Abstract

Background

Critically ill people may lose fluid because of serious conditions, infections (e.g. sepsis), trauma, or burns, and need additional fluids urgently to prevent dehydration or kidney failure. Colloid or crystalloid solutions may be used for this purpose. Crystalloids have small molecules, are cheap, easy to use, and provide immediate fluid resuscitation, but may increase oedema. Colloids have larger molecules, cost more, and may provide swifter volume expansion in the intravascular space, but may induce allergic reactions, blood clotting disorders, and kidney failure. This is an update of a Cochrane Review last published in 2013.

Objectives

To assess the effect of using colloids versus crystalloids in critically ill people requiring fluid volume replacement on mortality, need for blood transfusion or renal replacement therapy (RRT), and adverse events (specifically: allergic reactions, itching, rashes).

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and two other databases on 23 February 2018. We also searched clinical trials registers.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs of critically ill people who required fluid volume replacement in hospital or emergency out‐of‐hospital settings. Participants had trauma, burns, or medical conditions such as sepsis. We excluded neonates, elective surgery and caesarean section. We compared a colloid (suspended in any crystalloid solution) versus a crystalloid (isotonic or hypertonic).

Data collection and analysis

Independently, two review authors assessed studies for inclusion, extracted data, assessed risk of bias, and synthesised findings. We assessed the certainty of evidence with GRADE.

Main results

We included 69 studies (65 RCTs, 4 quasi‐RCTs) with 30,020 participants. Twenty‐eight studied starch solutions, 20 dextrans, seven gelatins, and 22 albumin or fresh frozen plasma (FFP); each type of colloid was compared to crystalloids.

Participants had a range of conditions typical of critical illness. Ten studies were in out‐of‐hospital settings. We noted risk of selection bias in some studies, and, as most studies were not prospectively registered, risk of selective outcome reporting. Fourteen studies included participants in the crystalloid group who received or may have received colloids, which might have influenced results.

We compared four types of colloid (i.e. starches; dextrans; gelatins; and albumin or FFP) versus crystalloids.

Starches versus crystalloids

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that there is probably little or no difference between using starches or crystalloids in mortality at: end of follow‐up (risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 1.09; 11,177 participants; 24 studies); within 90 days (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.14; 10,415 participants; 15 studies); or within 30 days (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.09; 10,135 participants; 11 studies).

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that starches probably slightly increase the need for blood transfusion (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.39; 1917 participants; 8 studies), and RRT (RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.48; 8527 participants; 9 studies). Very low‐certainty evidence means we are uncertain whether either fluid affected adverse events: we found little or no difference in allergic reactions (RR 2.59, 95% CI 0.27 to 24.91; 7757 participants; 3 studies), fewer incidences of itching with crystalloids (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.82; 6946 participants; 2 studies), and fewer incidences of rashes with crystalloids (RR 1.61, 95% CI 0.90 to 2.89; 7007 participants; 2 studies).

Dextrans versus crystalloids

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that there is probably little or no difference between using dextrans or crystalloids in mortality at: end of follow‐up (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.11; 4736 participants; 19 studies); or within 90 days or 30 days (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.12; 3353 participants; 10 studies). We are uncertain whether dextrans or crystalloids reduce the need for blood transfusion, as we found little or no difference in blood transfusions (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.10; 1272 participants, 3 studies; very low‐certainty evidence). We found little or no difference in allergic reactions (RR 6.00, 95% CI 0.25 to 144.93; 739 participants; 4 studies; very low‐certainty evidence). No studies measured RRT.

Gelatins versus crystalloids

We found low‐certainty evidence that there may be little or no difference between gelatins or crystalloids in mortality: at end of follow‐up (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.08; 1698 participants; 6 studies); within 90 days (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.09; 1388 participants; 1 study); or within 30 days (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.16; 1388 participants; 1 study). Evidence for blood transfusion was very low certainty (3 studies), with a low event rate or data not reported by intervention. Data for RRT were not reported separately for gelatins (1 study). We found little or no difference between groups in allergic reactions (very low‐certainty evidence).

Albumin or FFP versus crystalloids

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that there is probably little or no difference between using albumin or FFP or using crystalloids in mortality at: end of follow‐up (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.06; 13,047 participants; 20 studies); within 90 days (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.04; 12,492 participants; 10 studies); or within 30 days (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.06; 12,506 participants; 10 studies). We are uncertain whether either fluid type reduces need for blood transfusion (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.80; 290 participants; 3 studies; very low‐certainty evidence). Using albumin or FFP versus crystalloids may make little or no difference to the need for RRT (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.27; 3028 participants; 2 studies; very low‐certainty evidence), or in allergic reactions (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.33; 2097 participants, 1 study; very low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Using starches, dextrans, albumin or FFP (moderate‐certainty evidence), or gelatins (low‐certainty evidence), versus crystalloids probably makes little or no difference to mortality. Starches probably slightly increase the need for blood transfusion and RRT (moderate‐certainty evidence), and albumin or FFP may make little or no difference to the need for renal replacement therapy (low‐certainty evidence). Evidence for blood transfusions for dextrans, and albumin or FFP, is uncertain. Similarly, evidence for adverse events is uncertain. Certainty of evidence may improve with inclusion of three ongoing studies and seven studies awaiting classification, in future updates.

Plain language summary

Colloids or crystalloids for fluid replacement in critically people

Background

Critically ill people may lose large amounts of blood (because of trauma or burns), or have serious conditions or infections (e.g. sepsis); they require additional fluids urgently to prevent dehydration or kidney failure. Colloids and crystalloids are types of fluids that are used for fluid replacement, often intravenously (via a tube straight into the blood).

Crystalloids are low‐cost salt solutions (e.g. saline) with small molecules, which can move around easily when injected into the body.

Colloids can be man‐made (e.g. starches, dextrans, or gelatins), or naturally occurring (e.g. albumin or fresh frozen plasma (FFP)), and have bigger molecules, so stay in the blood for longer before passing to other parts of the body. Colloids are more expensive than crystalloids. We are uncertain whether they are better than crystalloids at reducing death, need for blood transfusion or need for renal replacement therapy (filtering the blood, with or without dialysis machines, if kidneys fail) when given to critically ill people who need fluid replacement.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to February 2018. We searched the medical literature and identified 69 relevant studies with 30,020 critically ill participants who were given fluid replacement in hospital or in an emergency out‐of‐hospital setting. Studies compared colloids (starches; dextrans; gelatins; or albumin or FFP) with crystalloids.

Key results

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that using colloids (starches; dextrans; or albumin or FFP) compared to crystalloids for fluid replacement probably makes little or no difference to the number of critically ill people who die within 30 or 90 days, or by the end of study follow‐up. We also found low‐certainty evidence that using gelatins or crystalloids may make little or no difference to the number of deaths within each of these time points.

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that using starches probably slightly increases the need for blood transfusion. However, we are uncertain whether using other types of colloids, compared to crystalloids, makes a difference to whether people need a blood transfusion because the certainty of the evidence is very low.

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that using starches for fluid replacement probably slightly increases the need for renal replacement therapy. Using albumin or FFP compared to crystalloids may make little or no difference to the need for renal replacement therapy. One study comparing gelatins did not report results for renal replacement therapy according to the type of fluid given, and no studies comparing dextrans assessed renal replacement therapy.

Few studies reported adverse events (specifically, allergic reactions, itching, or rashes), so we are uncertain whether either fluid type causes fewer adverse events (very low‐certainty evidence). We found little or no difference between starches or crystalloids in allergic reactions, but fewer participants given crystalloids reported itching or rashes. We found little or no difference in allergic reactions for the use of dextrans (four studies), gelatins (one study), and albumin or FFP (one study).

Certainty of the evidence

Some study authors did not report study methods clearly and many did not register their studies before they started, so we could not be certain whether the study outcomes were decided before or after they saw the results. Also, we found that some people who were given crystalloids may also have had colloids, which might have affected the results. For some outcomes, we had very few studies, which reduced our confidence in the evidence.

Conclusions

Using colloids (starches; dextrans; or albumin or FFP) compared to crystalloids for fluid replacement probably makes little or no difference to the number of critically ill people who die. It may make little or no difference to the number of people who die if gelatins or crystalloids are used for fluid replacement.

