und Methoden der Heimerziehung. Lambertus Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Healy K, Lundström T, & Sallnäs M (2011). A comparison of out-of-home care for children and young people in Australia and Sweden: Worlds Apart?. Australian Social Work, 64(4), 416–431. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs N (1966). Helping disturbed children: Psychological and ecological strategies. American Psychologist, 21, 1105–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden MJ (2009). Children and residential experiences: Creating the conditions for change. Washington, D.C.: Child Welfare League of America. [Google Scholar]

- Holden MJ, Anglin J, Nunno MA, & Izzo C (2014). Engaging the total therapeutic residential care program in a process of quality improvement: Learning from the CARE model In Whittaker J, del Valle JF, & Holmes L (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care for children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Izzo CV, Smith EG, Holden MJ, Norton-Barker CI, & Nunno MA, & Sellers DE (2016). Intervening at the setting-level to prevent behavioral incidents in residential child care: Efficacy of the CARE program model. Prevention Science, 17, 554–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S (2011). What works in group care? A structured review of treatment models for group home and residential care. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 308–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S (2014). Evidence-based practice in therapeutic residential care In Whittaker JK, del Valle JF & Holmes L (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care for children and youth developing evidence-based international practice (pp.142–155). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- James S (2017). Best practices, promising models, evidence-based treatments: The intricacies of implementation. Keynote presented at the 61st Annual Conference of the Association of Children’s Residential Centers, 04/27/17, Portland, OR. [Google Scholar]

- James S, Alemi Q & Zepeda V (2013). Effectiveness and implementation of evidence-based practices in residential care settings. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 642–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S, Landsverk J, Leslie L, Slymen D, & Zhang J (2008). Entry into restrictive care settings—placement of last resort? Families in Society, 89(3), 348–359. [Google Scholar]

- James S, Leslie LK, Hurlburt M, Slymen DJ, Landsverk J, Davis I, Mathiesen S & Zhang J (2006). Children in Foster Care: Entry into intensive and restrictive mental health and residential care placements. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14 (4), 196–208. [Google Scholar]

- James S, Thompson RW, & Ringle JL, (2017). The implementation of evidence-based practices in residential care: Outcomes, processes, and barriers. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorder, 25(1), 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- James S, Thompson R, Sternberg N, Schnur E, Ross J, Butler L, & Muirhead J (2015). Attitudes, perceptions, and utilization of evidence-based practices in residential care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 32(2), 144–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BR (2008). Defining residential treatment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17, 689–692. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BR & McMillen JC (2007). Measuring quality in residential treatment for children and youth. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 24(1/2), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BR, & McMillen JC (2017). Pathways forward for embracing evidence-based practice in group care settings. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leichtman M (2006). Residential treatment of children and adolescents: Past, present and future. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(3), 285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelle C (2005). Dialectical behavioral therapy and EMDR for adolescents in residential treatment: A practical and theoretical perspective. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 23, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons JS, McCulloch S, & Romansky J (2006). Monitoring and managing outcomes in residential treatment: Practice-based evidence in search of evidence-based practice. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(2), 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons JS, Woltman H, Martinovich Z, & Hancock B (2009). An outcomes perspective of the role of residential treatment in the system of care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 26(2), 71–91 [Google Scholar]

- Malia MG, Quigley R, Dowty G & Danjczek M (2008). The historic role of residential group care. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 17, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy BL, McIntyre EK (2004). “And what about residential . . .?” Re-conceptualizing residential treatment as a stop-gap service for youth with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Interventions, 19, 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, & Ridgeway G (2004). Effectiveness of community-based treatment for substance-abusing adolescents: 12-month outcomes of youths entering Phoenix Academy or alternative probation dispositions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(3), 257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multifunctional Treatment in Residential and Community Settings [MultifunC institutionsbehandling för ungdomar med svåra beteendeproblem] (2017). Available at http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2017/2017-1–12

- Nunno MA, Smith EG, Martin WR & Butcher S (2015). Benefits of embedding research into practice: An agency-university collaboration. Child Welfare, 94 (3), 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pecora PJ & English DJ (2016). Elements of effective practice for children and youth served by therapeutic residential care (Research Brief). Casey Family Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle JL, James S, Ross JR, & Thompson RW (2017). Measuring youth residential care provider attitudes towards evidence-based practice: A confirmatory factor analysis of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, Online First Publication 10.1027/1015-5759/a000397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivard JC, McCorkle D, Duncan ME, Pasquale LE, Bloom SL, & Abramovitz R (2004). Implementing a trauma recovery framework for youths in residential treatment. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 21(5), 529–550. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen A, & Proctor EK (2002). Standards for evidence-based social work practice: The role of replicable and appropriate inventions, outcomes, and practice guidelines In Roberts AR & Greene GJ (Eds.), Social workers’ desk reference (pp.743–747). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB & Richardson WS (1996). Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal, 312, 71–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soberman GS, Greenwald R, & Rule DL (2002). A controlled study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for boys with conduct problems. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 6, 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Sosna T & Marsenich L (2006). Community development team model: Supporting the model adherent implementation of program and practices. Sacramento, CA: California Institute for Mental Health Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Soydan H, Mullen EJ, Alexandra L, Rehnman J & Li Y-P. (2011). Evidence-based clearinghouses in social work. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(6), 690–700. [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Sorbero M, Kogan J, & Greenberg L (2011). Assessing the Implementation of a Residential Facility Organizational Change Model: Pennsylvania’s Implementation of the Sanctuary Model. Retrieved from: http://www.ccbh.com/pdfs/articles/Sanctuary_Model_3Pager_20110715.pdf

- Stewart KL, & Bramson T (2000). Incorporating EMDR in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 17, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart C, Sanders L, Gurevich M & Fulton R (2009). Evidence-based practice in group care: The effects of policy, research, and organizational practices. Child Welfare, 90 (1), 93–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunseri PA (2004). Preliminary outcomes on the use of dialectical behavior therapy to reduce hospitalization among adolescents in residential care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 21, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Testa MF & Poertner J (2010). Fostering accountability: Using evidence to guide and improve child welfare policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RW, Duppong, Hurly K, Trout AL, Huefner JC & Daly DL (2017). Closing the research to practice gap in therapeutic residential care: Service provider-university partnerships focused on evidence-based practice. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25 (1), 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RW, Huefner JC, Daly DL & Davis JL (2014). Why quality group care is good for America’s at-risk kids: A Boys Town initiative. Boys Town, NE: Boys Town Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thyer BA (2004). What is evidence-based practice? Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 4 (2), 293–296. [Google Scholar]

- Trieschman AE, Whittaker JK, & Brendtro LK (1969). The other 23 hours: Child care work with emotional disturbed children in a therapeutic milieu. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children, Youth and Families (2004–2016). The AFCARS reports, #11–23. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1999). Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Public Health and Disease Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Vorrath H & Brendtro L (1985). Positive peer culture (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker JK (2017). Pathways to evidence-based practice in therapeutic residential care: A commentary. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25(1), 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker JK, Greene K, Blum R, Blum K, Scott K, Roy R & Savas SA (2006). Integrating evidence-based practice in the child mental health agency: A template for clinical and organizational change. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(2), 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker J, Holmes L, del Valle JF, Ainsworth F, Andreassen T, Anglin J…. & Zeira A (2016). Therapeutic residential care for children and youth: A Consensus Statement of the International Work Group on Therapeutic Residential Care. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 33(2), 89–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker J, del Valle JF, & Holmes L (Eds.). (2014). Therapeutic residential care for children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice. London, England: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]