Abstract

Background

As part of efforts to prevent childhood overweight and obesity, we need to understand the relationship between total fat intake and body fatness in generally healthy children.

Objectives

To assess the effects and associations of total fat intake on measures of weight and body fatness in children and young people not aiming to lose weight.

Search methods

For this update we revised the previous search strategy and ran it over all years in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (Ovid), MEDLINE (PubMed), and Embase (Ovid) (current to 23 May 2017). No language and publication status limits were applied. We searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov for ongoing and unpublished studies (5 June 2017).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in children aged 24 months to 18 years, with or without risk factors for cardiovascular disease, randomised to a lower fat (30% or less of total energy (TE)) versus usual or moderate‐fat diet (greater than 30%TE), without the intention to reduce weight, and assessed a measure of weight or body fatness after at least six months. We included prospective cohort studies if they related baseline total fat intake to weight or body fatness at least 12 months later.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data on participants, interventions or exposures, controls and outcomes, and trial or cohort quality characteristics, as well as data on potential effect modifiers, and assessed risk of bias for all included studies. We extracted body weight and blood lipid levels outcomes at six months, six to 12 months, one to two years, two to five years and more than five years for RCTs; and for cohort studies, at baseline to one year, one to two years, two to five years, five to 10 years and more than 10 years. We planned to perform random‐effects meta‐analyses with relevant subgrouping, and sensitivity and funnel plot analyses where data allowed.

Main results

We included 24 studies comprising three parallel‐group RCTs (n = 1054 randomised) and 21 prospective analytical cohort studies (about 25,059 children completed). Twenty‐three studies were conducted in high‐income countries. No meta‐analyses were possible, since only one RCT reported the same outcome at each time point range for all outcomes, and cohort studies were too heterogeneous to combine.

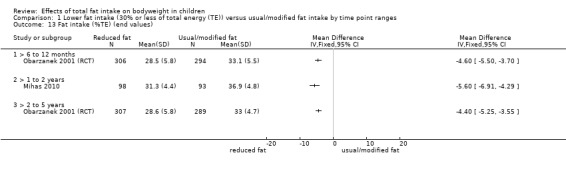

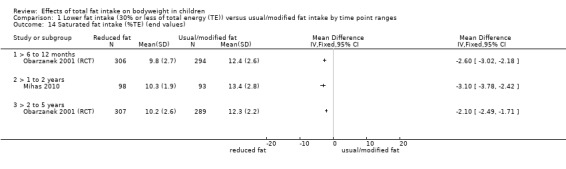

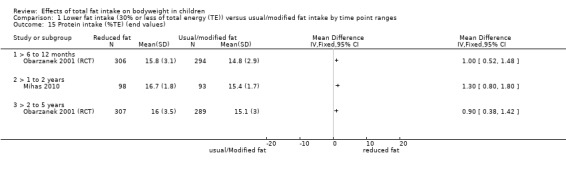

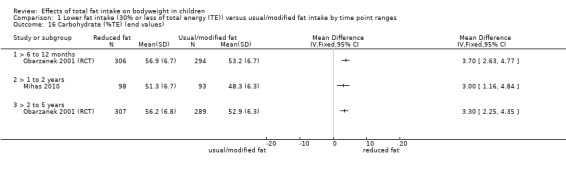

Effects of dietary counselling to reduce total fat intake from RCTs

Two studies recruited children aged between 4 and 11 years and a third recruited children aged 12 to 13 years. Interventions were combinations of individual and group counselling, and education sessions in clinics, schools and homes, delivered by dieticians, nutritionists, behaviourists or trained, supervised teachers. Concerns about imprecision and poor reporting limited our confidence in our findings. In addition, the inclusion of hypercholesteraemic children in two trials raised concerns about applicability.

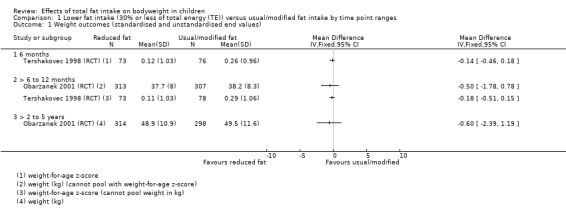

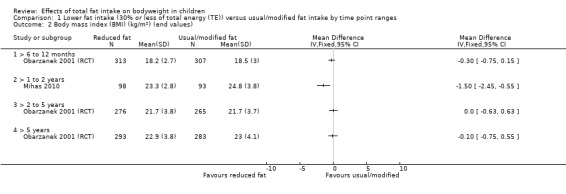

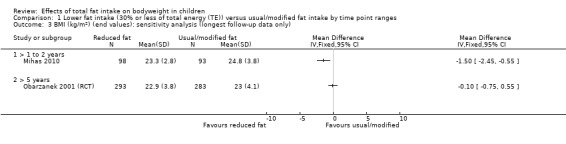

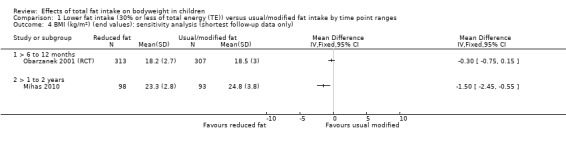

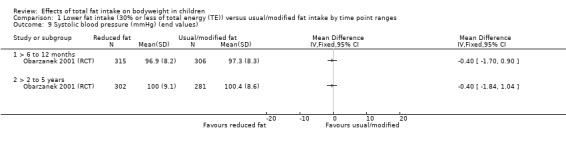

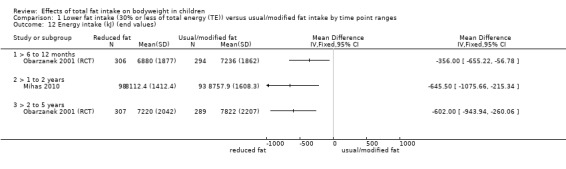

One study of dietary counselling to lower total fat intake found that the intervention may make little or no difference to weight compared with usual diet at 12 months (mean difference (MD) ‐0.50 kg, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.78 to 0.78; n = 620; low‐quality evidence) and at three years (MD ‐0.60 kg, 95% CI ‐2.39 to 1.19; n = 612; low‐quality evidence). Education delivered as a classroom curriculum probably decreased BMI in children at 17 months (MD ‐1.5 kg/m2, 95% CI ‐2.45 to ‐0.55; 1 RCT; n = 191; moderate‐quality evidence). The effects were smaller at longer term follow‐up (five years: MD 0 kg/m2, 95% CI ‐0.63 to 0.63; n = 541; seven years; MD ‐0.10 kg/m2, 95% CI ‐0.75 to 0.55; n = 576; low‐quality evidence).

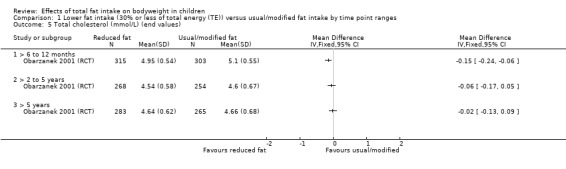

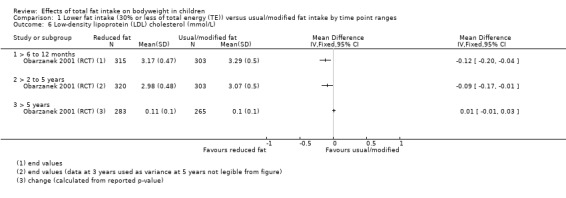

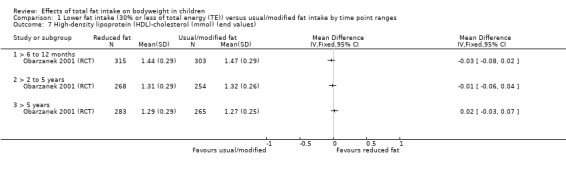

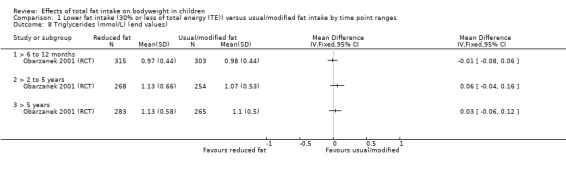

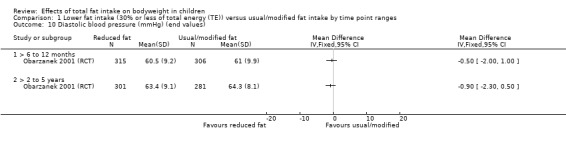

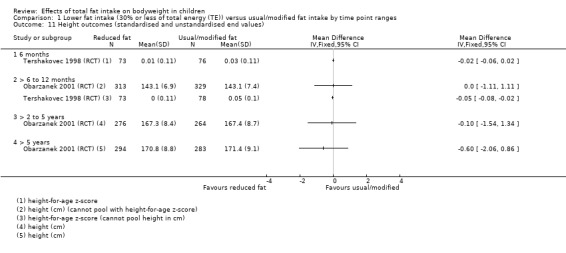

Dietary counselling probably slightly reduced total cholesterol at 12 months compared to controls (MD ‐0.15 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.24 to ‐0.06; 1 RCT; n = 618; moderate‐quality evidence), but may make little or no difference over longer time periods. Dietary counselling probably slightly decreased low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol at 12 months (MD ‐0.12 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.04; 1 RCT; n = 618, moderate‐quality evidence) and at five years (MD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.01; 1 RCT; n = 623; moderate‐quality evidence), compared to controls. Dietary counselling probably made little or no difference to HDL‐C at 12 months (MD ‐0.03 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.02; 1 RCT; n = 618; moderate‐quality evidence), and at five years (MD ‐0.01 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.04; 1 RCT; n = 522; moderate‐quality evidence). Likewise, counselling probably made little or no difference to triglycerides in children at 12 months (MD ‐0.01 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.06; 1 RCT; n = 618; moderate‐quality evidence). Lower versus usual or modified fat intake may make little or no difference to height at seven years (MD ‐0.60 cm, 95% CI ‐2.06 to 0.86; 1 RCT; n = 577; low‐quality evidence).

