Abstract

Background

The efficacy of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists or aldosterone antagonists in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is well known. Less is known about their effectiveness in real-world older patients with HFrEF.

Methods

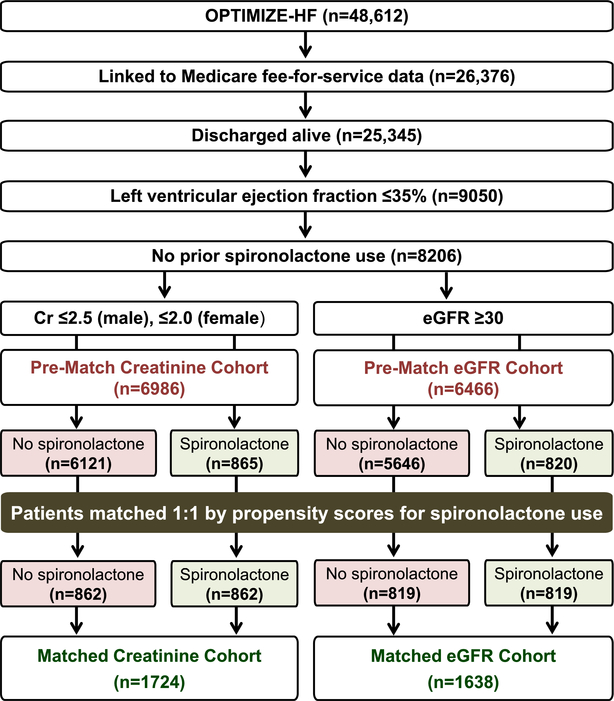

Of the 8206 patients with HF and ejection fraction ≤35% without prior spironolactone use in the Medicare-linked OPTIMIZE-HF registry, 6986 were eligible for spironolactone therapy based on serum creatinine criteria (men ≤2.5 mg/dL, women ≤2.0 mg/dL) and 865 received a discharge prescription for spironolactone. Using propensity scores for spironolactone use, we assembled a matched cohort of 1724 (862 pairs) patients receiving and not receiving spironolactone, balanced on 58 baseline characteristics (Creatinine Cohort: mean age, 75 years, 42% women, 17% African American). We repeated the above process to assemble a secondary matched cohort of 1638 (819 pairs) patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (eGFR Cohort: mean age, 75 years, 42% women, 17% African American).

Results

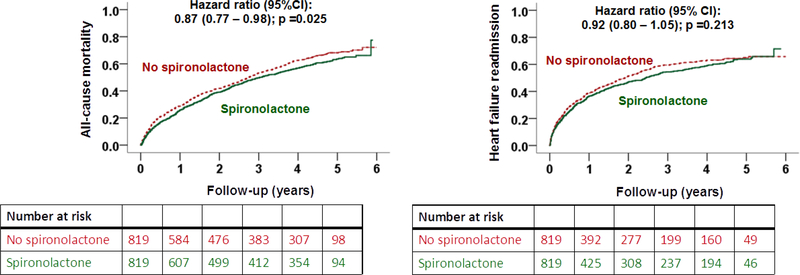

In the matched Creatinine Cohort, spironolactone-associated hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for all-cause mortality, heart failure readmission, and combined endpoint of heart failure readmission or all-cause mortality were 0.92 (0.81–1.03), 0.87 (0.77–0.99), and 0.87 (0.79–0.97), respectively. Respective hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) in the matched eGFR Cohort were 0.87 (0.77–0.98), 0.92 (0.80–1.05) and 0.91 (0.82–1.02).

Conclusions

These findings provide evidence of consistent, albeit modest, clinical effectiveness of spironolactone in older patients with HFrEF regardless of renal eligibility criteria used. Additional strategies are needed to improve the effectiveness of aldosterone antagonists in clinical practice.

Keywords: Spironolactone, Heart Failure, Ejection Fraction, Mortality, Readmission

Findings from major randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).1, 2 In the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES) trial, spironolactone reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 30% and that of heart failure hospitalization by 35% in patients with chronic HFrEF (ejection fraction <35%) with a serum creatinine concentration ≤2.5 mg/dL.1 In the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF) trial, eplerenone reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 22% and that of heart failure hospitalization by 39% in patients with chronic HFrEF (ejection fraction ≤30%) and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2. The American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association heart failure guideline recommends that clinicians should strongly consider adding a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist to patients with heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35% who are already on an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker and a beta-blocker and who meet the renal eligibility criteria for therapy with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.3 It is recommended that serum creatinine should be ≤2.5 mg/dL for men and ≤2.0 mg/dL for women, or estimated glomerular filtration rate >30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and serum potassium should be <5.0 mEq/L. It is also recommended that that these patients be closely monitored to minimize the risk of incident hyperkalemia and renal insufficiency.3