Starches probably increase the need for blood transfusion and renal replacement therapy slightly. Using albumin or FFP may make little or no difference to the need for renal replacement therapy. We are uncertain whether using dextrans, albumin or FFP, or crystalloids affects the need for blood transfusion. Similarly, we are uncertain if colloids or crystalloids increase the number of adverse events. Results from ongoing studies may increase our confidence in the evidence in future.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Critically ill people may experience excessive fluid loss, and hypovolaemia, because of haemorrhage from serious injury or burns, or because of critical illnesses, which lead to dehydration, vomiting, or diarrhoea. Fluid loss may lead to mortality and morbidity, for example, haemorrhage accounts for almost half of deaths in the first 24 hours after traumatic injury (Geeraedts 2009; Kauvar 2006), and, worldwide, traumatic injury is a leading cause of death (Peden 2002). Changes in body fluid balance may also lead to acute kidney injury or failure.

Description of the intervention

Fluid resuscitation is one of the most important strategies for early management of critically ill people (Rhodes 2016; Rossaint 2016). Fluids used for this purpose are crystalloids or colloids.

Crystalloids, such as saline and Ringer's lactate, are solutions of salt, water and minerals, and are commonly used in the clinical setting. They have small molecules, and, when used intravenously, they are effective as volume expanders. They may have an isotonic or hypertonic composition, which could affect the distribution of fluid in the body; for example, because hypertonic crystalloids lower plasma osmolality they cause water movement from the intravascular to the extravascular space, and a lower volume may be required for fluid resuscitation (Coppola 2014). They are cheap and easy to use, with few side effects. However, because they move more easily into the extravascular space, their use may increase oedema (Coppola 2014). The composition of the crystalloid may not affect clinical outcomes; recent reviews have examined the possible effect of hypertonic solutions (Shrum 2016), and compared buffered with non‐buffered fluids (Bampoe 2017), but have not found important clinical differences.

Colloids, which are suspended in crystalloid solutions, are similarly given for the purpose of volume expansion. Different types of colloids may be grouped as synthetic or semi‐synthetic, for example: starches, dextrans, gelatins; or naturally occurring, such as human albumin or fresh frozen plasma (FFP). These colloid solutions have different pharmacokinetic properties that may affect plasma expansion in different ways (Orbegozo 2015). All colloids have a larger molecular weight than crystalloids and do not cross the endothelium into the interstitial fluid easily. This means that they stay in the intervascular space for longer than crystalloids, provide the benefit of rapid plasma expansion, and can correct colloidal osmotic pressure (McClelland 1998). Colloids are a more expensive fluid replacement option, and they may have adverse effects such as allergic reactions, blood clotting disorders, and kidney failure (Bailey 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

This is an update of a Cochrane Review that was first published in 1997 and has been updated several times since. The most recent published version of this Cochrane Review looked at the effect of colloids and crystalloids on mortality at the end of study follow‐up (Perel 2013). Meta‐analysis demonstrated no evidence of a difference in mortality when participants were given dextrans, gelatins, albumin or FFP, versus crystalloids. However, the review found evidence of an increase in mortality with the use of starches. Whilst some advise against using starches as a first line of resuscitation (Reinhart 2012), this is not consistent with findings from large randomised trials (Myburgh 2012; Perner 2012), nor with some other systematic reviews (He 2015; Qureshi 2016).

It is possible that results from Perel 2013 could have been confounded by the inclusion of a wider variety of participants in need of fluid resuscitation. In this review, we have sought to reduce heterogeneity in a critically ill population as much as possible by excluding participants who were scheduled for elective surgery; whilst these participants may require fluid replacement during perioperative management to reduce the risk of hypovolaemia, they are less likely to be critically ill at the point of randomisation ‐ even elderly people undergoing semi‐urgent surgery can seldom be seen as critically ill (Lewis 2016).

Also, our aim was to explore other effects of colloids or crystalloids on resuscitation. In particular we aimed to consider whether colloids or crystalloids affect the number of people who require blood transfusion, and the effect on renal function by assessing whether more or fewer critically ill people are likely to need renal replacement therapy after fluid resuscitation interventions, because evidence suggests that use of some types of fluids may increase these risks (Zarychanski 2013). In addition, we considered the effect of type of fluids on adverse events (allergic reactions, itching or pruritis, and rashes) that have been reported in trials (e.g. in Myburgh 2012).

Objectives

To assess the effect of using colloids versus crystalloids in critically ill people requiring fluid volume replacement on mortality, need for blood transfusion or renal replacement therapy, and adverse events (specifically: allergic reactions, itching, rashes).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included parallel‐design randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and quasi‐randomised studies (e.g. studies in which the method of assignment is based on alternation, date of birth or medical record number). We excluded randomised cross‐over trials. We excluded study reports that had been retracted after publication.

Types of participants

We included participants who required fluid volume replacement in hospital or in an emergency out‐of‐hospital setting. We included participants who were described as critically ill, and participants who required fluid volume replacement as a result of trauma, burns, or medical conditions such as sepsis.

We excluded studies of participants undergoing elective surgical procedures. We excluded neonates, and women undergoing caesarean section.

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared a colloid (suspended in any crystalloid solution) versus a crystalloid. We excluded studies in which a colloid was given in both groups of participants.

We included the following colloids: starches; dextrans; gelatins; albumin or fresh frozen plasma (FFP). We included crystalloids of different electrolyte compositions (isotonic or hypertonic).

We considered each colloid type as a separate comparison group. Therefore, we compared:

starches versus crystalloids;

dextrans versus crystalloids;

gelatins versus crystalloids;

albumin or FFP versus crystalloids.

We excluded studies in which the colloid was given to replace a known nutritional deficiency (for example, given for hypoalbuminaemia), or was given as a preloading solution before surgery. We excluded studies in which fluids were given to people with head injury to control intracranial pressure.

Types of outcome measures

We did not exclude studies that did not measure or report review outcomes.

We collected outcome data for mortality from any cause at end‐of‐study follow‐up; we included data for this outcome for which the time point was not reported, and for which the time point was reported as 'before hospital discharge', 'within the ICU', or within 30 days, 60 days, or 90 days. In addition, we collected mortality data that were clearly reported within 90 days, or within 30 days. Our secondary outcomes assessed the effectiveness of the resuscitation fluids and included need for transfusion of any blood product, and need for renal replacement therapy. In addition, we collected data for outcomes of adverse events, specifically: allergic reactions, itching/pruritis, and rashes.

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality (at end of follow‐up)

All‐cause mortality (within 90 days)

All‐cause mortality (within 30 days)

Secondary outcomes

Transfusion of blood products

Renal replacement therapy

Adverse events (allergic reactions, itching, and rashes)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We developed subject‐specific search strategies in consultation with the Cochrane Injuries Group Information Specialist. We identified RCTs through literature searching of the following electronic databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 2) (which contains the Cochrane Injuries Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 23 February 2018) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 23 February 2018) (Appendix 2);

Embase Ovid (1974 to 23 February 2018) (Appendix 3);

PubMed (1948 to 23 February 2018) (Appendix 4);

Web of Science (Core Collection, 1970 to 23 February 2018) (Appendix 5);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 13 April 2018) (Appendix 6);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 13 April 2018) (Appendix 7)

OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) (www.opengrey.eu; searched 12 April 2018) (Appendix 8).

This review was an update of a previous Cochrane Review (Perel 2013). However, because we made changes to the inclusion criteria and increased the outcome measures, we ran all the searches from database inception.

Searching other resources

We conducted citation searching of identified included studies published from 2013 onwards in Web of Science (apps.webofknowledge.com) (12 April 2018). We scanned reference lists of relevant systematic reviews (identified during database searches) to search for additional trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (Sharon Lewis (SL) and either: Michael Pritchard (MP), Andrew Butler (AB), or David Evans (DE)) independently completed all data collection and analyses before comparing results and reaching consensus. We consulted a third review author (Andrew Smith (AS)) to resolve conflicts if necessary.

Selection of studies

We used Endnote reference management software to collate the results of the searches and to remove duplicates. We used Covidence software to screen titles and abstracts and identify potentially relevant studies. We sourced the full texts of all potentially relevant studies and assessed whether the studies met the review inclusion criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). We reviewed abstracts at this stage and included these in the review only if they provided sufficient information to assess eligibility.

We reassessed eligibility of studies included in the last version of the review (Perel 2013), because of changes made to review inclusion criteria.

