Abstract

Background

A large number of people are employed in sedentary occupations. Physical inactivity and excessive sitting at workplaces have been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, obesity, and all‐cause mortality.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of workplace interventions to reduce sitting at work compared to no intervention or alternative interventions.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, OSH UPDATE, PsycINFO, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal up to 9 August 2017. We also screened reference lists of articles and contacted authors to find more studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cross‐over RCTs, cluster‐randomised controlled trials (cluster‐RCTs), and quasi‐RCTs of interventions to reduce sitting at work. For changes of workplace arrangements, we also included controlled before‐and‐after studies. The primary outcome was time spent sitting at work per day, either self‐reported or measured using devices such as an accelerometer‐inclinometer and duration and number of sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more. We considered energy expenditure, total time spent sitting (including sitting at and outside work), time spent standing at work, work productivity and adverse events as secondary outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened titles, abstracts and full‐text articles for study eligibility. Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias. We contacted authors for additional data where required.

Main results

We found 34 studies — including two cross‐over RCTs, 17 RCTs, seven cluster‐RCTs, and eight controlled before‐and‐after studies — with a total of 3,397 participants, all from high‐income countries. The studies evaluated physical workplace changes (16 studies), workplace policy changes (four studies), information and counselling (11 studies), and multi‐component interventions (four studies). One study included both physical workplace changes and information and counselling components. We did not find any studies that specifically investigated the effects of standing meetings or walking meetings on sitting time.

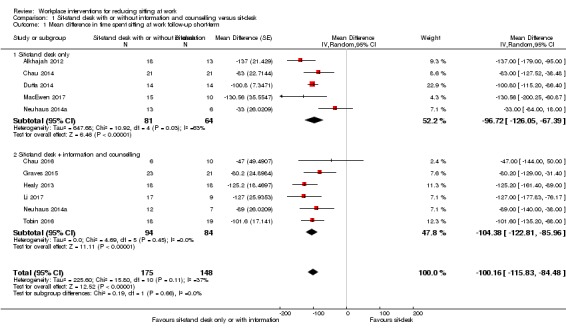

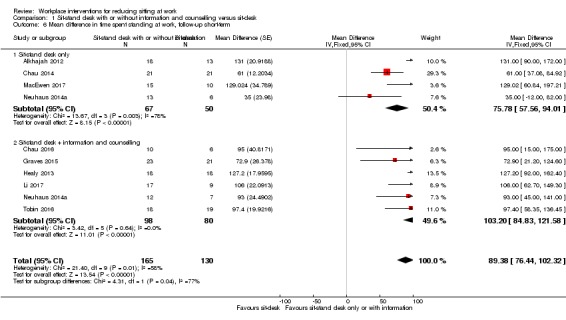

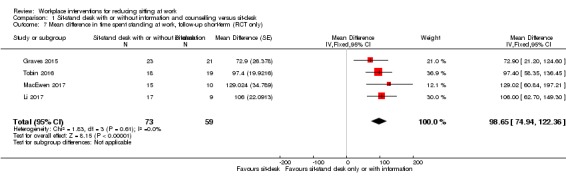

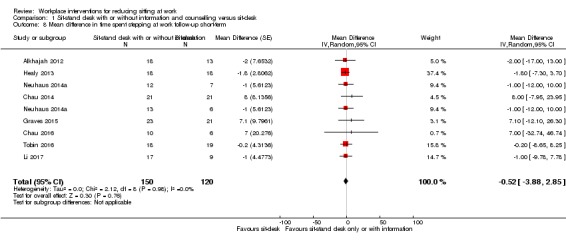

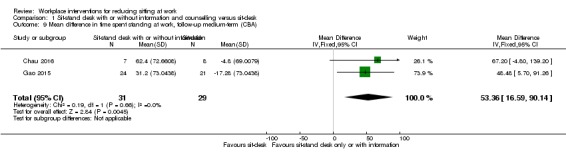

Physical workplace changes

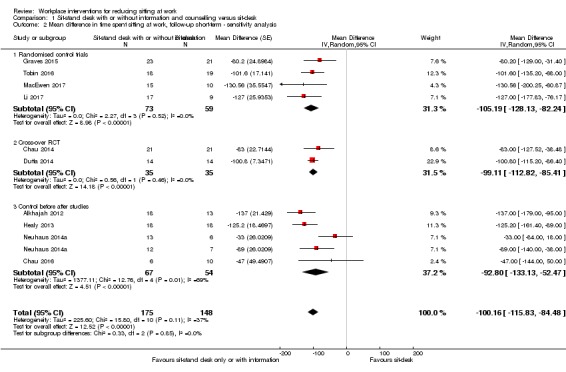

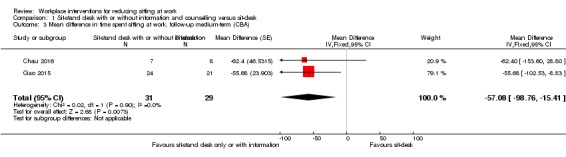

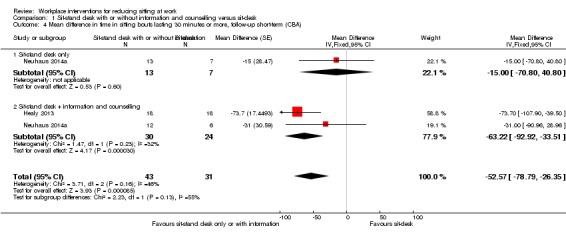

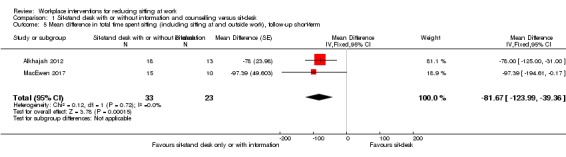

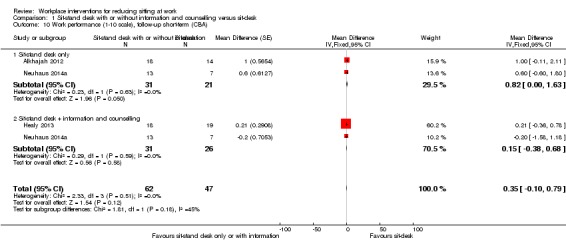

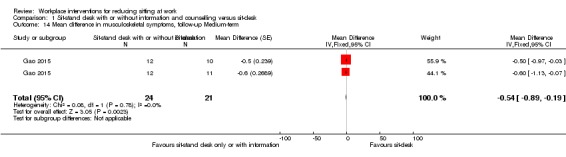

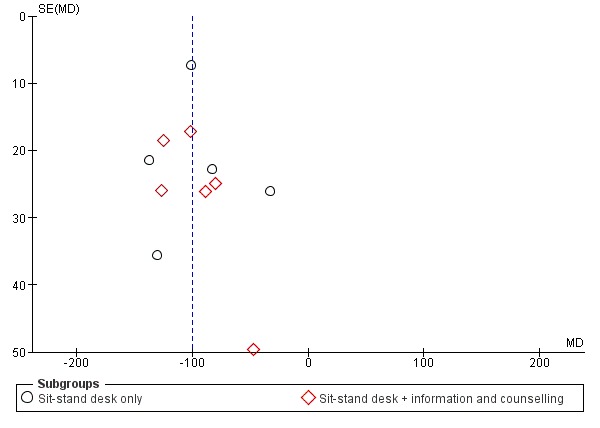

Interventions using sit‐stand desks, either alone or in combination with information and counselling, reduced sitting time at work on average by 100 minutes per workday at short‐term follow‐up (up to three months) compared to sit‐desks (95% confidence interval (CI) −116 to −84, 10 studies, low‐quality evidence). The pooled effect of two studies showed sit‐stand desks reduced sitting time at medium‐term follow‐up (3 to 12 months) by an average of 57 minutes per day (95% CI −99 to −15) compared to sit‐desks. Total sitting time (including sitting at and outside work) also decreased with sit‐stand desks compared to sit‐desks (mean difference (MD) −82 minutes/day, 95% CI −124 to −39, two studies) as did the duration of sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more (MD −53 minutes/day, 95% CI −79 to −26, two studies, very low‐quality evidence).

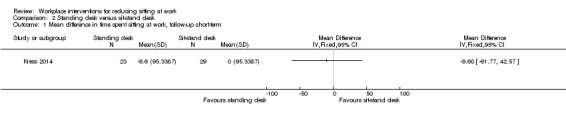

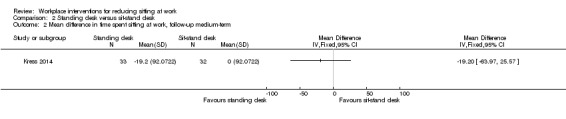

We found no significant difference between the effects of standing desks and sit‐stand desks on reducing sitting at work. Active workstations, such as treadmill desks or cycling desks, had unclear or inconsistent effects on sitting time.

Workplace policy changes

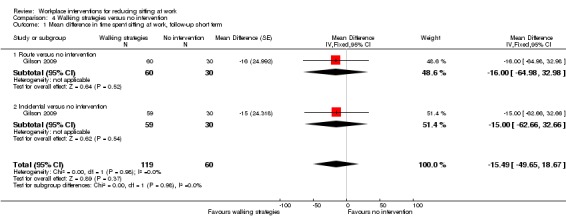

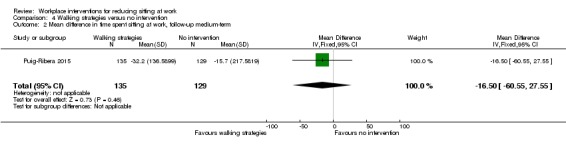

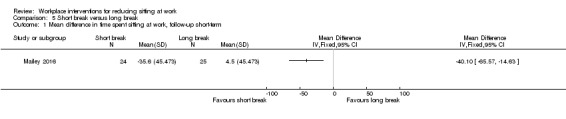

We found no significant effects for implementing walking strategies on workplace sitting time at short‐term (MD −15 minutes per day, 95% CI −50 to 19, low‐quality evidence, one study) and medium‐term (MD −17 minutes/day, 95% CI −61 to 28, one study) follow‐up. Short breaks (one to two minutes every half hour) reduced time spent sitting at work on average by 40 minutes per day (95% CI −66 to −15, one study, low‐quality evidence) compared to long breaks (two 15‐minute breaks per workday) at short‐term follow‐up.

