Abstract

Background

Diabetes is the commonest cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Both conditions commonly co‐exist. Glucometabolic changes and concurrent dialysis in diabetes and CKD make glucose‐lowering challenging, increasing the risk of hypoglycaemia. Glucose‐lowering agents have been mainly studied in people with near‐normal kidney function. It is important to characterise existing knowledge of glucose‐lowering agents in CKD to guide treatment.

Objectives

To examine the efficacy and safety of insulin and other pharmacological interventions for lowering glucose levels in people with diabetes and CKD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 12 February 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs looking at head‐to‐head comparisons of active regimens of glucose‐lowering therapy or active regimen compared with placebo/standard care in people with diabetes and CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) were eligible.

Data collection and analysis

Four authors independently assessed study eligibility, risk of bias, and quality of data and performed data extraction. Continuous outcomes were expressed as post‐treatment mean differences (MD). Adverse events were expressed as post‐treatment absolute risk differences (RD). Dichotomous clinical outcomes were presented as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

Forty‐four studies (128 records, 13,036 participants) were included. Nine studies compared sodium glucose co‐transporter‐2 (SGLT2) inhibitors to placebo; 13 studies compared dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitors to placebo; 2 studies compared glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) agonists to placebo; 8 studies compared glitazones to no glitazone treatment; 1 study compared glinide to no glinide treatment; and 4 studies compared different types, doses or modes of administration of insulin. In addition, 2 studies compared sitagliptin to glipizide; and 1 study compared each of sitagliptin to insulin, glitazars to pioglitazone, vildagliptin to sitagliptin, linagliptin to voglibose, and albiglutide to sitagliptin. Most studies had a high risk of bias due to funding and attrition bias, and an unclear risk of detection bias.

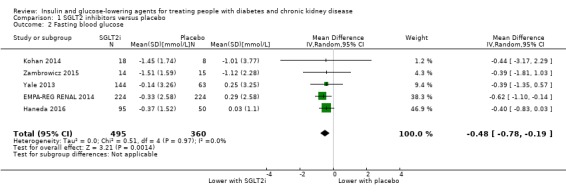

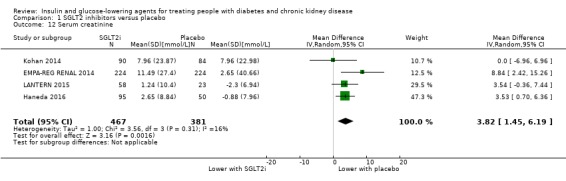

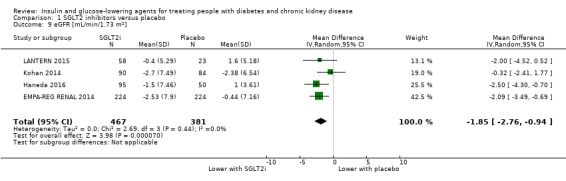

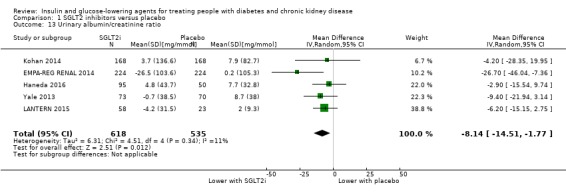

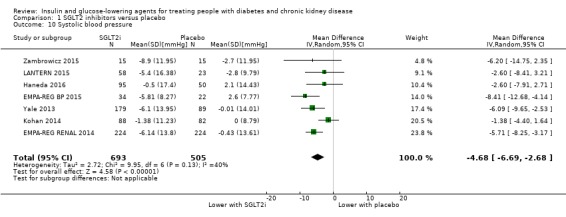

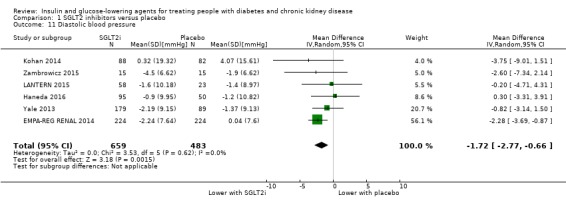

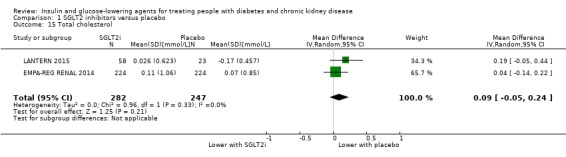

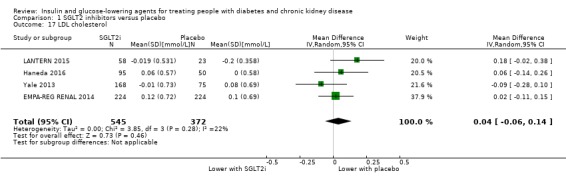

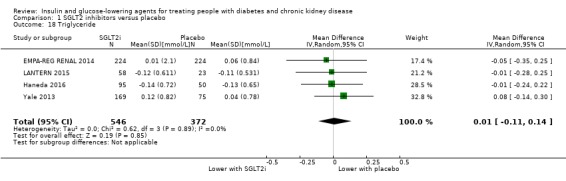

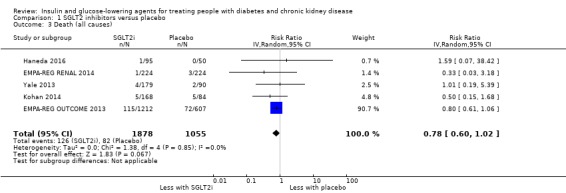

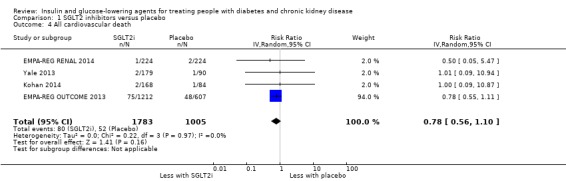

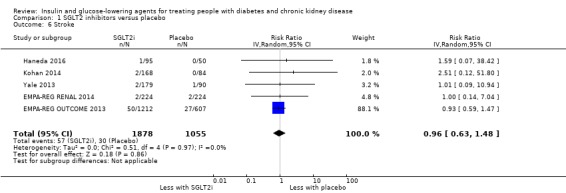

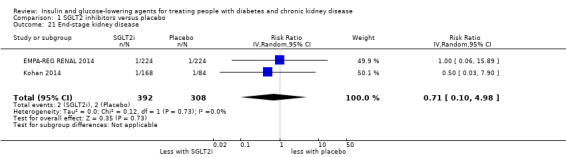

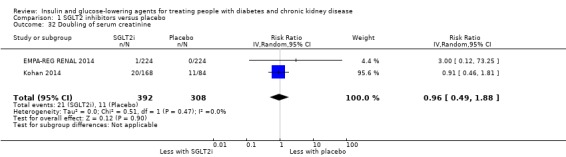

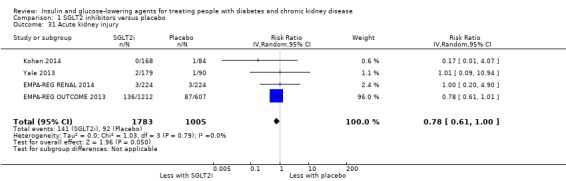

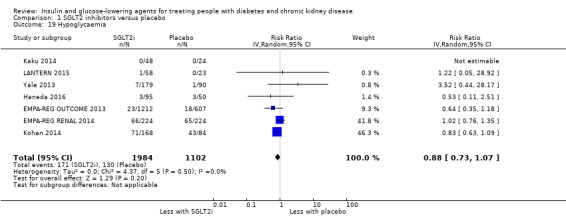

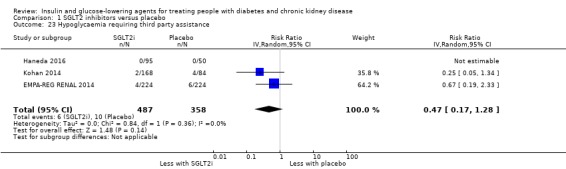

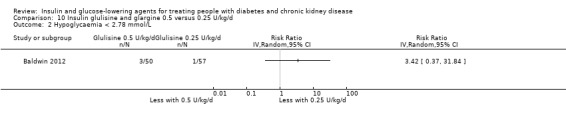

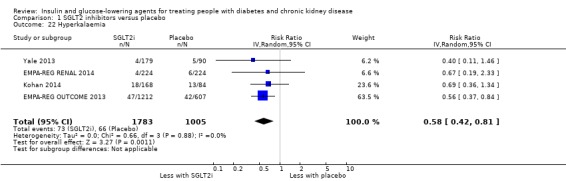

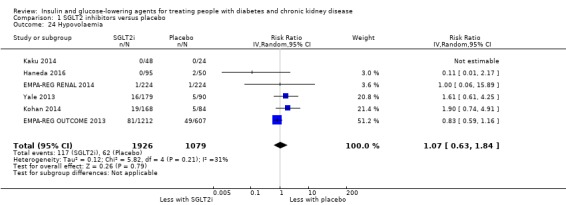

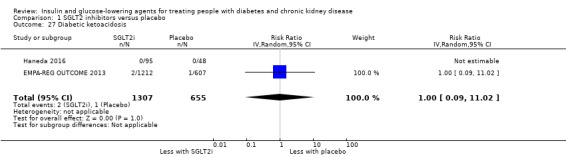

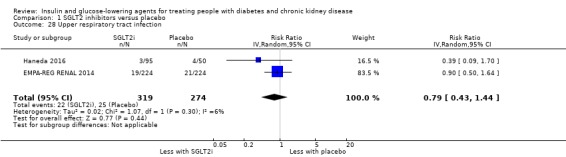

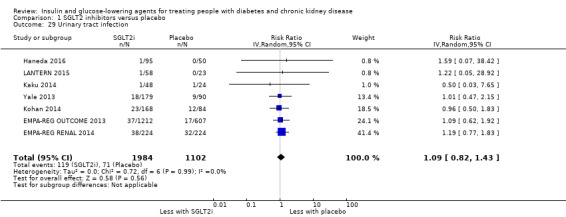

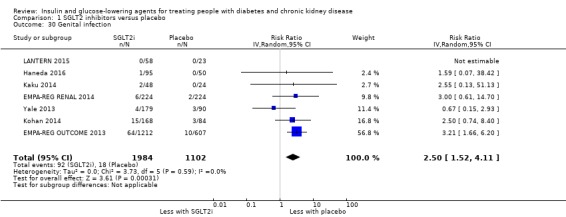

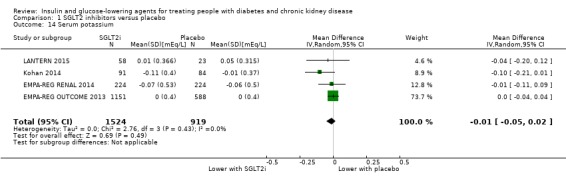

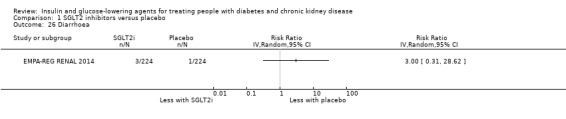

Compared to placebo, SGLT2 inhibitors probably reduce HbA1c (7 studies, 1092 participants: MD ‐0.29%, ‐0.38 to ‐0.19 (‐3.2 mmol/mol, ‐4.2 to ‐2.2); I2 = 0%), fasting blood glucose (FBG) (5 studies, 855 participants: MD ‐0.48 mmol/L, ‐0.78 to ‐0.19; I2 = 0%), systolic blood pressure (BP) (7 studies, 1198 participants: MD ‐4.68 mmHg, ‐6.69 to ‐2.68; I2 = 40%), diastolic BP (6 studies, 1142 participants: MD ‐1.72 mmHg, ‐2.77 to ‐0.66; I2 = 0%), heart failure (3 studies, 2519 participants: RR 0.59, 0.41 to 0.87; I2 = 0%), and hyperkalaemia (4 studies, 2788 participants: RR 0.58, 0.42 to 0.81; I2 = 0%); but probably increase genital infections (7 studies, 3086 participants: RR 2.50, 1.52 to 4.11; I2 = 0%), and creatinine (4 studies, 848 participants: MD 3.82 μmol/L, 1.45 to 6.19; I2 = 16%) (all effects of moderate certainty evidence). SGLT2 inhibitors may reduce weight (5 studies, 1029 participants: MD ‐1.41 kg, ‐1.8 to ‐1.02; I2 = 28%) and albuminuria (MD ‐8.14 mg/mmol creatinine, ‐14.51 to ‐1.77; I2 = 11%; low certainty evidence). SGLT2 inhibitors may have little or no effect on the risk of cardiovascular death, hypoglycaemia, acute kidney injury (AKI), and urinary tract infection (low certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether SGLT2 inhibitors have any effect on death, end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD), hypovolaemia, fractures, diabetic ketoacidosis, or discontinuation due to adverse effects (very low certainty evidence).