Associations between total fat intake, weight and body fatness from cohort studies

Over half the cohort analyses that reported on primary outcomes suggested that as total fat intake increases, body fatness measures may move in the same direction. However, heterogeneous methods and reporting across cohort studies, and predominantly very low‐quality evidence, made it difficult to draw firm conclusions and true relationships may be substantially different.

Authors' conclusions

We were unable to reach firm conclusions. Limited evidence from three trials that randomised children to dietary counselling or education to lower total fat intake (30% or less TE) versus usual or modified fat intake, but with no intention to reduce weight, showed small reductions in body mass index, total‐ and LDL‐cholesterol at some time points with lower fat intake compared to controls. There were no consistent effects on weight, high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol or height. Associations in cohort studies that related total fat intake to later measures of body fatness in children were inconsistent and the quality of this evidence was mostly very low. Most studies were conducted in high‐income countries, and may not be applicable in low‐ and middle‐income settings. High‐quality, longer‐term studies are needed, that include low‐ and middle‐income settings to look at both possible benefits and harms.

Plain language summary

Effect of cutting down the amount of fat on bodyweight in children

Review question

What is the relationship between the amount of fat a child eats and their weight and body fat?

Background

To try to better prevent people from being overweight and obese, we need to understand what the ideal amount of total fat in our diets should be, and particularly how this is related to bodyweight and fatness. This relationship differs in children compared to adults, because children are still growing and developing.

Study characteristics

This review looked at the effects of eating less fat on bodyweight and fatness in healthy children aged between two and 18 years, who were not aiming to lose weight. We carried out a comprehensive search for studies up to May 2017.

Key results

We found three randomised controlled trials (clinical trials where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) conducted in 1054 children in high‐income (wealthy) countries. Two studies recruited children aged between 4 and 11 years and one study recruited children aged 12 to 13 years. The studies looked at different types of interventions, including individual and group educational sessions or advice. The sessions were delivered in clinics, schools and homes by dieticians, nutritionists or teachers. The interventions used in the studies were intended to help children to eat less total fat in their diet (30% or less of their total daily energy). These interventions were compared with a usual or modified fat intake (more than 30% of their total daily energy) for between one and seven years. Some of these results showed that a lower fat intake may reduce body mass index (BMI; a measure of body fatness based on height and weight) and the blood levels of different types of cholesterol (a fat carried in the blood) when compared to a higher fat intake. However, these effects varied over time with some results showing that a lower fat intake may make little or no difference. Evidence from one trial suggested that lower fat intake probably had no effect on blood levels of one type of cholesterol (called HDL‐cholesterol) and may have no effect on height compared to higher fat intakes. This evidence cannot necessarily be applied to all healthy children, as two studies were done in children with raised blood cholesterol levels.

We also looked at 21 studies in approximately 25,059 children that observed and measured the children's intake of fat and their weight, BMI, and other body measures over time, but did not seek to directly change what they ate (these are called cohort studies). Over half of these cohort studies that reported on body fatness suggested that as total fat intake increases, body fatness may move in the same direction. However, results varied across all these studies and we could not draw any firm conclusions.

Quality of the evidence

We found no high‐quality evidence with which to answer this question. Evidence from the cohort studies was generally of very low quality so we are uncertain about these results and cannot draw conclusions. For the three randomised controlled trials, the results that we were most interested in were generally of moderate‐ or low‐quality evidence. We could not make any conclusions about children in low‐ and middle‐income countries as 23 of the 24 studies were done in high‐income countries. More high‐quality, long‐term studies are required that also include children from low‐ and middle‐income settings.

Summary of findings

Background

Description and implications of the condition

Childhood obesity is an important global public health problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines childhood obesity as the proportion of children with weight‐for‐height z‐score (WHZ) values greater than three standard deviations (SDs) from the WHO growth standard median (de Onis 2007), with slightly different standards being reported by other organisations such as the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) (Cole 2000). Overweight and obesity levels among infants, children and adolescents are rising globally. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity in children increased by 47.1% between 1980 and 2013 (Ng 2014). Overweight and obesity affects disadvantaged population groups more, and rising levels are being seen particularly in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), largely due to the rapid nutrition transition (de Onis 2010; GBD 2017a; WHO 2016). Of all children under five years of age who were overweight in 2016, 49% lived in Asia and 24% in Africa (UNICEF 2017).

Obesity has physical and psychosocial health consequences during childhood that are likely to extend into adulthood. Children who are obese are more at risk of high blood pressure and high cholesterol; impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes; asthma and musculoskeletal complications (Pollock 2015). It also increases the risk of psychosocial problems such as depression and poor socialisation (Fenner 2016; WHO 2016). Beyond its consequences in children, childhood obesity is an independent risk factor for adult obesity, with the associated health and economic implications for individuals as well as societies (WHO 2016). Overweight and obesity in adulthood are associated with increased risks of many cancers, coronary heart disease and stroke, and were among the top risk factors contributing to disability‐adjusted life years in 2015 (GBD 2017b).

Given the rising global burden of childhood obesity and its far‐reaching consequences, prevention, by addressing modifiable risk factors, is one of the most important actions. Obesity develops from sustained positive energy balance linked to various genetic, biological, behavioural, environmental and socioeconomic factors (Lobstein 2004; WHO 2016). Ethnicity has been linked to risk of obesity, with non‐white ethnicities living in westernised countries being at greater risk. In the USA, the prevalence of overweight among Hispanic and African‐American children rose twice as fast in a 12‐year period compared to white children (Lobstein 2004). Other factors that influence bodyweight measures in children include parental overweight or obesity, due to genetic and lifestyle influences. Lower socioeconomic status is also associated with higher bodyweight (Lobstein 2004; Ng 2014). There are greater absolute numbers of overweight and obese children in LMICs (Ng 2014). In high‐income countries, obesity risk is greater among populations of lower socioeconomic status whereas in developing countries it is more prevalent among wealthier populations (Lobstein 2004; Ng 2014). Rising levels of obesity are also seen among urban populations in developing countries due to westernised diets and the nutrition transition. This association between socioeconomic status and obesity risk is independent of the association between lower education levels and higher bodyweight measures (Lobstein 2004). Markers of maturation, such as age at menarche, stage of puberty or peak height velocity also influence body fatness, with children who mature more rapidly or earlier being at greater risk of obesity (Parsons 1999). Insufficient physical activity and excessive inactivity (e.g. television viewing) are also associated with risk of obesity (LeBlanc 2012; WHO 2004). Dietary risk factors associated with excess weight gain include high intake of sugar‐sweetened drinks or energy‐dense, nutrient‐poor foods (WHO 2004). Among these dietary risk factors is total fat intake, which may have important effects on body fatness measures in children, with international expert panels having debated on the optimal fat intakes (WCRF/AICR 2009), and which is the subject of this review.

Description of the intervention/exposure

The intervention or exposure of interest in this review is a reduced total fat intake in healthy non‐obese children and young people. Reduced fat intake may be achieved through interventions of nutrition education (e.g. counselling), changes in the food environment, peer‐support programmes, food provision or combinations of these.

Importantly, dietary intake is challenging to measure accurately, and any single common method used (such as the 24‐hour dietary recall, dietary record (DR), dietary history, and Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)) provides subjective estimates, with strengths and limitations related to validity (Shim 2014). Although it is well known that the research objective, hypothesis, design, and available resources need to be carefully considered to select the most appropriate dietary assessment method (Shim 2014), the fidelity of application of dietary assessment methods varies widely across research studies, and adherence to nutrition counselling by study participants also varies widely. These factors may introduce a lot of variation into the relationship between estimates of total fat intake and body fatness measures, which is often difficult to quantify accurately and leads to disparate findings and distortion in the estimated measure of association across studies. Additionally, studies usually quantify total fat intake in absolute grams per day, as a percentage of total energy (%TE) intake or both. These different measures are then used in various ways across studies in data analyses, which may add to the heterogeneity in effects and associations being examined. Studies have shown positive associations between proportion of energy intake as fat and bodyweight measures in children, with less clear associations in longitudinal compared to cross‐sectional studies (Johnson 2008; Lobstein 2004; McGloin 2002; Pérez‐Escamilla 2012). A meta‐regression in a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the effects of step I and II diets of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute national cholesterol education programme to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease in the general population and those at increased cardiovascular risk, respectively, found a strong relation between total fat intake and bodyweight (Yu‐Poth 1999). The German Nutrition Society guidelines state that whereas intervention and cohort studies in adults that have adjusted for energy intake show a probable lack of association between fat intake and risk of obesity, other studies that have not adjusted for energy intake, show a probable association between total fat intake and risk of obesity (Wolfram 2015).

