Abstract

Background

Phosphate binders are used to reduce positive phosphate balance and to lower serum phosphate levels for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) with the aim to prevent progression of chronic kidney disease‐mineral and bone disorder (CKD‐MBD). This is an update of a review first published in 2011.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess the benefits and harms of phosphate binders for people with CKD with particular reference to relevant biochemical end‐points, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular morbidity, hospitalisation, and death.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 12 July 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs of adults with CKD of any GFR category comparing a phosphate binder to another phosphate binder, placebo or usual care to lower serum phosphate. Outcomes included all‐cause and cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, adverse events, vascular calcification and bone fracture, and surrogates for such outcomes including serum phosphate, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and FGF23.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected studies for inclusion and extracted study data. We applied the Cochrane 'Risk of Bias' tool and used the GRADE process to assess evidence certainty. We estimated treatment effects using random‐effects meta‐analysis. Results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes together with 95% confidence intervals (CI) or mean differences (MD) or standardised MD (SMD) for continuous outcomes.

Main results

We included 104 studies involving 13,744 adults. Sixty‐nine new studies were added to this 2018 update.

Most placebo or usual care controlled studies were among participants with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis (15/25 studies involving 1467 participants) while most head to head studies involved participants with CKD G5D treated with dialysis (74/81 studies involving 10,364 participants). Overall, seven studies compared sevelamer with placebo or usual care (667 participants), seven compared lanthanum to placebo or usual care (515 participants), three compared iron to placebo or usual care (422 participants), and four compared calcium to placebo or usual care (278 participants). Thirty studies compared sevelamer to calcium (5424 participants), and fourteen studies compared lanthanum to calcium (1690 participants). No study compared iron‐based binders to calcium. The remaining studies evaluated comparisons between sevelamer (hydrochloride or carbonate), sevelamer plus calcium, lanthanum, iron (ferric citrate, sucroferric oxyhydroxide, stabilised polynuclear iron(III)‐oxyhydroxide), calcium (acetate, ketoglutarate, carbonate), bixalomer, colestilan, magnesium (carbonate), magnesium plus calcium, aluminium hydroxide, sucralfate, the inhibitor of phosphate absorption nicotinamide, placebo, or usual care without binder. In 82 studies, treatment was evaluated among adults with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, while in 22 studies, treatment was evaluated among participants with CKD G2 to G5. The duration of study follow‐up ranged from 8 weeks to 36 months (median 3.7 months). The sample size ranged from 8 to 2103 participants (median 69). The mean age ranged between 42.6 and 68.9 years.

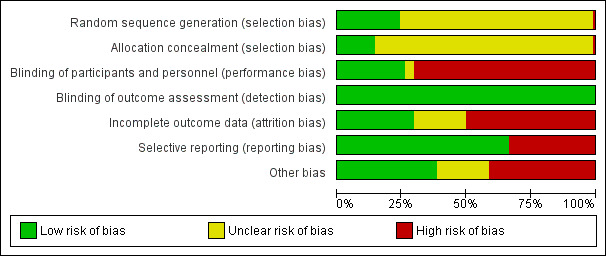

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment were low risk in 25 and 15 studies, respectively. Twenty‐seven studies reported low risk methods for blinding of participants, investigators, and outcome assessors. Thirty‐one studies were at low risk of attrition bias and 69 studies were at low risk of selective reporting bias.

In CKD G2 to G5, compared with placebo or usual care, sevelamer, lanthanum, iron and calcium‐based phosphate binders had uncertain or inestimable effects on death (all causes), cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, fracture, or coronary artery calcification. Sevelamer may lead to constipation (RR 6.92, CI 2.24 to 21.4; low certainty) and lanthanum (RR 2.98, CI 1.21 to 7.30, moderate certainty) and iron‐based binders (RR 2.66, CI 1.15 to 6.12, moderate certainty) probably increased constipation compared with placebo or usual care. Lanthanum may result in vomiting (RR 3.72, CI 1.36 to 10.18, low certainty). Iron‐based binders probably result in diarrhoea (RR 2.81, CI 1.18 to 6.68, high certainty), while the risks of other adverse events for all binders were uncertain.

In CKD G5D sevelamer may lead to lower death (all causes) (RR 0.53, CI 0.30 to 0.91, low certainty) and induce less hypercalcaemia (RR 0.30, CI 0.20 to 0.43, low certainty) when compared with calcium‐based binders, and has uncertain or inestimable effects on cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, fracture, or coronary artery calcification. The finding of lower death with sevelamer compared with calcium was present when the analysis was restricted to studies at low risk of bias (RR 0.50, CI 0.32 to 0.77). In absolute terms, sevelamer may lower risk of death (all causes) from 210 per 1000 to 105 per 1000 over a follow‐up of up to 36 months, compared to calcium‐based binders. Compared with calcium‐based binders, lanthanum had uncertain effects with respect to all‐cause or cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, fracture, or coronary artery calcification and probably had reduced risks of treatment‐related hypercalcaemia (RR 0.16, CI 0.06 to 0.43, low certainty). There were no head‐to‐head studies of iron‐based binders compared with calcium. The paucity of placebo‐controlled studies in CKD G5D has led to uncertainty about the effects of phosphate binders on patient‐important outcomes compared with placebo.

It is uncertain whether the effects of binders on clinically‐relevant outcomes were different for patients who were and were not treated with dialysis in subgroup analyses.

Authors' conclusions

In studies of adults with CKD G5D treated with dialysis, sevelamer may lower death (all causes) compared to calcium‐based binders and incur less treatment‐related hypercalcaemia, while we found no clinically important benefits of any phosphate binder on cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, fracture or coronary artery calcification. The effects of binders on patient‐important outcomes compared to placebo are uncertain. In patients with CKD G2 to G5, the effects of sevelamer, lanthanum, and iron‐based phosphate binders on cardiovascular, vascular calcification, and bone outcomes compared to placebo or usual care, are also uncertain and they may incur constipation, while iron‐based binders may lead to diarrhoea.

Plain language summary

Phosphate binders to prevent complications of chronic kidney disease

What is the issue?

People with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have a reduction in their capacity to remove phosphate from the body via the kidneys, so that phosphate levels in the blood and in body tissues increase as kidney function decreases. This may lead to the development of deposits comprised of calcium plus phosphate in blood vessels and other tissues, together with damage to the skeleton, worsening of kidney failure and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, bone pain, fractures, and death.

Phosphate binders are often prescribed with meals to people with kidney disease, with the intention of reducing the absorption of dietary phosphate from the gastrointestinal tract.

What did we do? This review asked whether phosphate binders influence damage to blood vessels and soft tissues, skeletal changes, kidney function, and risks of cardiovascular disease, bone pain, fractures, and death that accompany worsening kidney failure. We included all clinical studies in which people with CKD were given different phosphate binders (by random chance) for at least eight weeks. We also checked the quality of the information in the studies to learn how certain we could be about the results.

What did we find?

We identified 104 studies of phosphate binders that included 13,744 people. Some studies gave treatment for only eight weeks while some studies treated participants for three years. People in the studies had a range of kidney function, and many were on dialysis. Overall we could not be certain of a number of important outcomes because many of the clinical studies we included had important flaws in their design.