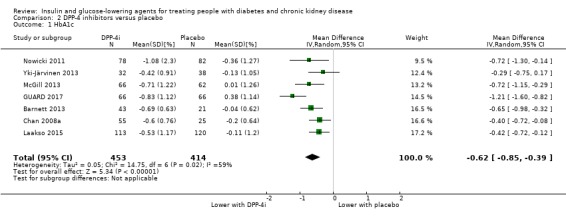

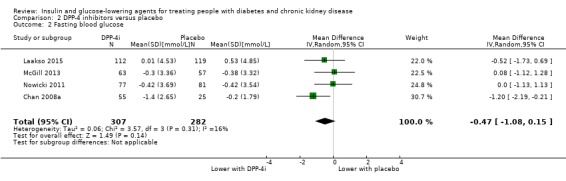

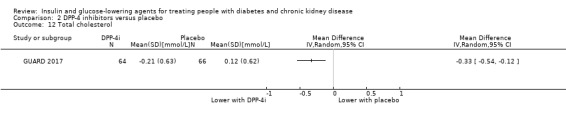

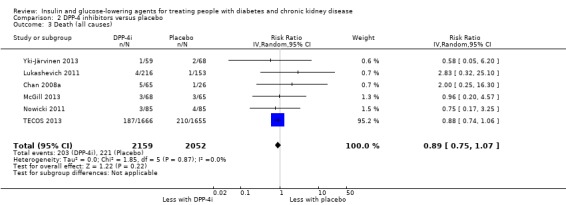

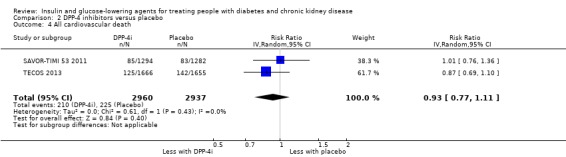

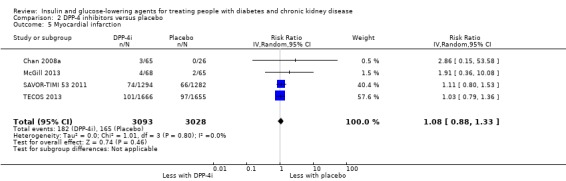

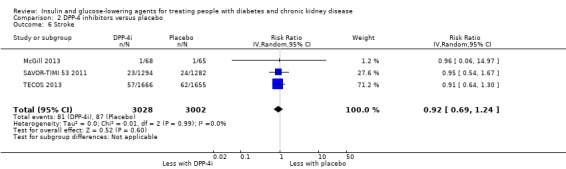

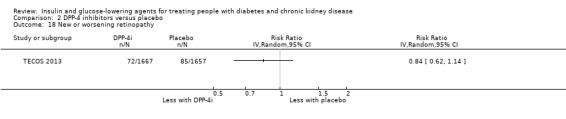

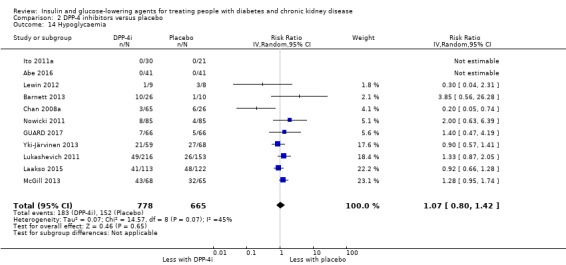

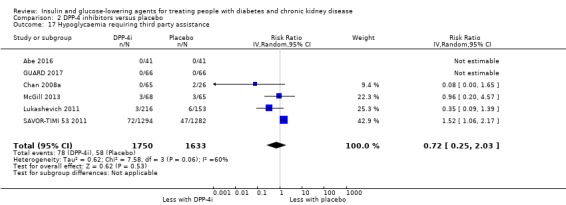

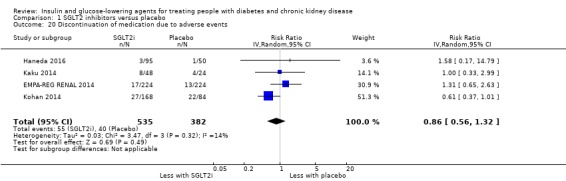

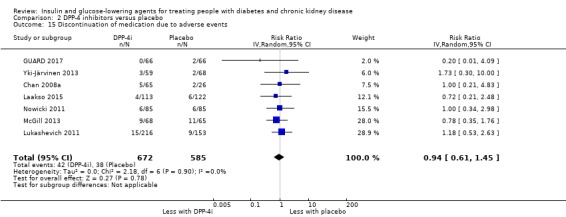

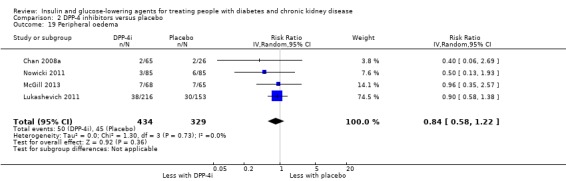

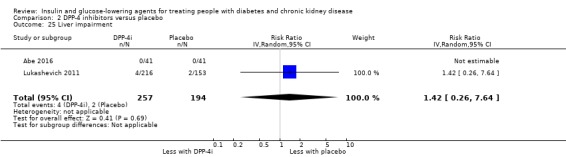

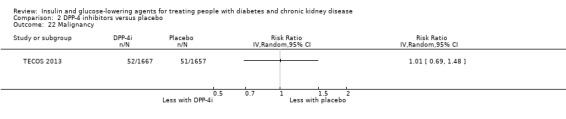

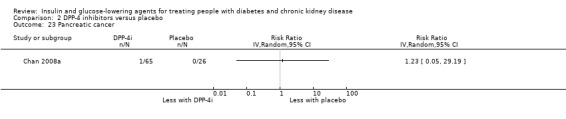

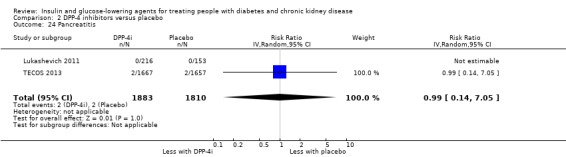

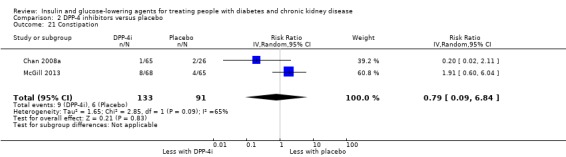

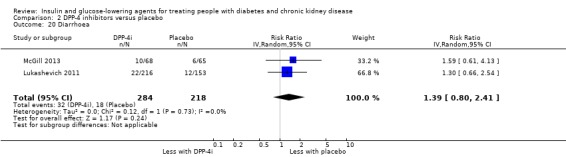

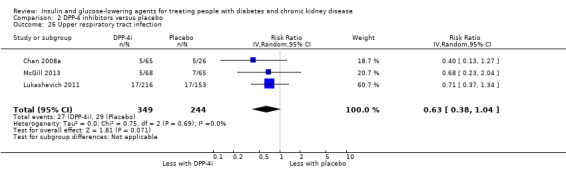

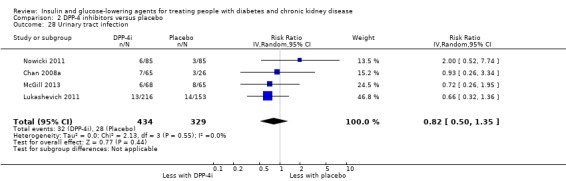

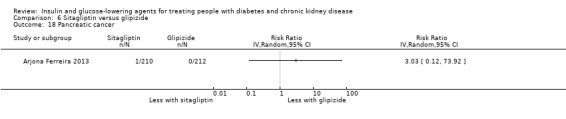

Compared to placebo, DPP‐4 inhibitors may reduce HbA1c (7 studies, 867 participants: MD ‐0.62%, ‐0.85 to ‐0.39 (‐6.8 mmol/mol, ‐9.3 to ‐4.3); I2 = 59%) but may have little or no effect on FBG (low certainty evidence). DPP‐4 inhibitors probably have little or no effect on cardiovascular death (2 studies, 5897 participants: RR 0.93, 0.77 to 1.11; I2 = 0%) and weight (2 studies, 210 participants: MD 0.16 kg, ‐0.58 to 0.90; I2 = 29%; moderate certainty evidence). Compared to placebo, DPP‐4 inhibitors may have little or no effect on heart failure, upper respiratory tract infections, and liver impairment (low certainty evidence). Compared to placebo, it is uncertain whether DPP‐4 inhibitors have any effect on eGFR, hypoglycaemia, pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, or discontinuation due to adverse effects (very low certainty evidence).

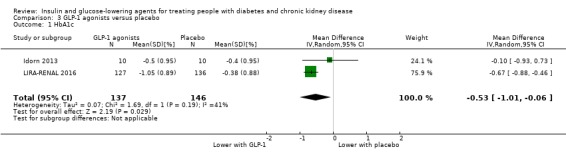

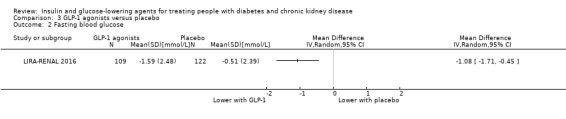

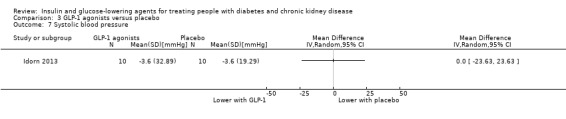

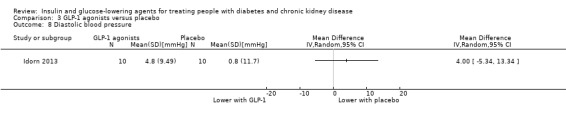

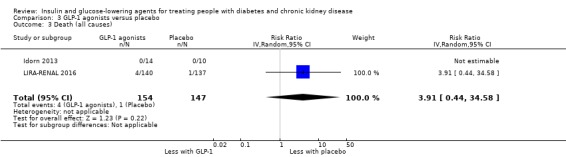

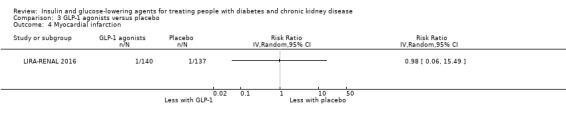

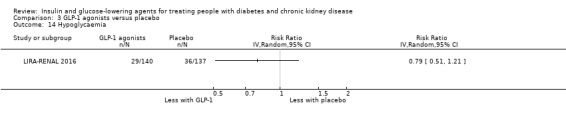

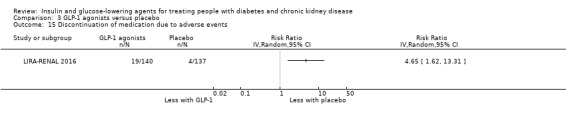

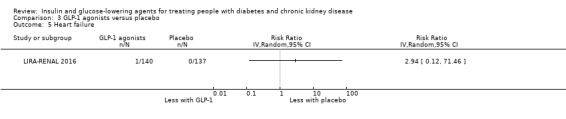

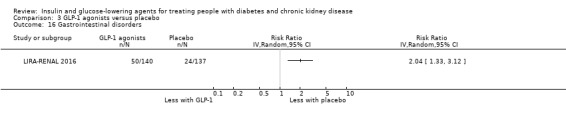

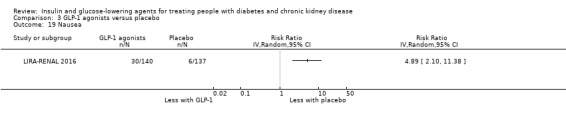

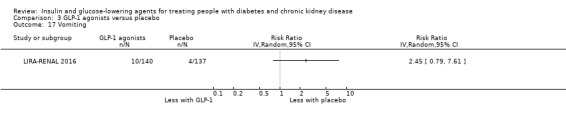

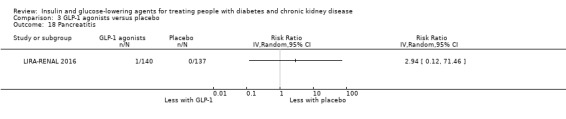

Compared to placebo, GLP‐1 agonists probably reduce HbA1c (7 studies, 867 participants: MD ‐0.53%, ‐1.01 to ‐0.06 (‐5.8 mmol/mol, ‐11.0 to ‐0.7); I2 = 41%; moderate certainty evidence) and may reduce weight (low certainty evidence). GLP‐1 agonists may have little or no effect on eGFR, hypoglycaemia, or discontinuation due to adverse effects (low certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether GLP‐1 agonists reduce FBG, increase gastrointestinal symptoms, or affect the risk of pancreatitis (very low certainty evidence).