These stringent selection criteria and concerns for adverse effects might have contributed to the underutilization of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with HFrEF in clinical practice.4 Furthermore, unlike other evidence-based drugs used in HFrEF that are known for their clinical effectiveness,5–8 less is known about the clinical effectiveness of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with HFrEF in clinical practice. In one study that used serum creatinine criteria and inverse propensity weighting for risk adjustment, spironolactone use was associated with a lower risk of heart failure readmission but not of mortality.9 The objective of the current study is to examine the associations of spironolactone use with outcomes in a propensity score-matched cohort of real-world older patients with HFrEF, using both serum creatinine and eGFR criteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

The Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) registry is a national hospital-based heart failure registry, the details of which have been previously published.10–12 Briefly, OPTIMIZE-HF is based on medical records from 48,612 heart failure hospitalizations during 2003–2004 in 259 hospitals in 48 states. Patients were included if they had an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code for heart failure as principal discharge diagnosis. Detailed data on admission, hospital course and discharge were collected locally by medical record review using a data collection tool and were entered into a database using a web-based system. Long-term outcomes data were not collected and were later obtained from Medicare data using a probabilistic linking approach.13 Of the 26,376 unique OPTIMIZE-HF patients linked to the Medicare data, 25,345 were discharged alive, of which 9050 had left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35% (Figure 1). Data on spironolactone use were collected using the same approach described above.10, 14

Figure 1.

Flow chart displaying assembly of propensity score-matched Creatinine Cohort (serum creatinine ≤2.5mg/dL for men and ≤2.0mg/dL for women) and eGFR Cohort (estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2) of patients with heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, with no prior spironolactone therapy

Assembly of an Inception Cohort

Of the 9050 patients discharged alive, 844 (9%) were receiving spironolactone at the time of hospital admission. To attenuate bias associated with prevalent medication use,15 we excluded these patients. Thus, our inception cohort consisted of 8206 patients who were not already receiving spironolactone (Figure 1).

Assembly of Spironolactone-Eligible Cohorts

Of the 8206 patients with EF ≤35% and not receiving pre-admission spironolactone, 6986 were eligible for spironolactone therapy based on the serum creatinine criteria (≤2.5 mg/dL for men and ≤2.0 mg/dL for women) – the Creatinine Cohort (Figure 1). Of these, 416 (6%) had eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, of which 38 (9%) received spironolactone. We then assembled a secondary cohort of 6466 patients based on the eGFR criteria (≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2) – the eGFR Cohort (Figure 1). Of these, 19 (16 men) did not meet the serum creatinine criteria for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, of which 3 received spironolactone.

Assembly of Balanced Propensity Score-Matched Cohorts

In a randomized control trial of spironolactone, patients receiving and not receiving spironolactone would have a 50% probability of receiving the drug, and this balance in probability ensures a between-group balance on measured and unmeasured baseline characteristics. In clinical practice, the probability of receiving spironolactone would vary between 0% and 100%, which can be estimated as propensity scores based on measured baseline characteristics.16, 17 Of the 6986 patients in the Creatinine Cohort, 865 received a discharge prescription for spironolactone.

We estimated propensity scores for the receipt of a discharge prescription for spironolactone for each of the 6986 patients using a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model in which the receipt of spironolactone was the dependent variable and 58 baseline characteristics were used as covariates (Figure 2).5–8 Using a greedy matching protocol described elsewhere,18, 19 we were able to match 862 of the 865 patients receiving spironolactone by their propensity scores with another 862 patients not receiving spironolactone, thus assembling our matched Creatinine Cohort of 1724 patients (Figure 1). Of these, 75 (4%) had eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, of whom 38 (51%) received spironolactone.