Sevelamer treatment may have decreased death for those patients given this medication when taken instead of calcium. The phosphate binders probably caused constipation, but we could not be very certain about the risks of other side‐effects. We were not very certain whether phosphate binders reduced heart complications, stroke, bone pain, or calcification of blood vessels.

Conclusions

Overall, we are not very sure whether specific phosphate binders are beneficial to patients with CKD. There is a possibility that sevelamer may prevent death compared to calcium‐based binders, but we don't know whether this may be caused by an increased risk of calcium‐based binders, a lower risk with sevelamer treatment, or the possibility that both may be true. Patients need to know that it is not certain whether phosphate binders help to prevent complications of kidney disease, but sevelamer may be preferred to calcium binders.

We did not find differences in the effects of treatment for patients on dialysis and those not on dialysis, although most studies evaluating treatment with calcium‐based binders were among dialysis patients and those comparing binders with placebo were among people not treated with dialysis.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

People with chronic kidney disease (CKD) develop impaired excretion of their dietary phosphate load (Hruska 2008) leading to positive phosphate balance. Hyperphosphataemia leads to a rise in fibroblast growth factor‐23 (FGF23) levels that provide a compensatory increase of renal phosphate excretion and inhibit 1,25 dihydroxy‐vitamin D production and increase its catabolism (Gutiérrez 2005). However, in the presence of further reductions in kidney function, these initial homeostatic responses fail and further increases in serum phosphate and reductions in serum 1,25‐dihydroxy‐vitamin D contribute to an increase in parathyroid hormone (PTH), the actions of which will initially restore calcium and phosphate values toward their normal ranges (Cozzolino 2005; Hruska 2008; Silver 2005). With progression of CKD, these homeostatic responses fail and result in increased risks for hypocalcaemia and hyperphosphataemia that increase PTH release via the calcium‐sensing receptor on parathyroid cells. Prolonged low serum calcium levels lead to stabilisation of mRNA encoding PTH. Reduced 1,25 dihydroxy‐vitamin D levels allow increased transcription of the PTH gene (Kumar 2011). Abnormal serum levels of PTH are observed in 10% of people with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) above 80 mL/min and in 80% of people with a GFR below 20 mL/min (Levin 2007). Serum levels of calcium and phosphate tend to be within the normal range with a GFR above 40 mL/min and tend to remain stable until the GFR is below 20 mL/min (Levin 2007).

Together, these changes may contribute to the development of a cluster of inter‐related conditions described as chronic kidney disease‐mineral and bone disorder (CKD‐MBD). This systemic disorder manifests in a number of ways. In bone, there are alterations of bone turnover, mineralization, and volume that may be accompanied by marrow fibrosis. These changes can cause altered bone growth and strength, leading to bone pain. In the cardiovascular system, excess vascular and other soft‐tissue calcification leads to occlusive arterial disease and cardiac valvular abnormalities.

Commonly measured laboratory abnormalities that accompany the development of CKD‐MBD include values of serum calcium, phosphate, vitamin D metabolites, PTH, markers of bone turnover, and FGF23. Epidemiological data have increasingly demonstrated an association between abnormal values of serum phosphate, PTH, calcium, and FGF23 caused by CKD and increased cardiovascular events and death, hospitalisation, reduced quality of life, and increased costs of care (Block 1998; Block 2004; Gutiérrez 2008; Tentori 2008).

Description of the intervention

Over the past few decades, cardiovascular disease has accounted for over half of the deaths in people receiving dialysis (USRDS 2009). The development of CKD‐MBD causing vascular calcification in the media of arterial vessels and soft tissues is recognised as a major contributing factor (Guerin 2001; Stevens 2004) to this increased death.

Several agents such as phosphate binders, vitamin D compounds, and calcimimetics are widely used to retard the development and progression of CKD‐MBD complications by acting to reduce dietary phosphate absorption and uptake, treat hyperphosphataemia and hypocalcaemia, increase low 1,25 dihydroxy‐vitamin D levels, and attenuate PTH secretion.

How the intervention might work

Several phosphate binders, including aluminium‐ and calcium‐based agents, have been widely used since 1970. Non‐calcium and non‐aluminium‐based agents, such as sevelamer hydrochloride and lanthanum carbonate, subsequently became available, and more recently, iron‐based compounds have been developed. The use of sevelamer, lanthanum, and iron‐based compounds is increasing in nephrology practice, although they incur greater cost than the older phosphate binders (St Peter 2008; St Peter 2009; USRDS 2009).

The avoidance of calcium‐based agents in CKD theoretically avoids the risks associated with positive calcium balance and the consequent acceleration of vascular calcification and cardiovascular events. For control of hyperphosphataemia, the 2003 National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiatives (NKF‐KDOQI) recommended calcium‐based binders in CKD stages 3 and 4 (glomerular filtration rate (GFR) 30 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 15 to 29 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively), and both calcium‐based and calcium‐ and aluminium‐free binders in CKD stages 5 and 5D (GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and dialysis) (K/DOQI 2003). However, more recently, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2017 update suggests that for patients with CKD G3a‐G5D, elevated phosphate levels should be lowered toward the normal range rather than normalised, while avoiding hypercalcaemia for adult patients (KDIGO 2017). The 2017 KDIGO update suggested restricting the dose of calcium‐based phosphate binders and tolerance of mild and asymptomatic hypocalcaemia, in order to avoid exogenous calcium loading. These guidelines offered a more conservative approach to the use of phosphate binders in patients with CKD G3a to G4, due to insufficient evidence that targeting normal range serum phosphate values improved clinical outcomes, and based upon the safety and side effects of the therapeutic interventions.

Why it is important to do this review

The utility of calcium‐free phosphate binders in reducing clinical events in CKD, balanced against their cost and potential harms has been controversial (Salusky 2006; St Peter 2009). The KDIGO guidelines of 2009 recommended restricting the use of calcium‐based binders in people with persistent or recurrent hypercalcaemia or arterial calcification, or both (KDIGO 2009) and that phosphate binders might be used in patients with CKD G3‐5 and on dialysis (CKD G5D) to achieve improvements in serum phosphate levels toward the normal range. However, citing new trial evidence, the KDIGO 2017 guidelines suggest that phosphate binders have an insufficient evidence base for efficacy and safety among patients with CKD G3a to G5 not on dialysis and that phosphate binders be limited to patients with "progressive or persistent" hyperphosphataemia (KDIGO 2017). The 2017 KDIGO guidelines have suggested that not all phosphate binders are interchangeable, and that excess exposure to calcium, as calcium‐based binders, may be harmful across all GFR categories, however there has remained some uncertainty about the evidence that calcium‐free agents are superior to calcium‐based agents for prevention of adverse clinical outcomes.

In addition, non‐calcium binders may increase healthcare costs. Subsidisation of non‐calcium based phosphate binders in Australia led to increased medication costs from AUD 12.85 per patient per week to AUD 59.85 per patient per week (an additional AUD 2444 per patient per years) (Gray 2011). Medicare costs for phosphate binders among dialysis patients in the US were in excess of USD 1.5 billion in 2015 (St. Peter 2018).