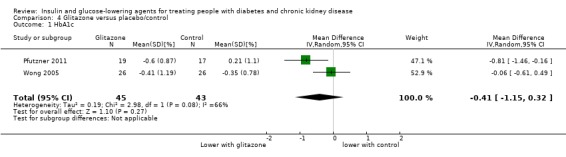

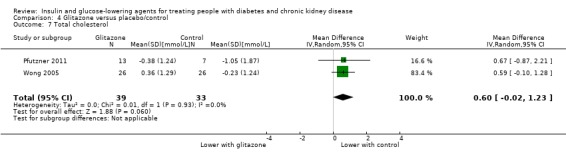

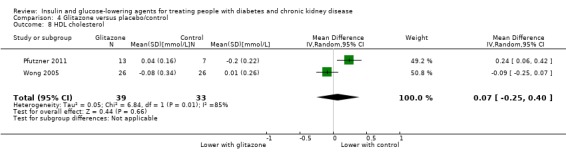

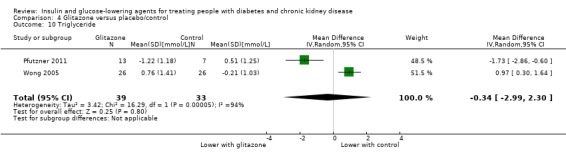

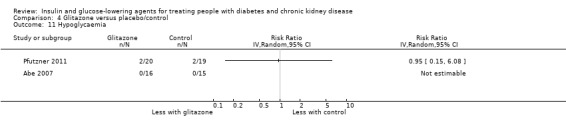

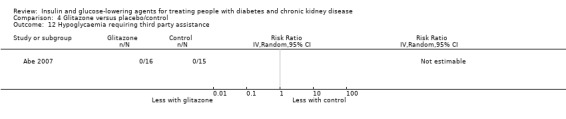

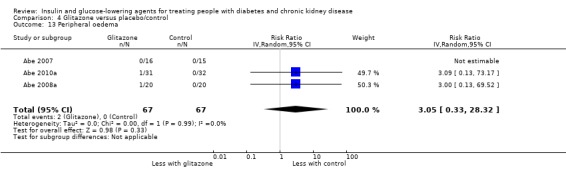

Compared to placebo, it is uncertain whether glitazones have any effect on HbA1c, FBG, death, weight, and risk of hypoglycaemia (very low certainty evidence).

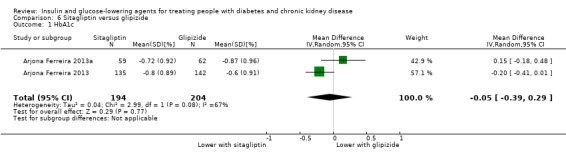

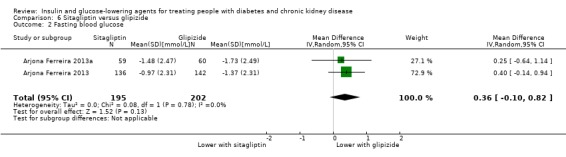

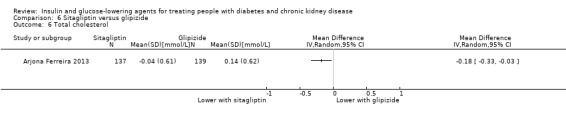

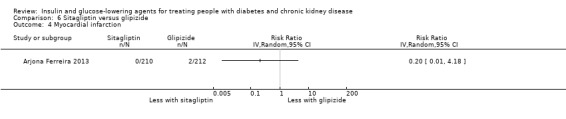

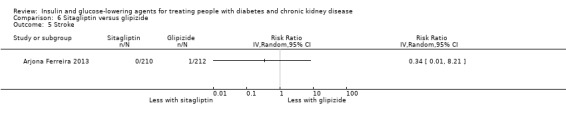

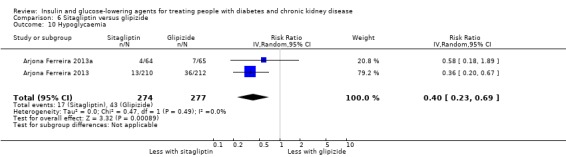

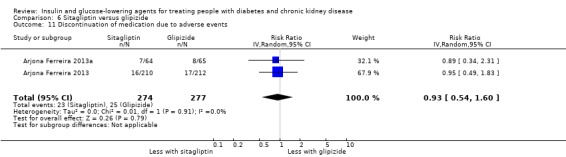

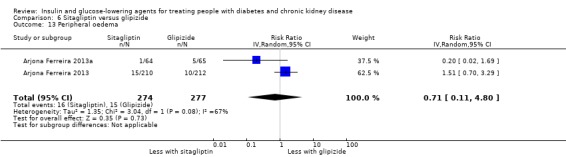

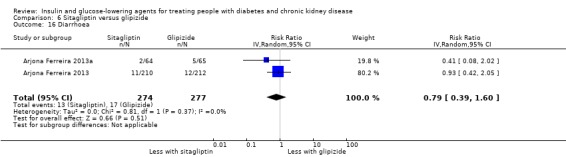

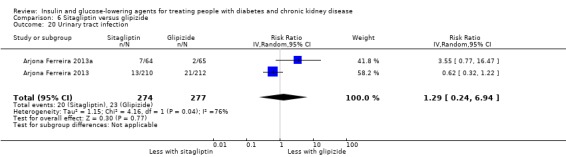

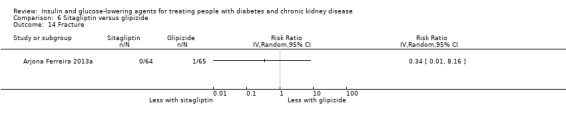

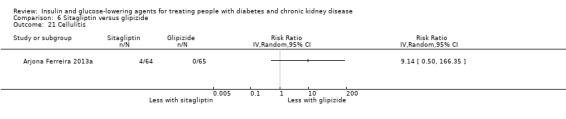

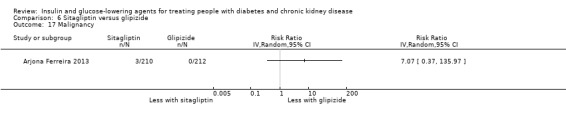

Compared to glipizide, sitagliptin probably reduces hypoglycaemia (2 studies, 551 participants: RR 0.40, 0.23 to 0.69; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence). Compared to glipizide, sitagliptin may have had little or no effect on HbA1c, FBG, weight, and eGFR (low certainty evidence). Compared to glipizide, it is uncertain if sitagliptin has any effect on death or discontinuation due to adverse effects (very low certainty).

For types, dosages or modes of administration of insulin and other head‐to‐head comparisons only individual studies were available so no conclusions could be made.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence concerning the efficacy and safety of glucose‐lowering agents in diabetes and CKD is limited. SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‐1 agonists are probably efficacious for glucose‐lowering and DPP‐4 inhibitors may be efficacious for glucose‐lowering. Additionally, SGLT2 inhibitors probably reduce BP, heart failure, and hyperkalaemia but increase genital infections, and slightly increase creatinine. The safety profile for GLP‐1 agonists is uncertain. No further conclusions could be made for the other classes of glucose‐lowering agents including insulin. More high quality studies are required to help guide therapeutic choice for glucose‐lowering in diabetes and CKD.

Plain language summary

Glucose‐lowering medications to treat diabetes and chronic kidney disease

What is the issue? Diabetes is the commonest cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Due to decreased kidney function and changes in the clearance of medications and glucose, treating people with diabetes and CKD is challenging. There is an increased risk of hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar). However, most glucose‐lowering medications have been studied in people with near normal kidney function. The aim of this review is to determine the effectiveness and safety of glucose‐lowering medication in people with diabetes and CKD.

What did we do? We looked at studies comparing different medications with each other or to no medications in people with diabetes and CKD.

What did we find?

We included 44 studies involving 13,036 people. Most studies compared different medication types ‐ sodium glucose co‐transporter‐2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitors, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) agonists, and glitazones to no treatment. Two studies compared the medications sitagliptin to glipizide.

SGLT2 inhibitors probably reduce glucose levels, blood pressure, heart failure and high potassium levels but increase genital infections and slightly reduce kidney function. SGLT2 inhibitors may reduce weight. Their effect on the risk of death, hypoglycaemia, acute kidney injury, urinary tract infection, end‐stage kidney disease, low blood volume, bone fractures, diabetic ketoacidosis is uncertain.

DPP‐4 inhibitors may reduce glucose levels. Their effect on the risk of death due to heart attacks and strokes, heart failure, upper respiratory tract infections, liver problems, kidney function, hypoglycaemia, pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer is uncertain.

GLP‐1 agonists probably reduce glucose levels and may reduce weight. Their effect on kidney function, hypoglycaemia, gastrointestinal symptoms and pancreatitis is uncertain.

Compared to glipizide, sitagliptin probably has a lower risk of hypoglycaemia.

No conclusions could be made regarding other glucose‐lowering medications when compared to another medication or no treatment because of the lack of studies.

Conclusions

Evidence concerning the efficacy and safety of glucose‐lowering agents for people with diabetes and CKD is limited. SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‐1 agonists are probably efficacious for lowering glucose levels. Other potential effects of SGLT2 inhibitors include lower BP, lower potassium levels and a reduced risk of heart failure but an increased risk of genital infections. The safety of GLP‐1 agonists is uncertain.

The benefits and safety of other classes of glucose‐lowering agents are uncertain.

More studies are required to help guide which glucose‐lowering medications are most suitable in people with both diabetes and CKD.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetes is a highly prevalent condition, affecting 8.2% of adults or 382 million people globally. The incidence is increasing with an estimated global prevalence of 592 million people by 2035 (IDF 2013).

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as the sustained loss of kidney function over an extended period of time or the presence of albuminuria or other markers of kidney damage, has been estimated to affect 16% of the general population in screening studies (Chadban 2003; Coresh 2003; Perkovic 2007). CKD prevalence is increasing in the USA and other countries (Chadban 2003). Progression to end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) leads to significant morbidity and mortality with people requiring permanent renal replacement therapy (RRT) either as dialysis or kidney transplantation. The prognosis of people with ESKD is poor, with a 6% to 20% annual mortality rate for all people on dialysis (Collins 2008).

Diabetes is the commonest cause of CKD, and accounts for up to 50% of people who develop ESKD (Collins 2007; ANZDATA 2008). The increasing incidence of diabetes is a likely contributor to the escalating incidence of CKD, with one third of the increase in ESKD cases from 1978 to 1991 in the USA attributable to diabetes. Diabetes is also a common comorbidity in people with non‐diabetic kidney disease (ANZDATA 2008). Both diabetes and CKD are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, with the risk being additive for people with both conditions, and increasing with CKD progression (Radbill 2008).

Observational studies reporting on the relationship between glucose control and clinical outcomes in diabetes and CKD are conflicting with some showing a clear positive association (Morioka 2001; Oomichi 2006; Wu 1997), others showing no relationship (Shurraw 2010; Williams 2006), and some a U‐shaped association (Shurraw 2011). This discrepancy results from inherent limitations of observational studies, differences in the characteristics of study populations, and differences in glucose control measurements. Additionally, most considered glucose control as a single predictor of clinical outcomes rather than a component of a multifaceted treatment regimen including the control of blood pressure (BP), cholesterol and weight (Feldt‐Rasmussen 2006).

Description of the intervention

Pharmacological interventions used to improve glucose control include both oral glucose‐lowering agents and injectables including glucose‐like peptide type 1 analogues (GLP‐1) and insulin. In type 2 diabetes, these agents are used as single or combination therapy, with pharmacological agent choice and combination tailored to the patient being treated. Pharmacotherapy is typically introduced in a stepwise fashion beginning with oral agents followed by the introduction of injectables such as GLP‐1 analogues and insulin (ADA 2017; Inzucchi 2012). In type 1 diabetes, insulins are the mainstay of therapy (ADA 2017).

Apart from insulins, the choice of available pharmacological interventions to lower high glucose levels has expanded rapidly over the past decade. Commonly prescribed classes of glucose‐lowering medications include biguanides, thiazolidinediones (glitazones), second generation sulphonylureas, ɑ‐glucosidase inhibitors, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogues, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitors, sodium glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, and insulins. Newer or emerging classes of glucose‐lowering medications are dual peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor (PPAR) agonists, amylin analogues, bromocriptine and GPR40 or free fatty acid receptor 1 (FFAR1) agonists.

To date, the efficacy and safety of these therapies have not been well documented in people with diabetes and CKD.