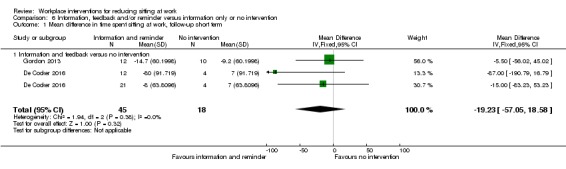

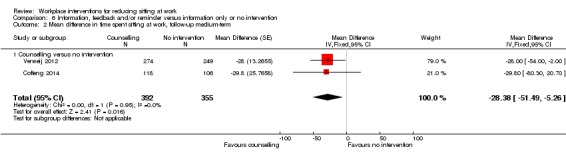

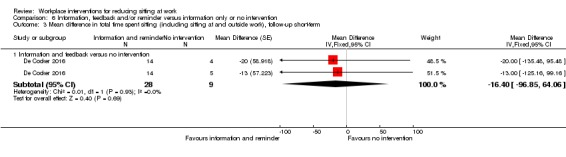

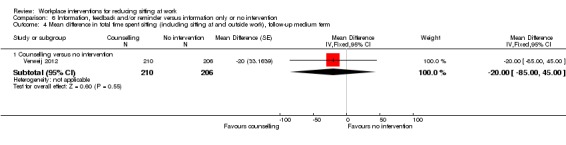

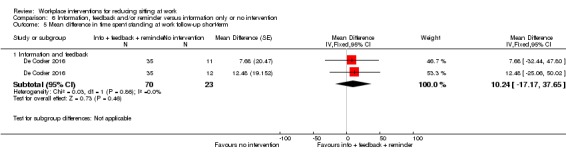

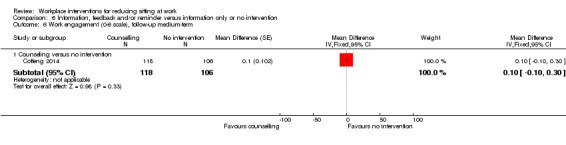

Information and counselling

Providing information, feedback, counselling, or all of these resulted in no significant change in time spent sitting at work at short‐term follow‐up (MD −19 minutes per day, 95% CI −57 to 19, two studies, low‐quality evidence). However, the reduction was significant at medium‐term follow‐up (MD −28 minutes per day, 95% CI −51 to −5, two studies, low‐quality evidence).

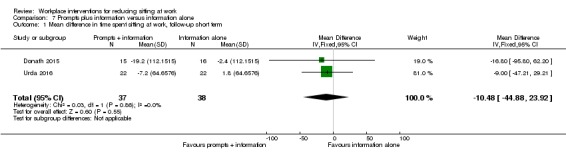

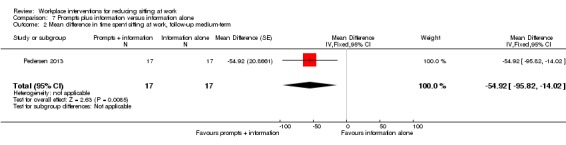

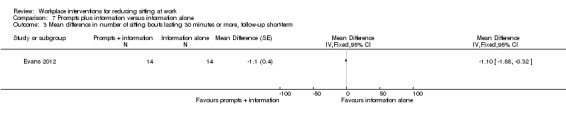

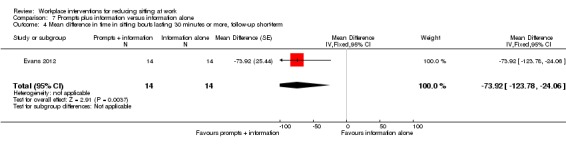

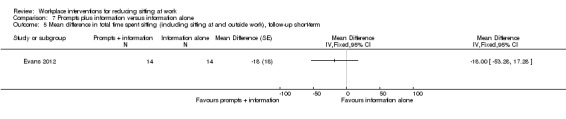

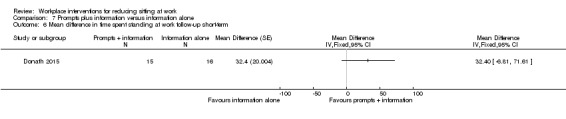

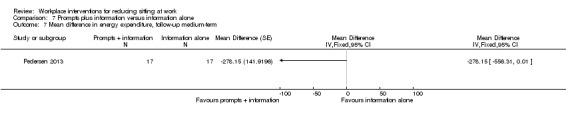

Computer prompts combined with information resulted in no significant change in sitting time at work at short‐term follow‐up (MD −10 minutes per day, 95% CI −45 to 24, two studies, low‐quality evidence), but at medium‐term follow‐up they produced a significant reduction (MD −55 minutes per day, 95% CI −96 to −14, one study). Furthermore, computer prompting resulted in a significant decrease in the average number (MD −1.1, 95% CI −1.9 to −0.3, one study) and duration (MD ‐74 minutes per day, 95% CI −124 to −24, one study) of sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more.

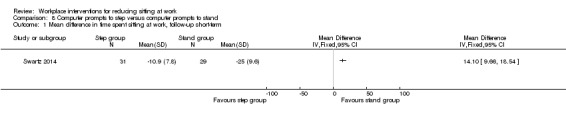

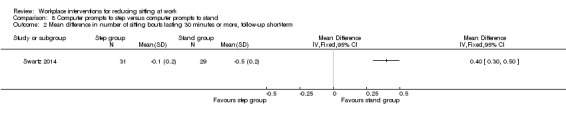

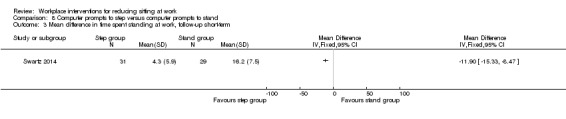

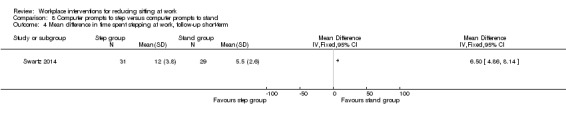

Computer prompts with instruction to stand reduced sitting at work on average by 14 minutes per day (95% CI 10 to 19, one study) more than computer prompts with instruction to walk at least 100 steps at short‐term follow‐up.

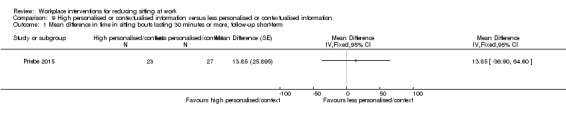

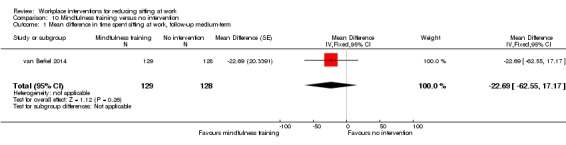

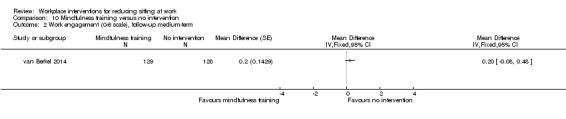

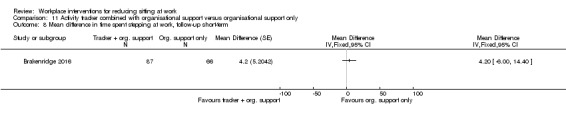

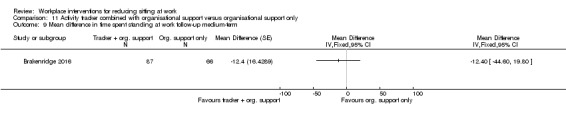

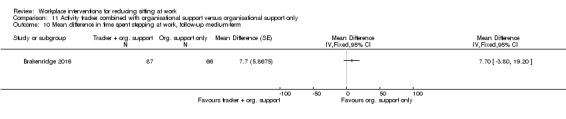

We found no significant reduction in workplace sitting time at medium‐term follow‐up following mindfulness training (MD −23 minutes per day, 95% CI −63 to 17, one study, low‐quality evidence). Similarly a single study reported no change in sitting time at work following provision of highly personalised or contextualised information and less personalised or contextualised information. One study found no significant effects of activity trackers on sitting time at work.

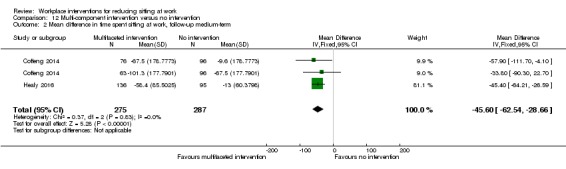

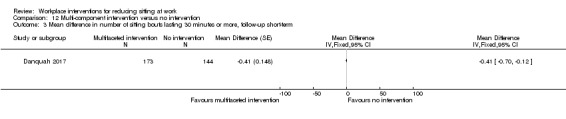

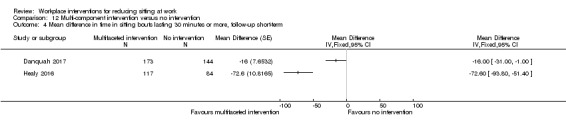

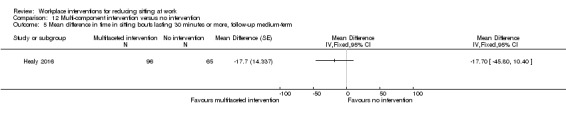

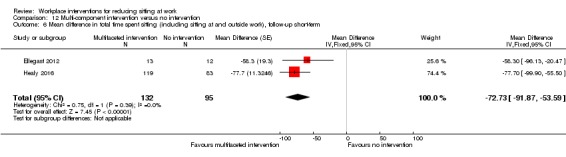

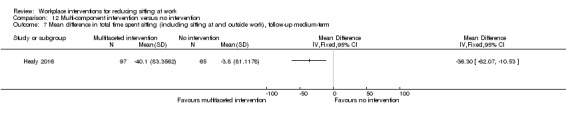

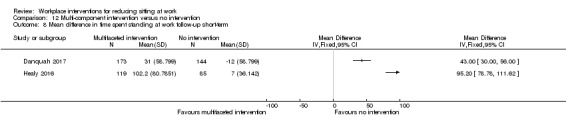

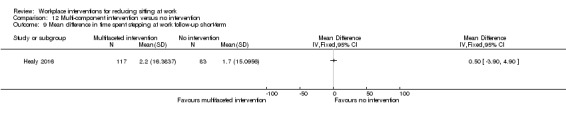

Multi‐component interventions

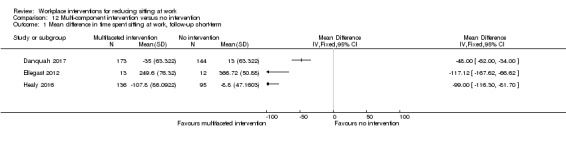

Combining multiple interventions had significant but heterogeneous effects on sitting time at work (573 participants, three studies, very low‐quality evidence) and on time spent in prolonged sitting bouts (two studies, very low‐quality evidence) at short‐term follow‐up.