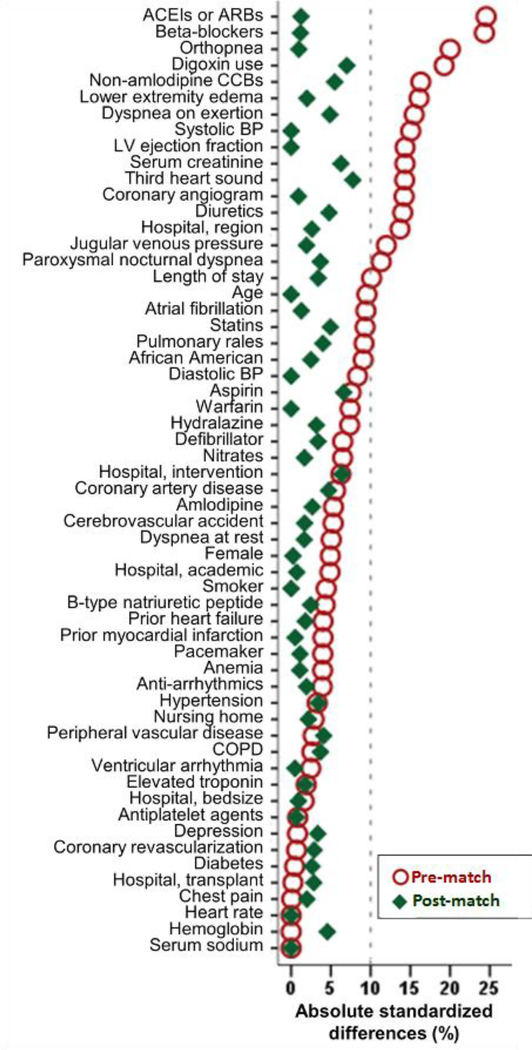

Figure 2.

Love plot displaying absolute standardized differences for 58 baseline characteristics between patients receiving and not receiving a discharge prescription for spironolactone, before and after propensity score matching. Data based on patients with heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, no prior spironolactone therapy, and serum creatinine ≤2.5mg/dL for men and ≤2.0mg/dL for women. A standardized difference of 0% indicates no residual bias and values <10% indicate inconsequential bias (ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blockers; BP=blood pressure; CCB= calcium channel blocker; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

Of the 6466 patients in the eGFR Cohort, 820 received a discharge prescription for spironolactone. We then repeated the above process to assemble a balanced matched eGFR Cohort of 1638 (819 pairs) patients (Figure 1). Only 5 (4 men) of these matched patients did not meet the serum creatinine criteria for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, of which 3 received spironolactone.

Outcomes Data

The main outcomes of the current analysis were all-cause mortality, heart failure readmission, and the combined endpoint of heart failure readmission or all-cause mortality during 6 (median, 2.9) years of follow-up. We also examined associations with all-cause readmission and the combined endpoint of all-cause readmission or all-cause mortality. Data on all outcome events and time to events were collected from Medicare data.13

Statistical Analyses

We compared baseline characteristics between patients receiving and not receiving spironolactone using Pearson’s Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate. Love plots were developed based on absolute standardized differences to assess between-group balance in baseline characteristics. All outcome analyses were conducted using matched data. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to compare between-group all-cause mortality in the matched data. Cox regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) associated with spironolactone use and outcomes.

To examine if significant associations observed in our matched data could be explained away by an unmeasured confounder, we conducted formal sensitivity analyses using Rosenbaum’s approach.20 We used a sign-score test to calculate “sensitivity bounds” for an imaginary unmeasured confounder to determine how much it would need to increase the odds of spironolactone use to explain away its significant associations with outcomes. To directly compare survival times or event-free survival times within pairs, we included pairs for which we had data on events and time to event for both members of the pair and excluded pairs in which one member was censored before an event in the other member or in which survival times were the same for both members. We then tested whether, in the absence of a hidden bias, patients in one group had a longer survival time compared to their counterparts in the other group.

To determine if the results of our study could be replicated using the weighted inverse propensity score method, we repeated our analysis using that approach, limiting all outcomes at 3 years.9 The weight is defined as the inverse of propensity scores and was calculated as 1/ propensity scores for patients receiving spironolactone and 1/ (1– propensity scores) for those not receiving spironolactone.21 We then applied these weights to our pre-match Creatinine Cohort (n=6986) to generate a weighted synthetic sample (n=13,086).22 Finally, we used multivariable-adjusted Cox regression models to examine the association of spironolactone use and outcomes in the pre-match Creatinine Cohort data adjusting for propensity scores and the 58 baseline characteristics used to estimate propensity scores. We used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS software, version 8 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The 1724 matched patients in the Creatinine Cohort had a mean (±SD) age of 75 (±11) years, 42% were women, and 17% African American. They had a mean ejection fraction of 24% (±7%) and a mean serum creatinine of 1.4 (±0.5) mg/d. Before matching, patients in the spironolactone group were younger with a lower mean systolic blood pressure, ejection fraction and serum creatinine, but had a similar comorbidity burden (Table 1). These patients also had a higher symptom burden and a higher proportion was receiving heart failure medications (Table 1). These and other imbalances in all measured baseline characteristics were balanced after matching, and absolute standardized difference for all 58 baseline characteristics were <10%, suggesting inconsequential between-group differences (Table 1 and Figure 2). Matched patients in the eGFR Cohort also had a mean (±SD) age of 75 (±11) years, 42% were women, and 17% African American, and were similarly balanced on all 58 measured baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by New Discharge Prescription for Spironolactone in Patients with Heart Failure, Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction ≤35% and Serum Creatinine ≤2.5 mg/dL for Men and ≤2.0 mg/dL for Women, Before and After Propensity Score Matching

| Characteristic | Before Propensity Score Matching (n=6986) |

After Propensity Score Matching (n=1724) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone |

P value | Spironolactone |

P value | |||

| No (n=6121) | Yes (n=865) | No (n=862) | Yes (n=862) | |||

| Age (years) | 76(±10) | 75 (±11) | 0.001 | 75 (±11) | 75 (±11) | 0.517 |

| Women | 2435 (40) | 365 (42) | 0.175 | 365(42) | 364 (42) | 0.961 |

| African American | 802 (13) | 141 (16) | 0.010 | 149 (17) | 141 (16) | 0.606 |

| Admitted from nursing home | 83 (1) | 9 (1) | 0.446 | 11(1) | 9 (1) | 0.653 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 25 (±7) | 24 (±7) | <0.001 | 24 (±7) | 24 (±7) | 0.428 |

| Past medical history | ||||||

| Heart failure hospitalization in past 6 months | 2837 (46) | 412 (48) | 0.479 | 402 (47) | 411 (48) | 0.664 |

| Hypertension | 4009 (66) | 553 (64) | 0.365 | 566 (66) | 552 (64) | 0.480 |

| Coronary artery disease | 3622 (59) | 488 (56) | 0.123 | 507(59) | 487 (57) | 0.330 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1881 (31) | 250 (29) | 0.274 | 247 (29) | 249 (29) | 0.915 |

| Coronary revascularization | 2249 (37) | 315 (36) | 0.852 | 326 (38) | 314 (36) | 0.550 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2334 (38) | 328 (38) | 0.904 | 338 (39) | 327 (38) | 0.586 |

| Cerebrovascular accidents | 934 (15) | 116 (13) | 0.154 | 121(14) | 116 (14) | 0.727 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 888 (15) | 134 (16) | 0.443 | 147 (17) | 134 (16) | 0.397 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2027 (33) | 249 (29) | 0.011 | 254 (30) | 249 (29) | 0.791 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 523 (9) | 80 (9) | 0.490 | 84 (10) | 80 (9) | 0.743 |

| Automated cardioverter defibrillator | 508 (8) | 88 (10) | 0.065 | 97 (11) | 88 (10) | 0.484 |

| Biventricular pacemaker | 321 (5) | 38 (4) | 0.289 | 40 (5) | 38 (4) | 0.817 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1648 (27) | 223 (26) | 0.477 | 236 (27) | 222 (26) | 0.445 |

| Depression | 559 (9) | 77 (9) | 0.825 | 69 (8) | 77 (9) | 0.489 |

| Admission clinical and laboratory data | ||||||

| Dyspnea at rest | 2693 (44) | 359 (42) | 0.166 | 365(42) | 358 (42) | 0.733 |

| Dyspnea on exertion | 3851 (63) | 607 (70) | <0.001 | 623 (72) | 604 (70) | 0.312 |

| Orthopnea | 1650 (27) | 313 (36) | <0.001 | 314 (36) | 310 (36) | 0.841 |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea | 1018 (17) | 182 (21) | 0.001 | 193 (22) | 180 (21) | 0.447 |

| Jugular venous pressure elevation | 1891(31) | 316 (37) | 0.001 | 322(37) | 314 (36) | 0.690 |

| Third heart sound | 728 (12) | 146 (17) | <0.001 | 120 (14) | 144 (17) | 0.108 |

| Pulmonary rales | 3830(63) | 579 (67) | 0.013 | 593 (69) | 577 (67) | 0.409 |

| Lower extremity edema | 3632 (59) | 580 (67) | <0.001 | 585 (68) | 577(67) | 0.681 |

| Serum brain natriuretic peptide (pg/mL)† | 1392 (999) | 1380(1045) | 0.730 | 1436 (1081) | 1380 (1047) | 0.312 |

| Serum troponin elevation* | 1156 (19) | 167 (19) | 0.768 | 161 (19) | 167 (19) | 0.713 |

| Discharge clinical and laboratory data | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 120 (±20) | 117(±20) | <0.001 | 117(±18) | 117(±20) | 0.802 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 66(±12) | 65 (±12) | 0.274 | 65(±12) | 65(±12) | 0.610 |

| Pulse (beats per minute) | 76(±13) | 76 (±13) | 0.518 | 75 (±13) | 75 (±13) | 0.960 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.5 (±0.5) | 1.4 (±0.5) | <0.001 | 1.4 (±0.5) | 1.4 (±0.5) | 0.235 |

| Discharge medication | ||||||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers | 4440 (73) | 715 (83) | <0.001 | 716 (83) | 712 (83) | 0.798 |