How the intervention might work

Large scale studies conducted in people with diabetes and preserved kidney function provide evidence that intensive glucose‐lowering reduces the incidence and progression of microvascular outcomes (ADVANCE Group 2008; CONTROL Group 2009; DCCT Group 1993; DCCT Group 1995; Duckworth 2009; Holman 2008; Ismail‐Beigi 2010Nathan 2005; UKPDS 33 1998; UKPDS 34 1998). Additionally, several large studies and meta‐analysis have shown that intensive glucose‐lowering reduces the progression of kidney disease (ADVANCE Group 2008; DCCT Group 1995; Duckworth 2009; Ismail‐Beigi 2010; Levin 2000; Ohkubo 1995; UKPDS 33 1998; Zoungas 2017), with both the ADVANCE (ADVANCE Group 2008) and ACCORD (Ismail‐Beigi 2010) studies showing that progression of both microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria were reduced, and the ADVANCE study showing a reduction in the development of ESKD (Perkovic 2013).

Given that diabetes is the leading cause of CKD worldwide, optimal glucose control in people with kidney disease has been proposed to reduce adverse kidney and cardiovascular events. However, existing studies have mainly studied participants without CKD. Consequently, it is unknown whether these benefits would be observed in people with established CKD, especially with more advanced CKD (stages 3 to 5).

Why it is important to do this review

Achieving near normal glucose levels in people with diabetes and CKD poses a challenging task. The development and progression of CKD results in glucometabolic changes (increased hepatic glucose output, reduced glucose disposal and greater insulin resistance), that increase blood glucose levels. Simultaneously, reduced insulin and drug clearance increase the risk of hypoglycaemia (Moen 2009). Moreover, the commencement of dialysis improves insulin sensitivity (Kobayashi 2000) and increases the risk of hypoglycaemia (Jackson 2000; Loipl 2005).

Past studies of intensive glucose control have failed to include meaningful numbers of people with CKD (that is, reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR)) with much of the evidence coming from studies involving people with diabetes in the general population or those with earlier stages of kidney disease. Based on currently available evidence, international guidelines (Chadban 2010; KDOQI 2012) continue to advocate the achievement of optimal glucose control as part of a comprehensive treatment approach for people with diabetes and CKD.

Given the current uncertainty regarding the effectiveness and safety of contemporary glucose‐lowering strategies, a critical review is urgently needed to inform clinical practice and highlight areas requiring further research.

Originally, this review was to be part of a larger review examining glucose‐lowering therapies in CKD and kidney transplantation ("Glucose‐lowering therapies for chronic kidney disease and kidney transplantation") (Jun 2012). However, as the specific challenges of managing blood glucose levels were deemed different in kidney transplant recipients compared with other people with CKD, we decided to examine the efficacy and safety of contemporary glucose‐lowering in these different populations in separate reviews. This review examined glucose‐lowering in people with diabetes and CKD. The accompanying review "Glucose‐lowering agents for treating pre‐existing and new onset diabetes in kidney transplant recipients" (Lo 2017) was published in February 2017.

Objectives

To examine the efficacy and safety of insulin and other pharmacological interventions for lowering glucose levels in people with diabetes and CKD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

Quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods)

Cross‐over studies (first phase considered only).

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults and children with diabetes and CKD. The definition of CKD will be limited to an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) GFR stages 3 to 5 (KDIGO 2011; KDOQI 2002).

Exclusion criteria

Transplant recipients (kidney, pancreas and islet cell).

Types of interventions

Head‐to‐head comparisons of active regimens (including comparisons of monotherapy or combination therapy with two or more pharmacological glucose‐lowering interventions, comparisons of different doses and durations of the same intervention) or active regimen compared with placebo, control or standard care.

Metformin

Insulin

Sulphonylurea (excluding first generation)

Glinides

Glitazones

ɑ‐glucosidase inhibitors

Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 agonists

DPP‐4 inhibitors

SGLT2 inhibitors

Amylin analogues

Bromocriptine.

Types of outcome measures

Efficacy

Safety.

Primary outcomes

Glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)

Fasting blood glucose (FBG)

Secondary outcomes

Kidney function (creatinine, estimated GFR (eGFR), albuminuria)

Systolic and diastolic BP

Lipids (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglyceride)

Body weight

Death (all causes)

Macrovascular events (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke)

Microvascular events (new or worsening kidney disease, or retinopathy)

-

Safety

Hypoglycaemia

Discontinuation of medication due to adverse events

Other adverse events as described by the authors.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register to 12 February 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Specialised Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Hand searching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of all possible studies relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable. However, studies and reviews that might include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts, and if necessary the full text, of these studies to determine which satisfied the inclusion criteria. Two other independent authors assessed studies written in Chinese.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms for English studies, and two other authors independently extracted data for relevant studies in Chinese. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and relevant data from each report were used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancies between published versions were highlighted. The following data were extracted ‐ participant characteristics (including demographic information and comorbidities), interventions (including concomitant medications and interventions), and the previously specified primary and secondary outcomes (Types of outcome measures). Any disagreements were resolved by a fifth author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by four authors (two for studies in English and two for studies in Chinese) using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Any disagreements were resolved by a fifth author.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (all‐cause mortality, macrovascular events, microvascular events) results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (HbA1c, FBG, BP, lipids, body weight), the mean difference (MD) was expressed, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used.

For adverse events, results were expressed as post treatment absolute risk differences.

Unit of analysis issues

All units for analysis were converted to SI units and % for HbA1c.

Dealing with missing data

Any additional information required from the original authors were requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing corresponding author) and any relevant information obtained was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened and randomised people as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol populations were carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was first assessed by visual inspection of the forest plot before being analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003).

The interpretation of I2 values is as follows:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2; Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

If sufficient RCTs were identified, funnel plots were used to assess for the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model but the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers. Where data were reported in insufficient detail to allow meta‐analysis and further information was not forthcoming from trialists, these outcomes were tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques and where possible the risk difference (RD) with 95% CI was calculated. If adequate data were available then the number of persons needed to treat to avoid one cardiovascular death was calculated.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity according to the following characteristics:

Sex

Age

History of cardiac disease

Glucose‐lowering agent and dose of glucose‐lowering agent

Concomitant glucose‐lowering agents (such as insulin)

Dose and duration of concomitant glucose‐lowering agent used (such as insulin)

Concomitant medications (such as aspirin or BP medications)

Baseline HbA1c level

Type 1 diabetes versus type 2 diabetes

CKD stages (3, 4 and 5)

Primary cause of kidney disease (diabetes versus others).

Adverse effects were tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques. Where possible, the risk difference with 95% CI was calculated for each adverse effect, either compared to no treatment or to another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses explored the influence of the following factors on effect size:

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias, as specified

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

'Summary of findings' tables

The main results of the review are presented in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). The following outcomes are presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

HbA1c

Fasting glucose

eGFR

Weight

Death (all causes)

All cardiovascular death

Hypoglycaemia

Discontinuation of medications due to adverse events.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

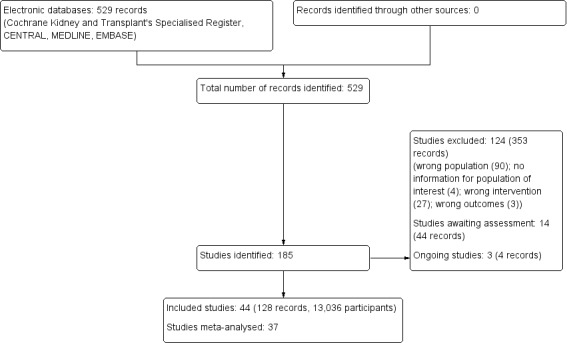

Results of the search

The search identified 185 studies (529 records). Following assessment of titles, abstracts and full‐text articles, we included 44 studies (128 records) and excluded 124 studies (353 records). Fourteen studies are awaiting assessment (mostly awaiting data from the authors), and three studies are ongoing (see Figure 1); these will be included in a future update of this review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 44 studies (13,036 participants) for qualitative synthesis, however after contact with authors, only 37 studies had adequate data to be quantitatively synthesised for meta‐analyses.

Nine studies compared SGLT2 inhibitors to placebo in people with an eGFR 15 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Two studies compared dapagliflozin to placebo (Kaku 2014; Kohan 2014); three studies compared empagliflozin to placebo (EMPA‐REG BP 2015; EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013; EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014), one study compared luseogliflozin to placebo (Haneda 2016), one study compared canagliflozin to placebo (Yale 2013), and one study compared ipragliflozin to placebo (LANTERN 2015). Additionally, one study compared a dual SGLT1 and 2 inhibitor, LX4211 or sotagliflozin to placebo (Zambrowicz 2015). All studies could be included in the meta‐analysis.

Thirteen studies compared DPP‐4 inhibitors to placebo in people with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those receiving dialysis. Three studies compared saxagliptin to placebo (Abe 2016; Nowicki 2011; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011), five studies compared linagliptin to placebo (Barnett 2013; Laakso 2015; Lewin 2012; McGill 2013; Yki‐Järvinen 2013), two studies compared sitagliptin to placebo (Chan 2008a; TECOS 2013), two studies compared vildagliptin to placebo ( Ito 2011a; Lukashevich 2011), and one study compared gemigliptin to placebo (GUARD 2017). All studies could be included in the meta‐analysis.

Two studies compared GLP‐1 agonists (liraglutide) to placebo (Idorn 2013; LIRA‐RENAL 2016) in people with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those receiving dialysis. All studies were included in the meta‐analysis.

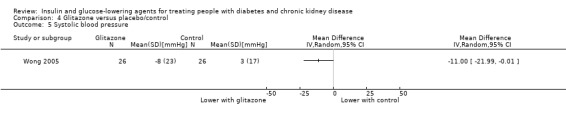

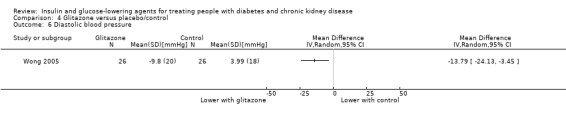

Seven parallel studies and 1 cross‐over study compared glitazones to placebo. The majority of participants were receiving HD but one study had people with an eGFR 15 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Jin 2007). Six studies compared pioglitazone to placebo (Abe 2007; Abe 2008a; Abe 2010a; Jin 2007; Nakamura 2001; Pfutzner 2011), one study compared rosiglitazone to placebo (Wong 2005), and one cross‐over study compared troglitazone to placebo (Nakamura 2001). Mohideen 2005 and Nakamura 2001 could not be included in the meta‐analysis. It should be noted that troglitazone was withdrawn from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2000 due to the risk of liver failure and hepatotoxicity (FDA 2000).

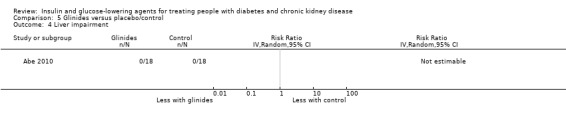

One study compared glinides (mitiglinide) to control (not receiving mitiglinide) in people receiving HD (Abe 2010).

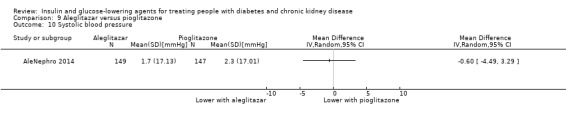

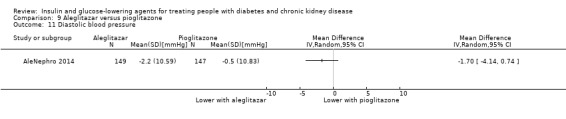

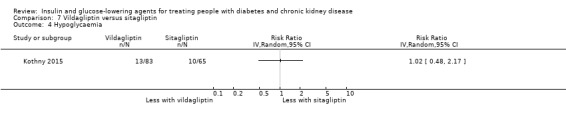

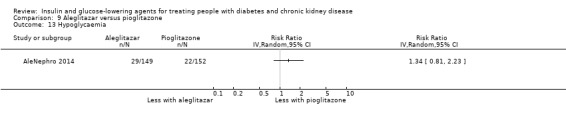

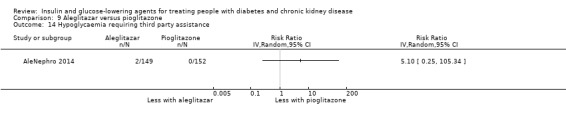

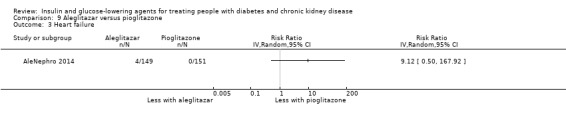

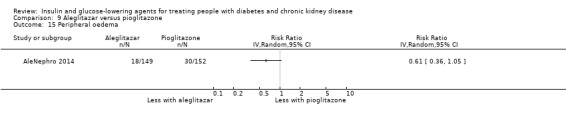

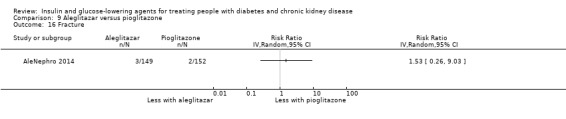

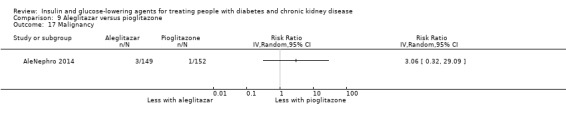

Seven studies compared one glucose‐lowering agent to another. Two studies compared sitagliptin to glipizide in people with an eGFR < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those receiving dialysis (Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a), one study compared vildagliptin to sitagliptin in those with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those receiving HD (Kothny 2015), one study compared albiglutide to sitagliptin in those with an eGFR 15 to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Leiter 2014), one study compared sitagliptin to insulin in people with an eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those on HD (Bellante 2016), and one study compared linagliptin to voglibose in those receiving HD (Mori 2016). Additionally, one study compared glitazars (aleglitazar) to pioglitazone (AleNephro 2014) in people with an eGFR 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Only Arjona Ferreira 2013 and Arjona Ferreira 2013a could be included in the meta‐analyses. One should note that the development of aleglitazar was halted by Roche in 2013 due to concerns about its safety and efficacy (ALECARDIO 2013).