Authors' conclusions

At present there is low‐quality evidence that the use of sit‐stand desks reduce workplace sitting at short‐term and medium‐term follow‐ups. However, there is no evidence on their effects on sitting over longer follow‐up periods. Effects of other types of interventions, including workplace policy changes, provision of information and counselling, and multi‐component interventions, are mostly inconsistent. The quality of evidence is low to very low for most interventions, mainly because of limitations in study protocols and small sample sizes. There is a need for larger cluster‐RCTs with longer‐term follow‐ups to determine the effectiveness of different types of interventions to reduce sitting time at work.

Keywords: Humans, Ergonomics, Posture, Accelerometry, Controlled Before‐After Studies, Energy Metabolism, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Time Factors, Workplace, Workplace/statistics & numerical data

Workplace interventions (methods) for reducing time spent sitting at work

Why is the amount of time spent sitting at work important?

Time spent sitting and being physically inactive at work has increased in recent decades. Long periods of sitting may increase the risk of obesity, heart disease, and premature death. It is unclear whether interventions that aim to reduce sitting at workplaces are effective.

The purpose of this review

We wanted to find out the effects of interventions aimed at reducing sitting time at work. We searched the literature in various databases up to 9 August 2017.

What trials did the review find?

We found 34 studies conducted with a total of 3,397 employees from high‐income countries. Sixteen studies evaluated physical changes in the workplace design and environment, four studies evaluated changes in workplace policies, 10 studies evaluated information and counselling interventions, and four studies evaluated multi‐category interventions.

Effect of sit‐stand desks

The use of sit‐stand desks seems to reduce workplace sitting on average by 84 to 116 minutes per day. When combined with the provision of information and counselling, the use of sit‐stand desks seems to result in similar reductions in sitting at work. Sit‐stand desks also seem to reduce total sitting time (including sitting at work and outside work) and the duration of workplace sitting bouts that last 30 minutes or longer. One study compared standing desks and sit‐stand desks but due to the small number of employees included, it does not provide enough evidence to determine which type of desk is more effective at reducing sitting time.

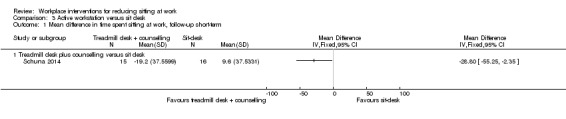

Effect of active workstations

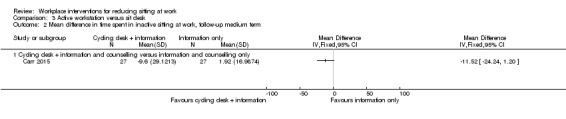

Treadmill desks combined with counselling seem to reduce sitting time at work, while the available evidence is insufficient to conclude whether cycling desks combined with the provision of information reduce sitting at work more than the provision of information alone.

Effect of walking during breaks or length of breaks

The available evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of walking during breaks in reducing sitting time. Taking short breaks (one to two minutes every half hour) seems to reduce time spent sitting at work by 15 to 66 minutes per day more than taking long breaks (two 15‐minute breaks per workday).

Effect of information and counselling

Providing information, feedback, counselling, or all of these reduces sitting time at medium‐term follow‐up (3 to 12 months after the intervention) on average by 5 to 51 minutes per day. The available evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions about the effects at short‐term follow‐up (up to three months after the intervention). The use of computer prompts combined with providing information reduces sitting time in the medium‐term on average by 14 to 96 minutes per day. The available evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions about the effects in the short‐term.

One study found that prompts to stand reduce sitting time more than prompts to step, on average by 10 to 19 minutes per day.

The available evidence is insufficient to conclude whether providing highly personalised or contextualised information is more or less effective than providing less personalised or contextualised information in reducing siting time at work. The available evidence is also insufficient to draw conclusions about the effect of mindfulness training and the use of activity trackers on sitting at work.

Effect of combining multiple interventions

Combining multiple interventions seems to be effective in reducing sitting time and time spent in prolonged sitting bouts in the short‐term and the medium‐term. However, this evidence comes from only a small number of studies and the effects were very different across the studies.

Conclusions

The quality of evidence is low to very low for most interventions, mainly because of limitations in study protocols and small sample sizes. At present there is low‐quality evidence that sit‐stand desks may reduce sitting at work in the first year of their use. However, the effects are likely to reduce with time. There is generally insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about such effects for other types of interventions and for the effectiveness of reducing workplace sitting over periods longer than one year. More research is needed to assess the effectiveness of different types of interventions for reducing sitting at workplaces, particularly over longer periods.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Alternative desks and workstations compared to sit‐desks for reducing sitting at work

| Alternative desks and workstations compared to sit‐desks for reducing sitting at work | |||||

| Patient or population: employees who sit at work Setting: workplace Intervention: alternative desks and workstations Comparison: sit‐desks | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with sit‐desk | Risk with changes in desk | ||||

| Comparison: sit‐stand desk with or without information and counselling versus sit‐desk | |||||

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, short‐term follow‐up (up to 3 months) | The mean difference in time spent sitting at work (short‐term follow‐up) was 364 minutes | MD 100 minutes lower (116 lower to 84 lower) | 323 (10 studies: 4 RCTs, 2 cross‐over RCTs, 4 CBAs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Subgroup analysis showed no difference in effect between sit‐stand desks used alone or in combination with information and counselling. Restricting the analysis to RCTs only did not show any difference in effect either. |

| Mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more, short‐term follow‐up | The mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more (short‐term follow‐up) was 167 minutes | MD 53 minutes lower (79 lower to 26 lower) | 74 (2 CBAs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 3 | |

| Comparison: treadmill desk combined with counselling versus sit‐desk | |||||

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, short‐term follow‐up (up to 3 months) | The mean difference in time spent sitting at work (short‐term follow‐up) was 342 minutes | MD 29 minutes lower (55 lower to 2 lower) | 31 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 4 | |

| Mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more, short‐term follow‐up — not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Comparison: cycling desk + information and counselling versus sit‐desk + information and counselling | |||||

| Mean difference in time spent in inactive sitting at work, medium‐term follow‐up (from 3 to 12 months) | The mean difference in time spent in inactive sitting at work (medium‐term follow‐up) was 413 minutes | MD 12 minutes lower (24 lower to 1 higher) | 54 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 5 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial CBA: controlled before‐and‐after study; MD: mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Of the six RCTs, five were at high risk of bias. The non‐randomised controlled before‐and‐after study/studies were also at high risk of bias; downgraded one level

2 Imprecision with wide confidence intervals, small sample size; downgraded one level

3 Unconcealed allocation, unblinded outcome assessment and attrition bias; downgraded two levels

4 Unblinded outcome assessment; downgraded one level

5 Unblinded outcome assessment and attrition bias; downgraded one level

Summary of findings 2.

Workplace policy changes compared to no intervention or alternate intervention for reducing sitting at work

| Workplace policy changes compared to no intervention for reducing sitting at work | |||||

| Patient or population: employees who sit at work Setting: workplace Intervention: policy changes Comparison: no intervention | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no intervention | Risk with Policy changes | ||||

| Comparision: walking strategies versus no intervention | |||||

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, short‐term follow‐up | The mean difference in time spent sitting at work (short‐term follow‐up) was 344 minutes | MD 15 minutes lower (50 lower to 19 higher) | 179 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more, short‐term follow‐up — not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Comparision: short break versus long break | |||||

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, short‐term follow‐up | The mean difference in time spent sitting at work (short term follow‐up) was 131 minutes | MD 40 minutes lower (66 lower to 15 lower) | 49 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | |

| Mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more, short‐term follow‐up — not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; MD: mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Risk of bias high due to unblinded outcome assessment and lack of allocation concealment; downgraded with one level

2 Imprecision with wide confidence intervals; downgraded with one level

3 Unconcealed allocation and attrition bias

Summary of findings 3.

Information, feedback, and/or counselling compared to information only or no intervention for reducing sitting at work

| Information and counselling compared to information only or no intervention for reducing sitting at work | |||||

| Patient or population: employees who sit at work Setting: workplace Intervention: information and counselling Comparison: information only or no intervention | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with information only or no intervention | Risk with Information and counselling | ||||

| Information, feedback and counselling versus no intervention | |||||

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, short‐term follow‐up — information and feedback versus no intervention | The mean difference in time spent sitting at work (short‐term follow‐up) was 550 minutes | MD 19 minutes lower (57 lower to 19 higher) | 63 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, medium‐term follow‐up — counselling versus no intervention | The mean difference in time spent sitting at work (medium‐term follow‐up) was 462 minutes | MD 28 minutes lower (51 lower to 5 lower) | 747 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more, short‐term follow‐up ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Prompts combined with information versus information alone | |||||

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, short‐term follow‐up | The mean difference in time spent sitting at work (short‐term follow‐up) was 349 minutes | MD 10 minutes lower (45 lower to 24 higher) | 75 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more, short‐term follow‐up | The mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more (short‐term follow‐up) was 286 minutes | MD 74 minutes lower (124 lower to 24 lower) | 28 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | |

| Mindfulness training versus no intervention | |||||

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, medium‐term follow‐up | The mean difference in time spent sitting at work (medium‐term follow‐up) was 316 minutes | MD 23 minutes lower (63 lower to 17 higher) | 257 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 6 | |

| Mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more, medium‐term follow‐up — not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; MD: mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Imprecision with wide confidence intervals, small sample size; downgraded with one level

2 Unblinded outcome assessment and attrition bas

3 Risk of bias, allocation not concealed, lack of blinding, high attrition rate; downgraded with one level

4 Lack of blinding of participants and selective reporting

5 Lack of blinding of participants and attrition bias

6 Risk of bias high due to unconcealed allocation and unblinded outcome assessment; downgraded with one level

7 Lack of blinding of participants

Summary of findings 4.