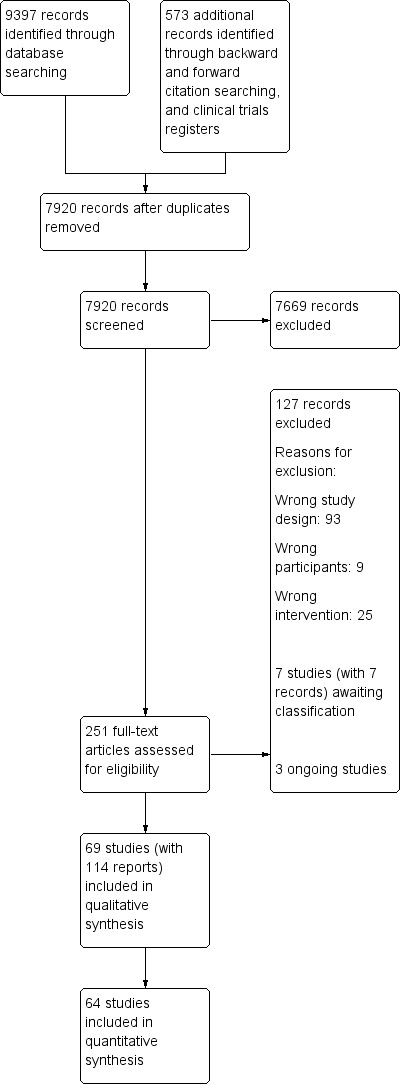

We recorded the number of papers retrieved at each stage and reported this in a PRISMA flow chart (Liberati 2009; Figure 1). We reported in the review brief details of closely related but excluded papers.

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

We used Covidence software to extract data from individual studies. A basic template for data extraction forms is available at www.covidence.org. We adapted this template to include the following information.

Methods ‐ type of study design; setting; country; dates of study; funding sources

Participants ‐ number of participants randomised to each group, number of lost participants, and number of analysed participants, participant condition or reason for fluid resuscitation. Baseline characteristics to include: age, gender, weight or body mass index, blood pressure, prognostic or illness severity scores (American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) I or II, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS))

Interventions ‐ details of colloid and crystalloid (concentration of solution, volume, and rate of administration), additional relevant patient management

Outcomes ‐ all outcomes reported by study authors, relevant outcomes (including time of measurement for mortality)

Outcome data ‐ results of outcome data

Because of changes in reporting expectations in Cochrane Reviews ‐ the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) (Higgins 2016) ‐ since the last version of the review (Perel 2013), we also used Covidence to re‐conduct data extraction on studies included in the last version of the review.

We considered the applicability of information from individual studies and the generalisability of data to our intended study population (i.e. the potential for indirectness in the review). If we found associated publications from the same study, we created a composite data set based on all eligible publications.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SL and MP, AB, or DE) independently assessed study quality, study limitations, and the extent of potential bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2017). We completed 'Risk of bias' assessment only for studies that reported the review outcomes.

We assessed the following domains.

Sequence generation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors (performance bias and detection bias)

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)

Baseline characteristics

Other bias

We made separate judgements for performance and detection bias for mortality and for blood transfusion/renal replacement therapy/adverse events.

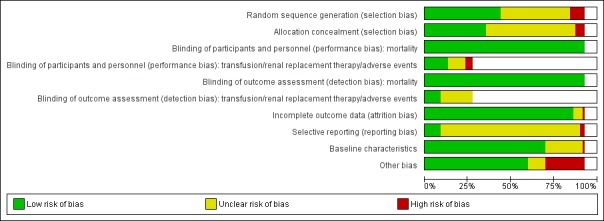

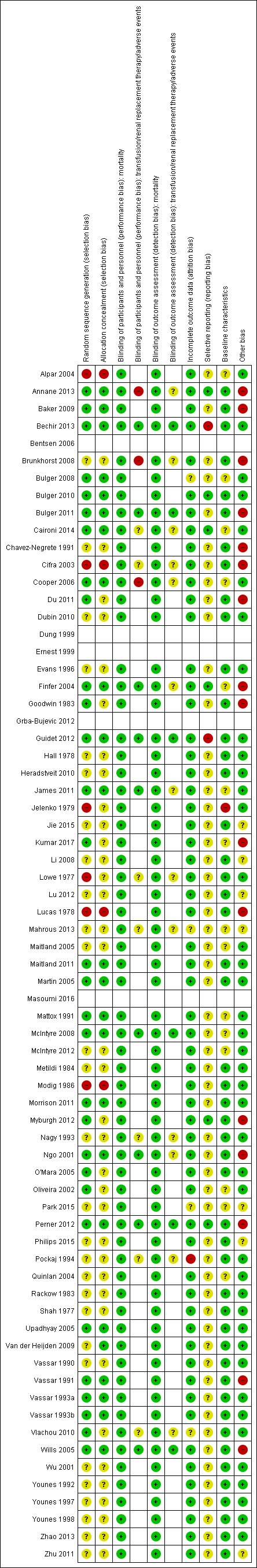

For each domain, we judged whether study authors had made sufficient attempts to minimise bias in their study design. We made judgements using three measures, high, low and unclear risk of bias. We recorded this decision in 'Risk of bias' tables and present a 'Risk of bias' graph and summary figure (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. We did not make judgements for studies that did not report outcomes of interest in the review, which are indicated by blank spaces

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. We did not make judgements for studies that did not report outcomes of interest in the review, which are indicated by blank spaces

Because of changes in reporting expectations in Cochrane Reviews (MECIR; Higgins 2016) since the last version of the review, we also completed a 'Risk of bias' assessment on all studies included in Perel 2013.

Measures of treatment effect

We collected dichotomous data for each outcome measure (the number of participants who had died, the number of participants who required transfusion of blood products, the number of participants who required renal replacement therapy, and the number of participants who had adverse events).

Unit of analysis issues

We reported data separately according to type of colloid (starches; dextrans; gelatins; albumin or FFP).

For multi‐arm studies that included more than one of the same type of study fluid (e.g. two groups of starches combined with an isotonic or a hypertonic crystalloid), we combined data from study groups in the same analysis only when it was appropriate and when it did not include double‐counting of participants.

In subgroup analysis, in which studies were grouped by different types of crystalloid solution, it was not always appropriate to combine data from multi‐arm study groups. If we had included multi‐arm studies in subgroup analysis, we planned to use the halving method to avoid unit of analysis issues (Deeks 2017).

Dealing with missing data

We assessed whether all measured outcomes had been reported by study authors by comparing, when possible, published reports with protocols or clinical trials register documents that had been prospectively published.

We assessed whether all randomised participants had been included in outcome data. In the absence of an explanation for loss of data, we used the 'Risk of bias' tool to judge whether a study was at high risk of attrition bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed whether evidence of inconsistency was apparent in our results by considering heterogeneity. We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by comparing similarities in our included studies between study designs, participants, and interventions, using data collected during data extraction (Data extraction and management). We assessed statistical heterogeneity by calculating the Chi² test and I² statistic (Higgins 2003), and judged any heterogeneity using values of I² greater than 60% and Chi² P value of 0.05 or less to indicate moderate to substantial statistical heterogeneity (Deeks 2017).

As well as looking at statistical results, we considered point estimates and overlap of confidence intervals (CIs). If CIs overlap, then results are more consistent. Combined studies may show a large consistent effect but with significant heterogeneity. Therefore, we planned to interpret heterogeneity with caution (Guyatt 2011a).

Assessment of reporting biases

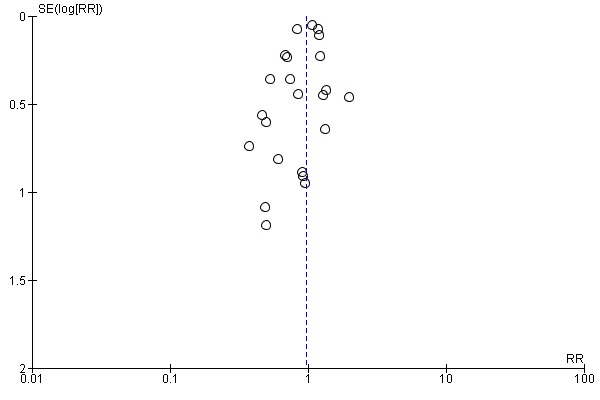

We attempted to source published protocols for each of our included studies by using clinical trials registers. We compared protocols or clinical trials register documents that had been prospectively published with study results to assess the risk of selective reporting. We generated a funnel plot to assess risk of publication bias in the review, for outcomes in which we identified more than 10 studies (Sterne 2017). An asymmetrical funnel plot may suggest publication of only positive results (Egger 1997). We included funnel plot figures for the primary outcome: all‐cause mortality (at the end of follow‐up) (Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6).