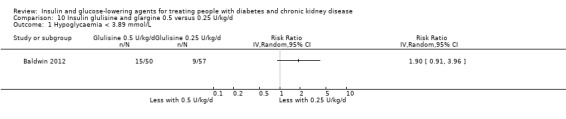

Four studies compared different type, dosages, or modes of administration of insulin. One study compared 0.25 U/kg to 0.5 U/kg of insulin glulisine and glargine in those with an eGFR ≤ 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Baldwin 2012), and one cross‐over study compared insulin lispro to regular insulin in those with a GFR 50 to 60 mL/min (Ruggenenti 2003a). One parallel study (Diez 1987) and one cross‐over study (Scarpioni 1994) compared intraperitoneal (IP) to subcutaneous (SC) insulin in those receiving PD. None of the studies could be included in the meta‐analysis due to heterogeneity in the intervention or presentation of the results.

Excluded studies

We excluded 124 studies due to the following reasons:

Wrong study population: 90 studies

Inadequate information (data for people with an eGFR < 60 was not available from authors): 4 studies

Wrong intervention: 27 studies

No relevant outcomes: 3 studies

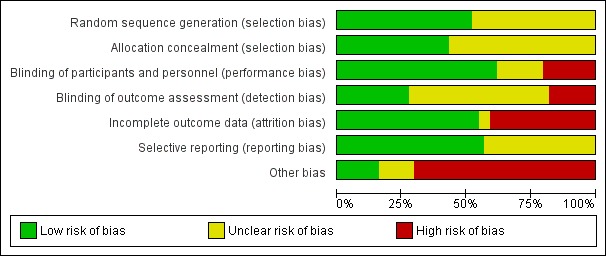

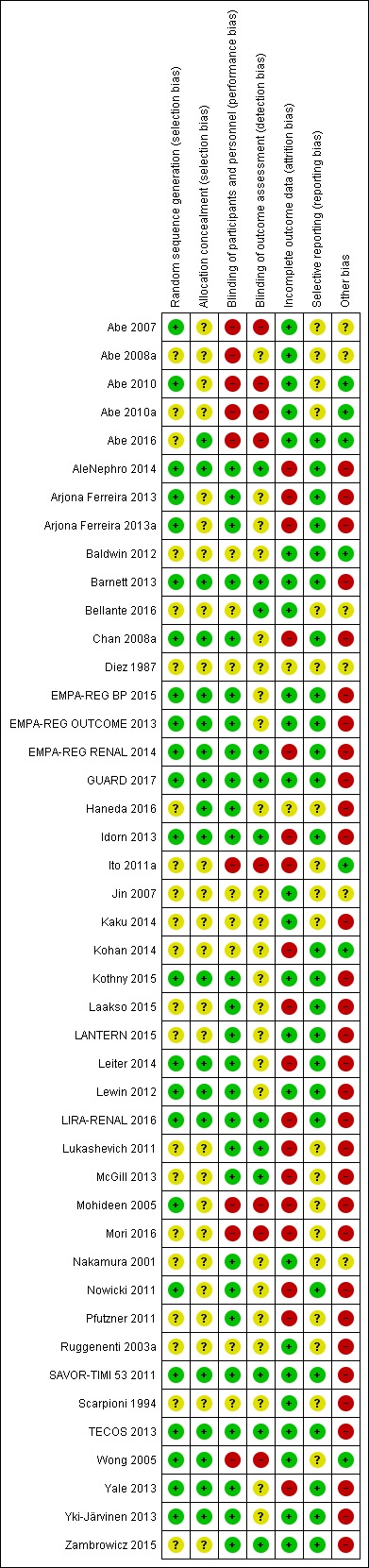

Risk of bias in included studies

Summaries of risk of bias are reported in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Random sequence generation was judged to be at low risk of bias in 23 studies (Abe 2007; Abe 2010; AleNephro 2014; Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a; Barnett 2013; Chan 2008a; EMPA‐REG BP 2015; EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013; EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; GUARD 2017; Idorn 2013; Kothny 2015; Leiter 2014; Lewin 2012; LIRA‐RENAL 2016; Mohideen 2005; Nowicki 2011; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011; TECOS 2013; Wong 2005; Yale 2013; Yki‐Järvinen 2013) and unclear in 21 studies (Abe 2008a; Abe 2010a; Abe 2016; Baldwin 2012; Bellante 2016; Diez 1987; Haneda 2016; Ito 2011a; Jin 2007; Kaku 2014; Kohan 2014; Laakso 2015; LANTERN 2015; Lukashevich 2011; McGill 2013; Mori 2016; Nakamura 2001; Pfutzner 2011; Ruggenenti 2003a; Scarpioni 1994; Zambrowicz 2015).

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was judged to be at low risk of bias in 19 studies (Abe 2016; AleNephro 2014; Barnett 2013; Chan 2008a; EMPA‐REG BP 2015; EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013; EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; GUARD 2017; Haneda 2016; Idorn 2013; Kothny 2015; Leiter 2014; Lewin 2012; LIRA‐RENAL 2016; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011; TECOS 2013; Wong 2005; Yale 2013; Yki‐Järvinen 2013) and unclear in 25 studies (Abe 2007; Abe 2008a; Abe 2010; AleNephro 2014; Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a; Baldwin 2012; Bellante 2016; Diez 1987; Ito 2011a; Jin 2007; Kaku 2014; Kohan 2014; Laakso 2015; LANTERN 2015; Lukashevich 2011; McGill 2013; Mohideen 2005; Mori 2016; Nakamura 2001; Nowicki 2011; Pfutzner 2011; Ruggenenti 2003a; Scarpioni 1994; Zambrowicz 2015).

Blinding

Performance bias

Performance bias (blinding of participants and investigators) was judged to be at low risk of bias in 27 studies (AleNephro 2014; Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a; Barnett 2013; Chan 2008a; EMPA‐REG BP 2015; EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013; EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; GUARD 2017; Haneda 2016; Idorn 2013; Kothny 2015; Laakso 2015; LANTERN 2015; Leiter 2014; Lewin 2012; LIRA‐RENAL 2016; Lukashevich 2011; McGill 2013; Nakamura 2001; Nowicki 2011; Pfutzner 2011; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011; TECOS 2013; Yale 2013; Yki‐Järvinen 2013; Zambrowicz 2015) and at high risk of bias in 9 studies (Abe 2007; Abe 2008a; Abe 2010; Abe 2010a; Abe 2016; Ito 2011a; Mohideen 2005; Mori 2016; Wong 2005). The risk of bias was unclear in eight studies (Baldwin 2012; Bellante 2016; Diez 1987; Jin 2007; Kaku 2014; Kohan 2014; Ruggenenti 2003a; Scarpioni 1994).

Detection bias

Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors) was judged to be at low risk of bias in 12 studies (AleNephro 2014; Barnett 2013; Bellante 2016; EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; GUARD 2017; Idorn 2013; Lukashevich 2011; LIRA‐RENAL 2016; McGill 2013; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011; TECOS 2013; Zambrowicz 2015) and at high risk of bias in eight studies (Abe 2007; Abe 2010; Abe 2010a; Abe 2016; Ito 2011a; Mohideen 2005; Mori 2016; Wong 2005). The risk of bias was unclear in 24 studies (Abe 2008a; Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a; Baldwin 2012; Chan 2008a; Diez 1987; EMPA‐REG BP 2015; EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013; Haneda 2016; Jin 2007; Kaku 2014; Kohan 2014; Kothny 2015; Laakso 2015; LANTERN 2015; Leiter 2014; Lewin 2012; Nakamura 2001; Nowicki 2011; Pfutzner 2011; Ruggenenti 2003a; Scarpioni 1994; Yale 2013; Yki‐Järvinen 2013).

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition bias was judged to be at low risk of bias in 24 studies (Abe 2007; Abe 2008a; Abe 2010; Abe 2010a; Abe 2016; Baldwin 2012; Barnett 2013; Bellante 2016; EMPA‐REG BP 2015; EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013; GUARD 2017; Jin 2007; Kaku 2014; Kothny 2015; LANTERN 2015; Lewin 2012; Nakamura 2001; Ruggenenti 2003a; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011; Scarpioni 1994; TECOS 2013; Wong 2005; Yki‐Järvinen 2013; Zambrowicz 2015) and at high risk of bias in 18 studies (AleNephro 2014; Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a; Chan 2008a; EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; Idorn 2013; Ito 2011a; Kohan 2014; Laakso 2015; Leiter 2014; LIRA‐RENAL 2016; Lukashevich 2011; McGill 2013; Mohideen 2005; Mori 2016; Nowicki 2011; Pfutzner 2011; Yale 2013). The risk of bias was unclear in two studies (Diez 1987; Haneda 2016).

Selective reporting

Reporting bias was judged to be at low risk of bias in 25 studies (Abe 2016; AleNephro 2014; Arjona Ferreira 2013; Baldwin 2012; Barnett 2013; Chan 2008a; EMPA‐REG BP 2015; EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013; EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; GUARD 2017; Idorn 2013; Kaku 2014; Kohan 2014; Kothny 2015; Laakso 2015; LANTERN 2015; Leiter 2014; Lewin 2012; LIRA‐RENAL 2016; Nowicki 2011; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011; TECOS 2013; Yale 2013; Yki‐Järvinen 2013; Zambrowicz 2015) and was unclear in 19 studies (Abe 2007; Abe 2008a; Abe 2010; Abe 2010a; Arjona Ferreira 2013a; Bellante 2016; Diez 1987; Haneda 2016; Ito 2011a; Jin 2007; Lukashevich 2011; McGill 2013; Mohideen 2005; Mori 2016; Nakamura 2001; Pfutzner 2011; Ruggenenti 2003a; Scarpioni 1994; Wong 2005).

Other potential sources of bias

Thirty‐one studies had a high risk of funding bias (AleNephro 2014; Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a; Barnett 2013; Chan 2008a; EMPA‐REG BP 2015; EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013; EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; GUARD 2017; Haneda 2016; Idorn 2013; Kaku 2014; Kothny 2015; Laakso 2015; LANTERN 2015; Leiter 2014; Lewin 2012; LIRA‐RENAL 2016; Lukashevich 2011; McGill 2013; Mohideen 2005; Mori 2016; Nowicki 2011; Pfutzner 2011; Ruggenenti 2003a; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011; Scarpioni 1994; TECOS 2013; Yale 2013; Yki‐Järvinen 2013; Zambrowicz 2015) due to the studies being supported by pharmaceutical companies and the majority of the authors receiving funding or being employees of these companies. Six studies did not report their funding source and conflicts of interest (Abe 2007; Abe 2008a; Bellante 2016; Diez 1987; Jin 2007; Nakamura 2001) and seven studies had a low risk of funding bias (Abe 2010; Abe 2010a; Abe 2016; Baldwin 2012; Ito 2011a; Kohan 2014; Wong 2005).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings for the main comparison. SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo for treating people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo for treating people with diabetes and CKD | |||||

| Patient or population: people with diabetes and CKD Intervention: SGLT2 inhibitors Comparison: placebo | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with SGLT2 inhibitors | ||||

| HbA1c (%) HbA1c (mmol/mol) |

The mean HbA1c was 0.29% lower (0.19 to 0.38 lower) with SGLT2 inhibitors compared to placebo The mean HbA1c was 3.2 mmol/mol lower (2.2 to 4.2 lower) with SGLT2 inhibitors compared to placebo |

MD ‐0.29 (‐0.38 to ‐0.19) MD ‐3.2 (‐4.2 to ‐2.2) |

1092 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | The mean FBG was 0.48 mmol/L lower (0.19 to 0.78 lower) with SGLT2 inhibitors compared to placebo | MD ‐0.48 (‐0.78 to ‐0.19) |