Multi‐component intervention compared to no intervention for reducing sitting at work

| Multi‐component intervention compared to no intervention for reducing sitting at work | |||||

| Patient or population: employees who sit at work Setting: workplace Intervention: multi‐component intervention Comparison: no intervention | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no intervention | Risk with Multi‐component intervention | ||||

| Mean difference in time spent sitting at work, short‐term follow‐up | See comment | see comment | 573 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | Not pooled |

| Mean difference in time in sitting bouts lasting 30 minutes or more, short‐term follow‐up | See comment | See comment | 518 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | Not pooled |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Unconcealed allocation and unblinded outcome assessment

2 Imprecision with wide confidence interval, small sample size

3 Not pooled due to high heterogeneity

3 Small sample size

Background

Description of the condition

Sedentary behaviour, especially sitting, has attracted great interest from media, government agencies and researchers in recent years. Energy expenditure in various tasks can be expressed in metabolic equivalents (METs). One MET is equivalent to resting energy expenditure, i.e. the energy cost of resting quietly, defined as an oxygen uptake of 3.5 mL kg‐1 min‐1(Ainsworth 2000). Sitting at work and conducting work tasks whilst seated usually involves energy expenditure of 1.5 METs or less. Reduction in time spent sitting usually results in increased levels of physical activity of light to moderate intensity, such as standing or walking (Mansoubi 2014).

The nature of office work has changed since the year 2000 in such a way that workers do not have to move often from their work stations (VicHealth 2012). Advancement in technology (e.g. robotics, computers) has led to a decrease in physical strain at workplaces (Craig 2002). Consequently, workers in some settings have become less physically active at their workplace compared to their leisure time (Franklin 2011; McCrady 2009; Parry 2013; Thorp 2012; van Uffelen 2010). Since the 1960s, in the USA and the UK for example, population levels of occupational physical activity have declined by more than 30% (Ng 2012). A large decline in occupational physical activity has been also found in low‐ and middle‐income countries, such as Brazil and China (Ng 2012). This decline in occupational physical activity can largely be attributed to an increase in time spent sitting at the workplace. It has been found that office‐based employees spent 66% of their total working time sitting, with 5% of all sitting events and 25% of total sitting time spent in bouts longer than 55 minutes (Ryan 2011).

Studies have shown that excessive time spent sitting at work may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, and all‐cause mortality, even if one is engaged in recommended levels of physical activity during their leisure time (Chau 2014a; Craft 2012; Dunstan 2011). Estimates show a 5% increase in the risk of obesity and 7% increase in the risk of diabetes associated with every two‐hour per day increase in sitting time at work (Hu 2003). It has also been estimated that those who sit for eight to 11 hours per day are at a 15% increased risk of death in the next three years than those who sit for less than four hours per day, whilst the risk increases to 40% for those who sit for more than 11 hours per day (Van der Ploeg 2012). In Bey 2003, it is hypothesised that replacing sitting with physical activity of light (from 1.5 METs to 3 METs) to moderate (3 METs to 6 METs; Ainsworth 2011) intensity improves glucose and lipid metabolism. Another study, Duvivier 2013, has also suggested that benefits may be greater when sitting is replaced with activity of light to moderate intensity, such as standing and walking, than when it is replaced with vigorous cycling of equal energy expenditure. This may indicate that, in interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour, changing posture may be equally or even more important than increasing energy expenditure.

Description of the intervention

It is estimated that 60% of the world's population is part of the workforce and spends on average 60% of their waking hours at work (WHO/WEF 2008). Thus, it is possible to influence health behaviour of a large proportion of the adult population worldwide through workplace interventions.

Workplaces have the advantage of having the potential for creating in‐built social support, that is, active collaboration of employees in making sustainable changes to attain a healthy lifestyle, which may reduce the degree of individual effort and motivation needed to make behavioural changes. Therefore, the changes in lifestyle achieved at work are thought to be sustainable in the long term (Plotnikoff 2012).

Workers can be encouraged to be more physically active through changes in the workplace environment and design. A conventional sitting desk can be replaced or supplemented with: a sit‐stand desk; a so‐called 'hot desk' that is height‐adjustable and allows its user to alternate posture between sitting and standing (Alkhajah 2012; Gilson ND 2012; Straker 2013); a vertical workstation that allows the use of a personal computer while walking on a treadmill at a self‐selected velocity (Levine 2007); a stepping/pedalling desk exercise machine placed under the desk that allows the user to step or pedal while being seated (McAlpine 2007); an inflated balloon chair; or a therapy ball (Beers 2008; USPTO 2000). Replacing conventional office chairs with inflated balloon chairs makes the act of sitting more physically demanding by increasing the need to use the abdominal, back, leg and thigh muscles to remain upright and maintain balance.

Time spent in sedentary behaviour can theoretically also be reduced by changing the layout of workplaces, for example by placing printers further away from desks. Office work can also be made more physically demanding by forming walking or other exercise groups like dance or gym groups during work time (Ogilvie 2007; Thogersen‐Ntoumani 2013), and by encouraging employees to walk around office buildings during breaks or to take a walk to communicate with fellow employees instead of using the telephone or email. The practices and policies of workplaces can be changed by incorporating periodic breaks within the organisational schedule including short bouts of physical activity (e.g. five to 15‐minute activity bouts) or by conducting walking or standing meetings (Commissaris 2007). Meeting rooms can be equipped with sit‐stand desks so that employees can choose to stand during meetings, if they wish (Atkinson 2014). These changes in workplace practice and policy have the potential of providing an opportunity to a large number of people, who mostly sit at work, to reduce their sitting time.

Workers can also be made aware of the importance of changing their sitting behaviour by the provision of information, such as by motivational prompts to sit less at the workstation, via e‐health interventions that encourage and remind workers to sit less or interrupt prolonged periods of sitting (Cooley 2014; Evans 2012; Pedersen 2013), or by distributing leaflets with messages like "Sit less, move more" that highlight the risks associated with sitting. An e‐health intervention consists of information that is delivered electronically like emails, point‐of‐choice prompts, or any message periodically displayed on the computer screen. Informational interventions can also be delivered by trained counsellors in an interactive manner, where, as part of counselling sessions, they find out about worker's interests and provide the worker different options on how to reduce sedentary behaviour (Opdenacker 2008).

There are some potential drawbacks to these interventions. The performance and productivity of workers at sitting jobs might be decreased when walking at the workplace is encouraged and the employees more frequently leave their desks. Workers using a treadmill desk need to be careful not to trip or fall, and thus divide their attention between work and safety, which might compromise their productivity (Tudor‐Locke 2013). In addition, fine motor skills like mouse handling accuracy, math problem solving skills, and perceived work performance seem to decrease with treadmill and cycling desks (Commissaris 2014; John 2009). This decrease in efficiency might be due to learning effects, that is, becoming acquainted with new modes of work.

How the intervention might work

According to ecological models, successful strategies for reducing sedentary behaviour include:

providing access to infrastructures for reducing sedentary behaviour;

increasing awareness and understanding of the importance of and methods for reducing sedentary behaviour; or

using social networks and organisational support to inform and encourage changes in policies and norms related to sedentary behaviour (Sallis 2006).

Based on this definition, we envisage three different ways (in isolation or conjunction with each other) in which interventions could work to decrease sitting at workplaces.

Physical changes in the workplace design and environment

If employees are using a conventional desk or chair in the workplace, provision of new types of work desks or chairs can make them aware of the possibilities such new equipment offers to decrease sitting, and they may be tempted to try them. This would hypothetically replace sitting with some other activity, while allowing the usual tasks to be carried out with the same efficiency. Changing the layout of the workplace by, for example, placing printers away from desks would force employees to stand up and walk to obtain their printouts.

Policies to change the organisation of work

Organisational policies could support the formation of walking or exercise groups at the workplace or conducting walking meetings. Formation of walking or exercise groups or conducting walking meetings, might help individuals to reduce sitting and might also help them encourage each other to adapt new behaviours. The provision of purposive short breaks (with the aim of reducing sitting) might help workers engage in such activities more frequently. The breaks might also encourage employees to take a walk to communicate with colleagues instead of using the telephone or email. Standing meeting rooms would provide an opportunity for office employees to reduce their sitting time.

Provision of information and counselling

Sedentary workers could be made aware of the importance of reducing their time spent in sedentary behaviour. They could be informed about health risks and the benefits of reducing time spent sitting and replacing it with time spent in a more physically demanding behaviour. In Wilks 2006, it was found that employees who had received information regarding the health risks of sitting were more likely to use a sit‐stand desk more frequently than those who had not. Even if people are aware of the adverse effects of excessive sitting, and have access to facilities and programs to decrease sitting, they might still find difficulties in adapting to new behaviour. It requires conscious effort for a person to interrupt their normal sitting behaviour and engage in physical activity while at work. To facilitate behaviour change, people could be provided with point‐of‐choice prompts or counselling, which might enable individuals to evaluate their behavioural choices and motivate them to adopt healthy ones. Points‐of‐choice prompts can be delivered through various means such as signs, emails, text messages, or telephone calls, to motivate change of behaviour. A prompting software can be installed on an employee's personal computer, so that a one‐minute reminder to take a break appears on their screen every 30 minutes (Evans 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Interventions to decrease sitting at work are becoming increasingly popular, but it is unclear whether they are effective in the long term or not (Healy 2013). Therefore, there is a need to evaluate whether sitting at work can be reduced by interventions, and to compare the effectiveness of various types of such interventions.

Although some studies have shown that sit‐stand desks and walking strategies have been useful in reducing sitting, no significant difference in the duration of individual bouts of sitting was found in Straker 2013. Another study did not find a significant effect of strategies to increase walking on sitting behaviour (Gilson 2009), while in Evans 2012, it was found that point‐of‐choice prompting software along with education was superior to education alone. Such inconsistency in the findings from individual studies means it is unclear whether workplace interventions for reducing sitting are effective, and whether different types of interventions differ in their effectiveness.