Fat and energy intake can influence body fatness, and fat intake closely correlates with energy intake, which makes it difficult to separate their individual effects on bodyweight (Wolfram 2015). Change in body fatness that occurs with modifying intakes of total fat are mediated via changes in energy intakes. Additionally, differences in total energy intake can result in extraneous variation in nutrient intake because of individual differences in body size, physical activity and metabolic efficiency. Thus, to distinguish the isolated effect of fat intake on bodyweight, the effect of energy intake needs to be adjusted for in analyses (Jakes 2004; Rhee 2014). In observational studies, statistical models that adjust for prognostic variables, such as energy intake, attempt to simulate the comparability of randomised groups in an intervention study (Wolfram 2015). Similarly, in intervention studies where energy intake is ad libitum, it can confound the association between fat intake and weight gain, and isocaloric comparisons can be simulated through statistical modelling, controlling for the effect of energy intake.

Successfully isolating the effect of a single nutrient, such as fat, on weight is challenging given the complex mixture of nutrients and other components that make up our diets, typically characterised by various dietary patterns (different quantities, proportions, variety, and combinations of different foods and beverages) consumed over time. The nutrients provided by dietary patterns also have synergistic, additive or antagonistic effects on health. One review in Asian children on the relationship between dietary patterns as the exposure variable and childhood overweight and obesity as the outcome reported several meaningful, yet inconsistent, associations between dietary patterns and childhood overweight/obesity in children and adolescents, and heterogeneity of studies in terms of measures of dietary patterns and obesity standards (Yang 2012). Thus, carefully considering the way in which diets differ in components other than only total fat is part of better understanding the relationship between fat intake, weight and other health outcomes.

Another factor that can influence observable effects of total fat intake on bodyweight measures is the time‐varying nature of this relationship. Studies have different periods of observation and follow‐up, and different frequencies or intervals of study contacts and measurement. The duration of lower fat intake interventions or the duration of the exposure to lower total fat intake influence potential changes in bodyweight outcomes. It is thus important to consider this factor when examining the relationship between fat intake and weight, particularly in prospective cohort studies and the often secular nature of their data.

Why is it important to do this review?

Existing reviews looking at low‐fat diets included studies where weight loss was a goal of the intervention (Yu‐Poth 1999), which may have overstated any relation because the advice was to lower both fat and energy intake, did not explore the effect of low‐fat diets on weight or other body fatness outcomes (Schwingshackl 2013a), or looked at low‐fat intake as part of a wider health promotion intervention (Ni 2010). Other reviews that assessed body fatness were either limited to the effect of low‐fat dairy versus high‐fat dairy consumption (Benatar 2013), or investigated it as part of looking at overall dietary patterns (Ambrosini 2014), or diet quality (Aljadani 2015).

To examine these issues, a Cochrane Review including RCTs and cohort studies in adults and children was updated in 2015 (Hooper 2015a). With the aim of ensuring all relevant data in children were summarised, the WHO commissioned an expedited update of this systematic review in children only, to aid the understanding of the relation between total fat intake and bodyweight in children, in studies not intending to induce weight loss, with a view to inform the updating of their guidelines on total fat intake. Therefore, the combined review in children and adults (Hooper 2015a) was split into two reviews with the titles, "Effects of total fat intake on bodyweight in adults;" (in preparation) and "Effects of total fat intake on bodyweight in children." The 2015 combined (adults and children) review will be withdrawn with notes to direct readers to the two separate reviews.

Objectives

To assess the effects and associations of total fat intake on measures of weight and body fatness in children and young people not aiming to lose weight.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs of children and young people: trials of lower fat intake compared with usual diet or modified fat intake, with no intention to reduce weight (in any groups), continued for at least six months, unconfounded by non‐nutritional interventions and assessing a measure of body fatness at least six months after the intervention was initiated.

We included studies that randomised participants (i.e. parallel‐group design), and cluster randomised trials where at least six groups of children (i.e. clusters) were randomised. We had intended to exclude cross‐over trials (as previous weight gain or weight loss is likely to affect future weight trends) unless the first half of the cross‐over could be used independently, but we did not find any eligible cross‐over trials.

Cohort studies of children and young people: analytical prospective cohort studies that followed participants for at least 12 months after baseline assessment of total fat intake, and related baseline total fat intake to absolute or change in body fatness at least 12 months later. Cohort studies using explanatory models were included, but those that used baseline data to predict later body fatness without empirical data from the later time point (predictive models) were excluded.

Considering the research focus on identifying weight management strategies in overweight and obese children, and the nature of our question that addresses an intervention to prevent overweight and obesity, we anticipated not finding many longer‐term trials (randomised and non‐randomised) in children not intending to manage or reduce weight. We therefore excluded non‐randomised trials and rather included the next best available evidence for the question, which are analytical prospective cohort studies. Additionally, decision‐makers are required to identify and use the best available evidence in formulating recommendations, and this generally translates into evidence that is of the highest quality as assessed by GRADE, for each important outcome. The fact that we did not know a priori what type of evidence (i.e. from RCTs or observational studies) would be of highest quality was a further rationale for including prospective cohort studies.

Types of participants

We included studies in children and young people (aged 24 months to 18 years) with or without risk factors for cardiovascular disease, for example, a family history of cardiovascular disease, raised blood pressure or raised lipid levels. Participants could be of either sex, but we excluded children who were acutely ill, as well as disease‐ or condition‐specific populations, such as children with cystic fibrosis, autism or diabetes. We excluded intervention studies where the selection of the participants was primarily for raised weight or body mass index (BMI) with the intention to reduce weight.

Studies including a subset of eligible participants (e.g. aged 15 to 24 years) were included if results were reported separately for the eligible subset (e.g. 15 to 18 years). If not, such studies were only included if more than 80% of the baseline sample were aged 24 months to 18 years. We intended to exclude data from these studies in sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the primary meta‐analyses, but we did not pool data. Birth cohorts were only included if baseline total fat intake was related to absolute or change in body fatness at least 12 months later, and both these time points fell within our eligible age range, in which the earlier time point was regarded as the baseline.

Types of interventions

Interventions

We considered all RCTs of interventions stating an intention to reduce total dietary fat intake (by provision of nutrition education in any form, foods or both), when compared with a usual or modified fat intake.

We considered a lower fat intake to be one where fat intake was 30% or less of total energy (30%TE or less), and energy lost was at least partially replaced with carbohydrates (simple or complex), protein, or fruit and vegetables. We considered a 'usual' fat diet to be one with total fat intake greater than 30%TE, and considered a modified fat diet to be one with greater than 30%TE from fats, and that included higher levels of monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fats than a 'usual' fat diet. Interventions consisting of meals or food items lower in fat were included if they were provided with the intention of reducing fat intake over a period, thus targeting total fat intake.

As we were interested in the effects of total fat intake on bodyweight and fatness in everyday dietary intake over time (rather than in those aiming to reduce their bodyweight in weight‐reducing diets), we excluded studies aiming primarily to reduce the weight of some or all participants, as well as those that included only participants who had recently lost weight, or recruited participants primarily according to a raised bodyweight or BMI.

We excluded multifactorial interventions other than diet or supplementation, unless the effects of diet or supplementation could be separated such that the additional intervention was consistent between the intervention and control groups (e.g. studies that reduced fat and encouraged physical activity in one group and compared this with encouraging physical activity in the control group were included; studies that reduced fat and encouraged physical activity in one group and compared this with no interventions in the control group were excluded; studies that reduced fat and encouraged fruit and vegetables in one group and compared this with no intervention in the control group were included). Studies that selected groups based on a possible prognostic variable other than total fat intake, for example, genotype, were excluded.

We excluded Atkins‐type diets aiming to increase protein and fat intake, as well as studies where fat was reduced by means of a fat substitute (such as Olestra). We excluded studies that included enteral and parenteral feeding, as well as nutritional formula‐based weight‐reducing or other weight‐reducing diets.

Thus, we included all trials that intended to reduce dietary fat to 30%TE or less in one group compared to usual or modified fat intake (greater than 30%TE from fat) in another group regardless of the degree of difference between fat intake in the two groups (i.e. 'dose difference'). We intended to explore the effects of the difference in %TE from fat between control and intervention groups, as well as the effects of fat intake in the control groups and adherence to dietary fat goals in the intervention groups in subgroup analyses, but data did not allow us to perform these.

Exposures

For analytical prospective cohort studies, total dietary fat intake, in grams, as a percentage of total dietary energy intake or as one of the defining characteristics of a dietary pattern, had to be assessed at baseline and related to a measure of body fatness, or change in body fatness, at least one year later.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Body fatness, including bodyweight (kg), BMI (kg/m2), waist circumference (cm), skinfold thickness (mm) and percentage body fat.