Current guidelines suggest the restriction of calcium‐based phosphate binders for patients treated with dialysis, and a more tolerant approach to higher phosphate levels among patients with CKD G3a to 5 not requiring dialysis, likely to lead to less phosphate binder use for these patients. Because of these factors and the emergence of new studies since the 2011 Cochrane review, we have updated the evidence to address the use of phosphate binder for patients with CKD.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess the benefits and harms of phosphate binders for people with CKD with particular reference to relevant biochemical end‐points, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular morbidity, hospitalisation, and death.

In particular we aimed to evaluate the effects of aluminium‐, calcium‐, sevelamer‐, lanthanum‐, iron‐, bixalomer‐, colestilan‐, and magnesium‐based phosphate binders, and nicotinamide, on:

Relevant biochemical end‐points: serum PTH, calcium, phosphate and FGF23

Symptoms: pruritis and bone pain

Bone structure and function: bone mineral density (BMD) assessed by dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry (DEXA) or quantitative computerised tomography (QCT), bone turnover and mineralisation based on biochemical bone turnover markers, turnover and volume based on histomorphometry, and fracture events

Clinical outcomes: cardiovascular events, number of hospital admissions, and cardiovascular and death (all causes)

Vascular calcification

Adverse events

We also aimed to identify whether treatment efficacy differed based on GFR categories (CKD G5D and CKD G2 to G5) and whether individual phosphate binders within each class had different effects.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth, or other predictable methods) of phosphate binders used for CKD (any GFR category). Studies of phosphate binders, alone or in combination with other (non‐randomised) co‐interventions (for example vitamin D compounds) were included. The first phase of randomised cross‐over studies was included, or both study phases, if appropriate statistical analyses were reported. There were no language restrictions.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults with CKD (any category) including G2 to G5 (GFR 15 to 90 mL/min) and G5D (dialysis) (KDIGO 2012).

Exclusion criteria

Studies of participants with a kidney transplant (CKD 5T) were excluded as these studies have been reviewed in a separate Cochrane review (Palmer 2007) that is currently being updated. Studies evaluating treatment in children were excluded as these have been evaluated in a separate Cochrane review (Hahn 2015).

Types of interventions

We included studies with follow‐up of at least eight weeks evaluating phosphate binders (including: sevelamer‐, lanthanum‐, calcium‐, iron‐, bixalomer‐, colestilan‐ (colestimide), magnesium‐, and aluminium‐ based binders) and nicotinamide (nicotinic acid), compared with another phosphate binder or placebo or usual care without phosphate binder.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Death (all causes)

Secondary outcomes

Cardiovascular death

Hospitalisation

Nonfatal myocardial infarction

Nonfatal stroke

Fracture (incidence of fracture at any site; vertebral compression fractures; fracture of femur, hip, and any long bones identified by radiographic studies)

Pruritus

Calciphylaxis

Adverse effects: including gastrointestinal (nausea, diarrhoea, constipation, abdominal bloating, abdominal pain), electrolyte imbalance (hyperkalaemia)

Hypercalcaemia (defined as serum calcium level > 10.2 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L) or as defined by the study investigators)

Serum phosphate (mg/dL), serum calcium (mg/dL), calcium‐by‐phosphate product (mg2/dL2), PTH (intact (iPTH), or PTH (1‐84)); alkaline phosphatase (IU/L), serum bicarbonate (mEq/L), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), fetuin‐A, and Klotho (any form)

Vascular calcification, soft tissue or valvular calcification

Bone mineral density assessed by dual energy X‐ray absorptiometry (DXA) or quantitative computed tomography (QCT) (change in bone mineral density using Z‐scores, T‐scores, or g/cm2 (DXA) or g/cm3 (QCT) at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, or radius)

Estimated GFR (eGFR); end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) (defined as eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, or commencing dialysis, or as defined by investigators).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 12 July 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources:

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may have been relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable. Studies and reviews that might have included relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts and, if necessary, the full text of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Data were extracted on the characteristics of participants, interventions, comparisons, and the outcomes listed above. Authors were contacted if data relating to death, phosphate, calcium, PTH, or calcium‐by‐phosphate product were not available or not reported in the published reports. Discrepancies between the assessments of the two data extractors were resolved by discussion with an arbitrator.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were assessed independently by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data were analysed using the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). Where continuous measurements of outcomes were used, the mean difference (MD) and its 95% CI were computed.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information (relating to serum phosphate, calcium, PTH, and death) required from the original author was requested by written correspondence and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We then quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I2 values was as follows:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We had planned to examine for publication bias using evidence of asymmetry in a funnel plot in the absence of between‐study statistical heterogeneity (Higgins 201).

Data synthesis

Risk estimates from individual studies were pooled using the inverse variance random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Sources of heterogeneity that were explored in the subgroup analyses for the primary outcome (death (all causes)) were: age (older than 60 years and 60 years or younger), CKD stage (stages 1‐4 and stage 5D), baseline serum phosphate (above or below 4.5 mg/dL (1.5 mmol/L)), study duration (above and below 12 months), and methodological quality (low risk of bias for allocation concealment and high or unclear risk of bias). We did not complete planned subgroup analyses for older versus newer agents as most binder types are well‐established. We have also not included subgroup analysis based on number of participants. We have now included subgroup analyses based on age and CKD category, which were not pre‐defined in the previous protocol for this review.

'Summary of findings' tables

The main results are presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). We present the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Death (all causes)