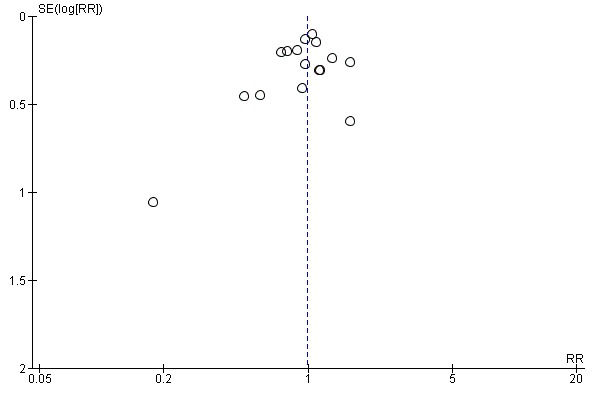

4.

Funnel plot of comparison 1. Starches vs crystalloid, outcome: 1.1 mortality at end of follow‐up

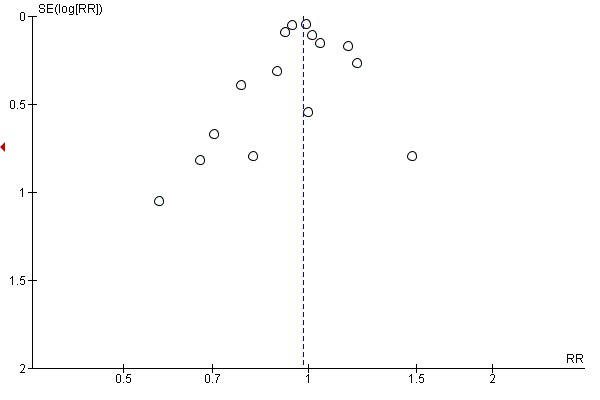

5.

Funnel plot of comparison 2. Dextrans vs crystalloid, outcome: 2.1 mortality at end of follow‐up

6.

Funnel plot of comparison 4. Albumin and FFP vs crystalloid, outcome: 4.1 mortality at end of follow‐up

Data synthesis

We completed meta‐analysis of outcomes in which we had comparable effect measures for more than one study, and when measures of clinical and methodological heterogeneity indicated that pooling was appropriate.

We presented results according to type of colloid (starches; dextrans; gelatins; albumin or FFP) as four separate comparisons (see Types of interventions).

We used the statistical calculator in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) to calculate risk ratios (RR) using the Mantel‐Haenszel model (Review Manager 2014). We used a random‐effects statistical model that accounted for the variation amongst participant groups in the review. We calculated CIs at 95% and used a P value of 0.05 or less to judge whether a result was statistically significant. We considered imprecision in the results of analyses by assessing the CI around an effect measure; a wide CI would suggest a higher level of imprecision in our results. A small number of identified studies may also reduce precision (Guyatt 2011b).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We explored potential differences in the tonicity of crystalloid solutions that had been used with colloids or used as the comparative crystalloid. This was an a priori subgroup analysis included in the previous version of the review (Perel 2013). We used the calculator in RevMan 5 to perform subgroup analysis, comparing the Chi² and P value for the test for subgroup differences; we interpreted a P value of less than 0.05 as being indicative of a difference between subgroups. We conducted subgroup analysis when data were available for more than 10 studies (Deeks 2017). We considered subgroup analysis only for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality (at end of follow‐up)) for each of our comparisons (starches; dextrans; gelatins; albumin or FFP). Subgroups were as follows.

-

Tonicity of crystalloid solution:

colloid + isotonic crystalloid versus isotonic crystalloid;

colloid + hypertonic crystalloid versus isotonic crystalloid;

colloid + isotonic crystalloid versus hypertonic crystalloid;

colloid + hypertonic crystalloid versus hypertonic crystalloid.

Sensitivity analysis

We explored the potential effects of decisions made as part of the review process as follows.

We excluded all studies that we judged to be at high or unclear risk of selection bias.

We excluded studies in which we noted that some participants in the crystalloid group were given, or may have been given, additional colloids.

We conducted meta‐analysis using the alternative meta‐analytical effects model (fixed‐effect).

We used alternative data for individual studies in which we noted discrepancies in reported data.

We conducted sensitivity analysis on the primary outcome: all‐cause mortality (at end of follow‐up).

'Summary of findings' table and GRADE

We used the GRADE system to assess the certainty of the body of evidence associated with the following outcomes (Guyatt 2008).

All‐cause mortality (at end of follow‐up)

All‐cause mortality (within 90 days)

All‐cause mortality (within 30 days)

Transfusion of blood products

Renal replacement therapy

Adverse events (allergic reactions, itching, rashes)

The GRADE approach appraises the certainty of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. Evaluation of the certainty of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias, directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias.

We constructed four 'Summary of findings' tables using the GRADEpro GDT software to create 'Summary of findings' tables for the following comparisons in this review (GRADEpro GDT 2015).

Starches versus crystalloids

Dextrans versus crystalloids

Gelatins versus crystalloids

Albumin or FFP versus crystalloids

One review author (SL) completed the table in consultation with a second author (MP).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We screened 7920 titles and abstracts from database searches, forward and backward citation searches, and clinical trials register searches. We assessed 248 full‐text reports for eligibility. See Figure 1.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

We included 69 studies; 42 of these had been included in the previous version of the review (Perel 2013), and 27 were included for the first time in this update.

These 69 studies comprised a total of 114 publications, and included 30,020 participants (Alpar 2004; Annane 2013; Baker 2009; Bechir 2013; Bentsen 2006; Brunkhorst 2008; Bulger 2008; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Caironi 2014; Chavez‐Negrete 1991; Cifra 2003; Cooper 2006; Du 2011; Dubin 2010; Dung 1999; Ernest 1999; Evans 1996; Finfer 2004; Goodwin 1983; Grba‐Bujevic 2012; Guidet 2012; Hall 1978; Heradstveit 2010; James 2011; Jelenko 1979; Jie 2015; Kumar 2017; Li 2008; Lowe 1977; Lu 2012; Lucas 1978; Mahrous 2013; Maitland 2005; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; Masoumi 2016; Mattox 1991; McIntyre 2008; McIntyre 2012; Metildi 1984; Modig 1986; Morrison 2011; Myburgh 2012; Nagy 1993; Ngo 2001; O'Mara 2005; Oliveira 2002; Park 2015; Perner 2012; Philips 2015; Pockaj 1994; Quinlan 2004; Rackow 1983; Shah 1977; Upadhyay 2005; Van der Heijden 2009; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b; Vlachou 2010; Wills 2005; Wu 2001; Younes 1992; Younes 1997; Younes 1998; Zhao 2013; Zhu 2011).

Four studies were quasi‐randomised (Alpar 2004; Cifra 2003; Lucas 1978; Modig 1986), and the remaining studies were RCTs.

We included three studies for which we could only source the abstract (Mahrous 2013; Park 2015; Philips 2015); we sourced the full text of all remaining studies.

Study population

Participants had a wide variety of diagnoses for which fluid volume resuscitation was required, including: trauma, burns, and medical conditions such as sepsis and hypovolaemic shock. We have listed each study with the primary participant conditions in Table 5.

1. Summary of participant conditions.

* included for more than one type of condition

ALI: acute lung injury ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome ICU: intensive care unit

Seven studies recruited only children (Cifra 2003; Dung 1999; Maitland 2005; Maitland 2011; Ngo 2001; Upadhyay 2005; Wills 2005), and two studies recruited children and adults (Hall 1978; Wu 2001). We noted that some studies reported an inclusion criteria of over 15 years of age (Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011), over 16 years of age (Baker 2009; Bechir 2013; Evans 1996; Masoumi 2016; Mattox 1991; Morrison 2011), or over 17 years of age (Bulger 2008); using mean ages reported by study authors, most participants in these studies were adults over 18 years of age. All remaining studies included only adult participants.

Study setting

Nineteen studies were multicentre studies (Annane 2013; Baker 2009; Brunkhorst 2008; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Caironi 2014; Cooper 2006; Dubin 2010; Finfer 2004; Guidet 2012; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; Mattox 1991; McIntyre 2008; McIntyre 2012; Morrison 2011; Myburgh 2012; Perner 2012; Quinlan 2004); the remaining studies were single‐centre studies.

Ten studies were based in an out‐of‐hospital setting before transition to an emergency or trauma department within a hospital (Baker 2009; Bulger 2008; Bulger 2010; Caironi 2014; Grba‐Bujevic 2012; Mattox 1991; Morrison 2011; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b); the remaining studies were based in a hospital.