855 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Death (all causes) | 78 per 1,000 | 61 per 1,000 (47 to 79) | RR 0.78 (0.60 to 1.02) | 2933 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 |

| All cardiovascular death | 52 per 1,000 | 40 per 1,000 (29 to 57) | RR 0.78 (0.56 to 1.10) | 2788 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 |

| Weight (kg) | Weight was 1.41 kg lower (1.02 to 1.8 lower) with SGLT2 inhibitor compared to placebo | MD ‐1.41 (‐1.8 to ‐1.02) |

1029 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | The mean eGFR was 1.85 mL/min/1.73 m2 lower (0.94 to 2.76 lower) with SGLT2 inhibitors compared to placebo | MD ‐1.85 (‐2.76 to ‐0.94) |

848 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Hypoglycaemia | 118 per 1,000 | 104 per 1,000 (86 to 126) | RR 0.88 (0.73 to 1.07) | 3086 (7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 |

| Discontinuation of medication due to adverse events | 105 per 1,000 | 90 per 1,000 (59 to 138) | RR 0.86 (0.56 to 1.32) | 917 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 All studies had funding bias and/or attrition bias

2 Effect is beneficial or harmful but confidence interval is wide and crosses 1

3 Moderate heterogeneity in effect

4 Wide CI and the effect shows appreciable benefit and harm

Summary of findings 2. DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo for treating people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo for treating people with diabetes and CKD | |||||

| Patient or population: people with diabetes and CKD Intervention: DPP‐4 inhibitors Comparison: placebo | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with DPP‐4 inhibitors | ||||

| HbA1c (%) HbA1c (mmol/mol) |

The mean HbA1c was 0.62% lower (0.39 to 0.62 lower) with DPP‐4 inhibitors compared to placebo The mean HbA1c was 6.8 mmol/mol lower (4.3 to 9.3 lower) with DPP‐4 inhibitors compared to placebo |

MD ‐0.62 (‐0.85 to ‐0.39) MD ‐6.8 (‐9.3 to ‐4.3) |

867 (7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | The mean FBG was 0.47 mmol/L lower (1.08 lower to 0.15 higher) with DPP‐4 inhibitors compared to placebo | MD ‐0.47 (‐1.08 to 0.15) |

589 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | |

| Death (all causes) | 108 per 1,000 | 96 per 1,000 (81 to 115) | RR 0.89 (0.75 to 1.07) | 4211 (6) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 |

| All cardiovascular death | 77 per 1,000 | 71 per 1,000 (59 to 85) | RR 0.93 (0.77 to 1.11) |

5897 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 5 |

| Weight (kg) | The mean weight was 0.16 kg higher (0.58 lower to 0.9 higher) with DPP‐4 inhibitors compared to placebo | MD 0.16 (‐0.58 to 0.9) |

210 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 5 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | The mean eGFR was 1.99 mL/min/1.73 m2 lower (0.49 to 3.49 lower) with DPP‐4 inhibitors compared to placebo | MD ‐1.99 (‐3.49 to ‐0.49) |

130 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 5 6 | |

| Hypoglycaemia | 229 per 1,000 | 245 per 1,000 (183 to 325) | RR 1.07 (0.80 to 1.42) | 1443 (11) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 3 7 |

| Discontinuation of medication due to adverse events | 65 per 1,000 | 61 per 1,000 (40 to 94) | RR 0.94 (0.61 to 1.45) | 1257 (7) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 8 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference; HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c (glycated); FBG: fasting blood glucose; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 All studies had funding bias, and the majority had attrition bias

2 Moderate heterogeneity in results

3 Effect had appreciable benefit or harm but the confidence interval crossed 1

4 All studies had risk of funding bias and attrition bias

5 All studies had a risk of funding bias

6 Only 1 study reported this outcome

7 Majority of studies had funding bias and/or attrition bias

8 Wide confidence interval with appreciable benefit and harm

Summary of findings 3. GLP‐1 agonists versus placebo for treating people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| GLP‐1 agonists versus to placebo for treating people with diabetes and CKD | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with diabetes and CKD Intervention: GLP‐1 agonists Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with GLP‐1 agonists | |||||

| HbA1c (%) HbA1c (mmol/mol) |

The mean HbA1c was 0.53% lower (0.06 to 1.01 lower) with GLP‐1 agonists compared to placebo The mean HbA1c was 5.8 mmol/mol lower (0.7 to 11.0 lower) with GLP‐1 agonists compared to placebo |

MD ‐0.53 (‐1.01 to ‐0.06) MD ‐5.8 (‐11.0 to ‐0.7) |

283 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ‐ | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | The mean FBG was 1.08 mmol/L lower (0.45 to 1.71 lower) with GLP‐1 agonists compared to placebo | MD ‐1.08 (‐1.71 to ‐0.45) | 231 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ‐ | |

| Death (all causes) | 7 per 1,000 | 27 per 1,000 (3 to 235) | RR 3.91 (0.44 to 34.58) | 301 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ‐ |

| All cardiovascular death | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Weight (kg) | ‐ | ‐ | 303 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 |

On qualitative synthesis of results from two studies (total of 303 participants), liraglutide reduced body weight to a greater extent compared to the control group in people with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, including patients receiving HD. In one study in patients with ESKD receiving HD (24 participants), liraglutide resulted in a 2.20 kg loss of weight (‐3.87 to 0.53; P = 0.01) compared to placebo. However, weight (mean ± SE) was reduced insignificantly compared to before the treatment (91.1 ± 4.9 to 88.7 ± 5.2 kg, P= 0.22). In another study, in patients with an eGFR 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 both liraglutide and placebo exhibited gradual weight reduction (279 participants). The patients in the liraglutide group had a greater reduction in body weight compared to placebo (‐2.41 and ‐1.09 kg respectively) with an estimated treatment different of ‐1.32 kg (95% CI ‐2.24 to ‐0.4; P = 0.0052). |

|

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ‐ | ‐ | 279 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | Only one study reported eGFR. In this study, the mean observed changes in eGFR (MDRD) from baseline to week 26 was ‐0.35 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the GLP‐1 group and +0.37 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the placebo group; the estimated treatment effect was not significant (P = 0.36). The other study occurred in HD. | |

| Hypoglycaemia | ‐ | ‐ | 303 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | In one study in patients with an eGFR of 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (279 participants) liraglutide resulted in an equivalent risk of hypoglycaemia to placebo (0.79; 0.51 to 1.21; P = 0.28). In the other study (24 participants) with ESKD on HD, the number of episodes of hypoglycaemia did not differ between those receiving liraglutide and those receiving placebo. | |

| Discontinuation of medication due to adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | 303 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | In one study in patients with ESKD comparing liraglutide to placebo, there were no discontinuations due to adverse events in the liraglutide or placebo group (24 participants). In another study, in patients with an eGFR 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, (279 participants) liraglutide resulted in a 4.65 times higher risk of discontinuation due to adverse events compared to placebo (4.65; 1.62 to 13.31; P = 0.004) | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference; ; HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c (glycated); FBG: fasting blood glucose; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; HD: haemodialysis | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 All had risk of attrition bias and funding bias

2 Effect had appreciable benefit or harm but the confidence interval crossed 1

3 Narrative/qualitative synthesis was conducted. Estimates were not precise

4Downgraded one point because only one study reported eGFR, and therefore there is a likelihood of publication bias

Summary of findings 4. Glitazone versus placebo for treating people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| Glitazone versus placebo for treating people with diabetes and CKD | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with diabetes and CKD Intervention: glitazone Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with glitazone | |||||

| HbA1c (%) HbA1c (mmol/mol) |

The mean HbA1c was 0.41% lower (1.15 lower to 0.32 higher) with glitazone agonists compared to placebo The mean HbA1c was 4.5 mmol/mol lower (12.6 lower to 3.5 higher) with glitazone agonists compared to placebo |

MD ‐0.41 (‐1.15 to 0.32) MD ‐4.5 (‐12.6 to 3.5) |

88 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ‐ | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 233 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW5 6 | Qualitative synthesis of studies showed that glitazones, particularly pioglitazone lowered FBG compared to placebo in patients with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, including patients on HD. Two studies (total of 71 participants) in people with HD reported that pioglitazone lowered FBG at the end of the study compared to the start, and also lower than in placebo group (both P < 0.05). Similarly another study (39 participants) in HD patients reported that pioglitazone reduced the FBG by 2.91 mmol/L (‐5.44 to ‐0.38 mmol/L); P = 0.02 compared to placebo. Conversely another study in HD patients (63 participants) reported that pioglitazone resulted in a lower FBG (mean ± SD) at the end of the study compared to the start (7.72 ± 2.50 versus 6.89 ± 2.67 mmol/L P < 0.05), but this was not statistically lower than placebo (6.89 ± 2.67 versus 7.33 ± 2.56 mmol/L, P > 0.05). One study of people with earlier stages of CKD (60 participants) showed that in people with stage 3 CKD who were treated with pioglitazone‐losartan, there were higher rates of decline in blood glucose values compared with people treated with losartan only. This difference was significant after 12 months ( change (mean ± SD) after 12 months –22.7 ± 6.9% for pioglitazone‐losartan therapy as compared with –15.1 ± 6.3% for losartan alone; P < 0.01). Larger reductions in FBG concentrations were observed for people in this study with stage 4 CKD after 12 months of the combined as compared with the single‐drug treatment (i.e. –22.9 ± 8.9% versus –17.6 ± 5.9%; P = 0.07), but the difference was not significant. |

| Death (all causes) | 77 per 1,000 | 38 per 1,000 (4 to 398) | RR 0.50 (0.05 to 5.18) | 52 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | ‐ |

| All cardiovascular death | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Weight (kg) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 222 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW5 6 | From qualitative synthesis of data from 3 studies (total of 110 participants), pioglitazone did not result in a significant increase of dry weight compared to placebo in patients receiving HD (Abe 2007; Abe 2008a; Pfutzner 2011) or a significant increase of body weight compared to placebo in patients with an eGFR 15 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Jin 2007: 60 participants). Conversely, in patients receiving PD (Wong 2005: 52 participants), rosiglitazone resulted in more weight gain (mean ± SD) compared to placebo (2.0% ± 5.6% versus control, ‐0.8% ± 4.4%; P = 0.049). |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Hypoglycaemia | 59 per 1,000 | 56 per 1,000 (9 to 358) | RR 0.95 (0.15 to 6.08) | 70 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | ‐ |

| Discontinuation of medication due to adverse events | 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | not estimable | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 4 5 | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference; HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c (glycated); FBG: fasting blood glucose; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HD: haemodialysis; CKD: chronic kidney disease | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of attrition and funding bias

2 Substantial heterogeneity

3 CI is wide and effect shows appreciable benefit and harm

4 Only 1 study had data for this outcome

5 Risk of selection, performance and detection bias

6 Narrative/qualitative synthesis was conducted. Estimates were not precise

Summary of findings 5. Sitagliptin versus glipizide for treating people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| Sitagliptin versus glipizide for treating people with diabetes and CKD | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with diabetes and CKD Intervention: sitagliptin Comparison: glipizide | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with glipizide | Risk with sitagliptin | |||||

| HbA1c (%) HbA1c (mmol/mol) |

The mean HbA1c was 0.05% lower (0.39 lower to 0.29 higher) with glipizide compared to sitagliptin The mean HbA1c was 0.6 mmol/mol lower (4.3 lower to 3.2 higher) with glipizide compared to sitagliptin |

MD ‐0.05 (‐0.39 to 0.29) MD ‐0.6 (‐4.3 to 3.2) |

398 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ‐ | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | Mean FBG was 0.36 mmol/L higher (0.1 lower to 0.82 higher) with glipizide compared to sitagliptin | MD 0.36 (‐0.1 to 0.82) | 397 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | ‐ | |

| Death (all causes) | 47 per 1,000 | 26 per 1,000 (10 to 64) | RR 0.55 (0.22 to 1.36) | 551 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | ‐ |

| All cardiovascular death | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Weight (kg) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 552 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 5 | In one study in people with an eGFR < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 but not on dialysis (423 participants) sitagliptin resulted in a reduction in body weight (‐0.6 kg) compared to glipizide where the body weight increased (1.2 kg), resulting in a statistically significant (P < 0.001) between‐group difference of ‐1.8 kg. Conversely in another study in people with ESKD on dialysis (129 participants), sitagliptin had a similar effect to glipizide on weight ‐1.00 kg (‐2.80 to 0.80) P = 0.28. |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 552 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 5 | One study (423 participants) occurred in patients with an eGFR < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 and not on dialysis. There were similar reductions from baseline in eGFR observed in the sitagliptin and glipizide groups (sitagliptin, 23.9 mL/min/1.73 m2; glipizide, 23.3 mL/min/1.73 m2). Similarly in another study (129 participants) which occurred in patients receiving dialysis, there were no meaningful differences in changes from baseline in eGFR, SCr, UACR between sitagliptin and glipizide. |

| Hypoglycaemia | 155 per 1,000 | 62 per 1,000 (36 to 107) | RR 0.40 (0.23 to 0.69) | 551 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ‐ |

| Discontinuation of medication due to adverse events | 90 per 1,000 | 84 per 1,000 (49 to 144) | RR 0.93 (0.54 to 1.60) | 551 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference; HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c (glycated); FBG: fasting blood glucose; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; SCr: serum creatinine; UACR: urinary albumin/creatinine ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Both studies had funding bias and attrition bias

2 Heterogeneity in results

3 Effect has either benefit or harm with a confidence interval that crosses 1

4 Effect has both appreciable benefit and harm with a wide confidence interval that crosses 1

5 Narrative/Qualitative synthesis was conducted. Estimates were not precise

Primary outcomes

Glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)

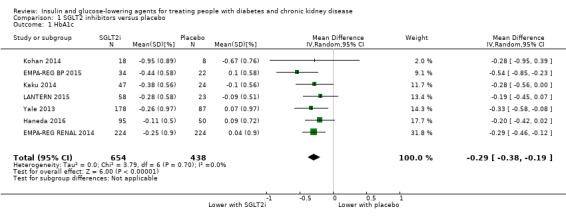

SGLT2 Inhibitors versus placebo

In people with an eGFR 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, SGLT2 inhibitors probably reduce HbA1c (MD ‐0.29%, 95% CI ‐0.38 to ‐0.19 (‐3.2 mmol/mol, ‐4.2 to ‐2.2); I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.1) compared to placebo (7 studies, 1092 participants; moderate certainty evidence) (EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; Haneda 2016; Kaku 2014; Kohan 2014; LANTERN 2015; Yale 2013).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 1 HbA1c.