| Beta-blockers | 4314 (71) | 699 (81) | <0.001 | 692 (80) | 696 (81) | 0.808 |

| Digoxin | 2392 (39) | 420 (49) | <0.001 | 387 (45) | 417 (48) | 0.148 |

| Diuretics | 5191 (85) | 774 (90) | <0.001 | 758 (88) | 771 (89) | 0.323 |

| Hydralazine | 191 (3) | 17 (2) | 0.061 | 21 (2) | 17 (2) | 0.512 |

| Nitrates | 1556 (25) | 196 (23) | 0.079 | 189 (22) | 195 (23) | 0.728 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs | 1007 (17) | 130 (15) | 0.289 | 135 (16) | 129 (15) | 0.688 |

| Warfarin | 1718(28) | 272 (31) | 0.039 | 271 (31) | 271 (31) | 1.000 |

| Aspirin | 3224 (53) | 488 (56) | 0.039 | 514 (60) | 486 (56) | 0.172 |

| Statins | 2291 (37) | 363 (42) | 0.010 | 382 (44) | 361 (42) | 0.307 |

| Hospital beds (numbers)† | 375 (250) | 375 (300) | 0.572 | 375 (251) | 375 (300) | 0.736 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 5.7 (±5.6) | 6.2 (±4.2) | 0.009 | 6.4 (±7.2) | 6.2 (±4.2) | 0.562 |

Values are number (percentage) or mean (± standard deviation).

Values determined by local laboratories;

Values are for median (interquartile range) and p values are based on non-parametric tests comparing medians across the groups

Outcomes in the Matched Creatinine Cohort

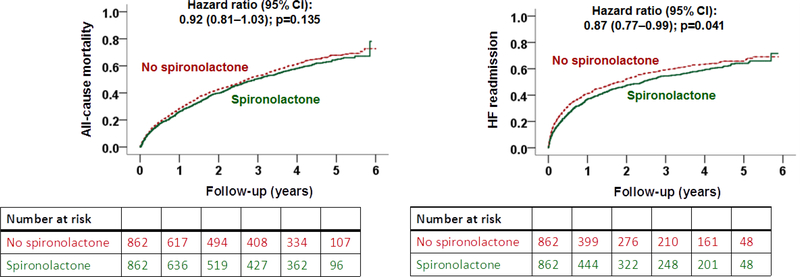

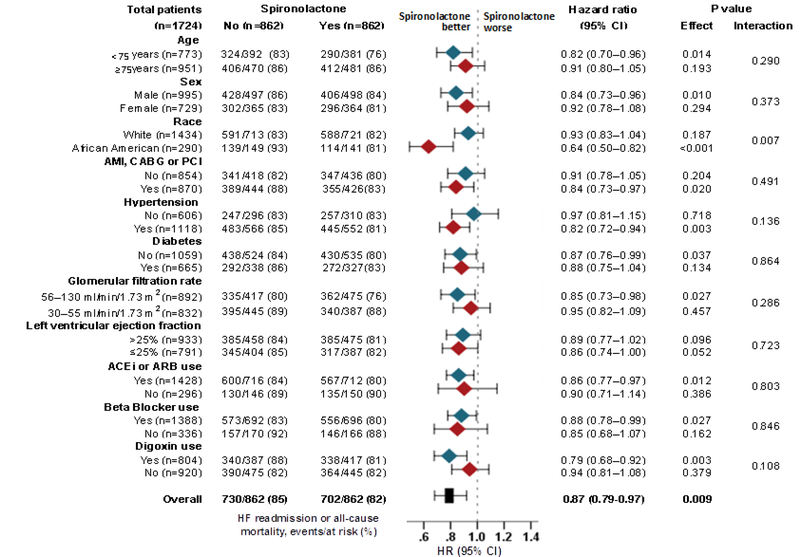

Overall, 65% (1126/1724) of the patients in our matched Creatinine Cohort died and 53% (910/1724) had a heart failure readmission during 2.9 years of median follow-up. Spironolactone use was not significantly associated with all-cause mortality (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.81–1.03; p=0.135) but was significantly associated with a lower risk of heart failure readmission (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77– 0.99; p=0.041) (Table 2 and Figure 3). Spironolactone use was also associated with a significantly lower risk of the combined endpoint of heart failure readmission or all-cause mortality (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79–0.97; p=0.009; Table 2). Of the 862 matched pairs, we were able to compare times to combined endpoint-free survival in 827 pairs, and in 53% (442/827) of those pairs, patients in the spironolactone group had a longer combined endpoint-free survival (sign-score test p=0.048). An unmeasured covariate that is a near-perfect predictor of the combined endpoint could explain away the association of spironolactone with the combined endpoint if it would also increase the odds of spironolactone use by 0.15%. This association of spironolactone with the combined endpoint was homogenous across various clinically relevant subgroups of patients except that it was significantly stronger in African Americans (Figure 4). Associations with other outcomes are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcomes by New Discharge Prescription for Spironolactone in Patients with Heart Failure with Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction ≤35%