Secondary outcomes

Other routine cardiovascular risk factors, namely circulating total low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations, and systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (SBP).

Height (adverse outcome). It is plausible that reducing total fat intake would reduce total energy and nutrient intake in children, possibly increasing the risk for suboptimal statural growth.

Tertiary outcomes (randomised controlled trials only)

Process outcomes, including changes in saturated and total fat intakes, as well as other macronutrients.

This is not a systematic review of the effects of lower fat on these secondary or tertiary outcomes, but we collated the outcomes from included studies to understand whether any effects on weight or body fatness might have been influenced by changes in these outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update in children only, we developed a new search strategy, which was run in the Cochrane library (May 2017, Issue 5) and in MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to May 2017), MEDLINE (PubMed, 1946 to May 2017) and Embase (Ovid, 1947 to May 2017) (Appendix 1). We searched comprehensively for all eligible studies, regardless of language and publication status.

Searching other resources

The previous authors (Hooper 2015a) searched the bibliographies of all identified systematic reviews for further trials and cohort studies, including Ajala 2013; Aljadani 2013; Aljadani 2015; Ambrosini 2014; Benatar 2013; Chaput 2014; Gow 2014; Havranek 2011; Hu 2012; Kratz 2013; Ni 2010; Schwingshackl 2013a; Schwingshackl 2013b; and Yang 2013. We searched the bibliographies of all included RCTs in this update. We also searched the tables of included and excluded studies in children in the previous version of this review that included both adults and children (Hooper 2015b).

To identify ongoing and unpublished studies, we searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (inception to 5 June 2017; WHO ICTRP, apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (inception to 5 June 2017; www.clinicaltrials.gov) (5 June 2017) (Appendix 1).

Data collection and analysis

This update was prepared in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014).

Selection of studies

One review author (CN) conducted an initial title screen using keywords to remove records that were obviously irrelevant. Keywords used for the title screen included words indicative of animal studies (e.g. 'murine'), ineligible participants (e.g. 'cystic fibrosis,' 'autism,' 'anorexia nervosa') and ineligible interventions (e.g. 'ketogenic,' 'parenteral,' 'olestra'). For quality assurance purposes, a second review author (MV) screened a random selection of 10% of the removed records, yielding a 98% inter‐rater agreement. Thereafter, two review authors independently screened all remaining titles and abstracts using Covidence (Covidence). We obtained the full‐text articles of records identified as potentially eligible, and screened these in duplicate and independently to determine final eligibility. When an abstract could not be rejected with certainty, we obtained the full text of the article for further evaluation. We were careful not to exclude studies based on outcome reporting. We did this by examining the objectives and methods of the study and deciding whether our eligible outcomes were likely to be within the scope of the study (i.e. considering whether one would expect them to be reported in the particular study, or they were measured and results were not reported). We only excluded studies when none of our eligible outcomes were reported and we judged that our eligible outcomes were outside of the scope of the study. We resolved any disagreements through discussion and consultation with two other review authors (CN or AS) when necessary.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data concerning participants, interventions or exposures, controls and outcomes, and trial or cohort quality characteristics onto forms designed and piloted for the review. We extracted data on potential effect modifiers from RCTs (including duration of intervention, control group fat intake, sex, year of first publication, difference in %TE from fat between the intervention and control groups, type of intervention (food or nutrition education provided), the dietary fat goals set for each group, baseline BMI and health at baseline), and from cohort studies (age, sex, energy intake, ethnicity, parental BMI, physical activity (or screen time, or both), pubertal stage and socioeconomic (income and educational) status). Where provided, we collected data on risk factors for cardiovascular disease (secondary and tertiary outcomes). When assessment of fat intake was reported using more than one dietary assessment method for the same outcome in the same participants, we selected the method deemed to be most appropriate and valid (e.g. multiple applications over time were better than a single once‐off application), or most likely to be relevant to answering our question. If different methods were judged to have similar validity, we used multiple food frequencies preferentially, as these were more likely to represent usual dietary intake (Gibson 2005).

We extracted outcome data according to the following time point ranges, when available: RCTs: from baseline to six months, six to 12 months, one to two years, two to five years and more than five years; cohort studies: baseline to one year, one to two years, two to five years, five to 10 years and more than 10 years. When outcome data were reported at more than one point within our time point ranges (e.g. three and five years), we extracted data from the latest point available within each range (five years in this example), unless the data from this time point were judged to be less reliable than the data from the earlier time point, in which case we used the more reliable data with an explanation.

All trial outcomes were continuous and where possible in trials, we extracted change data (change in the outcome from baseline to outcome assessment) with relevant data on variance for intervention and control groups (along with numbers of participants at that time point). Where change data were not available, we extracted data at study end (or other relevant time point) along with the variance and numbers of participants for each group. In the cohort studies, we extracted the most adjusted odds ratio, risk ratio, mean change or mean end values per group, when comparing the most exposed group of participants (highest fat intake) with the least exposed group (lowest fat intake). The most adjusted regression outputs (e.g. beta coefficient and its variance, P value, T value) were extracted when total dietary fat intake was assessed at baseline and related to a measure of body fatness, or change in body fatness, at least one year later. Two review authors extracted all data independently, with discrepancies resolved by another review author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We carried out 'Risk of bias' assessments independently and in duplicate. We assessed risk of bias in RCTs using the Cochrane tool for assessment of risk of bias (Higgins 2011a). For included RCTs, we also assessed whether trials were free of differences in diet (between intervention and control groups) other than dietary fat intake, as this may also influence differences in weight, body fatness and other related outcomes. We used the category 'other bias' for this assessment, and also to note any further issues of methodological concern.

For cohort studies we assessed the following.

Was adequate outcome data available?

Was there matching of less‐exposed and more‐exposed participants for prognostic factors associated with outcome, or were relevant statistical adjustments done?

Did the exposures between groups differ in components other than only total fat?

Could we be confident in the assessment of outcomes?

Could we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

Could we be confident in the assessment of presence or absence of prognostic factors?

Was selection of less‐exposed and more‐exposed groups from the same population? (Cochrane Methods; Guyatt 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

The effect measure of choice for continuous outcomes was the mean difference (MD). Where data allowed, we presented the MD alongside its 95% confidence interval (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

We found no cluster‐randomised or cross‐over trials. Where there was more than one intervention and control group, we selected the most relevant intervention group and most relevant control group for this review. We excluded intervention groups that were not appropriate for this review, or less appropriate than another group.

When primary outcomes were assessed at more than one time point in our time point ranges, we used the data from the latest time point available (in participants in the eligible age range) in general analyses. We also intended to use this data in relevant subgroup analyses, but we could not perform meta‐analyses as the data did not allow this. We were careful not to present the same study sample of participants more than once per outcome and time point range (e.g. Table 2), unless the different analyses were from the same study sample were clearly referenced (e.g. Tables 6 to 15).

Summary of findings 2. Total fat intake and body weight in children (cohort studies)a,b.

|

Total fat intake and bodyweightin children (cohort studies) A comprehensive table including data for all time points for each outcome can be found in Appendix 3 | ||||

|

Patient or population: boys and girls aged 24 months to 18 years Setting: communities, schools, households, healthcare centres in high‐income countries Exposure: total fat intake | ||||

| Outcomes |

No of studies (No of participants) |

Impact | Quality | What happens |

|

Weight (kg) Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years |

4 cohort studies (13,802) |

2 studies that adjusted for TE intake: After 3 years, "Dairy fat was not a stronger predictor of weight gain than other types of fat, and no fat (dairy, vegetable, or other) intake was significantly associated with weight gain after energy adjustment, nor was total fat intake;" no numerical results reported. After 3 years, for every 1% increase in TE intake from total fat of children, weight will decrease by 0.0011 kg. 2 studies that did not adjust for TE intake: After 4 years, weight of children with low‐fat intake (< 30%TE) will increase by 8.1 kg on average, and by 8.9 kg on average in children with high‐fat intake (> 35%TE). After 2 years, children with low‐fat intake (≤ 30%TE) will gain on average 0.2 kg per year more than children with high‐fat intakes (> 30%TE) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1,2 | When adjusted for TE, we were uncertain whether fat intake was associated with weight in children over 2 to 5 years. When not adjusted for TE, we were uncertain whether lower fat was associated with weight in children over 2 to 5 years. |

| Follow‐up: 5 to 10 years | 1 cohort study (126) |

1 study that did not adjust for TE intake: After 6 years, weight of children with low‐fat intake (< 30%TE) will increase by 16.8 kg on average, and by 13.9 kg on average in children with high‐fat intake (> 35%TE) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4,5,6 | We were uncertain whether fat intake was associated with weight over 5 to 10 years (1 study). |

|

BMI (kg/m2, kg/m2 per year, z‐score, percentile) Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years |