Possibly because of the variation in results across studies, recommendations for reducing sitting at work vary. In recent years, several countries, such as the UK and Australia (Australian Government 2014; Department of Health 2011), have incorporated sedentary behaviour recommendations as part of their physical activity guidelines. These guidelines, however, only propose potential strategies for reducing sitting time without quantifying the recommended total duration of sitting time. In 2015, an international group of experts recommended that desk‐based employees should aim towards accumulating two hours of standing and light activity (light walking) per day during working hours, eventually progressing to a total accumulation of four hours per day. To achieve this, they recommended breaking up sitting time with standing by using sit–stand desks or by taking short active standing breaks (Buckley 2015). While all these guidelines stress the evidence of the adverse effects of sitting on health, there is little evidence that different interventions aiming to reduce sitting can help individuals meet any of these recommendations. Furthermore, since this topic is of increasing interest, it is likely that the availability of evidence will increase in the near future. A Cochrane systematic review will ensure timely updating of this information for decision makers.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of workplace interventions for reducing sitting at work compared to no intervention or alternative interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cross‐over RCTs, cluster‐RCTs, and quasi‐RCTs. Quasi‐RCTs are trials that allocate participants to the intervention or control group using a method of randomisation that is not actually random. At workplaces, interventions operate at group level and may therefore be difficult to deliver to individuals (Ijaz 2014). Since it is more difficult to randomise units when the intervention is implemented at a higher aggregate level, we also included controlled before‐and‐after studies (CBAs) that used a concurrent control group for the interventions that aimed to change workplace arrangements.

Types of participants

We included all studies conducted with participants aged 18 years or more, whose occupations involved spending the majority of their working time sitting at a desk, such as administrative workers, customer service operators, help‐desk professionals, call‐centre representatives, and receptionists.

We excluded studies that addressed transportation work. People working in the transportation industry (such as taxi drivers, truck drivers, bus drivers, and airline pilots) and who operate heavy equipment (such as crane operators and bulldozer operators) are also exposed to prolonged sitting, but current technology provides very limited options for implementing interventions to decrease sitting in such occupations. Reducing sitting in people who work in the transportation industry and operate heavy machinery would require specific interventions that could be the scope of another review.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Physical changes in the workplace design and environment

Changes in the layout of the workplace, such as placing printers away from office desks.

Changes in desks enabling more physical activity, such as the use of sit‐stand desks, vertical workstations on treadmills, desk cycle/cycling desks, or stepping devices.

Changes in chairs enabling more physical activity, such as inflated balloon chairs or therapy balls.

Policies to change the organisation of work

Walking meetings and walking or other exercise groups during work time.

Breaks (periodic, frequent, or purposive) to sit less, stand up, and take an exercise break.

Sitting diaries.

Provision of information and counselling

Signs or prompts at the workplace (e.g. posters) or at the workstation (computer).

E‐health intervention.

Distribution of leaflets.

Counselling (face to face, by email, or by telephone).

Multi‐component interventions

Interventions that included elements from all the three above‐mentioned categories.

Comparison

We compared the interventions described above with no intervention or with other interventions.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We included studies that evaluated sitting at work measured either as:

self‐reported time spent sitting at work by questionnaires; or

device‐based measures of sitting assessed by means of an accelerometer‐inclinometer, which assesses intensity of physical activity and body posture (Kanoun 2009; Kim 2015); or

self‐reported or device‐based measures of time spent in prolonged sitting bouts (e.g. 30 minutes or more) and number of such bouts.

Secondary outcomes

Estimated energy expenditure in metabolic equivalent (MET) hours per workday as a proxy measure to detect changes in sitting time.

Self‐reported or device‐measured total time spent sitting, including sitting at and outside work.

Self‐reported or device‐measured time spent standing and stepping at work.

Work productivity.

Adverse events including any reported musculoskeletal symptoms due to prolonged standing as a possible side‐effect of using a sit‐stand desk.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched for all eligible published and unpublished trials in any language. We were prepared to translate non‐English language abstracts for potential inclusion. Our search strategy was based on types of study population, types of study design, work‐related aspects, and outcomes related to sitting, and it consisted of keywords generated with the help of a thesaurus, such as 'seated posture'.

We searched the following electronic databases from inception to 9 August 2017 for identifying potential studies:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Appendix 1);

MEDLINE (searched through Ovid; Appendix 2);

Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; Appendix 3);

Occupational Safety and Health Database (OSH UPDATE; Appendix 4);

Excerpta Medica dataBASE (Embase; Appendix 5);

PsycINFO (searched through Ovid; Appendix 6);

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/; Appendix 7); and

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/; Appendix 8).

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all included studies and systematic reviews for additional trials. We contacted experts in the field and authors of included studies to identify additional unpublished or ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NS, KKH) independently screened titles and abstracts of the documents found in our systematic search, to identify potential studies for inclusion. The same authors marked citations as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. We retrieved full‐text study reports or publications for all citations considered potentially relevant. Two authors (NS, KKH) independently assessed the retrieved full‐texts to identify eligible studies for inclusion. We recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We resolved disagreements through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third author (SI). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to create a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection template to extract study characteristics and outcome data. We extracted the following information.

Methods: study location, date of publication, type of study design, study setting.

Participants: number randomised or recruited, mean age or age range, gender, inclusion and exclusion criteria of the trial, occupation, number of withdrawals, similarity of study groups in age, gender, occupation, and sitting time at baseline.

Interventions: description of intervention methods and randomised groups, duration of active intervention, duration of follow‐up, and description of comparisons, interventions and co‐interventions.

Outcomes: description of primary and secondary outcomes and their assessment methods.

Notes: source of funding for the trial and potential conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Two review authors (NS and either VH or SI) independently extracted outcome data from the included studies. We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table when trial authors did not report outcome data in a usable way. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by involving a third author (either SI or VH). One review author (NS) transferred data into Cochrane's statistical software, Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked that we had entered the data correctly. For this purpose we tabulated extracted information about studies in a spreadsheet before entry into Review Manager. A review author (JV) spot‐checked a random 20% of extracted data for accuracy against the trial report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (NS and either VH or SI) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion or by involving another author (ZP). We assessed the included studies' risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Validity of outcome measure

Baseline comparability/imbalance for age, gender and occupation of study groups

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgment in the 'Risk of bias' tables. We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains. Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted it as such in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

We judged studies as being at low risk for selective outcome reporting, if the publications of the trial followed what had been planned and had been registered in international databases (trial registries), such as ClinicalTrials.gov, Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (anzctr.org.au/), or Netherlands Trial Registry (trialregister.nl). We judged the studies that were not registered in trial registries as being at low risk for selective outcome reporting if they had reported all the outcomes mentioned in their methods section.

We judged a study to be at low risk of bias overall when the study included a sufficiently detailed description of its random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, complete outcome data, no selective outcome reporting, and valid outcome measures, that is, all the domains had a low risk of bias. We judged a study to have a high risk of bias when it reported a feature that would be judged as having a high risk of bias in any one of the eight domains. We did not assess blinding of participants or study personnel for risk of bias, as it is very difficult to blind either of them in studies that are trying to modify sedentary behaviour.

Measures of treatment effect

We entered the outcome data for each study into the data tables in Review Manager to calculate the pooled treatment effects. We used risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MDs) for continuous outcomes. Where only effect estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or standard errors were reported in studies, we entered these data into Review Manager using the generic inverse variance method.

Unit of analysis issues

For cluster‐RCTs that did not present results accounting for clustering effect, we calculated these assuming a large intra‐cluster correlation coefficient of 0.10. We based this assumption on a realistic estimate by analogy on studies about implementation research (Campbell 2001). We transformed all measurement units for sitting at work into minutes per eight‐hour workday where needed and possible, and assumed the data referred to a five‐day work week, if this was not reported.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted researchers or study sponsors to verify key study characteristics and obtain missing information or full‐text reports. When we did not find a full study report even after contacting authors listed in the respective abstract, we categorised the references as Studies awaiting classification.

For missing data not obtained from authors, such as standard deviations, we calculated these following the advice in the Cochrane Handbook section 16.1.2 (Higgins 2011). We tested the inclusion of studies with missing data and any imputations in sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical homogeneity of the results of included studies based on similarity of populations, interventions, outcomes, and follow‐up times. We considered populations to be similar when the participants were 18 years or older and their occupations involved sitting for a major part of their working time. We considered interventions to be similar when their working mechanisms were similar, for example, replacing sit‐desks with sit‐stand desks (see Types of interventions). We regarded follow‐up times of three months or less as short‐term, between three months and one year as medium‐term, and more than one year as long‐term.

We quantified the degree of heterogeneity using the I² statistic, where an I² value of 25% to 50% indicates a low degree of heterogeneity, 50% to 75% a moderate degree of heterogeneity, and more than 75% a high degree of heterogeneity. If we identified moderate to high heterogeneity, we reported it and explored possible causes by pre‐specified subgroup analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

When ten or more studies were included in a meta‐analysis, we tested for the effect of small studies using a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

We analysed the effects of interventions in the categories defined in Types of interventions: physical changes in the workplace design and environment (changes in desks; changes in chairs); policies to change the organisation of work (supporting social environment and policies for breaks); or provision of information and counselling. We pooled effect size estimates from individual studies using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We considered studies to be heterogeneous, and therefore used a random‐effects model to calculate pooled effect sizes.

We calculated the prediction interval for the outcome sitting time at work for sit‐stand desks compared to sit‐desks. Prediction intervals give an estimate of the effect of a new study based on the heterogeneity of effects of studies included in the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2009; IntHout 2016).

'Summary of findings' table

We reported time spent sitting at work and time spent in sitting bouts of 30 minutes or more at short‐term follow‐up in the 'Summary of findings' table. Where study authors did not report effects in the short‐term follow‐up for the outcomes mentioned above, we presented results at medium‐term follow‐up. We only reported the most relevant comparisons. We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence that contributed data to the meta‐analyses for these outcomes (Higgins 2011). We justified all decisions to downgrade or upgrade the quality of evidence using footnotes and we made comments to aid readers’ understanding of the review where necessary.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If sufficient data become available in future updates of this review we will conduct the following subgroup analyses for the primary outcome of time spent sitting at work.