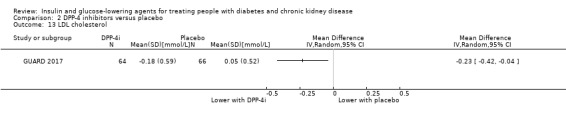

DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo

In people with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those people with ESKD receiving dialysis, DPP‐4 inhibitors may reduce HbA1c (MD ‐0.62%, 95% CI ‐0.85 to ‐0.39 (‐6.8 mmol/mol, ‐9.3 to ‐4.3); I2 = 59%; Analysis 2.1) compared to placebo (7 studies, 867 participants; low certainty evidence) (Barnett 2013; Chan 2008a; GUARD 2017; Laakso 2015; McGill 2013; Nowicki 2011; Yki‐Järvinen 2013).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 1 HbA1c.

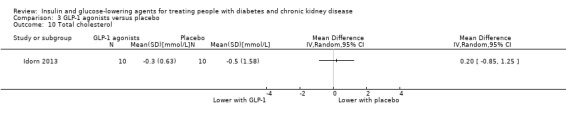

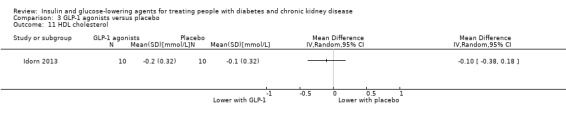

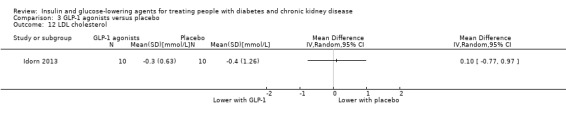

GLP‐1 agonists versus placebo

In people with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those people receiving HD, GLP‐1 agonists probably reduce HbA1c (MD ‐0.53%, 95% CI ‐1.01 to ‐0.06 (‐5.8 mmol/mol, ‐11.0 to ‐0.7); I2 = 41%; Analysis 3.1), compared to placebo (2 studies, 283 participants; moderate certainty evidence) (Idorn 2013; LIRA‐RENAL 2016).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 GLP‐1 agonists versus placebo, Outcome 1 HbA1c.

Glitazones versus placebo/control

In people receiving HD and PD it is uncertain whether glitazones have any effect on HbA1c (MD ‐0.41%, 95% CI ‐1.15 to 0.32 (‐4.5 mmol/mol, ‐12.6 to 3.5); I2 = 66%; Analysis 4.1) compared to placebo (2 studies, 88 participants; very low certainty evidence) (Pfutzner 2011; Wong 2005).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Glitazone versus placebo/control, Outcome 1 HbA1c.

Glinides versus placebo/control

Abe 2010 compared glinide to no glinide treatment (36 participants) in people receiving dialysis. Mitiglinide was reported to reduce HbA1c compared to placebo over 24 weeks.

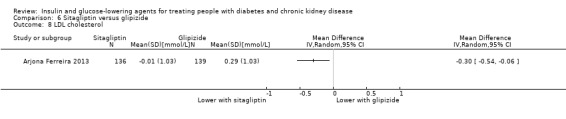

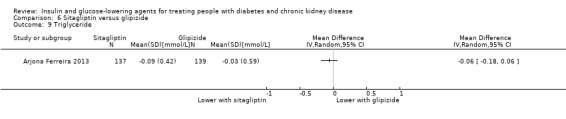

Sitagliptin versus glipizide

In people with an eGFR < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2, including those on dialysis, sitagliptin may make little or no difference to HbA1c (MD ‐0.05%, 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.29 (‐0.6 mmol/mol, ‐4.3 to 3.2); I2 = 67%; Analysis 6.1) compared to glipizide (2 studies, 398 participants; low certainty evidence) (Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sitagliptin versus glipizide, Outcome 1 HbA1c.

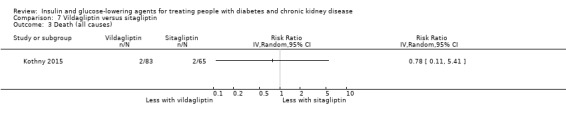

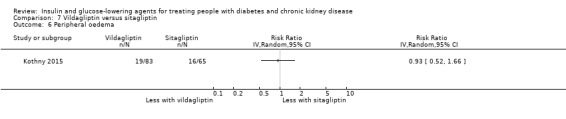

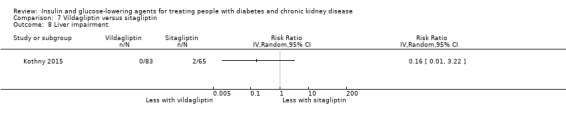

Vildagliptin versus sitagliptin

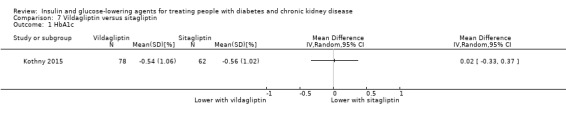

Kothny 2015 compared vildagliptin to sitagliptin (148 participants) in people with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those receiving HD. In this study vildagliptin had little or no effect on HbA1c compared to sitagliptin (MD 0.02%, 95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.37 (0.2 mmol/mol, ‐3.6 to 4.0); P = 0.91; Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vildagliptin versus sitagliptin, Outcome 1 HbA1c.

Albiglutide versus sitagliptin

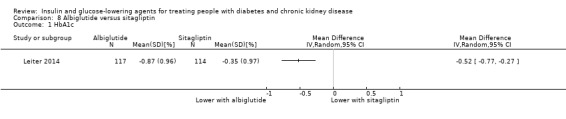

Leiter 2014 compared albiglutide to sitagliptin (507 participants) in people with an eGFR 15 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Albiglutide was reported to reduce HbA1c (MD ‐0.52%, 95% CI ‐0.77 to ‐0.27 (‐5.7 mmol/mol, ‐8.4 to ‐3.0); P < 0.0001) compared to sitagliptin (Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Albiglutide versus sitagliptin, Outcome 1 HbA1c.

Sitagliptin versus insulin

Bellante 2016 compared sitagliptin to insulin (49 participants) in people with an eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2, including those people receiving HD. HbA1c was reported to be reduced from 8.2 ± 1.9% (66.1 ± 20.8 mmol/mol) at baseline to 7.3 ± 1.4% (56.3 ± 15.3 mmol/mol) at 52 weeks (P = 0.058) in the insulin group and was unchanged in the sitagliptin group (7.1 ± 1.0% (54.1 ± 10.9 mmol/mol) to 6.9 ± 0.8% (51.9 ± 8.7 mmol/mol)).

Linagliptin versus voglibose

Mori 2016 compared linagliptin to voglibose (78 participants) in people receiving HD. Linagliptin was reported to reduce HbA1c to a greater extent than voglibose (‐0.60% (‐6.6 mmol/mol) compared to ‐0.20% (‐2.2 mmol/mol); treatment difference (‐0.40%, 95% CI ‐0.74 to ‐0.06 (MD ‐4.4 mmol/mol, 95% CI ‐8.1 to ‐0.7); P = 0.022).

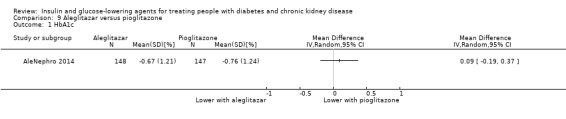

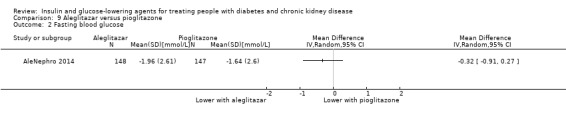

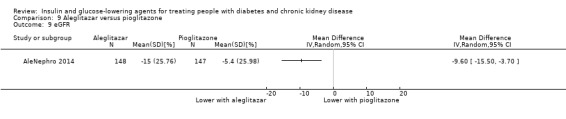

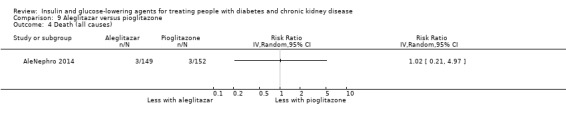

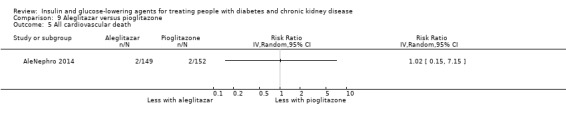

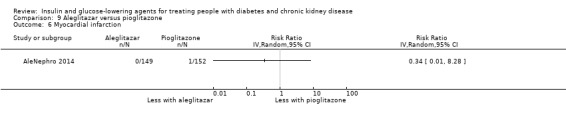

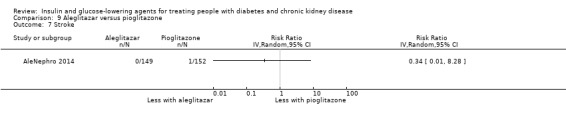

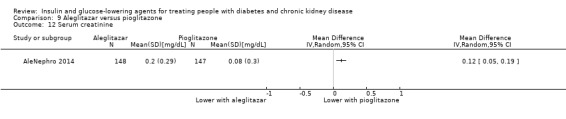

Aleglitazar versus pioglitazone

AleNephro 2014 compared aleglitazar to pioglitazone (302 participants) in people with an eGFR of 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. In this study aleglitazar made little or no difference to HbA1c compared to pioglitazone (MD 0.09%, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.37 (1.0 mmol/mol, ‐2.1 to 4.0); P = 0.53; Analysis 9.1).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Aleglitazar versus pioglitazone, Outcome 1 HbA1c.

Insulin

Two studies compared insulin administered IP to SC in people receiving PD (Diez 1987; Scarpioni 1994). In Diez 1987 (22 participants) there was no difference in HbA1c between the groups while Scarpioni 1994 (6 participants in a cross‐over study) did not report HbA1c as an outcome.

Studies comparing regular insulin to lispro insulin (Ruggenenti 2003a; 11 participants) and 0.25 U/kg of insulin glulisine and glargine compared to 0.5 U/kg (Baldwin 2012; 107 participants) did not report HbA1c as an outcome.

Fasting blood glucose

SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo

In people with an eGFR of 15 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, SGLT2 inhibitors probably reduce FBG by 0.48 mmol/L (95% CI ‐0.78 to ‐0.19; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.2) compared to placebo (5 studies; 855 participants; moderate certainty evidence) (EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; Haneda 2016; Kohan 2014; Yale 2013; Zambrowicz 2015).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 2 Fasting blood glucose.

DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo

In people with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, inclusive of people with ESKD receiving dialysis, DPP‐4 inhibitors may make little or no difference to FBG (MD ‐0.47 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐1.08 to 0.15; I2 = 16%; Analysis 2.2,) compared to placebo (4 studies; 589 participants; low certainty evidence) (Chan 2008a; Laakso 2015; McGill 2013; Nowicki 2011).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 2 Fasting blood glucose.