Cardiovascular death

Hypercalcaemia

Nausea

Vomiting

Constipation

Serum phosphate

Vascular calcification

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

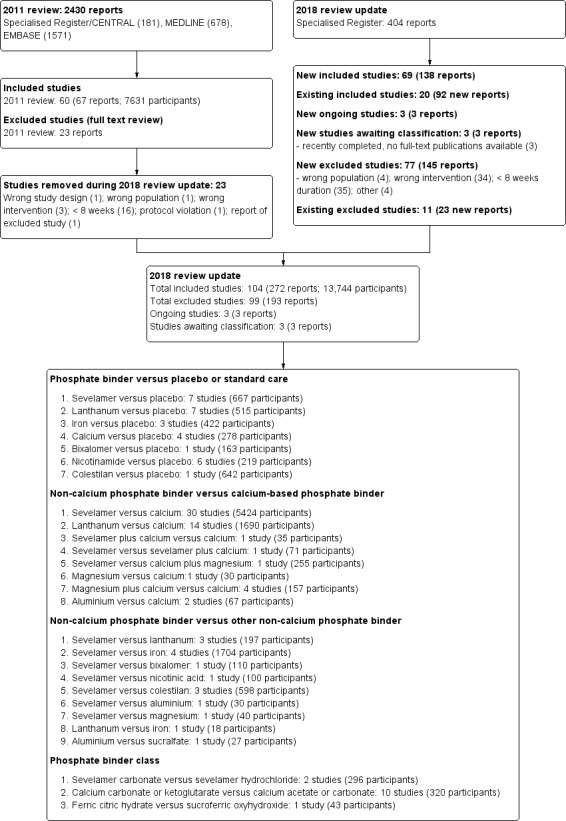

Search results are shown in Figure 1. For this 2018 review update, we identified 404 new reports. Sixty‐nine new studies in 138 reports were eligible (Characteristics of included studies). Ninety‐two additional reports of 20 studies included in the 2011 review were identified in the updated search and added to the review. Our search identified three studies that have not yet been completed (COMBINE 2014; IMPROVE‐CKD 2012; LANDMARK 2017) according to details held within the www.ClinicalTrials.gov registry. Three studies were identified as completed without published results and have been categorised as "Awaiting Classification" (NCT00317694; NCT00560300; NCT01968759). These three studies are reported as completed within www.ClinicalTrials.gov, but no results have been published or were available directly from the investigators. Twenty‐three studies in 24 reports were removed from the 2011 review during the update process as the studies did not have eight weeks follow‐up or longer (Al‐Baaj 2005; Chertow 1997; Chiang 2005; d'Almeida Filho 2000; Emmett 1991; Fan 2009; Joy 2003; Koiwa 2005a; Kurihara 2005; Finn 2004; McIntyre 2009; Pflanz 1994; Ring 1993; Schaefer 1991; Sprague 2009b; Yang 2002), included non‐randomised patients (Borrego 2000), did not evaluate an eligible intervention (Fischer 2006; FORESEE 2008; Ittel 1991; Phelps 2002), evaluated treatment in children (Salusky 1991), or were a secondary publication of an existing excluded study.

1.

Flow diagram.

This 2018 review update therefore includes 104 studies (272 reports) involving 13,744 adult participants.

Included studies

The characteristics of the participants and the interventions in included studies are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies.

Study design, setting, and characteristics

Study duration varied from 8 weeks to 36 months (median 3.7 months). Twenty studies were a cross‐over study design in which participants were administered each of the study interventions sequentially with or without a washout period.

Studies were conducted in twenty‐nine different countries or regions including Australia (SLO‐NIACIN 2013; Toussaint 2009), Belgium (Tielmans 1990), Brazil (BRiC 2005; Lemos 2013), China (Chen 2014; Song 2014; Wang 2015b; Zhao 2014), Denmark (Bro 1998; Jespersen 1991; Rudnicki 1994), Egypt (Allam 2012) multiple European countries (CALMAG 2010; Evenepoel 2009; Hutchison 2005), France (Liabeuf 2017; NICOREN 2017; PREFECT 2014; Sadek 2003), Germany (Birck 1999; Deuber 2004), Greece (Katopodis 2006; Tzanakis 2014), Iran (Shahbazian 2011), Italy (De Santo 2006; Gallieni 2005; INDEPENDENT‐CKD 2012; INDEPENDENT‐HD 2009; Riccio 2018; Russo 2007), Japan (Akizawa 2000; Akizawa 2014a; Akizawa 2016; Fujii 2017; Fujimori 2017; Itoh 2008; Kakuta 2011; Kasai 2012; Matsushima 2017; Ohtake 2013; Shibata 2007; Shigematsu 2008; Takahara 2014; Wada 2014; Yokoyama 2014; Yokoyama 2014a), Japan and Taiwan (Chen 2011b; Toida 2012), Republic of Korea (Ko 2010; Lee 2013), Macedonia (Spasovski 2006), multinational (D'Haese 2003; Floege 2014; Locatelli 2013; Locatelli 2014; NCT00542815), Pakistan (Ahmed 2014; Saif 2007), Poland (Zwiech 2011), Portugal (Ferreira 2008), Saudi Arabia (Shaheen 2004), Spain (Almirall 1994; Caravaca 1992; Foraster 1998; Hervas 2003; Navarro‐Gonzalez 2011; Soriano 2013), Taiwan (Lee 2015b; Lin 2010; Lin 2014a; Liu 2006), Thailand (Aramwit 2012), The Netherlands (Janssen 1995; Janssen 1996), Turkey (Caglar 2008; Sezer 2010), the USA (Bleyer 1999; Block 2005; Block 2009; Block 2015; CARE‐2 2008; CARE 2004; Cheng 2008; Chennasamudram 2013; Chertow 1999; DCOR 2007; Delmez 1996; Delmez 2007; Fishbane 2010; Greenberg 1994; Isakova 2013; Qunibi 2011; Roxe 1989; Seifert 2013; Spiegel 2007; Sprague 2009a; Vlassara 2012; Young 2009a), and the USA and Europe (Chertow 2002). Forty‐six studies received at least some funding from companies that manufacture phosphate binders, while 41 studies provided no specific details about funding sources.

Study participants

The 104 studies included 13,744 randomised participants. Most studies involved participants with CKD G5D ((83 studies). Of these, 73 were among participants treated with haemodialysis, two involved participants treated with haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, and eight involved participants treated with peritoneal dialysis. Twenty studies involved participants with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis. In one study, the GFR category of CKD was not reported. The sample size varied from eight participants (De Santo 2006) to 2013 participants (DCOR 2007). The median number of participants was 69. The inclusion criteria included specific serum phosphate levels in 40 studies; the requirement for a phosphate binder in 26 studies; and was not specified in the remaining 38 studies. The mean study age ranged from 42.6 years (Saif 2007) to 68.9 years (Wang 2015b), with a median of 57.2 years.

Interventions

Details of interventions in each study are presented in the Characteristics of included studies. Twenty‐eight studies compared a phosphate binder with placebo or usual care (not including phosphate binder), 49 studies compared a calcium‐free binder with a calcium‐based binder, 16 studies compared a calcium‐free binder with a second calcium‐free binder class, and 14 studies compared two different drugs within the same binder class. In 77 studies, the phosphate binder was titrated to specific levels of serum phosphate, while in 25 studies, a fixed dose of phosphate binder was used. Specific approaches to phosphate binder therapy were not reported in two studies. Most placebo or usual care controlled studies were among participants with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis (15/25 studies involving 1467 participants) while most head to head studies involved participants with CKD G5D treated with dialysis (74/81 studies involving 10,364 participants).

Phosphate binder versus placebo or usual care

Sevelamer versus placebo or usual care (677 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride or carbonate was compared with placebo or usual care in seven studies involving 667 participants (Block 2009; Chen 2014; CRIB‐PHOS 2011; Liabeuf 2017; Lemos 2013; Riccio 2018; Russo 2007). Six of the seven studies involved participants with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis. Treatment duration and follow‐up ranged between 2 and 24 months with a median of 3 months.

Lanthanum versus placebo or usual care (515 participants)

Lanthanum carbonate was compared with placebo or usual care in seven studies involving 515 participants (Block 2009; Isakova 2013; PREFECT 2014; Seifert 2013; Sprague 2009a; Takahara 2014; Wang 2015b). Six of the seven studies evaluated therapy for participants with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis. Treatment and follow‐up ranged between 3 and 12 months with a median of 3 months.

Iron versus placebo or usual care (422 participants)

An iron‐based binder (ferric citrate, previously designated as JTT‐751) was compared with placebo or usual care in three studies involving 422 participants (Block 2015; Lee 2015b; Yokoyama 2014). Two of the three studies involved adults with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis. Treatment and follow‐up ranged between 1.8 and 3 months with a median of 2.75 months.

Calcium versus placebo or usual care (278 participants)

Calcium carbonate was compared with placebo in four studies (Block 2009; Qunibi 2011; Rudnicki 1994; Russo 2007) involving 278 participants. Three of the four studies evaluated treatment in patients with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis. Treatment and follow‐up ranged between 3 and 9 months with a median of 7 months.