Most single‐ or multicentre studies were conducted in one of the following countries: the USA (Bulger 2008; Goodwin 1983; Jelenko 1979; Lowe 1977; Lucas 1978; Martin 2005; Mattox 1991; Metildi 1984; Nagy 1993; O'Mara 2005; Pockaj 1994; Quinlan 2004; Rackow 1983; Shah 1977; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b); Canada (Baker 2009; Cooper 2006; Ernest 1999; McIntyre 2008; McIntyre 2012; Morrison 2011); China (Du 2011; Jie 2015; Li 2008; Lu 2012; Zhao 2013; Zhu 2011); Brazil (Oliveira 2002; Park 2015; Younes 1992; Younes 1997; Younes 1998); India (Kumar 2017; Philips 2015; Upadhyay 2005); Vietnam (Dung 1999; Ngo 2001; Wills 2005); Norway (Bentsen 2006; Heradstveit 2010); South Africa (Evans 1996; James 2011); the UK (Alpar 2004; Vlachou 2010); Argentina (Dubin 2010); Croatia (Grba‐Bujevic 2012); Denmark (Hall 1978); Germany (Brunkhorst 2008); Iran (Masoumi 2016); Italy (Caironi 2014); Kenya (Maitland 2005); Mexico (Chavez‐Negrete 1991); the Netherlands (Van der Heijden 2009); the Philippines (Cifra 2003); Saudi Arabia (Mahrous 2013); Sweden (Modig 1986); Switzerland (Bechir 2013); Taiwan (Wu 2001).

Eight multicentre studies were conducted in more than one country (Annane 2013: France, Belgium, Canada, Algeria and Tunisia; Perner 2012: Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Norway; Maitland 2011: Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda; Bulger 2010 and Bulger 2011: USA and Canada; Finfer 2004 and Myburgh 2012: Australia and New Zealand; Guidet 2012: France and Germany).

Interventions and comparison

Nine studies were multi‐arm studies that included more than one colloid solution or more than one crystalloid solution or more than one of each type of solution (Dung 1999; Li 2008; Ngo 2001; Rackow 1983; Van der Heijden 2009; Vassar 1993b; Wills 2005; Zhao 2013; Zhu 2011). One study compared colloids with crystalloids and the type of colloid or crystalloid was at the discretion of the physician (Annane 2013); types of colloids in this study were starches, gelatins, and albumin.

Colloids

Twenty‐eight studies used a starch solution (hydroxyethyl starch, hetastarch, or pentastarch) for fluid resuscitation (Annane 2013; Bechir 2013; Bentsen 2006; Brunkhorst 2008; Cifra 2003; Du 2011; Dubin 2010; Grba‐Bujevic 2012; Guidet 2012; Heradstveit 2010; James 2011; Jie 2015; Kumar 2017; Li 2008; Lu 2012; Mahrous 2013; Masoumi 2016; McIntyre 2008; Myburgh 2012; Nagy 1993; Perner 2012; Rackow 1983; Van der Heijden 2009; Vlachou 2010; Wills 2005; Younes 1998; Zhao 2013; Zhu 2011). Of these, sixteen studies did not describe what they used as a suspension solution (Annane 2013; Cifra 2003; Dubin 2010; James 2011; Jie 2015; Li 2008; Lu 2012; Mahrous 2013; Nagy 1993; Perner 2012; Rackow 1983; Van der Heijden 2009; Vlachou 2010; Younes 1998; Zhao 2013; Zhu 2011). Five studies used a starch solution combined with an isotonic crystalloid solution, which was normal saline (Brunkhorst 2008; Masoumi 2016; McIntyre 2008; Myburgh 2012; Wills 2005), and seven studies used a starch solution combined with a hypertonic crystalloid solution, which was hypertonic saline (Bentsen 2006; Grba‐Bujevic 2012; Heradstveit 2010; Li 2008; Zhu 2011), or Ringer's lactate (Bechir 2013; Du 2011). Two studies did not specify the type of crystalloid solution that was combined with a starch (Guidet 2012; Kumar 2017), and one multi‐arm study also included a starch combined with glutamine (Zhao 2013).

Twenty studies used dextrans for fluid resuscitation (Alpar 2004; Baker 2009; Bulger 2008; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Chavez‐Negrete 1991; Dung 1999; Hall 1978; Mattox 1991; Modig 1986; Morrison 2011; Ngo 2001; Oliveira 2002; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b; Wills 2005; Younes 1992; Younes 1997). Two studies did not describe what they used as a suspension solution in dextran 70 (Modig 1986; Ngo 2001); Ngo 2001 gave Ringer's lactate to all participants after an initial infusion of dextran 70. Three studies used dextran 70 (which has relative molecular mass of 70,000) combined with an isotonic crystalloid solution which was normal saline (Dung 1999; Hall 1978; Wills 2005). Eleven studies used hypertonic saline with 6% dextran 70 solution (HSD 6%) (Baker 2009; Bulger 2008; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Mattox 1991; Morrison 2011; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b; Younes 1992; Younes 1997). Three studies used hypertonic saline with dextran 70; Vassar 1993b used it at 12%, while Alpar 2004 used it at 4.2% and Oliveira 2002 used it at 8%. One study used hypertonic saline with dextran 60 (a relative molecular mass of 60,000 (HSD 6%)) (Chavez‐Negrete 1991). One study changed concentration of HSD during the study period; participants were initially given HSD 4.2% with dextran 70 before a protocol change to HSD 6% with dextran 70 (Vassar 1991).

Seven studies used a succinylated gelatin solution (of an isotonic composition) for fluid resuscitation (Annane 2013; Dung 1999; Evans 1996; Ngo 2001Upadhyay 2005; Van der Heijden 2009; Wu 2001).

Twenty‐two studies used albumin or FFP for fluid resuscitation. Thirteen studies used albumin (Annane 2013; Caironi 2014; Ernest 1999; Finfer 2004; Lucas 1978; Maitland 2005; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; McIntyre 2012; Park 2015; Philips 2015; Quinlan 2004; Rackow 1983). Three studies used albumin combined with an isotonic crystalloid, which was normal saline (Cooper 2006; Pockaj 1994; Van der Heijden 2009), and five studies used albumin combined with a hypertonic crystalloid, which was hypertonic saline (Jelenko 1979), or Ringer's lactate (Goodwin 1983; Lowe 1977; Metildi 1984; Shah 1977). One study used FFP with Ringer's lactate (O'Mara 2005).

Individual study protocols for the concentration, quantity, and timing of administration of each type of study colloid varied. We were not able to establish volume ratios of colloid solutions to crystalloid solutions in most studies; we found that study authors often reported that fluids were provided by the pharmacist and manufacturers in pre‐packaged bags, which we assumed contained fluids in clinically appropriate volume ratios.

Crystalloids

Thirty‐four studies used isotonic solutions as the comparative crystalloid fluid, which was normal saline (Annane 2013; Baker 2009; Bentsen 2006; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Dubin 2010; Dung 1999; Ernest 1999; Finfer 2004; Grba‐Bujevic 2012; Guidet 2012; James 2011; Jie 2015; Maitland 2005; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; Masoumi 2016; McIntyre 2008; McIntyre 2012; Morrison 2011; Myburgh 2012; Ngo 2001; Oliveira 2002; Philips 2015; Pockaj 1994; Quinlan 2004; Rackow 1983; Upadhyay 2005; Van der Heijden 2009; Vassar 1993a; Younes 1992; Younes 1997; Younes 1998; Zhao 2013).

Forty‐one studies used a hypertonic solution, which was Ringer's lactate (Alpar 2004; Annane 2013; Bechir 2013; Brunkhorst 2008; Bulger 2008; Chavez‐Negrete 1991; Cifra 2003; Cooper 2006; Du 2011; Dung 1999; Evans 1996; Goodwin 1983; Hall 1978; Jelenko 1979; Jie 2015; Kumar 2017; Lowe 1977; Lu 2012; Mahrous 2013; Metildi 1984; Nagy 1993; Ngo 2001; O'Mara 2005; Park 2015; Shah 1977; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993b; Vlachou 2010; Wills 2005; Wu 2001; Zhu 2011), Ringer's acetate (Modig 1986; Perner 2012), or hypertonic saline (Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Jelenko 1979; Li 2008; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b; Younes 1992).

One study used Ringer's acetate and normal saline (Heradstveit 2010), and three studies did not specify the type of crystalloid (Caironi 2014; Lucas 1978; Mattox 1991).

Individual study protocols for the quantity and timing of administration of each type of study crystalloid varied.