GLP‐1 agonists versus placebo

LIRA‐RENAL 2016 (279 participants) quantified the difference in effect of liraglutide compared to placebo in people with an eGFR of 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Liraglutide was reported to reduce FBG by 1.08 mmol/L (95% CI ‐1.71 to ‐0.45; P = 0.0008) compared to placebo (Analysis 3.2). Idorn 2013 (24 participants) did not report FBG.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 GLP‐1 agonists versus placebo, Outcome 2 Fasting blood glucose.

Glitazones versus placebo/control

Meta‐analysis of data was not possible due to heterogeneity in the outcomes and reporting of outcomes. Qualitative synthesis of the studies showed that glitazones, particularly pioglitazone may reduce FBG compared to placebo in people with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, including people on HD.

Two studies (71 participants) in HD people reported that pioglitazone reduced FBG more so than in the group not receiving pioglitazone (both P < 0.05; Abe 2007 (31 participants); Abe 2008a (40 participants)). Similarly, another study in HD people (Pfutzner 2011 (39 participants)) reported that pioglitazone reduced the FBG by 2.91 mmol/L (95% CI ‐5.44 to ‐0.38; P = 0.02) compared to placebo (Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Glitazone versus placebo/control, Outcome 2 Fasting blood glucose.

In people with stage 3 CKD (60 participants), after 12 months, Jin 2007 reported pioglitazone‐losartan treatment resulted in a higher rate of decline for FBG values compared to losartan‐only treatment (change after 12 months –22.7 ± 6.9% for pioglitazone‐losartan therapy as compared with –15.1 ± 6.3% for losartan alone; P < 0.01). In stage 4 CKD, this drug combination was reported to have had little or no effect on FBG after 12 months compared with single‐drug treatment (–22.9 ± 8.9% versus –17.6 ± 5.9%; P = 0.07).

Conversely Abe 2010a (63 participants) reported that in HD people, pioglitazone reduced FBG at the end of the study compared to the start (7.72 ± 2.50 versus 6.89 ± 2.67 mmol/L; P < 0.05). However pioglitazone makes little or no difference to FBG compared to people not receiving pioglitazone (6.89 ± 2.67 mmol/L versus 7.33 ± 2.56 mmol/L; P > 0.05).

Data were unavailable from three studies (Mohideen 2005; Nakamura 2001; Wong 2005).

Glinides versus placebo/control

Abe 2010 compared glinides to a control group (36 participants) in people receiving HD. Mitiglinide was reported to reduce FBG compared to placebo over 24 weeks.

Sitagliptin versus glipizide

In people with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those people receiving HD, sitagliptin may make little or no difference to FBG (MD 0.36 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.82; I2 = 0%; Analysis 6.2) compared to glipizide (2 studies; 397 participants; low certainty evidence) (Arjona Ferreira 2013; Arjona Ferreira 2013a).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sitagliptin versus glipizide, Outcome 2 Fasting blood glucose.

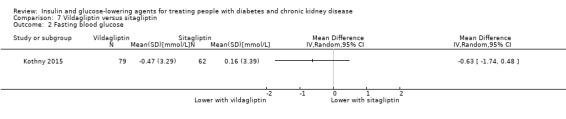

Vildagliptin versus sitagliptin

Kothny 2015 compared vildagliptin to sitagliptin (148 participants) in people with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 including those receiving HD. This study reported vildagliptin made little or no difference to FBG compared to sitagliptin (MD ‐0.63 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐1.74 to 0.48; P = 0.27; Analysis 7.2).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Vildagliptin versus sitagliptin, Outcome 2 Fasting blood glucose.

Albiglutide versus sitagliptin

Leiter 2014 compared albiglutide to sitagliptin (507 participants) in people with an eGFR of 15 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Albiglutide was reported to reduce the FBG by 1.61 mmol/L (95% IC ‐2.35 to ‐0.87, P < 0.0001), compared to sitagliptin (Analysis 8.2).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Albiglutide versus sitagliptin, Outcome 2 Fasting blood glucose.

Sitagliptin versus insulin

Bellante 2016 did not report FBG.

Linagliptin versus voglibose

Mori 2016 did not report FBG.

Aleglitazar versus pioglitazone

AleNephro 2014 compared aleglitazar to pioglitazone (302 participants) in people with an eGFR of 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. This study reported aleglitazar had little or no effect on FBG compared to pioglitazone (MD ‐0.32 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.91 to 0.27; P = 0.29; Analysis 9.2).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Aleglitazar versus pioglitazone, Outcome 2 Fasting blood glucose.

Insulin

Two studies compared IP versus SC insulin in people receiving PD (Diez 1987; Scarpioni 1994). Diez 1987 (22 participants) reported no difference in the FBG between groups, while Scarpioni 1994 (6 participants in a cross‐over study) did not report FBG.

Baldwin 2012 (107 participants), compared 0.25 U/kg of insulin glulisine and glargine to 0.5 U/kg in people with an eGFR ≤ 45 mL/min/1.73 m2. A SC insulin regimen of 0.25 U/kg/d (half of the dose insulin glulisine three times a day and half the dose glargine once a day) was reported to have had little or no effect on FBG compared to a regimen of 0.5 U/kg/d (half of the dose insulin glulisine three times a day and half of the dose glargine once a day; i.e. 8.62 ± 2.97 mmol/L versus 8.44 ± 3.48 mmol/L; P = 0.78) in people with an eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Ruggenenti 2003a did not report FBG.

Secondary outcomes

Kidney function (creatinine, eGFR, albuminuria)

SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo

In people with an eGFR of 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, SGLT2 inhibitors probably increase SCr by 3.82 μmol/L (95% CI 1.45 to 6.19 (0.04 mg/dL, 0.02 to 0.07); I2 = 16%; Analysis 1.12) and probably reduces eGFR by 1.85 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI ‐2.76 to ‐0.94; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.9) compared to placebo (4 studies, 848 participants; moderate certainty evidence) (EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; Haneda 2016; Kohan 2014; LANTERN 2015). However, SGLT2 inhibitors may reduce albuminuria (MD ‐8.14 mg/mmol creatinine, 95% CI ‐14.51 to ‐1.77 (‐71.89 mg/g creatinine, ‐128.17 to ‐15.60); I2 = 11%; Analysis 1.13) compared to placebo (5 studies; 1153 participants; low certainty evidence) (EMPA‐REG RENAL 2014; Haneda 2016; Kohan 2014; LANTERN 2015; Yale 2013) (Analysis 1.13).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 12 Serum creatinine.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 9 eGFR [mL/min/1.73 m2].

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SGLT2 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 13 Urinary albumin/creatinine ratio.

Relevant data suitable for incorporation in meta‐analyses were not available from EMPA‐REG OUTCOME 2013.

DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo

Meta‐analysis of data was not possible due to heterogeneity in, and reporting of, outcomes; as well as the different CKD stages of the participants studied. Two studies were in people undergoing dialysis making reporting of kidney function (creatinine, eGFR and albuminuria) meaningless (Abe 2016; Ito 2011a).

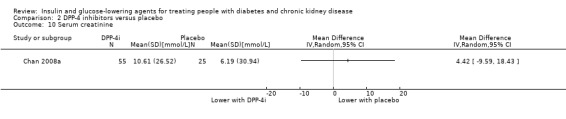

Several studies reported no significant or a small difference in the effects of DPP‐4 inhibitors compared to placebo on kidney function. In McGill 2013 (133 participants), linagliptin made little or no difference to the risk of kidney failure compared to placebo. Similarly, in Yki‐Järvinen 2013 (127 participants) there were no between‐group imbalance in shifts in stage of CKD. Two studies compared the effect of saxagliptin to placebo on kidney function. In SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011, for people with an eGFR of 15 to < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 (2576 participants) saxagliptin was reported to reduce eGFR to a similar extent as placebo. In Nowicki 2011 (571 participants) which compared the effects of saxagliptin with placebo in people with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 50 mL/min, saxagliptin doubled the SCr concentration from baseline in three people during the 52‐week treatment period. For those people not on dialysis, both saxagliptin and placebo were reported to slightly reduce the mean GFR (estimated by the Cockcroft‐Gault and MDRD equations). Two studies compared the effect of sitagliptin to placebo on the eGFR. In Chan 2008a (91 participants), which compared sitagliptin to placebo in people with a CrCl ≥ 30 to < 50 mL/min, sitagliptin made little or no difference to SCr compared to placebo (MD 4.42 μmol/L, 95% CI ‐9.59 to 18.43 (0.05 mg/dL, ‐0.11 to 0.21); P = 0.54; Analysis 2.10). In TECOS 2013 (3324 participants) there was a reported small reduction with sitagliptin in eGFR compared to placebo (mean between group treatment difference ‐1.33 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI ‐2.45 to ‐0.21) for people with an eGFR 45 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2; and ‐2.25 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI ‐4.27 to ‐0.23) for people with an eGFR of 30 to 44 mL/min/1.73 m2. Additionally in a study comparing vildagliptin to placebo (Lukashevich 2011; 525 participants), there was a reported small and similar decline in eGFR over the year in both groups.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 10 Serum creatinine.

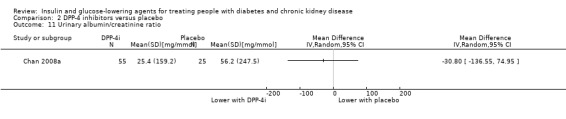

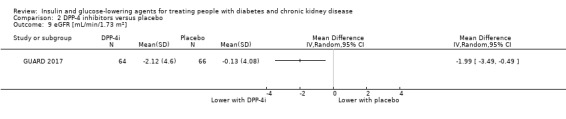

Three studies reported an improvement in albuminuria. Chan 2008a (91 participants) compared sitagliptin to placebo in people with an eGFR < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 to people on dialysis. In both groups, there was an increase from baseline (mean ± SE) in the UACR of 25,425 ± 21,470 mg/mmol (225 ± 190 mg/mg) and 56,161 ± 49,494 mg/mmol (497 ± 438 mg/mg) for the sitagliptin and placebo groups respectively (Analysis 2.11). GUARD 2017 (130 participants) compared gemigliptin to placebo in people with an eGFR of 15 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2. Gemigliptin reduced the UACR at week 12 by 28.0% (95% CI ‐40.2 to ‐13.3) compared with 4.3% (95% CI ‐19.7 to 14.2) with placebo with a between‐group difference of 24.8% (95% CI ‐41.8 to ‐2.9; P = 0.0294). However, Gemigliptin also reduced eGFR compared to placebo (MD ‐1.99 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐3.49 to ‐0.49; P = 0.009; Analysis 2.9). In SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011, for people with an eGFR of 15 to < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 (2576 participants) saxagliptin reduced UACR compared to placebo. From baseline to two years, saxagliptin was reported to reduce UACR to a greater extent compared to placebo for those with an eGFR ≤ 50 and ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (‐11.87 mg/mmol (‐105 mg/g); P = 0.011) and an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (‐27.71 mg/mmol (‐245.2 mg/g); P = 0.086). In TECOS 2013 (3324 participants), for people with an eGFR of 30 to < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, sitagliptin did not reduce the UACR compared to placebo (mean between group treatment difference ‐0.03 mg/mmol, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.01 (‐0.30 mg/g, ‐0.70 to 0.09) for people with an eGFR of 45 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2; and 0.03 mg/mmol, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.11 (0.23 mg/g, ‐0.54 to 1.00) for people with an eGFR of 30 to 44 mL/min/1.73 m2)).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 11 Urinary albumin/creatinine ratio.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DPP‐4 inhibitors versus placebo, Outcome 9 eGFR [mL/min/1.73 m2].

Data for kidney function were not available for three studies (Barnett 2013; Lewin 2012; SAVOR‐TIMI 53 2011).

GLP‐1 agonists versus placebo/control

Meta‐analysis of data was not possible due to heterogeneity in, and reporting of, outcomes.

Qualitative synthesis of studies (303 participants) show that liraglutide made little or no difference to kidney function compared to placebo, although one of the studies occurred in people on dialysis (Idorn 2013). In Idorn 2013 (24 participants), for people with ESKD on dialysis, it was reported that liraglutide had little or no effect on SCr compared to placebo (MD ‐0.88 μmol/L, 95% CI ‐5.30 to 3.5 (‐0.01 mg/dL, ‐0.06 to 0.04); P = 0.69; Analysis 3.9). However, this is meaningless given that the included people were on dialysis. Similarly in LIRA‐RENAL 2016 (279 participants), liraglutide made little or no difference to kidney function parameters compared to placebo. Liraglutide makes little or no difference to the ratio of week 26 to baseline for SCr compared to placebo (P = 0.26). Liraglutide changed the mean eGFR from baseline to week 26 by ‐0.35 mL/min/1.73 m2 compared to placebo (0.37 mL/min/1.73 m2). The estimated ratio of the week 26 to baseline UACR was 0.87 with liraglutide and 1.05 with placebo.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 GLP‐1 agonists versus placebo, Outcome 9 Serum creatinine.

Glitazones versus placebo/control

Meta‐analysis of data was not possible.