| Outcomes | Events by spironolactone use % (n) | Hazard ratio associated with spironolactone use (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Creatinine Cohort* | No (n=862) | Yes (n=862) | |

| All-cause mortality | 67% (579) | 64% (547) | 0.92 (0.81–1.03); p=0.135 |

| Heart failure readmission | 54% (465) | 52% (445) | 0.87 (0.77–0.99); p=0.041 |

| Heart failure readmission or all-cause mortality | 85% (730) | 81% (702) | 0.87 (0.79–0.97); p=0.009 |

| All-cause readmission | 88% (756) | 86% (742) | 0.85 (0.77–0.95); p=0.002 |

| All-cause readmission or all-cause mortality | 96% (831) | 96% (823) | 0.86 (0.78–0.95); p=0.003 |

| The eGFR Cohort** | No (n=819) | Yes (n=819) | |

| All-cause mortality | 67% (554) | 62% (511) | 0.87 (0.77–0.98); p=0.025 |

| Heart failure readmission | 52% (427) | 52% (422) | 0.92 (0.80–1.05); p=0.213 |

| Heart failure readmission or all-cause mortality | 82% (674) | 81% (665) | 0.91 (0.82–1.02); p=0.095 |

| All-cause readmission | 86% (708) | 86% (703) | 0.93% (0.83–1.03); p=0.142 |

| All-cause readmission or all-cause mortality | 95% (779) | 95% (781) | 0.93 (0.85–1.03); p=0.177 |

The Creatinine Cohort is defined as admission serum creatinine ≤2.5 mg/dL for men and ≤2.0 mg/dL for women

The eGFR Cohort is defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier plots for outcomes by discharge prescription for spironolactone in patients with heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, no prior spironolactone therapy, and serum creatinine ≤2.5mg/dL for men and ≤2.0mg/dL for women (CI= confidence interval)

Figure 4.

Subgroup analyses for the combined endpoint by discharge prescription for spironolactone in 1724 propensity score-matched patients with heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, no prior spironolactone therapy, and serum creatinine ≤2.5mg/dL for men and ≤2.0mg/dL for women

Outcomes in the Matched eGFR Cohort

Overall, 65% (1065/1638) of the matched patients in our eGFR Cohort died and 52% (849/1638) had a heart failure readmission during 2.9 years of median follow-up. Spironolactone use was associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77–0.98; p=0.025; Table 2 and Figure 5). In 715 of the 819 matched pairs we were able to compare survival times, and in 53% (382/715) of those pairs, it was longer in the spironolactone group. However, this difference was not statistically significant (sign-score test p=0.067). Spironolactone had no significant association with other outcomes (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Kaplan Meier plots for outcomes by discharge prescription for spironolactone in patients with heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, no prior spironolactone therapy, and estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (CI=confidence interval)

Outcomes in the Inverse Propensity-Weighted Creatinine Cohort

Overall, 54% (7081/13,086) of the patients in our weighted pre-match Creatinine Cohort died and 47% (6166/13,086) had a heart failure readmission during 3 years of follow-up. Spironolactone use was associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89–0.98; p=0.006), heart failure readmission (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.82–0.91; p<0.001), as well as the combined endpoint of heart failure readmission or all-cause mortality 0.90 (0.87–0.94; p<0.001) at 3 years (Supplemental Table).

Outcomes in the Pre-Match Creatinine Cohort

In the pre-match cohort of 6986 patients, propensity score-adjusted HRs (95% CIs) for allcause mortality, heart failure readmission and the combined endpoint of heart failure readmission or all-cause mortality associated with spironolactone use were 0.91 (0.83–1.00; p=0.050), 0.89 (0.80– 0.98; p=0.017) and 0.91 (0.83–0.99; p=0.014), respectively. Respective multivariable-adjusted HRs (95% CIs) for mortality, heart failure readmission and the combined endpoint were 0.91 (0.83–0.99; p=0.032), 0.86 (0.78–0.96; p=0.005), and 0.89 (0.82–0.96; p=0.004), respectively.

DISCUSSION

Findings from our study demonstrate that in older patients with HFrEF who were eligible for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist therapy based on guideline recommended eligibility criteria, the use of spironolactone was associated with an 8 to 13% lower risk of all-cause mortality, heart failure readmission and the combined endpoint of heart failure readmission or all-cause mortality. These findings provide evidence of modest clinical effectiveness of spironolactone in patients with HFrEF eligible for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist therapy.