7 cohort studies (3143) |

4 studies that adjusted for TE intake: After 3 years, for every 1% increase in energy intake from total fat, BMI will decrease by 0.63 z‐score in boys but increase by 0.07 z‐score in girls. "Dietary factors were not associated with BMI across the three study years." After 3 years, for every 1% increase in energy intake from total fat, BMI will decrease by 0.00008 kg/m2. After 4 years, increase in the total fat intake, will increase BMI by 0.087 z‐score. The model explained 48% of variance in the change of BMI z‐score. 2 studies that did not adjust for TE intake: After 2.08 years, low‐fat intake (≤ 30%TE) will result in a 0.02 kg/m2 per year greater increase in BMI on average, compared to high‐fat intake (> 30%TE). After 3 years, for every 1% increase in energy intake from total fat, BMI will decrease by 0.01 percentile in girls. 1 study where TE adjustment was not applicable, as TE was part of exposure: After 3 years, for every 1 z‐score increase in the energy‐dense, high‐fat and low‐fibre dietary pattern, BMI will increase by 0.03 z‐score in boys and by 0.99 z‐score in girls. After 3 years, the ratio of odds for being overweight/obese was 1.04 greater in boys and 1.02 greater in girls with higher dietary pattern z‐scores, compared to the odds in boys and girls with lower dietary pattern z‐scores. |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low6,7,8 |

We were uncertain whether fat intake was associated with BMI in children over 2 to 10 years. |

| Follow‐up: 5 to 10 years | 4 cohort studies (1158) |

3 studies that adjusted for TE intake: After 6 years, for every 1% increase in energy intake from total fat, BMI will decrease by 0.011 z‐score in boys but increase by 0.005 z‐score in girls. After 9 years, increase in the total fat intake will increase BMI by 0.122 z‐score. After 10 years, for every 1% increase in energy intake from total fat, BMI will increase by 0.029 kg/m2 in white girls and by 0.012 kg/m2 in black girls. 1 study that did not adjust for TE intake: After 6 years, for every 1 g increases in the fat intake, BMI will increase by 0.01 kg/m2 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low6,9 | |

|

LDL‐C (mmol/L) Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years |

1 cohort study (1163) |

1 study where TE adjustment not applicable, as TE was part of exposure: After 3 years, for every 1 z‐score increase in the energy‐dense, high‐fat and low‐fibre dietary pattern, LDL‐C will increase by 0.001 mmol/L in boys and 0.04 mmol/L in girls |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low4,5,6,11 | We were uncertain whether fat intake was associated with LDL‐C in children over 2 to 5 years (1 study). |

|

HDL‐C (mmol/L) Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years |

2 cohort studies (1393) |

1 study that adjusted for TE intake: After 3 years, for every 1% increase in energy intake from total fat, HDL‐C will decrease by 0.21 mmol/L in girls. 1 study where TE adjustment not applicable, as TE was part of exposure: After 3 years, for every 1 z‐score increase in the energy‐dense, high‐fat and low‐fibre dietary pattern, HDL‐C will decrease by 0.002 mmol/L in boys but increase by 0.02 mmol/L in girls. |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low11,12 | When adjusted for TE, fat intake may be inversely associated with HDL‐C in girls over 2 to 5 years (1 study). When not adjusted for TE, fat intake may make little or no difference to HDL‐C in girls over 2 to 5 years (1 study). |

|

Triglycerides (mmol/L) Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years |

1 cohort study (1163) |

1 study where TE adjustment not applicable, as TE was part of exposure: After 3 years, for every 1 z‐score increase in the energy‐dense, high‐fat and low‐fibre dietary pattern, triglycerides will increase by 1% in either boys or girls. |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low4,5,6,11 | We were uncertain whether fat intake was associated with triglycerides in children over 2 to 5 years (1 study). |

|

Height (cm) Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years |

3 cohort studies (973) |

1 study that adjusted for TE intake: After 3 years, for every 1% increase in energy intake from fat, height in children will decrease by 0.0009 cm on average. 2 studies that did not adjust for TE intake: After 2 years, low‐fat intake (≤ 30%TE) will result in a 0.2 cm per year greater increase in height on average compared to high‐fat intake (> 30%TE). After 4 years, on average children in low‐fat intake (< 30%TE) gain 27.9 cm in height, while children in high‐fat intake (> 35%TE) gain 28.3 cm in height. |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low6,10 | We were uncertain whether fat intake was associated with height in children over 2 to 10 years. |

| Follow‐up: 5 to 10 years Age at baseline: 2 years |

1 cohort study (126) |

1 study that did not adjust for TE intake: At 6 years, on average children in low‐fat intake (< 30%TE) gain 44.9 cm in height while children in high‐fat intake (> 35%TE) gain 40.3 cm in height. |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4,5,6 | |

|

BMI: body mass index; HDL‐C: high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C: low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; MD: mean difference; TE: total energy. aNotes: Some cohort studies reported more than one eligible analysis for the same outcome (e.g. BMI as continuous or binary outcome) or different measures of exposure (e.g. fat intake as continuous %TE or as binary classification of less‐exposed vs more‐exposed). In these cases, we selected outcomes and exposure measures so as not to use the same study sample of participants more than once per outcome and time point range in the table. For all outcomes, there were too few studies to assess publication bias. | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

1Although, risk of bias was concerning (studies with strong contributions did not adjust for all important prognostic variables), plausible residual confounding would likely reduce the demonstrated effect in the studies that did not adjust for total energy intake; thus we chose not to downgrade for risk of bias.

2Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: in studies reporting variance, the variance included no effect and important benefit or harm.

3Although risk of selection bias (no matching of exposed and non‐exposed groups, or statistical adjustments) and attrition bias (> 50% attrition) was concerning, plausible residual confounding would likely reduce the demonstrated effect as this study did not adjust for total energy; thus we chose not to downgrade for selection bias.

4Only 1 study for this outcome, therefore we could not rate for inconsistency.

5Downgraded by 1 for indirectness: a single study in a high‐income country likely has limited generalisability.

6Imprecision was considered, but we considered a decision would not impact on the rating and thus no judgement was made for imprecision.

7Downgraded by 1 for risk of bias: risk of selection bias: 5 studies did not match exposed and non‐exposed groups or make important statistical adjustments; high risk of detection bias: dietary assessment for 3 studies were not adequately rigorous.

8Downgraded by 1 for inconsistency: some studies reported small to large positive associations between exposure and outcome, while others reported no association or a small to medium inverse association between exposure and outcome.

9Downgraded by 1 for risk of bias: risk of selection bias: 2 studies with strongest contributions, did not adjust for all important prognostic variables; high risk of detection bias: dietary assessment in 1 study was not adequately rigorous.

10Downgraded by 1 for risk of bias: risk of selection bias; no matching of exposed and unexposed groups or adjustment for all important prognostic variables.

11Study was judged to have a lower overall risk of bias; attrition < 50% and satisfactory assessment of exposure.

12Not downgraded for serious imprecision as judged to be precise estimates of no effect in both studies.

Dealing with missing data

Where study authors had not reported all relevant statistics per outcome (e.g. SD of change per group for continuous data), we attempted to calculate or estimate the required data from other statistics reported in the study by using relevant formulas from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). If we could not calculate or estimate these statistics with reasonable confidence, we emailed the study authors. Where we did not receive a timely response, or where we received a response for which we lacked confidence, we did not impute the missing values but instead reported the available results in a table. We indicated in the tables where we made use of unpublished data supplied to us by study authors.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We intended to examine heterogeneity per outcome and time point by visual inspection of the forest plots (i.e. we looked at physical overlap of CIs across the included studies). We intended to assess statistical heterogeneity among the intervention effects across the included studies in the meta‐analyses as follows:

Chi2 test for heterogeneity;

I2 statistic to quantify heterogeneity; and

Tau2 statistic to measure the extent of heterogeneity.

In meta‐analyses, we intended to consider heterogeneity as an I2 value of greater than 30% and either a Chi2 of less than 0.1 or Tau2 greater than 0. We planned to perform subgroup analyses to explore heterogeneity, but data did not allow meta‐analyses (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Where more than 10 included studies addressed a primary outcome, we intended to used funnel plots to assess the possibility of small‐study effects. For future review updates, in the case of asymmetry, we will consider various explanations such as publication bias, poor study design and the effect of study size.

Data synthesis

We sought to combine data by the inverse variance method in random‐effects meta‐analysis to assess MDs between lower and higher fat intake arms, but data did not allow for any meta‐analyses. Where possible, we converted variables to comparable units to allow pooling of data if appropriate. We planned to conduct separate meta‐analyses of data from RCTs and data from cohort studies, and only where data from separate studies were similar enough to be combined (see Assessment of heterogeneity).

We intended not to use end data in meta‐analysis, where the difference between the intervention and control groups at baseline was greater than the change in that measure between baseline and endpoint in both groups. Instead, we intended to use change data in forest plots but without SDs, so the data did not add to the meta‐analyses but instead provided comparative information. However, this was not relevant in this update as we could not meta‐analyse the data.