Bixalomer versus placebo or usual care (163 participants)

Bixalomer is a non‐calcium, metal‐free non‐absorbable polymer which has been compared with placebo for 3 months among 163 participants with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis (Akizawa 2016).

Nicotinamide versus placebo or usual care (219 participants)

Nicotinamide (also known as nicotinic acid), while not a phosphate binder, inhibits active phosphate absorption from the gut. Nicotinamide was compared with placebo or usual care in six studies involving 219 participants (Allam 2012; Aramwit 2012; Cheng 2008; Shahbazian 2011; SLO‐NIACIN 2013; Young 2009a). All studies involved participants with CKD G5D. Treatment and follow‐up ranged between 1.8 and 3.7 months with a median of 2.4 months.

Colestilan versus placebo or usual care (642 participants)

Colestilan (also known as colestimide) was compared with placebo for three months in a single study involving 642 haemodialysis patients (Locatelli 2013).

Non‐calcium phosphate binder versus calcium phosphate binder

Sevelamer versus calcium (5424 participants)

Thirty studies (5424 participants) compared sevelamer hydrochloride or sevelamer carbonate with calcium carbonate or acetate (Ahmed 2014; Akizawa 2000; Bleyer 1999; Block 2005; Block 2009; BRiC 2005; Caglar 2008; CARE‐2 2008; CARE 2004; Chennasamudram 2013; Chertow 2002; DCOR 2007; De Santo 2006; Evenepoel 2009; Ferreira 2008; Gallieni 2005; Hervas 2003; INDEPENDENT‐CKD 2012; INDEPENDENT‐HD 2009; Kakuta 2011; Lin 2010; Lin 2014a; Liu 2006; Navarro‐Gonzalez 2011; Russo 2007; Sadek 2003; Sezer 2010; Shaheen 2004; Vlassara 2012; Zhao 2014). The duration of treatment ranged between 1.8 and 24 months with a median of 5.5 months. Nearly all studies (25) involved participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis (24 studies) or peritoneal dialysis (1 study).

Lanthanum versus calcium (1690 participants)

Fourteen studies (1690 participants) compared lanthanum carbonate with calcium carbonate or acetate (Block 2009; D'Haese 2003; Fujii 2017; Hutchison 2005; Ko 2010; Lee 2013; Ohtake 2013; Shigematsu 2008; Song 2014; Soriano 2013; Spasovski 2006; Toida 2012; Toussaint 2009; Wada 2014). The duration of treatment ranged between 1.8 and 18 months with a median of 6 months. All but three studies involved participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis (9 studies) or peritoneal dialysis (3 studies).

Sevelamer plus calcium versus calcium (35 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride plus calcium carbonate was compared with calcium carbonate for 36 months in 35 patients with CKD G5D treatment with haemodialysis (Shibata 2007).

Sevelamer versus calcium plus magnesium (255 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride was compared with calcium acetate plus magnesium carbonate for six months in 255 participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis (CALMAG 2010).

Sevelamer versus sevelamer plus calcium (71 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride was compared with sevelamer hydrochloride plus calcium for 2.8 months in one study of 71 patients with CKD 5D treated with haemodialysis (Chertow 1999).

Magnesium versus calcium (30 participants)

Spiegel 2007 evaluated magnesium carbonate versus calcium carbonate treatment for 2.8 months among 30 dialysis patients.

Magnesium plus calcium versus magnesium (157 participants)

Combined magnesium and calcium therapy was compared with calcium alone in four studies (157 participants) (Deuber 2004; Evsanaa 2015; Spiegel 2007; Tzanakis 2014). All studies involved participants with CKD 5D treated with long‐term haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Follow‐up ranged from three months to 30 months, with a median of 7.5 months.

Aluminium versus calcium (67 participants)

Aluminium hydroxide was compared with calcium carbonate or acetate over 6 to 12 months among 67 haemodialysis patients (Janssen 1996; Jespersen 1991).

Non‐calcium phosphate binder versus non‐calcium phosphate binder

Sevelamer versus lanthanum (197 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride or carbonate was compared with lanthanum carbonate in three studies (Block 2009; Kasai 2012; Pratt 2007) involving 197 participants. Two of the three studies involved participants with CKD 5D treated with haemodialysis. Follow‐up ranged from 2 months to 12 months.

Sevelamer versus iron (1704 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride or carbonate was compared with iron‐based binders (SBR759 (iron (III) starch/saccharose complex); sucroferric oxyhydroxide; ferric citrate) in four studies involving 1704 participants (Chen 2011b; Floege 2014; Koiwa 2017; Yokoyama 2014a). Three of the four studies involved participants with CKD G5D. Follow‐up ranged between 3 and 6 months, with a median of 3 months.

Sevelamer versus bixalomer (110 participants)

Akizawa 2014a evaluated sevelamer hydrochloride versus bixalomer over three months in 110 participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis.

Sevelamer versus nicotinamide (100 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride was compared with nicotinamide for six months in one study (NICOREN 2017) involving 100 participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis.

Sevelamer versus colestilan (598 participants)

Sevelamer was compared with colestilan in three studies involving 598 participants (Itoh 2008; Locatelli 2014; NCT00542815). All participants had CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Treatment and follow‐up continued for 1.9 to 12 months.

Sevelamer versus aluminium (30 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride was compared with aluminium hydroxide during treatment over 16 months in 30 participants with CKD G5D treated with peritoneal dialysis (Katopodis 2006).

Sevelamer versus magnesium (40 participants)

Zwiech 2011 compared sevelamer hydrochloride with magnesium carbonate during treatment of 3 months in 40 participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis.

Lanthanum versus iron (18 participants)

Fujimori 2017 evaluated lanthanum carbonate versus ferric citrate for 3 months in 18 participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis.

Aluminium versus sucralfate (27 participants)

Aluminium hydroxide was compared with sucralfate (not used in current clinical care) for 1.8 months in 27 participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis (Roxe 1989).

Phosphate binder class

Sevelamer hydrochloride versus sevelamer carbonate (296 participants)

Sevelamer hydrochloride was compared with sevelamer carbonate in two studies involving 296 participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis (Delmez 2007; Fishbane 2010). Treatment and follow‐up was for 5.5 and 12 months, respectively.

Calcium‐based binder versus calcium‐based binder (320 participants)

Calcium carbonate was compared with calcium acetate in eight studies (209 participants) (Almirall 1994; Caravaca 1992; Foraster 1998; Greenberg 1994; Janssen 1995; Janssen 1996; Tielmans 1990). Calcium ketoglutarate was compared with calcium acetate or carbonate in two studies involving 47 participants (Birck 1999; Bro 1998). All studies involved participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis. Treatment and follow‐up ranged between 2 and 12 months with a median of 3 months.

Ferric citrate versus sucroferric oxyhydroxide (43 participants)

Ferric citrate was compared with sucroferric oxyhydroxide during three months of treatment among 43 participants with CKD G5D treated with haemodialysis (Matsushima 2017).