One likely explanation for a less robust effectiveness of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in the clinical practice compared with its robust efficacy in randomized controlled trials is the lack of trial-type rigorous monitoring for adverse effects in clinical practice.23–25 A higher incidence of worsening kidney function and hyperkalemia due to suboptimal monitoring may attenuate the beneficial effects of these drugs.23–27 These adverse events are likely to be more frequent and/or pronounced in older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy, who are at a higher risk of disease-disease, disease-drug, and drug-drug interactions.28 Furthermore, aldosterone antagonists are often discontinued in clinical practice in response to worsening kidney function and incident hyperkalemia,4, 29 which would be expected to attenuate between-group differences. However, when carefully monitored, in randomized controlled trials, these patients benefited from therapy with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.24–26 Another potential explanation is lack of appropriate patient selection in clinical practice.30, 31 However, patients in our study were selected using national heart failure guideline-recommended criteria for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist eligibility.3

Prior studies also reported modest or no clinical effectiveness of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in eligible patients with HFrEF.9, 32–35 However, our study is distinguished by the use of both guideline-recommended creatinine and eGFR criteria for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist eligibility and by the use of both propensity score-matching and inverse propensity score-weighted methods. The variations between our matched Creatinine and eGFR cohorts are likely a function of the modest association and small sample size. However, it is also possible that the inclusion of ineligible patients (eGFR <30) in our Creatinine Cohort may have contributed to observed variations. Despite these variations, the associations remained consistent within a narrow modest range, even in the larger inverse propensity score-weighted cohort, suggesting the presence of true, albeit modest, associations.

These findings are important as mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists continue to be underutilized in eligible patients with HFrEF. In our analysis, 6986 patients with HF and EF ≤35% were eligible for initiation of spironolactone therapy based on the serum creatinine criteria that were not receiving the drug prior to admission and 88% (6121/6986) of these patients did not receive the drug prior to hospital discharge. The modest effectiveness of spironolactone in clinical practice observed in our study generates hypothesis that a more stringent laboratory monitoring and appropriate continuation of therapy may improve the magnitude of its effectiveness. Future studies that include structured pharmacy and laboratory data may provide useful insights and preliminary data to examine if educational interventions to improve monitoring and therapy adherence may improve the effectiveness of these drugs in clinical practice. Future studies also need to examine whether new potassium-lowering agents such as patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate may improve the safety and utilization of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in eligible patients with HFrEF.36–38

Our study had several limitations. Despite our use of propensity score-matched inception cohort design, potential bias due to unmeasured confounders is possible. Findings from our sensitivity analyses suggest that the beneficial association between spironolactone use and outcomes in our study may be sensitive to an unmeasured confounder. However, such a confounder could not be strongly correlated with any of the 58 measured baseline characteristics used in our propensity score model – an unlikely possibility. We had no data on baseline serum potassium concentration, however, serum potassium has not been shown to be a predictor of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use.39 We also had no data on post-discharge adherence. In one study, over 80% of the patients initiated on spironolactone therapy filled their prescriptions within 90 days and less than 10% of those who did not receive a discharge prescription initiated the therapy post-discharge.4 Finally, our study was based on fee-for-service Medicare patients and hospital participation in OPTIMIZE-HF was voluntary, however, this patient cohort has been shown to have similar characteristics and outcomes as heart failure patients in the general Medicare population.40

CONCLUSIONS

Findings from the current study provide evidence for consistent, albeit modest, clinical effectiveness of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in hospitalized older patients with HFrEF regardless of the renal eligibility criteria used. These findings highlight the need for prospective studies to evaluate optimal monitoring and educational strategies to improve effectiveness of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with HFrEF in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE.

About 9 in 10 older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction eligible for initiation of spironolactone therapy did not receive one

Spironolactone use was associated with a modest improvement in clinical outcomes

The clinical effectiveness of spironolactone was similar regardless of whether patients were selected based on serum creatinine criteria (≤2.5 mg/dL in men and ≤2.0 mg/dL) or estimated glomerular filtration rate criteria (≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2)