'Summary of findings' tables

Based on the methods described in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011), we prepared two 'Summary of findings' tables to present the results of the RCTs and cohort studies separately. In both 'Summary of findings' tables we included our primary outcome of body fatness (measured by weight‐for‐age z‐score, weight and BMI), cardiovascular risk factors (total cholesterol, LDL, HDL and triglyceride concentrations), and height (in cm or height‐for‐age z‐score). We deemed these outcomes the most important as guided by our question and the primary purpose of the review. Given the large number of time points examined, we selected time points for inclusion in the tables by considering the influence of:

height gain on bodyweight change in children;

intervention fidelity over time in RCTs; and

the challenges with repeated dietary intake measurements over time in cohort studies.

Summary tables for all time points are presented in Appendix 2 (RCTs) and Appendix 3 (cohort studies).

We used the GRADE system to rank the quality of the evidence using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT). As data were reported heterogeneously, and meta‐analyses were not possible, we presented results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table for cohort studies (drawing on McNeill 2017 as an example).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For this update, we classified all dietary interventions and exposures as lower fat versus usual or modified fat. We intended to compare the intervention effects or associations across the following subgroups, but the available data did not allow us to perform any of these:

difference in %TE from fat between lower fat and control groups in RCTs (e.g. up to 5%TE from fat, 5%TE to 10%TE from fat, 10%TE to 15%TE from fat, 15%TE or greater from fat or unknown difference);

type of intervention in RCTs (e.g. nutrition counselling only versus nutrition counselling plus food provided);

adherence to fat intake goals in the intervention group in RCTs (e.g. achieved 30%TE from fat or less versus did not achieve this);

weight status at baseline (e.g. by BMI‐for‐age z‐score);

reported estimated energy reduction in the intervention compared with the control group during the intervention period in RCTs (e.g. estimated energy intake the same or greater in the lower fat group, energy intake 1 kcal/day to 100 kcal/day lower in the lower fat group, 101 kcal/day to 200 kcal/day lower in the lower fat group, greater than 200 kcal/day lower in the lower fat group); and

cohort studies that statistically adjusted for energy intake when relating total fat intake to body fatness versus cohort studies that did not adjust for energy intake.

Sensitivity analysis

Where possible, we carried out sensitivity analyses for primary outcomes, assessing the effect of:

our selected time point ranges by including only the longest follow‐up data per study; and

our selected time point ranges by including only the shortest follow‐up data per study.

We had planned to perform other sensitivity analyses; however, since we only identified three RCTs and did not meta‐analyse cohort studies, we deemed other sensitivity analyses inappropriate. In future updates, it may be feasible to assess the influence of excluding studies with unclear or inadequate allocation concealment in RCTs, performing fixed‐effect meta‐analyses (rather than random‐effects) (Higgins 2011b), excluding studies with only a subset of eligible participants, excluding studies that were not free of systematic differences in care (performance bias) (or where it was unclear) and excluding studies that were not free of dietary differences other than total fat (or where it was unclear).

Results

Description of studies

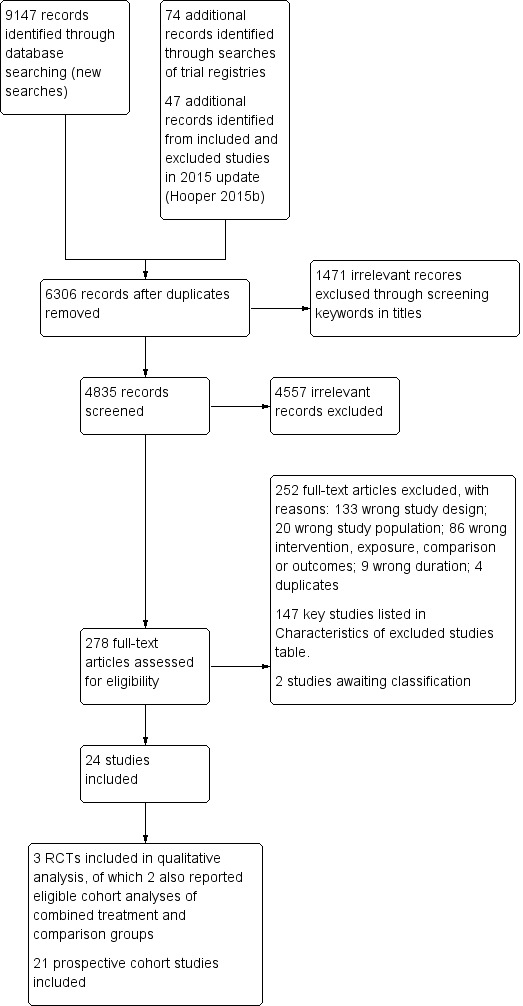

The flow diagram of search results and study selection for this systematic review update is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram. RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Results of the search

The search for RCTs and cohort studies in adults and children in a previous version of this review (Hooper 2012) identified 32,220 titles and abstracts from the electronic searches plus 28 further potential studies from other sources. For the previous update (Hooper 2015a), the electronic searches identified 7729 possible titles and abstracts, plus review authors assessed a further 24 potential studies after checking for potentially relevant trials and cohort studies included in other systematic reviews. Of these 7753 potential titles and abstracts, the review authors assessed 218 full‐text articles for eligibility (additional to the 465 assessed for the original review). This review in adults and children in 2015 included one RCT and 11 cohort studies in children (Hooper 2015b). Our flow diagram in Figure 1 does not include the search results from previous versions of this review, as they also included studies in adults and are thus not combinable with the search results for this review update.

Our new search strategy tailored for children (Appendix 1), yielded 9301 records, with 6306 records remaining following duplicate removal. After removing obviously ineligible records using a keyword search, we screened 4835 titles and abstracts, with 278 full‐texts identified as potentially eligible. After excluding 252 studies with reasons and two studies awaiting classification, we included 24 studies comprising three parallel‐group RCTs (reported in 12 records) and 21 prospective cohort studies (92 eligible analyses, reported in 47 records) (Figure 1). Two of the included RCTs (Obarzanek 2001 (RCT); Tershakovec 1998 (RCT)) also reported eligible cohort analyses that we included with the cohort data, and these are presented throughout the review as two 'additional' study references (Obarzanek 1997 (cohort); Tershakovec 1998 (cohort)).

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table for detailed characteristics of all included studies.

Randomised controlled trials

Study location, participants and duration

Mihas 2010: conducted in Greece; boys and girls aged 12 to 13 years with no known cardiovascular disease risk factors; follow‐up over 17 months.

Obarzanek 2001 (RCT): conducted in the USA; boys and girls aged seven to 11 years with primary elevated serum LDL‐cholesterol levels; follow‐up over approximately seven years.

Tershakovec 1998 (RCT): conducted in the USA; boys and girls aged four to 11 years who were hypercholesterolaemic; follow‐up over one year.

Interventions

Interventions to reduce total fat intake were delivered as combinations of individual and group counselling and education sessions in clinics, schools and homes, with some involvement of parents in the sessions and one trial also including telephone contacts between sessions. Sessions were delivered by paediatric dieticians, nutritionists, behaviourists or trained and supervised teachers, as classroom curriculum or using other education resources, such as posters, workbooks, audiotape stories and picture books. Detailed descriptions of the interventions in the three RCTs are shown in Table 4.

1. Summary of the intervention details (using TIDieRa items) for each RCT in the systematic review.

| Recipients | Why | What (materials) | What (procedures) | Who provided | How and where | When and how much | Strategies to improve or maintain intervention fidelity; tailoring and modification | Extent of intervention fidelity |

| Tershakovec 1998 (RCT) | ||||||||

| 4‐ to 9‐year‐old children with hypercholesterolaemia (plasma total cholesterol > 4.55 mmol/L, fasting plasma LDL‐C 2.77‐4.24 mmol/L for boys and 2.90‐4.24 mmol/L for girls), at ≥ 85% of ideal body weight. | Limited dietary fat was recommended for children aged > 2 years, but there were concerns that lower fat intake of children may affect their growth. Trial evaluated growth of children with hypercholesterolaemia completing an innovative, physician‐initiated, home‐based nutrition education programme or standard nutrition counselling that aimed to lower dietary fat intake. | Nutrition education programme complied with recommendations of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Blood Cholesterol Levels in Children and Adolescents. | Children and ≥ 1 parent (usually mother) attended 45‐ to 60‐minute counselling session with paediatric dietician. Children and parents in at‐risk control and not‐at‐risk control groups were not provided educational information or materials. | 1) Not described; 2) paediatric registered dieticians. | 1) Audiotape stories and picture books and follow‐up paper/pencil activities for children as well as manual for parents. Story and activities to be completed each week; 2) face‐to‐face individual counselling by a dietician. 1) At home; 2) paediatric practice. |

10 weeks with 1) talking‐book lesson; 2) 45‐60 minutes counselling session each week. | Not described Tailoring and modification of intervention during trial were not described. |