Outcomes

Only five studies did not report mortality data (Bentsen 2006; Dung 1999; Ernest 1999; Grba‐Bujevic 2012; Masoumi 2016); these five studies did not report any of our review outcomes. Fourteen studies reported number of participants who required transfusion of blood products (Annane 2013; Brunkhorst 2008; Bulger 2011; Cifra 2003; Cooper 2006; Guidet 2012; Lowe 1977; McIntyre 2008; Nagy 1993; Ngo 2001; Perner 2012; Pockaj 1994; Vlachou 2010; Wills 2005). Thirteen studies reported number of participants who required renal replacement therapy (Annane 2013; Bechir 2013; Brunkhorst 2008; Caironi 2014; Finfer 2004; Guidet 2012; James 2011; Mahrous 2013; McIntyre 2008; Myburgh 2012; Park 2015; Perner 2012; Vlachou 2010).

Nine studies reported data for adverse events (Bulger 2008; Guidet 2012; Mattox 1991; Myburgh 2012; Ngo 2001; Perner 2012; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1991; Wills 2005); seven reported incidences of allergic reaction (Bulger 2008; Mattox 1991; Myburgh 2012; Ngo 2001; Perner 2012; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1991), two reported incidences of itching (Guidet 2012; Myburgh 2012), and two reported incidences of rashes (Myburgh 2012; Wills 2005).

Funding sources

Thirty‐nine studies reported funding from departments or other sources that we judged to be independent (Annane 2013; Baker 2009; Brunkhorst 2008; Bulger 2008; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Caironi 2014; Du 2011; Dubin 2010; Dung 1999; Evans 1996; Finfer 2004; Goodwin 1983; Hall 1978; Heradstveit 2010; James 2011; Jelenko 1979; Lowe 1977; Lucas 1978; Maitland 2005; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; McIntyre 2012; Metildi 1984; Modig 1986; Morrison 2011; Myburgh 2012; Nagy 1993; Oliveira 2002; Perner 2012; Quinlan 2004; Rackow 1983; Shah 1977; Van der Heijden 2009; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Wills 2005; Zhao 2013). Nineteen studies reported funding from pharmaceutical companies, which may have supplied study fluids (Bechir 2013; Brunkhorst 2008; Cooper 2006; Dung 1999; James 2011; Guidet 2012; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; Mattox 1991; McIntyre 2008; Morrison 2011; Myburgh 2012; Ngo 2001; Perner 2012; Van der Heijden 2009; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b; Younes 1992). We noted that one study with pharmaceutical funding reported that funders were involved in the study design, analysis and preparation of the report (Guidet 2012).

The remaining studies did not report funding sources or declare conflicts of interest.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies.

We excluded 127 studies following consideration of the full‐text reports. Ninety‐three reports were of an ineligible study design (studies that were not RCTs, or were commentaries or editorial reports), nine studies had an ineligible participant group, and 25 studies used ineligible interventions (did not compare a colloid versus crystalloid, or fluids given at the wrong time). See Figure 1.

We have not included references and details of all 127 studies excluded during full‐text review, only the 31 that we considered to be key excluded studies (Higgins 2011).

Because of changes to the criteria for considering studies since the last version of the review (Perel 2013), we excluded 31 studies that were previously included and have listed these in the review. Reasons for excluding these studies were: in 28 studies fluid resuscitation was given as part of perioperative management of people undergoing elective surgery (Boutros 1979; Dawidson 1991; Dehne 2001; Eleftheriadis 1995; Evans 2003; Fries 2004; Gallagher 1985; Guo 2003; Hartmann 1993; Hondebrink 1997; Karanko 1987; Lee 2011; Ley 1990; Mazher 1998; McNulty 1993; Moretti 2003; Nielsen 1985; Prien 1990; Shires 1983; Sirieix 1999; Skillman 1975; Tollusfrud 1995; Tollusfrud 1998; Verheij 2006; Virgilio 1979; Wahba 1996; Zetterstorm 1981a; Zetterstorm 1981b); two studies were not RCTs (Bowser‐Wallace 1986; Grundmann 1982); and one study was an abstract of a study protocol where the full study was never published (Rocha e Silva 1994). In addition, we excluded five studies because the publications have been retracted; we have not listed references for these retracted publications.

See Criteria for considering studies for this review and Differences between protocol and review.

Studies awaiting classification

Seven studies are awaiting classification (Halim 2016; Bulanov 2004; Charpentier 2011; NCT00890383; NCT01337934; NCT02064075; Protsenko 2009).

We found three studies during the searches of clinical trials registers (NCT00890383; NCT01337934; NCT02064075). These studies were described as completed but study results were not available; we await publication of the full reports to assess their eligibility for inclusion in the review. One study compared tetrastarch versus an unspecified crystalloid for fluid resuscitation following trauma (NCT00890383); one study compared albumin versus Ringer's lactate for fluid resuscitation for sepsis and septic shock (NCT01337934); and one study compared hydroxyethyl starch versus Ringer's lactate for fluid resuscitation following subarachnoid haemorrhage (NCT02064075). Two studies were published only as abstracts with insufficient information; one compared gelatin versus normal saline for fluid resuscitation for sepsis and septic shock (Halim 2016), and one compared albumin versus normal saline for fluid resuscitation for septic shock (Charpentier 2011). Two studies were published in Russian and require translation to assess eligibility: one compared starches with normal saline (Bulanov 2004), and no details are known about the other study (Protsenko 2009). See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We found three ongoing studies during searches of clinical trial registers (NCT01763853; NCT02721238; NCT02782819). One study compares 4% albumin versus an unspecified crystalloid in people with acute respiratory distress syndrome (NCT01763853); one study compares 20% albumin versus plasmalyte in people with cirrhosis‐ and sepsis‐induced hypotension (NCT02721238); and the last study compares 5% albumin or gelatin versus Ringer's lactate or normal saline for treatment of shock (NCT02782819). See Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

We did not complete 'Risk of bias' assessments for studies that reported none of our review outcomes (Bentsen 2006; Dung 1999; Ernest 1999; Grba‐Bujevic 2012; Masoumi 2016).

We did not seek translation of studies that were published in Chinese (Jie 2015; Li 2008; Lu 2012; Zhu 2011). We made 'Risk of bias' assessments from details available in the English abstracts, and from the baseline characteristics tables.

Allocation

All studies were described as randomised. Thirty studies reported adequate methods of randomisation and we judged these to have a low risk of bias for random sequence generation (Annane 2013; Baker 2009; Bechir 2013; Bulger 2008; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Caironi 2014; Cooper 2006; Du 2011; Finfer 2004; Goodwin 1983; Guidet 2012; James 2011; Kumar 2017; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; Mattox 1991; McIntyre 2008; Morrison 2011; Myburgh 2012; Ngo 2001; O'Mara 2005; Oliveira 2002; Perner 2012; Upadhyay 2005; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b; Vlachou 2010; Wills 2005). Twenty‐four studies reported adequate methods of allocation concealment and we judged these to have a low risk of bias (Annane 2013; Baker 2009; Bechir 2013; Bulger 2008; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Caironi 2014; Cooper 2006; Finfer 2004; Guidet 2012; James 2011; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; Mattox 1991; McIntyre 2008; Morrison 2011; Ngo 2001; Perner 2012; Upadhyay 2005; Van der Heijden 2009; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b; Wills 2005).

Four studies were quasi‐randomised studies, and we believed that methods for random sequence generation and random allocation concealment were at high risk of selection bias (Alpar 2004; Cifra 2003; Lucas 1978; Modig 1986). Two studies were described as randomised but because of differences noted in the baseline characteristics table (Jelenko 1979), and unexplained differences in participant numbers (Lowe 1977), we judged them to be at high risk of bias for random sequence generation. One study described "use of lots" to allocate participants to groups and, without additional details, we were uncertain whether this method was adequate and so assessed risk of bias of random sequence generation as unclear (Hall 1978).