Excluded studies

In total, we excluded 99 studies (in 193 reports) as studies were not RCTs, were studies involving children, did not evaluate two different phosphate binders, or had follow‐up of less than eight weeks (Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias for studies overall are summarised in Figure 2 and the risk of bias in each individual study is reported in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Methods for generating the random sequence were deemed to be at low risk of bias in 25 studies (Block 2005; Block 2009; Block 2015; BRiC 2005; CARE‐2 2008; Chertow 2002; Floege 2014; Liabeuf 2017; Greenberg 1994; INDEPENDENT‐CKD 2012; Katopodis 2006; Koiwa 2017; Lemos 2013; Locatelli 2013; Locatelli 2014; Navarro‐Gonzalez 2011; Ohtake 2013; Riccio 2018; Rudnicki 1994; Seifert 2013; SLO‐NIACIN 2013; Song 2014; Toida 2012; Toussaint 2009; Tzanakis 2014). The sequence did not appear to be random in one study, in which treatment group may have been based on serum phosphate levels (Fujii 2017). In the remaining 78 studies, the method for generating the random sequence was unclear.

Allocation concealment was adjudicated as low risk of bias in 15 studies (Block 2005; Block 2009; Block 2015; BRiC 2005; Floege 2014; Liabeuf 2017; Greenberg 1994; INDEPENDENT‐CKD 2012; Kakuta 2011; Koiwa 2017; NICOREN 2017; PREFECT 2014; Riccio 2018; Riccio 2018; Russo 2007; Toussaint 2009). The method to conceal allocation was deemed to be high risk in one study in which some participants could choose their treatment group (Tzanakis 2014). The risk of bias for allocation concealment was unclear in the remaining 88 studies.

Blinding

Twenty‐seven studies were blinded and considered to be at low risk of bias for performance bias (Akizawa 2016; Block 2009; Block 2015; CARE 2004; Chen 2014; Cheng 2008; CRIB‐PHOS 2011; Evsanaa 2015; Liabeuf 2017; Isakova 2013; Lee 2015b; Locatelli 2013; PREFECT 2014; Qunibi 2011; Riccio 2018; Rudnicki 1994; Seifert 2013; Shahbazian 2011; Shigematsu 2008; SLO‐NIACIN 2013; Sprague 2009a; Takahara 2014; Tielmans 1990; Toussaint 2009; Tzanakis 2014; Yokoyama 2014; Young 2009a). Blinding was unclear in four studies (Almirall 1994; Aramwit 2012; Matsushima 2017; Sezer 2010). The remaining 73 studies were not blinded and were considered at high risk of performance bias.

As most studies were based on laboratory assessment or patient‐centred outcomes including death, all studies were considered at low risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data

Thirty‐one studies met criteria for low risk of attrition bias (Almirall 1994; Aramwit 2012; Bleyer 1999; Block 2015; Caglar 2008; Chen 2011b; Chen 2014; Cheng 2008; CRIB‐PHOS 2011; Delmez 2007; Evsanaa 2015; Hervas 2003; INDEPENDENT‐HD 2009; Isakova 2013; Kasai 2012; Liu 2006; Navarro‐Gonzalez 2011; Riccio 2018; Rudnicki 1994; Russo 2007; Sezer 2010; Shahbazian 2011; Shaheen 2004; Shigematsu 2008; SLO‐NIACIN 2013; Spasovski 2006; Tzanakis 2014; Wada 2014; Wang 2015b; Young 2009a; Zhao 2014). Fifty‐two studies were considered at high risk of attrition bias when there was differential loss to follow‐up between treatment groups, high attrition rates (> 10%), or when adverse events were substantially higher in one or both treatment groups (Akizawa 2014a; Akizawa 2016; Allam 2012; Birck 1999; Block 2005; Block 2009; BRiC 2005; Bro 1998; CALMAG 2010; Caravaca 1992; CARE 2004; CARE‐2 2008; D'Haese 2003; DCOR 2007; Evenepoel 2009; Ferreira 2008; Fishbane 2010; Floege 2014; Fujimori 2017; Hutchison 2005; INDEPENDENT‐CKD 2012; Itoh 2008; Janssen 1995; Janssen 1996; Jespersen 1991; Kakuta 2011; Koiwa 2017; Lee 2013; Lee 2015b; Lemos 2013; Liabeuf 2017; Lin 2010; Lin 2014a; Locatelli 2013; Locatelli 2014; NCT00542815; NICOREN 2017; Ohtake 2013; PREFECT 2014; Qunibi 2011; Roxe 1989; Sadek 2003; Saif 2007; Seifert 2013; Seifert 2013; Sprague 2009a; Takahara 2014; Toida 2012; Toussaint 2009; Vlassara 2012; Yokoyama 2014; Yokoyama 2014a). In the remaining 21 studies, attrition bias was considered unclear. Loss to follow‐up was commonly due to death, transplantation, withdrawal of consent, protocol violation, or adverse events.

Selective reporting

Sixty‐nine studies reported expected and clinically‐relevant outcomes and were deemed to be at low risk of bias (Akizawa 2000; Akizawa 2014a; Akizawa 2016; Allam 2012; Aramwit 2012; Bleyer 1999; Block 2005; Block 2009; Block 2015; BRiC 2005; Bro 1998; CALMAG 2010; CARE‐2 2008; CARE 2004; Chen 2011b; Chen 2014; CRIB‐PHOS 2011; DCOR 2007; Delmez 2007; Evenepoel 2009; Fishbane 2010; Floege 2014; Gallieni 2005; Hutchison 2005; INDEPENDENT‐CKD 2012; INDEPENDENT‐HD 2009; Isakova 2013; Janssen 1995; Janssen 1996; Kakuta 2011; Kasai 2012; Katopodis 2006; Ko 2010; Koiwa 2017; Lee 2013; Lee 2015b; Lemos 2013; Liabeuf 2017; Lin 2010; Lin 2014a; Liu 2006; Locatelli 2013; Locatelli 2014; Matsushima 2017; NCT00542815; NICOREN 2017; Ohtake 2013; Pratt 2007; PREFECT 2014; Qunibi 2011; Riccio 2018; Sadek 2003; Seifert 2013; Sezer 2010; Shahbazian 2011; Shigematsu 2008; SLO‐NIACIN 2013; Spasovski 2006; Sprague 2009a; Takahara 2014; Tielmans 1990; Toida 2012; Toussaint 2009; Tzanakis 2014; Vlassara 2012; Wada 2014; Yokoyama 2014; Yokoyama 2014a; Zhao 2014). The remaining 35 studies did not report patient‐centred outcomes of death or adverse events.