1) 71/88; 2) 77/86 completed intervention programmes and returned for evaluation at 3 months after baseline. |

| Obarzanek 2001 (RCT) | ||||||||

| Prepubertal boys and girls aged 8‐11 years with LDL‐C levels ≥ 80th and < 98th percentiles for age and sex percentiles of the Lipid Research Clinics population. | Aimed to assess feasibility, safety, efficacy and acceptability of lowering dietary intake of total fat, saturated fat and cholesterol to decrease LDL‐C levels. | Intervention group received dietary counselling sessions based on National Cholesterol Education Programme guidelines: 28% of energy from total fat, < 8% from saturated fat, > 9% from polyunsaturated fat, and < 75 mg/1000 kcal of cholesterol per day, not to exceed 150 mg/day. Guidebooks including activities and recipes on diets and food recommendations given to participants and their families. | In first 6 months, 6 weekly and then 5 biweekly group sessions were led by nutritionists and behaviourists, and 2 individual visits were held with nutritionist. Over second 6 months, 4 group and 2 individual sessions were held. During 2nd and 3rd years, group and individual maintenance sessions were held 4‐6 times/year, with monthly telephone contacts between group sessions. During 4th year of follow‐up, 2 group events + 2 individual visits conducted with additional telephone contacts as appropriate. | Nutritionists and behaviourists | 1) Group sessions and 2) individual visits were held, accompanied by telephone contacts in between sessions. 1) At clinics, 2) at home |

6 weekly, 5 biweekly group sessions and 2 individual visits during first 6 months; 4 group and 2 individual sessions during second 6 months; 4‐6 maintenance sessions with telephone contacts between sessions during 2nd and 3rd years; 2 group and 2 individual sessions with telephone contacts as appropriate by 4th year. | By 4th year of follow‐up, individual visits used an individualised approach based on motivational interviewing and stage of change for increasingly busy teenagers. Tailoring and modification of intervention during trial not described. |

295/334 attended the last visit (> 5 years' follow‐up). |

| Mihas 2010 | ||||||||

| Students aged 12‐13 years from an urban area in Greece. | Aimed to evaluate the short‐term (15‐day) and long‐term (12‐month) effects of a 12‐week school‐based health and nutrition interventional programme regarding energy and nutrient intake, dietary changes and BMI. | Teaching material for teachers and workbooks for students on nutrition‐dietary habits and physical activity and health based on Social Learning Theory Model were developed and distributed to teacher and each student. | Multicomponent workbooks covering mainly dietary issues, but also dental health hygiene and consumption attitudes, were produced with each student being supplied a workbook. The class home economics teacher implemented 12‐hour‐classroom curriculum incorporating health and nutrition promotion during 12 weeks. 2 meetings were conducted with parents (given screening results of children; presentations given on dietary habits of children to improve health profile of children and prevent development of chronic diseases in the future). Cues and reinforcing messages in the form of posters and displays were provided in the classroom. | Educational intervention (classroom curriculum) delivered by class home economics teachers who were trained and supervised by health visitor or family doctor. | Classroom curriculum; cues and reinforcing messages in the form of posters and displays provided in classroom; nutrition education meetings for parents in group. At school. |

12 hours of classroom material, 2 meetings for parents during a 12‐week period. | Health visitor or family doctor supervised the programme implementation of class home economics teachers who were given 2 × 3‐hour seminars with aims to familiarise teachers about objectives of intervention and their role therein, and to increase their awareness of significance of incorporating health and nutrition in their curriculum before delivering the intervention. Tailoring and modification of intervention during trial not described. |

107/109 participation rates at 15‐days' follow‐up and 98/109 at 12 months' follow‐up. |

aTIDieR: Template for Intervention Description and Replication, template for this table from Hoffman 2017.

BMI: body mass index; LDL‐C: low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Funding and authors' declarations of interest

The older of the US trials was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL43880‐03), the Howard Heinz Endowment, and the University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation (Tershakovec 1998 (RCT)), and the other US trial by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Obarzanek 2001 (RCT)). There were no authors' declarations of interest reported for these trials in the articles we assessed. The trial in Greece was funded by the Ministry of Education and the National Foundation for the Youth and the authors declared no competing interests (Mihas 2010).

Prospective cohort studies

Study location, participants and duration

In most studies, children or families were recruited conveniently from schools, communities, daycare centres, clinics or hospitals, or were sampled from existing large cohort study samples. Participants in all included cohort analyses were healthy children, except for the two cohort analyses of the RCTs that included children with hypercholesteraemia (Tershakovec 1998 (cohort)) or primary elevated serum LDL‐cholesterol levels (Obarzanek 1997 (cohort)).

Mean age at baseline ranged across studies from two years to 14 years. Five studies followed children from baseline to one year (Bogaert 2003; Butte 2007; Niinikoski 1997a; Schwandt 2011; Tershakovec 1998 (cohort)), five studies for more than one to two years (Davison 2001; Klesges 1995; Lee 2001; Lee 2012; Setayeshgar 2017), seven studies for more than two to five years (Appannah 2015; Berkey 2005; Boreham 1999; Cohen 2014; Jago 2005; Obarzanek 1997 (cohort); Shea 1993), four studies for more than five to 10 years (Ambrosini 2016; Brixval 2009; Morrison 2008; Skinner 2004), and two studies followed children for more than 10 years (Alexy 2004; Magarey 2001).

Of the 21 included prospective cohort studies, one study was conducted in a middle‐income country (Korea; Lee 2012). All the others were conducted in high‐income countries, as follows: 10 in the USA (Berkey 2005; Butte 2007; Cohen 2014; Davison 2001; Jago 2005; Klesges 1995; Lee 2001; Morrison 2008; Shea 1993; Skinner 2004), one in Canada (Setayeshgar 2017), one in the UK (Ambrosini 2016), one in Northern Ireland (Boreham 1999), two in Germany (Alexy 2004; Schwandt 2011), one in Denmark (Brixval 2009), one in Finland (Niinikoski 1997a), and three in Australia (Appannah 2015; Bogaert 2003; Magarey 2001). Most studies included both sexes and all ethnicities, except one study that only included white children (Skinner 2004), one study that only included Hispanic children (Butte 2007), two studies that only included girls (Cohen 2014; Lee 2001), one study that only included white girls (Davison 2001), and one study that only included black and white girls (Morrison 2008).

Exposures

Exposures to total daily fat intake were estimated using different methods including 24‐hour dietary recall, FFQ and DRs. To examine associations with body fatness outcomes over time, total fat intake exposure estimates were expressed in different units, and applied in different ways across studies, as follows:

binary fat intake exposures: lower versus higher percentiles of fat intake, or lower versus higher fat intake groups (based on dietary intake assessments), and using cut‐offs of %TE from fat (e.g. 30%TE or less and greater than 30%TE or less than 30%TE and greater than 35%TE) (Alexy 2004; Ambrosini 2016; Lee 2001; Niinikoski 1997a; Shea 1993; Tershakovec 1998 (cohort);

continuous fat intake exposures: in %TE, absolute number of grams, per 10 grams of intake, by number of servings (Berkey 2005; Bogaert 2003; Boreham 1999; Brixval 2009; Butte 2007; Cohen 2014; Davison 2001; Jago 2005; Klesges 1995; Lee 2012; Morrison 2008; Obarzanek 1997 (cohort); Schwandt 2011; Setayeshgar 2017; Skinner 2004), or as a high‐fat dietary pattern in two studies (Ambrosini 2016; Appannah 2015), with two studies using both binary and continuous fat intake exposures to apply the exposure variables in analyses (Appannah 2015; Magarey 2001).

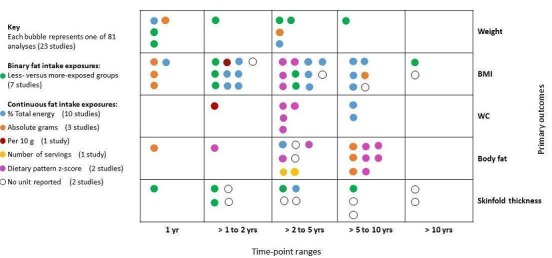

Figure 2 presents the spread of the different ways in which total fat intake estimates were expressed and applied to examine associations with body fatness in the 81 analyses that reported primary outcomes (weight, BMI, waist circumference, body fat and skinfold thickness) in the five time point ranges. The heterogeneous application of fat intake exposure at different time points for different outcomes across the included studies is evident in Figure 2.

2.

The bubble‐plot presents the spread of the different ways in which total fat intake estimates were expressed and applied to examine associations with body fatness in the 81 analyses, reporting primary outcomes in the five time point ranges. Combining the many various total fat intake exposure estimates reporting on the same outcome in the same time point range was deemed inappropriate. BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; yr: year.

The studies reporting dietary patterns as the exposure used reduced rank regression to identify dietary patterns or combinations of food intake, that attempted to explain the maximum variation in a set of response variables hypothesised to be on the pathway between food intake and obesity (Ambrosini 2016; Appannah 2015). Participants were scored for each dietary pattern at each age using a z‐score that quantified how their reported dietary intake reflected each dietary pattern relative to other respondents in the study sample. The model used calculates dietary z‐scores for each respondent as a linear, weighted combination of all their standardised food group intakes by using weights unique to each dietary pattern. Increasing intakes of foods with positive factor loadings increases the dietary pattern z‐score, and increasing intakes of foods with negative factor loadings decreases the dietary pattern z‐score. The energy‐dense, high‐fat, low‐fibre dietary pattern reflected high intakes of processed meat, chocolate and confectionery, low‐fibre bread, crisps and savoury snacks, and fried and roasted potatoes (high intake of these foods increased the participant's dietary pattern z‐score).