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Ali Ahmed was in part supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants (R01-HL085561, R01-HL085561-S and R01-HL097047) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. OPTIMIZE-HF was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest and Disclosures: Dr. Fonarow reports consulting with Amgen, Bayer Janssen, Novartis, Medtronic, St Jude Medical and was the Principle Investigator of OPTIMIZE-HF. Dr. Pitt reports consulting with Bayer, Astra Zeneca, KBP Biosciences,* Relypsa/vifor,* and Sarfez* (*=stock options), and has a patent for site specific delivery of eplerenone to the myocardium (US Patent # 9931412). None of the other authors report any conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med.1999;341:709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtis LH, Mi X, Qualls LG, et al. Transitional adherence and persistence in the use of aldosterone antagonist therapy in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2013;165:979–986 e971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed A, Bourge RC, Fonarow GC, et al. Digoxin use and lower 30-day all-cause readmission for Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. Am J Med. 2014;127:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed A, Fonarow GC, Zhang Y, et al. Renin-angiotensin inhibition in systolic heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2012;125:399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatia V, Bajaj NS, Sanam K, et al. Beta-blocker Use and 30-day All-cause Readmission in Medicare Beneficiaries with Systolic Heart Failure. Am J Med. 2015;128:715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanam K, Bhatia V, Bajaj NS, et al. Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibition and Lower 30-Day All-Cause Readmission in Medicare Beneficiaries with Heart Failure. Am J Med. 2016;129:1067–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez AF, Mi X, Hammill BG, et al. Associations between aldosterone antagonist therapy and risks of mortality and readmission among patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA. 2012;308:2097–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:768–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam PH, Dooley DJ, Deedwania P, et al. Heart Rate and Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1861–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsimploulis A, Lam PH, Arundel C, et al. Systolic Blood Pressure and Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:288–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Kilgore ML, Arora T, et al. Design and rationale of studies of neurohormonal blockade and outcomes in diastolic heart failure using OPTIMIZE-HF registry linked to Medicare data. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:230–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel K, Fonarow GC, Kitzman DW, et al. Aldosterone antagonists and outcomes in real-world older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danaei G, Tavakkoli M, Hernan MA. Bias in observational studies of prevalent users: lessons for comparative effectiveness research from a meta-analysis of statins. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:250–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenbaum PRRD. The central role of propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin DB. Using propensity score to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2001; 2:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Zile M, et al. Renin-angiotensin inhibition in diastolic heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2013;126:150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed MI, White M, Ekundayo OJ, et al. A history of atrial fibrillation and outcomes in chronic advanced systolic heart failure: a propensity-matched study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2029–2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbaum PR. Sensitivity to hidden bias In: Rosenbaum PR, ed. Observational Studies. Vol 1 New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002:105–170. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34:3661–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PC. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal hazard ratios. Stat Med. 2013;32:2837–2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah KB, Rao K, Sawyer R, Gottlieb SS. The adequacy of laboratory monitoring in patients treated with spironolactone for congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:845–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eschalier R, McMurray JJ, Swedberg K, et al. Safety and efficacy of eplerenone in patients at high risk for hyperkalemia and/or worsening renal function: analyses of the EMPHASIS-HF study subgroups (Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization And SurvIval Study in Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1585–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossignol P, Dobre D, McMurray JJ, et al. Incidence, determinants, and prognostic significance of hyperkalemia and worsening renal function in patients with heart failure receiving the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist eplerenone or placebo in addition to optimal medical therapy: results from the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF). Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vardeny O, Wu DH, Desai A, et al. Influence of baseline and worsening renal function on efficacy of spironolactone in patients With severe heart failure: insights from RALES (Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2082–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper LB, Hammill BG, Peterson ED, et al. Characterization of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Therapy Initiation in High-Risk Patients With Heart Failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanlon JT, Perera S, Newman AB, et al. Potential drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in well-functioning community-dwelling older adults. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42:228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trevisan M, de Deco P, Xu H, et al. Incidence, predictors and clinical management of hyperkalaemia in new users of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; 10.1002/ejhf.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bozkurt B, Agoston I, Knowlton AA. Complications of inappropriate use of spironolactone in heart failure: when an old medicine spirals out of new guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, et al. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inampudi C, Parvataneni S, Morgan CJ, et al. Spironolactone use and higher hospital readmission for Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction <45%, and estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 ml/min/1.73 m(2.). Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:79–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam PH, Dooley DJ, Inampudi C, et al. Lack of evidence of lower 30-day all-cause readmission in Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction discharged on spironolactone. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:462–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lund LH, Svennblad B, Melhus H, Hallberg P, Dahlstrom U, Edner M. Association of spironolactone use with all-cause mortality in heart failure: a propensity scored cohort study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee KK, Shilane D, Hlatky MA, Yang J, Steimle AE, Go AS. Effectiveness and safety of spironolactone for systolic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:1427–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pitt B, Bakris GL, Bushinsky DA, et al. Effect of patiromer on reducing serum potassium and preventing recurrent hyperkalaemia in patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease on RAAS inhibitors. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:1057–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarwar CM, Papadimitriou L, Pitt B, et al. Hyperkalemia in Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1575–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weir MR, Bushinsky DA, Benton WW, et al. Effect of Patiromer on Hyperkalemia Recurrence in Older Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Taking RAAS Inhibitors. Am J Med. 2018;131:555–564e553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savarese G, Carrero JJ, Pitt B, et al. Factors associated with underuse of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of 11 215 patients from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1182.[Epub ahead of print]. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis LH, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, et al. Representativeness of a national heart failure quality-of-care registry: comparison of OPTIMIZE-HF and non-OPTIMIZE-HF Medicare patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.