Age: we will compare studies conducted in participants aged 18 to 40 years with studies where all participants were aged 41 years or older, as the probability of maintaining good health and fitness diminishes with older age (AIHW 2008). Older employees might also expect a larger health benefit due to a reduction in sitting (Manini 2015).

Types of outcome measure: we will carry out a subgroup analysis by type of outcome measure, that is, self‐reported (e.g. questionnaire, log book) versus accelerometer/inclinometer versus Ecological Momentary Assessment.

Types of intervention: we will carry out a subgroup analysis for different interventions that have been pooled under a broader category of intervention.

Similarly, we will assess the robustness of our results by excluding studies we judge to have a high risk of bias from all meta‐analyses.

Results

Description of studies

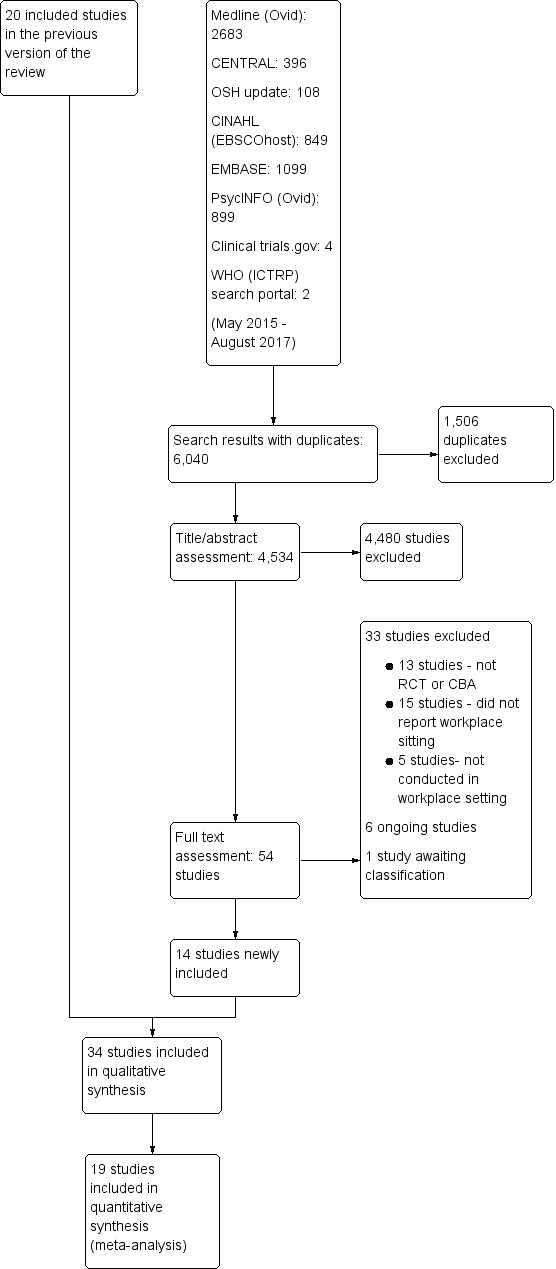

See: Figure 1, Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification, and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA study flow diagram

Results of the search

We conducted systematic searches in selected electronic databases and grey literature sources. We identified altogether 12,368 references in the initial search (December 2013) and the first search update (June 2015), and retrieved a total of 92 references for full‐text scrutiny. Of these, we excluded 72 articles and included 20 studies in the previous published version of this review. For this update, we searched the electronic databases from June 2015 until 9 August 2017. The updated search identified a total of 6,040 references, as outlined in Figure 1: 396 from CENTRAL (Appendix 1; 9 August 2017); 2683 from MEDLINE (searched through Ovid, Appendix 2; 9 August 2017); 849 from CINAHL (Appendix 3; 9 August 2017); 108 from OSH UPDATE (Appendix 4; 9 August 2017); 1099 from Embase (Appendix 5; 9 August 2017); 899 from PsycINFO (Appendix 6; 9 August 2017); 4 from ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 7; 9 August 2017); and 2 from the WHO trials search portal (Appendix 8; 9 August 2017). Removal of duplicates reduced the total number of references to 4,534. Based on their titles and abstracts, we selected 54 of these references for full‐text reading. Out of these, we excluded 33 studies. Six studies are ongoing and one study was not available in full text so we classified it as a study awaiting classification. This resulted in 14 studies being included in this review update in addition to the 20 studies already included in the previous version of the review.

Included studies

Study design

Out of the 34 included studies, 17 are RCTs, two are cross‐over RCTs, seven are cluster‐RCTs, and eight are controlled before‐and‐after studies with concurrent controls. See Characteristics of included studies for further details. Although the authors described their studies as quasi‐RCTs, we categorised Alkhajah 2012, and Neuhaus 2014a, as controlled before‐and‐after studies because the risk of baseline differences for studies with only two clusters is very high. Only one cluster trial reported unadjusted results (De Cocker 2016). Therefore we adjusted their results for the design effect following the methods stated in Section 16.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for the calculations (Higgins 2011).

We considered randomised and non‐randomised studies as similar if there were no considerable differences in their effect estimates (Alkhajah 2012; Chau 2014; Chau 2016; Dutta 2014; Graves 2015; Healy 2013; Li 2017; MacEwen 2017; Neuhaus 2014a; Tobin 2016), but explored any potential differences in a subgroup analysis.

For meta‐analyses that included two arms of the same study, we halved the number of participants in the control group (Coffeng 2014; De Cocker 2016; Neuhaus 2014a). For Coffeng 2014, we used the unadjusted results at twelve months follow‐up. In other comparisons we used the adjusted values with the generic inverse variance method. One included study (Neuhaus 2014a) reported only MDs and standard errors and the authors could not provide raw data, so we could not adjust the number of participants. In this case we modelled the means and standard deviations from the intervention and the control group in Review Manager as closely to the real data as possible to achieve the same MD and standard error. Then we halved the number of participants in the control group and entered the resulting standard errors into Review Manager.

Participants

The included studies were conducted with a total of 3,397 employees. The sample sizes of included trials ranged from 16 in the smallest study (Chau 2016), to 523 in the largest one (Verweij 2012), with a median of 44. Studies included workers from the public and private sectors, with nine studies including researchers and other academic staff, two studies including health workers, and 23 including employees in private companies.

Gender

Participants in 20 studies were predominantly women (Carr 2015; Danquah 2017; De Cocker 2016; Donath 2015; Dutta 2014; Evans 2012; Gao 2015; Gilson 2009; Graves 2015; Healy 2016; Kress 2014; Li 2017; MacEwen 2017; Mailey 2016; Pickens 2016; Priebe 2015; Schuna 2014; Swartz 2014; Tobin 2016; Urda 2016). In the remaining 14 studies the proportions of women and men did not differ significantly.

Country

The studies were conducted in Australia, the USA, Canada, and several high‐income countries in Europe.

Interventions

1. Physical changes in the workplace design and environment

Sixteen studies evaluated the effectiveness of individual workspace modifications on workplace sitting time (Alkhajah 2012; Carr 2015; Chau 2014; Chau 2016; Dutta 2014; Gao 2015; Graves 2015; Healy 2013; Kress 2014; Pickens 2016; Li 2017; MacEwen 2017; Neuhaus 2014a; Schuna 2014; Sandy 2016; Tobin 2016)

Sit‐stand desk

Twelve studies assessed the effectiveness of interventions using sit‐stand desks. The interventions using a sit‐stand desk were assessed independently (Alkhajah 2012; Chau 2014; Dutta 2014; Gao 2015; MacEwen 2017; Neuhaus 2014a), and in combination with information and counselling (Chau 2016; Graves 2015; Healy 2013; Li 2017; Neuhaus 2014a; Tobin 2016).

One study compared the effectiveness of multiple types of interventions, including: 1) sit‐stand desk; 2) ergonomic training; 3) sit‐stand desk combined with ergonomic training; and 4) standard sit‐desk (Sandy 2016).

Standing desk

Two studies compared the effectiveness of a standing desk intervention and a sit‐stand desk intervention (Kress 2014; Pickens 2016).

Active workstation

Two studies evaluated the effectiveness of interventions using active workstations (i.e. desks that cause significant increase in energy expenditure compared to conventional sit‐desks). One study assessed the effectiveness of a treadmill desk (Schuna 2014), while another assessed the effectiveness of a cycle desk (Carr 2015).

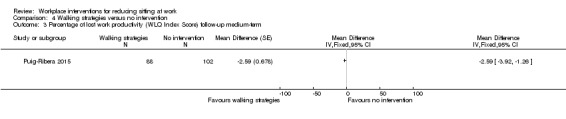

2. Policy to change the organisation of work

Two studies evaluated the effectiveness of walking strategies (Gilson 2009; Puig‐Ribera 2015). The first evaluated the effectiveness of route and incidental walking on office employees' sitting time at work (Gilson 2009). The route‐based walking intervention was intended to increase the amount of brisk, sustained walking during work breaks. The incidental walking intervention aimed to increase walking and talking to colleagues, instead of sending emails or making telephone calls, and standing and walking during meetings, instead of sitting at desks. The other study evaluated the effectiveness of incidental movement and short (5 to 10 minutes) and longer (10+ minute) walks on office employees' sitting time at work (Puig‐Ribera 2015).

One study evaluated the effectiveness of planned daily breaks from sitting (Mailey 2016). They compared taking short breaks (one to two minutes every half hour) to taking long breaks (two 15‐minute breaks per workday).

3. Provision of information and counselling

Information and feedback

One study evaluated the effectiveness of personalised computer‐tailored feedback and generic feedback intervention in reducing sitting time in office employees (De Cocker 2016). Another compared the effectiveness of delivering emails containing psychosocial materials and other available resources that were based on constructs of Social Cognitive Theory relating to decreasing sedentary behaviours at work, to delivering emails concerning general health topics (Gordon 2013). In Priebe 2015, the effectiveness of providing highly personalised or contextualised information was compared with the effectiveness of providing less personalised or contextualised information.

Counselling

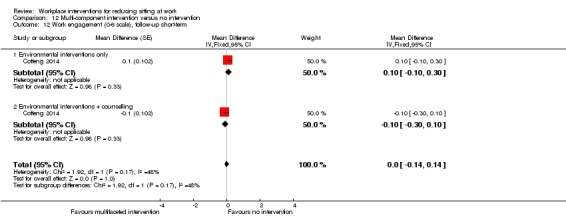

In Verweij 2012, the effectiveness of counselling by occupational physicians (highly trained specialists who provide health services to employees and employers (AFOEM 2014)) was compared with usual care in decreasing sitting time in office employees. Another study evaluated the effectiveness of group motivational interviewing (i.e. a counselling style that stimulates behavioural change by focusing on exploring and resolving ambivalence in a group) by occupational physicians on office employees' sitting time (Coffeng 2014).