Funding and authors' declarations of interest

Five of the 21 cohort studies had combined public and private funding including from the food industry and financial services industry (Berkey 2005; Bogaert 2003; Lee 2001; Niinikoski 1997a; Skinner 2004). In these studies, no author declarations of interest were reported. Two studies did not report their funding sources (Brixval 2009; Lee 2012), and in these studies, authors declared no conflicts of interests. The remaining 14 cohort studies were publicly funded, with six of these reporting no conflicts of interest by authors (Ambrosini 2016; Appannah 2015; Butte 2007; Cohen 2014; Morrison 2008; Setayeshgar 2017), and the rest containing no author declarations of interest.

Excluded studies

After full‐text screening, we excluded 252 studies. Key studies (n = 147) with their reasons for exclusion are in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Briefly, 133 studies were excluded for inappropriate study design (98 did not analyse children's baseline to fat intake to body fatness at least 12 months later; 16 cross‐sectional; five reviews; two editorials; three analysed twin‐pairs; six non‐RCTs; one randomised fewer than six clusters; one case‐control; one prediction model used), 20 for unsuitable study population (e.g. adults or overweight children with intention to reduce weight), 58 for inappropriate intervention (e.g. school lunch programme), 14 for inappropriate exposure (e.g. dairy food intake or cereal intake), eight for no eligible outcomes reported and our outcomes deemed to be outside of the scope of the study (e.g. psychological outcomes), six for inappropriate comparison, nine for inappropriate duration (e.g. less than one year for cohort studies) and four duplicates. We excluded the Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project (STRIP) trial (Niinikoski 2014), as the primary intention of the intervention was to reduce saturated fat intake through replacement with unsaturated fat, thus changing the 'quality' of fat intake or composition of fat intake. Our question primarily concerns the quantity of total fat intake.

Studies awaiting classification

We found two published abstracts from the one study awaiting assessment (Khalil 2015) and contacted the authors for additional information, but did not receive a response in time for assessment for inclusion in this review. We also contacted the authors of Twisk 1998, but did not receive the requested information in time.

Ongoing studies

We found no eligible ongoing studies.

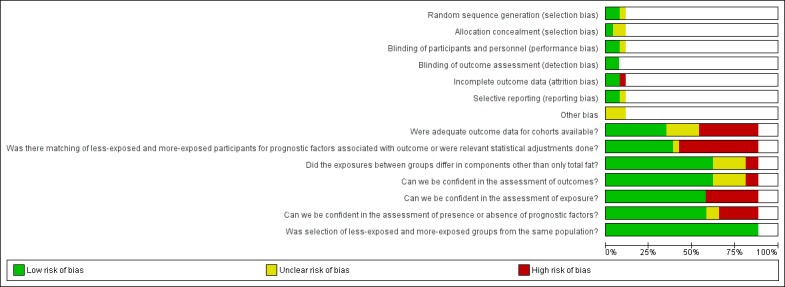

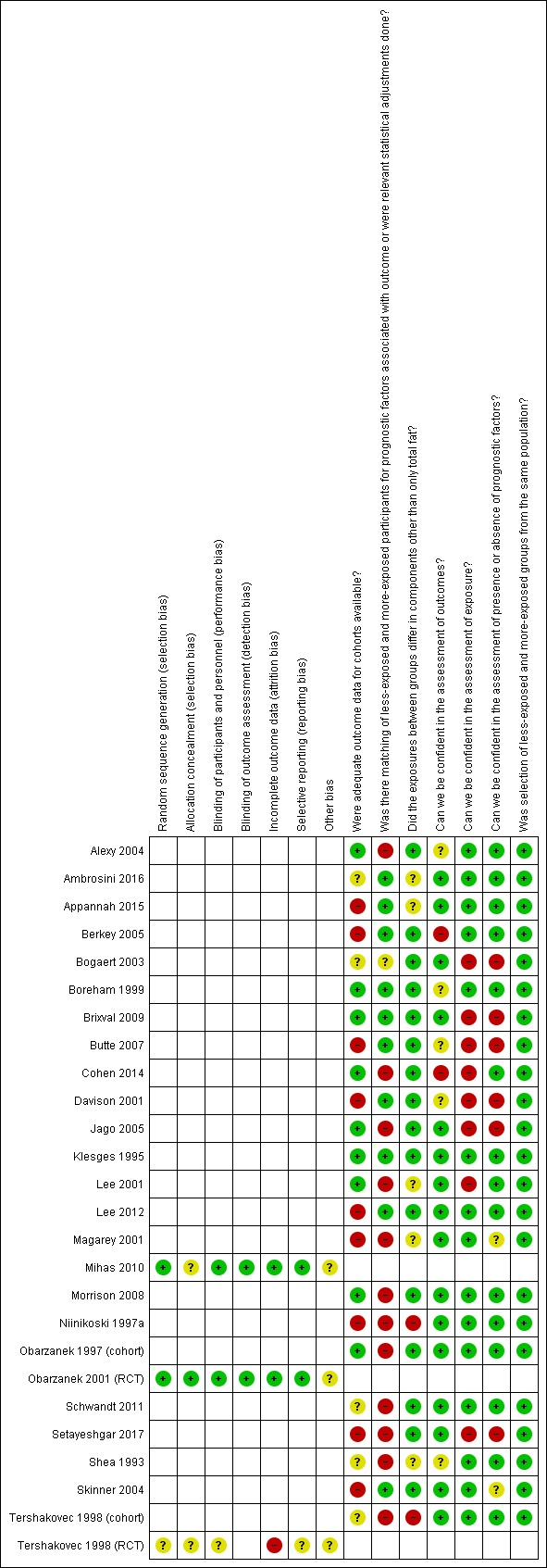

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 3 represents each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included RCTs and across all included cohort studies. A visual representation of the risk of bias for each domain per included RCT and cohort study is presented in Figure 4. For the two trials that also report eligible cohort analyses (Obarzanek 1997 (cohort); Tershakovec 1998 (cohort)), we reported risk of bias judgements for each study design.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. RCT: randomised controlled trial.

See the Characteristics of included studies table for details of risk of bias judgements per trial and per cohort study.

Validity of randomised controlled trials

Allocation (selection bias)

We judged two RCTs to have an unclear risk of selection bias because allocation concealment was not reported (Mihas 2010; Tershakovec 1998 (RCT)), and Tershakovec 1998 (cohort) also lacked clarity in the reporting of random sequence generation. Obarzanek 2001 (RCT) was at low risk of selection bias.

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)

Tershakovec 1998 (RCT) did not report on blinding and we judged this study at unclear risk of performance and detection bias. Obarzanek 2001 (RCT) reported blinding of outcome assessors and not of participants. However, since this was unlikely to have influenced the primary study outcomes, we judged this trial at low risk for performance and detection bias. Similarly, we judged Mihas 2010 at low risk of bias for this domain because although the authors reported blinding was not feasible, it was unlikely that the primary outcome was influenced by a lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

We assessed those studies that lost more than 10% of participants in total at high risk of attrition bias, unless they adequately report dropout analyses showing no differences in reasons and key characteristics between completers and non‐completers. Attrition rates were greater than 10% over the one‐year follow‐up for Tershakovec 1998 (RCT) and reasons for missing outcome data per group were not provided; thus, it was at high risk of bias. We assessed the other two RCTs at low risk of attrition bias due to reported attrition rates of less than 10% (Mihas 2010; Obarzanek 2001 (RCT)).

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

Tershakovec 1998 (cohort) was at unclear risk of reporting bias because outcomes reported by the authors were not prespecified. We judged the other two RCTs at low risk of reporting bias because they prespecified their outcomes in the methods section and addressed them in the results section (Mihas 2010; Obarzanek 2001 (RCT)). Generating funnel plots was not possible due to the small number of included trials.

Other potential sources of bias

All three RCTs were at unclear risk of 'other bias' because limited information on the control diet prescription made it difficult to judge if the intervention and control diets differed in components other than only total fat.

Validity of cohort studies

Was adequate outcome data available? (attrition bias)

Nine studies were at high risk of attrition bias due to high attrition (greater than 5% attrition per year) and reasons for attrition were not reported or incompletely described (Appannah 2015; Berkey 2005; Butte 2007; Davison 2001; Lee 2012; Magarey 2001; Niinikoski 1997a; Setayeshgar 2017; Skinner 2004). Four studies with high attrition conducted dropout analyses of baseline anthropometric and dietary intake variables: two were at low risk of bias because they adequately reported no difference between completers and non‐completers (Brixval 2009; Klesges 1995); and the other two were at unclear risk of bias because insufficient information was provided to permit judgement (Bogaert 2003; Tershakovec 1998 (cohort)). Attrition bias could not be determined for two studies (judged at unclear risk of bias), as Shea 1993 did not report how many children completed the last follow‐up visit, and Schwandt 2011 reported the dropout analysis inadequately. The remaining seven studies had low risk of attrition bias.

Was there matching of less‐exposed and more‐exposed participants for prognostic factors associated with outcome, or were relevant statistical adjustments done? (selection bias)