The remaining studies reported insufficient details of random sequence generation (Brunkhorst 2008; Chavez‐Negrete 1991; Dubin 2010; Evans 1996; Hall 1978; Heradstveit 2010; Jie 2015; Li 2008; Lu 2012; Mahrous 2013; Maitland 2005; McIntyre 2012; Metildi 1984; Nagy 1993; Park 2015; Philips 2015; Pockaj 1994; Quinlan 2004; Rackow 1983; Shah 1977; Van der Heijden 2009; Vassar 1990; Wu 2001; Younes 1992; Younes 1997; Younes 1998; Zhao 2013; Zhu 2011), and random allocation concealment (Brunkhorst 2008; Chavez‐Negrete 1991; Du 2011; Dubin 2010; Evans 1996; Goodwin 1983; Hall 1978; Heradstveit 2010; Jelenko 1979; Jie 2015; Kumar 2017; Li 2008; Lowe 1977; Lu 2012; Mahrous 2013; Maitland 2005; McIntyre 2012; Metildi 1984; Myburgh 2012; Nagy 1993; O'Mara 2005; Oliveira 2002; Park 2015; Philips 2015; Pockaj 1994; Quinlan 2004; Rackow 1983; Shah 1977; Vassar 1990; Vlachou 2010; Wu 2001; Younes 1992; Younes 1997; Younes 1998; Zhao 2013; Zhu 2011), and we judged these to have an unclear risk of selection bias.

Blinding

For the mortality outcome, we believed that lack of blinding was unlikely to influence performance, or influence outcome assessment, therefore, we judged all studies that reported mortality data as having a low risk of performance bias and a low risk of detection bias for mortality.

For the remaining outcomes (transfusion of blood products, renal replacement therapy, and adverse events), we assessed whether methods had been used to disguise fluid types from clinicians, and from outcome assessors. Nine studies reported sufficient methods of blinding and we judged these to have low risk of performance bias (Bechir 2013; Bulger 2011; Guidet 2012; Finfer 2004; James 2011; McIntyre 2008; Ngo 2001; Perner 2012; Wills 2005). Two studies described methods of fluid administration as open‐label, in which differences between study fluids would be apparent to personnel; we judged these to have a high risk of performance bias (Brunkhorst 2008; Cooper 2006). Study authors in Annane 2013 reported that clinicians were not blinded because of the immediate need for resuscitation; we judged this study to have a high risk of performance bias. We judged the remaining studies as having an unclear risk of performance bias because methods of blinding were not described (Caironi 2014; Cifra 2003; Lowe 1977; Mahrous 2013; Nagy 1993; Pockaj 1994; Vlachou 2010).

Six studies reported sufficient methods of blinding of outcome assessors and we judged these to have a low risk of detection bias (Bechir 2013; Bulger 2011; Guidet 2012; McIntyre 2008; Perner 2012; Wills 2005). We judged the remaining studies to have an unclear risk of detection bias because study authors reported insufficient methods of blinding of outcome assessors (Brunkhorst 2008; Caironi 2014; Cifra 2003; Cooper 2006; Finfer 2004; James 2011; Lowe 1977; Mahrous 2013; Nagy 1993; Ngo 2001; Pockaj 1994; Vlachou 2010).

Incomplete outcome data

Two studies, published only as abstracts, appeared to have some discrepancies in mortality data and we could not be certain whether this was because of loss of participant data; we judged these studies to have unclear risk of attrition bias (Mahrous 2013; Park 2015).

One study had an apparent loss of analysed participants for mortality, but not for transfusion of blood products, and we could not explain this difference in loss; we judged this study to have a high risk of attrition bias (Pockaj 1994). One study excluded three participants because of protocol deviations; because the study was small this represented a high loss and we judged the study to have an unclear risk of attrition bias (Vlachou 2010). One study noted that approximately 10% of participants did not meet eligibility criteria after randomisation, however these were included in an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis; we judged this study to have an unclear risk of attrition bias because this was a large number of participants in an ITT analysis (Bulger 2008).

The remaining studies had no losses, or few losses that were explained, and we judged them all to have low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

We found prospective clinical trials registration reports for nine studies (Annane 2013; Bechir 2013; Bulger 2008; Bulger 2010; Caironi 2014; Finfer 2004; Guidet 2012; Myburgh 2012; Perner 2012). Outcomes were reported according to these trial registration documents in six studies and we judged these to have a low risk of selective reporting bias (Annane 2013; Bulger 2010; Caironi 2014; Finfer 2004; Myburgh 2012; Perner 2012). In one study, we noted that outcomes were added to the trials register documents after the start of the study, and we could not be certain whether selective reporting bias was introduced because of this (Bulger 2008). In two studies, we noted that outcomes in the study report were not listed as outcomes in the clinical trials registration documents, and we judged these studies to have a high risk of selective reporting bias (Bechir 2013; Guidet 2012).

Three studies were registered retrospectively with clinical trials registers (Dubin 2010; James 2011; Maitland 2011); it was not feasible to use information from these clinical trials documents to assess risk of selective reporting bias.

We could not be certain whether Philips 2015 was prospectively registered because the available abstract report included the clinical trials register identification number but not the study dates; we judged this to have an unclear risk of selective reporting bias.

All other studies did not provide clinical trials registration information, or references for published study protocols, and we were unable to assess risk of selective reporting bias for these studies.

Baseline characteristics

We noted no differences in baseline characteristics that we believed could introduce bias in 46 studies, and we judged these studies to have a low risk of bias (Annane 2013; Baker 2009; Bechir 2013; Brunkhorst 2008; Bulger 2010; Bulger 2011; Chavez‐Negrete 1991; Cifra 2003; Du 2011; Dubin 2010; Evans 1996; Goodwin 1983; Guidet 2012; Hall 1978; Jie 2015; Li 2008; Lowe 1977; Lu 2012; Lucas 1978; Maitland 2011; Martin 2005; Metildi 1984; Modig 1986; Morrison 2011; Myburgh 2012; Nagy 1993; Ngo 2001; O'Mara 2005; Perner 2012; Philips 2015; Pockaj 1994; Rackow 1983; Shah 1977; Upadhyay 2005; Van der Heijden 2009; Vassar 1990; Vassar 1991; Vassar 1993a; Vassar 1993b; Vlachou 2010; Wills 2005; Wu 2001; Younes 1992; Younes 1997; Younes 1998; Zhu 2011).

We noted an imbalance in some baseline characteristics in eleven studies (Alpar 2004; Bulger 2008; Caironi 2014; Cooper 2006; Finfer 2004; James 2011; Kumar 2017; Maitland 2005; McIntyre 2008; Oliveira 2002; Quinlan 2004). We could not be certain whether these imbalances could influence results and we judged these studies to have an unclear risk of bias. We noted differences in several baseline characteristics in one study and judged this to have a high risk of bias (Jelenko 1979).

We could not assess comparability of baseline characteristics in four studies because these were either not reported or not reported by group (Mattox 1991; Mahrous 2013; McIntyre 2012; Park 2015).

Other potential sources of bias

We noted that in 14 studies some participants were given, or may have been given, additional colloids in the crystalloid arm either before or during the study (Annane 2013; Baker 2009; Brunkhorst 2008; Bulger 2011; Chavez‐Negrete 1991; Cifra 2003; Du 2011; Finfer 2004; Goodwin 1983; Myburgh 2012; Ngo 2001; Perner 2012; Vassar 1991; Wills 2005); we judged all these studies to have a high risk of other bias.

We noted that one study was published by a single author, and time between completion of the study and publication of the report was longer than expected (Kumar 2017). We could not be certain whether this study was a primary publication, or a secondary publication of an existing or unknown study, and we judged it to have a high risk of bias. We noted differences in the reported number of deaths in Lucas 1978 according to different study reports, and these differences were unexplained; we judged this study to have a high risk of other bias.

We could not be certain of other risks of bias in the Chinese studies for which we did not seek translation (Jie 2015; Li 2008; Lu 2012; Zhu 2011), nor in studies that were published only as abstracts (Mahrous 2013; Park 2015; Philips 2015); and we assessed these studies to have an unclear risk of other bias.