Computer prompts

Four studies evaluated the effectiveness of computer prompts combined with information, compared to information alone, for decreasing sitting time in office employees (Donath 2015; Evans 2012; Pedersen 2013; Urda 2016). Computer prompts offer an opportunity to employees to choose and engage in a short 'burst' of physical activity such as standing or walking. One study, Swartz 2014, assessed the effect of hourly prompts (computer‐based and wrist worn) to stand up or to step on reducing sitting time in office employees.

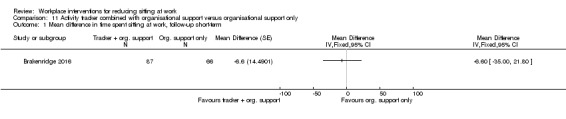

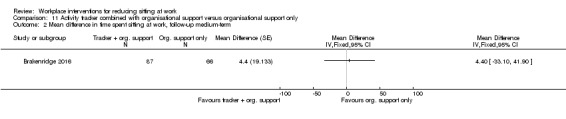

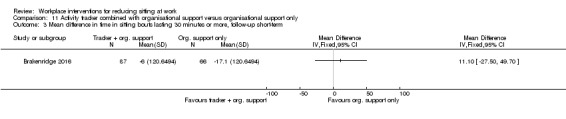

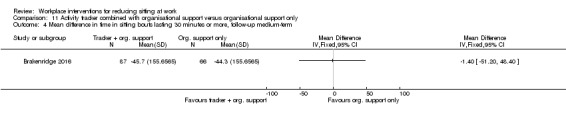

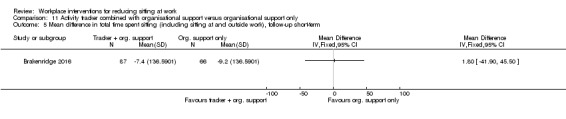

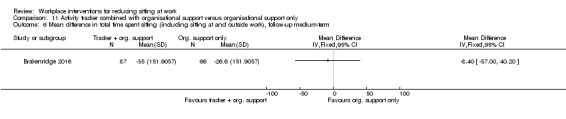

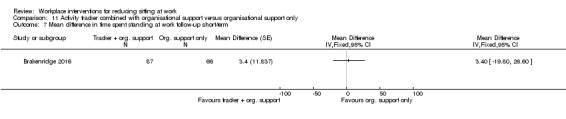

One study, Brakenridge 2016, assessed the effectiveness of activity tracker combined with organisational support compared to organisational support only.

One study, van Berkel 2014, evaluated the effectiveness of mindfulness training in decreasing sitting time in office employees. The mindfulness intervention consisted of homework exercises and information through emails.

4. Multi‐component interventions

Four studies evaluated the effectiveness of combining multiple interventions on sitting at work (Coffeng 2014; Danquah 2017; Ellegast 2012; Healy 2016).

In Coffeng 2014, the effectiveness of combining multiple environmental interventions with Group Motivational Interviewing (GMI) was assessed. The multi‐component environmental intervention consisted of: 1) the Vitality in Practice (VIP) Coffee Corner Zone, where a workplace coffee corner was modified by adding a bar with bar chairs, a large plant, and a giant wall poster (a poster visualizing a relaxing environment, e.g. wood, water, and mountains); 2) the VIP Open Office Zone, where an office was modified by introducing exercise balls and curtains to divide desks in order to reduce background noise; 3) the VIP Meeting Zone, where conference rooms were modified by placing a standing table and a giant wall poster; and 4) the VIP Hall Zone, where table tennis tables were placed and lounge chairs were introduced in the hall for informal meetings. In addition, footsteps were placed on the floor in the entrance hall to promote stair walking.

In Ellegast 2012, the effectiveness of multiple environmental interventions in combination with a walking strategy were assessed. The intervention consisted of measures aiming to change workplace environment (e.g. sit‐stand tables) and behaviour (e.g. using pedometers to provide activity feedback, face‐to‐face motivation for lunch walks, and an incentive system for bicycle commuting or sports activities).

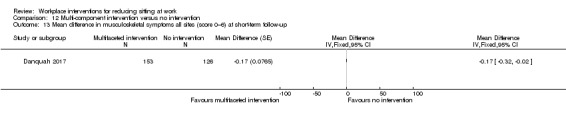

The study by Danquah and colleagues evaluated the effectiveness of a multi‐component intervention comprising of organisational strategies (support from management), environmental strategies (installation of standing meeting tables), and individual strategies (a lecture and email or text messages) (Danquah 2017).

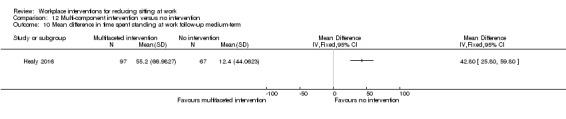

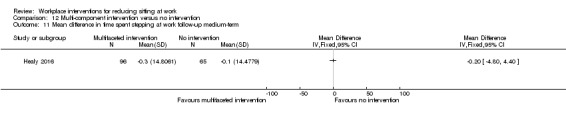

The fourth study evaluated the effectiveness of a multi‐component intervention comprising of organisational strategies (consultation and support from the management), environmental strategies (sit‐stand desk), and individual strategies (coaching and goal setting) (Healy 2016).

Type of control group

No intervention

Twenty‐three included studies used a 'no intervention' control group (Alkhajah 2012; Chau 2014; Chau 2016; Coffeng 2014; Danquah 2017; De Cocker 2016; Dutta 2014; Ellegast 2012; Gao 2015; Gilson 2009; Graves 2015; Healy 2013; Healy 2016; Li 2017; MacEwen 2017; Neuhaus 2014a; Puig‐Ribera 2015; Sandy 2016; Schuna 2014; Tobin 2016; Urda 2016; van Berkel 2014; Verweij 2012).

Other controls

In Carr 2015, a cycle desk in combination with information and counselling was compared with information and counselling only, resulting in the net effect of a cycle desk. In Kress 2014, and Pickens 2016, the effectiveness of standing desks was compared with the effectiveness of sit‐stand desks. Three studies compared computer prompts combined with information with information only, resulting in the net effect of computer prompts (Donath 2015; Evans 2012; Pedersen 2013). In Gordon 2013, the effectiveness of delivering emails concerning general health topics was compared with delivering emails containing psychosocial materials and other available resources based on constructs of the Social Cognitive Theory relating to decreasing sedentary behaviours at work. In Swartz 2014, computer‐based and wrist‐worn prompts, combined with instruction to stand, were compared with the same prompts combined with instruction to walk at least 100 steps. In Priebe 2015, highly personalised information was compared with less personalised information. One study evaluated the effectiveness of short breaks compared to long breaks (Mailey 2016). Another study compared the effectiveness of activity trackers combined with organisational support with organisational support only (Brakenridge 2016).

Outcomes

Total time spent sitting at work

Total time spent sitting at work was used as an outcome variable in 24 studies (Alkhajah 2012; Brakenridge 2016; Chau 2014; Chau 2016; Danquah 2017; De Cocker 2016; Donath 2015; Dutta 2014; Ellegast 2012; Gilson 2009; Gordon 2013; Graves 2015; Healy 2013; Healy 2016; Kress 2014; Li 2017; MacEwen 2017; Neuhaus 2014a; Pedersen 2013; Puig‐Ribera 2015; Sandy 2016; Swartz 2014; Tobin 2016; Urda 2016).

Eight studies reported time spent in occupational sedentary behaviour, which we considered to be equivalent to time spent sitting at work (Carr 2015; Coffeng 2014; Gao 2015; Mailey 2016; Pickens 2016; Schuna 2014; Verweij 2012; van Berkel 2014).

Number of prolonged sitting bouts at work

Three studies reported number of prolonged sitting bouts at work (Evans 2012; Danquah 2017; Swartz 2014).

Total duration of prolonged sitting bouts at work

Six studies reported time spent in prolonged periods of sitting at work (Brakenridge 2016; Danquah 2017; Evans 2012; Healy 2013; Neuhaus 2014a; Priebe 2015).

Total time spent sitting, including sitting at and outside work

Eight studies reported total time spent sitting, including sitting at and outside work (Alkhajah 2012; Brakenridge 2016; De Cocker 2016; Dutta 2014; Ellegast 2012; Healy 2016; MacEwen 2017; Verweij 2012).

Time spent standing and stepping at work

Sixteen studies reported time spent standing at work (Alkhajah 2012; Brakenridge 2016; Chau 2014; Chau 2016; Danquah 2017; De Cocker 2016; Donath 2015; Gao 2015; Graves 2015; Healy 2013; Healy 2016; Li 2017; MacEwen 2017; Neuhaus 2014a; Swartz 2014; Tobin 2016).

Eleven studies reported time spent stepping at work (Alkhajah 2012; Brakenridge 2016; Chau 2014; Chau 2016; Graves 2015; Healy 2013; Healy 2016; Li 2017; Neuhaus 2014a; Swartz 2014; Tobin 2016).

Energy expenditure

Only one study reported estimated energy expenditure based on information about sitting time at work (Pedersen 2013). They used 1.5 METs to represent energy expenditure of sitting and 2.3 METs to represent energy expenditure of quiet standing.

Work productivity

Three studies assessed work performance on a scale from 1 to 10 (Alkhajah 2012; Healy 2013; Neuhaus 2014a). One study, Carr 2015, also reported they had assessed work productivity, but the authors did not report the results.

Two studies assessed work engagement on a scale from 0 to 6 (Coffeng 2014; van Berkel 2014), using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, a questionnaire that measures three aspects of engagement: vigour (six items); dedication (five items); and absorption (six items).

One study, Puig‐Ribera 2015, reported the percentage of lost work productivity in terms of Work Limitation Questionnaire Index (WLQ Index) Score. WLQ Index Score is a weighted sum of the scores from the WLQ scales. The Work Limitation Questionnaire consists of 25 items which require employees to rate their level of difficulty to perform 25 specific job demands in the last two weeks. The individual items form four scales: Time management; Physical demands; Mental or Interpersonal, and Output demands scale.