Other potential sources of bias

Forty studies appeared to be free from other sources of bias (Allam 2012; Block 2005; Block 2009; Block 2015; BRiC 2005; Caglar 2008; CALMAG 2010; Caravaca 1992; CARE‐2 2008; Chertow 1999; Chertow 2002; CRIB‐PHOS 2011; Deuber 2004; Floege 2014; Hutchison 2005; INDEPENDENT‐CKD 2012; INDEPENDENT‐HD 2009; Isakova 2013; Itoh 2008; Kakuta 2011; Lemos 2013; Liabeuf 2017; Lin 2010; Locatelli 2013; Locatelli 2014; Riccio 2018; Russo 2007; Seifert 2013; Shahbazian 2011; Song 2014; Soriano 2013; Spiegel 2007; Toida 2012; Toussaint 2009; Tzanakis 2014; Vlassara 2012; Wada 2014; Wang 2015b; Yokoyama 2014a; Zhao 2014). Forty‐three studies had other sources of bias (Ahmed 2014; Akizawa 2014a; Akizawa 2016; Almirall 1994; Aramwit 2012; Birck 1999; Bleyer 1999; Bro 1998; CARE 2004; Chen 2011b; Chen 2014; Cheng 2008; Chennasamudram 2013; DCOR 2007; Delmez 1996; Delmez 2007; De Santo 2006; Evenepoel 2009; Evsanaa 2015; Ferreira 2008; Fishbane 2010; Greenberg 1994; Hervas 2003; Jespersen 1991; Ko 2010; Koiwa 2017; Lin 2014a; Liu 2006; Navarro‐Gonzalez 2011; NICOREN 2017; Ohtake 2013; PREFECT 2014; Qunibi 2011; Roxe 1989; Rudnicki 1994; Sadek 2003; Shaheen 2004; Shigematsu 2008; SLO‐NIACIN 2013; Spasovski 2006; Sprague 2009a; Takahara 2014; Young 2009a). It was unclear whether the remaining 21 studies had other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: Sevelamer versus placebo/usual care.

| Sevelamer versus placebo or usual care for preventing and treating bone disease in people chronic kidney disease (CKD) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD Setting: most studies involved people with CKD not requiring dialysis Intervention: sevelamer versus placebo or usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Sevelamer | |||||

| Death (all causes) Follow‐up: 3 to 24 months (median 10 months) |

Low risk population |

RR 2.16 (0.20 to 22.8) |

248 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5 | A single study reported 1 or more events. The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low | |

| 8 per 1000 |

17 per 1000 (2 to 183) |

|||||

| Cardiovascular death | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

|

Hypercalcaemia Follow‐up: 9 months |

18 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 | RR 1.90 (0.12 to 29.32) | 42 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6 | A single study reported 1 event in each group |

|

Nausea Follow‐up: 2 to 9 months (median 3 months) |

30 per 1000 |

38 per 1000 (2 to 673) |

RR 1.27 (0.07 to 22.42) |

370 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Vomiting Follow‐up: 2.8 to 9 months |

10 per 1000 |

22 per 1000 (3 to 173) |

RR 2.09 (0.26 to 16.57) |

165 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 2 to 9 months (median 3 months) |

10 per 1000 |

71 per 1000 (23 to 218) |

RR 6.92 (2.24 to 21.38) |

430 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Serum phosphate level Follow‐up: 2 to 10 months (median 3 months) |

The mean serum phosphate level in the placebo group was 4.48 mg/dL | The mean serum phosphate level in the sevelamer group was 0.28 mg/dL lower (0.39 higher to 0.94 lower) | ‐‐ | 483 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Coronary artery calcification score Follow‐up: 24 months (both studies) |

The mean coronary artery calcium score in the placebo group was 945 | The mean coronary artery calcium score in the sevelamer group was 70 lower (362 lower to 222 higher) |

‐‐ | 115 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

The assumed risk is the event rate per annum in the control arm of included studies

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Most studies had unclear risks for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were not blinded (participants or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to moderate or substantial between‐study heterogeneity

3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision

4 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to publication bias

5 Evidence certainty was downgraded by two levels due to severe imprecision

6 Data came from only one study

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: Lanthanum versus placebo/usual care.

| Lanthanum versus placebo or usual care for preventing and treating bone disease in people chronic kidney disease (CKD) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD Setting: most studies involved people with CKD not requiring dialysis Intervention: lanthanum versus placebo or usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or standard care | Lanthanum | |||||

| Death (all causes) Follow‐up: 1.8 to 12 months (median 3 months) |

Low risk population |

RR 1.63 (0.07 to 37.12) |

214 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5,6 | A single death was reported among three studies. The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Cardiovascular death | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

|

Nausea Follow‐up: 1.8 to 12 months (median 2 months) |

23 per 1000 |

87 per 1000 (32 to 237) |

RR 3.72 (1.36 to 10.18) |

383 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Vomiting Follow‐up: 1.8 to 9 months (median 3 months) |

32 per 1000 |

89 per 1000 (13 to 601) |

RR 2.76 (0.41 to 18.63) |

261 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 1.8 to 9 months (median 3 months) |

35 per 1000 |

104 per 1000 (42 to 255) |

RR 2.98 (1.21 to 7.30) |

299 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Serum phosphate level Follow‐up: 1.8 to 12 months (median 3 months) |

The mean serum phosphate level in the placebo group was 4.7 mg/dL | The mean serum phosphate level in the lanthanum group was 0.48 mg/dL lower (0.05 to 0.90 lower) |

‐‐ | 171 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Coronary artery calcification score Follow‐up: 12 months |

The mean coronary artery calcification score in the placebo group was 23 mm3 | The mean coronary artery calcification score in the lanthanum group was3 mm3 higher (9.86 lower to 15.86 higher) | ‐‐ | 38 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6 | A single study reported this outcome |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

The assumed risk is the event rate per annum in the control arm of included studies

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Most studies had unclear risks for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were not blinded (participants or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to moderate or substantial between‐study heterogeneity

3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision

4 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to publication bias

5 Evidence certainty was downgraded by two levels due to severe imprecision

6 Data came from only one study

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings: Iron versus placebo/usual care.

| Iron versus placebo or usual care for preventing and treating bone disease in people chronic kidney disease (CKD) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD Setting: dialysis (1 study) and CKD (2 studies) Intervention: iron versus placebo or usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or standard care | Iron | |||||

| Death (all causes) Follow‐up: 2.75 to 3 months |

19 per 1000 |

10 per 1000 (1 to 89) |

RR 0.52 (0.06 to 4.65) |

239 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

| Cardiovascular death | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

| Hypercalcaemia | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

| Nausea | 68 per 1000 |

67 per 1000 (20 to 221) |

RR 0.99 (0.30 to 3.27) | 149 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6 | A single study reported this outcome |

| Vomiting | No data observations | Not estimable | Not estimable | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 1.8 to 3 months (median 2.75 months) |

43 per 1000 |

114 per 1000 (49 to 262) |

RR 2.66 (1.15 to 6.12) |

422 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Serum phosphate level Follow‐up: 1.8 to 3 months (median 2.75 months) |

The mean serum phosphate level in the placebo group was 5.8 mg/dL | The mean serum phosphate in the iron group was 1.33 mg/dL lower (0.41 to 2.25 lower) |

‐‐ | 422 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

| Coronary artery calcification score | No data observations | Not estimable | Not estimable | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

The assumed risk is the event rate per annum in the control arm of included studies

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Most studies had unclear risks for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were not blinded (participants or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to moderate or substantial between‐study heterogeneity

3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision

4 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to publication bias

5 Evidence certainty was downgraded by two levels due to severe imprecision

6 Data came from only one study

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings: Calcium versus placebo/usual care.

| Calcium versus placebo or usual care for preventing and treating bone disease in people chronic kidney disease (CKD) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD Setting: Most studies involved people with CKD not requiring dialysis Intervention: calcium versus placebo or usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Calcium | |||||

| Death (all causes) | 47 per 1000 |

22 per 1000 (2 to 203) |

RR 0.46 (0.05 to 4.32) |

110 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6 | A single study reported this outcome |

| Cardiovascular death | No data observations | Not estimable | Not estimable | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

|

Hypercalcaemia Follow‐up: 3 to 9 months |

8 per 1000 |

56 per 1000 (13 to 248) |

RR 7.28 (1.64 to 32.2) |

215 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Nausea Follow‐up: 3 to 9 months |