We noted no other sources of bias in the remaining studies, and judged these all to have a low risk of other bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Starches compared to crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients.

| Starches compared to crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients | ||||||

| Participants: critically ill people requiring fluid resuscitation Setting: in hospital, in Algeria, Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, the Netherlands, Phillipines, South Africa, Switzerland, Tunisia, the UK, USA and Vietnam Intervention: starches to include hydroxyethyl starch, hetastarch, and pentastarch Comparison: crystalloids to include normal saline, hypertonic saline, Ringer's lactate and Ringer's acetate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with crystalloids | Risk with starches | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (at end of follow‐up) | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.86 to 1.09) | 11,177 (24 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

We excluded data from 1 study because we could not be certain whether it accounted for attrition | |

| 233 per 1000 | 226 per 1000 (201 to 254) | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (at 90 days) | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) | 10,415 (15 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

We excluded data from 1 study because we could not be certain whether it accounted for attrition | |

| 238 per 1000 | 241 per 1000 (214 to 272) | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (within 30 days) | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.90 to 1.09) | 10,135 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

We excluded data from 1 study because we could not be certain whether it accounted for attrition | |

| 191 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (172 to 208) | |||||

| Transfusion of blood products | Study population | RR 1.19 (1.02 to 1.39) | 1917 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

1 study included different types of colloids (HES, gelatins, or albumin). We did not include this in analysis because study authors did not report data for only starches; we noted little or no difference between groups in need for transfusion of blood products in this study | |

| 299 per 1000 | 356 per 1000 (305 to 416) | |||||

| Renal replacement therapy | Study population | RR 1.30 (1.14 to 1.48) | 8527 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

1 study included different types of colloids (HES, gelatins, or albumin). We did not include this in analysis because study authors did not report data for only starches; we noted little or no difference between groups in need for renal replacement therapy in this study | |

| 82 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (93 to 121) | |||||

| Adverse events | Allergic reaction | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

||||

| Study population | RR 2.59 (0.27 to 24.91) | 7757 (3 studies) | ||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

|||||

| Itching | ||||||

| Study population | RR 1.38 (1.05 to 1.82) | 6946 (2 studies) | ||||

| 26 per 1000 | 35 per 1000 (27 to 46) |

|||||

| Rashes | ||||||

| Study population | RR 1.61 (0.90 to 2.89) | 7007 (2 studies) | ||||

| 5 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (5 to 15) |

|||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aWe downgraded by one level for study limitations; some included studies had unclear risk of selection bias, one small study had a high risk of selection bias, and we were often unable to assess risk of selective reporting bias because many included studies did not have prospective clinical trials registration. bWe downgraded by one level for study limitations; some included studies had unclear risk of selection bias, and we were often unable to assess risk of selective reporting bias because many included studies did not have prospective clinical trials registration. cWe downgraded by one level for study limitations; some included studies had unclear risk of selection bias, and we were unable to assess risk of selective reporting bias in some studies because they did not have prospective clinical trials registration. We downgraded by two levels for imprecision; few of our included studies reported data for these outcomes.

Summary of findings 2. Dextrans compared to crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients.

| Dextrans compared to crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients | ||||||

| Participants: critically ill people requiring fluid resuscitation Setting: in hospital, or out of hospital, in Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Mexico, Sweden, UK, USA and Vietnam Intervention: dextrans Comparison: crystalloids to include: normal saline, hypertonic saline, Ringer's lactate, Ringer's acetate, and unspecified types of crystalloids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with crystalloids | Risk with dextrans | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (at end of follow‐up) | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.88 to 1.11) | 4736 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

||

| 237 per 1000 | 235 per 1000 (209 to 263) | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (within 90 days and within 30 days) | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.87 to 1.12) | 3353 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

||

| 258 per 1000 | 256 per 1000 (225 to 289) | |||||

| Transfusion of blood products | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.77 to 1.10) |

1272 (3 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb |

||

| 332 per 1000 | 305 per 1000 (255 to 365) |

|||||

| Renal replacement therapy | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| Adverse events | Allergic reactions | |||||

| Study population | RR 6.00 (0.25 to 144.93) |

739 (4 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

|||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

|||||

| Itching | ||||||

| Study population | Not measured | ‐ | ||||

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Rashes | ||||||

| Study population | Not measured | ‐ | ||||

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aWe downgraded by one level for study limitations; some included studies had unclear risk of selection bias and we were often unable to assess risk of selective reporting bias because many included studies did not have prospective clinical trials registration. bWe downgraded by two levels for study limitations; we noted in two studies that some participants were given additional colloids in the crystalloid group, and in one study we could not be certain whether some participants in the crystalloids groups also received up to 2000 mL colloid resuscitation prior to randomisation. In addition, we were unable to assess risk of selective reporting bias because of lack of prospective clinical trials registration in each study. We downgraded by one level for imprecision; evidence was from three studies. cWe downgraded by one level for study limitations; one study had an unclear risk of selection bias and we were unable to assess risk of selective outcome reporting bias in all studies. We downgraded by two levels for imprecision because evidence was from few studies with few events.

Summary of findings 3. Gelatins compared to crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients.

| Gelatins compared to crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients | ||||||

| Participants: critically ill people requiring fluid resuscitation Setting: in hospital, in Algeria, France, Germany, India, South Africa, Taiwan, Tunisia and Vietnam Intervention: gelatins Comparison: crystalloids to include normal saline and Ringer's lactate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with crystalloids | Risk with gelatins | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (at end of follow‐up) | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.74 to 1.08) | 1698 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa |

||

| 301 per 1000 | 268 per 1000 (223 to 325) | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (within 90 days) | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.73 to 1.09) | 1388 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb |

||

| 334 per 1000 | 298 per 1000 (244 to 364) |

|||||

| All‐cause mortality (within 30 days) | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.74 to 1.16) | 1388 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb |

||

| 266 per 1000 | 244 per 1000 (197 to 308) |

|||||

| Transfusion of blood products | Study population | RR 5.89 (0.24 to 142.41) |

167 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

We calculated an effect estimate for one small study, with one event in the gelatin group. 1 study reported transfusion of blood products but data were not reported by group. 1 study included different types of colloids (HES, gelatins, or albumin). We did not include this in analysis because study authors did not report data for only gelatins. We noted little or no difference between groups in need for transfusion of blood products |

|

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

|||||

| Renal replacement therapy | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 study included different types of colloids (HES, gelatins, or albumin). We did not include this in analysis because study authors did not report data for only gelatins. We noted little or no difference between groups in need for renal replacement therapy |

| Adverse events | Allergic reaction | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

We calculated an effect estimate for one small study, with five incidences of allergic reactions in the gelatin group | |||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

RR 21.61 (1.22 to 384.05) | 167 (1 study) |

|||

| Itching | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

| Rashes | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aWe downgraded by one level for study limitations; risk of selection bias was unclear in some studies, and because we were unable to assess risk of selective outcome reporting bias in some studies. We downgraded by one level for imprecision; evidence was from few studies, and we could not be certain of time points for data collection. bWe downgraded by two levels for imprecision; evidence was from a single study. cWe downgraded by one level for study limitations; we were unable to assess risk of selective outcome reporting bias due to lack of prospective clinical trials registration, and some participants in the crystalloid groups also received colloids. We downgraded two levels for imprecision; evidence was from a single small study with very few events.

Summary of findings 4. Albumin and fresh frozen plasma compared to crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients.

| Albumin and fresh frozen plasma compared to crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients | ||||||

| Participants: critically ill people requiring fluid resuscitation Setting: in hospital and out of hospital, in Algeria, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Kenya, India, Italy, Tanzania, Tunisia, Uganda and USA Intervention: albumin and fresh frozen plasma Comparison: crystalloids to include: normal saline, hypertonic saline, Ringer's lactate, electrolytes, and unspecified types of crystalloids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with crystalloids | Risk with albumin and FFP | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (at end of follow‐up) | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.92 to 1.06) | 13,047 (20 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

One study also reported mortality but not by group, and so could not be included in analysis | |

| 254 per 1000 | 249 per 1000 (234 to 270) | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (within 90 days) | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.92 to 1.04) | 12,492 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

One study also reported mortality but not by group, and so could not be included in analysis | |

| 259 per 1000 | 254 per 1000 (239 to 270) | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (within 30 days) | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 12,506 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

One study also reported mortality but not by group, and so could not be included in analysis | |

| 234 per 1000 | 231 per 1000 (217 to 248) | |||||

| Transfusion of blood products | Study population | RR 1.31 (0.95 to 1.80) | 290 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb |

1 study included different types of colloids (HES, gelatins, or albumin). We did not include this in analysis because study authors did not report data for only albumins or FFP; we noted little or no difference between groups in need for transfusion of blood products | |

| 281 per 1000 | 368 per 1000 (267 to 506) | |||||

| Renal replacement therapy | 201 per 1000 | 223 per 1000 (193 to 255) |

RR 1.11 (0.96 to 1.27) | 3028 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc |

One study stated that renal replacement data were measured but it was not reported in the study report (abstract) 1 study included different types of colloids (HES, gelatins, or albumin). We did not include this in analysis because study authors did not report data for only albumin and FFP. We noted little or no difference between groups in need for renal replacement therapy |

| Adverse events | Allergic reactions | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd |

||||

| Study population | RR 0.75 (0.17 to 3.33) | 2097 (1 study) |

||||

| 4 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (1 to 13) |

|||||

| Itching | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Rashes | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; FFP: fresh frozen plasma RR: Risk ratio | ||||||