Adverse events

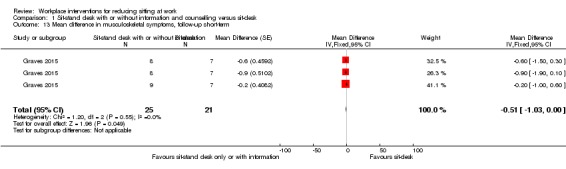

Three studies reported musculoskeletal symptoms by anatomical regions (Alkhajah 2012; Healy 2013; Neuhaus 2014a). Two studies reported musculoskeletal discomfort or pain at three sites: lower back, upper back, and neck and shoulders (Gao 2015; Graves 2015). The first study, Gao 2015, used a scale ranging from 1 (very comfortable) to 5 (very uncomfortable); and in Graves 2015, a scale ranging from 0 (no discomfort) to 10 (extremely uncomfortable) was used. Another study, Carr 2015, also reported having measured musculoskeletal discomfort but they presented no respective data in their article. One study, Danquah 2017, reported musculoskeletal symptoms at all sites on the scale from 0 to 6.

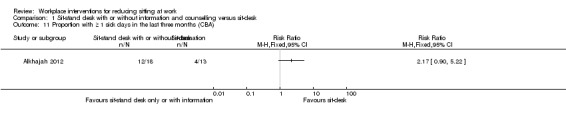

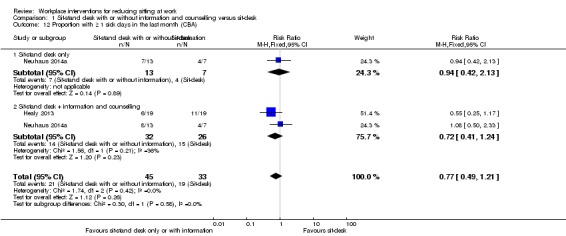

One study measured adverse events as 'one sick day in the last three months' (Alkhajah 2012), whilst two studies used 'more than one sick day in the last month of intervention' (Healy 2013; Neuhaus 2014a).

In Neuhaus 2014a, adverse events were defined as overall body pain.

Follow‐up times

In six studies the longest follow‐up was one month or less (Evans 2012; Healy 2013; Li 2017; Priebe 2015; Swartz 2014; Urda 2016), and in 20 studies the longest follow‐up was between one and three months (Alkhajah 2012; Brakenridge 2016; Chau 2014; Chau 2016; Danquah 2017; De Cocker 2016; Donath 2015; Dutta 2014; Ellegast 2012; Gilson 2009; Gordon 2013; Graves 2015; Healy 2016; Kress 2014; MacEwen 2017; Mailey 2016; Neuhaus 2014a; Pickens 2016; Schuna 2014; Tobin 2016). We categorised all these as short‐term follow‐up.

The remaining eight studies followed participants between three and 12 months (Carr 2015; Coffeng 2014; Gao 2015; Pedersen 2013; Puig‐Ribera 2015; Sandy 2016; van Berkel 2014; Verweij 2012), which we categorised as medium‐term follow‐up.

No studies had a follow‐up longer than 12 months, which we defined as long‐term follow‐up.

Excluded studies

Of the 54 papers we assessed as full‐text, 33 did not meet our inclusion criteria and we summarily excluded them. Thirteen studies were not RCTs or controlled before‐and‐after studies with concurrent controls. Five studies were not conducted in a workplace setting and another 15 studies did not report sitting time at work. See the Characteristics of excluded studies table for further details.

Risk of bias in included studies

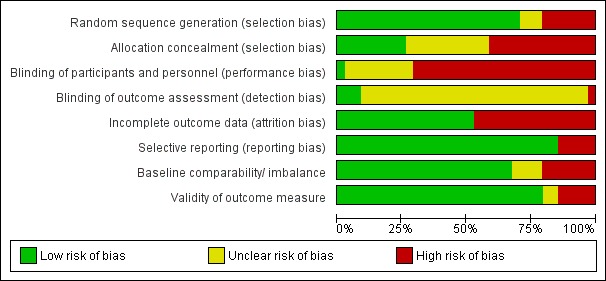

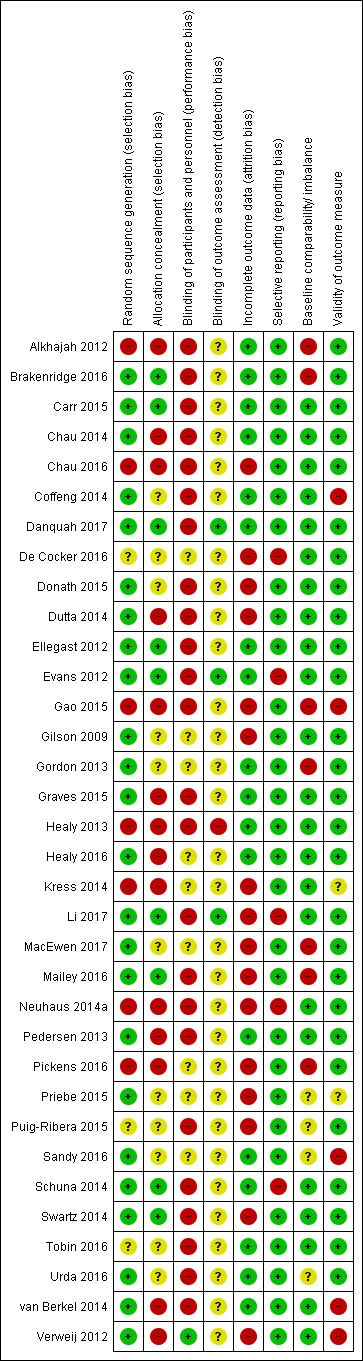

Risk of bias varied considerably across the studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Seven studies, Alkhajah 2012, Chau 2016, Gao 2015, Healy 2013, Kress 2014, Neuhaus 2014a, Pickens 2016, did not randomise participants and we judged these studies to be at high risk of bias for the domain of random sequence generation. Except for De Cocker 2016, Puig‐Ribera 2015, and Tobin 2016, all the studies described the method of randomisation they had used, so we judged them as having a low risk of bias for the domain of sequence generation. Although these studies mentioned in their publication they conducted randomised trials (De Cocker 2016; Puig‐Ribera 2015; Tobin 2016), they did not describe the method of randomisation and so we judged them to have an unclear risk of bias. One study, Donath 2015, used the minimisation method which is considered equivalent to randomisation (Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Higgins 2011).

Only nine studies reported concealing intervention versus control group allocation, so we judged these studies to be at low risk of bias (Brakenridge 2016; Carr 2015; Danquah 2017; Ellegast 2012; Evans 2012; Li 2017; Mailey 2016; Schuna 2014; Swartz 2014). Eleven studies provided no information on allocation concealment, thus we judged these studies to be at unclear risk of bias (Coffeng 2014; De Cocker 2016; Donath 2015; Gilson 2009; Gordon 2013; MacEwen 2017; Priebe 2015; Puig‐Ribera 2015; Sandy 2016; Tobin 2016; Urda 2016). Allocation was not concealed in the remaining studies (Alkhajah 2012; Chau 2014; Chau 2016; Dutta 2014; Gao 2015; Graves 2015; Healy 2013; Healy 2016; Kress 2014; Neuhaus 2014a; Pedersen 2013; Pickens 2016; van Berkel 2014; Verweij 2012) and thus we judged them to be at high risk of bias.

Blinding

In all but a single study (Verweij 2012), the blinding of participants to the interventions they were receiving was not done due to the nature and aims of interventions being self‐evident, so we judged that these 33 studies had a high risk of bias in the performance bias domain. The single study, Verweij 2012, reported asking randomised occupational physicians not to reveal their allocation to participating employees who were their patients.

With regard to outcome assessment, only three studies reported blinding of outcome assessor to group allocation and thus we judged them to have a low risk of bias (Danquah 2017; Evans 2012; Li 2017). One study, Healy 2013, reported that outcome assessors were not blinded to group allocation and we judged their study to have a high risk of bias. The remaining studies did not report on blinding of outcome assessors and thus we judged them to have an unclear risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged 16 studies to have a high risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data (Chau 2016; De Cocker 2016; Donath 2015; Dutta 2014; Gao 2015; Gilson 2009; Kress 2014; Li 2017; MacEwen 2017; Mailey 2016; Neuhaus 2014a; Pickens 2016; Priebe 2015; Puig‐Ribera 2015; Swartz 2014; Verweij 2012). One study, Dutta 2014, did not report 14% of working hours; the remaining studies lost more than 10% of participants during the follow‐up period. We judged all the remaining 18 studies to have a low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data because of the following reasons. Three studies, Gordon 2013, Graves 2015, and van Berkel 2014, conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis. One study, Coffeng 2014, conducted multilevel analysis to account for missing data. Another, Chau 2014, reported that imputing values for missing covariate data did not influence the estimated adjusted effects of the intervention on the outcomes. Three studies, Brakenridge 2016, Danquah 2017, and Healy 2016, reported assessing sensitivity of results by multiple imputation using chained equations. Another three studies, Evans 2012, Healy 2013, and Tobin 2016, lost the same proportion of participants from both the intervention groups and the control groups, so we assumed that the missing data was unlikely to have had a significant impact on outcomes (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, section 8.13.2,Higgins 2011).

Selective reporting

We judged five studies to have a high risk of bias due to discordance between outcomes in available protocols and the ones reported in study results (De Cocker 2016; Evans 2012; Li 2017; Neuhaus 2014a; Schuna 2014). We judged the remaining 17 studies to have a low risk of bias as they reported results for all the outcome measures mentioned either in the protocol or in the methods section of studies where a protocol was not available (Alkhajah 2012; Chau 2014; Coffeng 2014; Donath 2015; Dutta 2014; Gao 2015; Gilson 2009; Gordon 2013; Healy 2013; Pedersen 2013; Puig‐Ribera 2015; Schuna 2014; Swartz 2014; van Berkel 2014; Verweij 2012).

Other potential sources of bias

This domain had the following two parts of assessment, as decided a priori:

validity of outcome measure;

baseline comparability or imbalance for age, gender and occupation of study groups.