66 per 1000 |

38 per 1000 (10 to 144) |

RR 0.58 (0.15 to 2.18) |

197 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

| Vomiting | No data observations | Not estimable | Not estimable | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 3 to 9 months |

66 per 1000 |

161 per 1000 Not estimable |

RR 2.44 (0.32 to 18.4) |

197 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

|

Serum phosphate level Follow‐up: 5.5 to 24 months (median 9 months) |

The mean serum phosphate level in the placebo group was 5.0 mg/dL | The mean serum phosphate level in the calcium group was 0.18 mg/dL lower (0.95 higher to 1.30 lower) | ‐‐ | 151 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

The studies were predominantly in CKD G2 to G5. Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients treated with dialysis (GFR 5D) is very low |

| Coronary artery calcification score | The mean coronary artery calcification score in the placebo group was 473 | The mean coronary artery calcification score in the calcium group was 74 lower (443 lower to 295 higher) | ‐‐ | 60 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6 | A single study reported this outcome |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

The assumed risk is the event rate per annum in the control arm of included studies

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Most studies had unclear risks for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were not blinded (participants or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to moderate or substantial between‐study heterogeneity

3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision

4 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to publication bias

5 Evidence certainty was downgraded by two levels due to severe imprecision

6 Data came from only one study

Summary of findings 5. Summary of findings: Sevelamer versus calcium.

| Sevelamer versus calcium for preventing and treating bone disease people with in chronic kidney disease (CKD) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD Setting: most studies involved people treated with dialysis Intervention: sevelamer versus calcium | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Calcium | Sevelamer | |||||

|

Death (all causes) Follow‐up: 1.8 to 36 months (median 5.5 months) |

Low risk population (CKD G2 to G5) |

RR 0.53 (0.30 to 0.91) |

3688 (16) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low | |

| 124 per 1000 |

79 per 1000 (27 to 227) |

|||||

| High risk population (CKD G5D) | ||||||

| 210 per 1000 |

105 per 1000 (55 to 199) |

|||||

|

Cardiovascular death Follow‐up: 3 to 36 months (median 12 months) |

Low risk population (CKD G2 to G5) |

RR 0.45 (0.11 to 1.77) |

2829 (6) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low | |

| 92 per 1000 |

34 per 1000 (1 to 1000) |

|||||

| High risk population (CKD G5D) | ||||||

| 132 per 1000 |

112 per 1000 (11 to 177) |

|||||

|

Hypercalcaemia Follow‐up: 1.8 to 36 months (median 5.5 months) |

139 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (28 to 60) |

RR 0.30 (0.20 to 0.43) |

4084 (19) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Nausea Follow‐up: 2 to 12 months (median 9 months) |

125 per 1000 | 123 per 1000 (70 to 214) |

RR 0.98 (0.56 to 1.71) |

365 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Vomiting Follow‐up: 9 to 12 months |

158 per 1000 |

150 per 1000 (85 to 267) |

RR 0.95 (0.54 to 1.69) |

263 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 2 to 20 months (median 12 months) |

13 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (9 to 33) |

RR 1.35 (0.71 to 2.57) |

2652 (6) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Serum phosphate level Follow‐up: 1.8 to 36 months (median 5.5 months) |

The mean serum phosphate level in the calcium group was 5.39 mg/dL | The mean serum phosphate level in the sevelamer group was

0.06 mg/dL higher (0.11 lower to 0.23 higher) |

‐‐ | 4360 (23) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Coronary artery calcium score Follow‐up: 12‐24 months (median 12 months) |

The mean coronary artery calcium score in the calcium group was 923 | The mean coronary artery calcium score in the sevelamer group was 25 lower (76 lower to 26 higher) |

‐‐ | 517 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

The assumed risk is the median incidence of the event in the control arm of included studies. Where there was a wide range of reported incidence (for example, Death (all causes) ranged from 10 per 1000 to 340 per 1000), two levels of risk (high and low) were generated for calculation of absolute risks

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Most studies had unclear risks for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were not blinded (participants or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to moderate or substantial between‐study heterogeneity

3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision

4 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to publication bias

Summary of findings 6. Summary of findings ‐ Lanthanum versus calcium.

| Lanthanum versus calcium for preventing and treating bone disease people with in chronic kidney disease (CKD) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with CKD Setting: most studies involved people treated with dialysis Intervention: lanthanum versus calcium | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Calcium | Lanthanum | |||||

| Death (all causes) Follow‐up: 1.8 to 18 months (median 6 months) |

High risk population (CKD G5D) |

RR 0.76 (0.18 to 3.11) |

505 (6) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | The studies were in CKD G5D | |

| 15 per 1000 |

12 per 1000 (3 to 48) |

|||||

| Cardiovascular death | No data observations | Not estimable | No studies | No studies | Not estimable | ‐‐ |

|

Hypercalcaemia Follow‐up: 1.8 to 12 months (median 6 months) |

240 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (14 to 103) |

RR 0.16 (0.06 to 0.43) |

1347 (8) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Nausea Follow‐up: 1.8 to 12 months (median 6 months) |

88 per 1000 | 145 per 1000 (84 to 254) |

RR 1.65 (0.95 to 2.89) |

1191 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Vomiting Follow‐up: 1.8 to 6 months |

78 per 1000 |

301 per 1000 (37 to 1000) |

RR 3.88 (0.48 to 31.7) |

1058 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,5 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 1.8 to 18 months (median 6 months) |

67 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (33 to 84) |

RR 0.79 (0.50 to 1.26) |

1213 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Serum phosphate level Follow‐up: 3 to 12 months (median 6 months) |

The mean serum phosphate level in the calcium group was 5.39 mg/dL | The mean serum phosphate level in the lanthanum group was 0.01 mg/dL lower (0.42 higher to 0.43 lower) | ‐‐ | 400 (9) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | It was not possible to assess for publication bias due to substantial between‐study heterogeneity. The studies were predominantly in CKD G5D Therefore, the evidence certainty for patients with CKD G2 to G5 is very low |

|

Coronary artery calcium score Follow‐up: 6 months |

The mean coronary artery calcium score in the calcium group was 1640 | The mean coronary artery calcium score in the lanthanum group was 57 lower (1308 lower to 5 higher) | ‐‐ | 42 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6 | A single study reported 1 or more events |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

The assumed risk is the event rate per annum in the control arm of the control arm of included studies. Where there was a wide range of reported incidence (for example, Death (all causes) ranged from 10 per 1000 to 340 per 1000), two levels of risk (high and low) were generated for calculation of absolute risks.

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Most studies had unclear risks for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were not blinded (participants or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to moderate or substantial between‐study heterogeneity

3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision

4 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to publication bias

5 Evidence certainty was downgraded by two levels due to severe imprecision

6 Data came from only one study

Sevelamer versus placebo or usual care

The major outcomes for the comparison of sevelamer with placebo or usual care are shown in the Table 1. Evidence was generally restricted to people with CKD G2 to G5 not requiring dialysis.